1. Introduction

Emotions play an important role in a person's life from its very beginning to the end. Understanding emotions becomes indispensable for people's daily activities, in organizing adaptive behavior and determining the functional state of the organism, in human–computer interaction (HCI), etc. To provide natural and user-adaptable interaction, HCI systems need to automatically recognize persons' emotions.

The development of speech emotion recognition (SER) systems has been a hot topic of research in the field of HCI for the past two decades. Most of these studies focus on recognizing emotions from adult’s speech [

1,

2] and only a few from children's speech [

3,

4]. This follows from the fact that large annotated datasets (corpus) of children's speech, especially audiovisual speech, are still not publicly available in the research community, and this forces most researchers to focus on emotion recognition for adults.

Nevertheless, children are potentially the largest class of users of most HCI applications, especially in education and entertainment (edutainment) [

5]. Therefore, it is important to study how emotions are expressed by children and can be automatically processed by computers.

The task of creating automatic emotion recognition systems in a person’s speech is not trivial, especially considering the differences in acoustic features for different genders [

6], age groups [

7], languages [

6,

8], cultures [

9], and developmental [

10] features. For example, the authors of [

11] report that the average accuracy of speech emotion recognition is 93.3%, 89.4%, and 83.3% for men, women and children, respectively. The lower accuracy of recognizing emotions in children's speech may be due to the fact that children interact with the computer differently than adults as they are still learning the linguistic rules of social and conversational interaction.

It is highlighted in [

12] that the main goal of emotion recognition in conversation (ERC) systems is the correct identification the emotions in the speakers' utterances during the conversation. ERC helps to understand the emotions and intentions of users and develop engaging, interactive, and empathetic HCI systems. The input data for a multimodal ERC is information from different modalities for each utterance, such as audio-visual speech and facial expressions, and the model uses this information to make relevant predictions of emotions for the utterance. In [

13] it was found that in the case of audiovisual recognition of emotions in voice, speech (text), and facial expressions, the facial modality provides recognition of 55% of emotional content, the voice modality provides 38%, and the textual modality provides the remaining 7%. The last is the motivation to use audio-visual speech emotion recognition.

There are few studies on multimodal emotion recognition in children, and even fewer studies have been done for automatic children's audiovisual emotion recognition. Due to the small size of the available datasets, the main approach was to use traditional machine learning (ML) techniques. The authors of [

14] mentioned the following most popular ML-based classifiers: SVM, GMM, RF, KNN, and ANN, with the SVM classifier being employed in the majority of ML-based affective computing tasks. Recently, attention to research on automatic methods of emotion recognition in audiovisual speech has increased due to the development of new efficient ML and Deep Learning (DL) methods [

15], the availability of open access datasets of emotional audiovisual speech and high-performance computing resources [

16].

Motivated by these developments, in this study we have developed a neural network architecture for children’s audiovisual emotional recognition. We conducted extensive experiments with our architecture on our proprietary dataset of the children’s audiovisual speech.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

An extended description of the children’s audiovisual emotional dataset is provided.

An architecture of a neural network for children’s audiovisual emotion recognition is proposed.

Experiments on emotion recognition based on the proposed neural network architecture and the proprietary children’s audiovisual emotional dataset are given.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. We analyze the common datasets and algorithms for the multimodal children emotion recognition in

Section 2. In

Section 3, we present a description of the dataset we collected specifically for our purposes. We demonstrate the algorithms and the model we propose for solving the problem in Section 4. In Section 4, we describe the experiments with our data and algorithms, and in

Section 5 we present the results of the experiments. Lastly,

Section 6 summarizes the contributions of the article and formulates the directions of future research on multimodal children’s emotion recognition.

2. Related Work

Over the past decade, many Audio-Visual Emotion Recognition (AVER) systems for adults have been proposed in the literature. There are numerous publications and reviews on three traditional AVER issues: databases [

17], features, classifiers, and data fusion strategies [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The authors of [

22] covered all the major deep learning techniques used in AVER. The authors of [

15] investigated audiovisual deep learning approaches to emotion recognition for the in-the-wild problem, using end-to-end and transfer learning technique. The authors of [

23] introduced a high-performing deep neural network (DNN) based approach for AVER that fuses a distilled visual feature extractor network with a modified VGGish backbone and a model-level fusion architecture.

However, there are few articles on children’s emotion recognition using single speech or facial modalities, and even fewer on children’s audiovisual emotion recognition, which is due to the lack of available children’s audiovisual emotional datasets.

In this section, we summarize some of the most relevant recent research on AVER, focusing on children's audiovisual speech. In doing so, we pay special attention to children’s audiovisual speech emotion corpora and those approaches that use state-of-the-art machine learning and deep machine learning methods.

2.1. Children’s Audio-Visual Speech Emotion Corpora

Despite the difficulties in obtaining emotions data, there are corpora of children's emotional speech in different languages [

24,

25,

26,

27] and emotional facial expressions [

28] of children. Research is being conducted on the automatic recognition of emotions from children's speech [

29,

30] and their facial expressions [

31]. The accuracy of emotion recognition can be higher when using several modalities [

32], for example, audio and video, which requires the collection of appropriate audiovisual corpora.

A brief description of the available datasets of children's audiovisual emotion speech is presented in

Table 1 and in more detail below.

AusKidTalk (Australian children’s speech corpus) [

33] – audio and video recordings of game exercises for 750 children from 3 to 12 years old, equally distributed by age on the material of Australian English (AusE). The study participants were 700 children with typical development (TD) and 50 children with speech disorders – 25 children aged 6-12 years have a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). For each child there are records that made in a structured session 90-120 minutes. Speech is collected in various activities of children intended for reflections of the range of use in children's communication and various speech skill levels (e.g. restricted speech such as numerals through to informal speech). Video recording of the entire session is used to support manual annotation of children's speech.

AFEW-VA database [

34] of highly accurate per-frame annotations of valence and arousal for 600 challenging, real-world video clips extracted from feature films and frame-by-frame annotations of 68 facial images. More than 30,000 frames with per frame were annotated.

CHIMP (Little Children’s Interactive Multimedia Project) [

35] dataset collected by the Signal Analysis and Interpretation Laboratory at the University of Southern California in 2005. In the Little CHIMP experiments, 50 children of ages 4-6 each had a series of playing conversational interactions game. This dataset consists of children playing an interactive computer game by conversing with a Wizard-of-Oz controlled character.

EmoReact (Multimodal Dataset for Recognizing Emotional Responses in Children) [

36] - a multimodal spontaneous emotion dataset of 63 (31 males, 32 females) children ranging between 4 and 14 years old. It was collected by downloading videos of children who react to different subjects such as food, technology, YouTube videos, and gaming devices. The dataset contains 1102 audio-visual clips annotated for 17 different emotional categories: six basic emotions, neutral, valence and nine complex emotion. EmoReact dataset is the only dataset about children expressing emotions like verbally and visually [

37].

CHEA VD (Chinese Natural Emotional Audio–Visual Database) [

38] – a large-scale Chinese natural emotional audio–visual corpus with emotional segments extracted from films, TV plays and talk shows. The corpus contains 238 (125 males, 113 females) speakers from six age groups: child (<13), adolescent/mutation (13–16), youth (16–24), young (25–44), quinquagenarian (45–59), and elder (≥60). Over 141 h of spontaneous speech was recorded. In total, 26 non-prototypical emotional states, including the basic six, are labeled by four native speakers.

In [

32] the authors described a current project to create a human-independent, multimodal emotion detection system tailored for children with high-functioning autism (HFASD), with the ultimate goal of using it to develop emotion-sensitive interfaces designed for children with autism. The study involved 12 children aged 8 to 12 years. Recording is carried out in three sessions of 30 minutes each. The total time is 18 hours. Model for emotions detection involve four input modalities: video, audio, text and physiological signals (i.e. heart rate measure).

It should be noted that most of the described datasets are for English, some for Chinese and Irish languages. But no one is for Russian language.

2.2. Audio-Visual Emotion Recognition

Emotion recognition can be formulated as a problem where some source produces several streams of data (features) of various modalities (e.g. audio, video, etc.) each with its own distribution, and the goal is to estimate the distributions and map them onto the source. That, naturally, poses several questions that ought to be answered when building an emotion recognition system: which modalities are selected and represented, how the modalities are mapped on each other, and how the joint representations are mapped onto the sources of the distributions. We will review research that answers those questions and then propose our solution.

It has been shown, that regardless of the model and representations, multi-modal approaches virtually always outperform unimodal ones [

39], i.e. adding another modality can only benefit the performance. While this may sound obvious, in fact, the notion relies on the fact that in the worst-case scenario, a model is able to learn an identity mapping for the driving modality and disregard another. However, as has been shown in practice, it is rarely the case that additional modalities carry no valuable information. As for the selection of modalities, the most common ones in literature are images (or sequences of images, i.e. video), audio, and text. Since our research is focused on children, including pre-school children and children with developmental disorders, the contribution of textual modality, as already noted in the Introduction section, is insignificant. Therefore, we pick video and audio as our modalities of choice.

Representation is one of the key concepts in machine learning [

40]. While the task of machine learning imposes a number of limitations on the representations of data, such as smoothness, temporal and spatial coherence, over the years, a bevy of various representations have been used to solve various machine learning problems, and while some are more common than the other, there is no clear rule for choosing the best representation. Traditional machine learning algorithms rely on the representation of the input being a feature and learn a classifier on top of that [

41], meanwhile, the most agile modern models attempt to learn not only the representations, but also the architecture and the hyperparameters of the model [

42]. Both extremes, however, have several issues. The traditional approach lacks the capability to discover deep, latent features and mostly unable to achieve high efficiency associated with learning hierarchical and spatial-temporal relationships within feature sets, and since there is no space to learn cross-modal relationships, multi-modal models either rely on some sort of decision-level fusion or expert heuristics for joint representations. The end-to-end approach, on the other hand, has a high computational cost and requires a precise, structured approach to training [

43]. With those limitations, most of the modern models take reasonably preprocessed input data, then attempt to learn their efficient representations, including joint representations, and finally learn to classify those representations.

There are several ways to present audio data to a model, the most common include [

22]:

- -

waveform/raw audio, seldom used outside of end-to-end models, is simply raw data, meaning the model has to learn efficient representations from scratch;

- -

acoustic features such as energy, pitch, loudness, zero-crossing rate, etc., often utilized in traditional models, while allowing for simple and compact models, are mostly independent by design and prevent a model from learning additional latent features;

- -

a spectrogram or a mel-spectrogram, which shares some similar issues with raw audio, however, has found its way into many models due to extensive research into convolutional neural networks, since, being presented as an image, it allows to learn efficient representations as shown in various practical applications;

- -

Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs), which are coefficients that collectively make up a mel-frequency cepstrum—a representation of the short-term power spectrum of a sound—very commonly used as they provide a compact but informative representation.

In [

44], a relatively recent large-scale self-supervised pre-trained WavLM model for speech processing was proposed as an example of representation learning—a transformer encoder model that learns to efficiently encode audio features for classification, trained on a large dataset. The frozen encoder then can be utilized as a feature extractor for general purpose speech processing.

For image processing, the traditional approaches are extremely computationally expensive. For example, when a raw image is processed through a fully connected neural network, the network has to treat each pixel as an individual input and learn to extract relevant features from all locations within the image. In contrast, a convolutional neural network (CNN) [

45] can learn to recognize patterns in an image regardless of where they are located, using shared weights across the entire image and reducing the number of parameters required. By design, CNNs learn hierarchical representations of the raw input data and due to the shown efficiency of this approach, this is the most common approach for the representation of visual data. However, while a static image is a common input for a variety of computed vision problems, there is also a large field of problems concerned with sequences of images, i.e. video. Since for most of the practical tasks, there are strong relationships between consecutive frames of the input video, it is natural that efficient representations of those relationships are key for achieving high performance. For example, optical flow is a technique used in computer vision that allows one to recognize and track movement patterns in video footage [

46]. Another option is employing a recurrent neural network (RNN), for example, a long short-term memory (LSTM) network or a convolutional RNN, in which case a network is able to collect global context and produce representations enhanced with those shared latent features [

47]. Another relatively recent approach is to implement a 3D CNN [

48] where the temporal dimension is added to both the input tensor and the filters. While the idea of considering a sequence of images as just another dimension of the input tensor is relatively natural, the significant increase in the number of weights presents the need for a large amount of training video data and incurs a high computational cost. However, as the CNN architectures for image processing became highly optimized and somewhat larger video datasets have become available, this approach became legitimately viable.

The key concept for multimodal classification is the fusion of modalities. Though earlier models relied on unimodal classification and consecutive ensemble learning for decision-level fusion such as averaging, voting, weighted sum, etc., it was quickly discovered that both the redundancy of features between modalities and latent cross-modal relationships can be utilized to achieve higher performance [

18,

20]. Another traditional approach is to implement an early fusion. While some of the works propose the fusion of modalities at the input data level [

49], the most common approach is to combine modalities upon feature extraction, relying on some sort of heuristics [

18,

20]. In modern research, fusion is applied somewhere between the feature extraction and the decision level with the goal of learning efficient joint representations to both eliminate the redundancy in order to reduce the computational cost, and to align modalities to take advantage of cross-modal relationships.

There are several strategies for this kind of intermediate fusion, but the most common technique is to implement fusion via an attention mechanism [

16], a method to focus on the most relevant information from each modality, to determine which parts of each modality's input should be given greater focus when making a prediction, and selecting the most important features from each modality and combining them in a meaningful way. In a more general sense, the attention technique can be understood from the distinction between soft and hard attention. To emulate human perception and reduce computations, ideally, a model should be able to ignore the clutter in the input data and attend only to the meaningful parts [

50] sequentially and aggregate information over time—this approach would implement the so-called hard attention. However, to achieve that, it would require the model to make choices where to look at and they are difficult to represent as differentiable functions which would be required for the most conventional techniques for training. Requiring a model to be differentiable means that the model is simply able to associate more importance with certain parts of the input data—this approach is called soft attention.

Another informative way to designate attention techniques is to focus on the dimensions, across which they are applied. Though some terminology may be used interchangeably in the literature, more common one includes:

channel attention – as channels of feature maps are often considered feature detectors, it attempts to select more relevant features for the task [

51];

spatial attention – in the cases with multidimensional input data such as images, it attends to inter-spatial relationship of features [

52];

temporal attention – though the temporal dimension can sometimes be considered simply as another dimension of input data, in practice it might be beneficial to view it separately and apply different logic to it, depending on the task [

52];

cross-attention – mostly utilized in the cases with multiple modalities to learn relationships between modalities; since different modalities often have different dimensions, the modalities cannot be viewed as just another dimension of the input tensor, thus requiring a different approach from simply increasing the dimension of the attention maps; can be used to combine information from different modalities, in which case it is said to implement fusion of modalities [

53].

The authors of [

54] suggested that applying attention along the input dimensions separately achieves lower computational and parameter overhead comparing to computing attention maps with the same dimensions as the input. The authors of [

55] proposed the “Squeeze-and-Excitation” block, an architectural unit that explicitly models interdependencies between channels and recalibrates feature maps channel-wise. The authors of [

56] presented a self-attention mechanism for CNN to capture long-range interactions between features, which, in modern research, is mostly applied to sequence modeling and generative modeling tasks, they show that they can improve the performance of a model by concatenating convolutional feature maps with a set of feature maps produced via self-attention. The authors of [

57] implemented cross-attention for multimodal emotion recognition from audio and text modalities where the features from the audio encoder attend to the features from the text encoder and vice versa to highlight the most relevant features for emotion recognition. Though the features from those two modalities are eventually concatenated before passing them to the classifier, the attention block does not explicitly implement a fusion of modalities and is rather an example of late fusion. The authors of [

58] proposed a universal split-attention block for fusion of modalities where the attention block explicitly fuses features from different modalities and can be both placed at arbitrary stage of a network and repeated multiple times across the network.

After the feature maps are generated by a network, the final step is to classify the sample into one of the target categories. The most common approach is to map the feature maps onto scalar values (flatten the feature maps) and present the output as a scalar vector so that it can be presented to a fully connected network which is trained to classify the input into one of the target categories, usually by a SoftMax layer with the number of neurons equal to the number of classes [

41]. Even though this approach is utilized in most of the modern models, flattening of the feature maps effectively discards the spatial and temporal relationships. To investigate some of those issues, the authors of [

59] suggested to generate class activation maps using global average pooling where a class activation map for a particular category indicates the discriminative image regions used by the CNN to identify that category. Since the outcome of this procedure can encapsulate the spatial and temporal relationships between the input and the feature maps, this information can also be employed for classification. In this paper we demonstrate one such approach.

3. Corpus Description

To study children’s audio-visual emotion recognition, an audio-visual emotional corpus was collected. The corpus contains video files with emotional speech and facial expressions of Russian speaking children.

3.1. Place and Equipment for Audio-Visual Speech Recording

The recording was conducted in the laboratory room without special soundproofing (the noise level was determined only by the operation of the switched-on equipment). Children's speech was recorded using the Handheld Digital Audio Recorder PMD660 (Marantz Professional, in Music, Inc., Sagamihara, Japan) and the external microphone “SENNHEIZER e835S” (Sennheiser electronic GmbH & Co. KG, Beijing, China) with the following settings: the sampling rate was set to 48,000 Hz and the mono audio channel was used in all the recording sessions. In parallel with the recording of speech, the child's behavior and facial expressions were recorded using the video camera “SONY HDR-CX560” (SONY Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with maximum resolution 1920 x 1080 at 50 frames per second. The video camera was located at a distance of 1 meter from the child’s face. During testing, the child sat at the table opposite the experimenter. The light level was constant throughout the recording session. Speech files were stored in Windows PCM format WAV, 48,000 Hz, 16 bits per sample; video files are stored in AVI format.

3.2. Audio-Visual Speech Recording Procedure

Recording of speech and facial expressions of children was carried out when testing children according to the Child’s Emotional Development Method (CEDM) [

60]. The CEDM includes two blocks. Block 1 contains information about the child's development received from parents/legal representatives. Block 2 contains information about methods for children testing, including interview, psychological tests, play situations. Block 2 includes tests and tasks aimed at: 1) to extract the child's emotional state from the voice, speech, facial and behavior traits; 2) to discover the child's ability to recognize the emotional states of others. All children were tested by two Subject Matter Experts (SME) with professional experience more than 10 years working with children. One session lasted 1.0-1.5 hours. This time included conversations with parents, filling out questionnaires and testing children (40-60 minutes).

Participants of the study were 30 children aged 5-11 years.

The criteria for including children in the study were:

The consent of the parent/legal representative and the child to participate in the study.

Age of 5-11 years for the current study.

The absence of clinically pronounced mental health problems, according to the medical conclusion.

The absence of severe visual and hearing impairments in children according to the conclusions of specialists.

The experiment procedure includes a conversation with parents about the aim of the study, signing the Informed Consent. Filling out the questionnaires by parents - Questionnaires to identify the current state of the child: “Overall and emotional development of the child”.

The experimental study begun with a short conversation with the children in order to introduce the experimenter to the child. The child then completed the following tasks: playing with a standard set of toys, co-op play, “acting play” when the child is asked to show (depict) the emotions “joy, sadness, neutral (calm state) anger, fear”; should pronounce the speech material, manifesting the emotional state in voice; video tests – for emotions recognition, standard pictures containing certain plots.

All procedures were approved by the Health and Human Research Ethics Committee (HHS, IRB 00003875, St. Petersburg State University) and written informed consent was obtained from parents of the child participant.

3.3. Audio-Visual Speech Data Annotation

Specifically for training the neural network based on our approach with 3D CNN, we have prepared an annotated dataset that contains relatively short video segments with audio. First, we performed facial landmark detection across the whole video dataset and automatically selected the segments with continuous streams of video frames with fully visible faces (as per the data collection procedure, most of the frames with fully visible faces belong to a child being recorded). Further, we applied speaker diarization and selected the segments where the continuous streams of video frames with fully visible faces intersect with continuous speech. Next, we had a group of 3 experts review the obtained video segments to either annotate them with an expressed by a child emotion, reject a segment if the face of a speech belonged to a non-target person appearing in the recording (due to difficulties in working with children, sometimes a parent or a staff member may appear in a frame or speak out to guide or help a child during the recording process), or annotate the segment with additional timestamps if across the video segment a child expresses different emotions at different times. To streamline the process, we have developed a simple application to assist the experts with reviewing the segments in the context of the extended video recording, annotating them, and marking additional timestamps. Upon the completion of the annotation process, the annotations were used to filter the dataset and further split the video segments according to an expressed emotion where necessary. Finally, we randomly split the segments into 30 frames long subsegments which were then used for training the neural network.

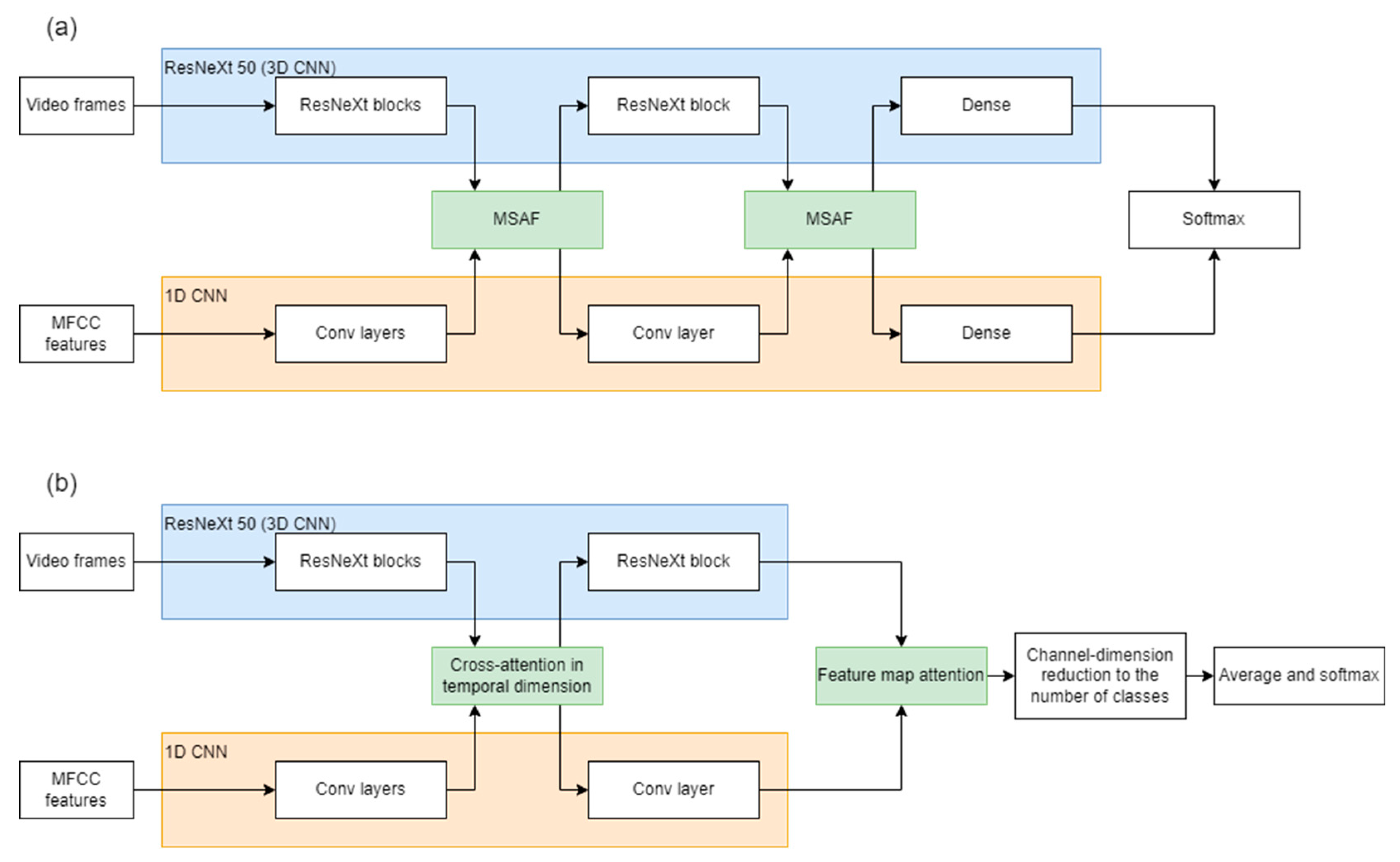

4. A Neural Network Architecture Description

For children emotion classification, we propose a neural network based a 3D CNN for video processing and a 1D CNN for audio processing. To demonstrate the performance of our solution, we took as the baseline the architecture from [

58], as that solution has shown a state-of-the-art performance for the target problem. Note, however, that in [

58] the authors propose a modality fusion block while utilizing existing approaches for video and audio processing to demonstrate the performance of their proposed solution for several machine learning problems, including emotion detection. Similarly, in this manuscript we do not discuss in details the underlying models and refer the reader to the original article [

58]. Our goal here is to demonstrate that by optimizing the attention component of the model to the particularities of the source data we can improve the performance of the emotion classification for children speech.

Per the research in children speech, some of which is reviewed in the introduction section, the temporal alignment between the visual and the audio modalities is highly informative for the detection of emotions in children speech. Also, it seems that the research indicates that this temporal alignment might be not only dependent on the psychophysiological aspects of children in general, but also may differ for typically and atypically developing children, and, moreover, for different types of atypical development. This, naturally, provides for an assumption that by increasing the focus and granularity of modeling the inter-modal temporal relationships may result in an improved performance of a model. For this problem, we propose a solution which is a modification of the cross-attention fusion module introduced in [

58], followed by an inspired by [

59] classifier based on applying “Squeeze-and-Excitation”-like attention [

55] to the feature maps of the final layer for a classification preserving more spatial relationships than a traditional approach with flattening the feature maps and attaching a fully-connected network.

For a comparison between the baseline and the suggested in this paper architectures, see

Figure 1.

Let us underscore a couple of differences between the proposed and the baseline models. First, in this article, we present a different implementation for the fusion block: here, we implement it in a window and with the query-key-value approach to calculating attention. Second, in the baseline model, the fusion block is placed at two locations but in our model, we find one block sufficient. However, it is important to highlight that neither we nor the authors of the baseline model require a specific placement of the fusion block: both consider the fusion block a black box or, in a sense, a layer that can be placed at arbitrary positions and an arbitrary number of times, depending on various circumstances such as a choice of the base models for video and audio processing. Third, in our work, we propose a different approach to classification: instead of the traditional flattening of the feature maps with a dense layer, we deploy an attention layer to transform feature maps into class maps where the number of the class maps equals to the number of the target classes.

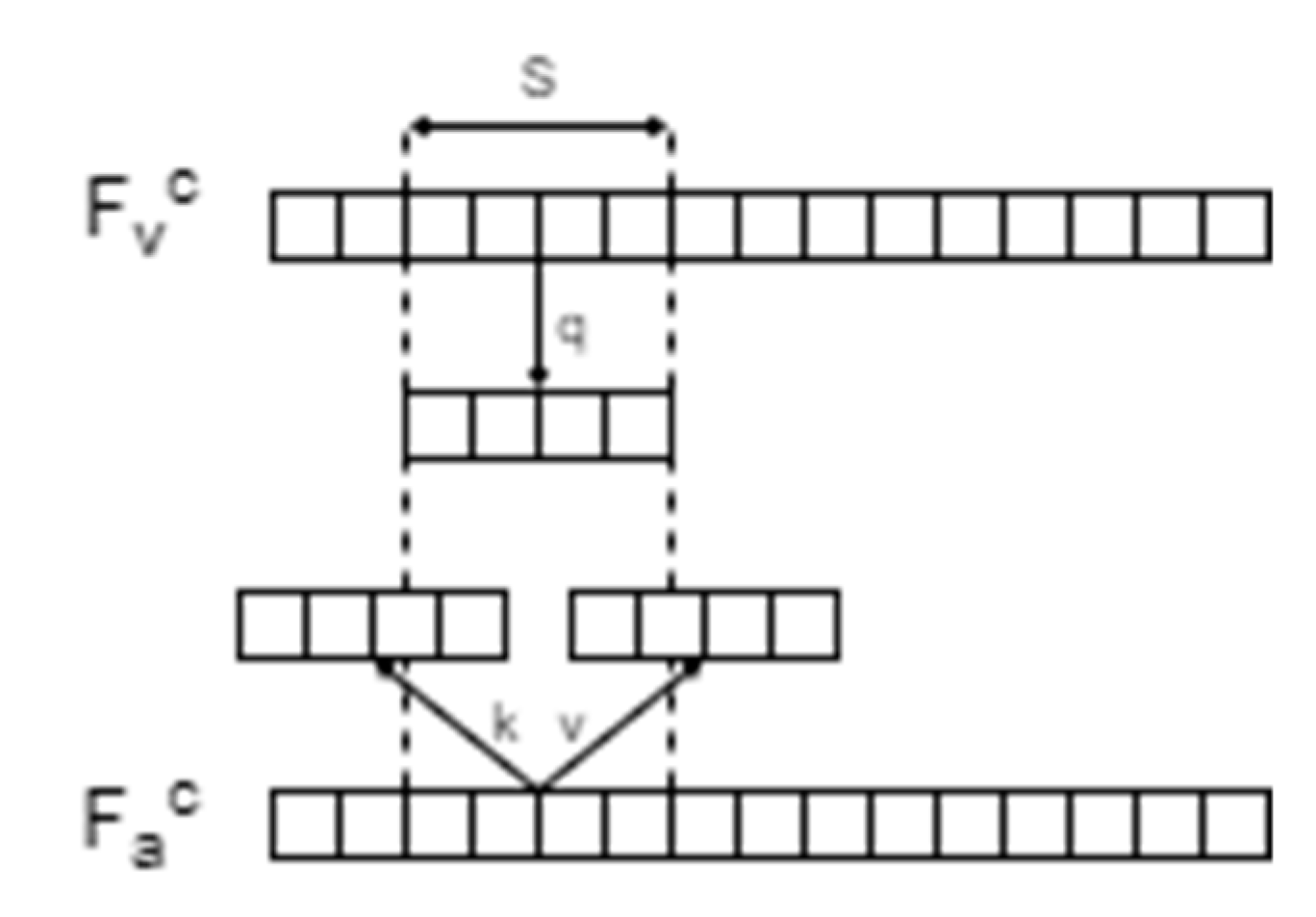

4.1. An Algorithm for Multimodal Attention Fusion

Following [

58], we do not assume a specific placement of the attention block in the architecture, essentially, we only consider the attention block in a context of a neural network architecture a black box with feature maps in—feature maps out. Briefly (for a more detailed explanation we direct the reader to [

58]), the cross-attention fusion module for video and audio modalities takes feature maps

, where

are feature maps for the video modality and Fa are feature maps for the audio modality and, as an input and produces modified feature maps

with the goal of enhancing the quality of representations of features of each modality by attending to them according to the information learned from another modality. As a sidenote, here we do not make an explicit distinction between the sets of feature maps and the blocks of sets of feature maps where the notion of blocks appears from the introduction of cardinality—an additional dimension to the data passing through a network—in the ResNeXt architecture since both our approach and the approach in [

58] are essentially agnostic to this distinction in the sense that both simply operate on vectors containing feature maps. To calculate the modified feature maps, first, each modality must be mapped to a space with only temporal dimension, which for our problem simply means the spatial dimensions of the video modality are collapsed to a scalar via global average pooling. After obtaining the channel descriptors, a commonly called global context descriptor has to be formed as the source of the information about cross-modal relationships. Here, we propose the following approach: to capture the more immediate relationships between the modalities, we calculate the query, key, and value [

61] in a window of length

for the context vectors

and

for video and audio modalities, respectively (see

Figure 2).

Since this approach initially appeared in the context of the natural language processing problems and is often explained in the terms of that field, here, we want to provide a brief intuition for applying this approach in more general terms. First, in the case of one modality, the goal is to find relationships between different sections of a feature map of that modality. For additional clarity, when we consider videos, i.e., a modality with both spatial and temporal dimensions, we can consider either the self-attention within a single image where sections are represented as regions of pixels in the image, and the self-attention within the temporal dimension obtained by, in one way or another, collapsing the spatial dimensions of a series of images; the “query, key, and value” approach is agnostic to whichever one we choose.

However, in this article, we are always talking about the attention in the temporal dimension. To achieve that, each section is mapped to three different vectors: “query” — functioning as a request, “value” — functioning as a response, and “key” — a map between queries and values. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that attribution of a function or role to those vectors serves mostly for the purposes of human understanding while from a purely technical standpoint, the procedure is implemented simply via a triplication of a fully-connected layer and then another layer joining the outputs together.

Let us call the learnable transformations for the query, key, and value (, and ) vectors , and , respectively. Then, for the context vectors and for video and audio modalities, and for their windowed segments and , we calculate , , and . While the dimensions of the value vectors are not required to match the dimensions of the query and key vectors, unless there is a specific reason to choose otherwise, most commonly the dimensions do match, for simplicity; here, we follow this approach, so . Strictly speaking, the key vectors do not provide a one-to-one mapping between queries and values, instead, they incapsulate the likelihood or the strength of the relationship between each query and each value. Also, since we consider each segment of each windowed context vector independent, we are only interested in the relative likelihood which we, following the common approach, implement via . So, for each query , we would calculate for each key for , or, in matrix form: .

The result, in some sense, is a heatmap, showing the strength of the relationships between queries and values. Now, at this point, we still have to construct a function that would take this heatmap and the values and produce a new set of feature maps and while, in principle, this function can also be learned, it had been shown that a simple weighted average provides for a good balance between the performance and the required computational resources since it, again, can be calculated as a straightforward matrix multiplication. Summarizing the algorithm, we can present the equation for joining the outputs (the attention) as:

where

is a simple scaler.

As for the learnable transformations for the query, key, and value for multiple modalities, in our case, we obtain them via projection of the windowed segments of the context vectors

and

for video and audio modalities, respectively, with learnable parameters

,

, and

:

After obtaining the attention maps (1), we can calculate the new feature maps:

Here, similar to how we do not make a distinction between feature maps and sets of feature maps, we also can view our suggested windowed attention as adding another dimension to the collection of feature maps which we can simply flatten when necessary, for example when passing them to a classifier.

4.2. An Algorithm for Feature-Map-Based Classification

As for the classifier, inspired by the concept of class activation maps in [

59], we propose the following intuition first: with

feature maps at the final layer, our goal is to obtain

feature maps each representing a category we are attempting to detect. To perform this transformation, we suggest to apply the “Squeeze-and-Excitation”-type attention [

55]

number times each with different learnable parameters with an assumption that this procedure would allow for learning the relationships between low-level feature descriptors, represented by the feature maps of the final layer, relevant to each target class separately. This way, after applying

to the globally average pooled class maps, we are expecting to obtain a probability distribution for the target classes.

Comparing to [

55], we omit the initial transformation step for the feature maps as we assume the feature maps at the final layer already represent low-level features and do not require additional transformations for spatial information. So, for each of the

class maps, we perform global average pooling, followed by the excitation operation (see [

55], section 3.2):

where

is a sigmoid function,

is ReLU,

are learnable parameters also implementing a bottleneck with a dimensionality reduction-expansion hyperparameter, and

is the vector further used to scale the channels of the feature volume

. The final output of the model is then:

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Software Implementation

To achieve higher efficiency in conducting the experiments, we created a software environment based on the Docker Engine (

www.docker.com). The aim of this framework was to simplify running the experiments of different machines, conducting ablation studies, and experimenting with base image and audio processing models. We employed the PyTorch (

https://pytorch.org) for implementing the components of our model and we followed the SOLID [

62] approach to software development to simplify reconfiguration of the model. Then, we created docker configuration scripts which would dynamically pull the necessary source code and downloadable resources such as base models, set up an execution environment and external libraries, and run the experiments. We ran the experiments on two machines with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 Ti GPUs.

4.2. Fine-tuning

Similar to [

58], we used the base models trained on the Ryerson Audio-Visual Database of Emotional Speech and Song (RAVDESS) [

63], and we further fine-tuned the models with samples from our dataset of children's emotional speech.

4.3. Performance Measures

For evaluation of the results of the experiments, we selected several common metrics, often used for similar tasks. First of all, we collected the multi-class recognition results into confusion matrices and extracted the true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) metrics.

Then, we calculated the accuracy, precision, and recall as

respectively.

Additionally, we calculated the F1-scores per class as

5. Experimental Results

From the corpus of child speech, we selected 205 recorded sessions and after processing them as described in 3.3 we obtained 721 video segments with variable length, annotated with an expressed emotion. Due to a relatively small volume of data, we randomly extracted 30-frame-length non-intersecting segments ensuring the balance between classes and repeated the process 6 times and averaged the results. For each batch, we performed a k-fold cross-validation with 80% of samples used to training and 20% for testing.

In addition, we conducted an ablation study where we tested the fusion block separately from the classifier.

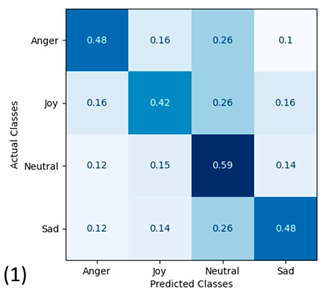

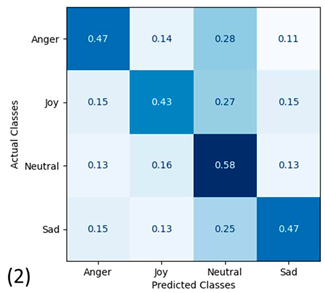

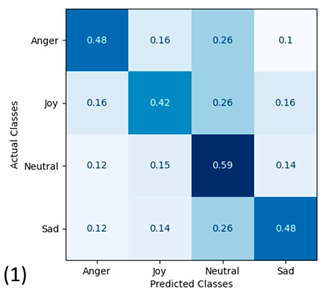

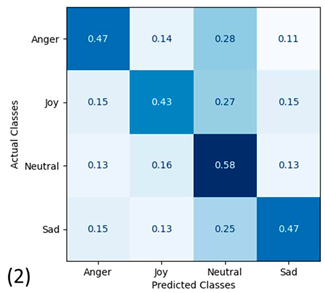

5.1. Results of Automatic Emotion Recognition on Extended Feature Set

Comparing to the results of the state-of-the-art (baseline) model at 0.482, our proposed approach

demonstrates a relative improvement in performance by about 2%.

Table 2.

Per-class scores in multi-class classification.

Table 2.

Per-class scores in multi-class classification.

| Per-class performance |

|---|

| Emotion |

Anger |

Joy |

Neutral |

Sad |

| Accuracy |

0.77 |

0.74 |

0.70 |

0.77 |

| Recall |

0.48 |

0.42 |

0.59 |

0.48 |

| Precision |

0.54 |

0.48 |

0.43 |

0.54 |

| F1-score |

0.51 |

0.45 |

0.50 |

0.51 |

Table 3.

Average scores in multi-class classifications.

Table 3.

Average scores in multi-class classifications.

| Classifier |

Overall Accuracy |

| Fusion block + classifier |

0.492 |

| Fusion block only |

0.487 |

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Experts in children speech observe that the relationships between the expressions of emotions in different modalities are distinct between children and adults. Relying on their experience and empirical knowledge, it appears, they can utilize it for a better recognition of a child’s emotions, manually analyzing the samples. This led us to propose a hypothesis that by focusing more on the temporal relationships between different modalities for multi-modal automatic emotion recognition in children we can achieve improvements in performance. Due to the complexity of the problem, in the modern scientific literature one can find a wide variety of approaches and models. To test our hypothesis, we selected several common and popular approaches that demonstrate state-of-the-art performance in similar tasks and took them as a baseline. It was important to isolate our solution as much as possible, making sure the differences in the performance mostly emerge from differences in the models related to our hypothesis rather than from unrelated differences. Unfortunately, in machine learning, even repeating the same experiment with the same model and data it is impossible to produce exactly the same results, however, we attempted our best to utilize the same base models and mostly the same training data, except for our novel corpus of children emotional speech.

As for the implementation of our solution, we focused on the parts of the model, responsible for the multi-modal fusion via attention. To help the model to focus more on the temporal relationships between different modalities, we proposed to window the context vectors of the modalities, calculate the attention with the query-key-value approach, and perform modality fusion utilizing the obtained attention maps. Additionally, since this approach focuses on the temporal dimension, we also introduced an approach to classification based on the concept of class activation maps that elevates the attention to the spatial dimensions. However, it is important to highlight, that our original hypothesis only related to the temporal dimension and, even though, eventually, we observed a cumulative improvement in performance, we did not explicitly test the hypothesis that this approach to classification is independently positive. Now that we observed the results, in future work, we plan to introduce this idea separately and evaluate the performance.

By evaluating the results of the experiments, we confirmed that with a significant degree of certainty, our solution can improve the performance of automatic recognition of emotional speech of children. In future research we plan to focus on collecting more data, particularly, for children with atypical development, and testing our solution on more varied data. Also, we want to develop more practical tools and applications for people working with children with typical and atypical development to stress-test our solution in real-time environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., Y.M. and E.L.; methodology, Y.M.; software, A.M.; validation, O.F., E.L. and Y.M.; formal analysis, O.F. and E.L.; investigation, A.M. and Y.M.; resources, O.F. A.N. and E.L.; data curation, O.F., A.N. and E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M., Y.M., O.F. and E.L.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, Y.M.; project administration, E.L.; funding acquisition, E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project 22-45-02007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Schuller, B.W. Speech Emotion Recognition: Two Decades in a Nutshell, Benchmarks, and Ongoing Trends. Commun. ACM 2018, 61, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.A.; Jones, E.; Babar, M.I.; Jan, T.; Zafar, M.H.; Alhussain, T. Speech Emotion Recognition Using Deep Learning Techniques: A Review. IEEE Access. 2019, 7, 117327–117345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyakso, E.; Ruban, N.; Frolova, O.; Gorodnyi, V.; Matveev, Yu. Approbation of a method for studying the reflection of emotional state in children's speech and pilot psychophysiological experimental data. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwujekwe, D. Using Deep Leaning-Based Framework for Child Speech Emotion Recognition. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7859&context=etd (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Guran, A.-M.; Cojocar, G.-S.; Diosan, L.-S. The Next Generation of Edutainment Applications for Young Children—A Proposal. Mathematics 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Parada-Cabaleiro, E.; Casali, D.; Cesarini, V. The Emotion Probe: On the Universality of Cross-Linguistic and Cross-Gender Speech Emotion Recognition via Machine Learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palo, H. K.; Mohanty, M. N.; Chandra, M. Speech Emotion Analysis of Different Age Groups Using Clustering Techniques. International Journal of Information Retrieval Research 2018, 8(1), 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamulevičius, G.; Korvel, G.; Yayak, A.B.; Treigys, P.; Bernatavičienė, J.; Kostek, B. A Study of Cross-Linguistic Speech Emotion Recognition Based on 2D Feature Spaces. Electronics 2020, 9(10), 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyakso, E.; Ruban, N.; Frolova, O.; Mekala, M.A. The children’s emotional speech recognition by adults: Cross-cultural study on Russian and Tamil language. PLoS ONE 2023, 18(2): e0272837. [CrossRef]

- Matveev, Y.; Matveev, A.; Frolova, O.; Lyakso, E. Automatic Recognition of the Psychoneurological State of Children: Autism Spectrum Disorders, Down Syndrome, Typical Development. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2021, 12997, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duville, M.M.; Alonso-Valerdi, L.M.; Ibarra-Zarate, D.I. Mexican Emotional Speech Database Based on Semantic, Frequency, Familiarity, Concreteness, and Cultural Shaping of Affective Prosody. Data 2021, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.H.; Huang, X.; Shen, X.D.; Liu, H. Improving multimodal fusion with Main Modal Transformer for emotion recognition in conversation. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 258, 109978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Ferris, S. R. Inference of attitudes from nonverbal communication in two channels. Journal of Consulting Psychology 1967, 31(3), 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Khan, H.A.; Khan, I.U.; Piran, J.; Lee, J.W. A Comprehensive Survey on Affective Computing; Challenges, Trends, Applications, and Future Directions. arXiv:2305.07665v1 [cs.AI] 8 May 2023. arXiv:2305.07665v1 [cs.AI] 8 May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dresvyanskiy, D.; Ryumina, E.; Kaya, H.; Markitantov, M.; Karpov, A.; Minker, W. End-to-End Modeling and Transfer Learning for Audiovisual Emotion Recognition in-the-Wild. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2022, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Tao, W.; Liotta, A.; Yang, D.; Li, X.; Gao, S.; Sun, Y.; Ge, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W. A systematic review on affective computing: emotion models, databases, and recent advances. Information Fusion 2022, 83–84, 19–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haamer, R. E.; Rusadze, E.; Lüsi, I.; Ahmed, T.; Escalera, S.; Anbarjafari, G. Review on Emotion Recognition Databases. Human-Robot Interaction - Theory and Application. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Lin, J., Wei, W. Survey on audiovisual emotion recognition: Databases, features, and data fusion strategies. APSIPA Transactions on Signal and Information Processing 2014, 3(1), E12. [CrossRef]

- Avots, E.; ·Sapiński, T.; ·Bachmann, M.; Kamińska, D. Audiovisual emotion recognition in wild. Machine Vision and Applications 2019, 30, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karani, R.; Desai, S. Review on Multimodal Fusion Techniques for Human Emotion Recognition. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2022, 13(10), 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poriaa, S.; Cambriac, E.; Bajpaib, R.; Hussain, A. A review of affective computing: From unimodal analysis to multimodal fusion. Information Fusion 2017, 37, 98–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaschian, B.J.; Sierra-Sosa, D.; Elmaghraby, A. Deep Learning Techniques for Speech Emotion Recognition, from Databases to Models. Sensors 2021, 21, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoneveld, L.; Othmani, A.; Abdelkawy, H. Leveraging recent advances in deep learning for audio-visual emotion recognition. Pattern Recognition Letters 2021, 146, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, C.S.; Ponnusamy, R. Recognising and classify Emotion from the speech of Autism Spectrum Disorder children for Tamil language using Support Vector Machine. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2014, 9, 25587–25602. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.F.; Tong, R.; Wee, D.; Lee, P.X.; Ma, B.; Li, H. SingaKids-Mandarin: Speech Corpus of Singaporean Children Speaking Mandarin Chinese. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH), San Francisco, CA, USA, 8-12 September 2016; pp. 1545–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, R.; Valles, D. A Speech Emotion Recognition Solution-based on Support Vector Machine for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder to Help Identify Human Emotions. In Proceedings of the Intermountain Engineering, Technology and Computing (IETC), Orem, UT, USA, 2-3 October 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Espinosa, H.; Martínez-Miranda, J.; Espinosa-Curiel, I.; Rodríguez-Jacobo, J.; Villaseñor-Pineda, L.; Avila-George, H. IESC-Child: An Interactive Emotional Children’s Speech Corpus. Comput. Speech Lang. 2020, 59, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, H.L.; Pine, D.S.; Nelson, E.; Leibenluft, E.; Ernst, M.; Towbin, K.E.; Angold, A. The NIMH Child Emotional Faces Picture Set (NIMH-ChEFS): a new set of children's facial emotion stimuli. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011, 20(3), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.; Ali Salah, A.; Karpov, A.; Frolova, O.; Grigorev, A.; Lyakso, E. Emotion, age, and gender classification in children’s speech by humans and machines. Comput. Speech Lang. 2017, 46, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveev, Y.; Matveev, A.; Frolova, O.; Lyakso, E.; Ruban, N. Automatic Speech Emotion Recognition of Younger School Age Children. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, M.; Dalvi, C.; Kaur, K.; Patil, S.; Gite, S.; Kamat, P.; Kotecha, K.; Abraham, A.; Gabralla, L.A. Kids’ Emotion Recognition Using Various Deep-Learning Models with Explainable AI. Sensors 2022, 22, 8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, A.; d’Aquin, M.; Zarrouk, M.; Hollowa, J. Person-Independent Multimodal Emotion Detection for Children with High-Functioning Autism. CEUR Workshop Proceedings. 2020, CEUR –WS.org/Vol-2760/paper3.pdf.

- Ahmed, B; Ballard, K.J.; Burnham, D.; Sirojan, T.; Mehmood, H.; Estival, D.; Baker, E.; Cox, F.; Arciuli, J.; Benders, T.; Demuth, K.; Kelly, B.; Diskin-Holdaway, C., Shahin, M., Sethu, V., Epps, J., Lee, C.B., Ambikairajah, E. AusKidTalk: An Auditory-Visual Corpus of 3- to 12-Year-Old Australian Children’s Speech. In Proceedings of the 22th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH), Brno, Czechia, 30 August - 3 September 2021; pp. 3680-3684. [CrossRef]

- AFEW-VA database for valence and arousal estimation in-the-wild. Image and Vision Computing 2017, 65, 23-36. [CrossRef]

- Black, M.; Chang, J.; Narayanan, S. An Empirical Analysis of User Uncertainty in Problem-Solving Child-Machine Interactions. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Child, Computer, and Interaction Chania (WOCCI), Crete, Greece, 23 October 2008; paper 01.

- Nojavanasghari, B.; Baltrušaitis, T.; Hughes, C.; Morency, L. EmoReact: A Multimodal Approach and Dataset for Recognizing Emotional Responses in Children. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (ICMI), Tokyo, Japan, 12–16 November 2016; pp. 137–144. [CrossRef]

- Filntisis, P.; Efthymiou, N.; Potamianos, G.; Maragos, P. An Audiovisual Child Emotion Recognition System for Child-Robot Interaction Applications. In Proceedings of the 29th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Dublin, Ireland, 23-27 August 2021; pp. 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, J.; Chao, L.; Bao, W.; Liu, Y. CHEAVD: A Chinese natural emotional audio–visual database. J. Ambient Intell Hum. Comput 2017, 8, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiara, Z.; Calabrese, B.; Cannataro, M. Emotion Mining: From Unimodal to Multimodal Approaches. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2021, 12339, 143–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Vincent, P. Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2013, 8, 1798–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkov, A. The Hundred-Page Machine Learning Book. 2019, 141 p.

- Egele, R.; Chang, T.; Sun, Y.; Vishwanath, V.; Balaprakash, P. Parallel Multi-Objective Hyperparameter Optimization with Uniform Normalization and Bounded Objectives. arXiv:2309.14936 [cs.LG], 2023. [CrossRef]

- Glasmachers, T. Limits of End-to-End Learning. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Machine Learning (ACML), 26 April 2017, pp. 17-32. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v77/glasmachers17a/glasmachers17a.pdf.

- Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Kanda, N.; Yoshioka, T.; Xiao, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, L.; Ren, S.; Qian, Y.; Qian, Y.; Zeng, M.; Yu, X.; Wei, F. WavLM: Large-Scale Self-Supervised Pre-Training for Full Stack Speech Processing. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2022, 16, 6–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeev, A.; Matveev, Y.; Matveev, A.; Pavlenko, D. Residual Learning for FC Kernels of Convolutional Network. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2019, 11728, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Dosovitskiy, A.; Ilg, E.; Häusser, P.; Hazırbaş, C.; Golkov, V.; van der Smagt, P.; Cremers, D.; Brox, T. FlowNet: Learning Optical Flow with Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 2015 pp. 2758-2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Pawar, V.; Pawar, Y.; Pisal, S. Video Content Classification using Deep Learning. arXiv:2111.13813 [cs.CV], 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Kataoka, H.; Satoh, Y. Can Spatiotemporal 3D CNNs Retrace the History of 2D CNNs and ImageNet? In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018 pp. 6546-6555. [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, F. J.; Roggen, D. Deep Convolutional and LSTM Recurrent Neural Networks for Multimodal Wearable Activity Recognition. Sensors 2016, 16(1): 115. [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V. , Nicolas Heess, N. In ; Alex Graves, A.; Koray Kavukcuoglu, K. Recurrent Models of Visual Attention. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Vol. 2, December; 2014; pp. 2204–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Hafiz, A.M.; Parah, S.A.; Bhat, R.U.A. Attention mechanisms and deep learning for machine vision: A survey of the state of the art. arXiv:2106.07550 [cs.CV], 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bertasius, G.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L. Is Space-Time Attention All You Need for Video Understanding? arXiv:2102.05095 [cs.CV], 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, F. Multi-Modality Cross Attention Network for Image and Sentence Matching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA; 2020; pp. 10938–10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-L.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Germany, 2018, Part VII, September 8–14; pp. 3–19. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Zoph, B.; Le, Q.; Vaswani, A.; Shlens, J. Attention Augmented Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, 2019, Korea (South); pp. 3285–3294. [CrossRef]

- N., Krishna D., and Ankita Patil. Multimodal Emotion Recognition Using Cross-Modal Attention and 1D Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 21th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH), Shanghai, China, 25–29 October 2020, pp. 4243–47. [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.; Hu, C.; Li, G.; Cao, D. MSAF: Multimodal Split Attention Fusion. arXiv, , 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/2012.07175. 26 June.

- Zhou, B.; Aditya Khosla, A.; Agata Lapedriza, A.; Aude Oliva, A.; Antonio Torralba, A. Learning Deep Features for Discriminative Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2016; pp. 2921–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyakso, E.; Frolova, O.; Kleshnev, E.; Ruban, N.; Mekala, A.M.; Arulalan, K.V. Approbation of the Child's Emotional Development Method (CEDM). Companion Publication of the 2022 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (ICMI) 2022, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L. ; N. Gomez, A.; Kaiser, L., Ed.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. https: //arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.C. Agile Software Development: Principles, Patterns, and Practices. Alan Apt Series. Pearson Education, 2003.

- Livingstone, S.; Russo, F. The ryerson audio-visual database of emotional speech and song (ravdess): A dynamic, multimodal set of facial and vocal expressions in north American English. PLOS ONE, 2018, 13(5):1–35.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).