Submitted:

17 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

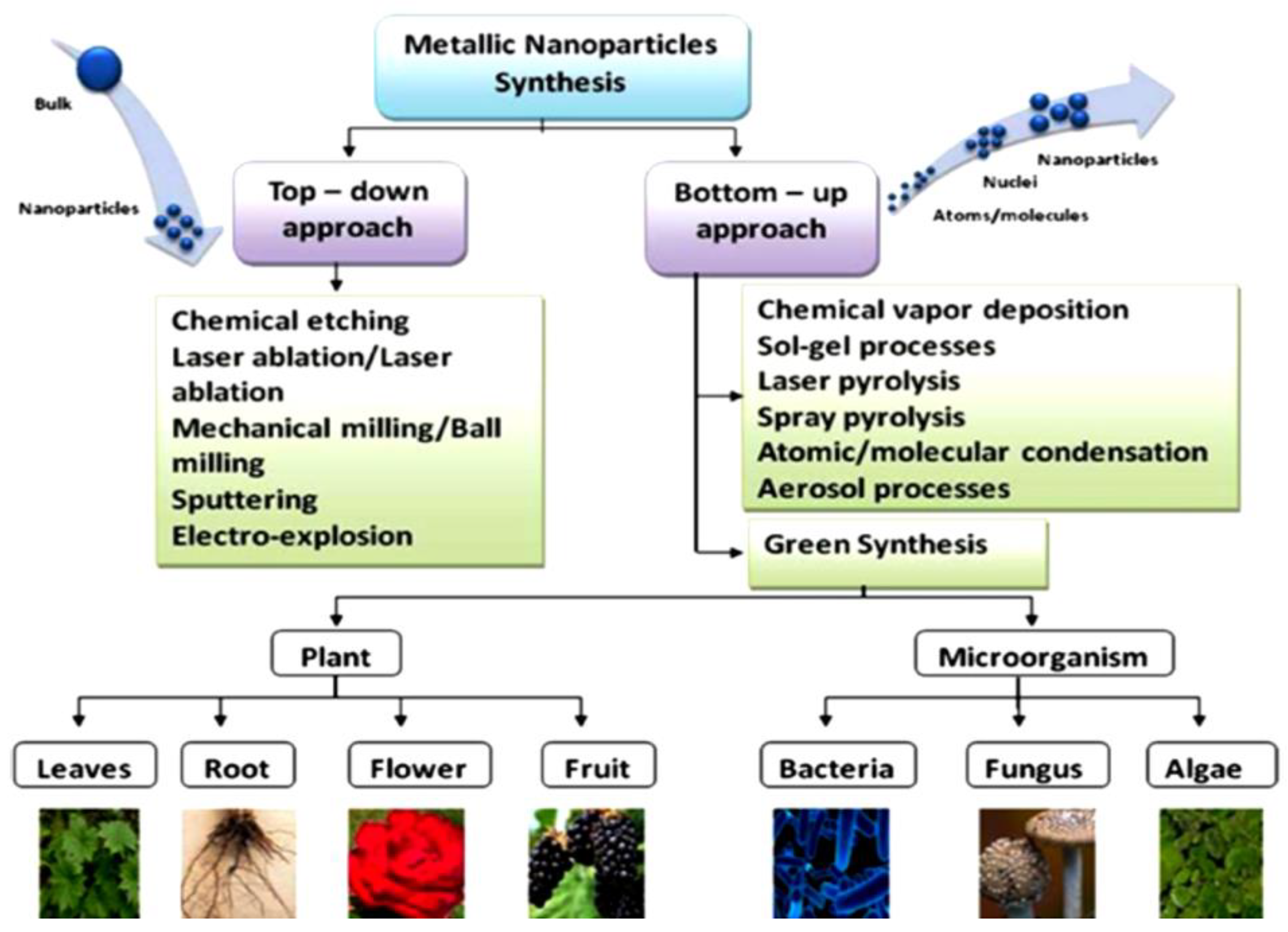

1. Introduction

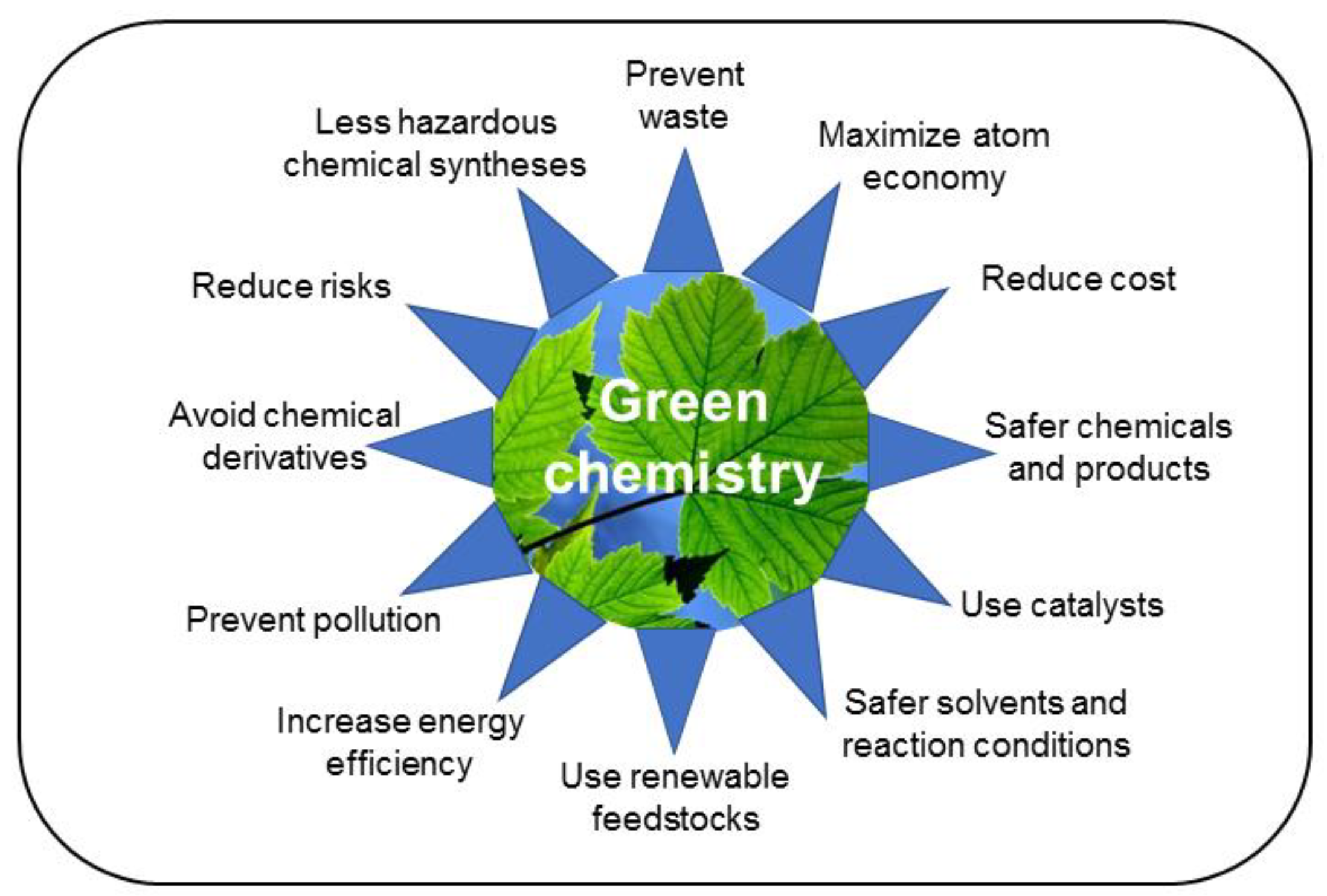

2. Green Synthesis

2.1. Green Synthesis of NPs from Biogenic Wastes

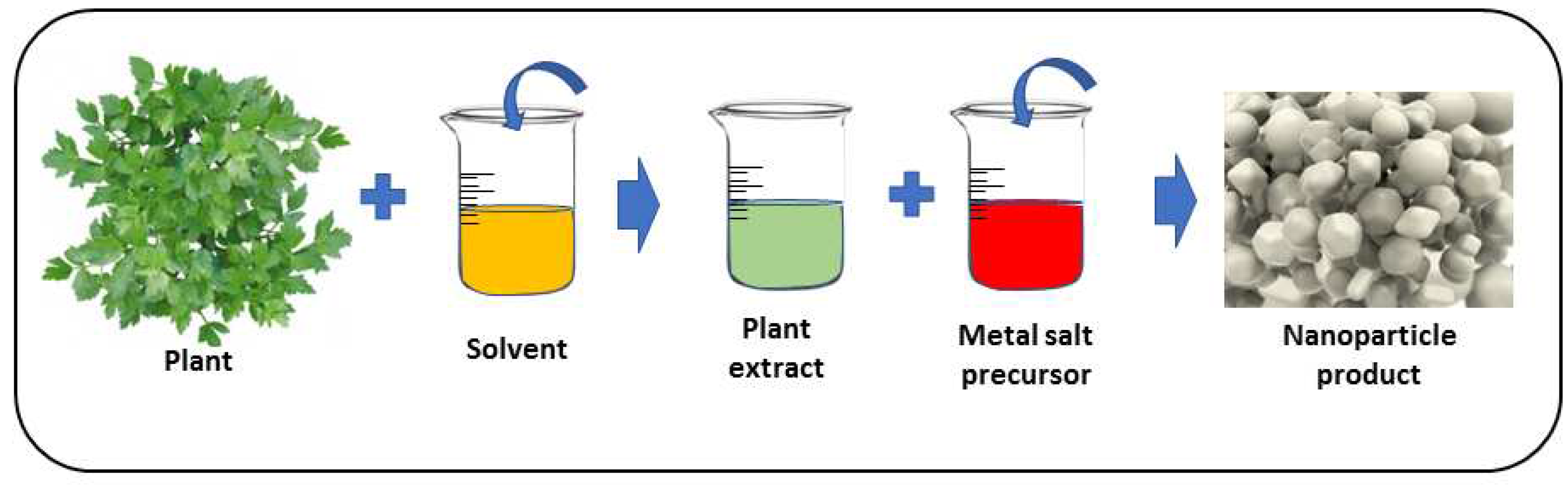

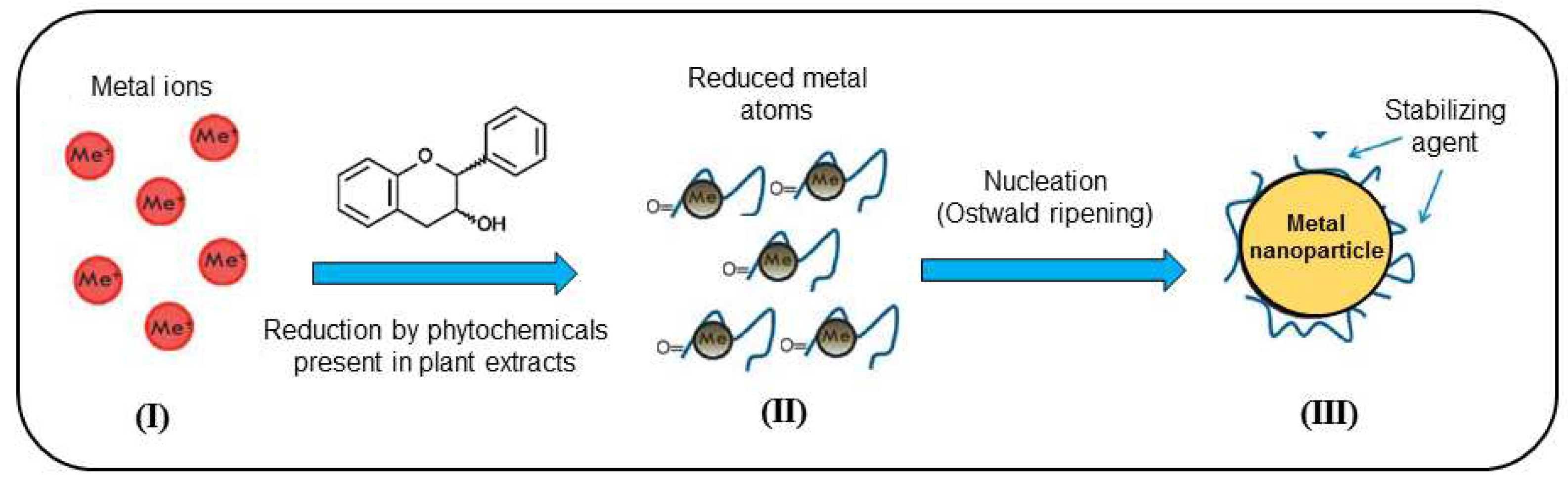

2.2. Green Synthesis of NPs from Plant Extracts

3. Metal and Metal Oxide-Based Nanoparticles

4. Mn-Oxides NPs

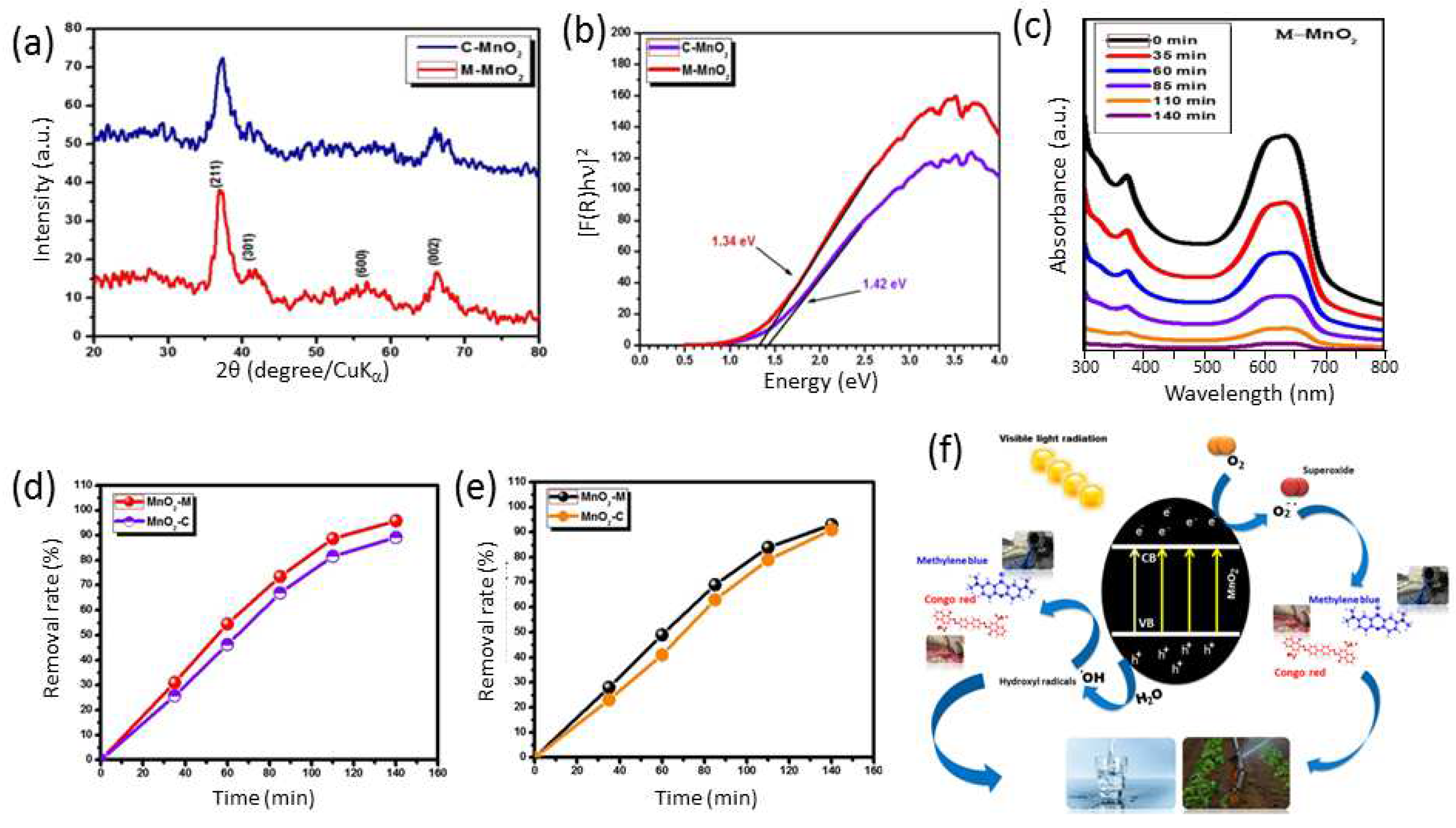

4.1. MnO2 NPs

4.2. Crystal Structure of MnO2 NPs

5. Synthesis of Nanostructured MnO2

5.1. Traditional Synthesis of MnO2 NPs

5.2. Green Synthesis of MnO2 NPs

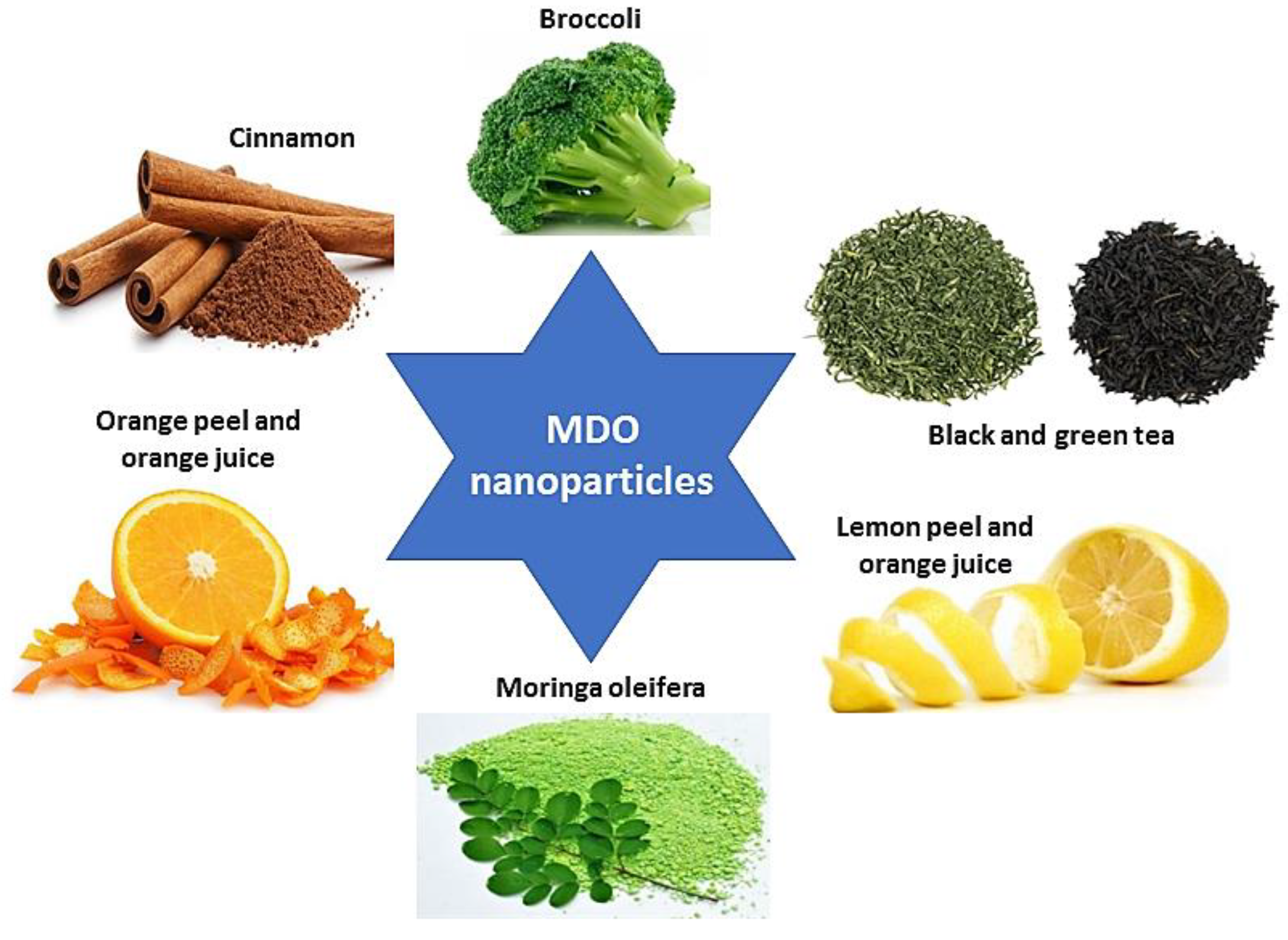

6. Plant Extracts for Green Synthesized MnO2 NPs and Recent Applications

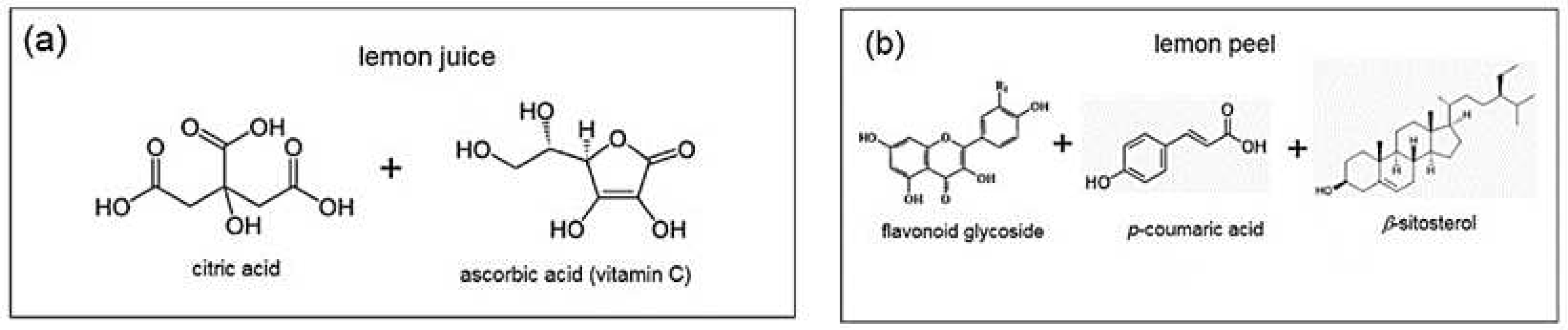

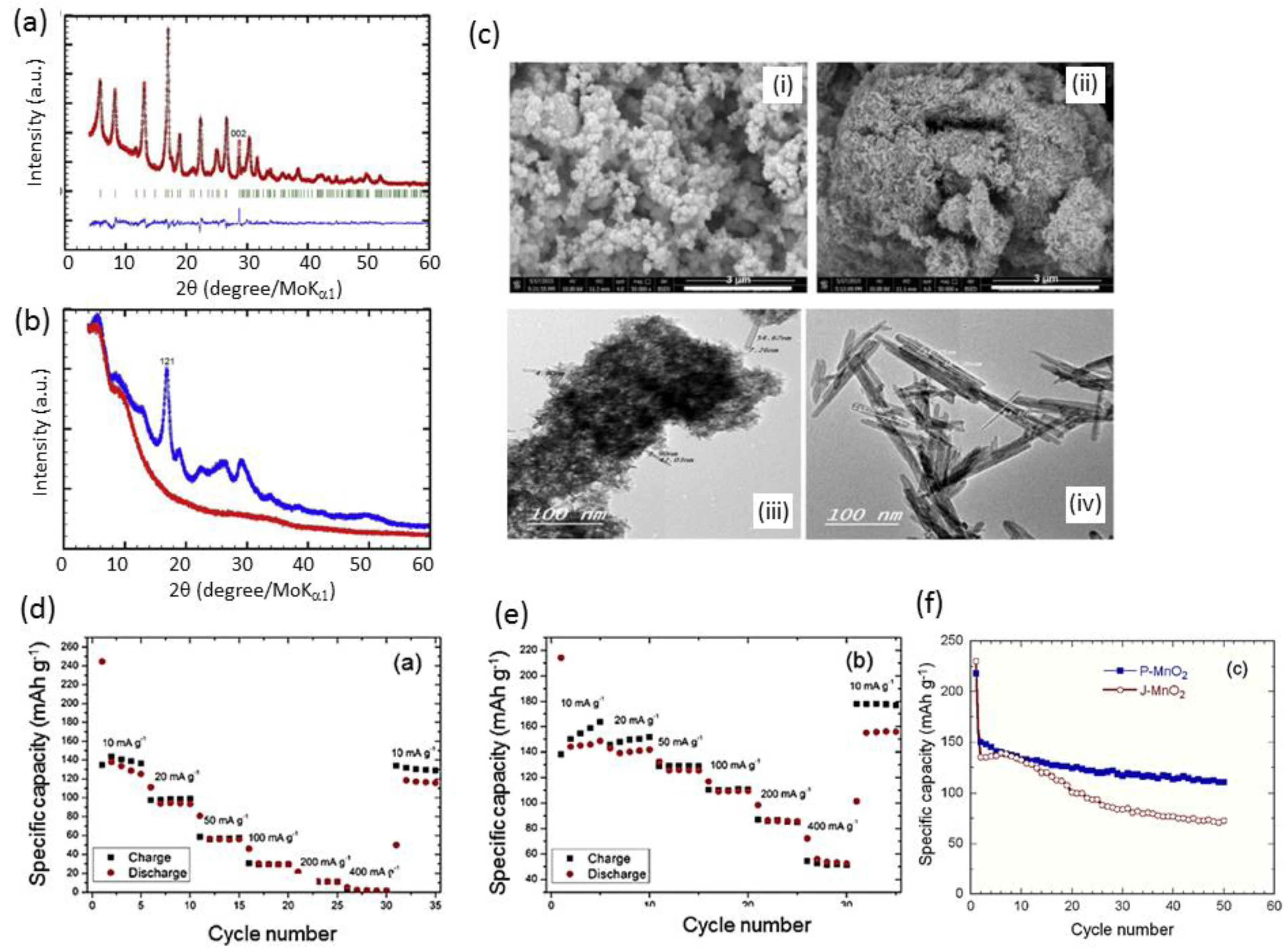

6.1. Lemon Juice and Lemon Peel Extracts

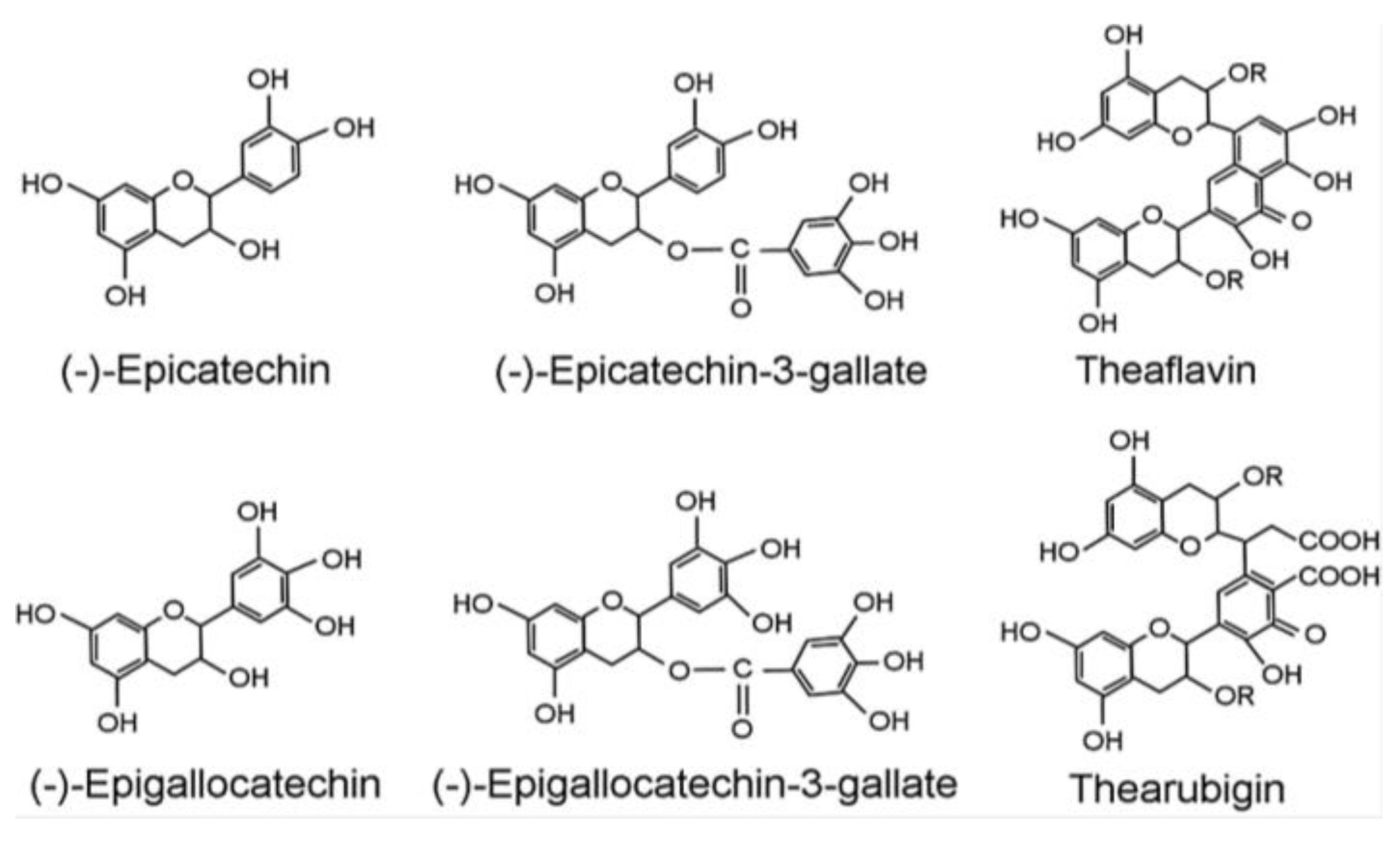

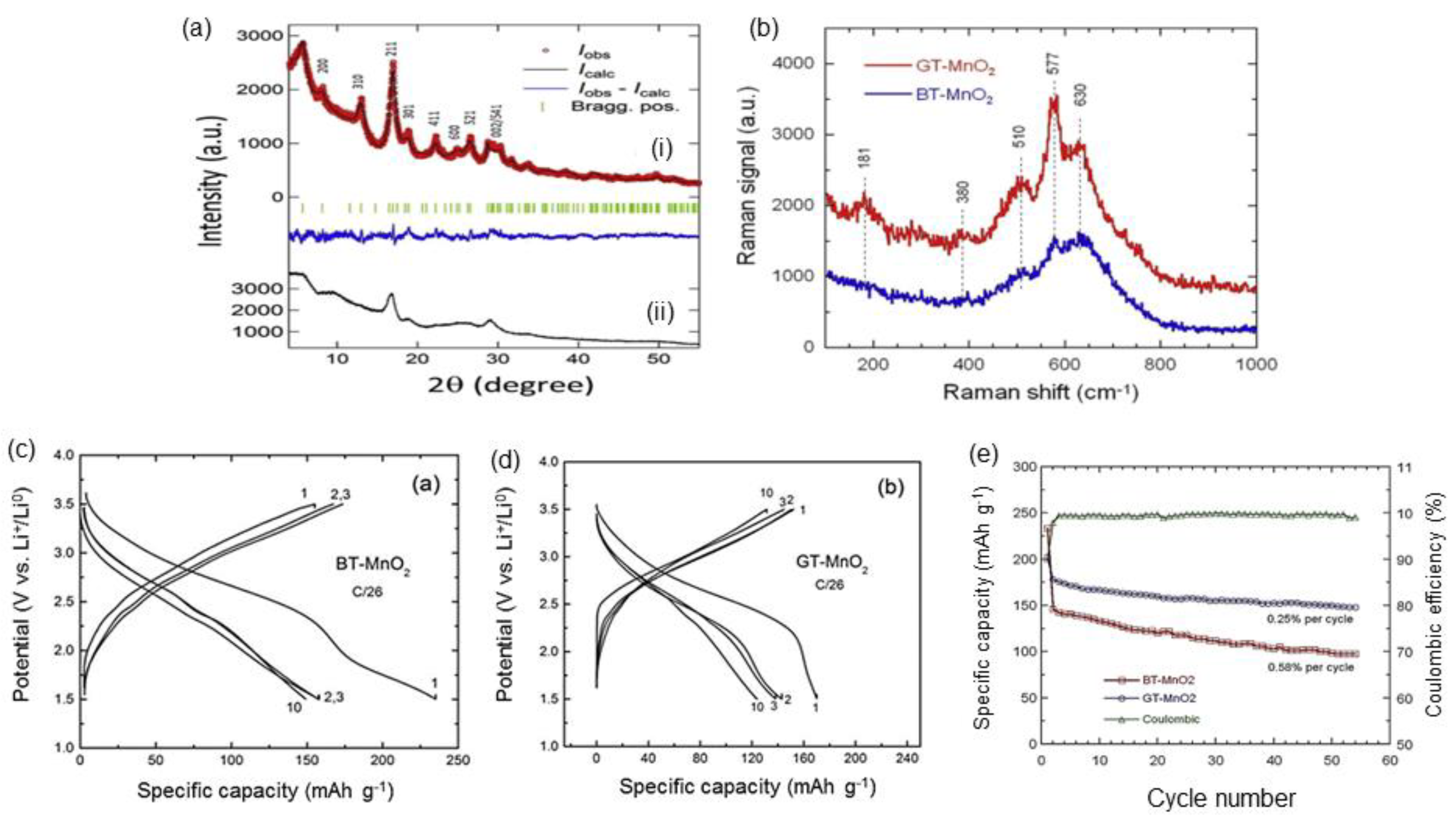

6.2. Black and Green Tea Extracts

6.3. Broccoli Vegetable Extract

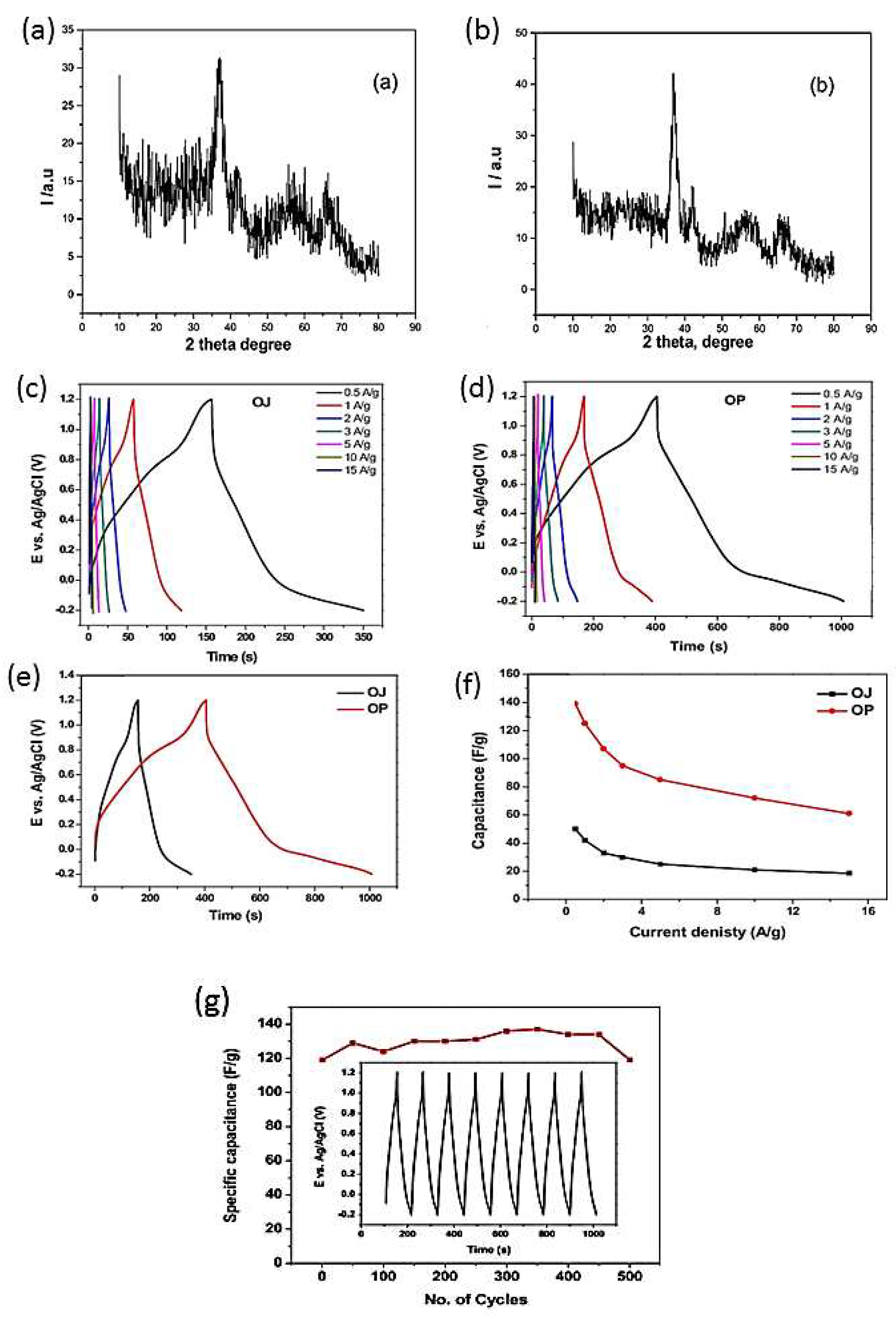

6.4. Orange Juice and Orange Peel Extracts

6.5. Moringa and Cinnamon Herbs Extracts

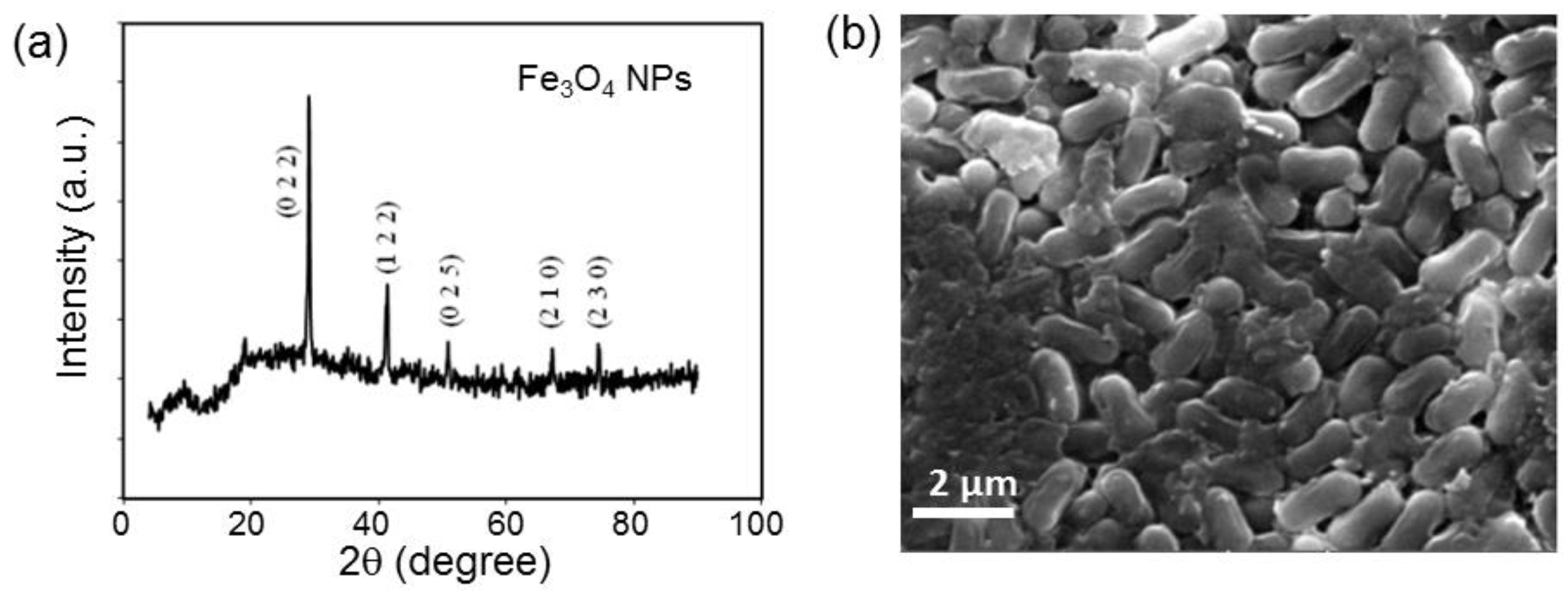

7. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

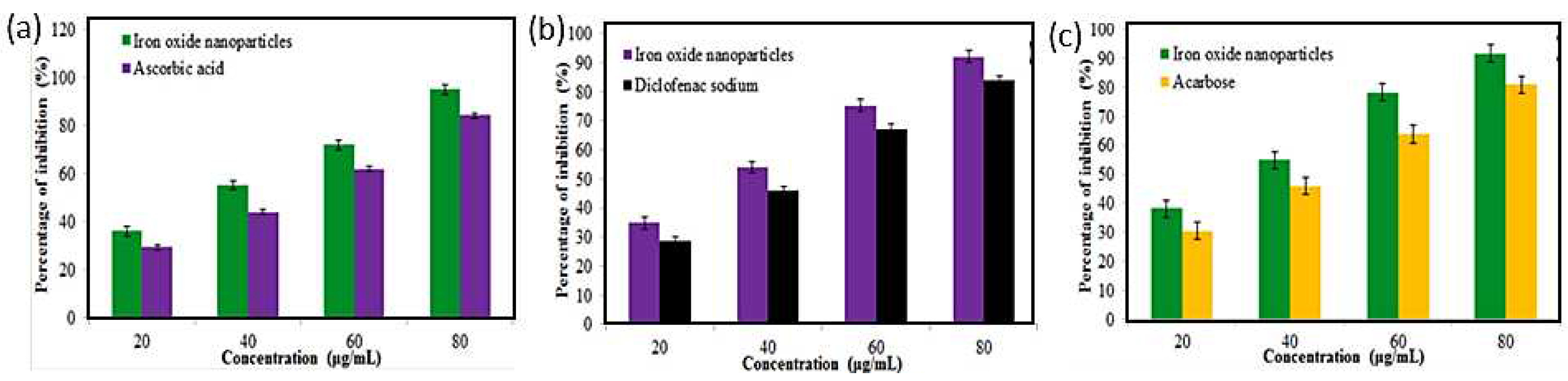

7.1. Iron Oxide NPs Applications

7.1.1. Antioxidant Activity

7.1.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

7.1.3. Anti-Diabetic Activity

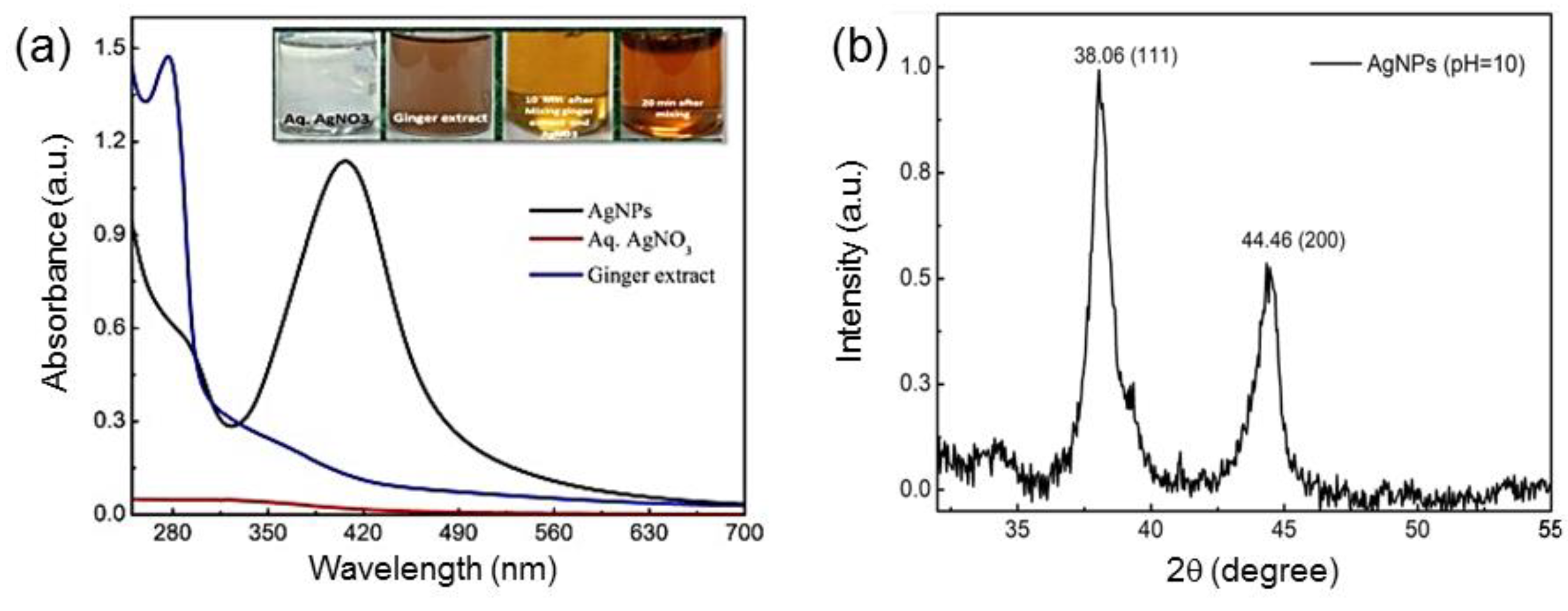

8. Silver Nanoparticles

8.1. Ag NPs Applications

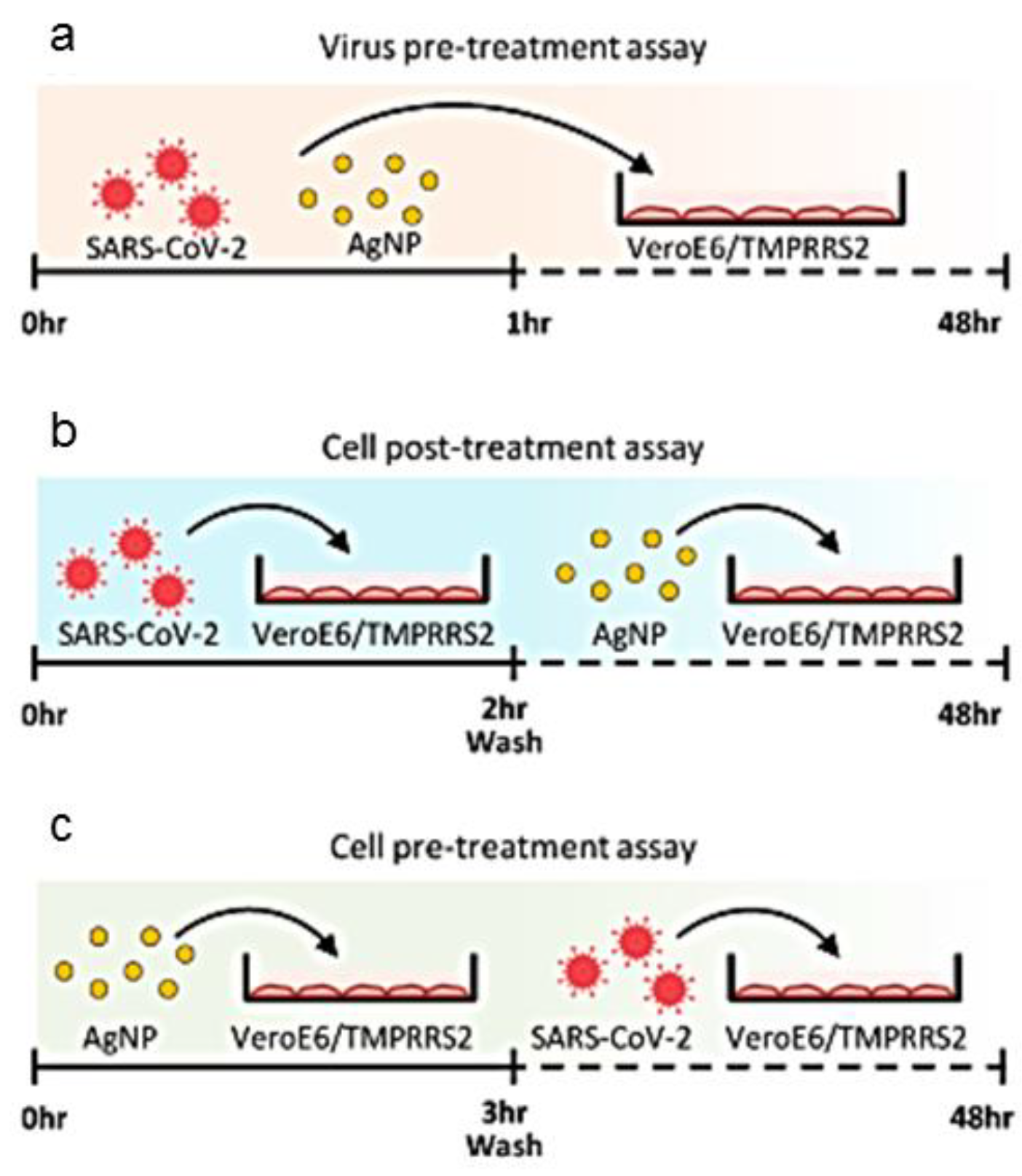

8.2. Antiviral Activity

9. Gold Nanoparticles

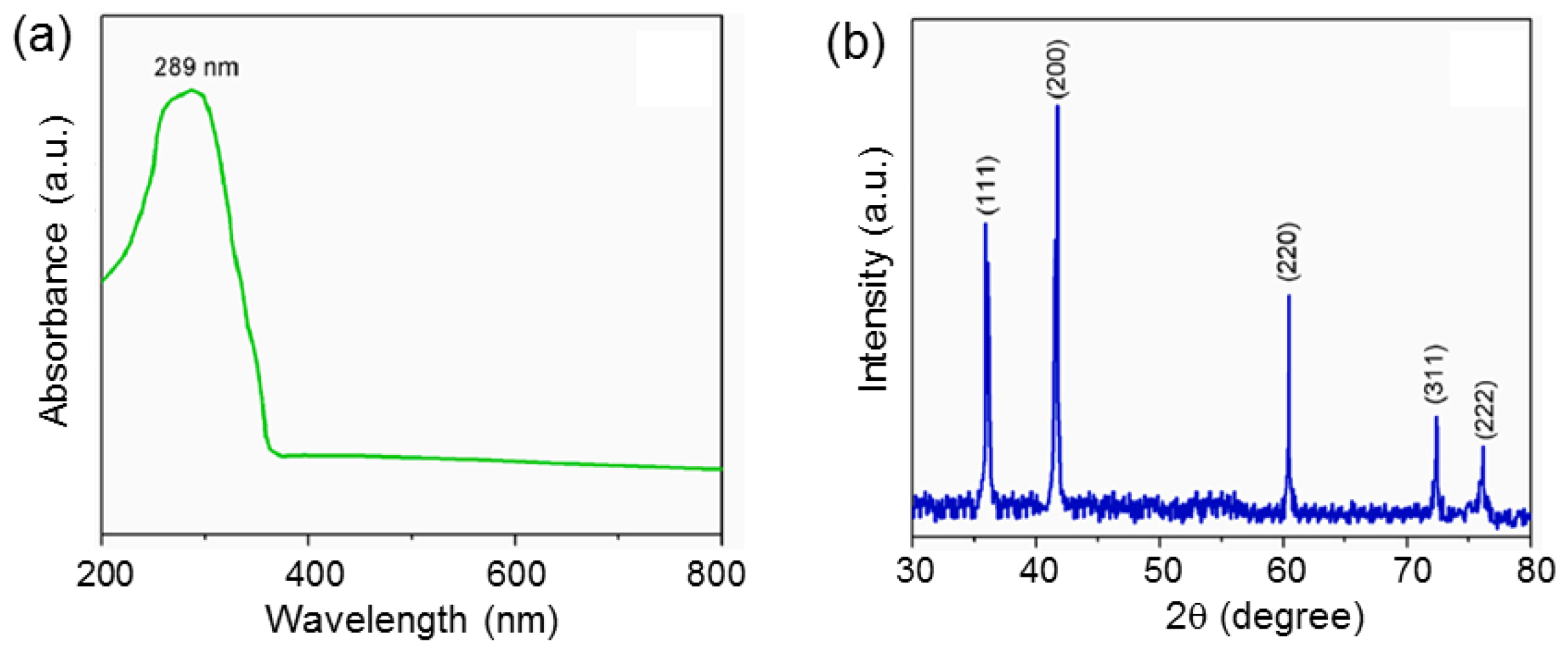

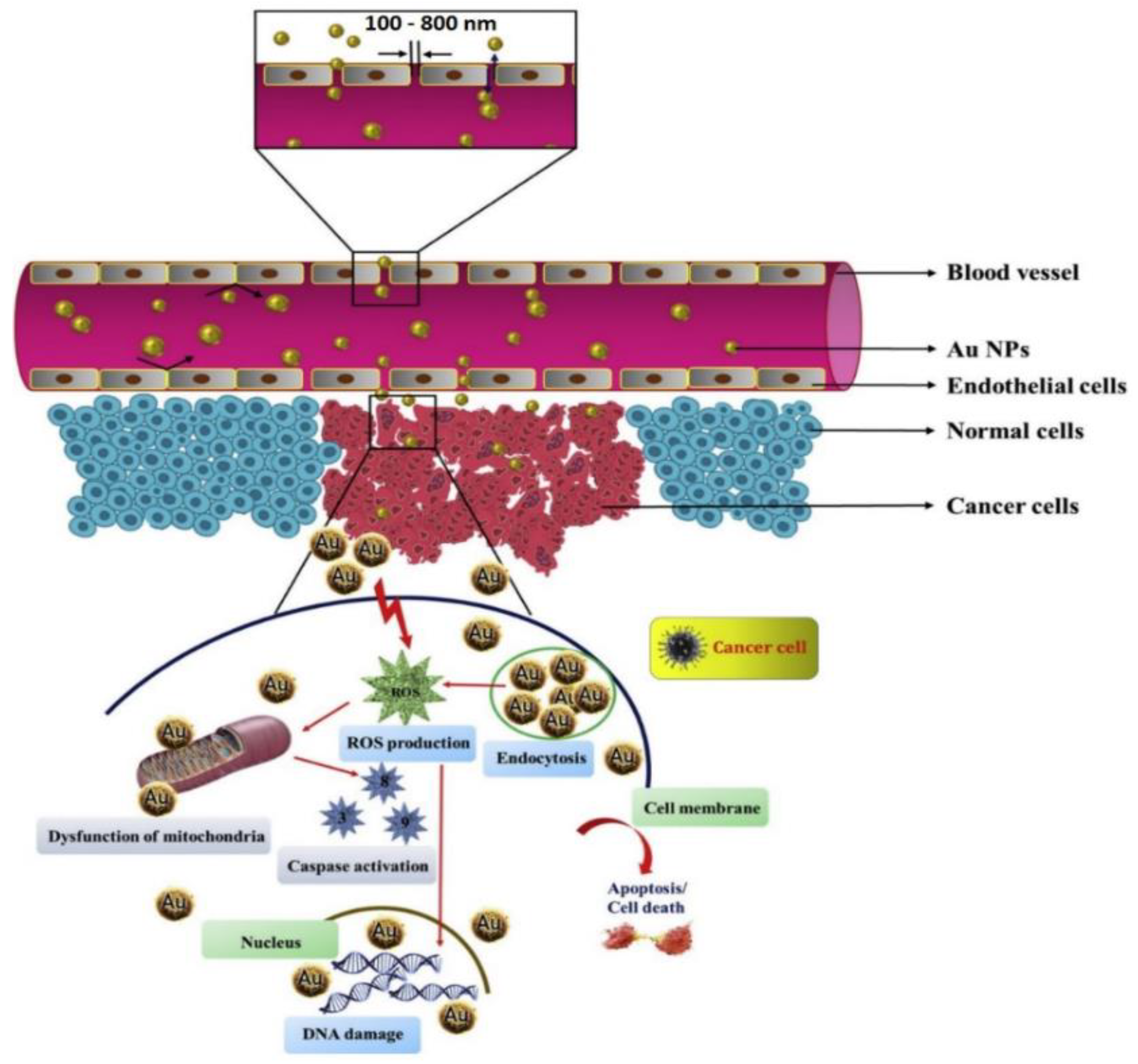

9.1. Au NPs synthesis

9.2. Green Au NPs Applications in Cancer Therapy and Diagnosis

10. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1D | one-dimensional |

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| AFM | atomic force microscopy |

| BET | Brunauer, Emmett and Teller |

| BJH | Barrett-Joyner-Halenda |

| GCD | galvanostatic charge and discharge |

| CR dye | congo red dye |

| EDX | energy dispersive X-ray |

| Eg | energy bandgap |

| HAuCl4 | chloroauric acid |

| HCT-116 | colon cancer cell line |

| HepG-2 | human liver cancer cell line |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| hʋ | photon energy |

| HSV-1 and 2 | herpes simplex virus |

| KMnO4 | potassium permanganate |

| LDHA | lactate dehydrogenase analysis |

| LIBs | lithium-ion batteries |

| MB dye | methylene blue dye |

| MCF-7 | breast cancer cell line |

| MDO | manganese dioxide |

| NIH 3T3 | non-cancerous cell |

| NPs | nanoparticles |

| SC | specific capacitance |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SPR | surface plasmon resonance |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| UV-Vis | ultraviolet-visible |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ZnO | zinc oxide |

References

- Mattos, B.D.; Rojas, O.J.; Magalhães, W.L. Biogenic silica nanoparticles loaded with neem bark extract as green, slow-release biocide. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4206–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinpour, V.; Souri, M.; Ghaemi, N. Green synthesis, characterisation, and photocatalytic activity of manganese dioxide nanoparticles. Micro Nano Lett. 2018, 13, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegbeleye, O.O. How functional is Moringa oleifera? A review of its nutritive, medicinal, and socioeconomic potential. Food Nutr. Bull. 2018, 39, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Ezhilarasi, A.A.; Vijaya, J.J.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Maaza, M.; Ayeshamariam, A.; Kennedy, L.J. Green synthesis of NiO nanoparticles using Moringa oleifera extract and their biomedical applications: Cytotoxicity effect of nanoparticles against HT-29 cancer cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2016, 164, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elechiguerra, J.L.; Burt, J.L.; Morones, J.R.; Camacho-Bragado, A.; Gao, X.; Lara, H.H.; Yacaman, M.J. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with HIV-1. J. Nanobiotechnology 2005, 3, 6–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.; Fawcett, D.; Sharma, S.; Tripathy, S.K.; Poinern, G.E.J. Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles via Biological Entities. Materials 2015, 8, 7278–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, C.M.; Ghotekar, S.; Viet, N.M.; Dabhane, H.; Oza, R.; Roy, A. Green synthesis of plant-assisted manganese-based nanoparticles and their various applications. In Plant and Nanoparticles; Chen, J.-T., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Vanlalveni, C.; Lallianrawna, S.; Biswas, A.; Selvaraj, M.; Changmai, B.; Rokhum, S.L. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts and their antimicrobial activities: a review of recent literature. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 2804–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, B.; Ikram, M.; Farooq, F.; Sultana, T.; Raja, N.I. Biogenesis of silver nanoparticles to treat cancer, diabetes and microbial infections: A mechanistic overview. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 6, 2261–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhane, H.; Ghotekar, S.K.; Tambade, P.J.; Pansambal, S.; Ananda-Murthy, H.C.; Oza, R.; Medhane, V. Cow urine mediated green synthesis of nanomaterial and their applications: A state-of-the-art review. J. Water Environ. Nanotechnol. 2021, 6, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chouke, P.B.; Shrirame, T.; Potbhare, A.K.; Mondal, A.; Chaudhary, A.R.; Mondal, S.; Thakare, S.R.; Nepovimova, E.; Valis, M.; Kuca, K.; et al. Bioinspired metal/metal oxide nanoparticles: A road map to potential applications. Mater. Today Adv. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhane, H.; Ghotekar, S.; Tambade, P.; Pansambal, S.; Murthy, H.A.; Oza, R.; Medhane, V. A review on environmentally benevolent synthesis of CdS nanoparticle and their applications. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2021, 3, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arabian J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotekar, S.; Pagar, K.; Pansambal, S.; Murthy, H.A.; Oza, R. A review on eco-friendly synthesis of BiVO4 nanoparticle and its eclectic applications. Adv. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 1, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sekoai, P.T.; Ouma, C.N.M.; du Preez, S.P.; Modisha, P.; Engelbrecht, N.; Bessarabov, D.G.; Ghimire, A. Application of nanoparticles in biofuels: An overview. Fuel 2018, 237, 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, P.; Ghotekar, S.; Pagar, T.; Pansambal, S.; Oza, R.; Mane, D. Plant extract assisted eco-benevolent synthesis of selenium nanoparticles - A review on plant parts involved, characterization and their recent applications. J. Chem. Rev. 2020, 2, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Alinezhad, H.; Pakzad, K.; Nasrollahzadeh, M. Efficient Sonogashira and A3 coupling reactions catalyzed by biosynthesized magnetic Fe3O4@Ni nanoparticles from Euphorbia maculata extract. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, e5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakzad, K.; Alinezhad, H.; Nasrollahzadeh, M. Green synthesis of Ni@Fe3O4 and CuO nanoparticles using Euphorbia maculata extract as photocatalysts for the degradation of organic pollutants under UV-irradiation. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 17173–17182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, X.; Khan, S.A.; Li, W.; Wan, L. Biogenic Synthesis of MnO2 Nanoparticles With Leaf Extract of Viola betonicifolia for Enhanced Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Cytotoxic, and Biocompatible Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virkutyte, J.; Varma, R.S. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles: Biodegradable polymers and enzymes in stabilization and surface functionalization. Chem. Sci. 2010, 2, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciorîță, A.; Suciu, M.; Macavei, S.; Kacso, I.; Lung, I.; Soran, M.L.; Pârvu, M. Green synthesis of Ag-MnO2 nanoparticles using chelidonium majus and vinca minor extracts and their in vitro cytotoxicity. Molecules 2020, 25, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, C.; Duranti, A.; Morelli, A.; Busani, L.; Pezzotti, P. Zoonosi in Italia nel periodo 2009-Rapporti ISTISAN. 2016. Available online: http://www. epicentro. iss. it/ben/2010/gennaio/1. asp (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Alqarni, L.S.; Alghamdi, M.D.; Alshahrani, A.A.; Nassar, A.M. Green Nanotechnology: Recent Research on Bioresource-Based Nanoparticle Synthesis and Applications. J. Chem. 2022, 2022, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, H.; Bhui, D.K.; Sahoo, G.P.; Sarkar, P.; Pyne, S.; Misra, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using seed extract of Jatropha curcas. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 348, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.R.; Nayak, V.; Sarkar, T.; Singh, R.P. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: properties, biosynthesis and biomedical application. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 27194–27214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Dutta, T.; Kim, K.-H.; Rawat, M.; Samddar, P.; Kumar, P. ‘Green’ synthesis of metals and their oxide nanoparticles: applications for environmental remediation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Shariq, M.; Asif, M.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Malan, P.; Ahmad, F. Green Nanotechnology: Plant-Mediated Nanoparticle Synthesis and Application. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagar, T.; Ghotekar, S.; Pagar, K.; Pansambal, S.; Oza, R. A review on bio-synthesized Co3O4 nanoparticles using plant extracts and their diverse applications. J. Chem. Rev. 2019, 1, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, M.; Giovanela, M.; Roesch-Ely, M.; Devine, D.M.; da Silva Crespo, J. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: A review of the synthesis methodology and mechanism of formation. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2020, 15, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikam, A.; Pagar, T.; Ghotekar, S.; Pagar, K.; Pansambal, S. A Review on Plant Extract Mediated Green Synthesis of Zirconia Nanoparticles and Their Miscellaneous Applications. J. Chem. Rev. 2019, 1, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagar, T.; Ghotekar, S.; Pansambal, S.; Oza, R.; Marasini, B.P. Facile plant extract mediated eco-benevolent synthesis and recent applications of CaO-NPs: A state-of-the-art review. J. Chem. Rev. 2020, 2, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Matussin, S.; Harunsani, M.H.; Tan, A.L.; Khan, M.M. Plant-Extract-Mediated SnO2 Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3040–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhane, H.; Ghotekar, S.; Tambade, P.; Medhane, V. Plant mediated green synthesis of lanthanum oxide (La2O3) nanoparticles: A review. Asian J. of Nanosci. Mater. 2020, 3, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Revathi, N.; Sankarganesh, M.; Raja, J.D.; Rajakanna, J.; Senthilkumar, O. Green synthesis of Plectranthus amboinicus leaf extract incorporated fine-tuned manganese dioxide nanoparticles: Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameta, R.; Kumar Rai, A.; Vyas, S.; Bhatt, J.P.; Ameta, S.C. Green synthesis of nanocomposites using plant extracts and their applications. In Handbook of Greener Synthesis of Nanomaterials and Compounds, Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021, vol. 1, chapter 20, pp. 663–682.

- Chopra, H.; Bibi, S.; Singh, I.; Hasan, M.M.; Khan, M.S.; Yousafi, Q.; Baig, A.A.; Rahman, M.; Islam, F.; Bin Emran, T.; et al. Green Metallic Nanoparticles: Biosynthesis to Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 874742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puente, C.; López, I. Plant extracts: a key ingredient for a greener synthesis of plasmonic nanoparticles. In Handbook of Greener Synthesis of Nanomaterials and Compounds, Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021, vol. 1, chapter 24, pp. 753–784.

- Papolu, P.; Bhogi, A. Green synthesis of various metal oxide nanoparticles for the environmental remediation-An overview. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, 92, 924–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gour, A.; Jain, N.K. , Advances in green synthesis of nanoparticles, Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol., 47 (2019) 844–851.

- Gupta, D.; Boora, A.; Thakur, A.; Gupta, T.K. Green and sustainable synthesis of nanomaterials: Recent advancements and limitations. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoun, S.; Arif, R.; Jangid, N.K.; Meena, R.K. Green synthesis of nanoparticles using plant extracts: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 19, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I. Phyto-nanofabrication: Plant-mediated synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles. In Handbook of Research on Green Synthesis and Applications of Nanomaterials; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, S.J.P.; Pratibha, S.; Rawat, J.M.; Venugopal, D.; Sahu, P.; Gowda, A.; Qureshi, K.A.; Jaremko, M. Recent Advances in Green Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Bioactive Metallic Nanoparticles. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiong, M.C.; Chong, C.T.; Ng, J.-H.; Lam, S.S.; Tran, M.-V.; Chong, W.W.F.; Jaafar, M.N.M.; Valera-Medina, A. Liquid biofuels production and emissions performance in gas turbines: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 173, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Kumar, R. Biogenesis of MnO2 Nanoparticles Using Momordica Charantia Leaf Extract. ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadimicherla, R.; Zha, R.; Wei, L.; Guo, X. Single crystalline flowerlike α-MoO3 nanorods and their application as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 687, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, V.; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Cuong, H.N.; S, R.; Saini, A.; Saini, R.V.; Van Le, Q.; Nadda, A.K.; Le, T.-T.; et al. Sustainable and green trends in using plant extracts for the synthesis of biogenic metal nanoparticles toward environmental and pharmaceutical advances: A review. Environ. Res. 2021, 202, 111622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, A.; Ijaz, I.; Gilani, E.; Nazir, A.; Zain, H.; Saeed, R.; Alarfaji, S.S.; Hussain, S.; Aftab, R.; Naseer, Y. Green Synthesis of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles Using Different Plants’ Parts for Antimicrobial Activity and Anticancer Activity: A Review Article. Coatings 2021, 11, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Kumar Das, T. Plant mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles-A review. Int. J. Plant Biol. Res. 2015, 3, 1044. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, S.; Verma, R.; Chauhan, A.; Raja, V.; Kumari, S.; Kulshrestha, S. Biogenic approach for synthesis of nanoparticles via plants for biomedical applications: A review. Mater. Today: Proc. [CrossRef]

- Bhau, B.; Ghosh, S.; Puri, S.; Borah, B.; Sarmah, D.K.; Raju, K. Green Synthesis Of Gold Nanoparticles From The Leaf Extract Of Nepenthes Khasiana And Antimicrobial Assay. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2015, 6, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, V.; Saravanan, P.; Sreedhar, B.; Devi, D.K.; Sashidhar, R. A facile synthesis and characterization of Ag, Au and Pt nanoparticles using a natural hydrocolloid gum kondagogu (Cochlospermum gossypium). Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2011, 83, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkateswarlu, S.; Kumar, B.N.; Prathima, B.; Anitha, K.; Jyothi, N. A novel green synthesis of Fe3O4-Ag core shell recyclable nanoparticles using Vitis vinifera stem extract and its enhanced antibacterial performance. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 2015, 457, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, S.; Tahir, A.; Chen, Y. Green Synthesis of Iron Nanoparticles and Their Environmental Applications and Implications. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keihan, A.H.; Veisi, H.; Veasi, H. Green synthesis and characterization of spherical copper nanoparticles as organometallic antibacterial agent. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, S.; Tahir, A.; Asim, T.; Chen, Y. Plant Mediated Green Synthesis of CuO Nanoparticles: Comparison of Toxicity of Engineered and Plant Mediated CuO Nanoparticles towards Daphnia magna. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisi, H.; Rostami, A.; Shirinbayan, M. Greener approach for synthesis of monodispersed palladium nanoparticles using aqueous extract of green tea and their catalytic activity for the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction and the reduction of nitroarenes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakumar, G.; Rahuman, A.A.; Chung, I.M.; Kirthi, A.V.; Marimuthu, S.; Anbarasan, K. Antiplasmodial, activity of eco-friendly synthesized palladium nanoparticles using Eclipta prostrate extract against Plasmodium berghei in Swiss albino mice. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, I.-M.; Rahuman, A.A.; Marimuthu, S.; Kirthi, A.V.; Anbarasan, K.; Rajakumar, G. An Investigation of the Cytotoxicity and Caspase-Mediated Apoptotic Effect of Green Synthesized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Eclipta prostrata on Human Liver Carcinoma Cells. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmad, M.; Swami, B.L.; Ikram, S. A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: A green expertise. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.-K.; Shim, M. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using marine algae Ecklonia cava. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.H.; Ma, Y.J.; Wang, J.W. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Taxus yunnanensis Callus and Their Antibacterial Activity and Cytotoxicity in Human Cancer Cells. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Zhu, G.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Yu, A. Supercapacitive properties of Mn3O4 nanoparticles bio-synthesized from banana peel extract. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 23649–23652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.K.; Srivastava, P.; Ameen, S.; Akhtar, M.S.; Singh, G.; Yadava, S. Azadirachta indica plant-assisted green synthesis of Mn3O4 nanoparticles: Excellent thermal catalytic performance and chemical sensing behavior. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 472, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Botero, L.; Herrera, A.P.; Hinestroza, J.P. Oriented growth of α-MnO2 nanorods using natural extracts from grape stems and apple peels. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J.C. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Dutta, T.; Kim, K.-H.; Rawat, M.; Samddar, P.; Kumar, P. ‘Green’ synthesis of metals and their oxide nanoparticles: applications for environmental remediation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, M.M.; Juchelková, D.; Raclavská, H.; Sassmanová, V. Utilization of Biodegradable Wastes as a Clean Energy Source in the Developing Countries: A Case Study in Myanmar. Energies 2018, 11, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswathi, V.P.; Meera, S.; Maria, C.G.A.; Nidhin, M. Green synthesis of nanoparticles from biodegradable waste extracts and their applications: a critical review. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2022, 8, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, M.; De Bella, M.; Di Bella, M.; Gupta, A. Green synthesis of nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2021, 8, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, D.; Kumar Daima, H.; Kachhwaha, S.; Kothari, S.L. Synthesis of plant-mediated silver nanoparticles using papaya fruit extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial activities. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2009, 4, 557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem, A.; Abuzeid, H.; Kaus, M.; Indris, S.; Ehrenberg, H.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C. Green synthesis of nanosized manganese dioxide as positive electrode for lithium-ion batteries using lemon juice and citrus peel. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 262, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzeid, H.M.; Elsherif, S.A.; Ghany, N.A.A.; Hashem, A.M. Facile, cost-effective and eco-friendly green synthesis method of MnO2 as storage electrode materials for supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2018, 21, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, J.; Zhitomirsky, I. Application of octanohydroxamic acid for liquid-liquid extraction of manganese oxides and fabrication of supercapacitor electrodes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 515, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuzeid, H.M.; Hashem, A.M.; Kaus, M.; Knapp, M.; Indris, S.; Ehrenberg, H.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Electrochemical performance of nanosized MnO2 synthesized by redox route using biological reducing agents. J. Alloy. Compd. 2018, 746, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katata-Seru, L.; Moremedi, T.; Aremu, O.S.; Bahadur, I. Green synthesis of iron nanoparticles using Moringa oleifera extracts and their applications: Removal of nitrate from water and antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 256, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kim, Y.-J.; Zhang, D.; Yang, D.-C. Biological Synthesis of Nanoparticles from Plants and Microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, S.C. Green synthesis of nanoparticles and its potential application. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.K.; Pachapur, V.L.; Lonappan, L.; Naghdi, M.; Pulicharla, R.; Maiti, S.; Cledon, M.; Dalila, L.M.A.; Sarma, S.J.; Brar, S.K. Biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles: plants, animals and microbial aspects. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2017, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.S.; Ravikumar, M.; J. , A.J.; Selvarajan, E.; Patel, H.; Chander, P.S.; Soundarya, J.; Vuppala, S.; Balaji, R.; Chandrasekar, N. A Review on Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Their Diverse Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2022, 12, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Bhatt, S.C.; Verma, M.; Kumar, V.; Kim, H. A review on current trends in the green synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles, characterizations, and their applications. Environ. Nanotechnology, Monit. Manag. 2022, 18, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, H.; Bhui, D.K.; Sahoo, G.P.; Sarkar, P.; De, S.P.; Misra, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using latex of Jatropha curcas. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 339, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.; Falé, P.L.; Mourato, A.; Vaz, P.D.; Serralheiro, M.L.; Lino, A.R.L. Preparation and physicochemical characterization of Ag nanoparticles biosynthesised by Lippia citriodora (Lemon Verbena). Colloids Surf. B 2010, 81, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iravani, S.; Korbekandi, H.; Mirmohammadi, S.V.; Zolfaghari, B. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Chemical, physical and biological methods. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 9, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Vaseeharan, B.; Malaikozhundan, B.; Gopi, N.; Ekambaram, P.; Pachaiappan, R.; Velusamy, P.; Murugan, K.; Benelli, G.; Kumar, R.S.; et al. Therapeutic effects of gold nanoparticles synthesized using Musa paradisiaca peel extract against multiple antibiotic resistant Enterococcus faecalis biofilms and human lung cancer cells (A549). Microb. Pathog. 2017, 102, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netala, VR, Bukke, S. ; Domdi, L.; Soneya, S.; Reddy, G.S.; Bethu, M.S.; Kotakdi, V.S.; Saritha, K.V.; Tartte, V. Biogenesis of silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Indigofera hirsuta L. and their potential biomedical applications (3-in-1 system). Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1138–1148.

- Khatami, M.; Pourseyedi, S.; Khatami, M.; Hamidi, H.; Zaeifi, M.; Soltani, L. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using seed exudates of Sinapis arvensis as a novel bioresource, and evaluation of their antifungal activity. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2015, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Sabela, M.I.; Kanchi, S.; Mdluli, P.S.; Singh, G.; Stenström, T.A.; Bisetty, K. Biosynthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using Jacaranda mimosifolia flowers extract: Synergistic antibacterial activity and molecular simulated facet specific adsorption studies. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2016, 162, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, R.; Beulaja, M.; Thiagarajan, R.; Palanisam, S.; Goutham, G.; Koodalingam, A.; Prabhu, N.M.; Kannapiran, E.; Jothi Basu, M.; Arulvasu, C.; Arumugam, M. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Phyllanthus acidus L. fruits and characterization of its anti-inflammatory effect against H2O2 exposed rat peritoneal macrophages. Process Biochem. 2017, 55, 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Bhattacharya, W.; Singh, M.; Halder, D.; Mitra, A. Plant latex capped colloidal silver nanoparticles: a potent anti-biofilm and fungicidal formulatio. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 230, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.N.; Sakthivel, K.; Balasubramanian, V. Microwave assisted biosynthesis of rice shaped ZnO nanoparticles using Amorphophallus konjac tuber extract and its application in dye sensitized solar cells. Mater. Sci. Pol. 2017, 35, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, H.; Shabaan, L.D.; Rabie, G.; Raie, D.S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using cell free callus exudates of Medicago sativa L. Pak. J. Bot. 2015, 47, 1825–1929. [Google Scholar]

- Yallappa, S.; Manjanna, J.; Dhananjaya, B. Phytosynthesis of stable Au, Ag and Au–Ag alloy nanoparticles using J. Sambac leaves extract, and their enhanced antimicrobial activity in presence of organic antimicrobials. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 137, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.M.; Jacob, J.; Philip, D. Green synthesis and applications of Au–Ag bimetallic nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 137, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Bhardwaj, K.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Nepovimova, E.; Șen, F.; Regassa, H.; Singh, R.; Verma, R.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, D.; et al. Fruit Extract Mediated Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles: A New Avenue in Pomology Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidya, C.; Manjunatha, C.; Chandraprabha, M.N.; Rajshekar, M.; Mal, A.R. Hazard free green synthesis of ZnO nano-photocatalyst using Artocarpus heterophyllus leaf extract for the degradation of Congo red dye in water treatment applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3172–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souri, M.; Shakeri, A. Comparison of microwave and ultrasound assisted extraction methods on total phenol and tannin content and biological activity of Dittrichia graveolens (L. ) Greuter and its optimization by response surface methodology. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2018, 14, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmat, M.; Bhatti, H.; Rehman, A.; Chaudhry, H.; Yameen, M.; Iqbal, M.; Al-Mijalli, S.; Alwadai, N.; Fatima, M.; Abbas, M. Bionanocomposite of Au decorated MnO2 via in situ green synthesis route and antimicrobial activity evaluation. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, K.R.P.; Ikawati, Z.; Danarti, R.; Hertiani, T. Micro-titer plate assay for measurement of total phenolic and total flavonoid contents in medicinal plant extracts. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathna, T.; Mathew, L.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Raichur, A.M.; Mukherjee, A. Biomimetic Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Science, Technology & Applicability. In Biomimetics Learning from Nature; Intechopen: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrawatkul, P.; Nuthong, W.; Pimsen, R.; Thongsom, M. , Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Barringtoniaacutangula (L. ) Gaertn leaf extract as reducing agent and their antibacterial and antioxidantactivity. J. Appl. Sci. 2017, 16, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fatimah, I. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using extract of Parkia speciose Hassk pods assisted by microwave irradiation. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummer, S.; Madzimbamuto, T.; Chowdhury, M. Green Synthesis of Transition-Metal Nanoparticles and Their Oxides: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarov, V.V.; Love, A.J.; Sinitsyna, O.V.; Makarova, S.S.; Yaminsky, I.V.; Taliansky, M.E.; Kalinina, N.O. “Green” nanotechnologies: synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Acta Naturae 2014, 6, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwachukwu, I.M.; Nwanya, A.C.; Alshoaibi, A.; Awada, C.; Ekwealor, A.B.C.; Ezema, F.I. Recent Progress in green synthesized transition metal-based oxides in LIBs as energy storage devices. Current Opinion Electrochem. 2023, 39, 101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltham, R.D.; Brant, P. XPS studies of core binding energies in transition metal complexes. 2. Ligand group shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchon, A.; Belabbes, A. , Spin-orbitronics at transition metal interfaces. Solid State Phys. 2017, 68, 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, D.; Srinivasan, K.; Nehru, L.C. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles using Cynodon dactylon leaf extract for antibacterial and anticancer (A549 cell lines) activity. J. Nanomed. Res. 2017, 5, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.P.; Reis, I.; Bonatto, C.C. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles by plants: current trends and challenges. Green Process Nanotechnol. 2015, 9, 327–52. [Google Scholar]

- Soltys, L.; Olkhovyy, O.; Tatarchuk, T.; Naushad, M. Green Synthesis of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Principles of Green Chemistry and Raw Materials. Magnetochemistry 2021, 7, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghojavand, S.; Madani, M.; Karimi, J. Green Synthesis, Characterization and Antifungal Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Using Stems and Flowers of Felty Germander. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrababu, P.; Cheriyan, S.; Raghavan, R. Aloe vera leaf extract-assisted facile green synthesis of amorphous Fe2O3 for catalytic thermal decomposition of ammonium perchlorate. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 139, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.; Ghosh, N.N.; Das, M.; Adhikary, R.; Mandal, V.; Chattopadhyay, A.P. Green synthesis of antibacterial and antifungal silver nanoparticles using Citrus limetta peel extract: Experimental and theoretical studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, P.A.; Nava, O.; Soto-Robles, C.A.; Chinchillas-Chinchillas, M.J.; Garrafa-Galvez, H.E.; Baez-Lopez, Y.A.; Valdez-Núñez, K.P.; Vilchis-Nestor, A.R.; Castro-Beltrán, A. Improved photocatalytic efficiency of SnO2 nanoparticles through green synthesis. Optik 2020, 206, 164299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Shahid, M.; Noman, M.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Zubair, M.; Almatroudi, A.; Khurshid, M.; Tariq, F.; Mumtaz, R.; Li, B. Bioprospecting a native silver-resistant Bacillus safensis strain for green synthesis and subsequent antibacterial and anticancer activities of silver nanoparticles. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 24, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, E.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hossain, A.; Qiu, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, W.; Sun, G.; Li, B. , Green-synthetization of silver nanoparticles using endophytic bacteria isolated from garlic and its antifungal activity against wheat Fusarium head blight pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarance, P.; Luvankar, B.; Sales, J.; Khusro, A.; Agastian, P.; Tack, J.-C.; Al Khulaifi, M.M.; Al-Shwaiman, H.A.; Elgorban, A.M.; Syed, A.; et al. Green synthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticles using endophytic fungi Fusarium solani and its in-vitro anticancer and biomedical applications. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 27, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Bakshi, M.; Ghosh, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Das, P.; Das, S.; Chaudhuri, P. Green Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Mediated by Filamentous Fungi Isolated from Sundarban Mangrove Ecosystem, India. BioNanoScience 2019, 9, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhipa, H. Mycosynthesis of nanoparticles for smart agricultural practice: A green and eco-friendly approach. In Micro and Nano Technologies; Shukla, A.K., Iravani, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, Z.; Bódai, V.; Szakacs, G.; Erdélyi, B.; Fogarassy, Z.; Sáfrán, G.; Varga, T.; Kónya, Z.; Tóth-Szeles, E.; Szűcs, R.; et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by thermophilic filamentous fungi. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellapandian, C.; Ramkumar, B.; Puja, P.; Shanmuganathan, R.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Kumar, P. Gold nanoparticles using red seaweed Gracilaria verrucosa: Green synthesis, characterization and biocompatibility studies. Process. Biochem. 2019, 80, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, R.; Sundaramanickam, A.; Srinath, R.; Ramesh, T.; Saranya, K.; Meena, M.; Surya, P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by bloom forming marine microalgae Trichodesmium erythraeum and its applications in antioxidant, drug-resistant bacteria, and cytotoxicity activity. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2019, 23, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, D.; Das, N.; Das, N.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Sarmah, P.; Ghosh, K.; Chandel, M.; Rout, J.; Pandey, P.; Ghosh, N.N.; Bhattacharjee, C.R. Alga-mediated facile green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Photophysical, catalytic and antibacterial activity. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, e5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiraven, T.; Sundaramanickam, A.; Shanmugam, N.; Balasubramanian, T. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using marine algae Caulerpa racemosa and their antibacterial activity against some human pathogens. Appl. Nanosci. 2014, 5, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, S.; Leghari, S.A.K.; Ryma, N.U.A.; Farooqi, S.A. Green synthesis of metal-based nanoparticles and their applications. In Green Metal Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and their Applications, Kanchi, S.; Ahmed Shakeel, Ed.; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akçay, F.A.; Avcı, A. Effects of process conditions and yeast extract on the synthesis of selenium nanoparticles by a novel indigenous isolate Bacillus sp. EKT1 and characterization of nanoparticles. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 2233–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaraj, A.; Kumar, V.; Sunder, R.; Parthasarathy, K.; Kasivelu, G. Commercial Yeast Extracts Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Chloride Nanoparticles and their Anti-mycobacterial Activity. J. Clust. Sci. 2020, 31, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.; He, F.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Z.; Gao, F.; Zeng, M. Biosynthesis and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Using Yeast Extract as Reducing and Capping Agents. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Gautam, A.; Guleria, P.; Singh, K.; Kumar, V. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles and their environmental applications. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Heal. 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Fang, G.; Cao, Z.; Shang, Y.; Alfarraj, S.; Alharbi, S.A.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Duan, X. Green synthesis, characterization, cytotoxicity, antioxidant, and anti-human ovarian cancer activities of Curcumae kwangsiensis leaf aqueous extract green synthesized gold nanoparticles. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, Y.P.; Shameli, K.; Miyake, M.; Ahmad Khairudin, N.B.B.; Mohamad, S.E.B.; Naiki, T.; Lee, K.X. Green biosynthesis of superparamagnetic magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles and biomedical applications in targeted anticancer drug delivery system: A review. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 2287–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.T.; Ovais, M.; Ullah, I.; Ali, M.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Maaza, M. Physical properties, biological applications and biocompatibility studies on biosynthesized single phase cobalt oxide (Co3O4) nanoparticles via Sageretia thea (Osbeck.). Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, P.; Saravanan, K.; Manogar, P.; Johnson, J.; Vinoth, E.; Mayakannan, M. Green synthesis and characterization of biocompatible zinc oxide nanoparticles and evaluation of its antibacterial potential. Sens. Bio-Sensing Res. 2021, 31, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudiaf, M.; Messai, Y.; Bentouhami, E.; Schmutz, M.; Blanck, C.; Ruhlmann, L.; Bezzi, H.; Tairi, L.; Mekki, D.E. Green synthesis of NiO nanoparticles using Nigella sativa extract and their enhanced electro-catalytic activity for the 4-nitrophenol degradation. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 153, 110020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N.; Bin Humayoun, U.; Kumar, M.; Alam Zaidi, S.F.; Yoo, J.H.; Ali, N.; Jeong, D.I.; Lee, J.H.; Yoon, D.H. Citric acid mediated green synthesis of copper nanoparticles using cinnamon bark extract and its multifaceted applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 125974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, Y.-K.; Aminuzzaman, M.; Akhtaruzzaman; Muhammad, G. ; Ogawa, S.; Watanabe, A.; Tey, L.-H. Green Synthesis and Characterization of CuO Nanoparticles Derived from Papaya Peel Extract for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME). Sustainability 2021, 13, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.P.; Chaudhari, R.Y.; Nemade, M.S. Azadirachta indica leaves mediated green synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles: A review. Talanta Open 2022, 5, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveeka Zamare, Vutukuru S. S., Ravindra Babu, Biosynthesis of nanoparticles from agro-waste: A sustainable approach. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2016, 1, 85–92.

- Jayappa, M.D.; Ramaiah, C.K.; Kumar, M.A.P.; Suresh, D.; Prabhu, A.; Devasya, R.P.; Sheikh, S. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from the leaf, stem and in vitro grown callus of Mussaenda frondosa L.: characterization and their applications. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 3057–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, A.M.; Sivasankarapillai, V.S.; Rahdar, A.; Joseph, J.; Sadeghfar, F.; Anuf, A.R.; Rajesh, K.; Kyzas, G.Z. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles with antibacterial and antifungal activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1211, 128107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabaani, M.; Rahaiee, S.; Zare, M.; Jafari, S.M. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using loquat seed extract; Biological functions and photocatalytic degradation properties. LWT 2020, 134, 110133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Atarod, M.; Sajjadi, M.; Sajadi, S.M.; Issaabadi, Z. Plant-Mediated Green Synthesis of Nanostructures: Mechanisms, Characterization, and Applications. In Electrokinetics in Microfluidics; Elsevier: 2019; Vol. 28, pp. 199–322.

- Hussain, M.; Raja, N.I.; Iqbal, M.; Aslam, S. Applications of Plant Flavonoids in the Green Synthesis of Colloidal Silver Nanoparticles and Impacts on Human Health. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A: Sci. 2019, 43, 1381–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Lenka, A.; Dixit, P.K.; Dash, S.K. Biosynthesis, Biofunctionalizatio, and bioapplications of manganese nanomaterials: An overview. In Biomaterials-Based Sensors; Kumar, P., Dash, S.K., Ray, S., Parween, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, T.V.; Schettinger, M.R.C.; Chen, P.; Carvalho, F.; Avila, D.S.; Bowman, A.B.; Aschner, M. “Manganese-induced neurotoxicity: a review of its behavioral consequences and neuroprotective strategies”. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.S.; Patra, A. Green synthesis of MnO2 nanorods using Phyllanthus amarusplant extract and their fluorescence studies. Green Process Synth. 2017, 6, 549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Y. Synthesis and magnetic properties of nanoporous Co3O4 nanoflowers. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 114, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S. Green synthesis of nanocrystalline manganese (II, III) oxide. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2017, 71, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Yu, Y. Facile Synthesis of Carbon Spheres with Uniformly Dispersed MnO Nanoparticles for Lithium Ion Battery Anode. Electrochimica Acta 2014, 152, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Bhandari, S.; Khastgir, D. Synthesis of MnO2 nanoparticles and their effective utilization as UV protectors for outdoor high voltage polymeric insulators used in power transmission lines. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 32876–32890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xing, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, S. MnO Nanoparticles Interdispersed in 3D Porous Carbon Framework for High Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 12713–12718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovský, O.; Sedmidubský, D.; Šimek, P.; Sofer, Z.; Ulbrich, P.; Bartůněk, V. Synthesis of MnO, Mn2O3 and Mn3O4 nanocrystal clusters by thermal decomposition of manganese glycerolate. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-M.; Saito, N.; Kim, D.-W. Solution Plasma-Assisted Green Synthesis of MnO2Adsorbent and Removal of Cationic Pollutant. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanitha, P.; Karthikeyan, K.; Thirumoorthi, A. Green Synthesis of Bi3+- Mg2+ layered doubled hydroxides MnO2 nanocomposites supercapacitors. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2022, 3, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Cui, X.; Chen, W.; Ivey, D.G. Manganese oxide-based materials as electrochemical supercapacitor electrodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 40, 1697–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T.H.; Tran, G.T.; Nguyen, N.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Nguyen, D.T.C.; Tran, T.V. A critical review on the biosynthesis, properties, applications and future outlook of green MnO2 nanoparticles. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, P.; Wang, C. Fabrication and lithium storage properties of MnO2 hierarchical hollow cubes. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 654, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Shen, M.; Xia, Y.; Lu, M. Au/MnO2 nanostructured catalysts and their catalytic performance for the oxidation of 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural. Catal. Commun. 2015, 64, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-X.; Peng, D.; Huang, X.-J. Effect of morphology of α-MnO2 nanocrystals on electrochemical detection of toxic metal ions. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 34, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suib, S.L. Porous Manganese Oxide Octahedral Molecular Sieves and Octahedral Layered Materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Meng, L.; Fei, Z.; Dyson, P.J.; Jing, X.; Liu, X. MnO 2 nanosheets as an artificial enzyme to mimic oxidase for rapid and sensitive detection of glutathione. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 90, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabre, Y.; Pannetier, J. Structural and electrochemical properties of the proton / γ-MnO2 system. Prog. Solid State Chem. 1995, 23, 1–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-Y.; Han, L.-Q.; Sun, S.; Wang, C.-Y.; Chen, M.-M. MnO2/C composite electrodes free of conductive enhancer for supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 653, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Fan, H.; Sui, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W. Sodium in-situ intercalated ultrathin δ-MnO2 flakes electrode with enhanced intercalation capacitive performance for asymmetric supercapacitors. Chem. Select 2020, 5, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Fan, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Ren, X.; Peng, H.; Li, H.; Jiang, X.; Cao, X. Preparation of partially-cladding NiCo-LDH/Mn3O4 composite by electrodeposition route and its excellent supercapacitor performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 796, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Fan, H.; Ning, L.; Wang, W.; Sui, J. Templated manganese oxide by pyrolysis route as a promising candidate cathode for asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 843, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.M.; Abuzeid, H.M.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Abbas, H.; Ehrenberg, H.; Indris, S.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. MnO2 Nano-Rods Prepared by Redox Reaction as Cathodes in Lithium Batteries. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.M.; Abdel-Latif, A.M.; Abuzeid, H.M.; Abbas, H.M.; Ehrenberg, H.; Farag, R.S.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Improvement of the electrochemical performance of nanosized α-MnO2 used as cathode material for Li-batteries by Sn-doping. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 9669–9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Fan, H.; Yang, C.; Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Sui, J. Ultrathin δ-MnO2 nanoflakes with Na+ intercalation as a high-capacity cathode for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 17702–17712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ida, S.; Thapa, A.K.; Hidaka, Y.; Okamoto, Y.; Matsuka, M.; Hagiwara, H.; Ishihara, T. Manganese oxide with a card-house-like structure reassembled from nanosheets for rechargeable Li-air battery. J. Power Sources 2012, 203, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, M.M. Manganese oxides for lithium batteries. Prog. Solid State Chem. 1997, 25, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yanagisawa, K.; Yamasaki, N. Hydrothermal Soft Chemical Process for Synthesis of Manganese Oxides with Tunnel Structures. J. Porous Mater. 1998, 5, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.; Munichandraiah, N. Effect of Crystallographic Structure of MnO2 on Its Electrochemical Capacitance Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 4406–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Xing, S.; Ma, Z.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y. Effect of the KMnO4 concentration on the structure and electrochemical behavior of MnO2. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 3822–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, D.; Liu, H.; Zou, X.; Chen, T. Effect of MnO2 Crystalline Structure on the Catalytic Oxidation of Formaldehyde. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Nanostructured MnO2 as Electrode Materials for Energy Storage. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzeid, H.M.; Youddef, A.M.; Yakout, S.M.; Elnahrawy, A.M; Hashem, A.M. Green synthesized α-MnO2 as a photocatalytic reagent for methylene blue and congo red degradation. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 2171–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhdev, A.; Challa, M.; Narayani, L.; Manjunatha, A.S.; Deepthi, P.; Angadi, J.V.; Kumar, P.M.; Pasha, M. Synthesis, phase transformation, and morphology of hausmannite Mn3O4 nanoparticles: photocatalytic and antibacterial investigations. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Yang, H.; Ma, H.; Guo, S.; Cao, F.; Gong, J.; Deng, Y. Manganese oxide nanocomposite fabricated by a simple solid-state reaction and its ultraviolet photoresponse property. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 2619–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souri, M.; Hoseinpour, V.; Ghaemi, N.; Shakeri, A. Procedure optimization for green synthesis of manganese dioxide nanoparticles by Yucca gloriosa leaf extract. Int. Nano Lett. 2018, 9, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Tian, W.; Ding, W. Effect of preparation methods on morphology of active manganese dioxide and 2,4-dinitrophenol adsorption performance. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2018, 36, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Tian, X.; Yang, C.; Pi, Z.; Han, Q. , Facile synthesis of α-MnO2 nanorods for high-performance alkaline batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2010, 71, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Zhang, P.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Tian, S.; Wu, Y.; Holze, R. Electrochemical Performance of MnO2 Nanorods in Neutral Aqueous Electrolytes as a Cathode for Asymmetric Supercapacitors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 14020–14027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Sun, B.; Wei, M.; Luo, S.; Pan, F.; Xu, A.; Li, X. Catalytic degradation of Acid Orange 7 by manganese oxide octahedral molecular sieves with peroxymonosulfate under visible light irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 285, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Cui, X.; Zeng, R.; Du, G.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, R.; Ringer, S.P.; Dou, S.X. Performance modulation of α-MnO2 nanowires by crystal facet engineering. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Deng, L.; Qi, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Hasatani, M. Morphology-dependent Performance of Nanostructured MnO2 as an Oxygen Reduction Catalyst in Microbial Fuel Cells. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2015, 10, 3693–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, V.; Zhu, H.; Vajtai, R.; Ajayan, P.M.; Wei, B. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Pseudocapacitance Properties of MnO2 Nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 20207–20214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Li, B.; Du, H.; Kang, F.; Zeng, Y. Electrochemical properties of nanosized hydrous manganese dioxide synthesized by a self-reacting microemulsion method. J. Power Sources 2008, 180, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Tian, X.; Yang, C.; Pi, Z. Facile synthesis of α-MnO2 nanostructures for supercapacitors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2009, 44, 2062–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-L.; Fan, L.-Z.; Qu, X. Low temperature hydrothermal synthesis of nano-sized manganese oxide for supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2012, 66, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y. Controllable synthesis and characterization of α-MnO2 nanowires. J. Cryst. Growth 2016, 434, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Chen, J. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of uniform β-MnO2 nanorods for nitrite sensing. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 359, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.H.; Dong, B.; Guo, H.L.; Chai, Y.M.; Li, Y.-P.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-G. A facile hydrothermal synthesis and growth mechanism of novel hollow β-MnO2 polyhedral nanorods. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Hashem, A.M.; Abdel-Ghany, A.E.; El-Tawil, R.S.; Abuzeid, H.M.; Coughlin, A.; Chang, K.; Zhang, S.; El-Mounayri, H.; et al. Nanostructured Molybdenum-Oxide Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries: An Outstanding Increase in Capacity. Nanomaterials 2021, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanha, P.; Saengkwamsawang, P. Effect of stirring time on morphology and crystalline features of MnO2nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation method. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2017, 47, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhuang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xuan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W. Peptide-mediated green synthesis of the MnO2@ZIF-8 core–shell nanoparticles for efficient removal of pollutant dyes from wastewater via a synergistic process. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 608, 2779–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Bhargava, A.; Majumdar, S.; Tarafdar, J.C.; Panwar, J. Extracellular biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Aspergillus flavusNJP08: A mechanism perspective. Nanoscale 2010, 3, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khezeli, T.; Daneshfar, A.; Kardani, F. In-situ functionalization of MnO2 nanoparticles by natural tea polyphenols: A greener sorbent for dispersive solid-phase extraction of parabens from wastewater and cosmetics. Microchem. J. 2023, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinpour, V.; Ghaemi, N. Green synthesis of manganese nanoparticles: Applications and future perspective–A review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2018, 189, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, G.; Aain, Q.U.; Khalid, N.R.; Tahir, M.B.; Rafique, M.; Rizwan, M.; Hussain, S.; Iqbal, T.; Majid, A. A Review on Novel Eco-Friendly Green Approach to Synthesis TiO2 Nanoparticles Using Different Extracts. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2018, 28, 1552–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, S.; Sedaghati, F. CuO/Cu2O nanoparticles: A simple and green synthesis, characterization and their electrocatalytic performance toward formaldehyde oxidation. Microchem. J. 2018, 143, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Awad, A.; Ifthikar, J.; Liao, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, Z. Highly efficient α-Mn2O3@α-MnO2-500 nanocomposite for peroxymonosulfate activation: comprehensive investigation of manganese oxides. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 1590–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, T.; Mohanty, A.; Singh, L.; Muduli, S.; Parhi, P.K.; Sahoo, T.R. Effect of calcination temperature on morphology and phase transformation of MnO2 nanoparticles: A step towards green synthesis for reactive dye adsorption. Chemosphere 2021, 288, 132472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shafey, A.M. Green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles from plant leaf extracts and their applications: A review. Green Process. Synth. 2020, 9, 304–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardımcı, B.; Kanmaz, N. An effective-green strategy of methylene blue adsorption: Sustainable and low-cost waste cinnamon bark biomass enhanced via MnO2. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, J.S.; Krishna, S.B.N.; Pillay, K.; Sershen; Govender, P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Moringa oleifera leaf extracts and its antimicrobial potential. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 015011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimuri-Mofrad, R.; Hadi, R.; Tahmasebi, B.; Farhoudian, S.; Mehravar, M.; Nasiri, R. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using plant extract: Mini-review. Nanochem. Res. 2017, 2, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Majani, S.S.; Sathyan, S.; Manoj, M.V.; Vinod, N.; Pradeep, S.; Shivamallu, C.; K. N, V.; Kollur, S.P. Eco-friendly synthesis of MnO2 nanoparticles using Saraca asoca leaf extract and evaluation of in vitro anticancer activity. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Rahman, Q.; Raza, S.; Zehra, S.; Ahmad, N.; Husen, A. Chapter 23, Nanodimensional materials: An approach toward the biogenic synthesis. In Advances in Smart Nanomaterials and their Applications, Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pagar, T.; Ghotekar, S.; Pagar, K.; Pansambal, S.; Oza, R. Phytogenic synthesis of manganese dioxide nanoparticles using plant extracts and their biological application. In Handbook of Greener Synthesis of Nanomaterials and Compounds. Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; chapter 10, pp. 209–218.

- Terefe, A.; Balakrishnan, S. Manganese dioxide nanoparticles green synthesis using lemon and curcumin extracts and evaluation of photocatalytic activity. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 62, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.A.; Haque, M.M.; Akter, M.; Hossain, A.; Tamanna, A.N.; Hosen, M.M.; Kibria, A.F.; Khan, M.; Khan, M.A. Green synthesis of Bryophyllum pinnatum aqueous leaf extract mediated bio-molecule capped dilute ferromagnetic α-MnO2 nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 01508208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, N.O.M.; Yulizar, Y. Euphorbia heterophylla L. Leaf Extract-Mediated Synthesis of MnO2 Nanoparticles and Its Characterization. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020, 22, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjula, R.; Thenmozhi, M.; Thilagavathi, S.; Srinivasan, R.; Kathirvel, A. Green synthesis and characterization of manganese oxide nanoparticles from Gardenia resinifera leaves. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020, 26, 3559–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaraj, C.; Ji, B.-J.; Harper, S.L.; Yun, S.-I. Plant extract-mediated biogenic synthesis of silver, manganese dioxide, silver-doped manganese dioxide nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity against food- and water-borne pathogens. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegarescu, A.; Lung, I.; Leoștean, C.; Kacso, I.; Opriș, O.; Lazăr, M.D.; Copolovici, L.; Guțoiu, S.; Stan, M.; Popa, A.; et al. Green Synthesis, Characterization and Test of MnO2 Nanoparticles as Catalyst in Biofuel Production from Grape Residue and Seeds Oil. Waste Biomass- Valorization 2019, 11, 5003–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessie, Y.; Tadesse, S.; Eswaramoorthy, R. Physicochemical parameter influences and their optimization on the biosynthesis of MnO2 nanoparticles using Vernonia amygdalina leaf extract. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 6472–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Smita, K.; Galeas, S.; Sharma, V.; Guerrero, V.H.; Debut, A.; Cumbal, L. Characterization and application of biosynthesized iron oxide nanoparticles using Citrus paradisi peel: A sustainable approach. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanavade; M. J.; Jalkute, C.B.; Jai, S.; Kailash, G.; Sonawane, D. Study antimicrobial activity of lemon (Citrus lemon L.) peel extract. British J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2011, 2, 119–122.

- Munakata, R.; Inoue, T.; Koeduka, T.; Sasaki, K.; Tsurumaru, Y.; Sugiyama, A.; Uto, Y.; Hori, H.; Azuma, J.-I.; Yazaki, K. Characterization of Coumarin-Specific Prenyltransferase Activities inCitrus limonPeel. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 1389–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamaliroosta, L.; Zolfaghari, M.; Shafiee, S.; Larijani, K.; Zojaji, M. Chemical identifications of citrus peels essential oils. J. Food Biosci. Technol. 2016, 6, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Samat, N.A.; Nor, R.M. Sol–gel synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Citrus aurantifolia extracts. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, S545–S548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.M.; Salim-ur-Rehman, Z.; Iqbal-Anjum, F.M.; Sultan, J. I. Generic variability to essential oil composition in four citrus fruit species. Pakistan J. Bot. 2006, 38, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Housel, L.M.; Wang, L.; Abraham, A.; Huang, J.; Renderos, G.D.; Quilty, C.D.; Brady, A.B.; Marschilok, A.C.; Takeuchi, K.J.; Takeuchi, E.S. Investigation of α-MnO2 tunneled structures as model cation hosts for energy storage. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 16, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicat, J.; Fanchon, E.; Strobel, P.; Tran-Qui, D. The structure of K1. 33Mn8O16 and cation ordering in hollandite-type structures. Acta Crystallogr. B 1986, 42, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, C.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lid, S.; Liu, H. K0. 25Mn2O4 nanofiber microclusters as high power cathode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 1643–1649. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, G. , Helmer, F. , Poul, N. A comparison study on Raman scattering properties of α- and β-MnO2. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 648, 235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, K.; Sarkar, C.K.; Ghosh, C.K. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles usingfruit extract of malus domistica and study of its antimicrobial activity and biostructures. Digest J. Nanomater. 2014, 9, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.L.; Pontes, B.; Nishi, E.E.; Ibuki, F.K.; Oliveira, V.; Sawaya, A.C.; Cravalho, P.O.; Nogueira, F.N.; Franco, M.D.; Campos, R.R.; Oyama, L.M.; Bergamaschi, C.T. The antioxidant effects of green tea reduce blood pressure and sympatho excitation in an experimental model of hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2017, 35, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huyut, Z.; Beydemir, Ş.; Gülçin, I. Antioxidant and Antiradical Properties of Selected Flavonoids and Phenolic Compounds. Biochem. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Jawad, A.; Ifthikar, J.; Liao, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, Z. Highly efficient α-Mn2O3@α-MnO2-500 nanocomposite for peroxymonosulfate activation: comprehensive investigation of manganese oxides. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 1590–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Glerup, M.; Krumeich, F.; Nesper, R.; Fjellvåg, H.; Norby, P. Microstructures and Spectroscopic Properties of Cryptomelane-type Manganese Dioxide Nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 13134–13140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.; Massot, M.; Poinsignon, C. Lattice vibrations of manganese oxides. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2004, 60, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. , Vijh A., Zaghib K., Lithium Batteries: Science and Technology; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Li, L.; Zhao, J.; Yang, T.; Zhang, G.; He, H.; Sun, S. Precisely controlled synthesis of α-/β-MnO2 materials by adding Zn(acac)2 as a phase transformation-inducing agent. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 1477–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.; Paulose, R.; Parihar, V. Hybrid MnO2/CNT nanocomposite sheet with enhanced electrochemical performance via surfactant-free wet chemical route. Ionics 2017, 23, 3245–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, M.; Kochhar, A. Proximate composition, available carbohydrates, dietary fibre and anti-nutritional factors of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. Var. ItalicaPlenck) leaf and floret powder. Biosci. Discov. 2014, 5, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Campas-Baypoli, O.N.; Sánchez-Machado, D.I.; Bueno-Solano, C.; Núñez-Gastélum, J.A.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; López-Cervantes, J. Biochemical composition and physicochemical properties of broccoli flours. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

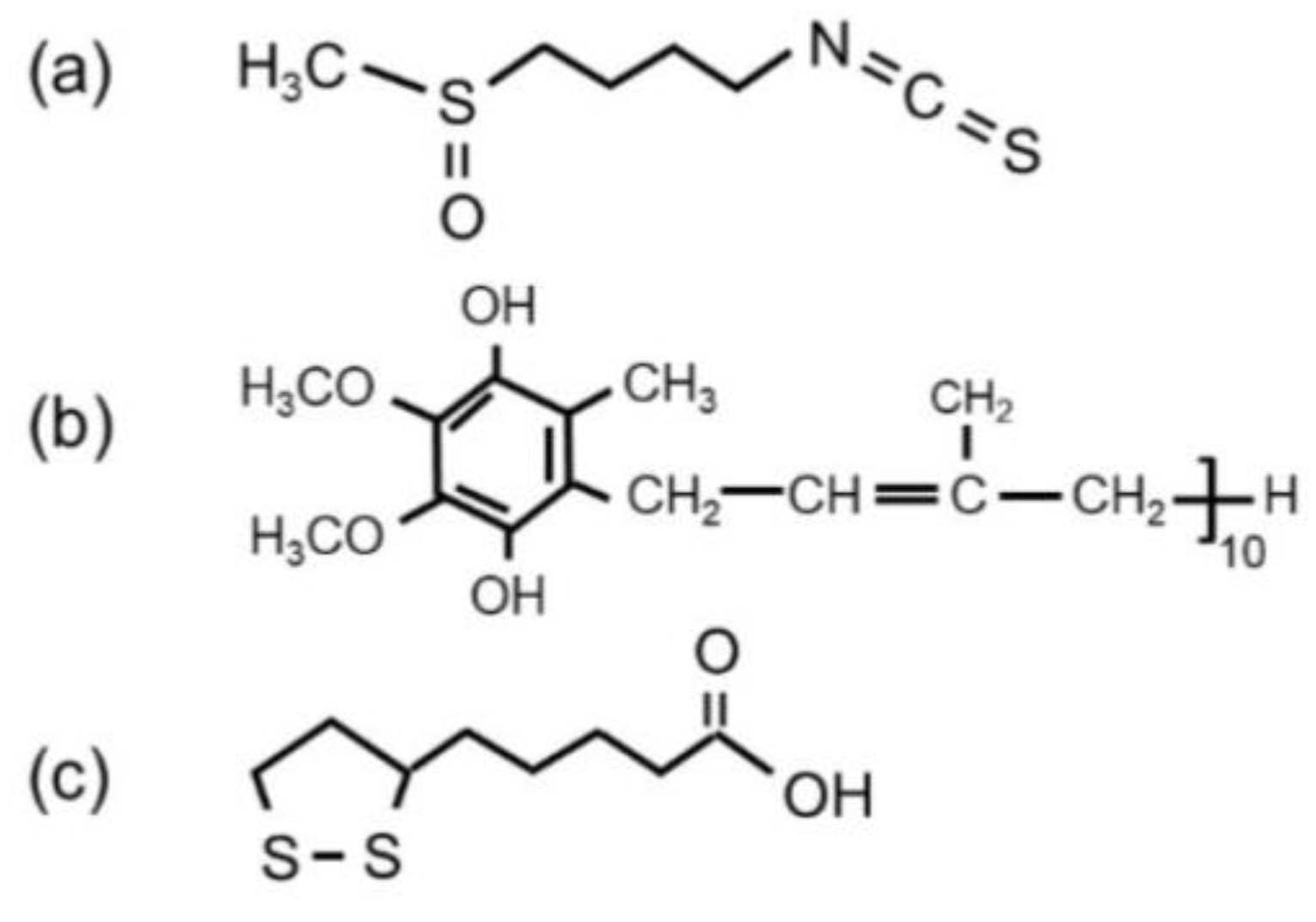

- Vallejo, F.; Tomás-Barberán, F.; García-Viguera, C. Health-Promoting Compounds in Broccoli as Influenced by Refrigerated Transport and Retail Sale Period. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3029–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

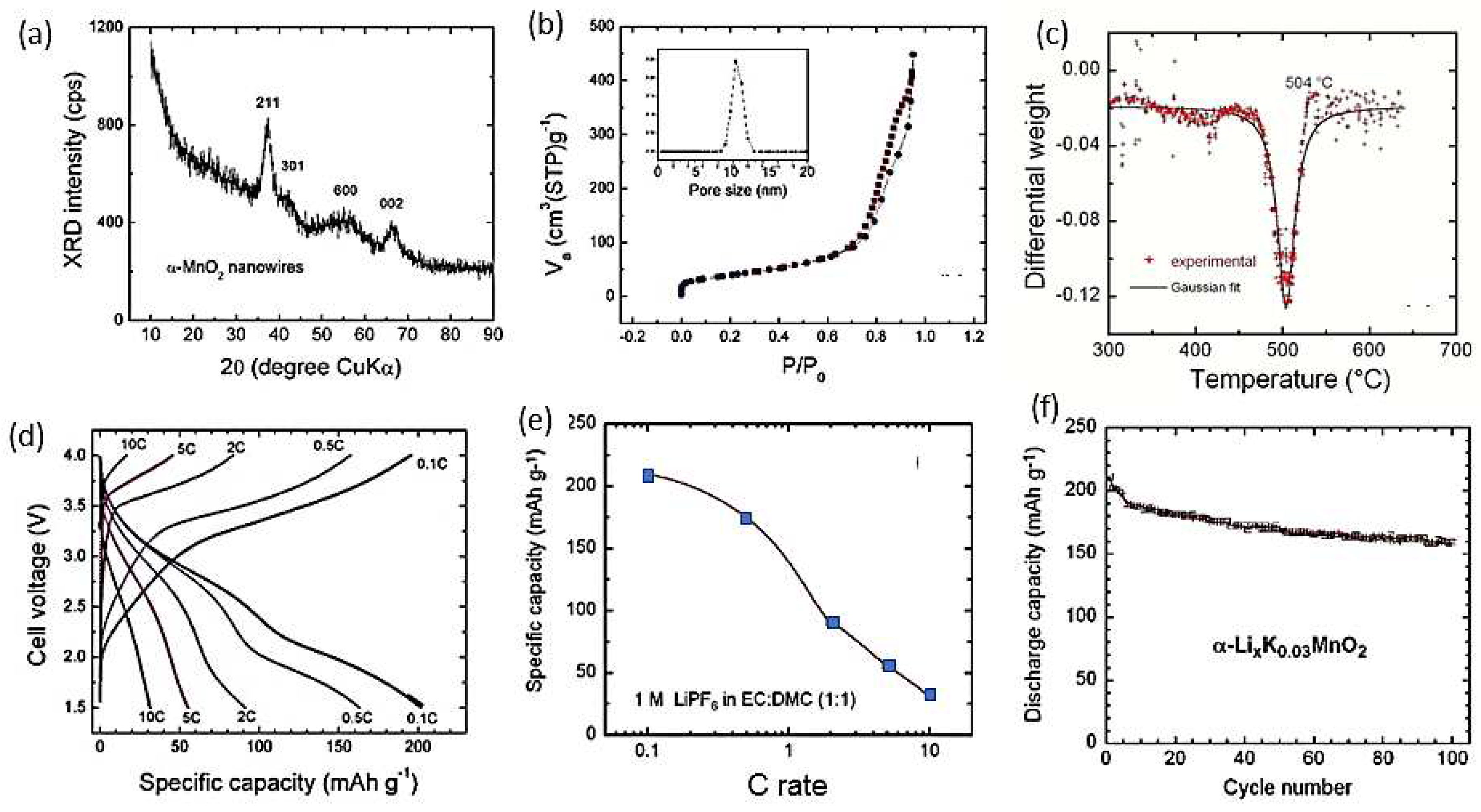

- Hashem, A.M.; Abuzeid, H.M.; Winter, M.; Li, J.; Julien, C.M. Synthesis of high surface area α-KyMnO2 nanoneedles using extract of broccoli as bioactive reducing agent and application in lithium battery. Materials 2020, 13, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyraz, A.S.; Kuo, C.-H.; Biswas, S.; King’ondu, C.K.; Suib, S.L. A general approach to crystalline and monomodal pore size mesoporous materials. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Rong, G.; Xie, Y.; Huang, L.; Feng, C. Low-temperature synthesis of alpha-MnO2 hollow urchins and their application in rechargeable Li+ batteries. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 6404–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Nan, C.; Lu, J.; Peng, Q.; Li, Y. α-MnO2 nanotubes: High surface area and enhanced lithium battery properties. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6945–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yang, S.; Wang, D.; Chen, A.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Liang, G.; Zhi, C. The energy storage mechanisms of MnO2 in batteries. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 30, 100769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Nie, A.; Odegard, G.M.; Xu, R.; Zhou, D.; Santhanagopalan, S.; He, K.; Asayesh-Ardakani, H.; Meng, D.D.; Klie, R.F.; Johnson, C.; Lu, J.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Asynchronous crystal cell expansion during lithiation of K+ stabilized α-MnO2. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 2998–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F. Hydrothermal synthesis and electrochemical characterization of α-MnO2 nanorods as cathode material for lithium batteries. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2008, 3, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Xie, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y. Facile synthesis of α-MnO2 nanorods at low temperature and their microwave absorption properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2014, 143, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, A.E.; Ibrahium, M.I. Antioxidant activities of orange peel extracts. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 18, 684–688. [Google Scholar]

- Mandalari, G.; Bennett, R.N.; Bisignano, G.; Saija, A.; Dugo, G.; Faulds, C.B.; Waldron, K.W. Characterization of flavonoids and pectin from bergamot (Citrus bergamia Risso) peel, a major byproduct of essential oil extraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bampidis, V.; Robinson, P. Citrus by-products as ruminant feeds: A review. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2006, 128, 175–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabinjo, O.O.; Ogunlowo, A.S.; Ajayi, O.O.; Olalusi, A.P. Analysis of Physical and Chemical Composition of Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis) Peels. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 2, 2201–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, M.I.; Vorobyova, V.I. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Orange Peel Extract Prepared by Plasmochemical Extraction Method and Degradation of Methylene Blue under Solar Irradiation. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toupin, M.; Brousse, T.; Bélanger, D. Charge Storage Mechanism of MnO2 Electrode Used in Aqueous Electrochemical Capacitor. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 3184–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Leng, K. ; Huang, Y; Chen, Y. A high-performance supercapacitor-battery hybrid energy storage device based on graphene enhanced electrode materials with ultrahigh energy density. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1623. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Dou, S.; Liu, H.; Dai, L. Cathode materials for next generation lithium ion batteries. Nano Energy 2013, 2, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhande, P.E. Synthesis and characterization of Ni. Co (OH)2 material for supercapacitor application. Int. Adv. Res. J. Sci Eng. Technol. 2015, 2, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Xiao, X.; Yu, A.; Chen, Z. Composites of MnO2 nanocrystals and partially graphitized hierarchically porous carbon spheres with improved rate capability for high-performance supercapacitors. Carbon 2015, 93, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.S.; Tripathi, K.M.; Kim, B.N.; You, I.-K.; Park, B.J.; Han, Y.H.; Kim, T. Y, Three-dimensionally assembled Graphene/α-MnO2 nanowire hybrid hydro gels for high performance supercapacitors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 96, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Lian, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Cui, X. High specific capacitance of polyaniline/mesoporous manganese dioxide composite using KIH2SO4 electrolyte. Polymers 2015, 7, 1939–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.; Abuzeid, H.; Abdel-Ghany, A.; Mauger, A.; Zaghib, K.; Julien, C. SnO2–MnO2 composite powders and their electrochemical properties. J. Power Sources 2011, 202, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gendy, D.M.; Ghany, N.A.A.; El Sherbini, E.E.F.; Allam, N.K. Adenine-functionalized Spongy Graphene for Green and High-Performance Supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep43104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premkumar, J.; Sudhakar, T.; Dhakal, A.; Shrestha, J.B.; Krishnakumar, S.; Balashanmugam, P. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) from cinnamon against bacterial pathogens. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 15, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, D.; Udayabhanu; Kumar, M. P.; Nagabhushana, H.; Sharma, S. Cinnamon supported facile green reduction of graphene oxide, its dye elimination and antioxidant activities. Mater. Lett. 2015, 151, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qiang, L.; Fan, R.; Ning, H.; Li, L.; Ye, T.; Yang, B.; Cao, W. Based on Cu(II) silicotungstate modified photoanode with long electron lifetime and enhanced performance in dye sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources 2015, 278, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nahrawy, A.M.; Moez, A.A.; Saad, A.M. Sol-Gel Preparation and Spectroscopic Properties of Modified Sodium Silicate /Tartrazine Dye Nanocomposite. Silicon 2018, 10, 2117–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nahrawy, A.M.; Mansour, A.-F.M.; Hammad, A.B.A.; Wassel, A.R. Effect of Cu incorporation on morphology and optical band gap properties of nano-porous lithium magneso-silicate (LMS) thin films. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 6, 016404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestaro, R.; Philippe, L.; Serrà, A.; Gómez, E.; Schmutz, P. Electrodeposited manganese oxides as efficient photocatalyst for the degradation of tetracycline antibiotics pollutant. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Bhattacharyya, K.G. Oxidation of Rhodamine B in aqueous medium in ambient conditions with raw and acid-activated MnO2, NiO, ZnO as catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2014, 391, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y. Preparation of MnO2-Carbon Materials and Their Applications in Photocatalytic Water Treatment. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.A.; Salunke, B.K.; Alkotaini, B.; Sathiyamoorthi, E.; Kim, B.S. Biological synthesis of manganese dioxide nanoparticles by Kalopanax pictus plant extract. IET Nanobiotechnology 2015, 9, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K, V.; G, P.; S, M.; G, R.; S, S. Echinochloa frumentacea grains extract mediated synthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles: A greener nano drug for potential biomedical applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.U.; Kareem, A.; Nami, S.A.; Khan, M.S.; Rehman, S.; Bhat, S.A.; Mohammad, A.; Nishat, N. Biogenic synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using Agrewia optiva and Prunus persica phyto species: Characterization, antibacterial and antioxidant activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2018, 185, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, P.; Márquez, K.; Rubilar, O.; Contreras, D.; Vidal, G. The effect of phenolic compounds on the green synthesis of iron nanoparticles (FexOy-NPs) with photocatalytic activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2019, 9, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgueitio, E.; Debut, A.; Landivar, J.; Cumbal, L. Synthesis of iron nanoparticles through extracts of native fruits of Ecuador, as capuli (Prunus serotina) and mortiño (Vaccinium floribundum). Biol. Med. 2016, 8, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, R.; Pai, S.; Vinayagam, R.; Varadavenkatesan, T.; Kumar, P.S.; Duc, P.A.; Rangasamy, G. A recent update on green synthesized iron and iron oxide nanoparticles for environmental applications. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, V.; Dhinesh, P.; Sundaramahalingam, S.; Rajaram, R. Green fabrication of iron oxide nanoparticles using grey mangrove Avicennia marina for antibiofilm activity and in vitro toxicity. Surfaces Interfaces 2019, 15, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latha, N.; Gowri, M. Bio synthesis and characterization of Fe3O4 nanoparticles using Caricaya papaya leaves extract. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Chen, M. Progress in the preparation and application of modified biochar for improved contaminant removal from water and wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, A.; Levendis, Y.A.; Vorobiev, N.; Schiemann, M. Direct observations on the combustion characteristics of Miscanthus and Beechwood biomass including fusion and spherodization. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 166, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her, S.; Jaffray, D.A.; Allen, C. Gold nanoparticles for applications in cancer radiotherapy: Mechanisms and recent advancements. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 109, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Sajid, S.; Javed, A.; Sajid, S.; Shah, S.U.; Khan, S.N.; Ullah, K. COMPARATIVE DIAGNOSIS OF TYPHOID FEVER BY POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION AND WIDAL TEST IN SOUTHERN DISTRICTS (BANNU, LAKKI MARWAT AND D.I.KHAN) OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA, PAKISTAN. Acta Sci. Malays. 2017, 1, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashique, S.; Upadhyay, A.; Hussain, A.; Bag, S.; Chaterjee, D.; Rihan, M.; Mishra, N.; Bhatt, S.; Puri, V.; Sharma, A.; et al. Green biogenic silver nanoparticles, therapeutic uses, recent advances, risk assessment, challenges, and future perspectives. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlapudi, V.; Kaladhar, D. Review: green synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2014, 19, 834–842. [Google Scholar]

- Rizki, I.N.; Klaypradit, W. ; Patmawati Utilization of marine organisms for the green synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and their applications: A review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghoraibia, I.; Soukkarieh, C.; Zein, R.; Alahmad, A.; Walter, J.-G.; Daghestani, M. Withdrawn: Aqueous Extract of Eucalyptus Camaldulensis Leaves as a Reducing and Capping Agent in Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Curr. Nanomater. 2019, 04, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, V.; Zamani, H.; Bajuli, L.; Moradshahi, A. Evaluation of antioxidant potential and reduction capacity of some plant extracts in silver nanoparticles' synthesis. . 2014, 3, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gopinath, V.; MubarakAli, D.; Priyadarshini, S.; Priyadharsshini, N.M.; Thajuddin, N.; Velusamy, P. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Tribulus terrestris and its antimicrobial activity: A novel biological approach. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2012, 96, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehata, M.S. Green route synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plants/ginger extracts with enhanced surface plasmon resonance and degradation of textile dye. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 273, 115418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaqad, K.; A Saleh, T. Gold and Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis Methods, Characterization Routes and Applications towards Drugs. J. Environ. Anal. Toxicol. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, A.A.H.; Mahmood, A.; Alsharidah, M.; Mohammed, H.A.; Alenize, S.K.; Bouazzaoui, A.; Al Rugaie, O.; Alnuqaydan, A.M.; Ahmad, R.; Vaali-Mohammad, M.-A.; et al. Bioactivities of the Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Reduced Using Allium cepa L Aqueous Extracts Induced Apoptosis in Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomathi, A.; Rajarathinam, S.X.; Sadiq, A.M.; Rajeshkumar, S. Anticancer activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using aqueous fruit shell extract of Tamarindus indica on MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 55, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.S.; Alsubhi, N.S. Green synthesis and anticancer activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using fruit extract of Azadirachta indica. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2022, 15, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Yasin, S. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Bamboo Leaves Extract and Their Antimicrobial Activity. J. Fiber Bioeng. Informatics 2013, 6, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A.; Ghasemi, Y.; Atapour, A.; Amani, A.M.; Savar Dashtaki, A.; Babapoor, A.; Arjmand, O. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles toward bio and medical applications: review study. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, S855–S872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luceri, A.; Francese, R.; Lembo, D.; Ferraris, M.; Balagna, C. Silver Nanoparticles: Review of Antiviral Properties, Mechanism of Action and Applications. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhave, R.V.; Vineeth, S.K.; Gadekar, P.T. Polymers and Polymeric Materials in COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review. Open J. Polym. Chem. 2020, 10, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathy, J.R.; Sankar, M.U.; Chaudhary, A.; Aigal, S.; Anshup; Pradeep, T. Antimicrobial silver: An unprecedented anion effect. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Yeom, M.; Lee, T.; Kim, H.-O.; Na, W.; Kang, A.; Lim, J.-W.; Park, G.; Park, C.; Song, D.; et al. Porous gold nanoparticles for attenuating infectivity of influenza A virus. J. Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Sun, R.W.-Y.; Chen, R.; Hui, C.-K.; Ho, C.-M.; Luk, J.M.; Lau, G.K.K.; Che, C.-M. Silver nanoparticles inhibit hepatitis B virus replication. Antivir. Ther. 2008, 13, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdiero, S.; Falanga, A.; Vitiello, M.; Cantisani, M.; Marra, V.; Galdiero, M. Silver Nanoparticles as Potential Antiviral Agents. Molecules 2011, 16, 8894–8918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremiah, S.S.; Miyakawa, K.; Morita, T.; Yamaoka, Y.; Ryo, A. Potent antiviral effect of silver nanoparticles on SARS-CoV-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 533, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaf, S.J.; Jadhav, N.R.; Naikwadi, H.S.; Savekar, P.L.; Sapkal, I.D.; Kambli, M.M.; Desai, I.A. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles: Updates on research, patents, and future prospects. OpenNano 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafout, M.; Ousaid, A.; Khayati, Y.; El Otmani, I.S. Gold nanoparticles as a drug delivery system for standard chemotherapeutics: A new lead for targeted pharmacological cancer treatments. Sci. Afr. 2021, 11, e00685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amina, S.J.; Guo, B. A Review on the Synthesis and Functionalization of Gold Nanoparticles as a Drug Delivery Vehicle. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, ume 15, 9823–9857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannathul, F.M.; Lalitha, P. , Biogenic green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their applications – A review of promising properties. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 143, 109800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.-Y.; Famouri, L.; Carroll, L.; Lee, Y.; Famouri, P. Rapid and efficient sonochemical formation of gold nanoparticles under ambient conditions using functional alkoxysilane. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2013, 20, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, G.; Hassan, Z.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, N.-S.; Kim, N.H.; Baek, K.; Hwang, I.; Park, C.G.; Kim, K. ; Highly stable, water-dispersible metal-nanoparticle-decorated polymer nanocapsules and their catalytic applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6414–6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vala, A.K. Exploration on green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus sydowii. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2014, 34, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.-L.; Hu, Y.-J.; Chen, J.; Bai, A.-M.; Ouyang, Y. Green synthesis and physical characterization of Au nanoparticles and their interaction with bovine serum albumin. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2014, 122, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]