1. Introduction

The manufacturing sector is among the industries with a high risk coefficient. The absence or reluctance to use appropriate safety gear (such as gloves) leaves workers unprotected in harsh working environments, posing safety risks and jeopardizing their physical well-being.

Reasons for workers not using gloves include.Inadequate awareness of safety hazards that can cause indirect injuries. For instance, cement industry workers in the Niger Delta work in electrified settings without wearing insulating gloves[

1].Lack of relevant skill training. For example, wood factory workers in Calabar, southern Nigeria, believe PPE (gloves and safety boots) is beneficial, yet all respondents stated they lacked training on the proper use of PPE[

2].Perception that gloves hinder operations. A 46-year-old woman, having worked in a box factory for 18 years, primarily applied pressure and friction with her fingertips. She felt gloves interfered with dexterous tasks, thus rarely wore them. Consequently, she developed eczema and fissured dermatitis on her fingers[

3].

Wearing gloves can effectively protect hands from environments prone to causing injury. Relying on manual checks for glove use undoubtedly wastes significant human resources. Hence, object detection algorithms present an optimal choice for detecting glove usage.

Current object detection algorithms can be broadly categorized into two main directions: two-stage detection and one-stage detection. Two-stage detectors include the likes of Faster R-CNN[

4], R-FCN[

5], and Mask R-CNN[

6]. These algorithms generate a series of region proposals in images and subsequently classify and regress these proposals. Due to its bifurcated process, it’s termed two-stage detection.

One-stage detectors primarily include YOLO[7-10], SSD[

11], CornerNet[

12], and M2Det[

13] among others. Instead of generating proposal boxes, these algorithms directly predict object categories and locations in a single step. One-stage detection algorithms are typically faster than two-stage detectors due to their singular step execution, though they might compromise on accuracy in some cases. Therefore, one-stage detection algorithms are better suited for tasks demanding high real-time performance and constrained computational resources.

With the rapid advancements in object detection algorithms, especially the immense success of the YOLO series in object detection, more researchers are venturing to apply object detection algorithms in real-world scenarios. For instance, Arunabha et al.[

14] proposed an enhanced YOLOv5 model based on DenseNet and the Swin-Transformer detection head, achieving commendable results in road damage detection. Jiang S, Zhou X et al.[

15] introduced the lightweight DWSC-YOLO model, incorporating DWS convolution and Efficient attention mechanism, reducing the model size making it apt for deployment on SAR radar devices. Sun C, Zhang S et al.[

16] presented the MCA-YOLOV5-Light model for safety helmet detection, embedding the MCA module and implementing sparse training.

To avoid disturbing workers operating machinery, cameras are placed at a considerable distance from them. As a result, gloves occupy a small fraction of the image, with the shooting environment being intricate, leading to gloves being easily obscured by the cluttered background. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f model. The main contributions of this research are as follows:

We have devised a novel feature fusion pyramid, christened AFPN-C2f, which supplants the pre-existing PAFPN network within YOLOv8. This modification is engineered to foster the fusion of feature vectors between non-adjacent layers, mitigating the semantic discrepancies between low-level and high-level features. Moreover, we delve into the implications of varying C2f concatenation counts and other feature extraction modules on the model’s performance.

We introduced a superficial feature layer enriched with detailed image feature information, enhancing the model’s perception of surface information.

We made a dataset suitable for factory glove detection. This dataset, collected from the production workshop of Zhengxi Hydraulic Company, comprises 2,695 annotated high-resolution images capturing workers either wearing gloves or working barehanded with machinery.

2. YOLOv8 Algorithm

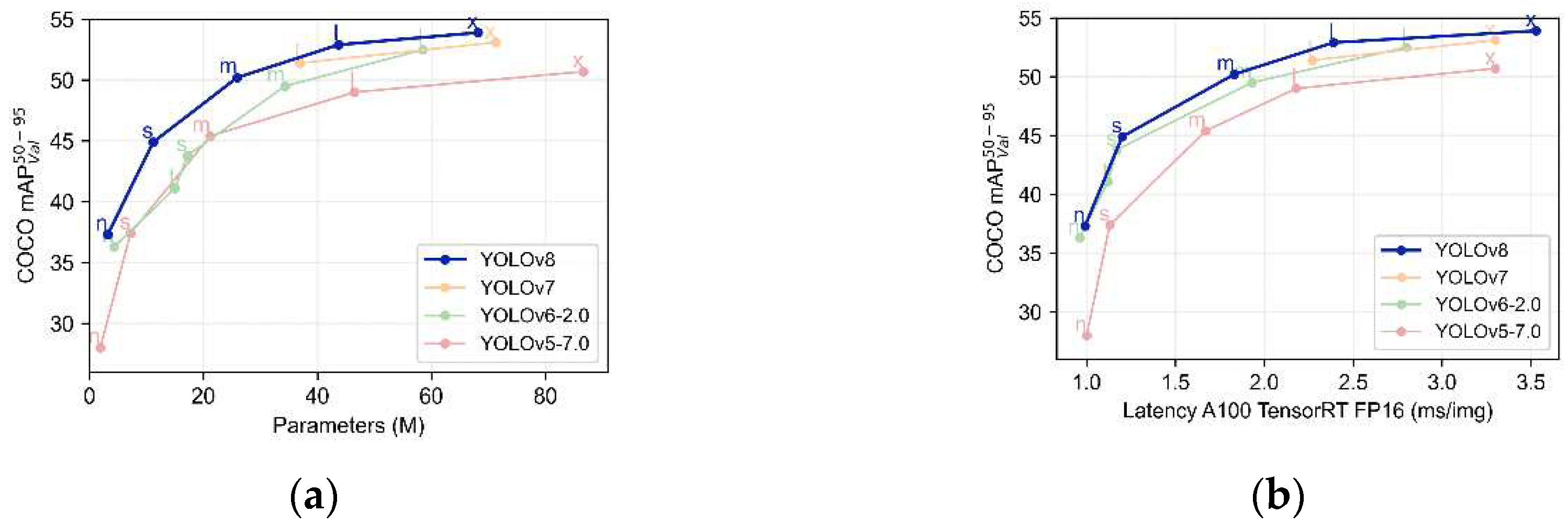

Figure 1 depicts the relationship between the parameter count, processing time per image, and

for four YOLO algorithms: YOLOv5, YOLO6, YOLOv7, and YOLOv8. As evident from

Figure 1, YOLOv8 surpasses other algorithms in

for equivalent parameters and time, leading us to select YOLOv8 as the foundational framework for object detection.

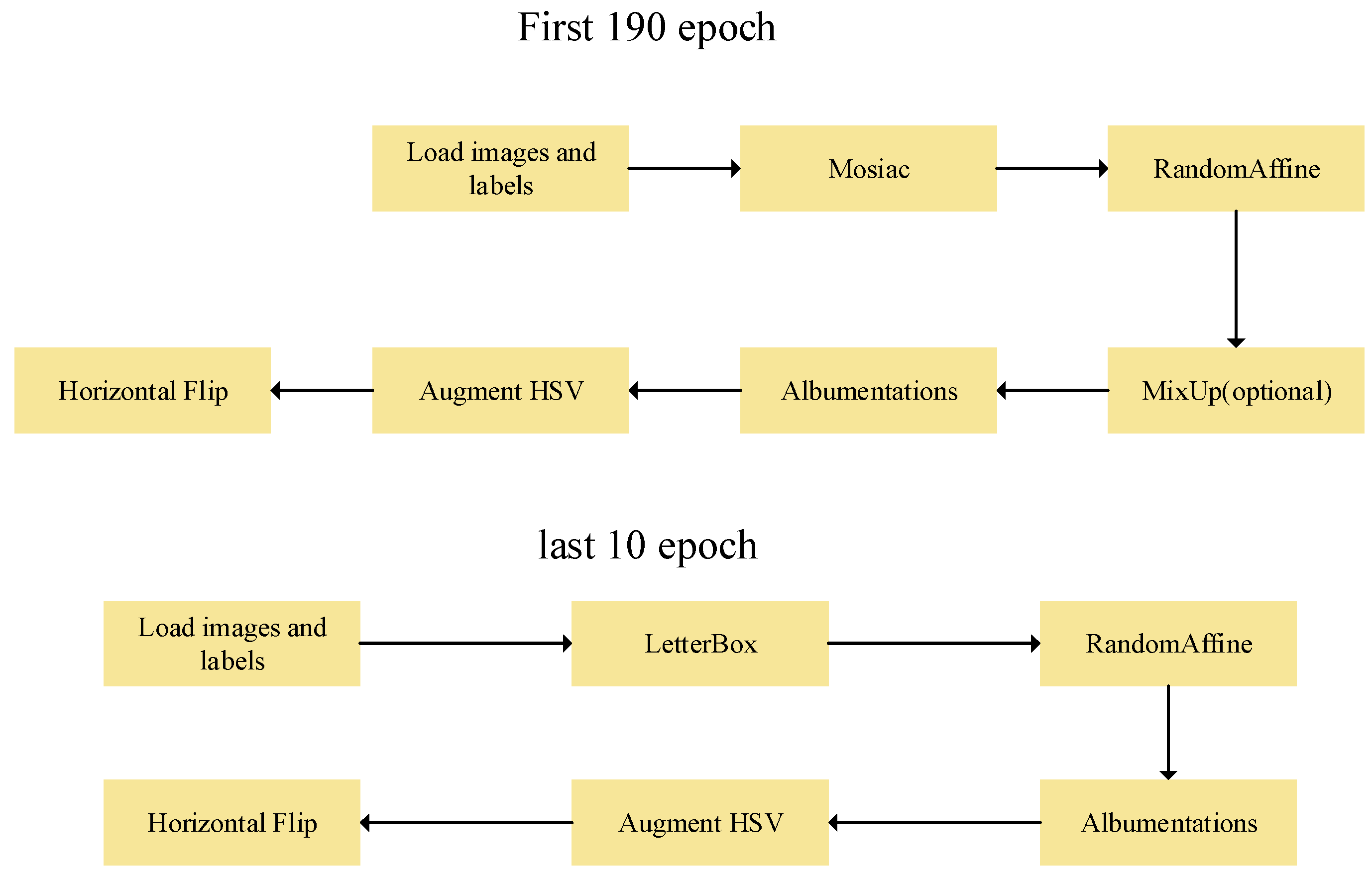

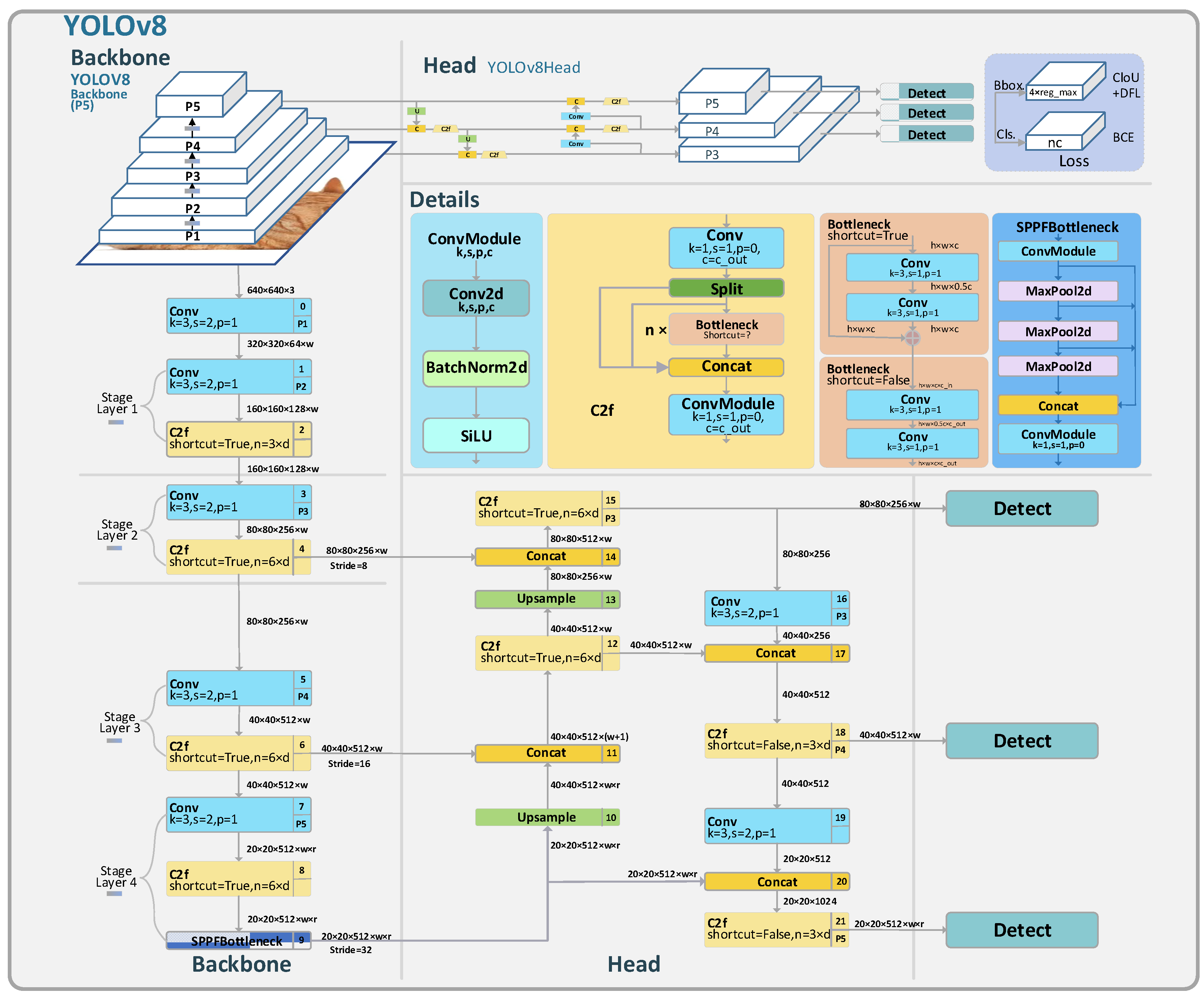

As depicted in

Figure 3, its backbone network employs the Darknet53 architecture, with the head utilizing PAFPN for feature fusion. The detection head adopts an anchor-free design. This anchor-free detection reduces the number of box predictions, thereby accelerating the speed of Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), a complex post-processing step required to filter candidate detections after inference. Regarding data augmentation, as shown in

Figure 2’s model training workflow, v8 incorporates an action to disable Mosaic during the final 10 epochs. In terms of loss computation, recognizing the exceptional nature of the dynamic allocation strategy, YOLOv8 directly employs TOOD’s TaskAlignedAssigner[

17]. As demonstrated by Equation (1),

where,

represents the predicted score corresponding to the annotated category, and

signifies the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the predicted and ground truth boxes.

where

denotes the sample label,

o[

i] is the model’s predicted probability for the sample,

t[

i] represents the actual probability of the sample, and

n stands for the total number of samples.

YOLOv8 is the latest model in the YOLO series. Compared to the widely popular YOLOv5, YOLOv8 has transitioned its first convolutional layer’s kernel from 6x6 to 3x3, replaced the C3 module with C2f. The C2f module has more skip connections and additional Split operations than the C3 module. The Neck module has been streamlined by removing two convolutional layers. The most significant change is in the Head section, transitioning from the original coupled head to a decoupled one, and the detection box has shifted from YOLOv5’s Anchor-Based to Anchor-Free.

3. Improved Algorithm: YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f

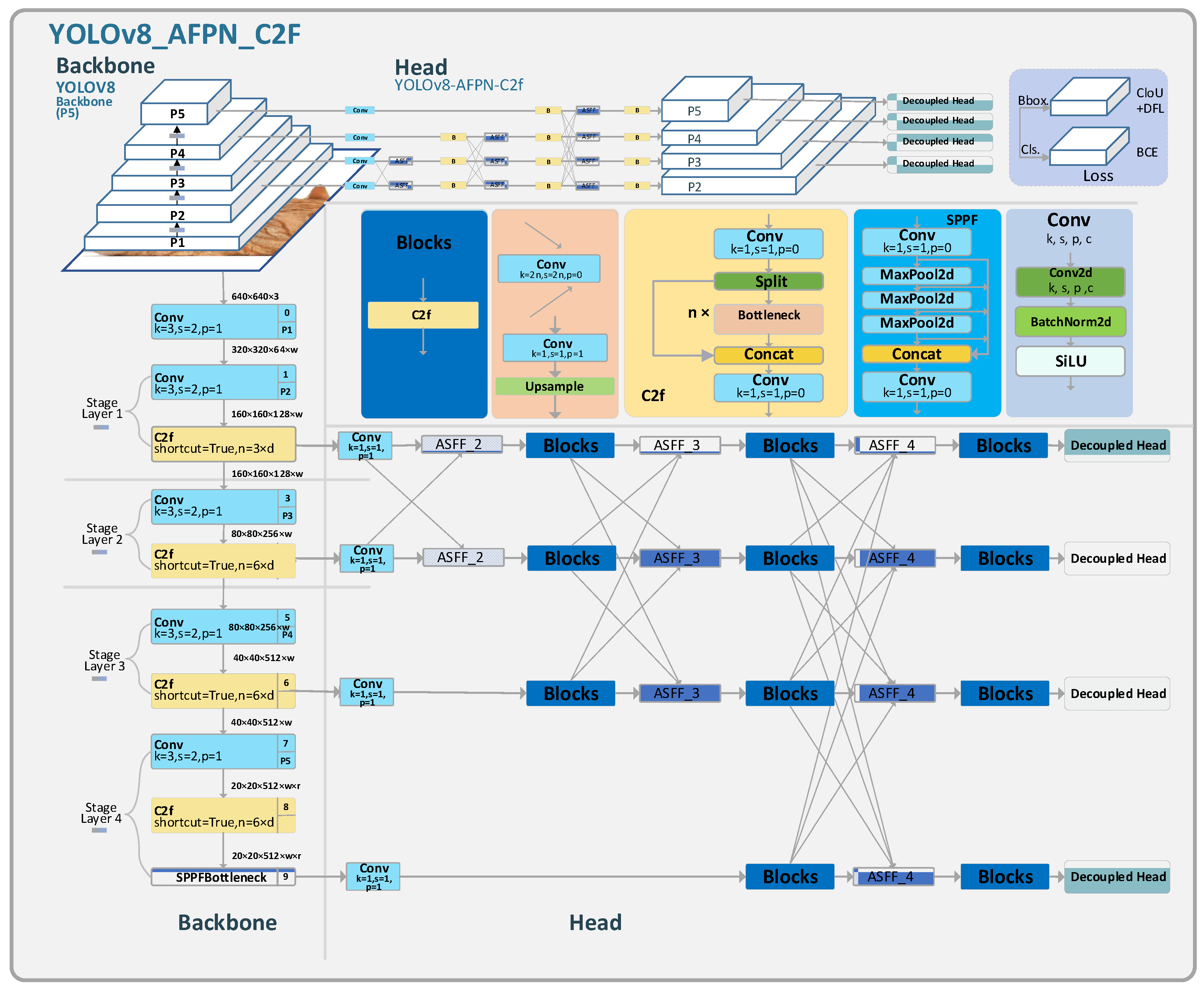

Compared to YOLOv8, our improved algorithm, named YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f, possesses a more robust feature perception capability. It retains more superficial features and adds channels for feature information propagation, thereby improving accuracy. Additionally, it reduces the number of parameters, elevates FPS (frames per second), and decreases the demand for computational resources.

YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f primarily made enhancements in the head and detection aspects. In the head section, this study draws inspiration from AFPN and, combined with YOLOv8’s C2f module, proposes a new FPN design. In the backbone network, an additional feature layer is introduced, along with a new detection head.

Figure 4 illustrates the architectural design of the YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f model.

3.1. Feature Pyramid Network

Feature Pyramid Network, abbreviated as FPN, is designed to tackle the challenge of multi-scale targets in object detection. At the heart of FPN lies the idea of constructing a hierarchical feature pyramid within Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), facilitating target detection across varying scales. FPN markedly enhances performance in tasks like object detection, keypoint detection, and semantic segmentation. It has been widely integrated into a myriad of networks such as RetinaNet[

18], Mask R-CNN[

19], Cascade R-CNN[

20], EfficientDet[

21], and Panet[

22].

High-level features can extract extensive characteristics from an image. However, they tend to overlook intricate details, thereby diminishing the model’s sensitivity to smaller targets. This often leads to suboptimal performance on datasets dominated by small objects. In contrast, low-level features focus on the rich, superficial details of an image, enabling the model to perceive localized nuances. Yet, these low-level features lack a holistic view. Within the feature pyramid, high-level features guide the intermediate ones, and the intermediate features, in turn, guide the low-level features. This cascading approach ensures the model is equipped with both a global perspective and localized focus, enhancing its predictive sensitivity. The FPN employs a bottom-up approach, transmitting high-level features to the lower layers, facilitating the fusion of features across different levels. However, during this transmission, high-level features remain uninfluenced by the low-level ones, posing a potential risk of information loss.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.2. Improved FPN: AFPN-M-C2f

This study designs a progressive feature fusion pyramid network, named AFPN-M-C2f. This network can significantly reduce the number of parameter and enhance the feature information extraction ability. By minimizing ambiguities and conflicting information between features, it ultimately boosts the model’s prediction accuracy.

This network integrates features from each level, with superficial features being fused with deeper ones in each iteration. Compared to the original AFPN[

23], the AFPN-M-C2f adds an additional superficial feature layer and replaces the 3×3 convolution kernel in the Blocks feature extraction module with C2f.

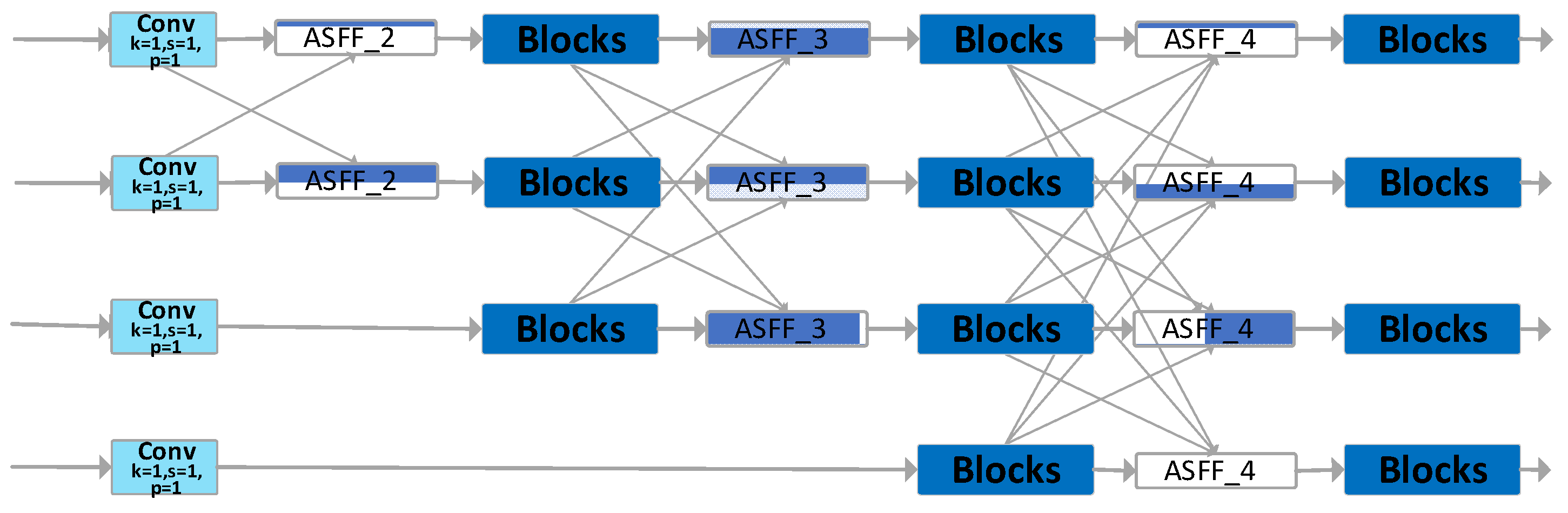

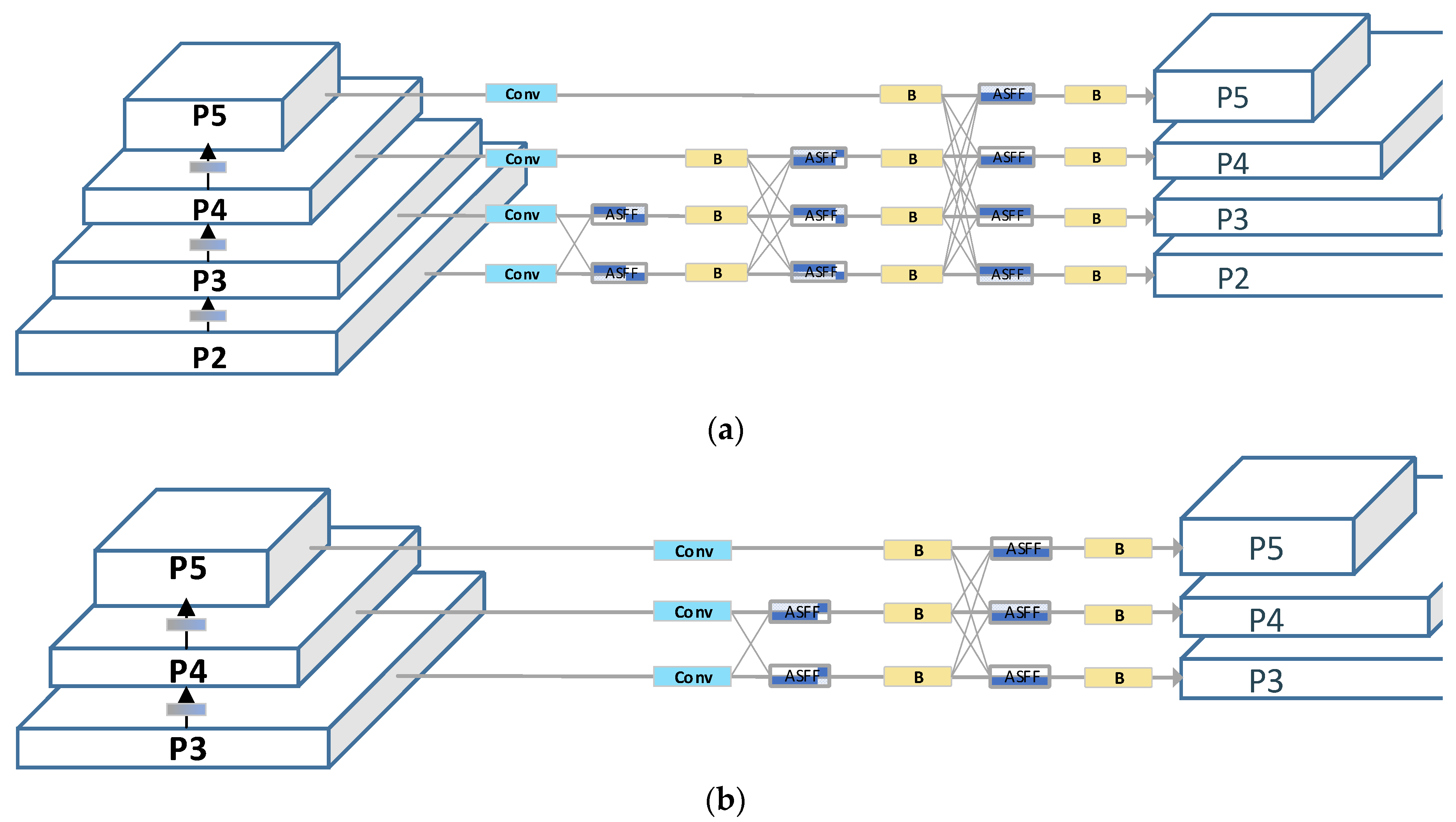

As depicted in

Figure 5, AFPN extracts features layer by layer. Initially, during the primary stage, it integrates two feature vectors. In the intermediate phase, three feature vectors are merged, and in the final stage, four feature vectors are synergized, achieving a progressive fusion of features from low to high levels. Specifically, the network begins by integrating surface features, then delves into deeper features, and ultimately fuses abstract layer features. During this fusion process, arrows pointing diagonally upwards signify upsampling, while those pointing diagonally downwards indicate downsampling. The ASFF module adaptively fuses features from distinct layers, and the Blocks module is entrusted with feature extraction.

This paper employs AFPN-M-C2f to enhance the neck of YOLOv8, offering two notable advantages to the revamped YOLOv8:

It facilitates the fusion of features between non-adjacent layers, preventing the loss or degradation of features during their transmission and interaction.

It incorporates an adaptive spatial fusion operation, suppressing conflicting information between different feature layers and preserving only the useful features for fusion.

3.2.1. Feature Vector Adjustment Model

In the feature fusion process, feature vectors of different dimensions cannot be directly integrated; hence, it’s imperative to adjust the dimensions of these feature vectors. AFPN employs 1×1 convolution and bilinear interpolation methods to upsample the features. As illustrated in

Figure 6, a convolutional kernel of size n×n with a stride of n is used for downsampling. The size of n depends on the downsampling rate. For instance, a 2×2 convolution with a stride of 2 is used for 2x downsampling, a 4×4 convolution with a stride of 4 is utilized for 4x downsampling, and an 8×8 convolution with a stride of 8 is adopted for 8x downsampling.

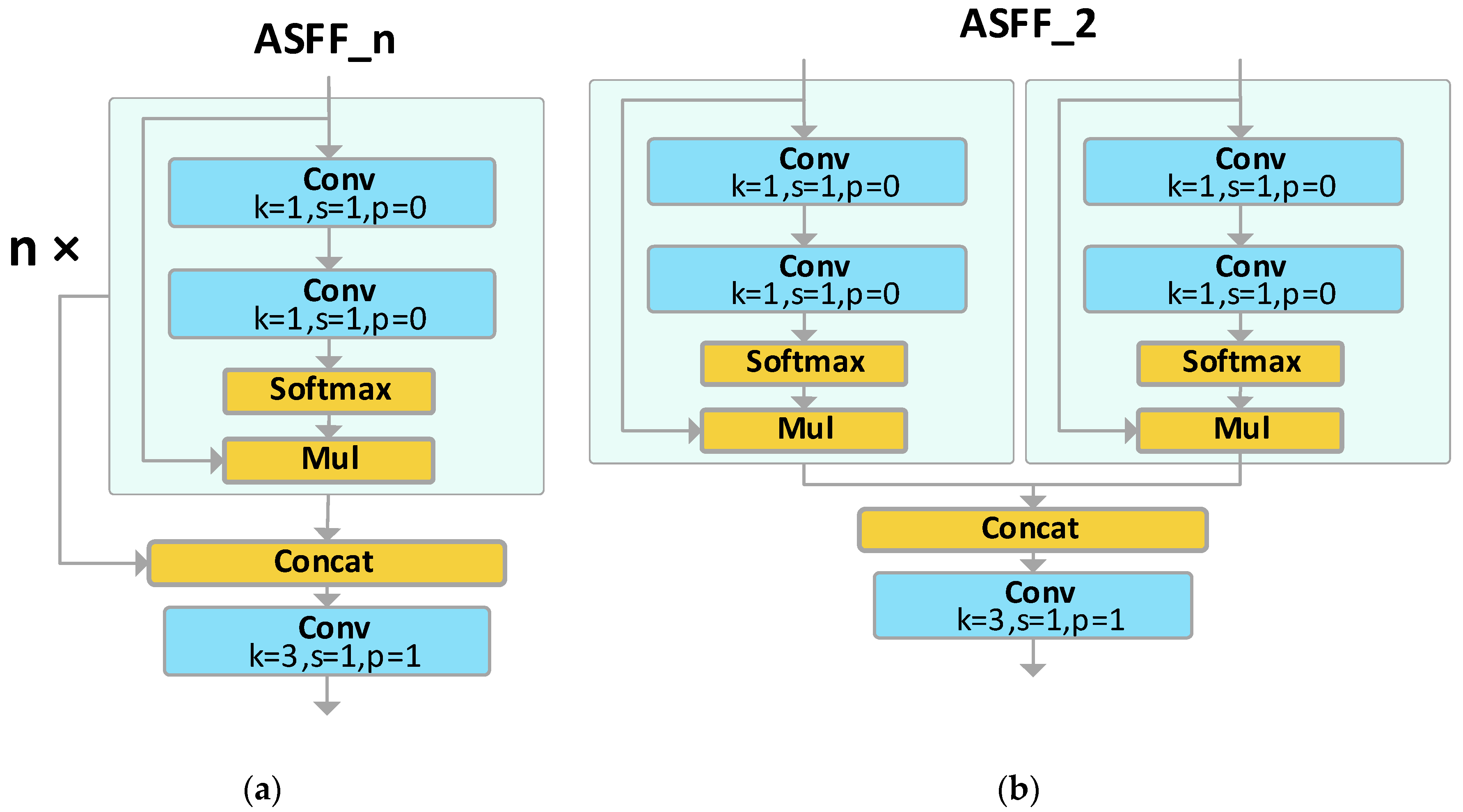

3.2.2. Adaptively Spatial Feature Fusion

In AFPN, a singular feature needs to integrate multiple features from other layers. To seamlessly integrate multi-level feature information, this paper draws inspiration from the Adaptive Spatial Fusion Module [

24], leading to the creation of the ASFF_n module. As shown as

Figure 7(a), ’n’ denotes the number of channels for feature fusion, with ’n’ ASFF modules allocating the feature information of ’n’ channels via weights. Taking ASFF_2 as an example, as depicted in

Figure 7(b), the features from the two input ends are weighted through two 1×1 convolutional kernels. These two weights are then combined, and finally, a 3×3 convolutional kernel adjusts the size of the feature map to output the integrated feature.

To illustrate with the ASFF_4 module as an example, the process of ASFF fusing four-channel features is represented as per Equation (3),

where

denotes the feature vector fused by ASFF_4. The term

refers to the feature vector on the feature transferred from the nth layer to the lth layer. The weights

represent the adaptively learned weights for the four distinct feature vectors directed to the lth layer.

The summation of weights for each feature vector being equal to 1 ensures the normalization of the feature vectors, thus preventing any unexpected amplification or reduction of the vectors.

The Adaptive Spatial Fusion Module adeptly amalgamates features from multiple layers, diminishing semantic discrepancies and ambiguities between them, while retaining pertinent feature information.

3.2.3. Enhancing the Feature Fusion Module of AFPN

In the realm of computer vision research, neural networks predominantly rely on convolutional kernels for feature extraction. These kernels are characterized by spatial invariance and channel specificity[

25]. While spatial invariance ensures parameter efficiency across various spatial transformations, enlarging the kernel size leads to a substantial increase in parameter count. Stacking multiple kernels can circumvent this surge in parameters. However, such a practice also compromises computational efficiency.

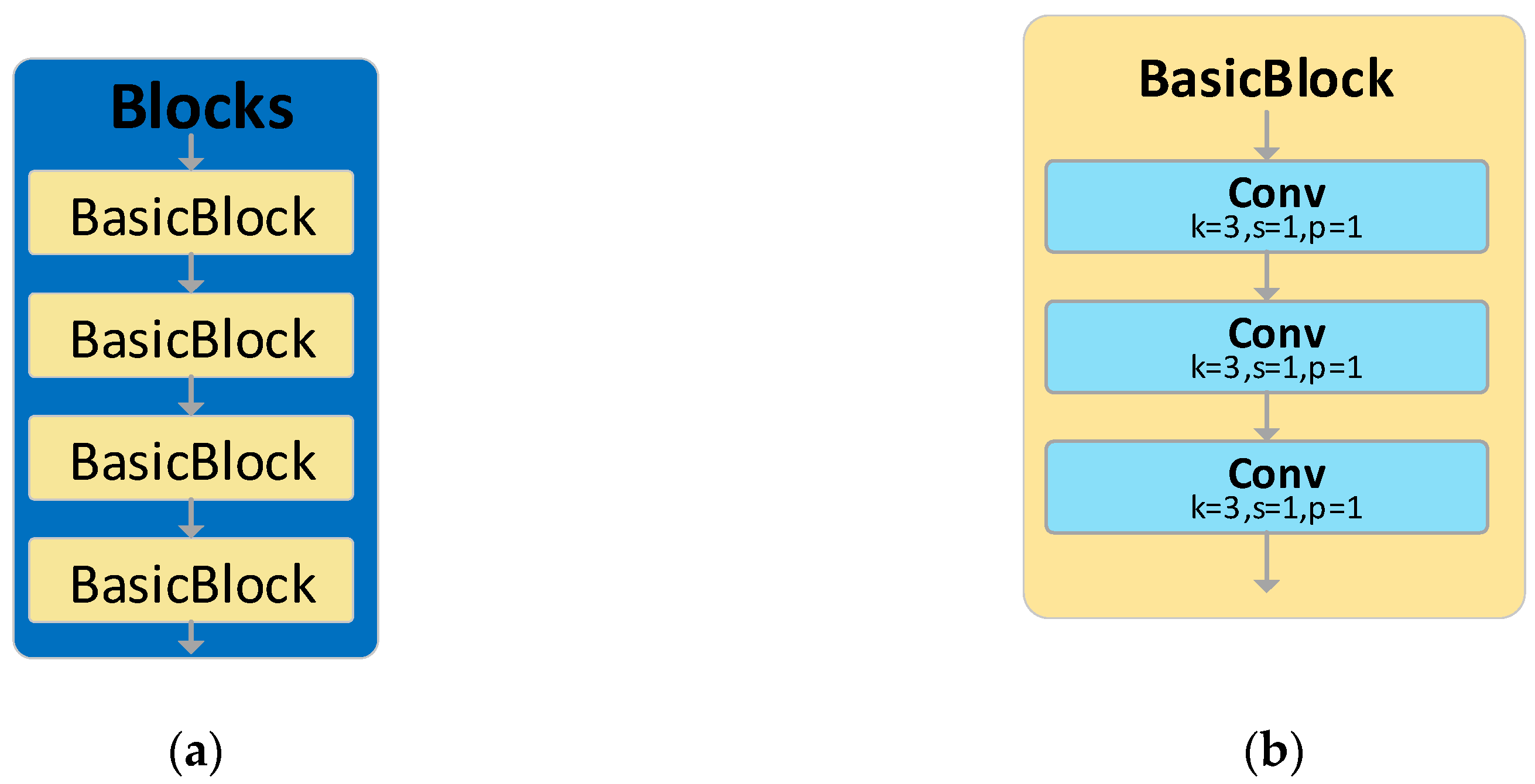

Within the AFPN framework, the Blocks module is employed for feature extraction. As depicted in

Figure 8, the original Blocks is comprised of four BasicBlocks, each of which contains three 3×3 convolutional kernels, culminating in a total of 12 kernels for a single Blocks module. The abundance of kernels in the Blocks module results in an immense parameter count, consequently diminishing the effectiveness of feature extraction.

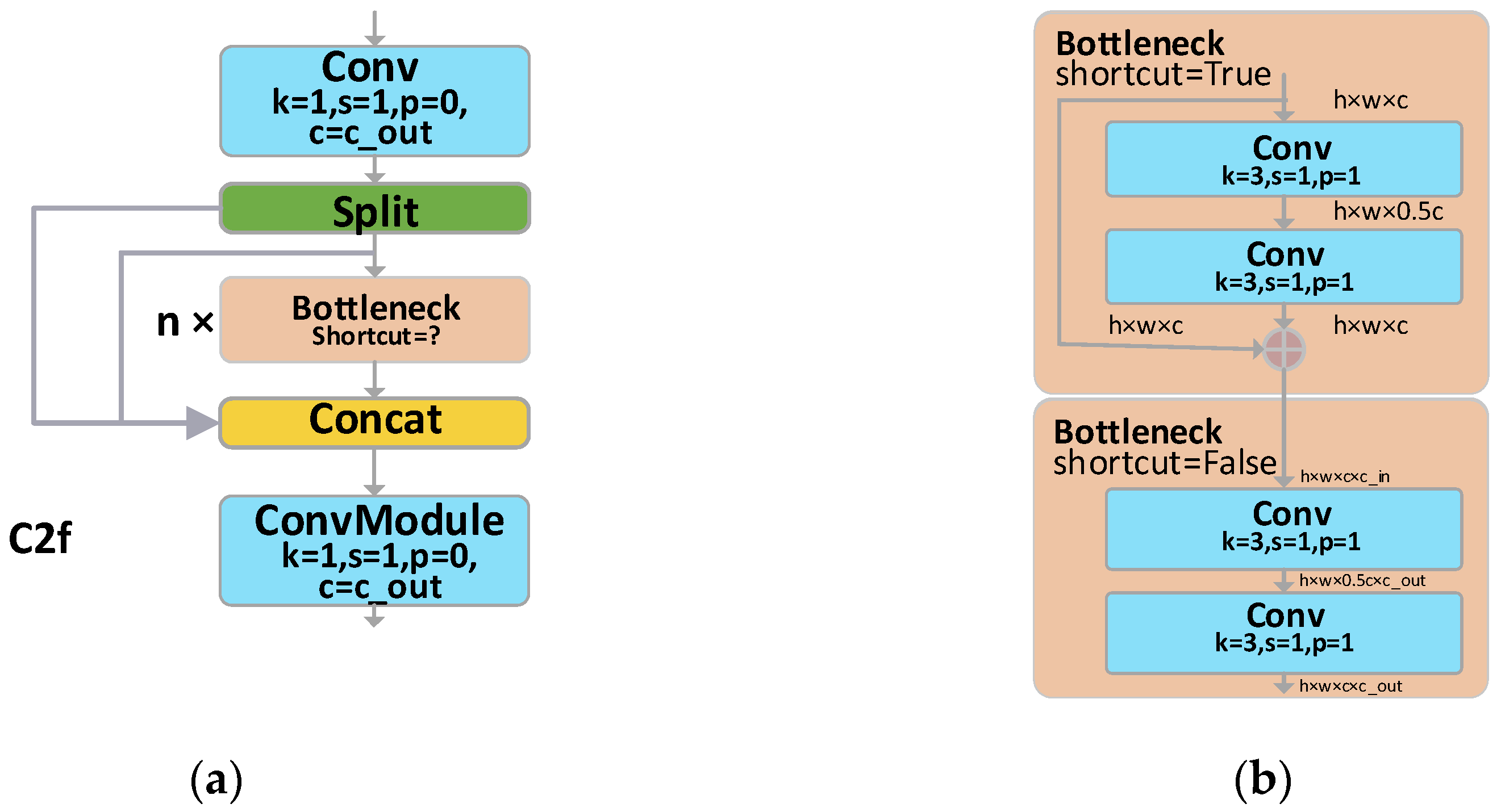

In the YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f architecture, we have incorporated a C2f module, supplanting the traditional Blocks module. This C2f module, distinct to YOLOv8, is pivotal in extracting features, thereby enhancing the efficacy of object detection. As delineated in

Figure 9, the Bottleneck’s 3×3 convolution kernel within the C2f is entrusted with the task of harvesting feature data. The input feature information, traversing through a chain of sequentially linked Bottlenecks, transitions progressively from rudimentary feature maps to their advanced counterparts. While the elementary feature maps are replete with intricate details, they are devoid of overarching context. In contrast, the advanced feature maps imbue rich contextual cues but might sacrifice some minutiae. By establishing residual linkages between these diverse feature levels, the C2f module adeptly harnesses both the granular details and the encompassing context across various scales, thus amplifying the accuracy and robustness of object detection. Consequently, we employ the C2f module as a substitute for the Blocks module in AFPN.

3.3. More Feature Layer

FPN employs multi-scale feature maps to capture feature information across different resolutions. The conventional FPN extracts only the {P3, P4, P5} feature layers, with the advantage of having fewer parameters. Its shortcoming, however, is the limited perception of small objects, rendering it inadequate for detecting small items such as gloves; furthermore, it lacks sufficient semantic information, making it challenging to capture the semantic nuances in complex backgrounds like factory workshops. Taking YOLOv8-AFPN as an example,

Figure 10(b) illustrates that the original AFPN only extracts the {P3, P4, P5} feature layers from the YOLOv8 backbone network.

This study introduces the AFPN-M network. As depicted in

Figure 10(a), the AFPN-M network extracts feature information from the {P2, P3, P4, P5} feature layers of the backbone network. Given the inclusion of additional feature layers, the network is aptly named AFPN-M.

Compared to the original AFPN network, the advantages of AFPN-M are manifold:

The inclusion of the P2 feature layer, enriched with shallow feature information, enhances the model’s perceptibility of smaller objects and facilitates the transmission of surface feature vectors.

An additional 16 feature layer transmission channels deeply integrate feature information.

The introduction of five more Blocks modules allows for multi-dimensional, in-depth feature extraction and fusion.

4. Deep Learning Object Detection Datasets.

Our research utilizes the Glove dataset, gathered from the manufacturing workshop of the Zexi Hydraulic Company. We employed the Labelimg software for annotation. We annotated 2,695 images that depict workers either wearing gloves or working barehanded during tasks such as equipment calibration, part machining on lathes, milling machines, and drilling machines(as shown in

Figure 11). Within the Glove dataset, each instance is delineated by a rectangle and belongs to one of the five glove categories: Bare Hand, White Glove, Canvas Glove, or Black Glove. This dataset boasts the following advantages:

The content collected closely mirrors the authentic working conditions of the workers, as we ventured directly into the Zexi Hydraulic Company’s workshop to capture the tasks performed by the staff.

Compared to other similar public datasets, ours boasts a much larger quantity, featuring several thousand images rather than merely a few hundred.

Our images are of pristine clarity with a high resolution of 3840×2160 pixels.

5. Training methodology and evaluation metrics.

5.1. Experimentation and parameter configuration.

Our experimental settings can be found in

Table 1. For model training, we employed a CPU of AMD EPYC 7T83 64-Core Processor and a GPU of RTX4090. The software environment includes CUDA version 11.8, Python 3.8, and Pytorch version 2.0.0.

In our model training, specific parameters and hyperparameters were adopted to ensure optimal performance. As shown in

Table 2, we opted for an image size of 640 x 640 for training, with the number of iterations set at 200. Given computational efficiency and model convergence rate, our batch size was fixed at 64. To bolster the model’s generalization capability, we employed the Mosaic data augmentation technique.

In terms of hyperparameters, as depicted in

Table 3, we opted for the gradient-based SGD optimizer for model optimization. Concurrently, we set an initial learning rate of 0.01, which dwindles to 0.0001 towards the end of the training. Additionally, to ensure stability and convergence speed during model training, we established a momentum of 0.937 and a weight decay of 0.0005. The selection of these hyperparameters stems from multiple experimental results and precedents in research, ensuring our model’s commendable performance under varying conditions.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

We employ evaluation metrics such as accuracy, recall, mAP, and frame rate to comprehensively assess the model’s performance on the glove dataset. Precision (P) and recall (R) are computed using the following formulas:

where P denotes the precision of the model’s predictions, R signifies the recall of the model’s predictions, TP represents the number of samples correctly classified as positive, FP indicates the number of samples incorrectly classified as positive.

where AP denotes the area under the precision-recall curve for a specific category at different confidence thresholds. mAP stands for the mean average precision, calculated by taking the average of the AP for each category. mAP@50% refers to the mAP with an intersection over union threshold of 0.5.

where, FPS indicates the number of images the model processes per second, time refers to the duration required for the model to process a single image, measured in milliseconds.

6. Results and Analysis of the YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f Algorithm.

6.1. Comparative Analysis of Algorithmic Prediction Outcomes

To vividly illustrate the enhancements of the modified YOLOv8 algorithm, this paper showcases the glove recognition results of YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f in comparison with the original YOLOv8. As observed from

Figure 12, the YOLOv8 algorithm exhibited instances of missed detections (FN) and false positives (FP), which we have highlighted with blue circles in the figure. For instance, YOLOv8 mistakenly identified a worker’s neck as ’Bare hand’ and overlooked certain gloves. However, these issues were adeptly addressed by the YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f algorithm.

6.2. Comparison Experiment

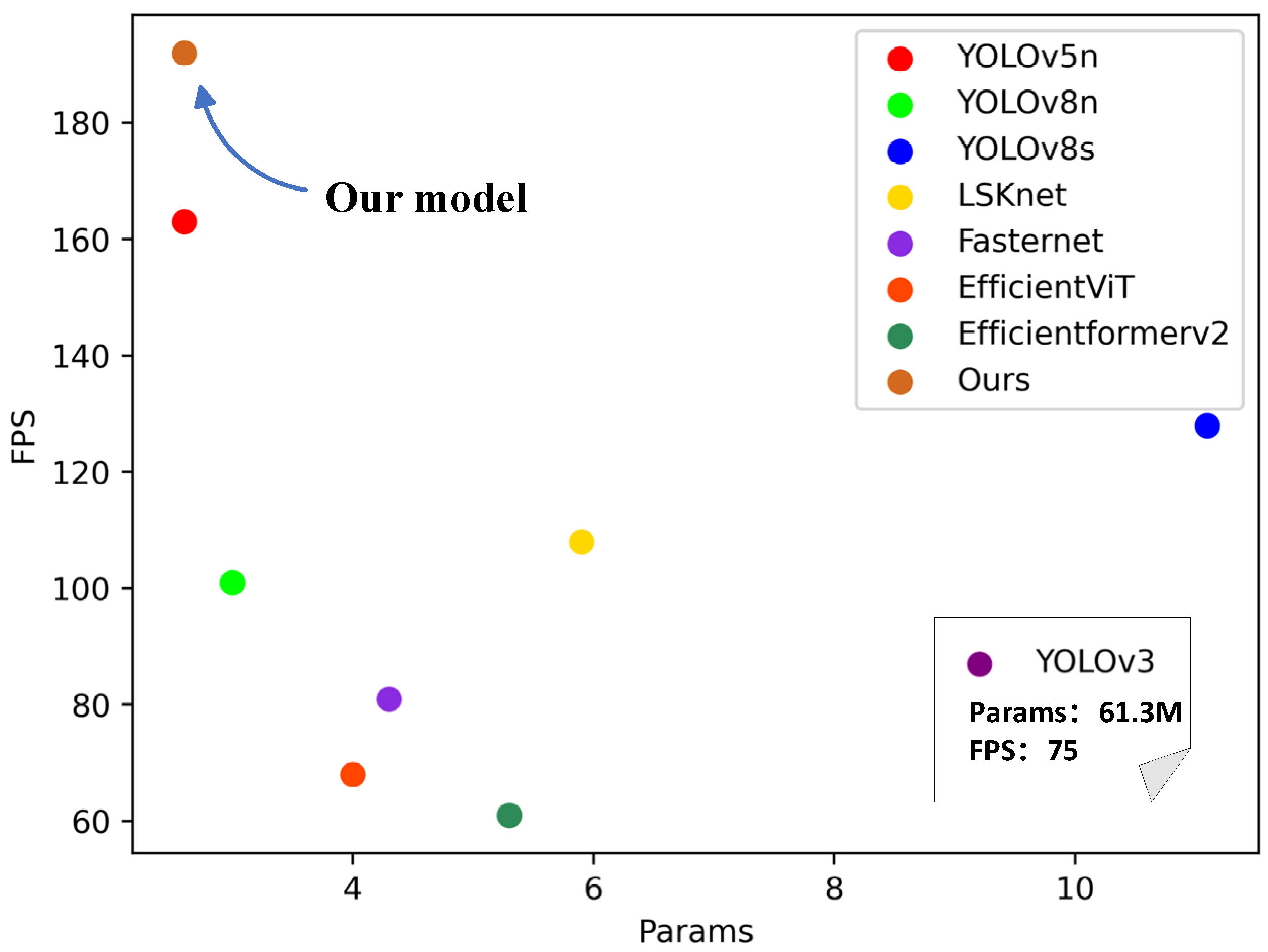

To validate the superiority of the algorithm proposed in this study on the glove dataset, we juxtaposed YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f with prevalent object detection algorithms, including YOLOv3, YOLOv5, YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, LSKnet, Fasternet, EfficientViT, and Efficientformerv2. As depicted in

Figure 13, the performance of YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f stands out impressively.

For a fair comparison of the inference performance of the models in

Table 4 on the glove dataset, we replaced the YOLOv8 backbone network with Fasternet, EfficientViT, and Efficientformerv2, retaining YOLOv8’s head and detect. The experimental results, as illustrated in

Figure 4, show that compared to other models, the YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f model achieves the best performance in terms of mAP50%, FPS, and parameter quantity. Relative to the baseline model YOLOv8, our model sees a 2.6% rise in mAP50%, a 90.1% surge in FPS, and a 13% decrease in model parameters. When juxtaposed with the YOLOv8s, which ranks second in mAP@50%, the YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f model has 77% fewer parameters. Compared to the similarly parameterized YOLOv5 model, the enhanced YOLOv8 model registers a 1.5% boost in mAP@50% and an 18% ascent in FPS. This underscores that the refined YOLOv8 boasts higher precision, superior real-time monitoring capability, and reduced hardware demands. Through these comparative metrics, the YOLOv8 algorithm improvement proposed in this study manifests superior comprehensive performance, making it more fitting for deployment in resource-constrained factories for precise real-time glove-wearing detection.

6.3. Ablation Study.

To validate the effectiveness of the various improvement modules in the enhanced YOLOv8 model, we conducted several rounds of ablation studies. As shown in

Table 5, our YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f model demonstrated the best performance.

In our experiments, we initially selected the baseline model YOLOv8, which had an mAP50 of 0.959 and a parameter count of 3.01M. Upon integrating the AFPN module into this model, its mAP50 increased to 0.964, with a slight reduction in parameter count to 2.74M. This suggests that the AFPN can effectively enhance the model’s detection accuracy while optimizing its parameter count. Subsequently, we tested the YOLOv8+AFPN+C2f configuration, achieving an mAP50 of 0.942 and a parameter count of 2.31M. Although the parameter count was marginally lower, there was a significant decrease in mAP50. This might indicate that the C2f module can efficiently reduce the model’s parameters, potentially at the cost of some detection accuracy. Ultimately, our YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f model, denoted as "Ours", exhibited the best performance in all tests, achieving an mAP50 of 0.972 with a parameter count of 2.60M. These findings demonstrate that our refined strategy achieves an optimal balance when considering both detection accuracy and model complexity.

6.4. The Experiments of Methods to Enhance AFPN

6.4.1. Experiments with various feature extraction modules replacing Blocks.

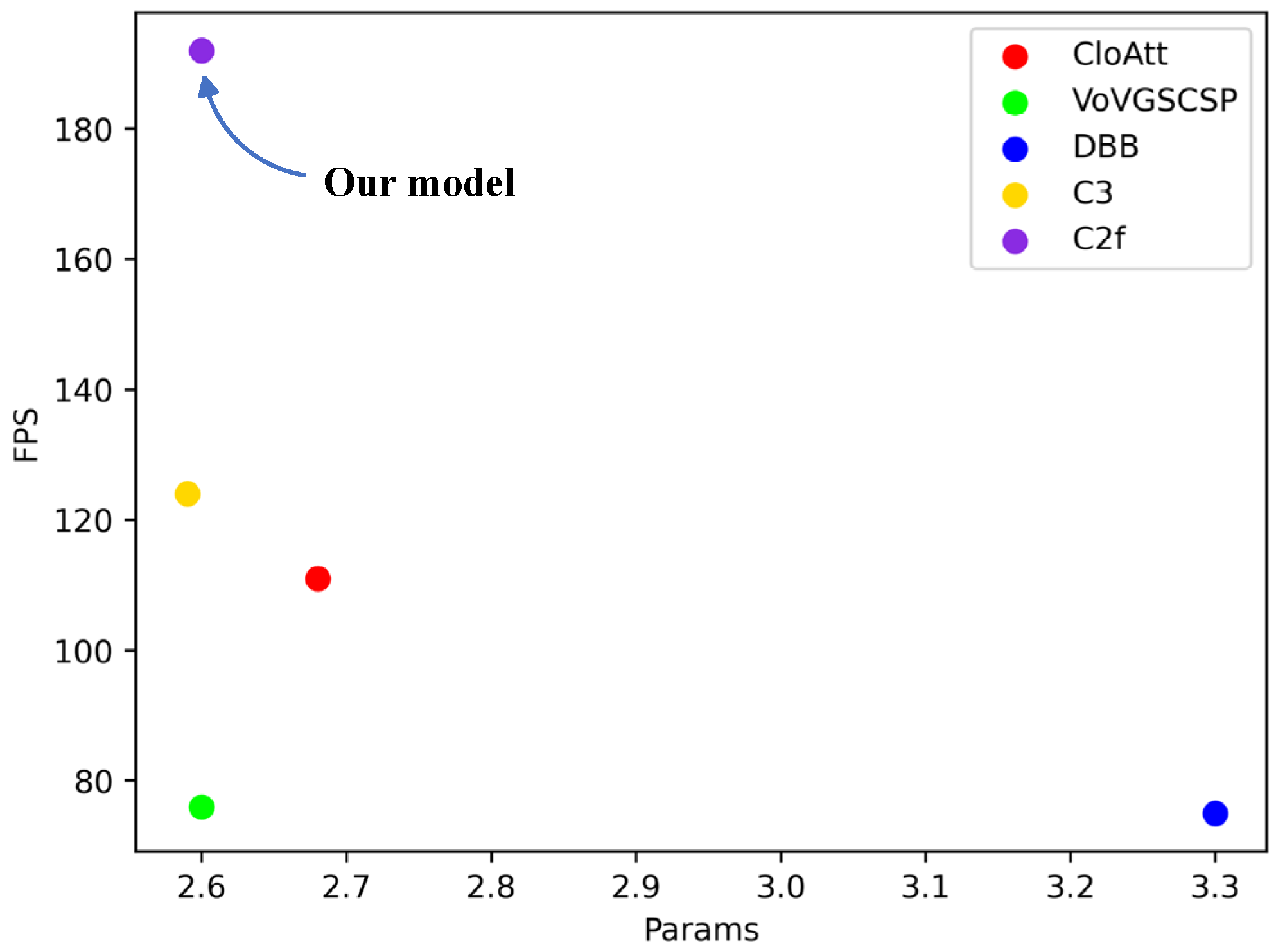

In this study, we enhanced the AFPN network by replacing the Blocks module with the C2f module. To illustrate the superiority of the C2f module over other feature extraction modules, we conducted comparative experiments in which various network feature extraction modules substituted the Blocks in AFPN. Specifically, we replaced the original Blocks in AFPN with the CloAtt, Faster, VoVGSCSP, DBB, and C3 modules respectively.

As presented in

Table 6, the model employing C2f in place of Blocks led the pack in both mAP50% and FPS. It achieved a 1.25% higher mAP50% compared to the best-performing VoVGSCSP module and outperformed the most lightweight C3 module by 54% in terms of FPS.

Figure 14 illustrates the relationship between the parameter count and FPS for each model. The graph underscores that the AFPN network equipped with C2f exhibits optimal performance, underscoring that C2f is indeed the most suitable feature extraction module to replace Blocks in AFPN.

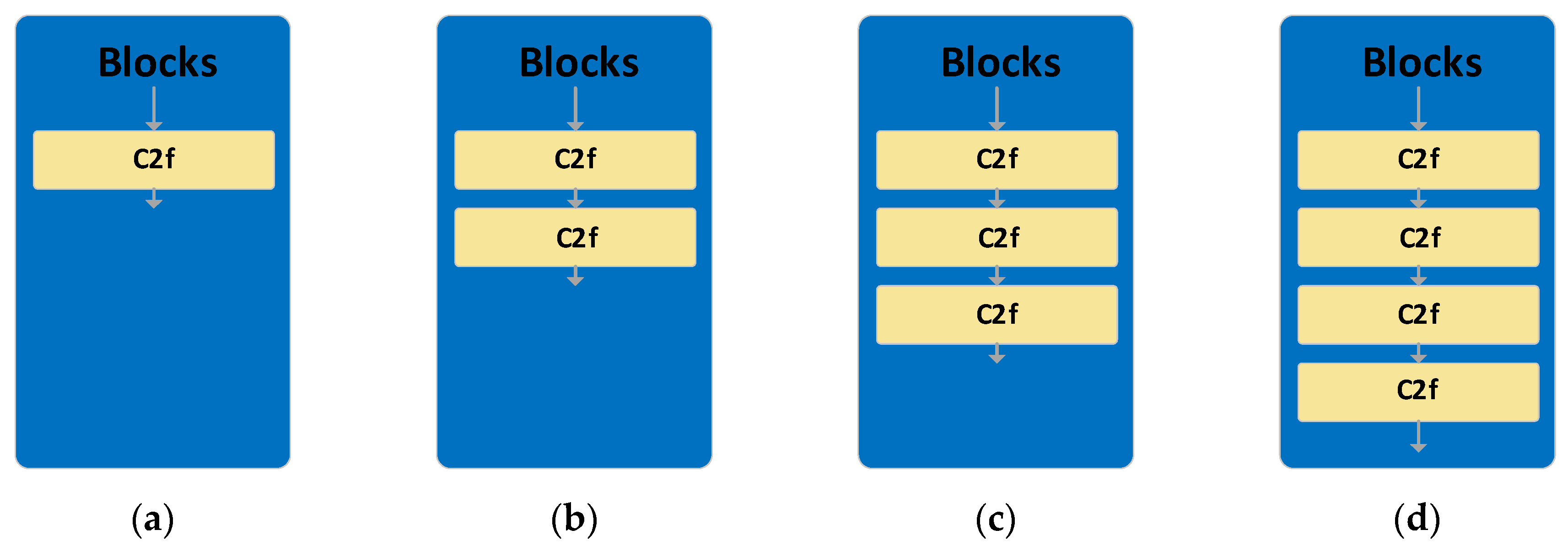

6.4.2. Number of C2f modules in series.

This section examines the impact on model performance when varying the number of C2f modules in series to replace the Blocks.

Figure 15 shows four cascading configurations with the number of C2f ranging from 1 to 4. As seen in

Table 7, under all test conditions such as Bare hand, White glove, Canvas glove, and Black glove, the model with a single C2f cascade always exhibits higher mAP50 performance. Specifically, when the number of C2f cascades is 1, the overall mAP50 of the model is higher than the other configurations. With the increase in the number of C2f cascades, there is a declining trend in mAP50 performance, especially evident in configurations with 3 and 4 C2f.

From the FPS and Params data, it’s evident that as the number of C2f cascades increases, the frames per second (FPS) gradually decline, and the model’s parameter count (Params) ascends. This suggests that an escalation in model complexity, while adding computational and storage overheads, doesn’t yield a commensurate boost in performance.

In summary, compared to the more intricate multi-cascade C2f structures, the single C2f cascade model consistently exhibits superior performance across all test conditions.

7. Conclusions

Glove detection in workshops is confronted with the challenges of limited computational resources on edge devices and intricate backgrounds. To tackle these issues, this study introduces the YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f model. This model preserves the YOLOv8’s backbone network and substitutes its head with AFPN. An added feature layer, enriched with shallow feature information, and the employment of the C2f module, boosts AFPN’s feature extraction prowess. Moreover, we delved into the experimental exploration of the number of concatenated C2f modules. Ultimately, we validated the enhanced YOLOv8’s performance on a glove dataset and, through comparative experiments with contemporary advanced models, determined that our refined YOLOv8 achieved exemplary outcomes in mAP@50%, parameter count, and FPS.

While our YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f model has reduced the parameter size and enhanced FPS, deploying it to edge devices for smooth and stable object detection in scenarios with extremely scarce computational resources remains a challenging endeavor. We will investigate methods to significantly reduce the model’s parameter size without compromising its accuracy, ensuring its adaptability to environments with critically limited computing resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L; methodology, S.L.; investigation, H.H.; data curation,M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, X.M.; visualization, L.X.; supervision, Y.L.; funding acquisition, X.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The foundational data for this article is derived from CHENGDU ZHENGXI HYDRAULIC PRESS company. The derived data generated in this study will be shared with the respective authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Emmanuel, N.O., Perceived Health Problems, Safety Practices and Performance Level among Workers of cement industries in Niger Delta.

- Osonwa Kalu, O.; Eko Jimmy, E.; Ozah-Hosea, P., Utilization of personal protective equipments (PPEs) among wood factory workers in Calabar Municipality, Southern Nigeria. Age 2015, 15, (19), 14.

- Tramontana, M.; Hansel, K.; Bianchi, L.; Foti, C.; Romita, P.; Stingeni, L., Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from a glue: concomitant sensitivity to “declared” isothiazolinones and “undeclared”(meth) acrylates. Contact Dermatitis 2020, 83, (2), 150-152.

- Girshick, R., In Fast r-cnn, Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2015; 2015; pp. 1440-1448.

- Dai, J.; Li, Y.; He, K.; Sun, J., R-fcn: Object detection via region-based fully convolutional networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2016, 29.

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R., In Mask r-cnn, Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017; 2017; pp. 2961-2969.

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A., In You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection, Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; 2016; pp. 779-788.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A., In YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger, Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; 2017; pp. 7263-7271.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A., Yolov3: An incremental improvement. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:1804.02767 2018.

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.; Liao, H.M., Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2004.10934 2020.

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.; Berg, A.C., In Ssd: Single shot multibox detector, Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14, 2016; Springer: 2016; pp. 21-37.

- Law, H.; Deng, J., In Cornernet: Detecting objects as paired keypoints, Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018; 2018; pp. 734-750.

- Zhao, Q.; Sheng, T.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cai, L.; Ling, H., In M2det: A single-shot object detector based on multi-level feature pyramid network, Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2019; 2019; pp. 9259-9266.

- Roy, A.M.; Bhaduri, J., DenseSPH-YOLOv5: An automated damage detection model based on DenseNet and Swin-Transformer prediction head-enabled YOLOv5 with attention mechanism. Adv Eng Inform 2023, 56, 102007.

- Jiang, S.; Zhou, X., DWSC-YOLO: A Lightweight Ship Detector of SAR Images Based on Deep Learning. J Mar Sci Eng 2022, 10, (11), 1699. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, S.; Qu, P.; Wu, X.; Feng, P.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y., MCA-YOLOV5-Light: A faster, stronger and lighter algorithm for helmet-wearing detection. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, (19), 9697. [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.R.; Huang, W., In Tood: Task-aligned one-stage object detection, 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021; IEEE Computer Society: 2021; pp. 3490-3499.

- Lin, T.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P., In Focal loss for dense object detection, Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017; 2017; pp. 2980-2988.

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R., In Mask r-cnn, Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017; 2017; pp. 2961-2969.

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N., In Cascade r-cnn: Delving into high quality object detection, Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; 2018; pp. 6154-6162.

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V., In Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; 2020; pp. 10781-10790.

- Wang, K.; Liew, J.H.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J., In Panet: Few-shot image semantic segmentation with prototype alignment, proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019; 2019; pp. 9197-9206.

- Yang, G.; Lei, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Feng, Z.; Liang, R., AFPN: Asymptotic Feature Pyramid Network for Object Detection. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2306.15988 2023.

- Liu, S.; Huang, D., In Receptive field block net for accurate and fast object detection, Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018; 2018; pp. 385-400.

- Liang, J.; Deng, Y.; Zeng, D., A deep neural network combined CNN and GCN for remote sensing scene classification. Ieee J-Stars 2020, 13, 4325-4338. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Li, Y.; Hou, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Cheng, M.; Yang, J.; Li, X., Large Selective Kernel Network for Remote Sensing Object Detection. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2303.09030 2023.

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.; Chan, S.G., In Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023; 2023; pp. 12021-12031.

- Liu, X.; Peng, H.; Zheng, N.; Yang, Y.; Hu, H.; Yuan, Y., In EfficientViT: Memory Efficient Vision Transformer with Cascaded Group Attention, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023; 2023; pp. 14420-14430.

- Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Wen, Y.; Evangelidis, G.; Salahi, K.; Wang, Y.; Tulyakov, S.; Ren, J., In Rethinking vision transformers for mobilenet size and speed, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; 2023; pp. 16889-16900.

- Fan, Q.; Huang, H.; Guan, J.; He, R., Rethinking Local Perception in Lightweight Vision Transformer. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2303.17803 2023.

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q., Slim-neck by GSConv: A better design paradigm of detector architectures for autonomous vehicles. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2206.02424 2022.

- Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Ding, G., In Diverse branch block: Building a convolution as an inception-like unit, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021; 2021; pp. 10886-10895.

Figure 1.

Performance comparison of the YOLO series models: (a) Model’s mAP versus parameter count graph (b) Model’s mAP versus inference speed graph.

Figure 1.

Performance comparison of the YOLO series models: (a) Model’s mAP versus parameter count graph (b) Model’s mAP versus inference speed graph.

Figure 2.

The model training procedure.

Figure 2.

The model training procedure.

Figure 3.

The structure of the YOLOv8 module.

Figure 3.

The structure of the YOLOv8 module.

Figure 4.

The structure of YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f.

Figure 4.

The structure of YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f.

Figure 5.

The structure of AFPN-M-C2f.

Figure 5.

The structure of AFPN-M-C2f.

Figure 6.

The Feature Vector Adjustment Module.(a) Downsampling model;(b)Upsampling model.

Figure 6.

The Feature Vector Adjustment Module.(a) Downsampling model;(b)Upsampling model.

Figure 7.

Adaptively spatial feature fusion model (a) ASFF_n;(b) ASFF_2.

Figure 7.

Adaptively spatial feature fusion model (a) ASFF_n;(b) ASFF_2.

Figure 8.

The original architecture of the feature extraction module in AFPN.(a) Blocks model;(b) BasicBlock model.

Figure 8.

The original architecture of the feature extraction module in AFPN.(a) Blocks model;(b) BasicBlock model.

Figure 9.

The architecture of the C2f module.(a)The structure of C2f;(b)Bottleneck in C2f.

Figure 9.

The architecture of the C2f module.(a)The structure of C2f;(b)Bottleneck in C2f.

Figure 10.

The feature fusion network architecture.(a) AFPN-M extracts features from the {P2, P3, P4, P5} layers of the main network.(b)Traditional FPN, exemplified by AFPN, extracts features from the {P3, P4, P5} layers.

Figure 10.

The feature fusion network architecture.(a) AFPN-M extracts features from the {P2, P3, P4, P5} layers of the main network.(b)Traditional FPN, exemplified by AFPN, extracts features from the {P3, P4, P5} layers.

Figure 11.

Unprocessed images from the glove dataset.

Figure 11.

Unprocessed images from the glove dataset.

Figure 12.

Predicted outcomes, (a) The images in the first column represent the prediction results of YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f.(b) The images in the second column depict the outcomes from YOLOv8 (baseline).

Figure 12.

Predicted outcomes, (a) The images in the first column represent the prediction results of YOLOv8-AFPN-M-C2f.(b) The images in the second column depict the outcomes from YOLOv8 (baseline).

Figure 13.

Comparison of FPS and Params performance across different models. Due to the large parameter size of the YOLOv3 model, we list its parameters and FPS separately, placing them in the bottom right corner of the axis.

Figure 13.

Comparison of FPS and Params performance across different models. Due to the large parameter size of the YOLOv3 model, we list its parameters and FPS separately, placing them in the bottom right corner of the axis.

Figure 14.

Scatter plot of parameters-FPS for different modules replacing blocks.

Figure 14.

Scatter plot of parameters-FPS for different modules replacing blocks.

Figure 15.

Number of C2f modules used to replace the Blocks.(a)One C2f. (b)Two C2f. (c)Three C2f. (d)Four C2f.

Figure 15.

Number of C2f modules used to replace the Blocks.(a)One C2f. (b)Two C2f. (c)Three C2f. (d)Four C2f.

Table 1.

Experimental Environment Configuration.

Table 1.

Experimental Environment Configuration.

| Experimental Component |

Version |

| OS |

Ubuntu20.04 |

| CPU |

AMD EPYC 7T83 64-Core Processor |

| GPU |

RTX4090 |

| CUDA version |

11.8 |

| Python version |

3.8 |

| Pytorch version |

2.0.0 |

Table 2.

Parameters for model training.

Table 2.

Parameters for model training.

| Parameter Name |

Setting |

| Image dimensions |

|

| Number of epochs |

200 |

| Batch size |

64 |

| Data augmentation menthod |

Mosaic |

Table 3.

The hyperparameters for training.

Table 3.

The hyperparameters for training.

| Hyperparameter |

Value |

| gradient-based optimizers |

SGD |

initial learning rate(lr0)

final learning rate |

0.01

0.0001 |

| momentum |

0.937 |

| Weight decay |

0.0005 |

Table 4.

Performance evaluation of different algorithms on the glove dataset.

Table 4.

Performance evaluation of different algorithms on the glove dataset.

| Model |

mAP50/(%) |

FPS |

Params/M |

| Bar hand |

White glove |

Canvas glove |

Black

glove |

All 1

|

P |

R |

| YOLOv3[9] |

0.935 |

0.944 |

0.972 |

0.987 |

0.959 |

0.97 |

0.91 |

75 |

61.3 |

| YOLOv5[26] |

0.924 |

0.936 |

0.984 |

0.989 |

0.958 |

0.96 |

0.89 |

163 |

2.6 |

| YOLOv8[27] |

0.934 |

0.914 |

0.947 |

0.994 |

0.947 |

0.95 |

0.89 |

101 |

3.0 |

| YOLOv8s[27] |

0.957 |

0.952 |

0.984 |

0.986 |

0.970 |

0.95 |

0.93 |

128 |

11.1 |

| LSKnet[28] |

0.919 |

0.917 |

0.958 |

0.974 |

0.942 |

0.95 |

0.90 |

108 |

5.9 |

| Fasternet[29] |

0.949 |

0.938 |

0.944 |

0.944 |

0.956 |

0.96 |

0.89 |

81 |

4.3 |

| EfficientViT[30] |

0.919 |

0.917 |

0.993 |

0.985 |

0.954 |

0.95 |

0.93 |

68 |

4.0 |

| Efficientformerv2[31] |

0.932 |

0.911 |

0.959 |

0.991 |

0.948 |

0.94 |

0.91 |

61 |

5.3 |

| Ours |

0.949 |

0.962 |

0.983 |

0.992 |

0.972 |

0.96 |

0.91 |

192 |

2.6 |

Table 5.

Experimental results of the ablation experiment.

Table 5.

Experimental results of the ablation experiment.

| Model |

AFPN |

More Detect head |

C2f |

mAP50(%) |

Params/M |

| YOLOv8n(baseline) |

|

|

|

0.959 |

3.01 |

| YOLOv8+AFPN |

√ |

|

|

0.964 |

2.74 |

| YOLOv8+AFPN+ more Detect head |

√ |

√ |

|

0.956 |

3.00 |

| YOLOv8+AFPN+C2f |

√ |

|

√ |

0.942 |

2.31 |

| Ours |

√ |

√ |

√ |

0.972 |

2.60 |

Table 6.

Evaluation of performance using different modules to replace blocks.

Table 6.

Evaluation of performance using different modules to replace blocks.

| Model |

mAP50/(%) |

FPS |

Params/M |

| Bare hand |

White glove |

Canvas glove |

Black

glove |

All1

|

P |

R |

| CloAtt[32] |

0.927 |

0.962 |

0.953 |

0.995 |

0.959 |

0.96 |

0.92 |

111 |

2.68 |

| VoV-GSCSP[33] |

0.949 |

0.952 |

0.957 |

0.982 |

0.96 |

0.97 |

0.91 |

76 |

2.60 |

| DBB[34] |

0.932 |

0.943 |

0.937 |

0.995 |

0.952 |

0.95 |

0.89 |

75 |

3.3 |

| C3 2[26] |

0.928 |

0.874 |

0.940 |

0.995 |

0.934 |

0.96 |

0.88 |

124 |

2.59 |

| C2f(ours) |

0.949 |

0.962 |

0.983 |

0.992 |

0.972 |

0.96 |

0.91 |

192 |

2.60 |

Table 7.

The influence of the number of C2f modules in Blocks on the model’s performance.

Table 7.

The influence of the number of C2f modules in Blocks on the model’s performance.

| The number of C2f |

mAP50/(%) |

FPS |

Params/M |

| Bare hand |

White glove |

Canvas glove |

Black

glove |

All1

|

P |

R |

| 1(ours) |

0.949 |

0.962 |

0.983 |

0.992 |

0.972 |

0.96 |

0.91 |

192 |

2.60 |

| 2 |

0.940 |

0.942 |

0.960 |

0.981 |

0.956 |

0.96 |

0.90 |

93 |

2.65 |

| 3 |

0.954 |

0.942 |

0.949 |

0.995 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

0.92 |

72 |

2.70 |

| 4 |

0.949 |

0.932 |

0.958 |

0.994 |

0.958 |

0.96 |

0.90 |

75 |

2.75 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).