1. Introduction

Nucleotides have the function of storing energy from food, and they are components of nucleic acids. They are indispensable for all cells. In recent decades, another function of nucleotides, mainly adenosine and guanosine, has been discovered as essential molecules for cell signaling in eukaryotic and prokaryotic (bacteria and archaea) cells, acting as a second messenger. In bacteria, cell signaling by nucleotides has been associated with cellular processes regulating biofilm formation, sporulation, cell differentiation, cell wall stability, and virulence [

1]. The nucleotides involved in cell signaling are structurally different from conventional nucleotides, mainly cyclic mononucleotides or dinucleotides, such as cyclic AMP, and others, such as cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP) or cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP).

Cyclic dinucleotides are formed from conventional mononucleotides; two ATP molecules are substrates to produce c-di-AMP by specific enzymes diadenylate cyclase (DAC); in the case of c-di-GMP, GTP or GDP are the substrates, and the ATP molecules are the phosphate group donors by specific enzymes diguanylate cyclase (DGC). It is also similar to the case of the pppGpp or ppGpp alarms [

2]. The bacterium regulates the production levels of cyclic di-nucleotides (c-di-nucleotides) for cell signaling, and the quenching of nucleotide signaling is due to their degradation. Degradation of c-di-nucleotides occurs by c-di-nucleotide-specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs).

In general, the bacterium detects environmental changes such as low nutrients, pH, osmolarity, stress, etc., and as a response, the bacterium switches on the c-di-nucleotide signaling. Sensing environmental changes drives the synthesis or degradation of c-di-nucleotides to produce high or low concentrations of c-di-nucleotides that can trigger the switching on or off of cellular processes. The c-di-nucleotides produced bind to specific bacterial proteins (receptor proteins), which perform a specific function. In this review, we will address several topics of c-di-nucleotide signaling in bacteria. First, we will discuss c-di-GMP and its variants, then cAMP and c-di-AMP, and finally, alarmones.

1. Similarities and differences between c-di-nucleotides

The second messenger initially described was cyclic AMP (cAMP); in bacteria, it has been reported that cAMP is involved in biofilm formation, virulence as like as central metabolism [

3,

4], but cAMP has also been described in eukaryotic cells. The substantial difference between bacterial signaling and eukaryotic cells is that cAMP signals directly bind to target proteins to function in bacteria. In contrast, cAMP requires intermediates of the proprotein kinase A (PKA) complex in eukaryotic cells.

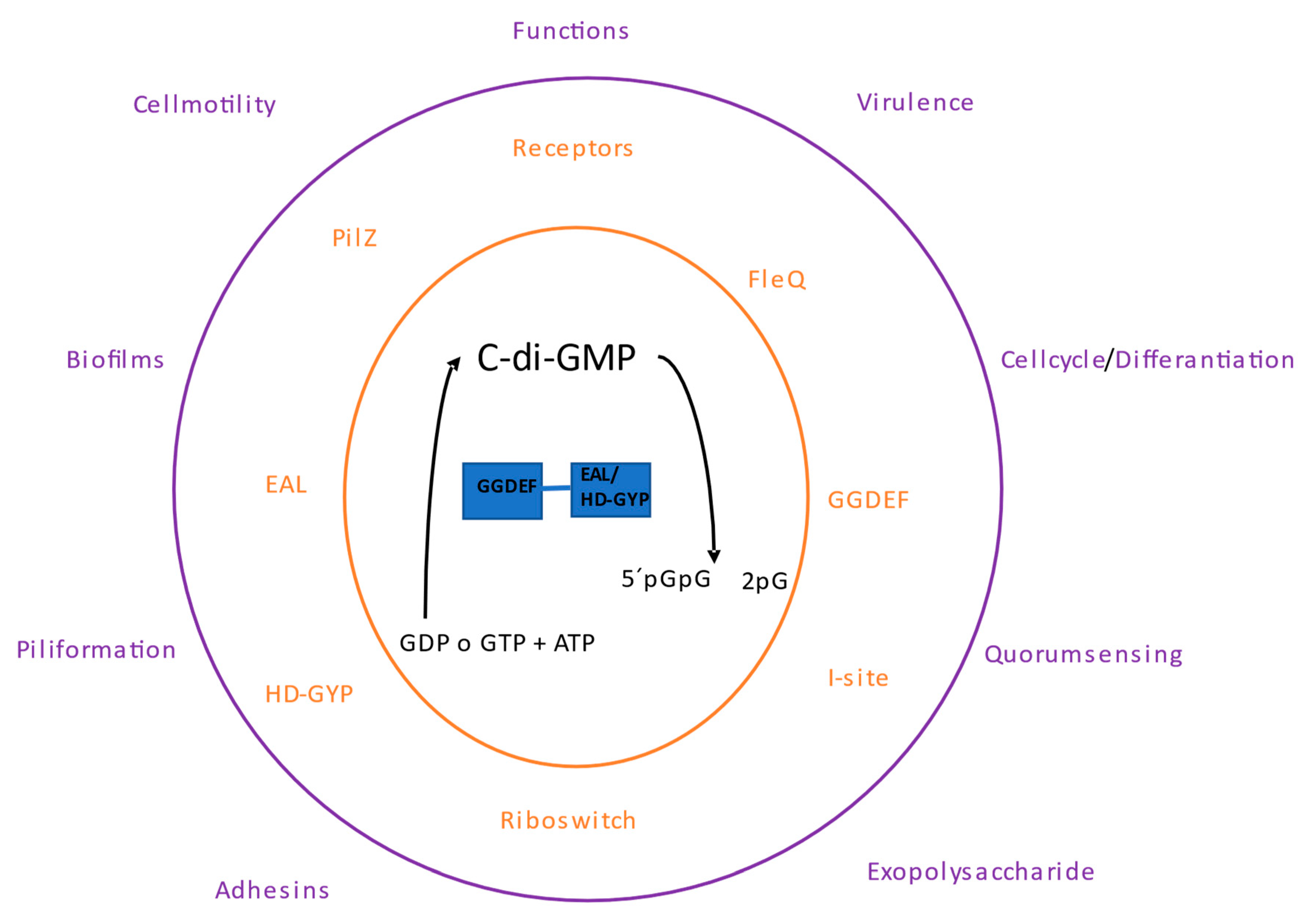

Subsequently, the second messenger, c-di-GMP, was discovered. From studies of bacterial genomes, it has been found that diguanylate cyclase (DGCs) enzymes have a conserved domain known as the "GGDEF" domain [

5]. In the case of c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase (PDE), enzymes that degrade c-di-GMP have a highly conserved enzymatic domain known as the "EAL" domain [

6]. However, a second domain with c-di-GMP degrading activity has been determined in PDEs corresponding to the HD-GYP domain. In most bacteria, enzymes that participate in c-di-GMP synthesis/degradation have GGDEF, EAL, and HD-GYP domains, in which they are widely conserved, and in some bacteria have up to dozens of enzymes associated with the synthesis/degradation of c-di-GMP [

7].

The c-di-AMP was the next cyclic dinucleotide discovered [

8]. The c-di-AMP is found in many species of bacteria and archaea. The deadenylate cyclase (DAC) enzymes are involved in the synthesis of c-di-AMP, and its degradation is by specific PDEs, whose molecular feature is that they have a DAC domain in DAC enzymes and a DHH-DHHA1 domain in PDE enzymes, and c-di-AMP degradation by PDE enzymes produces pApA [

9]. There are differences between c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP. For example, one of the few genes that encode DAC enzymes is present in most bacteria. In contrast, genes to DGC enzymes are more abundant and variants, and the other is that c-di-AMP participates in the process of bacterial growth that is essential in many bacterial species but not all [

10].

Gram-positive bacteria, such as the phyla Actinobacteria and Firmicutes, frequently have DAC domain-containing proteins. On the other hand, members of phyla Fusobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chlamydiae, Cyanobacteria, and the class Deltaproteobacteria, all Gram-negative bacteria, possess DAC domain proteins. As was mentioned, one DAC enzyme is present in most organisms. However, Bacillus spp. and Clostridium are bacteria that have two or three DAC enzymes. Contrary to c-di-GMP, most organisms can have multiple DGC enzymes.

The c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP synthesize- or degrade-enzymes are distributed in a manner different between bacteria. The phylum Proteobacteria are especially abundant in c-di-GMP synthesize-enzymes, while the classes Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Gammaproteobacteria have c-di-GMP synthesize-enzymes but they do not possess a c-di-AMP signaling system. Instead, both enzymes to synthesize c-di-GMP and c-di-AMP are present in the class Deltaproteobacteria. In contrast, c-di-GMP-producing enzymes are absent in phyla Fusobacteria and Bacteroidetes and in the order Chlamydiales [

11]. On the other hand,

Clostridium,

Streptomyces spp.,

Mycobacterium,

Listeria, and

Bacillus, members of the phyla Actinobacteria and Firmicutes, contain both cellular signaling systems, whereas

Corynebacterium spp.,

Streptococcus, and

Staphylococcus have the c-di-AMP system but not the c-di-GMP system. Although the GGDEF domain is representative of the DGCs, it has been reported that the c-di-AMP synthesize- or degrade-enzymes in

Streptococcus spp. and

Staphylococcus have the degenerate GGDEF domains with the capacity to synthesize c-di-AMP or the YybT protein of

B. subtilis that has GGDEF domain-containing PDE activity (GdpP) [

12].

1. The c-di-GMP nucleotide

The genomic arrangement of the EAL and GGDEF domains shows that they are most frequently present in multidomain proteins. The first protein identified with DGC and PDE activity was from

Gluconacetobacter xylinus. This protein contains GGDEF-EAL domains arranged in tandem, indicating that it is a bifunctional protein with DGC or PDE activities [

13]. The functionality of these bifunctional proteins is by differential regulation dependent on the environment, at any given time, one enzyme activity will be prevalent over the other (

Figure 1).

1.1. Types of c-di-GMP Receptors

The c-di-GMP receptors/effectors proteins may have the GGDEF, EAL, and HD-GYP domains. However, some domains are inactive as those c-di-GMP receptors with inactive EAL or likely HD-GYP domains. Other receptor/effector proteins with different domains including PilZ and I-site receptors. Among the receptor proteins, several transcriptional regulators have been found, as well as several types of proteins with diverse functions, and non-proteins such as riboswitches also function as c-di-GMP receptors.

The

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PilZ protein, involved in pili formation, is a c-di-GMP receptor in which the PilZ domain has a high affinity to c-di-nucleotide under in vitro conditions. Other proteins possessing this domain are the BcsA protein of

G. xylinus, the YcgR of

Escherichia coli [

14], the DgrA of

Caulobater crescentus, and the PlzC and PlzD of

Vibrio cholerae [

15].

The

C. crescentus response regulator PopA protein is a GGDEF-domain c-di-GMP receptor, which is involved in the cell cycle [

16]; the

Myxococcus xanthus hybrid histidine kinase SgmT and the CdgA receptor are also GGDEF-domain c-di-GMP receptors and the CdgA receptor participates in entry of predatory bacterium

Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus to precells [

17].

The same applies to proteins with EAL domains but without PDE activity; these proteins can bind c-di-GMP. Examples are

P. aeruginosa FimX, associated with motility by type IV pilus, and LapD from

Pseudomonas fluorescens with a high affinity for binding cyclic di-nucleotide [

18].

On the other hand, riboswitches are noncoding mRNA with specific secondary structures and that can recognize molecular ligands. Upon binding of a ligand to riboswitches, the secondary structure of the mRNA changes, leading to changes in transcription, mRNA splicing, or downstream gene translation [

19]. GEMMS are riboswitches that specifically recognize c-di-GMP; the c-di-GMP-induced RNA splicing is another type of riboswitch [

20].

1.1. Processes of c-di-GMP signaling

Cell differentiation and biofilm formation were the first processes involved in c-di-GMP signaling. Subsequently, other bacterial phenotypes were described, such as the virulence of

V. cholerae, bacterial survival, predatory behaviors, multicellular development, the transmission of obligate intracellular pathogens, antibiotic production in streptomycetes, the transition between motile and sessile lifestyles, heterocyst formation in cyanobacteria, lipid metabolism and transport in mycobacteria, survival to nutritional stress [

21,

22] and swimming, such as swarming, contracting and gliding motility in several Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Spirochaetes, and Cyanobacteria [

23].

1.1. Cell motility

The transition from motility to non-motility involves several cellular states; first, a cell requires a surface to adhere temporarily and remain attached by its adhesive components. Subsequently, the cell must inhibit motility, which is where c-di-GMP comes into play. Elevated intracellular levels of c-di-GMP favor a strong counterclockwise (CCW) rotation. CCW induces smooth swimming and inhibits bacterial propagation on semisolid agar. The motility control mechanism by c-di-GMP is via the YcgR receptor, which c-di-GMP binds to and causes flagellum quenching, and this has been supported because a mutation in

ycgR gene restores bacterial motility on semisolid agar [

24]. Signaling of c-di-GMP through the YcgR receptor is direct, as this receptor interacts with the flagellar motor. In addition, c-di-GMP can block the synthesis of new flagella in some bacteria, such as the case of

P. aeruginosa, the FleQ protein (the first-factor regulating flagellar gene expression) is regulated in its function by c-di-GMP, which controls the expression of the flagellar regulon [

25], causing flagellar gene switch-off.

1.1. Regulation of Biofilms

The c-di-GMP can induce biofilm formation in different modalities, e.g., films in a liquid medium or on agar plates with dry, rough, and red colony morphotypes. One of the first evidence is that in

P. aeruginosa, there is a relationship between the high biofilm formation and the levels of c-di-GMP [

26], indicating its involvement. Posteriorly, it has been observed that in adhesion to the abiotic surface, the first step of biofilm formation, the c-di-GMP participates by the induction of adhesion molecules. Furthermore, it has now been documented that c-di-GMP can regulate all components of the extracellular matrix of a biofilm, including various adhesive pili, non-fimbrial adhesins, exopolysaccharides, and extracellular DNA [

27], and the control by c-di-GMP is transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational levels.

1.1. Pili as c-di-GMP targets

Pili or fimbriae are formed by protein that are assamble to build non-flagellar appendages on the external surface of bacteria. Fimbriae have characteristics of adhesion to abiotic and biotic surfaces, which are associated with biofilm formation, and c-di-GMP is involved in the adhesion of biofilm, suggesting a possible regulation of fimbriae by this c-di-nucleotide. The type 3 fimbriae of

Klebsiella pneumoniae helps the biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces or human extracellular matrix-coated surfaces. The DGC YfiN activity increases the c-di-GMP levels, which c-di-GMP induces the transcription of the type 3 fimbriae mRNA, while MrkJ PDE activity reduces the c-di-GMP levels generating down-regulates the type 3 fimbriae expression. The mechanism of c-di-GMP to regulate the expression of type 3 fimbriae is by linkage c-di-GMP to the transcriptional factor MrkH, since MrkH has a PilZ domain, making c-di-GMP-MrKH able to interact with the promoter of type 3 fimbriae and carry out its expression [

28].

Another type of fimbriae is the Cup, which is also a target of c-di-GMP.

P. aeruginosa has five Cup types (A to E); Cups participate in biofilm formation because they modify cell adhesive properties. C-di-GMP can regulate the transcription of all Cup fimbriae except CupE. Some

P. aeruginosa strains from cystic fibrosis patients with a variant small colony phenotype show increased YfiN and MorA DGCs activity to produce high c-di-GMP levels and expression of CupA fimbriae [

29].

On the other hand, type IV pili is very diverse and ubiquitous. Type IV pili is associated with twitching mobility because this pili has the capacity to polymerize and retract. Type IV pili and twitching mobility are essential for the maturation of biofilm formation. In

P. aeruginosa, c-di-GMP signaling regulates type IV pili biogenesis and twitching motility [

30].

1.1. Adhesins as a target of c-di-GMP

In addition to pili, non-fimbrial adhesins contribute to biofilm formation. The non-fimbrial adhesive protein LapA from

Pseudomonas putida and

P. fluorescens participates in bacteria binding to the surface and cell-cell interaction, stabilizing the biofilm. The type I secretion system transports the LapA protein to the outside of the cell; subsequently, LapA is proteolytically processed at its N-terminus by the periplasmic protease LapG. The proteolytic activity of LapG is regulated by the transmembrane protein LapD. Low levels of c-di-GMP regulate LapD activity since LapD has a degenerate EAL domain [

18].

1.1. Exopolysaccharide as a target of c-di-GMP

The polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PAG; Poly-1,6-N-acetylglucosamine; PIA; PNAG) is a component of the biofilm matrix, and a wide variety of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria produce PAG. In

E. coli,

Yersinia pestis, and

Pectinobacterium atrosepticum, c-di-GMP activates the PAG biosynthesis [

31]. In

E. coli K-12, two DGCs, DosC (YddV) and YdeH, are involved in PAG-dependent biofilm formation, as DosC affects the transcription of the pgaABCD operon and YdeH stabilizes the transmembrane protein glycosyltransferase PgaD; the mechanism of PAG synthesis is by binding of c-di-GMP to PgaC and PgaD proteins (both transmembrane glycosyltransferases) leading to their interaction and stimulation of glycosyltransferase activity [

32].

Interestingly, PAG is also produced in

Staphylococcus epidermidis and

Staphylococcus aureus. However, the mechanism of PAG biosynthesis is independent of c-di-GMP. In staphylococci, signaling by c-di-GMP does not exist, as only proteins with functional GGDEF domains, GdpS, are present, but no produces c-di-GMP [

33].

1.1. Alginate polysaccharides, Pel and Psl as targets of c-di-GMP

Several bacteria have the capacity to produce alginate and the polysaccharides Pel and Psl. However, c-di-GMP is involved in the production of these exopolysaccharides, and it has been studied in

P. aeruginosa.

P. aeruginosa non-mucoid biofilms have an extracellular matrix of Pel and Psl polysaccharides. While the genetic capacity to produce Pel polysaccharides appears ubiquitous among all

P. aeruginosa strains, it has been shown that not all

P. aeruginosa strains can produce Pel polysaccharides. It has been shown that not all strains can produce the

psl operon. C-di-GMP positively induces the transcription of the exopolysaccharides Pel and Psl by the REC-GGDEF-DGC response regulator WspR [

34].

Moreover, pel and psI can be promoted their transcription by the transcriptional regulator FleQ. FleQ is a c-di-GMP receptor, which the transcription of pel and psl is dependent on c-di-GMP. In the absence of c-di-GMP, FleQ forms a complex with the ATP-binding accessory protein FleN and binds to sites both upstream and downstream of the pel promoter to inhibit transcription. In the presence of c-di-GMP, FleQ binds to c-di-GMP and separates from the ATP-binding accessory protein FleN, triggering the transcriptional activity of pel [

35]. In addition, feedback exists between c-di-GMP and Psl, as Psl can elevate c-di-GMP levels via the SiaD and SadC DGCs [

36].

Finally,

P. aeruginosa mucoid strains also have exopolysaccharide alginate. The polymerization or transport of alginate is by Alg44 (PA3542) protein; this protein has a PilZ domain and is regulated by c-di-GMP [

37].

C-di-GMP can control the biofilm formation at the transcriptional level. For example, seven DGCs and four PDEs regulate the rough colony formation in

V. cholerae. Expression of Vibrio polysaccharide (VPS) is the prominent feature that confers a rough colony. The positive transcriptional regulators VpsR and VpsT activate the expression of Vps genes. These transcriptional factors, VpsT and VpsR, are c-di-GMP receptors, and when the c-di-nucleotide binds to them, they are activated for transcription of Vps polysaccharides [

38].

Furthermore, there is a relationship between low levels of c-di-GMP and biofilm. For example, extracellular DNA produced by cell lysis is induced by low levels of c-di-GMP, and eDNA is necessary for mature biofilm structures [

39]. Another action of low levels of c-di-GMP occurs in motile cells on the biofilm surface, which become sessile cells at low levels of c-di-GMP.

1.1. Cyclic di-GMP and quorum sensing

Quorum sensing can negatively regulate biofilm formation, and c-di-GMP induces biofilm formation. In

V. cholerae biotype El Tor, high cell density levels produce a high concentration of the quorum-sensing autoinducer, triggering the expression of HapR, the primary regulator of quorum sensing. HapR regulates the expression of at least 14 of the 52 GGDEF/EAL domain proteins and 4 HD-GYP domain proteins, leading to an overall reduction of the intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP [

40] and thus inhibiting biofilm formation.

1.1. Cellulose biosynthesis

The first process discovered regulated by c-di-GMP was cellulose biosynthesis in the bacterium

G. xylinus. The cellulose synthase enzymes have a PilZ domain at the C-terminal end, suggesting that these enzymes can be allosterically regulated by c-di-GMP. Indeed, it has been observed that the PilZ domain of

G. xylinus cellulose synthase can join c-di-GMP, increasing the activity of this enzyme. In vitro, cellulose biosynthesis has been shown to require c-di-GMP, UDP-glucose, and membrane fractions of

G. xylinus [

41].

1.1. Cell cycle regulation and differentiation

The freshwater bacterium

C. crescentus evolves morphologically from a sessile stalked cell to a free-motile swarmer cell. Swarmer cells, at each cell pole, possess a flagellum and an adhesive pili, and stalked cells promote adhesion to the surface. The process of cell differentiation begins within a spoke cell during the initiation of the cell cycle. In a stalked cell, an easy, symmetric cell division occurs to produce a swarmer cell; after cell division, the stalked cell initiates a new round of replication. In a stalked cell, there are high levels of c-di-GMP, and it changes during the transition from a swarmer cell to a stalked cell [

42]. During this transition process, two DGCs, PleD and DgcB, drive the differentiation of the stalked cell to a swarmer cell through holdfast biogenesis and stalk initiation and elongation [

43], which appear to be the proteins responsible for c-di-GMP synthesis.

1.1. Cell differentiation in multicellular bacteria

C-di-GMP is involved in cell differentiation and multicellular bacteria. In cell differentiation, the cyanobacterium

Anabaena, in conditions of nitrogen starvation, generates heterocysts that are specialized cells with the function of carrying out oxygen-sensitive nitrogen fixation, a process opposite to photosynthesis; the heterocysts supplement nitrogen to the multicellular filaments. This process of heterocyst formation is associated with c-di-GMP because the inactivation of the All2874 protein, which is a GGDEF domain DGC, inhibits this process [

44].

In the case of multicellular bacteria,

Streptomyces coelicolor starts its life cycle from the germination of a spore to produce a branched vegetative filament, which eventually forms a network of multinucleate aerial hyphae (mycelium). Overexpression of CdgA, a DGC enzyme, blocks aerial hyphae formation and generates a bald colony phenotype. The c-di-GMP also affects mycelium formation in

S. coelicolor. It may also affect pigmentation and production of the antibiotic actinorhodin [

45].

1.1. Virulence

The c-di-GMP signaling pathways are associated with bacterial virulence. In

V. cholerae, the first evidence of the role of c-di-GMP in virulence was that low levels of c-di-GMP induce elevated cholera toxin expression in vitro, while high levels of c-di-GMP attenuate virulence in murine cholera [

46]. This observation helps to understand that low levels of c-di-GMP are required for acute infection. Recent studies support this view since pathogenic bacteria have few DGC proteins, and the elimination of the DGCs function demonstrates that c-di-GMP signaling is not necessary for virulence, as is the case of

Yersinia pestis [

21]. The infection of spirochete

Borrelia burgdorferi in mice to produce Lyme disease is generated when the bacterium has deleted its single DGC [

47].

Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, with the elimination of all GGDEF domain genes, reduces its infection in mice [

48]. Similar occurs in

Brucella melitensis [

49]. In addition, high levels of c-di-GMP inhibit acute infection of

B. burgdorferi,

Y. pestis, and

Francisella novicida [

50].

1.1. Cyclic di-GMP as an immunomodulator

c-di-GMP inhibits cell proliferation in the human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line, the human CD4 T-lymphoblast cell line Jurkat [

51], and human colon cancer cells [

52]. The inhibition of cell proliferation is explained by the binding of c-diGMP to the p21ras protein (member of the Ras superfamily of GTPases) [

51], suggesting that the c-di-nucleotide is antitumoural.

c-di-GMP is an immunostimulator that reduces the effects of

S. aureus infection and bacterial pneumonia caused by

Streptococcus pneumoniae or

K. pneumoniae in mice [

53]. C-di-GMP can recruit neutrophils, monocytes, and granulocytes. The application of c-di-GMP as an adjuvant enhances the immune response against mutant staphylococcal enterotoxin, pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA),

S. aureus agglutination factor A (ClfA), and pneumolysin toxoid antigens. This demonstrates that c-di-GMP can be used as an immunotherapeutic agent.

Finally, the immunological effects of c-di-GMP are attributable to binding to the cytoplasmic domain of the transmembrane protein STING [

54]; c-di-GMP-STING binding activates TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and this kinase activates interferon regulatory transcription factor 3 (IRF3) resulting in the production of type I interferons [

54].

1. The novel cyclic dinucleotide second messengers

There are other types of signal nucleotides with structures different from those mentioned above, such as cyclic AMP-GMP and cyclic AMP-AMP, and cyclic trinucleotides, such as cyclic AMP-AMP-GMP (cAAG) and cyclic AMP-AMP-AMP (cAAA). These nucleotides are synthesized by a new superfamily of proteins called cGAS/DncV-like nucleotidyltransferases (CD-NTases), and these CD-NTases have been observed to be conserved in all bacteria. Signaling of these nucleotides can activate effector proteins, such as DNA endonucleases, transmembrane pore-forming proteins, patatin-like phospholipases, and proteases. These effector proteins provide antiphage immunity [

55], protecting bacteria against bacteriophage infection.

The hybrid dinucleotide between AMP and GMP is cyclic AMP-GMP. Cyclic AMP-GMP is produced by the CD-NTase DncV [

56], and the homologous DncV is present in a subset of proteobacteria, including the diarrhoeagenic

E. coli strain DEC8D. In

V. cholerae El Tor, the dncV gene is located in the pandemic island 1 (Vsp-1) of vibrio, which is believed to have contributed to the biotype that caused the pandemic. Elimination of

dncV gene in V

. cholerae inhibits intestinal colonization in a mouse model because DncV represses chemotaxis.

Another system of bacterial protection against nucleic acid entry events is the CRISPR-Cas system; this system is considered a mechanism of immunity. In the case of the CRISPR-Cas type III system, which destroys transcription-dependent DNA, it has been discovered that a component protein of the system, Cas10, considered to be a nuclease that cleaves single-stranded DNA, during the process of cleavage of foreign DNA by Cas10, this protein also synthesizes a cyclic oligoadenylate (cOA, 4 adenine units). cOA binds to Csm6/Csx1 proteins with ribonuclease activity (also belonging to the CRISPR-Cas system) to degrade RNA non-specifically; it can also bind to other RNases such as RelE and PIN and to DNAases to cleave RNA and bacterial DNA. cOA can be toxic to bacteria, so it is degraded by CRISPR-associated nuclease 1 (Crn1), which cleaves cOA specifically into di-adenylate products in a linear fashion to quench cOA-activated effector proteins [

57].

1. The cAMP nucleotide

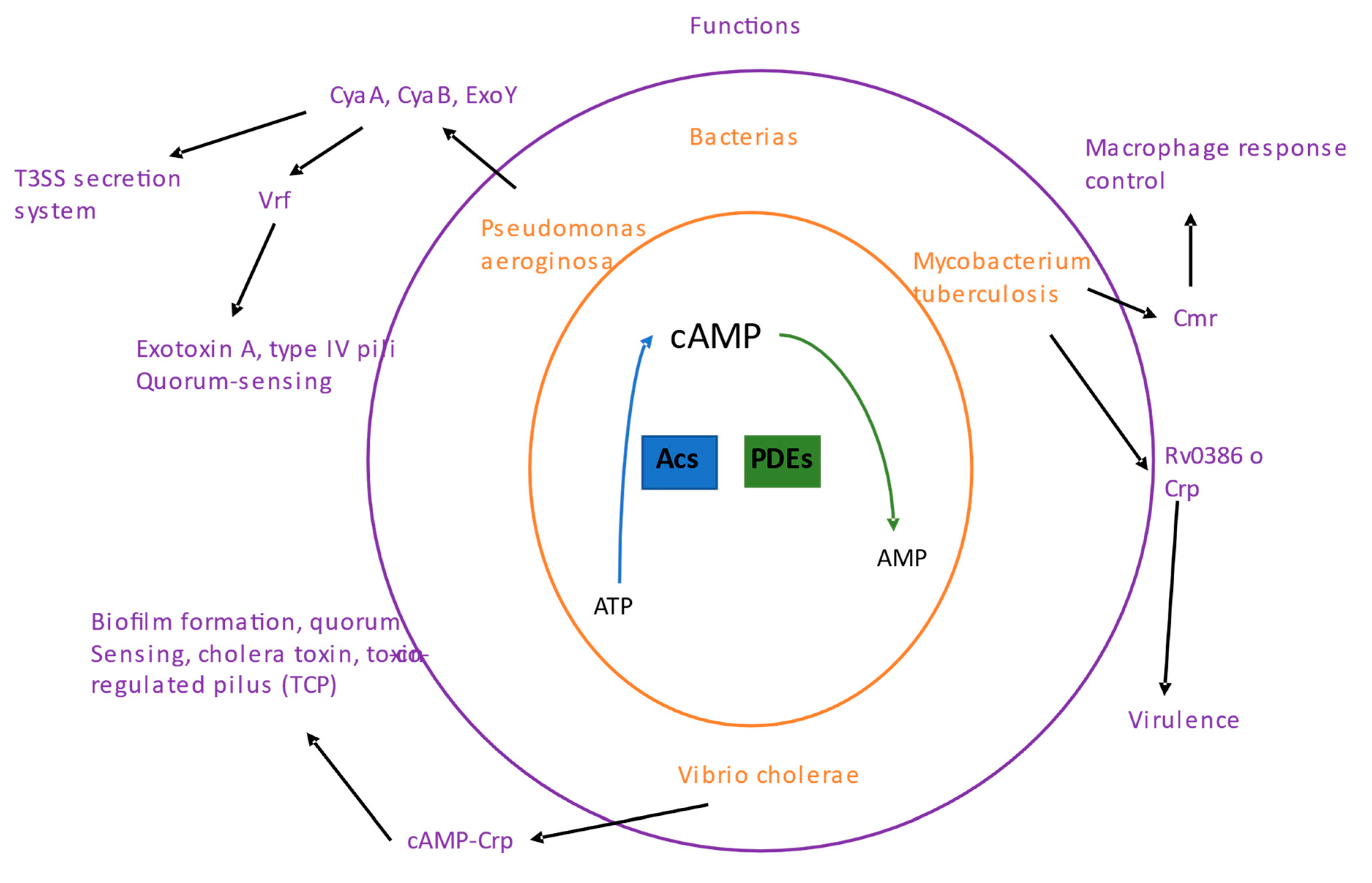

Cyclic AMP (cAMP) was nucleotide signaling first discovered in cells and is considered the most abundant cyclic nucleotide used by organisms. cAMP is synthesized by adenylyl cyclases (ACs) from ATP, and its degradation is carried out by phosphodiesterases (PDEs;

Figure 2). There are 6 classes of cAMP enzymes; class III is a large group of cAMP enzymes and the most diverse of all classes, and within this class are most bacterial cAMP enzymes [

58].

1.1. cAMP binds to cAMP receptor protein (CRP)

Signaling by cAMP in bacteria is mainly at the level of regulation of gene expression, whereas in eukaryotic cells, the mechanism is different. The cAMP receptor protein (CRP) family functions as a transcription factor in bacteria, and cAMP binds to CRP directly to activate it. These receptors counteract different cellular events directly, whereas, in eukaryotic cells, cAMP signaling is first mediated by an intermediate, commonly the protein kinase A (PKA) complex, and subsequently activation of transcription factors [

59] and one of the functions of cAMP in eukaryotic cells was in hormone signal transduction.

In bacteria, cAMP regulates the glucose response or catabolic repression [

60]; low glucose levels reduce cAMP production, activating the lac operon by binding cAMP to the Crp protein to form the cAMP-Crp complex. However, in recent years, cAMP has been involved in other processes, such as bacterial virulence, toxin control, and activation of master regulators, so the study of cAMP has attracted interest.

1.1. cAMP signaling in pathogenic bacteria

In pathogenic bacteria, cAMP signaling is essential because cAMP regulates biofilm formation, the type III secretion system, carbon metabolism, and the regulation of virulence genes. It has also been shown that intracellular pathogenic bacteria control or modulate cAMP levels within their host cells [

61] to carry out their infection process.

Glucose plays an important role in activating the AC enzyme; glucose depletion leads to the induction of AC enzyme activity in some bacteria, but this does not occur in others. This indicates that although the primary mechanism of cAMP signaling is via CRP family transcription factors, other diverse mechanisms of cAMP signaling within bacteria (other cAMP-associated regulatory targets) are possible and sometimes amplified by cAMP-mediated co-regulation of other global regulators [

62]. Some examples of cAMP signaling in pathogenic bacteria are mentioned below.

5.3. Pseudomonas aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa can express three ACs: CyaA, CyaB, and ExoY, indicating that cAMP plays a role in the pathogenesis of this bacterium. ExoY is an AC toxin that is activated within host cells, and this toxin is exported and introduced into the host cell via a cAMP-regulated T3SS secretion system [

63]. In contrast, the enzymes CyaA and CyaB are not exportable and remain within the cytosol of

P. aeruginosa; these intracellular ACs increase intracellular cAMP levels to control virulence gene expression. Ca

2+ is an environmental component for the expression of the T3SS secretion system, as low Ca

2+ concentration triggers cAMP production and, as a result, the expression of secretion system components [

64]. The way Ca

2+ is sensed in the environment is by CyaB, and detecting a low Ca

2+ concentration activates CyaB to produce high intracellular cAMP concentrations [

64]. Furthermore, CyaB is involved in virulence as deletion of

cyaB gene attenuates this process [

65] and is mainly due to low expression of T3SS components and overexpression of the regulatory factor, ExsA, restores the virulence phenotype due to reconstitution of the expression of the T3SS component system [

65]. Another cAMP-activated transcription factor is Vrf. cAMP binding to Vrf regulates transcriptional upregulation of many virulence-associated genes, such as type IV pili, the T3SS secretion system, exotoxin A, and the quorum sensing system [

66]. On the other hand, cAMP degradation is driven by the CpdA protein to reduce the amount of intracellular cAMP, and these conditions are necessary to overexpress virulence factors.

5.4. Vibrio cholerae

cAMP signaling is inhibited by

V. cholerae toxin (CT) during infection of intestinal epithelial cells, causing diarrhea. However, cAMP signaling in

V. cholerae has essential functions for the bacterium, such as integrating the available carbon source, promoting biofilm formation, sensitivity to bacteriophages, and expressing virulence genes. For example, in

Vibrio spp. it has a single AC enzyme called CyaA, which produces cAMP, and signaling is through the transcription factor CRP [

67]. Glucose is an essential component of the cAMP signaling process. Low glucose levels increase cAMP production by CyaA, which cAMP binds to the Crp transcription factor. The cAMP-Crp can regulate biofilm formation, quorum sensing, toxin-regulated pilus (TCP), and CT expression [

68].

5.5. Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Unlike other pathogenic bacteria,

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is distinguished by cAMP signaling. For example,

M. tuberculosis has 16 AC-like proteins and 10 confirmed AC, indicating that cAMP function is essential in this bacterium. Another difference is that low levels of glucose do not produce a significant effect on cAMP levels. In contrast, the AC activity is controlled by various host conditions; for example, fatty acids, carbon dioxide (CO

2), and pH can affect the activity of

M. tuberculosis ACs, while hypoxia and starvation affect the expression of genes encoding ACs [

61].

M. tuberculosis within the macrophage is known to produce and secrete cAMP. This production is by the AC, Rv0386, which has been corroborated by deleting the corresponding gene of Rv0386, resulting in a phenotype of decreased virulence and pathology of

M. tuberculosis in a murine infection model [

69].

In addition to the different ACs enzymes of

M. tuberculosis, ten putative cAMP-binding proteins have been identified as receptors. Among them are two transcription factors of the CRP family and a protein lysine acetylase. Regarding the two transcription factors, one Crp induces the expression of a regulon, where it can simultaneously control the expression of about 100 genes. An

M. tuberculosis strain with Crp deletion significantly reduces its virulence in a murine model [

70]. The second Crp transcription factor, Cmr, is involved in macrophage response and in the expression of genes in response to cAMP levels [

71].

1. The c-di-AMP nucleotide

The c-di-AMP dinucleotide was initially found bound to the DNA integrity scanning protein (DisA) of the bacterium

Thermotoga maritima [

72]. Subsequently, intracellular pathogenic bacteria (such as

Listeria monocytogenes) can secrete c-di-AMP to the cytosol of infected host cells [

73]. The bacteria

B. subtilis [

74],

Chlamydia trachomatis [

75],

S. aureus [

76] and

Streptococcus pyogenes [

77] produce c-di-AMP.

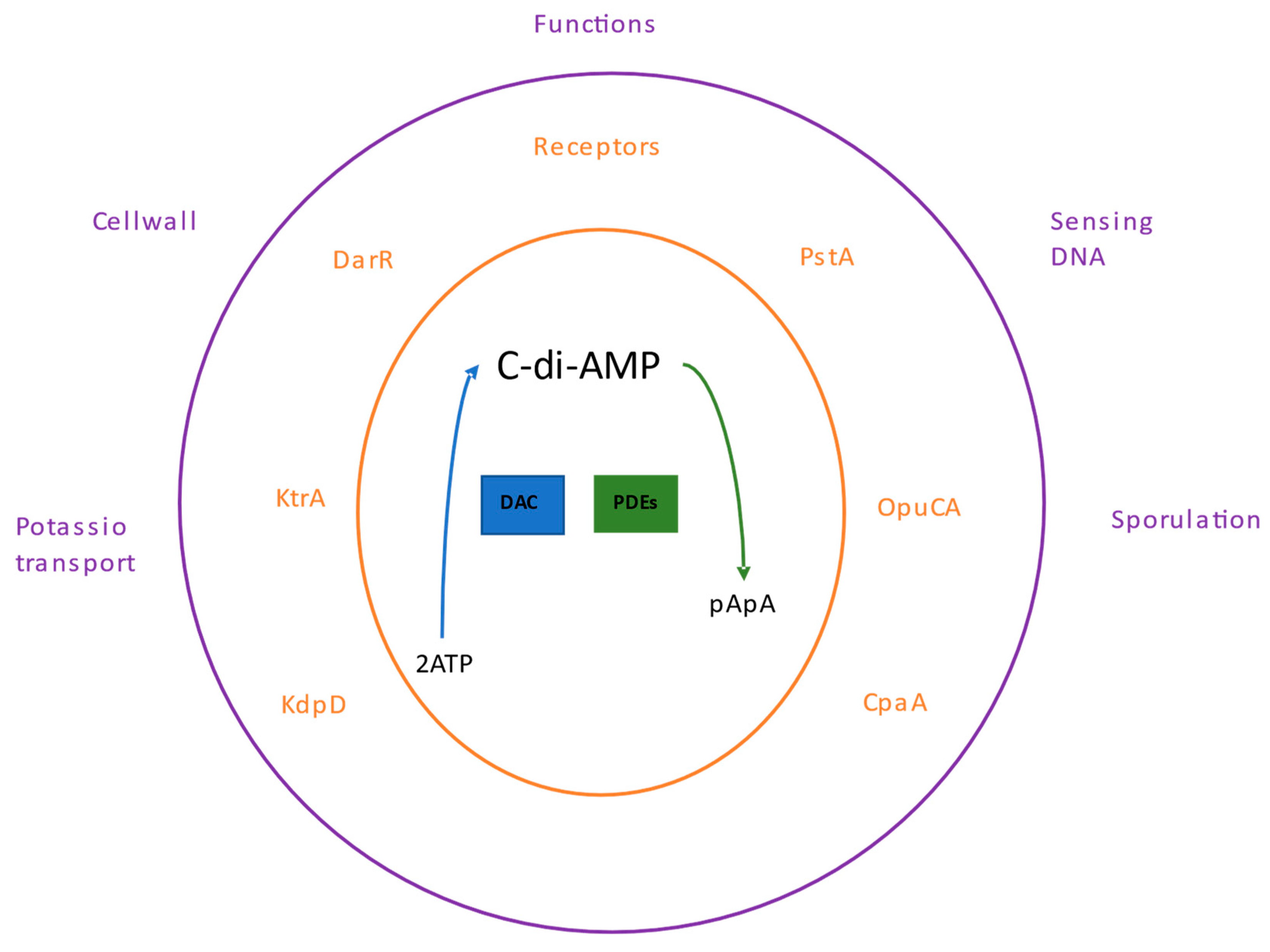

Like the other nucleotides, c-di-AMP binds to a specific set of receptor or target proteins; this binding modifies the functions of these proteins or may influence other effector proteins regulated by the receptor, thereby controlling cellular pathways. The c-di-AMP participates in several processes, including bacterial growth under low potassium conditions [

78], regulation of fatty acid synthesis in

Mycobacterium smegmatis [

79], cell wall homeostasis [

80] and sensing of DNA integrity in

B. subtilis [

81] (

Figure 3).

1.1. c-di-AMP receptors

The first c-di-AMP receptor was the Ms5346 protein from

M. smegmatis and corresponds to a regulator of the tetracycline resistance family (TetR) that was later renamed the c-di-AMP receptor regulator (DarR). In

M. smegmatis, DarR binds to its promoter and thus represses its transcription, and also does so for the promoters of the medium-chain acyl-CoA ligase transcription operon and the family of prominent transporter facilitators. The c-di-AMP-DarR complex causes increased interaction with DNA [

79], so changes in the level of c-di-AMP can affect fatty acid synthesis in

M. smegmatis.

In

S. aureus, KtrA, KdpD, PstA, CpaA, and OpuCA are c-di-AMP target proteins [

82]. CpaA is a predicted cation/proton antiporter protein, and OpuCA is the ATPase component of the ATP-to-carnitine binding cassette transporter OpuC [

83].

The KtrA protein is a member of the Ktr-type potassium transport system [

1]. KtraA binds with KtrB-type membrane components to form a potassium transport system, which has been detected in various bacteria [

84]. The c-di-AMP binds to the KtrA protein, causing a conformational change to be interpreted in the transporter components that ultimately make the KtrB protein able to open or close the potassium transporter channel. In addition, bacteria mutants in

gdpP gene, which produces high levels of c-di-AMP, are sensitive to salt stress and, similar to ktrA mutant strains, under osmotic stress conditions, require high potassium levels to grow [

78].

The c-di-AMP binds to the histidine kinase protein KdpD to control its function [

85]; the KdpD protein is involved in potassium homeostasis [

86]. KdpD protein and KdpE induce the expression of a second type of potassium uptake system [

87].

Another c-di-AMP receptor protein is PstA, which responds to cells' nitrogen and carbon by sensing glutamine and 2-ketoglutarate levels [

73,

88].

1.1. Cellular processes regulated by c-di-AMP

1.1.1. Cell wall homeostasis

Changes in c-di-AMP levels compromise bacterial cell wall integrity. In

S. aureus, DacA and GdpP enzymes synthesize and degrade c-di-AMP, respectively. The involvement of c-di-AMP on the cell wall has been studied with GdpP-deficient strains, where there is an increase in the intracellular levels of c-di-AMP, producing a phenotype of bacterial growth retardation and increased resistance to acid stress and beta-lactam antibiotics in

S. aureus [

89]. These mutants have also been reported to have increased peptidoglycan cross-linking. By microscopy, the GdpP-deficient

S. aureus strain significantly reduces cell size concerning the wild type [

76].

In contrast, attempts to obtain

dacA gene mutants in

S. aureus have failed, suggesting that c-di-AMP production is vital for bacterial growth. Strains of

B. subtilis and

L. monocytogenes that have mutated the

gdpP gene display increased resistance against beta-lactam antibiotics. In the case of

Lactococcus lactis and

L. monocytogenes,

gdpP-mutant strains are more resistant to heat stress [

90] and acid [

91], all indicating that cell wall changes occur in strains with high levels of c-di-AMP [

76]. In contrast to GdpP-mutant strains, strains overexpressing this protein have decreases in the level of c-di-AMP, and in

B. subtilis and

L. monocytogenes, it has been observed that they are susceptible to antibiotics targeting the cell wall [

91].

1.1.1. Sensing of DNA damage

When DNA is damaged, detection and repair mechanisms are activated. DisA is a sensor protein that can scan the chromosome DNA to detect alterations on DNA; when DisA performs this function, it simultaneously synthesizes c-di-AMP [

73]. The DisA movement on DNA depends on the synthesis of c-di-AMP [

73]. For example, it has been shown that when DNA strands are at a stalled replication fork or Holliday junction, c-di-AMP synthesis, and DisA movement stop, which decreases the level of c-di-AMP. This decrease in c-di-AMP levels is a likely signal to stop replication and initiate the DNA repair mechanism by the RadA protein. In the case of bacterial sporulation, DNA damage is detected by DisA, resulting in inhibition of sporulation initiation. Under these circumstances, c-di-AMP levels fall, and restoration of sporulation initiation can be triggered by the exogenous addition of c-di-AMP [

74], suggesting that c-di-GMP levels are a signal to control DNA damage. Furthermore, it has been observed that in

B. subtilis cells, the GdpP expression increases when DNA is exposed to an agent that damages this molecule, resulting in low c-di-AMP levels and sporulation rate [

74]. Therefore, c-di-AMP levels indicate DNA integrity and help ensure that only undamaged DNA is packaged within the

B. subtilis spore.

1.1. c-di-AMP in eukaryotic host cell

C-di-nucleotides control the bacterial physiology. However, c-di-AMP can also be detected by eukaryotic cells. Intra- and extracellular pathogens can release c-di-AMP, and this c-di-nucleotide stimulates the immune response of eukaryotic cells, principally in the production of type I IFN. Intracellular bacteria that escape from the vacuolar compartment and propagate into the cytosol can release c-di-AMP, which is released by the multidrug efflux pumps MdrM and MdrT. The presence of c-di-AMP in the cell cytosol drives a response dependent on the helicase DDX41 and the transmembrane receptor STING [

54,

92]. When c-di-AMP activates STING, it interacts with TBK1 kinase to activate it [

93]. This kinase activates the transcription factor IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), activated IRF3 translocates to the nucleus, and induces the type I IFN production. The c-di-AMP secreted by pathogenic bacteria can lead to immune recognition and modulation, which is proposed for therapeutic use as vaccine adjuvants, highlighting another potential use of these c-di-GMP and c-di-AMP molecules [

52].

1. The pppGpp or ppGpp nucleotide

Nutrients become limiting during bacterial growth, mainly in the stationary phase; in this condition, the bacterium resorts to other processes to reuse possible nutritional sources within the cell. The processes of synthesis of membrane components, ribosomal proteins, RNA, and DNA are arrested, and in response to this, it rapidly produces factors crucial for stress resistance [

94]. In general, all of these events are known as nutritional stress responses. Under nutritional stress conditions, a signaling process is triggered by the nucleotides guanosine tetraphosphate and guanosine pentaphosphate (ppGpp and pppGpp, respectively), called alarmones.

Two classes of enzymes carry out the synthesis of alarmones. One is the monofunctional synthetase enzyme, and the other is the bifunctional synthetase-hydrolase enzyme. The monofunctional synthetase corresponds to the RelA protein; this enzyme uses GTP and ATP as phosphate donors to generate ppGpp and convert it into pppGpp. Concerning bifunctional synthetase-hydrolase enzymes, they are represented by SpoT, Rel, or RSH (Rel-Spo homologous) proteins. These enzymes can synthesize ppGpp or pppGpp and hydrolyze these nucleotides to produce GDP and pyrophosphate (PPi) or GTP and PPi, respectively.

These two enzymes participate in alarmon synthesis by different metabolic states. RelA functions in alarmon synthesis when there is a shortage of amino acids and this causes uncharged tRNAs, which stimulate this enzyme's activity. In contrast, the bifunctional enzyme synthetase-hydrolase is involved when bacteria are under nutritional stress towards various nutrients, such as carbon, fatty acids, iron, or phosphate starvation. The synthesis of ppGpp under nutritional stress conditions causes a controlling effect on RNA polymerase (RNAP) activity in cooperation with the suppressor DnaK (DksA). The binding of ppGpp and DksA can regulate positively or negatively transcription by RNAP, and this control is determined by the intrinsic properties of the promoter in question, causing numerous physiological effects [

95].

On the other hand, DksA and ppGpp regulate RNAP transcription through an event of σ-factor competition. This event occurs as follows: in the logarithmic phase, vegetative σ-factor 70 (RpoD) binds to RNAP to initiate transcription of essential proteins, lipids, and DNA synthesis. In stringent conditions, bacteria produce high concentrations of ppGpp to inhibit RNAP-σ70 binding, consequently, RNAP is free to bind to other types of sigma factors such as sigma E and sigma S that these are present when the bacterium is under stress conditions [

96]. Now, when metabolic precursors are at full strength or restored, SpoT degrades ppGpp. Thus, the σ-vegetative factor, σ70, controls RNAP to transcribe genes crucial for DNA replication and biomolecule synthesis.

A mechanism is now known in

E. coli to stabilize and activate sigma S function under stress conditions. This mechanism consists of the fact that in the logarithmic growth phase, the sigma S protein is bound to the RssB protein (an adaptor protein), and this sigmaS-RssB binding drives the proteolytic degradation of sigma S by the ClpXP proteasome [

97]. However, during phosphate stress, the hydrolase activity of SpoT is inhibited. Therefore, ppGpp synthesis is elevated, then ppGpp binds to RNAP to transcribe and produce IraP and IraD, which are anti-adaptor proteins that sequester RssB and prevent sigma S delivery to the ClpXP proteasome [

98].

When there is a low concentration of amino acids, the bacterium encodes ppGpp to recover amino acids from conventional proteins, such as ribosomal proteins. In

E. coli, the ppGpp alarmon inhibits the transcription of ribosomal protein-coding genes, and the alarmones inhibit exopolyphosphatase activity, causing accumulation of polyphosphate in the cytosol. Accumulated polyphosphate binds to free ribosomal proteins to be degraded by Lon protease, producing free amino acids for enzymatic biosynthesis [

99].

On the other hand, amino acids can be degraded to produce by-products of metabolic interest. However, under stress conditions, these events are regulated by alarmones; for example, it has been shown that in E. coli, ppGpp inhibits the lysine decarboxylase enzyme. When amino acids are limited, ppGpp interacts with the LdcI (lysine decarboxylase inducible) protein to inhibit its activity, preserving the cytoplasmic lysine pool for protein synthesis. On the other hand, ppGpp regulates some other key bacterial processes, e.g., protein synthesis and DNA replication are down-regulated by ppGpp through direct inhibition of translation elongation factor activity and DNA primase, respectively.

On the other hand, alarmon can modulate the virulence of pathogenic bacteria to couple with nutritional stress conditions [

100]. In

Legionella pneumophila within the phagocyte, ppGpp is produced to induce the activation of two noncoding regulatory RNAs, RsmZ and RsmY, which bind to the mRNA of a global repressor and CsrA, which are virulence or survival inhibitors, as well as RsmY and RsmZ activate the sigma S factor in the stationary phase and the two-component LetA-LetS system [

101]. In phagocytosis,

S. Typhimurium induces the PhoPQ two-component system. SlyA protein is expressed by the PhoPQ system, and SlyA regulates the transcription of genes essential for virulence in

S. Typhimurium [

102]. ppGpp activates the function of the SlyA protein, facilitating the binding of SlyA to target promoters involved in the virulence of this bacterium [

103].

1.1. Interactions between ppGpp and c-di-GMP and c-di-AMP

The signaling interaction between ppGpp and c-di-GMP is opposite in the biofilm formation. Low doses of antibiotics with translation inhibitory action, such as erythromycin, tetracycline, or chloramphenicol, induce degradation of ppGppp by SpoT activity and lead to an increase in the expression of

pgaA gene, which encodes the protein necessary to synthesize poly-GlcNAc [

31]. Conversely, maximal poly-GlcNAc production also requires the formation of c-di-GMP by the enzyme DGC YdeH [

31], suggesting that bacteria in antibiotic stress condition inactive alarmone signaling to induce a barrier of protection (biofilm) against antimicrobial agents.

C-di-AMP likely influences stringent signaling; in vitro, it has been observed that phosphodiesterase activity to degrade c-di-AMP is inhibited by ppGpp [

100]. Consequently, ppGpp maintains the cellular pool of c-di-AMP. The interaction between ppGpp-mediated signaling and c-di-nucleotides shows the influence of alarmon on bacterial physiology.

1. Conclusion and Prospects

Although c-di-nucleotides, as second messengers, are heavily involved in various bacterial biological processes, the molecular mechanism of the environmental signal that triggers their synthesis or degradation has yet to be elucidated. Moreover, the processes involving c-di-nucleotides are complex, and, as mentioned above, c-di-nucleotides bind to receptor proteins as key transcription factors that regulate these processes. So far, the inactivation of c-di-nucleotide signaling when the biological process has completed its function has yet to be discovered in detail. It is foreseeable that there are other biological processes in which c-di-nucleotide signaling is involved and that other receptor proteins yet to be discovered may be involved. In addition, c-di-nucleotide signaling may be directed to inhibit bacterial biological processes, especially virulence factors in pathogenic bacteria, to control or inhibit bacterial infections. New approaches are needed to use these c-di-nucleotides as therapeutics for eukaryotic cells or to treat intracellular pathogenic bacteria.

Author Contributions

M.E.C.D.: writing and revision of the manuscript; G.B.C.: writing of manuscript; C.G.B: funding and acquisition. J.C.C.D.: conceptualization and supervision of manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Secretaria de investigación y posgrado (SIP) del Instituto Politécnico Nacional (clave: 20230967).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

M.E.C.D., C.G.B. and J.C.C.D. appreciate the COFAA and EDI-IPN fellowships. All authors are SNI-CONACyT fellows.

References

- McDonough, K.A.; Rodriguez, A. The myriad roles of cyclic AMP in microbial pathogens: from signal to sword. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalebroux, Z.D.; Swanson, M.S. ppGpp: magic beyond RNA polymerase. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makman, R.S.; Sutherland, E.W. Adenosine 3ʹ,5ʹ -phosphate in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1965, 240, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, J.C.; Yildiz, F.H. Interplay between cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein and cyclic di-GMP signaling in Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 6646–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.J.; Ryjenkov, D.A.; Gomelsky, M. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 4774–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christen, M.; Christen, B.; Folcher, M.; Schauerte, A.; Jenal, U. Identification and characterization of a cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase and its allosteric control by GTP. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 30829–30837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simm, R.; Morr, M.; Kader, A.; Nimtz, M.; Romling, U. GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulke, J.; Kruger, L. Cyclic di-AMP signaling in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yin, W.; Galperin, M.Y.; Chou, S.H. Cyclic di-AMP, a second messenger of primary importance: tertiary structures and binding mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 2807–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.T.; Nhiep, N.T.H.; Vu, T.N.M.; Huynh, T.N.; Zhu, Y.; Huynh, A.L.D.; Chakrabortti, A.; Marcellin, E.; Lo, R.; Howard, C.B.; Bansal, N.; Woodward, J.J.; Liang, Z.X.; Turner, M.S. Enhanced uptake of potassium or glycine betaine or export of cyclic-diAMP restores osmoresistance in a high cyclic-di-AMP Lactococcus lactis mutant. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römling, U.; Gomelsky, M.; Galperin, M.Y. c-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 57, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, F.; See, R.Y.; Zhang, D.; Toh, D.C.; Ji, Q.; Liang, Z.X. YybT is a signaling protein that contains a cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase domain and a GGDEF domain with ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.L.; Tuckerman, J.R.; Gonzalez, G.; Mayer, R.; Weinhouse, H.; Volman, G.; Amikam, D.; Benziman, M.; Gilles-Gonzalez, M.A. Phosphodiesterase A1, a regulator of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum, is a heme-based sensor. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 3420–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryjenkov, D.A.; Simm, R.; Römling, U.; Gomelsky, M. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP. The PilZ domain protein YcgR controls motility in enterobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 30310–30314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, J.T.; Tamayo, R.; Tischler, A.D.; Camilli, A. PilZ domain proteins bind cyclic diguanylate and regulate diverse processes in Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 12860–12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerig, A.; Abel, S.; Folcher, M.; Nicollier, M.; Schwede, T.; Amiot, N.; Giese, B.; Jenal, U. Second messenger-mediated spatiotemporal control of protein degradation regulates bacterial cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobley, L.; Fung, R.K.; Lambert, C.; Harris, M.A.; Dabhi, J.M.; King, S.S.; Basford, S.M.; Uchida, K.; Till, R.; Ahmad, R.; Aizawa, S.; Gomelsky, M.; Sockett, R.E. Discrete cyclic di-GMP-dependent control of bacterial predation versus axenic growth in Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.D.; Monds, R.D.; O’Toole, G.A. LapD is a bis-(3´, 5´)-cyclicdimeric GMP-binding protein that regulates surface attachment by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 3461–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, J.E.; Breaker, R.R. The distributions, mechanisms, and structures of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.R.; Baker, J.L.; Weinberg, Z.; Sudarsan, N.; Breaker, R.R. An allosteric self-splicing ribozyme triggered by a bacterial second messenger. Science 2010, 329, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobrov, A.G.; Kirillina, O.; Ryjenkov, D.A.; Waters, C.M.; Price, P.A.; Fetherston, J.D.; Mack, D.; Goldman, W.E.; Gomelsky, M.; Perry, R.D. Systematic analysis of cyclic di-GMP signalling enzymes and their role in biofilm formation and virulence in Yersinia pestis. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 79, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simm, R.; Morr, M.; Kader, A.; Nimtz, M.; Römling, U. GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.Z.; Pitzer, J.E.; Boquoi, T.; Hobbs, G.; Miller, M.R.; Motaleb, M.A. Analysis of the HD-GYP domain cyclic dimeric GMP phosphodiesterase reveals a role in motility and the enzootic life cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 3273–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, H.S.; Liu. Y.; Ryu, W.S.; Tavazoie, S. A comprehensive genetic characterization of bacterial motility. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, 1644–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyot, J.; Dasgupta, N.; Ramphal, R. FleQ, the major flagellar gene regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, binds to enhancer sites located either upstream or atypically downstream of the RpoN binding site. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 5251–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, I.D.; Remminghorst, U.; Rehm, B.H. MucR, a novel membrane associated regulator of alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römling, U. Cyclic di-GMP, an established secondary messenger still speeding up. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1817–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.G.; Clegg, S. Role of MrkJ, a phosphodiesterase, in type 3 fimbrial expression and biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 3944–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meissner, A.; Wild, V.; Simm, R.; Rohde, M.; Erck, C.; Bredenbruch, F.; Morr, M.; Römling, U.; Häussler, S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cupA encoded fimbriae expression is regulated by a GGDEF and EAL domain dependent modulation of the intracellular level of cyclic diguanylate. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 2475–2485.

- Huang, B.; Whitchurch, C.B.; Mattick, J.S. FimX, a multidomain protein connecting environmental signals to twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 7068–7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, A.; Steiner, S.; Zaehringer, F.; Casanova, A.; Hamburger, F.; Ritz, D.; Keck, W.; Ackermann, M.; Schirmer, T.; Jenal, U. Second messenger signalling governs Escherichia coli biofilm induction upon ribosomal stress. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 72, 1500–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Preston, J.F., 3rd; Romeo, T. The pgaABCD locus of Escherichia coli promotes the synthesis of a polysaccharide adhesin required for biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 2724–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland LM, O’Donnell ST, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky L, Slater SR, FeyPD, Gomelsky M, O’Gara JP. 2008. A staphylococcal GGDEF domainprotein regulates biofilm formation independently of c-di-GMP. J. Bacteriol. 190:5178–5189.

- Güvener, Z.T.; Harwood, C.S. Subcellular location characteristics of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa GGDEF protein, WspR, indicate that it produces cyclic-di-GMP in response to growth on surfaces. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 66, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraquet, C.; Murakami, K.; Parsek, M.R.; Harwood, C.S. The FleQ protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa functions as both a repressor and an activator to control gene expression from the pel operon promoter in response to c-di-GMP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 7207–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, Y.; Borlee, B.R.; O’Connor, J.R.; Hill, P.J.; Harwood, C.S.; Wozniak, D.J.; Parsek, M.R. Self-produced exopolysaccharide is a signal that stimulates biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 20632–20636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merighi, M.; Lee, V.T.; Hyodo, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Lory, S. The second messenger bis-(3´-5´)-cyclic-GMP and its PilZ domain-containing receptor Alg44 are required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 65, 876–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyhan, S.; Yildiz, F.H. Smooth to rugose phase variation in Vibrio cholerae can be mediated by a single nucleotide change that targets c-diGMP signalling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 63, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, A.; Wood, T.K. Tyrosine phosphatase TpbA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls extracellular DNA via cyclic diguanylic acid concen- trations. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2010, 2, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, B.K.; Bassler, B.L. Distinct sensory pathways in Vibrio cholerae El Tor and classical biotypes modulate c-di-GMP levels to control biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 191, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.; Saxena, I.; Wang, X.; Kade, A.; Bokranz, W.; Simm, R.; Nobles, D.; Chromek, M.; Brauner, A.; Brown, R.M., Jr.; Römling, U. Characterization of cellulose production in Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 and its biological consequences. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, R.; Jaeger, T.; Abel, S.; Wiederkehr, I.; Folcher, M.; Biondi, E.G.; Laub, M.T.; Jenal, U. Allosteric regulation of histidine kinases by their cognate response regulator determines cell fate. Cell 2008, 133, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, S.; Chien, P.; Wassmann, P.; Schirmer, T.; Kaever, V.; Laub, M.T.; Baker, T.A.; Jenal, U. Regulatory cohesion of cell cycle and cell differentiation through interlinked phosphorylation and second messenger networks. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neunuebel, M.R.; Golden, J.W. The Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 gene all2874 encodes a diguanylate cyclase and is required for normal heterocyst development under high-light growth conditions. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 6829–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Hengst, C.D.; Tran, N.T.; Bibb, M.J.; Chandra, G.; Leskiw, B.K.; Buttner, M.J. Genes essential for morphological development and antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor are targets of BldD during vegetative growth. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 78, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tischler, A.D.; Camilli, A. Cyclic diguanylate regulates Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 5873–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Ouyang, Z.; Troxell, B.; Xu, H.; Moh, A.; Piesman, J.; Norgard, M.V.; Gomelsky, M.; Yang, X.F. Cyclic di-GMP is essential for the survival of the Lyme disease spirochete in ticks. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, C.; Garcia, B.; Latasa, C.; Toledo-Arana, A.; Zorraquino, V.; Valle, J.; Casals, J.; Pedroso, E.; Lasa, I. Genetic reductionist approach for dissecting individual roles of GGDEF proteins within the c-di-GMP signaling network in Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 7997–8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, E.; Chaudhuri, P.; Gourley, C.; Harms, J.; Splitter, G. Brucella melitensis cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase BpdA controls expression of flagellar genes. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 5683–5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zogaj, X.; Wyatt, G.C.; Klose, K.E. Cyclic di-GMP stimulates biofilm formation and inhibits virulence of Francisella novicida. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 4239–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amikam, D.; Steinberger, O.; Shkolnik, T.; Ben-Ishai, Z. The novel cyclic dinucleotide 3´-5´ cyclic diguanylic acid binds to p21ras and enhances DNA synthesis but not cell replication in the Molt 4 cell line. Biochem. J. 1995, 311, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaolis, D.K.; Cheng, K.; Lipsky, M.; Elnabawi, A.; Catalano, J.; Hyodo, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Raufman, J.P. 3´, 5´-Cyclic diguanylic acid (c-diGMP) inhibits basal and growth factor-stimulated human colon cancer cell proliferation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 329, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.L.; Narita, K.; Hyodo, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Nakane, A.; Karaolis, D.K. c-di-GMP as a vaccine adjuvant enhances protection against systemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection. Vaccine 2009, 27, 4867–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdette, D.L.; Monroe, K.M.; Sotelo-Troha, K.; Iwig, J.S.; Eckert, B.; Hyodo, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Vance, R.E. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature 2011, 478, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteley, A.T.; Eaglesham, J.B.; de Oliveira Mann, C.C.; Morehouse, B.R.; Lowey, B.; Nieminen, E.A.; Danilchanka, O.; King, D.S.; Lee, A.S.Y.; Mekalanos, J.J.; Kranzusch, P.J. Bacterial cGAS-like enzymes synthesize diverse nucleotide signals. Nature 2019, 567, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B.W.; Bogard, R.W.; Young, T.S.; Mekalanos, J.J. Coordinated regulation of accessory genetic elements produces cyclic di-nucleotides for V. cholerae virulence. Cell 2012, 149, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zhu, B. The cyclic oligoadenylate signaling pathway of type III CRISPR-Cas systems. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 602789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamenetsky, M.; Middelhaufe, S.; Bank, E.M.; Levin, L.R.; Buck, J.; Steegborn, C. Molecular details of cAMP generation in mammalian cells: a tale of two systems. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 362, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarejos, J.Y.; Montminy, M. CREB and the CRTC co-activators: sensors for hormonal and metabolic signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, A.; Busby, S.; Buc, H.; Garges, S.; Adhya, S. Transcriptional regulation by cAMP and its receptor protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1993, 62, 749–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Knapp, G.S.; McDonough, K.A. Cyclic AMP signalling in mycobacteria: redirecting the conversation with a common currency. Cell Microbiol. 2011, 13, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, K.H. Vibrio vulnificus rpoS expression is repressed by direct binding of cAMP-cAMP receptor protein complex to its two promoter regions. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 30438–30450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahr, T.L.; Vallis, A.J.; Hancock, M.K.; Barbieri, J.T.; Frank, D.W. ExoY, an adenylate cyclase secreted by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 13899–13904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang, M.C.; Lee, V.T.; Gilmore, M.E.; Lory, S. Coordinate regulation of bacterial virulence genes by a novel adenylate cyclase-dependent signaling pathway. Dev. Cell. 2003, 4, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.S.; Wolfgang, M.C.; Lory, S. An adenylate cyclase-controlled signaling network regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, E.L.; Brutinel, E.D.; Jones, A.K.; Fulcher, N.B.; Urbanowski, M.L.; Yahr, T.L.; Wolfgang, M.C. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Vfr regulator controls global virulence factor expression through cyclic AMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 3553–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorupski, K.; Taylor, R.K. Cyclic AMP and its receptor protein negatively regulate the coordinate expression of cholera toxin and toxin-coregulated pilus in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997, 94, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Pascual-Montano, A.; Silva, A.J.; Benitez, J.A. The cyclic AMP receptor protein modulates quorum sensing, motility and multiple genes that affect intestinal colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 2007, 153, 2964–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, N.; Lamichhane, G.; Gupta, R.; Nolan, S.; Bishai, W.R. Cyclic AMP intoxication of macrophages by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis adenylate cyclase. Nature 2009, 460, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickman, L.; Scott, C.; Hunt, D.M.; Hutchinson, T.; Menéndez, M.C.; Whalan, R.; Hinds, J.; Colston, M.J.; Green, J.; Buxton, R.S. A member of the cAMP receptor protein family of transcription regulators in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for virulence in mice and controls transcription of the rpfA gene coding for a resuscitation promoting factor. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 56, 1274–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdik, M.A.; Bai, G.; Wu, Y.; McDonough, K.A. Rv1675c (cmr) regulates intramacrophage and cyclic AMP-induced gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-complex mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 71, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, G.; Hartung, S.; Buttner, K.; Hopfner, K.P. Structural biochemistry of a bacterial checkpoint protein reveals diadenylate cyclase activity regulated by DNA recombination intermediates. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, J.J.; Iavarone, A.T.; Portnoy, D.A. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science 2010, 328, 1703–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppenheimer-Shaanan, Y.; Wexselblatt, E.; Katzhendler, J.; Yavin, E.; Ben-Yehuda, S. c-di-AMP reports DNA integrity during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, J.R.; Koestler, B.J.; Carpenter, V.K.; Burdette, D.L.; Waters, C.M.; Vance, R.E.; Valdivia, R.H. STING-dependent recognition of cyclic di-AMP mediates type I interferon responses during Chlamydia trachomatis infection. mBio 2013, 4, e00018–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, R.M.; Abbott, J.C.; Burhenne, H.; Kaever, V.; Grundling, A. c-di-AMP is a new second messenger in Staphylococcus aureus with a role incontrolling cell size and envelope stress. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamegaya, T.; Kuroda, K; Hayakawa, Y. Identification of a S treptococcus pyogenes SF370 gene involved in production of c-di-AMP. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2011, 73, 49–57.

- Corrigan, R.M.; Campeotto, I.; Jeganathan, T.; Lee, V.T.; Gründling, A. Systematic identification of conserved bacterial c-di-AMP receptor proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 9084–9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, W.; He, Z.G. DarR, a TetR-like transcriptional factor, is a cyclic di-AMP-responsive repressor in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 3085–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Helmann, J.D. Analysis of the role of Bacillus subtilis σM in β-lactam resistance reveals an essential role for c-di-AMP in peptidoglycan homeostasis. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 83, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehne, F.M.; Gunka, K.; Eilers, H.; Herzberg, C.; Kaever, V.; Stülke, J. Cyclic di-AMP homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis: both lack and high-level accumulation of the nucleotide are detrimental for cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 2004–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Youn, S.J.; Kim, S.O.; Ko, J.; Lee, J.O.; Choi, B.S. Structural studies of potassium transport protein KtrA regulator of conductance of K (RCK) C domain in complex with cyclic diadenosine monophosphate (c-di-AMP). J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 16393–16402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, K.H.; Liang, J.M.; Yang, J.G.; Shih, M.S.; Tu, Z.L.; Wang, Y.C.; Sun, X.H.; Hu, N.J.; Liang, Z.X.; Dow, J.M.; Ryan, R.P.; Chou, S.H. Structural insights into the distinct binding mode of cyclic di-AMP with SaCpaA_RCK. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 4936–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, I.; Tholema, N.; Kröning, N.; Vor der Brüggen, M.; Wunnicke, D.; Bakker, E.P. KtrB, a member of the superfamily of K+ transporters. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 90, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gries, C.M.; Bose, J.L.; Nuxoll, A.S.; Fey, P.D.; Bayles, K.W. The Ktr potassium transport system in Staphylococcus aureus and its role in cell physiology, antimicrobial resistance and pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 89, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, Z.N.; Dorus, S.; Waterfield, N.R. The KdpD/KdpE two-component system: integrating K+ homeostasis and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, W. The roles and regulation of potassium in bacteria. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2003, 75, 293–320. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M.; Hopfner, K.P.; Witte, G. c-di-AMP recognition by Staphylococcus aureus PstA. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, L.; Zeden, M.S.; Schuster, C.F.; Kaever, V.; Gründling, A. New insights into the cyclic di-adenosine monophosphate (c-diAMP) degradation pathway and the requirement of the cyclic dinucleotide for acid stress resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 26970–26986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, W.M.; Pham, T.H.; Lei, L.; Dou, J.; Soomro, A.H.; Beatson, S.A.; Dykes, G.A.; Turner, M.S. Heat resistance and salt hypersensitivity in Lactococcus lactis due to spontaneous mutation of llmg_1816 (gdpP) induced by high-temperature growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7753–7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, C.E.; Whiteley, A.T.; Burke, T.P.; Sauer, J.D.; Portnoy, D.A.; Woodward, J.J. Cyclic di-AMP is critical for Listeria monocytogenes growth, cell wall homeostasis, and establishment of infection. mBio 2013, 4, e00282-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, J.D.; Sotelo-Troha, K.; von Moltke, J.; Monroe, K.M.; Rae, C.S.; Brubaker, W.; Hyodo, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Woodward, J.J.; Portnoy, D.A.; Vance, R.E. The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of Sting in the in vivo interferon response to Listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infect. Immun. 2010, 79, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, T.; Fujita, N.; Hayashi, T.; Takahara, K.; Satoh, T.; Lee, H.; Matsunaga, K.; Kageyama, S.; Omori, H.; Noda, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Kawai, T.; Ishii, K.; Takeuchi, O.; Yoshimori, T.; Akira, S. Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 20842–20846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potrykus, K.; Cashel, M. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 62, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugen, S.P.; Ross, W.; Gourse, R.L. Advances in bacterial promoter recognition and its control by factors that do not bind DNA. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterberg, S.; Del Peso-Santos, T.; Shingler, V. Regulation of alternative sigma factor use. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 65, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengge-Aronis, R. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the σS (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougdour, A.; Wickner, S.; Gottesman, S. Modulating RssB activity: IraP, a novel regulator of σS stability in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siculella, L.; Damiano, F.; di Summa, R.; Tredici, S.M.; Alduina, R.; Gnoni, G.V.; Alifano, P. Guanosine 5′-diphosphate 3′-diphosphate (ppGpp) as a negative modulator of polynucleotide phosphorylase activity in a ‘rare’ actinomycete. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 77, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; See, R.Y.; Zhang, D.; Toh, D.C.; Ji, Q.; Liang, Z.X. YybT is a signaling protein that contains a cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase domain and a GGDEF domain with ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahr, T.; Brüggemann, H.; Jules, M.; Lomma, M.; Albert-Weissenberger, C.; Cazalet, C.; Buchrieser, C. Two small ncRNAs jointly govern virulence and transmission in Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 72, 741–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, D.W.; Miller, V.L. Regulation of virulence by members of the MarR/SlyA family. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Weatherspoon, N.; Kong, W.; Curtiss, R.; Shi, Y. A dual-signal regulatory circuit activates transcription of a set of divergent operons in Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 20924–20929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).