Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Afghan and Aran Refugee Women

1.2. Refugee Women’s Approach Toward Domestic Violence

1.3. Impact of Religion and Cultural Norms on Gender Roles, Domestic Violence and Divorce

1.4. Impact of Family Structure

2. Methods

2.1. Methodological Framework

2.1.1 Arksey and O'Malley Framework: Stage 1 - Identify the Review Question

2.1.2. Arksey and O'Malley Framework: Stage 2- Identify Relevant Literature

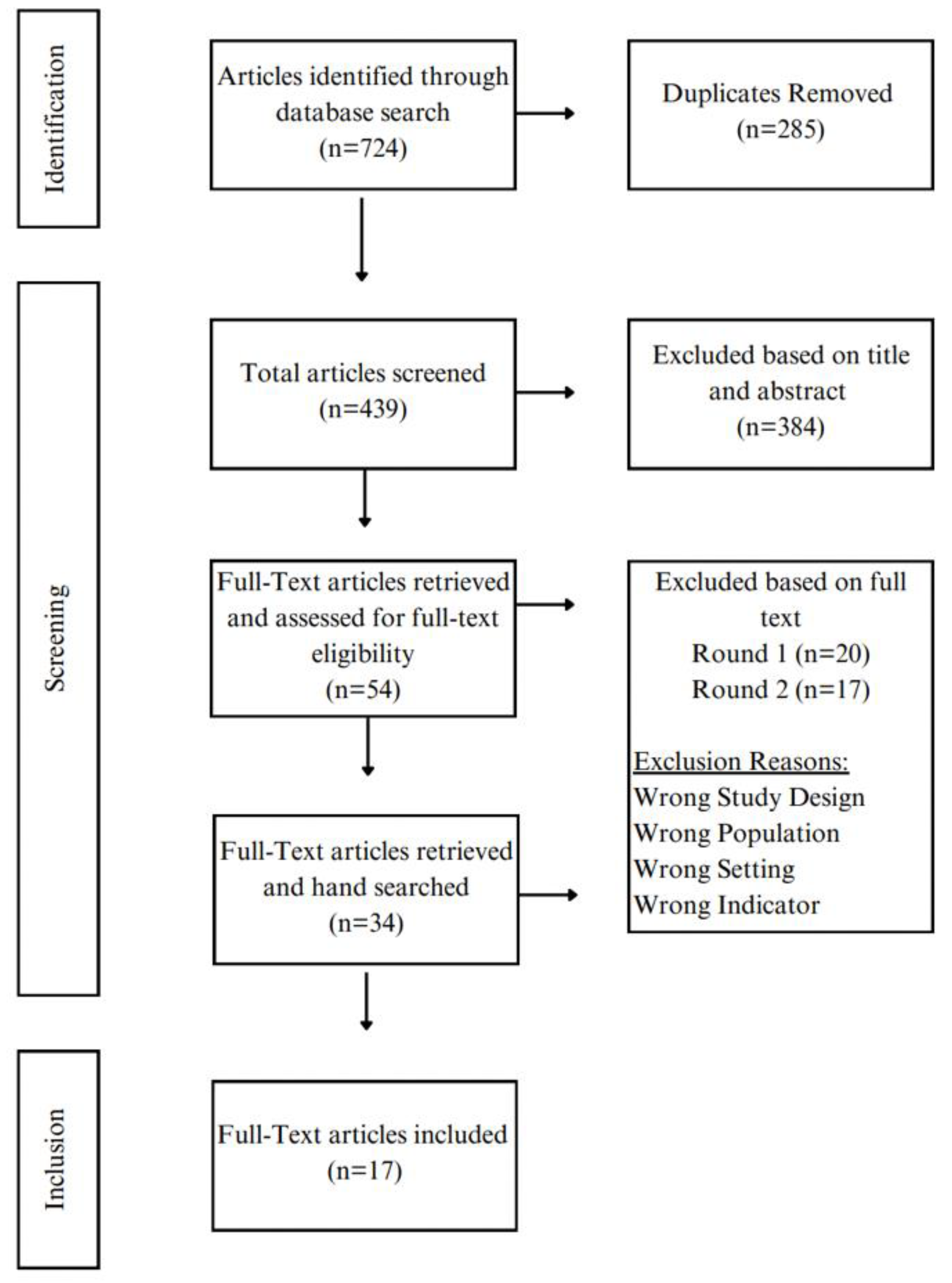

2.1.3. Arksey and O'Malley Framework: Stage 3- Selecting Studies

2.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

2.1.4. Arksey and O'Malley Framework: Stage 4- Extracting, Mapping, and Charting the Data

2.1.5. Arksey and O'Malley Framework: Stage 5- Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Data

3. Results

3.1. Thematic Analysis

3.1.1. Refugee Women’s Attitudes Toward Domestic Violence

3.1.2. Refugee Women’s Help-Seeking Behaviors in Case of Domestic Violence

3.1.3. Stakeholders’ Attitudes and/or Behaviors Toward Domestic Violence

3.1.4. Recommendations for Future Work

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Points

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboulhassan, Salam, and Krista M. Brumley. 2019. "Carrying the Burden of a Culture: Bargaining With Patriarchy and the Gendered Reputation of Arab American Women." Journal of Family Issues 40 (5). SAGE Publications Inc: 637–61. [CrossRef]

- Abugideiri, Salma Elkadi. 2010. “A Perspective on Domestic Violence in the Muslim Community.” FaithTrust Institute.

- Abu-Ras, Wahiba. 2007. "Cultural Beliefs and Service Utilization by Battered Arab Immigrant Women." Violence Against Women 13 (10). SAGE Publications Inc: 1002–28. [CrossRef]

- "Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2022-2023 | UNICEF Afghanistan." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://www.unicef.org/afghanistan/reports/afghanistan-multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-mics-2022-2023.

- "Afghanistan Refugee Crisis Explained." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://www.unrefugees.org/news/afghanistan-refugee-crisis-explained/.

- Afrouz, Rojan, Beth R Crisp, and Ann Taket. 2021a. "Experiences of Domestic Violence among Newly Arrived Afghan Women in Australia, a Qualitative Study." The British Journal of Social Work 51 (2): 445–64. [CrossRef]

- Afrouz, Rojan, Beth R. Crisp, and Ann Taket. 2021b. "Understandings and Perceptions of Domestic Violence Among Newly Arrived Afghan Women in Australia." Violence Against Women 27 (14). SAGE Publications Inc: 2511–29. [CrossRef]

- Afrouz, Rojan, Beth R. Crisp, and Ann Take. 2023. "Afghan Women's Barriers to Seeking Help for Domestic Violence in Australia." Australian Social Work 76 (2). Routledge: 217–30. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kazi, L. 2008. "Divorce: A structural problem not just a personal crisis." J. Comp. Fam. Stud. (39): 241–257. [CrossRef]

- Al-Krenawi, A., & Jackson, S. O. (2014). "Arab American marriage: Culture, tradition, religion, and the social worker." Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 24(2), 115–137. [CrossRef]

- Anahid Dervartanian Kulwicki, June Miller, null. 1999. "Domestic Violence in the Arab American Population: Transforming Environmental Conditions Through Community Education." Issues in Mental Health Nursing 20 (3). Taylor & Francis: 199–215. [CrossRef]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O'Malley. 2005. "Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework." International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1). Routledge: 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Astbury, Jamie, Patricia Easteal, Jane Atkinson, Joanne Duke, Peter Tait, and James Turner. 2013. "The Impact of Domestic Violence on Individuals," July.

- "At a Memorandum of Understanding Signing Ceremony with the #AfghanEvac Coalition - United States Department of State." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://www.state.gov/at-a-memorandum-of-understanding-signing-ceremony-with-the-afghanevac-coalition/.

- “Ayah Al-Baqarah (The Cow) 2:229.” 2023. Accessed September 29. https://www.islamawakened.com/quran/2/229/.

- Balice, Guy, Shayne Aquino, Shelly Baer, and Mallory Behar. 2019. "A Review of Barriers to Treating Domestic Violence for Middle Eastern Women Living in the United States." https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335403510_A_Review_of_Barriers_to_Treating_Domestic_Violence_for_Middle_Eastern_Women_Living_in_the_United_States.

- Barakat, Halim. 1993. The Arab World: Society, Culture, and State. University of California Press.

- Batalova, Jeanne Batalova Nicole Ward and Jeanne. 2023. "Refugees and Asylees in the United States." Migrationpolicy.Org. June 13. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/refugees-and-asylees-united-states.

- Btoush, Rula, and Muhammad Haj-Yahia. 2008. "Attitudes of Jordanian Society Toward Wife Abuse - Rula Btoush, Muhammad M. Haj-Yahia, 2008" 23 (11). [CrossRef]

- Cohen, O., & Finzi-Dottan, R. (2012). Reasons for divorce and mental health following the breakup. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 53(8), 581–601. [CrossRef]

- Coker, Ann L, Christina Derrick, Julia L Lumpkin, Timothy E Aldrich, and Robert Oldendick. 2000. "Help-Seeking for Intimate Partner Violence and Forced Sex in South Carolina." American Journal of Preventive Medicine 19 (4): 316–20. [CrossRef]

- "Covidence - Better Systematic Review Management." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://www.covidence.org/.

- "Demographics — Arab American Institute." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://www.aaiusa.org/demographics.

- Dhami, S., and A. Sheikh. 2000. “The Muslim Family: Predicament and Promise.” The Western Journal of Medicine 173 (5): 352–56. [CrossRef]

- Dollahite, David C., Loren D. Marks, and Hilary Dalton. 2018. “Why Religion Helps and Harms Families: A Conceptual Model of a System of Dualities at the Nexus of Faith and Family Life.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 10 (1): 219–41. [CrossRef]

- Elghossain, Tatiana, Sarah Bott, Chaza Akik, and Carla Makhlouf Obermeyer. 2019. "Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence against Women in the Arab World: A Systematic Review." BMC International Health and Human Rights 19 (1): 29. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, N.S., Schoebi, D. 2017. "Research on correlates of marital quality and stability in Muslim countries: A review." J. Fam. Theory Rev. 9, 69–92.

- "Facts and Figures: Ending Violence against Women and Girls." 2023. UN Women – Arab States. Accessed September 13. https://arabstates.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures-0.

- Fariyal Ross-Sheriff. 2013. "CONTAGION OF VIOLENCE AGAINST REFUGEE WOMEN IN MIGRATION AND DISPLACEMENT." In Contagion of Violence: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207254/.

- Fernández-Fontelo, Amanda, Alejandra Cabaña, Harry Joe, Pedro Puig, and David Moriña. 2019. "Untangling Serially Dependent Underreported Count Data for Gender-Based Violence." Statistics in Medicine 38 (22): 4404–22. [CrossRef]

- Frisby, B. N., Booth-Butterfield, M., Dillow, M. R., Martin, M. M., & Weber, K. D. 2012. "Face and resilience in divorce: The impact on emotions, stress, and post-divorce relationships." Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 29(6), 715–735. [CrossRef]

- Gennari, Marialuisa, Cristina Giuliani, and Monica Accordini. 2017. "Muslim Immigrant Men's and Women's Attitudes Towards Intimate Partner Violence." Europe's Journal of Psychology 13 (4): 688–707. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Andrew, Julienne Corboz, Esnat Chirwa, Carron Mann, Fazal Karim, Mohammed Shafiq, Anna Mecagni, Charlotte Maxwell-Jones, Eva Noble, and Rachel Jewkes. 2020. "The Impacts of Combined Social and Economic Empowerment Training on Intimate Partner Violence, Depression, Gender Norms and Livelihoods among Women: An Individually Randomised Controlled Trial and Qualitative Study in Afghanistan." BMJ Global Health 5 (3). BMJ Specialist Journals: e001946. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, Mariana, and Marlene Matos. 2016. "Prevalence of Violence against Immigrant Women: A Systematic Review of the Literature." Journal of Family Violence 31 (6): 697–710. [CrossRef]

- Gracia, Enrique. 2004. "Unreported Cases of Domestic Violence against Women: Towards an Epidemiology of Social Silence, Tolerance, and Inhibition." Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 58 (7). BMJ Publishing Group Ltd: 536–37. [CrossRef]

- Haj-Yahia, Muhammad M. 2000. “Wife Abuse and Battering in the Sociocultural Context of Arab Society*.” Family Process 39 (2): 237–55. [CrossRef]

- Holtmann, Catherine. 2016. "Christian and Muslim Immigrant Women in the Canadian Maritimes: Considering Their Strengths and Vulnerabilities in Responding to Domestic Violence." Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 45 (3). SAGE Publications Ltd: 397–414. [CrossRef]

- "How Domestic Violence Impacts Women's Economic Participation & Family Well-Being in Refugee Resettlement, 2017." 2017. Asian Pacific Institute on Gender Based Violence Website. July 27. https://www.api-gbv.org/resources/economic-security-refugee-resettlement/.

- Karshenas, M and Moghadam, VM. 2001. “Female Labor Force Participation and Economic Adjustment in the MENA Region,” in Mine Cinar, ed., The Economics of Women and Work in the Middle East and North Africa (Amsterdam, Netherlands: JAI Press): 51–74.

- Kulwicki, Anahid, Barbara Aswad, Talita Carmona, and Suha Ballout. 2010. "Barriers in the Utilization of Domestic Violence Services Among Arab Immigrant Women: Perceptions of Professionals, Service Providers & Community Leaders." Journal of Family Violence 25 (8): 727–35. [CrossRef]

- Lamer, Wiebke. 2011. "Afghan Ethnic Groups: A Brief Investigation.

- Larsen, Mandi M. 2016. Health Inequities Related to Intimate Partner Violence Against Women. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and Kelly K. O'Brien. 2010. "Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology." Implementation Science 5 (1): 69. [CrossRef]

- Lins, Liliane, and Fernando Martins Carvalho. 2016. "SF-36 Total Score as a Single Measure of Health-Related Quality of Life: Scoping Review." SAGE Open Medicine 4 (October): 2050312116671725. [CrossRef]

- Mannell, Jenevieve, Gulraj Grewal, Lida Ahmad, and Ayesha Ahmad. 2021. "A Qualitative Study of Women's Lived Experiences of Conflict and Domestic Violence in Afghanistan." Violence against Women 27 (11): 1862–78. [CrossRef]

- Massoud Karshenas and Valentine M. Moghadam, “Female Labor Force Participation and Economic Adjustment in the MENA Region,” in Mine Cinar, ed., The Economics of Women and Work in the Middle East and North Africa (Amsterdam, Netherlands: JAI Press, 2001): 51–74.

- Meguid, Abdel, and Mona Bakry. 2006. "Measuring Arab Immigrant Women's Definition of Marital Violence: Creating and Validating an Instrument for Use in Social Work Practice." The Ohio State University. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/etd/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=osu1148507126.

- Menjovar, Cecilia, and Olivia Salcido. 2002. "Immigrant Women and Domestic Violence: Common Experiences in Different Countries." Gender & Society 16 (6). SAGE Publications Inc: 898–920. [CrossRef]

- "Middle East and North Africa." 2023. Global Focus. Accessed September 23. https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/regions/middle-east-and-north-africa.

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and PRISMA Group. 2009. "Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement." PLoS Medicine 6 (7): e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Mojahed, Amera, Nada Alaidarous, Hanade Shabta, Janice Hegewald, and Susan Garthus-Niegel. 2022. "Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the Arab Countries: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors." Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 23 (2). SAGE Publications: 390–407. [CrossRef]

- Moshtagh, Mozhgan, Rana Amiri, Simin Sharafi, and Morteza Arab-Zozani. 2023. "Intimate Partner Violence in the Middle East Region: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24 (2). SAGE Publications: 613–31. [CrossRef]

- “Most Women in Afghanistan Justify Domestic Violence.” 2023. PRB. Accessed September 29. https://www.prb.org/resources/most-women-in-afghanistan-justify-domestic-violence/.

- Organization, World Health. 2021. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence against Women. Executive Summary. World Health Organization.

- Oyserman, D. (2017). Culture Three Ways: Culture and Subcultures Within Countries. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 435–463.

- Perales, F., & Bouma, G. (2019). Religion, religiosity and patriarchal gender beliefs: Understanding the Australian experience. Journal of Sociology, 55(2), 323–341. [CrossRef]

- Pottie, Kevin, Govinda Dahal, Katholiki Georgiades, Kamila Premji, and Ghayda Hassan. 2015. "Do First Generation Immigrant Adolescents Face Higher Rates of Bullying, Violence and Suicidal Behaviours Than Do Third Generation and Native Born?" Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17 (5): 1557–66. [CrossRef]

- "Power and Control Tactics Used against Immigrant Women." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://vawnet.org/material/power-and-control-tactics-used-against-immigrant-women.

- Quranic. 2021. “5 Verses About Divorce In The Quran, Divorce in Islam | Quranic Arabic.” Quranic Arabic For Busy People. November 16. https://www.getquranic.com/5-verses-about-divorce-in-the-quran/.

- Reda L. On marriage and divorce in Egypt. [(accessed on September 25, 2023)];Egypt Today. 2019 Feb 28; Available online: http://www.egypttoday.com/Article/6/66379/On-Marriage-and-Divorce-in-Egypt.

- "Refugee Crises in the Arab World - Carnegie Endowment for International Peace." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/10/18/refugee-crises-in-arab-world-pub-77522.

- Rubin, Barnett R. 2002. The Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and Collapse in the International System. Yale University Press.

- Samaha N. Master’s Thesis. The American University in Cairo; Cairo, Egypt: 2016. [(accessed on September 18, 2023]. Khul’ in Egypt Between Theory and Practice a Critical Analysis for Khul’ Implementation. Spring. Available online: http://dar.aucegypt.edu/bitstream/handle/10526/5015/NIVINESAMAHA%20THESIS%20FINAL.pdf?sequence=3.

- Shalabi, Dina, Steven Mitchell, and Neil Andersson. 2015. "Review of Gender Violence Among Arab Immigrants in Canada: Key Issues for Prevention Efforts." Journal of Family Violence 30 (7): 817–25. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, Patricia, Maureen O'Dougherty, and Erin Mehta. 2012. "Refugees' Perspectives on Barriers to Communication about Trauma Histories in Primary Care." Mental Health in Family Medicine 9 (1): 47–55.

- “Taking a Terrible Toll: The Taliban’s Education Ban.” 2023. United States Institute of Peace. Accessed September 29. https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/04/taking-terrible-toll-talibans-education-ban.

- "Thousands of Afghan Refugees Are Still Waiting for a Chance to Come to the US - The New York Times." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/12/us/afghanistan-refugees.html.

- Tlapek, Sarah Myers, J. Kale Monk, and Cheyenne White. 2020. "Relational Upheaval During Refugee Resettlement: Service Provider Perspectives." Family Relations 69 (4): 756–69. [CrossRef]

- "UNDP Annual Report 2014 | United Nations Development Programme." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://www.undp.org/publications/undp-annual-report-2014.

- "UNHCR - Refugee Statistics." 2023. Accessed September 23. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

- United Nations. 2023. "What Is Domestic Abuse?" United Nations. United Nations. Accessed September 25. https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse.

- Usta, Jinan, Jo Ann M. Farver, and Nora Pashayan. 2007. "Domestic Violence: The Lebanese Experience." Public Health 121 (3): 208–19. [CrossRef]

- Wachter, Karin, Laurie Cook Heffron, Jessica Dalpe, and Alison Spitz. 2021. "‘Where Is the Women’s Center Here?’: The Role of Information in Refugee Women’s Help Seeking for Intimate Partner Violence in a Resettlement Context.” Violence Against Women 27 (12–13). SAGE Publications Inc: 2355–76. [CrossRef]

- Wachter, Karin, Jessica Dalpe, and Laurie Cook Heffron. 2019. “Conceptualizations of Domestic Violence–Related Needs among Women Who Resettled to the United States as Refugees.” Social Work Research 43 (4): 207–19. [CrossRef]

- Westphaln, Kristi K, Wendy Regoeczi, Marie Masotya, Bridget Vazquez-Westphaln, Kaitlin Lounsbury, Lolita McDavid, HaeNim Lee, Jennifer Johnson, and Sarah D. Ronis. 2021. “From Arksey and O’Malley and Beyond: Customizations to Enhance a Team-Based, Mixed Approach to Scoping Review Methodology.” MethodsX 8 (January): 101375. [CrossRef]

- “Which Religions Are Practiced In The Middle East?” 2019. WorldAtlas. May 22. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/which-religions-are-practiced-in-the-middle-east.html.

- World Bank, Gender and Development in the Middle East and North Africa (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2004). See also World Bank, Gender and Development in the Middle East and North Africa: Women in the Public Sphere (Washington, DC: Social and Economic Development Department, 2003b).

- World Bank Report Women's Economic Participation in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon, 2014.Accessed September 20, 2023 at https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/868581592904029814-0280022020/original/StateoftheMashreqWomen.pdf.

- World Health Organization. 2005. “WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women : Initial Results on Prevalence, Health Outcomes and Women’s Responses.” World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43309.

- World Health Organization. 2015. “Addressing Violence against Women in Afghanistan: The Health System Response.” WHO/RHR/15.26. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/201704.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Afghan and or Arab Refugees; multi-ethnic studies should include Afghan and/or Arab refugees | Non-Afghan, non-Arab refugee study populations |

| Married male and/or female refugee adults 18 years of age and older | Unmarried refugee youth under 18 years of age, unless the study also includes married refugee adults over 18 years of age |

| Participants have been assessed for domestic violence (DV) or intimate partner violence (IPV) | Participation only in clinical trials |

| Study does not focus exclusively on psychiatric/counseling/medical treatments/interventions for DV or IPV | Study focuses exclusively on medical, psychiatric, or counseling assessment and treatment for DV or IPV |

| Peer-reviewed qualitative and/or quantitative research articles, scoping and systematic reviews | Non peer-reviewed, unfiltered information such as book chapters, editorials, commentaries, case studies, case reports, cohort or conference papers |

| Study carried out only on refugees resettled in developed Western host countries (USA, Canada, EU, Australia, New Zealand) | Study carried out on military personnel, veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, or outside of the above-mentioned developed Western host countries. |

| Study published during 1980-2022 | Study published before 1980 |

| Study published only in English | Study published in languages other than English |

| Study examines refugee attitudes and/or behaviors towards DV and/or IPV | Study with little or no attention to attitudes and/or behaviors towards DV and/or IPV |

| Study examines the impacts of gender acculturation on refugee attitudes and/or behaviors towards DV and/or IPV and/or evaluates assessment instruments. | Study does not address the correlations of DV and/or IPV with gender, class, generation (age), and acculturation variables of study population |

|

# |

COLUMN 1 Author information |

COLUMN 2 Research design & participant information |

COLUMN 3 Study aims |

COLUMN 4 Focus area |

COLUMN 5 Refugee post-resettlement attitudes towards DV |

COLUMN 6 Refugee post-resettlement behaviors toward DV |

COLUMN 7 Refugee community attitudes and/or behaviors towards DV |

COLUMN 8 Research, practice, and/or policy recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Afrouz, R., Crisp, B. R., & Taket, A. (2021). Understandings and Perceptions of Domestic Violence Among Newly Arrived Afghan Women in Australia. Violence Against Women, 27(14), 2511–2529. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220985937 | Semi-structured interviews with 21 newly arrived Afghan women in Australia. |

To explore newly arrived women’s understanding and perceptions of DV and whether they perceive this as normal/acceptable. | Domestic violence, experiences and perceptions around domestic violence | Attitudes changed based on educational level, English proficiency, personal experience of DV, years of living in Australia, connecting with host society, pursuing education. | Lack of knowledge and English impact perception of violence and response to it normalizing DV. |

Communities have different perspectives and definitions of DV, women might not get the support and assistance they need. |

Expand the community definition of DV to include various forms of abuse. Long-term and consistent community education and training should be delivered in collaboration with community members. |

| 2 | Afrouz, R., Crisp, B. R., & Taket, A. (2021). Experiences of Domestic Violence among Newly Arrived Afghan Women in Australia, a Qualitative Study, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 51, Issue 2, March 2021, Pages 445–464, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa143 | Semi-structured interviews with 21 newly arrived Afghan women in Australia. |

To understand Afghan women’s experiences of DV and their perceptions about the extent of DV in the Afghan refugee community. | Domestic violence, perception of domestic violence | Resettlement in a new environment impacted women’s perspectives on DV viewing it is abnormal and unacceptable. | Women less dependent and socially active in the host community. Husbands may not agree with this change, view it as a threat to their power leading to more controlling patterns. Immigration status and financial instability are barriers to emancipation. | Community normalization of DV enables further abuse. The normalization of violence is rooted in interpretations of Sharia law, cultural norms mandating that a bride should live in with in-laws, women should stay silent not to dishonor family, and an overall culture of male dominance. |

Promote changes at systemic levels: 1) religious leaders’ approach to DV 2) community support for DV laws, 3) agencies organizational approach to DV. Improve the cultural diversity of available supportive services |

| 3 | Afrouz, R., Crisp, B. R., & Taket, A. (2023): Afghan Women’s Barriers to Seeking Help for Domestic Violence in Australia, Australian Social Work, https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.2004179 | Semi-structured interviews with 21 newly arrived Afghan women in Australia. |

Barriers to seeking help for domestic violence, specifically experienced by Afghan women after settling in Australia | Domestic violence, help-seeking and barriers to help-seeking for domestic violence | Afghan culture dictated that a good woman did not disclose marital problems to others and that those who did so deserved negative judgments. |

Seeking help may not be possible considering financial barriers, children, and language barriers. |

Community shaming and labeling/blaming women who seek help for DV experiences. |

DV services priorities should match and respond to women’s needs. |

| 4 | Abu-Ras W. (2007). Cultural beliefs and service utilization by battered Arab immigrant women. Violence against women, 13(10), 1002–1028. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801207306019 | Structured survey collection in the US through in-person interviews with 67 Arab immigrant women from MENA. |

Relationship between cultural beliefs and service utilization of among Arab immigrant women clients of ACCESS’s Domestic Violence Prevention Project |

Partner abuse, attitudes and beliefs around partner abuse | For many women family is the building block of society and should be preserved at all cost. However, some women did not approve DV and saw it as an unacceptable abuse. | Women who did not justify wife-beating and did not blame victims for being the cause of DV have a higher chance of seeking and utilizing DV services. | Divorce is not approved nor accepted in the community. The Arab community has a patriarchal culture which often blames and shames female victims for being responsible for the DV. | Need for immediate action with supporting policies and interventions. Disseminate information on DV and on women’s rights to community including Arab men. Use spiritual and Islamic teaching to raise DV awareness and to stop violence against women. |

| 5 | Gennari, M., Giuliani, C., & Accordini, M. (2017). Muslim Immigrant Men's and Women's Attitudes Towards Intimate Partner Violence. Europe's journal of psychology, 13(4), 688–707. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v13i4.1411 | Focus groups with 42 first-generation Muslim immigrants (21 males and 21 females) from Pakistan, Egypt, and Morocco. |

Study the attitudes towards Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in a group of Muslim immigrants. | Intimate partner violence, attitudes towards intimate partner violence | Interpretation of violence as a norm and as the act of spousal care normalizes DV. Female respect toward men regardless of suffered DV. The impact of social isolation on refugee women. |

The older generation women’s in-laws) leads the decision-making and action items for couples in case of DV. | Culturally normed male dominance and role in protecting females. DV is normalized as a tool for social control over women. Divorce is not acceptable. |

N/A |

| 6 | Holtmann, C. (2016). Christian and Muslim immigrant women in the Canadian Maritimes: Considering their strengths and vulnerabilities in responding to domestic violence. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses, 45(3), 397–414 https://doi.org/10.1177/0008429816643115 |

Semi-structured interview and focus group in Canada 89 Christian and Muslim immigrant women from 27 countries of origin. | Aims to assess the strengths and vulnerabilities of Muslim migrant women in the Canadian social context. | Domestic violence, the intersection of attitudes and practices in countries of origin with the Canadian social context | Post resettlement changes in gender roles is a positive asset for women. While all participants in this study disapproved of violence they also believe that women are do their best to keep the family together. |

Participants were highly aware of the services available in the host country. Women used new networks and social support as safe spaces to discuss their DV issues and get support. |

Bonding with international families increased women’s awareness and changed their perspectives about gender roles and controlling power. Both Christian and Muslim families expect the wives to keep the family together and cope with their marital issues. |

Public service providers and religious and ethnic leaders should be aware of shifting gender roles and social status post-migration, which increases the conflict between partners. Need to increase knowledge of religious diversity for service providers. Women can be the best allies to support each other. |

| 7 | Wachter, K., Cook Heffron, L., Dalpe, J., & Spitz, A. (2021). "Where Is the Women's Center Here?": The Role of Information in Refugee Women's Help Seeking for Intimate Partner Violence in a Resettlement Context. Violence against women, 27(12-13), 2355–2376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220971364 | Semi-structured interviews with 35 refugee women in the US. |

Examined factors that hinder help-seeking for intimate partner violence (IPV) among women who resettled to the United States as refugees. | Intimate partner violence, factors that hinder help-seeking behaviors | Women believe that they should be silent in the case of abuse to respect cultural norms. Women do not have the power to verbalize the DV situation. | Back in their country, women would go to elder community members for support. In the host country, women reported a lack of knowledge about resources and a lack of ability to access them. Language barriers and financial instability are major reasons for women not to seek help even when they know of services. | The community is not supportive of women in the case of DV. Anticipation of community and family reactions prevent women from taking any action. | Network-oriented interventions: Create an ongoing system of connection support and communication with refugee women. |

| 8 | Kulwicki A., Aswad B., Carmona T., Ballout S. (2010). Barriers in the utilization of domestic violence services among Arab immigrant women: Perceptions of professional, service providers and community leaders. Journal of Family Violence, 25(8), 727–735. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-010-9330-8 | Focus groups with 65 Arab-American religious and community leaders, health and human service providers, legal and law enforcement. |

Explored the role of personal resources, family, religion, culture, and social support systems in the utilization of DV services by Arab immigrants. | Domestic violence, the role of personal and social support in the utilization of help-seeking resources and behaviors | Patriarchal and patrilineal cultures may lead to women’s acceptance of DV and shame of seeking help when abused. Negative perspective toward DV resources as these, in the long run will disturb family structure. |

Women may not seek help because of a lack of awareness about services, a complicated access path to resource, fear of lack of confidentiality in community-based services or support, immigration status, and financial instability. |

Health care providers not properly trained in DV screening have cultural gaps and language barriers. Family is the only support system that women utilize. Family and culture push women to return to abusive relationships. Religious leaders are not trained in DV and cannot provide appropriate support. | There is a need for multidisciplinary interventions. Healthcare providers and law enforcement need cultural competency training. Increase awareness and facilitate utilization of services. Training at every level, including religious leaders, lawyers, healthcare providers, on women’s rights and family structure. |

| 9 | Balice G, Aquino S, Baer S, et al. (2019). A review of barriers to treating domestic violence for Middle Eastern women living in the United States. Psychol Cogn Sci Open J.; 5(1): 30-36. http://doi.org/10.17140/PCSOJ-5-146 | Literature review (32 articles) | Examined literature that addresses DV and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Middle Eastern women living in the United States. | Domestic violence, barriers that limit help-seeking behaviors and services | Women’s patriarchal values impact their views on marital relationships and DV. DV is kept as a private family matter because of family reputation, cultural expectations, religious values, and financial dependence on husbands. Unemployment and living in rural areas may lead to more acceptance of DV. |

Help-seeking of DV services decreases in women with higher enculturation who count on help from family and friends. They may not seek mental health support because of fear of becoming stigmatized and isolated by the community. | DV is normalized in the community and regarded as a family private matter of no great significance for the community at large. |

Mental health providers and social workers should learn more about Arab family structure, patriarchal values, and stigma about mental health and how these factors impact normalization of DV and help-seeking behaviors. |

| 10 | Kulwicki, A. D., & Miller, J. (1999). Domestic violence in the Arab American population: transforming environmental conditions through community education. Issues in mental health nursing, 20(3), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/016128499248619 |

Quantitative study, Structured survey collection in-person interviews with 202 Arab American (162 female and 40 male) immigrants followed by community-based intervention. |

Assessed and provided community interventions for DV victims in the Arab American immigrant population in the United States. | Domestic violence, resources for domestic violence, barriers that limit help-seeking behaviors | Among the study participants, 58% of women and 59% of the men approved husband slapping a wife in an argument. The participants reported a high percentage of belief in men controlling women. | After the study interventions, more women reported taking action and seeking help either through community centers or outside resources. | The community became more supportive of the DV survivors after interventions. | There is a need for culturally and linguistically competent programs to increase DV awareness and prevention. |

| 11 | Abdel Meguid, M. B. (2006). Measuring Arab immigrant women's definition of marital violence: creating and validating an instrument for use in social work practice OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1148507126 | Quantitative study, structured paper survey collection from 224 Arab-Muslim immigrant women in the US | Investigated how Arab-Muslim immigrant women define IPV and help-seeking sources and barriers to access help outside the family. | Intimate partner violence, help-seeking behaviors and barriers to help-seeking behaviors | On emotional abuse, women reported men making fun of their wives in front of others or calling them names. On physical abuse, women agree on the definition abuse. Actions like forced sex or refusing to have sex with a disobedient wife were counted as less abusive. | Family members as the first source of help-seeking, followed by friends and then the Imam, and last to get help from formal authorities and shelters. The longer women stayed in the US, the less they used friends as resources increasingly relying on other resources. | Islamic and cultural beliefs have a role on women’s perspectives and attitudes toward men being controlling or men using a second marriage as abuse. | Arab Muslim women’s help-seeking process differs from Western women’s and have specific characteristics. Providers of professional service should educate themselves about different backgrounds and cultural perspectives. There is also a need to increase the diversity of workforce by training Muslim social workers. |

| 12 | Pottie, K., Dahal, G., Georgiades, K., Premji, K., & Hassan, G. (2015). Do First Generation Immigrant Adolescents Face Higher Rates of Bullying, Violence and Suicidal Behaviours Than Do Third Generation and Native Born?. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 17(5), 1557–1566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0108-6 | A systematic review of 18 studies on first-generation immigrant adolescents’ versus later-generation and native-born counterparts. |

Examined comparatively the likelihood of experiencing bullying, violence, and suicidal behaviors to identify factors that may underlie these risks. | Various forms of violence, risk factors for violence | Identified only one study in our review documenting increased risk of sexual violence among specific subpopulations of immigrant adolescents. |

N/A | When both cultural environments, family cultural of origin and host culture pro-mote conflicting values, the result may be increased intergenerational cultural dissonance, family conflict and increased risk for violence. |

Examined the challenges experienced by immigrant adolescents and their families, as well as the mediating and mitigating factors associated with these challenges. |

| 13 | Aboulhassan S, Brumley KM. Carrying the Burden of a Culture: Bargaining with Patriarchy and the Gendered Reputation of Arab American Women. Journal of Family Issues. 2019;40(5):637-661. http://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18821403 | Semi-structured interviews with 20 second-generation Arab-American women in the United States |

Explored the attitudes and beliefs of Arab American women about IPV. | Intimate partner violence, cultural expectations and attitudes around intimate partner violence | Culture plays both negative and positive roles in shaping women’s perspectives about themselves and about DV. Internalized beliefs on gender roles highly impact women’s perspectives. Pushing, shoving, grabbing, and slapping were identified as violent and unacceptable but, in a larger cultural context, were seen as permissible. |

Reputation is a social reality that may impact women’s decision-making. Stigma about divorce may also impact decision-making. Financial burden and immigration issues. |

Culture defines how families look at the DV. Arab culture decreases the severity and importance of violence and ignores some types of mental and emotional abuse. The community does not encourage other women to support DV victims. Friends and families are advised not to destroy family structure. | Discussed the women’s strength as empowering characteristics, women did not describe Arab women as victims but as strong supportive member of the family that holds the family together. Ethnic identity should be considered in addressing DV. Future research on how Aram American women see DV within the American context, how their marginalized position will impact their perspectives, and how much acculturation would increase the utilization of DV services |

| 14 | Karin Wachter, Jessica Dalpe, Laurie Cook Heffron, Conceptualizations of Domestic Violence–Related Needs among Women Who Resettled to the United States as Refugees, Social Work Research, Volume 43, Issue 4, December 2019, Pages 207–219, https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svz008 | In-depth interviews and focus groups with 35 refugee women and service providers in the US |

Investigated the DV-related needs of refugee women resettled in the United States | Intimate partner violence, needs related to intimate partner violence | Women believed DV had adverse impacts on their physical and mental well-being including PTSD, feelings of worthlessness and failure as women and wives. Most were anxious about their financial stability. | Women who left abusive husbands reported peace and overall improvement in physical and mental health. Some women decided to talk about DV with people whom they trusted and hoped they can tell them what action to take. | The community may pressure women to remarry after separation from their abusive partner. Survivors might prefer not to separate from their spouses as they worry about how the community will treat them if they divorce, and they also fear financial challenges. |

The study highlighted the post-resettlement structural barriers that impact women’s decision-making and the need for community-based support and service providers to respond to women’s needs for income and safety. |

| 15 | Tlapek, S. M., Monk, J. K., & White, C. (2020). Relational Upheaval During Refugee Resettlement: Service Provider Perspectives. Family Relations, 69(4), 756-769. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12468 | 7 Focus group with refugee women and semi-structured interviews with service providers |

Explored intimate relationships and service provider responses during the resettlement transition in the United States | Intimate relationship challenges, impact of resettlement on relational lives and attitudes | New gender roles can increase relational confrontations. Refugee women may stand up to their partners and ask for shared decision-making and no longer tolerate inadequate pre- resettlement gender norms. | Women are conflicted about services and rights available to them and what action they should take. Most women do not share their DV or relationship challenges with providers, only with trusted family or friends. Males usually show resistance to new gender role norms in the new country. |

N/A | Providers should be aware of the stressors and risks in refugee partners’ relationships and get training ways to improve the safety, health, and well-being of refugees. |

| 16 | Shalabi, D., Mitchell, S. & Andersson, N. Review of Gender Violence Among Arab Immigrants in Canada: Key Issues for Prevention Efforts. J Fam Viol 30, 817–825 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9718-6 | A literature review on gender violence among Arab immigrants in Canada |

Examined ways to reduce gender violence while recognizing resilience, family hierarchy, and the value of maintaining a family as protective factors in prevention programming. | Gender violence, reducing instances of gender violence | Victimized women may lack an understanding of DV and have a self-blame perspective. Religious interpretations may also increase the women’s self-blame culture. | Financial dependence and a lack of knowledge about available resources may impact women’s response to DV. Wives who held traditional beliefs and attitudes towards DV were less likely to use services. Also, immigrant women without knowledge about the world outside their home would be even more dependent on their spouses and less trusting of service workers in public agencies. |

Arab communities live collectively; family hierarchy dictates relationships and individual agency. Despite incidents of abuse, keeping a family is seen as essential to meet social expectations. Police may see DV in the Arab community as a cultural issue and avoid it as a post-resettlement problem. |

Collaboration among the various stakeholders in the Arab community is essential in designing more solid programs that address the issue of gender-based violence from different angles. This includes involving community leaders, elders of the community, religious leaders, and community organizations that understand the various aspects of the Arab culture. |

| 17 | Mojahed, A., Alaidarous, N., Shabta, H., Hegewald, J., & Garthus-Niegel, S. (2020). Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the Arab Countries: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020953099 | A systematic review. Female participants (age ≥13) in heterosexual relationships, estimates of potential risk factors of IPV, and IPV as a primary outcome | Examined the risk factors according to the integrative ecological theoretical framework for IPV for women living in the Arab countries | Intimate partner violence, risk factors for intimate partner violence | 50% of Jordanian women believed that men have the right to physically hurt and sexually abandon a rebellious wife. 50% of Palestinian women agreed that wives are responsible for the violence conducted against them. 80% of the surveyed Egyptian women said that physical IPV against females is justified, especially if they refused sexual interactions with their husbands, but also if the women interfere with husbands’ social life or if they talk or complain too much. |

N/A | A patriarchal hegemony is deeply ingrained into many Arab societies and shaped by social norms and cultural beliefs about traditional gender roles. | The sociocultural complexity of IPV requires preventive measures more structural and situational rather than individualistic only, where the focus of change would be on the behavior of individuals, as well as the real ecological and contextual structure of IPV. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).