1. Introduction

PCOS is a common reproductive and endocrinological disorder that affects 6–10 percent of women and is characterized by ovulatory dysfunction, polycystic ovaries, and hyperandrogenism. Additionally, metabolic complications, including atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, obesity, dyslipidemia, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, are associated with PCOS [

1,

2]. Although its pathogenesis remains unclear, a significant amount of data shows that adipokines may play a role in the etiology of PCOS [

3,

4].

Adipokines are primarily secreted from adipocytes and play crucial roles in reproduction, immunity, inflammation, insulin resistance, and energy metabolism [

5]. Oncostatin M is a novel adipokine and a member of the IL-6 cytokine family that stimulates the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of the transcription pathway by binding to a transmembrane receptor. OSM has many biological functions, including lipogenesis/adipogenesis, hematopoiesis, osteogenesis, and inflammation regulation [

6]. It has also been shown that human oocytes and granulosa cells (GCs) express OSM and its receptor OSMR. Additionally, it has been reported that OSM has stimulatory effects on the number and growth of primordial germ cells (PGC) in the ovaries [

7]. OSM may also stimulate the production of additional growth factors that support and facilitate the development of primordial follicles. The increase in OSM signaling following HCG administration and subsequent ovulation indicates that OSM signaling plays a fundamental role in ovulation process [

8].

Therefore, in light of the current literature, we hypothesized that Oncostatin M might contribute to the pathophysiology of PCOS because of its relationship with ovulation, insulin resistance, and inflammation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients Samples

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki after receiving approval from the Balkesir University Ethics Committee (approval number: 2021193). Participants were recruited for the study after informed consent was obtained between 7.2021 and 7.2022. The patients were allocated in this study on a 1:1 ratio as PCOS group (n = 32) or control group (n = 32). This study included women between 20–35 years with a body mass index (BMI) ranging from 18 to 30. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the patient’s weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. The Rotterdam criteria were used to identify patients with PCOS for this research [

9]. The control group consisted of women with regular menstrual periods, normal ovaries on ultrasonographic evaluation, normal hormonal status, and normal Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) scores.

2.2. Biochemical Analysis

Blood samples were collected between the 3rd and 5th days of the menstrual cycle after at least eight hours of fasting, and anthropometric measurements were completed. After centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min, the serum of patients was halved, and the first part was stored at -80°C for further analysis of OSM. The second part of the serum was used to measure the level of fasting glucose, insulin, white blood cell count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), total testosterone, prolactin, and estradiol. HOMA-IR score was calculated using the following formula: fasting insulin (µU/L) × fasting glucose (mmol/L) / 405. If the score was greater than 2.4, the patient was considered insulin resistant. The non-HDL level was calculated using the formula: total − HDL cholesterol. Plasma levels of OSM were measured with an enzyme-linked immunoassay kit (E-EL-H2247, Elabscience, USA) that had a sensitivity of 9.38 pg/mL and a detection rate of 15.63–1,000 pg/mL.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical and power analyses were done using the open-source jamovi (version 2.3.21) statistical software program and G Power software, respectively. A few papers in the literature have explored OSM; therefore, the minimum sample size was calculated as 28 per group based on an α error of .05, power of .90, and effect size of .8. An independent sample T-test and the Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare variables with normal and abnormal distributions, respectively. Partial correlation analyses were performed using either the Pearson or Spearman coefficients according to the variables with normal and abnormal distributions. The diagnostic performance of Oncostatin M for PCOS was evaluated with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. A p-value < .05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

Blood samples were collected from 64 women (PCOS group, n = 32; control group, n = 32), and no significant differences were found in BMI,

TG, HDL, WBC, thyroid-stimulating hormone, prolactin, and estradiol levels between the study groups.

Table 1 summarizes the study groups' metabolic, anthropometric, and hormonal results. Non-HDL cholesterol, LDL, total testosterone, and the LH/FSH ratio were considerably higher in the PCOS group than in the control group (p < .001;

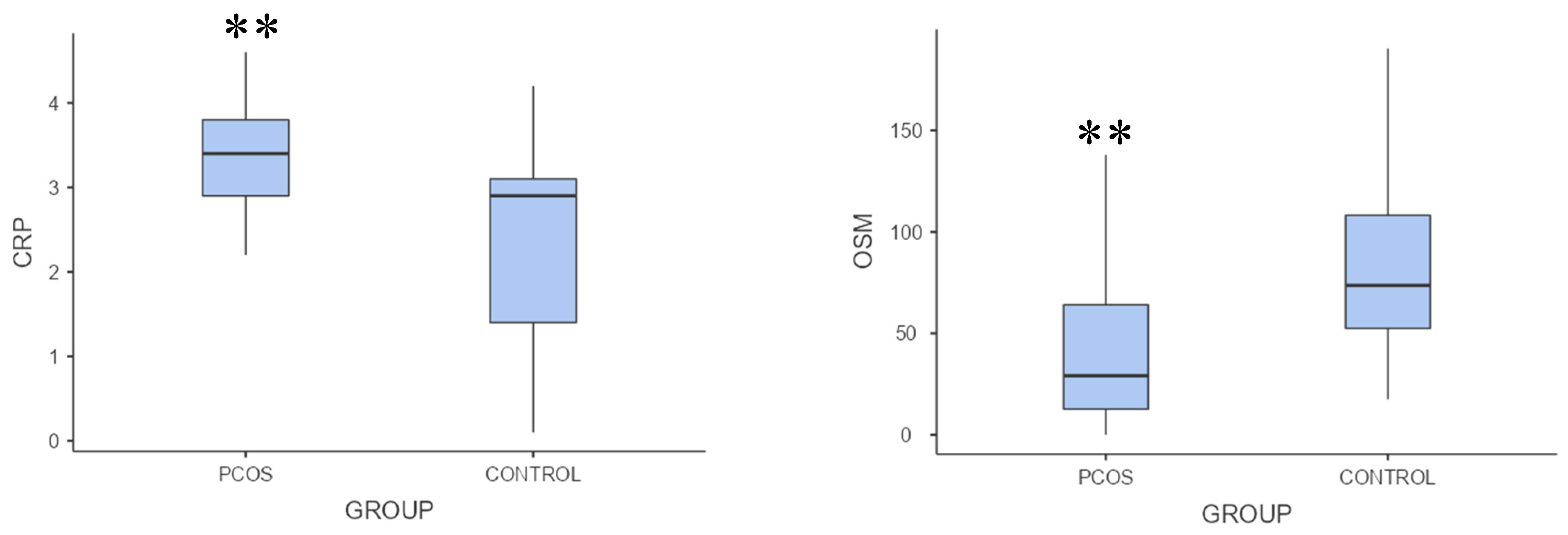

Table 1). OSM levels were significantly lower, but CRP levels were substantially higher in the PCOS group than in the control group (p = .002, p = .001, respectively;

Table 1,

Figure 1).

Regarding the association between OSM and biochemical variables, OSM was inversely correlated with fasting glucose, total cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and the LH/FSH ratio (ρ =.329, p = .017; ρ = .386, p = .005; ρ = .440, p = .001; ρ = .316, p = .023, respectively). Conversely, there was no correlation between OSM and total testosterone level (ρ = .220; p = .118).

Table 2 summarizes the correlation between OSM and biochemical markers.

In the context of inflammation and metabolic parameters, OSM was inversely correlated with CRP, HOMA-IR score, and LDL cholesterol (ρ = .353, p = .019; ρ = .275, p = .048; ρ = .470, p < .001, respectively;

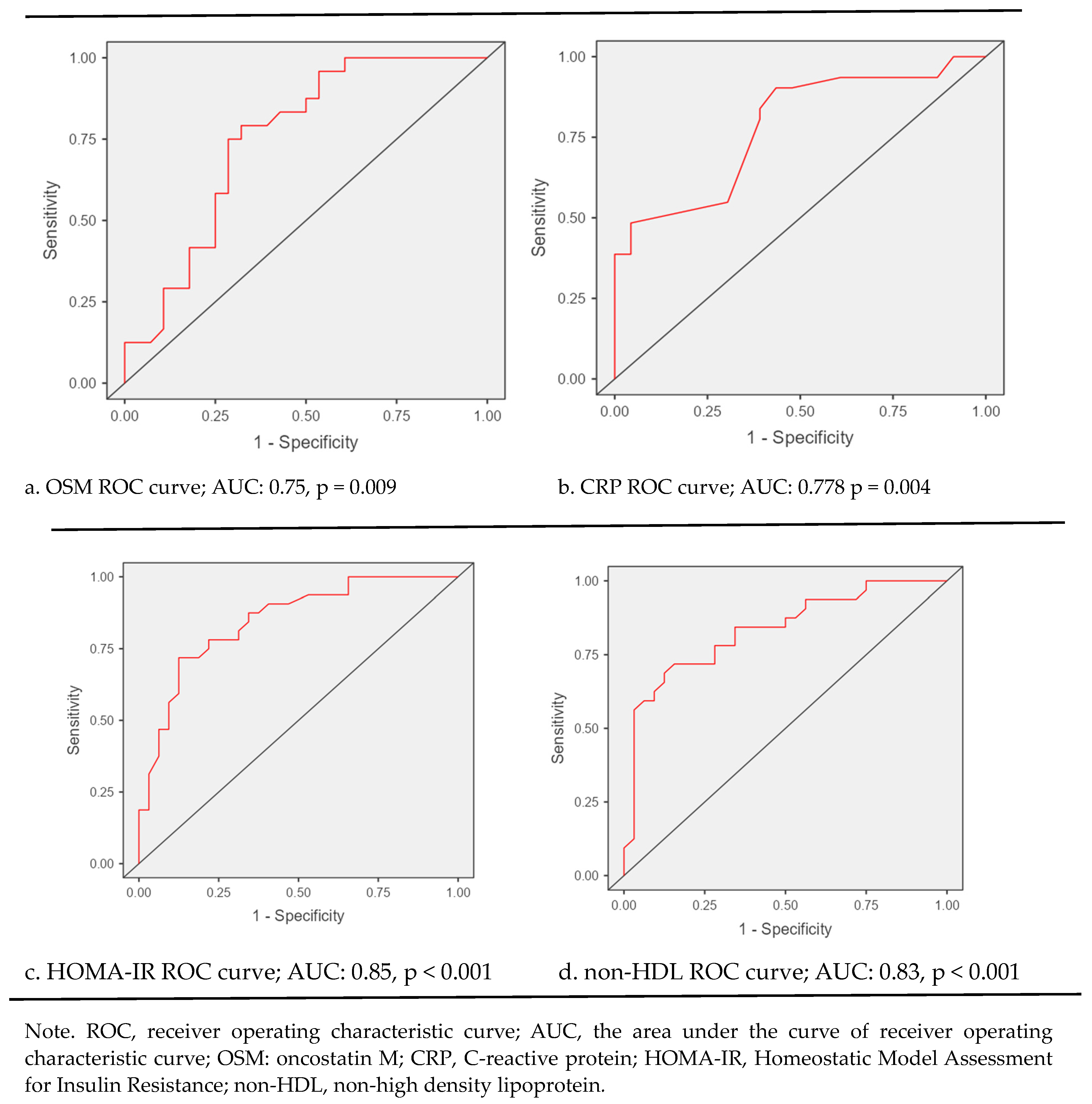

Table 2). The performance of Oncostatin M for diagnosing PCOS showed 50% sensitivity, 75% specificity, and 63% accuracy (p = .009) in ROC curve analysis. The diagnostic performance of Oncostatin M,CRP,HOMA-IR and non-HDL levels in PCOS patients are shown in

Figure 2.

ROC curve analysis unveiled that diagnostic performance of biochemical markers for PCOS is as follows: for OSM sensitivity: 50%, specificity: 75%, accuracy: 63%, p = 0.009; for CRP, sensitivity: 84%, specificity: 61%, accuracy: 74%, p = 0.004; for HOMA-IR, sensitivity: 72%, specificity: 81%, accuracy: 77%, p < 0.001; and for non-HDL cholesterole; sensitivity: 72%, specificity: 75%, accuracy: 73%, p < 0.001 (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Our study found that Oncostatin M levels were significantly lower in PCOS patients than in controls. We also found that serum CRP, HOMA-IR, and total testosterone levels were significantly higher in patients with PCOS than in the control group. We observed a significant negative correlation between Oncostatin M levels and fasting plasma glucose, HOMA-IR, CRP, non-HDL, LDL, total cholesterol, and LH/FSH ratios.

In a study published by Nikanfar S et al. [

8], patients with PCOS and healthy controls were compared in terms of Oncostatin M and Oncostatin M receptor levels in their follicular fluids, and it was found that OSM and OSMR levels in follicle fluid were significantly lower in patients with PCOS than the control group. Nikanfar S et al. [

8], in that study, attributed the decrease in oocyte maturation and the increase in the number of immature oocytes in patients with PCOS to the fact that increased SOCS3 expression interfered with the OSM and OSMR levels in the follicle fluid. Additionally, they showed that inflammatory cytokines mediate SOSC3 elevation in patients with PCOS. In this study, even though we did not investigate all inflammatory cytokines, we found that CRP levels were significantly higher in patients with PCOS than in the control group. We also observed that plasma CRP levels were negatively correlated with the plasma levels of Oncostatin M in patients with PCOS. Based on this relationship, we suppose there is inflammation in patients with PCOS [

10], which may be related to Oncostatin M, similar to the study by Nikanfar S et al. [

8]. Another study from Elks CM et al. [

11], which evaluated the relationship between Oncostatin M and inflammation, demonstrated that cancellation of adipocyte OSM signaling disrupts adipose tissue homeostasis, resulting in inflammation and insulin resistance without significant changes in fat mass. Besides, Elks CM et al. [

11] also observed that Oncostatin M treatment induced expression of Timp1, Igfbp3, and Spp1 genes, decreasing insulin resistance and other metabolic dysregulations. We think that Elks CM et al.`s [

11] study is essential in terms of providing proof for the relation of Oncostatin M with inflammation and insulin resistance similar to our research as we delineate the negative correlation between Oncostatin M, HOMA-IR index, and CRP values.

We also indicated that LDL and non-HDL cholesterol values were higher in patients with PCOS than in the control group, and these higher LDL and non-HDL values were negatively correlated with Oncostatin M levels. Some in vitro research, contrary to our study, represented that Oncostatin M directly induces dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis. For example, in their study, Liu et al. [

12] showed that OSM plays a supportive role in ox-LDL-induced foam cell formation and inflammation. Therefore,

silencing OSM may be beneficial for treating atherosclerosis. In another study by Zhan et al.,

OSMR-β deficiency in macrophages was responsible for inhibiting atherogenesis. Zhan et al. [

13] also observed that despite a fat-rich diet, there was no difference in LDL and non-HLD cholesterol levels in mice, and these mice did not develop atherosclerosis. They attributed this effect to the inhibitory nature of the absence of OSMRs in the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. We believe both in vitro studies should be validated by in vivo studies, as the interaction between statins and serum lipids may differ in the human body [

14].

Various studies have also revealed that higher serum testosterone levels accompanying PCOS may be responsible for dyslipidemia [

15] [

16,

17]. Many papers in the literature indicate that hyperandrogenemia may be associated with dyslipidemia, especially in obese patients with PCOS [

18,

19]. In our study, even though we found that serum total testosterone levels were higher in patients with PCOS than in the control group, we did not interpret the correlation between serum total testosterone and lipid levels because, in our study, patients with PCOS were not obese. We found that serum total testosterone levels were higher in PCOS patients, and we did not find any significant correlation between Oncostatin M and total testosterone levels. Although some studies have investigated the relationship between Oncostatin M and serum total testosterone levels, these studies were generally conducted on rats. Their results are controversial and few [

20,

21]. Therefore, this relationship should be examined in future studies.

The main limitation of this study is that the plasma levels of OSMR and suppressor of cytokine signaling were not evaluated because of the lack of funds that facilitated a conclusion. Despite its inadequacies, this is one of the pioneer studies that has evaluated OSM levels in patients with PCOS. Considering that only a few scientific papers have investigated the relationship between PCOS and OSM, this could be regarded as a drawback of this study in the context of drawing a comparison.

5. Conclusions

PCOS is a complex disease with biochemical or clinical hyperandrogenemia and metabolic disorders, such as higher levels of fasting glucose, HOMA-IR, LDL, and non-HDL cholesterol. In this study, the plasma level of OSM was considerably lower in patients with PCOS than in the control group, and this was correlated with the hormonal and metabolic parameters of PCOS. Oncostatin M may play a role in PCOS pathogenesis and associated metabolic complications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and E.A.; methodology, FEC and A.A.H.; software, M.A.; validation, FEC., S.A. and M.I.T.; formal analysis, S.A.; investigation, F.E.C.; resources, M.A.; data curation, F.EC.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A and G.G.; writing—review and editing, F.E.C.; S.A and G.G.; visualization, S.A.; supervision, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Balıkesir University (approval number 2021193).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guney, G.; Taşkın, M.I.; Sener, N.; Tolu, E.; Dodurga, Y.; Elmas, L.; Cetin, O.; Sarigul, C. The role of ERK-1 and ERK-2 gene polymorphisms in PCOS pathogenesis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2022, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarska, S.; Siejka, A. The pathogenesis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: What's new? Adv Clin Exp Med 2017, 26, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Li, W.; Chen, D.; Xu, Y.; Xu, A.; Ye, D. Targeting adipokines in polycystic ovary syndrome and related metabolic disorders: from experimental insights to clinical studies. Pharmacol Ther 2022, 240, 108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüler-Toprak, S.; Ortmann, O.; Buechler, C.; Treeck, O. The Complex Roles of Adipokines in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Endometriosis. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Laborde-Cárdenas, C.C.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. The Role of Adipokines in Health and Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stawski, L.; Trojanowska, M. Oncostatin M and its role in fibrosis. Connect Tissue Res 2019, 60, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddie, S.L.; Childs, A.J.; Jabbour, H.N.; Anderson, R.A. Developmentally regulated IL6-type cytokines signal to germ cells in the human fetal ovary. Mol Hum Reprod 2012, 18, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikanfar, S.; Hamdi, K.; Haiaty, S.; Samadi, N.; Shahnazi, V.; Fattahi, A.; Nouri, M. Oncostatin M and its receptor in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and association with assisted reproductive technology outcomes. Reprod Biol 2022, 22, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Mol, B.W. The Rotterdam criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: evidence-based criteria? Hum Reprod 2017, 32, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.Y.; Yu, Y.X.; Bai, X. Polycystic ovary syndrome and related inflammation in radiomics; relationship with patient outcome. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elks, C.M.; Zhao, P.; Grant, R.W.; Hang, H.; Bailey, J.L.; Burk, D.H.; McNulty, M.A.; Mynatt, R.L.; Stephens, J.M. Loss of Oncostatin M Signaling in Adipocytes Induces Insulin Resistance and Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Vivo. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 17066–17076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Jia, H.; Lu, C.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, M. Oncostatin M promotes the ox-LDL-induced activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes via the NF-κB pathway in THP-1 macrophages and promotes the progression of atherosclerosis. Ann Transl Med 2022, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Qin, J.J.; Cheng, W.L.; Zhu, X.; Gong, F.H.; She, Z.; Huang, Z.; Xia, H.; Li, H. Oncostatin M receptor β deficiency attenuates atherogenesis by inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 signaling in macrophages. J Lipid Res 2017, 58, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidnia, S.; Manayi, A.; Abdollahi, M. From in vitro Experiments to in vivo and Clinical Studies; Pros and Cons. Curr Drug Discov Technol 2015, 12, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizoń, A.; Franik, G.; Niepsuj, J.; Czwojdzińska, M.; Leśniewski, M.; Nowak, A.; Szynkaruk-Matusiak, M.; Madej, P.; Piwowar, A. The Associations between Sex Hormones and Lipid Profiles in Serum of Women with Different Phenotypes of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spałkowska, M.; Mrozińska, S.; Gałuszka-Bednarczyk, A.; Gosztyła, K.; Przywara, A.; Guzik, J.; Janeczko, M.; Milewicz, T.; Wojas-Pelc, A. The PCOS Patients differ in Lipid Profile According to their Phenotypes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2018, 126, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xie, Y.J.; Qu, L.H.; Zhang, M.X.; Mo, Z.C. Dyslipidemia involvement in the development of polycystic ovary syndrome. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2019, 58, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.; Britt, K.L.; Wreford, N.G.; Ebling, F.J.; Kerr, J.B. Methods for quantifying follicular numbers within the mouse ovary. Reproduction 2004, 127, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis, P.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Kauffman, R.P. Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS): Long-term metabolic consequences. Metabolism 2018, 86, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Ge, R.S.; Li, X. Oncostatin M stimulates immature Leydig cell proliferation but inhibits its maturation and function in rats through JAK1/STAT3 signaling and induction of oxidative stress in vitro. Andrology 2022, 10, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, L.; Tian, E.; Li, X.; Wen, Z.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Zhong, Y.; Ge, R.S. Oncostatin M inhibits differentiation of rat stem Leydig cells in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).