Introduction

Cardiac transplantation is an effective therapy for cardiac failure in many patients.1 Recent improvements in immunosuppressive treatments have decreased acute cardiovascular (CV)-related mortality in transplant patients.2 However, cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) resulting in CV-related death (CV death) continues to be a serious cause of allograft loss in patients surviving the initial posttransplant period.2,3 Recent studies indicate that both donor and recipient innate immune responses (IR) participate in initiating and accelerating recipient allorecognition (AR), which can lead to CAV and CV death.3-10 Thus, it is likely that both donor and recipient IR are important participants in the pathogenesis of CAV and CV death.5-10 We hypothesized that donor characteristics and causes of death (COD) with higher IR would have an adverse effect on recipient outcomes including incidence of CAV and CV death. We performed a single-institution retrospective analysis comparing specific donor characteristics associated with heightened donor IR to recipient outcomes. We chose to compare donor factors of significance based on previous publications, including donor age, sex, height, weight, COD, and ischemic time. We used incidence of early antibody-mediated rejection (pAMR) and CV death as outcome variables for the study.11-16

Methods

Database

We obtained institutional review board (IRB) permission to review the donor records of all available cardiac transplant recipients from 1987-2016 in the Intermountain Donor Services (IDS) files. Donors included in the study were those whose records included sufficient information about donor details to allow analysis. The records included demographic characteristics, COD as recorded by the donor institution, results of antibody screening, infectious disease evaluation, and history of autoimmune disease, alcohol use, smoking history and drug use if available. The information was uploaded to a FileMaker Pro 12 (FileMaker, Inc. Santa Clara, CA 95054) database created for this purpose. The Utah Transplant Affiliated Hospitals (UTAH) cardiac transplant database for recipients includes demographic characteristics and details of recipient pathology and outcomes since 1987.15

Patient Population

We analyzed anonymized records of all local adult (age 18-64) donors in the IDS database with transplant dates between 1987 and 2016. Donor records without sufficient clinical information were excluded. We clustered the differing CODs into four categories. The first category contained CODs with multiple injuries involving a motor vehicle (MVA). The second COD category consisted of donors who died of localized traumatic head injuries such as blunt trauma (BHT) or a gunshot wound (GSW) to the head. The third category of COD was anoxic brain injury including drowning and drug related injuries. The final category was intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). We linked these records with their corresponding recipients and recipient outcomes in our database.

Method of Analysis

We compared donor age, COD, and sex with frequency of recipient CV death or retransplantation (according to UNOS criteria) and early pAMR (more than 3 cases within 90 days) using logistic regression, log-rank test of differences, and Tukey Contrast. R version 4.3 (2023) was used for the analysis. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. UNOS criteria for CV death include death from acute rejection, acute myocardial infarction, acute arrhythmia, heart failure, or CAV.16 Early pAMR was used as an outcome variable because previous research documents that recipients with three or more episodes of pAMR within the first 90 days after transplantation are much more likely to eventually have CAV or other forms of cardiac death.14

Results

Donor and Recipient Characteristics

Donor age information was available for 706 of the 1294 adult recipients in the data set and donor sex information was available for 730. The mean donor age was 29.2 ± 16.9 years. The mean recipient age was 49.9 ± 18.1 years. 136 of the donors were over 40 years old. 692 (55.7%) of the recipients died during the study interval. The average time from donor admission to hospital to transplant was 58.2 hours. Two donors had a history of cancer, 7 had a history of hypertension, 15 had some form of autoimmune disease, 5 were diabetic, 93 smoked, 115 drank moderately or heavily, and 80 had a history of drug abuse. No donors had active infections at the time of transplantation. No information was available about preformed antibodies. Information about immunization responses was also unavailable. All donors included were local, so the ischemic time was under 4 hours for each transplant. Recipients and local donors were matched by height and weight within 25% of each measure.

Effect of Donor Age on Recipient CV Death

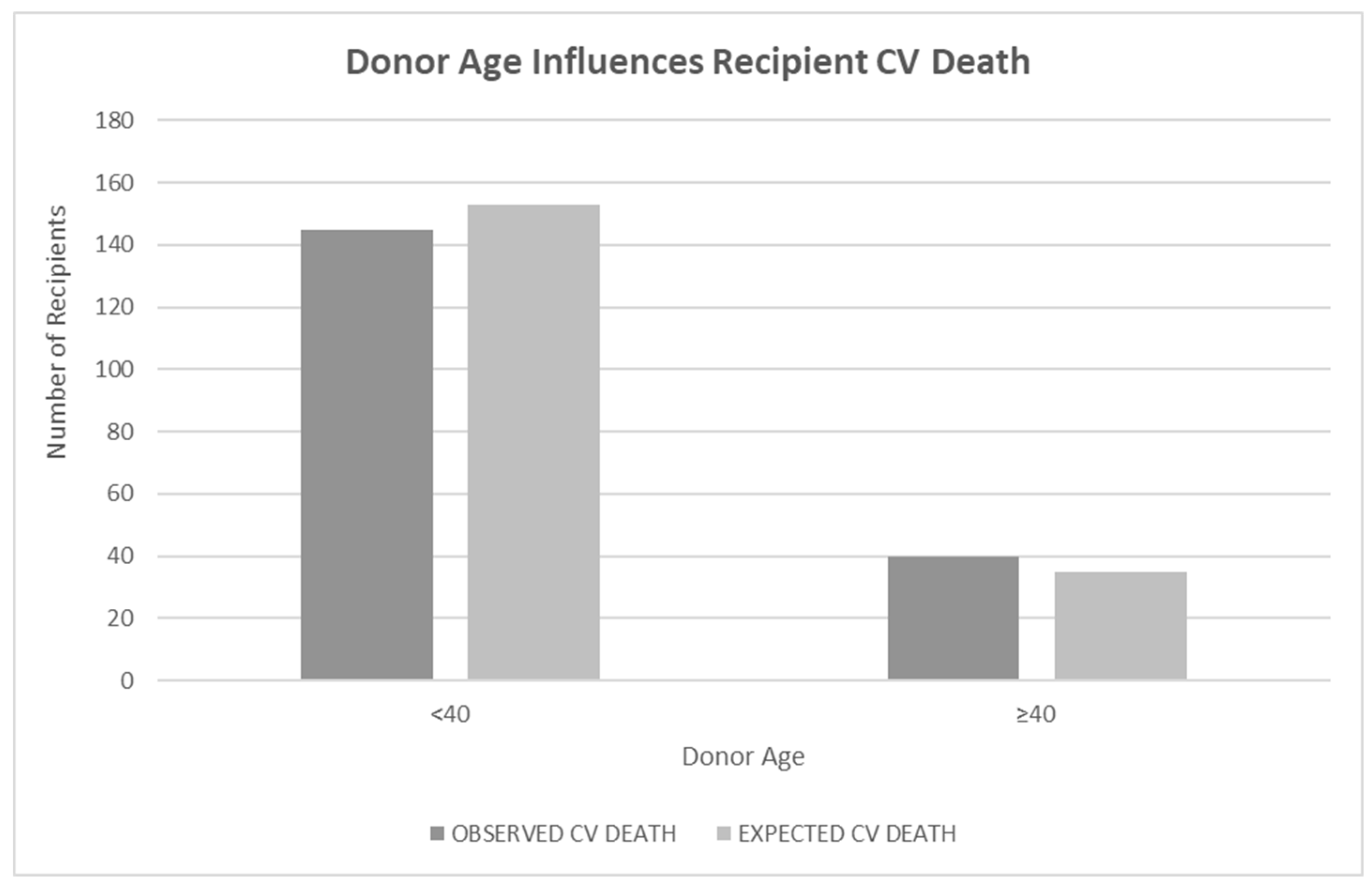

When donor age was investigated as a continuous variable using a Cox proportional hazard regression with CV death of the recipient as the outcome and donor age as the predictor, the result was insignificant (p<0.24). A log rank test of differences using donor age <40 years old and

≥40 years old as a predictor of recipient CV death showed a significant difference in CV death of recipients if the donor was older than 40 years old (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Legend: Bar graph showing the relationship of donor age to recipient cardiovascular (CV) death outcomes. Donor age was parsed as <40 or ≥40 years at the time of transplant. Bars represent the observed CV death rate next to the expected CV death rate. Age ≥40 was statistically significant based on log-rank test of differences (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Legend: Bar graph showing the relationship of donor age to recipient cardiovascular (CV) death outcomes. Donor age was parsed as <40 or ≥40 years at the time of transplant. Bars represent the observed CV death rate next to the expected CV death rate. Age ≥40 was statistically significant based on log-rank test of differences (p<0.05).

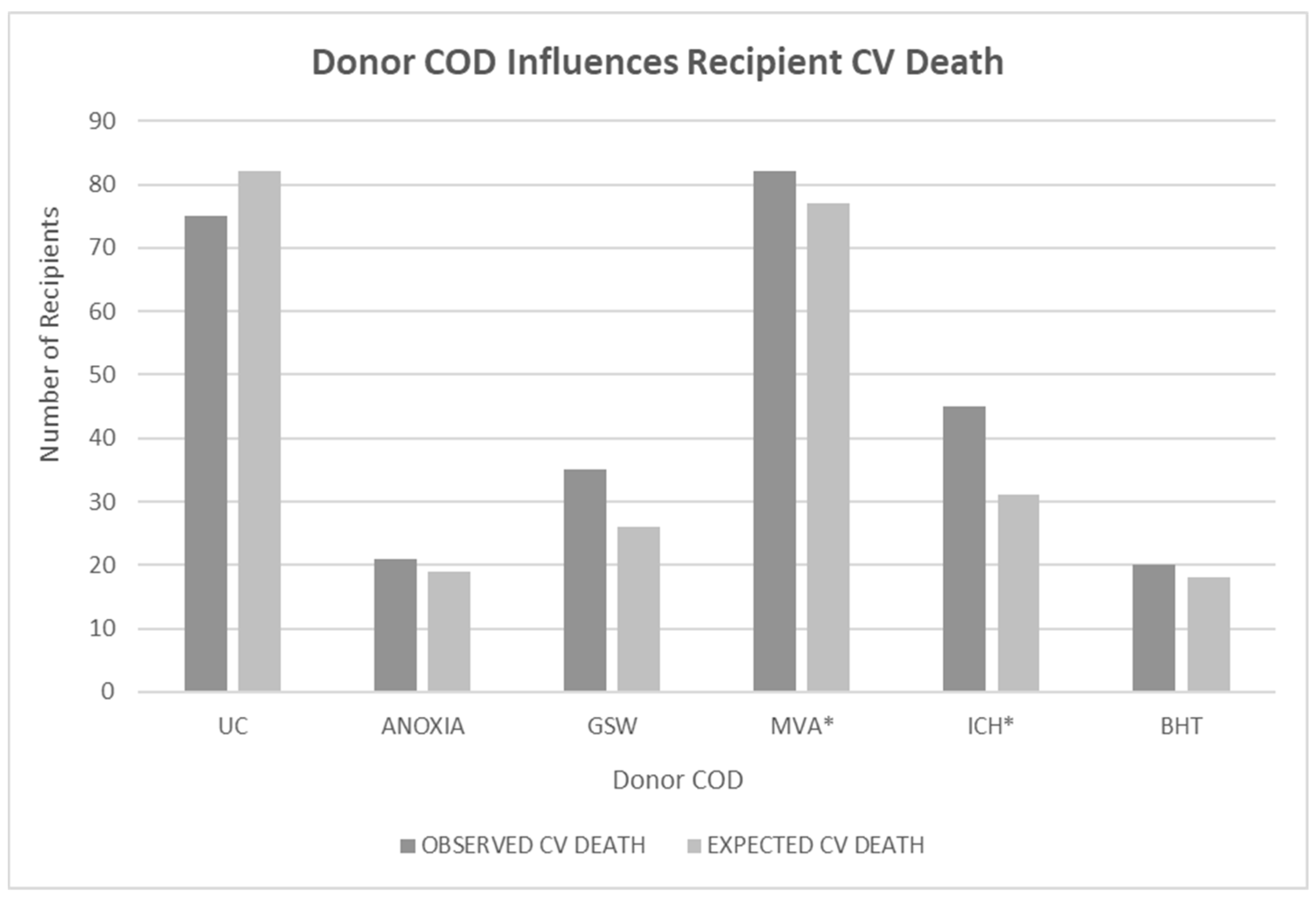

Effect of Donor COD on Recipient CV Death

Recipients with hearts from donors with a COD of ICH or MVA died from CV death more frequently than patients who received a heart from a donor with a COD of GSW or BHT (p<0.052 for MVA vs GSW; p<0.005 for ICH vs GSW). Analysis was done using a log-rank test of differences where COD was the predictor of death and the comparator were patients where the COD was unknown (n=364). A Chi Square test was used for the various COD comparisons. There appeared to be a significant interaction of donor COD and donor age greater than 40. When the analysis was done only on patients whose donors were older than 40 years, the differences were not significant but the number of observations was small for this older subset, p<0.49).

Figure 2.

Legend: Bar graph showing the relationship of donor cause of death (COD) to recipient CV death outcomes. Analysis was done using a log rank test of differences where COD was the predictor of death and patients with unknown COD (UC) were the comparator (n=364). A Chi Square test was used for the various COD comparisons.Star indicated those results which are statistically significant in specific comparisons. Recipients with hearts from donors who died from intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) or motor vehicle accident (MVA) died from CV death more frequently than patients dying of gunshot wounds to the head (GSW) (p<0.052 for MVA vs GSW; p<005 for ICH vs GSW). UC = unknown COD, anoxia = anoxic death, GSW = gunshot wound to the head, MVA = motor vehicle accident, including any vehicle and auto pedestrian accidents, ICH = intracranial hemorrhage, BHT = other causes of blunt head trauma.

Figure 2.

Legend: Bar graph showing the relationship of donor cause of death (COD) to recipient CV death outcomes. Analysis was done using a log rank test of differences where COD was the predictor of death and patients with unknown COD (UC) were the comparator (n=364). A Chi Square test was used for the various COD comparisons.Star indicated those results which are statistically significant in specific comparisons. Recipients with hearts from donors who died from intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) or motor vehicle accident (MVA) died from CV death more frequently than patients dying of gunshot wounds to the head (GSW) (p<0.052 for MVA vs GSW; p<005 for ICH vs GSW). UC = unknown COD, anoxia = anoxic death, GSW = gunshot wound to the head, MVA = motor vehicle accident, including any vehicle and auto pedestrian accidents, ICH = intracranial hemorrhage, BHT = other causes of blunt head trauma.

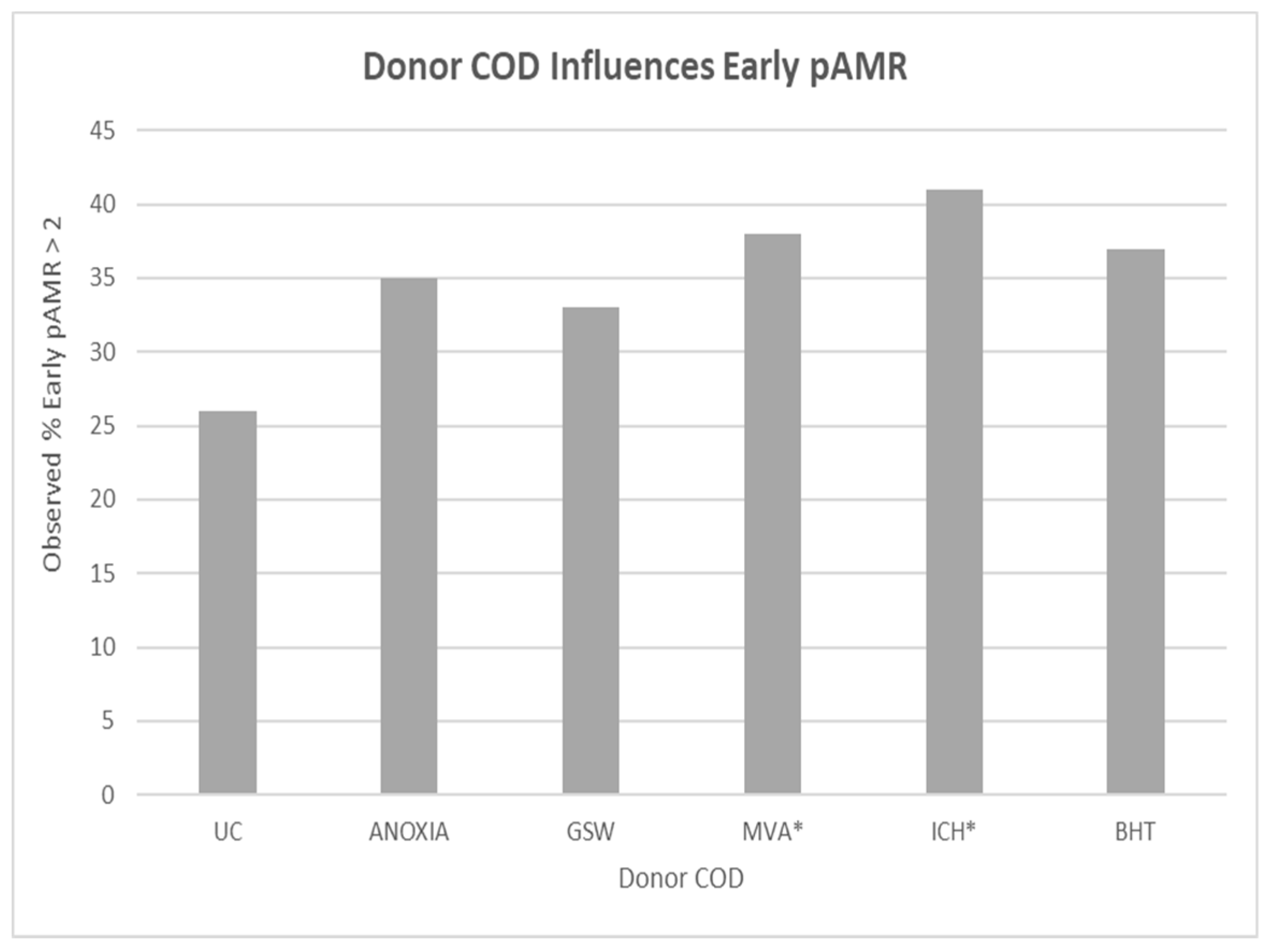

Effect of Donor COD on Recipient Early pAMR

A log rank test indicated that when donors died of MVA or ICH, the recipient was more likely to have early pAMR (p<0.005). Confidence intervals were broad and numbers of observations were limited for this older subset (p<0.49).

Figure 3.

Legend: Bar graph showing the relationship between recipient incidence of early antibody mediated rejection (pAMR, >2 episodes within 90 days after transplant) and donor cause of death (COD). A star highlights the significant COD types. A log rank test indicated that when donors died of MVA or ICH, the recipient was very likely to have early pAMR (p<0.005). UC = unknown COD, anoxia = anoxic death, GSW = gunshot wound to the head, MVA = motor vehicle accident, including any vehicle and auto pedestrian accidents, ICH = intracranial hemorrhage, BHT = other causes of blunt head trauma.

Figure 3.

Legend: Bar graph showing the relationship between recipient incidence of early antibody mediated rejection (pAMR, >2 episodes within 90 days after transplant) and donor cause of death (COD). A star highlights the significant COD types. A log rank test indicated that when donors died of MVA or ICH, the recipient was very likely to have early pAMR (p<0.005). UC = unknown COD, anoxia = anoxic death, GSW = gunshot wound to the head, MVA = motor vehicle accident, including any vehicle and auto pedestrian accidents, ICH = intracranial hemorrhage, BHT = other causes of blunt head trauma.

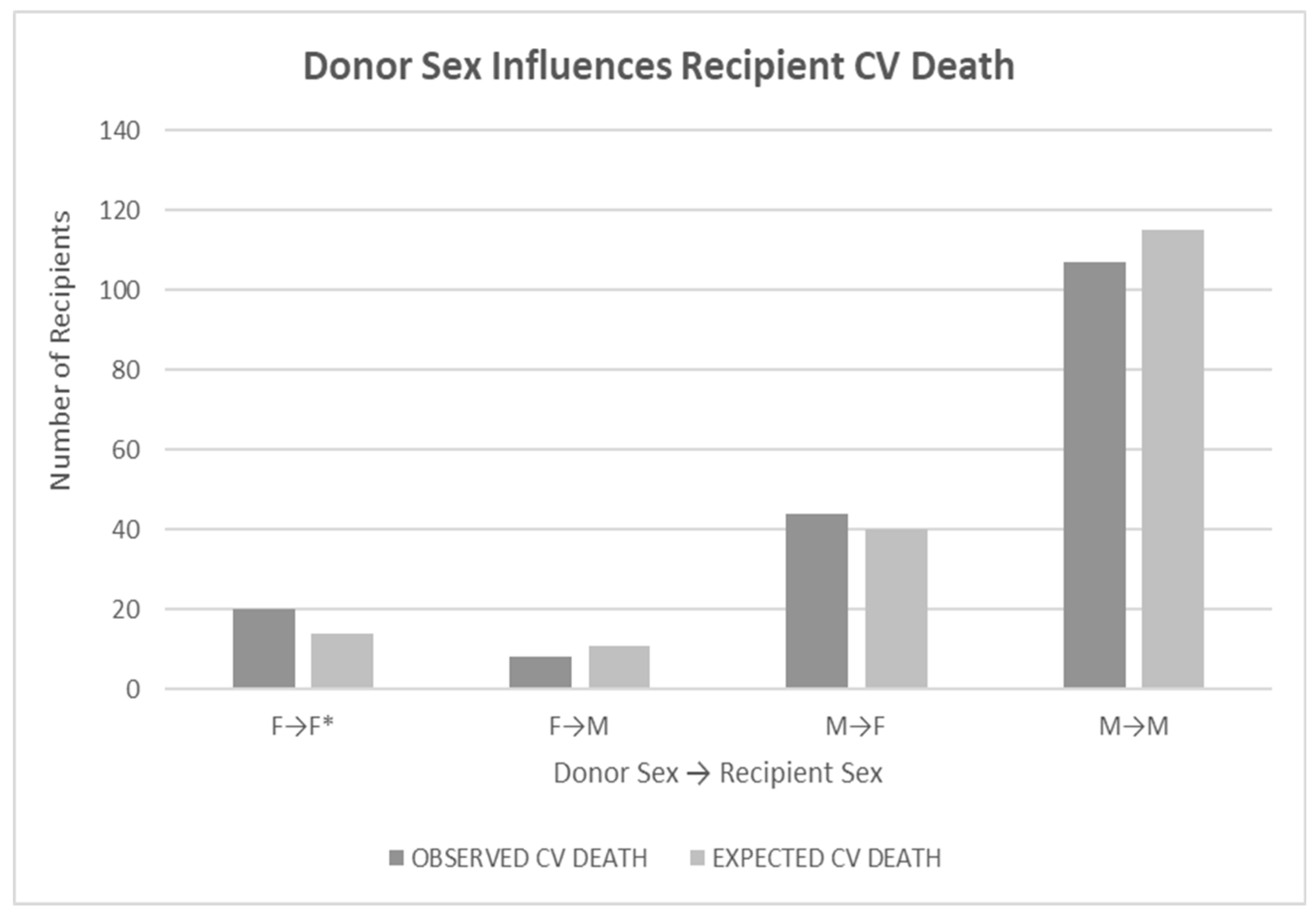

Effect of Donor Sex on Recipient CV Death

Recipients with female donor hearts died more frequently from CV causes (p<0.05), if the recipient was female (p<0.05) but the result was not significant if the recipient was male. Recipient sex was not as influential on CV death (p<0.09). Analysis was done using a log rank test of differences. Evaluation of donor-recipient sex mismatches also showed no significance for any combination (p<0.62).

Figure 4.

Legend: Bar graph showing the relationship of donor sex to recipient CV death outcomes. Recipients with female donor hearts died more frequently from CV causes (p<0.05). Double star highlights the significant comparison.Recipient sex was not as influential (p<0.09). Analysis was done using a log rank test of differences. Evaluation of donor-recipient sex mismatches also showed no significance for any combination (p<0.62).

Figure 4.

Legend: Bar graph showing the relationship of donor sex to recipient CV death outcomes. Recipients with female donor hearts died more frequently from CV causes (p<0.05). Double star highlights the significant comparison.Recipient sex was not as influential (p<0.09). Analysis was done using a log rank test of differences. Evaluation of donor-recipient sex mismatches also showed no significance for any combination (p<0.62).

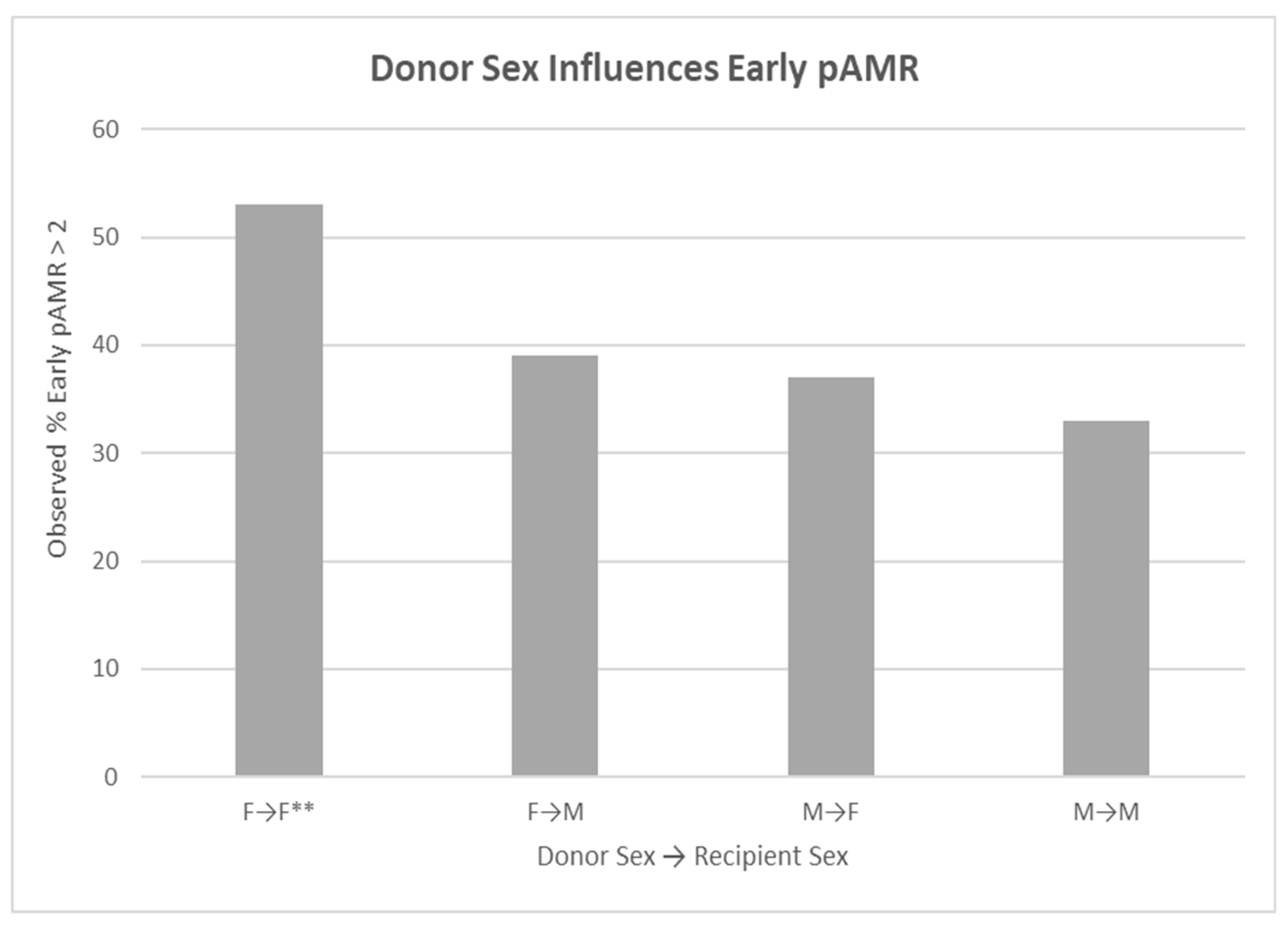

Effect of Donor Sex on Recipient Early pAMR

Recipients of female hearts had a higher incidence of early pAMR if the recipient was female (p<0.049) compared to male heart donors being transplanted into male recipients. Analysis was done using a log rank test of differences.

Figure 5.

Legend: Bar graph of the relationship of donor sex to recipient incidence of early antibody- mediated rejection (pAMR, >2 episodes within 90 days after transplant). Females receiving female hearts had a higher incidence of early pAMR (p<0.049).Double star highlights this relationship.

Figure 5.

Legend: Bar graph of the relationship of donor sex to recipient incidence of early antibody- mediated rejection (pAMR, >2 episodes within 90 days after transplant). Females receiving female hearts had a higher incidence of early pAMR (p<0.049).Double star highlights this relationship.

Discussion

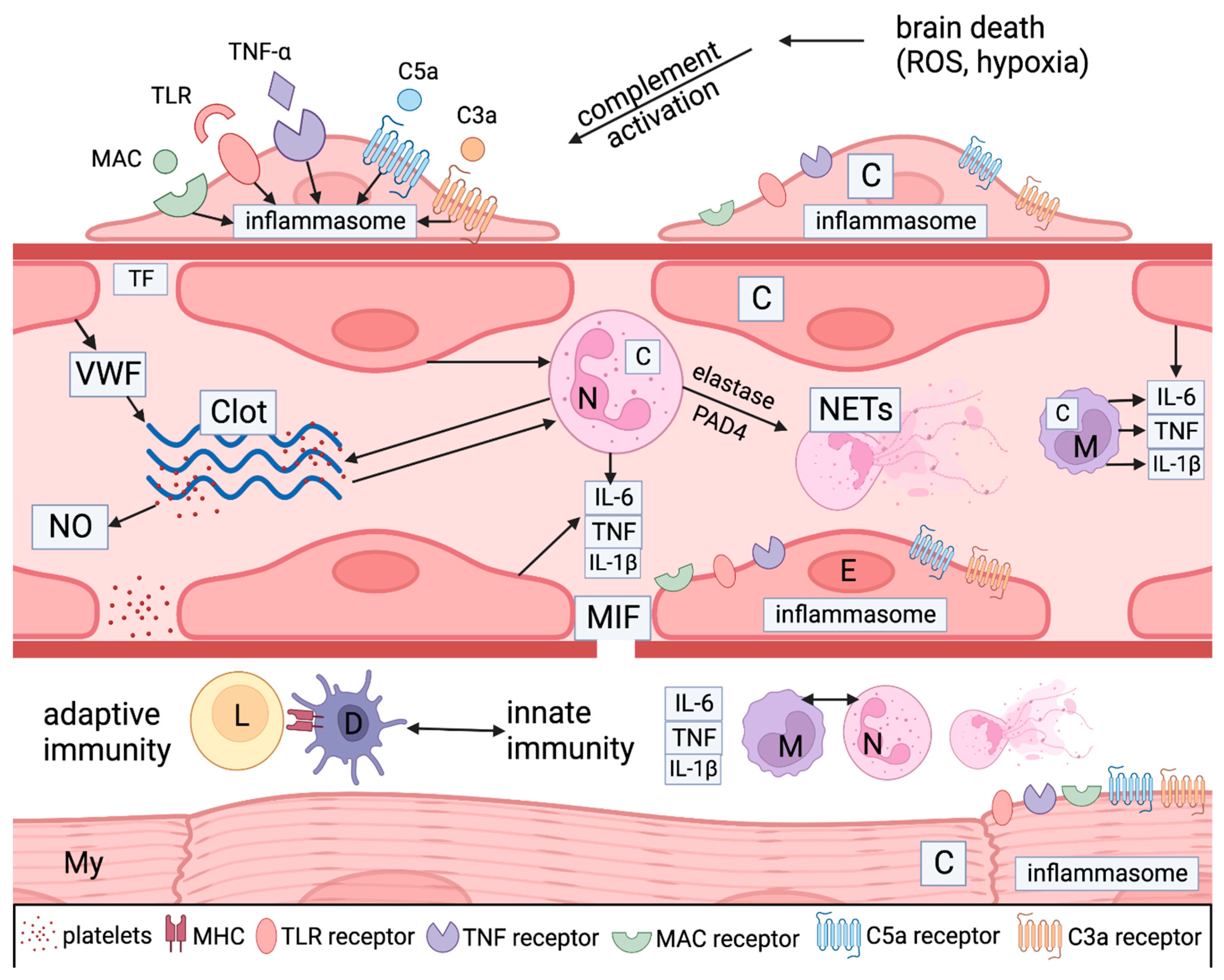

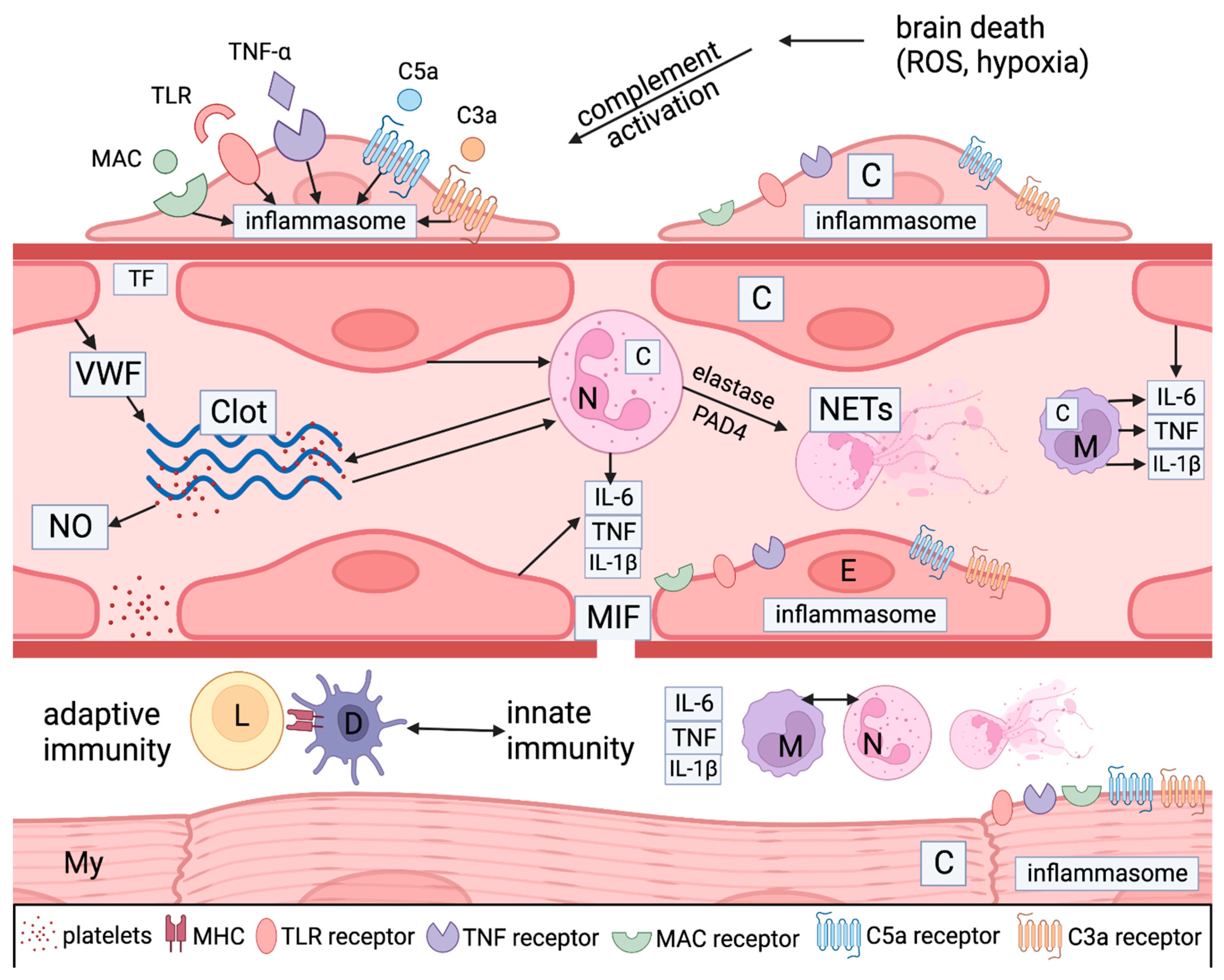

In this limited study, donor CODs with a more intense immune response (such as ICH and MVA) predisposed recipients to CV death and early pAMR if the donors were less than 40 years old, when age was examined as a continuous variable in our analysis.. Similar trends were found in older donors, but the case numbers were low for this subset and the results were not significant.

Donors in MVAs often experience multiple organ trauma and therefore have more tissue injury than donors dying by other means such as GSW, BHT, or anoxia (usually drug overdose). This often widespread tissue injury results in an increased inflammatory response. 2,9,17,18 Multi-system trauma also causes diffuse blood pooling, resulting in extensive hypoxia which is highly inflammatory. While hypoxia occurs to some degree in all forms of brain death, it is greater in donors where wide systemic injury is present.9,17,18 Additionally, recent studies in multiple organ trauma patients have documented the existence of complement effectors including C5a-C9, which peak 6 hours after injury and remain elevated for several days.19,20 Studies on myocardial ischemia and cardiomyopathy show that heart tissue is known to accelerate complement activity as myocytes and pericytes form complement components which then accelerate injury from complement effectors and neutrophils recruited by this reaction.8,21

ICH also has a high inflammatory response. Unlike MVA where the injury is relatively diffuse, ICH results in localized hypoxia and injury, which may suggest a lower inflammatory condition. It has been shown, however, that the process of reperfusion of ischemic tissue after ICH specifically is highly inflammatory, which largely negates this localized advantage. This inflammation and its resulting cytokines activate microglial cells, induce the recruitment of bloodborne immune cells into the area of infarction, and upregulate inflammatory responses in neighboring endothelial cells. This triggers neutrophil accumulation and further activation of the complement and coagulation systems. 22,23

The activation of innate immune mediators in response to cellular stressors, including hypoxia and reperfusion as seen in MVA and ICH has been termed inflammasome triggering

20-23 Components of inflammasome triggering include danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), complement components, reactive oxygen species (ROS), signaling molecules such as NF-kB, pattern recognition receptors (PRR) such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF, chemokine receptors, adhesion molecules, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells.

20-23 Many of these factors, notably NF-kB pathways, are also implicated in the pathogenesis of CAV.

3-10

Figure 6.

Legend: Simplified graphical illustration of the mechanisms of injury in donors after brain death. Ischemic stress and cell death lead to complement activation through the classical, alternative, and lectin pathways. DAMPS like TLR ligand, TNF a and complement components like C3a, C5a, and C5b-9 (MAC) bind with PRR receptors on pericytes (P), endothelial cells (E), neutrophils (N) and macrophages (M) to induce inflammasome assembly and release of pro-inflammatory mediators like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa), interleukin 6 (IL-6 ), and interleukin 1 beta (IL-1b). Microvascular endothelial cells, pericytes, myocytes (My), and inflammatory cells make more complement proteins (C) and inflammatory cytokines as well as macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF) which leads to gaps in the basement membrane promoting vascular permeability and extravasation of neutrophils and macrophages and activating dendritic cells (D). Neutrophil activation and neutrophil extracellular trap (NETS) generation (through the action of elastase and PAD4) also play a pivotal role. They stimulate coagulation and complement activation, creating positive feedback loops between endothelial cells and platelets. Platelets generate nitrous oxide (NO), another potent mediator. Endothelial cells elaborate von Willebrand factor (VWF), which is an important accelerator of coagulation. Cell necrosis caused by the autoinflammatory process exposes cellular HLA antigens that initiate allorecognition by involving donor macrophages and dendritic cells (D) as well as potential autoimmunity against myocyte and endothelial antigens. Myocyte injury can be initiated by ischemia generated by the vascular injury and by adaptive and autoimmunity against myocyte donor-specific antigens (MHC) and others.

Figure 6.

Legend: Simplified graphical illustration of the mechanisms of injury in donors after brain death. Ischemic stress and cell death lead to complement activation through the classical, alternative, and lectin pathways. DAMPS like TLR ligand, TNF a and complement components like C3a, C5a, and C5b-9 (MAC) bind with PRR receptors on pericytes (P), endothelial cells (E), neutrophils (N) and macrophages (M) to induce inflammasome assembly and release of pro-inflammatory mediators like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa), interleukin 6 (IL-6 ), and interleukin 1 beta (IL-1b). Microvascular endothelial cells, pericytes, myocytes (My), and inflammatory cells make more complement proteins (C) and inflammatory cytokines as well as macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF) which leads to gaps in the basement membrane promoting vascular permeability and extravasation of neutrophils and macrophages and activating dendritic cells (D). Neutrophil activation and neutrophil extracellular trap (NETS) generation (through the action of elastase and PAD4) also play a pivotal role. They stimulate coagulation and complement activation, creating positive feedback loops between endothelial cells and platelets. Platelets generate nitrous oxide (NO), another potent mediator. Endothelial cells elaborate von Willebrand factor (VWF), which is an important accelerator of coagulation. Cell necrosis caused by the autoinflammatory process exposes cellular HLA antigens that initiate allorecognition by involving donor macrophages and dendritic cells (D) as well as potential autoimmunity against myocyte and endothelial antigens. Myocyte injury can be initiated by ischemia generated by the vascular injury and by adaptive and autoimmunity against myocyte donor-specific antigens (MHC) and others.

Discussion, Continued

Regarding complement, recent studies highlight that complement activation occurs within 6 hours of major trauma and includes triggering of classical, lectin, and alternative pathways of complement activation associated with neutrophil and platelet accumulation as well as coagulation system activation.20-23 Complement receptors sense complement effector molecules (e.g., C3a, C5a, C3b, iC3b, C3d) generated by DAMP-mediated activation of complement. Once activated, stress-induced signaling through receptors on endothelial cells, myocytes, and infiltrating leukocytes mediate continuous tissue injury. Complement receptors on antigen-presenting cells and T cells promote donor specific allorecognition.24 Effector responses against donor antigens are also enabled by complement and toll-like receptors (TLR), which accelerate the adaptive immune response. Complement effector molecules recruit more neutrophils which generate further complement and coagulation responses.3-10,17-20 Such responses are typically ongoing and unopposed without treatment until the time of transplantation.

Antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) is generated through the same mechanism of microvascular endothelial cell complement activation described above in MVA and ICH (often by donor-specific antibody binding), with accumulation of neutrophils, macrophages, and fibrin, in addition to further activation of complement and coagulation cascades. These features are most prominent early after transplantation when these additive donor initiated effects may be most prominent.15,24 Thus, this study is important in highlighting the potential role of innate immune activation in triggering AMR. Importantly, AMR is strongly associated with worse recipient outcomes, specifically CV death or retransplantation due to CAV.The association of AMR and worse CV outcomes has been described in the literature consistently since 2011.15,23,24.

Female donor hearts are more frequently associated with worse recipient outcomes in both this study and other published reports15,23 We have previously reported that female recipients are more likely to die after transplant from AMR or CV death.15 Females have a higher immune response based on both genetic and hormonal influences.25,26 Numerous cell types bear estrogen receptors on their plasma membranes, including endothelial cells, neuronal cells, hematopoietic stem cells, and mature immune cells.26,27 Estradiol can bind to these cell types and trigger hormone-responsive genes and cytokine release, which directly affects the strength of both the innate and adaptive immune responses. Estradiol promotes the production of interferon alpha, regulates the function of innate immune cells (especially B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages), and alters dendritic and macrophage maturation and activation. In addition, estradiol activates the coagulation system.28-30 Therefore, female donors are expected to have a stronger immune response and trigger a correspondingly strong immunological response in recipients. By contrast, the actions of testosterone are largely anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive.30

A recent study of donor and recipient age found that advancing donor age was associated with higher recipient mortality, particularly in the short term.31 We found a significant association of CV death with donors of either sex who were 40 years old or older. Emerging evidence suggests that during aging, chronic sterile low-grade inflammation (so-called inflammaging) develops and contributes to the pathogenesis of age-related diseases including atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer. Thus, the interaction we see between MVA/ICH and increased CV death may be related to the enhanced inflammasome activation triggered by hypoxia and resultant ROS activation through inflammaging in older recipients.32-33

Limitations

This was a single-center study, which limits statistical power. All donors and recipients were from the same region. Many donor records had missing information, which limited the number of patients that could be included in the analyses. Although we carefully reviewed each donor record, some information that may have influenced the donor outcomes was unavailable. Finally, our population size was too small to identify all potential interactions and evaluate them with sufficient statistical power.

Conclusions

In this single institution study with long recipient follow-up of up to 30 years, we found that recipients with hearts from donors who died with a COD of MVA or ICH had a higher frequency of CV related deaths and early pAMR. Age of donors over 40 and female donors were also related to higher pAMR and CV death in recipients. Age, female sex, and COD of MVA or ICH in the donor have been reported to promote IR triggering and inflammasome activation as well as complement activation and effector activity, which are likely important drivers of CAV and CV death. Increased understanding of inflammasome activation and pathways is emerging along with potential therapeutic strategies. We recognize that the cardiac transplant donor pool is limited. Our findings suggest that modified donor protocols to monitor markers of innate immune triggering like complement components and IL-6 in patients who are either female donors or those whose COD was MVA or ICH may predict which patients would benefit from emerging therapeutic strategies. Allorecognition by donor cells is an important accelerator of adaptive immunity as well. This donor function has recently been highlighted in a heterologous mouse transplant model where donor derived macrophages provide most allorecognition..34

More extensive donor evaluation and monitoring may suggest potential therapeutic interventions to improve recipient cardiac transplant outcomes.

Funding

The study was funded by the A Lee Christensen Fund of the Intermountain Medical and Research Foundation, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Data Availability Statement

Data that was analyzed for this manuscript is housed in an IRB approved REDCAP database at Intermountain Healthcare. Review of these files can be requested of Gregory Snow PhD at greg.snow@imail.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Transplant surgeons, transplant nurses, data manaagers, and staff of the Intermountain Donor Services for their help with this study.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Kittleson MM, Kobashigawa JA. Cardiac Transplantation: Current Outcomes and Contemporary Controversies. JACC Heart Fail. 2017 Dec;5(12):857-868.

- Hsich EM, Blackstone EH, Thuita LW, McNamara DM, Rogers JG, Yancy CW, Goldberg LR, Valapour M, Xu G, Ishwaran H. Heart Transplantation: An In-Depth Survival Analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2020 Jul;8(7):557-568.

- Pober JS, Chih S, Kobashigawa J, Madsen JC, Tellides G. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: current review and future research directions. Cardiovasc Res. 2021 Nov 22;117(13):2624-2638.4. Land WG, Agostinis P, Gasser S, Garg AD, Linkermann A. Transplantation and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Am J Transplant 2016; 16:3338-61. [CrossRef]

- Danese, S.; Dejana, E.; Fiocchi, C. Immune Regulation by Microvascular Endothelial Cells: Directing Innate and Adaptive Immunity, Coagulation, and Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 6017–6022, . [CrossRef]

- Pober JS, Jane-wit D, Qin L, Tellides G. Interacting mechanisms in the pathogenesis of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014; 34(8):1609-14. [CrossRef]

- Millington, T.M.; Madsen, J.C. Innate immunity and cardiac allograft rejection. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, S18–S21, . [CrossRef]

- Silvis, M.J.M.; Dengler, S.E.K.G.; Odille, C.A.; Mishra, M.; van der Kaaij, N.P.; Doevendans, P.A.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; de Kleijn, D.P.V.; de Jager, S.C.A.; Bosch, L.; et al. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Myocardial Infarction and Heart Transplantation: The Road to Translational Success. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, . [CrossRef]

- Barac, Y.D.; Jawitz, O.K.; Klapper, J.; Schroder, J.; Daneshmand, M.A.; Patel, C.; Hartwig, M.G.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Milano, C.A. Heart Transplantation Survival and the Use of Traumatically Brain-Injured Donors: UNOS Registry Propensity-Matched Analysis. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e012894, . [CrossRef]

- van den Hoogen P, Huibers MM, Sluijter JP, de Weger RA. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a donor or recipient induced pathology? J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2015 Mar;8(2):106-16. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Sheng, X.; Drakos, S.; Stehlik, J. Impact of Donor Cause of Death on Transplant Outcomes: UNOS Registry Analysis. Transplant. Proc. 2009, 41, 3539–3544, . [CrossRef]

- Nagji, A.S.; Hranjec, T.; Swenson, B.R.; Kern, J.A.; Bergin, J.D.; Jones, D.R.; Kron, I.L.; Lau, C.L.; Ailawadi, G. Donor Age Is Associated With Chronic Allograft Vasculopathy After Adult Heart Transplantation: Implications for Donor Allocation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 90, 168–175, . [CrossRef]

- Trivedi JR(1), Cheng A, Ising M, Lenneman A, Birks E, Slaughter MS. Heart Transplant Survival Based on Recipient and Donor Risk Scoring: A UNOS Database Analysis. ASAIO J 2016; 62(3):297-301. [CrossRef]

- Kfoury, A.G.; Stehlik, J.; Renlund, D.G.; Snow, G.; Seaman, J.T.; Gilbert, E.M.; Stringham, J.S.; Long, J.W.; Hammond, M.E.H. Impact of Repetitive Episodes of Antibody-mediated or Cellular Rejection on Cardiovascular Mortality in Cardiac Transplant Recipients: Defining Rejection Patterns. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2006, 25, 1277–1282, . [CrossRef]

- Hammond, M.E.H.; Revelo, M.P.; Miller, D.V.; Snow, G.L.; Budge, D.; Stehlik, J.; Molina, K.M.; Selzman, C.H.; Drakos, S.G.; A., A.R.; et al. ISHLT pathology antibody mediated rejection score correlates with increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: A retrospective validation analysis. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2016, 35, 320–325, . [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2023). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on June 2023).

- Farrar, C.A.; Kupiec-Weglinski, J.W.; Sacks, S.H. The Innate Immune System and Transplantation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a015479–a015479, . [CrossRef]

- Janakiram, N.B.; Valerio, M.S.; Goldman, S.M.; Dearth, C.L. The Role of the Inflammatory Response in Mediating Functional Recovery Following Composite Tissue Injuries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13552, . [CrossRef]

- Huber-Lang, M.; Lambris, J.D.; Ward, P.A. Innate immune responses to trauma. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 327–341, . [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C.; Buckwalter, M.S.; Anrather, J. Immune responses to stroke: mechanisms, modulation, and therapeutic potential. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2777–2788, doi:10.1172/jci135530.

- Chamorro, A, Meisel A, Planas AM, Urra X, van de Beek D, Veltkamp R; The immunology of acute stroke. Nat Rev Neurol 2012; 8 401-410. [CrossRef]

- Schanze, N.; Bode, C.; Duerschmied, D. Platelet Contributions to Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1260, . [CrossRef]

- Hammond MEH, Kfoury AG. Antibody-mediated rejection in the cardiac allograft: diagnosis, treatment and future considerations. Curr Opin Cardio 2017; 32, 326-335. [CrossRef]

- Halloran, P.F.; Madill-Thomsen, K.S. The Molecular Microscope Diagnostic System: Assessment of Rejection and Injury in Heart Transplant Biopsies. Transplantation 2023, 107, 27–44, . [CrossRef]

- Grupper, A.; Nestorovic, E.M.; Daly, R.C.; Milic, N.M.; Joyce, L.D.; Stulak, J.M.; Joyce, D.L.; Edwards, B.S.; Pereira, N.L.; Kushwaha, S.S. Sex Related Differences in the Risk of Antibody-Mediated Rejection and Subsequent Allograft Vasculopathy Post-Heart Transplantation: A Single-Center Experience. Transplant. Direct 2016, 2, e106–e106, . [CrossRef]

- Kovats, S. Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways. Cell. Immunol. 2015, 294, 63–69, . [CrossRef]

- uruvija I, Stanojević S, Arsenović-Ranin N, Blagojević V, Dimitrijević M, Vidić-Danković B, Vujić V. Sex Differences in Macrophage Functions in Middle-Aged Rats: Relevance of Estradiol Level and Macrophage Estrogen Receptor Expression Inflammation. 2017;40(3):1087-1101. [CrossRef]

- Laffont, S.; Seillet, C.; Guéry, J.-C. Estrogen Receptor-Dependent Regulation of Dendritic Cell Development and Function. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 108, . [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.K.; Yoon, B.-K. Controversies regarding hormone therapy: Insights from inflammation and hemostasis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 70, 22–30, . [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Hejblum, B.P.; Simon, N.; Jojic, V.; Dekker, C.L.; Thiébaut, R.; Tibshirani, R.J.; Davis, M.M. Systems analysis of sex differences reveals an immunosuppressive role for testosterone in the response to influenza vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 869–874, . [CrossRef]

- Bergenfeldt, H.; Lund, L.H.; Stehlik, J.; Andersson, B.; Höglund, P.; Nilsson, J. Time-dependent prognostic effects of recipient and donor age in adult heart transplantation. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2018, 38, 174–183, . [CrossRef]

- Pence, B.D.; Yarbro, J.R. Classical monocytes maintain ex vivo glycolytic metabolism and early but not later inflammatory responses in older adults. Immun. Ageing 2019, 16, 1–8, . [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: a new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 576–590, . [CrossRef]

- Kopecky, B.J.; Dun, H.; Amrute, J.M.; Lin, C.-Y.; Bredemeyer, A.L.; Terada, Y.; Bayguinov, P.O.; Koenig, A.L.; Frye, C.C.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.; et al. Donor Macrophages Modulate Rejection After Heart Transplantation. Circ. 2022, 146, 623–638, . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).