I. Introduction

COVID-19 and cardiovascular diseases:

COVID-19 primarily affects the lungs, although it can cause cardiac ailments as well (1). The body's inflammatory response to COVID-19 is very high; inflammation is the leading cause of myocardial injury (2). The plaque buildup in the arteries is usually harmless but can inflate, causing blood thrombi, myocardial infarction (MI), and strokes. There are several potential causes of short-term or long-term heart tissue damage.

A lack of Oxygen. Inflammation and fluid accumulation in the lungs' air sacs brought on by the virus reduce the amount of Oxygen that may enter the bloodstream. When the heart needs to work harder to pump blood, it poses a risk, especially for patients with cardiac disease. Overuse can lead to heart failure (HF), and hypoxia can kill cells and destroy tissue in the heart and other organs.

Cardiac inflammation is known as myocarditis. Like other viruses, such as the flu, the coronavirus can infect the heart muscle directly and cause harm. Indirectly, the body's immunological reaction can cause injury and inflammation to the heart.

In addition to affecting the inner surfaces of veins and arteries, coronavirus infection can also cause inflammation of the blood vessels, damage to very small vessels, and the creation of blood thrombi, all of which can reduce blood flow to the heart and other organs. Endothelial cells, which line the blood vessels, are affected by the illness known as severe COVID-19.

A heart condition caused by stress is called cardiomyopathy (CM). CM is a condition of the heart muscle that affects the heart's capacity to pump blood adequately and can be caused by a viral infection. When the body is under stress from a viral infection, it produces a flood of chemicals called catecholamines, which can temporarily stop the heart. When the illness clears up, the heart no longer has something to worry about.

Long-term CV outcomes of patients infected with COVID-19 were examined in research encompassing more than 11 million people and published in February 2022 in the journal Nature Medicine (1). The risk of CV illness following COVID-19 infection persisted for at least a year after infection, suggesting that the virus's effects last longer than the typical incubation period of two weeks. After 30 days of infection, the risk of CV disorders such as stroke, cardiac disease, pericarditis, myocarditis, HF, and blood thrombi was higher in COVID-19-infected patients, regardless of whether they were hospitalized. Those with COVID-19 were 63% more likely to experience cardiac problems within a year of infection. 45 extra CV incidents were found for every 1,000 persons who tested positive. Some investigators have recently found damage mechanisms to the CV and cerebrovascular systems (2). The utilization of state-of-the-art single-cell R.N.A. sequencing has revealed the mechanism of COVID-19 invasion of myocardial tissue, indicating the prospect of utilizing modern cell and molecular biological research techniques in exploring the complicated involvement of COVID-19 in CVD and other comorbidities (3). Myocardial involvement detected by CV magnetic resonance (C.M.R.) in the setting of COVID-19 infection has been reported at a prevalence of 26% to 60% in individuals with a history of hospitalization (4-6).

The long-term CV manifestations of SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) infection remain unknown (3-7). Moreover, clinical factors associated with COVID19-associated pathophysiology and underlying cellular molecular biological mechanisms are poorly understood (2-6). Therefore, this study aims to provide an updated account of clinical, cellular and molecular factors in cardiovascular diseases associated with COVID-19. A thorough analysis of the latest published literature was carried out for this purpose.

II. Myocardial Injury and COVID-19:

Myocardial injury refers to damage or injury to the heart muscle. It can result from MI, surgery, trauma, viral infections, or drug toxicity. Myocardial injuries can range from mild to severe and have significant health implications. CV biomarkers are commonly used to diagnose myocardial injury. These biomarkers are troponin, creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), and myoglobin, released by damaged heart muscle cells (8). An acute atherosclerotic plaque rupture causes MI of type I (T1MI).

In contrast, type 2 (T2MI) MI results from myocardial oxygen demand and supply mismatches without an acute thrombotic event (9). T2MI was initially introduced as part of the universal definition of MI (U.D.M.I.). The term refers to individuals who manifest increased cardiac troponin (cTn) levels but are not associated with an ischemic etiology (9). A global task force of cardiology experts published The Fourth UDMI in 2018. It provides updated and standardized criteria to diagnose MI, defined as ischemia-induced myocardial cell death.

The Fourth Universal Definition of MI includes five types of MI (9,10):

Type 1 MI: Spontaneous MI resulting from a primary coronary event, such as plaque rupture or erosion, leading to prolonged ischemia.

Type 2 MI: MI resulting from an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand without a primary coronary event and occurring in severe anemia, hypotension, or tachyarrhythmias.

Type 3 MI: MI resulting from sudden cardiac death, with symptoms consistent with MI but without diagnostic E.C.G. changes or biomarker elevation.

Type 4a MI: MI associated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), where biomarker elevation occurs following PCI.

Type 4b MI: MI associated with stent thrombosis, where biomarker elevation occurs associated with angiographic evidence of stent thrombosis.

COVID-19 is a respiratory illness caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and has since spread rapidly worldwide, leading to a global pandemic. The most common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, cough, and shortness of breath, although many people with the virus may also experience fatigue, muscle aches, a sore throat, and a loss of taste or smell. COVID-19 may cause severe respiratory illness, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or other life-threatening complications (11,12).

A mild to severe infection may occur; most people with the virus will experience mild to moderate respiratory illness without requiring particular medical intervention. Some individuals, however, will develop serious conditions that necessitate medical attention, particularly those older and with underlying illnesses, such as CVD, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, or cancer. Anyone can get sick with COVID-19 and become seriously ill or die at any age (13,14,15). In some patients, the heart may be affected, which can occur in individuals with or without a prior CV diagnosis.

Myocardial injury is a common complication of COVID-19 and can lead to serious CV complications. In COVID-19, myocardial injury is not fully understood. Still, it is thought to be caused by direct viral invasion of the heart muscle and indirect effects such as cytokine release and hypoxia. SARS-CoV-2 invades cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a membrane protein that counterbalances the adverse effects of the renin–angiotensin– aldosterone system (R.A.A.S.) by converting angiotensin II (Ang II) to Ang-(1–7). It recognizes and binds to the ACE2 receptor via the spike (S) protein (16). The exact mechanism by which SARS-CoV-2 causes myocardial injury remains unclear, but cells expressing high ACE2 levels are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 invasion and subsequent organ injury, including cardiomyocytes (C.M.s) (17). According to clinical observations, increased myocardial biomarker levels unrelated to obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD), generally diagnosed as myocardial injury, occurred in 7.2–40.9% of patients with COVID-19 (18). Several studies have reported a high prevalence of myocardial injury in COVID-19 patients. In 2020, a study published in J.A.M.A. Cardiology found that nearly one-third of hospitalized COVID-19 patients had elevated troponin levels, suggesting myocardial injury (19). Figure 1 shows the Classification of Myocardial Injury in COVID-19 (20).

Evidence of myocardial injury, an elevated troponin level, is common among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, with putative causes including stress cardiomyopathy, hypoxic injury, ischemic injury, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (cytokine storm). A minority of patients with an elevated troponin level present with symptoms and signs suggestive of acute coronary syndrome (A.C.S.). Patients with CVD, HTN, obesity, and diabetes are at increased risk of a poor prognosis. In addition, patients with myocardial injury, irrespective of cause, have a poorer prognosis (21-26). The mortality rates of patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with and without CVD in comparison with patients with and without elevated troponin levels (hs-TNI) are shown in (Figure 2) (26). As a sensitive and specific marker of myocardial injury, cardiac troponin is commonly used to diagnose and treat ACS There is a higher risk of mortality and complications in patients with COVID-19 who have elevated cardiac troponin levels. Studies have shown COVID-19 is associated with myocardial injury and MI (9). As described earlier, SARS-CoV-2 infection depends on the ACE2 receptor, widely distributed in various tissues and expressed at different levels in different organs (27,28).

Figure 1.

illustrates the potential mechanisms that can lead to myocardial injury in COVID-19. In general, for any patient with cTn increases >99th percentile, elevations should be broadly classified as 1) chronic myocardial injury, 2) acute nonischemic myocardial injury, or 3) acute myocardial infarction (MI) (20).

Figure 1.

illustrates the potential mechanisms that can lead to myocardial injury in COVID-19. In general, for any patient with cTn increases >99th percentile, elevations should be broadly classified as 1) chronic myocardial injury, 2) acute nonischemic myocardial injury, or 3) acute myocardial infarction (MI) (20).

Figure 2.

Illustrates the mortality of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with and without cardiovascular disease (CVD) in comparison to those with and without elevated troponin (hs-TNI) (26).

Figure 2.

Illustrates the mortality of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with and without cardiovascular disease (CVD) in comparison to those with and without elevated troponin (hs-TNI) (26).

III. Mechanism of Myocardial Injury and COVID-19:

A. Cytokine Storm

Several studies have reported that COVID-19 patients with severe illness have significantly higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin IL-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), compared to patients with mild illness, suggesting the involvement of cytokine storm in COVID-19- induced myocardial injury. A study conducted in Wuhan, China, found that elevated levels of IL-6, C-reactive protein (C.R.P.), and D-dimer were associated with adverse cardiovascular events, including myocardial injury (29).

Cytokine storm can induce endothelial dysfunction and increase vascular permeability, leading to capillary dilation, microvascular leakage, and micro-thrombi formation, resulting in myocardial injury. A recent study reported that COVID-19-induced cytokine storm upregulates the expression of ACE2 in the heart, providing an opportunity for ACE2-dependent myocardial infection (29).

The excessive inflammatory response, also known as cytokine storm, can cause collateral damage to different organs and tissues, including the heart, leading to endothelial dysfunction, increased vascular permeability, and myocardial injury. Furthermore, the cytokine storm may disrupt the myocardium's balance between oxidative stress and antioxidant defense, causing oxidative damage to cardiac tissues (30).

B. Oxygen supply-demand mismatch.

A study investigated the host susceptibility to severe COVID-19 and the establishment of a host risk score. The authors found that oxygen supply-demand mismatch due to respiratory failure was a common mechanism underlying severe COVID-19 and was associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes. The study highlights the importance of monitoring and managing oxygenation in patients with COVID-19 to prevent complications such as severe disease and mortality (31).

It was suggested that COVID-19 could cause Oxygen supply-demand mismatch, leading to myocardial injury through various mechanisms, including direct invasion of the virus, respiratory damage causing hypoxia, cytokine storm, and acute plaque rupture.

A direct invasion of the virus can cause damage to the heart tissue, leading to myocardial injury. Respiratory damage caused by COVID-19 can lead to hypoxia, which increases the oxygen demand of the myocardium and can cause an oxygen supply-demand mismatch, leading to myocardial injury.

The cytokine storm caused by COVID-19 can also lead to myocardial injury through various mechanisms, including oxidative stress and inflammation. Acute plaque rupture can also cause an oxygen supply-demand mismatch, leading to myocardial injury (31).

Several studies have reported myocardial injury in COVID-19 patients. One study observed elevated cardiac troponin levels in 36.1% of COVID-19 patients, associated with a higher mortality risk. In another study, myocardial injury, as defined by elevated cardiac troponin levels, was reported in 19.7% of COVID-19 patients, and these patients were more likely to require mechanical ventilation and have a poor prognosis (30).

C. Stress cardiomyopathy

Stress cardiomyopathy, also known as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, is a reversible left ventricular (LV) dysfunction characterized by transient wall motion abnormalities in the absence of significant obstructive CAD. Stress cardiomyopathy has been reported in patients infected with COVID-19, and it has been suggested that this may represent a significant complication of the disease.

The exact pathophysiology of stress cardiomyopathy in patients infected with COVID-19 has yet to be fully understood. However, it has been hypothesized that COVID-19 infection can cause an oxygen supply and demand mismatch, resulting in myocardial injury and stress cardiomyopathy. COVID-19 infection can lead to hypoxemia, causing a decrease in oxygen delivery to the myocardium. The resultant oxygen supply and demand mismatch can lead to myocardial injury, which may manifest as stress cardiomyopathy (32)(33).

Several studies have reported cases of stress cardiomyopathy in patients infected with COVID-19. In a study of 100 patients with COVID-19, stress cardiomyopathy was identified in five patients, suggesting a prevalence of 5%. Another study reported a prevalence of 7.8% of stress cardiomyopathy in COVID-19 patients with severe disease (32). Moreover, several reports suggest that COVID-19 infection can cause stress cardiomyopathy, characterized by left ventricular dysfunction and acute myocardial infarction clinical symptoms. The exact mechanism by which COVID-19 infection causes stress cardiomyopathy is unclear, but a few proposed hypotheses include catecholamine surge, direct myocardial injury, and microvascular dysfunction.

In a study of 416 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 7.2% were diagnosed with stress cardiomyopathy. Patients with stress cardiomyopathy had a higher incidence of in-hospital mortality and mechanical ventilation than those without the condition (34). Although stress cardiomyopathy is reversible, it can cause significant morbidity and mortality in some patients. Therefore, it is essential to recognize the potential association between COVID-19 infection and stress cardiomyopathy.

D. Hypoxic injury

Several studies have reported elevated levels of inflammatory markers, such as interleukin-6 (IL 6), in COVID-19 patients, which suggests an underlying inflammatory process. It has been proposed that systemic inflammation may contribute to myocardial injury by releasing inflammatory mediators. These mediators, such as IL-6, can cause endothelial dysfunction and microvascular thrombosis, decreasing oxygen supply to the myocardium (34).

In a study of 416 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, elevated levels of IL-6 were observed in those with myocardial injury compared to those without. The study concluded that inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, may contribute to myocardial injury in COVID-19 patients (19). Moreover, other inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (C.R.P.) and ferritin, have also been found to be elevated in COVID-19 patients with myocardial injury, indicating a possible role of systemic inflammation in the development of myocardial injury in COVID-19 (29). In another study, patients with severe COVID-19 were found to have elevated levels of troponin, a biomarker of myocardial injury, which correlated with the levels of inflammatory markers such as IL-6 and C.R.P. (19).

The exact mechanism of inflammatory mediator-induced hypoxic injury in COVID-19 patients is not yet fully understood, but systemic inflammation plays a significant role. Identifying and managing inflammatory mediators may help improve the prognosis of COVID-19 patients with myocardial injury.

E. Endothelial Dysfunction

Endothelial dysfunction and its associated effect on microvascular and epicardial vessels can contribute to many pathological conditions, such as inflammation and thrombosis. In COVID-19 patients, endothelial damage in the vascular wall can lead to a pro-thrombotic environment and micro-thrombi formation, contributing to myocardial injury (35).

Recent studies have shown that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can infect endothelial cells, leading to endothelial dysfunction (E.D.), capillary dilation, and increased vascular permeability. The virus can also induce an inflammatory response, increasing cytokine levels, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), leading to endothelial dysfunction (35).

A study on inflammatory markers and endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19 patients showed that elevated levels of IL-6, C.R.P., and D-dimer were associated with increased inflammatory activity and endothelial dysfunction, indicating a correlation between COVID-19 severity and endothelial injury. Another study found that damage to epicardial vessels due to endothelial dysfunction could lead to cardiac remodeling and subsequent myocardial injury (36). In addition, a survey on COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) found a significant correlation between pulmonary dysfunction and myocardial injury, indicating a possible involvement of microvascular dysfunction in COVID-19-induced myocardial injury (37).

It is essential to understand the impact of COVID-19 on endothelial dysfunction and its relationship with myocardial injury to develop effective preventive and therapeutic methods. Early detection of endothelial dysfunction could help prevent the progression of myocardial injury in COVID-19 patients. Further studies are needed to demonstrate the specific myocardial injury mechanism (Figure 3) (16).

Figure 3.

Illustration of the mechanism of myocardial injury (16).

Figure 3.

Illustration of the mechanism of myocardial injury (16).

IV. Clinical Manifestations Of Myocardial Injury:

A. Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of myocardial infarction (MI) include chest pain that radiates from the left arm to the neck, shortness of breath, diaphoresis, gastrointestinal symptoms (such as nausea and vomiting), an abnormal heart rate, anxiety, fatigue, weakness, stress, and depression (37). It has been reported that there will be low blood pressure, an elevated heart rate, a high respiratory rate, signs of low cardiac output, and a third heart sound when examining patients with myocardial infarction (38).

MI can be classified by typical symptoms in patients with chest, arm, or jaw pain in the form of dull, heavy, tight, pressure, ache, squeezing, crushing, or gripping in nature. Also, it can be classified as atypical symptoms in patients with epigastric back pain if it is present as burning, stabbing, or indigestion-like. However, it has been reported that radiation of the pain (to the right arm, left arm, neck, jaw, and back) and associated features (nausea, vomiting, sweating, dyspnea, and palpitations) are part of the clinical manifestations (39).

Some symptoms of myocardial ischemia include various combinations of chest, arm, jaw, or epigastric discomfort that occur during rest or exertion. The discomfort associated with acute myocardial infarction usually lasts at least 20 minutes. Usually, this discomfort is diffuse, not in a specific location, not positional, and not aggravated by movement, and it may be associated with dyspnea, excessive sweating, nausea, or syncope. These symptoms are not diagnostic for myocardial ischemia and can be misdiagnosed and thus attributed to gastrointestinal, neurological, pulmonary, or musculoskeletal disorders. MI may present with atypical or even without symptoms (8).

Diagnosing myocardial injury might be challenging if associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), especially in patients with advanced disease. Patients with myocardial injury associated with COVID-19 usually present with an atypical clinical presentation, so it is hard to diagnose. Myocardial injury can present in patients with no previous CVD history, even if the patient is not complaining of chest pain (40).

B. Investigations:

Cardiac biomarkers, ECG, echocardiography, and CMR are valuable noninvasive investigations for assessing CV involvement and complications in COVID-19 patients (41). Precautions should be taken to minimize the risk of contagion during these procedures.

Cardiac biomarkers like troponin, C.R.P., D-dimer, and NT-pro BNP are important for diagnosing and predicting the prognosis of COVID-19. Elevated biomarkers indicate a poor prognosis and increased risk of CV complications (42). COVID-19-related CVD can be categorized as primary, caused by direct viral injury, or secondary, resulting from an exaggerated inflammatory response (43).

Electrocardiogram (E.C.G.) changes, including arrhythmias, conduction defects, and S.T. segment and T-wave abnormalities, are common in COVID-19 patients (44-46). These changes can resemble those seen in acute myocardial infarction (A.M.I.) and myocarditis, making diagnosis challenging (47-50). Cardiac arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation, are more prevalent in critically ill COVID-19 patients (51).

Echocardiography is recommended for assessing cardiac structure and function in COVID-19 patients (52). However, precautions should be taken to minimize the risk of contamination (53, 54). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and stress echocardiography are preferred, while transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) carries a higher contamination risk (54, 55). Bedside echocardiography can help diagnose myocarditis in suspected COVID-19 cases (56).

Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) is the gold standard for evaluating myocardial structure and function (57). Portable C.M.R. devices are recommended for convenience and easier cleaning in COVID-19 settings.

A coronary angiogram is valuable for detecting and assessing CAD, identifying structural anomalies, and measuring hemodynamic parameters (58). COVID-19-associated coagulopathy has revealed the presence of intracoronary thrombus (I.C.T.) in individuals undergoing angiograms for acute coronary syndromes, as coagulation problems are common in COVID-19 affecting venous and arterial Circulation (59, 60). Liori et al. reported a case of a 39-year-old male with COVID-19 presenting with acute retrosternal chest pain and S.T. segment elevation in leads V4-V6 on the E.C.G. Thrombus aspiration restored flow in the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) as confirmed by coronary angiography (60).

Piccolo and Esposito emphasized the higher mortality risk in patients with concomitant coronary artery disease and COVID-19, suggesting avoiding invasive angiography with revascularization (61). Xie et al. found that invasive coronary angiography (I.C.A.) in stable CAD patients was associated with a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, and severe procedure-related complications compared to computed tomography coronary angiography (C.T.C.A.) (62).

COVID-19 and myocardial infarction patients may require a prolonged hospital stay and multiple anticoagulants for severe symptoms (63). Increased availability of C.T.C.A. was associated with a significantly shorter length of stay for patients with chest pain without increased adverse outcomes (64). Panjer et al. demonstrated good diagnostic accuracy of dynamic cadmium-zinc-telluride single-photon emission tomography (CZT-SPECT) in coronary artery disease (65).

V. Cardiac Complications of COVID-19:

A. Myocarditis:

Myocarditis is one of the cardiac outcomes in patients infected with SARSCoV-2 infection and its associated systemic inflammation. Similar to viral infections like COVID-19 with or without myocarditis, patients with myocarditis frequently present with chest discomfort, exhaustion, and dyspnea; however, some patients also report symptoms, including myalgia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and headaches (66). The prevalence of myocarditis among COVID-19 patients is unknown, partly because early studies frequently lacked proper diagnostic tools to detect myocarditis. Some claimed myocarditis may have been a factor in up to 7% of COVID-19-related fatalities (67).

B. Arrhythmia:

Cardiac arrhythmias were recognized as one of the potential complications in COVID-19 patients. Arrhythmia was observed to occur in 7.3% of the 137 patients in one observational study on the clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients in Hubei, China (68). In addition, Wang et al. noted that 44.4% of COVID-19 patients transferred to an intensive care unit had an arrhythmia (21). After acute COVID-19 infection recovery, researchers have reported a rise in arrhythmic problems, and the long-term frequency is still under study. According to recent studies, atrial arrhythmias and bradyarrhythmia, in particular, had an incidence of 13% and 12.8%, respectively, in the acute setting of COVID-19. Furthermore, ventricular arrhythmia, the less common variant, was recorded in 5.9% of patients, whereas the prevalence of atrioventricular block was 8.6% (69, 70). There are a few pathophysiological mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias: 1- direct injury to cardiomyocytes altering the electrical conduction; 2- infection of the pericardium causing massive edema; 3- ischemia from microvascular disease; 4- re-entrant arrhythmias due to myocardial fibrosis or scars; and 5- proinflammatory cytokines predisposing to arrhythmogenicity (71, 72).

C. Hypotension:

Hypotension following COVID-19 is a serious complication, even if it may occur in fewer hypertensive individuals. It is crucial because frail elderly patients with hypertension have a greater mortality risk and are more likely to develop cognitive fragility (73). Hypotension Induces cerebral hypoperfusion, ischemia, and hypoxia, and as a result, it can hasten the neurodegenerative processes that accelerate the manifestations of dementia and cognitive impairment (74). A recent case report was done by Koudelka M. et al. for five elderly patients known to be hypertensive and on medications (73). All patients included in the study have similar essential clinical characteristics; their age range was 65–85 years, and two of five were men. Following the COVID-19 infection, their B.P. was checked in the office, and all patients had well-controlled blood pressure. However, the patients were monitored by A.B.P.M. at home, where they detected multiple episodes of hypotension. (Figure 4) shows the A.B.P.M. home readings for one of the subjects in the study before and after COVID-19 infection, indicating the need for medication adjustments (73). All five patients showed the same pattern of this phenomenon. Regardless of factors that could contribute to lowering blood pressure, it is crucial to keep monitoring the patient, not only with office measurements. Since it is still unknown how B.P. readings change in these people, further studies and research will answer these questions.

Figure 4.

blood pressure (B.P.) values of Patient No.2 before and after COVID-19 (73).

Figure 4.

blood pressure (B.P.) values of Patient No.2 before and after COVID-19 (73).

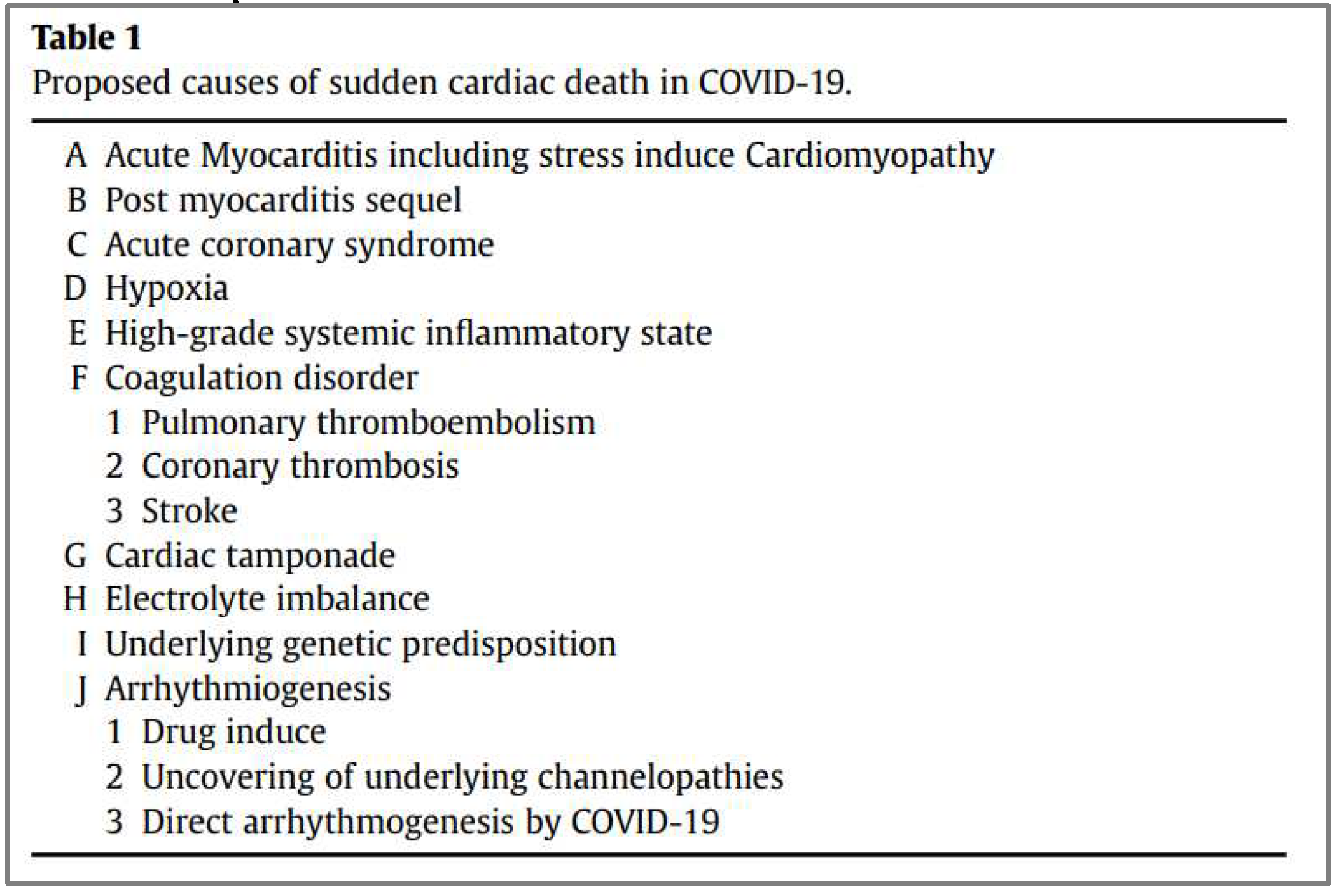

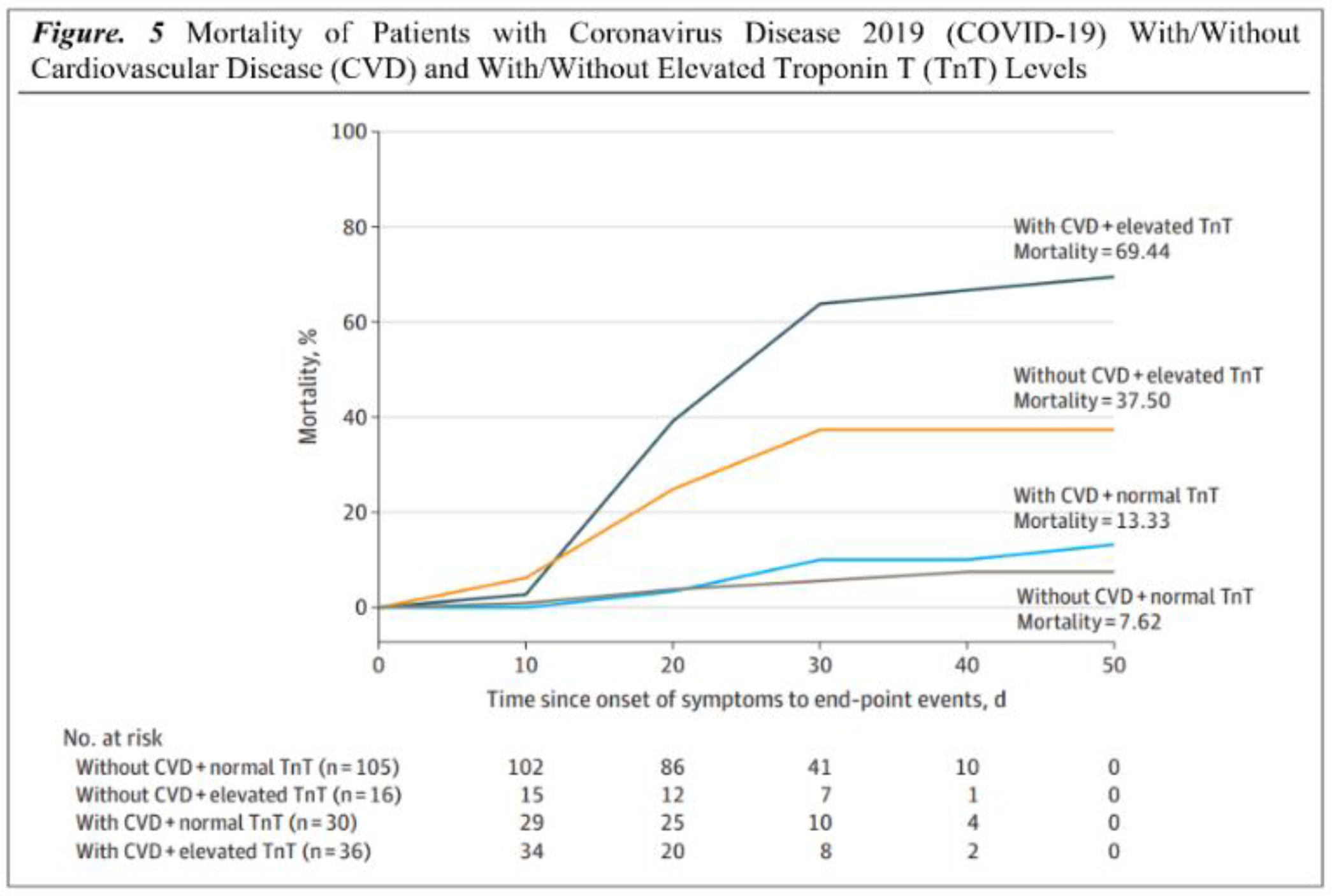

C. Sudden cardiac death:

3With COVID-19 infection, sudden cardiac death (S.C.D.) has been one of the worrying concerns (75, 76). The available data reveals a probable connection despite lacking evidence for a direct causal link between cardiac death and COVID-19. Both community and hospital settings have shown increased S.C.D. incidence (77). The mechanism of S.C.D. may involve many factors (Table 1). The most prevalent mechanism involved still needs to be determined due to a lack of evidence. A study conducted by Yang C et al. l reveals 187 patients, 37.50% (6 of 16) had elevated TnT levels without underlying CVD, 69.44% (25 of 36) had elevated TnT levels with underlying CVD, and 7.62% (8 of 105) had normal TnT levels without underlying CVD died in the hospital; This summarizes that patients with the highest mortality (69.44%) and shortest survival times were those with underlying CVD and an increase in TnT levels (Figure 5) (78).

Table 1.

A list of presumed causes of sudden cardiac death in COVID-19 (77).

Table 1.

A list of presumed causes of sudden cardiac death in COVID-19 (77).

Figure 5.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mortality rates with/without cardiovascular disease and with/without elevated Troponin T levels (78).

Figure 5.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mortality rates with/without cardiovascular disease and with/without elevated Troponin T levels (78).

VI. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19:

Numerous investigations revealed that COVID-19 survivors had a significant risk of cardiovascular disease and ongoing symptoms. According to a report by Al-Aly Z from June 2021, the cardiovascular system's pulmonary and extrapulmonary organs are all impacted by SARS-CoV-2 post-acute sequelae (79).

Nearly a third of hospitalized patients following acute COVID-19 were readmitted, and more than one in ten passed away after discharge (80). COVID-19 patients had substantially higher rates of respiratory illness, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD), with 770 diagnoses per 1000 person-years. Those under 70 and members of ethnic minorities were more likely to see increased risk.

Additionally, a study conducted by Huang C et al. enrolled 1733 COVID-19 patients; the study discovered that the primary issues faced by COVID-19 survivors included exhaustion or weakness of the muscles, trouble sleeping, and anxiety or sadness. Abnormal chest imaging symptoms and more severely reduced pulmonary diffusion capabilities were observed in patients who were more critically unwell throughout their hospital stay (81). Furthermore, 143 individuals were examined for COVID-19 symptoms by Carfì A et al.; just 18 patients had no COVID-19-related symptoms. 44.1% of patients had a worse quality of life, and many reported joint discomfort, chest pain, fatigue, and dyspnoea (82).

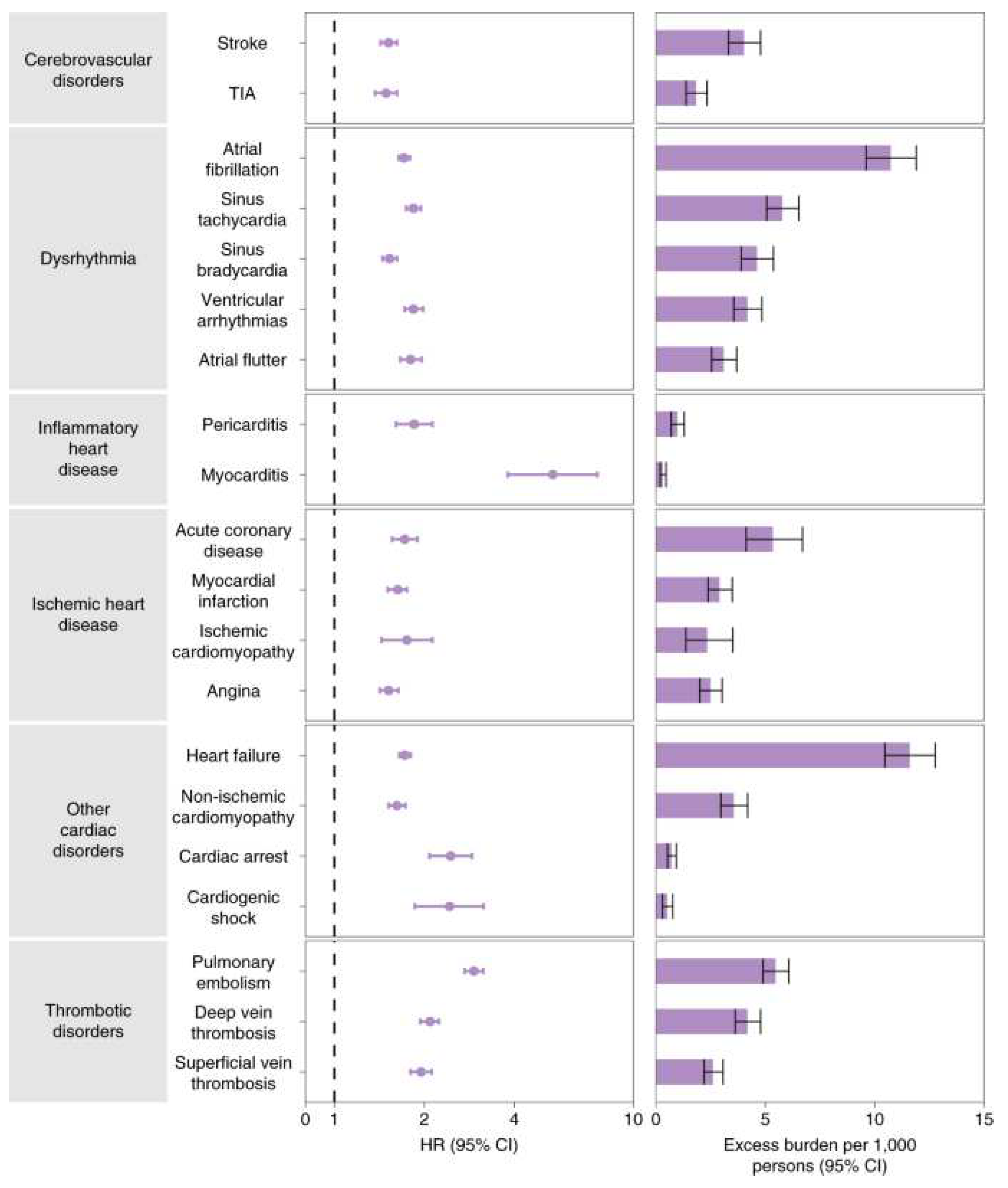

According to a study conducted in May 2021 by Daugherty SE, 14% of adults 65 and older had at least one new clinical sequela following the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which required medical attention. This was 4.95% higher than the comparison group from 2020 (83). The conditions included chronic respiratory failure, cardiac arrhythmia, hypercoagulability, encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, amnesia, diabetes, abnormal liver test results, myocarditis, anxiety, and fatigue. On the other hand, according to a study that included 5,859,411 VHA users who were not infected with COVID-19 and 153,760 US veterans, those who had the virus had higher incidence burdens and risk factors over 12 months as shown in Figure 6 (84).

The sympathetic nervous system can be overstimulated by COVID-19, which can also cause a cytokine storm, hypercoagulopathy, and inflammation. Even after recovering from COVID-19, these pathways may cause permanent harm to the cardiovascular or respiratory systems. Cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease among COVID-19 survivors is anticipated to rise due to these permanent consequences, such as congestive heart failure or diminished lung function.

The National Healthcare Databases (V.H.A.) of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (V.H.A.) provide evidence that hospitalized and non-hospitalized survivors of acute COVID-19 have a high risk of CVD and a high 1-year disease burden. Based on data from 48 healthcare organizations (HCOs) in the U.S. Collaborative Network (84).

Figure 6.

Risks and 12-month burdens of incident post-acute COVID-19 cardiovascular outcomes compared with the contemporary control cohort (84).

Figure 6.

Risks and 12-month burdens of incident post-acute COVID-19 cardiovascular outcomes compared with the contemporary control cohort (84).

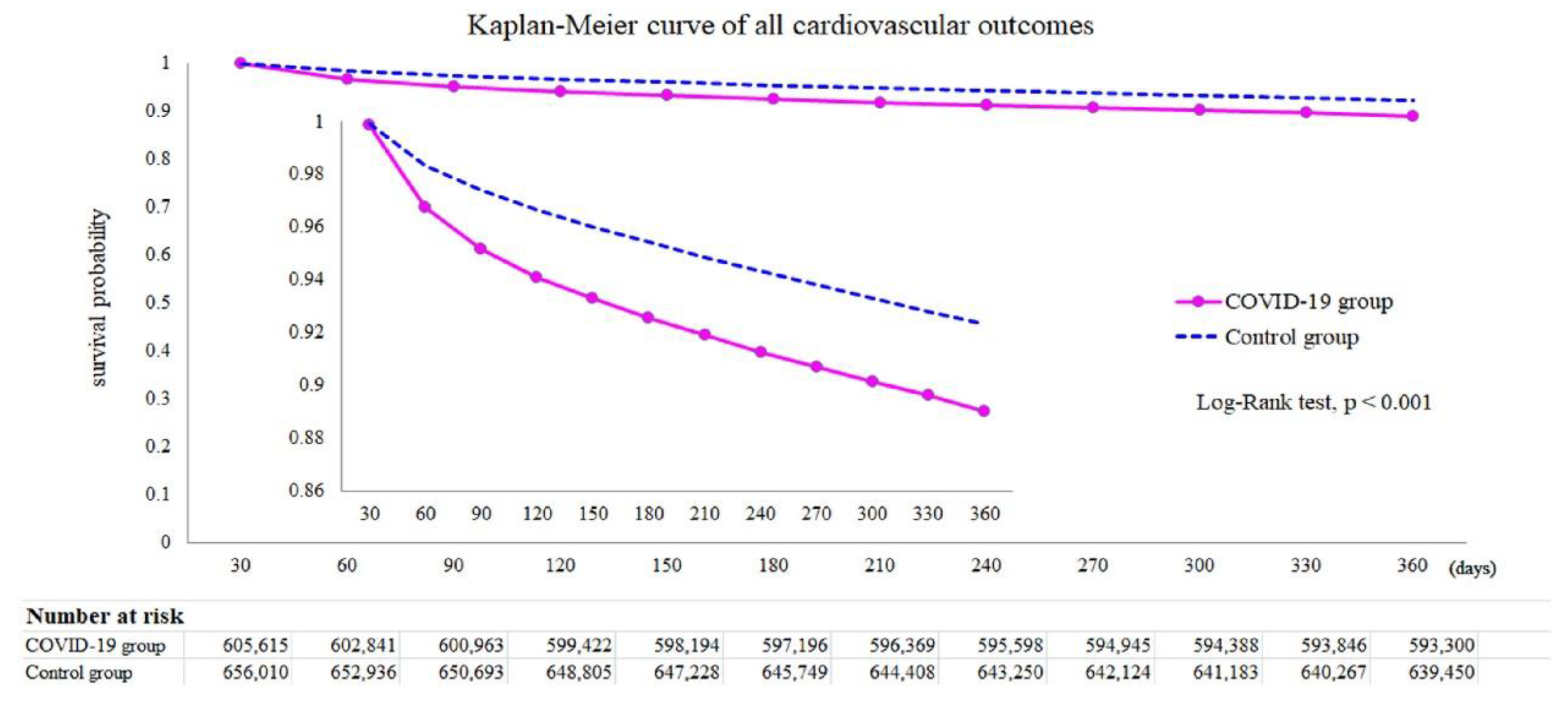

After all, it was found that dysrhythmias, pericardial or inflammatory heart disease, and cerebrovascular disorders were among the CVD cases more common in COVID-19 than in current controls. Furthermore, based on the Kaplan-Meier curve in

Figure 7, the mortality rate in the COVID-19 group was higher than in the control group. Among individuals not hospitalized during the acute phase, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation and flutter, tachycardia, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, and thromboembolic disorders present significant risks and limits, with a graded increase across the severity range

(85).

Figure 7.

Cardiovascular outcomes survival probability in COVID-19 survivors among control group (85).

Figure 7.

Cardiovascular outcomes survival probability in COVID-19 survivors among control group (85).

TriNetX Research Network The COVID-19 survivors were discovered to have higher odds of acquiring these cardiovascular problems than the controls after a 12-month follow-up (Wang W, Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated population: A retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. , 2022 N.O.V.) as described below.

Higher risks of cerebrovascular complications, such as stroke (H.R. = 1.52 [1.43-1.62]) and T.I.A. (H.R. = 1.503 [1.353-1.670]) were observed in the COVID-19 survivors (85). Atrial fibrillation and flutter (H.R. = 2.407 [2.296-2.523]), tachycardia (H.R. = 1.682 [1.626-1.740]), bradycardia (H.R. = 1.599 [1.521-1.681]), and ventricular arrhythmias (H.R. = 1.600 [1.535-1.668]) were also associated with elevated risks. In particular, myocarditis (H.R. = 4.406 [2.890-6.716]) and pericarditis (H.R. = 1.621 [1.452-1.810]) were more common among COVID-19 survivors. Ischemic heart disease (I.H.D.), including angina (H.R. = 1.707 [1.545-1.885]), acute coronary syndrome (H.R. = 2.048 [1.752-2.393]), myocardial infarction (H.R. = 1.979 [1.831-2.138]), and ischemic cardiomyopathy (H.R. = 2.811 [2.477-3.190]). The mortality rate in the COVID-19 group was higher than in the control group (H.R. = 1.604 [1.510–1.703]).

VII. Long-Term Cardiovascular Results with Covid-19 Pearls:

The care of the post-COVID syndrome necessitates comprehensive methods instead of organ- or disease-specific ones.

For those under the age of 70 and members of ethnic minority groups, the risk rise was more pronounced.

The primary target population for long-term recovery intervention is those with significantly reduced pulmonary diffusion capabilities and aberrant chest imaging symptoms.

A significant percentage mentioned joint pain, chest pain, fatigue, and dyspnoea.

Cerebrovascular disorders, dysrhythmias, pericardial or heart inflammation, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation and flutter, tachycardia, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, and thromboembolic diseases were the CVDs that were documented.

The higher chance of event aftereffects should be considered when organizing healthcare.

These results imply that cardiovascular health and illness should be part of care pathways, even for individuals who do not need to be hospitalized.

A concerted, long-term, worldwide response plan will be necessary to meet the difficulties of COVID-19.

VIII: Genetics of COVID19-induced heart complications:

Molecular biology and genetics play a role in every physiological function or pathological condition. Many recent reports have been published regarding the molecular genetic basis of cardiovascular complications in persons infected with COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been found to have detrimental effects not only on the respiratory system but on the cardiovascular system as well (86). The involvement of vascular endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes is crucial in regulating heart function, and cardiovascular disorders can arise as a result of the atypical expression of genes in vascular endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes. Xu et al. have recently identified many genes that are differently expressed in cardiomyocytes and vascular endothelial cells of heart patients infected with COVID-19, including MALAT1, CD36, LARGE1, RYR2, PLCG2 (in cardiomyocytes), MALAT1, ID1, ID3, MT-CO1 and EGFL7 (in vascular endothelial cells) (87). These genes regulate many vital functions in these cardiac cells (88-96, 97-103). The discovery of these novel contributors of COVID-19 mediated cardiac pathophysiology may help identify novel therapeutic targets. Luo et al. recalled HSP90AA1, HSPA9, and SRSF1 regulated by Mir-16-5p and KLF9 transcription factors as hub genes involved in the co-pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy (I.C.M.) and COVID-19, and they demonstrated that the co-pathogenesis of I.C.M. and COVID-19 may be associated to angiogenesis (104). It was hypothesized that vindesine and ON-01910 may act as possible therapeutic agents. The results of their research will add to a more in-depth knowledge of the correlation between I.C.M. and COVID-19. In a similar study carried out by Qi et al., V.E.G.F.A., FOXO1, CXCR4, and SMAD4 were found to be upregulated hub genes in COVID19-induced cardiomyopathy, whereas downregulated hub genes included K.R.A.S. and T.X.N. (105). Liu et al. have successfully identified some hub genes in ischemic stroke induced by COVID-19. These genes included NCR3 (natural cytotoxicity triggering receptor 3), OLR1 (oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1), IL1R2 (interleukin 1 receptor type 2), IL18R1 (interleukin 18 receptor 1), and JAK2 (Janus kinase 2). The identified hub genes, specifically JAK2, have the potential to serve as biomarkers and provide novel therapeutic targets (106).

Some recent reports about the role of specific genes and micro-RNAs in COVID-19-inducing heart failure (H.F.). Gao et al. reported upregulation of OAS1, OAS2, OAS3, and O.A.S.L. genes in cardiomyocytes from heart failure patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 infection (107). These genes belong to the OAS-gene family, contributing to antiviral and innate immune responses (108). The authors found differential expression of micro-RNAs associated with these genes, including hsa-miR-15a-3p, hsa-miR-23a-5p, hsa-miR-26b-5p, hsa-miR-186-3p, hsa-miR-4433a-3p, hsa-miR-548aq-5p, hsa-miR-548d-5p, hsa-miR-576-5p, hsa-miR-580-3p, and hsa-miR-6850-5p (107). Furthermore, Estradiol was identified to be the common molecule that regulates the four O.A.S. genes. Estradiol's ability to treat severe heart failure is mediated by the classical estrogen receptor beta (E.R.) in the heart (109). Estradiol protects right ventricular function in pulmonary hypertension via BMPR2 and apelin, as described by Frump et al. (110). These results demonstrate that Estradiol has a cardioprotective effect, even on the COVID-19 heart, and therefore can help treat patients infected with COVID-19 suffering from heart failure and other cardiac diseases COVID-19.

Some new in-depth insights into the effect of COVID-19 genes on cardiac stem cells have revealed some fascinating facts. Liu et al. have reported that COVID-19 genes (Nsp6, Nsp8, and M) severely damage human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, emphasizing the importance of ATP homeostasis in cardiomyocyte mortality and functional abnormalities caused by these SARS-CoV-2 genes (111). They found that hESC-CMs, overexpression of SARS-CoV-2 viral genes promoted cell death/apoptosis-associated gene expression and upregulated Nsp6, Nsp8, and M hESC-CM proteins caused cardiac fibrosis, arrhythmia, inflammation, and heart failure. These findings show that Nsp6, Nsp8, and M may reduce cellular ATP generation and trigger apoptosis in hPSC-CMs. They reported that FDA-approved antiparasitic and antiemetic drug meclizine can alleviate this effect (112) as meclizine promotes CM glycolysis (113), which increases ATP production, reduces ATP depletion, and protects mitochondrial function (114-115). These data support that meclizine may boost ATP levels to reduce SARS-CoV-2-induced cell death in hPSC-CMs, revealing meclizine can help treat cardiac patients infected with COVID-19. Similarly, Wu et al in very recent findings have elucidated the molecular biomarkers and genetic pathogenesis of COVID19-induced ischemic heart failure (116).

Moreover, all these recent findings show how deep insights into COVID-19-induced cardiac diseases using state-of-the-art molecular and cell biological techniques can help unravel its pathogenesis and help find novel potential therapeutic agents for patient-tailored treatment of COVID-19-associated cardiovascular diseases that is a major focus of personalized medicine in 21st century (86’116,117).

Conclusions

Ultimately, the relationship between COVID-19 and CV risk is complex and multifaceted. While COVID-19 primarily affects the respiratory system, it can also significantly affect CV health. Emerging evidence suggests that COVID-19 survivors may experience long-term CV effects. These include persistent myocardial inflammation, myocardial fibrosis, cardiac dysfunction, and an increased risk of future CV events. Moreover, the recent reports show involvement of a large number of genomic alterations, microRNAs and novel viral as well as host proteins in different types of cardiocytes, that has help identify some novel drug targets to treat COVID19 related cardiovascular complications. Long-term follow-up studies are ongoing and demanded to understand these underlying effects better, to identify novel molecular biomarkers of different cardiovascular diseases and to find novel therapeutic agents for personalized treatment of resulting clinical complications.

Funding

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) (NRA22A/012/05) that serves as Ethical Review Board of the participating centres.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzic, C.M.; Medina-Inojosa, B.J. Cardiovascular Complications of Coronavirus Disease-2019. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation Clin. North Am. 2023, 34, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.-M.; Hu, J. Single-cell analysis of adult human heart across healthy and cardiovascular disease patients reveals the cellular landscape underlying SARS-CoV-2 invasion of myocardial tissue through ACE2. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, V.M.; Plein, S.; Wong, T.C.; Tao, Q.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Jain, S.S.; Han, Y.; Ojha, V.; Bluemke, D.A.; Hanneman, K.; et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for evaluation of cardiac involvement in COVID-19: recommendations by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2023, 25, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmisano, A.; Vignale, D.; Bruno, E.; Peretto, G.; De Luca, G.; Campochiaro, C.; Tomelleri, A.; Agricola, E.; Montorfano, M.; Esposito, A. Cardiac magnetic resonance findings in acute and post-acute COVID-19 patients with suspected myocarditis. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2022, 51, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yugar-Toledo, J.C.; Yugar LB, T.; Sedenho-Prado, L.G.; Schreiber, R.; Moreno, H. Pathophysiological effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the cardiovascular system and its clinical manifestations-a mini review. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine 2023, 10, 1162837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kindi, S.; Zidar, D.A. COVID-lateral damage: cardiovascular manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Transl. Res. 2021, 241, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; White, H.D.; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction; Jaffe, A.S.; Apple, F.S..; Galvani, M.; Katus, H.A.; Newby, L.K.; Ravkilde, J.; et al. Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2007, 116, 2634–2653. [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D.; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF). Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2018, 138, e618–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaweel, M.; AlMukhaylid, S.; AlAnazi, F.; AlRammadan, A.; Altuwaim, I. Type II Myocardial Infarction: What Do We Know? Int. J. Innov. Res. Med Sci. 2022, 7, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Coronavirus. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1.

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Dong, X.; Qu, J.; Gong, F.; Han, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020, 395, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Wu, Y.; Song, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, F.; Liang, B. Possible Mechanisms of SARS-CoV2-Mediated Myocardial Injury. Cardiovasc. Innov. Appl. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerstedt, S.; Casaro, E.B.; Rangel, É.B. COVID-19: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and tissue susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 40, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imazio, M.; Klingel, K.; Kindermann, I.; Brucato, A.; De Rosa, F.G.; Adler, Y.; De Ferrari, G.M. COVID-19 pandemic and troponin: indirect myocardial injury, myocardial inflammation or myocarditis? Heart 2020, 106, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Qin, M.; Shen, B.; Cai, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, F.; Gong, W.; Liu, X.; Liang, J.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Association of Cardiac Injury with Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, Y.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr.; Jaffe, A.S. Cardiac Troponin for Assessment of Myocardial Injury in COVID-19: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1244–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Hu, B.; Hu, C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020, 323, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjid, M.; Safavi-Naeini, P.; Solomon, S.D.; Vardeny, O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: A review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhi, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Bi, Z.; Zhao, Y. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020, 109, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; Yan, W.; Yang, D.; Chen, G.; Ma, K.; Xu, D.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020, 368, m1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Wahaibi, K.; Al-Wahshi, Y.; Elfadil, O.M. Myocardial Injury Is Associated with Higher Morbidity and Mortality in Patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 2514–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Pan, L.-Y.; Jiang, H.-Y. ACEI/ARB use and risk of infection or severity or mortality of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 158, 104927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Shi, X.; Yu, J.; Lv, F.; Wu, J.; Sheng, X.; Pan, Q.; Yang, J.; Cao, H.; Li, L. Association of ACEi/ARB Use and Clinical Outcomes of COVID-19 Patients with Hypertension. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 577398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Ren, L.; Yang, S.; Xiao, M.; Chang, D.; Yang, F.; Cruz, C.S.D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Profiling Early Humoral Response to Diagnose Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giustino, G.; Pinney, S.P.; Lala, A.; Reddy, V.Y.; Johnston-Cox, H.A.; Mechanick, J.I.; Halperin, J.L.; Fuster, V. Coronavirus and Cardiovascular Disease, Myocardial Injury, and Arrhythmia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, R.; Sheng, J. Host susceptibility to severe COVID-19 and establishment of a host risk score: findings of 487 cases outside Wuhan. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglin, M.; Ballut, K.; Ilonze, O.; Jones, M.; Rao, R. Clinical variants of myocardial involvement in COVID-19-positive patients: a cumulative experience of 2020. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2021, 27, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.Z.; Pradipta, A. Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: A Brief Review. J. Med. Life 2020, 13, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Fan, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, T.; Wang, H.; Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelle, M.C.; Zaffina, I.; Lucà, S.; Forte, V.; Trapanese, V.; Melina, M.; Giofrè, F.; Arturi, F. Endothelial Dysfunction in COVID-19: Potential Mechanisms and Possible Therapeutic Options. Life 2022, 12, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trachtenberg, B.H.; Hare, J.M. Inflammatory Cardiomyopathic Syndromes. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Liu, M.; Sun, R.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, P. Myocardial Infarction: Symptoms and Treatments. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 72, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, R.B.; Botelho, B.G.; de Hollanda, J.V.G.; Ferreira, L.V.L.; de Andrade, L.Z.J.; Oei, S.S.M.L.; Mello, T.d.S.; Muxfeldt, E.S. Covid-19 and the cardiovascular system: a comprehensive review. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2020, 35, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferry, A.V.; Anand, A.; Strachan, F.E.; Mooney, L.; Stewart, S.D.; Marshall, L.; Chapman, A.R.; Lee, K.K.; Jones, S.; Orme, K.; et al. Presenting Symptoms in Men and Women Diagnosed With Myocardial Infarction Using Sex-Specific Criteria. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e012307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Prete, A.; Conway, F.; Della Rocca, D.G.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; De Felice, F.; Musto, C.; Picichè, M.; Martuscelli, E.; Natale, A.; Versaci, F. COVID-19, Acute Myocardial Injury, and Infarction. Card. Electrophysiol. Clin. 2022, 14, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hothi, S.S.; Jiang, J.; Steeds, R.P.; Moody, W.E. Utility of Non-invasive Cardiac Imaging Assessment in Coronavirus Disease 2019. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 663864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, D.; Dominic, P.; Sheth, A.; Modi, M. Prognostic value of Cardiac Biomarkers in COVID-19 Infection: A Meta-analysis. Preprint. Res Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A.; Ryoo, S.G. Prevalence of comorbidities in the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 49, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inciardi, R.M.; Lupi, L.; Zaccone, G.; Italia, L.; Raffo, M.; Tomasoni, D.; Cani, D.S.; Cerini, M.; Farina, D.; Gavazzi, E.; et al. Cardiac Involvement in a Patient with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.; Saleh, M.; Gabriels, J.; Ismail, H.; Goldner, B.; Willner, J.; Beldner, S.; Mitra, R.; John, R.; Epstein, L.M. Inpatient Use of Ambulatory Telemetry Monitors for COVID-19 Patients Treated with Hydroxychloroquine and/or Azithromycin. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2992–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramireddy, A.; Chugh, H.; Reinier, K.; Ebinger, J.; Park, E.; Thompson, M.; Cingolani, E.; Cheng, S.; Marban, E.; Albert, C.M.; et al. Experience with Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: Implications for QT Interval Monitoring. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2020, 9, e017144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, B.A.; Andrade, M.J.; Badano, L.P.; Fox, K.F.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Lancellotti, P.; Varga, A.; Sicari, R.; Evangelista, A.; Nihoyannopoulos, P.; et al. European Association of Echocardiography recommendations for training, competence, and quality improvement in echocardiography. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2009, 10, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameli, M.; Pastore, M.C.; Aboumarie, H.S.; Mandoli, G.E.; D'Ascenzi, F.; Cameli, P.; Bigio, E.; Franchi, F.; Mondillo, S.; Valente, S. Usefulness of echocardiography to detect cardiac involvement in COVID-19 patients. Echocardiography 2020, 37, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulstad, H.; Cosyns, B.; A Popescu, B.; Galderisi, M.; Di Salvo, G.; Donal, E.; Petersen, S.; Gimelli, A.; Haugaa, K.H.; Muraru, D.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritization, and protection for patients and healthcare personnel. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 21, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Mitchell, C.; Taub, C.; Kort, S.; Hung, J.; Swaminathan, M. ASE Statement on Protection of Patients and Echocardiography Service Providers During the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak: Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 clinical guidance for the cardiovascular care team. Acc.org. Available online: https://www.acc.org/~/media/665AFA1E710B4B3293138D14BE8D1213.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Allen, B.D.; Wong, T.C.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bryant, J.; Chen, T.; Dall’armellina, E.; Finn, J.P.; Fontana, M.; Francone, M.; Han, Y.; et al. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) guidance for re-activation of cardiovascular magnetic resonance practice after peak phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2020, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.; McKenna, W.; Bristow, M.; et al. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of Cardiomyopathies. Circulation 1996, 93, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.; Klingel, K.; Kandolf, R.; Sechtem, U. Imaging in inflammatory heart disease: from the past to current clinical practice. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2009, 50, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-P.; Im, H.-J.; Kang, S.; Chung, S.-J.; Cho, Y.S.; Kang, H.; Park, H.S.; Hwang, D.-W.; Park, J.-B.; Paeng, J.-C.; et al. Noninvasive Imaging of Myocardial Inflammation in Myocarditis using 68Ga-tagged Mannosylated Human Serum Albumin Positron Emission Tomography. Theranostics 2017, 7, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cau, R.; Bassareo, P.; Saba, L. Cardiac Involvement in COVID-19—Assessment with Echocardiography and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Chen, T.; Bryant, J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Dyke, C.; Elliott, M.D.; Ferrari, V.A.; Friedrich, M.G.; Lawton, C.; Manning, W.J.; et al. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) guidance for the practice of cardiovascular magnetic resonance during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2020, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakol, M.; Ashraf, S.; Brener, S.J. Risks and Complications of Coronary Angiography: A Comprehensive Review. Glob. J. Heal. Sci. 2011, 4, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coy, K.M.; Maryniak, A.; Blankespoor, T.; Stys, A. Approach to high intracoronary thrombus burden in the era of COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e246223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liori, S.; Pappas, C.; Rallidis, L. ST-elevation myocardial infarction in a 39-year-old patient with “normal” coronary arteries as a thrombotic complication of COVID-19. J. Cardiol. Cases 2022, 25, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccolo, R.; Esposito, G. Percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with COVID-19 and acute coronary syndrome: What if the old normal became the new normal? Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 97, 199–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wei, H.; Ma, G.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, P. Comparison of prognosis between coronary computed tomography angiography versus invasive coronary angiography for stable coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1010536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inam, F.; Singh, P.R.; Khalid, F.; Javed, A.; Shah, A.R. Acute Coronary Syndrome and COVID-19: A Case Report of Refractory Hypercoagulability. Cureus 2021, 13, e13675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M.; Wheen, P.; Armstrong, R.; Kumar, R.; McMahon, A.; White, M.; Sheehy, N.; McMahon, G.; Murphy, R.T.; Daly, C. CT coronary angiography and COVID-19: inpatient use in acute chest pain service. Open Hear. 2021, 8, e001548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjer, M.; Dobrolinska, M.; Wagenaar, N.R.L.; Slart, R.H.J.A. Diagnostic accuracy of dynamic CZT-SPECT in coronary artery disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2021, 29, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Fan, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; He, T.; Wang, H.; Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driggin, E.; Madhavan, M.V.; Bikdeli, B.; Chuich, T.; Laracy, J.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Brown, T.S.; Der Nigoghossian, C.; Zidar, D.A.; Haythe, J.; et al. Cardiovascular Considerations for Patients, Health Care Workers, and Health Systems During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2352–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Fang, Y.-Y.; Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, M.-F.; Ma, J.-P.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Y.-N.; Zhong, M.-H.; Li, C.-H.; et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin. Med J. 2020, 133, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satterfield, B.A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Gersh, B.J. Publisher Correction: Cardiac involvement in the long-term implications of COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 19, 342–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelle, M.P.; Desai, A.D.; Wan, E.Y. Arrhythmias in the COVID-19 patient. Hear. Rhythm. O2 2022, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretto, G.; Sala, S.; Rizzo, S.; De Luca, G.; Campochiaro, C.; Sartorelli, S.; Benedetti, G.; Palmisano, A.; Esposito, A.; Tresoldi, M.; et al. Arrhythmias in myocarditis: State of the art. Hear. Rhythm. 2018, 16, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, X.; Chen, M.; Feng, Y.; Xiong, C. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1097–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudelka, M.; Sovová, E. COVID-19 Causing Hypotension in Frail Geriatric Hypertensive Patients? Medicina 2021, 57, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, G.; De Pascalis, V.; Favieri, F.; Casagrande, M. Effects of Blood Pressure on Cognitive Performance: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, S.; Mami, S.; Mohtadi, N.; Ghaysouri, A.; Tavan, H.; Nazari, A.; Kokhazadeh, T.; Mollazadeh, R. Sudden cardiac death in COVID-19 patients, a report of three cases. Futur. Cardiol. 2021, 17, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beri, A.; Kotak, K. Cardiac injury, arrhythmia, and sudden death in a COVID-19 patient. Hear. Case Rep. 2020, 6, 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.; Bansal, R.; Budakoty, S.; Barwad, P. COVID-19 and sudden cardiac death: A new potential risk. Indian Hear. J. 2020, 72, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Jin, Z. An Acute Respiratory Infection Runs Into the Most Common Noncommunicable Epidemic—COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Diseases. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 743–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Xie, Y.; Bowe, B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 594, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoubkhani, D.; Khunti, K.; Nafilyan, V.; Maddox, T.; Humberstone, B.; Diamond, I.; Banerjee, A. Post-covid syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with covid-19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2021, 372, n693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. RETRACTED: 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfì, A.; Bernabei, R.; Landi, F. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, S.E.; Guo, Y.; Heath, K.; Dasmariñas, M.C.; Jubilo, K.G.; Samranvedhya, J.; Lipsitch, M.; Cohen, K. Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2021, 373, n1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, C.-Y.; Wang, S.-I.; Wei, J.C.-C. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated population: A retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 53, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yang, J.; Kang, P.; Bai, J.; Feng, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tang, B.; Wang, H.; et al. Direct infection of SARS-CoV-2 in human iPSC-derived 3D cardiac organoids recapitulates COVID-19 myocarditis. Virol. Sin. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Ren, J.; Chen, L.; Guo, W.; Feng, K.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, T.; Cai, Y. Using Machine Learning Methods in Identifying Genes Associated with COVID-19 in Cardiomyocytes and Cardiac Vascular Endothelial Cells. Life 2023, 13, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Gu, H.; Xu, W.; Zhou, X. Down-regulation of lncRNA MALAT1 reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improves left ventricular function in diabetic rats. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 203, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Wu, J.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Yu, H.; Ma, L. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 enhances the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes through autophagy inhibition by regulating TSC2-mTOR signaling. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthanveetil, P.; Chen, S.; Feng, B.; Gautam, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 regulates hyperglycaemia induced inflammatory process in the endothelial cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 1418–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Chen, F.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, D.; Fu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yuan, W.; Yuan, W.; et al. MALAT1 regulates hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes by modulating the miR-181a/HMGB2 pathway. Eur. J. Histochem. 2022, 66, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glatz, J.F.; Wang, F.; Nabben, M.; Luiken, J.J. CD36 as a target for metabolic modulation therapy in cardiac disease. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2021, 25, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Huang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, H.; An, Y. CTCF inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes by upregulating RYR2 via inhibiting S100A1. Life Sci. 2019, 242, 117158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Nanno, T.; Fukui, G.; Sufu, Y.; Hamada, Y.; Maeda, T.; Nishimura, S.; Ishiguchi, H.; et al. Correction of impaired calmodulin binding to RyR2 as a novel therapy for lethal arrhythmia in the pressure-overloaded heart failure. Hear. Rhythm. 2016, 14, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acimovic, I.; Refaat, M.M.; Moreau, A.; Salykin, A.; Reiken, S.; Sleiman, Y.; Souidi, M.; Přibyl, J.; Kajava, A.V.; Richard, S.; et al. Post-Translational Modifications and Diastolic Calcium Leak Associated to the Novel RyR2-D3638A Mutation Lead to CPVT in Patient-Specific hiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X. Investigating the protective contribution of PLCG2 P522R variant in microglia-mediated immune pathways in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2022, 18, e062813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, T.J.; Yu, M.S.; McKeithan, W.L.; Spiering, S.; Carrette, F.; Huang, C.-T.; Bushway, P.J.; Tierney, M.; Albini, S.; Giacca, M.; et al. Id genes are essential for early heart formation. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D.; He, M.; Yang, L.; Zhou, R.; Yan, Y.-Q.; Liang, Y.; Teng, C.-B. MiR-17 and miR-19 cooperatively promote skeletal muscle cell differentiation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 5041–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, G.; Ren, T.; Zhang, T.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y. Screening of host genes regulated by ID1 and ID3 proteins during foot-and-mouth disease virus infection. Virus Res. 2021, 306, 198597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattarabanjird, T.; Cress, C.; Nguyen, A.; Taylor, A.; Bekiranov, S.; McNamara, C. A Machine Learning Model Utilizing a Novel SNP Shows Enhanced Prediction of Coronary Artery Disease Severity. Genes 2020, 11, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, D.; Jia-wei, Z.; Yan-an, W. Current research progress of egfl7 in angiogenesis regulation. China J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 17, 377–content content. [Google Scholar]

- Masoud, A.G.; Lin, J.; Azad, A.K.; Farhan, M.A.; Fischer, C.; Zhu, L.F.; Zhang, H.; Sis, B.; Kassiri, Z.; Moore, R.B.; et al. Apelin directs endothelial cell differentiation and vascular repair following immune-mediated injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 130, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer Zhmurov, C.; Timirci-Kahraman, O.; Amadou, F.Z.; Fazliogullari, O.; Basaran, C.; Catal, T.; Zeybek, U.; Bermek, H. Expression of Egfl7 and miRNA-126-5p in Symptomatic Carotid Artery Disease. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 2016, 20, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, X.; Luo, W.; Yang, Z.; Tang, S.; Huang, W. Exploring Potential Biomarkers and Molecular Mechanisms of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy and COVID-19 Comorbidity Based on Bioinformatics and Systems Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.; Huang, M.; Zhu, H. Exploring potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets of long COVID-associated inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1191354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Han, F.; Wan, M.; Yang, X.-Z. Integrated bioinformatics analysis identifies shared immune changes between ischemic stroke and COVID 19. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.-J.; He, Z.-M.; Li, Y.-Y.; Yang, R.-R.; Yan, M.; Shang, X.; Cao, J.-M. Role of OAS gene family in COVID-19 induced heart failure. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boroujeni, M.E.; Simani, L.; Bluyssen, H.A.R.; Samadikhah, H.R.; Zamanlui Benisi, S.; Hassani, S.; Dilmaghani, N.A.; Fathi, M.; Vakili, K.; Mahmoudiasl, G.-R.; et al. Inflammatory Response Leads to Neuronal Death in Human Post-Mortem Cerebral Cortex in Patients with COVID-19. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorga, A.; Umar, S.; Ruffenach, G.; Aryan, L.; Li, J.; Sharma, S.; Motayagheni, N.; Nadadur, R.D.; Bopassa, J.C.; Eghbali, M. Estrogen rescues heart failure through estrogen receptor Beta activation. Biol. Sex Differ. 2018, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frump, A.L.; Albrecht, M.; Yakubov, B.; Breuils-Bonnet, S.; Nadeau, V.; Tremblay, E.; Potus, F.; Omura, J.; Cook, T.; Fisher, A.; et al. 17β-estradiol and estrogen receptor α protect right ventricular function in pulmonary hypertension via BMPR2 and apelin. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e129433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Wan, J.; Yang, L. SARS-CoV-2 viral genes Nsp6, Nsp8, and M compromise cellular ATP levels to impair survival and function of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, H.; Satomi, T.; Abiru, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Nagasawa, K.; Maruyama, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Kikuchi, K.; Fuse, H.; Noda, M.; et al. Antihypertrophic Effects of Small Molecules that Maintain Mitochondrial ATP Levels Under Hypoxia. EBioMedicine 2017, 24, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, H.; Satomi, T.; Abiru, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Nagasawa, K.; Maruyama, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Kikuchi, K.; Fuse, H.; Noda, M.; et al. Antihypertrophic Effects of Small Molecules that Maintain Mitochondrial ATP Levels Under Hypoxia. EBioMedicine 2017, 24, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, V.M.; Sheth, S.A.; Nilsson, R.; Wojtovich, A.P.; Lee, J.H.; Perocchi, F.; Chen, W.; Clish, C.B.; Ayata, C.; Brookes, P.S.; et al. Nutrient-sensitized screening for drugs that shift energy metabolism from mitochondrial respiration to glycolysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, M.; Gorgun, M.F.; Englander, E.W. Augmentation of glycolytic metabolism by meclizine is indispensable for protection of dorsal root ganglion neurons from hypoxia-induced mitochondrial compromise. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 99, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Zhou, J.; Ren, H.; Qin, Y.; Qian, D.; Hu, Q.; Xu, P.; Yu, T.; Ma, H.; Chen, H.; et al. Unraveling the molecular crosstalk and immune landscape between COVID-19 infections and ischemic heart failure comorbidity: New insights into diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic approaches. Cell. Signal. 2023, 112, 110909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, L.; Lomagno, A.; Mauri, P.L.; Di Silvestre, D. Integration of Omics Data and Network Models to Unveil Negative Aspects of SARS-CoV-2, from Pathogenic Mechanisms to Drug Repurposing. Biology 2023, 12, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).