Submitted:

17 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

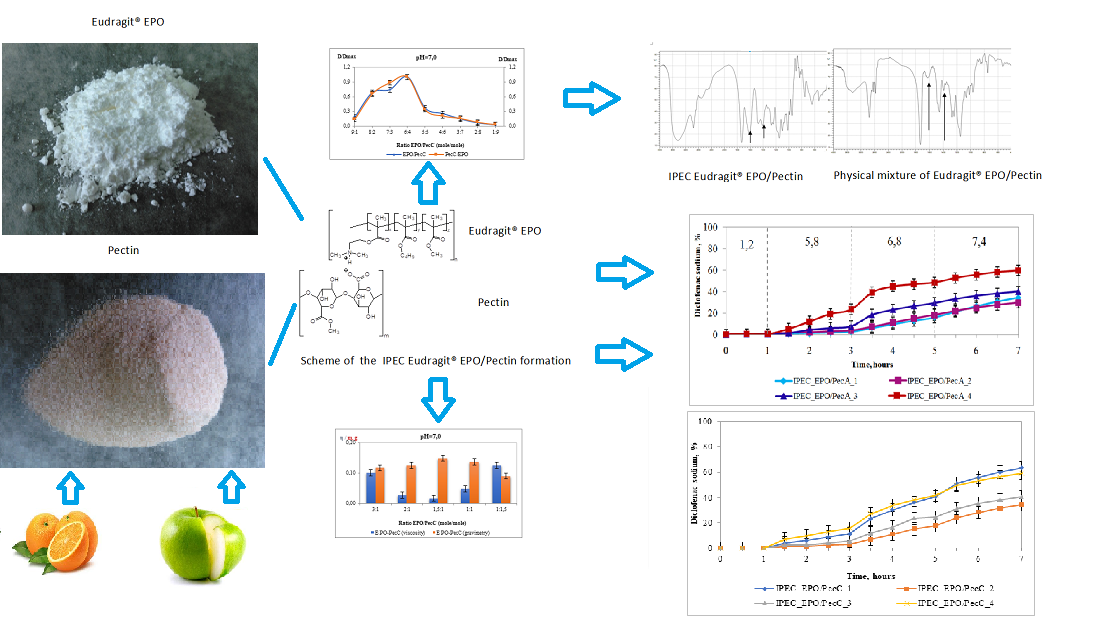

2. Results

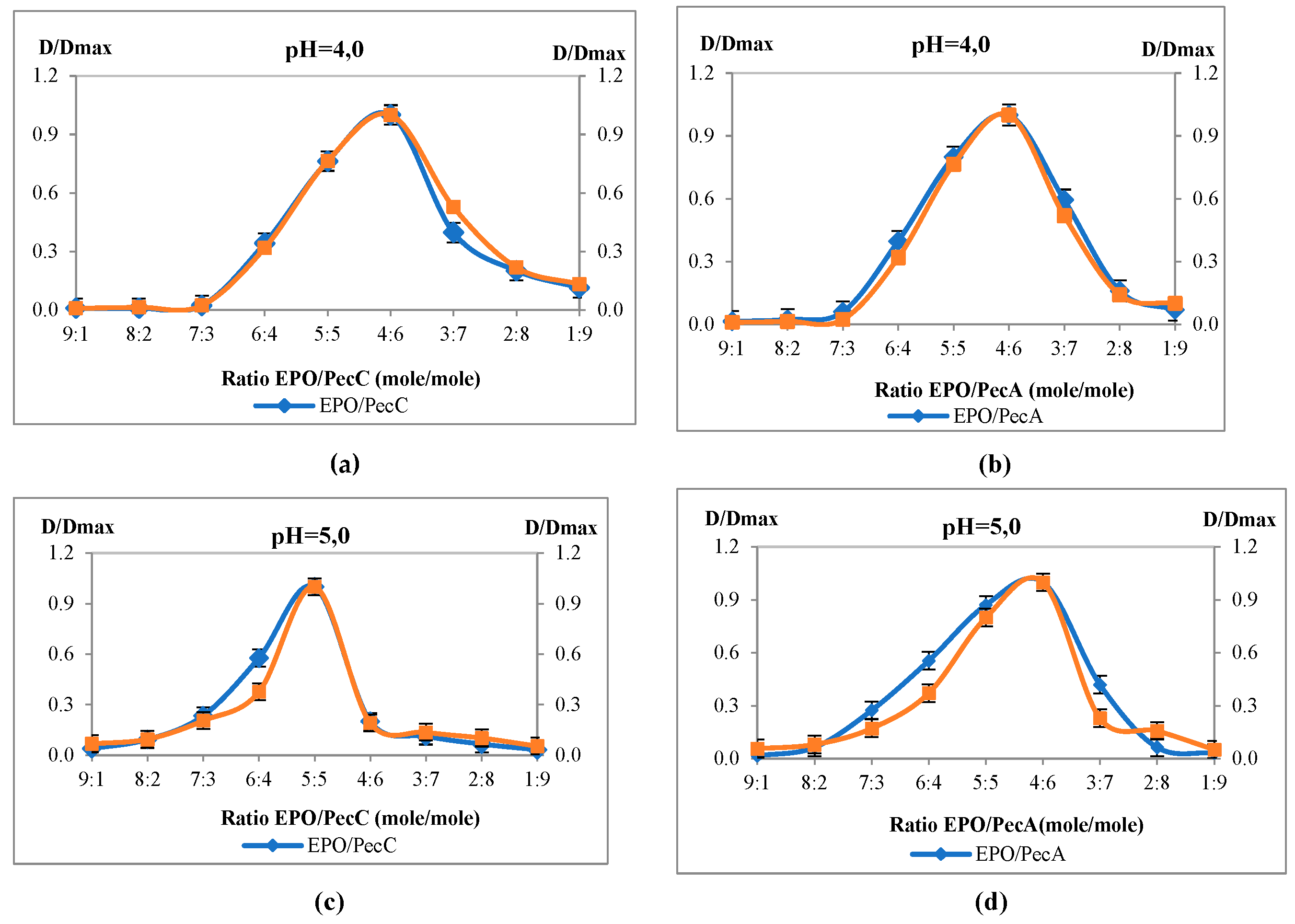

2.1. Turbidity measurements

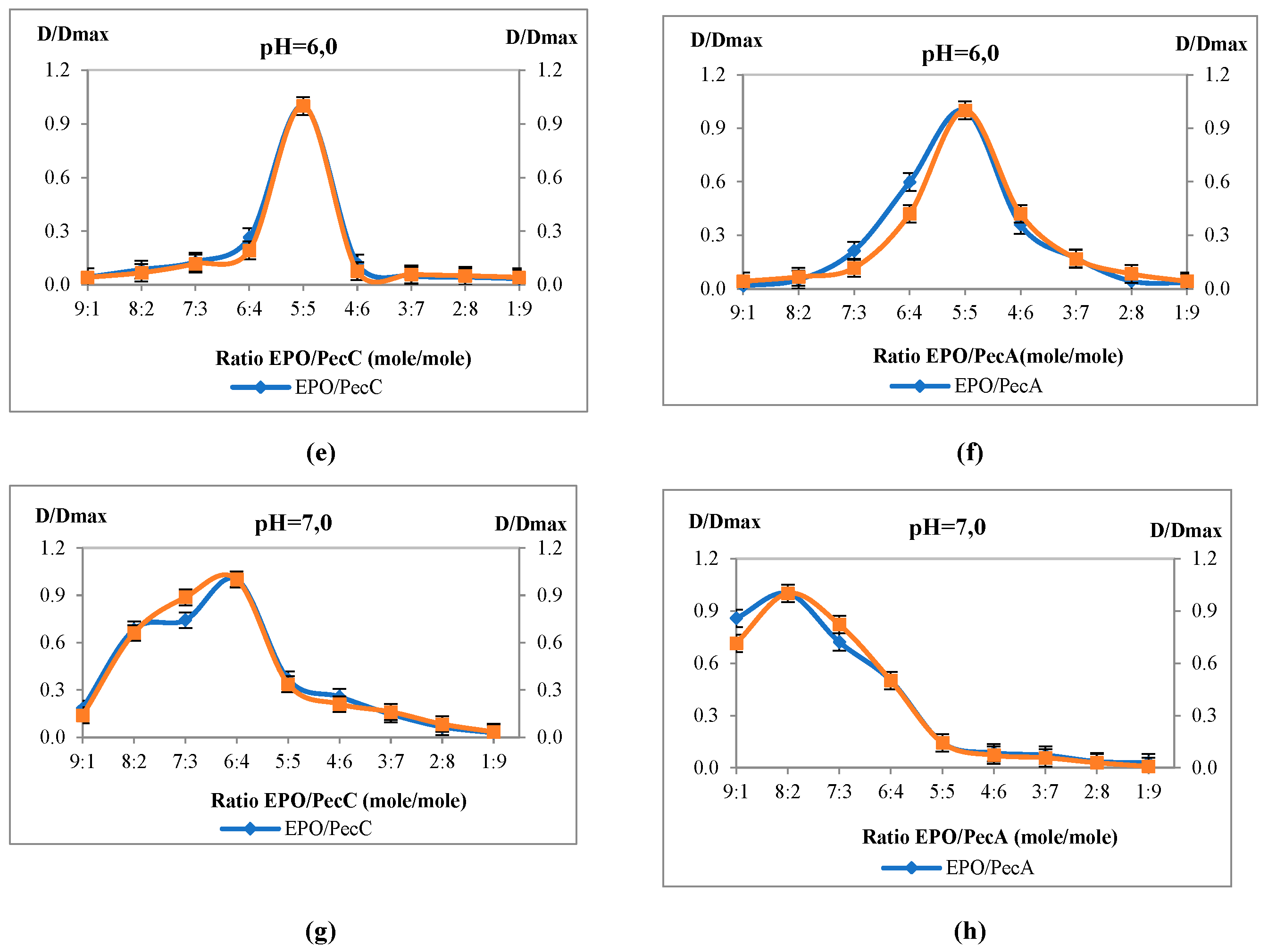

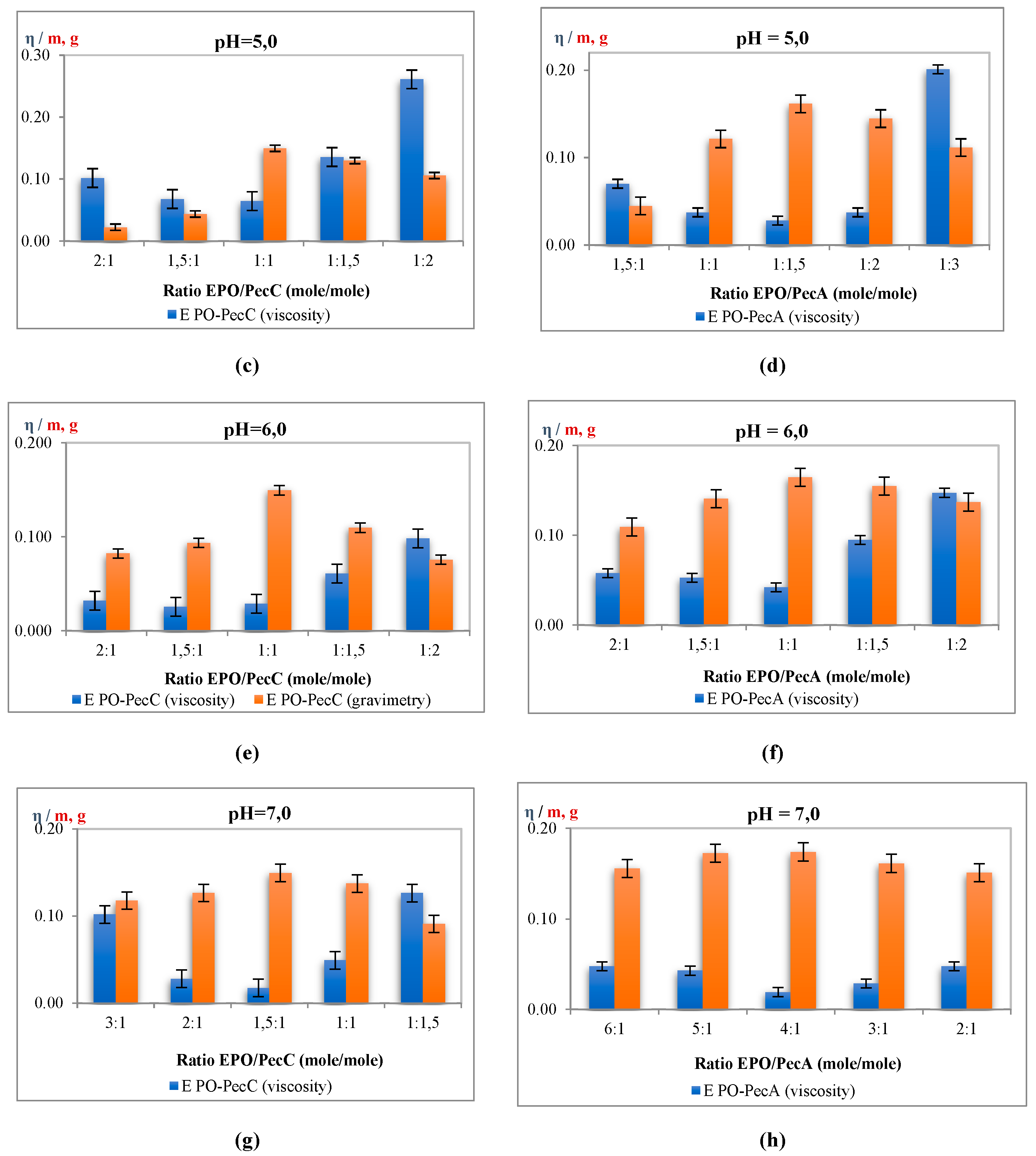

2.2. Apparent viscosity measurements and gravimetry

2.3. Elementary analyses

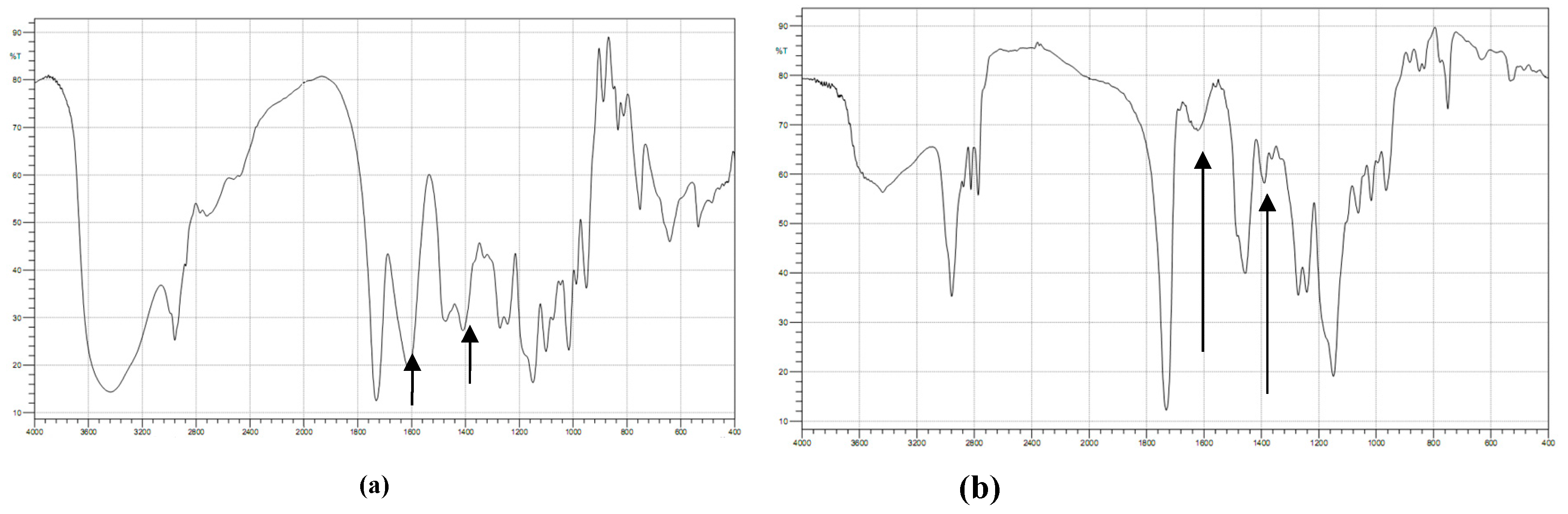

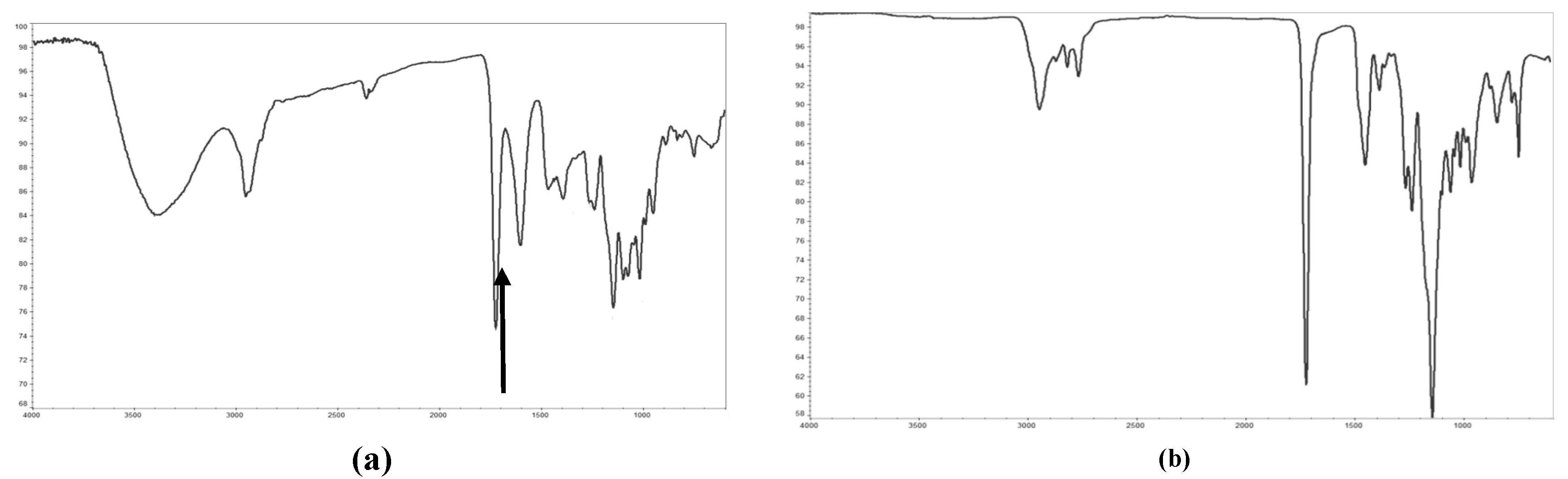

2.4. FT-IR spectroscopy

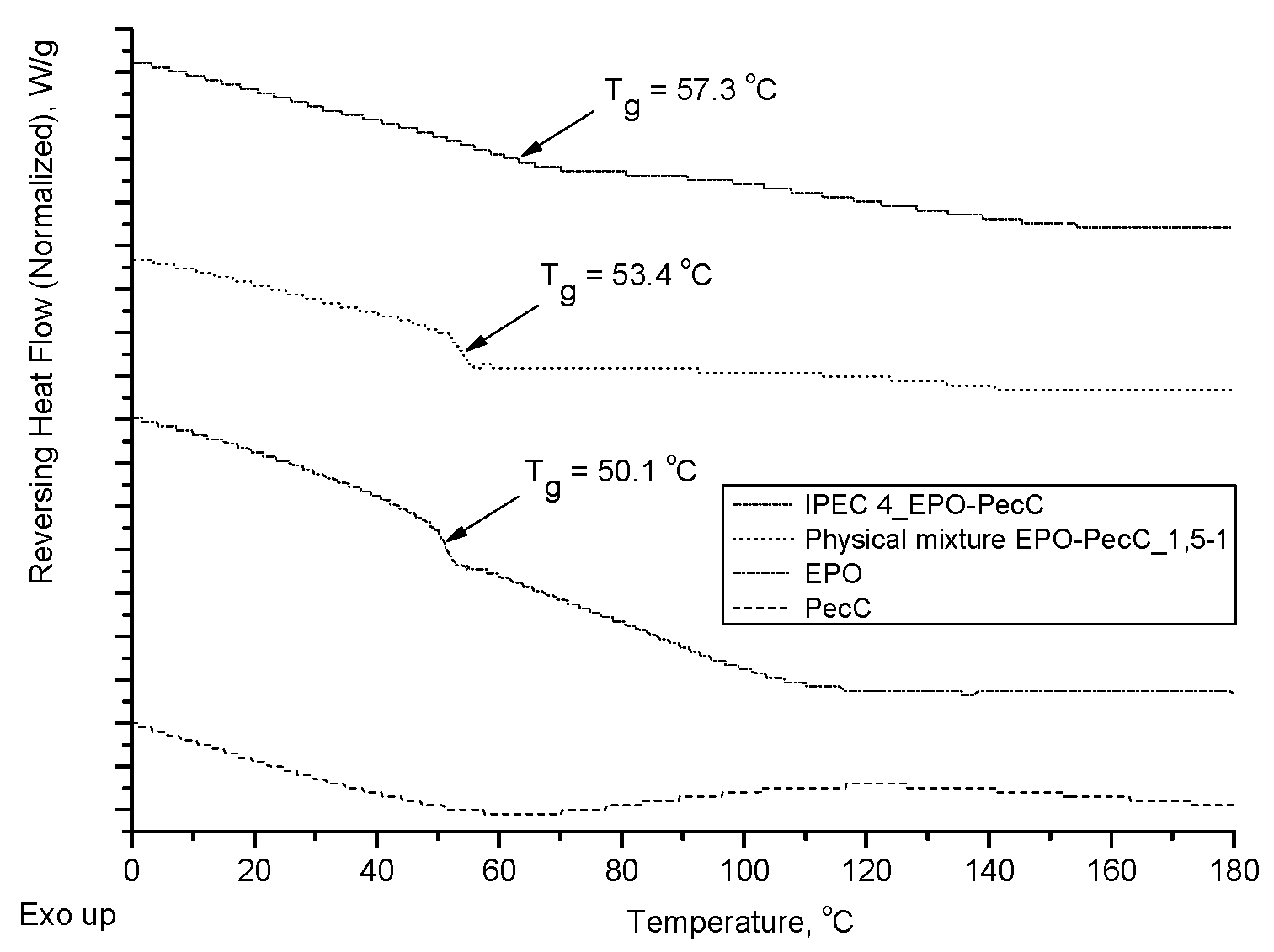

2.5. Thermal analysis

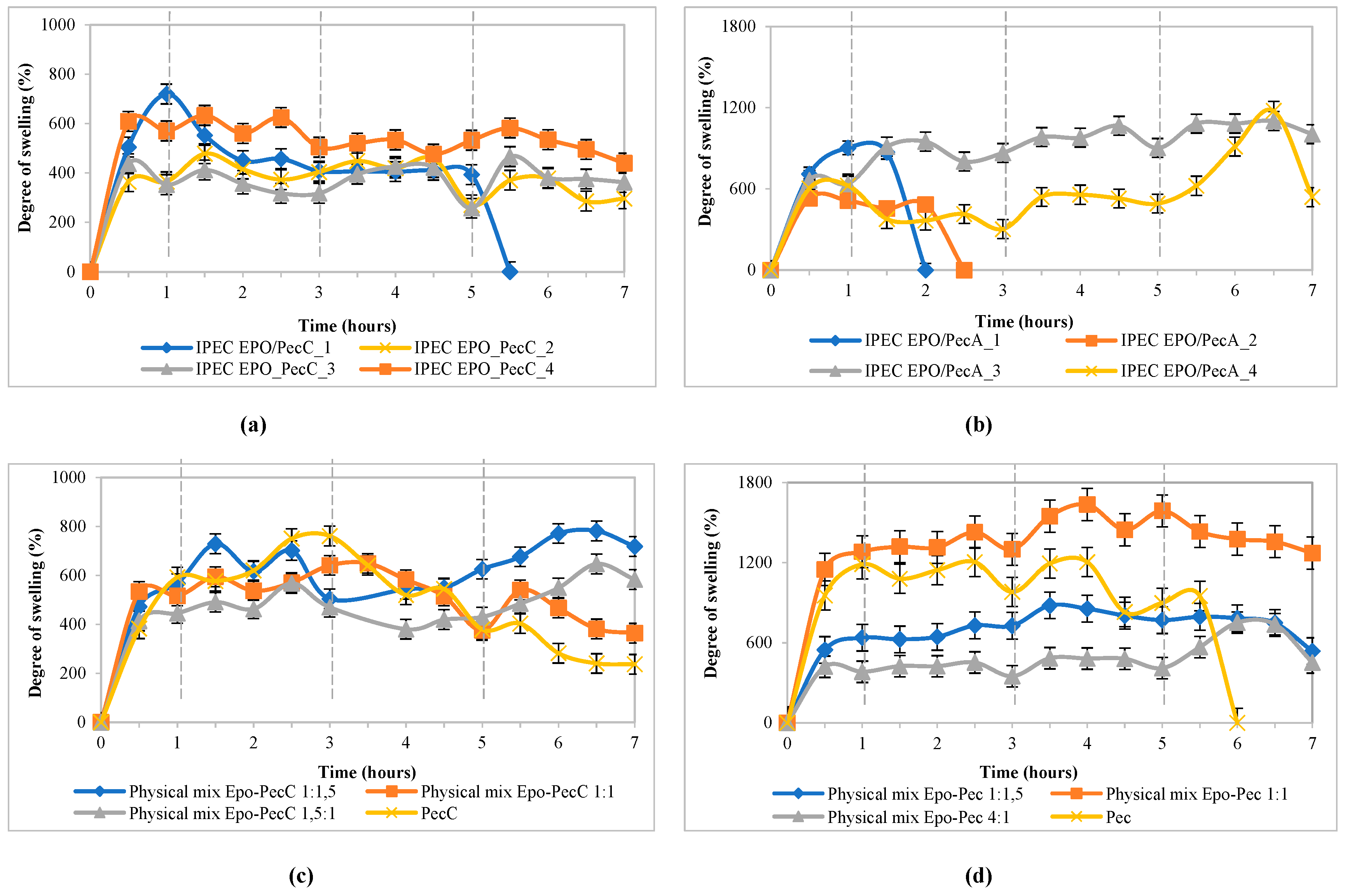

2.6. Determination of the degree of swelling of matrices

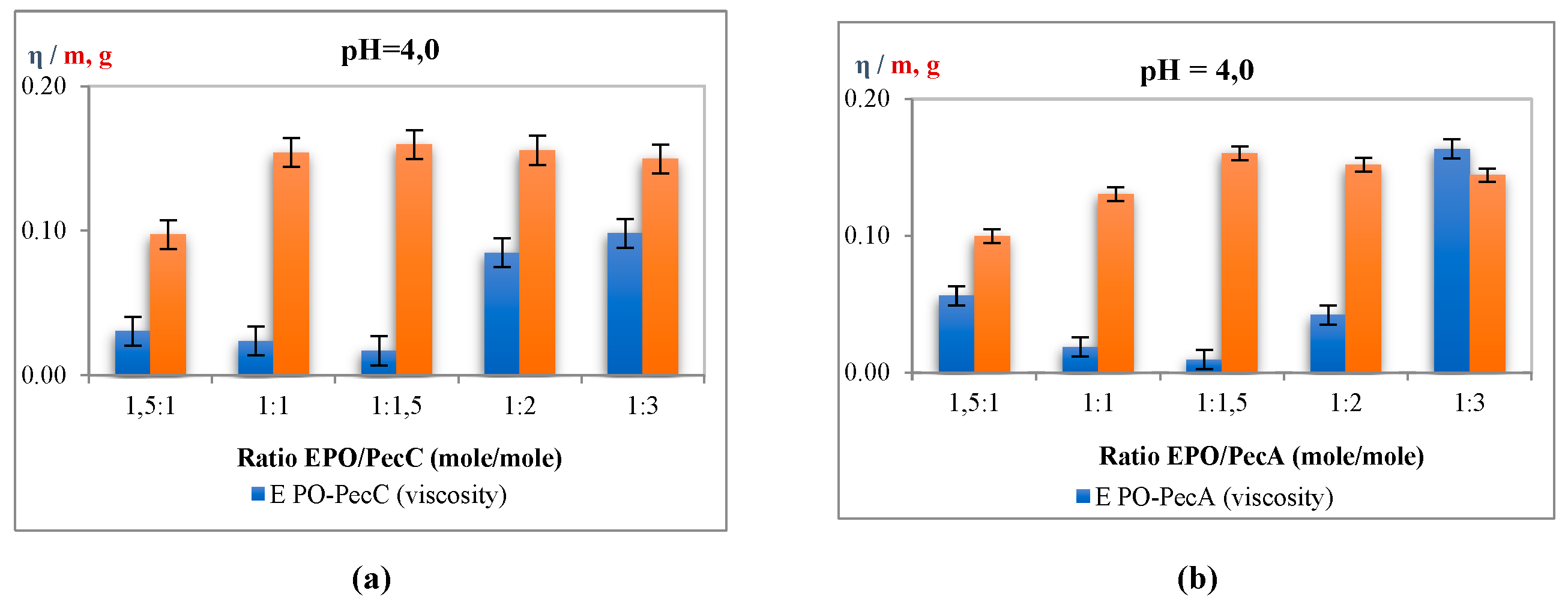

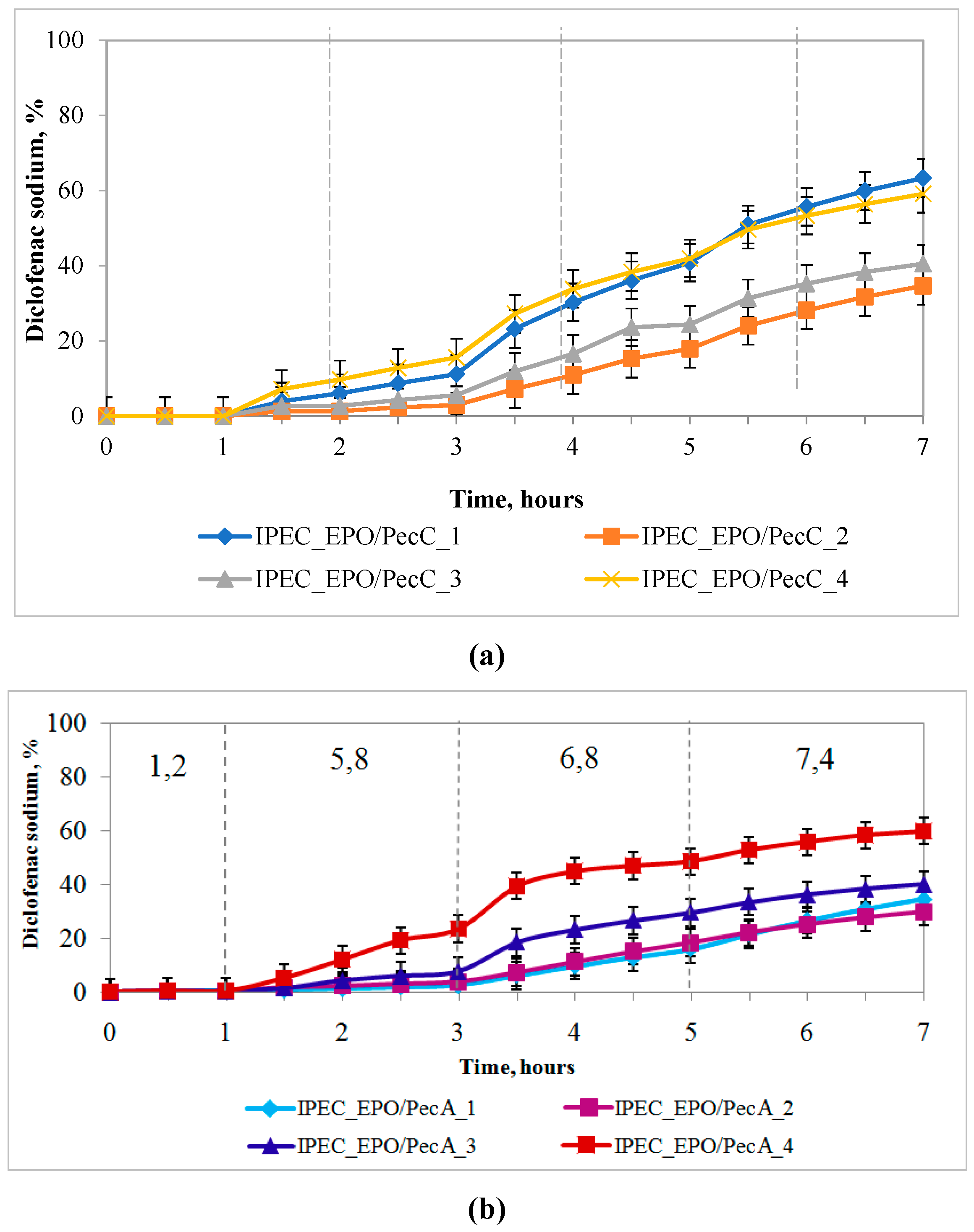

2.7. In Vitro Drug Release Test

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

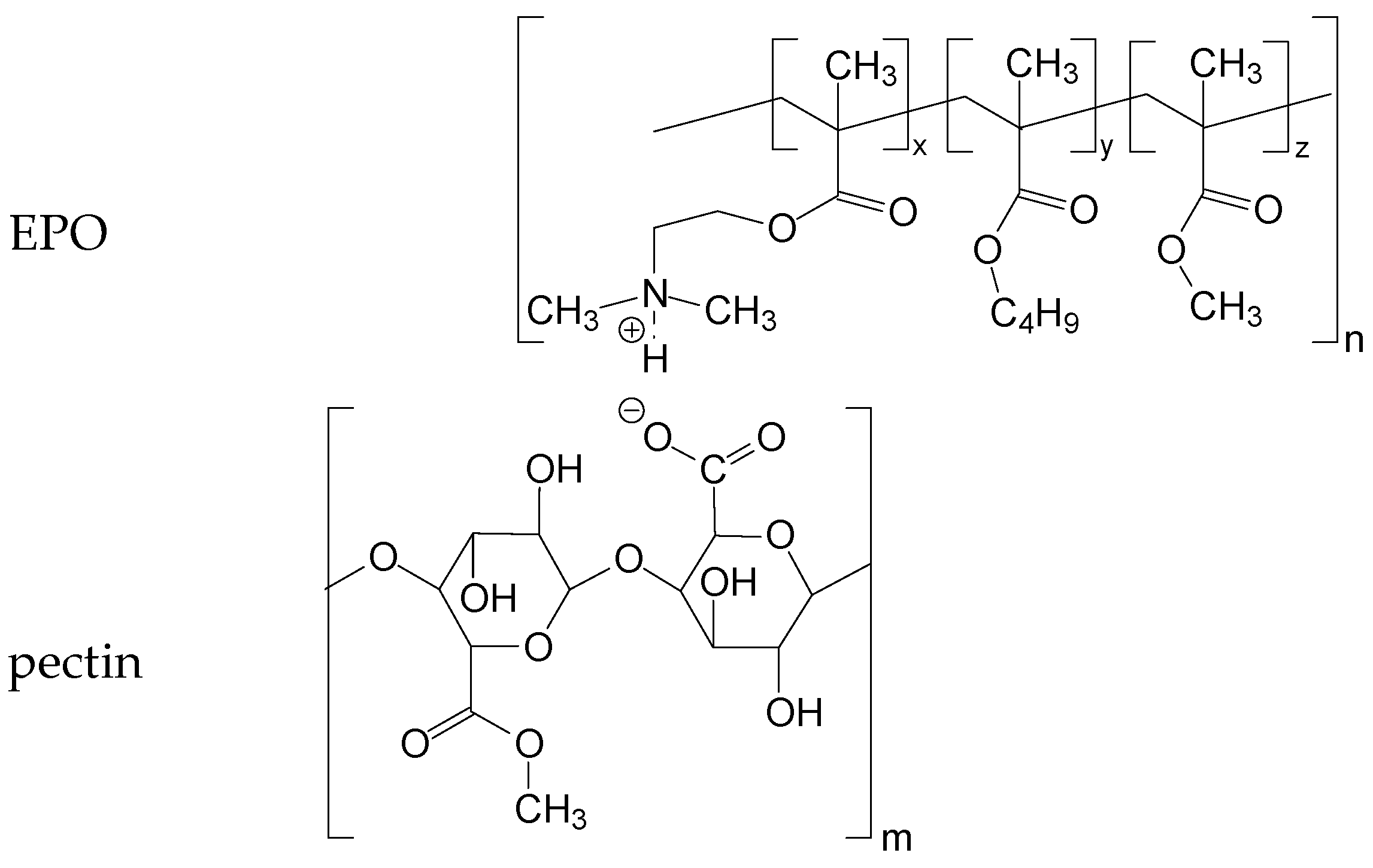

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Turbidity measurements

4.2.2. Apparent viscosity measurements

| where: | ||

| η | – | relative viscosity of the solution; |

| τ | – | solution outflow time, sec; |

| τ0 | – | solvent flow time, sec. |

4.2.3. Gravimetry

4.2.4. Synthesis of solid IPEC

4.2.5. Elementary analyses

4.2.6. FT-IR spectroscopy

4.2.7. Thermal analysis

4.2.8. Preparation of tablets

4.2.9. Determination of the degree of swelling of matrices

4.2.10. In Vitro Drug Release Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sriamornsak, P. Review. Application of pectin in oral drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2011, 8, 1009–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigucci, F.; Luppi, B.; Cerchiara, T.; Sorrenti, M.; Bettinetti, G.; Rodrigueza, L.; Zecchi, V. Chitosan/pectin polyelectrolyte complexes: Selection of suitable preparative conditions for colon-specific delivery of vancomycin. Eur. J Pharm Sci 2008, 35, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigucci, F.; Luppi, B.; Monaco, L.; Cerchiara, T.; Zecchi, V. Pectin-based microspheres for colon-specific delivery of vancomycin. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009, 61, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T. W.; Colombo, G. and Sonvico, F. Pectin Matrix as Oral Drug Delivery Vehicle for Colon Cancer Treatment. Review Article. AAPS PharmSciTech 2011, 12, No.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liua, L.S.; Fishmana, M. L.; Kostb, J.; Hicks, K.B. Pectin-based systems for colon-specific drug delivery via oral route. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3333–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, V.R.; Kumria, R. Polysaccharides in colon-specific drug delivery. Int. J. of Pharmaceutics 2001, 224, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martau, G.A.; Mihai, M. and Vodnar, D.C. The Use of Chitosan, Alginate, and Pectin in the Biomedical and Food Sector – Biocompatibility, Bioadhesiveness, and Biodegradability. Polymers 2019, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Z. Polysaccharides-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2008, 14, 60(15), 1650–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.M. P.; Coimbra, J.S.R.; Souza, V.G.L. and Sousa, R.C.S. Structure and Applications of Pectin in Food, Biomedical, and Pharmaceutical Industry: A Review. Coatings 2021, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Lamoza, M. L, Remunan-Lopez, C.; Vila-Jato, J.; Alonso, M.J. Design of microencapsulated chitosan microspheres for colonic drug delivery. J Control Release. 1998, 52, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, P.B.V.; Choonara, Y.E.; du Toit, L. C.; Ndesendo, V.M.K. and Kumar, P. Research Article. A Composite Polyelectrolytic Matrix for Controlled Oral Drug Delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2011, 12, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, H.J.; Matulewicz, M.C.; Bonelli, P.; Cukierman, A.L. Preparation and characterization of a novel starch-based interpolyelectrolyte complex as matrix for controlled drug release, Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, H.J.; Matulewicz, M.C.; Bonelli, P.; Cukierman, A.L. Preparation and characterization of controlled release matrices based on novel seaweed interpolyelectrolyte complexes. Int J Pharm. 2012, 429, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, A.; Navaee, K.; Oskoui, M.; Bayati, K.; Rafiee-Tehrani, M. Preparation and characterization of free mixed-film of pectin/chitosan/Eudragit RS intended for sigmoidal drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2007, 67, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norcino, L.B.; de Oliveira, J.E.; Moreira, F.K.V.; Marconcini, J.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Rheological and thermo-mechanical evaluation of bio-based chitosan/ pectin blends with tunable ionic cross-linking, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 1817–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiorth, M.; Tho, I.; Sande, S.A. The formation and permeability of drugs across free pectin and chitosan films prepared by a spraying method. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2003, 56, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Hervás, M.J.; Fell, J.T. Pectin/chitosan mixtures as coatings for colon-specific drug delivery: an in vitro evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 1998, 169, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshali, M.M.; Gabr, K.E. Effect of interpolymer complex formation of chitosan with pectin or acacia on the release behaviour of chlorpromazine HCl. Int. J. Pharm. 1993, 89, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, G.S.; Collett, J.H.; Fell, J.T. The potential use of mixed films of pectin, chitosan and HPMC for bimodal drug release. J. Control. Release 1999, 58, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwuluka, N.C.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kumar, P.; Modi, G.; du Toit, L.C.; Pillay, V. A Hybrid Methacrylate-Sodium Carboxymethylcellulose Interpolyelectrolyte Complex: Rheometry and in Silico Disposition for Controlled Drug Release. Materials 2013, 6, 4284–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwuluka, N.C.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kumar, P.; du Toit, L.C.; Modi, G.; Pillay, V. A Co-blended Locust Bean Gum and Polymethacrylate-NaCMC Matrix to Achieve Zero-Order Release via Hydro-Erosive Modulation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2015, 16(6), 1377–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, V.R.; Kumria, R. Microbially triggered drug delivery to the colon. Europ. J. of Pharm. Sciences 2003, 18, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semde, R.; Amighi, K.; Pierre, D.; Devleeschouwer, M.J.; Moes, A.J. Leaching of pectin from mixed pectin/insoluble polymer films intended for colonic drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 1998, 174, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semde, R.; Amighi, K.; Michel, J.; Devleeschouwer, M.J.; Moes, A.J. Effect of pectinolytic enzymes on the theophylline release from pellets coated with water insoluble polymers containing pectin HM or calcium pectinate. Int. J. Pharm. 2000, 197, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori-Kwakye, K.; Fell, J.T. Leaching of pectin from mixed films containing pectin, chitosan and HPMC intended for biphasic drug delivery. Int J of Pharmaceutics 2003, 250, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vildanova, R.R.; Petrova, S.F.; Kolesov, S.V.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Biodegradable Hydrogels Based on Chitosan and Pectin for Cisplatin Delivery. Gels 2023, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafin, R.I. Interpolymer combinations of chemically complementary grades of Eudragit copolymers: A new direction in the design of peroral solid dosage forms of drug delivery systems with controlled release (review). Pharm. Chem. J. 2011, 45, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafine, R.I.; Zakharov, I.M. Diffusion transport properties of polymeric complex matrix systems based on Eudragit and sodium alginate. Pharm Chem J. 2004, 38, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafine, R.I.; Kemenova, V.A.; Van den Mooter, G. Characteristics of interpolyelectrolyte complexes of Eudragit E100 with sodium alginate. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 294, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafine, R.I.; Salachova, A.R.; Frolova, E.S.; Kemenova, V.A.; Van den Mooter, G. Interpolyelectrolyte complexes of Eudragit® E PO with sodium alginate as potential carriers for colonic drug delivery: monitoring of structural transformation and composition changes during swellability and release evaluating. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2009, 35(12), 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, H.J.; Matulewicz, M.C.; Bonelli, P.; Cukierman, A.L. Basic butylated methacrylate copolymer/kappa-carrageenan interpolyelectrolyte complex: Preparation, characterization and drug release behaviour, Eur. J. Pharm Biopharm. 2008, 70, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.H.; Prado, H.J.; Rodríguez, M.C.; Michetti, K.; Leonardi, P.I.; Matulewicz, M.C. Carrageenans from Sarcothalia crispata and Gigartina skottsbergii: Structural Analysis and Interpolyelectrolyte Complex Formation for Drug Controlled Release. Mar. Biotechnol. 2018, 20, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sester, C.; Ofridam, F.; Lebaz, N.; Gagnière, E.; Mangin, D.; Elaissari, A. pH-Sensitive methacrylic acid–methyl methacrylate copolymer Eudragit L100 and dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate, butyl methacrylate, and methyl methacrylate tri-copolymer Eudragit E100. Polym.Adv.Technol. 2020, 31, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcíaa, M.C. , Martinellic, M.; Ponced, N.E.; Sanmarcoe, L.M.; Aokie, M.P.; Rubén H. Manzo, R.H.; Jimenez-Kairuz, A.F. Multi-kinetic release of benznidazole-loaded multiparticulate drug delivery systems based on polymethacrylate interpolyelectrolyte complexes. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 2018, 120, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwuluka, N.C.; Choonara, Y.E.; Modi, G.; du Toit, L.C.; Kumar, P.; Ndesendo, V.M.K.; Pillay, V. Design of an Interpolyelectrolyte Gastroretentive Matrix for the Site-Specific Zero-Order Delivery of Levodopa in Parkinson’s Disease. AAPS PharmSciTech 2013, 14, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmoro, A.; Sitenkov, A.Y.; Cascone, S.; Lamberti, G.; Barba, A.A.; Moustafine, R.I. Hydrophilic drug encapsulation in shell-core microcarriers by two stage polyelectrolyte complexation method. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 518, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmoro, A.; Sitenkov, A.Y.; Lamberti, G.; Barba, A.A.; Moustafine, R.I. Ultrasonic atomization and polyelectrolyte complexation to produce gastroresistant shell–core microparticles. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafine, R.I.; Sitenkov, A.Y.; Bukhovets, A.V.; Nasibullin, S.F.; Appeltans, B.; Kabanova, T.V.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V.; Van den Mooter, G. Indomethacin-containing interpolyelectrolyte complexes based on Eudragit1 E PO/S 100 copolymers as a novel drug delivery system. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 524, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafine, R.I.; Margulis, E.B.; Sibgatullina, L.F.; Kemenova, V.A.; Van den Mooter, G. Comparative evaluation of interpolyelectrolyte complexes of chitosan with Eudragit® L100 and Eudragit® L100-55 as potential carriers for oral controlled drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 70, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusif, R.M.; Hashim, I.I.A.; El-Dahan, M.S. Some variables affecting the characteristics of Eudragit E-sodium alginate polyelectrolyte complex as a tablet matrix for diltiazem hydrochloride. Acta Pharm 2014, 64, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunawattanakul, W.; Jaipakdee, N.; Rongthong, T.; Chansri, N.; Srisuk, P.; Chitropas, P.; Pongjanyakul, T. Sodium Alginate-Quaternary Polymethacrylate Composites: Characterization of Dispersions and Calcium Ion Cross-Linked Gel Beads. Gels 2022, 8, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Mooter, G. Colon drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2006, 3, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsmeyer, R.W.; Gurny, R.; Docler, E.; Buri, P.; Peppas, N. Mechanism of solute release from porous hydrophilic polymers. Int J Pharm. 1983, 15, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pH | ЕРО/РecC (mole/mole) | EРО/РecA (mole/mole) |

|---|---|---|

| 4,0 | 1 : 1,74 | 1 : 1,8 |

| 5,0 | 1 : 1,41 | 1 : 1,67 |

| 6,0 | 1 : 1,35 | 1 : 1,38 |

| 7,0 | 1,4: 1 | 1,78 : 1 |

| Sample symbol | Molar ration of polymers EPO/Pec | pH at which IPEC was obtained |

|---|---|---|

| IPEC EPO/PecC_1 | 1:1.5 | 4.0 |

| IPEC EPO/PecC_2 | 1:1 | 5.0 |

| IPEC EPO/PecC_3 | 1:1 | 6.0 |

| IPEC EPO/PecC_4 | 1.5:1 | 7.0 |

| IPEC EPO/PecА_1 | 1:1.5 | 4.0 |

| IPEC EPO/PecА_2 | 1:1.5 | 5.0 |

| IPEC EPO/PecА_3 | 1:1 | 6.0 |

| IPEC EPO/PecА_4 | 4:1 | 7.0 |

| Parameters | IPEC_EPO/PecC_1 | IPEC_EPO/PecC_2 | IPEC_EPO/PecC_3 | IPEC_EPO/PecC_4 |

| Exponential release (n) | 14.032±1.849 | 4.762±0.751 | 8.415±0.908 | 16.366±1.637 |

| Constant release (k) | 0.766±0.064 | 1.032±0.074 | 0.818±0.052 | 0.658±0.049 |

| Correlation coefficient (R2) | 0.93828 | 0.95789 | 0.96337 | 0.94553 |

| Transport mechanism | Super Case II | Super Case II | Super Case II | Super Case II |

| IPEC_EPO/PecA_1 | IPEC_EPO/PecA_2 | IPEC_EPO/PecA_3 | IPEC_EPO/PecA_4 | |

| Exponential release (n) | 0.526±0.123 | 0.819±0.178 | 2.612±0.632 | 5.149±0.808 |

| Constant release (k) | 2.186±0.129 | 1.884±0.122 | 1.453±0.139 | 1.287±0.091 |

| Correlation coefficient (R2) | 0.98515 | 0.98119 | 0.9588 | 0.97361 |

| Transport mechanism | Anomalous transport | Anomalous transport | Super Case II | Super Case II |

| Mixing order | Polymer ratio | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPO/PecC(or PecA)* | 9:1 | 8:2 | 7:3 | 6:4 | 5:5 | 4:6 | 3:7 | 2:8 | 1:9 |

| PecC(or PecA)/EPO* | 9:1 | 8:2 | 7:3 | 6:4 | 5:5 | 4:6 | 3:7 | 2:8 | 1:9 |

| Molar ratio EPO/ PecС(or PecA) | ||||||||||||

| 6:1 | 5:1 | 4:1 | 3:1 | 2:1 | 1,5:1 | 1:1 | 1:1,5 | 1:2 | 1:3 | 1:4 | 1:5 | 1:6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).