Submitted:

19 October 2023

Posted:

21 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Basic principles of microwaves and ultrasounds (Part I)

2.1. Microwaves radiation

2.1.1. Conventional heating and microwave heating

2.1.2. Microwave heating mechanisms

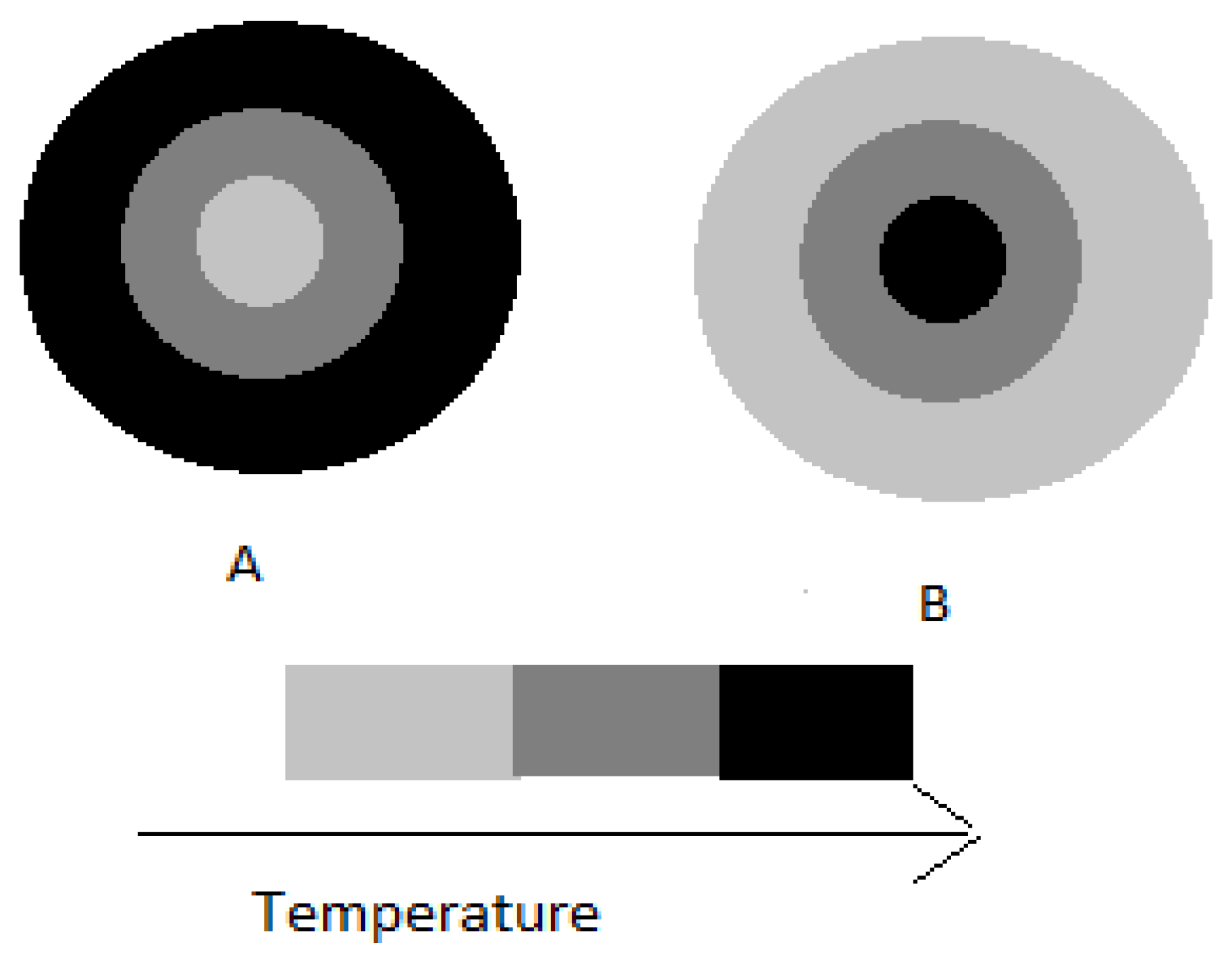

2.1.3. Behaviour of materials in relation to microwave radiation

2.1.4. Behavior of lignocellulosic biomass in relation to microwave radiation

2.1.5. Microwave absorbing materials to add to lignocellulosic biomass

2.1.6. Factors to consider in a microwave pretreatment for lignocellulosic biomass

2.1.7. The reasons justifying microwave absorption and lignocellulosic biomass recalcitrance

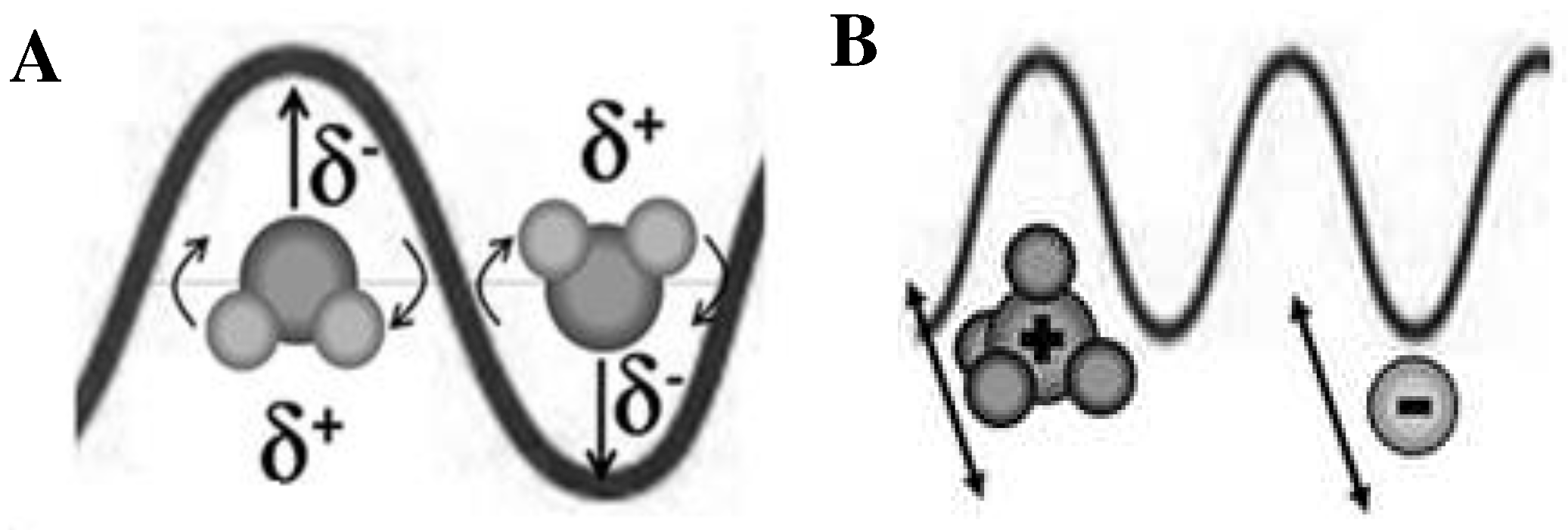

2.2. Ultrasounds and two categories of ultrasounds

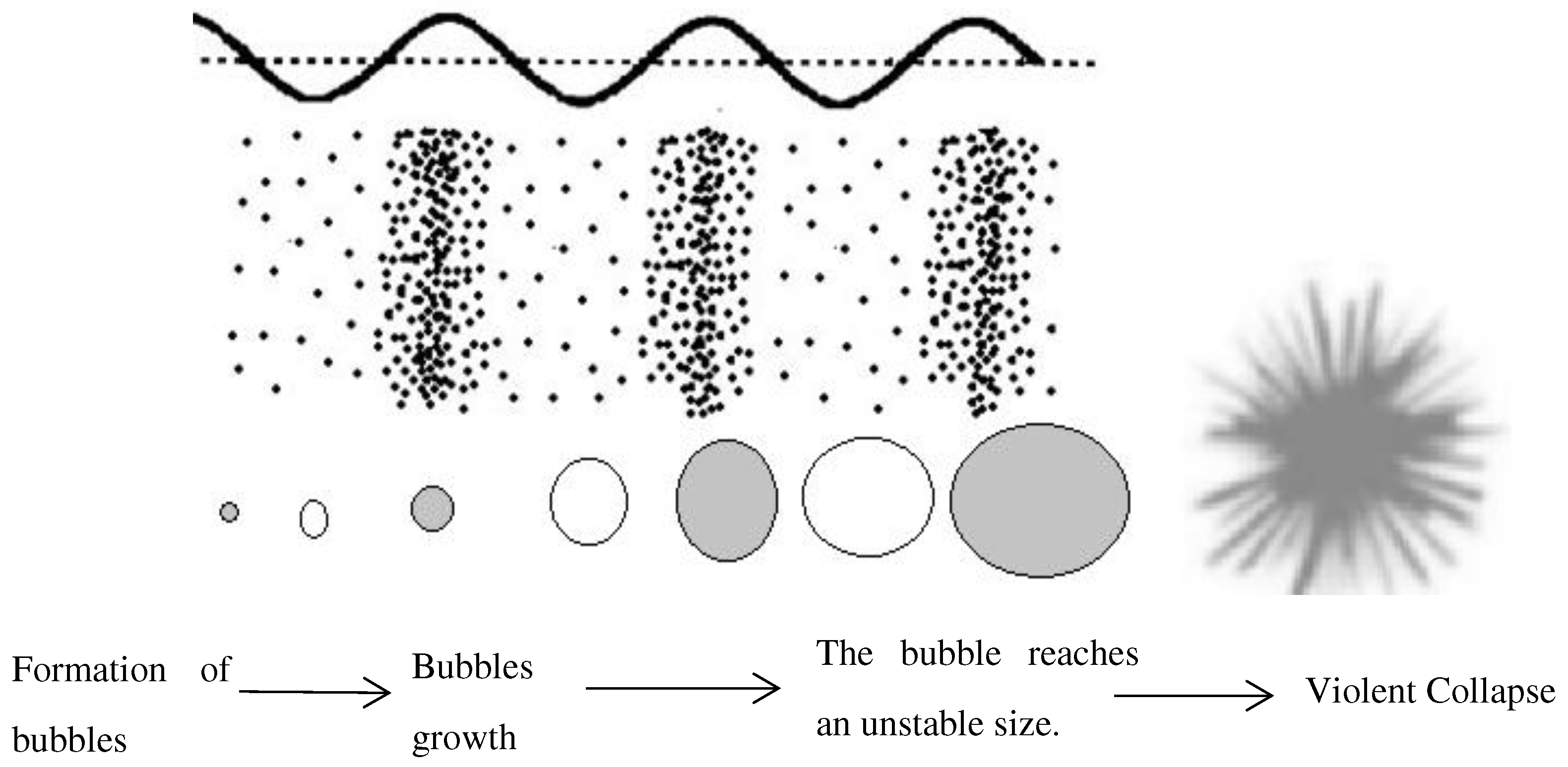

2.2.1. Basic principles of cavitation

2.2.2. Factors that influence the cavitation of lignocellulosic biomass

2.2.3. Physical effects and chemical effects of ultrasound on lignocellulosic biomass

3. Pre-treatments with microwave and/or ultrasound (Part II)

3.1. The types of microwave and/or ultrasound pretreatments

3.2. Physical effects and chemical effects of ultrasound on lignocellulosic biomass

3.2.1. Effect on particle size and surface area

| Biomass | Pretreatment | Particle size ) |

Specific surface area (m2g-1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residues from the herb extraction process | No treatment | 197.0 | 0.38 | [53] |

| Alkaline (NaOH) | 187.5 | 0.44 | ||

| Water and MW | 179.8 | 0.51 | ||

| Alkaline (NaOH) + MW | 163.5 | 0.63 | ||

| Hemp stalk | No treatment | ………. | 1.30 | [57] |

| With MEP1 | ……. | 1.85 | ||

| Microalgae Scenedesmus | No treatment | 7.4 | N. d. | |

| US | 5.1 | N.d. | [56] | |

| Hovenia dulcis and Ampelopsis grossedentata | No treatment | 14.802 | N.d. | [58] |

| Negative pressure and US2 | 3.719 | N.d. |

3.2.2. Effect on lignin, hemicellulose and cellulose content

3.2.3. Effect on on cellulose crystallinity index

| Biomass | Pretreatment | Operating conditions | crystallinity index (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kenaf powder |

No treatment | 49.4 | [67] |

|

| Ionic liquid | 38.8 | |||

| Ionic liquid +US | P= 35 W f= 24 kHz ∆t = 15 min T= 25 °C |

31.5 | ||

| water hyacinth water hyacinth |

No treatment | 19.50 | [66] |

|

| Ionic liquid | 32.44 | |||

| Ionic liquid + US | P= 100 W f= 20 kHz ∆t = 45 min T= 120 °C |

30.74 | ||

| Ionic liquid +US + SDS1 | P= 100 W f= 20 kHz ∆t = 45 min T=120 °C |

28.73 | ||

| Eucalyptus powder (Eucalyptus grandis) |

No treatment | 31.8 | [68] |

|

| Soda solution + US | P= 300 W f= 28 kHz ∆t = 30 min T= 50 °C |

34.7 |

||

| Water + US | P= 300 W f= 28kHz ∆t = 30 min T= 50 °C |

32.6 |

||

| Acetic acid + US | P= 300 W f= 28kHz ∆t = 30 min T= 50 °C |

33.4 |

||

| Cupuaçu husk (Theobroma grandiflorum) |

No treatment | 54.3 | [69] |

|

| Water + US | P= 100 W f= 40 kHz ∆t= 30 min T= 35 °C |

60.0 | ||

| Acid (HCl) + US | P= 100 W f= 40 kHz ∆t= 30 min T= 35° C |

63.3 | ||

| Alkaline (NaOH) + US | P= 100 W f= 40 kHz ∆t= 30 min T= 35 °C |

57.0 | ||

| Ionic liquid +US | P= 100 W f= 40 kHz ∆t= 30 min T= 35 °C |

58.2 |

3.2.4. Effect on the solubilization of organic matter

3.2.5. Effect on the solubilization of organic matter

| Biomass | Pretreatment | Operating conditions |

Glucose production |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil palm trunk | Acid (H2SO4) +MW | P= 450 W ∆t= 7.5 min |

8.95 mg/L | [72] |

| Rice straw | Alkaline (NaOH) + MW | P= 681 W ∆t= 3 min |

255 g/g1 | [1] |

| Pine chips | No treatment | 77.3 mg/g1 |

[75] |

|

| water + MW | P= 600 W ∆t= 60 min Pressure= 117 Psi |

81.5 mg/g1 | ||

| NaCs2 + MW | P= 600 W ∆t= 60 min Pressure= 117 Psi |

107.8mg/g1 | ||

| Beech chips | No treatment | 35.0 mg/g1 |

[75] |

|

| water + MW | P= 600 W ∆t= 60 min Pressure= 117 Psi |

278.0 mg/g1 | ||

| NaCs2 + MW | P= 600 W ∆t= 60 min Pressure= 117 Psi |

515.5 mg/g1 | ||

| Wheat straw | No treatment | 0.0 mg/g1 |

[75] |

|

| water + MW | P= 600 W ∆t= 60 min Pressure= 117 Psi |

435.8 mg/g1 | ||

| NaCs2 + MW | P= 600 W ∆t= 60 min Pressure= 117 Psi |

557.3 mg/g1 | ||

| No treatment | 3.14 g/L |

[69] |

||

| Residues of cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum) |

water + US | P= 100 W f= 24 kHz ∆t= 30 min |

8.44 g/L | |

| Acid (HCl) + US | P= 100 W f= 24 kHz ∆t= 30 min |

9.90 g/L | ||

| Alkaline (NaOH) + US | P= 100 W f= 24 kHz ∆t= 30 min |

6.08 g/L |

4. Microwaves and ultrasounds on the route of value-added products (Part III)

4.1. Liquefactions

4.1.1. Ultrasound-assisted liquefactions

4.1.2. Microwave-assisted liquefactions

4.1.3. Liquefactions assisted simultaneously by microwave and ultrasound

| Biomass | Type of liquefaction |

Liquefaction time (min) | Liquefaction yield (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium density fiberboard (MDF) |

Conventional | 90 | 93.8 | [78] |

| US | 10 | 94.9 | ||

| Wheat straw | Conventional | 90 | 94.4 | |

| US | 15 | 95.4 | ||

| Veneered particleboard | Conventional | 120 | 95.0 | |

| US | 20 | 96.0 | ||

| Cork powder | Conventional | 135 | 95.0 | [79] |

| US | 75 | 98.0 | ||

| Poplar sawdust | Conventional | …. | …. | [80] |

| MW | 7 | 100 | ||

| Corn stover and corncob | Conventional | …. | …. | [81] |

| MW | 20 | 95 | ||

| Bamboo wastes | Conventional | …. | …. | [82] |

| MW | 7 | 96.7 | ||

| Bamboo sawdust | Conventional | ….. | ….. | [83] |

| MW | 8 | 78 | ||

| Fir sawdust | Conventional | 60 | …. | [84] |

| MW+US | 20 | 91 | ||

| Conventional | 60 | … | [85] | |

| MW+US | …. |

4.2. Microwave-assisted and/or ultrasound-assisted extractions

| Biomass | Type of Extraction |

Power | Solvent | Extraction time (min) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eucalyptus robusta * | MW | 600 W | water | 3 | [87] |

| Eucalyptus robusta * | US | 250 W | water | 90 | [88] |

| Eucalyptus globulus | conventional | Medium |

Ethanol 56 % (V:V) |

225 | [90] |

| US | 90 | ||||

| MW | 7 | ||||

| Lemon peel residues* |

US | Amplitude 38 % | Ethanol: water 55:45 |

4 | [91] |

| MW | 140 W | 0.75 | |||

| Spatholobus suberectus | conventional | 100 % Methanol | 360 | [92] | |

| US | 30-250 W | 70 % Methanol | 60 | ||

| MS | 100-500 W | 70 % Methanol | 30 | ||

| MS +US | 100-500 W 30-250 W |

Methanol 30–100 % + Pure ethanol |

7.5 | ||

| (Coriandrum sativum L.) * | MW | 500 W | 50 % ethanol | 4 | [22] |

4.3. Factors influencing microwave- and ultrasound-assisted extraction

4.4. Emerging routes in extraction

5. Sonocatalysis of lignocellulosic biomass (Part IV)

5.1. Examples of hydrolysis

5.2. Examples of hydrogenations

5.3. Examples of oxidations

| Reaction | Biomass | Operating conditions |

Product | Main conclusion |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis | Bamboo (Gigantochloa scortechinii) |

Ultrasounds 20 kHz, 300 W 10 min, 140 ° C Catalyst: ionic liquid CrCl3 |

5_HMF | From 3 hours from the conventional route to 10 minutes. | [97] |

| Soybean straw and corn straw |

Ultrasounds Bath, 120 min, 70 ° C Catalyst: ionic liquid ([HMIM] Cl) |

Reducing sugars | Simple and economical approach. | [98] | |

| Cellulose |

Ultrasounds 20 kHz, 60 min, 30°C Catalyst: Diluted HNO3 |

FF | Simple synthesis, in 60 min, with yield 78%. | [99] | |

| Potato starch waste |

Ultrasounds 20 kHz and 500 kHz, 120 min, 60 ° C Catalyst: H2SO4 |

Reducing sugars | 70% yield with 20kHz ultrasounds and 84% yield with 500kHz. | [100] | |

| Banana peels |

Ultrasounds 20 kHz, 240 watts Catalyst: H2SO4 |

5_HMF | Production of 50 g/L 5_HMF after 1 h | [23] | |

| Pre-treated sugars obtained from cupuaçu husk (Theobroma grandiflorum) |

Ultrasound It doesn't mention power. 60 min, 140 °C Catalyst: ionic liquid [BMIM][Br] |

FF 5_HMF |

Synthesis with yield of 12.94%, in 5_HMF and 48.84% in FF, in one hour | [69] | |

| Hydrogenation | D- Fructose |

Ultrasounds 20 kHz, 50 W 20 min, 110 °C Catalysts: Cu / SiO2 Raney-Ni, CuO / ZnO /Al2O 3 |

D-mannitol | Cu/SiO2 was the catalyst with better performance. | [101] |

| Lignin from Miscanthus giganteus |

Ultrasounds 35 kHz, 6 h, 25 °C Catalysts: Fe3O4(NiAlO)x, Fe3O4(NiMgAlO)x, ionic liquid [BMIM]OAc |

Low molecular weight compounds |

The performances of the catalysts, under ultrasonic conditions, were inferior to those exhibited with conventional heating. | [102] | |

| Gross FAMEs |

Ultrasounds 40 kHz, 120 W, 35 °C Catalyst: Amorphous alloy of doped nickel boride with La Li-La-B. |

hydrogenated FAMEs |

Intensification of hydrogenation by catalytic transfer, due to the incidence of ultrasound. The same catalyst can be used at least 5 times. |

[103] | |

| Oxidation | Cotton pulp |

Ultrasounds 40 kHz, 300 watts Catalyst: TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidine-N-oxyl) |

Nanocellulose with high COOH content | Cellulose nanocrystals stable in water |

[105] |

| Hardwood Kraft Pulp |

Ultrasounds 68 and 170 kHz, 1000 W Catalyst: TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidine-N-oxyl) |

Nanocellulose with high COOH content | Oxidation selective, in primary hydroxyl groups (C6). |

[104] | |

| FF | High-frequency ultrasound 525 to 565 kHz T=42ºC It uses. H2O2 No catalyst |

Maleic acid | Promising route that dispenses with catalyst, uses mild temperatures and high-frequency ultrasound | [106] |

5.3. Sonophotocatalysis, the emerging area

6. Conclusion

7. Challenges and opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jasmine A, Rajendran M, Thirunavukkarasu K, et al (2023) Microwave-assisted alkali pre-treatment medium for fractionation of rice straw and catalytic conversion to value-added 5-hydroxymethyl furfural and lignin production. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 236:123999. [CrossRef]

- Bhutto AW, Qureshi K, Harijan K, et al (2017) Insight into progress in pre-treatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Energy 122:724–745. [CrossRef]

- Kumar B, Bhardwaj N, Agrawal K, et al (2020) Current perspective on pretreatment technologies using lignocellulosic biomass: An emerging biorefinery concept. Fuel Processing Technology 199:106244. [CrossRef]

- Luo J, Fang Z, Smith RL (2014) Ultrasound-enhanced conversion of biomass to biofuels. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 41:56–93. [CrossRef]

- Roy R, Rahman MS, Raynie DE (2020) Recent advances of greener pretreatment technologies of lignocellulose. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 3:100035. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia SK, Jagtap SS, Bedekar AA, et al (2020) Recent developments in pretreatment technologies on lignocellulosic biomass: Effect of key parameters, technological improvements, and challenges. Bioresource Technology 300:122724. [CrossRef]

- Lorenci Woiciechowski A, Dalmas Neto CJ, Porto de Souza Vandenberghe L, et al (2020) Lignocellulosic biomass: Acid and alkaline pretreatments and their effects on biomass recalcitrance – Conventional processing and recent advances. Bioresource Technology 304:122848. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Reynosa A, Romaní A, Ma. Rodríguez-Jasso R, et al (2017) Microwave heating processing as alternative of pretreatment in second-generation biorefinery: An overview. Energy Conversion and Management 136:50–65. [CrossRef]

- Anu, Kumar A, Rapoport A, et al (2020) Multifarious pretreatment strategies for the lignocellulosic substrates for the generation of renewable and sustainable biofuels: A review. Renewable Energy 160:1228–1252. [CrossRef]

- Haldar D, Sen D, Gayen K (2016) A review on the production of fermentable sugars from lignocellulosic biomass through conventional and enzymatic route—a comparison. International Journal of Green Energy 13:1232–1253. [CrossRef]

- Kumar AK, Sharma S (2017) Recent updates on different methods of pretreatment of lignocellulosic feedstocks: a review. Bioresour Bioprocess 4:7. [CrossRef]

- Kumari D, Singh R (2018) Pretreatment of lignocellulosic wastes for biofuel production: A critical review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 90:877–891. [CrossRef]

- Rezania S, Oryani B, Cho J, et al (2020) Different pretreatment technologies of lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol production: An overview. Energy 199:117457. [CrossRef]

- Haldar D, Purkait MK (2021) A review on the environment-friendly emerging techniques for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: Mechanistic insight and advancements. Chemosphere 264:128523. [CrossRef]

- Hassan SS, Williams GA, Jaiswal AK (2018) Emerging technologies for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresource Technology 262:310–318. [CrossRef]

- Vu HP, Nguyen LN, Vu MT, et al (2020) A comprehensive review on the framework to valorise lignocellulosic biomass as biorefinery feedstocks. Science of The Total Environment 743:140630. [CrossRef]

- Loow Y-L, Wu TY, Yang GH, et al (2016) Role of energy irradiation in aiding pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for improving reducing sugar recovery. Cellulose 23:2761–2789. [CrossRef]

- Mehta S, Jha S, Liang H (2020) Lignocellulose materials for supercapacitor and battery electrodes: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 134:110345. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava N, Mor RS, Kumar K, Sharanagat VS (2021) Advances in application of ultrasound in food processing: A review. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 70:105293. [CrossRef]

- Mathiarasu A, Pugazhvadivu M (2023) Studies on dielectric properties and microwave pyrolysis of karanja seed. Biomass Conv Bioref 13:2895–2905. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen LH, Naficy S, Chandrawati R, Dehghani F (2019) Nanocellulose for Sensing Applications. Advanced Materials Interfaces 6:1900424. [CrossRef]

- Mouhoubi K, Boulekbache-Makhlouf L, Madani K, et al (2023) Microwave-assisted extraction optimization and conventional extraction of phenolic compounds from coriander leaves: UHPLC characterization and antioxidant activity. Nor Afr J Food Nutr Res 7:69–83. [CrossRef]

- Dutta A, Kininge MM, Priya, Gogate PR (2023) Intensification of delignification and subsequent hydrolysis of sustainable waste as banana peels for the HMF production using ultrasonic irradiation. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 183:109247. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y-F, Chiueh P-T, Lo S-L (2016) A review on microwave pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Sustainable Environment Research 26:103–109. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Rajagopalan K, Lei H, et al (2017) An overview of a novel concept in biomass pyrolysis: microwave irradiation. Sustainable Energy Fuels 1:1664–1699. [CrossRef]

- Fia AZ, Amorim J (2023) Microwave pretreatment of biomass for conversion of lignocellulosic materials into renewable biofuels. Journal of the Energy Institute 106:101146. [CrossRef]

- Leonelli C, Mason TJ (2010) Microwave and ultrasonic processing: Now a realistic option for industry. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification 49:885–900. [CrossRef]

- Salema AA, Yeow YK, Ishaque K, et al (2013) Dielectric properties and microwave heating of oil palm biomass and biochar. Industrial Crops and Products 50:366–374. [CrossRef]

- Salema AA, Ani FN, Mouris J, Hutcheon R (2017) Microwave dielectric properties of Malaysian palm oil and agricultural industrial biomass and biochar during pyrolysis process. Fuel Processing Technology 166:164–173. [CrossRef]

- Farag S, Sobhy A, Akyel C, et al (2012) Temperature profile prediction within selected materials heated by microwaves at 2.45GHz. Applied Thermal Engineering 36:360–369. [CrossRef]

- Omar R, Idris A, Yunus R, et al (2011) Characterization of empty fruit bunch for microwave-assisted pyrolysis. Fuel 90:1536–1544. [CrossRef]

- Bossou OV, Mosig JR, Zurcher J-F (2010) Dielectric measurements of tropical wood. Measurement 43:400–405. [CrossRef]

- El-Meligy MG, Mohamed SH, Mahani RM (2010) Study mechanical, swelling and dielectric properties of prehydrolysed banana fiber – Waste polyurethane foam composites. Carbohydrate Polymers 80:366–372. [CrossRef]

- Issa AA, Al-Degs YS, Mashal K, Al Bakain RZ (2015) Fast activation of natural biomasses by microwave heating. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 21:230–238. [CrossRef]

- Motasemi F, Afzal MT, Salema AA (2014) Microwave dielectric characterization of hay during pyrolysis. Industrial Crops and Products 61:492–498. [CrossRef]

- Fares O, AL-Oqla FM, Hayajneh MT (2019) Dielectric relaxation of mediterranean lignocellulosic fibers for sustainable functional biomaterials. Materials Chemistry and Physics 229:174–182. [CrossRef]

- Bichot A, Lerosty M, Radoiu M, et al (2020) Decoupling thermal and non-thermal effects of the microwaves for lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment. Energy Conversion and Management 203:112220. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Nie Y, Lu X, et al (2019) Cascade utilization of lignocellulosic biomass to high-value products. Green Chem 21:3499–3535. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Dai J, Liu G, et al (2016) Biochar from microwave pyrolysis of biomass: A review. Biomass and Bioenergy 94:228–244. [CrossRef]

- Shabbirahmed AM, Joel J, Gomez A, et al (2023) Environment friendly emerging techniques for the treatment of waste biomass: a focus on microwave and ultrasonication processes. Environ Sci Pollut Res. [CrossRef]

- Islam MH, Burheim OS, Pollet BG (2019) Sonochemical and sonoelectrochemical production of hydrogen. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 51:533–555. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi VK, Lo S-L, Appels L, Dewil R (2014) Ultrasonic Treatment of Waste Sludge: A Review on Mechanisms and Applications. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 44:1220–1288. [CrossRef]

- Bundhoo ZMA, Mohee R (2018) Ultrasound-assisted biological conversion of biomass and waste materials to biofuels: A review. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 40:298–313. [CrossRef]

- Bussemaker MJ, Zhang D (2013) Effect of Ultrasound on Lignocellulosic Biomass as a Pretreatment for Biorefinery and Biofuel Applications. Ind Eng Chem Res 52:3563–3580. [CrossRef]

- Karimi M, Jenkins B, Stroeve P (2014) Ultrasound irradiation in the production of ethanol from biomass. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 40:400–421. [CrossRef]

- Le NT, Julcour-Lebigue C, Delmas H (2015) An executive review of sludge pretreatment by sonication. Journal of Environmental Sciences 37:139–153. [CrossRef]

- Kuna E, Behling R, Valange S, et al (2018) Sonocatalysis: A Potential Sustainable Pathway for the Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass and Derivatives. In: Lin CSK (ed) Chemistry and Chemical Technologies in Waste Valorization. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 1–20.

- Ong VZ, Wu TY (2020) An application of ultrasonication in lignocellulosic biomass valorisation into bio-energy and bio-based products. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 132:109924. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Yan L, Ma X, et al (2018) Ultrasound promotes enzymatic reactions by acting on different targets: Enzymes, substrates and enzymatic reaction systems. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 119:453–461. [CrossRef]

- Gaudino EC, Cravotto G, Manzoli M, Tabasso S (2020) Sono- and mechanochemical technologies in the catalytic conversion of biomass. Chem Soc Rev. [CrossRef]

- Bundhoo ZMA (2018) Microwave-assisted conversion of biomass and waste materials to biofuels. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 82:1149–1177. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Yao S, Narale BA, et al (2022) Ultrasonic Processing of Food Waste to Generate Value-Added Products. Foods 11:2035. [CrossRef]

- Cheng X-Y, Liu C-Z (2010) Enhanced biogas production from herbal-extraction process residues by microwave-assisted alkaline pretreatment. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 85:127–131. [CrossRef]

- Peng H, Chen H, Qu Y, et al (2014) Bioconversion of different sizes of microcrystalline cellulose pretreated by microwave irradiation with/without NaOH. Applied Energy 117:142–148. [CrossRef]

- Khanal SK, Montalbo M, Leeuwen J (Hans) van, et al (2007) Ultrasound enhanced glucose release from corn in ethanol plants. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 98:978–985. [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández C, Sialve B, Bernet N, Steyer JP (2012) Comparison of ultrasound and thermal pretreatment of Scenedesmus biomass on methane production. Bioresource Technology 110:610–616. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Wang Y, Li K, et al (2023) Microwave-assisted separation hemicellulose from hemp stalk: Extracting performance, extracting mechanism and mass transfer model. Industrial Crops and Products 197:116619. [CrossRef]

- Oh H, Kim J-H (2023) Development of an ultrasound-negative pressure cavitation fractional precipitation for the purification of (+)-dihydromyricetin from biomass. Korean J Chem Eng 40:1133–1140. [CrossRef]

- Chen W-H, Tu Y-J, Sheen H-K (2011) Disruption of sugarcane bagasse lignocellulosic structure by means of dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment with microwave-assisted heating. Applied Energy 88:2726–2734. [CrossRef]

- Boonmanumsin P, Treeboobpha S, Jeamjumnunja K, et al (2012) Release of monomeric sugars from Miscanthus sinensis by microwave-assisted ammonia and phosphoric acid treatments. Bioresource Technology 103:425–431. [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss G, Muthukumar K (2014) Ultrasound assisted ammonia pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse for fermentable sugar production. Biochemical Engineering Journal 83:33–41. [CrossRef]

- Oladunjoye AO, Olawuyi IK, Afolabi TA (2023) Synergistic effect of ultrasound and citric acid treatment on functional, structural and storage properties of hog plum (Spondias mombin L) bagasse. Food sci technol int 10820132231176580. [CrossRef]

- Binod P, Satyanagalakshmi K, Sindhu R, et al (2012) Short duration microwave assisted pretreatment enhances the enzymatic saccharification and fermentable sugar yield from sugarcane bagasse. Renewable Energy 37:109–116. [CrossRef]

- Lin R, Cheng J, Song W, et al (2015) Characterisation of water hyacinth with microwave-heated alkali pretreatment for enhanced enzymatic digestibility and hydrogen/methane fermentation. Bioresource Technology 182:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Debnath B, Duarah P, Purkait MK (2023) Microwave-assisted quick synthesis of microcrystalline cellulose from black tea waste (Camellia sinensis) and characterization. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 244:125354. [CrossRef]

- Chang K-L, Han Y-J, Wang X-Q, et al (2017) The effect of surfactant-assisted ultrasound-ionic liquid pretreatment on the structure and fermentable sugar production of a water hyacinth. Bioresource Technology 237:27–30. [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya K, Kamide K, Takahashi K, Shimizu N (2012) Enhanced enzymatic saccharification of kenaf powder after ultrasonic pretreatment in ionic liquids at room temperature. Bioresource Technology 103:259–265. [CrossRef]

- He Z, Wang Z, Zhao Z, et al (2017) Influence of ultrasound pretreatment on wood physiochemical structure. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 34:136–141. [CrossRef]

- Marasca N, Cardoso IA, Rambo MKD, et al (2022) Ultrasound Assisted Pretreatments Applied to Cupuaçu Husk (Theobroma grandiflorum) from Brazilian Legal Amazon for Biorefinery Concept. J Braz Chem Soc 33:906–915. [CrossRef]

- Passos F, Carretero J, Ferrer I (2015) Comparing pretreatment methods for improving microalgae anaerobic digestion: Thermal, hydrothermal, microwave and ultrasound. Chemical Engineering Journal 279:667–672. [CrossRef]

- Paul R, Silkina A, Melville L, et al (2023) Optimisation of Ultrasound Pretreatment of Microalgal Biomass for Effective Biogas Production through Anaerobic Digestion Process. Energies 16:553. [CrossRef]

- Khamtib S, Plangklang P, Reungsang A (2011) Optimization of fermentative hydrogen production from hydrolysate of microwave assisted sulfuric acid pretreated oil palm trunk by hot spring enriched culture. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 36:14204–14216. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Z, Macquarrie DJ, Simister R, et al (2015) Microwave assisted chemical pretreatment of Miscanthus under different temperature regimes. Sustain Chem Process 3:15. [CrossRef]

- Eblaghi M, Niakousari M, Sarshar M, Mesbahi GR (2016) Combining Ultrasound with Mild Alkaline Solutions as an Effective Pretreatment to Boost the Release of Sugar Trapped in Sugarcane Bagasse for Bioethanol Production. Journal of Food Process Engineering 39:273–282. [CrossRef]

- Mikulski D, Kłosowski G (2023) Cellulose hydrolysis and bioethanol production from various types of lignocellulosic biomass after microwave-assisted hydrotropic pretreatment. Renewable Energy 206:168–179. [CrossRef]

- Sawhney D, Vaid S, Bangotra R, et al (2023) Proficient bioconversion of rice straw biomass to bioethanol using a novel combinatorial pretreatment approach based on deep eutectic solvent, microwave irradiation and laccase. Bioresource Technology 375:128791. [CrossRef]

- Domingos I, Ferreira J, Cruz-Lopes LP, Esteves B (2022) Liquefaction and chemical composition of walnut shells. Open Agriculture 7:249–256. [CrossRef]

- Kunaver M, Jasiukaitytė E, Čuk N (2012) Ultrasonically assisted liquefaction of lignocellulosic materials. Bioresource Technology 103:360–366. [CrossRef]

- Mateus MM, Acero NF, Bordado JC, dos Santos RG (2015) Sonication as a foremost tool to improve cork liquefaction. Industrial Crops and Products 74:9–13. [CrossRef]

- Kržan A, Žagar E (2009) Microwave driven wood liquefaction with glycols. Bioresource Technology 100:3143–3146. [CrossRef]

- Xiao W, Niu W, Yi F, et al (2013) Influence of Crop Residue Types on Microwave-Assisted Liquefaction Performance and Products. Energy Fuels 27:3204–3208. [CrossRef]

- Xie J, Hse C-Y, Shupe TF, Hu T (2016) Influence of solvent type on microwave-assisted liquefaction of bamboo. Eur J Wood Prod 74:249–254. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TA, Ha TMN, Nguyen BT, et al (2023) Microwave-assisted polyol liquefication from bamboo for bio-polyurethane foams fabrication. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 11:109605. [CrossRef]

- Lu Z, Wu Z, Fan L, et al (2016) Rapid and solvent-saving liquefaction of woody biomass using microwave–ultrasonic assisted technology. Bioresource Technology 199:423–426. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Yan J, Yang Y, et al (2022) Intensification Effect of Ultrasonic-microwave on Liquefaction of Fir Sawdust. Chemistry and Industry of Forest Products 42:87–94. [CrossRef]

- Shao H, Zhao H, Xie J, et al (2019) Agricultural and Forest Residues towards Renewable Chemicals and Materials Using Microwave Liquefaction. International Journal of Polymer Science 2019:e7231263. [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan DJ, Van Vuong Q, Chalmers AC, et al (2015) Microwave-assisted extraction of Eucalyptus robusta leaf for the optimal yield of total phenolic compounds. Industrial Crops and Products 69:290–299. [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan DJ, Vuong QV, Chalmers AC, et al (2017) Development of the ultrasonic conditions as an advanced technique for extraction of phenolic compounds from Eucalyptus robusta. Separation Science and Technology 52:100–112. [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Tobón JF (2020) Recent advances and comparisons of conventional and alternative extraction techniques of phenolic compounds. J Food Sci Technol 57:4299–4315. [CrossRef]

- Gullón B, Muñiz-Mouro A, Lú-Chau TA, et al (2019) Green approaches for the extraction of antioxidants from eucalyptus leaves. Industrial Crops and Products 138:111473. [CrossRef]

- Rodsamran P, Sothornvit R (2019) Extraction of phenolic compounds from lime peel waste using ultrasonic-assisted and microwave-assisted extractions. Food Bioscience 28:66–73. [CrossRef]

- Cheng X-L, Wan J-Y, Li P, Qi L-W (2011) Ultrasonic/microwave assisted extraction and diagnostic ion filtering strategy by liquid chromatography–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry for rapid characterization of flavonoids in Spatholobus suberectus. Journal of Chromatography A 1218:5774–5786. [CrossRef]

- Walayat N, Yurdunuseven-Yıldız A, Kumar M, et al (2023) Oxidative stability, quality, and bioactive compounds of oils obtained by ultrasound and microwave-assisted oil extraction. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 0:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Wen L, Zhang Z, Sun D-W, et al (2020) Combination of emerging technologies for the extraction of bioactive compounds. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 60:1826–1841. [CrossRef]

- Mason TJ (2003) Sonochemistry and sonoprocessing: the link, the trends and (probably) the future. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 10:175–179. [CrossRef]

- Chatel G, De Oliveira Vigier K, Jérôme F (2014) Sonochemistry: What Potential for Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass into Platform Chemicals? ChemSusChem 7:2774–2787. [CrossRef]

- Sarwono A, Man Z, Muhammad N, et al (2017) A new approach of probe sonication assisted ionic liquid conversion of glucose, cellulose and biomass into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 37:310–319. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Xiao Y, Niu K, et al (2013) Functional ionic liquids for hydrolysis of lignocellulose. Carbohydrate Polymers 97:172–176. [CrossRef]

- Santos D, Silva UF, Duarte FA, et al (2018) Ultrasound-assisted acid hydrolysis of cellulose to chemical building blocks: Application to furfural synthesis. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 40:81–88. [CrossRef]

- Hernoux A, Lévêque J-M, Lassi U, et al (2013) Conversion of a non-water soluble potato starch waste into reducing sugars under non-conventional technologies. Carbohydrate Polymers 92:2065–2074. [CrossRef]

- Toukoniitty B, Kuusisto J, Mikkola J-P, et al (2005) Effect of Ultrasound on Catalytic Hydrogenation of d-Fructose to d-Mannitol. Ind Eng Chem Res 44:9370–9375. [CrossRef]

- Finch KBH, Richards RM, Richel A, et al (2012) Catalytic hydroprocessing of lignin under thermal and ultrasound conditions. Catalysis Today 196:3–10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Liu K, Wei G, et al (2022) Intensification of catalytic transfer hydrogenation of fatty acid methyl esters by using ultrasound. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 170:108645. [CrossRef]

- Mishra SP, Thirree J, Manent A-S, et al (2011) Ultrasound-catalyzed tempo-mediated oxidation of native cellulose for the production of nanocellulose: effect of process variables. 23.

- Qin Z-Y, Tong G, Chin YCF, Zhou J-C (2011) Preparation of ultrasonic-assisted high carboxylate content cellulose nanocrystals by tempo oxidation. BioResources 6:1136–1146.

- Ayoub N, Toufaily J, Guénin E, Enderlin G (2022) Catalyst-free process for oxidation of furfural to maleic acid by high frequency ultrasonic activation. Green Chem 24:4164–4173. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes A, Cruz-Lopes L, Esteves B, Evtuguin D (2023) Nanotechnology Applied to Cellulosic Materials. Materials 16:3104. [CrossRef]

- Chatel G, Valange S, Behling R, Colmenares JC (2017) A Combined Approach using Sonochemistry and Photocatalysis: How to Apply Sonophotocatalysis for Biomass Conversion? ChemCatChem 9:2615–2621. [CrossRef]

- Djellabi R, Aboagye D, Galloni MG, et al (2023) Combined conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into high-value products with ultrasonic cavitation and photocatalytic produced reactive oxygen species – A review. Bioresource Technology 368:128333. [CrossRef]

- Dhar P, Teja V, Vinu R (2020) Sonophotocatalytic degradation of lignin: Production of valuable chemicals and kinetic analysis. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 8:104286. [CrossRef]

- Asomaning J, Haupt S, Chae M, Bressler DC (2018) Recent developments in microwave-assisted thermal conversion of biomass for fuels and chemicals. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 92:642–657. [CrossRef]

| Advantage of microwave heating | |

| Non-contact heating | In microwave heating there is no physical contact between the material to be heated and the heat source. This prevents overheating of the material surfaces. |

| Lower power consumption | In conventional heating, the energy consumption is higher since part of the energy is used to heat the container. |

| Fast heating | In conventional heating, heating is slower. |

| Lower heat losses | The microwave heating container is non-conductive. |

| Shorter reaction times | In conventional heating, reaction times are longer. |

| Volumetric heating | In conventional heating, the heating is superficial. |

| Better level of control | Microwave heating can be turned off immediately. |

| Better product yield | In microwave heating, there is low formation of collateral products. |

| Allows overheating of the material | In microwave heating, the maximum temperature reached is not limited by the boiling point of the substance to be heated. |

| Improved moisture reduction | In microwave heating, moisture loss from the surface of the material first occurs. |

| Materials | Characteristics | tan | Examples |

| Conductive | They cannot be penetrated by microwaves. They reflect the microwaves. |

tan | Metals |

| Non-conductive | They are microwave transparent and have low or zero dielectric loss. They are the materials for the construction of containers for microwave heating. |

tan | Glass Teflon Ceramics Quartz Air |

| Dielectric (or absorbers) | They absorb microwaves. They are ideal to be heated by microwave |

tan | Water Methanol Carbon |

| Biomass | Dp (cm) |

Frequencies and temperature |

Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tropical wood |

2.08 | 0.1849 | 0.0954 | ---- | 8.2 to 12.4 GHz |

[32] |

| Banana fibers with polyurethane 30% | 137 | 26 | 1kHz | [33] | ||

| Empty fruit bunch (18 wt% moisture) |

6.4 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 2.45 GHz, 27 °C | [31] |

| Empty fruit bunch char |

3.5 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 2.45 GHz, 500 °C | [31] | |

| Pinewood | 2.7 | 0.53 | 59 | 2.45 GHZ, 17 °C | [30] | |

| Oil palm fiber |

1.99 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 24.8 | 2.45 GHZ, 500 °C | [28] |

| Oil palm |

2.76 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 13.4 | 2.45 GHz, 500 °C | [28] |

| Oil palm char | 2.83 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 20.6 | 2.45 GHz, 500 °C | [28] |

| Hay | 0,02 | 2.45 GHz, 700 °C | [35] |

|||

| Pinewood |

13.4 | 0.08 | 0.006 | 0.2 | 2.45 GHZ, 25 °C | [34] |

| Arabica coffee |

26.8 | 3.14 | 0.117 | 0.5 | 2.45 GHZ, 25 °C | [34] |

| Wood | 0.11 | [20] |

||||

| Fir plywood | 0.01-0.05 | [20] |

||||

| Karanja seeds | 1.3 | 1,26 | 0.1 to 3.0 GHz at room temperature | [20] |

| Solvent | tan δ | ||

| Water | 80.4 | 0.123 | 9.889 |

| Ethylene glycol | 37.0 | 6.079 | 0.161 |

| Methanol | 32.6 | 21.483 | 0.856 |

| Ethanol | 24.3 | 22.866 | 0.941 |

| Cross linkages | Types of bonds | Polymers involved |

| Intrapolymer | Ether | Lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose |

| Esther | Hemicellulose | |

| Hydrogen | Cellulose | |

| C-C | Lignin | |

| Interpolymer | Ether | Lignin-cellulose |

| Ether | Lignin-hemicellulose | |

| Esther | Lignin-hemicellulose | |

| Hydrogen | Cellulose-hemicellulose | |

| Lignin- cellulose | ||

| Lignin- hemicellulose |

| Low and medium frequency waves | High frequency waves |

|---|---|

| 20 kHz100 kHz | 3MHz10 MHz |

| Have high power | Have low power |

| Suffer cavitation | Do not suffer cavitation |

| They influence the environment in which they propagate | They do not influence the environment in which they propagate |

| Applications: Sonochemistry (Part IV- of this review) and Industry | Applications: Medical diagnostics and non-destructive control of materials (eg) |

| Biomass | Pretreatment | Operating conditions | Initial composition (%) |

Composition after treatment (%) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugarcane bagasse | Acid (H2SO4) + MW |

P= 900 W f= 2.45 GHz ∆t= 5 min T=190 °C |

C: 52.45 H: 25.97 L: 12.72 |

C: 67.31 H: 0.8 L: 15.67 |

[59] |

|

Miscanthus sinensis or Winter Wheat |

Alkaline (NH4OH) + MW |

P= 300 W ∆t=15 min T=120 °C |

C: 42.7 H: 31.3 L: 17.4 |

C: 53.1 H: 32.9 L: 12.2 |

[60] |

| Acid (H2SO4) + MW |

P= 300 W ∆t=30 min T=140 °C |

C: 42.7 H: 31.3 L: 17.4 |

C: 61.5 H: 20.7 L: 15.8 |

||

| Acid + Alkaline (H2SO4 + NH4OH) + MW |

∆t=15 min (120 °C) +∆t=30 min (140 °C) |

C: 42.7 H: 31.3 L: 17.4 |

C: 69.7 H: 18.4 L: 10.4 |

||

| Sugarcane bagasse |

US | P= 400 W f=24 kHz ∆t= 45min, T= 50 °C |

C: 38.0 H: 32.0 L: 27.0 |

C: 46.9 H: 29.3 L: 20.7 |

[61] |

| Ammonia (10% v/v) |

P= 400 W f=24 kHz ∆t= 30min, T= 80 °C |

C: 38.0 H: 32.0 L: 27.0 |

C: 50.4 H: 26.8 L: 19.8 |

||

| Ammonia +US (10% v/v) |

P= 400 W f=24 kHz ∆t= 45min, T= 80 °C |

C: 38.0 H: 32.0 L: 27.0 |

C: 56.1 H: 19.6 L: 18.2 |

||

| Hog plum (Spondias mombin L.) | US | P= 400 W f= 40 kHz ∆t= 60 min, T= 80 °C |

C: 53.74 H: 11.35 L: 35.28 |

C: 60.19 H: 6.27 L: 13.17 |

[62] |

| Nitric acid | P= 400 W f= 40 kHz ∆t= 60 min, T= 80 °C |

C: 53.74 H: 11.35 L: 35.28 |

C: 55.27 H: 9.73 L: 24.14 |

||

| Nitric acid + US |

P= 400 W f= 40 kHz ∆t= 60 min, T= 80 °C |

C: 53.74 H: 11.35 L: 35.28 |

C: 63.15 H: 3.19 L: 10.18 |

| Biomass | Pretreatment | Operating conditions | crystallinity index after (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugarcane bagasse | No treatment | 53.44 | [63] | |

| Sugarcane bagasse |

Acid (H2SO4) + MW | P= 450 W f= 2450 MHZ ∆t= 5 min |

58.79 | [63] |

| Alkaline (NaOH) + MW | P= 450 W f= 2450 MHZ ∆t= 5 min |

65.29 | ||

| Alkaline (NaOH) + Acid (H2SO4) + MW | P= 450 W f= 2450 MHZ ∆t= 10 min |

65.55 | ||

| Water hyacinth |

No treatment | 16.0 | [64] |

|

| Alkaline (NaOH) + MW | P = N.d.3 ∆t = 10 min T= 190 °C |

13.0 | ||

| Hemp stalk |

No treatment | 44.96 | [57] |

|

| With MEP1 | P= 1100 W ∆t = 3 min T= 90 °C |

42.83 |

||

| Black tea residues (Camellia sinensis) |

No treatment | 56.86 | [65] |

|

| Alkaline bleaching with peroxide | P= 1000 W ∆t = 90 min T= 55 °C |

76.86 | ||

| Alkaline bleaching with peroxide +MW2 | P= 1000 W ∆t = 0.5 min |

88.77 |

| Pretreatment | Operating conditions |

Increase in soluble organic matter |

Increase in soluble proteins |

Increase in soluble carbohydrates |

Increase in soluble lipids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW | P= 900 W f= 2450 MHz ∆t= 3 min |

8× |

18× |

12× |

2× |

| US | P=70 W f= 20 kHz ∆t= 30 min |

7× |

12× |

9× |

3× |

| Biomass | Pretreatment | Operating conditions |

Increased sCOD1 efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraselmis suecica | US | P= 500 W f= 20 kHz ∆t = 5 s T= 19.1 °C |

5.13 |

| Nannochloropsis oceanica | US | P= 500 W f= 20 kHz ∆t = 54 s T= 21.6 °C |

18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).