Submitted:

19 October 2023

Posted:

20 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

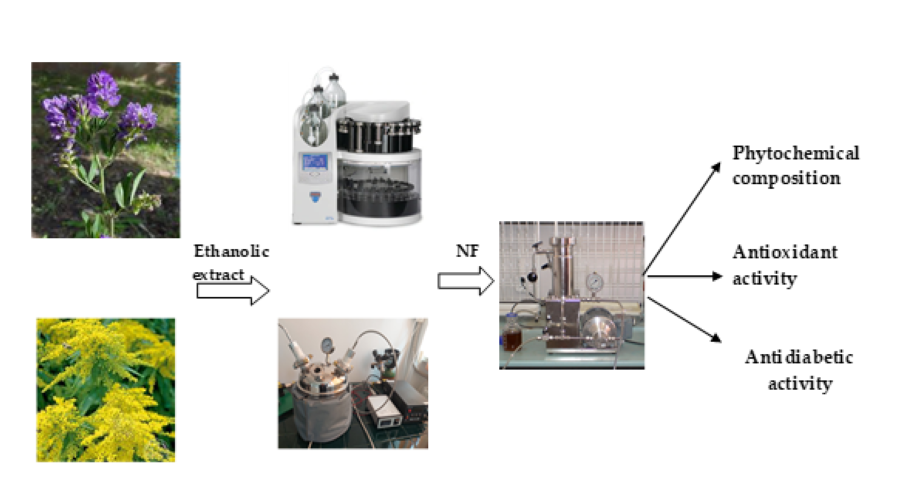

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Extracts Preparation

2.2.1. ASE Extraction

2.2.2. Laser Irradiation Extraction

2.3. Analysis of Flavonoids and Isoflavonoids

2.3.1. Quantification of Total Flavonoids

2.3.2. HPLC-MS Analysis

2.4. Antioxidant Assays

2.4.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging

2.4.2. Fe (III) Reducing Power Assay

2.5. Antidiabetic Assay

2.5.1. α-. Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities

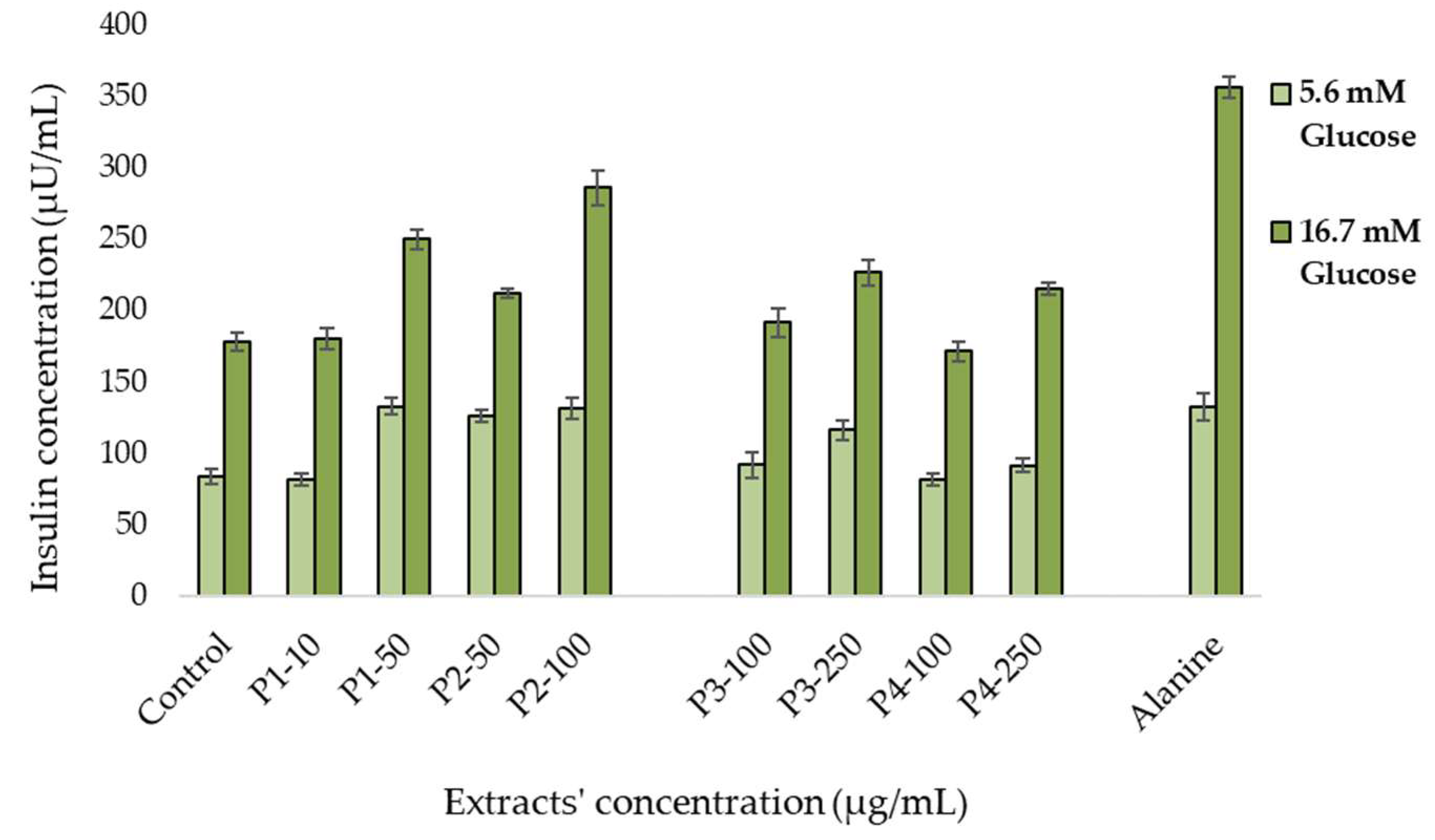

2.5.2. In Vitro Insulin Secretion Assay

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

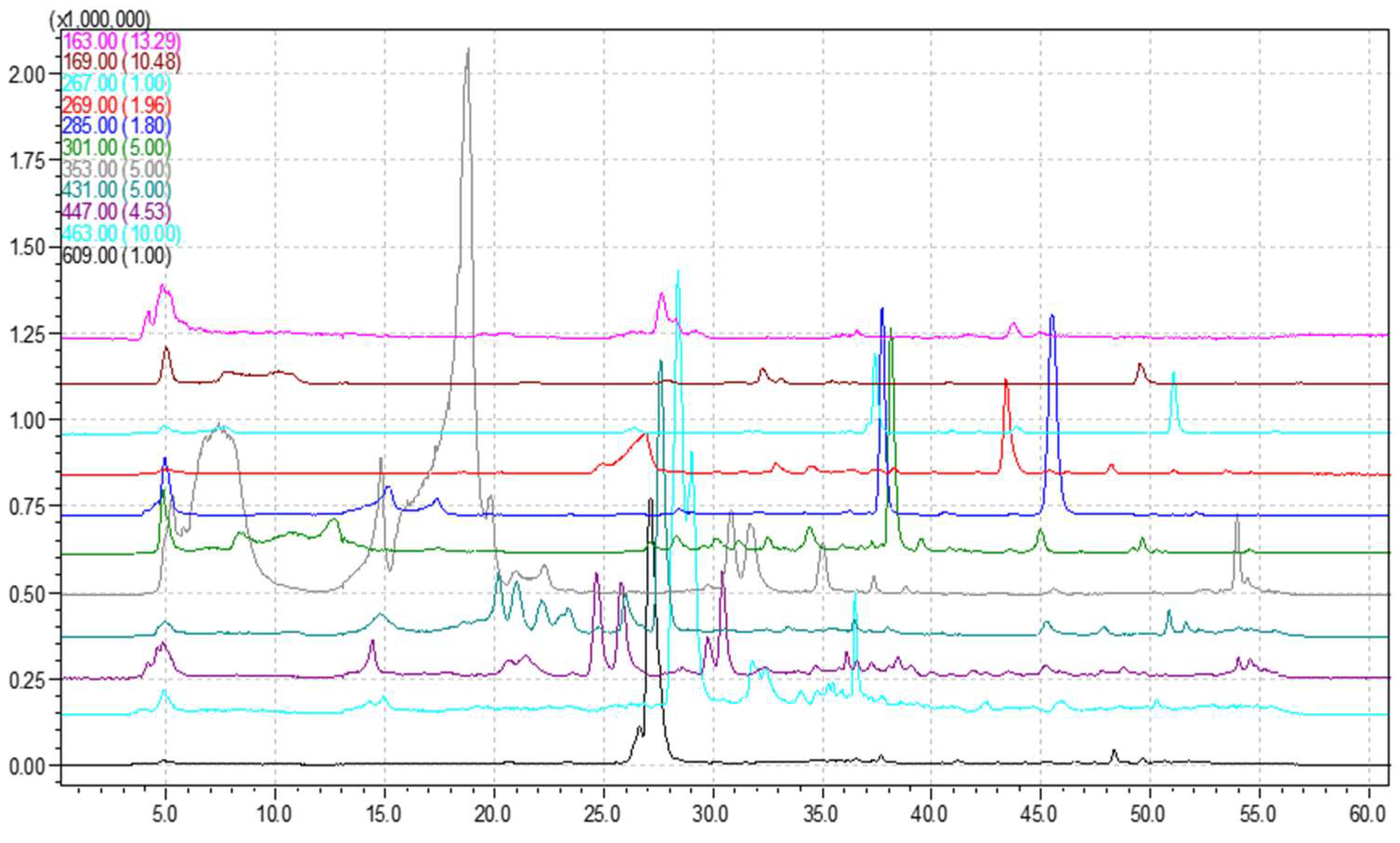

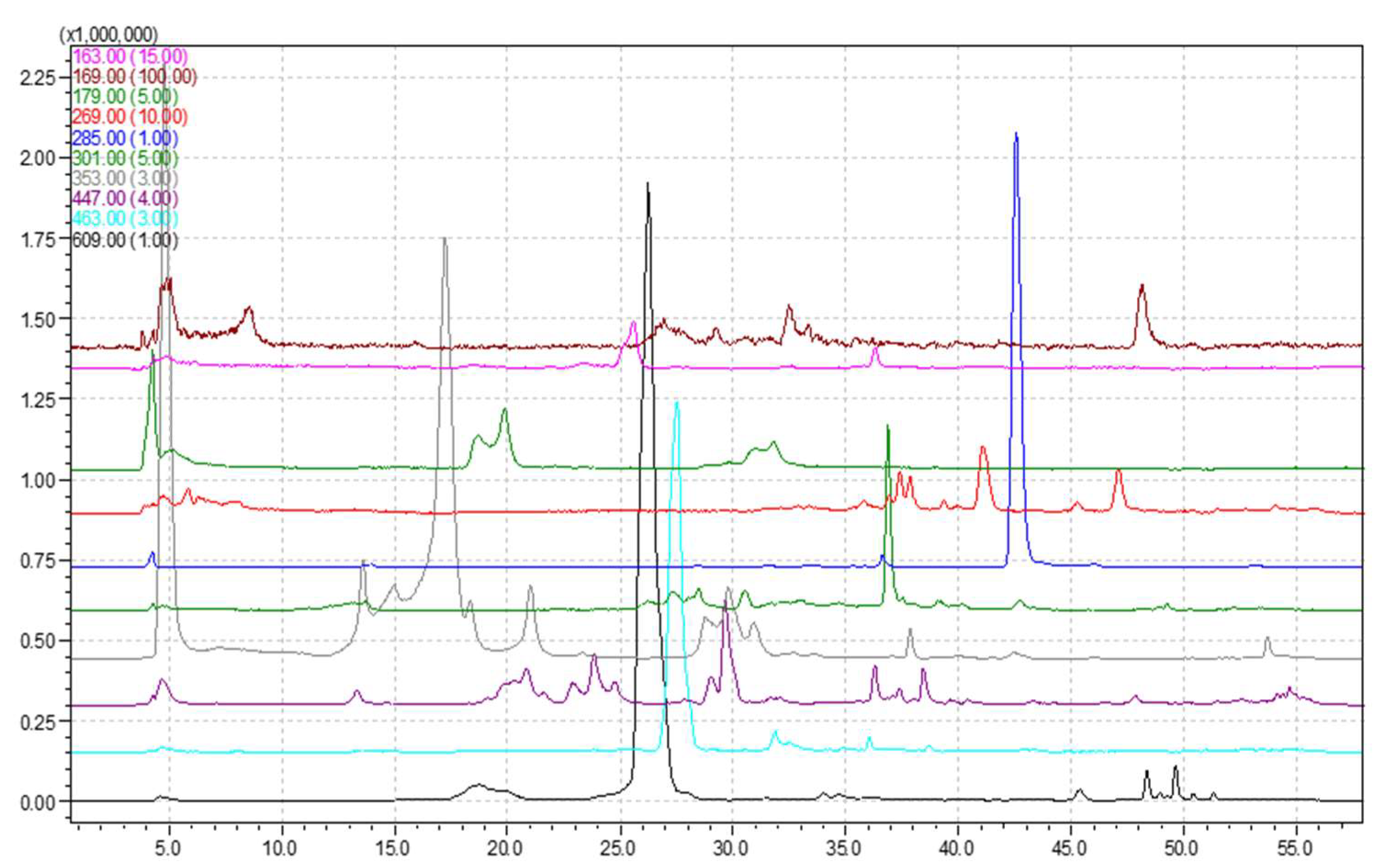

3.1. HPLC-MS Analysis

3.2. Total Antioxidant Activity

3.3. Antidiabetic Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedman, M. Overview of antibacterial, antitoxin, antiviral, and antifungal activities of tea flavonoids and teas. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushnie, T.P.; Lamb, A.J. Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, D.C.; Piazza, C.; Melilli, B.; Drago, F.; Salomone, S. Isoflavones: Estrogenic Activity, Biological Effect and Bioavailability. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 38, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Vaquero, M.; Ravindran, R.; Walsh, O.; O’Doherty, J.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Tiwari, B.K.; Rajauria, G. Evaluation of Ultrasound, Microwave, Ultrasound–Microwave, Hydrothermal and High Pressure Assisted Extraction Technologies for the Recovery of Phytochemicals and Antioxidants from Brown Macroalgae. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D. T. V., Zabot, G. L., Reyes, F. G. R., Iglesias, A. H., Martínez, J. Integration of pressurized liquids and ultrasound in the extraction of bioactive compounds from passion fruit rinds: Impact on phenolic yield, extraction kinetics and technical-economic evaluation. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 67, 102549. 1025.

- Mihelčič, A.; Lisjak, K.; Vanzo, A. Accelerated solvent extraction of phenols from lyophilised ground grape skins and seeds. Beverages 2023, 9(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khongthaw, B.; Chauhan, P. K.; Dulta, K.; Kumar, V.; Ighalo, J. O. A comparison of conventional and novel phytonutrient extraction techniques from various sources and their potential applications. J.Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17(2), 1317–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwal, T.; Ezzat, S.M.; Rastrelli, L.; Bhatt, I.D.; Daglia, M.; Baldi, A.; Devkota, H.P.; Orhan, I.E.; Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; et al. A critical analysis of extraction techniques used for botanicals: Trends, priorities, industrial uses and optimization strategies. Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 100, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabias-Martínez, R.; Rodríguez-Gonzalo, E.; Revilla-Ruiz, P.; Hernández-Méndez, J. Pressurized liquid extraction in the analysis of food and biological samples. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1089(1-2), 1-17.

- Nieto, A.; Borrull, F.; Pocurull, E.; Marcé, R. M. Pressurized liquid extraction: A useful technique to extract pharmaceuticals and personal-care products from sewage sludge. TrAC - Trends Anal. Chem. 2010, 29(7), 752-764.

- Perra, M.; Leyva-Jiménez, F. -.; Manca, M. L.; Manconi, M.; …., Lozano-Sánchez, J. Application of pressurized liquid extraction to grape by-products as a circular economy model to provide phenolic compounds enriched ingredient. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402; [CrossRef]

- Pirvu, L. C.; Nita, S.; Rusu, N.; Bazdoaca, C.; Neagu, G.; … . . . Enache, A. Effects of laser irradiation at 488, 514, 532, 552, 660, and 785 nm on the aqueous extracts of plantago lanceolata L.: A comparison on chemical content, antioxidant activity and caco-2 viability. Appl. Sci. (Switzerland) 2022, 12(11). [CrossRef]

- Wyse, J. M.; Latif, S.; Gurusinghe, S.; Berntsen, E. D.; Weston, L. A.; Stephen, C. P. Characterization of phytoestrogens in medicago sativa l. and grazing beef cattle. Metabolites 2021, 11(8). [CrossRef]

- Bajkacz, S.; Baranowska, I.; Buszewski, B.; Kowalski, B.; Ligor, M. Determination of flavonoids and phenolic acids in plant materials using SLE-SPE-UHPLC-MS/MS method. Food Anal. Method. 2018, 11(12), 3563–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, K. S.; Sharma, A. Phytochemical and pharmacological potential of medicago sativa: A review. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49(2), 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. I.; Mosbach, E. H.; Matoba, N.; Suh, S. O.; McSherry, C. K. The effect of alfalfa-corn diets on cholesterol metabolism and gallstones in prairie dogs. Lipids 1990, 25, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaweł, E.; Grzelak, M.; Janyszek, M. Lucerne (medicago sativa L.) in the human diet—Case reports and short reports. J. Herb. Med. 2017, 10, 8-16.

- Dutu, L. E.; Istudor, V.; Loloiu, T.; Radulescu, V. Research on polyphenolic compounds from Medicago sativa L. Farmacia 2002, 50, 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mansourzadeh, S.; Esmaeili, F.; Shabani, L.; Gharibi, S. Trans-differentiation of mouse mesenchymal stem cells into pancreatic β-like cells by a traditional anti-diabetic medicinal herb medicago sativa L. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2022, 12(5), 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eruygur, N.; Dincel, B.; Kutuk Dincel, N.; Ucar, E. Comparative study of in vitro antioxidant, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activity of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) collected during different growth stages. Open Chem. 2018, 16 (1), 963-967.

- Abdel Motaal, A.; Ezzat, S.M.; Tadros, M.G.; El-Askary, H.I. In vivo anti-inflammatory activity of caffeoylquinic acid derivatives from Solidago virgaurea in rats. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 2864–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borchert, V.E.; Czyborra, P.; Fetscher, C.; Goepel, M.; Michel, M.C. Extracts from Rhois aromatica and Solidaginis virgaurea inhibit rat and human bladder contraction. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2004, 369, 281–286.

- Jasicka-Misiak, I.; Makowicz, E.; Stanek, N. Chromatographic fingerprint, antioxidant activity, and colour characteristic of polish woundwort (Solidago virgaurea L.) honey and flower. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tămaş, M.; Vostinaru, O.; Soran, L.; Lung, I.; Opris, O.; Toiu, A.; Mogosan, C. Antihyperuricemic, anti--inflammatory and antihypertensive effect of a dry extract from solidago virgaurea l. (asteraceae). Sci. Pharm. 2021, 89(2). [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-Y.; Tang, C.-Y. Determination of total phenolic and flavonoid contents in selected fruits and vegetables, as well as their stimulatory effects on mouse splenocyte proliferation. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, E.; Paun, G.; Albu, C.; Eremia, S.A.-M.V.; Radu, G.L. Artemisia abrotanum and Symphytum officinale Polyphenolic Compounds-Rich Extracts with Potential Application in Diabetes Management. Metabolites 2023, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, V.; Deliu, C.; Oltean, B.; Butiuc-Keul, A.; Brummer, A.; Albu, C.; Radu, G.L. Soilless Cultures for Pharmaceutical Use and Biodiversity Conservation. Acta Hortic. 2009, 843, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondet, V.; Brand-Williams, W.; Berset, C. Kinetics and mechanism of antioxidant activity using the DPPH free radical method. Leb. Wiss Technol. 1997, 30, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berker, K.; Guclu, K.; Tor, I.; Apak, R. Comparative evaluation of Fe (III) reducing power-based antioxidant capacity assays in the presence of phenanthroline, batho-phenanthroline, tripyridyltriazine (FRAP) and ferricyanide reagents. Talanta 2007, 72, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, E.; Paun, G.; Albu, C.; Eremia, S.A.-M.V.; Radu, G.L. Artemisia abrotanum and Symphytum officinale Polyphenolic Compounds-Rich Extracts with Potential Application in Diabetes Management. Metabolites 2023, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranilla, L.G.; Kwon, Y.I.; Apostolidis,E.; Shetty,K. Phenolic compounds antioxidant activity and in vitro inhibitory potential against key enzymes relevant for hyperglycemia and hypertension of commonly used medicinal plants, herbs and spices in Latin America. Biores.Technol. 2010,101, 4676–4689.

- Paun, G.; Neagu, E.; Tache, A.; Radu, G.L.; Parvulescu, V. Application of nanofiltration process for concentration of polyphenolic compounds from Geranium robertianum and Salvia officinalis extracts. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2011, 25(4), 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tucak, M.; Čupić, T.; Horvat, D.; Popović, S.; Krizmanić, G.; Ravlić, M. Variation of phytoestrogen content and major agronomic traits in alfalfa (medicago sativa l.) populations. Agronomy 2020, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, E. R.; Chiţescu, C. L.; Sandru, C.; Geană, E. -.; ….; Boscencu, R. Comparative study of the bioactive properties and elemental composition of red clover (trifolium pratense) and alfalfa (medicago sativa) sprouts during germination. Appl. Sci. (Switzerland) 2020, 10(20), 1-14.

- Raeeszadeh, M.; Moradi, M.; Ayar, P.; Akbari, A. The Antioxidant Effect of Medicago sativa L. (Alfalfa) Ethanolic Extract against Mercury Chloride (HgCl2) Toxicity in Rat Liver and Kidney: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 8388002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Ziemlewska, A.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z.; Bujak T. Antioxidant Activity and Cytotoxicity of Medicago sativa L. Seeds and Herb Extract on Skin Cells. Biores. Open Access. 2020, 23, 9(1), 229-242. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apáti, P.; Szentmihályi, K.; Kristó, S. T.; Papp, I.; Vinkler, P.; Szoke, E.; Kéry, A. Herbal remedies of Solidago correlation of phytochemical characteristics and antioxidative properties. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2003, 32, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, H.; Acik, L.; Bali, E. B.; Koç, L. Y.; Kaynak, G. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Solidago virgaurea extracts. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, M. D. S.; Ranilla, L.G.; Apostolidis, E.; Lajolo, F. M.; Genovese, M.I.; Shetty, K. Evaluation of anti-hyperglycemia and anti-hypertension potential of native Peruvian fruits using in vitro models. J Med. Food. 2009; 12, 278–291.

- Hanhineva, K.; Törrönen, R.; Bondia-Pons, I.; Pekkinen, J.; Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkänen, H.; Poutanen, K. Impact of Dietary Polyphenols on Carbohydrate Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1365–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.T.; Yin, Y.C.; Xing, S.; Li, W.N.; Fu, X. Q. Hypoglycemic effect and mechanism of isoquercitrin as an inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 in type 2 diabetic mice. RSC Adv. 2018, 19, 8(27), 14967-14974. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, J. C.; Peng, R. Y.; Chen, Y. T.; Xu, H. X.; Zhang, Q. F. In vitro and in vivo Inhibitory Activity of C-glycoside Flavonoid Extracts from Mung Bean Coat on Pancreatic Lipase and α-glucosidase. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2023, 78, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, S. A.; Bhattarai, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Parveen, Z.; Sajid, M.; Zhu, L. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the antidiabetic activity of solidago virgaurea extracts. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2023, 19(4), 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fursenco, C.; Calalb, T.; Uncu, L.; Dinu, M.; Ancuceanu, R. Solidago virgaurea L.: A Review of its ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakupović, L.; Kalvarešin, M.; Bukovina, K.; Poljak, V.; Vujić, L.; Zovko Končić, M. Optimization of Two Eco-Friendly Extractions of Black Medick (Medicago lupulina L.) Phenols and Their Antioxidant, Cosmeceutical, α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase Inhibitory Properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound |

M. sativa flavonoid- and isoflavonoid-rich extract (µg/mL) |

S. virgaurea flavonoid- and isoflavonoid-rich extract (mg/mL) |

||

| Conc. ASE | Conc. LE | Conc. ASE | Conc. LE | |

| Rutin | 157.16±9.6 | 58.48±4.8 | 2024.05±108.9 | 1652.05±99.7 |

| Luteolin | 10.43±1.2 | 8.43±0.7 | 2.13±0.2 | 2.88±0.2 |

| Quercitrin | 5.71±0.5 | 6.02±0.5 | 21.90±1.8 | 22.62±2.1 |

| Quercetin 3-β-D-glucoside | 23.04±2.2 | 73.07±6.2 | 175.14±11.6 | 183.11±12.9 |

| Quercetin | 1.10±0.1 | 10.69±0.9 | 2.48±0.1 | 17.09±1.4 |

| Kaempferol | 10.20±0.9 | 19.38±1.4 | 52.05±4.2 | 58.35±5.1 |

| Isorhamnetin | 1.29±0.1 | 0.47±0.04 | 6.52±0.5 | 3.59±0.3 |

| Daidzein | 2.47±0.2 | 1.65±0.1 | - | - |

| Formononetin | 4.13±0.3 | 2.72±0.2 | 0.55±0.04 | 0.30±0.02 |

| Genistein | 8.35±0.6 | 3.76±0.2 | 2.21±0.1 | 0.63±0.05 |

| Naringenin | 0.05±0.01 | 0.12±0.01 | 0.47±0.03 | 0.68±0.04 |

| Biochanin A | 0.25±0.02 | 0.36±0.02 | 0.61±0.03 | 0.67±0.03 |

| Vitexin | 7.00±0.5 | 65.30±4.9 | 126.58±8.9 | 158.15±11.8 |

| Total | 231.18±1.2 | 250.45±1.7 | 2414.69±10.5 | 2100.12±10.3 |

| Sample | Total flavonoid content, mg RE/mL |

DPPH | Fe(III) reducing power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50, µg/mL | ||||

| M. sativa | Conc. ASE | 355.43±8.4 | 278.7±2.5 | 42.29±0.3 |

| Conc. LE | 426.70±11.2 | 105.2±1.1 | 40.98±0.2 | |

| S. virgaurea | Conc. ASE | 1398.74±15.6 | 381.3±2.9 | 58.67±0.3 |

| Conc. LE | 1382.56±13.8 | 198.4±1.6 | 56.92±0.4 | |

| Ascorbic acid | 39.4±0.1 | 125±1.1 | ||

| Sample | α-amylase inhibition | α−glucosidase inhibition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (µg/mL) | |||

| M. sativa | Conc. ASE | 23.9±1.2 | 24.2±0.9 |

| Conc. LE | 26.8±1.1 | 25.7±1.1 | |

| S. virgaurea | Conc. ASE | 33.9±2.4 | 9.3±0.9 |

| Conc. LE | 32.1±1.9 | 8.7±0.6 | |

| Acarbose | 24.2±1.6 | 66.5±4.2 | |

| Rutin | 18.2±2.4 | 8.6±0.7 | |

| Pearson correlation coefficient (r) | Significance (p < 0.05) | |

|---|---|---|

| TFC | TFC | |

| DPPH | 0.758 | 0.04657 |

| RP | 0.877 | 0.02995 |

| α-AMYL | 0.967 | 0.02871 |

| α-GLUC | -0.976 | 0.02925 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).