Submitted:

12 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

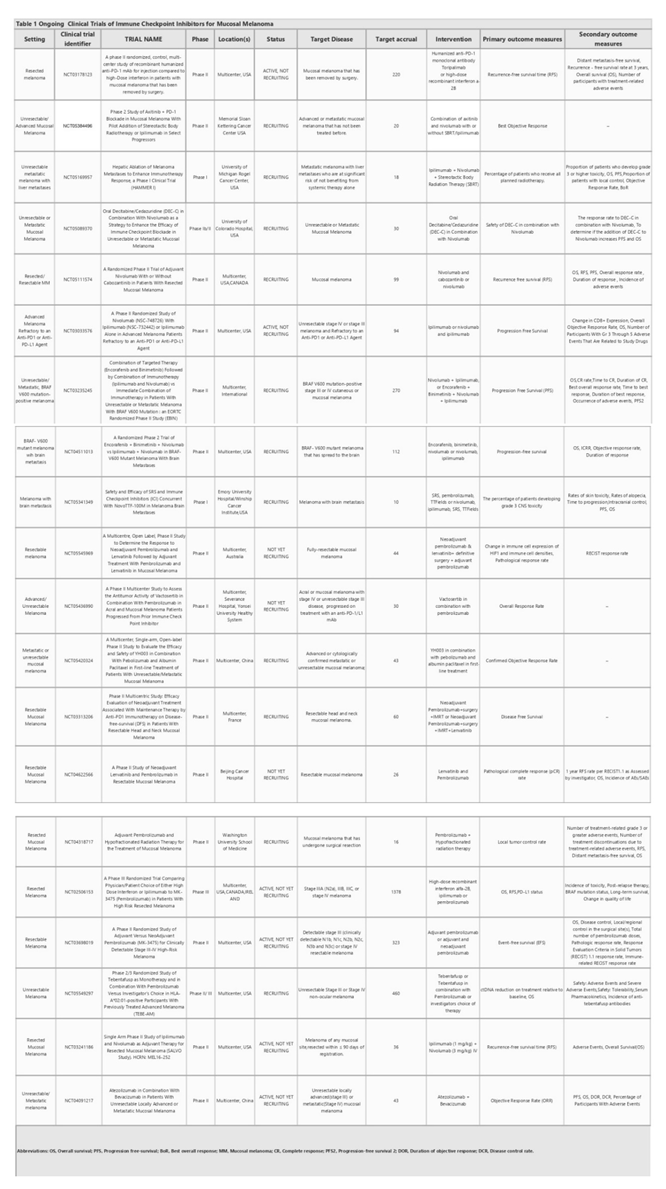

2. ICI therapy for OMM

3. Immunotherapy resistance

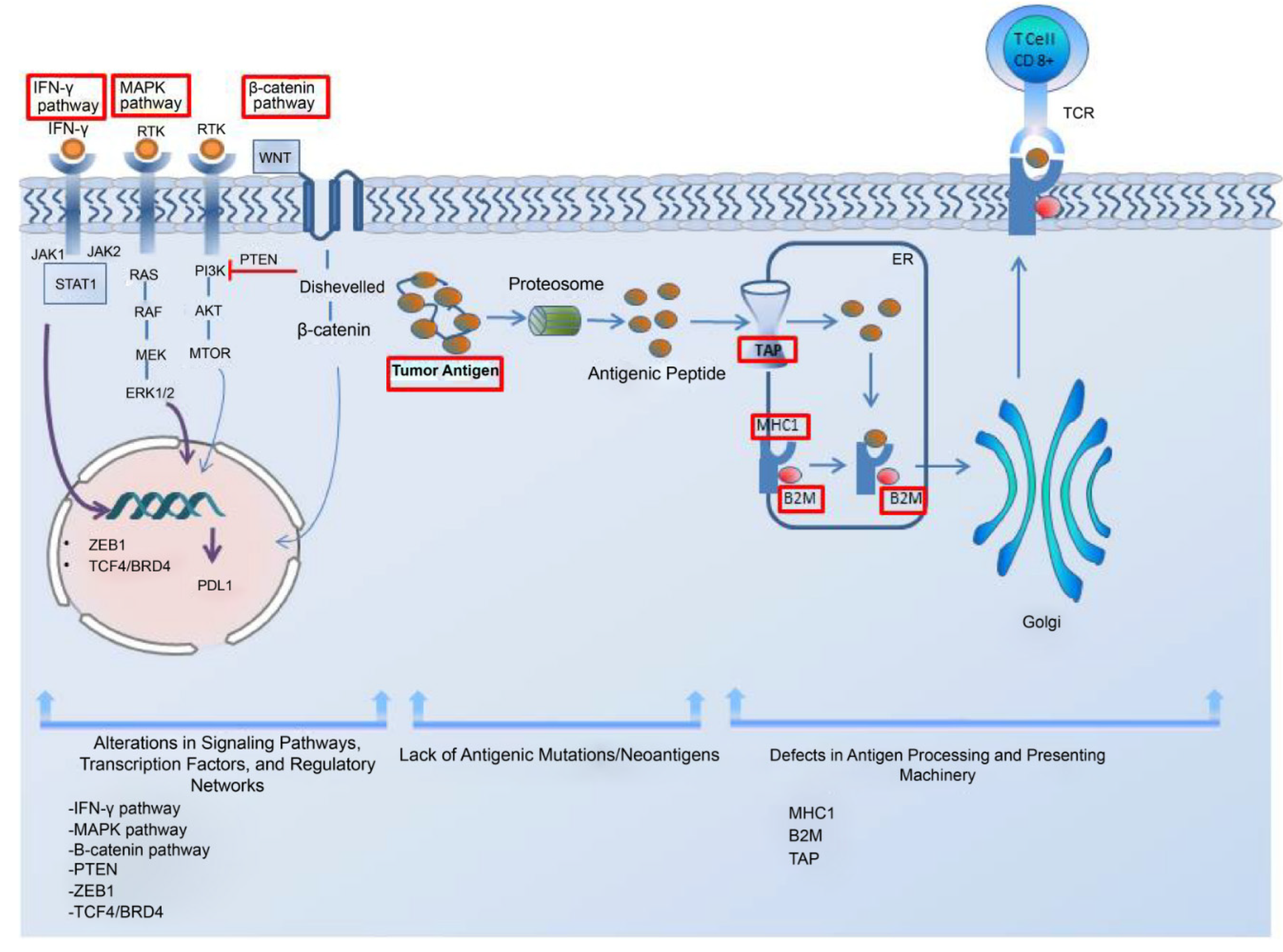

3.1. Mechanism of intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in melanoma

3.1.1. Impairments in the antigen processing-presenting machinery

3.1.2. Alterations in signaling pathways

3.1.3. Absence of tumor antigens and lack of antigenic mutation

3.1.4. Expression of PD-L1 and other contributing factors to resistance

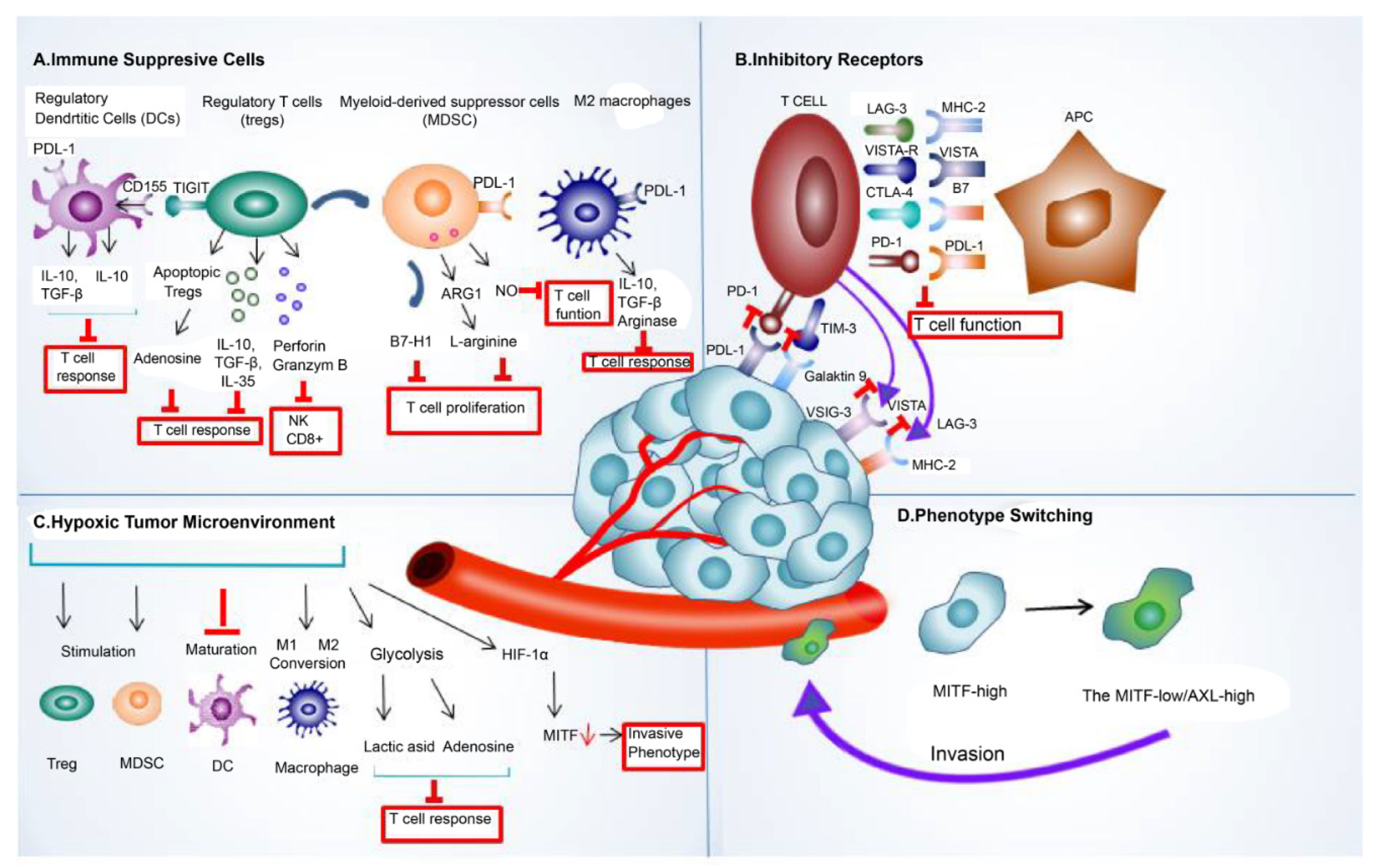

3.2. Role of the extrinsic tumor resistance mechanism

4. Conclusion and future directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Zito, P. M.; Brizuela, M.; Mazzoni, T. Oral Melanoma. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023.

- Warszawik-Hendzel, O.; Słowińska, M.; Olszewska, M.; Rudnicka, L. Melanoma of the Oral Cavity: Pathogenesis, Dermoscopy, Clinical Features, Staging and Management. J. Dermatol. Case Rep. 2014, 8 (3), 60–66. https://doi.org/10.3315/jdcr.2014.1175. [CrossRef]

- Rapidis, A. D.; Apostolidis, C.; Vilos, G.; Valsamis, S. Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Oral Mucosa. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61 (10), 1132–1139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00670-0. [CrossRef]

- Mascitti, M.; Santarelli, A.; Sartini, D.; Rubini, C.; Colella, G.; Salvolini, E.; Ganzetti, G.; Offidani, A.; Emanuelli, M. Analysis of Nicotinamide N-Methyltransferase in Oral Malignant Melanoma and Potential Prognostic Significance. Melanoma Res. 2019, 29 (2), 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0000000000000548. [CrossRef]

- Hicks, M. J.; Flaitz, C. M. Oral Mucosal Melanoma: Epidemiology and Pathobiology. Oral Oncol. 2000, 36 (2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1368-8375(99)00085-8. [CrossRef]

- Meleti, M.; Leemans, C. R.; Mooi, W. J.; Vescovi, P.; van der Waal, I. Oral Malignant Melanoma: A Review of the Literature. Oral Oncol. 2007, 43 (2), 116–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.04.001. [CrossRef]

- Nenclares, P.; Ap Dafydd, D.; Bagwan, I.; Begg, D.; Kerawala, C.; King, E.; Lingley, K.; Paleri, V.; Paterson, G.; Payne, M.; Silva, P.; Steven, N.; Turnbull, N.; Yip, K.; Harrington, K. J. Head and Neck Mucosal Melanoma: The United Kingdom National Guidelines. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 2020, 138, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.07.017. [CrossRef]

- Testori, A. A. E.; Blankenstein, S. A.; van Akkooi, A. C. J. Surgery for Metastatic Melanoma: An Evolving Concept. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21 (11), 98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-019-0847-6. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.-J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, G.-S.; Deng, X.-W.; Zhang, W.-J.; Lawrence, W. R.; Zou, L.; Zhang, X.-S.; Lu, L.-X. Efficacy and Safety of Primary Surgery with Postoperative Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Mucosal Melanoma: A Single-Arm Phase II Study. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 6985–6996. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S185017. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A. S.; Chapman, P. B. The History and Future of Chemotherapy for Melanoma. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2009, 23 (3), 583–x. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2009.03.006. [CrossRef]

- Luke, J. J.; Flaherty, K. T.; Ribas, A.; Long, G. V. Targeted Agents and Immunotherapies: Optimizing Outcomes in Melanoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14 (8), 463–482. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.43. [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S.; Flashner-Abramson, E.; Alkhatib, H.; Roy Chowdhury, S.; Adejumobi, I. A.; Vilenski, D.; Stefansky, S.; Rubinstein, A. M.; Kravchenko-Balasha, N. Overcoming Resistance to BRAFV600E Inhibition in Melanoma by Deciphering and Targeting Personalized Protein Network Alterations. Npj Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-021-00190-3. [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K. T.; Infante, J. R.; Daud, A.; Gonzalez, R.; Kefford, R. F.; Sosman, J.; Hamid, O.; Schuchter, L.; Cebon, J.; Ibrahim, N.; Kudchadkar, R.; Burris, H. A.; Falchook, G.; Algazi, A.; Lewis, K.; Long, G. V.; Puzanov, I.; Lebowitz, P.; Singh, A.; Little, S.; Sun, P.; Allred, A.; Ouellet, D.; Kim, K. B.; Patel, K.; Weber, J. Combined BRAF and MEK Inhibition in Melanoma with BRAF V600 Mutations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367 (18), 1694–1703. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Song, H.; Jv, H.; Guo, W.; Ren, G. The Clinical Significance of C-Kit Mutations in Metastatic Oral Mucosal Melanoma in China. Oncotarget 2017, 8 (47), 82661–82673. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.19746. [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. J. L.; Ribas, A. Targeted Therapy for Melanoma. Cancer Treat. Res. 2016, 167, 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22539-5_10. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S. A. IL-2: The First Effective Immunotherapy for Human Cancer. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 2014, 192 (12), 5451–5458. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1490019. [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M. B.; Lotze, M. T.; Dutcher, J. P.; Fisher, R. I.; Weiss, G.; Margolin, K.; Abrams, J.; Sznol, M.; Parkinson, D.; Hawkins, M.; Paradise, C.; Kunkel, L.; Rosenberg, S. A. High-Dose Recombinant Interleukin 2 Therapy for Patients with Metastatic Melanoma: Analysis of 270 Patients Treated between 1985 and 1993. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17 (7), 2105–2116. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Agata, Y.; Shibahara, K.; Honjo, T. Induced Expression of PD-1, a Novel Member of the Immunoglobulin Gene Superfamily, upon Programmed Cell Death. EMBO J. 1992, 11 (11), 3887–3895. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x. [CrossRef]

- Hamanishi, J.; Mandai, M.; Matsumura, N.; Abiko, K.; Baba, T.; Konishi, I. PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade in Cancer Treatment: Perspectives and Issues. Int J Clin Oncol 2016, 21 (3), 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-016-0959-z. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A. Tumor Immunotherapy Directed at PD-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366 (26), 2517–2519. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1205943. [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, K. M.; Freeman, G. J.; McDermott, D. F. The Next Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade in Melanoma. Clin. Ther. 2015, 37 (4), 764–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.02.018. [CrossRef]

- Iwai, Y.; Hamanishi, J.; Chamoto, K.; Honjo, T. Cancer Immunotherapies Targeting the PD-1 Signaling Pathway. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24 (1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-017-0329-9. [CrossRef]

- Brunet, J.-F.; Denizot, F.; Luciani, M.-F.; Roux-Dosseto, M.; Suzan, M.; Mattei, M.-G.; Golstein, P. A New Member of the Immunoglobulin Superfamily—CTLA-4. Nature 1987, 328 (6127), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1038/328267a0. [CrossRef]

- Leach, D. R.; Krummel, M. F.; Allison, J. P. Enhancement of Antitumor Immunity by CTLA-4 Blockade. Science 1996, 271 (5256), 1734–1736. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J. D.; Hodi, F. S.; Weber, J. S.; Allison, J. P.; Urba, W. J.; Robert, C.; O’Day, S. J.; Hoos, A.; Humphrey, R.; Berman, D. M.; Lonberg, N.; Korman, A. J. Development of Ipilimumab: A Novel Immunotherapeutic Approach for the Treatment of Advanced Melanoma. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1291 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12180. [CrossRef]

- Camacho, L. H. CTLA-4 Blockade with Ipilimumab: Biology, Safety, Efficacy, and Future Considerations. Cancer Med. 2015, 4 (5), 661–672. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.371. [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F. S.; O’Day, S. J.; McDermott, D. F.; Weber, R. W.; Sosman, J. A.; Haanen, J. B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J. C.; Akerley, W.; van den Eertwegh, A. J. M.; Lutzky, J.; Lorigan, P.; Vaubel, J. M.; Linette, G. P.; Hogg, D.; Ottensmeier, C. H.; Lebbé, C.; Peschel, C.; Quirt, I.; Clark, J. I.; Wolchok, J. D.; Weber, J. S.; Tian, J.; Yellin, M. J.; Nichol, G. M.; Hoos, A.; Urba, W. J. Improved Survival with Ipilimumab in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363 (8), 711–723. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [CrossRef]

- Seth, R.; Messersmith, H.; Kaur, V.; Kirkwood, J. M.; Kudchadkar, R.; McQuade, J. L.; Provenzano, A.; Swami, U.; Weber, J.; Alluri, K. C.; Agarwala, S.; Ascierto, P. A.; Atkins, M. B.; Davis, N.; Ernstoff, M. S.; Faries, M. B.; Gold, J. S.; Guild, S.; Gyorki, D. E.; Khushalani, N. I.; Meyers, M. O.; Robert, C.; Santinami, M.; Sehdev, A.; Sondak, V. K.; Spurrier, G.; Tsai, K. K.; van Akkooi, A.; Funchain, P. Systemic Therapy for Melanoma: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38 (33), 3947–3970. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.00198. [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, E. I.; Weirather, J. L.; Manos, M.; Quattrochi, B. J.; Sholl, L. M.; Brennick, R. C.; Bowling, P.; Bailey, N.; Magarace, L.; Ott, P. A.; Haq, R.; Izar, B.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Hodi, F. S. Characterization of Genetics in Patients with Mucosal Melanoma Treated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Med. 2021, 10 (8), 2627–2635. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3789. [CrossRef]

- Umeda, M.; Shimada, K. Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Oral Cavity—Its Histological Classification and Treatment. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1994, 32 (1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0266-4356(94)90172-4. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jing, G.; Lv, J.; Song, H.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Xia, W.; Wu, Y.; Ren, G.; Guo, W. Interferon-α-2b as an Adjuvant Therapy Prolongs Survival of Patients with Previously Resected Oral Muscosal Melanoma. Genet. Mol. Res. GMR 2015, 14 (4), 11944–11954. https://doi.org/10.4238/2015.October.5.8. [CrossRef]

- Long, G. V.; Hauschild, A.; Santinami, M.; Atkinson, V.; Mandalà, M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Larkin, J.; Nyakas, M.; Dutriaux, C.; Haydon, A.; Robert, C.; Mortier, L.; Schachter, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Lesimple, T.; Plummer, R.; Ji, R.; Zhang, P.; Mookerjee, B.; Legos, J.; Kefford, R.; Dummer, R.; Kirkwood, J. M. Adjuvant Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Stage III BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377 (19), 1813–1823. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708539. [CrossRef]

- Research, C. for D. E. and. FDA Approves Dabrafenib plus Trametinib for Adjuvant Treatment of Melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K Mutations. FDA 2019.

- Lyu, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, R.; Song, H.; Ren, G.; Guo, W. Mutation Scanning of BRAF, NRAS, KIT, and GNAQ/GNA11 in Oral Mucosal Melanoma: A Study of 57 Cases. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2016, 45 (4), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12358. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Feng, S.; Qi, L.; Li, X.; Ding, C. KIT, NRAS, BRAF and FMNL2 Mutations in Oral Mucosal Melanoma and a Systematic Review of the Literature. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15 (6), 9786–9792. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.8558. [CrossRef]

- Nebhan, C. A.; Johnson, D. B. Pembrolizumab in the Adjuvant Treatment of Melanoma: Efficacy and Safety. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2021, 21 (6), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2021.1882856. [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A. M. M.; Blank, C. U.; Mandala, M.; Long, G. V.; Atkinson, V.; Dalle, S.; Haydon, A.; Lichinitser, M.; Khattak, A.; Carlino, M. S.; Sandhu, S.; Larkin, J.; Puig, S.; Ascierto, P. A.; Rutkowski, P.; Schadendorf, D.; Koornstra, R.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Maio, M.; van den Eertwegh, A. J. M.; Grob, J.-J.; Gutzmer, R.; Jamal, R.; Lorigan, P.; Ibrahim, N.; Marreaud, S.; van Akkooi, A. C. J.; Suciu, S.; Robert, C. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Placebo in Resected Stage III Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378 (19), 1789–1801. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1802357. [CrossRef]

- Research, C. for D. E. and. FDA Approves Pembrolizumab for Adjuvant Treatment of Stage IIB or IIC Melanoma. FDA 2021.

- Wu, Y.; Wei, D.; Ren, G.; Guo, W. Chemotherapy in Combination with Anti-PD-1 Agents as Adjuvant Therapy for High-Risk Oral Mucosal Melanoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149 (6), 2293–2300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04090-2. [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A. M. M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Grob, J.-J.; Dummer, R.; Wolchok, J. D.; Schmidt, H.; Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Ascierto, P. A.; Richards, J. M.; Lebbé, C.; Ferraresi, V.; Smylie, M.; Weber, J. S.; Maio, M.; Konto, C.; Hoos, A.; de Pril, V.; Gurunath, R. K.; de Schaetzen, G.; Suciu, S.; Testori, A. Adjuvant Ipilimumab versus Placebo after Complete Resection of High-Risk Stage III Melanoma (EORTC 18071): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16 (5), 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70122-1. [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A. M. M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Grob, J.-J.; Dummer, R.; Wolchok, J. D.; Schmidt, H.; Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Ascierto, P. A.; Richards, J. M.; Lebbé, C.; Ferraresi, V.; Smylie, M.; Weber, J. S.; Maio, M.; Bastholt, L.; Mortier, L.; Thomas, L.; Tahir, S.; Hauschild, A.; Hassel, J. C.; Hodi, F. S.; Taitt, C.; de Pril, V.; de Schaetzen, G.; Suciu, S.; Testori, A. Prolonged Survival in Stage III Melanoma with Ipilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 375 (19), 1845–1855. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1611299. [CrossRef]

- Petrella, T. M.; Fletcher, G. G.; Knight, G.; McWhirter, E.; Rajagopal, S.; Song, X.; Baetz, T. D. Systemic Adjuvant Therapy for Adult Patients at High Risk for Recurrent Cutaneous or Mucosal Melanoma: An Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) Clinical Practice Guideline. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27 (1), e43–e52. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.27.5933. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D. A. Adjuvant Ipilimumab for Melanoma—The $1.8 Million per Patient Regimen. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3 (12), 1628–1629. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3123. [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Mandala, M.; Del Vecchio, M.; Gogas, H. J.; Arance, A. M.; Cowey, C. L.; Dalle, S.; Schenker, M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; Grob, J.-J.; Butler, M. O.; Middleton, M. R.; Maio, M.; Atkinson, V.; Queirolo, P.; Gonzalez, R.; Kudchadkar, R. R.; Smylie, M.; Meyer, N.; Mortier, L.; Atkins, M. B.; Long, G. V.; Bhatia, S.; Lebbé, C.; Rutkowski, P.; Yokota, K.; Yamazaki, N.; Kim, T. M.; de Pril, V.; Sabater, J.; Qureshi, A.; Larkin, J.; Ascierto, P. A. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in Resected Stage III or IV Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377 (19), 1824–1835. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709030. [CrossRef]

- Yi, J. H.; Yi, S. Y.; Lee, H. R.; Lee, S. I.; Lim, D. H.; Kim, J. H.; Park, K. W.; Lee, J. Dacarbazine-Based Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment in Noncutaneous Metastatic Melanoma: Multicenter, Retrospective Analysis in Asia. Melanoma Res. 2011, 21 (3), 223. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283457743. [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, H.; Payne, M. Combatting Mucosal Melanoma: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Melanoma Manag. 2018, 5 (3), MMT11. https://doi.org/10.2217/mmt-2018-0003. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Song, Z.; Chen, J.; Shepard, M. J.; Song, H.; Ren, G.; Li, Z.; Guo, W.; Zhuang, Z.; Shi, Y. Whole-Exome Sequencing of Oral Mucosal Melanoma Reveals Mutational Profile and Therapeutic Targets. J. Pathol. 2018, 244 (3), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.5017. [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S. P.; Larkin, J.; Sosman, J. A.; Lebbé, C.; Brady, B.; Neyns, B.; Schmidt, H.; Hassel, J. C.; Hodi, F. S.; Lorigan, P.; Savage, K. J.; Miller, W. H.; Mohr, P.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; Charles, J.; Kaatz, M.; Sznol, M.; Weber, J. S.; Shoushtari, A. N.; Ruisi, M.; Jiang, J.; Wolchok, J. D. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Alone or in Combination With Ipilimumab in Patients With Mucosal Melanoma: A Pooled Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35 (2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.9258. [CrossRef]

- Adisa, A. O.; Olawole, W. O.; Sigbeku, O. F. Oral Amelanotic Melanoma. Ann. Ib. Postgrad. Med. 2012, 10 (1), 6–8.

- Lamichhane, N. S.; An, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, W. Primary Malignant Mucosal Melanoma of the Upper Lip: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 499. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1459-3. [CrossRef]

- Khoury, Z. H.; Hausner, P. F.; Idzik-Starr, C. L.; Frykenberg, M. R. A.; Brooks, J. K.; Dyalram, D.; Basile, J. R.; Younis, R. H. Combination Nivolumab/Ipilimumab Immunotherapy For Melanoma With Subsequent Unexpected Cardiac Arrest: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Immunother. Hagerstown Md 1997 2019, 42 (8), 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1097/CJI.0000000000000282. [CrossRef]

- Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Ribas, A.; Hodi, F. S.; Walpole, E.; Daud, A.; Arance, A. S.; Brown, E.; Hoeller, C.; Mortier, L.; Schachter, J.; Long, J.; Ebbinghaus, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Butler, M. Antitumour Activity of Pembrolizumab in Advanced Mucosal Melanoma: A Post-Hoc Analysis of KEYNOTE-001, 002, 006. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119 (6), 670–674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0207-6. [CrossRef]

- Castaño, A.; Shah, S. S.; Cicero, G.; El Chaar, E. Primary Oral Melanoma - A Non-Surgical Approach to Treatment via Immunotherapy. Clin. Adv. Periodontics 2017, 7 (1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1902/cap.2016.160003. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Wargo, J. A.; Ribas, A. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell 2017, 168 (4), 707–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017. [CrossRef]

- Such, L.; Zhao, F.; Liu, D.; Thier, B.; Le-Trilling, V. T. K.; Sucker, A.; Coch, C.; Pieper, N.; Howe, S.; Bhat, H.; Kalkavan, H.; Ritter, C.; Brinkhaus, R.; Ugurel, S.; Köster, J.; Seifert, U.; Dittmer, U.; Schuler, M.; Lang, K. S.; Kufer, T. A.; Hartmann, G.; Becker, J. C.; Horn, S.; Ferrone, S.; Liu, D.; Van Allen, E. M.; Schadendorf, D.; Griewank, K.; Trilling, M.; Paschen, A. Targeting the Innate Immunoreceptor RIG-I Overcomes Melanoma-Intrinsic Resistance to T Cell Immunotherapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130 (8), 4266–4281. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI131572. [CrossRef]

- Paulson, K. G.; Voillet, V.; McAfee, M. S.; Hunter, D. S.; Wagener, F. D.; Perdicchio, M.; Valente, W. J.; Koelle, S. J.; Church, C. D.; Vandeven, N.; Thomas, H.; Colunga, A. G.; Iyer, J. G.; Yee, C.; Kulikauskas, R.; Koelle, D. M.; Pierce, R. H.; Bielas, J. H.; Greenberg, P. D.; Bhatia, S.; Gottardo, R.; Nghiem, P.; Chapuis, A. G. Acquired Cancer Resistance to Combination Immunotherapy from Transcriptional Loss of Class I HLA. Nat Commun 2018, 9 (1), 3868. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06300-3. [CrossRef]

- Sade-Feldman, M.; Jiao, Y. J.; Chen, J. H.; Rooney, M. S.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Eliane, J.-P.; Bjorgaard, S. L.; Hammond, M. R.; Vitzthum, H.; Blackmon, S. M.; Frederick, D. T.; Hazar-Rethinam, M.; Nadres, B. A.; Van Seventer, E. E.; Shukla, S. A.; Yizhak, K.; Ray, J. P.; Rosebrock, D.; Livitz, D.; Adalsteinsson, V.; Getz, G.; Duncan, L. M.; Li, B.; Corcoran, R. B.; Lawrence, D. P.; Stemmer-Rachamimov, A.; Boland, G. M.; Landau, D. A.; Flaherty, K. T.; Sullivan, R. J.; Hacohen, N. Resistance to Checkpoint Blockade Therapy through Inactivation of Antigen Presentation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8 (1), 1136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01062-w. [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.; Cardoso, A. P.; Gonçalves, R. M.; Serre, K.; Oliveira, M. J. Interferon-Gamma at the Crossroads of Tumor Immune Surveillance or Evasion. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 847. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00847. [CrossRef]

- Rodig, S. J.; Gusenleitner, D.; Jackson, D. G.; Gjini, E.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Jin, C.; Chang, H.; Lovitch, S. B.; Horak, C.; Weber, J. S.; Weirather, J. L.; Wolchok, J. D.; Postow, M. A.; Pavlick, A. C.; Chesney, J.; Hodi, F. S. MHC Proteins Confer Differential Sensitivity to CTLA-4 and PD-1 Blockade in Untreated Metastatic Melanoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10 (450), eaar3342. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aar3342. [CrossRef]

- Karachaliou, N.; Gonzalez-Cao, M.; Crespo, G.; Drozdowskyj, A.; Aldeguer, E.; Gimenez-Capitan, A.; Teixido, C.; Molina-Vila, M. A.; Viteri, S.; De Los Llanos Gil, M.; Algarra, S. M.; Perez-Ruiz, E.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; Rodriguez-Abreu, D.; Blanco, R.; Puertolas, T.; Royo, M. A.; Rosell, R. Interferon Gamma, an Important Marker of Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Melanoma Patients. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2018, 10, 1758834017749748. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758834017749748. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Shi, L. Z.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; Xiong, L.; He, Q.; Chen, T.; Roszik, J.; Bernatchez, C.; Woodman, S. E.; Chen, P.-L.; Hwu, P.; Allison, J. P.; Futreal, A.; Wargo, J. A.; Sharma, P. Loss of IFN-γ Pathway Genes in Tumor Cells as a Mechanism of Resistance to Anti-CTLA-4 Therapy. Cell 2016, 167 (2), 397-404.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.069. [CrossRef]

- Benci, J. L.; Xu, B.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, T.; Dada, H.; Victor, C. T.-S.; Cucolo, L.; Lee, D. S. M.; Pauken, K. E.; Huang, A. C.; Gangadhar, T. C.; Amaravadi, R. K.; Schuchter, L. M.; Feldman, M. D.; Ishwaran, H.; Vonderheide, R. H.; Maity, A.; Wherry, E. J.; Minn, A. J. Tumor Interferon Signaling Regulates a Multigenic Resistance Program to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cell 2016, 167 (6), 1540-1554.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.022. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhou, J.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Wargo, J.; Hodi, F. S. The Activation of MAPK in Melanoma Cells Resistant to BRAF Inhibition Promotes PD-L1 Expression That Is Reversible by MEK and PI3K Inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2013, 19 (3), 598–609. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2731. [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, J.; Landsberg, J.; Schmid-Burgk, J. L.; Ramis, B. B.; Bald, T.; Glodde, N.; Lopez-Ramos, D.; Young, A.; Ngiow, S. F.; Nettersheim, D.; Schorle, H.; Quast, T.; Kolanus, W.; Schadendorf, D.; Long, G. V.; Madore, J.; Scolyer, R. A.; Ribas, A.; Smyth, M. J.; Tumeh, P. C.; Tüting, T.; Hölzel, M. MAPK Signaling and Inflammation Link Melanoma Phenotype Switching to Induction of CD73 during Immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2017, 77 (17), 4697–4709. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0395. [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Bao, R.; Gajewski, T. F. Melanoma-Intrinsic β-Catenin Signalling Prevents Anti-Tumour Immunity. Nature 2015, 523 (7559), 231–235. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14404. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, A. X.; Gartrell, R. D.; Silverman, A. M.; Aparicio, L.; Chu, T.; Bordbar, D.; Shan, D.; Samanamud, J.; Mahajan, A.; Filip, I.; Orenbuch, R.; Goetz, M.; Yamaguchi, J. T.; Cloney, M.; Horbinski, C.; Lukas, R. V.; Raizer, J.; Rae, A. I.; Yuan, J.; Canoll, P.; Bruce, J. N.; Saenger, Y. M.; Sims, P.; Iwamoto, F. M.; Sonabend, A. M.; Rabadan, R. Immune and Genomic Correlates of Response to Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Glioblastoma. Nat. Med. 2019, 25 (3), 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0349-y. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Chen, J. Q.; Liu, C.; Malu, S.; Creasy, C.; Tetzlaff, M. T.; Xu, C.; McKenzie, J. A.; Zhang, C.; Liang, X.; Williams, L. J.; Deng, W.; Chen, G.; Mbofung, R.; Lazar, A. J.; Torres-Cabala, C. A.; Cooper, Z. A.; Chen, P.-L.; Tieu, T. N.; Spranger, S.; Yu, X.; Bernatchez, C.; Forget, M.-A.; Haymaker, C.; Amaria, R.; McQuade, J. L.; Glitza, I. C.; Cascone, T.; Li, H. S.; Kwong, L. N.; Heffernan, T. P.; Hu, J.; Bassett, R. L.; Bosenberg, M. W.; Woodman, S. E.; Overwijk, W. W.; Lizée, G.; Roszik, J.; Gajewski, T. F.; Wargo, J. A.; Gershenwald, J. E.; Radvanyi, L.; Davies, M. A.; Hwu, P. Loss of PTEN Promotes Resistance to T Cell-Mediated Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6 (2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0283. [CrossRef]

- Plaschka, M.; Benboubker, V.; Grimont, M.; Berthet, J.; Tonon, L.; Lopez, J.; Le-Bouar, M.; Balme, B.; Tondeur, G.; de la Fouchardière, A.; Larue, L.; Puisieux, A.; Grinberg-Bleyer, Y.; Bendriss-Vermare, N.; Dubois, B.; Caux, C.; Dalle, S.; Caramel, J. ZEB1 Transcription Factor Promotes Immune Escape in Melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10 (3), e003484. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2021-003484. [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, T.; Noguchi, T.; Sugiyama, D.; Kanada, Y.; Fujimaki, K.; Ito, S.; Gotoh, M.; Nishikawa, H. Newly Emerged Immunogenic Neoantigens in Established Tumors Enable Hosts to Regain Immunosurveillance in a T-Cell-Dependent Manner. Int. Immunol. 2021, 33 (1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxaa049. [CrossRef]

- Yc, L.; Z, Z.; Fj, L.; Jj, G.; Td, P.; Pf, R.; Sa, R. Direct Identification of Neoantigen-Specific TCRs from Tumor Specimens by High-Throughput Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9 (7). https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2021-002595. [CrossRef]

- Van Allen, E. M.; Miao, D.; Schilling, B.; Shukla, S. A.; Blank, C.; Zimmer, L.; Sucker, A.; Hillen, U.; Foppen, M. H. G.; Goldinger, S. M.; Utikal, J.; Hassel, J. C.; Weide, B.; Kaehler, K. C.; Loquai, C.; Mohr, P.; Gutzmer, R.; Dummer, R.; Gabriel, S.; Wu, C. J.; Schadendorf, D.; Garraway, L. A. Genomic Correlates of Response to CTLA-4 Blockade in Metastatic Melanoma. Science 2015, 350 (6257), 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad0095. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. R.; Fisher, D. E. Epitope Spreading and the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Cancer. Int. J. Oncol. Res. 2021, 4 (1), 029. https://doi.org/10.23937/2643-4563/1710029. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R. W.; Barbie, D. A.; Flaherty, K. T. Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118 (1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.434. [CrossRef]

- Yadollahi, P.; Jeon, Y.-K.; Ng, W. L.; Choi, I. Current Understanding of Cancer-Intrinsic PD-L1: Regulation of Expression and Its Protumoral Activity. BMB Rep. 2021, 54 (1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.5483/BMBRep.2021.54.1.241. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, A.; Rodger, E. J.; Motwani, J.; Gimenez, G.; Stockwell, P. A.; Parry, M.; Hersey, P.; Chatterjee, A.; Eccles, M. R. Transcriptional Reprogramming and Constitutive PD-L1 Expression in Melanoma Are Associated with Dedifferentiation and Activation of Interferon and Tumour Necrosis Factor Signalling Pathways. Cancers 2021, 13 (17), 4250. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13174250. [CrossRef]

- Maitituoheti, M.; Shi, A.; Tang, M.; Ho, L.-L.; Terranova, C.; Galani, K.; Keung, E. Z.; Creasy, C. A.; Wu, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, N.; Singh, A. K.; Chaudhri, A.; Anvar, N. E.; Tarantino, G.; Yang, J.; Sarkar, S.; Jiang, S.; Malke, J.; Haydu, L.; Burton, E.; Davies, M. A.; Gershenwald, J. E.; Hwu, P.; Lazar, A.; Cheah, J. H.; Soule, C. K.; Levine, S. S.; Bernatchez, C.; Saladi, S. V.; Liu, D.; Wargo, J.; Boland, G. M.; Kellis, M.; Rai, K. Enhancer Reprogramming in Melanoma Immune Checkpoint Therapy Resistance. bioRxiv September 3, 2022, p 2022.08.31.506051. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.31.506051. [CrossRef]

- Pozniak, J.; Pedri, D.; Landeloos, E.; Herck, Y. V.; Antoranz, A.; Karras, P.; Nowosad, A.; Makhzami, S.; Bervoets, G.; Dewaele, M.; Vanwynsberghe, L.; Cinque, S.; Kint, S.; Vandereyken, K.; Voet, T.; Vernaillen, F.; Annaert, W.; Lambrechts, D.; Boecxstaens, V.; Oord, J. van den; Bosisio, F.; Leucci, E.; Rambow, F.; Bechter, O.; Marine, J.-C. A TCF4/BRD4-Dependent Regulatory Network Confers Cross-Resistance to Targeted and Immune Checkpoint Therapy in Melanoma. bioRxiv August 13, 2022, p 2022.08.11.502598. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.11.502598. [CrossRef]

- Markovits, E.; Harush, O.; Baruch, E. N.; Shulman, E. D.; Debby, A.; Itzhaki, O.; Anafi, L.; Danilevsky, A.; Shomron, N.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Asher, N.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Schachter, J.; Barshack, I.; Geiger, T.; Elkon, R.; Besser, M. J.; Markel, G. MYC Induces Immunotherapy and IFNγ Resistance Through Downregulation of JAK2. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2023, 11 (7), 909–924. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-22-0184. [CrossRef]

- Kuehm, L. M.; Khojandi, N.; Piening, A.; Klevorn, L. E.; Geraud, S. C.; McLaughlin, N. R.; Griffett, K.; Burris, T. P.; Pyles, K. D.; Nelson, A. M.; Preuss, M. L.; Bockerstett, K. A.; Donlin, M. J.; McCommis, K. S.; DiPaolo, R. J.; Teague, R. M. Fructose Promotes Cytoprotection in Melanoma Tumors and Resistance to Immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2021, 9 (2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-0396. [CrossRef]

- Fox, D. B.; Ebright, R. Y.; Hong, X.; Russell, H. C.; Guo, H.; LaSalle, T. J.; Wittner, B. S.; Poux, N.; Vuille, J. A.; Toner, M.; Hacohen, N.; Boland, G. M.; Sen, D. R.; Sullivan, R. J.; Maheswaran, S.; Haber, D. A. Downregulation of KEAP1 in Melanoma Promotes Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Npj Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-023-00362-3. [CrossRef]

- Shields, B. D.; Koss, B.; Taylor, E. M.; Storey, A. J.; West, K. L.; Byrum, S. D.; Mackintosh, S. G.; Edmondson, R.; Mahmoud, F.; Shalin, S. C.; Tackett, A. J. Loss of E-Cadherin Inhibits CD103 Antitumor Activity and Reduces Checkpoint Blockade Responsiveness in Melanoma. Cancer Res. 2019, 79 (6), 1113–1123. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1722. [CrossRef]

- Mangani, D.; Huang, L.; Singer, M.; Li, R.; Barilla, R.; Escobar, G.; Tooley, K.; Cheng, H.; Delaney, C.; Newcomer, K.; Nyman, J.; Marjanovic, N.; Nevin, J.; Rozenblatt-Rosen, O.; Kuchroo, V.; Regev, A.; Anderson, A. 964 Dynamic Immune Landscapes during Melanoma Progression Reveal a Role for Endogenous Opioids in Driving T Cell Dysfunction. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10 (Suppl 2). https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2022-SITC2022.0964. [CrossRef]

- Simiczyjew, A.; Dratkiewicz, E.; Mazurkiewicz, J.; Ziętek, M.; Matkowski, R.; Nowak, D. The Influence of Tumor Microenvironment on Immune Escape of Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (21), 8359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218359. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. F. M.; Nierkens, S.; Figdor, C. G.; de Vries, I. J. M.; Adema, G. J. Regulatory T Cells in Melanoma: The Final Hurdle towards Effective Immunotherapy? Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13 (1), e32-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70155-3. [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, T.; Kambayashi, Y.; Aiba, S. Crosstalk between Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) and Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) during Melanoma Growth. Oncoimmunology 2012, 1 (8), 1433–1434. https://doi.org/10.4161/onci.21176. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, R.; Elkord, E. Treg-Mediated Acquired Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2019, 457, 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2019.05.003. [CrossRef]

- Beier, U. H. Apoptotic Regulatory T Cells Retain Suppressive Function through Adenosine. Cell Metab. 2018, 27 (1), 5–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.12.013. [CrossRef]

- Maj, T.; Wang, W.; Crespo, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Wei, S.; Zhao, L.; Vatan, L.; Shao, I.; Szeliga, W.; Lyssiotis, C.; Liu, J. R.; Kryczek, I.; Zou, W. Oxidative Stress Controls Regulatory T Cell Apoptosis and Suppressor Activity and PD-L1-Blockade Resistance in Tumor. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18 (12), 1332–1341. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3868. [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, T.; Mahnke, K.; Enk, A. H. Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells and Their Role in Tolerance Induction in Cancer. Journal of Dermatological Science 2010, 59 (1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.05.001. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Cagnon, L.; Costa-Nunes, C. M.; Baumgaertner, P.; Montandon, N.; Leyvraz, L.; Michielin, O.; Romano, E.; Speiser, D. E. Frequencies of Circulating MDSC Correlate with Clinical Outcome of Melanoma Patients Treated with Ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014, 63 (3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-013-1508-5. [CrossRef]

- Sade-Feldman, M.; Kanterman, J.; Klieger, Y.; Ish-Shalom, E.; Olga, M.; Saragovi, A.; Shtainberg, H.; Lotem, M.; Baniyash, M. Clinical Significance of Circulating CD33+CD11b+HLA-DR− Myeloid Cells in Patients with Stage IV Melanoma Treated with Ipilimumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22 (23), 5661–5672. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-3104. [CrossRef]

- Weide, B.; Martens, A.; Zelba, H.; Stutz, C.; Derhovanessian, E.; Di Giacomo, A. M.; Maio, M.; Sucker, A.; Schilling, B.; Schadendorf, D.; Büttner, P.; Garbe, C.; Pawelec, G. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Predict Survival of Patients with Advanced Melanoma: Comparison with Regulatory T Cells and NY-ESO-1- or Melan-A–Specific T Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20 (6), 1601–1609. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2508. [CrossRef]

- Tirosh, I.; Izar, B.; Prakadan, S. M.; Wadsworth, M. H.; Treacy, D.; Trombetta, J. J.; Rotem, A.; Rodman, C.; Lian, C.; Murphy, G.; Fallahi-Sichani, M.; Dutton-Regester, K.; Lin, J.-R.; Cohen, O.; Shah, P.; Lu, D.; Genshaft, A. S.; Hughes, T. K.; Ziegler, C. G. K.; Kazer, S. W.; Gaillard, A.; Kolb, K. E.; Villani, A.-C.; Johannessen, C. M.; Andreev, A. Y.; Van Allen, E. M.; Bertagnolli, M.; Sorger, P. K.; Sullivan, R. J.; Flaherty, K. T.; Frederick, D. T.; Jané-Valbuena, J.; Yoon, C. H.; Rozenblatt-Rosen, O.; Shalek, A. K.; Regev, A.; Garraway, L. A. Dissecting the Multicellular Ecosystem of Metastatic Melanoma by Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Science 2016, 352 (6282), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad0501. [CrossRef]

- Diazzi, S.; Tartare-Deckert, S.; Deckert, M. The Mechanical Phenotypic Plasticity of Melanoma Cell: An Emerging Driver of Therapy Cross-Resistance. Oncogenesis 2023, 12 (1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41389-023-00452-8. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Shklovskaya, E.; Lim, S. Y.; Carlino, M. S.; Menzies, A. M.; Stewart, A.; Pedersen, B.; Irvine, M.; Alavi, S.; Yang, J. Y. H.; Strbenac, D.; Saw, R. P. M.; Thompson, J. F.; Wilmott, J. S.; Scolyer, R. A.; Long, G. V.; Kefford, R. F.; Rizos, H. Transcriptional Downregulation of MHC Class I and Melanoma De- Differentiation in Resistance to PD-1 Inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 1897. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15726-7. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S. M.; Gimenez, G.; Stockwell, P. A.; Tsai, P.; Print, C. G.; Rys, J.; Cybulska-Stopa, B.; Ratajska, M.; Harazin-Lechowska, A.; Almomani, S.; Jackson, C.; Chatterjee, A.; Eccles, M. R. Innate Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Resistance Is Associated with Melanoma Sub-Types Exhibiting Invasive and de-Differentiated Gene Expression Signatures. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.955063. [CrossRef]

- Munn, D. H.; Mellor, A. L. Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and Tumor-Induced Tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117 (5), 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI31178. [CrossRef]

- Uyttenhove, C.; Pilotte, L.; Théate, I.; Stroobant, V.; Colau, D.; Parmentier, N.; Boon, T.; Van den Eynde, B. J. Evidence for a Tumoral Immune Resistance Mechanism Based on Tryptophan Degradation by Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase. Nat. Med. 2003, 9 (10), 1269–1274. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm934. [CrossRef]

- Holmgaard, R. B.; Zamarin, D.; Munn, D. H.; Wolchok, J. D.; Allison, J. P. Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase Is a Critical Resistance Mechanism in Antitumor T Cell Immunotherapy Targeting CTLA-4. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210 (7), 1389–1402. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20130066. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T. C.; Hamid, O.; Smith, D. C.; Bauer, T. M.; Wasser, J. S.; Olszanski, A. J.; Luke, J. J.; Balmanoukian, A. S.; Schmidt, E. V.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, X.; Maleski, J.; Leopold, L.; Gajewski, T. F. Epacadostat Plus Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors: Phase I Results From a Multicenter, Open-Label Phase I/II Trial (ECHO-202/KEYNOTE-037). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36 (32), 3223–3230. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9602. [CrossRef]

- Long, G. V.; Dummer, R.; Hamid, O.; Gajewski, T. F.; Caglevic, C.; Dalle, S.; Arance, A.; Carlino, M. S.; Grob, J.-J.; Kim, T. M.; Demidov, L.; Robert, C.; Larkin, J.; Anderson, J. R.; Maleski, J.; Jones, M.; Diede, S. J.; Mitchell, T. C. Epacadostat plus Pembrolizumab versus Placebo plus Pembrolizumab in Patients with Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma (ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252): A Phase 3, Randomised, Double-Blind Study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20 (8), 1083–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30274-8. [CrossRef]

- Iga, N.; Otsuka, A.; Hirata, M.; Kataoka, T. R.; Irie, H.; Nakashima, C.; Matsushita, S.; Uchi, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Funakoshi, T.; Fujisawa, Y.; Yoshino, K.; Fujimura, T.; Hata, H.; Ishida, Y.; Kabashima, K. Variable Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase Expression in Acral/Mucosal Melanoma and Its Possible Link to Immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110 (11), 3434–3441. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.14195. [CrossRef]

- Georgoudaki, A.-M.; Prokopec, K. E.; Boura, V. F.; Hellqvist, E.; Sohn, S.; Östling, J.; Dahan, R.; Harris, R. A.; Rantalainen, M.; Klevebring, D.; Sund, M.; Brage, S. E.; Fuxe, J.; Rolny, C.; Li, F.; Ravetch, J. V.; Karlsson, M. C. I. Reprogramming Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Antibody Targeting Inhibits Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cell Rep. 2016, 15 (9), 2000–2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.084. [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Ji, Q. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Regulate PD-1/PD-L1 Immunosuppression. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 874589. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.874589. [CrossRef]

- Arozarena, I.; Wellbrock, C. Phenotype Plasticity as Enabler of Melanoma Progression and Therapy Resistance. Nat Rev Cancer 2019, 19 (7), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0154-4. [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. J.; Vignali, P. D. A.; Mullett, S. J.; Overacre-Delgoffe, A. E.; Peralta, R. M.; Grebinoski, S.; Menk, A. V.; Rittenhouse, N. L.; DePeaux, K.; Whetstone, R. D.; Vignali, D. A. A.; Hand, T. W.; Poholek, A. C.; Morrison, B. M.; Rothstein, J. D.; Wendell, S. G.; Delgoffe, G. M. Metabolic Support of Tumour-Infiltrating Regulatory T Cells by Lactic Acid. Nature 2021, 591 (7851), 645–651. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03045-2. [CrossRef]

- Daneshmandi, S.; Wegiel, B.; Seth, P. Blockade of Lactate Dehydrogenase-A (LDH-A) Improves Efficacy of Anti-Programmed Cell Death-1 (PD-1) Therapy in Melanoma. Cancers 2019, 11 (4), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11040450. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A. R.; Liu, A. J.; Pudakalakatti, S.; Dutta, P.; Jayaprakash, P.; Bartkowiak, T.; Ager, C. R.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Reuben, A.; Cooper, Z. A.; Ivan, C.; Ju, Z.; Nwajei, F.; Wang, J.; Davies, M. A.; Davis, R. E.; Wargo, J. A.; Bhattacharya, P. K.; Hong, D. S.; Curran, M. A. Melanoma Evolves Complete Immunotherapy Resistance through the Acquisition of a Hypermetabolic Phenotype. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8 (11), 1365–1380. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0005. [CrossRef]

- Dyck, L.; Mills, K. H. G. Immune Checkpoints and Their Inhibition in Cancer and Infectious Diseases. European Journal of Immunology 2017, 47 (5), 765–779. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201646875. [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Okamura, R.; Kumaki, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Nikanjam, M.; Eskander, R.; Goodman, A.; Lee, S.; Glenn, S. T.; Dressman, D.; Papanicolau-Sengos, A.; Lenzo, F. L.; Morrison, C.; Kurzrock, R. Expression of TIM3/VISTA Checkpoints and the CD68 Macrophage-Associated Marker Correlates with Anti-PD1/PDL1 Resistance: Implications of Immunogram Heterogeneity. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9 (1), 1708065. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2019.1708065. [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, S.; Inozume, T.; Kawazu, M.; Ueno, T.; Nagasaki, J.; Tanji, E.; Honobe, A.; Ohnuma, T.; Kawamura, T.; Umeda, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Kawasaki, T.; Kiniwa, Y.; Yamasaki, O.; Fukushima, S.; Ikehara, Y.; Mano, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Nishikawa, H.; Matsue, H.; Togashi, Y. TIGIT/CD155 Axis Mediates Resistance to Immunotherapy in Patients with Melanoma with the Inflamed Tumor Microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9 (11), e003134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2021-003134. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, H.; Fukuda, M.; Konno, Y.; Takano, H. Abscopal Effect of Radiation Therapy after Nivolumab Monotherapy in a Patient with Oral Mucosal Melanoma: A Case Report. Oral Oncol. 2020, 108, 104919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104919. [CrossRef]

- Vera Aguilera, J.; Paludo, J.; McWilliams, R. R.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Kumar, A. B.; Failing, J.; Kottschade, L. A.; Block, M. S.; Markovic, S. N.; Dong, H.; Dronca, R. S.; Yan, Y. Chemo-Immunotherapy Combination after PD-1 Inhibitor Failure Improves Clinical Outcomes in Metastatic Melanoma Patients. Melanoma Res. 2020, 30 (4), 364–375. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0000000000000669. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, B.; Han, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, G.; Ye, H.; Yuan, J.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Tian, L.; Wang, H.; Lu, S. Surgery After Conversion Therapy With PD-1 Inhibitors Plus Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Are Effective and Safe for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Pilot Study of Ten Patients. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11.

- Fukuhara, H.; Ino, Y.; Todo, T. Oncolytic Virus Therapy: A New Era of Cancer Treatment at Dawn. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107 (10), 1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13027. [CrossRef]

- Sivanandam, V.; LaRocca, C. J.; Chen, N. G.; Fong, Y.; Warner, S. G. Oncolytic Viruses and Immune Checkpoint Inhibition: The Best of Both Worlds. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 2019, 13, 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2019.04.003. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Tateishi, R.; Iwai, M.; Koike, K.; Todo, T. Neoadjuvant Use of Oncolytic Herpes Virus G47Δ Enhances the Antitumor Efficacy of Radiofrequency Ablation. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2020, 18, 535–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2020.08.010. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Dummer, R.; Puzanov, I.; VanderWalde, A.; Andtbacka, R. H. I.; Michielin, O.; Olszanski, A. J.; Malvehy, J.; Cebon, J.; Fernandez, E.; Kirkwood, J. M.; Gajewski, T. F.; Chen, L.; Gorski, K. S.; Anderson, A. A.; Diede, S. J.; Lassman, M. E.; Gansert, J.; Hodi, F. S.; Long, G. V. Oncolytic Virotherapy Promotes Intratumoral T Cell Infiltration and Improves Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cell 2017, 170 (6), 1109-1119.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027. [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, K.; Iwai, M.; Ito, H.; Tanaka, M.; Seto, Y.; Todo, T. Oncolytic Herpes Virus G47Δ Works Synergistically with CTLA-4 Inhibition via Dynamic Intratumoral Immune Modulation. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 2021, 22, 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2021.05.004. [CrossRef]

- Uchihashi, T.; Nakahara, H.; Fukuhara, H.; Iwai, M.; Ito, H.; Sugauchi, A.; Tanaka, M.; Kogo, M.; Todo, T. Oncolytic Herpes Virus G47Δ Injected into Tongue Cancer Swiftly Traffics in Lymphatics and Suppresses Metastasis. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 2021, 22, 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2021.06.008. [CrossRef]

- Batlle, E.; Massagué, J. Transforming Grown Factor-β Signaling in Immunity and Cancer. Immunity 2019, 50 (4), 924–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.024. [CrossRef]

- Mariathasan, S.; Turley, S. J.; Nickles, D.; Castiglioni, A.; Yuen, K.; Wang, Y.; Kadel III, E. E.; Koeppen, H.; Astarita, J. L.; Cubas, R.; Jhunjhunwala, S.; Banchereau, R.; Yang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Chalouni, C.; Ziai, J.; Şenbabaoğlu, Y.; Santoro, S.; Sheinson, D.; Hung, J.; Giltnane, J. M.; Pierce, A. A.; Mesh, K.; Lianoglou, S.; Riegler, J.; Carano, R. A. D.; Eriksson, P.; Höglund, M.; Somarriba, L.; Halligan, D. L.; van der Heijden, M. S.; Loriot, Y.; Rosenberg, J. E.; Fong, L.; Mellman, I.; Chen, D. S.; Green, M.; Derleth, C.; Fine, G. D.; Hegde, P. S.; Bourgon, R.; Powles, T. TGFβ Attenuates Tumour Response to PD-L1 Blockade by Contributing to Exclusion of T Cells. Nature 2018, 554 (7693), 544–548. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25501. [CrossRef]

- Kodama, S.; Podyma-Inoue, K. A.; Uchihashi, T.; Kurioka, K.; Takahashi, H.; Sugauchi, A.; Takahashi, K.; Inubushi, T.; Kogo, M.; Tanaka, S.; Watabe, T. Progression of Melanoma Is Suppressed by Targeting All Transforming Growth Factor-β Isoforms with an Fc Chimeric Receptor. Oncol Rep 2021, 46 (3), 197. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2021.8148. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).