1. Introduction

Panfacial fractures are traditionally defined as those involving all three regions of the face; frontal, midface, and mandible, however the term is commonly used for any facial fracture involving two of these areas. They are most often the result of high-energy trauma, and as a result, most patients will have concomitant injuries, most importantly intra-cranial and spinal injuries but also limb, thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic injuries. (1,2)

The initial management of patients presenting with trauma follows the well-established Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocols, starting with assessment and management of the Airway and Catastrophic Haemorrhage with establishment of a definitive airway where appropriate. (3)

In an emergency setting, this is normally achieved via orotracheal intubation with cervical spine immobilization with a high success rate when performed by trained rescue teams/anaesthesiologists (4). When this is deemed not feasible due to the severity of the facial/oral injury, distortion of the anatomy or severe haemorrhage, a front of neck access (FONA) to the trachea is the technique of choice. In these situations, cricothyroidotomy has been shown to be faster and have lower morbidity and mortality rates than tracheostomy. FONA is also the final step for “can’t intubate, can’t oxygenate” (CICO) emergencies as stated in the Difficult Airway Society guidelines. (5)

Orotracheal intubation is ideal for the acute management of the airway and the intra-operative care of non-facial injuries. However, in the dentate patient it does not permit establishment of the occlusion, one of the key outcomes sought in facial fracture treatment. This necessitates alternative options for definitive surgery of panfacial fractures. Whether the patient is already intubated due to their injuries or not, the options for managing the airway intra-operatively include oral/nasal endotracheal intubation, submental intubation, or surgical Front of Neck Accesses. The decision is based upon the patient’s fracture complexity and location, the type of surgery to be performed, including the need for maxillomandibular fixation, and involvement of the central nasal complex and skull base, but also the general status of the patient and the need for prolonged ventilation or planned phased surgeries (6).

In a survey conducted among surgeons and anaesthesiologists, on maxillofacial trauma airway management the tracheostomy was the first choice for patients with panfacial fractures or those with loss of consciousness and midface fractures (7). Trends have substantially changed since then, with the advent of new methods of intubation (8), in particular the submental intubation (9). In a retrospective study, Daniels et al. (10) reported 86.1% of a cohort of 43 panfacial fractures had submental intubation

Current debates regarding the optimal technique of airway management in panfacial fractures include the usefulness of retromolar intubation(11); the safety of nasotracheal intubation in the context of cranial base fracture(12); the feasibility of the intraoperative nasotracheal switch to orotracheal intubation in the context of a panfacial fracture(13); the convenience of performing a submental intubation in a comminuted anterior mandibular fracture(14); the need for a tracheostomy if a patient won’t need a prolonged intubation but also its reported intraoperative and postoperative complications(15); the role of the cricothyroidotomy in elective management of panfacial fractures (16) and lastly the staged surgical management of panfacial fractures that may avoid the mentioned pitfalls in airway management.

The objective of this literature review on the management of the airway in panfacial fractures is to assess the different methods of airway management proposed focusing on areas of contention and debate and subsequently to offer a potential algorithm for airway management in such cases.

3. Results

When a patient with a panfacial fracture arrives to the operating room breathing spontaneously multiple options, exist for securing a definitive airway. These include oral endotracheal intubation, nasal endotracheal intubation, nasal intubation followed by oral intubation, oral intubation followed by retromolar intubation, oral intubation followed by submental intubation, and surgical Front of Neck Accesses such as surgical or percutaneous tracheostomy and cricothyrotomy.

It is not uncommon for patients to be brought to the operating theatre with an orotracheal tube already in place from their initial trauma management and a decision then still needs to be made on how to proceed

3.1. Retromolar intubation.

When orotracheal intubation (OTI) is already established, but interferes with reduction of the maxillomandibular fractures and precludes intermaxillary fixation (IMF) it can be repositioned to a retromolar intubation. This is a useful alternative avoiding the need to remove the existing airway, particularly when re-intubation may be difficult (17). This method has its own drawbacks such as lack of space in the retromolar area, and interference with the reduction.

Retromolar intubation was first described by Bonfils in 1983 (18) as a new method for difficult intubation in a Pierre-Robin case but popularized by Martinez-Lage in 1998 (19), primarily for orthognathic surgery and craniofacial surgeries. His technique implied the creation of room at the retromolar area with either removal of third molars when present and / or a semilunar osteotomy large enough for the tube to lie below the occlusal plane.

The ideal situation would be when it can be performed without the need of an osteotomy, because performing an osteotomy in the context of a facial fracture is debatable. Different attempts have been made to measure the available space in this area. Sittitavornwong et al. (11) by retrospectively reviewing the CT scan of maxillofacial trauma patients to assess this area and then compared to the area of different reinforced endotracheal tubes and concluded that the retromolar space area was statistically significantly larger than the reinforced oral endotracheal tube area for sizes 6.0, 6.5, and 7.0. A limitation to this study was that it included only patients who were missing third molars or had their third molars impacted which would not affect the available retromolar space but also the soft tissue in the retromolar area, particularly along the ascending ramus and tuberosity area, was not considered.

Its main advantage is that is an easy technique to perform and its speediness in terms of time taken for intubation (17). Retromolar fibreoptic orotracheal intubation for cases of severe trismus has also been described. (20,21)

Retromolar intubation has disadvantages like tube interference within the surgical field and is not feasible in cases of limited bony retromolar space or if there is an excess of soft tissue in the retromolar trigone. In addition, it may not be suitable when mandibular angle fractures are present as it may interfere with the surgical approach, reduction and/or osteosynthesis. Finally, a suitably flexible orotracheal tube must be used which can bent without kinking.

Complications reported of the retromolar intubation are displacement of the tube and interference in the surgical field (17).

3.2. Is nasotracheal intubation contraindicated in the presence of skull base fracture?

The most common technique for airway management in facial fractures where there is a need to assess and fix the occlusion is Nasotracheal intubation (NTI) (22,23).

Smoot et al. (7) reported in a survey, that this was the method of preference expressed by surgeons and anaesthesiologists with more than 50% choosing some form of nasotracheal intubation for fracture patterns involving the midface. Most of the concern expressed by anaesthesiologists for nasotracheal intubation occurred in fracture patterns in which the cribriform plate status was unknown. Additionally, there was concern in those fracture patterns that involved the ethmoid, basilar skull, and fractures designated Le Fort type II or III.

These concerns are based on anecdotal reports of intra-cranial intubation (12). The most feared complication of NTI includes cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak and inadvertent placement of the endotracheal tube through the skull base in the presence of nasoethmoid or anterior cranial fossa fractures. (12). Large retrospective case series have demonstrated its safety in the presence of a skull base fracture (SB) (24,25) in both the acute setting and elective management. Rhee et al. (26) in (a study of 86 patients with SBF found no differences comparing blind NTI to OT intubation in terms of CSF leakage, meningitis, cranial nerve injury, intracranial placement when this intubation was performed in the field. Jazayeri-Moghaddas et al. (27) analysed three groups of patients depending on the method of intubation (nasotracheal intubations only, orotracheal intubations only and patients who were initially nasally intubated and changed to an oral tube after admission) and found no differences in mortality for the three groups. Both the nasal group and the oral group had fewer cases of sinusitis and pneumonia than the combination group and no patient had sinus or cribriform plate penetration regardless of intubation method. In a study of 160 patients with SBF and CSF fistula, Bahr and Stoll (24) reported that the route of tracheal intubation had no influence on the postoperative complication rate. There was no case of direct cerebral injury associated with nasotracheal intubation and the incidence of meningitis was the same, 2.5%, after oral and nasal intubation. The authors concluded that nasal intubation was not contraindicated in the presence of frontobasal fractures. Despite this, concerns about NTI in the presence of ACF fractures remains widespread.

Fractures involving the central midface will distort the normal anatomy and therefore although, blind nasal intubation can be safe for patients with facial trauma as stated by Rosen et al. (28), in a controlled environment such as the operating room NTI should be performed under direct vision with fibreoptic guidance (17)

NTI can however also cause problems in the management of the facial fractures involving the nasoethmoid complex beyond the additional difficulty for the insertion of a Nasotracheal tube.

Where the nasoethmoid complex needs to be repaired, this nasotracheal tube can jeopardize the correct reduction of the fractures and in these scenarios, the intraoperative change of the NT passage to an OT has been advocated (13).

NTI usually involves passing the tube and securing it over the top of the patient’s head, however if a coronal flap is indicated for access to the midface or frontal regions, this will then not be possible. Although the tube can be placed across the midface, this still has the potential to interfere with the surgical procedure.

In summary, nasotracheal intubation is not contraindicated in the presence of skull base fracture, even in the acute management. To avoid the rare but devastating consequences of intracranial intubation, fibreoptic intubation is recommended.

3.3. Nasotracheal to Orotracheal

To overcome the situation of a patient with a panfacial trauma that needs to have the central nasal complex repaired and has been nasally intubated, the conversion of the nasotracheal intubation to orotracheal without extubating has been proposed to avoid the risks associated with removing a secure airway intra-operatively.(13)

In short, standard nasal intubation is performed and the intraoral procedure is completed. The nasal tube is then cut external to the nares and distal to the pilot tube and delivered orally. Mittal et al. (23) performed the nasal to oral switch in 161 patients for the purpose of nasal bone reduction after the fixation of maxilla and mandible. Fibreoptic guidance for nasal intubation was required in 52 patients either because of cervical spine injury or because of difficult airway. Nasal bleed was the most common complication reported in 20 cases. No cases of meningitis or intracranial passage of the tube were reported.

There are several advantages of this technique over current options. In the patient who does not otherwise require tracheostomy, both a reintubation and a delayed procedure with a second general anaesthetic may be avoided. Nasal fractures can also then be treated in the same surgical procedure without a nasal tube in place.

The contraindications for this tube switch procedure may include severe frontobasal fractures, severe midface fractures, inability to achieve rigid fixation of jaw segments, and planned prolonged postoperative intubation. Gross distortion/wounds in the nasopharynx or oropharynx may preclude a safe switch.

3.4. Is submental intubation a first choice in panfacial fractures?

Submental intubation was first described by Hernández-Altemir in 1984 (29) and reported in the English literature in 1986 (30). After its development, it has been used as a first-choice technique for intra-operative airway management in complex maxillofacial injuries by some, with panfacial trauma being one of the most common indications for submental endotracheal intubation. (31-46)

Patients are initially orotracheally intubated, and then the tube is passed through the anterior floor of mouth and reconnected to the ventilator. This allows access to the whole of the face without interference.

In a systematic review performed by Goh et al. (47) including papers published between 1986 and 2018, which included 2229 patients, the indication for this technique was maxillofacial trauma in 81% of the cases. The mean intubation time was 10 minutes. The complication rate was 7%, with superficial skin infection the most reported complication.

Among complications reported, the most significant were accidental extubation (31) or accidental perforation of the pilot balloon in 4.35% of cases (42). Other complications included wound infections, between 2-3.5% (37,41); transient lingual and marginal nerve paraesthesia; bleeding and submental hypertrophic scar 1.45%-3.57% (32,35); orocutaneous fistula; traumatic injuries to the submandibular and sublingual glands or ducts (36) or mucocele formation.

Submental intubation appears to have lower morbidity and better outcomes when compared with tracheostomy. In a prospective randomized controlled trial by Emara et al. (9), of 32 patients with panfacial fractures randomly assigned to elective tracheostomy or submental intubation the average time required to perform a submental intubation was 8.35 min versus 30.75 min required to perform an elective surgical tracheostomy. No complications were reported with submental intubation whilst in the elective tracheostomy group, surgical emphysema was registered in two patients. The submental scar was acceptable in all patients while the tracheostomy scar needed scar revision in four cases.

Contraindications are the need for long-term ventilatory support and maintenance or those that require multiple maxillofacial surgical procedures. If mechanical ventilation or intubation is required postoperatively, the submental intubation could be switched over back to standard orotracheal intubation, but it has been maintained in the postoperative setting for up to 2 days with good tolerance (43)

Submental intubation in the presence a comminuted symphyseal or parasymphyseal fracture in which an external approach is needed should be avoided as the tube may interfere with the surgical approach or reduction. Gadre and Waknis (14) noted that in patients with comminuted fractures in the symphyseal and parasymphyseal regions, the conventional submental technique would necessitate stripping of lingual periosteum that would be detrimental to the blood supply of the smaller fragments and proposed using the area between the two mandibular molars on the contralateral side to the fracture (48)

The presence of cervical hematoma, infection or severe swelling in this area are relative contraindications.

In summary submental intubation is a minimally invasive procedure that was easier to perform and could be completed in 10 minutes with a success rate reported to be 100% and with a complication rate that ranges from 0 to 7% (47)

3.5. Is there still a role for tracheostomy for airway management in craniomaxillofacial trauma?

Tracheostomy is the definitive airway, and it does not interfere with surgical access to the face. It is a traditional approach to airway management in complex reconstructive procedures that is usually considered to be safe. (15) It was the first choice for patients with panfacial fractures or those with loss of consciousness and midface fractures in a survey of surgeons and anaesthesiologists (7)

Holmgren et al. (49) reported that 11.6% of all facial fracture patients received a tracheostomy during the same operative procedure. Those patients who had a tracheostomy performed had lower GCS and different fracture patters than those that had not had a tracheostomy, with a significantly higher incidence of mandible, multiple mandible, Le Fort III, and laryngeal fractures. There were no known cases of glottic or subglottic stenosis, severe bleeding requiring a return to the operating room, airway obstruction, or loss of secured airway in this series, although such complications are anecdotally reported.

Because of the improved airway management techniques, the use of rigid internal fixation that may obviate the need for IMF or at least reduce the period that is needed, many surgeons no longer advocate routine tracheostomy for patients with complex facial trauma (8,9,10,15,22,23).

It is indicated in cases with prolonged ventilation and where submental intubation, endotracheal and nasotracheal intubation is contraindicated or patients admitted with pre-existing cricothyroidotomy. Head and neck trauma is the most common injury requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation and in those patients, ventilator-associated pneumonia is reported as the major cause of death (50)

It is also indicated in polytrauma where a patient might require several operations over a relatively short period of time and obviates the need for repeated tracheal intubation.

Although tracheostomy is secure, it is associated with a significant number of intraoperative and postoperative complications (51). These complications can be grouped into intraoperative, early (<1wk), and late complications. Reported intraoperative complications are nerve injury, bleeding, and the development of subcutaneous emphysema or a pneumomediastinum, following passage of the tracheostomy tube into a false lumen. Tube blockage, respiratory infection, aspiration, or pneumonia are reported during the early postoperative period. As late complications, tracheal stenosis, tracheomalacia, tracheoesophageal fistula, voice changes, tracheal granulomas, or unfavourable scars are reported.

Intraoperative, early (<1 week), and late complication rates were reported to be 1.4%, 5.6%, and 7.1%, respectively. Postoperative bleeding was identified as the most common early complication (2.6%), whereas airway stenosis was the most common late complication (1.7%)

In a series of 1138 tracheostomies, Goldenberg et al., (52) reported 49 major complications (4.3%); 4 cases of accidental decannulation, 2 cases of trachea-innominate artery fistula with subsequent fatal haemorrhage, and 2 cases of postoperative tension pneumothorax with a mortality of 0.7% (8 patients) directly related to the tracheostomy.

An alternative that can be considered to open tracheostomy is percutaneous tracheostomy (53). This technique has gained widespread popularity, replacing the conventional surgical tracheostomy in the intensive care unit. In highly trained teams, it can be performed in 5 minutes, which compares favourably to open tracheostomy. Fibreoptic assistance is recommended.

Absolute contraindications to percutaneous tracheostomy include cervical instability, uncontrolled coagulopathy, and infection at the planned insertion site or tracheomalacia; Relative contraindications include difficult anatomy (short neck, overlying blood vessels, morbid obesity, minimal neck extension, or tracheal deviation)

Life-threatening complications, including major bleeding, or problems with the tracheostomy tube (54) may also arise with percutaneous tracheostomy, but it results in fewer wound infections and better aesthetic scar when compared to open tracheostomy (55).

It is possible to use for post-operative airway suctioning and may be used for extended intubation after elective head and neck surgery (56). There is only one report of its use in the postoperative setting of patients with panfacial trauma whose intermaxillary fixation was not to be removed (57).

3.6. What is the role of FONA with elective cricothyroidotomy?

Surgical cricothyroidotomy is a surgical airway technique in which an airway device is inserted into the trachea through an incision made at the cricothyroid membrane.

It is traditionally an emergency procedure and is recommended as the safest emergency surgical airway technique by Difficult Airway Society (4). Its role as an elective surgical airway in maxillofacial trauma is seldom reported (58). A cricothyroidotomy when present is normally converted to a tracheostomy.

One of the major complications attributed to this technique is subglottic stenosis. But Teo et al. (59) reported an incidence of 0.5% of subglottic stenosis, which compares favourably with the incidence of serious complications of tracheostomy.

Kuroiwa et al. (16) reported three cases of airway management with elective surgical cricothyroidotomy for anaesthetic management during surgical repair of maxillofacial injury involving basal skull fracture or nasal-bone fracture. No major complications, such as subglottic stenosis or voice change, occurred.

3.7. Staged treatment of panfacial fractures

Staging treatment in panfacial fractures is not necessarily an airway management technique; however, it can mitigate some challenges associated with managing the airway during these fractures. Typically, this approach involves addressing the lower third of the face during an initial operation, followed by the middle and upper thirds in a subsequent procedure. This approach benefits the patient through reduced time in the OR and allows the surgeon additional time for intricate midface reconstruction, facilitating virtual surgical planning and additive manufacturing. Moreover, a stable mandible makes the planning of the midface much easier. The first operation may be performed with standard nasal intubation which is removed at the end of the procedure, and an alternative such as oral intubation used during treatment of the upper and middle thirds. This however does not benefit when intermaxillary fixation is required during the second operation. In such cases, a submental intubation could be the alternative.

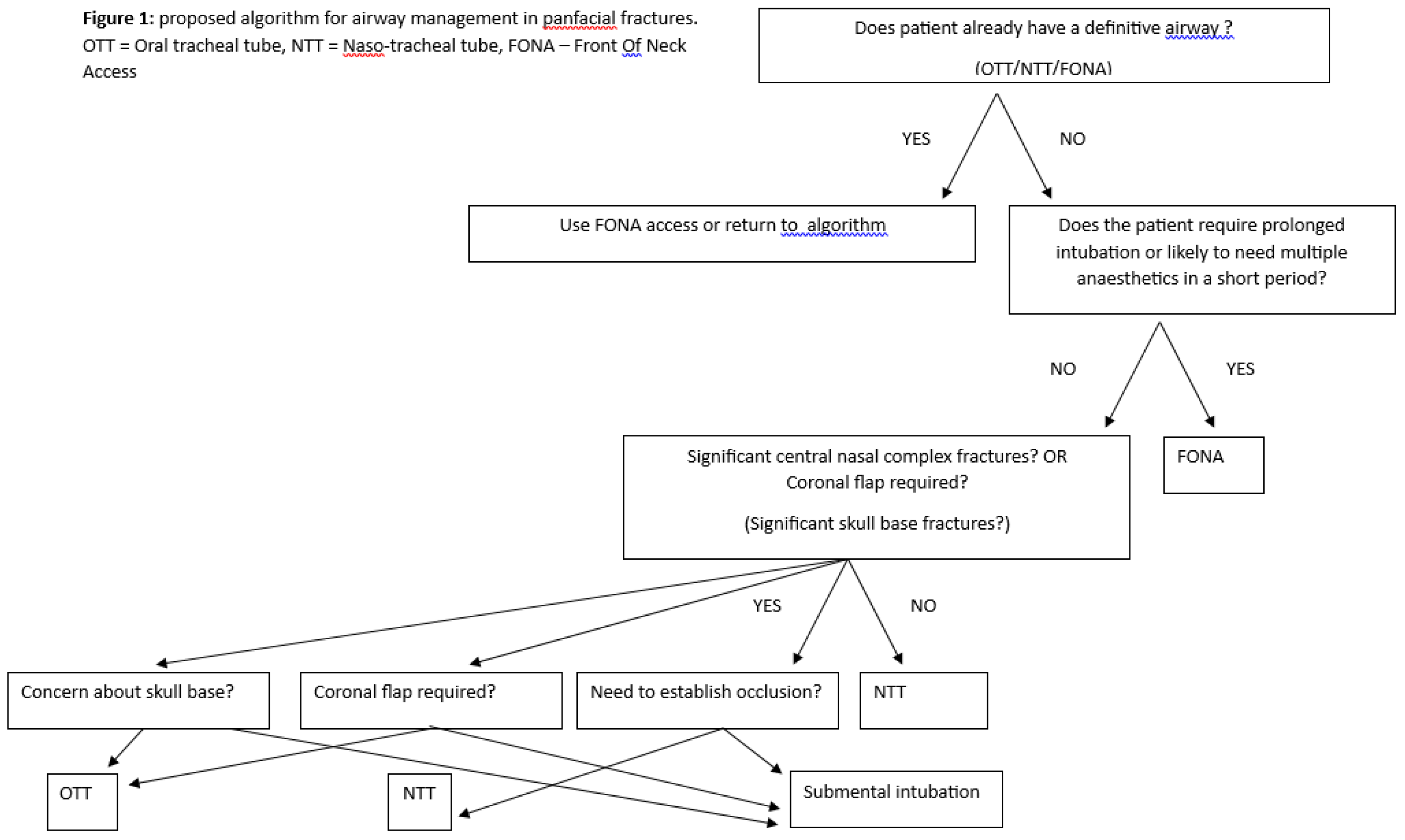

3.8. Algorithm proposal for management of airway in panfacial fractures (Figure 1)

The first consideration should be the presence of an existing airway device from the acute or ongoing management of the patient. Where FONA is already in place, if this is a tracheostomy, either open or percutaneous, this can normally be utilized. It is preferable to change a cricothyroidotomy to a surgical tracheostomy. When an endotracheal tube is in situ, the decision to change this can follow the proposed algorithm, after due consideration of risks associated with tube changes if that is indicated.

The second consideration is the need for either prolonged intubation or repeated anaesthetics over a short period, in which case FONA access will be the most common choice, unless there is a specific contra-indication.

Where it is expected that a patient will be extubated immediately post-operatively, or shortly afterwards, and should not require multiple procedures, then an endotracheal tube will provide the simplest and safest option. The factors, which influence the choice of airway in this setting, include the need to establish the occlusion, the need to raise a coronal flap, and the involvement of the central nasal complex. In the unusual circumstance that the occlusion does not need to be established intra-operatively, a simple OTT will provide an easy and safe secure airway. Where the occlusion must be available, but no coronal flap is required and /or the central nasal complex is not displaced, then a nasal tube is a reasonable approach. Although there are concerns about using a NTT where there is significant skull base fractures, there does not appear to be a significant risk in this technique. A submental intubation is the best option where any of the aforementioned contra-indications to NTT exist.

4. Discussion

Obtaining and securing a definitive airway in patients with panfacial fractures can be challenging. During the acute management phase, the choices for establishing an airway might be constrained by the available expertise and equipment on hand. In patients with only maxillofacial injuries, the details of the injury can guide the choice of airway, but panfacial fractures are commonly associated with intra-cerebral and cervical spine injuries, and with polytrauma, necessitating either prolonged intubation or multiple anaesthetics over a relatively short period of time.

Where the occlusion needs to be assessed or intermaxillary fixation applied, the airway device should not traverse the mouth, unless it is placed retromolar. This method is however not routinely adopted because of difficulties placing it without interfering with the surgical access or reduction of the fractures.

To avoid interference with the occlusion, nasotracheal intubation has become the norm in the management of facial fractures. There continues to be concern about the use of NTI in skull base fractures although this has been shown to be safe when performed under fibreoptic guidance. The main problem is that the tube then passes over the top of the head, and interferes with coronal access, and its position makes reduction of nasal complex fractures more difficult.

Changing from a NTI to an OT tube intra-operatively can circumvent these problems. This can be done by completely removing the NTI and immediately re-inserting an OTT but carries the risks associated with an anaesthetised patient not having a secure airway during the change. This risk can be avoided by keeping the NTI and repositioning it trans-orally, but this technique can be troublesome there are significant soft tissue or mandibular / dentoalveolar injuries.

The advent of modern tools like video-laryngoscopes has substantially alleviated concerns related to achieving initial tracheal intubation amidst distorted anatomy and swelling. Additionally, these advancements facilitate the peri-operative tube exchange essential for different stages of panfacial fracture treatment.

Submental intubation is the most reported airway management in panfacial fractures as it is relatively safe and easy to perform. This technique provides unrestricted access to all areas of the facial skeleton unless extra-oral access to an anterior mandible fracture is required. Its main contra-indication is the need for prolonged intubation post-operatively.

Surgical tracheostomy remains the method of choice for securing the airway in patients in need of prolonged intubation or multiple anaesthetics over a relatively short space of time. Percutaneous tracheostomy is an alternative to open tracheostomy and boasts a slightly better complication rate but has a few additional contraindications. Cricothyroidotomy can be an alternative to tracheostomy and has low complications rates but is not normally considered for definitive airway management in trauma patients.

Staged surgery can avoid some of these controversies but needs to be explored.