Semaglutide, brand name Ozempic

® (Noro Nordisk), was originally approved by the FDA in 2017 to treat type 2 diabetes. Semaglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and works by slowing gastric emptying, increasing glucose-dependent insulin secretion, and decreasing postprandial glucagon and food intake.

1 Novo Nordisk, the manufacturer of semaglutide, also received FDA approval in June of 2021 to use semaglutide under the brand name Wegovy

® for chronic weight loss [

1]. Similar to apremilast, which was approved for the treatment of psoriasis and was subsequently assessed earlier this year in a placebo-controlled trial to curb alcohol consumption, semaglutide users have taken to social media to report both a decrease in their desire to drink as well as their overall alcohol consumption [

2,

3]. Although based on personal accounts, the observations regarding semaglutide's ability to reduce alcohol intake are noteworthy and have garnered attention from various media outlets. A recent segment on The TODAY show, titled "Weight loss with Ozempic or Wegovy may reduce desire for alcohol in some patients," featured a comment from a Wegovy® user who shared, “I can’t tolerate beer at all so I haven’t had any beer in months… I don’t remember the last time I’ve had wine [

4]”.

Based on these comments and on the heels of the apremilast human trial, we designed a survey to evaluate alcohol use among adults taking semaglutide. We aimed to assess the extent and the consistency of the reported "side effect" of reduced drinking and suppressed desire to drink. The survey, which was approved by the Rocky Vista University Institutional Review Board (Approval # 2023-053), was deployed in semaglutide-focused Facebook and Reddit groups between March 23

rd and 29

th, 2023, and asked about experiences with alcohol before and after starting semaglutide. All authors contributed to the data analysis. Our sample (N=608) were 81·6% women (N=496) and 88·6% white (N=539). Most respondents, or 53·6% (N=326) were between 35 and 54 years of age.

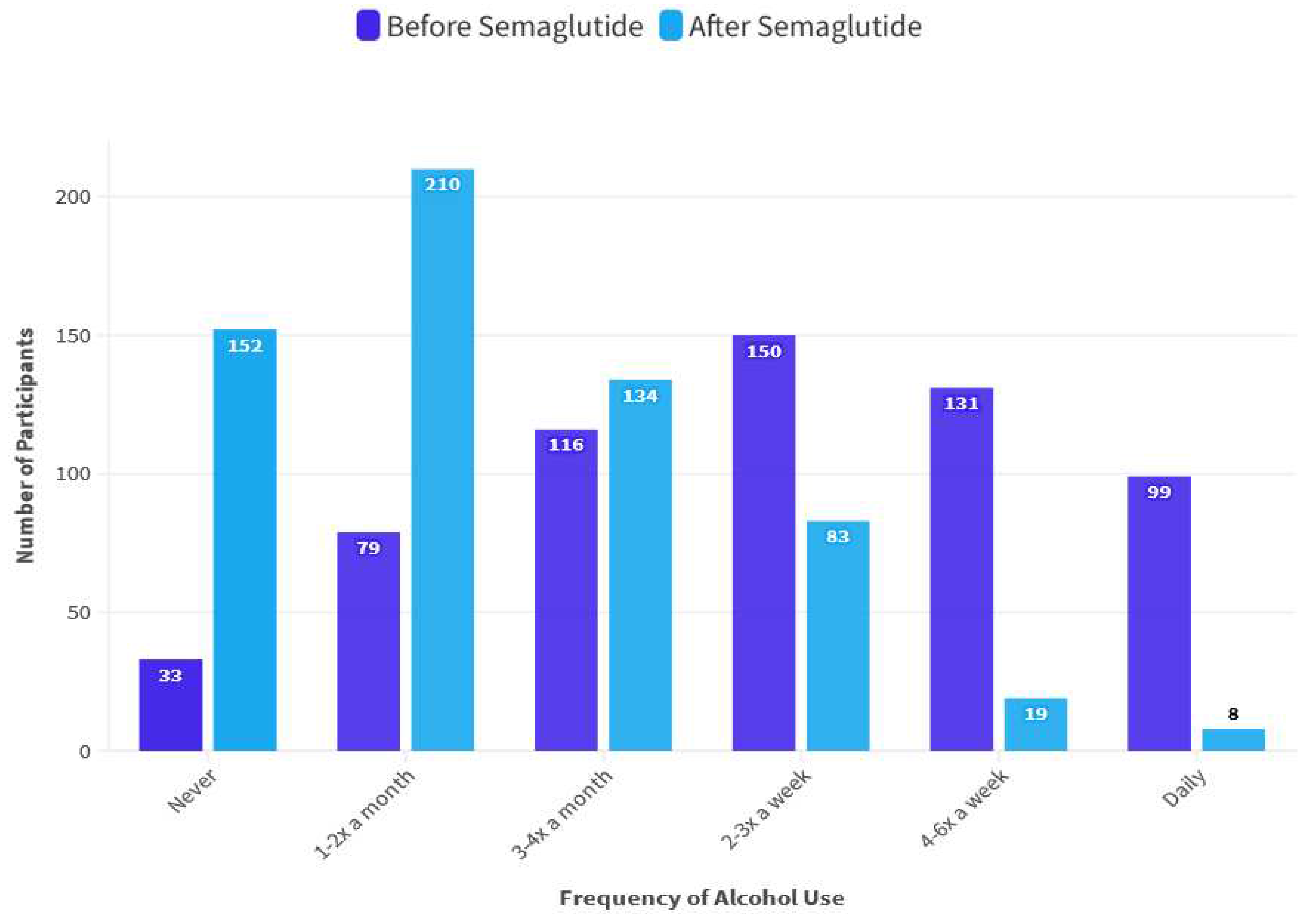

Figure 1 shows the frequency of alcohol consumption reported before and after starting semaglutide. The median response to "how often do you drink" decreased from 2-3 times per week to 1-2 times monthly, significant at p<.001 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Among respondents who reported any drinking before taking semaglutide, 21% (N=121) stopped drinking (dropped to 0% usage), and 88·4% (N=538) reported a decreased desire to drink alcohol after starting their medication. The survey respondents report drinking substantially less alcohol at each session (supplementary tables and descriptive statistics). Perhaps the most striking observation is that, per the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism's (NIAAA) definition of heavy drinking (consuming >4 drinks on any day for males and consuming >3 drinks per day for females), 21·9% of the total (N=133) respondents met the NIAAA’s definition of heavy drinking before starting Semaglutide [

5,

6]. Of these 133 respondents, 88·7% (N=118) fell out of that category (see supplemental information) after starting semaglutide. These findings support the premise that patients taking semaglutide could have a clinically meaningful decrease in the frequency of drinking and in the amount of alcohol consumed when drinking.

Heavy drinking is reported by nearly 6% of U.S. adults, and nearly 17% engage in binge drinking.

7 Excessive alcohol use creates a broad social and economic burden of

$249 billion a year, including lost revenue from decreased workplace productivity, damages from collisions, and criminal justice costs [

7]. A 2022 report in JAMA showed that between 2015 and 2019, an estimated annual mean of 140,557 deaths [97,182 men (69%) and 43,375 women (31%)] were attributable to excessive alcohol consumption, comprising 5% of total adult U.S. deaths [

8]. Medications currently available to treat alcoholism (e.g., disulfiram, naltrexone, acamprosate, topiramate, baclofen, and nalmefene) show both small effect sizes and trivial buy-in from providers and patients alike [

9]. The results reported here support the hypothesis that semaglutide could have therapeutic implications for reducing alcohol use [

10,

11].

Finally, anecdotal reports of reductions in or cessation of compulsive or "addictive" behaviors beyond decreased consumption of and desire to drink alcohol were shared by respondents, including gambling, shopping, (illicit) drug use, and obsessive skin picking. One participant said, "I have pinched and tweezed my chin compulsively for years. This behavior has reduced dramatically...". Another said, "I've had a huge decrease (in alcohol use). But for me, it's been even more than that. I had a huge problem taking Adderall, hoping it would decrease my appetite. For five years, I'd take Adderall, and while on it, I would compulsively gamble online. Since taking Wegovy, I've lost all desire for stimulants, and the thought of gambling sounds so stupid all of a sudden." Based on the burgeoning reports of experiences like these and our compelling survey results reflecting reduced frequency and amount of alcohol consumption, we strongly advocate for scientifically rigorous investigations and clinical trials into the potential of semaglutide for curbing alcohol use and other unwanted compulsive behaviors.

References

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine 2021; 384: 989–1002.

- Zerilli T, Ocheretyaner E. Apremilast (Otezla): A new oral treatment for adults with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. P & T: a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management. 2015; published online Aug. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4517531/ (accessed April 19, 2023).

- Grigsby KB, Mangieri RA, Roberts AJ, et al. Preclinical and clinical evidence for suppression of alcohol intake by Apremilast. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2023; 133. [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski A. Weight loss with Ozempic or Wegovy can have unexpected side effect: No desire for alcohol. TODAY.com. 2023; published online March 24. https://www.today.com/health/mind-body/ozempic-wegovy-weight-loss-alcohol-rcna76300 (accessed April 19, 2023).

- Alcohol abuse: How to recognize problem drinking. American Family Physician. 2004; published online March 15. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2004/0315/p1497.html (accessed April 19, 2023).

- Drinking levels defined. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking (accessed April 19, 2023).

- Data on excessive drinking. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022; published online Nov 28. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/data-stats.htm (accessed April 19, 2023).

- Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among us adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Network Open 2022; 5. [CrossRef]

- Holt SR. Approach to treating alcohol use disorder. UpToDate. 2022; published online March 22. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-treating-alcohol-use-disorder (accessed April 19, 2023).

- Prillaman MK. The ‘Breakthrough’ obesity drugs that have stunned researchers. Nature 2023; 613: 16–8.

- Klausen MK, Thomsen M, Wortwein G, Fink-Jensen A. The role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) in addictive disorders. British Journal of Pharmacology 2022; 179: 625–41.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).