Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) represents a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract which includes classically ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Both conditions display heterogeneity in inflammatory and symptomatic burden, either between patients, and within the same individual over time (1).

The differential diagnosis is supported by distinct clinical presentation, involvement of different sections of the gastrointestinal tract and, mostly, histological features observed on biopsy specimen. On the other hand, the contribution given by laboratory markers is still very limited. Recently, new tests with promising performances have been made available on the market, but the real impact on clinical practice is already unclear. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) represent an established biomarker of CD, while goblet cell antibodies (GAB) and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies with atypical perinuclear IIF pattern (P-ANCA) have been significantly associated with UC (2, 3). Among the newly identified biomarkers, increasing evidence suggests a potential role of pancreatic autoantibodies (PAB) in CD. The first work describing the presence of PAB by IIF in the serum of patients with CD dates back to 1984 . Afterwards, several other studies addressed this issue and the prevalence of PAB in CD series varies from 15 to maximum 40% (2, 5-19), with large variability across the studies. Furthermore, while some authors reported a significant correlation between PAB and features of severe disease such as penetrating behavior or perianal localization (13), others did not confirm this association (9, 11). While the correlation between PAB positivity and extra-intestinal CD manifestations, such as idiopathic chronic pancreatitis, was reported more consistently (11, 13, 20-22). PAB were also associated with small bowel disease and surgery (9) and early age disease onset (11). The discrepancies between the studies might be attributed to the lack of standardized methods to test PAB by IIF. More recently, the proper identification of the pancreatic auto-antigenic targets: glycoprotein 2 (GP2) (18, 23) and CUB/zona pellucida-like domain-containing protein (CUZD1) (24), allowed a more effective and reproducible identification of PAB, offering also a possible better explanation of the pathogenic role of PAB in CD. GP2 in particular, appears to have a solid link with the intestinal disease involvement in CD patients. Hase et al. identified GP2 as a specific receptor on M cells in the intestinal Peyer’s patches (25-27). Since then, several researchers provided evidence that GP2 may play an important role in keeping the balance of the intestinal immune system by helping to differentiate between pathogenic and commensal microbiota (28). The loss of tolerance to pancreatic and/or intestinal GP2 could modulate the pathophysiology of CD (29). Increased expression of GP2 mRNA and protein were found in intestinal biopsy samples of some CD patients (23, 29) and several studies conducted on CD patient series disclosed GP2, as well as CUZD1 antibodies, associated with distinct clinical phenotypes (30-33). Although literature data were promising, PABs have not yet entered laboratory routine, because it is not clear what role they may play within the diagnostic process and above all, easy-to-use and low-cost tests are not still available. The main ain of this study was to evaluate the performance of a commercial multiparametric method for diagnosis and profiling of IBD patients, in order to support its introduction into clinical practice.

Methods

This multicenter observational retrospective study was conducted on 156 consecutive patients with IBD enrolled between January 2017 and December 2018 at three participating units: the Gastroenterology of the Academic Hospital of Udine in Italy, the Gastroenterology of the Hospital of Rijeka in Croatia and the Gastroenterology of the University Clinic Dr Dragisa Misovic-Dedinje of Belgrade in Serbia. The serum samples were collected recovering the residual serum after the required routine analyzes for ASCA and ANCA. All the sera were anonymised and sent to the Euroimmun laboratory to carry out the new mosaic tests. The study has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Inclusion criteria implied endoscopically and histologically confirmed CD or UC, age above 18 and collaborative ability. The following data were collected: demographics, lifestyle habits, age of diagnosis, medical as well as surgical treatments, disease activity (evaluated according to Montreal classification; 34). Only patients already known and diagnosed with confirmed CD or UC for more than two years were finally included, and they were sampled as routinely scheduled on the occasion of checkups, infusions of biological drugs, hospitalizations, without subjecting them to additional visits or withdrawals. All patients had an established diagnosis, based on internationally accepted clinical, endoscopic, radiological and histological criteria. Patients with an uncertain diagnosis or with features suggestive of another coexisting intestinal disease were excluded. Twenty blood donors (BD; mean age 42.7 ±13.5 years, 7F/13M) serum samples were recruited at the Laboratory of the Academic Hospital in Udine recovering the rejected serum after the foreseen routine analyses and anonymised to be used as control group.

Laboratory Analysis

Blood samples were collected in tubes without anti-coagulant and then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 minutes to obtain the serum. Each serum was then aliquoted in 1ml polypropylene tubes identified by a unique numerical code and frozen at -20°C until shipping. Subsequently, frozen sera were sent to the laboratory of EUROIMMUN Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG in Lübeck, Germany, where they were tested blindly.

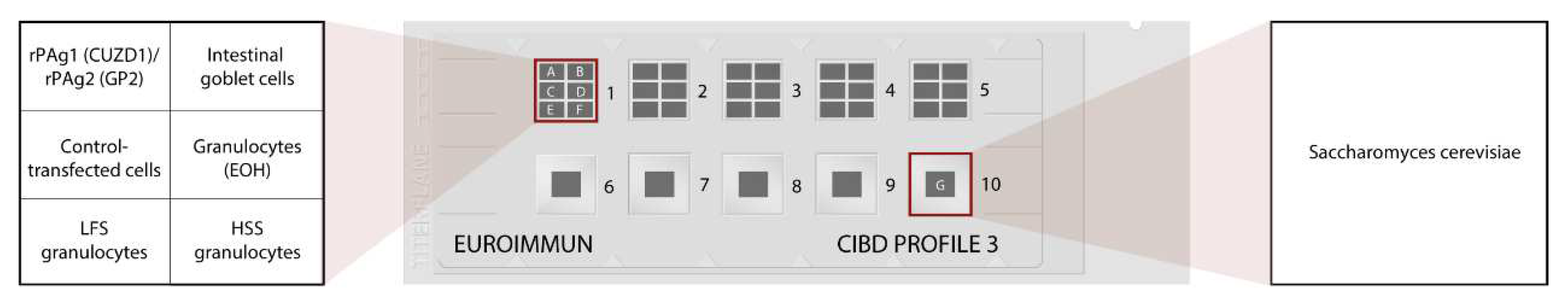

Autoantibody profiles were determined in serum samples by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) using the mosaic CIBD Profile 3 (EUROIMMUN Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG, Lübeck, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both IgG and IgA auto-antibodies were tested. The BIOCHIP Mosaic comprises different IIF substrates (cell substrates, fungal smears or transfected cells) based on which specific autoantibodies directed against intestinal goblet cells, DNA-bound lactoferrin (that is the major target for anti-neutrophil perinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies in UC; 35), exocrine pancreas (CUZD1 and GP2), and saccharomyces cerevisiae were detected simultaneously (

Figure 1). The samples were evaluated by experienced investigators using an Axio Scope A1 microscope from Zeiss (Jena, Germany).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were compared with a χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence interval (CI). The clinical relevance of antibodies was assessed with multivariate logistic regression and exact logistic regression models. P-values were considered significant if p<0.05. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were calculated and compared using McNemar test. Statistical tests were performed by SPSS 16.1 statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

The study finally enrolled 100 patients with CD (57 in Udine, 23 in Rijeka, 20 in Belgrade) and 56 patients with UC (33 in Belgrade, 23 in Udine). The demographic and clinical features of study patients divided according to the recruiting center are illustrated in

Table 1. CD patients disclosed several important differences among centers: biologic therapy, young age (<40yrs) at diagnosis and perianal disease were features much more present in Udine, while extraintestinal manifestations were apparently absent in Belgrade, where smoking was instead highly frequent; finally a structuring/penetrating disease was more frequent in Rijeka. Such differences were also noticed among the UC patients. These differences reflect the epidemiological features, but also the access to care modalities of each participating center. The overall distribution of the laboratory data obtained from the analysis of the mosaic CIBD profile 3 in patients (CD and UC) and in controls (BD) is shown in

Table 2. PAB positivity in general (CUZD1 and/or GP2 IgG/IgA) was present in 24/100 (24%) patients with CD and none of the patients with UC or BD (100% specificity). Among PAB positive CD patients, 17 were positive for CUZD1 (only IgG: 7%, only IgA: 2%, both: 8%), 11 were positive for GP2 (only IgG: 7%, only IgA: 2%, both: 8%), and 4 patients were positive both for CUZD1 and GP2 antibodies. As expected, ASCA (IgG and/or IgA) were significantly more frequent in CD patients than in UC (p<0.001), while GAB (IgG and/or IgA) and anti-DNA-bound lactoferrin (LFS) p-ANCA (IgG and/or IgA) were significantly more present in patients with UC than in CD (p<0.001 both).

As illustrated in

Table 3, PAB were less sensitive in discriminating CD vs. UC in comparison to ASCA (24% vs.78%, p<0.001). However, PAB in general, as well as CUZD1 and GP2 individually, showed both 100% specificity and PPV in comparison to 71.4% and 83% of ASCA, respectively. On the other hand, GAB and anti-LFS granulocytes displayed sensitivity of 50% and 64.3% and specificity of 92% and 75%, respectively, in discriminating UC vs. CD (p=0.12). Of note, the combined testing of ASCA and PAB performed better in differentiating CD vs. UC (sensitivity=84%, specificity=71.4%) than ASCA alone (p=0.014). Supplementary

Tables S1, S2 and S3 illustrate the results of the serological analyses of each recruiting center. Of note, CD patients recruited in Belgrade had significantly higher prevalence of GAB in comparison to Rijeka and Udine (30% vs. 8.7% vs. 0.0%; p<0.001). On the other hand, LFS granulocytes IgG antibodies were significantly more present among CD patients recruited in Udine in comparison to Rijeka and Belgrade (24.6% vs. 17.4% vs. 0.0%; p=0.048).

Table 4 illustrates demographics, lifestyle, clinical and laboratory data in PAB-positive and PAB-negative CD patients. The patients did not differ for age, sex and smoking. Among the several clinical features investigated, colon involvement (87.5% vs. 60.5%; p=0.014), development of deep mucosal lesions (58.3% vs. 25.0%; p=0.002) and need for therapy with biological agents (79.2% vs. 46.1%; p=0.005) were significantly more prevalent in PAB- positive (CUZD1 IgG/IgA and/or GP2 IgG/IgA) than in PAB-negative patients. Demographics, lifestyle and clinical/laboratory data of CD patients positive for CUZD1 (IgG and/or IgA) and GP2 (IgG and/or IgA) separately are reported in

Supplementary Tables S4 and S5. When tested separately, the presence of colon involvement (p=0.041 for CUZD1 and p=0.022 for GP2, respectively), deep mucosal lesions (p=0.013 for CUZD1) and biological therapies (p=0.01 for CUZD1 and p=0.05 for GP2, respectively) were more elevated in CUZD1-positive and GP2-positive patients.

The adjusted multivariate analysis (

Table 5) confirmed a significant association between PAB positivity in general and the presence of deep mucosal lesions (OR=3.67; 95%CI=1.29-10.46), while association with colon involvement was borderline significant (OR=3.83; 95%CI=0.98-14.92). As for CUZD1 and GP2 individually, only anti-CUZD1 appeared to be a significant risk factor for deep mucosal lesions development (OR=3.54; 95%CI=1.08-11.63).

Discussion

In this multicenter study we tested the performance of the combined analysis of multiple antibody markers in differentiating CD versus UC patients using an IIF mosaic. Our study confirmed that the presence of PAB is significantly more frequent in CD than in UC and is associated with the development of clinical manifestations characteristic of the most severe forms of CD, such as deep mucosal lesions, colon involvement and need for biologic therapies. Our study showed PAB positivity in general as having 100% specificity and high PPV in differentiating CD versus UC, making it very useful in situations when other methods (clinical picture, endoscopy, histology) remain with inconclusive results.

Although the literature agrees in reporting a low (maximum 40%) prevalence of PAB in CD patients (2, 5-19, 30-32, 36-40), there is a great heterogeneity as regards the correlation with clinical features. If we consider the disease behavior, PAB have been reported to be associated with strictures (2, 32, 36, 41, 42). However, some authors have also reported an association with penetrating CD (13, 40) and even a negative association with stricturing behavior (8). As regards the localization of disease, ileum (30, 31, 40) and ileocolon (32, 36, 39) were most frequently associated with PAB positivity, followed by perianal disease (13, 32, 36). Interestingly, an association between the presence of PAB and pouchitis has also been proposed (43), offering a possible explanation of the role of PAB in the pathogenic process of IBD. Another feature of CD frequently associated with PAB in the literature is disease onset at early age (11, 31, 32, 42). In relation to therapeutic intervention, PAB have been associated with need for surgery (9, 37, 38, 41) and therapy with immune suppressors (36). On the other hand, data on a possible association with biologic therapies is poor, except for one paper reporting a negative association (39). We showed PAB to be associated with deep mucosal lesions and colonic localization as well as a possible association with early introduction of biologic therapies. At our knowledge, deep mucosal lesions have not yet been associated with PAB. However, frequently reported associations with stricturing or penetrating behavior are in line with our findings, as deep mucosal lesions may precede stricture and penetrating disease. Of note, this is the first study reporting a strong correlation between PAB positivity and colonic localization in CD. As the majority of patients with colonic involvement were also affected by terminal ileal disease, probably the colonic extension is due more to the intensity of the histological damage than to a pathological process typical of the colon. Moreover, previously conducted studies suggested terminal ileum as a potential localization of disease activity where PAB, in particular GP2, can play a role in the pathogenic process of CD (30). Although our report is the first to identify the presence of PAB as a possible risk factor for the need of early introduction of biologic agents, several features of severe CD were already recognized as risk factors for biologic therapies, which is in line with our findings.

The ideal diagnostic test has been defined as one never being positive in a control group and never negative in patients affected by a certain disease (44). Power et al. suggested that, for a test to be considered useful, the sum of sensitivity and specificity must exceed 1.5, ideally reaching 2.0 (45). We assessed the diagnostic accuracy of the mosaic assay comprising multiple biomarkers in differentiating CD and UC. Among all the markers tested, only ASCA reached a sum of sensitivity and specificity of 1.5. This was expected as ASCA have been previously well-recognized as a valuable diagnostic tool in CD (46). However, when addressing the possible role of PAB in differentiating CD versus UC, apart from low sensitivity (24%), we identified 100% specificity and high PPV. We should point out that these data refer to the combined use of CUZD1 and GP2, as our analysis found them to perform better than each one alone. Two recently published meta-analyses summarized data on diagnostic performances of GP2 in CD. Deng et al. reported that the combination of IgA and/or IgG GP2 antibodies have an overall sensitivity of 24% and a specificity of 96% (47). Gkiouras et al. reported pooled sensitivity of 20% and a median specificity of 97% (48). Diagnostic tests with low sensitivity and high specificity represent ideal screening tools. Therefore, PAB can be a suitable biomarker for CD in patients with suspected IBD or IBD related symptoms, especially in cases where endoscopy and histopathology remain with inconclusive results. Finally, our study also demonstrated an important advantage when testing PAB and ASCA together, as combined testing performed better than ASCA alone. Nevertheless, high quality double-blind cohort studies including consecutive patients with suspected CD are needed to provide more evidence on these findings. According to the European Crohn and Colitis Organization, serological testing is currently not recommended for diagnosis of CD or UC (49), but they are routinely investigated in the current practice, since IBD-like symptoms are very frequent in the general population and serological tests together with fecal calprotectin are very effective at excluding a diagnosis of IBD. In contrast, they may not be sufficient to differentiate the hybrid forms involving the colon and in these cases the PAB appear to have a very promising role. The opportunity to tests these new biomarkers with commercial methods easily performed in the Laboratory is an essential step to improve the serological diagnostics of IBD.

As regards the other antibodies which are included in the mosaic herein tested, our findings on sensitivity and specificity of GAB and anti-LFC in UC patients are in line with previously reported data (50). Of note, GAB positive UC patients were more prevalent among patients enrolled in Belgrade, which are those less treated with biological agents. One possible explanation for this difference may be that biological agents would have reduced GAB expression in the other series. But this hypothesis must be confirmed in larger studies focused on UC.

The possibility to test simultaneously all these antibodies appears of great interest especially in the early phase of the diagnostic process, as may offer the most complete analysis of all the available biomarkers for IBD at the moment.

Our study has some limitations. We performed a multicenter study in order to obtain in a limited time a sufficient number of cases, but any lack of significant association could also be explained by insufficient statistical power. The features of patients recruited in the three centers were different, but these differences eventually led to the creation of a large group of patients with a more balanced representation of the different phenotypic expressions of the two diseases, something that the collection of patients in one center during the same period of time would not have allowed. Since in this study we recruited not only newly diagnosed patients but also those seen during the follow-up and already under treatment with biologic agents, we may have reduced the sensitivity of PAB and GAB and their potential impact on the early diagnosis of CD and UC. However, the percentage of PAB positive patients was in line with previous studies. Only a study focused on early diagnosis will clarify if PAB and GAB are more present in this setting. On the other hand, the additional value of our findings is represented by the collaboration among international gastroenterologists that has contributed to the dissemination of the knowledge of these new IBD markers and of the current possibility to test them all together by an available laboratory method.

In conclusion, PAB, either isolated, but more in combination with other new and established biomarkers, can be helpful in differential diagnosis of CD, especially in the cases when endoscopy and histopathology remain inconclusive. PAB-positive CD patients disclosed more frequently a severe phenotype with trend of increased need for biological therapies. However, the clinical relevance of our findings needs to be confirmed in larger series and hopefully prospective studies, which will be facilitated by the use of this new commercially available method.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Funding

Laboratory analyses were partly funded by EUROIMMUN Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG, Luebeck, Germany, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (

http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the respective Institutional Review Board (IRB) or equivalent committee: for Udine IRB 97/2023; for Belgrade n. 01-5331/9; for Rijeka n. 003-05/18-1/105 - 2170-29-02/1-18-2 approved 23.10.2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in this study.

Acknowledgments

We really thanks all the nurses of the gastroenterology units and all the technicians of the Laboratory of Immunopathology.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors state no conflict of interest and none of them benefits from any potential or actual financial or non-financial gain as a result of this work. Silvia Jacobsen is an employee of EUROIMMUN Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG.

References

- Kovacs M, Lakatos PL, Papp M, Jacobsen S, Nemes E, Polgar M, et al. Pancreatic autoantibodies and autoantibodies against goblet cells in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2012, 55, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp M, Altorjay I, Lakos G, Tumpek J, Sipka S, Dinya T, et al. Evaluation of the combined application of ethanol-fixed and formaldehyde-fixed neutrophil substrates for identifying atypical perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2009, 16, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöcker W, Otte M, Ulrich S, Normann D, Stöcker K, Jantschek G. Autoantibodies against the exocrine pancreas and against intestinal goblet cells in the diagnosis of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 1984, 109, 1963–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Stöcker W, Otte M, Ulrich S, Normann D, Finkbeiner H, Stöcker K, et al. Autoimmunity to pancreatic juice in Crohn's disease. Results of an autoantibody screening in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology Supplement. 1987, 139, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad K, Schmechta H, Klafki A, Lobeck G, Uhlig HH, Gerdi S, et al. Serological differentiation of inflammatory bowel diseases. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2002, 14, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Koutroubakis IE, Drygiannakis D, Karmiris K, Drygiannakis I, Makreas S, Kouroumalis EA. Pancreatic autoantibodies in Greek patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2005, 50, 2330–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joossens S, Vermeire S, Van Steen K, Godefridis G, Claessens G, Pierik M, et al. Pancreatic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2004, 10, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold F, Weber P, Jenss H, Wiedmann KH. Antibodies to a trypsin sensitive pancreatic antigen in chronic inflammatory bowel disease: specific markers for a subgroup of patients with Crohn's disease. Gut. 1991, 32, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folwaczny C, Noehl N, Endres SP, Loeschke K, Fricke H. Antineutrophil and pancreatic autoantibodies in first-degree relatives of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 1998, 33, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desplat-Jégo S, Johanet C, Escande A, Goetz J, Fabien N, Olsson N, et al. Update on Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies, anti-nuclear associated anti-neutrophil antibodies and antibodies to exocrine pancreas detected by indirect immunofluorescence as biomarkers in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases: results of a multicenter study. World journal of gastroenterology. 2007, 13, 2312–2318. [Google Scholar]

- Demirsoy H, Ozdil K, Ersoy O, Kesici B, Karaca C, Alkim C, et al. Anti-pancreatic antibody in Turkish patients with inflammatory bowel disease and first-degree relatives. World journal of gastroenterology. 2010, 16, 5732–5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakatos PL, Altorjay I, Szamosi T, Palatka K, Vitalis Z, Tumpek J, et al. Pancreatic autoantibodies are associated with reactivity to microbial antibodies, penetrating disease behavior, perianal disease, and extraintestinal manifestations, but not with NOD2/CARD15 or TLR4 genotype in a Hungarian IBD cohort. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2009, 15, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klebl FH, Bataille F, Huy C, Hofstädter F, Schölmerich J, Rogler G. Association of antibodies to exocrine pancreas with subtypes of Crohn's disease. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2005, 17, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Homsak E, Micetić-Turk D, Bozic B. Autoantibodies pANCA, GAB and PAB in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence, characteristics and diagnostic value. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. 2010, 122 (Suppl 2), 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance IC, Hall A, Leong R, Pearce C, Murray K. A comparative study of goblet cell and pancreatic exocine autoantibodies combined with ASCA and pANCA in Chinese and Caucasian patients with IBD. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2005, 11, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggenbuck D, Reinhold D, Wex T, Goihl A, von Arnim U, Malfertheiner P, et al. Autoantibodies to GP2, the major zymogen granule membrane glycoprotein, are new markers in Crohn's disease. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2011, 412, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski L, Teegen B, Probst C, Aulinger-Stöcker K, Sina C, Fellermann K, et al. Autoantibodies against exocrine pancreas in Crohn's disease are directed against two antigens: the glycoproteins CUZD1 and GP2. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2013, 7, 780–790. [Google Scholar]

- Schoepfer AM, Schaffer T, Mueller S, Flogerzi B, Vassella E, Seibold-Schmid B, et al. Phenotypic associations of Crohn's disease with antibodies to flagellins A4-Fla2 and Fla-X, ASCA, p-ANCA, PAB, and NOD2 mutations in a Swiss Cohort. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2009, 15, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goischke EM, Zilly W. [Clinical importance of organ-specific antibodies in ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease]. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie. 1992, 30, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Barthet M, Hastier P, Bernard JP, Bordes G, Frederick J, Allio S, et al. Chronic pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease: true or coincidental association? The American journal of gastroenterology. 1999, 94, 2141–2148.

- Spiess SE, Braun M, Vogelzang RL, Craig RM. Crohn's disease of the duodenum complicated by pancreatitis and common bile duct obstruction. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1992, 87, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Roggenbuck D, Hausdorf G, Martinez-Gamboa L, Reinhold D, Büttner T, Jungblut PR, et al. Identification of GP2, the major zymogen granule membrane glycoprotein, as the autoantigen of pancreatic antibodies in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2009, 58, 1620–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaskos C, Rigopoulou EI, Orfanidou T, Bogdanos DP, Papandreou CN. CUZD1 and anti-CUZD1 antibodies as markers of cancer and inflammatory bowel diseases. Clinical & developmental immunology. 2013, 2013, 968041. [Google Scholar]

- Hase K, Kawano K, Nochi T, Pontes GS, Fukuda S, Ebisawa M, et al. Uptake through glycoprotein 2 of FimH(+) bacteria by M cells initiates mucosal immune response. Nature. 2009, 462, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno H, Hase K. Glycoprotein 2 (GP2): grabbing the FimH bacteria into M cells for mucosal immunity. Gut microbes. 2010, 1, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terahara K, Yoshida M, Igarashi O, Nochi T, Pontes GS, Hase K, et al. Comprehensive gene expression profiling of Peyer's patch M cells, villous M-like cells, and intestinal epithelial cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2008, 180, 7840–7846. [Google Scholar]

- Roggenbuck D, Reinhold D, Schierack P, Bogdanos DP, Conrad K, Laass MW. Crohn's disease specific pancreatic antibodies: clinical and pathophysiological challenges. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2014, 52, 483–494. [Google Scholar]

- Roggenbuck D, Reinhold D, Werner L, Schierack P, Bogdanos DP, Conrad K. Glycoprotein 2 antibodies in Crohn's disease. Advances in clinical chemistry. 2013, 60, 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis P, Romanidou O, Roggenbuck D, Mytilinaiou MG, Al-Sulttan F, Liaskos C, et al. Ileal inflammation may trigger the development of GP2-specific pancreatic autoantibodies in patients with Crohn's disease. Clinical & developmental immunology. 2012, 2012, 640835. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis P, Shums Z, Koutsoumpas AL, Milo J, Papp M, Umemura T, et al. Diagnostic and clinical significance of Crohn's disease-specific anti-MZGP2 pancreatic antibodies by a novel ELISA. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2015, 441, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanos DP, Roggenbuck D, Reinhold D, Wex T, Pavlidis P, von Arnim U, et al. Pancreatic-specific autoantibodies to glycoprotein 2 mirror disease location and behaviour in younger patients with Crohn's disease. BMC gastroenterology. 2012, 12, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Op De Beéck K, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Bossuyt X. Antibodies to GP2, the major zymogen granule membrane glycoprotein, in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2012, 61, 162–164. [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an Integrated Clinical, Molecular and Serological Classification of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005, 19 (Suppl. a), 5A–36A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teegen B, Niemann S, Probst C, Schlumberger W, Stöcker W, Komorowski L. DNA-bound lactoferrin is the major target for antineutrophil perinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies in ulcerative colitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009, 1173, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels MA, Jendrek ST, Korf T, Nitzsche T, Teegen B, Komorowski L, et al. Pancreatic Autoantibodies Against CUZD1 and GP2 Are Associated with Distinct Clinical Phenotypes of Crohn's Disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2015, 21, 2864–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp M, Sipeki N, Tornai T, Altorjay I, Norman GL, Shums Z, et al. Rediscovery of the Anti-Pancreatic Antibodies and Evaluation of their Prognostic Value in a Prospective Clinical Cohort of Crohn's Patients: The Importance of Specific Target Antigens [GP2 and CUZD1]. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2015, 9, 659–668. [Google Scholar]

- Röber N, Noß L, Goihl A, Reinhold D, Jahn J, de Laffolie J, et al. Autoantibodies Against Glycoprotein 2 Isoforms in Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2017, 23, 1624–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang S, Wu Z, Luo J, Ding X, Hu C, Li P, et al. Diagnostic Potential of Zymogen Granule Glycoprotein 2 Antibodies as Serologic Biomarkers in Chinese Patients With Crohn Disease. Medicine. 2015, 94, e1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Luo J, Wu Z, Roggenbuck D, Schierack P, Reinhold D, et al. Antibodies against glycoprotein 2 display diagnostic advantages over ASCA in distinguishing CD from intestinal tuberculosis and intestinal Behçet's disease. Clinical and translational gastroenterology. 2018, 9, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt F, Dirmeier A, Lopez R, Lang S, Kunst C, Roggenbuck D, et al. Serologic Anti-GP2 Antibodies Are Associated with Genetic Polymorphisms, Fibrostenosis, and Need for Surgical Resection in Crohn's Disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2016, 22, 2648–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis P, Komorowski L, Teegen B, Liaskos C, Koutsoumpas AL, Smyk DS, et al. Diagnostic and clinical significance of Crohn's disease-specific pancreatic anti-GP2 and anti-CUZD1 antibodies. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2016, 54, 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings D, Cruise M, Lopez R, Roggenbuck D, Jairath V, Wang Y, et al. Loss of tolerance to glycoprotein 2 isoforms 1 and 4 is associated with Crohn's disease of the pouch. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2018, 48, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Lalkhen AG, McCluskey A. Clinical tests: sensitivity and specificity. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 2008, 8, 221–223. [Google Scholar]

- Power M, Fell G, Wright M. Principles for high-quality, high-value testing. Evidence Based Medicine. 2013, 18, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Li C, Zhao X, Lv C, He Q, Lei S, et al. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies associate with phenotypes and higher risk for surgery in Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2012, 57, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng C, Li W, Li J, Zhang S, Li Y. Diagnostic value of the antiglycoprotein-2 antibody for Crohn's disease: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2017, 7, e014843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiouras K, Grammatikopoulou MG, Theodoridis X, Pagkalidou E, Chatzikyriakou E, Apostolidou AG, et al. Diagnostic and clinical significance of antigen-specific pancreatic antibodies in inflammatory bowel diseases: A meta-analysis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2020, 26, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, Kucharzik T, Fiorino G, Annese V, et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2019, 13, 144–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs G, Sipeki N, Suga B, Tornai T, Fechner K, Norman GL, et al. Significance of serological markers in the disease course of ulcerative colitis in a prospective clinical cohort of patients. PloS One 2018, 13, e0194166. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).