1. Introduction

Steroid hormones exhibit their diverse effects on regulating cell metabolism, development, reproductive function, salt-water balance as well as on the functions of the immune, nervous and skeletal systems [

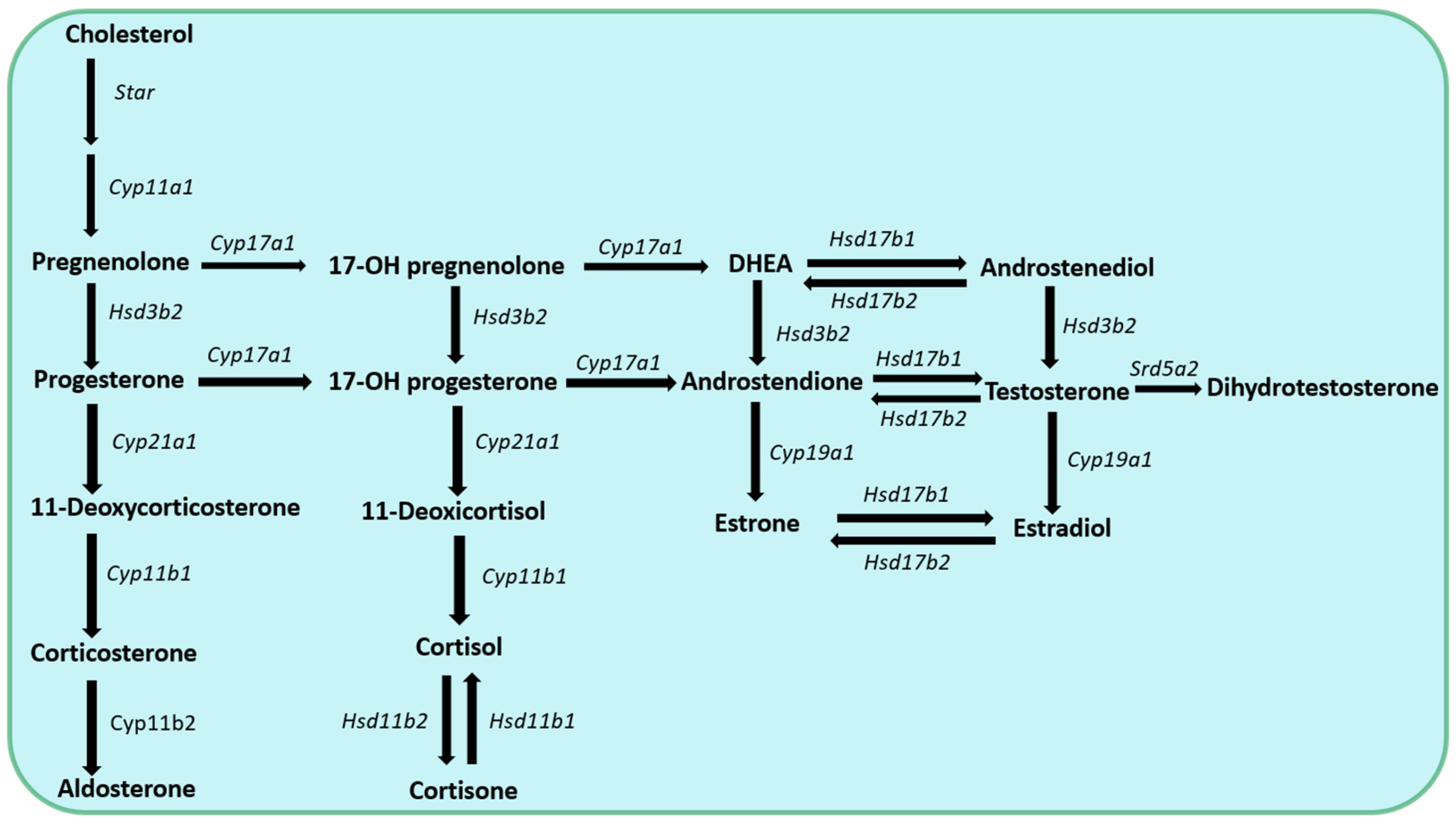

1]. The synthesis of steroid hormones often starts from cholesterol which is also known as

de novo steroidogenesis [

1]. During this process, cholesterol is transported from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria [

2]. Within the mitochondria, a key enzyme, Cyp11a1 is localized, which catalyzes the conversion of cholesterol to other steroid hormones [

2]. Cyp11a1 is also termed as P450 side chain cleavage enzyme and it is responsible for the first and enzymatically rate limiting step of

de novo steroidogenesis [

3], while the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) facilitates the transport of cholesterol into the mitochondria [

4]. The movement of cholesterol across the mitochondrial membrane by StAR protein is believed to be the rate-limiting step of acute steroid hormone synthesis [

4]. The product of Cyp11a1, pregnenolone is the precursor of all other steroids [

3].

Further conversion of the steroid hormones is mediated by two major classes of enzymes namely cytochrome P450 (Cyp) and hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (Hsd) families of enzymes [5-6]. They are located either within the mitochondria or in the cytoplasm of hormone producing cells and electron donor molecules, such as NADH/NAD+ or NADPH/NADP+ are critical cofactors for their function [5-6]. The cellular and molecular mechanisms of de novo steroidogenesis have been extensively studied in glandular organs, i.e., the adrenal cortex, the gonads and the placenta.

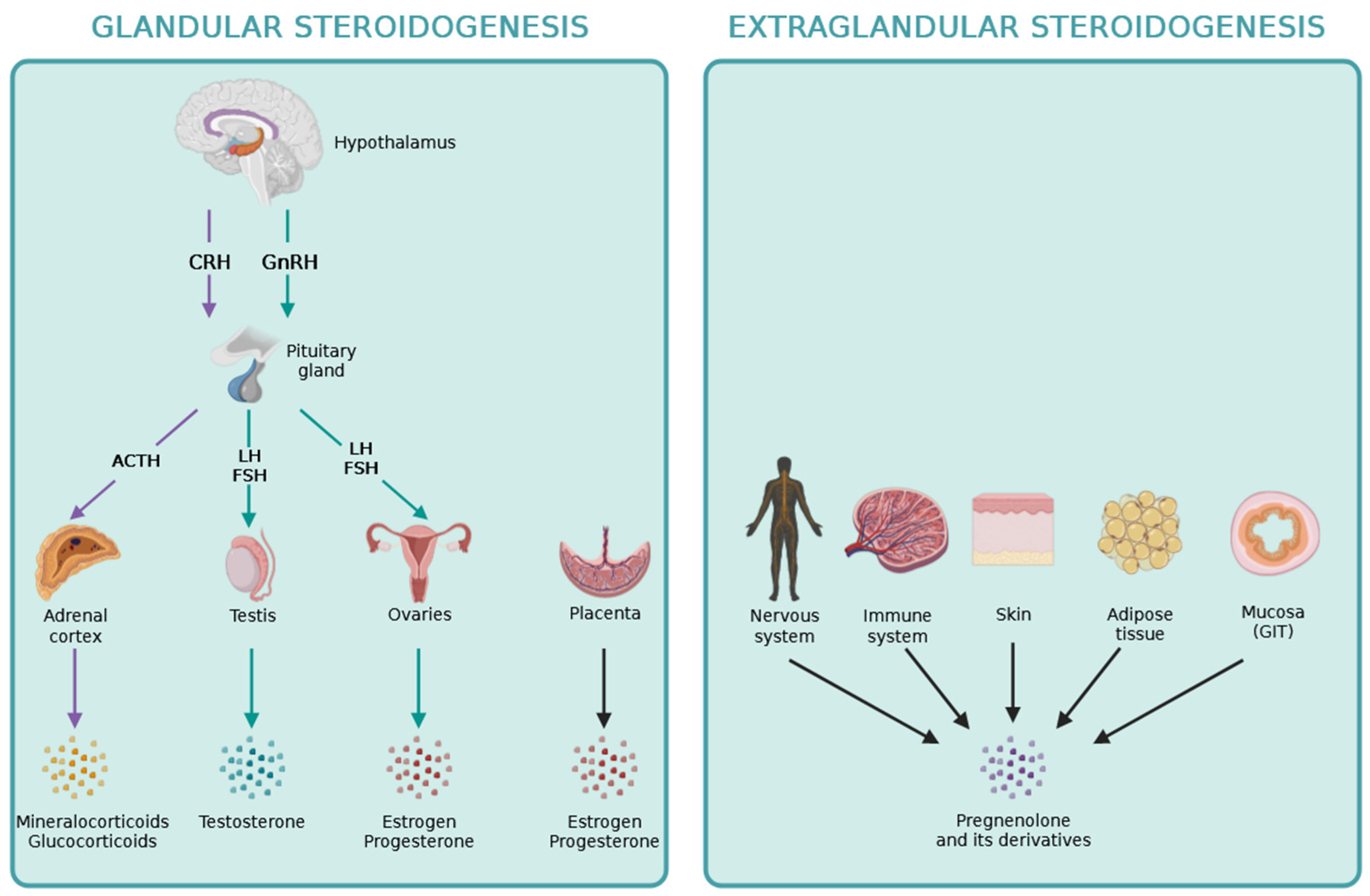

2. Glandular steroidogenesis

Adrenal cortex has three layers and its zona glomerulosa is responsible for the synthesis of mineralocorticoids (e.g., aldosterone), zona fasciculata for the production of glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) and zona reticularis for the secretion of the precursors of sexual steroids (e.g., dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEAS), androstenedione (A4) and 11β-hydroxy-androstenedione (11OHA4)) [7-12]. Mineralocorticoids control salt-water balance, while glucocorticoids regulate cellular metabolism and key functions of both the innate and adaptive immune system.

Steroidogenesis in the gonads is important for the production of androgens, estrogens, and progestogens. Gonadal steroidogenesis in the testis occurs within the Leydig cells and it is responsible for the production of androgens [

13]. Steroidogenesis in the ovary takes place in the theca interna and granulosa cells and results in the production of estrogens [

14]. Additionally, corpus luteum plays an important role in the production of progestogens [

15]. Androgens (e.g., testosterone and dihydrotestosterone), estrogens (e.g., estrone, estradiol and estrone), progestogens (e.g., progesterone) regulate reproductive functions. Estrogens and progestogens can also be synthesized by the placenta in pregnant women [

16].

The hypothalamic-pituitary axis regulates the production of steroid hormones by the adrenal cortex, gonads and placenta. Briefly, the hypothalamus produces releasing hormones, like CRH and GnRH which stimulate the secretion of adenohypophyseal or trophormones by the anterior lobe of the pituitary [1-2]. In turn, the trophormones, such as ACTH, FSH and LH stimulate the steroidogenic gland to produce steroid hormones, which complete the system by having a negative feedback effect on the hypothalamus and pituitary, by inhibiting further stimulation of peripheral glands [1-2]. Estrogens can also exert positive feedback on the hypothalamus-pituitary axis during LH surge before the ovulation within the ovarian cycle [

14].

Pregnenolone is the precursor for all steroid hormones and the synthetic pathways for these steroid hormones are described in detail in

Figure 1. Recently, pregnenolone and its derivates during the process of extraglandular steroidogenesis have been discovered playing locally important roles within different other tissues, including the skin, the adipose tissue, the intestine, as well as the nervous and immune systems [17-18].

3. Extraglandular steroidogenesis

De novo steroidogenesis taking place in other organs besides the adrenals, gonads and placenta are termed extraglandular steroidogenesis [

18]. The role of extraglandular steroidogenesis in the nervous and immune systems, the skin, the adipose tissue, and in the intestine has been reported previously as it is indicated in

Figure 2. The identification of local extraglandular steroidogenesis has been recently revitalizing the field.

3.1. Local steroidogenesis within the thymus

Groundbreaking work by Ashwell and his colleagues gave us the first evidence for extraglandular steroidogenesis taking place in the thymus and shed light to a novel area of steroid hormone research [

19]. De novo glucocorticoid synthesis ocurring in thymic epithelial cells was shown to be important for antigen-specific T cell selection by providing a survival cue against cell death induced by too strong TCR activation during negative selection, allowing positively selected thymocytes to survive [

19]. Further, inhibition of thymic corticosterone production was described to enhance TCR activation-induced apoptosis and enhanced negative selection of T cells [

19]. Besides thymic epithelial cells, mature T cells are also capable of synthesizing glucocorticoids, which will be discussed in detail later in the next chapters.

3.2. Local steroidogenesis within the nervous system

Next evidence indicated that locally produced steroids, so called neurosteroids, could play important roles in the nervous system. In these studies, cholesterol transporting StAR protein was found to be expressed within neurons and glial cells in both mouse and human brains. Moreover, glial StAR co-localized with Cyp11a1 and it proved to be inducible with forskolin or dibutyryl cAMP [

20]. De novo synthetized pregnenolone and its derivates were able to modify neuronal activity in further experiments by modulating GABA

A receptor function and had analgesic, sedative and anesthetic properties in the experimental animals [

21].

3.3. Local steroidogenesis within the immune system

According to latest data, besides thymic epithelial cells, some immune cells are also capable of synthesizing and metabolizing steroid hormones [

22]. Synovial macrophages were described to express functional androgen receptors in both male and female, as well as they were capable of metabolizing testosterone to active dihydrotestosterone [

23]. In another study, human alveolar macrophages were shown to convert androstenedione to androgens, which could regulate their phagocytic activity [

24]. Mouse macrophages were also detected to be able to produce androstenedione, testosterone and estrogens depending on the influence by local factors, e.g. lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [

25].

Further, accumulating evidence indicated the effect of steroid hormones on NK cells [26-35]. Krukowski and her collegaues described, that release of glucocorticoids lead to suppression of NK cell activity and alteration of their cytokine production [

26]. Glucocorticoids regulate NK cell function at least in part via epigenetic mechanisms, e.g. by decreasing the accessibility of promoters of interferon gamma (IFNγ), perforins and granzyme B [26-28]. In another study, administration of exogenous glucocorticoids also decreased the surface expression of NK cell activating receptors NKp30 and NKp46 [

29]. Importantly, endogenous glucocorticoids upregulate checkpoint receptor PD-1 expression on NK cells during pathologic conditions and in disease progression [30-31]. It was also demonstrated, that NK cells express estrogen receptors and can respond to estrogens [

32]. Suprisingly, estradiol regulates NK cell activity via estrogen receptor (ER) beta, but not ERα [

32]. Further, NK cells play important roles during pregnancy, where estrogens and progesterone increase the expression of integrins and selectins [33-34] as well as chemokine receptors on NK cells [

35].

Dendritic cells were also indicated to be regulated by steroid hormones [

36]. Glucocorticoids induce a tolerogenic phenotype in dendritic cells [

37] by both controlling the maturation [38-39] and apoptosis of dendritic cells [40-41]. Further, exogenous glucocorticoids inhibit antigen uptake and processing by dendritic cells [42-43]. In contrast, endogenous glucocorticoids suppress dendritic cell-derived cytokine secretion [

44]. On the other hand, estrogens promote the differentiation of dendritic cells from bone marrow precursors [

45], while progesterone during pregnancy reverts the effects of estrogen, leading to a more tolerogenic dendritic cell phenotype [

46].

Steroid hormones influence both the development and function of T and B cells. According to latest data, endogenous glucocorticoids enhance interleukin-7 receptor signaling in T lymphocytes during their development [

47]. Importantly, exogenous glucocorticoids suppress both Th

1 [

48] and Th

2 responses [

49] via regulation of key transcription factors, T-bet and GATA3. Glucocorticoids also inhibit CD8

+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes by upregulating the expression of inhibitory receptors, e.g. PD-1 [

50]. Further, glucocorticoids induce the development and enhance the function of immunosuppressive regulatory T (Treg) cells [51-54]. In pregnant women, glucocorticoids together with estrogens increased Treg numbers in peripheral blood [

54]. Testosterone and estrogens regulate the function of T and B lymphocytes too [

55]. Estrogens enhance INFγ secretion by Th

1 cells [

56], but inhibit pro-inflammatory Th

17 [

57] and cytotoxic CD8

+ T cells [

58]. Glucocorticoids also block B cell development by inducing apoptosis of B cells [

59], while testosterone and estrogens has an opposite effect on B cell maturation [60-61].

Above mentioned data indicated the ability of immune cells to respond and convert steroids. However, immune cells can also synthetize steroid hormones according to the most recent results. So called de novo steroidogenesis was described in Th

2 cells within the tumor microenvironment [

62]. In these studies, immune cell-mediated steroidogenesis was proposed to elicit local immunosuppression via the inhibition of anti-tumorigenic immune cell subsets and promoted solid tumor growth [

63]. The authors implicated pregnenolone as a "lymphosteroid" produced by Th

2 lymphocytes. They also speculated that this de novo steroidogenesis might be an intrinsic characteristic of Th

2 responses hijacked by cancer cells to actively induce tumor immunosupression [62-63].

3.4. Local steroidogenesis within the skin

Hannen and her colleagues demonstrated that primary human keratinocytes could metabolize pregnenolone to cortisol [

64]. They also showed that epidermis and keratinocytes express all the enzymes required for cortisol synthesis, including Cyp11a1, Cyp17a1, Hsd3b2, Cyp21 and Cyp11b1 [

64]. Further, they showed that human skin expresses cholesterol transporter StAR. The expression of StAR was found to be aberrant in skin disorders, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, suggesting dysregulation of steroid hormone synthesis in patients too [

65].

3.5. Local steroidogenesis within the adipose tissue

Adipose tissue is one of the largest endocrine tissues of the body and it was shown to be an active site for steroid hormone metabolism and storage. According to recent data, steroid hormone precursors delivered to adipose tissue are further converted locally to regulate tissue metabolism and systemic steroid hormone levels [66-67]. Moreover, it was demonstrated that adipose tissue could express the enzymatic machinery for de novo steroidogenesis [

66]. A study by Byeon and Lee provided evidence for the expression of key steroidogenic enzymes, including Hsd3b2, Cyp17a1, Cyp17b1 and Cyp19 both in male and female rat adipose tissues [

66]. Local production of steroid hormones by adipocytes derived from mouse 3T3-L1 cells was also reported in another paper [

67]. These studies suggest that adipose tissue is not only a target of steroids, but can also de novo synthetize steroid hormones.

3.6. Local steroidogenesis within the intestinal mucosa

Finally, accumulating evidence indicated the role of steroid hormone synthesis within the intestinal epithelium in the regulation of immune homeostasis as well as in the development of intestinal tumors and inflammatory bowel disease. In a study by Cima et al., authors report that epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa express steroidogenic enzymes and release glucocorticoids, e.g., corticosterone in response to T cell activation [

68]. Intestinal mucosa-derived corticosterone exhibited an inhibitory role on T cells and in the absence of mucosal glucocorticoids enhanced T cell activation was observed in a mouse model of gastrointestinal viral infection [

69]. Furthermore, liver receptor homolog 1 (Lrh1), which transcriptionally regulates the expression of steroidogenic enzymes such as Cyp11a1, Cyp17, Hsd3b2 and Cyp11b1 was implicated in the development of colon cancer [

70]. Reduced expression of Lrh1 was observed in colon biopsies from patients with inflammatory bowel disease [

71].

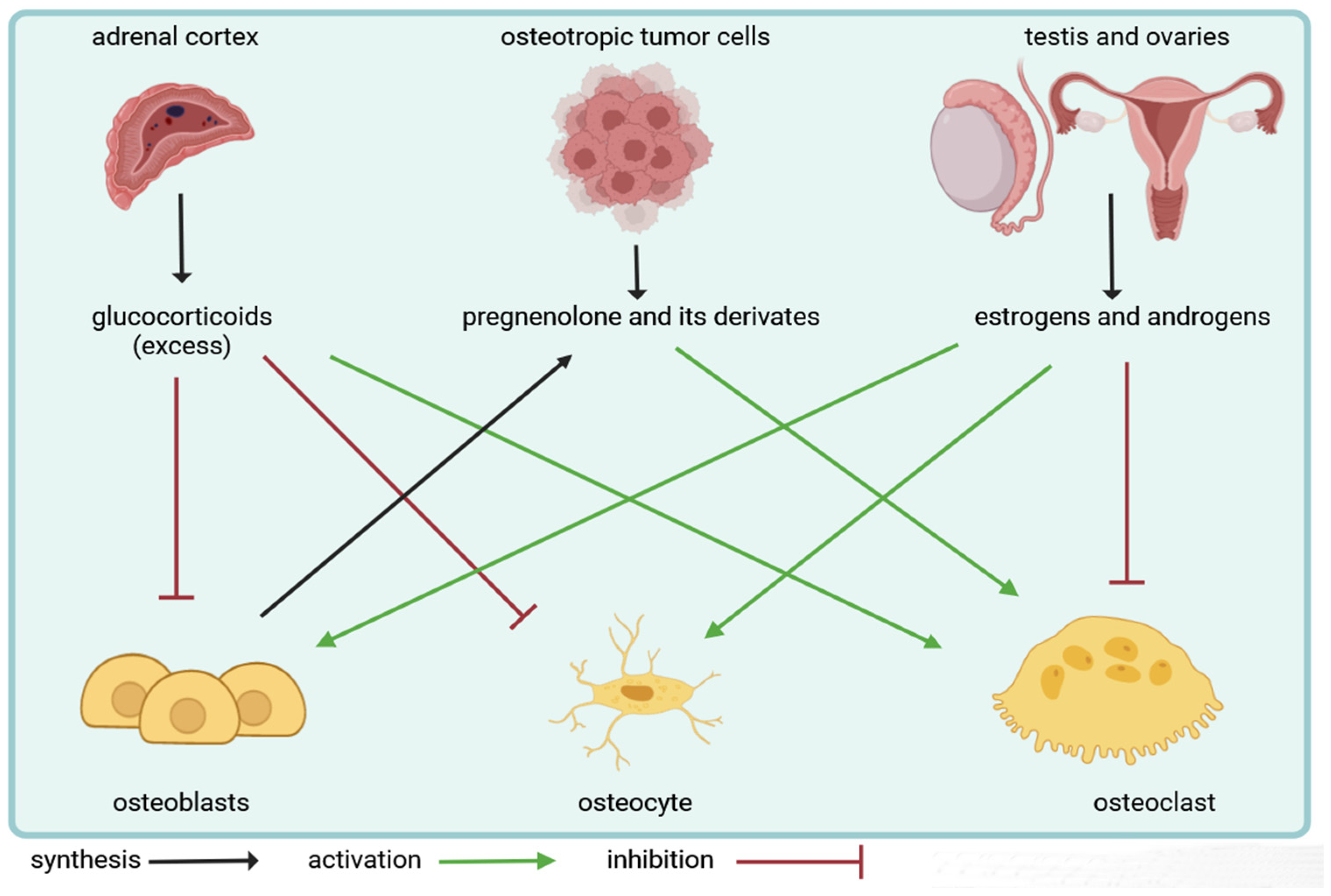

4. Local effects of steroid hormones on bone cells

Steroid hormones play an important role in the bone microenvironment. Glucocorticoids and sexual steroids can regulate the cellular composition of bone tissue. They exert a direct effect on bone-forming osteoblasts, while the actions of steroid hormones on bone-resorbing osteoclasts are rather indirect and mediated by osteoblasts. Additionally, they influence the survival of osteocytes and alter the tight coupling between bone formation and resorption, also known as bone remodeling. Importantly, both glandular and extraglandular steroidogenesis have an impact on bone cells and can regulate skeletal homeostasis according to recent evidence.

4.1. Role of steroid hormones on osteoblasts

Osteoblasts are terminally differentiated mononuclear cells of mesenchymal origin that can synthetize both the organic and inorganic phase of the bone. Osteoblast development is critically dependent on the Wnt/β-catenin and bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp) signaling pathways [

72]. Formation of new bone is mediated by osteoblasts via release of structural proteins (e.g., type I collagen, osteonectin, osteocalcin) and by also driving the deposition of hydroxyapatite crystals by the expression of alkaline phosphatase [

72].

4.1.1. Effects of glucocorticoids on osteoblasts

Osteoblasts are the main cellular targets of glucocorticoids in the skeletal system. Exposure to supraphysiological levels of glucocorticoids restrict osteoblastogenesis and glucocorticoid excess shorten the lifespan of mature osteoblasts by promoting their apoptosis [

73]. Further, high levels of cortisol can diverge stromal progenitor cell development towards adipogenesis [

73]. Glucocorticoids regulate the survival and lifespan of osteoblasts by endocrine as well as autocrine and paracrine effects [

73]. Glucocorticoids were shown to inhibit the secretion of Wnt proteins (e.g., Wnt7b, Wnt10, Wnt16), and BMP proteins (e.g., Bmp2) [74-76]. Moreover, suppression of growth factors (e.g., insulin-like growth factor I, Igf-I) and cytokines (e.g., interleukin-11) also contribute to the inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on osteoblasts [77-79].

4.1.2. Effects of sex steroids on osteoblasts

Estrogens and androgens are important regulators of bone metabolism [

80]. Estrogen acts via two receptors, namely estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERβ) [

81]. ERα in osteoblasts was found to be responsible for the majority of protective effects of estrogens and promote cortical bone accrual in response to mechanical stimulus [

82]. Estrogens were also demonstrated to inhibit osteoblast apoptosis and increase osteoblast lifespan [

83]. At the molecular level, interference with MAPK pathways and transcription factors such as c-Jun and c-Fos mediate the effects of estrogens on reducing apoptosis of osteoblast [

84]. Estrogens can also modulate Wnt signaling in osteoblasts by regulating the levels of sclerostin, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling. Clinical studies have shown that the treatment of postmenopausal women with selective estrogen receptor modulators, such as raloxifene, leads to decreased sclerostin levels in patients [

80]. Vica versa, inhibition of sclerostin by a humanized monoclonal antibody called romosozumab could enhance bone formation and stop bone loss in a study of postmenopausal women, similar to the effects of estrogen therapy [

80].

While estrogen is the key hormonal regulator of bone metabolism not only in women, but also in men, Leydig cells can also regulate bone homeostasis not only by testosterone secretion. Leydig cells are able to produce insulin-like 3 factor (Insl3), which stimulates osteoblast function [

85]. Further, Leydig cells can also contribute to the synthesis of active vitamin D

3 by enhancing its 25-hydroxylation [

85]. As a consequence, male hypogonadism is associated with low levels of Insl3 and an increased risk of osteoporosis in patients [

85].

4.2. Role of steroid hormones on osteocytes

Osteocytes are long-lived cells derived from osteoblasts that are embedded in the bone matrix and can regulate bone remodeling upon changes to the mechanical forces acting on bone [

86]. Importantly, osteocytes reside within the bone tissue and account for the majority of all bone cells [

87]. They have long been considered quiescent bystander cells compared to osteoblasts and osteoclasts, however, recent studies demonstrated that osteocytes play a central role in regulating the dynamic interactions between bone cells [

88]. For example, besides osteoblasts, osteocytes are the other major cellular source of RANKL a key growth factor for the development of osteoclasts [

88]. Increasing number of evidence suggests that osteocyte abnormal function plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of bone diseases, such osteoporosis [86-88].

4.2.1. Effects of glucocorticoids and sex steroids on osteocytes

Osteocytes are important cellular targets of steroid hormones. Glucocorticoids and sexual steroids influence the development and lifespan of osteocytes. Manolagas and colleagues showed that oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) inhibit osteoblastogenesis and decrease the survival of osteocytes [89-92]. Estrogens and androgens decrease the level of intracellular ROS, while supraphysiological levels of glucocorticoids increase it in osteoblasts and osteocytes [89-92]. The main effect of estrogens is to decrease RANKL/OPG ratio, while excess of glucocorticoids increases it via osteoblasts and osteocytes. It is also observed that gonadal steroid deficiency in patients enhances oxidative stress [

83]. As a consequence, antioxidant treatment can prevent bone loss associated with estrogen or androgen deficiency in experimental animals [

83]. Therefore, authors concluded that age-related changes in glandular steroidogenesis and local ROS production, might contribute to the pathogenesis of bone diseases, such as osteoporosis.

4.3. Role of steroid hormones on osteoclasts

Osteoclasts are multinuclear cells of hematopoietic origin that can resorb the bone [

93]. A key factor regulating osteoclast development is receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK) ligand (RANKL) produced by stromal cells in the bone microenvironment, such as osteoblasts and osteocytes [

94]. However, RANKL can also be expressed by a number of hematopoietic cells (e.g. T cell and B cells) as well as by certain tumor cells [

94]. Osteprotegerin (OPG), a decoy receptor for RANKL is also secreted by osteoblast like cells and it blocks the interaction of RANKL with its receptor RANK, leading to the inhibition of osteoclastogenesis [

93]. RANKL/OPG ratio determines the physiological balance of bone formation and turnover, with a higher ratio promotinig excessive bone loss [

93]. Besides RANKL, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) is also a critical factor for osteoclast precursor cell survival and differentiation [

93]. During the process of bone remodeling, osteoclast develops a tight connection with the bone surface (by forming an actin ring structure), and then both the organic and inorganic matrix components break down due to the activity of osteoclasts by simulaneous release of hydrochlorous acid and digestive enzymes (cathepsin K and matrix metalloproteases) into the resorption pit [

93].

4.3.1. Effects of glucocorticoids and sex steroids on osteoclasts

Glucocorticoids influence the development and survival of osteoclasts mainly indirectly via the osteoblast by modulating the expression of RANKL/OPG [

83]. However, for estrogens, both direct and indirect effects on osteoclasts were described. Estrogens can suppress RANKL expression by osteoblasts, osteocytes, T and B cells as well as increase production of the decoy receptor, OPG. Estrogens were also found to be able to modulate the levels of osteoclastogenic cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α and M-CSF) [95-101]. In addition, recent studies also demonstrated the presence of estrogen receptors in osteoclasts [102-103]. On the other hand, the lack of estrogens promotes RANKL expression on osteoblasts and osteocytes, leading to enhanced bone resorption. This excessive bone loss in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis can be reversed by treatment with denosumab, a human monoclonal antibody against RANKL [

104]. Finally, locally produced steroid hormones could also exert an effect on bone cells according to latest data. Details of this pathway will be discussed in the next chapter.

4.4. Role of extraglandular steroidogenesis in the bone microenvironment

Recent evidence indicated, that osteoblasts not only respond to steroid hormones but they can also synthetize testosterone from DHEA under pathological conditions during the development of prostate cancer bone metastases [

105]. Intratumoral production of the adrenal androgen precursor DHEA allowed bone-forming osteoblasts to convert and secrete androgens to drive the development of osteosclerotic skeletal lesions [

105]. Both human and murine osteoblasts were found to express Hsd3b2 and Cyp17a1 enzymes, suggesting that osteoblasts are capable of generating testosterone from DHEA [

105].

Similarly, our group recently identified a key role for extranglandular

de novo steroidogenesis in osteolytic skeletal lesion formation by breast cancer cells [

106]. Osteotropic tumor cells that expressed Cyp11a1 were capable of forming bone metastases in mice [

106]. Further, pregnenolone, the product of Cyp11a1 activity was detected in high concentrations in the supernatants of several human and mouse osteotropic cancer cell lines [

106]. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of Cyp11a1 in tumor cells protected animals from skeletal lesion formation and tumor-induced osteolysis [

106]. Importantly, cancer cell-derived pregnenolone was able to drive the development of bone-resorbing osteoclasts by inducing the fusion of osteoclast precursors [

106]. This effect of pregnenolone was mediated by a molecule called P4hb [

106]. Moreover, higher expression of Cyp11a1 in primary tumors were associated with worst prognosis in patients [

106].

These are the first evidences for a unique role of extraglandular steroidogenesis occuring within the bone microenvironment during tumor development. However, future studies are required to better understand the role of local steroid production in the skeletal system under both physiological and pathological conditions.

Figure 3. summarizes the effects of glandular and extraglandular steroidogenesis on bone cells.

4.5. Role of secosteroids in the modulation of bone homeostasis

Besides being a lipid soluble vitamin, vitamin D is also a steroid hormone. Precursors of active vitamin D is either produced in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol upon exposure to UVB light or obtained from plants and animal food as ergocalciferol (vitamin D

2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D

3) [107-108]. The latter is then transported to the liver, where first hydroxylation occurs and results in the generation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D

3. Finally, vitamin D

3 is activated by a second hydroxylation step in the kidneys. Although the primary function of vitamin D

3 is the regulation of calcium metabolism, it also plays a key role in the regulation of bone homeostasis [

109]. Importantly, it controls both bone formation and resorption by promoting osteoblast development and regulating the expression of RANKL on osteoblasts and osteocytes [110-111].

Recently a surprising role of Cyp11a1 has been discovered in the metabolism of 7-dehydrocholestrol, precursor of active vitamin D

3. Namely, Cyp11a1 enzyme activity could lead to the generation of vitamin D

3 hydroxyderivatives (so called secosteroids) [

112]. While Cyp11a1-derived hydroxyderivatives of vitamin D

3 are present in human serum and detected in the epidermis, we just begin to understand the biological role of this pathway [

112]. Recently, Postlethwaite and colleagues reported that Cyp11a1-derived 20-hydroxyvitamin D

3 can decrease joint damage in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis by changing inflammatory cytokine levels and altering lymphocyte subpopulations in peripheral blood of animals [

113]. The authors propose 20-hydroxyvitamin D

3 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other inflammatory joint diseases, however further experiments are required to better understand the role of secosteroids in the development of bone diseases [

113].

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

Steroid hormones are key regulators of homeostasis and control endocrine functions in the body [

1]. Steroid production is mainly studied in the adrenal zona glomerulosa, fasciculata and reticularis cells, testicular Leydig cells, ovarian granulosa as well as theca interna and placental syncytiotrophoblast cells [

2]. Besides the centrally regulated glandular steroidogenesis, local

de novo steroid production also occurs in several other tissues [17-18]. Among these, pregnenolone and its derivates play an important role in the regulation of bone homeostasis and bone cells, e.g., osteoblasts, osteocytes and osteoclasts respond to these molecules. Therefore, understanding the cellular and molecular effects of steroid hormones in the skeletal system is expected to facilitate the development of new therapies for the treatment of bone disease.

Novel discoveries and innovations in the area of steroid hormone research are promoted by technological and methodological advancement in the field. To identify locally produced steroid hormones and novel steroid synthesis pathways in different tissues, profiling and quantification of all steroid hormones and their metabolites by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry is now widely available. Further, combining mass spectrometry with ChIP sequencing to selectively isolate chromatin-associated proteins may facilitate the understanding of the role of receptors of steroid hormone, which exert their effect by regulating gene expression in target tissues [

18]. Steroidogenic enzyme activity in bone cells can be measured by chemoproteomics-based protein profiling techniques [

114]. Finally, recently developed transgenic mice could be useful tools to study the effect of steroid hormones

in vivo, e.g. the Cyp11a1-H2b-mCherry reporter line [

18] or the Cyp11a1-Gfp-Cre animals [

115].

Last but not least, synthetic steroids are extensively used in the clinical practice as anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs for autoimmune diseases, organ transplantation and in the treatment of leukemia. However, long-term use of these drugs can lead to serious side effects in the skeletal system. Better understanding of local steroidogenesis within the skeletal system and steroid hormone mediated regulation of bone cells may lead to the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies to eliminate undesirable side effects of synthetic steroids, ensuring the maintenance of physiological bone homeostasis.

Author Contributions

L.F.S. and R.R. generated figures in BioRender, D.S.G. wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the NKFIH-FK132971 grant to D.S.G., Bolyai Janos Fellowship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences to D.S.G., the NKFIH-TKP2021-EGA-19 grant to D.S.G. and was also supported by the UNKP-23-5-SE-19 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (NKFIH) to D.S.G.

Acknowledgments

We thank Phillip T. Hawkins, Len R. Stephens, Klaus Okkenhaug, Rahul Roychoudhuri, Attila Mocsai for mentorship and Bidesh Mahata for critical advice on extraglandular steroidogenesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Miller WL, Auchus RJ. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr Rev. 2011;32:81-151.

- Miller WL. Steroid Hormone Synthesis in Mitochondria. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;379:62-73.

- Strushkevich N, MacKenzie F, Cherkesova T, Grabovec I, Usanov S, Park HW. Structural Basis for Pregnenolone Biosynthesis by the Mitochondrial Monooxygenase System. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10139-43.

- Arakane F, Sugawara T, Nishino H, Liu Z, Holt JA, Pain D, et al. Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) retains activity in the absence of its mitochondrial import sequence: implications for the mechanism of StAR action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13731-6.

- Hall PF. Cytochromes P450 and the regulation of steroid synthesis. Steroids 1986;48:133-196.

- Agarwal AK, Auchus RJ. Cellular redox state regulates hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity and intracellular hormone potency. Endocrinology 2005;146:2531-2538.

- Mesiano S, Coulter CL, Jaffe RB. Localization of cytochrome P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage, cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase, and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-isomerase steroidogenic enzymes in human and rhesus monkey fetal adrenal glands: reappraisal of functional zonation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:1184-1189.

- Suzuki T, Sasano H, Takeyama J, Kaneko C, Freije WA, Carr BR, Rainey WE. Developmental changes in steroidogenic enzymes in human postnatal adrenal cortex: immunohistochemical studies. Clin Endocrinol. 2000;53:739–747.

- Endoh A, Kristiansen SB, Casson PR, Buster JE, Hornsby PJ. The zona reticularis is the site of biosynthesis of dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in the adult human adrenal cortex resulting from its low expression of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3558-3565.

- Mapes S, Corbin CJ, Tarantal A, Conley A. The primate adrenal zona reticularis is defined by expression of cytochrome b5, 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase cytochrome P450 (P450c17) and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (reductase) but not 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Δ5-4 isomerase (3β-HSD). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3382-3385.

- Nguyen AD, Mapes SM, Corbin CJ, Conley AJ. Morphological adrenarche in rhesus macaques: development of the zona reticularis is concurrent with fetal zone regression in the early neonatal period. J Endocrinol. 2008;199:367–378.

- Hui XG, Akahira J, Suzuki T, Nio M, Nakamura Y, Suzuki H, Rainey WE, Sasano H. Development of the human adrenal zona reticularis: morphometric and immunocytochemical studies from birth to adolescence. J Endocrinol. 2009;203:241–252.

- Flück CE, Miller WL, Auchus RJ. The 17,20 lyase activity of cytochrome P450c17 from human fetal testis favors the Δ5 steroidogenic pathway. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:3762-3766.

- Voutilainen R, Tapanainen J, Chung BC, Matteson KJ, Miller WL. Hormonal regulation of P450scc (20,22-desmolase) and P450c17 (17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase) in cultured human granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63:202-207.

- Chapman JC, Polanco JR, Min S, Michael SD. Mitochondrial 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) is essential for the synthesis of progesterone by corpora lutea: an hypothesis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:11.

- Chung BC, Matteson KJ, Voutilainen R, Mohandas TK, Miller WL. Human cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme, P450scc: cDNA cloning, assignment of the gene to chromosome 15, and expression in the placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8962-8966.

- Miller WL. Steroidogenesis: Unanswered Questions. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28(11):771-793.

- Chakraborty S, Pramanik J, Mahata B. Revisiting steroidogenesis and its role in immune regulation with the advanced tools and technologies. Genes Immun. 2021, 22(3):125-140.

- Vacchio MS, Papadopoulos V, Ashwell JD. Steroid production in the thymus: implications for thymocyte selection. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1835–46. [CrossRef]

- King SR, Manna PR, Ishii T, Syapin PJ, Ginsberg SD, Wilson K, et al. An essential component in steroid synthesis, the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, is expressed in discrete regions of the brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10613-20.

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565-75.

- Rubinow KB. An intracrine view of sex steroids, immunity, and metabolic regulation. Mol Metab. 2018;15:92-103.

- Milewich L, Kaimal V, Toews GB. Androstenedione metabolism in human alveolar macrophages. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56:920–4.

- Cutolo M, Accardo S, Villaggio B, Barone A, Sulli A, Balleari E, et al. Androgen metabolism and inhibition of interleukin-1 synthesis in primary cultured human synovial macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 1995;4:138–43.

- Schmidt M, Kreutz M, Loffler G, Scholmerich J, Straub RH. Conversion of dehydroepiandrosterone to downstream steroid hormones in macrophages. J Endocrinol. 2000;164:161–9.

- Krukowski K, Eddy J, Kosik KL, Konley T, Janusek LW, Mathews HL. Glucocorticoid dysregulation of natural killer cell function through epigenetic modification. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:239–49.

- Eddy JL, Krukowski K, Janusek L, Mathews HL. Glucocorticoids regulate natural killer cell function epigenetically. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:120–30.

- Morgan DJ, Davis DM. Distinct effects of dexamethasone on human natural killer cell responses dependent on cytokines. Front Immunol. 2017;8:432.

- Vitale C, Chiossone L, Cantoni C, Morreale G, Cottalasso F, Moretti S, et al. The corticosteroid-induced inhibitory effect on NK cell function reflects down-regulation and/or dysfunction of triggering receptors involved in natural cytotoxicity. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3028–38.

- Quatrini L, Wieduwild E, Escaliere B, Filtjens J, Chasson L, Laprie C, et al. Endogenous glucocorticoids control host resistance to viral infection through the tissue-specific regulation of PD-1 expression on NK cells. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:954–62.

- Quatrini L, Vacca P, Tumino N, Besi F, Di Pace AL, Scordamaglia F, et al. Glucocorticoids and the cytokines IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 present in the tumor microenvironment induce PD-1 expression on human natural killer cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:349–60.

- Curran EM, Berghaus LJ, Vernetti NJ, Saporita AJ, Lubahn DB, Estes DM. Natural killer cells express estrogen receptor-alpha and estrogen receptor-beta and can respond to estrogen via a non-estrogen receptor-alpha-mediated pathway. Cell Immunol. 2001;214:12–20.

- Chantakru S, Wang WC, van den Heuvel M, Bashar S, Simpson A, Chen Q, et al. Coordinate regulation of lymphocyte-endothelial interactions by pregnancy-associated hormones. J Immunol. 2003;171:4011–9.

- Gibson DA, Greaves E, Critchley HO, Saunders PT. Estrogen-dependent regulation of human uterine natural killer cells promotes vascular remodelling via secretion of CCL2. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1290–301.

- Sentman CL, Meadows SK, Wira CR, Eriksson M. Recruitment of uterine NK cells: induction of CXC chemokine ligands 10 and 11 in human endometrium by estradiol and progesterone. J Immunol. 2004;173:6760–6.

- Piemonti L, Monti P, Allavena P, Sironi M, Soldini L, Leone BE, et al. Glucocorticoids affect human dendritic cell differentiation and maturation. J Immunol. 1999;162:6473–81.

- Xia CQ, Peng R, Beato F, Clare-Salzler MJ. Dexamethasone induces IL-10-producing monocyte-derived dendritic cells with durable immaturity. Scand J Immunol. 2005;62:45–54.

- Matyszak MK, Citterio S, Rescigno M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Differential effects of corticosteroids during different stages of dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1233–42.

- Larange A, Antonios D, Pallardy M, Kerdine-Romer S. Glucocorticoids inhibit dendritic cell maturation induced by Toll-like receptor 7 and Toll-like receptor 8. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91:105–17.

- Boor PP, Metselaar HJ, Mancham S, Tilanus HW, Kusters JG, Kwekkeboom J. Prednisolone suppresses the function and promotes apoptosis of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Am J Transpl. 2006;6:2332–41.

- Shodell M, Siegal FP. Corticosteroids depress IFN-alpha-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells in human blood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:446–8. [CrossRef]

- Holt PG, Thomas JA. Steroids inhibit uptake and/or processing but not presentation of antigen by airway dendritic cells. Immunology. 1997;91:145–50.

- Pan J, Ju D, Wang Q, Zhang M, Xia D, Zhang L, et al. Dexamethasone inhibits the antigen presentation of dendritic cells in MHC class II pathway. Immunol Lett. 2001;76:153–61.

- Li CC, Munitic I, Mittelstadt PR, Castro E, Ashwell JD. Suppression of dendritic cell-derived IL-12 by endogenous glucocorticoids is protective in LPS-induced sepsis. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002269.

- Paharkova-Vatchkova V, Maldonado R, Kovats S. Estrogen preferentially promotes the differentiation of CD11c+ CD11b(intermediate) dendritic cells from bone marrow precursors. J Immunol. 2004;172:1426–36.

- Xiu F, Anipindi VC, Nguyen PV, Boudreau J, Liang H, Wan Y, et al. High physiological concentrations of progesterone reverse estradiol-mediated changes in differentiation and functions of bone marrow derived dendritic cells. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0153304.

- Shimba A, Cui G, Tani-Ichi S, Ogawa M, Abe S, Okazaki F, et al. Glucocorticoids drive diurnal oscillations in T cell distribution and responses by inducing interleukin-7 receptor and CXCR4. Immunity. 2018;48:286–98.e6.

- Franchimont D, Galon J, Gadina M, Visconti R, Zhou Y, Aringer M, et al. Inhibition of Th1 immune response by glucocorticoids: dexamethasone selectively inhibits IL-12-induced Stat4 phosphorylation in T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164:1768–74.

- Liberman AC, Druker J, Refojo D, Holsboer F, Arzt E. Glucocorticoids inhibit GATA-3 phosphorylation and activity in T cells. FASEB J. 2009;23:1558–71.

- Maeda N, Maruhashi T, Sugiura D, Shimizu K, Okazaki IM, Okazaki T. Glucocorticoids potentiate the inhibitory capacity of programmed cell death 1 by up-regulating its expression on T cells. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:19896–906.

- Ugor E, Prenek L, Pap R, Berta G, Ernszt D, Najbauer J, et al. Glucocorticoid hormone treatment enhances the cytokine production of regulatory T cells by upregulation of Foxp3 expression. Immunobiology. 2018;223:422–31.

- Kim D, Nguyen QT, Lee J, Lee SH, Janocha A, Kim S, et al. Anti-inflammatory roles of glucocorticoids are mediated by Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells via a miR-342-dependent mechanism. Immunity. 2020;53:581–96.e5.

- Pandolfi J, Baz P, Fernandez P, Discianni Lupi A, Payaslian F, Billordo LA, et al. Regulatory and effector T-cells are differentially modulated by Dexamethasone. Clin Immunol. 2013;149:400–10.

- Engler JB, Kursawe N, Solano ME, Patas K, Wehrmann S, Heckmann N, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor in T cells mediates protection from autoimmunity in pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E181–90.

- Lelu K, Laffont S, Delpy L, Paulet PE, Perinat T, Tschanz SA, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha signaling in T lymphocytes is required for estradiol-mediated inhibition of Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation and protection against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2011;187:2386–93.

- Maret A, Coudert JD, Garidou L, Foucras G, Gourdy P, Krust A, et al. Estradiol enhances primary antigen-specific CD4 T cell responses and Th1 development in vivo. Essential role of estrogen receptor alpha expression in hematopoietic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:512–21.

- Chen RY, Fan YM, Zhang Q, Liu S, Li Q, Ke GL, et al. Estradiol inhibits Th17 cell differentiation through inhibition of RORgammaT transcription by recruiting the ERalpha/REA complex to estrogen response elements of the RORgammaT promoter. J Immunol. 2015;194:4019–28.

- Schleimer RP, Jacques A, Shin HS, Lichtenstein LM, Plaut M. Inhibition of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity by anti-inflammatory steroids. J Immunol. 1984;132:266–71.

- Gruver-Yates AL, Quinn MA, Cidlowski JA. Analysis of glucocorticoid receptors and their apoptotic response to dexamethasone in male murine B cells during development. Endocrinology. 2014;155:463–74.

- Wilhelmson AS, Lantero Rodriguez M, Stubelius A, Fogelstrand P, Johansson I, Buechler MB, et al. Testosterone is an endogenous regulator of BAFF and splenic B cell number. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2067.

- Fu Y, Li L, Liu X, Ma C, Zhang J, Jiao Y, et al. Estrogen promotes B cell activation in vitro through down-regulating CD80 molecule expression. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27:593–6.

- Mahata B, Zhang X, Kolodziejczyk AA, Proserpio V, Haim-Vilmovsky L, Taylor AE, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals T helper cells synthesizing steroids de novo to contribute to immune homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2014;22;7(4):1130-42.

- Mahata B, Pramanik J, van der Weyden L, Polanski K, Kar G, Riedel A, et al. Tumors induce de novo steroid biosynthesis in T cells to evade immunity. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3588.

- Hannen RF, Michael AE, Jaulim A, Bhogal R, Burrin JM, Philpott MP. Steroid synthesis by primary human keratinocytes; implications for skin disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404:62–7.

- Slominski A, Zbytek B, Nikolakis G, Manna PR, Skobowiat C, Zmijewski M, et al. Steroidogenesis in the skin: implications for local immune functions. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;137:107–23.

- Byeon HR, Lee SH. Expression of steroidogenesis-related genes in rat adipose tissues. Dev Reprod. 2016;20:197–205.

- Li J, Papadopoulos V, Vihma V. Steroid biosynthesis in adipose tissue. Steroids. 2015;103:89–104.

- Cima I, Corazza N, Dick B, Fuhrer A, Herren S, Jakob S, et al. Intestinal epithelial cells synthesize glucocorticoids and regulate T cell activation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1635–46.

- Ahmed A, Schmidt C, Brunner T. Extra-adrenal glucocorticoid synthesis in the intestinal mucosa: between immune homeostasis and immune escape. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1438.

- Sirianni R, Seely JB, Attia G, Stocco DM, Carr BR, Pezzi V, et al.. Liver receptor homologue-1 is expressed in human steroidogenic tissues and activates transcription of genes encoding steroidogenic enzymes. J Endocrinol. 2002;174:R13–7.

- Bayrer JR, Wang H, Nattiv R, Suzawa M, Escusa HS, Fletterick RJ, et al. LRH-1 mitigates intestinal inflammatory disease by maintaining epithelial homeostasis and cell survival. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4055.

- Zhou H, Mak W, Zheng Y, Dunstan CR, Seibel MJ. Osteoblasts Directly Control Lineage Commitment of Mesenchymal Progenitor Cells Through Wnt Signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1936–45.

- Gado M, Baschant U, Hofbauer LC, Henneicke H. Bad to the Bone: The Effects of Therapeutic Glucocorticoids on Osteoblasts and Osteocytes. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:835720.

- Mak W, Shao X, Dunstan CR, Seibel MJ, Zhou H. Biphasic Glucocorticoid-Dependent Regulation of Wnt Expression and its Inhibitors in Mature Osteoblastic Cells. Calcified Tissue Int. 2009;85:538–45.

- Hildebrandt S, Baschant U, Thiele S, Tuckermann J, Hofbauer LC, Rauner M. Glucocorticoids Suppress Wnt16 Expression in Osteoblasts In Vitro and In Vivo. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8711.

- Luppen CA, Smith E, Spevak L, Boskey AL, Frenkel B. Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 Restores Mineralization in Glucocorticoid-Inhibited MC3T3-E1 Osteoblast Cultures. J Bone Mineral Res. 2003;18:1186–97.

- Delany AM, Durant D, Canalis E. Glucocorticoid Suppression of IGF I Transcription in Osteoblasts. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1781–9.

- Pereira RMR, Delany AM, Canalis E. Cortisol Inhibits the Differentiation and Apoptosis of Osteoblasts in Culture. Bone 2001;28:484–90.

- Rauch A, Seitz S, Baschant U, Schilling AF, Illing A, Stride B, et al. Glucocorticoids Suppress Bone Formation by Attenuating Osteoblast Differentiation via the Monomeric Glucocorticoid Receptor. Cell Metab. 2010;11:517–31.

- Khosla S, Monroe DG. Regulation of Bone Metabolism by Sex Steroids. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018; 8(1): a031211.

- Sims NA, Clément-Lacroix P, Minet D, Fraslon-Vanhulle C, Gaillard-Kelly M, Resche-Rigon M, Baron R. A functional androgen receptor is not sufficient to allow estradiol to protect bone after gonadectomy in estradiol receptor-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1319–1327.

- Jilka RL, Takahashi K, Munshi M, Williams DC, Roberson PK, Manolagas SC. Loss of estrogen upregulates osteoblastogenesis in the murine bone marrow: evidence for autonomy from factors released during bone resorption. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(9):1942–1950.

- Manolagas SC. Steroids and osteoporosis: the quest for mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(5):1919–1921.

- Khosla S, Oursler MJ, Monroe DG. Estrogen and the Skeleton. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(11): 576–581.

- Ferlin A, Selice R, Carraro U, Foresta C. Testicular function and bone metabolism - beyond testosterone. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2013;9:548–554.

- Bonewald LF. The amazing osteocyte. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:229–238.

- Xiong J, Onal M, Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC, O' Brien CA. Matrix-embedded cells control osteoclast formation. Nat Med. 2011;17:1235–1241.

- Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Fukunaga T, Kurata K, Oh-hora M, Feng JQ, Bonewald LF, Kodama T, Wutz A, Wagner EF, Penninger JM, Takayanagi H. Evidence for osteocyte regulation of bone homeostasis through RANKL expression. Nat Med. 2011;17:1231–1234.

- Manolagas SC, Parfitt AM. For whom the bell tolls: Distress signals from long-lived osteocytes and the pathogenesis of metabolic bone diseases. Bone. 2012;pii:S8756-3282(12)01246-X.

- Manolagas SC. From estrogen-centric to aging and oxidative stress: a revised perspective of the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(3):266–300.

- Almeida M, Han L, Ambrogini E, Bartell SM, Manolagas SC. Oxidative stress stimulates apoptosis and activates NF-kappaB in osteoblastic cells via a PKCbeta/p66shc signaling cascade: counter regulation by estrogens or androgens. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(10):2030–2037.

- Almeida M, Han L, Ambrogini E, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC. Glucocorticoids and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha increase oxidative stress and suppress WNT signaling in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(52):44326–44335.

- Gyori, D., Mocsai, A. Osteoclasts in Inflammation. Compendium of Inflammatory Diseases. Springer, Basel 2016.

- Gyori DS, Mocsai A. Osteoclast Signal Transduction During Bone Metastasis Formation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:507.

- Kimble RB, Vannice JL, Bloedow DC, Thompson RC, Hopfer W, Kung VT, Brownfield C, Pacifici R. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist decreases bone loss and bone resorption in ovariectomized rats. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1959–1967.

- Ammann P, Rizzoli R, Bonjour J, Bourrin S, Meyer J, Vassalli P, Garcia I. Transgenic mice expressing soluble tumor necrosis factor-receptor are protected against bone loss caused by estrogen deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1699–1703.

- Kimble RB, Srivastava S, Ross FP, Matayoshi A, Pacifici R. Estrogen deficiency increases the ability of stromal cells to support murine osteoclastogenesis via an interleukin-1-and tumor necrosis factor-mediated stimulation of macrophage colony-stimulating factor production. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28890–28897.

- Kitazawa R, Kimble RB, Vannice JL, Kung VT, Pacifici R. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor binding protein decrease osteoclast formation and bone resorption in ovariectomized mice. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2397–2406.

- Charatcharoenwitthaya N, Khosla S, Atkinson EJ, McCready LK, Riggs BL. Effect of blockade of TNF-a and interleukin-1 action on bone resorption in early postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:724–729.

- Roggia C, Gao Y, Cenci S, Weitzmann MN, Toraldo G, Isaia G, Pacifici R. Up-regulation of TNF-producing T cells in the bone marrow: a key mechanism by which estrogen deficiency induces bone loss in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13960–13965.

- Cenci S, Weitzmann MN, Roggia C, Namba N, Novack D, Woodring J, Pacifici R. Estrogen deficiency induces bone loss by enhancing T-cell production of TNF-a. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1229–1327.

- Nakamura T, Imai Y, Matsumoto T, Sato S, Takeuchi K, Igarashi K, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Krust A, Yamamoto Y, Nishina H, Takeda S, Takayanagi H, Metzger D, Kanno J, Takaoka K, Martin TJ, Chambon P, Kato S. Estrogen prevents bone loss via estrogen receptor alpha and induction of fas ligand in osteoclasts. Cell. 2007;130:811–823.

- Martin-Millan M, Almeida M, Ambrogini E, Han L, Zhao H, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, O' Brien CA, Manolagas SC. The estrogen receptor-alpha in osteoclasts mediates the protective effects of estrogens on cancellous but not cortical bone. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:323–334.

- Teitelbaum SL. Glucocorticoids and the osteoclast. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(4 Suppl 92):S37-9.

- Moon HH, Clines KL, O'Day PJ, Al-Barghouthi BM, Farber EA, Farber CR, Auchus RJ, Clines GA. Osteoblasts Generate Testosterone From DHEA and Activate Androgen Signaling in Prostate Cancer Cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;36(8):1566-1579.

- Huh JB, Benko P, Sandor LF, Hiraga T, Poliska S, Dobo-Nagy C, Simpson JP, Homer NZM, Mahata B, Gyori DS. De Novo Steroidogenesis in Tumor Cells Drives Bone Metastasis and Osteoclastogenesis. 2023. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4523146. [CrossRef]

- MacLaughlin J, Holick MF. Aging decreases the capacity of human skin to produce vitamin D3. J Clin Invest 1985;76:1536–8.

- Merke J, Milde P, Lewicka S, Hugel U, Klaus G, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. Identification and regulation of 1,25-dihydrox- vitamin D3 receptor activity and biosynthesis of 1,25-dihy- droxyvitamin D3. Studies in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells and human dermal capillaries. J Clin Invest 1989;83:1903–15.

- Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, Tappero R. Parathyroid hormone response to severe vitamin D deficiency is associated with femoral neck bone mineral density: an observational study of 405 women with hip-fracture. Hormones 2016;15(4):527–33.

- Muscogiuri G, Mitri J, Mathieu C, Badenhoop K, Tamer G, Orio F, et al.. Mechanisms in endocrinology: vitamin D as a potential contributor in endocrine health and disease. Eur J Endocrinol 2014;171(3):R101–10.

- Romano F, Serpico D, Cantelli M, Di Sarno A, Dalia C, Arianna R, Lavorgna M, Colao A, Di Somma C. Osteoporosis and dermatoporosis: a review on the role of vitamin D. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1231580.

- Slominski AT, Mahata B, Raman C, Bereshchenko O. Editorial: Steroids and Secosteroids in the Modulation of Inflammation and Immunity. Front Immunol. 2021;12:825577.

- Postlethwaite AE, Tuckey RC, Kim TK, Li W, Bhattacharya SK, Myers LK, Brand DD, Slominski AT. 20S-Hydroxyvitamin D3, a Secosteroid Produced in Humans, Is Anti-Inflammatory and Inhibits Murine Autoimmune Arthritis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:678487.

- Roy S, Sipthorp J, Mahata B, Pramanik J, Hennrich ML, Gavin AC, Ley SV, Teichmann SA. CLICK-enabled analogues reveal pregnenolone interactomes in cancer and immune cells. iScience. 2021;24(5):102485.

- O’Hara L, York JP, Zhang P, Smith LB. Targeting of GFP-Cre to the mouse Cyp11a1 locus both drives cre recombinase expression in steroidogenic cells and permits generation of Cyp11a1 knock out mice. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e84541.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).