Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

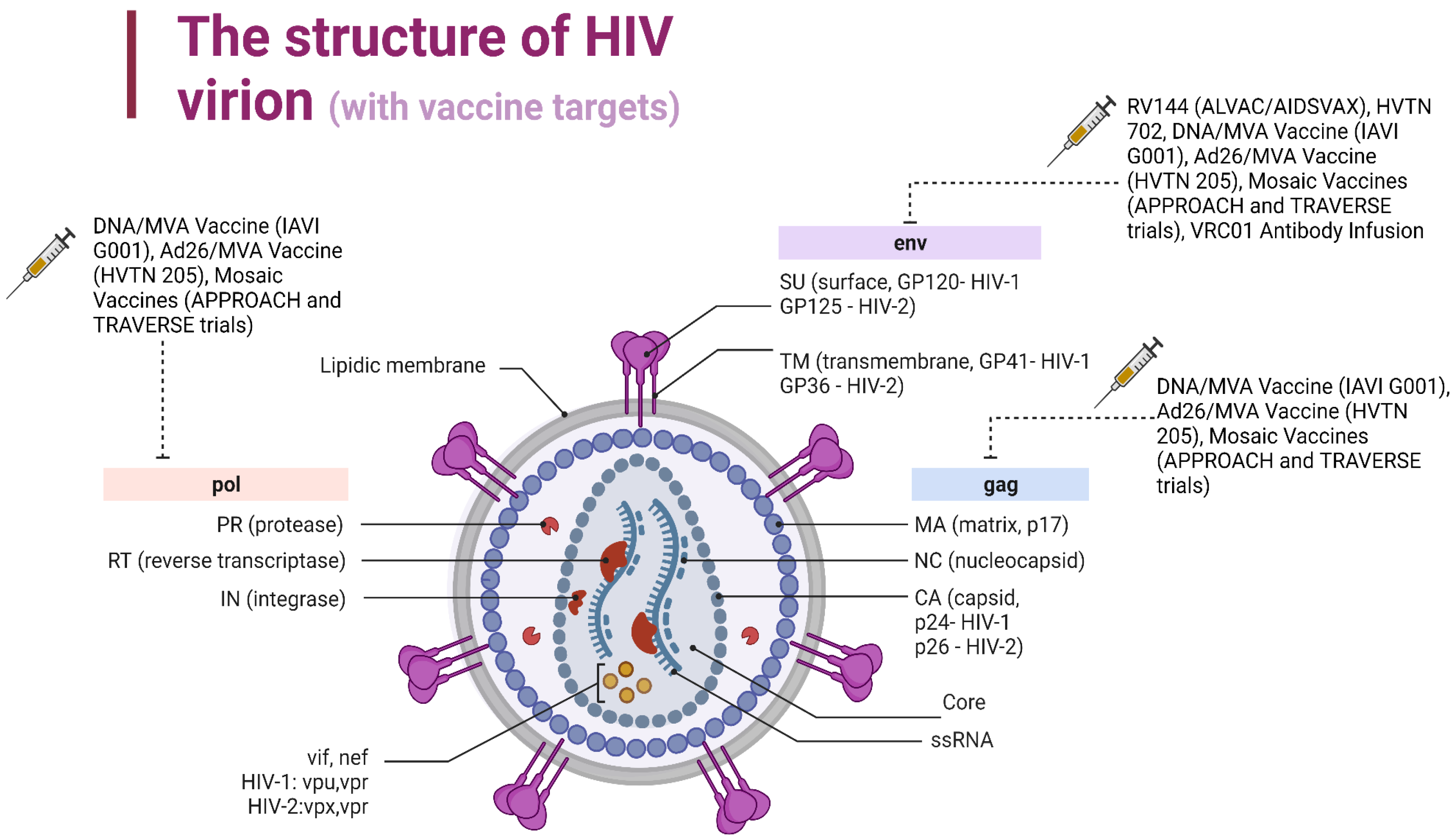

2. Structure, Protein Functions, and the Infectious Mechanisms of HIV

2.1. HIV-1 Gene-Encoded Proteins and Their Functions

2.2. Mechanism of Infection

3. Vaccines Based on the Induction of Neutralizing Antibodies

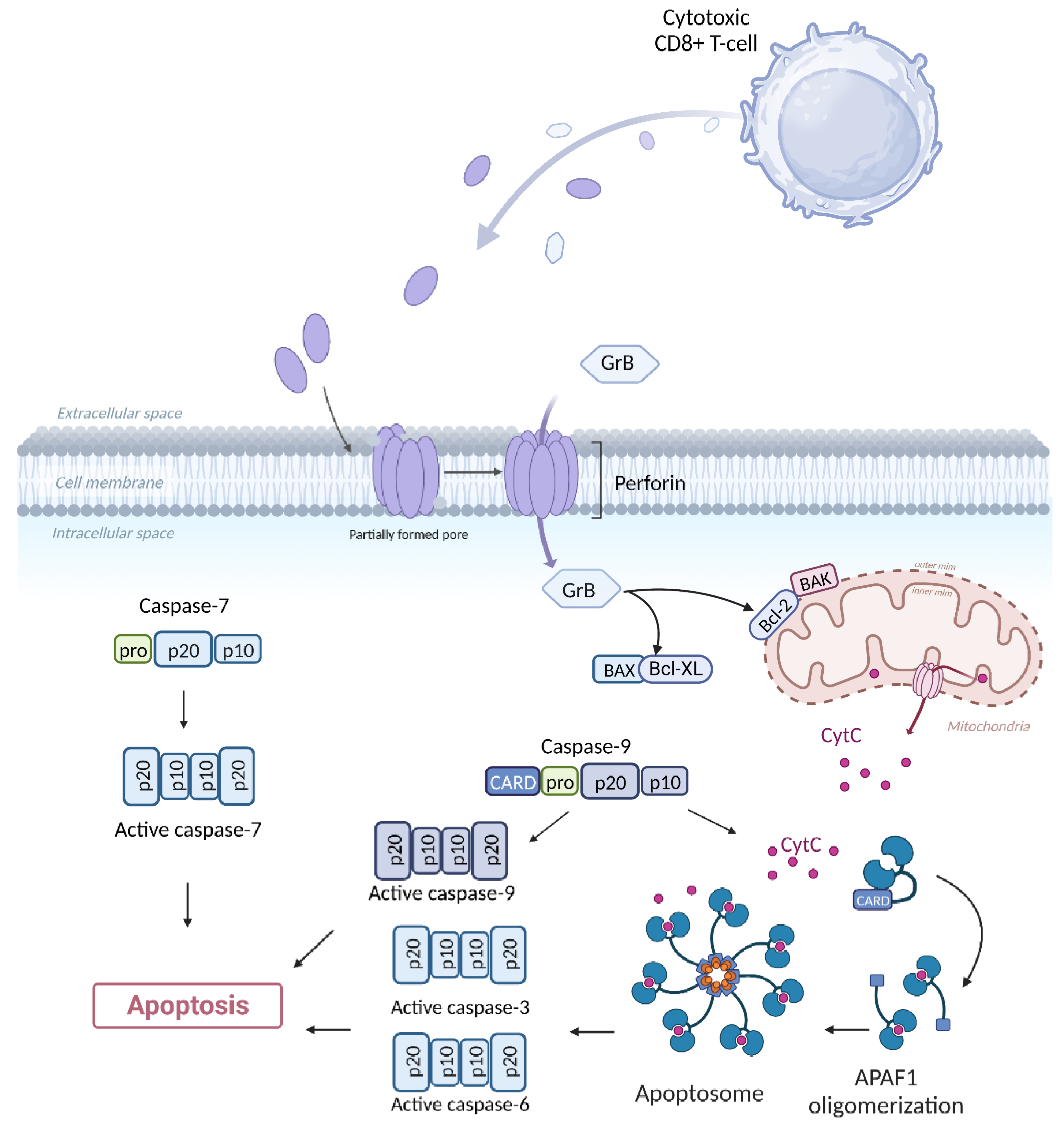

3.1. Direct Cytotoxicity

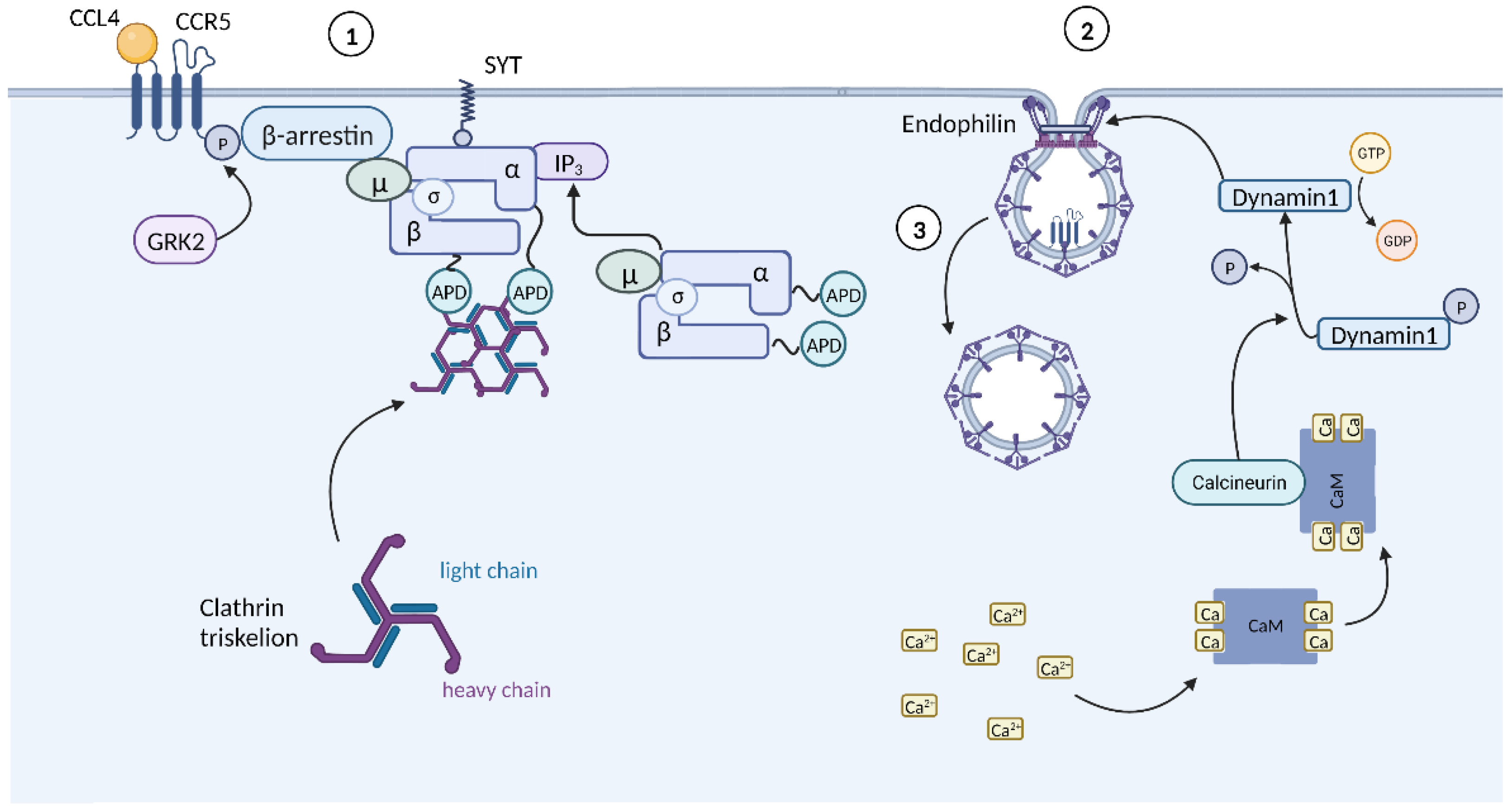

3.2. Chemokine-Mediated HIV Suppression

4. Stimulation of T-Cell Immune

5. Mosaic HIV Vaccines

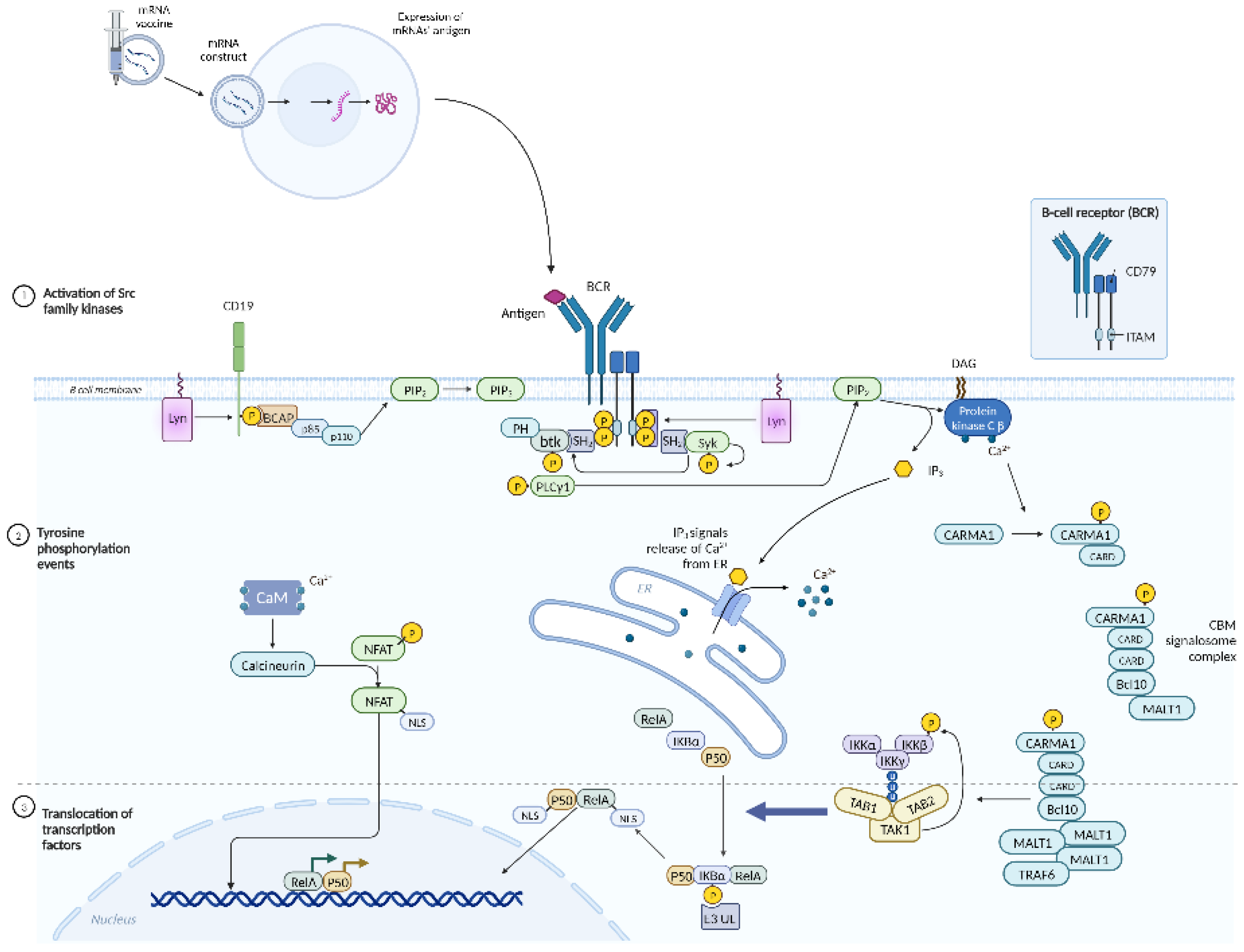

6. mRNA HIV Vaccine

7. Dendritic Cell-Based HIV Vaccines

8. Peptide-Based HIV Vaccines

9. DNA-Based HIV Vaccines

10. Viral Vector-Based HIV Vaccines

11. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Against HIV

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNAIDS Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/Homepage (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- AVAC | Global Health Advocacy, Access & Equity Available online: https://avac.org/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Hodge, D.; Back, D.J.; Gibbons, S.; Khoo, S.H.; Marzolini, C. Pharmacokinetics and Drug–Drug Interactions of Long-Acting Intramuscular Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2021, 60, 835–853. [CrossRef]

- Temereanca, A.; Ruta, S. Strategies to Overcome HIV Drug Resistance-Current and Future Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1133407. [CrossRef]

- Moskaleychik, F.F.; Laga, V.Y.; Delgado, E.; Vega, Y.; Fernandez-Garcia, A.; Perez-Alvarez, null; Kornilaeva, G.V.; Pronin, A.Y.; Zhernov, Y.V.; Thomson, M.M.; et al. [Rapid spread of the HIV-1 circular recombinant CRF02-AG in Russia and neighboring countries]. Vopr. Virusol. 2015, 60, 14–19.

- Karamov, E.; Epremyan, K.; Siniavin, A.; Zhernov, Y.; Cuevas, M.T.; Delgado, E.; Sánchez-Martínez, M.; Carrera, C.; Kornilaeva, G.; Turgiev, A.; et al. HIV-1 Genetic Diversity in Recently Diagnosed Infections in Moscow: Predominance of AFSU , Frequent Branching in Clusters, and Circulation of the Iberian Subtype G Variant. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2018, 34, 629–634. [CrossRef]

- Frolova, O.P.; Butylchenko, O.V.; Gadzhieva, P.G.; Timofeeva, M.Yu.; Basangova, V.A.; Petrova, V.O.; Fadeeva, I.A.; Kashutina, M.I.; Zabroda, N.N.; Basov, A.A.; et al. Medical Care for Tuberculosis-HIV-Coinfected Patients in Russia with Respect to a Changeable Patients’ Structure. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 86. [CrossRef]

- Zhernov, Y.V.; Kremb, S.; Helfer, M.; Schindler, M.; Harir, M.; Mueller, C.; Hertkorn, N.; Avvakumova, N.P.; Konstantinov, A.I.; Brack-Werner, R.; et al. Supramolecular Combinations of Humic Polyanions as Potent Microbicides with Polymodal Anti-HIV-Activities. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 212–224. [CrossRef]

- Zhernov, Y. Natural Humic Substances Interfere with Multiple Stages of the Replication Cycle of Human Immunodeficiency Virus. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, AB233. [CrossRef]

- Zhernov, Yu.V.; Khaitov, M.R. Microbicides for Topical Immunoprevention of HIV Infection. Bull. Sib. Med. 2019, 18, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Zhernov, Y.V.; Konstantinov, A.I.; Zherebker, A.; Nikolaev, E.; Orlov, A.; Savinykh, M.I.; Kornilaeva, G.V.; Karamov, E.V.; Perminova, I.V. Antiviral Activity of Natural Humic Substances and Shilajit Materials against HIV-1: Relation to Structure. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110312. [CrossRef]

- Zhernov, Y.V.; Petrova, V.O.; Simanduyev, M.Y.; Shcherbakov, D.V.; Polibin, R.V.; Mitrokhin, O.V.; Basov, A.A.; Zabroda, N.N.; Vysochanskaya, S.O.; Al-khaleefa, E.; et al. Microbicides for Topical HIV Immunoprophylaxis: Current Status and Future Prospects. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 668. [CrossRef]

- Vassall, A.; Pickles, M.; Chandrashekar, S.; Boily, M.-C.; Shetty, G.; Guinness, L.; Lowndes, C.M.; Bradley, J.; Moses, S.; Alary, M.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of HIV Prevention for High-Risk Groups at Scale: An Economic Evaluation of the Avahan Programme in South India. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e531–e540. [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, M.M.; Knowlton, G.S.; Butler, M.; Enns, E.A. Cost-Effectiveness of HIV Retention and Re-Engagement Interventions in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 2159–2168. [CrossRef]

- Bozzani, F.M.; Terris-Prestholt, F.; Quaife, M.; Gafos, M.; Indravudh, P.P.; Giddings, R.; Medley, G.F.; Malhotra, S.; Torres-Rueda, S. Costs and Cost-Effectiveness of Biomedical, Non-Surgical HIV Prevention Interventions: A Systematic Literature Review. PharmacoEconomics 2023, 41, 467–480. [CrossRef]

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2023 Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2023/summary/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Fanales-Belasio, E.; Raimondo, M.; Suligoi, B.; Buttò, S. HIV Virology and Pathogenetic Mechanisms of Infection: A Brief Overview. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2010, 46, 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, K.; Padda, J.; Khedr, A.; Ismail, D.; Zubair, U.; Al-Ewaidat, O.A.; Padda, S.; Cooper, A.C.; Jean-Charles, G. HIV and Messenger RNA Vaccine. Cureus 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nyamweya, S.; Hegedus, A.; Jaye, A.; Rowland-Jones, S.; Flanagan, K.L.; Macallan, D.C. Comparing HIV-1 and HIV-2 Infection: Lessons for Viral Immunopathogenesis. Rev. Med. Virol. 2013, 23, 221–240. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo-Pereira, J.M.; Santos-Costa, Q. HIV Interaction With Human Host: HIV-2 As a Model of a Less Virulent Infection. AIDS Rev. 2016, 18, 44–53.

- Travers, K.; Mboup, S.; Marlink, R.; Guèye-Nidaye, A.; Siby, T.; Thior, L.; Traore, I.; Dieng-Sarr, A.; Sankalé, J.-L.; Mullins, C.; et al. Natural Protection Against HIV-1 Infection Provided by HIV-2. Science 1995, 268, 1612–1615. [CrossRef]

- Rowland-Jones, S. Protective Immunity Against HIV Infection: Lessons from HIV-2 Infection. Future Microbiol. 2006, 1, 427–433. [CrossRef]

- Aberg, J.A.; Kaplan, J.E.; Libman, H.; Emmanuel, P.; Anderson, J.R.; Stone, V.E.; Oleske, J.M.; Currier, J.S.; Gallant, J.E. Primary Care Guidelines for the Management of Persons Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2009 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 651–681. [CrossRef]

- Checkley, M.A.; Luttge, B.G.; Freed, E.O. HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein Biosynthesis, Trafficking, and Incorporation. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 582–608. [CrossRef]

- Ng’uni, T.; Chasara, C.; Ndhlovu, Z.M. Major Scientific Hurdles in HIV Vaccine Development: Historical Perspective and Future Directions. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 590780. [CrossRef]

- Bour, S.; Geleziunas, R.; Wainberg, M.A. The Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) CD4 Receptor and Its Central Role in Promotion of HIV-1 Infection. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 59, 63–93. [CrossRef]

- Kwong, P.D.; Wyatt, R.; Robinson, J.; Sweet, R.W.; Sodroski, J.; Hendrickson, W.A. Structure of an HIV Gp120 Envelope Glycoprotein in Complex with the CD4 Receptor and a Neutralizing Human Antibody. Nature 1998, 393, 648–659. [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Patel, D.; Ma, Y.; Mann, J.F.S.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y. Employing Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies as a Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prophylactic & Therapeutic Application. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 697683. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X. The HIV-1 Gag P6: A Promising Target for Therapeutic Intervention. Retrovirology 2024, 21, 1. [CrossRef]

- Marie, V.; Gordon, M.L. The HIV-1 Gag Protein Displays Extensive Functional and Structural Roles in Virus Replication and Infectivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7569. [CrossRef]

- Mailler, E.; Bernacchi, S.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.-C.; Vivet-Boudou, V.; Smyth, R.P. The Life-Cycle of the HIV-1 Gag–RNA Complex. Viruses 2016, 8, 248. [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Tachedjian, G.; Mak, J. The Packaging and Maturation of the HIV-1 Pol Proteins. Curr. HIV Res. 3, 73–85. [CrossRef]

- Cafaro, A.; Schietroma, I.; Sernicola, L.; Belli, R.; Campagna, M.; Mancini, F.; Farcomeni, S.; Pavone-Cossut, M.R.; Borsetti, A.; Monini, P.; et al. Role of HIV-1 Tat Protein Interactions with Host Receptors in HIV Infection and Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1704. [CrossRef]

- Brigati, C.; Giacca, M.; Noonan, D.M.; Albini, A. HIV Tat, Its TARgets and the Control of Viral Gene Expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 220, 57–65. [CrossRef]

- Kula, A.; Marcello, A. Dynamic Post-Transcriptional Regulation of HIV-1 Gene Expression. Biology 2012, 1, 116–133. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.H.; Sarver, N. HIV Accessory Proteins: Emerging Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Med. 1995, 1, 479–485. [CrossRef]

- Sudderuddin, H.; Kinloch, N.N.; Jin, S.W.; Miller, R.L.; Jones, B.R.; Brumme, C.J.; Joy, J.B.; Brockman, M.A.; Brumme, Z.L. Longitudinal Within-Host Evolution of HIV Nef-Mediated CD4, HLA and SERINC5 Downregulation Activity: A Case Study. Retrovirology 2020, 17, 3. [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.; Strebel, K. HIV-1 Accessory Proteins: Vpu and Vif. In Human Retroviruses; Vicenzi, E., Poli, G., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2014; Vol. 1087, pp. 135–158 ISBN 978-1-62703-669-6.

- Rashid, F.; Zaongo, S.D.; Iqbal, H.; Harypursat, V.; Song, F.; Chen, Y. Interactions between HIV Proteins and Host Restriction Factors: Implications for Potential Therapeutic Intervention in HIV Infection. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Dubé, M.; Bego, M.G.; Paquay, C.; Cohen, É.A. Modulation of HIV-1-Host Interaction: Role of the Vpu Accessory Protein. Retrovirology 2010, 7, 114. [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M.; Rappaport, J. HIV-1 Accessory Protein Vpr: Relevance in the Pathogenesis of HIV and Potential for Therapeutic Intervention. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 25. [CrossRef]

- Vanegas-Torres, C.A.; Schindler, M. HIV-1 Vpr Functions in Primary CD4+ T Cells. Viruses 2024, 16, 420. [CrossRef]

- Bleul, C.C.; Wu, L.; Hoxie, J.A.; Springer, T.A.; Mackay, C.R. The HIV Coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 Are Differentially Expressed and Regulated on Human T Lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997, 94, 1925–1930. [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, M.; Blauvelt, A.; Lee, S.; Lapham, C.K.; Kiaus-Kovrun, V.; Mostowski, H.; Manischewitz, J.; Golding, H. Expression and Function of CCR5 and CXCR4 on Human Langerhans Cells and Macrophages: Implications for HIV Primary Infection. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 1369–1375. [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, M.A.; Justement, S.J.; Catanzaro, A.; Hallahan, C.A.; Ehler, L.A.; Mizell, S.B.; Kumar, P.N.; Mican, J.A.; Chun, T.-W.; Fauci, A.S. Expression of Chemokine Receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 in HIV-1-Infected and Uninfected Individuals. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 3195–3201. [CrossRef]

- Woodham, A.W.; Skeate, J.G.; Sanna, A.M.; Taylor, J.R.; Da Silva, D.M.; Cannon, P.M.; Kast, W.M. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Immune Cell Receptors, Coreceptors, and Cofactors: Implications for Prevention and Treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2016, 30, 291–306. [CrossRef]

- Barmania, F.; Pepper, M.S. C-C Chemokine Receptor Type Five (CCR5): An Emerging Target for the Control of HIV Infection. Appl. Transl. Genomics 2013, 2, 3–16. [CrossRef]

- McAleer, W.J.; Buynak, E.B.; Maigetter, R.Z.; Wampler, D.E.; Miller, W.J.; Hilleman, M.R. Human Hepatitis B Vaccine from Recombinant Yeast. Nature 1984, 307, 178–180. [CrossRef]

- Esparza, J. What Has 30 Years of HIV Vaccine Research Taught Us? Vaccines 2013, 1, 513–526. [CrossRef]

- Dolin, R.; Graham, B.S.; Greenberg, S.B.; Tacket, C.O.; Belshe, R.B.; Midthun, K.; Clements, M.L.; Gorse, G.J.; Horgan, B.W.; Atmar, R.L.; et al. The Safety and Immunogenicity of a Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Recombinant Gp160 Candidate Vaccine in Humans. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991, 114, 119–127. [CrossRef]

- Perkus, M.E.; Tartaglia, J.; Paoletti, E. Poxvirus-Based Vaccine Candidates for Cancer, AIDS, and Other Infectious Diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1995, 58, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Robert-Guroff, M.; Wong-Staal, F.; Gallo, R.C.; Moss, B. Expression of the HTLV-III Envelope Gene by a Recombinant Vaccinia Virus. Nature 1986, 320, 535–537. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-L.; Kosowski, S.G.; Dalrymple, J.M. Expression of AIDS Virus Envelope Gene in Recombinant Vaccinia Viruses. Nature 1986, 320, 537–540. [CrossRef]

- Cooney, E. Safety of and Immunological Response to a Recombinant Vaccinia Virus Vaccine Expressing HIV Envelope Glycoprotein. The Lancet 1991, 337, 567–572. [CrossRef]

- Cooney, E.L.; McElrath, M.J.; Corey, L.; Hu, S.L.; Collier, A.C.; Arditti, D.; Hoffman, M.; Coombs, R.W.; Smith, G.E.; Greenberg, P.D. Enhanced Immunity to Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Envelope Elicited by a Combined Vaccine Regimen Consisting of Priming with a Vaccinia Recombinant Expressing HIV Envelope and Boosting with Gp160 Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993, 90, 1882–1886. [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.S.; Matthews, T.J.; Belshe, R.B.; Clements, M.L.; Dolin, R.; Wright, P.F.; Gorse, G.J.; Schwartz, D.H.; Keefer, M.C.; Bolognesi, D.P.; et al. Augmentation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Neutralizing Antibody by Priming with Gp160 Recombinant Vaccinia and Boosting with Gp160 in Vaccinia-Naive Adults. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 167, 533–537. [CrossRef]

- Redfield, R.R.; Wright, D.C.; James, W.D.; Jones, T.S.; Brown, C.; Burke, D.S. Disseminated Vaccinia in a Military Recruit with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 316, 673–676. [CrossRef]

- Zagury, D.; Bernard, J.; Cheynier, R.; Desportes, I.; Leonard, R.; Fouchard, M.; Reveil, B.; Ittele, D.; Lurhuma, Z.; Mbayo, K.; et al. A Group Specific Anamnestic Immune Reaction against HIV-1 Induced by a Candidate Vaccine against AIDS. Nature 1988, 332, 728–731. [CrossRef]

- Cox, W.I.; Tartaglia, J.; Paoletti, E. Induction of Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes by Recombinant Canarypox (ALVAC) and Attenuated Vaccinia (NYVAC) Viruses Expressing the HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein. Virology 1993, 195, 845–850. [CrossRef]

- Pialoux, G.; Excler, J.-L.; Rivière, Y.; Gonzalez-Canali, G.; Feuillie, V.; Coulaud, P.; Gluckman, J.-C.; Matthews, T.J.; Meignier, B.; Kieny, M.-P.; et al. A Prime-Boost Approach to HIV Preventive Vaccine Using a Recombinant Canarypox Virus Expressing Glycoprotein 160 (MN) Followed by a Recombinant Glycoprotein 160 (MN/LAI). AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1995, 11, 373–381. [CrossRef]

- Marovich, M.A. ALVAC-HIV Vaccines: Clinical Trial Experience Focusing on Progress in Vaccine Development. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2004, 3, S99–S104. [CrossRef]

- Thongcharoen, P.; Suriyanon, V.; Paris, R.M.; Khamboonruang, C.; De Souza, M.S.; Ratto-Kim, S.; Karnasuta, C.; Polonis, V.R.; Baglyos, L.; Habib, R.E.; et al. A Phase 1/2 Comparative Vaccine Trial of the Safety and Immunogenicity of a CRF01_AE (Subtype E) Candidate Vaccine: ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) Prime With Oligomeric Gp160 (92TH023/LAI-DID) or Bivalent Gp120 (CM235/SF2) Boost. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2007, 46, 48–55. [CrossRef]

- The rgp120 HIV Vaccine Study Group Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial of a Recombinant Glycoprotein 120 Vaccine to Prevent HIV-1 Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 654–665. [CrossRef]

- Pitisuttithum, P.; Gilbert, P.; Gurwith, M.; Heyward, W.; Martin, M.; van Griensven, F.; Hu, D.; Tappero, J.W.; Choopanya, K.; Bangkok Vaccine Evaluation Group Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Efficacy Trial of a Bivalent Recombinant Glycoprotein 120 HIV-1 Vaccine among Injection Drug Users in Bangkok, Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 194, 1661–1671. [CrossRef]

- Loreto, C.; La Rocca, G.; Anzalone, R.; Caltabiano, R.; Vespasiani, G.; Castorina, S.; Ralph, D.J.; Cellek, S.; Musumeci, G.; Giunta, S.; et al. The Role of Intrinsic Pathway in Apoptosis Activation and Progression in Peyronie’s Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, R.; Kheirollahi, A.; Davoodi, J. Apaf-1: Regulation and Function in Cell Death. Biochimie 2017, 135, 111–125. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Lucas, P.C.; McAllister-Lucas, L.M. Canonical and Non-Canonical Roles of GRK2 in Lymphocytes. Cells 2021, 10, 307. [CrossRef]

- Laporte, S.A.; Miller, W.E.; Kim, K.-M.; Caron, M.G. β-Arrestin/AP-2 Interaction in G Protein-Coupled Receptor Internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 9247–9254. [CrossRef]

- Sundborger, A.; Soderblom, C.; Vorontsova, O.; Evergren, E.; Hinshaw, J.E.; Shupliakov, O. An Endophilin–Dynamin Complex Promotes Budding of Clathrin-Coated Vesicles during Synaptic Vesicle Recycling. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 133–143. [CrossRef]

- Royle, S.J. The Cellular Functions of Clathrin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 1823–1832. [CrossRef]

- McMichael, A.; Hanke, T. The Quest for an AIDS Vaccine: Is the CD8+ T-Cell Approach Feasible? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 283–291. [CrossRef]

- Mudd, P.A.; Martins, M.A.; Ericsen, A.J.; Tully, D.C.; Power, K.A.; Bean, A.T.; Piaskowski, S.M.; Duan, L.; Seese, A.; Gladden, A.D.; et al. Vaccine-Induced CD8+ T Cells Control AIDS Virus Replication. Nature 2012, 491, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Schoenly, K.A.; Weiner, D.B. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Vaccine Development: Recent Advances in the Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Platform “Spotty Business.” J. Virol. 2008, 82, 3166–3180. [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, S.P.; Mehrotra, D.V.; Duerr, A.; Fitzgerald, D.W.; Mogg, R.; Li, D.; Gilbert, P.B.; Lama, J.R.; Marmor, M.; Del Rio, C.; et al. Efficacy Assessment of a Cell-Mediated Immunity HIV-1 Vaccine (the Step Study): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Test-of-Concept Trial. The Lancet 2008, 372, 1881–1893. [CrossRef]

- Duerr, A.; Huang, Y.; Buchbinder, S.; Coombs, R.W.; Sanchez, J.; Del Rio, C.; Casapia, M.; Santiago, S.; Gilbert, P.; Corey, L.; et al. Extended Follow-up Confirms Early Vaccine-Enhanced Risk of HIV Acquisition and Demonstrates Waning Effect Over Time Among Participants in a Randomized Trial of Recombinant Adenovirus HIV Vaccine (Step Study). J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 206, 258–266. [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, A.T.; Roederer, M.; Koup, R.A.; Bailer, R.T.; Enama, M.E.; Nason, M.C.; Martin, J.E.; Rucker, S.; Andrews, C.A.; Gomez, P.L.; et al. Phase I Clinical Evaluation of a Six-Plasmid Multiclade HIV-1 DNA Candidate Vaccine. Vaccine 2007, 25, 4085–4092. [CrossRef]

- McEnery, R. HVTN 505 Trial Expanded to See If Vaccine Candidates Can Block HIV Acquisition. IAVI Rep. Newsl. Int. AIDS Vaccine Res. 2011, 15, 17.

- Catanzaro, A.T.; Koup, R.A.; Roederer, M.; Bailer, R.T.; Enama, M.E.; Moodie, Z.; Gu, L.; Martin, J.E.; Novik, L.; Chakrabarti, B.K.; et al. Phase 1 Safety and Immunogenicity Evaluation of a Multiclade HIV-1 Candidate Vaccine Delivered by a Replication-Defective Recombinant Adenovirus Vector. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 194, 1638–1649. [CrossRef]

- Fischinger, S.; Shin, S.; Boudreau, C.M.; Ackerman, M.; Rerks-Ngarm, S.; Pitisuttithum, P.; Nitayaphan, S.; Kim, J.H.; Robb, M.L.; Michael, N.L.; et al. Protein-Based, but Not Viral Vector Alone, HIV Vaccine Boosting Drives an IgG1-Biased Polyfunctional Humoral Immune Response. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e135057. [CrossRef]

- Rerks-Ngarm, S.; Pitisuttithum, P.; Excler, J.-L.; Nitayaphan, S.; Kaewkungwal, J.; Premsri, N.; Kunasol, P.; Karasavvas, N.; Schuetz, A.; Ngauy, V.; et al. Randomized, Double-Blind Evaluation of Late Boost Strategies for HIV-Uninfected Vaccine Recipients in the RV144 HIV Vaccine Efficacy Trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1255–1263. [CrossRef]

- Pitisuttithum, P.; Nitayaphan, S.; Chariyalertsak, S.; Kaewkungwal, J.; Dawson, P.; Dhitavat, J.; Phonrat, B.; Akapirat, S.; Karasavvas, N.; Wieczorek, L.; et al. Late Boosting of the RV144 Regimen with AIDSVAX B/E and ALVAC-HIV in HIV-Uninfected Thai Volunteers: A Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e238–e248. [CrossRef]

- Gray, G.E.; Huang, Y.; Grunenberg, N.; Laher, F.; Roux, S.; Andersen-Nissen, E.; De Rosa, S.C.; Flach, B.; Randhawa, A.K.; Jensen, R.; et al. Immune Correlates of the Thai RV144 HIV Vaccine Regimen in South Africa. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaax1880. [CrossRef]

- Bekker, L.-G.; Moodie, Z.; Grunenberg, N.; Laher, F.; Tomaras, G.D.; Cohen, K.W.; Allen, M.; Malahleha, M.; Mngadi, K.; Daniels, B.; et al. Subtype C ALVAC-HIV and Bivalent Subtype C Gp120/MF59 HIV-1 Vaccine in Low-Risk, HIV-Uninfected, South African Adults: A Phase 1/2 Trial. Lancet HIV 2018, 5, e366–e378. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, B.F.; Gilbert, P.B.; McElrath, M.J.; Zolla-Pazner, S.; Tomaras, G.D.; Alam, S.M.; Evans, D.T.; Montefiori, D.C.; Karnasuta, C.; Sutthent, R.; et al. Immune-Correlates Analysis of an HIV-1 Vaccine Efficacy Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1275–1286. [CrossRef]

- Zolla-Pazner, S.; Gilbert, P.B. Revisiting the Correlate of Reduced HIV Infection Risk in the Rv144 Vaccine Trial. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00629-19. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) A Phase-1 Open-Label Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of Synthetic DNAs Encoding NP-GT8 and IL-12, With or Without a TLR-Agonist- Adjuvanted HIV Env Trimer 4571 Boost, in Adults Without HIV; clinicaltrials.gov, 2024;

- Pitisuttithum, P.; Nitayaphan, S.; Chariyalertsak, S.; Kaewkungwal, J.; Dawson, P.; Dhitavat, J.; Phonrat, B.; Akapirat, S.; Karasavvas, N.; Wieczorek, L.; et al. Late Boosting of the RV144 Regimen with AIDSVAX B/E and ALVAC-HIV in HIV-Uninfected Thai Volunteers, a Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e238–e248. [CrossRef]

- HIV Vaccine Trials Network Phase 1b Randomized Double Blind Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of the Vaccine Regimen ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) Followed by AIDSVAX® B/E in Healthy, HIV-1 Uninfected Adult Participants in South Africa; clinicaltrials.gov, 2019;

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) A Phase 1-2 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of Clade C ALVAC-HIV (vCP2438) and Bivalent Subtype C gp120/MF59® in HIV-Uninfected Adults at Low Risk of HIV Infection; clinicaltrials.gov, 2021;

- Trovato, M.; D’Apice, L.; Prisco, A.; De Berardinis, P. HIV Vaccination: A Roadmap among Advancements and Concerns. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1241. [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, C.M.; Raboud, J.; Bernard, N.F.; Montaner, J.S.; Gill, M.J.; Rachlis, A.; Fong, I.W.; Schlech, W.; Djurdjev, O.; Freedman, J.; et al. Active Immunization of Patients with HIV Infection: A Study of the Effect of VaxSyn, a Recombinant HIV Envelope Subunit Vaccine, on Progression of Immunodeficiency. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1998, 14, 483–490. [CrossRef]

- Cooney, E.L.; Collier, A.C.; Greenberg, P.D.; Coombs, R.W.; Zarling, J.; Arditti, D.E.; Hoffman, M.C.; Hu, S.L.; Corey, L. Safety of and Immunological Response to a Recombinant Vaccinia Virus Vaccine Expressing HIV Envelope Glycoprotein. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1991, 337, 567–572. [CrossRef]

- VaxGen A Phase III Trial to Determine the Efficacy of AIDSVAX B/E Vaccine in Intravenous Drug Users in Bangkok, Thailand; clinicaltrials.gov, 2005;

- VaxGen A Phase III Trial to Determine the Efficacy of Bivalent AIDSVAX B/B Vaccine in Adults at Risk of Sexually Transmitted HIV-1 Infection in North America; clinicaltrials.gov, 2005;

- Gray, G.; Buchbinder, S.; Duerr, A. Overview of STEP and Phambili Trial Results: Two Phase IIb Test of Concept Studies Investigating the Efficacy of MRK Ad5 Gag/Pol/Nef Sub-Type B HIV Vaccine. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2010, 5, 357–361. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) A Multicenter Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Phase IIB Test-of-Concept Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of a Three-Dose Regimen of the Clade B-Based Merck Adenovirus Serotype 5 HIV-1 Gag/Pol/Nef Vaccine in HIV-1 Uninfected Adults in South Africa; clinicaltrials.gov, 2021;

- U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command A Phase III Trial of Aventis Pasteur Live Recombinant ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) Priming With VaxGen Gp120 B/E (AIDSVAX B/E) Boosting in HIV-Uninfected Thai Adults; clinicaltrials.gov, 2019;

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Phase 2b, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Test-of-Concept Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of a Multiclade HIV-1 DNA Plasmid Vaccine Followed by a Multiclade HIV-1 Recombinant Adenoviral Vector Vaccine in HIV-Uninfected, Adenovirus Type 5 Neutralizing Antibody Negative, Circumcised Men and Male-to-Female (MTF) Transgender Persons, Who Have Sex With Men; clinicaltrials.gov, 2021;

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) A Pivotal Phase 2b/3 Multisite, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of ALVAC-HIV (vCP2438) and Bivalent Subtype C Gp120/MF59 in Preventing HIV-1 Infection in Adults in South Africa; clinicaltrials.gov, 2024;

- Janssen Vaccines & Prevention B.V. A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2b Efficacy Study of a Heterologous Prime/Boost Vaccine Regimen of Ad26.Mos4.HIV and Aluminum Phosphate-Adjuvanted Clade C Gp140 in Preventing HIV-1 Infection in Adult Women in Sub-Saharan Africa; clinicaltrials.gov, 2023;

- Janssen Vaccines & Prevention B.V. A Multi-Center, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Efficacy Study of a Heterologous Vaccine Regimen of Ad26.Mos4.HIV and Adjuvanted Clade C Gp140 and Mosaic Gp140 to Prevent HIV-1 Infection Among Cis-Gender Men and Transgender Individuals Who Have Sex With Cis-Gender Men and/or Transgender Individuals; clinicaltrials.gov, 2024;

- MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit A Phase IIb Three-Arm, Two-Stage HIV Prophylactic Vaccine Trial With a Second Randomisation to Compare TAF/FTC to TDF/FTC as Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis; clinicaltrials.gov, 2023;

- Mu, Z.; Haynes, B.F.; Cain, D.W. HIV mRNA Vaccines—Progress and Future Paths. Vaccines 2021, 9, 134. [CrossRef]

- Hobeika, E.; Nielsen, P.J.; Medgyesi, D. Signaling Mechanisms Regulating B-Lymphocyte Activation and Tolerance. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 93, 143–158. [CrossRef]

- Debant, M.; Hemon, P.; Brigaudeau, C.; Renaudineau, Y.; Mignen, O. Calcium Signaling and Cell Fate: How Can Ca2+ Signals Contribute to Wrong Decisions for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemic B Lymphocyte Outcome? Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2015, 59, 379–389. [CrossRef]

- Grondona, P.; Bucher, P.; Schulze-Osthoff, K.; Hailfinger, S.; Schmitt, A. NF-κB Activation in Lymphoid Malignancies: Genetics, Signaling, and Targeted Therapy. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 38. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.D.; Huang, X.; Jørgensen, H.G.; Michie, A.M. Transcriptional Regulation by the NFAT Family in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Hemato 2021, 2, 556–571. [CrossRef]

- International AIDS Vaccine Initiative A Phase 1, Randomized, First-in-Human, Open-Label Study to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of eOD-GT8 60mer mRNA Vaccine (mRNA-1644) and Core-G28v2 60mer mRNA Vaccine (mRNA-1644v2-Core) in HIV-1 Uninfected Adults in Good General Health; clinicaltrials.gov, 2024;

- International AIDS Vaccine Initiative A Phase 1 Study to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of eOD-GT8 60mer mRNA Vaccine (mRNA-1644) in HIV-1 Uninfected Adults in Good General Health; clinicaltrials.gov, 2023;

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) A Phase 1, Randomized, Open-Label Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of BG505 MD39.3, BG505 MD39.3 Gp151, and BG505 MD39.3 Gp151 CD4KO HIV Trimer mRNA Vaccines in Healthy, HIV-Uninfected Adult Participants; clinicaltrials.gov, 2024;

- Saxena, M.; Bhardwaj, N. Re-Emergence of Dendritic Cell Vaccines for Cancer Treatment. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 119–137. [CrossRef]

- Sabado, R.L.; Bhardwaj, N. Cancer Immunotherapy: Dendritic-Cell Vaccines on the Move. Nature 2015, 519, 300–301. [CrossRef]

- Espinar-Buitrago, M.; Muñoz-Fernández, M.A. New Approaches to Dendritic Cell-Based Therapeutic Vaccines Against HIV-1 Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 719664. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.M.; Routy, J.-P.; Welles, S.; DeBenedette, M.; Tcherepanova, I.; Angel, J.B.; Asmuth, D.M.; Stein, D.K.; Baril, J.-G.; McKellar, M.; et al. Dendritic Cell Immunotherapy for HIV-1 Infection Using Autologous HIV-1 RNA: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 72, 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Macatangay, B.J.C.; Riddler, S.A.; Wheeler, N.D.; Spindler, J.; Lawani, M.; Hong, F.; Buffo, M.J.; Whiteside, T.L.; Kearney, M.F.; Mellors, J.W.; et al. Therapeutic Vaccination With Dendritic Cells Loaded With Autologous HIV Type 1–Infected Apoptotic Cells. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 1400–1409. [CrossRef]

- García, F.; Plana, M.; Climent, N.; León, A.; Gatell, J.M.; Gallart, T. Dendritic Cell Based Vaccines for HIV Infection: The Way Ahead. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 2445–2452. [CrossRef]

- García, F.; Climent, N.; Guardo, A.C.; Gil, C.; León, A.; Autran, B.; Lifson, J.D.; Martínez-Picado, J.; Dalmau, J.; Clotet, B.; et al. A Dendritic Cell–Based Vaccine Elicits T Cell Responses Associated with Control of HIV-1 Replication. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5. [CrossRef]

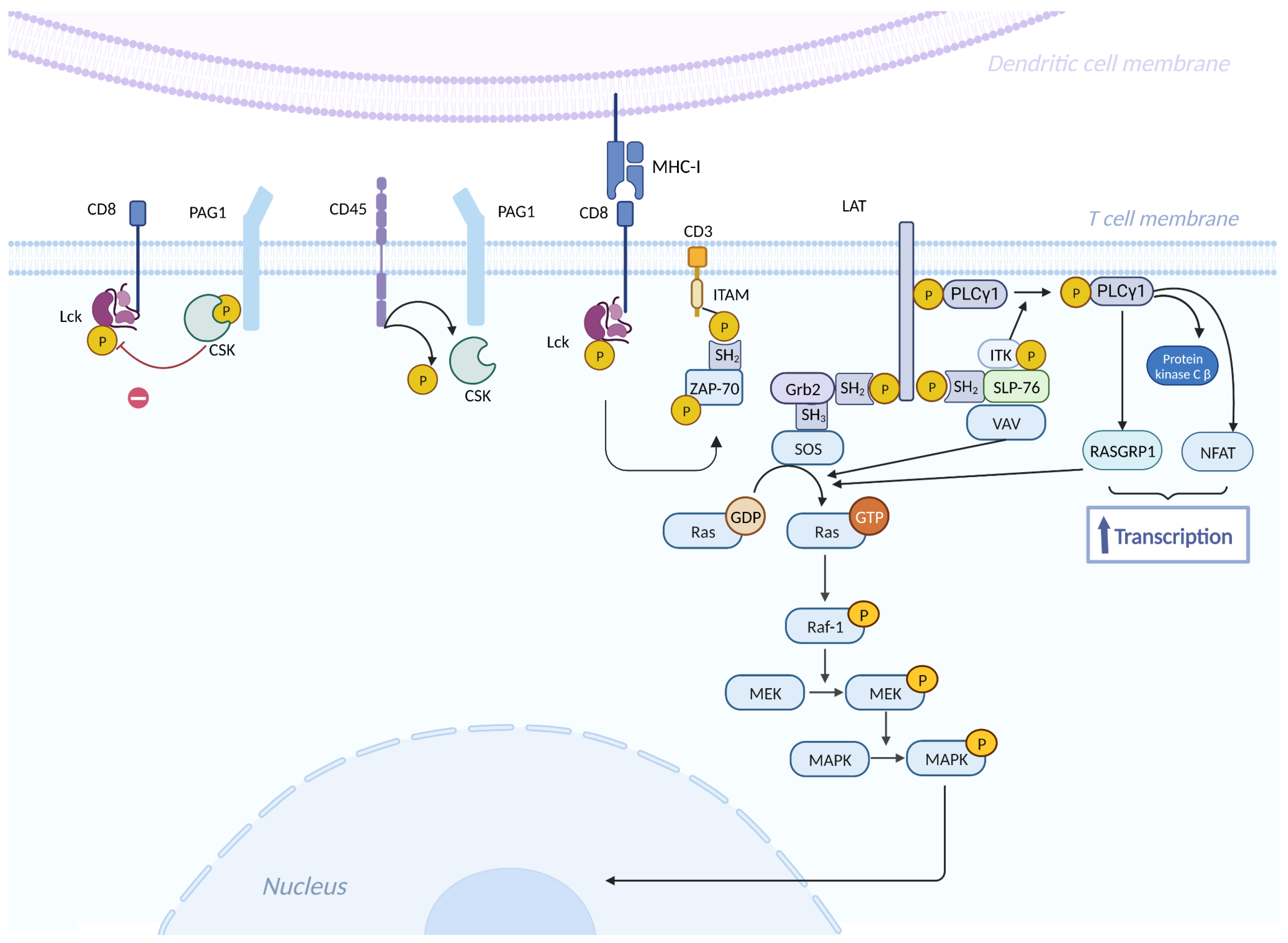

- Muro, R.; Takayanagi, H.; Nitta, T. T Cell Receptor Signaling for γδT Cell Development. Inflamm. Regen. 2019, 39, 6. [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Yun, Y. Transmembrane Adaptor Proteins Positively Regulating the Activation of Lymphocytes. Immune Netw. 2009, 9, 53. [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, J.D. The Ras-MAPK Signal Transduction Pathway. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3. [CrossRef]

- Malonis, R.J.; Lai, J.R.; Vergnolle, O. Peptide-Based Vaccines: Current Progress and Future Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 3210–3229. [CrossRef]

- Larijani, M.S.; Sadat, S.M.; Bolhassani, A.; Pouriayevali, M.H.; Bahramali, G.; Ramezani, A. In Silico Design and Immunologic Evaluation of HIV-1 P24-Nef Fusion Protein to Approach a Therapeutic Vaccine Candidate. Curr. HIV Res. 2019, 16, 322–337. [CrossRef]

- Skwarczynski, M.; Toth, I. Peptide-Based Synthetic Vaccines. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 842–854. [CrossRef]

- Rockstroh, J.K.; Asmuth, D.; Pantaleo, G.; Clotet, B.; Podzamczer, D.; van Lunzen, J.; Arastéh, K.; Mitsuyasu, R.; Peters, B.; Silvia, N.; et al. Re-Boost Immunizations with the Peptide-Based Therapeutic HIV Vaccine, Vacc-4x, Restores Geometric Mean Viral Load Set-Point during Treatment Interruption. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210965. [CrossRef]

- Pollard, R.B.; Rockstroh, J.K.; Pantaleo, G.; Asmuth, D.M.; Peters, B.; Lazzarin, A.; Garcia, F.; Ellefsen, K.; Podzamczer, D.; van Lunzen, J.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the Peptide-Based Therapeutic Vaccine for HIV-1, Vacc-4x: A Phase 2 Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 291–300. [CrossRef]

- Gharakhanian, S.; Katlama, C.; Launay, O.; Bodilis, H.; Calin, R.; Ho, R.; Fang, T.; Marcu, M.; Autran, B.; Vieillard, V.; et al. VAC-3S, an Immunoprotective HIV Vaccine Directed to the 3S Motif of Gp41, in Patients Receiving ART: Safety, Dose & Immunization Schedule Assessment. Phase I Study Results: Immunologic Endpoints & Safety I ● Introduction and Background Phase I Study: Methods Phase I Study Results: Immunologic Endpoints & Safety.; October 2013.

- Brekke, K.; Sommerfelt, M.; Ökvist, M.; Dyrhol-Riise, A.M.; Kvale, D. The Therapeutic HIV Env C5/Gp41 Vaccine Candidate Vacc-C5 Induces Specific T Cell Regulation in a Phase I/II Clinical Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 228. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.J.; Gómez Román, V.R.; Jensen, S.S.; Leo-Hansen, C.; Karlsson, I.; Katzenstein, T.L.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Jespersen, S.; Janitzek, C.M.; Té, D. da S.; et al. Clade A HIV-1 Gag-Specific T Cell Responses Are Frequent but Do Not Correlate with Viral Loads in a Cohort of Treatment-Naive HIV-Infected Individuals Living in Guinea-Bissau. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. CVI 2012, 19, 1999–2001. [CrossRef]

- Boffito, M.; Fox, J.; Bowman, C.; Fisher, M.; Orkin, C.; Wilkins, E.; Jackson, A.; Pleguezuelos, O.; Robinson, S.; Stoloff, G.A.; et al. Safety, Immunogenicity and Efficacy Assessment of HIV Immunotherapy in a Multi-Centre, Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Phase Ib Human Trial. Vaccine 2013, 31, 5680–5686. [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, B.; Morrow, M.P.; Hutnick, N.A.; Shin, T.H.; Lucke, C.E.; Weiner, D.B. Clinical Applications of DNA Vaccines: Current Progress. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2011, 53, 296–302. [CrossRef]

- van Diepen, M.T.; Chapman, R.; Douglass, N.; Galant, S.; Moore, P.L.; Margolin, E.; Ximba, P.; Morris, L.; Rybicki, E.P.; Williamson, A.-L. Prime-Boost Immunizations with DNA, Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara, and Protein-Based Vaccines Elicit Robust HIV-1 Tier 2 Neutralizing Antibodies against the CAP256 Superinfecting Virus. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e02155-18. [CrossRef]

- Lisziewicz, J.; Calarota, S.A.; Lori, F. The Potential of Topical DNA Vaccines Adjuvanted by Cytokines. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2007, 7, 1563–1574. [CrossRef]

- Felber, B.K.; Valentin, A.; Rosati, M.; Bergamaschi, C.; Pavlakis, G.N. HIV DNA Vaccine: Stepwise Improvements Make a Difference. Vaccines 2014, 2, 354–379. [CrossRef]

- Munson, P.; Liu, Y.; Bratt, D.; Fuller, J.T.; Hu, X.; Pavlakis, G.N.; Felber, B.K.; Mullins, J.I.; Fuller, D.H. Therapeutic Conserved Elements (CE) DNA Vaccine Induces Strong T-Cell Responses against Highly Conserved Viral Sequences during Simian-Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 1820–1831. [CrossRef]

- Colby, D.J.; Sarnecki, M.; Barouch, D.H.; Tipsuk, S.; Stieh, D.J.; Kroon, E.; Schuetz, A.; Intasan, J.; Sacdalan, C.; Pinyakorn, S.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Ad26 and MVA Vaccines in Acutely Treated HIV and Effect on Viral Rebound after Antiretroviral Therapy Interruption. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 498–501. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.M.; Zheng, L.; Wilson, C.C.; Tebas, P.; Matining, R.M.; Egan, M.A.; Eldridge, J.; Landay, A.L.; Clifford, D.B.; Luetkemeyer, A.F.; et al. The Safety and Immunogenicity of an Interleukin-12–Enhanced Multiantigen DNA Vaccine Delivered by Electroporation for the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 71, 163–171. [CrossRef]

- Tebas, P.; Ramirez, L.; Morrow, M.; Yan, J.; Shah, D.; Lee, J.; Weiner, D.; Boyer, J.; Bagarazzi, M.; Sardesai, N. Potent Cellular Immune Responses after Therapeutic Immunization of HIV-Positive Patients with the PENNVAX®-B DNA Vaccine in a Phase I Trial. Retrovirology 2012, 9, P276, 1742-4690-9-S2-P276. [CrossRef]

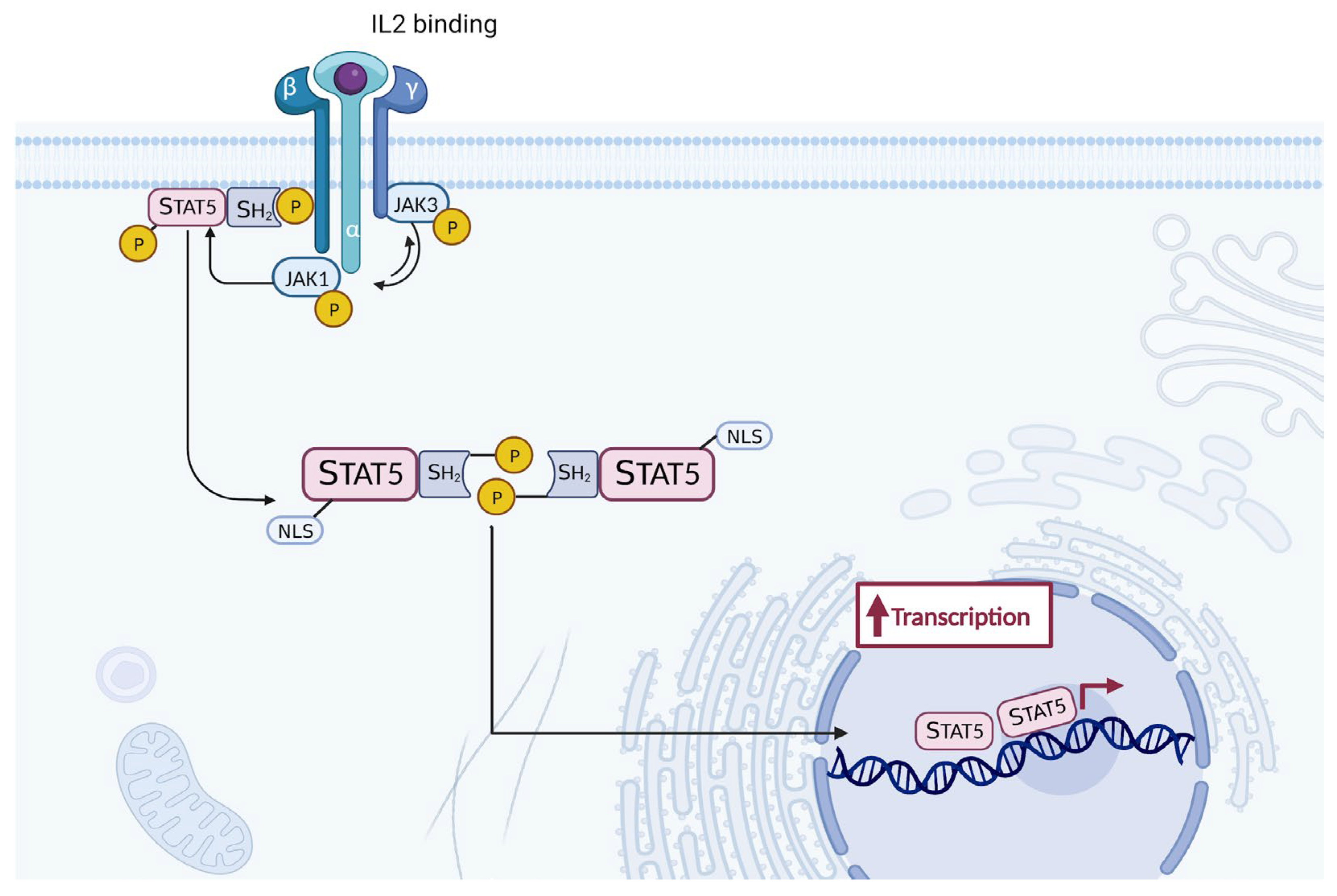

- Ross, S.H.; Cantrell, D.A. Signaling and Function of Interleukin-2 in T Lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 36, 411–433. [CrossRef]

- Riddler, S. A Phase I Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of a Therapeutic HIV Vaccine Composed of Autologous Dendritic Cells Loaded with Autologous Inactivated Whole Virus or Conserved Peptides in ART-Treated HIV-Infected Adults; clinicaltrials.gov, 2024;

- GeneCure Biotechnologies A Phase I Dose-Escalation Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of a Replication-Defective HIV-1 Vaccine (HIVAXTM) in HIV-1 Infected Subjects Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy; clinicaltrials.gov, 2020;

- ANRS, Emerging Infectious Diseases A Phase I/II Randomised Therapeutic HIV Vaccine Trial in Individuals Who Started Antiretrovirals During Primary or Chronic Infection; clinicaltrials.gov, 2019;

- Theravectys S.A. A Multi-Center, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase I/II Trial to Compare the Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of the Therapeutic THV01 Vaccination at 5.10E+6 TU (Transducing Unit) , 5.10E+7 TU (Transducing Unit) or 5.10E+8 TU (Transducing Unit) Doses to Placebo in HIV-1 Clade B Infected Patients Under Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART); clinicaltrials.gov, 2019;

- Janssen Vaccines & Prevention B.V. A Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity Study of 2 Different Regimens of Tetravalent Ad26.Mos4.HIV Prime Followed by Boost With MVA-Mosaic OR Ad26.Mos4.HIV Plus a Combination of Mosaic and Clade C Gp140 Protein in HIV-1 Infected Adults on Suppressive ART; clinicaltrials.gov, 2022;

- McCune, J.M.; Rabin, L.B.; Feinberg, M.B.; Lieberman, M.; Kosek, J.C.; Reyes, G.R.; Weissman, I.L. Endoproteolytic Cleavage of Gp160 Is Required for the Activation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Cell 1988, 53, 55–67. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Chertova, E.; Bess, J.; Lifson, J.D.; Arthur, L.O.; Liu, J.; Taylor, K.A.; Roux, K.H. Electron Tomography Analysis of Envelope Glycoprotein Trimers on HIV and Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 15812–15817. [CrossRef]

- Caillat, C.; Guilligay, D.; Torralba, J.; Friedrich, N.; Nieva, J.L.; Trkola, A.; Chipot, C.J.; Dehez, F.L.; Weissenhorn, W. Structure of HIV-1 Gp41 with Its Membrane Anchors Targeted by Neutralizing Antibodies. eLife 2021, 10, e65005. [CrossRef]

- Parker Miller, E.; Finkelstein, M.T.; Erdman, M.C.; Seth, P.C.; Fera, D. A Structural Update of Neutralizing Epitopes on the HIV Envelope, a Moving Target. Viruses 2021, 13, 1774. [CrossRef]

- Kwong, P.D.; Wyatt, R.; Robinson, J.; Sweet, R.W.; Sodroski, J.; Hendrickson, W.A. Structure of an HIV Gp120 Envelope Glycoprotein in Complex with the CD4 Receptor and a Neutralizing Human Antibody. Nature 1998, 393, 648–659. [CrossRef]

- Da, L.-T.; Quan, J.-M.; Wu, Y.-D. Understanding of the Bridging Sheet Formation of HIV-1 Glycoprotein Gp120. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 14536–14543. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Vogan, E.M.; Gong, H.; Skehel, J.J.; Wiley, D.C.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of an Unliganded Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Gp120 Core. Nature 2005, 433, 834–841. [CrossRef]

- Bartesaghi, A.; Merk, A.; Borgnia, M.J.; Milne, J.L.S.; Subramaniam, S. Prefusion Structure of Trimeric HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein Determined by Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 1352–1357. [CrossRef]

- Tamm, L.K.; Lee, J.; Liang, B. Capturing Glimpses of an Elusive HIV Gp41 Prehairpin Fusion Intermediate. Structure 2014, 22, 1225–1226. [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Gorny, M.K.; Zolla-Pazner, S.; Kong, X.-P. The V1V2 Region of HIV-1 Gp120 Forms a Five-Stranded Beta Barrel. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 8003–8010. [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.; Soto, C.; Yang, M.M.; Davenport, T.M.; Guttman, M.; Bailer, R.T.; Chambers, M.; Chuang, G.-Y.; DeKosky, B.J.; Doria-Rose, N.A.; et al. Structures of HIV-1 Env V1V2 with Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Reveal Commonalities That Enable Vaccine Design. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 81–90. [CrossRef]

- McLellan, J.S.; Pancera, M.; Carrico, C.; Gorman, J.; Julien, J.-P.; Khayat, R.; Louder, R.; Pejchal, R.; Sastry, M.; Dai, K.; et al. Structure of HIV-1 Gp120 V1/V2 Domain with Broadly Neutralizing Antibody PG9. Nature 2011, 480, 336–343. [CrossRef]

- Löving, R.; Sjöberg, M.; Wu, S.-R.; Binley, J.M.; Garoff, H. Inhibition of the HIV-1 Spike by Single-PG9/16-Antibody Binding Suggests a Coordinated-Activation Model for Its Three Protomeric Units. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7000–7007. [CrossRef]

- Wilen, C.B.; Tilton, J.C.; Doms, R.W. HIV: Cell Binding and Entry. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006866–a006866. [CrossRef]

- Sok, D.; Pauthner, M.; Briney, B.; Lee, J.H.; Saye-Francisco, K.L.; Hsueh, J.; Ramos, A.; Le, K.M.; Jones, M.; Jardine, J.G.; et al. A Prominent Site of Antibody Vulnerability on HIV Envelope Incorporates a Motif Associated with CCR5 Binding and Its Camouflaging Glycans. Immunity 2016, 45, 31–45. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Barnes, C.O.; Gautam, R.; Cetrulo Lorenzi, J.C.; Mayer, C.T.; Oliveira, T.Y.; Ramos, V.; Cipolla, M.; Gordon, K.M.; Gristick, H.B.; et al. A Broadly Neutralizing Macaque Monoclonal Antibody against the HIV-1 V3-Glycan Patch. eLife 2020, 9, e61991. [CrossRef]

- Bonsignori, M.; Kreider, E.F.; Fera, D.; Meyerhoff, R.R.; Bradley, T.; Wiehe, K.; Alam, S.M.; Aussedat, B.; Walkowicz, W.E.; Hwang, K.-K.; et al. Staged Induction of HIV-1 Glycan–Dependent Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaai7514. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Ju, B.; Shapero, B.; Lin, X.; Ren, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, Y.; Sou, C.; et al. A VH 1-69 Antibody Lineage from an Infected Chinese Donor Potently Neutralizes HIV-1 by Targeting the V3 Glycan Supersite. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb1328. [CrossRef]

- Simonich, C.A.; Williams, K.L.; Verkerke, H.P.; Williams, J.A.; Nduati, R.; Lee, K.K.; Overbaugh, J. HIV-1 Neutralizing Antibodies with Limited Hypermutation from an Infant. Cell 2016, 166, 77–87. [CrossRef]

- Travers, S.A. Conservation, Compensation, and Evolution of N-Linked Glycans in the HIV-1 Group M Subtypes and Circulating Recombinant Forms. ISRN AIDS 2012, 2012, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Ju, B.; Chen, Y.; He, L.; Ren, L.; Liu, J.; Hong, K.; Su, B.; Wang, Z.; Ozorowski, G.; et al. Key Gp120 Glycans Pose Roadblocks to the Rapid Development of VRC01-Class Antibodies in an HIV-1-Infected Chinese Donor. Immunity 2016, 44, 939–950. [CrossRef]

- Schommers, P.; Gruell, H.; Abernathy, M.E.; Tran, M.-K.; Dingens, A.S.; Gristick, H.B.; Barnes, C.O.; Schoofs, T.; Schlotz, M.; Vanshylla, K.; et al. Restriction of HIV-1 Escape by a Highly Broad and Potent Neutralizing Antibody. Cell 2020, 180, 471-489.e22. [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Liberatore, R.A.; Guo, Y.; Chan, K.-W.; Pan, R.; Lu, H.; Waltari, E.; Mittler, E.; Chandran, K.; Finzi, A.; et al. VSV-Displayed HIV-1 Envelope Identifies Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Class-Switched to IgG and IgA. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 963-975.e5. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zheng, A.; Baxa, U.; Chuang, G.-Y.; Georgiev, I.S.; Kong, R.; O’Dell, S.; Shahzad-ul-Hussan, S.; Shen, C.-H.; Tsybovsky, Y.; et al. A Neutralizing Antibody Recognizing Primarily N-Linked Glycan Targets the Silent Face of the HIV Envelope. Immunity 2018, 48, 500-513.e6. [CrossRef]

- Scharf, L.; Scheid, J.F.; Lee, J.H.; West, A.P.; Chen, C.; Gao, H.; Gnanapragasam, P.N.P.; Mares, R.; Seaman, M.S.; Ward, A.B.; et al. Antibody 8ANC195 Reveals a Site of Broad Vulnerability on the HIV-1 Envelope Spike. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 785–795. [CrossRef]

- Dubrovskaya, V.; Tran, K.; Ozorowski, G.; Guenaga, J.; Wilson, R.; Bale, S.; Cottrell, C.A.; Turner, H.L.; Seabright, G.; O’Dell, S.; et al. Vaccination with Glycan-Modified HIV NFL Envelope Trimer-Liposomes Elicits Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies to Multiple Sites of Vulnerability. Immunity 2019, 51, 915-929.e7. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Leaman, D.P.; Kim, A.S.; Torrents De La Peña, A.; Sliepen, K.; Yasmeen, A.; Derking, R.; Ramos, A.; De Taeye, S.W.; Ozorowski, G.; et al. Antibodies to a Conformational Epitope on Gp41 Neutralize HIV-1 by Destabilizing the Env Spike. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8167. [CrossRef]

- Pancera, M.; Zhou, T.; Druz, A.; Georgiev, I.S.; Soto, C.; Gorman, J.; Huang, J.; Acharya, P.; Chuang, G.-Y.; Ofek, G.; et al. Structure and Immune Recognition of Trimeric Pre-Fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature 2014, 514, 455–461. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.C. Viral Membrane Fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 690–698. [CrossRef]

- Kong, R.; Xu, K.; Zhou, T.; Acharya, P.; Lemmin, T.; Liu, K.; Ozorowski, G.; Soto, C.; Taft, J.D.; Bailer, R.T.; et al. Fusion Peptide of HIV-1 as a Site of Vulnerability to Neutralizing Antibody. Science 2016, 352, 828–833. [CrossRef]

- Torrents De La Peña, A.; Rantalainen, K.; Cottrell, C.A.; Allen, J.D.; Van Gils, M.J.; Torres, J.L.; Crispin, M.; Sanders, R.W.; Ward, A.B. Similarities and Differences between Native HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein Trimers and Stabilized Soluble Trimer Mimetics. PLOS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007920. [CrossRef]

- Irimia, A.; Sarkar, A.; Stanfield, R.L.; Wilson, I.A. Crystallographic Identification of Lipid as an Integral Component of the Epitope of HIV Broadly Neutralizing Antibody 4E10. Immunity 2016, 44, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Shipulin, G.A.; Glazkova, D.V.; Urusov, F.A.; Belugin, B.V.; Dontsova, V.; Panova, A.V.; Borisova, A.A.; Tsyganova, G.M.; Bogoslovskaya, E.V. Triple Combinations of AAV9-Vectors Encoding Anti-HIV bNAbs Provide Long-Term In Vivo Expression of Human IgG Effectively Neutralizing Pseudoviruses from HIV-1 Global Panel. Viruses 2024, 16, 1296. [CrossRef]

- Leontyev D.S., Urusov F.A., Glazkova D.V., Belugin B.V., Orlova O.V., Mintaev R.R., Tsyganova G.M., Bogoslovskaya E.V., Shipulin G.A. Study of the protective efficacy of CombiMab-2 against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in mice humanised with CD4+ T-lymphocytes. Biological Products. Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment. 2024;24(3):312-321. (In Russ.). [CrossRef]

| Gene | Encoded protein | Function | References |

| 1. Structural genes | |||

| gag (group antigen) | capsid protein (p24) matrix protein (p17) nucleoprotein (p7) p6 |

forms conical capsid covers the conical capsid binds the RNA and forms nucleoprotein/RNA complex facilitates the budding process of virions |

[29,30,31] |

| pol (polyprotein) | reverse transcriptase (RT, p51) ribonuclease H (RNase H, p15), RNase plus RT (p66) protease (PR, p10) integrase (IN, p32) |

transforms viral RNA into DNA degrades the viral RNA processes Gag and Gag-Pol protein precursors into mature viral proteins incorporates viral DNA into the host genome |

[32] |

| env (envelope) | surface protein (SU, gp120) transmembrane protein (TM, gp41) |

contains a domain responsible for binding the virus to the CD4 receptors and co-receptors facilitates the fusion of the viral envelope with the cellular membrane through anchoring |

[24] |

| 2. Regulatory genes | |||

| tat (transactivator of transcription) | transactivator protein (p14) | activates the viral transcription | [33,34] |

| rev (regulator of expression of virion proteins) | RNA splicing regulator (p19) | regulates the nuclear export of unspliced and partially spliced mRNAs from nucleus to the cytoplasm | [35] |

| 3. Auxiliary genes | |||

| nef (negative factor) | negative regulating factor (p27) | modulates cellular signaling, increases the downregulation of the CD4 receptors and MHC I, allows viral replication | [36,37] |

| vif (virion infectivity factor) | viral infectivity protein (p23) | promotes the viral infectivity by preventing restriction factor APOBEC3G from acting | [38,39] |

| vpu | virus protein unique (p16) | causes the degradation of CD4, viral particle release and the arrest of the cell cycle | [38,40] |

| vpr | virus protein r (p15) | facilitates viral infectivity and affects the cell cycle | [41,42] |

| Study | Vaccine (Immunogen) | Location (site) | Target group | Date | Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVTN 305 (NCT05781542) | ALVAC-HIV and AIDSVAX B/E | Thailand (Clade B) | 162 women and men | 2012-2017 | No | [86] |

| HVTN 306 | ALVAC-HIV and AIDSVAX B/E | Thailand (Clade B) | 360 men and women aged 20–40 years |

2012-2017 | No | [87] |

| HVTN 097 (NCT02109354) | ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) and AIDSVAX B/E | South Africa (Clade B/E) | 100 black Africans (men and women) aged 18–40 years | 2012-2013 | No | [88] |

| HVTN 100 (NCT02404311) | ALVAC-HIV (vCP2438) and bivalent subtype C gp120/MF59 | South Africa (Clade C) | 252 men and women | 2015-2018 | No | [89] |

| Study | Vaccine (Immunogen) | Location (site) | Target group | Date | Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VaxSyn | Recombinant envelope glycoprotein subunit (rgp160) of HIV | Canada (Clade B) | 72 adults | 1987 | No | [91] |

| HIVAC-1e | Recombinant vaccinia virus designed to express HIV gp160 | USA (Clade B) | 35 male adults | 1988 | No | [92] |

| VAX003 (VaxGen) (NCT00006327) | AIDSVAX B/E (subtype B - MN; subtype AE - A244 rgp120) | Thailand (Clade B/E) | 2,545 men and women IDUs |

1998-2002 | No | [93] |

| VAX004 (VaxGen) (NCT00002441) | AIDSVAX B/B (subtype B - MN and GNE8 rgp120) | North America (Clade B) | 5,417 MSM and 300 women |

1999-2003 | No | [94] |

| STEP HVTN502 | Ad5 expressing subtype B Gag (CAM-1), Pol (IIIB), Nef (JR-FL) | North America the Caribbean South America, and Australia (Clade B) | 3,000 MSM and heterosexual men and women |

2004-2007 | No | [95] |

| Phambili HVTN 503 (NCT00413725) | Ad5 expressing subtype B Gag (CAM-1), Pol (IIIB), Nef (JR-FL) | South Africa (Clade C) | 801 adults | 2003-2007 | No | [96] |

| RV 144 (NCT00223080) | ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) expressing Gag and Pro (subtype B LAI), CRF01_AE gp120 (92TH023) linked to transmembrane anchoring portion of gp41 (LAI) AIDSVAX B/E Aluminium hydroxide |

Thailand (Clade B) | 16,402 community-risk men and women |

2003-2009 | Yes 31% | [97] |

| HVTN 505 (NCT00865566) | 6 DNA plasmids - subtype B Gag, Pol, Nef and subtypes A, B and C Env 4 rAd5 vectors - subtype B Gag/Pol and subtypes A, B and C Env |

United States (Clade B) | 2,504 men or transgender women who have sex with men | 2009-2017 | No | [98] |

| Uhambo HVTN 702 (NCT02968849) | ALVAC-HIV (vCP2438) expressing Gag and Pro (subtype B LAI), subtype C gp120 (ZM96.C) linked to transmembrane anchoring portion of gp41 (LAI) | South Africa (Clade C) | 5,400 men and women | 2016-2021 | No | [99] |

| IMBOKODO HVTN 705 (NCT03060629) | Ad26.Mos4.HIV Subtype C gp140 |

Sub-Saharan Africa (Clade C) | 2600 women | 2017-2022 | No data | [100] |

| MOSAICO HVTN 706 (NCT03964415) | Ad26.Mos4.HIV Subtype C gp140 or bivalent gp140 (subtype C/Mosaic) |

Europe North America and South America (Clade C) | 3800 MSM and transgender persons | 2019-2024 | No data | [101] |

| PrEPVacc (NCT04066881) | DNA-HIV-PT123 plasmid and AIDSVAX B/E or DNA-HIV-PT123 plasmid with trimeric CN54gp140; MVA-CMDR (Chang Mai double recombinant) and trimeric CN54gp140 Concurrent PrEP administration of either TAF/FTC or TDF/FTC |

Uganda, Tanzania, Mozambique, Republic of South Africa (Clade C) | 1668 Adults Men and Women | 2020-2023 | No data | [102] |

| Trial | Name | Hypothesis | Year | Target group | Site | Vaccine Candidates | Immunogene design | Vaccine Manufacturer | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAVI G002 NCT05001373 |

A Phase 1 Study to Evaluate the Safety A Phase I Trial to and Immunogenicity of eOD-GT8 and Immunogenic 60mer mRNA Vaccine (mRNA-1644) delivered by an m and Core-g28v2 60mer mRNA Vaccine negative adults (mRNA-1644v2-Core |

Sequential vaccination by a germline-targeting prime followed by directional boost immunogens can induce specific classes of B-cell responses and guide their early maturation toward broadly neutralizing antibody (bnAb) development through an mRNA platform |

2021- 2023 | 56 adults ages 18 to 50 | 4 sites in the US (Atlanta; San Antonio; Seattle; Washington, DC) | Two experimental HIV vaccines based on messenger RNA (mRNA) platform: 1. eOD-GT8 60mer mRNA Vaccine (mRNA-1644) 2. Core-g28v2 60mer mRNA Vaccine (mRNA-1644v2-Core) |

IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center (NAC) at Scripps Research |

Moderna | [108] |

| IAVI G003 NCT05414786 |

A Phase I Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of eOD-GT8 60mer delivered by an mRNA platform in HIV negative adults | eOD-GT8 60mer delivered by an mRNA platform in HIV negative adults will induce immune responses in African populations as was seen in IAVI G001, which demonstrated this recombinant protein (eOD-GT8 60mer) safely induced immune responses in 97% of recipients, who were healthy U.S. adults | 2022- 2023 | 18 healthy, HIV- negative adults | 2 sites: Kigali, Rwanda, and Tembisa, South Africa | One experimental HIV vaccine based on messenger RNA (mRNA) platform: 1. eOD-GT8 60mer delivered by an mRNA Vaccine platform (mRNA- 1644) |

IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center (NAC) at Scripps Research |

Moderna | [109] |

| HVTN 302 NCT05217641 |

A Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of BG505 MD39.3, BG505 MD39.3 gp151, and BG505 MD39.3 gp151 CD4KO HIV Trimer mRNA Vaccines in Healthy, HIV-uninfected Adult Participants | The BG505 MD39.3 soluble and membrane-bound trimer mRNA vaccines will be safe and well-tolerated among HIV-uninfected individuals and will elicit autologous neutralizing antibodies | 2022- 2023 | 108 adults ages 18 to 55 years | 11 sites in the US (Birmingham; Boston; Los Angeles; New York City; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; Rochester; Seattle) |

Three experimental HIV vaccines based on messenger RNA (mRNA) platform: 1. BG505 MD39.3 mRNA 2. BG505 MD39.3 gp151 mRNA 3. BG505 MD39.3 gp151 CD4K0 mRNA |

Scripps Consortium for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Development (CHAVD) and IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center (NAC) at Scripps Research |

Moderna | [110] |

| Trial | Phase | Registry Identifier | Result | Status | Last Update | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGS-004 (personalized therapeutic vaccine utilizing patient-derived dendritic cells and HIV antigens) | IIb | NCT00672191 | Induction of CD4 and CD8, reduction of VL, One severe adverse event | Completed | 2013 | [114] |

| Autologous HIV-1 ApB DC Vaccine | I/II | NCT00510497 | Safe and immunogenic Reduction of HIV blood reservoir | Completed | 2016 | [115] |

| Dendritic cell vaccine (DCV-2) | I/II | NCT00402142 | Safely induced marginal immune responses, whereas markedly increased Vacc-C5-induced regulatory T cell | Completed | 2014 | [116] |

| Dendritic cells loaded with HIV-1 lipopeptides | I | NCT00796770 | Safe and showed few CD8+ T cell responses | Completed | 2017 | [117] |

| Trial | Phase | Registry Identifier | Result | Status | Last Update | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vacc-4x | II | NCT00659789 | Induction of CD4 and CD8, reduction of VL, One severe adverse event | Completed | 2017 | [125] |

| VAC-3S | I/II | NCT01549119 | Safe and immunogenic Reduction of HIV blood reservoir | Completed | 2015 | [126] |

| Vacc-C5 | I/II | NCT01627678 | Safely induced marginal immune responses, whereas markedly increased Vacc-C5-induced regulatory T cell | Completed | 2014 | [127] |

| AFO-18 | I | NCT01141205 | Safe and showed few CD8 T cell responses | Completed | 2013 | [128] |

| HIV-v | I | NCT01071031 | Safe and can elicit T- and B-cell responses that significantly reduce viral load. | Completed | 2012 | [129] |

| Trial | Phase | Registry Identifier | Result | Status | Last Update | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad26.Mos.HIV + MVA-Mosaic | II | NCT02919306 | Generated robust immune responses, but did not lead to viremic control after treatment interruption. | Completed | 2022 | [135] |

| MAG pDNA vaccine +/- IL-12 | I | NCT01266616 | Elicited CD4+ but not CD8+ T-cell responses to multiple HIV-1 antigens. | Completed | 2015 | [136] |

| PENNVAX-B (Gag, Pol, Env) + electroporation | I | NCT01082692 | Strong induction of CD8 T cell responses | Completed | 2012 | [137] |

| Trial | Phase | Registry Identifier | Result | Status | Last Update | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC-HIV04 Comparison of Dendritic Cell-Based Therapeutic Vaccine Strategies for HIV Functional Cure |

I | NCT03758625 | Not reported | Active | 2024 | [139] |

| GCHT01 | I | NCT01428596 | Not reported | Unknown | 2019 | [140] |

| GTU-MultiHIV B-clade + MVA HIV-B (DNA + viral vector vaccines) | II | NCT02972450 | Not reported | Terminated | 2019 | [141] |

| THV01 (lentiviral vector-based therapeutic vaccine) | I/II | NCT02054286 | Not reported | Completed | 2019 | [142] |

| Ad26.Mos4.HIV + MVA-Mosaic or clade C gp140 + mosaic gp140 |

I | NCT03307915 | Not reported | Completed | 2022 | [143] |

| Neutralizing activities of different bNAbs | ||

| Targets of bNAbs | Functions of target | bNAbs |

| V3-glycan | Involved in the initial interaction and resulting fusion between the Env protein and a coreceptor in the host cell membrane. | 10-1074 |

| 10-1074-LS | ||

| 10-1074-LS-J | ||

| PGT121 | ||

| PGT121LS | ||

| PGT121.414.LS | ||

| DH270 | ||

| PGT128 | ||

| PGT135 | ||

| CD4 binding site | Binds to the CD4 receptor on the surface of the host cell, causing structural changes that allow the gp120 protein to bind to the host cell membrane. | 3BNC117 |

| 3BNC117-LS | ||

| 3BNC117-LS-J | ||

| VRC01 | ||

| VRC01-LS | ||

| VRC07-523LS | ||

| 12A12 | ||

| BANC131 | ||

| CH103 | ||

| CH235.12 | ||

| CH31 | ||

| N49P7 | ||

| NIH 45i | ||

| PG04 | ||

| VRC07 | ||

| VRC13 | ||

| V1/V2-glycan | Involved in a structural change to the Env protein enabling HIV to fuse and infect the host cell. | CAP256V2LS |

| PGDM1400 | ||

| CH01-04 | ||

| PG16 | ||

| PGT141-145 | ||

| gp41 MPER | Helps disrupt viral membrane during fusion of HIV with host cell. | 10E8.4 |

| 2F5 | ||

| 4E10 | ||

| 10E8VLS | ||

| Fusion peptide (FP) | Inserts into and disrupts the host cell membrane, allowing HIV to release genetic material into the cell. | ACS202 |

| VRC34.01 | ||

| gp120-41 interface | Where gp120 and gp41 meet; involved in structural changes to the Env protein during entry into the host cell. | 35022 |

| LN02 | ||

| SANC 195 | ||

| 8ANC195 | ||

| PGT151 | ||

| 3BC176 | ||

| 3BC315 | ||

| gp120 Silent face | A region of the Env protein that is heavily sugar-coated and has little functional role in virus entry. | SF12 |

| VRC-PG05 | ||

| bNAbs combinations: Two or more antibodies in a regimen | |||||||

| Regimen | Status | Route | Research Institution | Trial Name | |||

| 10-1074 + 3BNC117 | Phase 1, Completed | IV | Rockefeller University | YCO-0899 | |||

| 10-1074-LS + 3BNC117-LS | Phase 1, Ongoing | IV, SC | Rockefeller University | YCO-0971 | |||

| 10-1074-LS-J + 3BNC117-LS-J | Phase 1/2, Ongoing | IV, SC | IAVI, Rockefeller University, University of Washington | IAVI C100 | |||

| PGT121 + VRC07-523LS + PGDM1400 | Phase 1, Completed Phase 1/2a, Ongoing | IV | BIDMC, IAVI, NIAID | IAVI T002 IAVI T003 | |||

| PGT121 + PGDM1400 + 10-1074 + VRC07-523LS | Phase I, Ongoing | IV | NIAID | HVTN 130/ HPTN 089 | |||

| PGT121.414.LS + VRC07-523LS | Phase I, Ongoing | IV, SC | NIAID | HVTN 136/ HPTN 092 | |||

| VRC07-523LS + CAP256V2LS | Phase I, Ongoing | SC | NIAID | HVTN 138/ HPTN 098 | |||

| CAP256V2LS + VRC07-523LS + PGT121 | Phase I, Ongoing | IV, SC | CAPRISA, NIAID | CAPRISA 012B | |||

| CombiMab1 (AAV9-vectors encoding bNAbs: N6 + 10E8 + 10-1074) | Preclinical | IM | CSP FMBA | - | |||

| CombiMab2 (AAV9-vectors encoding bNAbs: VRC07-523 + PGDM1400 + 10-1074) | Preclinical | IM | CSP FMBA | - | |||

| Multispecific: Parts of two or more antibodies on a single antibody | |||||||

| Regimen | Status | Route | Research Institution | Trial Name | |||

| SAR441236 (CD4bs specificity of VRC01-LS V1/V2 glycan-directed binding of PGDM1400 gp41 MPER binding of 10E8v4) |

Phase I, Planned | IV | Sanofi, NIAID | HVTN 129/ HPTN 088 | |||

| 10E8.4/iMab | Phase I, Ongoing | IV, SC | ADARC | AAAS1239 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).