2.1. Methods of the Acoustic Nonlinearity Measuring

As the main approximation, we will consider a microinhomogeneous liquid in a homogeneous approximation, namely: we will consider the wavelength of sound

much larger than the average distance

l between heterogeneous inhomogeneities (bubbles, suspensions, plankton, etc.), which, in turn, is much larger than the radius of inhomogeneity

R, i.e.

. We also require that the sound scattering sections on inhomogeneities

(including the resonance of bubbles) do not overlap, i.e.

. In addition, we consider the amplitudes of the pumping waves

and

with frequencies

and

not too large so that we can ignore the effects of nonlinear attenuation and use the constant pumping approximation [

2,

3,

5]. Under the assumptions made, the equation describing the generation of a quasi-plane wave of difference frequency

can be written as [

3,

7,

10].

Here

is an effective nonlinear parameter that takes into account the nonlinearity of a pure liquid and the nonlinearity introduced by micro-inhomogeneities.

An important parameter for determining

is the distance at which nonlinear effects develop – the rupture distance in the wave. The nonlinear acoustic parameter ε is directly related to the Riemann solution [

3] in the evolution of simple waves, according to which the propagation velocity of a simple wave is

, where

is the adiabatic speed of sound,

v is the velocity of particles in the wave. The appearance of the dependence of the wave propagation velocity on its amplitude leads to distortions of the wave profile up to the formation of shock waves. The distance at which a plane harmonic wave degenerates into a shock wave is commonly called the rupture distance

r*, which is determined by the ratio [

3]

, where

is the wave number,

is the Mach number. By measuring the distance

r* at which nonlinear harmonics appear in the wave, it is possible to determine the nonlinear acoustic parameter ε by the formula [

33,

34]:

In practice, a relative method of measuring a nonlinear acoustic parameter is often used, which consists in preliminary calibration of the meter in a known medium and then calculations

according to the formula

, where

and

are the values corresponding to the reference sample [

34],

is the amplitude of the signal in real measurements.

A more universal method that allows measuring the frequency features of the acoustic nonlinearity parameter is to measure the amplitude of the waves of the difference frequency

РΩ and pumping

Рω at a different distance

r. The basis of the method is based on the solution [

3], which can be written as:

where

is the rupture distance,

is the sound absorption coefficient at the frequency ω. It can be seen from formula (4) that the amplitude of the second harmonic increases to a distance

, where it has a maximum equal to

, and then abruptly decays, obeying the exponential law. The latter solution is valid when

, i.e. when the attenuation length is less than the rupture length. Very often the opposite case occurs when

. Then the solution is valid only at small distances

, when nonlinear effects do not have time to develop. In this case, using

, the following simple expression

is obtained. We will consider the behavior of the wave only on a linear section

, while it is more convenient to switch to pressure

, then we get

In the more complex and most practically important case of using a biharmonic signal with frequencies

and

it can be shown that in a linear section

, the generation of a signal with a difference frequency

is described by the formula

Parametric emitters of PE, combining broadband with maintaining high directivity in a large frequency range, have recently acquired an important role in hydroacoustics [

2,

3,

5]. The calculation of the amplitude of the difference frequency wave can be obtained using equation (2), which includes the acoustic nonlinearity parameter in the right part. Thus, the efficiency of PE is related to the magnitude and therefore PE can be used to determine the magnitude of a nonlinear acoustic parameter [

7,

23,

34].

As a result of solving equation (2) under the assumptions made above, it is possible to obtain several limiting expressions for the difference frequency wave field, from which it is possible to obtain the corresponding expressions for, allowing in practice to calculate the nonlinear parameter by the following formulas:

a) valid for the far field in the Berktay mode of a parametric emitter [

2,

3,

5]:

where

RF=kωd2/8 is the Fraunhofer parameter,

DΩ=kΩ d/4,

γE = 1.78 is the Euler constant,

,

and

are the damping coefficients of the pump wave and the difference frequency wave, respectively;

b) in conditions when the nonlinear interaction zone is determined not by the spherical divergence of the beams, but by attenuation at the pumping frequency, which corresponds to the Westervelt regime, the nonlinear parameter

is determined by the formula

which, along with the above values, also includes the sound absorption coefficient at the pump frequency

, previously measured in each experiment.

The most practical method is considered to be Berktay mode. In this mode, most of the PE used in practice operate in the pumping frequency range of 100-300 kHz. Here it is necessary to take into account the divergence of the biharmonic pumping beam in the far field with relatively weak absorption at a high frequency. In this case, the nonlinear parameter can be determined by the following formula [

23,

33,

34]:

where

,

,

are the pressure amplitudes of the pumping waves with frequencies

and

, and the difference frequency

Ω (

,

,

),

,

=1.78 is the Euler constant,

is the length of the near zone at the frequency

,

,

d is the aperture of the emitter.

2.2. Effective Parameters of a Microinhomogeneous Liquid

The basic assumptions of the homogeneous continuum model, formulated in

Section 2.1, make it possible to write effective parameters of a micro-homogeneous fluid without detailed knowledge of its structure. Thus, the effective density

is obtained directly from the condition of preserving the mass of a unit volume of a micro-homogeneous liquid in the form of [

3,

33]

where

and

are, respectively, the density of liquid and gas in phase inclusions (bubbles, suspensions, etc.), the strokes hereafter refer to the phase inclusions,

is the volume concentration of the inclusions,

is the size distribution function of the inclusions. The effective compressibility of a microinhomogeneous liquid

, taking into account the resonant and relaxation characteristics of the inclusions, is [

33]

Here the value

means an integral expression

, which in the case of constancy

we have

. The value of

is the adiabatic constant,

and

are the heat capacity at constant pressure and volume, respectively,

is the coefficient of isothermal compressibility, which differs from the coefficient of adiabatic compressibility

by an amount

, where

,

and

are the temperature, pressure and entropy,

is the coefficient of thermal expansion at constant pressure. The compressibility of the inclusion

differs from the adiabatic and isothermal compressibility and takes into account the resonant properties of the inclusion (for example, the resonant frequency of bubbles

) and thermal relaxation depending on the frequency of the sound and the size of the inclusion in the form of [

14,

33]:

where

is the wave number of the heat wave,

is the coefficient of thermal conductivity of the gas,

is the slope of the adiabatic curve,

is the coefficient of kinematic viscosity of the liquid,

is the coefficient of surface tension for the inclusion. The compressibility of the inclusion

in the limit of small sizes tends to isothermal compressibility

, at large sizes tends to adiabatic compressibility

, while at resonance

the absolute value of compressibility increases sharply, increasing approximately by a factor

.

A generalization of Wood's formula for the effective speed of sound

in a microinhomogeneous liquid is written in the form [

3,

14,

33]

, from where the real part

and the imaginary part

determine the phase velocity

and the absorption coefficient

of the pressure wave in the form:

where

is the absorption coefficient of sound in pure liquid without any inclusions. In particular, for a liquid with bubbles for which

and

, formulas (17) and (18) are simplified

Depending on the volume concentration of bubbles

, simpler formulas can be obtained

Taking into account formula (1) for the nonlinear parameter

and using formulas (12)-(16), it is possible to calculate the effective nonlinear parameter

of a microinhomogeneous fluid with inclusions. Previously, using formulas (12)-(16) , it is possible to calculate the derivative

, which in the case of non - resonant bubbles (

) is equal to

where

is the adiabatic compressibility of gas in bubbles

. In the general case of a liquid with bubbles, the expression for the nonlinear parameter takes the form:

where

. In the case of non -resonant bubbles , the following expression can be obtained

which has a maximum at

and approximately equal to

.

By making further simplifications and leaving only the resonant characteristics and the main contribution to the scattering amplitude associated with the monopole component of the inclusions vibrations, it is possible to calculate a parameter

that will depend on the structure of the medium, as well as on the dynamic properties of the inclusions. In the case of gas bubbles , the value

is defined as

The contribution to the sound absorption coefficient

caused by bubbles can be presented in the following form taking into account formula (20) [

14,

33]:

As can be seen from formulas (26) and (27), to determine the acoustic characteristics of a liquid with bubbles, the form of the function

g(R) in the widest possible range of variation of

R is important. Data on sound scattering at various frequencies, including full-scale measurements in the near-surface layer of the sea saturated with bubbles, revealed the structure of the bubble size distribution function

g(R), which according to [

14,

33,

35] can be represented by the formula:

where for sea conditions

(here

L is given in meters, wind speed

at an altitude of 10 m is given in m/s), the indicator

m depends on the state of the sea,

, but for moderate and calm waves

. According to formula (28), the function

has a maximum, which is located at

microns, while the value

depends on the depth. At the same time for

there is a power dependence of the bubble size distribution function with an exponential decline with depth. Thus, formula (28) takes into account the decline of the function

g(R) at small

R, the presence of a maximum at

and the limitation of the spectrum from above by the maximum bubble size

. The advantage of such a record

g(R) is the practicality and speed of calculations of various parameters of the medium [

16,

33]. It is also important that the exponent

and the critical dimensions

and

are natural parameters that follow from the Garrett–Lee–Farmer theory (GLF) [

36]. Measurements of

g(R) on a large factual material under similar conditions of moderate sea conditions give values

in the interval

[

14,

16,

33,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], which is close enough to the estimate

obtained for the inertial interval between the sizes

and

, following from the theory of GLF [

36].

2.3. Cavitation Strength and Nonlinear Acoustic Parameter of the Liquid, General Relations

The relationship between the cavitation strength

and the nonlinear acoustic parameter

of the liquid was discussed in [

41], in which a dependence of the following form was obtained:

where

,

is the hydrostatic pressure in the liquid,

is the threshold pressure of cavitation in the liquid,

is the compressibility of the liquid. For a pure liquid, the expression

essentially represents the intramolecular pressure from the Van der Waals equation of state and, taking into account the mechanism of thermal heterophase fluctuations, can be written as [

42]

where

is the surface tension coefficient,

is the Boltzmann constant,

is the intensity of nucleation, i.e. the number of growing embryos of a new phase per unit volume per unit time, usually take the value

cm

-3s

-1, then

. For water

MPa and from (30) it follows

that it is consistent with the values for pure water.

Equation (29) is also generalized to the case of a microinhomogeneous liquid containing phase inclusions. Then, in the Equation (29), the parameters

and

should be replaced everywhere by the

and

– effective nonlinear parameter and compressibility of the liquid with inclusions, determined by Equation (11) and Equations (24) – (26). Taking into account these dependencies, we can write the following formula for cavitation strength

where

x is the volume concentration of bubbles, δ is the attenuation constant of resonant bubbles at the frequency ω. It follows from (31) that when

we have

At high concentrations of bubbles,

, the cavitation strength tends to a minimum value

from where we get

Pa.

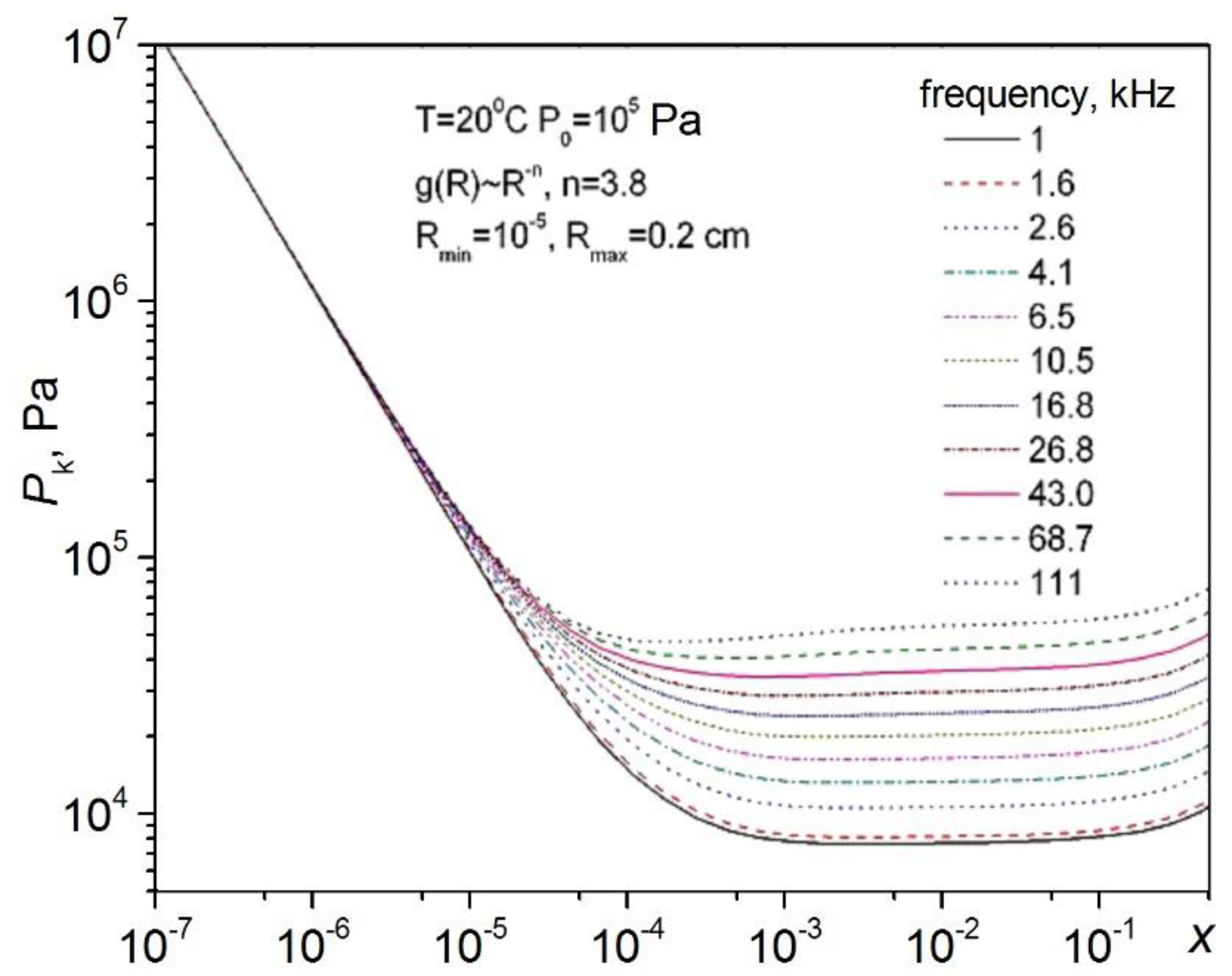

Figure 1 shows a typical dependence

in a wide range of values for water at 20

0C at different frequencies of the acoustic field causing cavitation. The hydrostatic pressure is 0.1 MPa. It can be seen that with an increase in frequency, the cavitation strength increases, and with an increase in the concentration of bubbles, it first decreases sharply, and then when the concentration exceeds the value of 10

-4, stabilization occurs – striving for a constant value of cavitation strength, regardless of the concentration of bubbles.

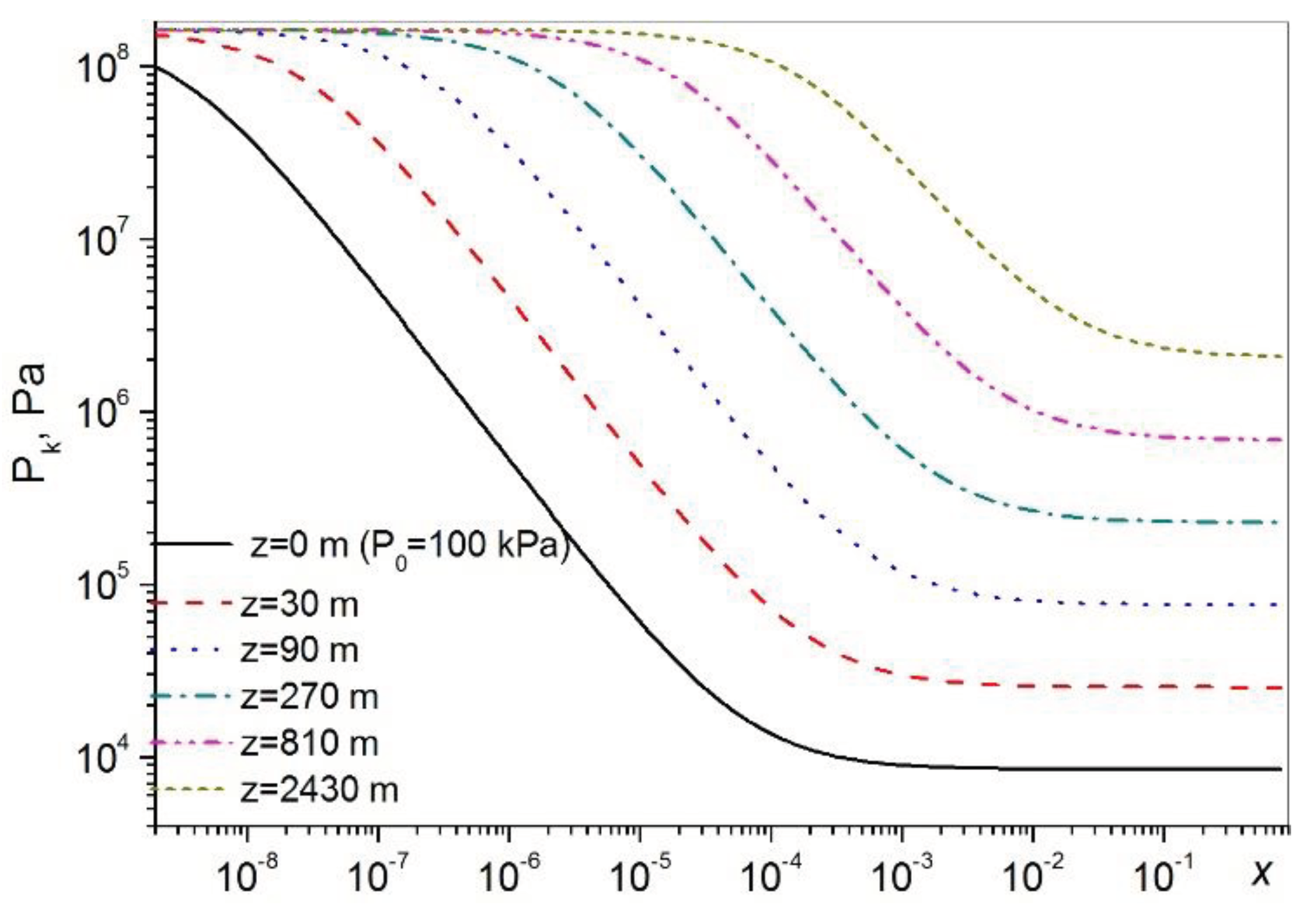

Let us consider the concentration dependence

at different pressures as a model for studying the behavior of the cavitation threshold at different depths in the sea.

Figure 2 shows a typical dependence of low-frequency cavitation strength

in a wide range of values

at various hydrostatic pressures. It can be seen that with an increase in hydrostatic pressure, the cavitation strength increases.

2.4. Rectified Gas Diffusion and Bubble Growth Thresholds – Gas Cavitation Threshold

In the previous section, we talked about the threshold of the so-called vapor cavitation in a liquid, in which the threshold is determined by the creation of a critical nuclei and its further growth in the liquid without taking into account the diffusion of gas into the bubble under the influence of sound. Often in practice, the liquid contains gas bubbles that have formed in the liquid due to the presence of dissolved gas in it. The threshold for the formation of a critical nuclei and its further growth under these conditions depends on the concentration of the dissolved gas relative to the equilibrium concentration of dissolution in the liquid of this gas [

43].

To calculate the threshold, it is necessary to calculate the compressibility of the bubble

taking into account the effects of gas diffusion. In the expression for the compressibility of inclusion

, terms related to relaxation due to the processes of gas diffusion exchange in the dynamics of bubbles should be added, when periodically alternating processes of gas exchange occur through the surface of the bubble with gas dissolved in the liquid. In this case, refined expressions for compressibility

should be added to Equations (12)- (16). To do this, we will use small values of the typical equilibrium concentration of dissolved gas in a liquid

. In addition, attention should be paid to the smallness of the diffusion coefficient

m

2/s, finally we get

where

. It can be seen from (34) that the additional term begins to play a significant role only at radii smaller by about an order of magnitude of the diffusion wave length in a liquid, i.e. at

. Thus, it turns out that at high frequencies, the contribution of diffusion to the intrinsic compressibility of the gas bubble can be neglected. However, at low frequencies with a slow gas diffusion process for small bubbles, it can play a significant role, as can be seen from formula (34).

Solving the equations of dynamics of a vapor-gas cavity in a liquid with dissolved gas averaged over the period of the sound field, it is possible to obtain expressions for the average values of physical quantities in a liquid and in a bubble [

44,

45,

46,

47]. The crosslinking of the obtained values at the boundary makes it possible to determine the change in the time averages of the values set on the surface of the vapor-gas bubble. Note that these changes are quadratic in the amplitude of the sound field.

where in the form

and

are indicated by supersaturation with gas and overheating of the liquid on the surface of the bubble. The mechanisms of rectified mass transfer, quadratic in the amplitude of the sound field, are contained in the sum

and discussed in a number of papers [

8,

20,

24,

48].

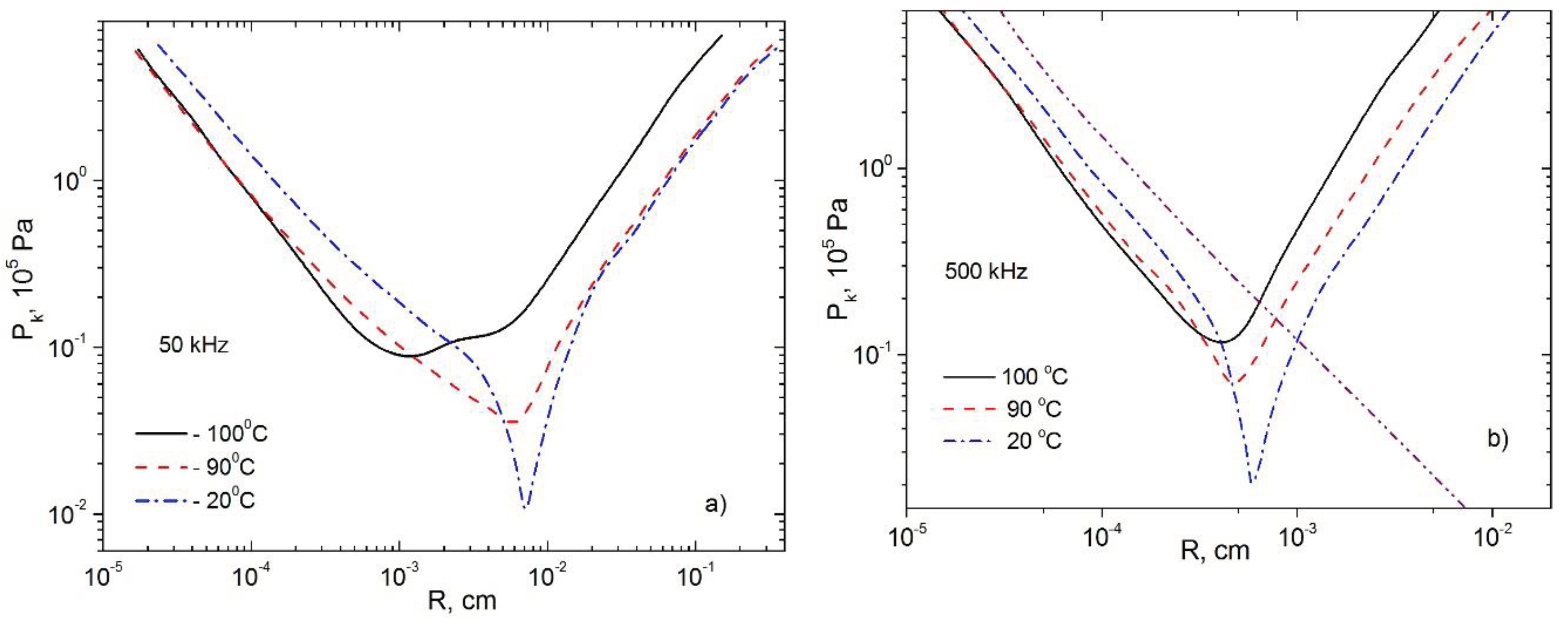

Figure 3 shows the growth thresholds

depending on the radii of the bubbles and the frequency of the sound field in water at different water temperatures (at different gas concentrations in the bubbles). It follows from

Figure 3 that near the Minnaert resonance and the second maximum of the function

, the dependence

takes minimal values. It should be noted that the threshold

in this area may be significantly lower than the known Blake threshold [

8], determined by an approximate formula

and represented in

Figure 3b by a dashed line. The growth threshold

depends in a complex way on the parameters of the medium and the frequency of the external field.

.

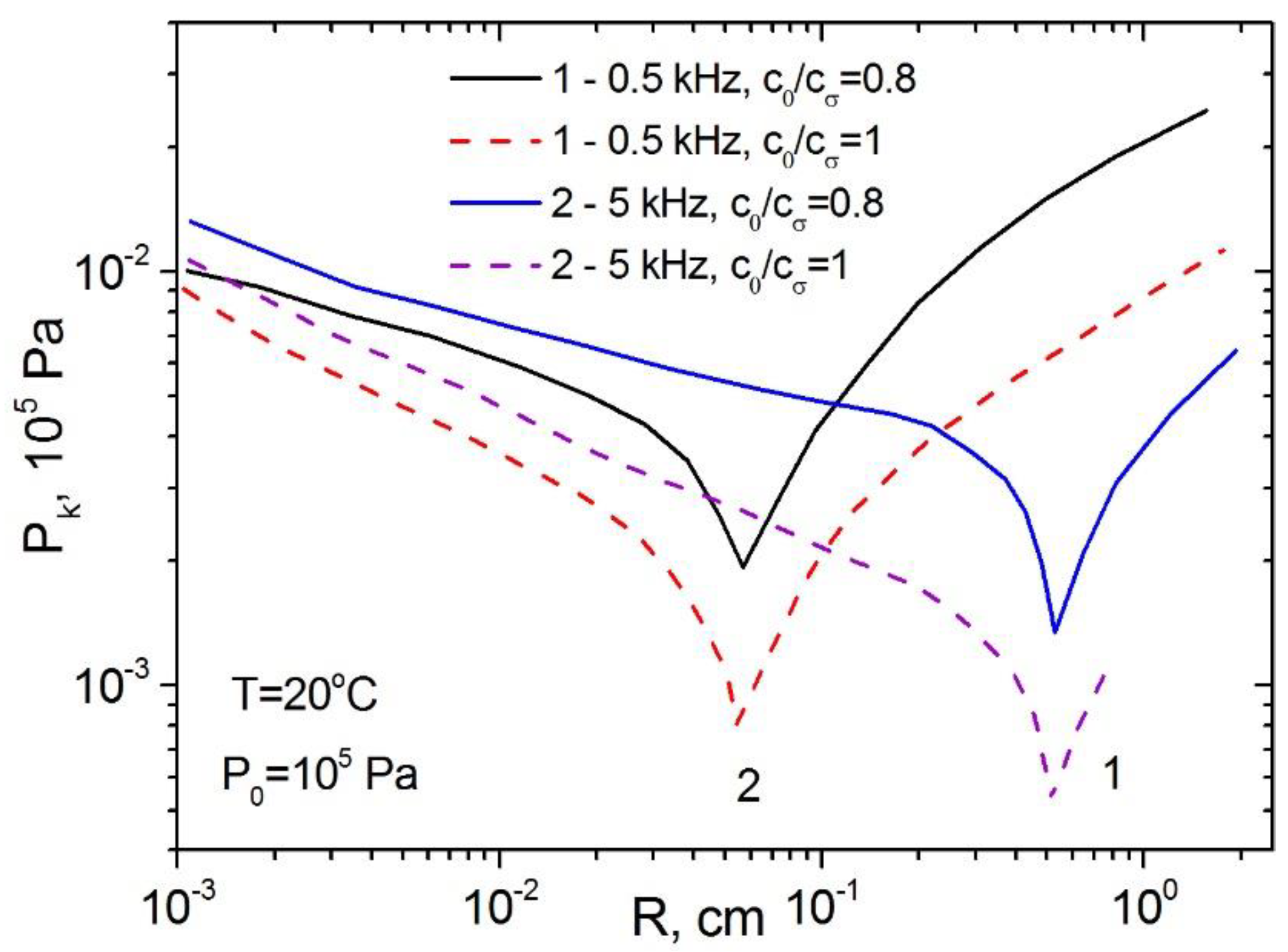

Figure 4 shows the dependences of bubble growth thresholds at different concentrations of gas

dissolved in the liquid, respectively, below the equilibrium concentration for a given temperature and external pressure in the liquid and equal to the equilibrium concentration

.

Figure 4 shows that the threshold for the growth of vapor-gas bubbles decreases sharply with an increase in the concentration of gas dissolved in water. Thus, the mechanism of rectified diffusion of gas simultaneously with the mechanism of rectified heat transfer turns out to be essential for vapor-gas bubbles and therefore the concentration of gas dissolved in a liquid should always be taken into account when comparing theoretical and experimental results.

2.5. Experimental Methods and Equipment

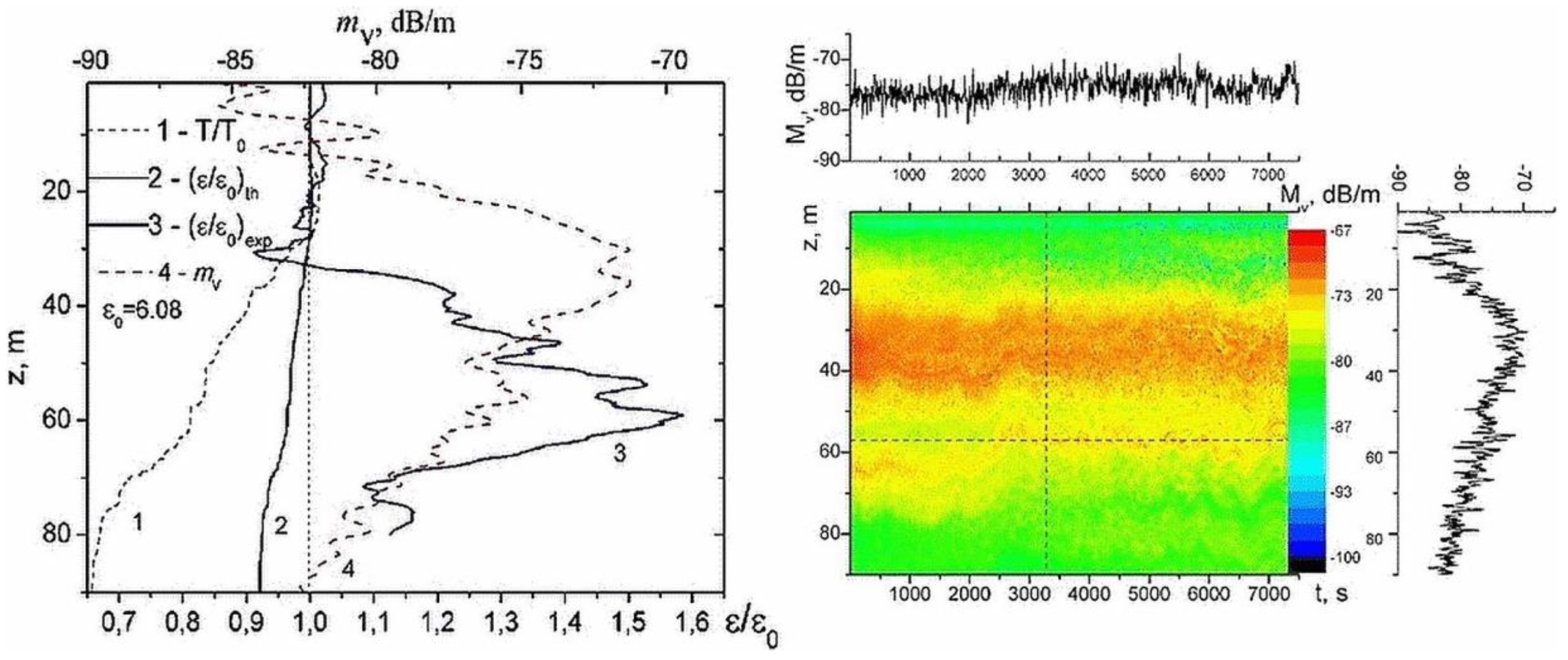

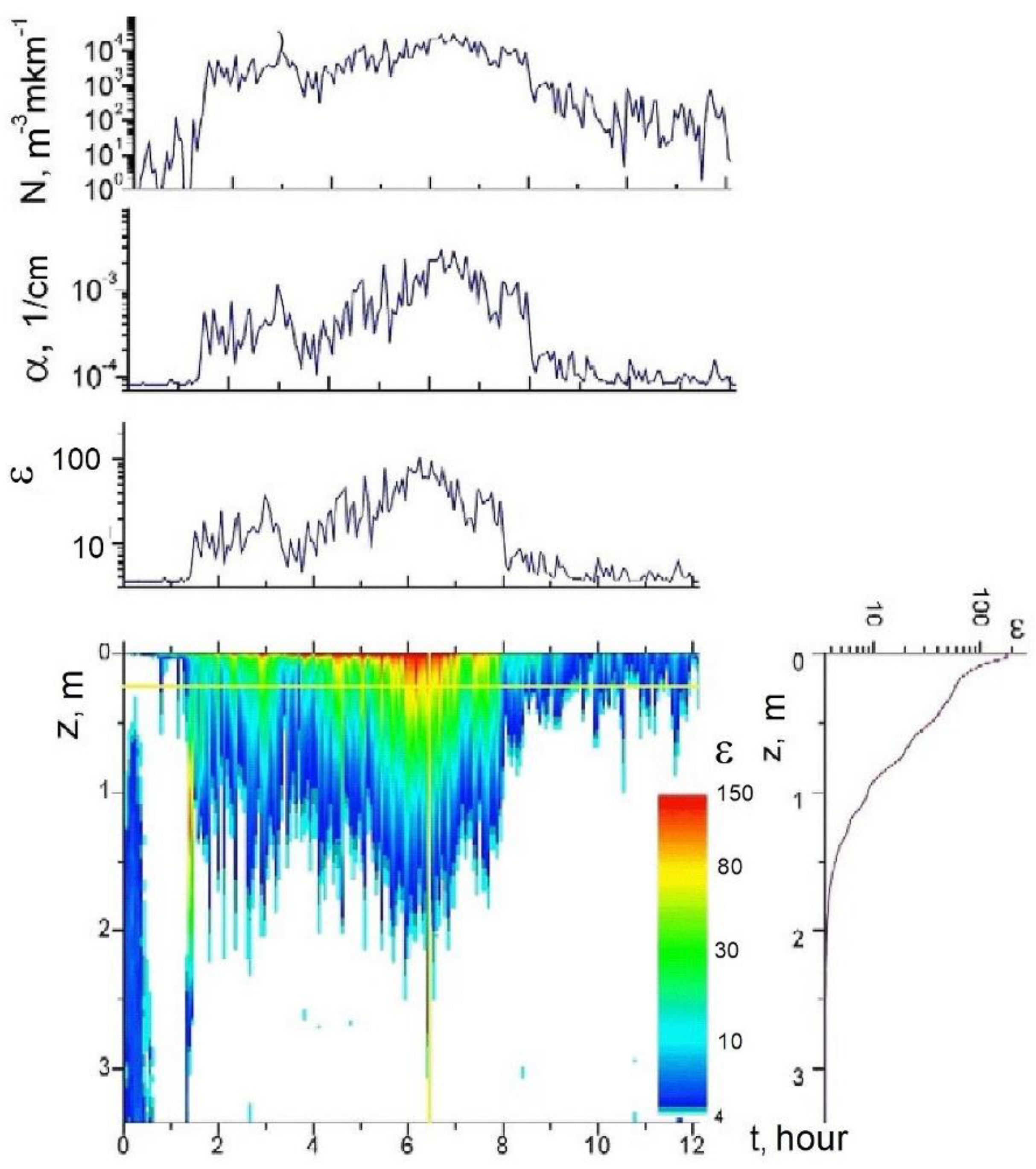

Measurements of the nonlinear parameter according to the method described above according to Equation (9) were carried out for the first time in the V.I. Il'ichev Pacific Oceanological Institute Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (POI FEB RAS) in 12 and 16 expedition cruises of the RV "Academician Alexander Vinogradov" (1988, 1990) in the frequency range from 4 to 40 kHz at various depths [

23,

33]. The experimental setup for measuring the nonlinear parameter in various waters of the voyage included an outboard part with receiving and transmitting acoustic antennas and a measuring electronic part connected to each other by connecting cables. The outboard part was a square platform with a side length of 1 m made of foam 30 cm thick, to which an acoustic parametric antenna was attached using a thin halyard. The length of the antenna suspension could vary. Radiation in the working position occurred upwards, towards the surface. The receiving antenna recorded the signal reflected from the water surface. A raft with an antenna could be released from the side of the vessel on an exhaust halyard at a distance of up to 150 m. The sending signal and the echo signals from the receiving antenna were transmitted via separate cables to the electronic measuring part on board the vessel.

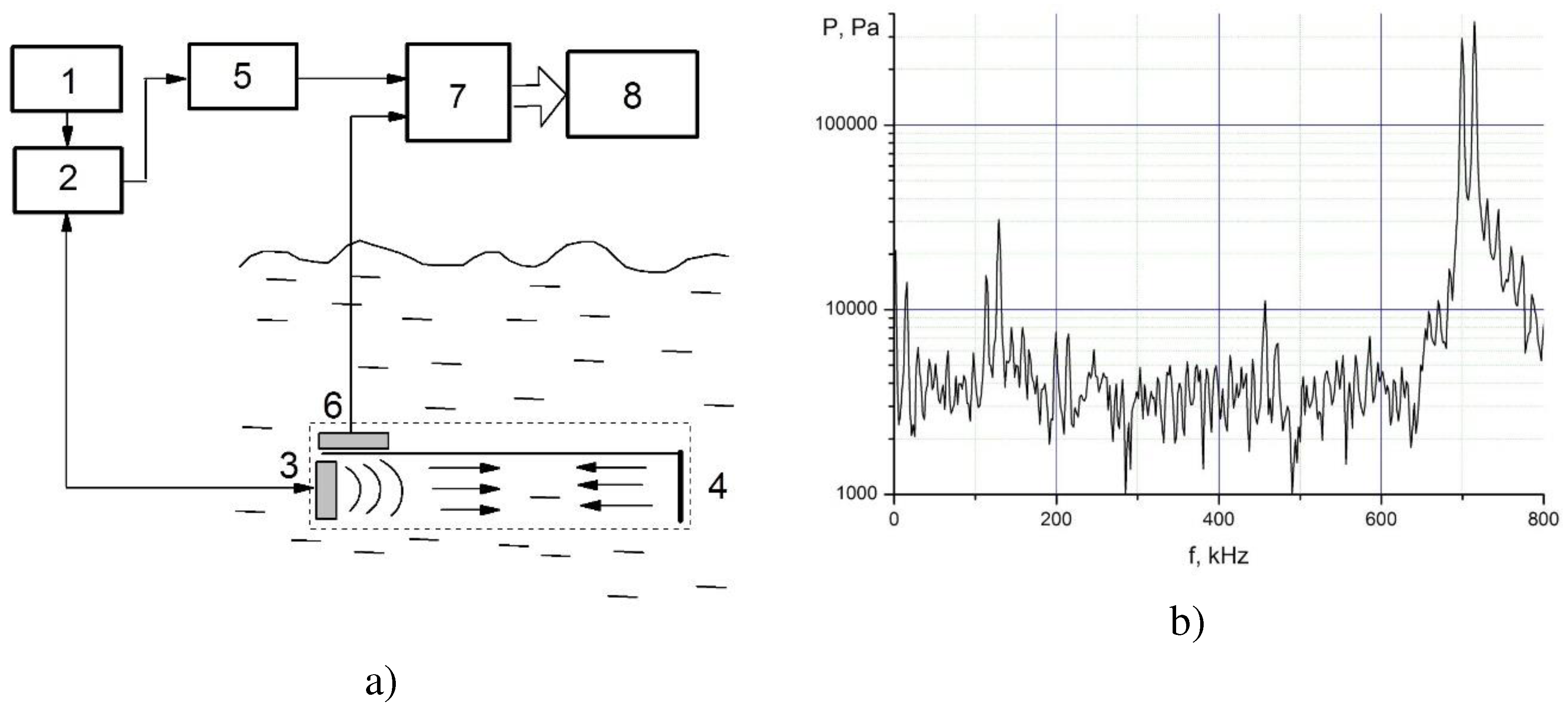

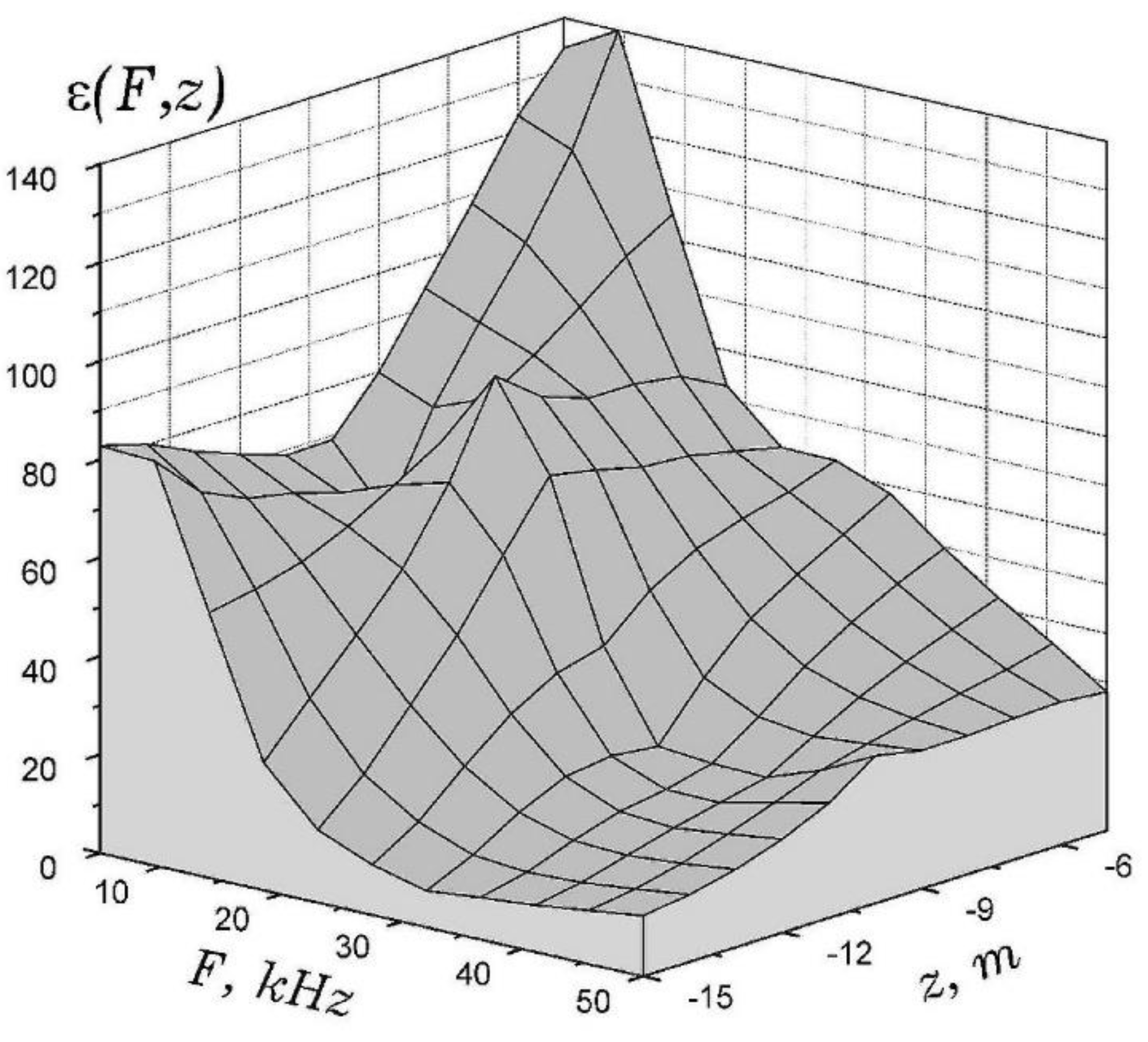

Subsequently, to study the distribution of nonlinearity at great depths, a nonlinear acoustic probe was created, the main elements of which are a parametric emitter and a cell of a certain length, inside which a biharmonic sound pulse propagates [

34] emitted by a parametric emitter. To study the fine structure of the near-surface layer of seawater, the probe makes measurements in a small layer of water limited by the cell length, while in the process of lowering (or lifting), a layer-by-layer measurement of a nonlinear parameter, the volume scattering coefficient and sound attenuation occurs. Thus, the researcher obtains a fine structure of water with a high spatial resolution.

The essence of measurements in the probe is that the emitted biharmonic pulse propagates in a space bounded on the one hand by a reflecting plate, and on the other hand by the emitter itself. The pulse is repeatedly reflected from the plate and the emitter, makes a large run in a small volume of space, while the accumulation of nonlinear effects occurs, in particular, the growth of a non-linearly generated wave of difference frequency. The selective amplifier of the receiving path allocates the difference frequency, digitizes it and transmits it to the processing processor. The attenuation coefficient is measured by the decay of the amplitude of the repeatedly reflected pulses of the pumping frequency.

Figure 3 shows the functional diagram of the probe and the frequency spectrum on the receiving hydrophone when the parametric emitter emits a biharmonic signal of 698 kHz and 716 kHz. The submerged probe itself is a 70 cm long rod, at one end of which a parametric emitter is fixed, the radiation axis of which is directed along the axis of the rod towards the reflecting plate fixed at the opposite end. A parametric piezoceramic emitter with a resonant frequency of 650 kHz has a diameter of 66 mm and a directivity characteristic width of 2 degrees. A digital programmable arbitrary waveform generator GSPF-053 was used in the radiation path, the signals of which were amplified by a U7-5 power amplifier and additionally by a radiation unit with a built-in signal switch that allows receiving a pulse reflected from the plate in pauses between parcels. The operating frequency range of the pump is in the range of 650-750 kHz. The reception path of the nonlinearity meter is based on the selective amplifier SN-233, which allows you to qualitatively separate the acoustic signals of the difference frequency of the nonlinearity meter from the pumping signals, and has a gain of up to 10

6. Data entry into the computer was carried out using a 12-bit multichannel ADC board L783, manufactured by L-Card with a maximum quantization frequency of 3 MHz.

2.7. Acoustic Cavitation Criteria and Cavitation Strength of Seawater

Experimental studies of the cavitation strength of seawater were carried out using an acoustic radiator in the form of a hollow cylinder with a resonant frequency of 10 kHz. Cavitation was recorded by acoustic noises inherent in the cavitation regime [

18]. The noises were recorded using measuring hydrophones of the company "Akhtuba" (operating frequency band 0.01-300000 Hz) and the company Bruel& Kjaer, type 8103 (operating frequency band 0.01-200000 Hz). The signals were recorded digitally using a multichannel 14-bit E20-10 card from L-card with a maximum digitization frequency of 5 MHz. High voltage was applied to the emitter at a resonance frequency of 10.7 kHz using a Phonic XP 5000 type power amplifier with a maximum power of 2 kW and adjustable inductance compensating for the capacitive load at the resonance frequency. When probing in marine conditions, the hydrophone was attached from the outside of the concentrator near the free end. The relationship between the acoustic characteristics measured by the hydrophone outside and inside the radiator was previously established. Appropriate amendments were subsequently made to the readings of the external hydrophone during experiments in marine conditions.

When conducting cavitation studies, special attention was focused on studying the dependence of the cavitation threshold on various criteria for detecting a discontinuity in seawater: by the nonlinearity of the radiated power curve at the frequency of the radiated signal

, by the second harmonic

, by the total higher harmonics

, as well as by the subharmonics

and

[

8,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

22].

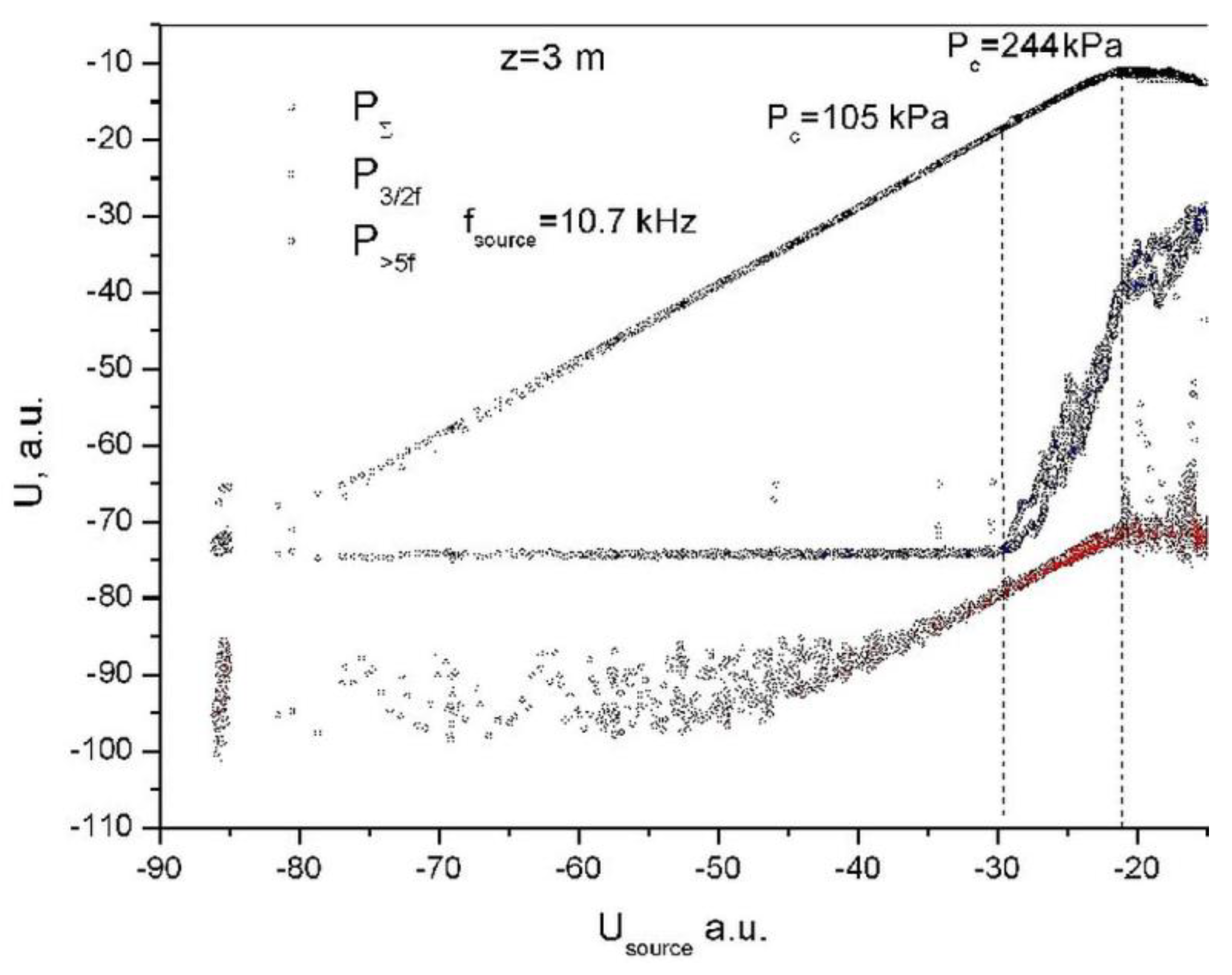

Figure 10 shows the dependences on the emitter voltage of various spectral components of acoustic noise: the subharmonic signal

at a frequency of

, the total higher harmonics

, as well as higher harmonics

, starting from the 6th harmonic. The depth at which the model of the cavitation strength meter was located was 3 m.

It can be seen from

Figure 10 that it is possible to clearly distinguish 2 cavitation thresholds that differ by more than 2 times: by the curve bend

and by the beginning of the asymptotics of all the listed curves and, especially, the curve

. The first threshold corresponds to the beginning of cavitation, and the second threshold corresponds to the beginning of violent cavitation, accompanied by a sharp decrease in acoustic impedance. Thus, the criterion of the cavitation threshold is to a certain extent quite conditional. Nevertheless, from the standpoint of detecting precisely the beginning of cavitation, as the beginning of the discontinuity of the continuity of the liquid and the beginning of the formation of bubbles in the liquid, the cavitation strength of the liquid in this example can be considered the first threshold, which is

kPa.

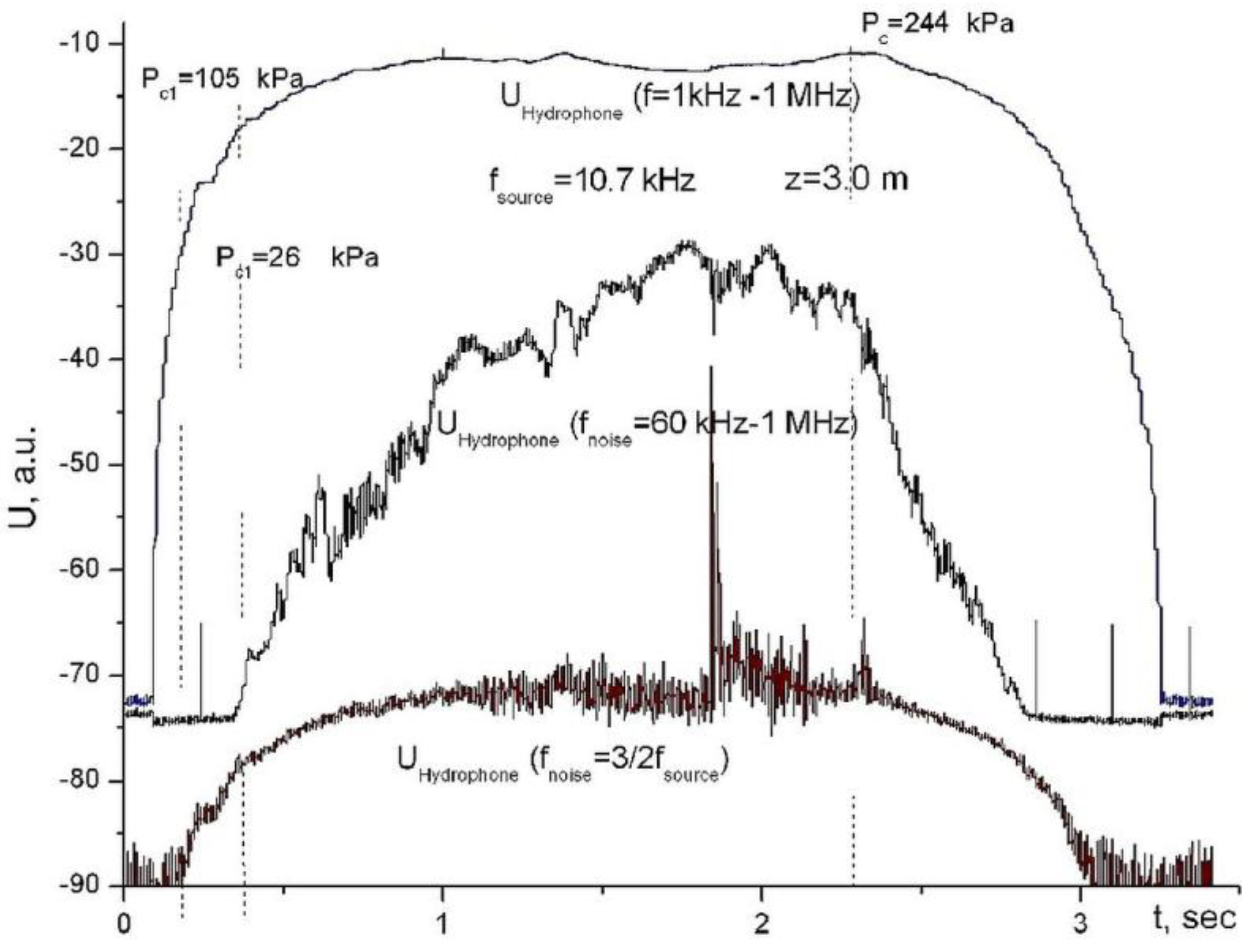

Figure 11 shows the time dependences of various spectral components of acoustic noise: a subharmonic signal

at a frequency of

, total harmonics

in the frequency range from 1 kHz to 1 MHz, higher harmonics

, starting from the 6th harmonic 64.2 kHz. The depth at which the model of the cavitation strength meter was located was 3 m. It can be seen that the first threshold

kPa corresponds to the beginning of cavitation, and the second threshold

kPa, located in the asymptotic section

, corresponds to the beginning of violent cavitation.

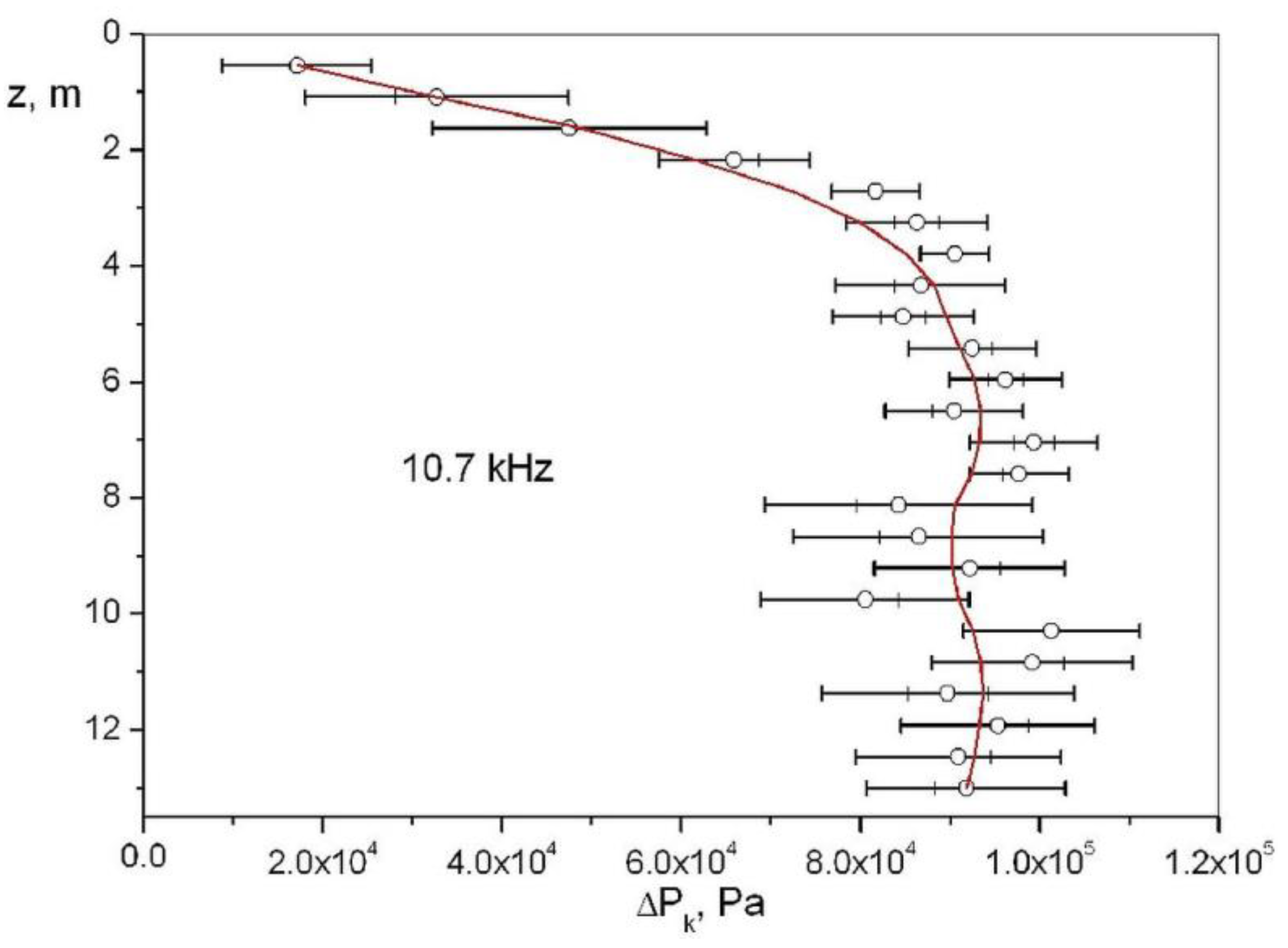

Experimental studies of the cavitation strength of seawater were carried out in the autumn period in the Vityaz Bay of Peter the Great of the Sea of Japan.

Figure 12 shows the temperature and salinity distributions of seawater depending on the depth. It can be seen that there is a clearly defined upper mixed layer with quasi-homogeneous temperature and salinity, extending to a depth of about 6-8 meters. Below is a pronounced jump layer characterized by high vertical gradients of hydrophysical parameters of seawater.

Figure 13 shows the cavitation strength of seawater as a function of depth, measured in a series of experiments in the same place in Vityaz Bay, the hydrology of which corresponds to

Figure 12. The voltage continuously changed during probing. So measurements of each point of cavitation strength were carried out in a certain depth range of about 0.5 meters. Individual points in

Figure 13 correspond to the specified depth intervals. Data on the first cavitation threshold

were taken as a cavitation criterion . The measurement errors of cavitation strength are indicated on the graph and partly reflect the statistical nature of acoustic cavitation.

Figure 13 shows that the cavitation strength of seawater significantly depends on the depth in the subsurface layer up to 6 meters thick, and then the dependence on depth is weakly expressed. We associate the obtained results on the decrease in the cavitation strength of seawater in the near-surface layer with the presence of gas bubbles that are always present in this layer. Referring to the theoretical results for the cavitation strength of water with bubbles shown in

Figure 1, it can be seen that the experimentally detected decrease to 20 kPa of the cavitation strength of water in the immediate vicinity of the sea surface, which is shown in

Figure 13, can be explained by the presence of air bubbles with a total volume concentration of 1.2*10

-4.

2.8. Cavitation in liquid caused by optical breakdown

Experimental complex

Experimental studies of aqueous solutions were carried out on the basis of complexes including Nd:YAG "Brilliant", "Brio" and "Ultra" lasers with the following radiation parameters: wavelength 532 nm, pulse duration 10 ns, pulse energy up to 180 mJ, varying in the modulated Q-factor mode, pulse repetition rate is 1-15 Hz [

51,

52,

53,

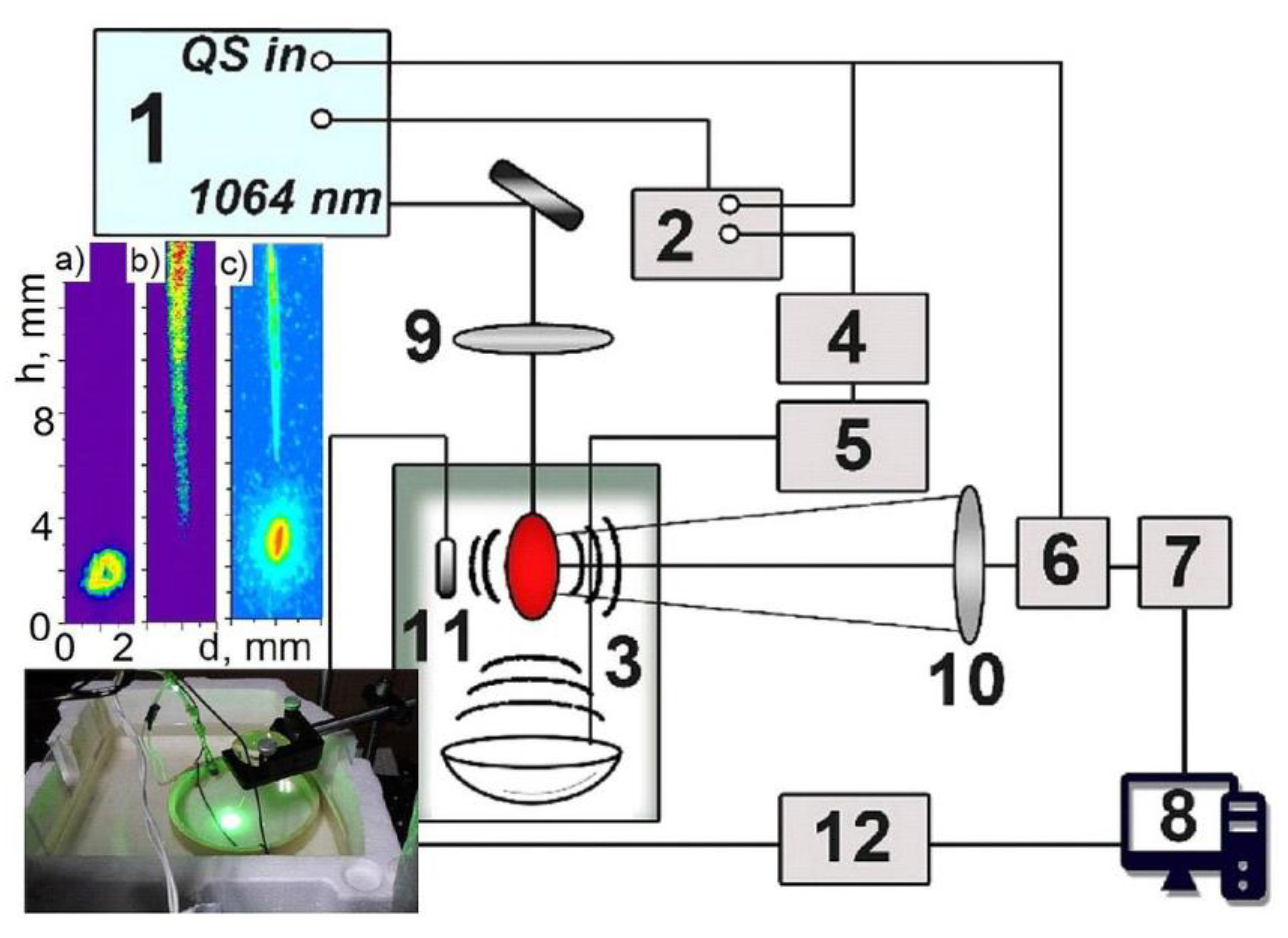

54]. A typical scheme of the experimental setup is shown in

Figure 14. The laser provided a pulsed mode of plasma generation on the surface of aqueous solutions. The power density of the laser radiation was further increased due to the sharp focusing of the radiation in the desired location (in the liquid, on the surface or near the surface of the liquid) using lenses with different focal lengths F = 40 mm, 75 mm and 125 mm. Optical breakdown was recorded using an optical multichannel spectrum analyzer Flame Vision PRO System, with a time resolution of 3 ns, i.e. An optical breakdown occurred in the focusing area, the radiation of which was directed by means of a quartz lens or a light guide to the entrance slit of the Spectra Pro spectrograph coupled with a strobed CCD camera. This scheme provided a delay in recording the pulse relative to the beginning of the optical breakdown and varying the exposure time of the signal from 10 ns to 50 microseconds from the beginning of the laser breakdown. Taking into account the variation of delays and exposures, the necessary optimal conditions for recording optical breakdown inside the liquid were found.

Methods of conducting experiments

The optical part of the experiments is traditional and were carried out according to the following scheme [

51,

52,

53]. Laser radiation (1) was focused into a liquid using a rotary mirror and a lens (9). The plasma radiation of the optical breakdown was projected by a lens (10) onto the input slit of a monochromator (7) coupled to a CCD camera. The control was carried out by a computer (8). Various types of breakdown in water were achieved by focusing laser radiation using various lenses. The breakdown occurred either in the depth of the water, or in the near-surface layers, or in a combination of these two types. Depending on the types of breakdown, different resolution of spectral lines is realized.

To analyze the breakdown dynamics and study the parameters of the acoustic wave initiated by optical breakdown, a Brüel&Kjær type 8103 hydrophone was used as a broadband acoustic receiver, the calibration of which at high frequencies was expanded to 800 kHz. Acoustic information was digitized and recorded using a multi–channel I/O board from L–Card with a maximum digitization frequency of ~ 5 MHz. To control ultrasound, an arbitrary pulse generator GSPF 053, a power amplifier and a resonant cylindrical radiator [

54,

55,

56,

57] were used, inside which a liquid breakdown occurred in a converging ultrasound field.

2.9. Acoustic Emission Caused by Exposure to Laser Radiation

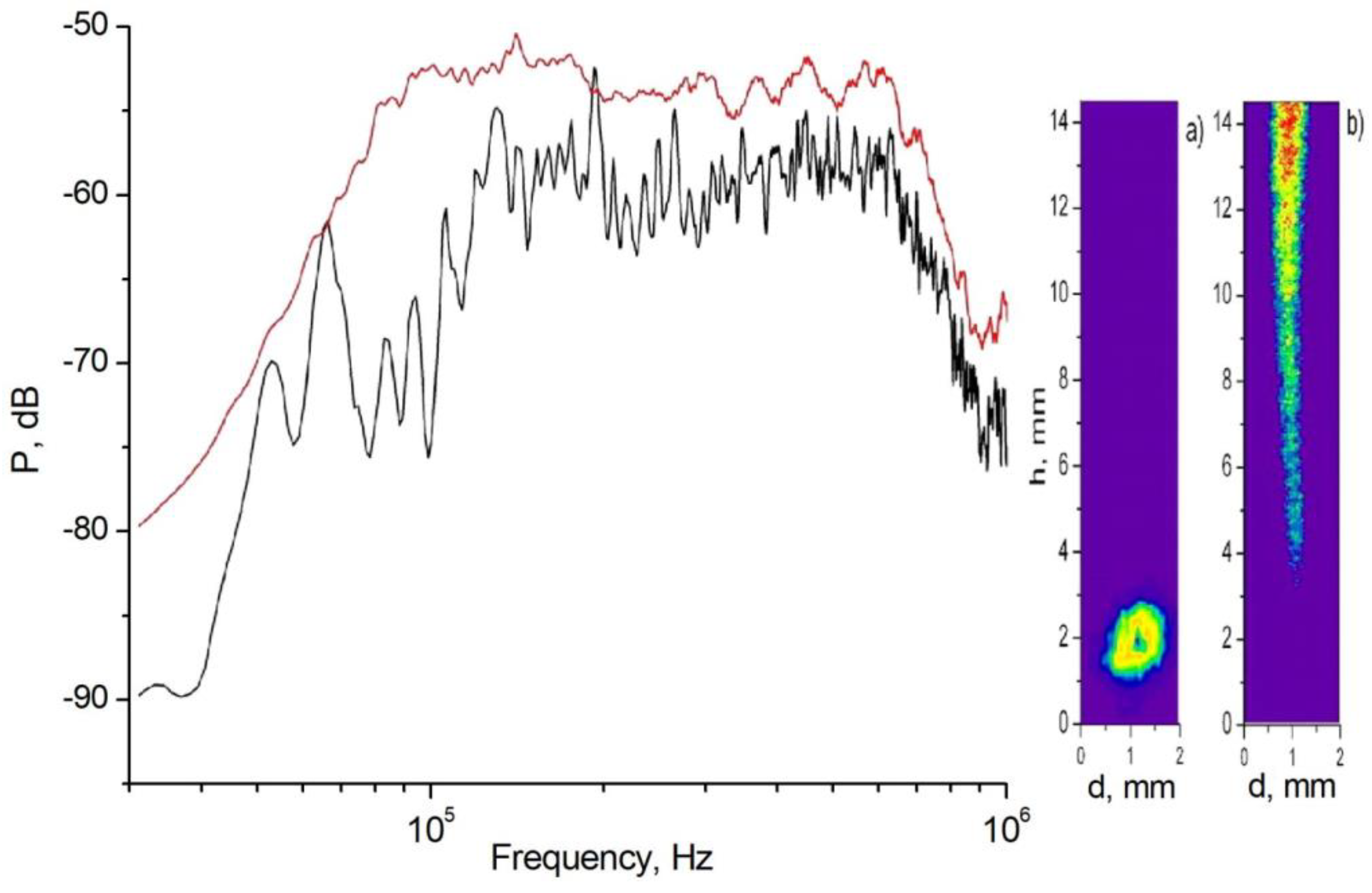

Experimental data on the spectral density of acoustic emission were obtained under various modes of breakdown in water: for surface breakdown, for breakdown in the water column and for mixed breakdown. Different modes of breakdown in water were implemented with different focusing of laser radiation by lenses. As a result, the breakdown occurred either in the water column or in the near-surface layers of water, or a mixed breakdown was observed, which is a combination of the above types of breakdown. As a result, it turned out that the acoustic emission and the values of the spectral densities of sound differ significantly depending on the nature of the optical breakdown, which can be seen from

Figure 15.

Simultaneously with the optical breakdown of a liquid in a liquid, a disturbed density region is formed in the vicinity of the breakdown zone, which leads to the formation of an acoustic pulse.

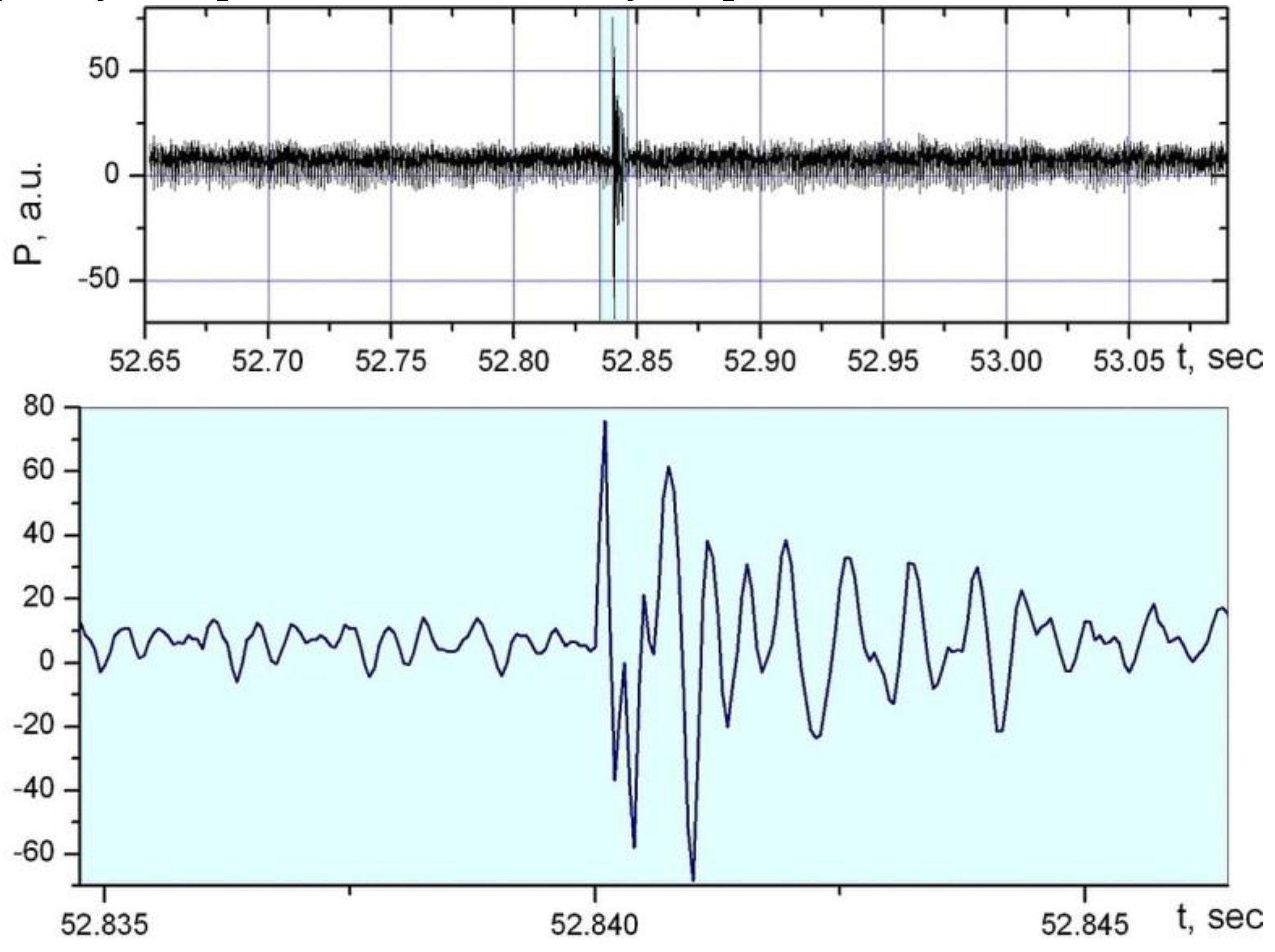

Figure 16 shows a recording of a typical acoustic pulse accompanying a liquid breakdown [

55,

56]. The distance from the breakdown area to the hydrophone was about 10 cm.

Figure 16 shows that a relatively low-frequency component reaches the hydrophone.

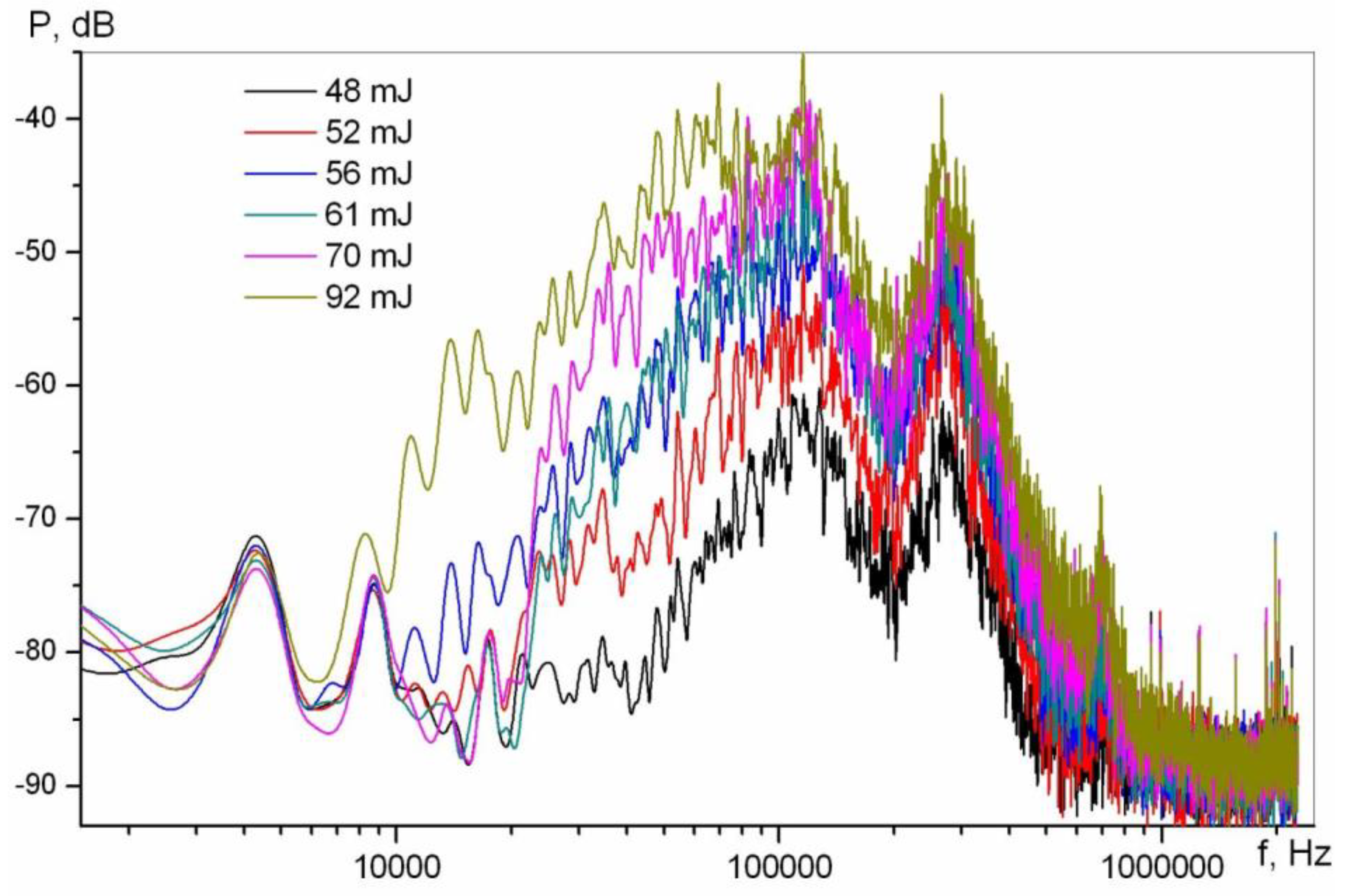

The measurement of acoustic emission was used to study the dependence of the efficiency of sound generation on the energy of a laser pulse and its focusing in a liquid.

Figure 17 shows the spectral characteristics of an acoustic wave generated in a liquid by an optical breakdown depending on the energy of the laser pulse. It can be seen from

Figure 17 that shifts of the low-frequency maximum to the region of lower frequencies are observed with an increase in the pulse energy. The high-frequency spectral maximum, which is not displaced at all laser pulse energies, is probably related to the natural resonance of the hydrophone at a frequency of ~ 300 kHz.

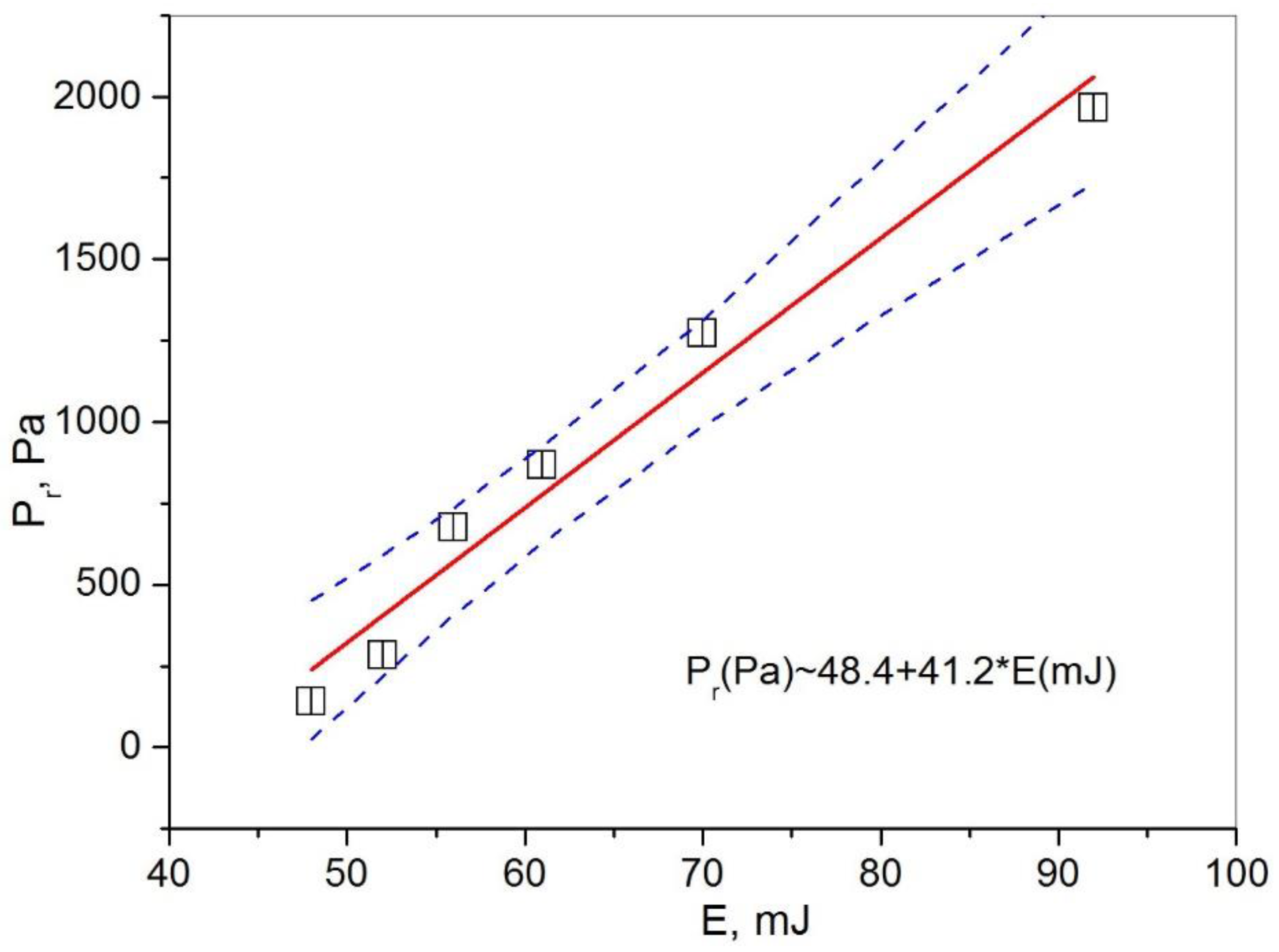

Figure 18 shows the dependence of the sound pressure

P on the leading edge of the acoustic pulse on the energy

E. Let's analyze the dependence of acoustic emission on the dynamics of bubbles. The method of analysis is as follows. The total energy of the acoustic pulse

is calculated as:

where

, the angle brackets for the function

mean averaging over the duration of the pulse

of the type

. At distances

r greater than the radius of the bubble

R,

, where acoustic emission is registered, the wave front in the registration area can be considered flat, from where we have a relationship between the pressure and the velocity of particles in the wave in the form [

3]

, where

is the density,

is the speed of sound in the medium. As a result , we have the total energy of the acoustic pulse

in the form [

55,

56]

Along with the obtained estimates of the total energy of the emitted acoustic pulse, it is of interest to try to solve the inverse problem – to restore the dynamics of the bubble according to acoustic emission data. The theoretical basis is a formula for the distribution of pressure in the radiated wave from a spherical bubble as a source of monopole radiation, which can be written in the form [

3]

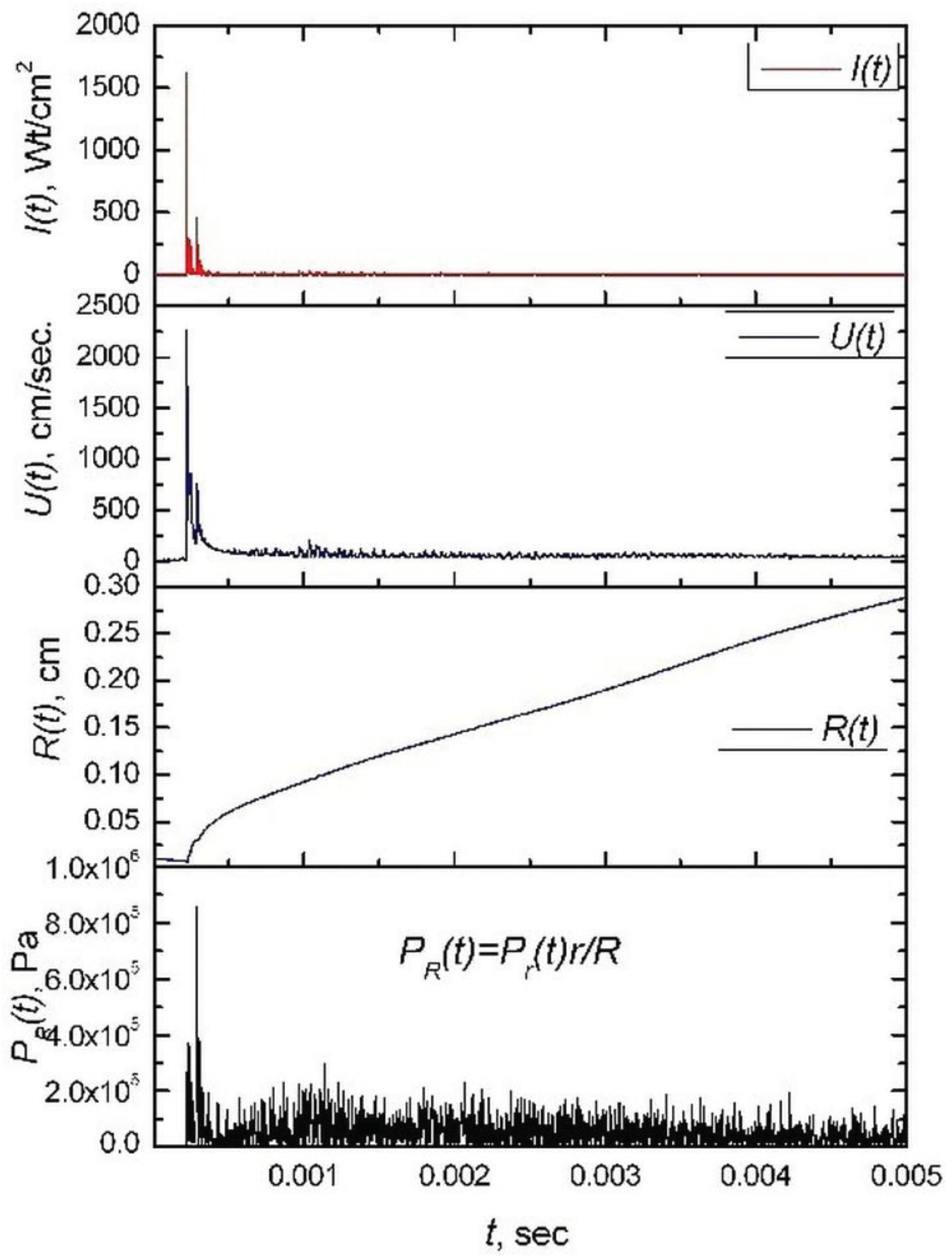

where

. Solving a nonlinear differential equation with respect to the function R(t), while considering the function P(t) known on the basis of experimental data in the received acoustic pulse, it is possible to calculate the function R(t), the velocity of the bubble wall U(t) and the intensity in the acoustic wave

Figure 19 shows these dependencies, which show that the acoustic data can reproduce the function

R(t), which is consistent with the characteristic dependencies

R(t) obtained from direct measurements of optical breakdown images at the late stages of its evolution.