Submitted:

06 November 2023

Posted:

07 November 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Coating Materials

Substrate Materials

Coating Compositions

Surface Modification Techniques

Laser Metal Deposition

Microstructure Analysis

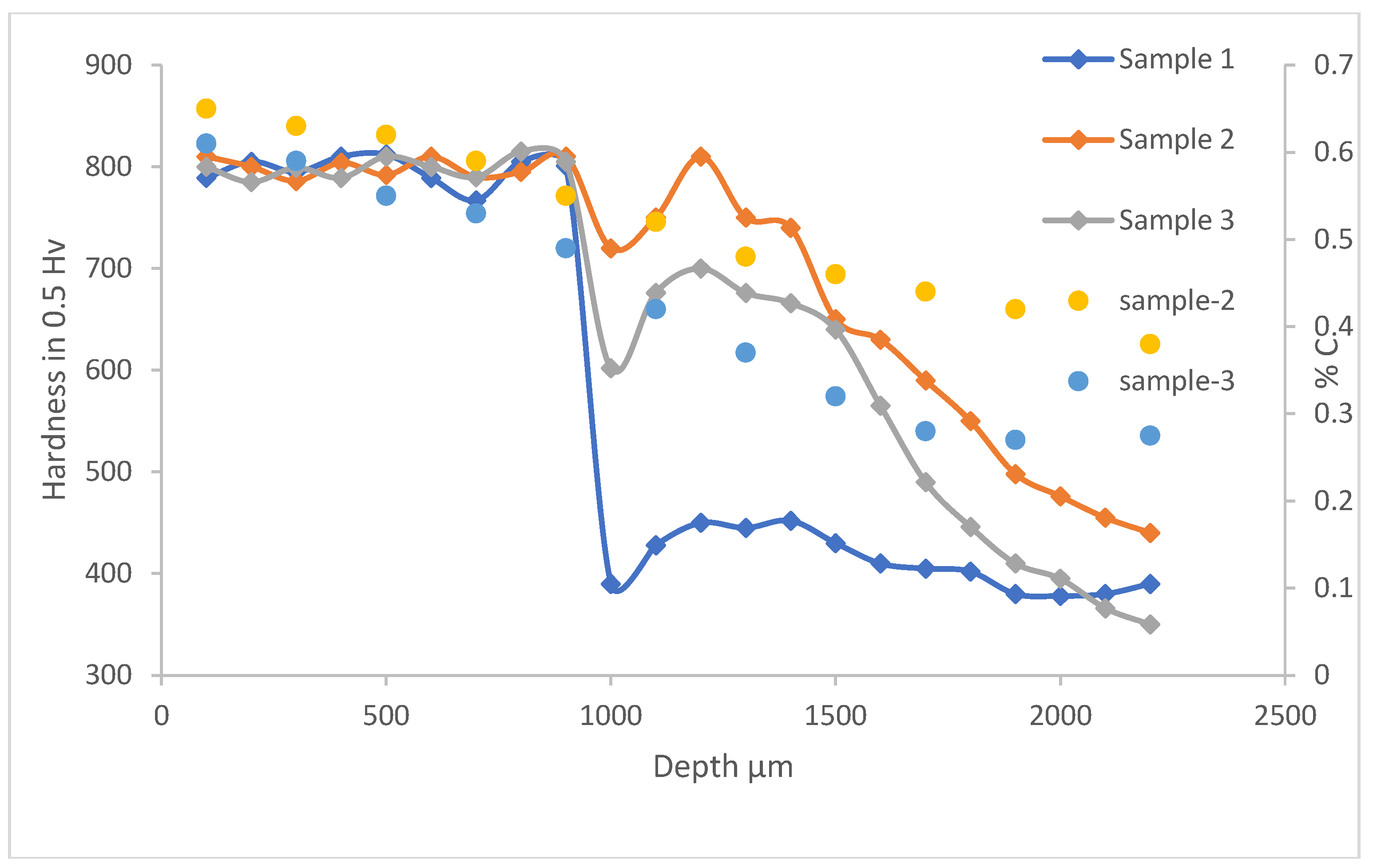

Mechanical Testing

Experimental Design

3. Results and Discussion:

Surface Roughness

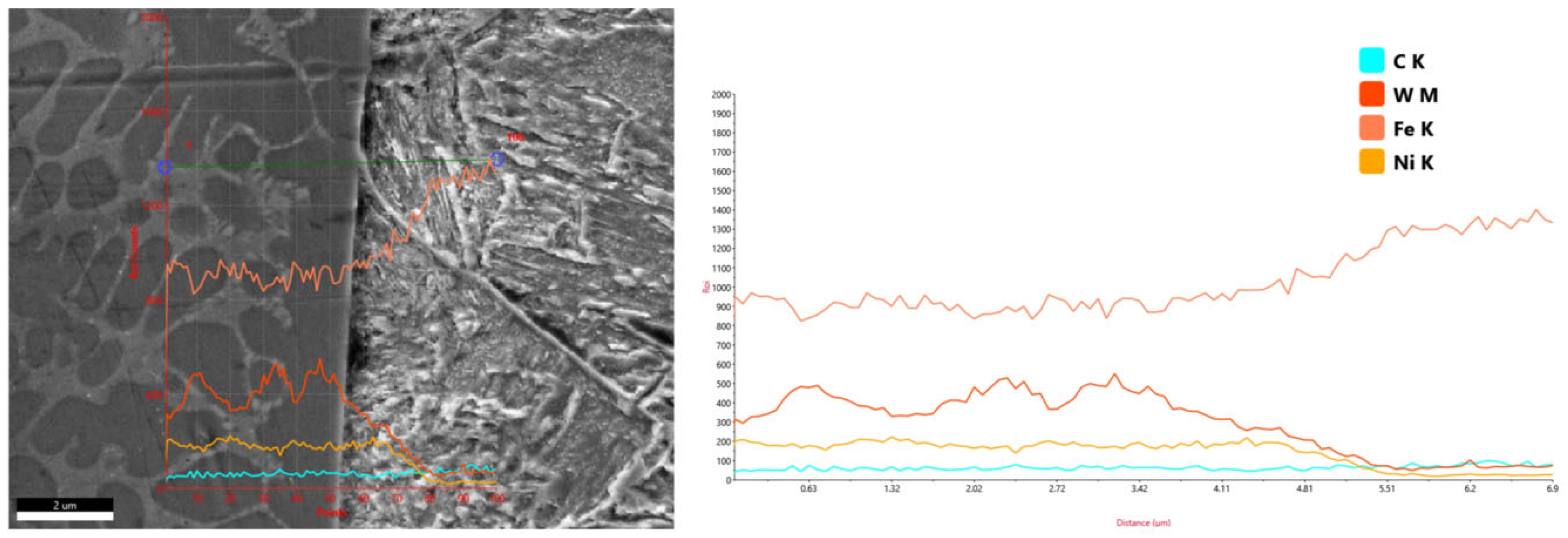

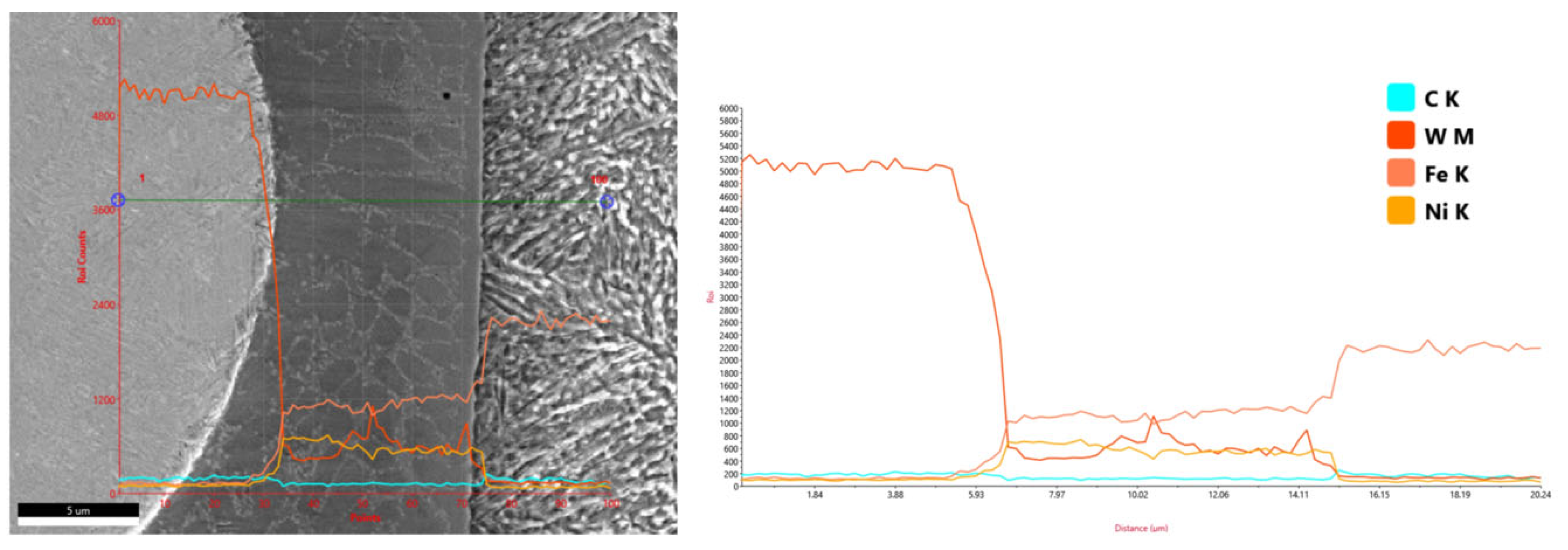

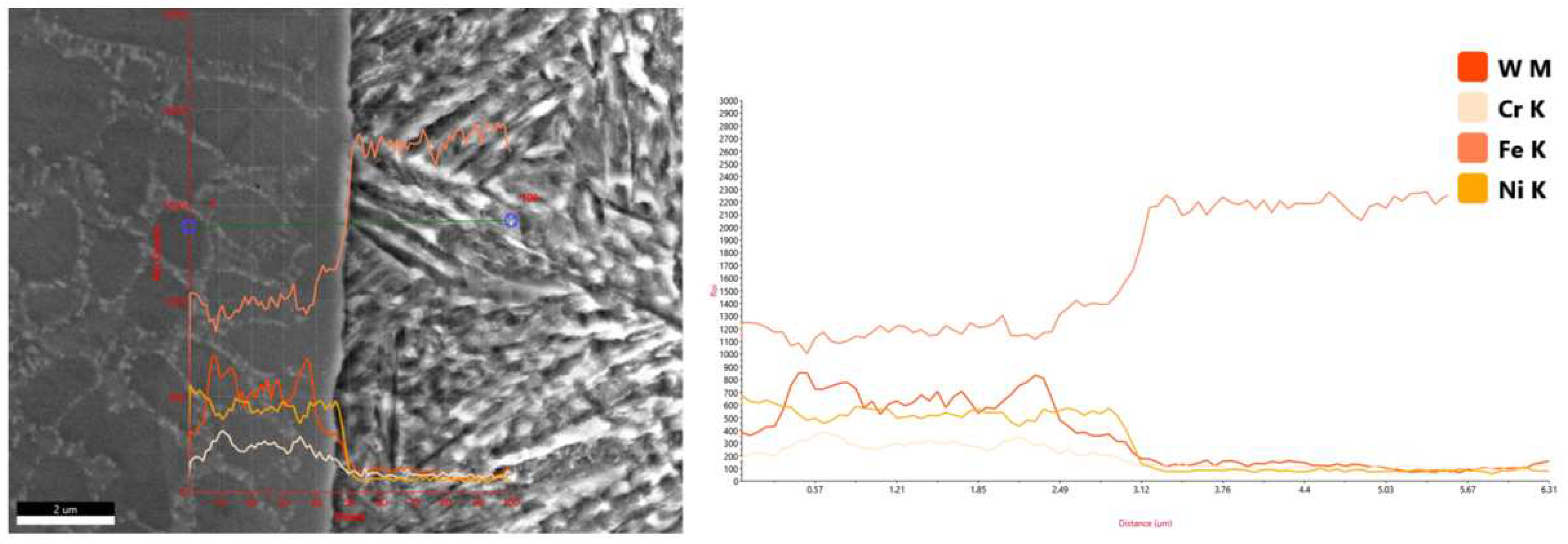

2.2. Microstructures post laser metal deposition

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varun, K.; Kalyan, M. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of parallel layered WC- NiCr weld overlay on 080 M40 steel substrate prepared using additive manufacturing. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2022; 67, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.J.; D׳Oliveira, A.S.C. NiCrSiBC coatings: Effect of dilution on microstructure and high temperature tribological behavior. Wear, 2016; 350, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachidi, R.; El Kihel, B.; Delaunois, F. Microstructure and mechanical characterization of NiCrBSi alloy and NiCrBSi-WC composite coatings produced by flame spraying. Materials Science and Engineering: B, 2019; 241, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulka, I.; Uțu, I.D.; Avram, D.; Dan, M.L.; Pascu, A.; Stanciu, E.M.; Roată, I.C. Influence of the Laser Cladding Parameters on the Morphology, Wear and Corrosion Resistance of WC-Co/NiCrBSi Composite Coatings. Materials 2021, 14, 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Škamat, J.; Černašėjus, O.; Zhetessova, G.; Nikonova, T.; Zharkevich, O.; Višniakov, N. Effect of Laser Processing Parameters on Microstructure, Hardness and Tribology of NiCrCoFeCBSi/WC Coatings. Materials 2021, 14, 6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, A.; Sanjabi, S. Infiltration brazed core-shell WC@NiP/NiCrBSi composite cladding. Surface and Coatings Technology 2018, 352, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Lei, J.; Dai, X.; Guo, J.; Gu, Z.; Pan, H. A comparative study of the structure and wear resistance of NiCrBSi/50 wt.% WC composite coatings by laser cladding and laser induction hybrid cladding. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 2016; 60, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunovic, K.; Slokar, L.; Havrlisan, S. SEM/EDS investigation of one-step flame sprayed and fused Ni-based self-fluxing alloy coatings on steel substrates. Philosophical Magazine 2016, 97, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschuyteneer, D.; Petit, F.; Gonon, M.; Cambier, F. Processing and characterization of laser clad NiCrBSi/WC composite coatings — Influence of microstructure on hardness and wear. Surface and Coatings Technology 2015, 283, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, S.; Brueckner, F.; Thieme, S.; Leyens, C.; Beyer, E. High-performance laser cladding with combined energy sources. Journal of Laser Applications, 2014; 27, (Supp. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, F.; Riede, M.; Marquardt, F.; Willner, R.; Seidel, A.; Thieme, S.; Leyens, C.; Beyer, E. Process characteristics in high-precision laser metal deposition using wire and powder. Journal of Laser Applications 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishkovsky, I.; Kakovkina, N.; Sherbakof, V. Mechanical properties of NiCrBSi self-fluxing alloy after LPBF with additional heating. Procedia CIRP 2020, 94, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunovic, K.; Saric, T.; Simunovic, G. Different Approaches to the Investigation and Testing of the Ni-Based Self-Fluxing Alloy Coatings—A Review. Part 1: General Facts 2014, Wear and Corrosion Investigations. Tribology Transactions, 57, 955–979. [CrossRef]

- Simunovic, K.; Saric, T.; Simunovic, G. Different Approaches to the Investigation and Testing of the Ni-Based Self-Fluxing Alloy Coatings—A Review. Part 2: Microstructure 2014, Adhesive Strength, Cracking Behavior, and Residual Stresses Investigations. Tribology Transactions, 57, 980–1000. [CrossRef]

- Sbrizher, A.G. Structure and properties of coatings made of self-fluxing alloys. Metal Science and Heat Treatment 1988, 30, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergant, Z.; Trdan, U.; Grum, J. Effect of high-temperature furnace treatment on the microstructure and corrosion behavior of NiCrBSi flame-sprayed coatings. Corrosion Science 2014, 88, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dong, Y.; Wan, L.; Yang, Y.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Li, D. Effect of induction remelting on the microstructure and properties of in situ TiN-reinforced NiCrBSi composite coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2018, 340, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschuyteneer, D.; Petit, F.; Gonon, M.; Cambier, F. Influence of large particle size – up to 1.2 mm – and morphology on wear resistance in NiCrBSi/WC laser cladded composite coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology, 2017; 311, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschuyteneer, D.; Petit, F.; Gonon, M.; Cambier, F. Processing and characterization of laser clad NiCrBSi/WC composite coatings — Influence of microstructure on hardness and wear. Surface and Coatings Technology 2015, 283, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buytoz, S.; Ulutan, M.; Islak, S.; Kurt, B.; Nuri Çelik, O. Microstructural and Wear Characteristics of High Velocity Oxygen Fuel (HVOF) Sprayed NiCrBSi–SiC Composite Coating on SAE 1030 Steel. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2013, 38, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Lei, Y.; Niu, W. Laser clad TiC reinforced NiCrBSi composite coatings on Ti–6Al–4V alloy using a CW CO2 laser. Surface and Coatings Technology 2009, 203, 1395–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, Sarcar, M.; Suman, K.; Kamaluddin, S. Tribological and Corrosion behavior of HVOF Sprayed WC-Co, NiCrBSi and Cr3C2-NiCr Coatings and analysis using Design of Experiments. In Materials Today: Proceedings; 2015; Volume 2, pp. 2654–2665. [CrossRef]

- CAI, B.; TAN, Y.F.; TAN, H.; JING, Q.F.; ZHANG, Z.W. Tribological behavior and mechanism of NiCrBSi–Y2O3 composite coatings. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2013, 23, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, I.; Rao, J.; Ocelík, V.; De Hosson, J. Electron Microscopy Characterization of Ni-Cr-B-Si-C Laser Deposited Coatings. Microscopy and Microanalysis 2013, 19, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, H.; Sang, P.; Lu, S.; Wang, Z.X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.C. Phase interaction induced texture in a plasma sprayed-remelted NiCrBSi coating during solidification: An electron backscatter diffraction study. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 358, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, P.; Koiprasert, H. Effect of W dissolution in NiCrBSi–WC and NiBSi–WC arc sprayed coatings on wear behaviors. Wear 2014, 317, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Dai, X. Laser induction hybrid rapid cladding of WC particles reinforced NiCrBSi composite coatings. Applied Surface Science 2010, 256, 4708–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergant, Z.; Grum, J. Quality Improvement of Flame Sprayed, Heat Treated, and Remelted NiCrBSi Coatings. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2009, 18, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; García, A.; Cuetos, J.; González, R.; Noriega, A.; Cadenas, M. Effect of actual WC content on the reciprocating wear of a laser cladding NiCrBSi alloy reinforced with WC. Wear, 2015; 324, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.Z.; Barakat, W.S. Y.A.; Mohamed, A.A.; Alsaleh, N.; Elkady, O.A. The Development of WC-Based Composite Tools for Friction Stir Welding of High-Softening-Temperature Materials. Metals, 2021; 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wu, C.; He, Y.; Xiao, D. Effect of Cu, Ni on the property and microstructure of ultrafine WC-10Co alloys by sinter–hipping. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2011, 29, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.H. Tribological behaviour of NiCrBSi–WC(Co) coatings. Materials Research Innovations 2014, 18(sup2), S2–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vencl, A.; Mrdak, M.; Hvizdos, P. Tribological Properties of WC-Co/NiCrBSi and Mo/NiCrBSi Plasma Spray Coatings under Boundary Lubrication Conditions. Tribology in Industry 2017, 39, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolelli, G.; Börner, T.; Milanti, A.; Lusvarghi, L.; Laurila, J.; Koivuluoto, H.; Niemi, K.; Vuoristo, P. Tribological behavior of HVOF- and HVAF-sprayed composite coatings based on Fe-Alloy+WC–12% Co. Surface and Coatings Technology 2014, 248, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.W. The Hardness and Strength Properties of WC-Co Composites. Materials 2011, 4, 1287–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valsecchi, B.; Previtali, B.; Vedani, M.; Vimercati, G. Fiber Laser Cladding with High Content of WC-Co Based Powder. International Journal of Material Forming 2010, 3 (Suppl. S1), 1127–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, M.; Vijande, R.; Montes, H.; Sierra, J. Wear behaviour of laser cladded and plasma sprayed WCCo coatings. Wear 1997, 212, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, G.; Kremser, G.; Bock, A.; Weidow, J.; Schubert, W.D. Transition of W 2 C to WC during carburization of tungsten metal powder. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2018, 72, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranatlumpong, P.; Koiprasert, H. Phase transformation of NiCrBSi–WC and NiBSi–WC arc sprayed coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2011, 206, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergant, Z.; Grum, J. Porosity Evaluation of Flame-Sprayed And Heat-Treated Nickel-Based Coatings Using Image Analysis. Image Analysis & Stereology, 2011; 30, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, C.; Alemohammad, H.; Toyserkani, E.; Khajepour, A.; Corbin, S. Cladding of WC–12 Co on low carbon steel using a pulsed Nd:YAG laser. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 2007; 464, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, B.; Zeng, X.; Hu, X.; Cui, K. Critical state of laser cladding with powder auto-feeding. Surface and Coatings Technology 1996, 79, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafidh, M.; Schipper, D.; Masen, M.; Vleugels, N.; Noordermeer, J. Tribological behavior of short-cut aramid fiber reinforced SBR elastomers: the effect of fiber orientation. JOURNAL OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING AND SCIENCES 2018, 12, 3700–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indhu, R.; Vivek, V.; Sarathkumar, L.; Bharatish, A.; Soundarapandian, S. Overview of Laser Absorptivity Measurement Techniques for Material Processing. Lasers in Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2018, 5, 458–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Berthe, L.; Fabbro, R.; Muller, M. Measurement of laser absorptivity for operating parameters characteristic of laser drilling regime. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 2008; 41, 155502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergant, Z.; Batič, B.E.; Felde, I.; Šturm, R.; Sedlaček, M. Tribological Properties of Solid Solution Strengthened Laser Cladded NiCrBSi/WC-12Co Metal Matrix Composite Coatings. Materials 2022, 15, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimzadeh, A.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Walsh, F.C. A review of electrodeposited Ni-Co alloy and composite coatings: Microstructure, properties and applications. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 372, 463–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements (wt.%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | Cr | B | Si | |

| NiCrBSi | 78 | 10-15 | 1.5-3.0 | 3-5 |

| WC | 60 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).