Introduction

“Is that my idea or yours?” From playgrounds to boardrooms, the ability to form an accurate self-vs-other representation enables individuals to navigate social interactions by understanding their own thoughts, feelings, and intentions as distinct from others (Ruby & Decety, 2004). It affects the capacity to embrace others’ perspectives and feelings in a non-centered manner and use this information to bind constructive social interactions (Lang & Reschke, 2006). Indeed, our ability to discriminate self from others helps us navigate complex social environments using adequately social cues (Young, 2008) to effectively form and maintain positive relationships (i.e., friendships, romantic partnerships, and professional networks) (Frith, 2008). Impaired discriminative skills across development impact social cognition, from recognizing oneself in the mirror to interpreting the intentions and emotions of others (Berlim De Mello et al., 2023). Given the importance of well-developed self-vs-others discriminative skills, it seems important to unveil underlying brain activations across development, to gain an understanding of needs and capacities at different stages of life. While different studies shed light on either behavioral or neuroimaging makers of this discriminative ability at different ages or by contrasting adults with young children, none report a cross-sectional perspective on the neural activity across development.

The development of self versus other representations is a complex process, influenced by different factors, including genetics, brain maturation, and environmental experiences (Bahrick, 2008; Falk et al., 2020). During the first year of life already, the ability to distinguish the self from the environment and from others starts emerging, at the physical level (Butterworth, 1992). In fact, babies develop their sensorimotor ability while experiencing different perceptual and sensorimotor events, such as self-produced sounds or touching their own faces and bodies. These events contribute to uniquely specifying and separating their own body as differentiated entities from the environment (Rochat, 1998). Then, discriminative abilities become more abstract. Infants, as young as 20-24 months old, have been shown to display self-recognition in mirror tasks (i.e., touch their own forehead and not their reflection). More interestingly, this ability comes along with the ability to discriminate their own reflection as distinct from other objects or people (Amsterdam, 1972; Platek et al., 2004). As they develop, their brain elaborates increasing preciseness and stability in behavior (Lippé et al., 2009; Posner et al., 2007), while sophisticating their self-concepts, incorporating beliefs and attitudes about their own abilities, personality traits, and social identities (Northoff et al., 2006). At the same time, their understanding of others gives them the ability to recognize others as intentional agents and to take another person's perspective and empathize with them (Decety & Jackson, 2004).

While little is known about the school years’ age, more studies have shown that adolescence is a particularly important period for the development of self-vs-others’ representations, with significant changes in social and emotional abilities, reflected in new relationships and social roles. In fact, adolescents' brains undergo significant changes during this period, notably in regions involved in social cognition and emotion regulation (i.e., the posterior superior temporal sulcus and the medial prefrontal cortex) (Blakemore, 2008). The development of self-vs-other representations continues to evolve throughout adulthood. The cognitive and emotional processes may change as people age, affecting their ability to understand and adapt to social interactions (Lang & Reschke, 2006).

While there is a gradual gain in social cognitive processing, a deeper understanding of self-vs-others discrimination across the development could shed light on differences in social needs and improve the social dimension of learning environments (e.g., when is peer learning a good strategy?). Indeed, the quality of early social experiences is critical and predictive of the development of self and other representations (Beebe & Lachmann, 2003; Brumariu, 2015). Providing adequate social feedback may help shape emotion recognition and regulation as they develop social skills such as empathy and perspective-taking (Brumariu, 2015).

This study aimed at exploring age-related brain activity differences in the processing of self-vs-others. Overall, we hypothesized increased brain activity associated with self-perception across development in brain regions that have been associated with self-recognition in adults. These regions are located in the frontal, parietal, and occipital areas (Devue & Brédart, 2011), as well as the ACC, and the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) (Araujo et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2016c; Murray et al., 2012; Qin & Northoff, 2011). Conversely, we expected increased brain activity when observing someone else in the precuneus, and the angular gyrus, as these regions are activated when looking at others more than oneself (Asakage & Nakano, 2022; Farrer & Frith, 2002). Finally, we also expected higher activity for other than self within the temporal cortex and brain regions involved in the recognition of visual stimuli, previously associated with early identification of humans and human movement (Jastorff & Orban, 2009).

While an overall linear increase in activity is expected across development, non-linear changes are more likely to happen in middle age children (7-10 y.o.) as well as in teenagers (11-19 y.o.). In fact, previous research has shown that brain maturation and connectivity development have both linear and non-linear trajectories. Social cognitive processing is known to follow a non-linear developmental trajectory across the middle age children (Faghiri et al., 2019). In addition, the teenage years are known to be a time window for self-related information (Pfeifer & Berkman, 2018), so we predicted a shift in the pattern of activation for the representation of others.

Method

Participants

In total, 42 healthy participants were recruited for the experiment. Three participants were excluded due to poor MR image quality given by excessive movement, leaving a sample of 39 participants for the final analyses (mean age = 13.54, SD = 8.00). The inclusion criteria were to be healthy and be in the compatible age range studied. The participants were separated into 4 different groups, according to their age: (a) from 4.1 to 6.5 years old, (b) from 7 to 10.5 years old, (c) from 11 to 19 years old, and (d) from 20 years old for the adults (see

Table 1). The study was approved by the ethics committee and written and oral informed consent for the course of the experiment was obtained from the participants or their parents (<14 y.o.).

fMRI video task

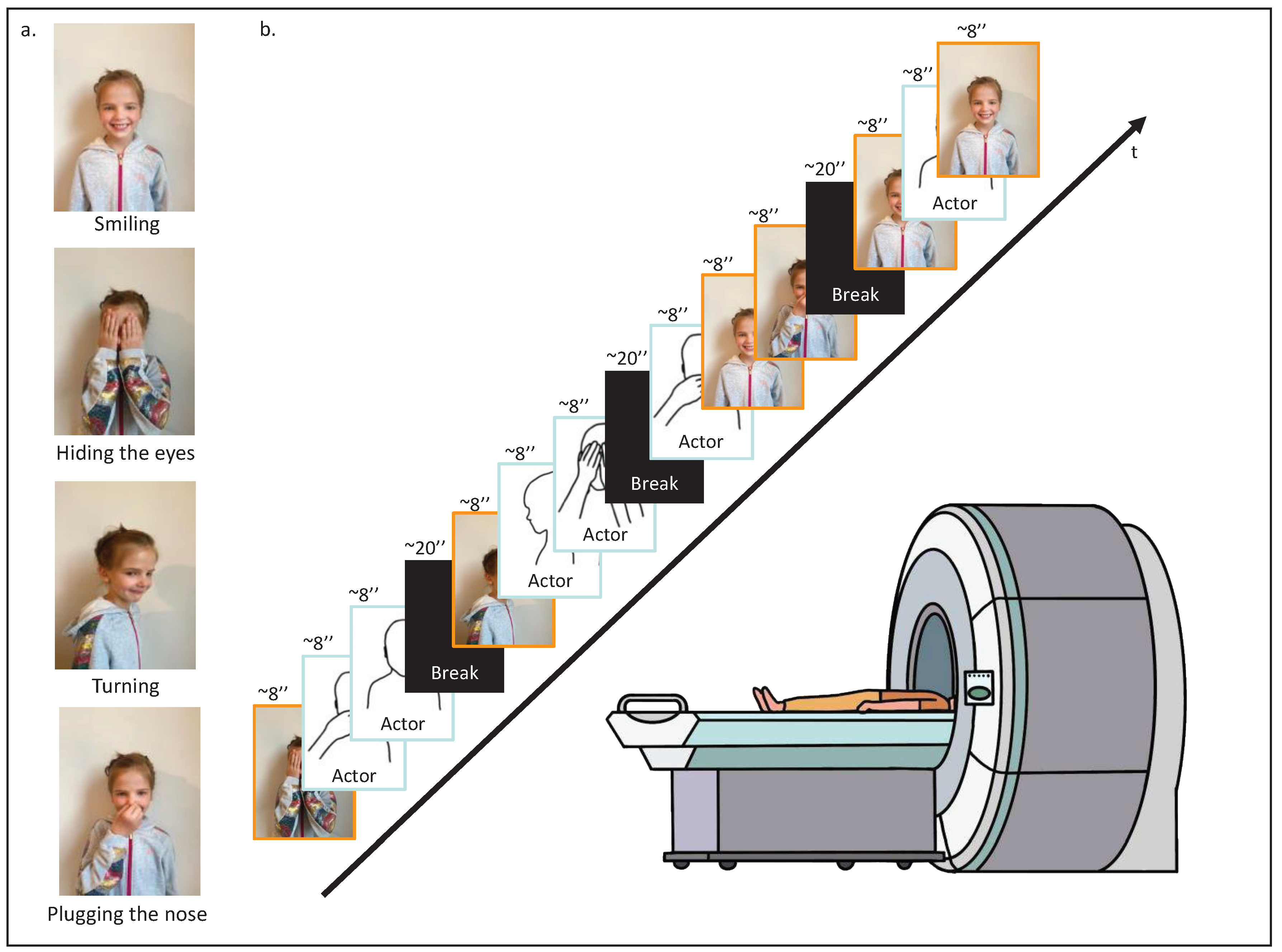

Each participant was initially asked to execute four different movements in front of a camera: hiding their eyes with their hands, turning on themselves, smiling, and plugging their nose (

Figure 1a) for ~7-second recordings. These personalized stimuli were then introduced in the fMRI video task, randomly intertwined with similar stimuli from a same-age and same-gender unknown actor. The final fMRI video task was composed of 12 video clips of the four different movements; half performed by the participant, and half performed by the unknown actor. The video clips of the different movements were presented in random order, with at least one presentation of each, and four were randomly presented twice. The 12 video clips of ~7 seconds were separated into 4 parts of 3 video clips with breaks of 20 seconds in between. In total, the video lasted 160 seconds (

Figure 1b).

Procedure

Participants were placed in the scanner and asked to simply watch the fMRI video task.

MRI data acquisition

Anatomical and functional images were collected using a Siemens (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany, VE11E Software version) 3T Prisma-Fit MR scanner with a 64-channel head coil at the Lausanne University Hospital. MRI sessions were conducted with two different acquisitions for each subject: (i) 3-dimensional T1 weighted MP-RAGE (Magnetization Prepared - RApid Gradient Echo) (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 2.47 ms, 208 slices; voxel size=1×1×1 mm3, flip angle=8°), used as an anatomical reference for brain extraction and surface reconstruction, and (ii) a functional MRI (fMRI) acquired continuously using a standard echo-planar gradient echo sequence, with simultaneous multislice (SMS) imaging technique. This technique allows to cover the whole brain with an isotropic voxel size of 2 mm ([TR] = 1000 ms; echo time [TE] = 30 ms; 64 axial slices; slice thickness = 2 mm, no gap between slices, flip angle = 80°, matrix size = 100 × 100, a field of view [FOV] = 200 mm, SMS factor = 4, parallel imaging acceleration factor = 2). The total fMRI acquisition time was 3 min and 12 seconds.

To prevent head movement and noise, foam pads were placed around the participants' heads inside the coil.

MRI data processing

MRI data were preprocessed using SPM12 software (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK), run on Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA Version 7.13). To correct the motion of the functional images, the first scan was used as a reference, using a 6-parameter rigid-body realignment. The realigned images were then slice-timing corrected, and both the functional images and the high-resolution T1-weighted (T1w) anatomical image of the participant were co-registered, using mutual information. Using the anatomical images as an estimation basis, functional images were normalized to the MNI template and spatially smoothed using an 8-mm Gaussian filter.

Data visualization and figure preparation were done using the xjView Toolbox for SPM (

http://www. Alivelearn.net/xjview). An aal atlas was used to label and describe anatomical locations (Rolls et al., 2020).

Neural activation analyses

In statistical single-subject analysis, performed by applying a general linear model, neural activities while watching self-vs-other perception stimuli were retrieved; onsets were video clips’ starting times, and durations were the 7 seconds of the video clips. The realignment parameters were included in the model as a nuisance variable. A frequency threshold of 121 Hz was used as a high pass filter cutoff to filter the amplitude of signals, allowing the removal of the low-frequency noise or interference. A visual inspection of estimated motion parameters was conducted for each participant. Several recording images of 4 participants were excluded according to the artifact repair procedure performed with ArtRepair (Mazaika et al., 2009). Statistical inference from the acquired group was performed using the first-level contrasts of interest as input values. First, a mixed model ANOVA was performed with, as intra-subject variables, the contrasts representing brain activity during perception of self and other (2 levels) at the whole-brain level across age groups as inter-subject variables (four levels). A threshold of p<0.05 (FDR corrected) was used for the selection of the significant clusters. In order to investigate and reveal the effect of self-vs-other perception between the different age groups, we performed a post-hoc comparison using paired t-tests on BOLD signal changes extracted from significant clusters. The paired t-tests were conducted to compare the activation of the brain region during self-vs-other perception, between age groups.

Results

Neural activation analyses

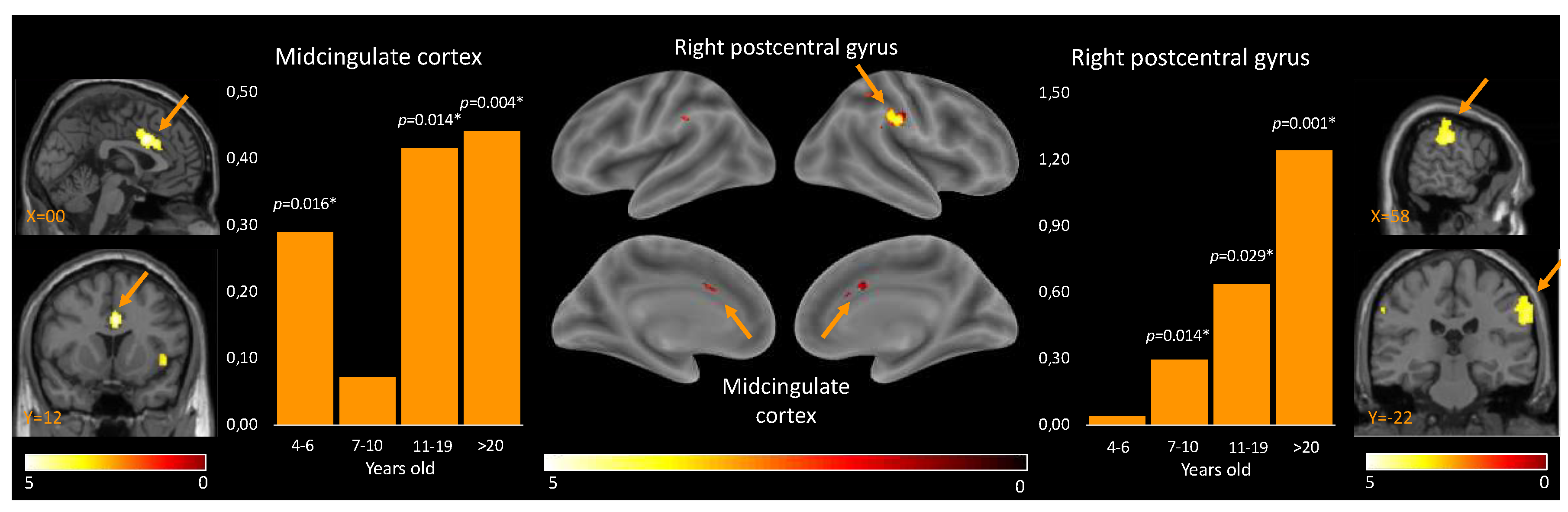

First, the positive effect of condition (self-vs-other) revealed regions that show significant increases in their involvement in the processing of self-vs-other stimuli independently from the age group. These regions included the midcingulate cortex (MCC) and the right postcentral gyrus. The opposite contrast (other-vs-self) revealed regions that show significant increases in their involvement in the processing of other-vs-self stimuli independently from the age group. These regions included the right angular gyrus, left angular gyrus, right inferior temporal gyrus, left middle temporal gyrus, right rectus, right precuneus, right medial prefrontal cortex, right superior frontal gyrus, and left inferior orbital gyrus (see details in

Table 2).

Second, the post-hoc paired t-test analyses revealed between which age groups the activation for self-perceptions, compared to the perception of others, were statistically different. For the MCC, discrimination of self-vs-other perception was true for all age groups, while not for the 7-10 y.o. group. For the right postcentral gyrus, self-vs-other perception differed for all age groups, while not for the 4-6.5 y.o. group (

Table 3,

Figure 2).

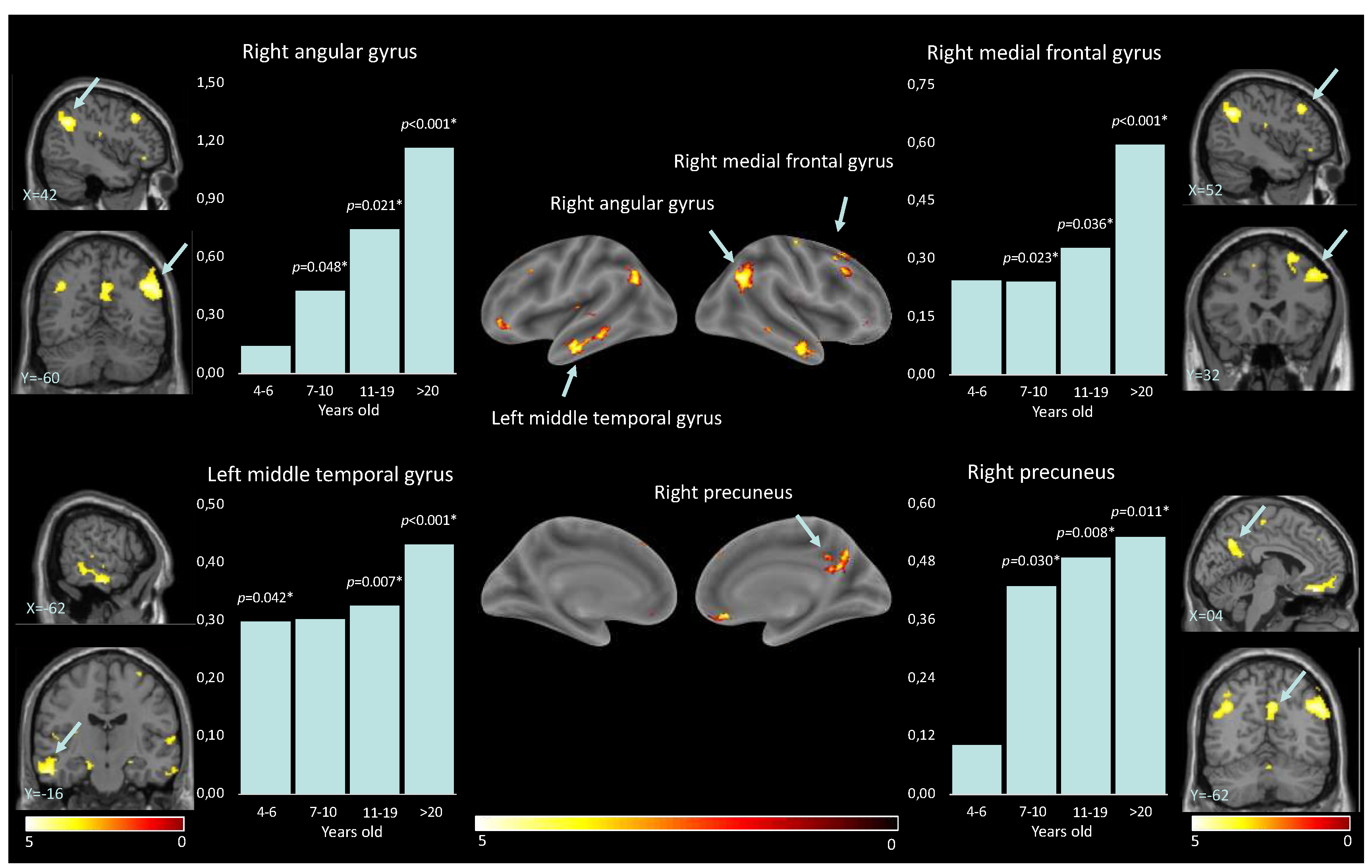

For the reverse contrast (i.e., higher activation while looking at others than oneself), developmental differences were also observed thanks to the paired t-tests. For the: right angular gyrus; left angular gyrus; right inferior temporal gyrus; right rectus; right precuneus; and right medial prefrontal cortex brain regions, discrimination between others and self increased with age starting at 7 y.o. (see details in

Table 4). For the left middle temporal gyrus, neural activities significantly differed for all between others and self-presentations, except for the 7-10 y.o. group. Within the right superior frontal gyrus, neural activities significantly differed between self-vs-other perception from teenage years (i.e., > 11 y.o.). Finally, for the left inferior orbital gyrus, other versus self-discrimination was true for all, but not for the 11-19 y.o. group (see details in

Table 4,

Figure 3).

Discussion

Human beings are inherently social and cooperation is essential for good life conditions. Consequently, we constantly read others' actions, gestures, and faces, relying on the core capacity to discriminate self-vs-others. Unveiling the emergence of self-vs-others‘ discrimination at the neural level across the development could reveal differences in social needs and help adapt learning environments, for example. To this end, we compared brain activity during self-vs-other stimuli, revealing a total of 11 brain regions whose activation maps significantly differ as a function of age groups.

First, two brain regions showed higher activation for the self than for the other across development; the MCC and the right postcentral gyrus. According to past work, the MCC is involved in a wide range of social cognitive processes (Lou et al., 2004), including self-referential processing (Denny et al., 2012) and empathy (Fan et al., 2011). Moreover, the MCC is a key node in both the salience network and the social brain, two networks closely interconnected and working together to support social cognition and behavior (Menon & Uddin, 2010). The MCC showed higher activity for oneself than others across development, except in middle age children (i.e., 7-10 yo.). This pattern could reflect a transient developmental shift, leading the MCC to be permeable to peers’ information in 7-10 y.o.; self-vs-other perceptions are less distinct allowing children to learn through peer-to-peer interactions and consequently improve their social skills. In line with this idea, a recent neuroimaging study revealed how 7-12 y.o. children activate specifically their salience network when watching peers but not adults performing unexpected actions (Chiron*, Notter”, et al., in prep.).

Activity within the right postcentral gyrus was increasingly higher for self-vs-others’ stimuli from 7 years old on, highlighting a gradual gain in discriminative abilities across development. The postcentral gyrus is involved in the processing of sensory information from the body and may play a role in the formation of body image and self-awareness (Salvato et al., 2020). However, the lack of significant activation in the 4-6.5-year-old group suggests that the ability to distinguish between self and others at the sensorimotor level may not be fully developed at this age.

Second, nine brain regions showed significantly higher activation for the other than for the self across development. Except for the left inferior orbital gyrus, which showed a non-linear developmental pattern, increasing neural activities for others were observed in participants from 7 years old within the right and left angular gyrus, the right precuneus, the right inferior temporal gyrus (ITG), the right rectus, and the right medial frontal gyrus (MFG), and beyond 10 years old within the left middle temporal gyrus and the right superior frontal gyrus. These findings suggest a developmental trajectory of a gradual gain in discriminative abilities for others-versus-self. These brain regions are all associated with different fundamental aspects of social cognition. In fact, social cognition relies on multisensory skills, such as audiovisual speech or face-voice integrations (the angular gyrus and the left middle temporal gyrus; Bernstein et al., 2008; Joassin et al., 2011; Seghier, 2013; Pourtois et al., 2005), somatosensory abilities (the MFG; Amodio & Frith, 2006), or perception and processing of complex visual stimuli, including facial expressions and emotional states or body language (the ITG, Haxby et al., 2001, 2000). Furthermore, social cognition relies on self-processing (Cavanna & Trimble, 2006), perspective-taking, empathy (the MFG), and theory of mind (the precuneus; Schilbach et al., 2006; Schurz et al., 2014). Additionally, social cognition relies on the ability to understand and respond to social cues, emotions, and the intentions of others (the right rectus; Hiser & Koenigs, 2018; Ruby & Decety, 2004). Finally, social cognition implies working memory and spatial processing (the right superior frontal gyrus; Boisgueheneuc et al., 2006; El-Baba & Schury, 2022; Job et al., 2021; Shelton et al., 2011); integrating social spatial cues to build a social network.

Both the angular gyrus and the precuneus are considered key nodes of the default mode network (DMN), a network of interconnected brain regions active during rest and self-referential mental activity (Li et al., 2014). It is also involved in social cognition and theory of mind, the ability to understand the mental states of others (Xie et al., 2016). It has been demonstrated that during childhood and adolescence, there is a functional reconfiguration of the DMN, which coincides with the period of social and cognitive development (Fan et al., 2021). There may be a link between the DMN and the representation of others in that they are both involved in processing self-referential information and constructing senses of self-related to others (i.e., tailoring perceptions). Therefore, the increase in other-perception activation in these regions may reflect the growing ability to engage in perspective-taking, empathy, and theory of mind. Our results further highlighted a particularly significant increase in the level of MFG activation for the > 20-year-old group when looking at others. One possible explanation is that older adults have greater social knowledge, which may enable them to process information about others in a more nuanced and sophisticated way. Therefore, these results could be linked to changes in the social environment or the types of social information that individuals are exposed to as they age. Alternatively, it could reflect changes in the way that older adults process social information, such as a greater focus on evaluating the emotional significance of social stimuli or a greater ability to integrate information from multiple sources.

Finally, the left inferior orbital gyrus showed a non-linear pattern, with a null difference between others- and self-perception in the 11-19 y.o. group. This brain region is known for being involved in reward value as well as emotion (Rolls et al., 2020). Emotional understanding is crucial for children’s successful social adjustment. In addition to developing appropriate social skills and prosocial responses to peers, children who are more successful at understanding emotions have a greater chance of forming positive interpersonal relationships that facilitate social adaptation (Martins et al., 2014; Rosnay et al., 2013). As the processing of emotions changes across the development, and during adolescence especially, it may become increasingly unstable, and more intense (Bailen et al., 2018).

Together, these results are consistent with previous research showing that self-referential processing is a fundamental aspect of human cognition and occurs early in development, continuing throughout life (Northoff et al., 2006). It happens concomitantly to the ability to discriminate others from oneself. However, we show that it is a complex and dynamic process.

A few limitations refrain from a clear generalization of our results. First, each age group had a limited sample size. As it is a clear challenge to have young children enrolled for an MRI study, it is even more complicated to address movement in a task-based fMRI experiment with 4- to 7-year-olds. However, future work should creatively find a way to overcome this aspect to replicate this work with a larger population, or at least use a longer task. Furthermore, here we tested same-gender, same-ethnicity social partners for the ‘other’ condition. However, this does not reflect real life where more diversity exists. We could invent stimuli to test variations in age, gender, or ethnicity to explore how social enrichment stimulates the social brain at best across development.

We show that while 4-6-y.o.-children have little discriminative skills, for both self and other perceptions, a developmental shift seems to operate from 6 years on, with transient periods in specific neural activities up to adulthood. However, all share a fundamental capacity for introspection and self-reflection that is essential to our understanding of the human mind and behavior, even very young children. These findings are important to better understand how social processing develops, and consequently when, why, and which social context can support learning processes across childhood and teen years.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to children and parents for their joyful participation in the study. We thank Mrs Marion Décaillet, Mr Philippe Eon Duval, and Mrs Coline Grasset for help with data collection and Mr Philippe Eon Duval for help with data preprocessing. Imaging was supported in part by the Centre d’Imagerie Biomédicale (CIBM) of the Université de Lausanne (UNIL), Université de Genève (UNIGE), Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève (HUG), Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV), Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), and the Leenaards and Jeantet Foundations. S.D. is supported by the Prepared Adult Initiative and the Société Académique Vaudoise. P.Z. is supported by Mr. Gianni Biaggi.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This study was approved by the local ethics commission (CER-VD 2018-00244).

References

- Amsterdam, B. (1972). Mirror self-image reactions before age two. Developmental Psychobiology, 5(4), 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, H. F., Kaplan, J., & Damasio, A. (2013). Cortical midline structures and autobiographical-self processes: An activation-likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7(SEP), 548. [CrossRef]

- Asakage, S., & Nakano, T. (2022). The salience network is activated during self-recognition from both first-person and third-person perspectives. Human Brain Mapping. [CrossRef]

- Bahrick, L. E. (2008). The Development of Perception in a Multimodal Environment. Theories of Infant Development, 90–120. [CrossRef]

- Bailen, N. H., Green, L. M., & Thompson, R. J. (2018). Understanding Emotion in Adolescents: A Review of Emotional Frequency, Intensity, Instability, and Clarity. Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/1754073918768878, 11(1), 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Beebe, B., & Lachmann, F. M. (2003). The contribution of mother-infant mutual influence to the origins of self- and object representations. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 5(4), 305. [CrossRef]

- Berlim De Mello, C., Da Silva, T., Cardoso, G., Vinicius, M., & Alves, C. (2023). Social Cognition Development and Socioaffective Dysfunction in Childhood and Adolescence. Social and Affective Neuroscience of Everyday Human Interaction, 161–175. [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J. (2008). The social brain in adolescence. [CrossRef]

- Brumariu, L. E. (2015). Parent–Child Attachment and Emotion Regulation. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2015(148), 31–45. [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, G. (1992). Origins of Self-Perception in Infancy. Source: Psychological Inquiry, 3(2), 103–111.

- Cavanna, A. E., & Trimble, M. R. (2006). The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain, 129(3), 564–583. [CrossRef]

- Decety, J., & Jackson, P. L. (2004). The Functional Architecture of Human Empathy. Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/1534582304267187, 3(2), 71–100. [CrossRef]

- Denny, B. T., Kober, H., Wager, T. D., & Ochsner, K. N. (2012a). A Meta-Analysis of Functional Neuroimaging Studies of Self and Other Judgments Reveals a Spatial Gradient for Mentalizing in Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(8), 1742. [CrossRef]

- Denny, B. T., Kober, H., Wager, T. D., & Ochsner, K. N. (2012b). A Meta-Analysis of Functional Neuroimaging Studies of Self and Other Judgments Reveals a Spatial Gradient for Mentalizing in Medial Prefrontal Cortex. [CrossRef]

- Devue, C., & Brédart, S. (2011). The neural correlates of visual self-recognition. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(1), 40–51. [CrossRef]

- Faghiri, A., Stephen, J. M., Wang, Y.-P., Wilson, T. W., & Calhoun, V. D. (2019). Brain Development Includes Linear and Multiple Nonlinear Trajectories: A Cross-Sectional Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Brain Connectivity, 9(10), 777. [CrossRef]

- Falk, A., Kosse, F., Schildberg-Hörisch, H., & Zimmermann, F. (2020). Self-Assessment: The Role of the Social Environment. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Fan, F., Liao, X., Lei, T., Zhao, T., Xia, M., Men, W., Wang, Y., Hu, M., Liu, J., Qin, S., Tan, S., Gao, J. H., Dong, Q., Tao, S., & He, Y. (2021). Development of the default-mode network during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal resting-state fMRI study. NeuroImage, 226, 117581. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., Duncan, N. W., de Greck, M., & Northoff, G. (2011). Is there a core neural network in empathy? An fMRI based quantitative meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 903–911. [CrossRef]

- Farrer, C., & Frith, C. D. (2002). Experiencing Oneself vs Another Person as Being the Cause of an Action: The Neural Correlates of the Experience of Agency. NeuroImage, 15(3), 596–603. [CrossRef]

- Frith, C. D. (2008). Social cognition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363(1499), 2033–2039. [CrossRef]

- Haxby, Gobbini, J. V. ;, Furey, M. I. ;, Ishai, M. L. ;, Schouten, A. ;, & Pietrini, J. L. ; (2001). Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. [CrossRef]

- Haxby, J. V., Hoffman, E. A., & Gobbini, M. I. (2000). The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(6), 223–233. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C., Di, X., Eickhoff, S. B., Zhang, M., Peng, K., Guo, H., & Sui, J. (2016). Distinct and common aspects of physical and psychological self-representation in the brain: A meta-analysis of self-bias in facial and self-referential judgements. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 61, 197–207. [CrossRef]

- Jastorff, J., & Orban, G. A. (2009). Human Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Reveals Separation and Integration of Shape and Motion Cues in Biological Motion Processing.

- Job, X., Kirsch, L., Inard, S., Arnold, G., & Auvray, M. (2021). Spatial perspective taking is related to social intelligence and attachment style. Personality and Individual Differences, 168. [CrossRef]

- Lang, F. R., & Reschke, F. S. (2006). Social Relationships, Transitions, and Personality Development Across the Life Span. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-07023-023.

- Li, W., Mai, X., & Liu, C. (2014). The default mode network and social understanding of others: What do brain connectivity studies tell us. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8(1 FEB), 74. [CrossRef]

- Lippé, S., Kovacevic, N., & McIntosh, A. R. (2009). Differential maturation of brain signal complexity in the human auditory and visual system. [CrossRef]

- Lou, H. C., Luber, B., Crupain, M., Keenan, J. P., Nowak, M., Kjaer, T. W., Sackeim, H. A., & Lisanby, S. H. (2004). Parietal cortex and representation of the mental Self. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(17), 6827–6832. [CrossRef]

- Mazaika, P. K., Hoeft, F., Glover, G. H., & Reiss, A. L. (2009). Methods and Software for fMRI Analysis for Clinical Subjects. In AFNI Software. Comp. Biomed. Res (Vol. 11, Issue 3). http://cibsr.stanford.edu.

- Menon, V., & Uddin, L. Q. (2010). Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Structure & Function, 214(5–6), 655–667. [CrossRef]

- Murray, R. J., Schaer, M., & Debbané, M. (2012). Degrees of separation: A quantitative neuroimaging meta-analysis investigating self-specificity and shared neural activation between self- and other-reflection. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(3), 1043–1059. [CrossRef]

- Northoff, G., Heinzel, A., de Greck, M., Bermpohl, F., Dobrowolny, H., & Panksepp, J. (2006). Self-referential processing in our brain—A meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. NeuroImage, 31(1), 440–457. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, J. H., & Berkman, E. T. (2018). The Development of Self and Identity in Adolescence: Neural Evidence and Implications for a Value-Based Choice Perspective on Motivated Behavior. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 158. [CrossRef]

- Platek, S. M., Thomson, J. W., & Gallup, G. G. (2004). Cross-modal self-recognition: The role of visual, auditory, and olfactory primes. Consciousness and Cognition, 13(1), 197–210. [CrossRef]

- Posner, M. I. Posner, M. I., Rothbart, M. K., & Sheese, B. E. (2007). The anterior cingulate gyrus and the mechanism of self-regulation.

- Qin, P., & Northoff, G. (2011). How is our self related to midline regions and the default-mode network? NeuroImage, 57(3), 1221–1233. [CrossRef]

- Rochat, P. (1998). Self-perception and action in infancy. Exp Brain Res, 123, 102–109.

- Rolls, E. T., Huang, C. C., Lin, C. P., Feng, J., & Joliot, M. (2020). Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. NeuroImage, 206. [CrossRef]

- Ruby, P., & Decety, J. (2004). How Would You Feel versus How Do You Think She Would Feel? A Neuroimaging Study of Perspective-Taking with Social Emotions. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16(6), 988–999. [CrossRef]

- Salvato, G., Richter, F., Sedeño, L., Bottini, G., & Paulesu, E. (2020). Building the bodily self-awareness: Evidence for the convergence between interoceptive and exteroceptive information in a multilevel kernel density analysis study. Human Brain Mapping, 41(2), 401. [CrossRef]

- Schilbach, L., Wohlschlaeger, A. M., Kraemer, N. C., Newen, A., Shah, N. J., Fink, G. R., & Vogeley, K. (2006). Being with virtual others: Neural correlates of social interaction. Neuropsychologia, 44(5), 718–730. [CrossRef]

- Schurz, M., Radua, J., Aichhorn, M., Richlan, F., & Perner, J. (2014). Fractionating theory of mind: A meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 42, 9–34. [CrossRef]

- Shelton, A. L., Clements-Stephens, A. M., Lam, W. Y., Pak, D. M., & Murray, A. J. (2011). Should social savvy equal good spatial skills? The interaction of social skills with spatial perspective taking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(2), 199. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., Mulej Bratec, S., Schmid, G., Meng, C., Doll, A., Wohlschläger, A., Finke, K., Förstl, H., Zimmer, C., Pekrun, R., Schilbach, L., Riedl, V., & Sorg, C. (2016). How do you make me feel better? Social cognitive emotion regulation and the default mode network. NeuroImage, 134, 270–280. [CrossRef]

- Young, S. N. (2008). The neurobiology of human social behaviour: an important but neglected topic. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience : JPN, 33(5), 391. /pmc/articles/PMC2527715/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).