Submitted:

30 October 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. General aspects

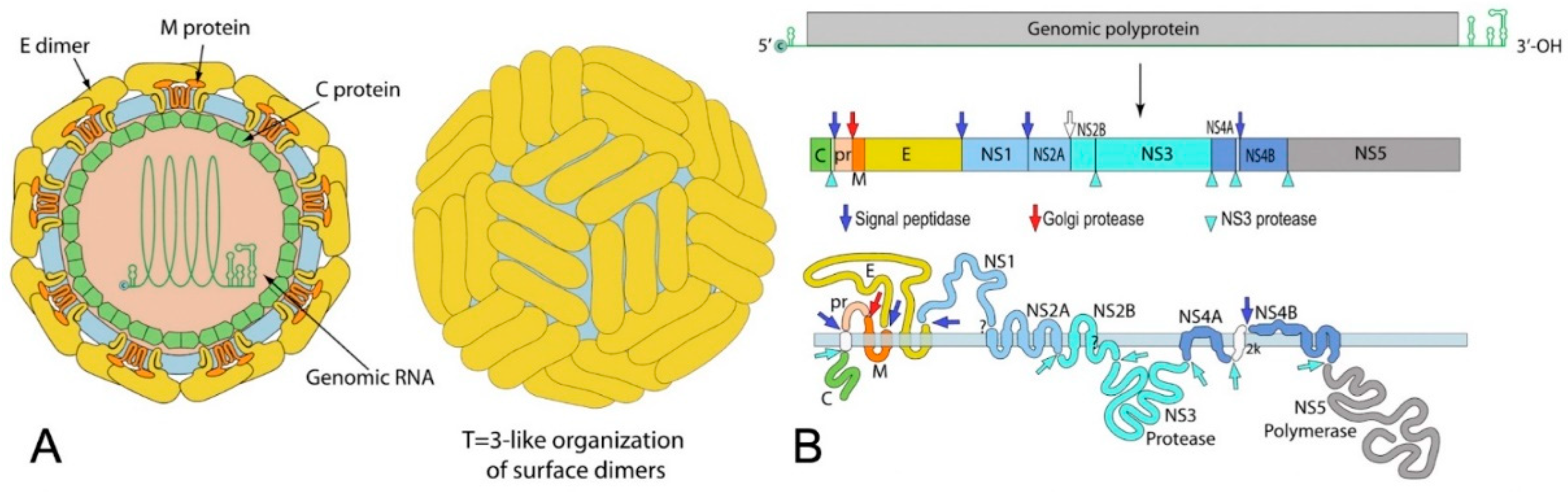

2.1. Virological features:

2.2. Transmission:

2.3. Diagnosis:

3. Ocular complications of Flaviviruses

3.1. Dengue Fever (DF)

3.1.1. Epidemiology

3.1.2. Systemic manifestations

3.1.3. Ocular manifestations

3.1.4. Diagnosis

3.1.5. Treatment and prognosis

3.2. West Nile virus infection (WNV):

3.2.1. Epidemiology

3.2.2. Systemic manifestations:

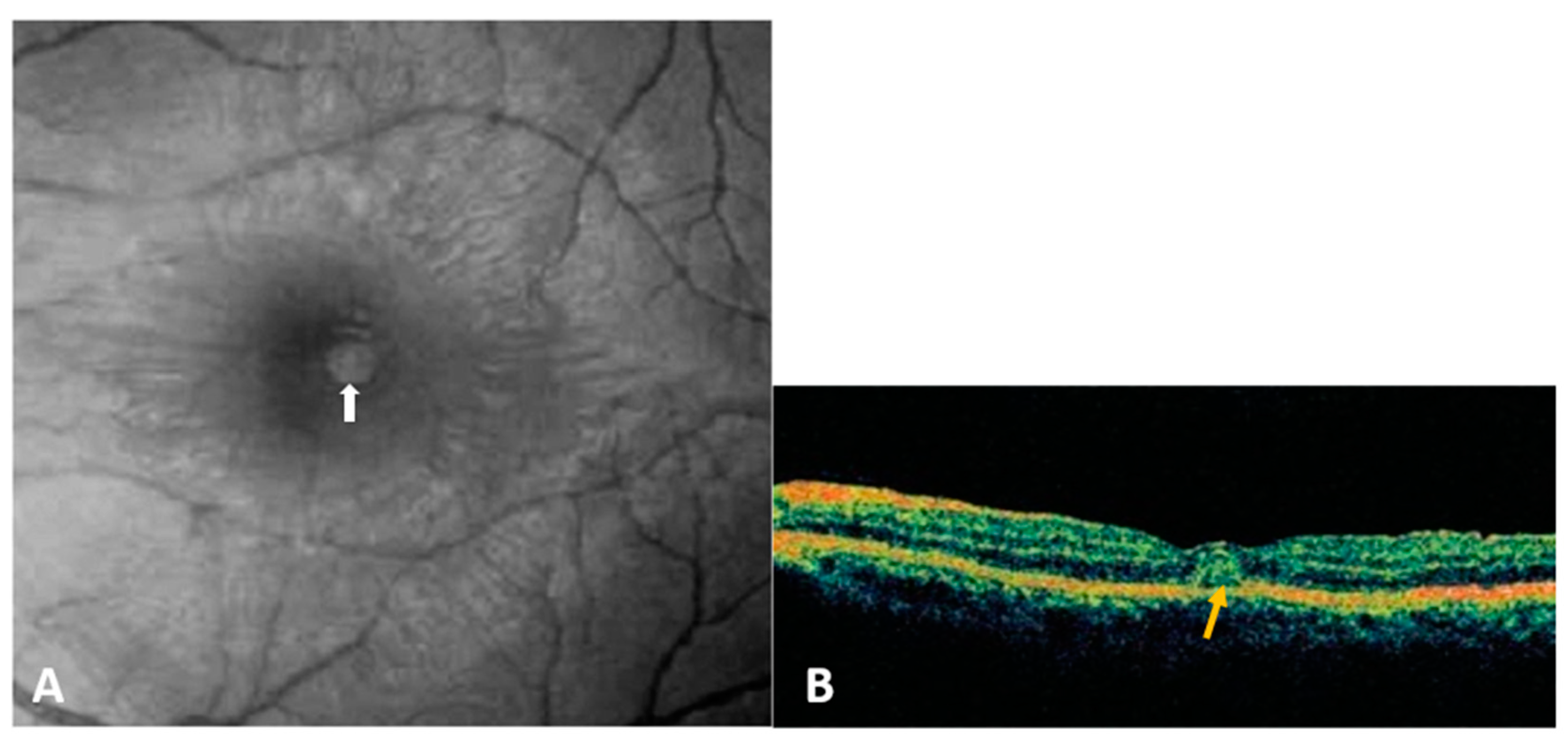

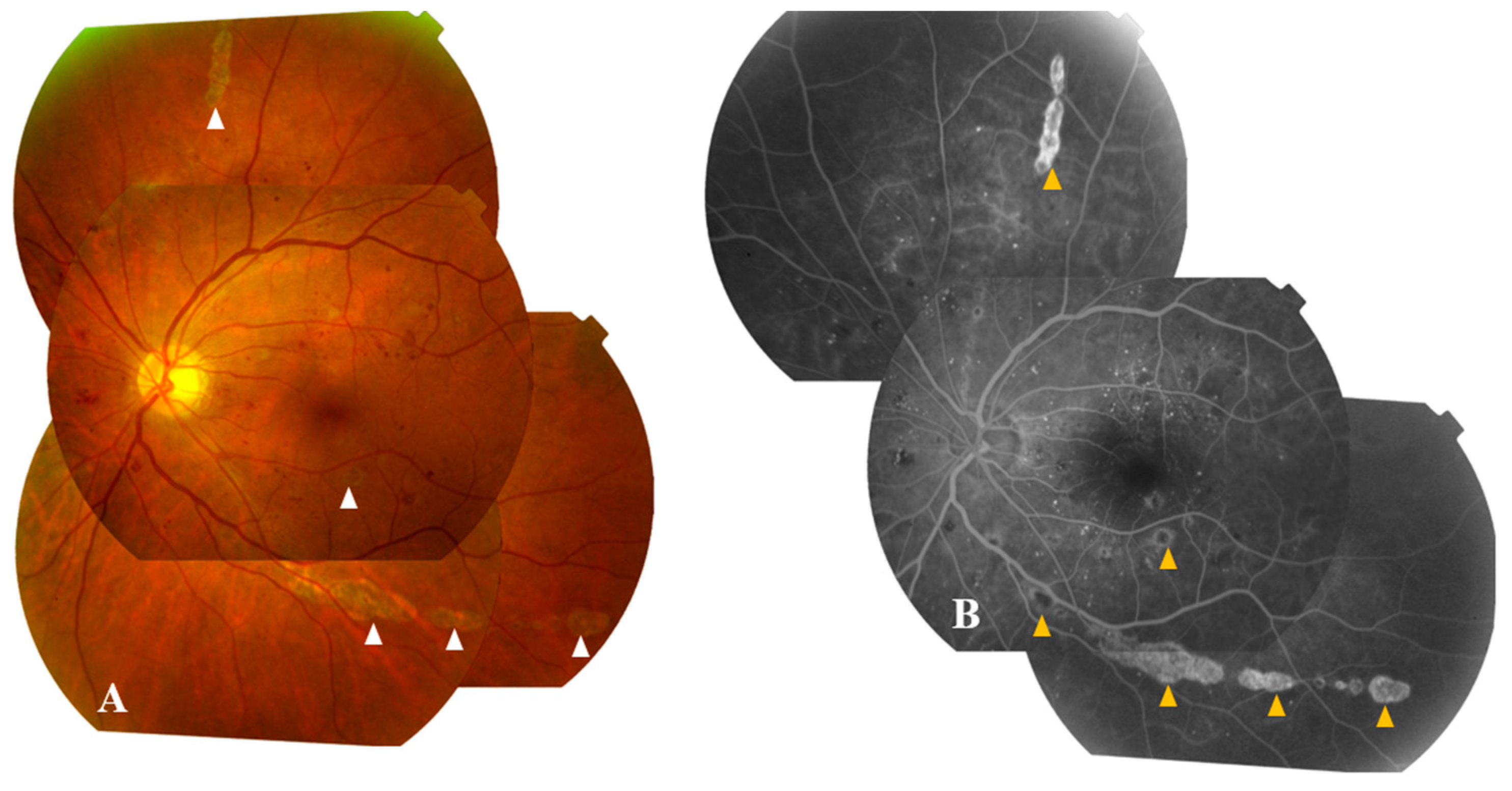

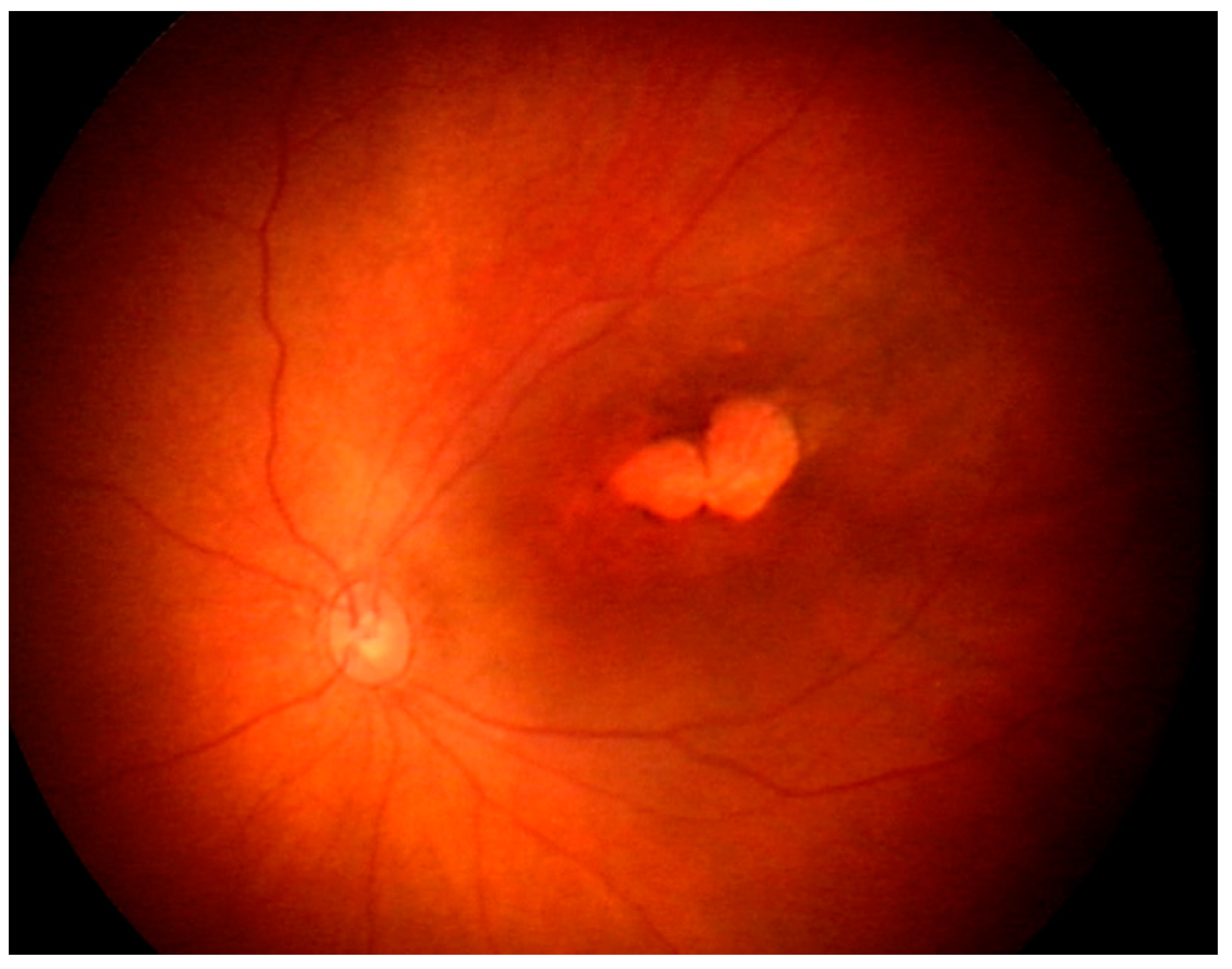

3.2.3. Ocular manifestations:

3.2.4. Diagnosis:

3.2.5. Treatment and prognosis

3.3. Yellow fever virus:

3.3.1. Epidemiology

3.3.2. Systemic manifestations:

3.3.3. Ocular manifestations:

3.3.4. Diagnosis:

3.3.5. Treatment and prognosis

3.4. Zika Virus

3.4.1. Epidemiology

3.4.2. Systemic manifestations

3.4.3. Ocular manifestations:

3.4.4. Diagnosis

3.4.5. Treatment and prognosis

3.5. Japanese Encephalitis Virus

3.5.1. Epidemiology

3.5.2. Systemic manifestations

3.5.3. Ocular manifestations

3.5.4. Diagnosis

3.5.5. Treatment and prognosis

3.6. Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus

3.6.1. Epidemiology

3.6.2. Systemic manifestations

3.6.3. Ocular manifestations

3.6.4. Diagnosis

3.6.5. Treatment and prognosis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ludwig, G.V.; Iacono-Connors, L.C. Insect-Transmitted Vertebrate Viruses: Flaviviridae. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 1993, 29A, 296–309. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Garcia, M.-D.; Mazzon, M.; Jacobs, M.; Amara, A. Pathogenesis of Flavivirus Infections: Using and Abusing the Host Cell. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 318–328. [CrossRef]

- Pandit, P.S.; Doyle, M.M.; Smart, K.M.; Young, C.C.W.; Drape, G.W.; Johnson, C.K. Predicting Wildlife Reservoirs and Global Vulnerability to Zoonotic Flaviviruses. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5425. [CrossRef]

- Merle, H.; Donnio, A.; Jean-Charles, A.; Guyomarch, J.; Hage, R.; Najioullah, F.; Césaire, R.; Cabié, A. Ocular Manifestations of Emerging Arboviruses: Dengue Fever, Chikungunya, Zika Virus, West Nile Virus, and Yellow Fever. J Fr Ophtalmol 2018, 41, e235–e243. [CrossRef]

- Lucena-Neto, F.D.; Falcão, L.F.M.; Moraes, E.C. da S.; David, J.P.F.; Vieira-Junior, A. de S.; Silva, C.C.; de Sousa, J.R.; Duarte, M.I.S.; Vasconcelos, P.F. da C.; Quaresma, J.A.S. Dengue Fever Ophthalmic Manifestations: A Review and Update. Rev Med Virol 2023, 33, e2422. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Mahendradas, P.; Curi, A.; Khochtali, S.; Cunningham, E.T. Emerging Viral Infections Causing Anterior Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2019, 27, 219–228. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A.; Patel, R.; Goyal, S.; Rajaratnam, T.; Sharma, A.; Hossain, P. Ocular Manifestations of Emerging Viral Diseases. Eye (Lond) 2021, 35, 1117–1139. [CrossRef]

- Benzekri, R.; Belfort, R.; Ventura, C.V.; de Paula Freitas, B.; Maia, M.; Leite, M.; Labetoulle, M.; Rousseau, A. [Ocular manifestations of Zika virus: What we do and do not know]. J Fr Ophtalmol 2017, 40, 138–145. [CrossRef]

- Marianneau, P.; Steffan, A.M.; Royer, C.; Drouet, M.T.; Jaeck, D.; Kirn, A.; Deubel, V. Infection of Primary Cultures of Human Kupffer Cells by Dengue Virus: No Viral Progeny Synthesis, but Cytokine Production Is Evident. J Virol 1999, 73, 5201–5206. [CrossRef]

- Tassaneetrithep, B.; Burgess, T.H.; Granelli-Piperno, A.; Trumpfheller, C.; Finke, J.; Sun, W.; Eller, M.A.; Pattanapanyasat, K.; Sarasombath, S.; Birx, D.L.; et al. DC-SIGN (CD209) Mediates Dengue Virus Infection of Human Dendritic Cells. J Exp Med 2003, 197, 823–829. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, M.N.; Sukumaran, B.; Pal, U.; Agaisse, H.; Murray, J.L.; Hodge, T.W.; Fikrig, E. Rab 5 Is Required for the Cellular Entry of Dengue and West Nile Viruses. J Virol 2007, 81, 4881–4885. [CrossRef]

- Alpert, S.G.; Fergerson, J.; Noël, L.P. Intrauterine West Nile Virus: Ocular and Systemic Findings. Am J Ophthalmol 2003, 136, 733–735. [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, M.; Jernigan, D.B.; Guasch, A.; Trepka, M.J.; Blackmore, C.G.; Hellinger, W.C.; Pham, S.M.; Zaki, S.; Lanciotti, R.S.; Lance-Parker, S.E.; et al. Transmission of West Nile Virus from an Organ Donor to Four Transplant Recipients. N Engl J Med 2003, 348, 2196–220. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Intrauterine West Nile Virus Infection--New York, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002, 51, 1135–1136.

- Sbrana, E.; Tonry, J.H.; Xiao, S.-Y.; da Rosa, A.P.A.T.; Higgs, S.; Tesh, R.B. Oral Transmission of West Nile Virus in a Hamster Model. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005, 72, 325–329.

- Komar, N.; Langevin, S.; Hinten, S.; Nemeth, N.; Edwards, E.; Hettler, D.; Davis, B.; Bowen, R.; Bunning, M. Experimental Infection of North American Birds with the New York 1999 Strain of West Nile Virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2003, 9, 311–322. [CrossRef]

- Odelola, H.A.; Oduye, O.O. West Nile Virus Infection of Adult Mice by Oral Route. Arch Virol 1977, 54, 251–253. [CrossRef]

- Sabino, E.C.; Loureiro, P.; Lopes, M.E.; Capuani, L.; McClure, C.; Chowdhury, D.; Di-Lorenzo-Oliveira, C.; Oliveira, L.C.; Linnen, J.M.; Lee, T.-H.; et al. Transfusion-Transmitted Dengue and Associated Clinical Symptoms During the 2012 Epidemic in Brazil. J Infect Dis 2016, 213, 694–702. [CrossRef]

- Slavov, S.N.; Cilião-Alves, D.C.; Gonzaga, F.A.C.; Moura, D.R.; de Moura, A.C.A.M.; de Noronha, L.A.G.; Cassemiro, É.M.; Pimentel, B.M.S.; Costa, F.J.Q.; da Silva, G.A.; et al. Dengue Seroprevalence among Asymptomatic Blood Donors during an Epidemic Outbreak in Central-West Brazil. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0213793. [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, U.C.; Mathur, A.; Chandra, A.; Das, S.K.; Tandon, H.O.; Singh, U.K. Transplacental Infection with Japanese Encephalitis Virus. J Infect Dis 1980, 141, 712–715. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Melo, A.S.; Malinger, G.; Ximenes, R.; Szejnfeld, P.O.; Alves Sampaio, S.; Bispo de Filippis, A.M. Zika Virus Intrauterine Infection Causes Fetal Brain Abnormality and Microcephaly: Tip of the Iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016, 47, 6–7. [CrossRef]

- Guérin, B.; Pozzi, N. Viruses in Boar Semen: Detection and Clinical as Well as Epidemiological Consequences Regarding Disease Transmission by Artificial Insemination. Theriogenology 2005, 63, 556–572. [CrossRef]

- Paz-Bailey, G.; Rosenberg, E.S.; Doyle, K.; Munoz-Jordan, J.; Santiago, G.A.; Klein, L.; Perez-Padilla, J.; Medina, F.A.; Waterman, S.H.; Gubern, C.G.; et al. Persistence of Zika Virus in Body Fluids - Final Report. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 1234–1243. [CrossRef]

- Kuno, G. Serodiagnosis of Flaviviral Infections and Vaccinations in Humans. Adv Virus Res 2003, 61, 3–65. [CrossRef]

- Alhajj, M.; Zubair, M.; Farhana, A. Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023.

- Roberts, A.; Gandhi, S. Japanese Encephalitis Virus: A Review on Emerging Diagnostic Techniques. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2020, 25, 1875–1893. [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.G.; Gubler, D.J.; Izquierdo, A.; Martinez, E.; Halstead, S.B. Dengue Infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016, 2, 16055. [CrossRef]

- Halstead, S.B. Dengue. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2002, 15, 471–476. [CrossRef]

- Murray, N.E.A.; Quam, M.B.; Wilder-Smith, A. Epidemiology of Dengue: Past, Present and Future Prospects. Clin Epidemiol 2013, 5, 299–309. [CrossRef]

- Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control: New Edition; WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2009; ISBN 978-92-4-154787-1.

- Bhatt, S.; Gething, P.W.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Farlow, A.W.; Moyes, C.L.; Drake, J.M.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Sankoh, O.; et al. The Global Distribution and Burden of Dengue. Nature 2013, 496, 504–507. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Global Strategy for Dengue Prevention and Control 2012-2020; World Health Organization, 2012.

- Gubler, D.J. Dengue, Urbanization and Globalization: The Unholy Trinity of the 21(St) Century. Trop Med Health 2011, 39, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, H.K.; Bhai, S.; John, M.; Xavier, J. Ocular Manifestations of Dengue Fever in an East Indian Epidemic. Can J Ophthalmol 2006, 41, 741–746. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Srinivasan, R.; Setia, S.; Soundravally, R.; Pandian, D.G. Uveitis Following Dengue Fever. Eye (Lond) 2009, 23, 873–876. [CrossRef]

- Loh, B.-K.; Bacsal, K.; Chee, S.-P.; Cheng, B.C.-L.; Wong, D. Foveolitis Associated with Dengue Fever: A Case Series. Ophthalmologica 2008, 222, 317–320. [CrossRef]

- Su, D.H.-W.; Bacsal, K.; Chee, S.-P.; Flores, J.V.P.; Lim, W.-K.; Cheng, B.C.-L.; Jap, A.H.-E.; Dengue Maculopathy Study Group Prevalence of Dengue Maculopathy in Patients Hospitalized for Dengue Fever. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 1743–1747. [CrossRef]

- Chee, E.; Sims, J.L.; Jap, A.; Tan, B.H.; Oh, H.; Chee, S.-P. Comparison of Prevalence of Dengue Maculopathy during Two Epidemics with Differing Predominant Serotypes. Am J Ophthalmol 2009, 148, 910–913. [CrossRef]

- Teoh, S.C.; Chee, C.K.; Laude, A.; Goh, K.Y.; Barkham, T.; Ang, B.S.; Eye Institute Dengue-related Ophthalmic Complications Workgroup Optical Coherence Tomography Patterns as Predictors of Visual Outcome in Dengue-Related Maculopathy. Retina 2010, 30, 390–398. [CrossRef]

- Bacsal, K.E.; Chee, S.-P.; Cheng, C.-L.; Flores, J.V.P. Dengue-Associated Maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2007, 125, 501–510. [CrossRef]

- Yip, V.C.-H.; Sanjay, S.; Koh, Y.T. Ophthalmic Complications of Dengue Fever: A Systematic Review. Ophthalmol Ther 2012, 1, 2. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Aggarwal, K.; Dogra, M.; Kumar, A.; Akella, M.; Katoch, D.; Bansal, R.; Singh, R.; Gupta, V.; OCTA Study Group Dengue-Induced Inflammatory, Ischemic Foveolitis and Outer Maculopathy: A Swept-Source Imaging Evaluation. Ophthalmol Retina 2019, 3, 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Yahia, S.B.; Attia, S. Arthropod Vector-Borne Uveitis in the Developing World. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2010, 50, 125–144. [CrossRef]

- Tabbara, K. Dengue Retinochoroiditis. Ann Saudi Med 2012, 32, 530–533. [CrossRef]

- Somkijrungroj, T.; Kongwattananon, W. Ocular Manifestations of Dengue. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2019, 30, 500–505. [CrossRef]

- Dhoot, S.K. Bilateral Ciliochoroidal Effusion with Secondary Angle Closure and Myopic Shift in Dengue Fever. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2023, 31, 847–850. [CrossRef]

- Saranappa S B, S.; Sowbhagya, H.N. Panophthalmitis in Dengue Fever. Indian Pediatr 2012, 49, 760. [CrossRef]

- Arya, D.; Das, S.; Shah, G.; Gandhi, A. Panophthalmitis Associated with Scleral Necrosis in Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. Indian J Ophthalmol 2019, 67, 1775–1777. [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, S.A.; Dalugama, C. Dengue Infection: Global Importance, Immunopathology and Management. Clin Med (Lond) 2022, 22, 9–13. [CrossRef]

- Scherwitzl, I.; Mongkolsapaja, J.; Screaton, G. Recent Advances in Human Flavivirus Vaccines. Curr Opin Virol 2017, 23, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.-K.; Mathur, R.; Koh, A.; Yeoh, R.; Chee, S.-P. Ocular Manifestations of Dengue Fever. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 2057–2064. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.R.; Brault, A.C.; Nasci, R.S. West Nile Virus: Review of the Literature. JAMA 2013, 310, 308–315. [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Jampol, L.M. Systemic and Intraocular Manifestations of West Nile Virus Infection. Surv Ophthalmol 2005, 50, 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Troupin, A.; Colpitts, T.M. Overview of West Nile Virus Transmission and Epidemiology. Methods Mol Biol 2016, 1435, 15–18, doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-3670-0_2. [CrossRef]

- Zannoli, S.; Sambri, V. West Nile Virus and Usutu Virus Co-Circulation in Europe: Epidemiology and Implications. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 184. [CrossRef]

- Gyure, K.A. West Nile Virus Infections. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2009, 68, 1053–1060. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Ben Yahia, S.; Ladjimi, A.; Zeghidi, H.; Ben Romdhane, F.; Besbes, L.; Zaouali, S.; Messaoud, R. Chorioretinal Involvement in Patients with West Nile Virus Infection. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 2065–2070. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Limstrom, S.A.; Tarasewicz, D.G.; Lin, S.G. Ocular Features of West Nile Virus Infection in North America: A Study of 14 Eyes. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, 1539–1546. [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, R.R.; Prajna, L.; Arya, L.K.; Muraly, P.; Shukla, J.; Saxena, D.; Parida, M. Molecular Diagnosis and Ocular Imaging of West Nile Virus Retinitis and Neuroretinitis. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 1820–1826. [CrossRef]

- Dahal, U.; Mobarakai, N.; Sharma, D.; Pathak, B. West Nile Virus Infection and Diplopia: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Int J Gen Med 2013, 6, 369–373. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Ben Yahia, S.; Attia, S.; Zaouali, S.; Ladjimi, A.; Messaoud, R. Linear Pattern of West Nile Virus-Associated Chorioretinitis Is Related to Retinal Nerve Fibres Organization. Eye (Lond) 2007, 21, 952–955. [CrossRef]

- Learned, D.; Nudleman, E.; Robinson, J.; Chang, E.; Stec, L.; Faia, L.J.; Wolfe, J.; Williams, G.A. Multimodal Imaging of West Nile Virus Chorioretinitis. Retina 2014, 34, 2269–2274. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Ben Yahia, S.; Attia, S.; Zaouali, S.; Jelliti, B.; Jenzri, S.; Ladjimi, A.; Messaoud, R. Indocyanine Green Angiographic Features in Multifocal Chorioretinitis Associated with West Nile Virus Infection. Retina 2006, 26, 358–359. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Jelliti, B.; Jenzeri, S. Emergent Infectious Uveitis. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2009, 16, 225–238. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Kahloun, R. Ocular Manifestations of Emerging Infectious Diseases. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2013, 24, 574–580. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Kahloun, R.; Gargouri, S.; Jelliti, B.; Sellami, D.; Ben Yahia, S.; Feki, J. Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in West Nile Virus Chorioretinitis and Associated Occlusive Retinal Vasculitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2017, 48, 672–675. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, J.; Saxena, D.; Rathinam, S.; Lalitha, P.; Joseph, C.R.; Sharma, S.; Soni, M.; Rao, P.V.L.; Parida, M. Molecular Detection and Characterization of West Nile Virus Associated with Multifocal Retinitis in Patients from Southern India. Int J Infect Dis 2012, 16, e53-59. [CrossRef]

- Lazear, H.M.; Pinto, A.K.; Vogt, M.R.; Gale, M.; Diamond, M.S. Beta Interferon Controls West Nile Virus Infection and Pathogenesis in Mice. J Virol 2011, 85, 7186–7194. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nathan, D.; Gershoni-Yahalom, O.; Samina, I.; Khinich, Y.; Nur, I.; Laub, O.; Gottreich, A.; Simanov, M.; Porgador, A.; Rager-Zisman, B.; et al. Using High Titer West Nile Intravenous Immunoglobulin from Selected Israeli Donors for Treatment of West Nile Virus Infection. BMC Infect Dis 2009, 9, 18. [CrossRef]

- Gorman, M.J.; Poddar, S.; Farzan, M.; Diamond, M.S. The Interferon-Stimulated Gene Ifitm3 Restricts West Nile Virus Infection and Pathogenesis. J Virol 2016, 90, 8212–8225. [CrossRef]

- Seth, R.K.; Stoessel, K.M.; Adelman, R.A. Choroidal Neovascularization Associated with West Nile Virus Chorioretinitis. Semin Ophthalmol 2007, 22, 81–84. [CrossRef]

- Afshar, A.R.; Hariprasad, S.M.; Jampol, L.M.; Sheth, V.S. Use of Intravitreous Bevacizumab to Treat Macular Edema in West Nile Virus Chorioretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol 2012, 130, 396–398. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, G.; De Jesus Rodriguez, E.; Vila-Delgado, M.; Oliver, A.L. An Unusual Case of Unilateral Chorioretinitis and Blind Spot Enlargement Associated with Asymptomatic West Nile Virus Infection. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2020, 18, 100723. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Yahia, S.B.; Letaief, M.; Attia, S.; Kahloun, R.; Jelliti, B.; Zaouali, S.; Messaoud, R. A Prospective Evaluation of Factors Associated with Chorioretinitis in Patients with West Nile Virus Infection. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2007, 15, 435–439. [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Ben Yahia, S.; Attia, S.; Jelliti, B.; Zaouali, S.; Ladjimi, A. Severe Ischemic Maculopathy in a Patient with West Nile Virus Infection. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2006, 37, 240–242. [CrossRef]

- Monath, T.P. Yellow Fever: An Update. Lancet Infect Dis 2001, 1, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Lucey, D.; Gostin, L.O. A Yellow Fever Epidemic: A New Global Health Emergency? JAMA 2016, 315, 2661–2662. [CrossRef]

- Douam, F.; Ploss, A. Yellow Fever Virus: Knowledge Gaps Impeding the Fight Against an Old Foe. Trends Microbiol 2018, 26, 913–928. [CrossRef]

- Brandão-de-Resende, C.; Cunha, L.H.M.; Oliveira, S.L.; Pereira, L.S.; Oliveira, J.G.F.; Santos, T.A.; Vasconcelos-Santos, D.V. Characterization of Retinopathy Among Patients With Yellow Fever During 2 Outbreaks in Southeastern Brazil. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019, 137, 996–1002. [CrossRef]

- Vianello, S.; Silva de Souza, G.; Maia, M.; Belfort, R.; de Oliveira Dias, J.R. Ocular Findings in Yellow Fever Infection. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019, 137, 300–304. [CrossRef]

- Biancardi, A.L.; Moraes, H.V. de Anterior and Intermediate Uveitis Following Yellow Fever Vaccination with Fractional Dose: Case Reports. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2019, 27, 521–523. [CrossRef]

- Campos, W.R.; Cenachi, S.P.F.; Soares, M.S.; Gonçalves, P.F.; Vasconcelos-Santos, D.V. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada-like Disease Following Yellow Fever Vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2021, 29, 124–127. [CrossRef]

- Vannice, K.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Hombach, J. Fractional-Dose Yellow Fever Vaccination - Advancing the Evidence Base. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 603–605. [CrossRef]

- Yellow Fever Vaccine. In Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®); National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: Bethesda (MD), 2006.

- Plourde, A.R.; Bloch, E.M. A Literature Review of Zika Virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22, 1185–1192. [CrossRef]

- Musso, D.; Roche, C.; Robin, E.; Nhan, T.; Teissier, A.; Cao-Lormeau, V.-M. Potential Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2015, 21, 359–361. [CrossRef]

- Musso, D.; Nhan, T.; Robin, E.; Roche, C.; Bierlaire, D.; Zisou, K.; Shan Yan, A.; Cao-Lormeau, V.M.; Broult, J. Potential for Zika Virus Transmission through Blood Transfusion Demonstrated during an Outbreak in French Polynesia, November 2013 to February 2014. Euro Surveill 2014, 19, 20761. [CrossRef]

- Dick, G.W.A.; Kitchen, S.F.; Haddow, A.J. Zika Virus. I. Isolations and Serological Specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1952, 46, 509–520. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, W.K.; de França, G.V.A.; Carmo, E.H.; Duncan, B.B.; de Souza Kuchenbecker, R.; Schmidt, M.I. Infection-Related Microcephaly after the 2015 and 2016 Zika Virus Outbreaks in Brazil: A Surveillance-Based Analysis. Lancet 2017, 390, 861–870. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.R.; Chen, T.-H.; Hancock, W.T.; Powers, A.M.; Kool, J.L.; Lanciotti, R.S.; Pretrick, M.; Marfel, M.; Holzbauer, S.; Dubray, C.; et al. Zika Virus Outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med 2009, 360, 2536–2543. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, L.S.; Barreras, P.; Pardo, C.A. Zika Virus-Associated Neurological Disease in the Adult: Guillain-Barré Syndrome, Encephalitis, and Myelitis. Semin Reprod Med 2016, 34, 273–279. [CrossRef]

- Leonhard, S.E.; Bresani-Salvi, C.C.; Lyra Batista, J.D.; Cunha, S.; Jacobs, B.C.; Brito Ferreira, M.L.; P Militão de Albuquerque, M. de F. Guillain-Barré Syndrome Related to Zika Virus Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Clinical and Electrophysiological Phenotype. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008264. [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.A.; Staples, J.E.; Dobyns, W.B.; Pessoa, A.; Ventura, C.V.; Fonseca, E.B. da; Ribeiro, E.M.; Ventura, L.O.; Neto, N.N.; Arena, J.F.; et al. Characterizing the Pattern of Anomalies in Congenital Zika Syndrome for Pediatric Clinicians. JAMA Pediatr 2017, 171, 288–295. [CrossRef]

- Troumani, Y.; Touhami, S.; Jackson, T.L.; Ventura, C.V.; Stanescu-Segall, D.M.; Errera, M.-H.; Rousset, D.; Bodaghi, B.; Cartry, G.; David, T.; et al. Association of Anterior Uveitis With Acute Zika Virus Infection in Adults. JAMA Ophthalmol 2021, 139, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Parke, D.W.; Almeida, D.R.P.; Albini, T.A.; Ventura, C.V.; Berrocal, A.M.; Mittra, R.A. Serologically Confirmed Zika-Related Unilateral Acute Maculopathy in an Adult. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2432–2433. [CrossRef]

- Kodati, S.; Palmore, T.N.; Spellman, F.A.; Cunningham, D.; Weistrop, B.; Sen, H.N. Bilateral Posterior Uveitis Associated with Zika Virus Infection. Lancet 2017, 389, 125–126. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, C.V.; Ventura, L.O. Ophthalmologic Manifestations Associated With Zika Virus Infection. Pediatrics 2018, 141, S161–S166. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, C.V.; Maia, M.; Travassos, S.B.; Martins, T.T.; Patriota, F.; Nunes, M.E.; Agra, C.; Torres, V.L.; van der Linden, V.; Ramos, R.C.; et al. Risk Factors Associated With the Ophthalmoscopic Findings Identified in Infants With Presumed Zika Virus Congenital Infection. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016, 134, 912–918. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, C.V.; Maia, M.; Bravo-Filho, V.; Góis, A.L.; Belfort, R. Zika Virus in Brazil and Macular Atrophy in a Child with Microcephaly. Lancet 2016, 387, 228. [CrossRef]

- Marquezan, M.C.; Ventura, C.V.; Sheffield, J.S.; Golden, W.C.; Omiadze, R.; Belfort, R.; May, W. Ocular Effects of Zika Virus-a Review. Surv Ophthalmol 2018, 63, 166–173. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, C.V.; Ventura, L.O.; Bravo-Filho, V.; Martins, T.T.; Berrocal, A.M.; Gois, A.L.; de Oliveira Dias, J.R.; Araújo, L.; Escarião, P.; van der Linden, V.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography of Retinal Lesions in Infants With Congenital Zika Syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016, 134, 1420–1427. [CrossRef]

- Zin, A.A.; Tsui, I.; Rossetto, J.; Vasconcelos, Z.; Adachi, K.; Valderramos, S.; Halai, U.-A.; Pone, M.V. da S.; Pone, S.M.; Silveira Filho, J.C.B.; et al. Screening Criteria for Ophthalmic Manifestations of Congenital Zika Virus Infection. JAMA Pediatr 2017, 171, 847–854. [CrossRef]

- de Paula Freitas, B.; de Oliveira Dias, J.R.; Prazeres, J.; Sacramento, G.A.; Ko, A.I.; Maia, M.; Belfort, R. Ocular Findings in Infants With Microcephaly Associated With Presumed Zika Virus Congenital Infection in Salvador, Brazil. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016, 134, 529–535. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, G.C.; Macedo Pereira, C.M.; Toledo de Paula, C.H.; de Souza Haueisen Barbosa, P.; Machado de Souza, D.; Coelho, L.M. Corneal Ectasia and High Ametropia in an Infant with Microcephaly Associated with Presumed Zika Virus Congenital Infection: New Ocular Findings. J AAPOS 2019, 23, 354–356. [CrossRef]

- Yepez, J.B.; Murati, F.A.; Pettito, M.; Peñaranda, C.F.; de Yepez, J.; Maestre, G.; Arevalo, J.F.; Johns Hopkins Zika Center Ophthalmic Manifestations of Congenital Zika Syndrome in Colombia and Venezuela. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017, 135, 440–445. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.P.; Parra Saad, E.; Ospina Martinez, M.; Corchuelo, S.; Mercado Reyes, M.; Herrera, M.J.; Parra Saavedra, M.; Rico, A.; Fernandez, A.M.; Lee, R.K.; et al. Ocular Histopathologic Features of Congenital Zika Syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017, 135, 1163–1169. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Oo, H.H.; Balne, P.K.; Ng, L.; Tong, L.; Leo, Y.S. Zika Virus and the Eye. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2018, 26, 654–659. [CrossRef]

- Gourinat, A.-C.; O’Connor, O.; Calvez, E.; Goarant, C.; Dupont-Rouzeyrol, M. Detection of Zika Virus in Urine. Emerg Infect Dis 2015, 21, 84–86. [CrossRef]

- Rabe, I.B.; Staples, J.E.; Villanueva, J.; Hummel, K.B.; Johnson, J.A.; Rose, L.; MTS; Hills, S.; Wasley, A.; Fischer, M.; et al. Interim Guidance for Interpretation of Zika Virus Antibody Test Results. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016, 65, 543–546. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ling, L.; Zhang, Z.; Marin-Lopez, A. Current Advances in Zika Vaccine Development. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 1816. [CrossRef]

- Statement on the Medical Care Provided for and the Monitoring of New-Borns and Infants Having Been Exposed to the Zika Virus in Utero or Present Https://Www.Hcsp.Fr/Explore.Cgi/AvisRapportsDomaine?Clefr=675; Haut conseil de la sante publique, 2017.

- Adebanjo, T.; Godfred-Cato, S.; Viens, L.; Fischer, M.; Staples, J.E.; Kuhnert-Tallman, W.; Walke, H.; Oduyebo, T.; Polen, K.; Peacock, G.; et al. Update: Interim Guidance for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management of Infants with Possible Congenital Zika Virus Infection - United States, October 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017, 66, 1089–1099. [CrossRef]

- Yakob, L.; Hu, W.; Frentiu, F.D.; Gyawali, N.; Hugo, L.E.; Johnson, B.; Lau, C.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Magalhaes, R.S.; Devine, G. Japanese Encephalitis Emergence in Australia: The Potential Population at Risk. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 76, 335–337. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, T. Control of Japanese Encephalitis--within Our Grasp? N Engl J Med 2006, 355, 869–871. [CrossRef]

- Buescher, E.L.; Scherer, W.F.; Rosenberg, M.Z.; Gresser, I.; Hardy, J.L.; Bullock, H.R. Ecologic Studies of Japanese Encephalitis Virus in Japan. II. Mosquito Infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1959, 8, 651–664. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Lindsey, N.; Staples, J.E.; Hills, S.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Japanese Encephalitis Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2010, 59, 1–27.

- Hills, S.L.; Netravathi, M.; Solomon, T. Japanese Encephalitis among Adults: A Review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2023, 108, 860–864. [CrossRef]

- Turtle, L.; Solomon, T. Japanese Encephalitis - the Prospects for New Treatments. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14, 298–313. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, T.; Dung, N.M.; Kneen, R.; Gainsborough, M.; Vaughn, D.W.; Khanh, V.T. Japanese Encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000, 68, 405–415. [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.-T.; Chu, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C. Ischaemic Maculopathy in Japanese Encephalitis. Eye (Lond) 2006, 20, 1439–1441. [CrossRef]

- Van, K.; Korman, T.M.; Nicholson, S.; Troutbeck, R.; Lister, D.M.; Woolley, I. Case Report: Japanese Encephalitis Associated with Chorioretinitis after Short-Term Travel to Bali, Indonesia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020, 103, 1691–1693. [CrossRef]

- Chanama, S.; Sukprasert, W.; Sa-ngasang, A.; A-nuegoonpipat, A.; Sangkitporn, S.; Kurane, I.; Anantapreecha, S. Detection of Japanese Encephalitis (JE) Virus-Specific IgM in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Serum Samples from JE Patients. Jpn J Infect Dis 2005, 58, 294–296.

- Swami, R.; Ratho, R.K.; Mishra, B.; Singh, M.P. Usefulness of RT-PCR for the Diagnosis of Japanese Encephalitis in Clinical Samples. Scand J Infect Dis 2008, 40, 815–820. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Taraphdar, D.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Chatterjee, S. Serological and Molecular Diagnosis of Japanese Encephalitis Reveals an Increasing Public Health Problem in the State of West Bengal, India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012, 106, 15–19. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Datta, S.; Pathak, B.K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K.; Chatterjee, S. Japanese Encephalitis Associated Acute Encephalitis Syndrome Cases in West Bengal, India: A Sero-Molecular Evaluation in Relation to Clinico-Pathological Spectrum. J Med Virol 2015, 87, 1258–1267. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, A. Control of Japanese Encephalitis in Japan: Immunization of Humans and Animals, and Vector Control. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2002, 267, 139–152. [CrossRef]

- Erlanger, T.E.; Weiss, S.; Keiser, J.; Utzinger, J.; Wiedenmayer, K. Past, Present, and Future of Japanese Encephalitis. Emerg Infect Dis 2009, 15, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.Z.; Jabbar, B.; Ahmed, N.; Rehman, A.; Nasir, H.; Nadeem, S.; Jabbar, I.; Rahman, Z.U.; Azam, S. Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Control of a Tick-Borne Disease- Kyasanur Forest Disease: Current Status and Future Directions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 8, 149. [CrossRef]

- Work, T.H.; Trapido, H.; Murthy, D.P.N.; Rao, R.L.; Bhatt, P.N.; Kulkarni, K.G. Kyasanur Forest Disease. III. A Preliminary Report on the Nature of the Infection and Clinical Manifestations in Human Beings. Indian J Med Sci 1957, 11, 619–645.

- Chakraborty, S.; Andrade, F.C.D.; Ghosh, S.; Uelmen, J.; Ruiz, M.O. Historical Expansion of Kyasanur Forest Disease in India From 1957 to 2017: A Retrospective Analysis. Geohealth 2019, 3, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Sadanandane, C.; Gokhale, M.D.; Elango, A.; Yadav, P.; Mourya, D.T.; Jambulingam, P. Prevalence and Spatial Distribution of Ixodid Tick Populations in the Forest Fringes of Western Ghats Reported with Human Cases of Kyasanur Forest Disease and Monkey Deaths in South India. Exp Appl Acarol 2018, 75, 135–142. [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, P. Kyasanur Forest Disease: An Epidemiological View in India. Rev Med Virol 2006, 16, 151–165. [CrossRef]

- Ocular Manifestations of Kyasanur Forest Disease (a Clinical Study). Indian J Ophthalmol 1983, 31, 700–702.

- Mourya, D.T.; Yadav, P.D.; Mehla, R.; Barde, P.V.; Yergolkar, P.N.; Kumar, S.R.P.; Thakare, J.P.; Mishra, A.C. Diagnosis of Kyasanur Forest Disease by Nested RT-PCR, Real-Time RT-PCR and IgM Capture ELISA. J Virol Methods 2012, 186, 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, S.K.; Pasi, A.; Kumar, S.; Kasabi, G.S.; Gujjarappa, P.; Shrivastava, A.; Mehendale, S.; Chauhan, L.S.; Laserson, K.F.; Murhekar, M. Kyasanur Forest Disease Outbreak and Vaccination Strategy,Shimoga District, India, 2013-2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2015, 21, 146–149. [CrossRef]

- Ogden, N.H.; Bigras-Poulin, M.; O’Callaghan, C.J.; Barker, I.K.; Lindsay, L.R.; Maarouf, A.; Smoyer-Tomic, K.E.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Charron, D. A Dynamic Population Model to Investigate Effects of Climate on Geographic Range and Seasonality of the Tick Ixodes Scapularis. Int J Parasitol 2005, 35, 375–389. [CrossRef]

- Satish, K.V.; Saranya, K.R.L.; Reddy, C.S.; Krishna, P.H.; Jha, C.S.; Rao, P.V.V.P. Geospatial Assessment and Monitoring of Historical Forest Cover Changes (1920-2012) in Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, Western Ghats, India. Environ Monit Assess 2014, 186, 8125–8140. [CrossRef]

- Hulo, C.; de Castro, E.; Masson, P.; Bougueleret, L.; Bairoch, A.; Xenarios, I.; Le Mercier, P. ViralZone: A Knowledge Resource to Understand Virus Diversity. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, D576-582. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).