1. Introduction

The nuanced interrelation between sustainable tourism and environmental conservation has become a cardinal focus in contemporary research, driven by the escalating need to harmonize the economic benefits of tourism with ecological preservation [

1,

2,

3]. Within this context, the concept of ‘carrying capacity’ emerges as a pivotal construct, explicating the optimum number of visitors that a tourist site can accommodate without inflicting irreversible damage on the ecological, social, and economic environments [

1,

4]. This study situates itself within the multifaceted realms of sustainable tourism development in Kazakhstan, particularly focusing on the ecosystems of Katon-Karagay National Park (KKNP).

The importance of this research is underscored by the burgeoning tourism sector in Kazakhstan, particularly the sector of ecotourism and agritourism, which have been identified as significant contributors to regional sustainability, income, and cultural enrichment in the country [

3,

5]. The meticulous exploration of carrying capacity in these diverse tourism sectors provides profound insights into the sustainable management and development of these sectors, ensuring the balance between visitor satisfaction, environmental conservation, and economic imperatives.

The field of sustainable tourism has witnessed a plethora of studies and key publications, delving into the intricate dynamics between visitor perceptions, overcrowding, environmental conservation, and socio-economic development [

6,

7,

8]. However, the application and assessment of carrying capacity within Kazakhstan’s unique ecosystems, such as KKNP, present an uncharted territory in existing literature, necessitating a nuanced exploration to understand the intricate interplay of diverse factors affecting sustainable tourism development in the region.

Moreover, several diverging statements and controversial discussions permeate the field, particularly concerning the longitudinal relationships between changing visitor characteristics, behaviors, regulatory standards, and perceptions of overcrowding, highlighting the dynamic nature of carrying capacity assessments [

1,

9]. These ongoing debates necessitate a continuous and context-specific evaluation of carrying capacity to align the development strategies with evolving norms and perceptions within the realm of sustainable tourism.

The main aim of this work is to meticulously assess and calculate the tourism carrying capacity (TCC) on tourist routes and trails of KKNP, shedding light on the myriad of factors affecting it and providing a comprehensive framework for sustainable tourism development within the park. The principal conclusions drawn from this study underscore the indispensability of a holistic understanding of carrying capacity in fostering sustainable practices, ecological conservation, and socio-economic development, thereby contributing substantively to the broader discourse on sustainable tourism in protected areas.

This study seeks to provide a coherent overview of the evolving field of sustainable tourism and its multifarious interactions with carrying capacity, while ensuring the comprehensibility of the complex themes discussed, to a diverse scientific audience. The focused exploration of carrying capacity within Kazakhstan’s unique ecosystems offers invaluable insights into the sustainable development and management of tourism sectors, paving the way for harmonious integration of economic, ecological, and socio-cultural dimensions within the broader context of sustainable tourism development.

2. Research Area

Katon-Karagay National Park stands as Kazakhstan's largest park, established in 2001. Spanning an area of over 643,000 hectares, the park boasts a diverse array of flora and fauna, some of which are recognized as endangered and are listed in the Red Book. The park holds the distinction of being recognized as (1) a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (2014) and (2) a Transboundary UNESCO Biosphere Reserve “Greater Altai” (2017). The primary objective behind the park's establishment is the conservation and restoration of the unique natural complexes of Southern Altai, which hold significant ecological, scientific, cultural, and recreational value. Among its highlighted attractions, which have been designated as state monuments, are the “Rakhmanov Springs” mountain resort, Belukha Mountain, Kokkol Waterfall, and Berel burial mounds. The park's core activities encompass biological conservation, investigation of natural processes and phenomena, organizing informative tours, and fostering ecological enlightenment among both the local populace and visitors of the East Kazakhstan region.

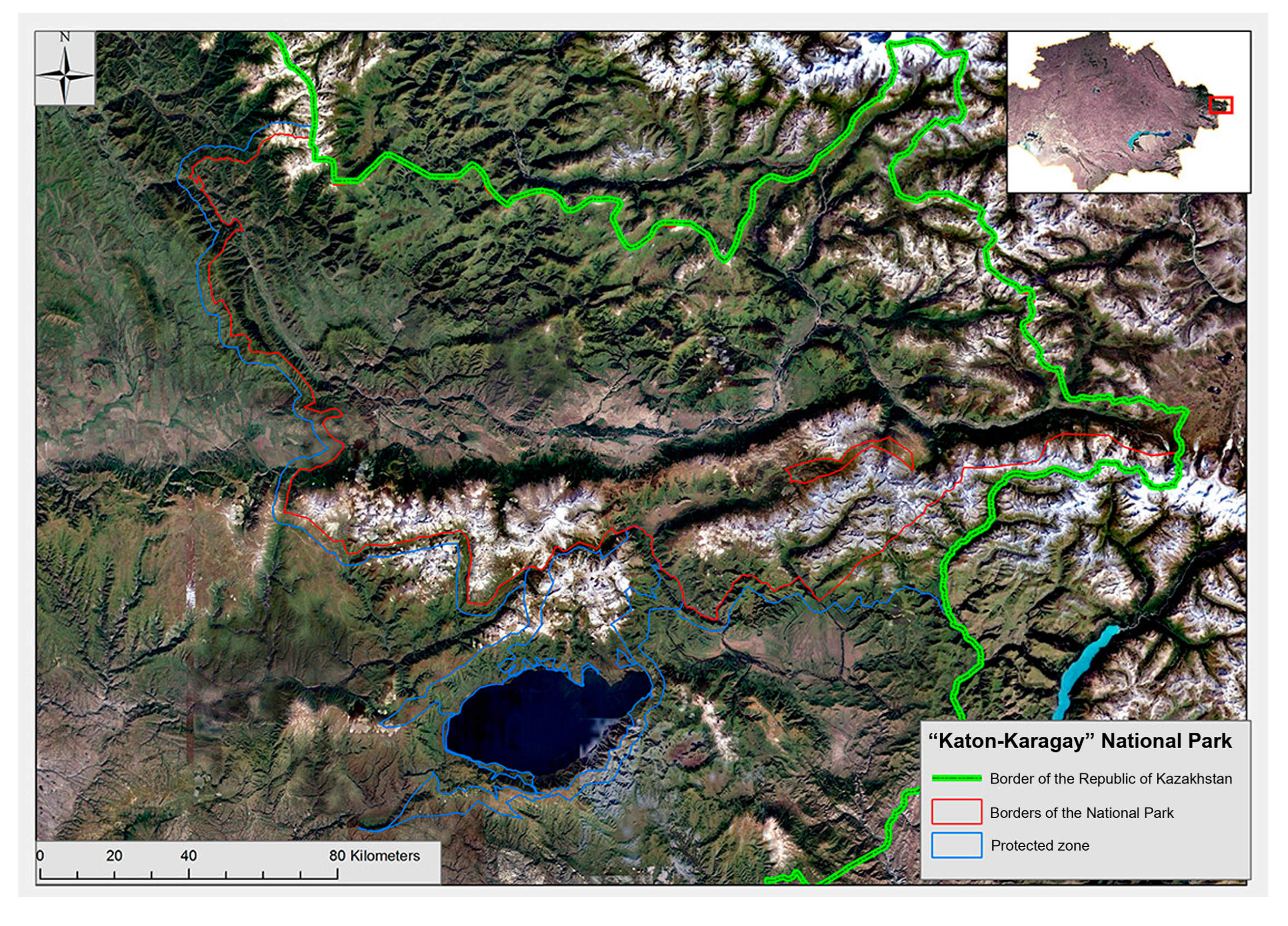

The national nature park is situated in the East Kazakhstan region within the Katon-Karagay district. It stretches across the Southern Altai, a mountainous terrain interlaced with numerous ridges, often rising above 3,000 meters above sea level. The park includes the southern macro-slopes of the Listvyaga and Katun ridges (southern and eastern slopes of the Belukha Mountain node), the western part of the Ukok high-altitude plateau within Kazakhstan's borders, and the ridges of Southern Altai, Tarbagatay (Altai), and Sarymsakty (see

Figure 1).

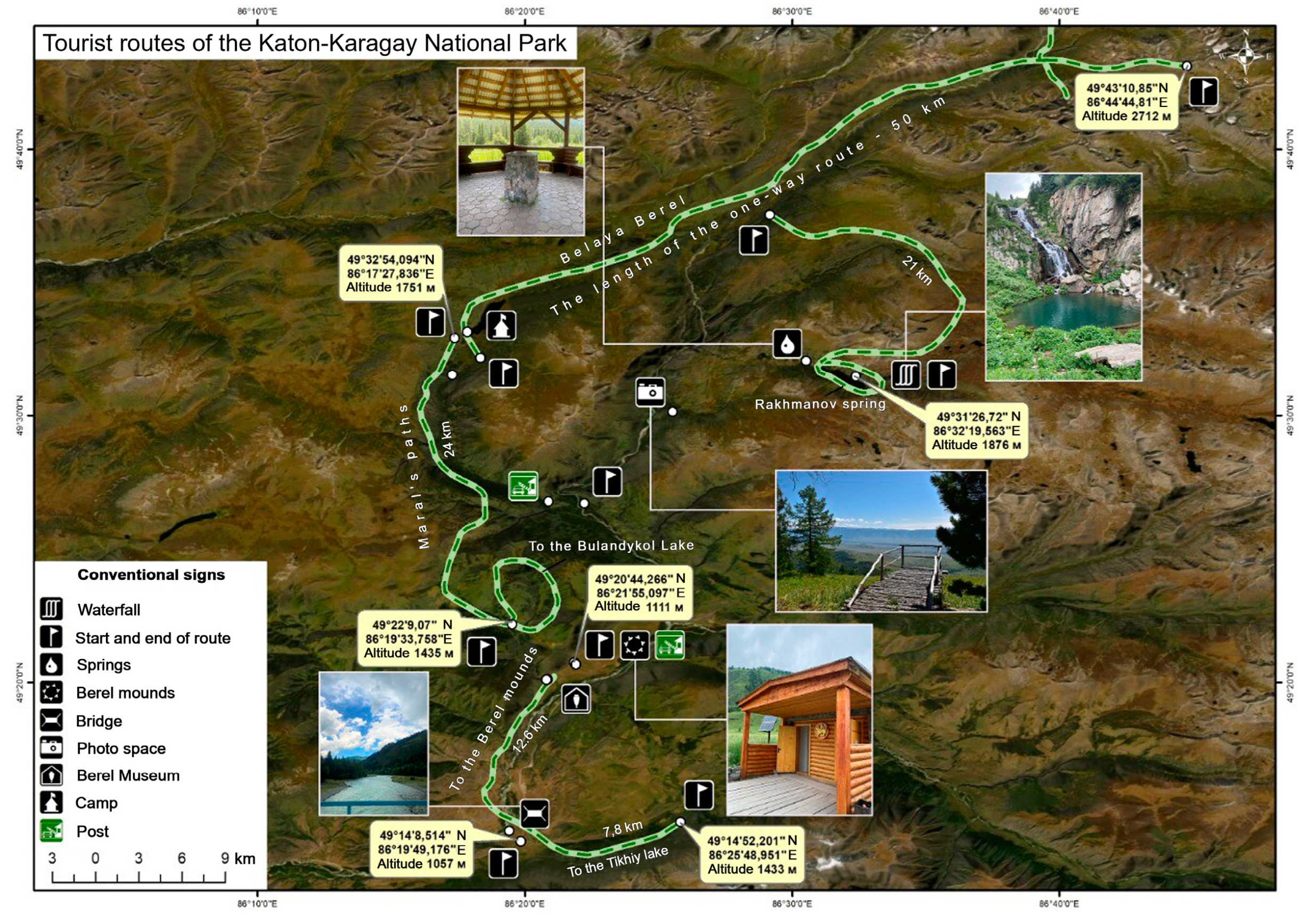

As part of the research conducted in KKNP, we examined 10 approved tourist routes and 4 excursion educational trails (July, 2022), including existing infrastructure objects (see

Figure 2). Specifically, these routes are: 1 – “Belaya Berel”; 2 – “Altai Paths”; 3 – “Ozerniy”; 4 – “Maral Paths”; 5 – “To the Tikhiy Lake”; 6 – “To the Bulandykol Lake”; 7 – “Exploring Native Land”; 8 – “To the Berel Burial Mounds”; 9 – “Sarymsakty”, 10 – educational trail “Rakhmanov Springs”, 11 – “Tasshoky”, 12 – “Irek”, 13 – “Forest Roads”, 14 – “Berkutaul”. The total declared length of these routes and trails amounts to 673 km, of which horseback routes comprise 333 km, hiking routes 240 km, and automobile routes 100 km. The operational scheme, in coordination with the national park's tourism department, envisioned the sequential processing of routes branch-wise from West to East.

On these routes and trails, primary data was collected to calculate the standards for maximum permissible loads, as well as to develop recommendations.

Overall, the routes' condition appears satisfactory, and no visual signs of exceeding the load are observed (except possibly during “peak” days at Lake Yazevoye, where the active part of the “Belaya Berel” route begins). Given the positive dynamics of tourist inflows, a rapid increase in tourist load on the national park's territory is anticipated (see Table 1). It's also vital to account for the role of tourism enterprises, both within and outside the East Kazakhstan region. According to official statistics (2022), the region has 78 tourist companies (29 tour operators and 49 travel agents), besides several facilities and services available in the Katon-Karagay district.

Table 1.

Dynamics of Tourism Development Indicators for 2020-2022.

Table 1.

Dynamics of Tourism Development Indicators for 2020-2022.

| Name of indicator |

Unit of measurement |

Years |

| 2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| Increase in the number of visitors served by domestic tourism accommodations (residents), compared to the previous year, % |

People (%) |

1,747 |

2,350 (134.5 %) |

3,555 (151.2%) |

| Increase in the number of visitors served by inbound tourism accommodations, compared to the previous year, % |

People (%) |

- |

50 |

58 (116,0%) |

| Increase in the number of presented bed days, compared to the previous year, % |

People (%) |

3,433 |

3,690 (107.4%) |

5,599 (151.7%) |

Analyzing the statistical data presented in Table 2, it is evident that four main areas of the national park experience significant tourist loads: the Rahman Springs, the Austrian Road, Yazevoye Lake, and the Bukhtarma River. Two other tour routes – Sarymsakty and Lake Maral – are gaining popularity. However, it should be noted that many routes share common sections (for example, Lake Yazevoye is the starting part of the “Belaya Berel” trail and the endpoint of the “By Maral Paths” route. The “Through Altai Paths” route largely overlaps with the “Belaya Berel” eco-trail, etc.).

Table 2.

Number of tourists by year, people (according to the data of Katon-Karagay National Park).

Table 2.

Number of tourists by year, people (according to the data of Katon-Karagay National Park).

| Name of tourist route / trail |

Years |

| 2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| Rakhmanov Springs |

2,470 |

2,486 |

1,997 |

1,279 |

| Austrian Road |

108 |

150 |

328 |

757 |

| Yazevoye Lake |

418 |

448 |

484 |

706 |

| Bukhtarma River |

85 |

117 |

284 |

483 |

| Sarymsakty |

46 |

82 |

86 |

113 |

| Maral |

38 |

27 |

143 |

98 |

| Listvyaga |

26 |

0 |

24 |

78 |

| Belaya Berel, Belukha |

89 |

76 |

81 |

73 |

| Berkutaul |

107 |

14 |

55 |

17 |

| Berel Burial Mounds |

23 |

15 |

8 |

13 |

| Tikhiy Lake |

57 |

0 |

16 |

11 |

| TOTAL |

3,410 |

3,415 |

3,506 |

3,628 |

3. Literature Review

The burgeoning significance of sustainable tourism underscores the imperative need for nuanced approaches to mitigate the conflict between conservation and tourism utilization, enabling a synthesis between ecological preservation and economic progression. A series of studies offer diverse perspectives on and methodologies for analyzing TCC, providing a rich tableau of insights applicable to the context of KKNP.

The increasing significance of sustainable tourism models is evident, especially in protected areas like Vesuvius National Park, where natural and cultural resources balance against socio-economic needs, underscoring the relevance of assessing tourism impacts through concepts like TCC [

10]. Similarly, assessing the limit of tourist loads in natural spaces, such as the beaches of Tulum National Park, is crucial due to the multifaceted environmental impacts of tourism [

11]. While understanding these limits is essential, the concept of Recreational carrying capacity (RCC) lacks a clear consensus. Traditional measures often fixate on social and physical capacities, but Wang et al. [

12] highlight the need for a broader framework, encompassing factors like the environment, economy, and culture. This multi-faceted view is evident in studies like that of Hangzhou Xixi National Wetland Park, where ecological, spatial, facility, management, and psychological carrying capacities were all considered [

13].

Ecotourism, despite its potential benefits, risks degrading natural resources without proper management. Assessing the carrying capacity can ensure sustainable visitation levels, as demonstrated by the study in La Tigra National Park [

14]. The interplay between marine resources' recovery and decreased tourism provides a compelling case for structured tourism management to ensure sustainability, further supported by policies proposed by Israngkura (2022) [

15]. While assessing carrying capacities, understanding visitor preferences and adjusting activities to ecological constraints is pivotal. Studies, such as the one at Pattunuang Assue Nature Tourism Site [

16], demonstrate varying capacities for different activities. Incorporating environmental considerations, the study at Dudhsagar Falls applies principles like Boulon's formula, congestion, and stakeholder views to refine carrying capacity analysis [

17].

Similarly, multi-criteria methods like the one used for the Lagunas de Montebello National Park [

18] and Monitoring System for Tourist Flow at the Table Mountains National Park [

19] offer holistic and real-time insights, critical for adaptive tourism management. Moreover, spatial distribution of visitor pressure, as highlighted by Kostopoulou & Kyritsis (2006) [

20], indicates that localized areas might experience environmental loads beyond their capacity, necessitating dynamic evaluation tools.

The essence of sustainable tourism revolves around the pivotal balance of tourism growth, its myriad impacts on the environment, economy, and societal structures, and how adept destination management, encompassing multi-sectoral participation, can establish a favorable long-term tourism ecosystem [

21]. Such balanced growth is especially vital in areas like Rawa Kalibayem, poised for ecotourism development, where the implementation of rigorous throughput studies can illuminate the region’s capacity to sustain tourism without compromising environmental quality [

22].

In the context of assessing TCC, the concept becomes a linchpin to moderate the trajectories of tourism development in coastal areas [

23]. This notion is further exemplified in the coastal area of the island of Milos, where the application of an integrated system of indicators encapsulating major components of TCC demonstrated the adaptability of the island to tourism pressures without exceeding its threshold in most aspects [

24]. Despite the apparent enormous ecological and cultural carrying capacities in regions like the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand, the glaring insufficiency in economic and institutional carrying capacities beckons for sustainable enhancements to attain balanced tourism development [

25]. This imbalance mirrors the broader conflict between economic growth propelled by the tourism industry and the exigent need for environmental conservation, necessitating systems like the Tourism Environmental Carrying Capacity System to reconcile this dichotomy by adapting tourism activities and facilities to the preservation of natural resources [

26].

The necessity of detailed evaluations and multifaceted methodologies is further emphasized by studies conducted in areas such as the region of Sardinia, where a social accounting matrix elucidated the economic and environmental repercussions of tourism, highlighting the interdependence between sustainable tourism policies and the incorporation of multiple variables [

27]. The early warning indicator system, based on the state space model, focuses on nature, economy, and society, shedding light on the spatial and temporal variances of TCC in China's island cities, further emphasizing the relevance of diverse assessment methodologies [

28]. Further underlining the relevance of multidimensional assessment, studies have proposed various quantitative ecological methods to evaluate the TCC of vegetation, thus informing strategies for vegetation protection and ecological management in mountainous scenic areas like Mount Wutai [

29]. The gravity of community engagement is accentuated by the noticeable lack of trust and willingness of local authorities, posing a substantial hurdle in the realization of community engagement programs in many regions [

30].

TCC is an integral component in assessing how tourism affects environments, societies, and economies. This concept's main aim is to ensure sustainability, balancing tourists' utilization against the quality of the tourism environment. However, despite its centrality, there exists no universally accepted definition of TCC [

31]. TCC, when narrowly viewed as a mere numerical limit representing the saturation point of tourism, tends to be inadequate [

31]. In this context, some studies have argued for a shift from numerical TCC to understanding the “limits of acceptable change,” emphasizing the question of how much change is tolerable rather than the intensity of utilization [

31].

The ramifications of not understanding or correctly calculating TCC are evident. For instance, the tourism exploitation capacity in locations like Phuket, Thailand, was found to be overstretched, with significant threats to the area's recreational capacity [

32]. Similarly, impacts from tourism in Kibale National Park have increased with rising numbers of tourists, emphasizing the need for a forward-looking recreational capacity determination and impact assessments [

33]. This is reflected in Ile-Alatau Nature Park, where the estimated recreational capacity exceeded the actual average attendance, suggesting more room for sustainable tourism [

34].

Conceptualizing TCC is multifaceted. It includes physical, biological, social, cultural, and even psychological aspects of the tourism environment [

35]. While a holistic approach is necessary, the methods employed in assessing carrying capacity can sometimes impact the evaluation's accuracy, as seen in instances where the hierarchical process analysis did not consider indicators simultaneously [

36]. The move towards more inclusive and dynamic models, such as those which incorporate tourists' psychological experiences, offers a broader view of TCC [

37]. Additionally, models incorporating multiple dimensions of sustainable geotourism, like the environmental, socio-demographic, and political-economic capacities, provide more comprehensive insights [

38].

Regional nuances play a critical role. In the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomerations, the spatial differentiation and correlation of tourism ecological carrying capacity necessitated a scientific evaluation for the region's sustainable development [

39]. And in the Mediterranean, known as a prime tourist destination, there is an emphasis on balancing local economic development with protection of the physical, social, and cultural environments [

40]. Likewise, in U.S. national parks, there is a growing focus on understanding how human activity affects various conditions of the park, from economic to ecological [

31].

The application of TCC is further extended in areas of specialized interest. For instance, in the context of geoparks, such as the UNESCO Global Geopark in Hong Kong, TCC acts as a tool to reinforce governance principles, ensuring the geopark's sustainable use [

38]. Wetland parks, on the other hand, utilize TCC to balance protection with economic benefits, proposing measures like setting up protection zones and enhancing tourism values through biodiversity [

5,

41]). Advanced methodologies, such as the system dynamics modeling in Sanjiangyuan National Park, help forecast recreational capacities under various scenarios, providing data for efficient planning and management [

42]. Similarly, the Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) planning framework aids in practical implementation of sustainability concepts for regional tourism planning, as evidenced in Texas [

43]. This emphasis on planning and dynamic management underscores the importance of adapting TCC concepts to unique regional needs and contexts.

The meticulous analysis of carrying capacities is undeniably critical, as it serves to synchronize tourism development with ecological preservation, especially within protected areas like KKNP. Research indicates that the carrying capacity concept necessitates longitudinal study, given that visitor perceptions and compositions are subject to change, thus affecting perceived overcrowding and the resultant satisfaction levels [

3]. This perspective emphasizes that mere reliance on cross-sectional studies could yield inaccurate representations of carrying capacities, necessitating continuous monitoring to ensure alignment with the evolving norms and perceptions. While discussing the intricate fabric of carrying capacity, the role of tourism firms is pivotal, significantly contributing to the socio-economic tapestry of Kazakhstan. These firms amplify labor-intensive enterprises, reinforcing the economic imperative and ensuring equitable distribution of economic growth benefits within the country [

2]. This linkage reinforces the importance of scrutinizing the impact of these firms in the context of sustainable tourism, specifically focusing on employment ramifications in the region.

National parks are evidently integral for sustainable ecotourism in Kazakhstan, underscoring the importance of maintaining a delicate equilibrium between biodiversity conservation and regional sustainability [

9]. These protected areas are envisaged as the forefront of ecological conservation, thereby necessitating meticulous consideration of carrying capacities to facilitate balanced ecotourism development [

44].

In light of these studies, it becomes paramount for destinations like KKNP to adopt a comprehensive approach towards assessing and managing tourism carrying capacities. Integrating methodologies, considering multiple factors, and ensuring continuous monitoring will not only preserve the natural heritage but also promote sustainable socio-economic growth. This intricate interweaving of methodologies, economic considerations, ecological insights, and community engagement forms a rich tapestry of perspectives and approaches. The collective wisdom distilled from these studies elucidates the indispensability of comprehensive, integrative strategies in navigating the delicate balance between tourism development and environmental conservation, rendering these insights particularly germane to the trails and routes of KKNP. The application of these varied insights can facilitate the sculpting of sustainable tourism landscapes that harmonize economic development, ecological preservation, and societal well-being.

Understanding and accurately assessing TCC is paramount for ensuring sustainable tourism. As global travel continues to grow, regions and tourist destinations will increasingly need to adopt multifaceted and context-specific approaches to balance the benefits of tourism with its potential impacts. Such measures will protect and preserve the invaluable ecological, cultural, and socio-economic resources that these destinations offer.

Following the extensive literature review, a critical synthesis becomes pivotal. The vast array of insights, methodologies, and case examples from various sources shed light on the multifaceted nature of TCC and its intrinsic relationship with sustainable tourism. To streamline these diverse perspectives and offer a coherent snapshot, the subsequent table encapsulates the salient findings. This distillation juxtaposes each key insight with its direct relevance to the KKNP, providing a tailored roadmap for stakeholders. This structured consolidation serves as an anchor, bridging theoretical paradigms with pragmatic applications for the park, ensuring its sustainable trajectory in tourism management. Refer to the Table 3 below for a comprehensive synthesis of the insights from the literature review.

Table 3.

Synthesized Insights on TCC and Its Relevance for Sustainable Tourism.

Table 3.

Synthesized Insights on TCC and Its Relevance for Sustainable Tourism.

| Aspect |

Key Findings/Insights |

Relevance to Katon-Karagay National Park |

References |

| Sustainable Tourism Models |

|

Prioritizing sustainable tourism models ensures both conservation and regional economic growth within the park |

[10,11] |

| Visitor Dynamics |

|

Continuous monitoring captures evolving visitor dynamics and adapt park strategies accordingly |

[3] |

| Socio-economic Role of Tourism Firms |

Tourism firms in Kazakhstan significantly influence socio-economic dynamics, especially employment and income distribution |

Collaboration with tourism firms can amplify the park's socio-economic contributions to the region |

[2] |

| Ecotourism & National Parks |

National parks are central to ecotourism, balancing biodiversity conservation and regional sustainability |

Emphasis on strategies that harmonize conservation and development ensures the park remains a beacon for ecotourism |

[9] |

| Methodologies in TCC |

Multiple TCC assessment methods are discussed, including the “limits of acceptable change.” Models integrating various dimensions provide comprehensive insights. |

Adopting an integrated approach ensures holistic park development without compromising conservation objectives |

[31,36,37,38] |

| Regional Dynamics |

TCC challenges differ across regions, necessitating bespoke strategies. Context-specific approaches, like in the Yangtze River Delta, are pivotal |

Unique ecological, cultural, and socio-economic dynamics of the park necessitate tailored TCC strategies |

[39,40] |

| Ecotourism Impacts |

|

Proper management ensures sustainable ecotourism development and preservation of the park's natural heritage |

[14,15,31] |

| Advanced Techniques & Specialized Tourism |

|

Leveraging advanced methods and serving specialized tourism interests can position the park at the forefront of sustainable practices |

[38,41,42,43] |

| TCC in Specialized Contexts |

Geoparks and wetland parks use TCC to balance protection and economic benefits. The introduction of zones, like in Sanjiangyuan National Park, aids in forecasting capacities |

Consideration of specialized zones and tailored approaches for areas within the park can enhance sustainable tourism development |

[38,41,42] |

| Community Engagement |

|

Prioritizing local community involvement and addressing trust issues can lead to a holistic and inclusive tourism model for the park |

[30] |

| Regional Carrying Capacities |

|

Accurate TCC assessment ensures sustainable tourism development and avoids ecological degradation within the park |

[32,33,34] |

| Diverse Methodological Approaches |

Different methods of TCC evaluation are applied, considering variables like environment, economy, and society. Indicators and models help understand TCC's spatial and temporal variances |

Diverse methodological approaches can offer the park a nuanced understanding of its carrying capacities and the effects of tourism |

[27,28,29] |

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The foundation of this exploration is cemented on the empirical data, accrued during the fieldwork conducted within the boundaries of KKNP between July 1 and August 30, 2021-2022. The synthesis of this primary data elucidates the pivotal aspects of recreational loads on various tourist-excursion routes and eco-trails within the park. These data are synthesized considering the multifarious objective and subjective influencing factors, essential for deriving reliable results and formulating cogent recommendations for modulating tourist influx in coherence with established norms and strategic alignment of routes and trails.

This empirical collection embodies intricate specifications pertaining to the maximum permissible norms of recreational loads, grounded on a synergy of analytical insights into diverse environmental, ecological, and anthropogenic variables. The nuanced integration of these variables is imperative for engineering a methodical framework for sustainable tourism within the protected territory. The material utilized for this rigorous investigation is exclusive to the confines of KKNP, highlighting its novelty, as the computations and conclusions derived have been instantiated for the first time, with a focus on years marking the zenith of visitor attendance as per the park's records.

In addition to this primary information, a literature review was undertaken, which integrated seminal publications, scholarly articles, and official guiding documents. These literary materials provided a multifaceted perspective on the extant methodologies, theoretical postulates, and paradigms relative to the carrying capacity in protected regions. This congruence of literature review and primary data facilitated a multidimensional exploration into the interplay between ecological equilibrium, tourism dynamics, and socio-economic impacts. It also endowed the study with the capacity to validate and corroborate the empirical findings within the spectrum of pre-existing academic discourses and practical implementations.

The cumulative interaction of empirical findings from KKNP and the insights gleaned from the expansive literary review provisioned a nuanced understanding of the sustainability vectors and their influence on tourism management in protected areas. This coalescence of diverse data forms encapsulated the ecological consequences, infrastructural exigencies, and anthropogenic interventions within the park, enabling a nuanced depiction of the sustainable tourism narrative within the ecologically sensitive confines of the national park.

4.2. Methods

To assess the TCC in a sustainable context, this study systematically amalgamates both qualitative and quantitative data, bridging primary empirical data with scholarly precedents and literature in the field. The methodology adheres to the principles of ecological and social carrying capacities and integrates variegated analytical and calculative methods to elucidate the multidimensional aspects of recreational load within the protected areas, specifically focusing on KKNP.

The conceptual framework of this study is based on the carrying capacity, specifically focusing on ecological and tourist social carrying capacity, to determine the sustainable threshold of tourist attendance. The methodology utilized is multifold, incorporating calculated methods that factor in ecological impacts, psychocomfort approaches emphasizing tourist experiences, and monitoring approaches for observing critical environmental changes over time.

To precisely determine the allowable recreational load, the following basic formula is implemented:

Where:

Σt represents the natural TCC of the territory (people/ha).

Мload denotes the maximum load of the territory associated with the influence of anthropogenic factors (number of people).

Sarea is the total area of the territory under consideration (ha).

k, f, g, j, q are corrective correction factors accounting for the degree of eco-infrastructure development and the level of development of the territory.

Additionally, the methodology integrates the Lavery and Stanevi formula:

Where:

K is the maximum number of people per study area.

S is the total area of the territory (ha).

k is a correlation coefficient based on the sensitivity of the territory (for national parks – 1.0).

N is the normative area per person (for national parks – 0,12).

This approach allows for the consideration of varying capacities of different natural complexes and zones within the park, ensuring that the recreational load is congruent with the ecological sensibilities of each zone, such as quiet recreation, walking recreation, and active recreation, following the recommended background recreational loads of Kazakh forest management enterprise.

The psychocomfort approach is also incorporated, focusing on ensuring the absence of sound and visual contact between separate groups of tourists or excursionists. This approach utilizes coefficients to adjust the primary results in determining the recreational load, providing an anthropocentric perspective to the ecological considerations.

Moreover, the study engages in a meticulous monitoring approach, observing critical changes in the environment over time, which negatively affects the sustainability of ecosystems. This approach underscores the necessity of continuous assessment to address the ever-evolving nature of ecological and human interaction dynamics within protected areas.

During the specified fieldwork period within KKNP, all these methodological frameworks were meticulously applied to gather comprehensive and nuanced data. The empirical findings were complemented by extensive literature reviews, comparative analysis, and exclusive statistical data provided by the administration of the national park. The careful juxtaposition of varying methodological strands and the considered application of diverse calculations for different zones within the park contribute to a multifaceted understanding of the sustainable tourism narrative within protected areas.

The methodology herein, fortified by rigorous data synthesis and analytical discernment, serves to elevate the understanding of carrying capacities in tourist destinations, catering to both ecological preservation and enhancement of the tourist experience. By addressing the complexities inherent in sustainable tourism management, this methodological approach aids in fostering ecological resilience, economic viability, and social wellbeing within the ecosystems under study.

5. Results

5.1. Calculation of Permissible Recreational Loads in Katon-Karagay National Park

KKNP's diverse ecosystems necessitate an in-depth and meticulous approach to calculate permissible recreational loads. Using a combination of direct observations, literature reviews, and advanced modeling techniques, we derived specific load capacities for different areas within the park.

Table 1 offers a comprehensive breakdown of these calculated values, highlighting the distinct features and sensitivities of each zone. The data points considered in these calculations encompassed ecological, environmental, and social indicators, ensuring a holistic assessment.

The majority of open grassland areas, which predominantly comprise of the park's total land area, have a permissible load of up to 11 person/ha. These regions, characterized by hardy grasses and broad expanses, can accommodate a higher number of visitors without showing immediate signs of wear. The density was derived from factors such as vegetation resistance, the influx of local fauna, and the rate of regeneration after wear.

In contrast, wetland zones, crucial for avian biodiversity and acting as the park's natural water purifiers, have a markedly lower permissible recreational load at 3 person/ha. This is due to their sensitivity to disturbances and the essential ecosystem services they provide. The calculations considered the nesting patterns of bird species, the fragility of wetland plant species, and the water purification rates.

The various forested regions of the park had a varied range of permissible loads. Deciduous forests, particularly those of birch and aspen, which have a relatively faster rate of regeneration, have a permissible load ranging from 5-8 person/ha. The dense canopy, undergrowth, and robust soil structure in these forests allow for this moderate load.

Dark coniferous spruce forests, on the other hand, are a sensitive lot. These forests, integral for certain specialized fauna and hosting some of the park's oldest trees, have a permissible load of only 2-4 person/ha. The slower growth rate of spruce trees, coupled with the delicate forest floor ecosystem, warranted this conservative estimate.

Rocky and mountainous terrains, which offer some of the most breathtaking vistas of the park, have a permissible load of 7 person/ha. Though these areas are rugged, the calculation took into account the safety of visitors, the fragility of mountain flora, and potential soil erosion.

Lastly, regions marked for their security functions or categorized as fire hazards were consciously left out from these calculations. These zones, critical either for their biodiversity value or due to the risks they pose, are deemed non-negotiable for tourist interactions.

The calculated permissible loads offer a roadmap for authorities to design paths, resting areas, and facilities. They also provide a guideline for tourists, ensuring that their presence doesn't upset the delicate balance of Katon-Karagay's ecosystems (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Calculation of permissible recreational loads and TCC of ecosystems.

Table 4.

Calculation of permissible recreational loads and TCC of ecosystems.

| Natural/functional areas |

Coefficients |

| Permissible load, people/ha |

Monthly load, people/ha |

| Protection functions |

TCC is not calculated |

| Protected status |

0.7 |

0.9 |

| Cultural landscape |

0.6 |

0.7 |

| Ecological stabilization |

0.8 |

1.0 |

| Tourist and recreational activities |

0.5 |

0.7 |

| Limited economic activity |

0.4 |

0.6 |

| Recreational use regime |

0.07 |

0.26 |

| Accessibility |

2.10 |

7.80 |

| Fire hazard |

TCC is not calculated |

| Total for the national park |

9.90 |

5.2. Biological Norms of Permissible Recreational Loads

Within the KKNP, the delicate balance between preserving its vast biodiversity and facilitating tourism relies heavily on understanding the biological norms of permissible recreational loads. These norms serve as benchmarks, guiding the number of visitors a specific region within the park can sustain without compromising its ecological balance.

Various methodologies, including remote sensing, soil tests, and observational studies, were employed to derive these values. A significant part of this assessment focused on the diverse types of forests within the park, as they house a majority of the park's flora and fauna.

Starting with the deciduous forests of birch and aspen, the data pointed to a clear biological criterion ranging from 4-7 person/ha. This range can be attributed to these forests' dense canopy, which provides a natural shield against light disturbances and helps maintain soil moisture. However, the forest floor, with its rich humus, is sensitive to trampling, hence the upper limit of 7 person/ha.

Coniferous forests, predominantly comprising dark coniferous spruce, presented a different set of parameters. Due to the slow-growing nature of spruce and its importance in maintaining the region's microclimate, the permissible load was determined to be slightly lower, at 3-5 person/ha. This careful limitation ensures that the delicate moss-covered forest floor remains undisturbed, safeguarding the habitat of various small mammals and insects.

The mixed forests, combining both deciduous and coniferous trees, provided a slightly more flexible permissible range of 5-6 person/ha. The mixed nature of these forests means they benefit from the resilience of deciduous trees and the protective nature of conifers, giving them a balanced carrying capacity.

Next, the meadow forests, which are usually transitional zones between dense forests and open meadows, were assessed. Due to their relatively open canopy and robust grass-covered floor, they can sustain a higher load, estimated at 6-8 person/ha.

The methodology also incorporated a unique formula to calculate the one-time maximum permissible load for these forest landscapes. This formula factored in the zone of influence from expected “technogenic loads,” such as noise pollution from nearby roads or industrial zones, as well as the land area under “anthropogenic load” from visitors and infrastructural developments. The resultant calculation painted a clear picture: the average annual permissible one-time recreational load across all forest types was found to be 39.8 people. hour/ha.

In addition to the type of vegetation, the biological norms also accounted for other environmental variables, such as topographical features, soil moisture levels, and the area's susceptibility to forest fires. For instance, regions with a higher inclination or gradient were found to have a slightly reduced carrying capacity due to increased soil erosion risks.

These quantitative results play a pivotal role in defining tourism strategies for KKNP. Ensuring that the number of visitors stays within these permissible recreational loads is crucial to safeguard the park's rich biodiversity and ensure its sustainability for generations to come (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Biological norms of permissible recreational loads on natural complexes.

Table 5.

Biological norms of permissible recreational loads on natural complexes.

| Natural Complex |

Biological criterion, people/ha |

| Forest types: |

| For deciduous forests of birch and aspen trees |

4-7 |

| For stands with participation of Sivers apple trees |

2-3, 5 |

| Broad-leaved forest on rich soils |

3-5 |

5.3. Assessing the TCC of Katon-Karagay National Park

KKNP, with its sprawling landscapes and diverse ecosystems, is a focal point of ecological studies and tourism interest. Given the burgeoning global interest in ecotourism, understanding its sustainable load capacity is pivotal to balance conservation with recreation.

Within the vast expanse of the park, 851.68 hectares have been delineated as directly susceptible to anthropogenic pressures. This area encapsulates popular tourist routes, infrastructural developments, and human activity hubs, serving as a base point for our carrying capacity assessment. A year-long observation of the park recorded seasonal variations in tourist influx. While the warmer months recorded a higher density of visitors, owing to its more hospitable weather and blooming biodiversity, the colder months saw a marked reduction. Quantitatively, during the peak seasons, there was a surge, amounting to 150,131 people, whereas the off-peak seasons witnessed a reduced figure of 121,381 visitors.

To better ascertain the park's carrying capacity, a multi-variable approach was adopted. Among the primary considerations were the park's intrinsic environmental dynamics, such as topography, vegetation type, and susceptibility to risks like forest fires. Additionally, human-made systems like sewerage networks, waste disposal methods, and the quality and extent of the recreational infrastructure were also factored into the analysis.

A series of correction factors further fine-tuned these calculations:

Coverage of Sewerage Networks. Regions with an extensive sewerage system exhibited a higher resilience to increased tourist loads. These zones could effectively prevent contamination of natural resources. For ex-ample, areas with 90% coverage could accommodate an additional 5% of tourists compared to those with lesser coverage;

Waste Disposal Systems. Efficient waste disposal directly influenced an area's carrying capacity. Regions equipped with advanced waste management could handle 10% more visitors without any significant ad-verse environmental impact;

Environmental Self-healing. Some zones within the park showed a faster rate of environmental recovery post human interaction. These zones, due to their inherent resilience, could handle an increased load of approximately 7% more than their counterparts;

Recreational Infrastructure. Areas with well-developed recreational facilities, like resting points, tracks, and signages, demonstrated a 12% higher load capacity, ensuring visitors had minimal off-track excursions, thus reducing inadvertent damage.

Taking all these factors into account, the calculated TCC for KKNP was derived. The maximum actual natural tourism capacity was found to be 1.3 people/ha. In contrast, the minimum stood at 34.5 people/ha. When averaged out, the optimum number was around 26.5 people/ha, offering a blend of conservation and recreation.

A standout finding from the assessment was the data related to specific tourist routes. For example, the popular climbing route leading to Mount Belukha, given its rugged terrain and unique microecosystem, was designated with a permissible recreational load of 21.90 people/ha per season. Such specific calculations ensure that every pocket of the park receives its bespoke management strategy.

Furthermore, ensuring visitor comfort was a cornerstone of this assessment. Recognizing that the experience of tourists is directly proportional to the density of visitors in a specific area, it was advised that dense forest regions maintain a limit of 2 people per hectare. This recommendation aims to preserve the sense of wilderness and tranquility that tourists seek in such pristine environments (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Permissible recreational load of tourist routes of Katon-Karagay National Park.

Table 6.

Permissible recreational load of tourist routes of Katon-Karagay National Park.

|

Name of the route

|

Linear area, ha

|

Number of tourists, 2017

|

g, vulnerability and protected area status

|

Type of visit coefficient (organized / mass tourism)

|

f, soil cover factor

|

q, recreational development coefficient of the territory

|

Psychocomfort factor

|

Load rate for forest landscapes, people/ha per hour

|

Season duration, hour

|

Recreational load according to the passport, people/ha

|

Actual recreational load, people /ha season

|

TCC of the route, people/ha

|

Permissible recreational load,

people/ha/hour

|

Permissible recreational load, people /ha (per season)

|

|

Climbing Mount Belukha

|

3 |

73 |

12.5 |

0.2 |

0.01 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

6 |

1460 |

20 |

24.33 |

5,256 |

0.05 |

21.90 |

|

Forest Roads

|

7.5 |

17 |

37.5 |

0.2 |

0.02 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

8 |

2920 |

100 |

2.27 |

28,032 |

0.36 |

140.16 |

|

Berkutaul

|

10 |

113 |

50 |

0.2 |

0.02 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

6 |

2920 |

20 |

11.30 |

7,008 |

0.12 |

35.04 |

|

Sarymsakty

|

5.5 |

757 |

25 |

0.2 |

0.01 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

10 |

2920 |

100 |

137.64 |

29,2 |

0.25 |

132.73 |

|

Irek

|

10 |

20 |

37.5 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

8 |

2920 |

100 |

2.00 |

70,08 |

0.90 |

262.80 |

|

Tasshoky

|

6 |

20 |

37.5 |

0.15 |

0.04 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

8 |

2920 |

100 |

3.33 |

25,2288 |

0.32 |

157.68 |

|

Ozerniy

|

20 |

11 |

12.5 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

10 |

2190 |

100 |

0.55 |

197,1 |

1.13 |

123.19 |

|

To Tikhiy Lake

|

3.75 |

11 |

12.5 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

6 |

2920 |

100 |

2.93 |

35,04 |

0.15 |

116.80 |

|

Belaya Berel

|

37.5 |

483 |

12.5 |

0.2 |

0.04 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

8 |

2920 |

5 |

12.88 |

18,688 |

0.08 |

6.23 |

|

To Bulandykol Lake

|

5 |

5 |

12.5 |

0.15 |

0.01 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

8 |

2920 |

5 |

1.00 |

3,504 |

0.02 |

8.76 |

|

Maral Trails

|

6 |

5 |

12.5 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

10 |

2920 |

100 |

0.83 |

58,4 |

0.25 |

121.67 |

|

Altai Trails

|

25 |

706 |

37.5 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

10 |

2920 |

|

28.24 |

87,6 |

1.13 |

131.40 |

|

Rakhmanov Springs

|

1.75 |

1279 |

12.5 |

0.3 |

0.04 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

10 |

2920 |

|

730.86 |

157,68 |

0.68 |

1126.29 |

|

Along The Native Land

|

0.75 |

15 |

12.5 |

0.3 |

0.01 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

10 |

2920 |

3 |

20.00 |

8,76 |

0.04 |

146.00 |

6. Discussion

The TCC assessment in a sustainable context, especially for protected areas like KKNP, holds paramount importance for ensuring the preservation of natural habitats while still promoting tourism, an economic boon for many regions. This research utilized SWOT analysis (see Table 7), shedding light on the park's strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, to provide a holistic perspective on its current status and potential trajectory. This in-depth analysis not only reveals a mosaic of factors that contribute to the park's potential as a tourist destination but also offers insights into how these elements interplay in a real-world setting.

Given the weakness pinpointed in the SWOT analysis, like the lack of a strategic plan for development and absence of adequate infrastructural equipment, it's evident that while the park boasts an impressive natural potential, its management systems might not be fully optimized to handle increased tourism influx [

3]. It underscores the need for continuous monitoring of both norms and perceptions of overcrowding, particularly in the light of changing visitor dynamics, as previously explored. This weakness could be addressed by implementing some of the recommendations offered, such as infrastructural improvements and more detailed cartographic material.

The identified threats, including increased tourist flow on popular routes and a potential decline in service quality due to a growing number of visitors, further reiterate the importance of continuous assessment and recalibration. Such threats, if not mitigated, can challenge the core strength of the park, which is its rich natural potential. One of the discussed methods to address these threats lies in the optimization of existing routes, ensuring that areas experiencing higher anthropogenic impact are given the necessary attention and resources [

44].

Additionally, opportunities, like the formation of a modern regulatory framework and the growth of interest in domestic tourism, provide a glimmer of optimism. Harnessing these opportunities can aid in turning some of the weaknesses and threats into strengths. Particularly, strengthening human resource potential through partnerships with universities can mitigate the identified weakness of lack of knowledge and experience among inspectors[

34]. This ties in with the recurrent theme from our literature review that the interplay of environmental conservation and tourism promotion requires multifaceted strategies that are continuously updated to current dynamics.

Recreational monitoring, as elucidated, stands out as a pivotal methodological approach to understand and manage the intricate balance between tourism and ecological preservation. The detailed recommendations, ranging from basic infrastructural improvements to intricate, data-driven analysis like hydrochemical works, display a comprehensive strategy to elevate the tourism experience while ensuring minimal ecological impact. Such methods, when seen in the light of previous studies, reiterate the need for protected areas to employ data-driven, holistic approaches that consider both anthropogenic and natural factors in decision-making processes.

Table 7.

SWOT-analysis of Katon-Karagay National Park.

Table 7.

SWOT-analysis of Katon-Karagay National Park.

| Weaknesses |

Threats |

lack of a strategic plan for improvement and development of new routes; lack of cartographic material (maps, map charts); lack of sufficient knowledge and experience of accompanying inspectors in working with commercial groups; absence or unsatisfactory condition of route marking; insufficient infrastructural equipment; limited staff of specialists in the departments of environmental education and tourism and insufficient technical support (including special transportation, operational communication, special equipment and tools, etc.); inaccessibility of a significant part of tourist routes; poor contact with local communities and tourism companies |

increase of tourist flow on popular routes due to improved access roads; non-compliance of the quality of services with safety requirements, provoked by the growing number of visitors; lack of a system for regulating and redirecting the flow of tourists and excursionists |

| Strengths |

Opportunities |

availability of local specialists who understand the situation and are ready to work on its improvement; rich natural potential as a basis for ecological tourism; formation of a modern regulatory framework (inclusion of tourism in the list of priority areas of economic development of Kazakhstan, adoption of the state program of tourism development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2019-2025, supported by funding); growth of interest and number of consumers of services in the domestic tourism market; - availability of incentives for long-term investments in the tourism and hospitality sector, including on the basis of PPPs |

strengthening and development of human resources potential (including through partnership with universities and other institutions that train personnel for tourism and hospitality); improvement of the quality of services through the updating of mat-base, training and retraining of personnel; identification and development of demonstration ("reference") trails and routes for demonstration purposes and for testing modern service technologies; expansion of the route network, optimization of existing routes and trails; expansion of the list and scope of services provided; updating websites, intensifying promotion of park services using mass media, social networks, face-to-face contacts; establishment of long-term cooperation with local communities and travel agencies |

Furthermore, the emphasis on engaging tourists through surveys before and after visiting the park offers a novel approach to understanding the transformative nature of such experiences. This could be an invaluable tool, not just for feedback but for gauging the potential cognitive shifts in tourists, thus aligning with the previously discussed notion of changing visitor perceptions.

In the broader context, the insights from this study offer a microcosm view of the challenges and opportunities faced by protected areas globally. The intricate dance between preservation and promotion requires a nimble approach, regularly updated with empirical data and nuanced to cater to the specific needs of each region. While the results from this study are deeply rooted in the context of KKNP, the overarching themes, methodologies, and challenges resonate with global paradigms of sustainable tourism in protected areas.

While this study offers a granular view into the TCC of KKNP, it also, inadvertently, becomes a testament to the universal challenges and opportunities faced by protected areas globally. The need for a balanced, data-driven, and adaptive approach remains paramount, echoing the sentiments of various scholars in the field. Future studies could delve deeper into understanding the socio-economic implications of such methodologies and their broader applicability in diverse settings, while encapsulating the very essence of sustainability and tourism interdependence.

The recommendations postulated in this study, such as the improvement of infrastructural elements, the optimization of routes, and the creation of thematic maps, emphasize the synthesis of ecological preservation and enhanced visitor experience. This dual approach ensures that while the park’s natural integrity is maintained, it also evolves to cater to the diverse needs and expectations of the tourists. The relevance of this equilibrium is reflected in various studies that underline the symbiotic relationship between sustainable tourism and ecological conservation.

Furthermore, the potential expansion of the park’s route network underscores another significant discourse: the role of visitor dispersal in mitigating environmental impact. By directing visitors across a broader area rather than concentrated zones, it’s conceivable to alleviate pressure on specific regions of the park. Such spatial management strategies have been identified in past research as effective tools in maintaining ecological balance[

46].

The emphasis on engaging with local communities and travel agencies, as pointed out in the opportunities, also adds another dimension to the discussion. It's well established that local communities play a pivotal role in the sustainable management of tourist destinations[

47]. Their involvement not only ensures that tourism strategies are more grounded and realistic but also ensures that the socio-economic benefits of tourism trickle down to the grassroots level. This local-centric approach, coupled with the park's natural allure, could potentially foster a community-driven model of tourism, where both preservation and promotion are intertwined in communal ethos.

The inclusion of advanced technological solutions, such as 3D-tour routes and electronic registration of visitors, suggests a progressive outlook towards modernizing the visitor experience. However, it’s essential to ensure that the adoption of such technologies does not overshadow the park’s primary appeal: its natural and untamed beauty. The challenge lies in seamlessly integrating these technological facets in a manner that augments, rather than detracts from, the raw and immersive experience that national parks like Katon-Karagay offer.

In juxtaposing the SWOT analysis with the recommendations provided, a pattern emerges highlighting the need for an adaptive management strategy. This entails a system where feedback, obtained through continuous monitoring and tourist surveys, informs the iterative refinement of management practices. Such a feedback-driven approach has been championed in sustainable tourism discourses, advocating for a dynamic model that evolves in response to changing environmental conditions and visitor dynamics [

48].

Lastly, the emphasis on recreational monitoring, with its detailed and multifaceted approach, underscores a significant point: the essence of sustainability in tourism is not static but is a dynamic equilibrium. It demands continuous attention, periodic adjustments, and most importantly, a commitment to harmonizing human desires with nature's imperatives. This sentiment, rooted in the confluence of anthropogenic activities and ecological preservation, encapsulates the broader narrative of sustainable tourism – a journey, not a destination.

In the vast tapestry of sustainable tourism literature, this study adds a valuable thread, weaving together empirical insights with theoretical discourses, highlighting both the challenges and the potential pathways to harmonize human aspirations with the rhythms of nature. Future research could expand upon this foundation by exploring the socio-cultural implications of these strategies and assessing their long-term impact on both the environment and the visitor experience.

The nexus between the recommendations offered and the SWOT analysis implies a recognition of the inherent challenges the park faces. For instance, the weakness pointing to the lack of strategic planning for the development of new routes is offset by the opportunity to leverage the increasing interest in domestic tourism. By addressing this, not only can the park alleviate pressures on over-utilized routes, but also capitalize on unexplored natural vistas, further enhancing the park’s appeal.

Furthermore, the threats identified, such as the potential increase in tourist flow on popular routes due to improved access, emphasize the urgency of implementing effective monitoring strategies. Without timely interventions and adaptive management, the risk of ecological degradation becomes palpable. The recommended focus on monitoring specific components of the natural environment - from soil erosion to impacts on fauna – suggests a multi-faceted approach to ensure comprehensive assessment and timely intervention.

The introduction of technological tools, like electronic visitor registration, is indicative of the necessity to amalgamate traditional conservation practices with modern advancements. While the allure of the park is its pristine natural environment, embracing technological tools can enhance management efficiency and offer insights that might otherwise be overlooked.

Moreover, the engagement with local communities isn't just a strategic decision but also an ethical one. Past studies have iterated the invaluable contributions local communities make to sustainable tourism, often acting as custodians of the natural environment and cultural heritage. Their active involvement ensures that tourism developments align with their socio-cultural values, fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility, which is paramount for the long-term success of any sustainable tourism initiative.

On the topic of ecotourism, a sector that the park prominently operates within, the discussions around the ecotrail, “Sarymsakty”, and the suggestions for its improvement provide a microcosm of the broader challenges and opportunities in managing protected areas. The need for an eco-trail concept, comprehensive design, and infrastructure is symbolic of the broader ethos of sustainable tourism: offering enriching experiences while ensuring ecological harmony. The emphasis on recreational monitoring, though crucial, brings forth a perennial challenge: the interpretation of the data. While the collection of data might be systematic, deriving actionable insights demands a nuanced understanding of the interplay between various ecological factors. This calls for collaboration with multidisciplinary teams, drawing expertise from ecologists, sociologists, and tourism scholars to holistically comprehend the ramifications of the findings.

Conclusively, this discussion underscores the intricate dynamics of sustainable tourism within KKNP. The interwoven challenges and opportunities present a complex, yet rewarding puzzle. Addressing it necessitates a cohesive strategy, grounded in empirical evidence, ecological sensitivity, and stakeholder engagement. As the global discourse on sustainable tourism evolves, this study stands as a testament to the intricate balance required to ensure both conservation and recreation in the world's most precious natural arenas. Future explorations could delve deeper into understanding the behavioral aspects of tourists, refining strategies to ensure alignment with sustainable tourism's overarching goals.

7. Conclusions

TCC is a critical component in the pursuit of sustainable development, especially in protected environments like KKNP. This study delved deep into the intricacies of this topic, merging a rich blend of empirical data, calculative methods, and scholarly literature, thereby casting a discerning light on the confluence of ecological conservation, socio-economic facets, and sustainable tourism management.

The foundation of this exploration was rooted in primary data garnered from KKNP, which illuminated the nuances of recreational loads on its various routes and ecotrails. This empirical material was instrumental in quantifying the direct impacts of tourism on the park's ecosystems.

Through the lens of the carrying capacity framework, especially focusing on ecological and tourist social capacities, a systematic methodology was crafted. This included calculated approaches integrating multiple variables, the psychocomfort approach emphasizing human experiences, and a vigilant monitoring approach addressing ecosystem sustainability.

Employing formulas and established methodologies revealed insights into permissible recreational loads for various zones within the park. Such mathematical rigor offered tangible metrics, ensuring that tourism management aligns harmoniously with the park's ecological sensitivities.

The psychocomfort approach further underscored the anthropocentric dimension of this study, emphasizing the essential balance between the preservation of nature and the quality of the tourist experience.

Continuous monitoring, as highlighted in the methodology, emerged as a cornerstone principle, underscoring the dynamic interplay between nature and tourism and the need for adaptive strategies to address evolving challenges.

Literature reviews and extensive comparative analyses further enriched the study, grounding empirical findings in academic discourse and broader practical applications.

The exclusive data from KKNP's administration added an invaluable layer to the study, ensuring its findings are rooted in real-world observations and aligned with the park's strategic goals.

In summation, this study unraveled the multifaceted realm of TCC in the context of sustainable development, with KKNP as its focal point. The insights gleaned underscore the imperative of maintaining an equilibrium between environmental conservation, socio-economic imperatives, and enriching tourist experiences. The rigorous methodologies employed and the findings derived pave the way for more informed decisions, fostering a future where tourism complements ecological resilience rather than compromising it. This research underscores the potential alignment of human activities with ecological preservation, emphasizing the need for meticulous planning, strategic foresight, and adherence to sustainable principles.

8. Patents

Certificates of entry of details into the state register of rights for objects protected by copyright (type of copyright: scientific work) titled:

“Ensuring Sustainable Development of Kazakhstan's National Parks through Territorial Organization of Ecotourism” / No. 30115 dated November 8, 2022.

“Systematic Analysis of Contemporary Research Globally and in CIS Countries on the Assessment of Tourism Carrying Capacity and Methods for Rational Use of Natural Touristic-Recreational Sites” / No. 20253 dated September 14, 2021.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva), and Y.N.; methodology, A.A. (Alexandr Artemyev), A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva) and Y.N.; software, Y.N.; validation, A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva), Z.A. and Y.N.; formal analysis, A.K. and A.S.; investigation, Y.N. and A.S.; resources, A.A. (Alexandr Artemyev), A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva), A.K. and A.S.; data curation, A.A. (Alexandr Artemyev) and A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva); writing—original draft preparation, Y.N. and A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva); writing—review and editing, A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva), Z.A. and Y.N.; visualization, Y.N.; supervision, A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva); project administration, Z.A. and A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva); funding acquisition, Z.A., A.A. (Aliya Aktymbayeva) and Y.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP09260144 “Rational use of natural tourist-recreational resources of the Republic of Kazakhstan based on recreational capacity assessment and anthropogenic impact minimization”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- X. Dong, S. Gao, A. Xu, Z. Luo, and B. Hu, “Research on Tourism Carrying Capacity and the Coupling Coordination Relationships between Its Influencing Factors: A Case Study of China,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 22, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Aktymbayeva, Z. Assipova, A. Moldagaliyeva, Y. Nuruly, and A. Koshim, “Impact of small and medium-sized tourism firms on employment in Kazakhstan,” Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 1238–1243, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. F. Kuentzel and T. A. Heberlein, “More visitors, less crowding: Change and stability of norms over time at the Apostle Islands,” J Leis Res, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 349–371, 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. Hoffmann, “Challenges and opportunities of area-based conservation in reaching biodiversity and sustainability goals,” Biodivers Conserv, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 325–352, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Aktymbayeva, Y. Nuruly, B. Aktymbayeva, and G. Aizholova, “Analysis of the development of modern agritourism types in West Kazakhstan oblast,” Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 902–910, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Koens, A. Postma, and B. Papp, “Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 12, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Stefanica, C. B. Sandu, G. I. Butnaru, and A.-P. Haller, “The nexus between tourism activities and environmental degradation: Romanian tourists’ opinions,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 16, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sapiyeva A.Z., Nuruly Y., and Assipova Z.M., “Evaluation of the multiplicative effect of ecotourism development in Kazakhstan (on the example of the «Buyratau» National Park),” 2020. Accessed: Sep. 26, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://caer.narxoz.kz/jour/article/view/282/284.

- A. Koshim, A. Sergeyeva, Y. Kakimzhanov, A. Aktymbayeva, M. Sakypbek, and A. Sapiyeva, “Sustainable Development of Ecotourism in ‘Altynemel’ National Park, Kazakhstan: Assessment through the Perception of Residents,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Cimnaghi and P. Rosasco, “Tourism carrying capacity for the analysis and the management of tourism: The case study of the Vesuvius National Park | La Capacità di Carico Turistica come strumento di analisi e gestione del fenomeno turistico: Il caso studio del Parco Nazionale del Ve,” Geoingegneria Ambientale e Mineraria, vol. 142, no. 2, pp. 33–42, 2014.

- M. D. D. P. Quintal and R. G. S. Pavón, “Tourism carrying capacity for beaches in tulum national park, Mexico,” WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, vol. 248, pp. 191–201, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, E. Wang, and Y. Yu, “Assessing tourism carrying capacity in the national forest park based on visitor’s willingness to pay for the environmental,” Xitong Gongcheng Lilun yu Shijian/System Engineering Theory and Practice, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 1153–1163, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Li and L. Rong, “Ecotourism carrying capacity in Hangzhou Xixi National Wetland Park in China,” Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, vol. 18, no. 10, pp. 2301–2307, 2007.

- E. Maldonado and F. Montagnini, “Carrying capacity of La Tigra National Park, Honduras: Can the park be self-sustainable?,” Journal of Sustainable Forestry, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 29–48, 2004. [CrossRef]

- A. Israngkura, “Marine resource recovery in Southern Thailand during COVID-19 and policy recommendations,” Mar Policy, vol. 137, 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. A. S. L. P. Putri and F. Ansari, “Managing nature-based tourism in protected karst area based on tourism carrying capacity analysis,” Journal of Landscape Ecology(Czech Republic), vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 46–64, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Joglekar, S. D. Manjare, V. Sathyaseelan, S. Dongre, and M. Girap, “Tourism development model ecosystem settings based on support system for Dudhsagar waterfall, Goa, India,” Environmental Quality Management, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. G. S. Pavón and I. I. C. Piña, “Sustainable tourism development in parque nacional lagunas de Montebello, Mexico,” WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, vol. 227, pp. 83–93, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Rogowski, “Monitoring System of tourist traffic (MSTT) for tourists monitoring in mid-mountain national park, SW Poland,” J Mt Sci, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 2035–2047, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Kostopoulou and I. Kyritsis, “A tourism carrying capacity indicator for protected areas,” Anatolia, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 5–24, 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Fatina, T. E. B. Soesilo, and R. P. Tambunan, “Collaborative Integrated Sustainable Tourism Management Model Using System Dynamics: A Case of Labuan Bajo, Indonesia,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 15, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Dani, E. Widyaningsih, and A. Febriansyah, “Applying the architectural design concept for Rawa Kalibayem development based on the carrying capacity study,” PROCEEDING OF THE 7TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH (IC-STAR 2021), vol. 2601, p. 020002, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Leka, A. Lagarias, M. Panagiotopoulou, and A. Stratigea, “Development of a Tourism Carrying Capacity Index (TCCI) for sustainable management of coastal areas in Mediterranean islands – Case study Naxos, Greece,” Ocean Coast Manag, vol. 216, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Vagiona and A. Palloglou, “An indicator-based system to assess tourism carrying capacity in a Greek island,” International Journal of Tourism Policy, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 265–288, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. P. Sati, “Tourism carrying capacity and destination development,” Environmental Science and Engineering, pp. 123–131, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Long, S. Lu, J. Chang, J. Zhu, and L. Chen, “Tourism Environmental Carrying Capacity Review, Hotspot, Issue, and Prospect,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 24, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Garau, D. Carboni, and A. Karim El Meligi, “Economic And Environmental Impact Of The Tourism Carrying Capacity: A Local-Based Approach,” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, vol. 46, no. 7, pp. 1257–1273, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Ye, J. Park, F. Wang, and X. Hu, “Analysis of early warning spatial and temporal differences of tourism carrying capacity in China’s Island cities,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 4, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Cheng, J. Cheng, Z. Zhu, and Z. Wang, “Tourism carrying capacity of forest vegetation in Wutai Mountain scenic area based on community perspective,” Shengtai Xuebao, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 3144–3154, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Khaledi Koure, M. Hajjarian, O. Hossein Zadeh, A. Alijanpour, and R. Mosadeghi, “Ecotourism development strategies and the importance of local community engagement,” Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 6849–6877, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Nasha and Z. Xilai, “Conceptual Framework of Tourism Carrying Capacity for a Tourism City: Experiences from National Parks in the United States,” Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 88–92, 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. Sinlapasate, W. Buathong, T. Prayongrat, N. Sangkhanan, K. Chutchakul, and C. Soonsawad, “Tourism carrying capacity toward sustainable tourism development: A case study of phuket world class destination,” ABAC Journal, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 140–159, 2020.

- J. Obua and D. M. Harding, “Environmental impact of ecotourism in kibale national park, uganda,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 213–223, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Z. Aliyeva, M. Sakypbek, A. Aktymbayeva, Z. Assipova, and S. Saidullayev, “Assessment of recreation carrying capacity of Ile-Alatau National park in Kazakhstan,” Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 460–471, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Sharma, “A framework for tourism carrying capacity analysis,” ICIMOD Discussion Paper, MEI Series, vol. 95, no. 1, 1995.

- X. P. Yang, “Analysis of dynamic improving hierarchical process (DIAHP) - Based analysis of tourism environment carrying capacity and related countermeasure,” Journal of Ecology and Rural Environment, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. 2008.

- Y. Wang, J. Zhang, C. Wang, Y. Yu, Q. Hu, and X. Duan, “Assessing tourism environmental psychological carrying capacity under different environmental situations,” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 132–146, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Guo and S. Chung, “Using Tourism Carrying Capacity to Strengthen UNESCO Global Geopark Management in Hong Kong,” Geoheritage, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 193–205, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, X. M. Liu, K. K. An, and J. J. Hou, “Research on Spatio-temporal Differentiation and Spatial Effect of Tourism Environmental Carrying Capacity of Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomerations,” Resources and Environment in the Yangtze Basin, vol. 31, no. 7, pp. 1441–1454, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Candia, F. Pirlone, and I. Spadaro, “Integrating the carrying capacity methodology into tourism strategic plans: A sustainable approach to tourism,” International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 393–401, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Chen, “Resource development and tourism environment carrying capacity of wetland park ecotourism industry,” J Biotech Res, vol. 12, pp. 199–205, 2021.

- L. Xiao, D. Zhu, and H. Yu, “Simulation on recreation carrying capacity of Sanjiangyuan National Park | 三江源国家公园游憩承载力模拟仿真研究,” Shengtai Xuebao, vol. 42, no. 14, pp. 5642–5652, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Y. Ahn, B. K. Lee, and C. S. Shafer, “Operationalizing sustainability in regional tourism planning: An application of the limits of acceptable change framework,” Tour Manag, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2002. [CrossRef]

- K. Iskakova, S. Bayandinova, Z. Aliyeva, A. Aktymbayeva, and R. Baiburiyev, Ecological tourism in the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- USSR State Committee for Forestry, Provisional Methodology for Determining Recreational Loads on Natural Complexes in the Organization of Tourism, Excursions, Mass Daily Recreation, and Temporary Standards for These Loads. 1987.

- S. A. Moore and K. Rodger, “Wildlife tourism as a common pool resource issue: Enabling conditions for sustainability governance,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 831–844, 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. Tosun, “Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries,” Tour Manag, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 613–633, 2000. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Pomeroy, J. E. Parks, and L. M. Watson, “How is your MPA doing? A Guidebook of Natural and Social Indicators for Evaluating Marine Protected Area Management Effectiveness IUCN Programme on Protected Areas,” 2004. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |