Submitted:

05 November 2023

Posted:

06 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and methods

Study context

Participant recruitment

Data collection

Data analysis and reflexivity

Ethical and safety issues

Findings

Participant demographics

Themes

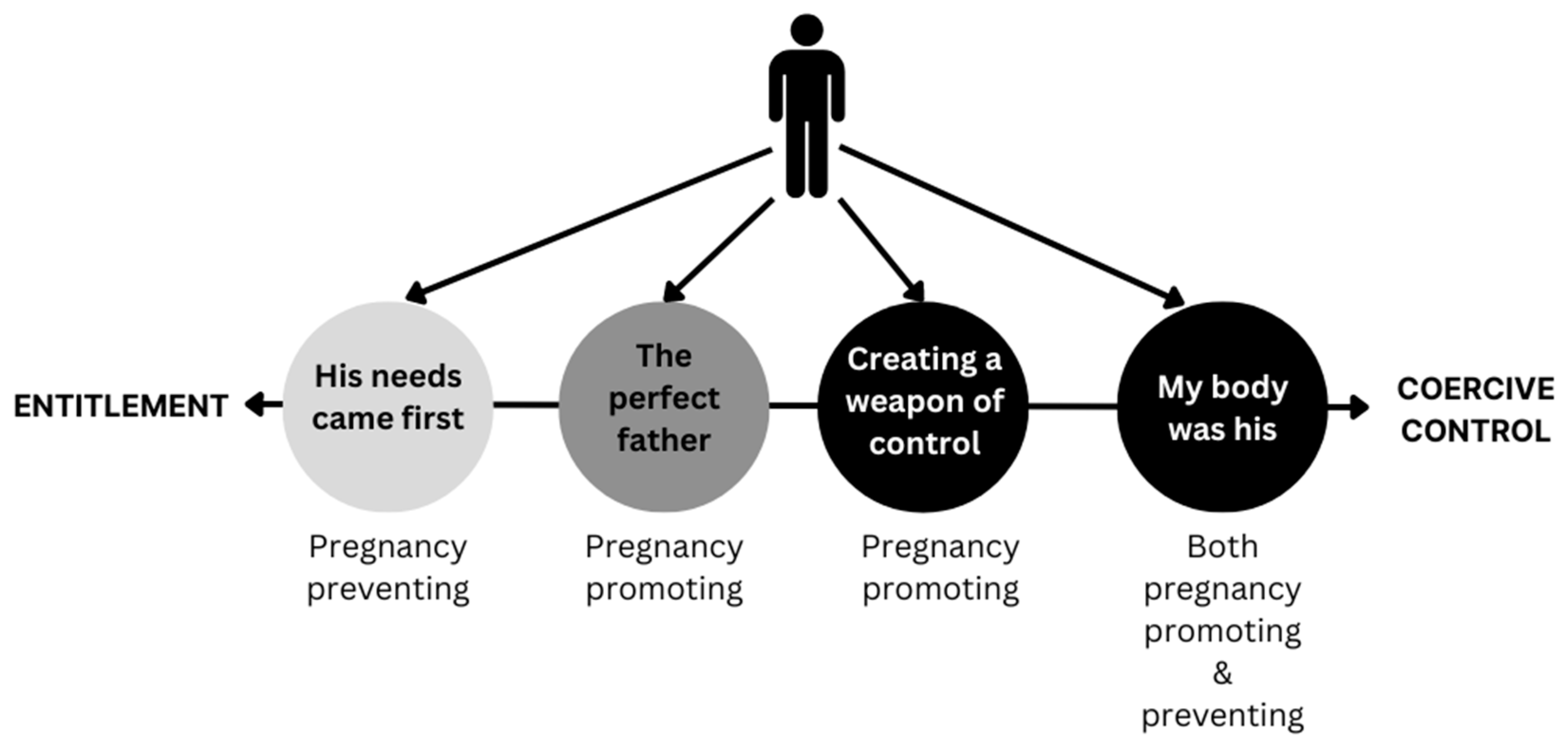

His needs came first

My ex-husband didn’t speak to me for three years… He’s wanted nothing to do with the child. It was heartbreaking… He would just say the necessaries, sort of thing, but he dropped helping in the house. He was as silently unpleasant as he could. (Participant 27)

That morning, it was like a switch flicked, it was like a totally different person. Even things like the tone of voice changed, it was like I had done this one horrible thing to him. I mean, I was on birth control, he’d been at the doctors with me where I got the birth control, it just failed. (Participant 24)

I remember saying one morning to my boyfriend at the time, he was - we were sitting at a café, and I said ‘Well what about adoption? We could think about that?’ He goes, ‘No, no, no, I do not want you walking around pregnant, people will see you pregnant and I don’t want that…People will look at me, people will think I’m a loser for being a deadbeat dad.’ (Participant 1)

I didn’t particularly want to have baby, but I also didn’t particularly want to have a termination either. I wanted to have the opportunity to talk about the possibility of having another baby. He was quite a prick about it, pretty horrible about it and really verbally abusive towards me, until I told him that I had decided to have a termination.(Participant 10)

He picked me up [from the abortion clinic] and took me back to my house and dropped me off. I was still groggy and not well and my boys were at home. And he said he had to go. He just left me there, and instantly I had to start cooking them dinner and, oh it was just horrible… If I’d get upset or sad about it, it was like, you’re not allowed to talk, don’t talk about it, look at what you’re doing, you're just, you know, trying to guilt me and trying to make me feel bad. (Participant 4)

He didn't want to be tied down, he didn't want the maintenance if I had the baby, he wanted none of the entrapment, he just wanted to be a golf professional and travel and things like that. (Participant 19)

The illusion of the perfect father

I think I was just like a workhorse to provide him with children to adore him. It felt a lot like that. (Participant 9)

He used me for reproduction…not to have a loving, committed relationship with, but because he wanted children. (Participant 20)

He felt he didn’t get taken seriously enough in life by his peers and if he was to have a child, it would, yeah, he’d be taken more seriously as well because he would be, like, more normal. (Participant 4)

I felt like he showed me off a lot to people. He was always wanting me to go places and I really didn't want to do it. It was all about showing me to everyone; family members, friends, friends he hadn't seen in years. Yeah, showing me off to people that I was pregnant. (Participant 5)

It’s a real alpha male kind of dominance thing, ‘I have all of these children which makes me more of a man than you because I can father these kids, which means I’ve got the bigger dick or bigger balls.’ (Participant 7)

He wouldn’t help with feeding them, he wouldn’t help with getting a bottle, he wouldn’t help with getting me to rest during the pregnancy. I had pre-eclampsia, but I was expected to go and do the mowing. He wouldn’t help with that. (Participant 15)

He would hold her [the baby] in public so everyone could goo and gah over him and praise him for being such a great dad. But when it came down to the crunch at home, he wasn’t interested in actually doing any of the not-so-fun work stuff. (Participant 11)

You know doing the night sleeping thing, when you try and get them to sleep through the night? So, I came back from hospital – I was really sick… He told everyone how he was up during the night looking after [the baby]…He’d tell everyone how he fed her and did all this. Instead, he was watching porn and chatting to women and wanking off [laughs]. (Participant 26)

He was an artist and we were trotted out when he was going to exhibitions. We were told we had to come and support him and show ourselves. There was this public image, basically, of the mother and the children and the supportive family. How successful he was at home and in the community. How he's a nice guy. Versus the way he would behave at home. (Participant 15)

I think his focus on his kids was a bit like they were items on a stock exchange, and if they didn’t perform, love was conditional on performance and control. In a way, I mean if you think about it, it’s the same as my relationship with him. If I didn’t perform in the way that he deemed, then love wasn’t forthcoming so to speak. (Participant 22)

He felt that I had somehow orchestrated this, that I had turned our baby into my baby and our baby's sort of unwillingness to be looked after by him or anyone else was somehow my doing; that was all in my control and that I had sort of messed up the first baby, so he was always applying pressure on me to have another one. The first one ended up being for me; the second one would be for him… [Second baby] was really fearless and social. So her dad got to interact with her a lot more and the extended family as well. So he was happy. He got - he finally got to have what he wanted out of a baby, a baby that met his needs and his expectations. (Participant 3)

Creating a weapon of of control

He saw that having a child gave him a massive amount of control. I don’t know if that's what it is, because it's not that he loves kids. (Participant 17)

I'd say he never wanted the children. He didn't want the responsibility. The children were his pawns to control me. (Participant 18)

The manipulation, the coercive control was already there…and once I was pregnant and vomiting, I was so vulnerable. So vulnerable. (Participant 9)

You can control your spouse if you know that she’s stuck at home with a baby. If you know that she’s got a baby, or she’s got a big, fat pregnant belly… If she’s stuck at home with a baby she can’t go anywhere, she can’t do anything, she can’t work, she can’t achieve things for herself, because babies are hard work and require an awful lot of time and dedication. (Participant 11)

He'd [the baby] be sleeping in the port-a-cot in the room…in the bassinet or whatever. We'd have an argument and then if the baby would wake up from the noise - I'd obviously go to the baby to pick him up and my ex would block me from going to him. So it was like the baby just became the ultimate tool to coerce me into doing things I didn't want to do or get back at me when he was angry at me. (Participant 5)

He used her – if he really wanted me to do something I didn’t want to do, it was ‘oh, [daughter] will be hurt’. (Participant 26)

He wanted the calls to go for 20, 30 minutes. He just would not hang up the phone. My son wasn't even really talking at that stage…and it felt like having him [the perpetrator] in my house. He knew the calls were making me uncomfortable because I started saying, ‘Hey, do you think we could drop the time back or do you think we could drop the frequency back or whatever?’ He was like, ‘No, I'll be calling every day. He'll get used to it’…[I felt like he was] forcing his way into my home. (Participant 5)

I was so naïve and I talk to so many parents who have no clue – they’re naïve to this too – the power a man has over a woman who has his child. I had no idea. I thought, ‘Cool, I’ll just bring up this baby all on my own because he doesn’t want anything to do with it’. [I didn’t realise] that he can just change his mind, get lawyers involved and ruin my life, basically… Did he know, secretly, that he was now going to have this control over me because I’d dared to leave him, I’d dared to call out his behaviour and say ‘This isn’t OK’ and he’s not used to that? (Participant 6)

Whenever [my son] is with me, I’m fighting a court case…It was kind of like a plan to control [my] life… Here [in Australia], until my baby turns 18, I have to deal with [him]. He's got access to me. It's very terrifying for me. (Participant 12)

My body was his

It was really scary. I wasn’t even allowed to say no to him touching me, or like have a shower with the door closed, because he had to watch me have a shower, and he would say ‘No, your body is mine, I can do what I want with it. You are just a vessel for this child’. (Participant 16)

I had no control, no control. It was nothing for me to wake up in the middle of the night with him on top of me. In the end with the children, if he didn't get what he wanted, the children copped his temper the next day. So, I had to give him what he wanted to protect the children. (Participant 18)

I had an ectopic pregnancy…and got carted off to hospital... As well as removing the embryo in my tubes, I then had to go and have a termination as well. I came out of that feeling pretty bad, and he fairly quickly, I think the day that I came home, wanted sex again. (Participant 23)

It was a control thing. ‘I can get you pregnant, now I can make you not have it.’ (Participant 10)

He coerced me into having another baby and for the first three months of my pregnancy I was really sick with morning sickness and he still forced himself onto me daily…I almost lost the baby after one event before Christmas, and at 12 weeks old, 12 weeks pregnant, I thought I was going to die…The next weekend I got out and he tried to make me have an abortion. That’s the kind of control that he wanted to have. He could make me do anything and he said, ‘I will make you do anything I want you to do.’ (Participant 16)

They [perpetrators] don’t want submissive women; they want strong women that they can break down. I think reproductive choice is – out of everything, that’s probably the one thing that I have… Maybe for men, that might be the strongest thing for them to break down on a woman because that’s I think one thing that women try and hold on to as much as possible… I think once a guy breaks down your reproductive control, then they know that they’ve pretty much won. (Participant 26)

Discussion

Implications for practice

- Practitioners who suspect or identify that patients are experiencing RCA could seek to ascertain the woman’s perception of the perpetrator’s motivation when enquiring sensitiely about their experiences. Understanding this contextual detail may help to determine her level of risk of being subjected to ongoing coercive control. Although women may not always know or understand the perpetrator’s reasoning, many are able to make an “educated guess” as they have first-hand and extensive knowledge of the perpetrator.

- Women who are being forced or pressured to have a termination against their will may not always be experiencing coercive control or be fearful for their safety; however, neither can coercive control be discounted for these women.

- Some women experience both pregnancy promoting and pregnancy preventing behaviour from the same partner, often reporting very severe controlling behaviours, physical and sexual violence.

- Women experiencing pregnancy promoting behaviours may be at elevated risk of coercive control depending on the motivation of the perpetrator. Our findings suggest that having low or no bodily or sexual autonomy, or a partner who treats children as tools of control should be treated as red flags by practitioners for more severe, controlling abuse and violence.

- Practitioners who work with men individually in counselling or behaviour change programs (or batterer interventions as they are called elsewhere) may find it useful to target particular attitudes or beliefs in their therapeutic work. Men who disclose that they have tried to control a partner’s reproductive choices could be questioned as to what drives this behaviour.

Limitations

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- Tarzia L, Hegarty K. A Conceptual Re-Evaluation of Reproductive Coercion: Centring Intent, Fear and Control. BMC Reproductive Health. 2021;18(87). [CrossRef]

- Miller E, Jordan B, Levenson R, Silverman J. Reproductive coercion: connecting the dots between partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(6):457-9. [CrossRef]

- Grace KT, Anderson JC. Reproductive Coercion: A Systematic Review. TVA. 2018;19(4):371-90. [CrossRef]

- Tarzia L, Douglas H, Sheeran N. Reproductive coercion and abuse against women from minority ethnic backgrounds: views of service providers in Australia. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2022;24(4):466-81. [CrossRef]

- Moulton J, Corona M, Vaughan C, Bohren MA. Women's perceptions and experiences of reproductive coercion and abuse: a qualitative evidence synthesis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0261551. [CrossRef]

- Suha M, Murray L, Warr D, Chen J, Block K, Murdolo A, et al. Reproductive coercion as a form of family violence against immigrant and refugee women in Australia. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(11):e0275809. [CrossRef]

- Brandi K, Woodhams E, White KO, Mehta PK. An exploration of perceived contraceptive coercion at the time of abortion. Contraception. 2018;97:329-34. [CrossRef]

- Dejoy, G. State Reproductive Coercion As Structural Violence. Columbia Social Work Review. 2019;17(1):36-53. [CrossRef]

- Graham M, Haintz G, Bugden M, de Moel-Mandel C, Donnelly A, McKenzie H. Re-defining reproductive coercion using a socio-ecological lens: a scoping review. BMC Pub Health. 2023;23(1371). [CrossRef]

- Rowlands S, Walker S. Reproductive control by others: means, perpetrators and effects. BMJ Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2019;45:61-7. [CrossRef]

- Wood S, Thomas H, Guiella G, Bazie F, Mosso R, Fassassi R, et al. Prevalence and correlates of reproductive coercion across ten sites: commonalities and divergence. BMC Reproductive Health. 2023;20(22). [CrossRef]

- Kazmerski T, McCauley H, Jones K, Borrero S, Silverman J, Decker M, et al. Use of Reproductive and Sexual Health Services Among Female Family Planning Clinic Clients Exposed to Partner Violence and Reproductive Coercion. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2015;19(7):1490-6. [CrossRef]

- Silverman J, Gupta J, Decker M, Kapur N, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi wimen. BJOG. 2007;114(10):1246-52. [CrossRef]

- Hegarty K, McKenzie M, McLindon E, Addison M, Valpied J, Hameed M, et al. "I just felt like I was running around in a circle": Listening to the voices of victims and perpetrators to transform responses to intimate partner violence (Research report, 22/2022). Sydney NSW: ANROWS; 2022.

- McCauley H, Falb K, Streich-Tilles T, Kpebo D, Gupta J. Mental health impacts of reproductive coercion among women in Cote d'Ivoire. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics. 2014;127(1):55-9. [CrossRef]

- Grace KT, Miller E. Future directions for reproductive coercion and abuse research. BMC Reproductive Health. 2023;20(5). [CrossRef]

- Munoz E, Shorey R, Temple JR. Reproductive coercion victimization and associated mental health outcomes among female-identifying young adults. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2023;Online first. [CrossRef]

- Douglas H, Kerr K. Domestic and Family Violence, Reproductive Coercion and the Role for Law. Journal of Law and Medicine. 2018;26(2):341-55.

- Stark, E. Coercive control. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- Nikolajski C, Miller E, McCauley HL, Akers A, Schwarz E, Freedman L. Race and reproductive coercion: a qualitative assessment. Women's Health Issues. 2015;25(3):216-23. [CrossRef]

- Moore A, Frohwirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(11):1737-44. [CrossRef]

- Pearson E, Aqtar F, Paul D, Menzel J, Fonseka R, Uysal J, et al. 'Here, the girl has to obey the family's decision': A qualitative exploration of the tactics, perceived perpetrator motivations, and coping strategies for reproductive coercion in Bangladesh. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health. 2023;3(100243). [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns Psychother Res. 2021;21(47-47). [CrossRef]

- Heise, L. Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(3):262-90. [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2018. Australia’s health series no. 16. AUS 221.: AIHW; 2018.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Screening for domestic violence during pregnancy: options for future reporting in the National Data Collection. Cat no PER 71. Canberra: AIHW; 2015.

- Tarzia L, Cameron J, Watson J, Fiolet R, Baloch S, Robertson R, et al. Personal barriers to addressing intimate partner abuse: a qualitative meta-synthesis of healthcare practitioners' experiences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(567). [CrossRef]

- Spangaro J, Poulos RG, Zwi AB. Pandora doesn't live here anymore: Normalization of screening for intimate partner violence in Australian antenatal, mental health and substance abuse services. Violence & Victims. 2011;26(1):130-44. [CrossRef]

- Creedy D, Baird K, Gillespie K, Branjerdporn G. Australian hospital staff perceptions of barriers and enablers of domestic and family violence screening and response. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1121). [CrossRef]

- Taft A, Hooker L, Humphreys C, Hegarty K, Walter R, Adams C, et al. Maternal and child health nurse screening and care for mothers experiencing domestic violence (MOVE): a cluster randomised trial. BMC Medicine. 2015;13(150). [CrossRef]

- de Costa C, Douglas H. Explainer: is abortion legal in Australia? The Conversation [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://theconversation.com/explainer-is-abortion-legal-in-australia-48321.

- Children By Choice. Australian Abortion Law Queensland, Australia: Children By Choice; 2018. Available from: https://www.childrenbychoice.org.au/factsandfigures/australianabortionlawandpractice.

- Low, J. Unstructured and Semi-structured Interviews in Health Research. In: Saks M, Allsop J, editors. Researching Health: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods. London: SAGE; 2019.

- Guest G, Namey EE, Mitchell ML. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research. 2013 2023/02/16. 55 City Road 55 City Road, London: SAGE Publications, Ltd. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/collecting-qualitative-data.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2019;11(4):589-97. [CrossRef]

- Campbell R, Goodman-Williams R, Javorka M. A Trauma-Informed Approach to Sexual Violence Research Ethics and Open Science. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019;34(23-24):4765-93. [CrossRef]

- Fleury-Steiner R, Miller S. Reproductive Coercion and Perceptions of Future Violence. Violence Against Women. 2020;26(10):1228-41. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan F, Humphreys C. Coercive Control During Pregnancy, Birthing and Postpartum: Women's Experiences and Perspectives on Health Practitioners' Responses. J Fam Violence. 2020;Online first.

- Johnson, M. A Typology of Domestic Violence: Intimate Terrorism, Violent Resistance, and Situational Couple Violence: UNPE; 2008.

- Denkel B, Abrahams N. 'I'm not the mother I wanted to be': Understanding the increased responsibility, decreased control, and double level of intentionality, experienced by abused mothers. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(6):e0287749. [CrossRef]

- Heward-Belle, S. Exploiting the "good mother" as a tactic of coercive control: Domestically violent men's assaults on women as mothers. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work. 2017;32(1):374-89. [CrossRef]

- Monk L, Bowen E. Coercive control of women as mothers via strategic mother-child separation. Journal of Gender-Based Violence. 2020;5(1):23-42. [CrossRef]

- Tarzia, L. Toward an Ecological Understanding of Intimate Partner Sexual Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2021;36(23-34):11704-27. [CrossRef]

- Tarzia, L. "It went to the very heart of who I was as a woman": The invisible impacts of intimate partner sexual violence. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(2):287-97. [CrossRef]

- Crossman K, Hardesty J, Raffaelli M. "He could scare me without laying a hand on me": Mothers' experiences of nonviolent coercive control during marriage and after separation. Violence Against Women. 2015;22(4). [CrossRef]

- Stark E, Hester M. Coercive control: Update and review. Violence Against Women. 2019;25(1):81-104. [CrossRef]

- McCauley H, Silverman J, Jones K, Tancredi D, MR D, McCormick M, et al. Psychometric properties and refinement of the Reproductive Coercion Scale. Contraception. 2017;95(3):292-8. [CrossRef]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith S, Walters ML, Merrick MT, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta USA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,; 2010.

- Alhusen J, Bloom T, Anderson J, Hughes RB. Intimate partner violence, reproductive coercion, and unintended pregnancy in women with disabilities. Disability and Health Journal. 2020;13(2):100849. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).