Submitted:

10 October 2023

Posted:

10 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

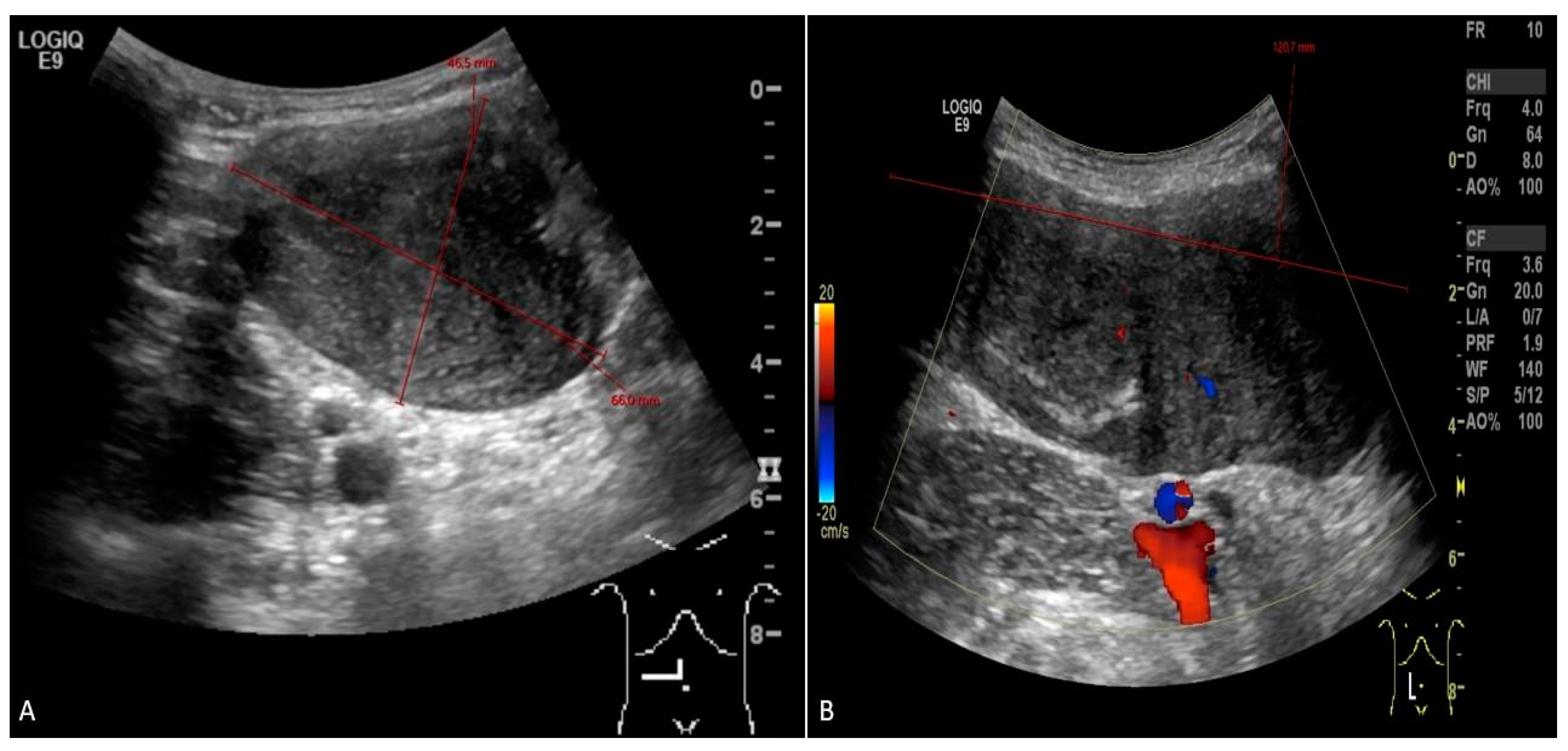

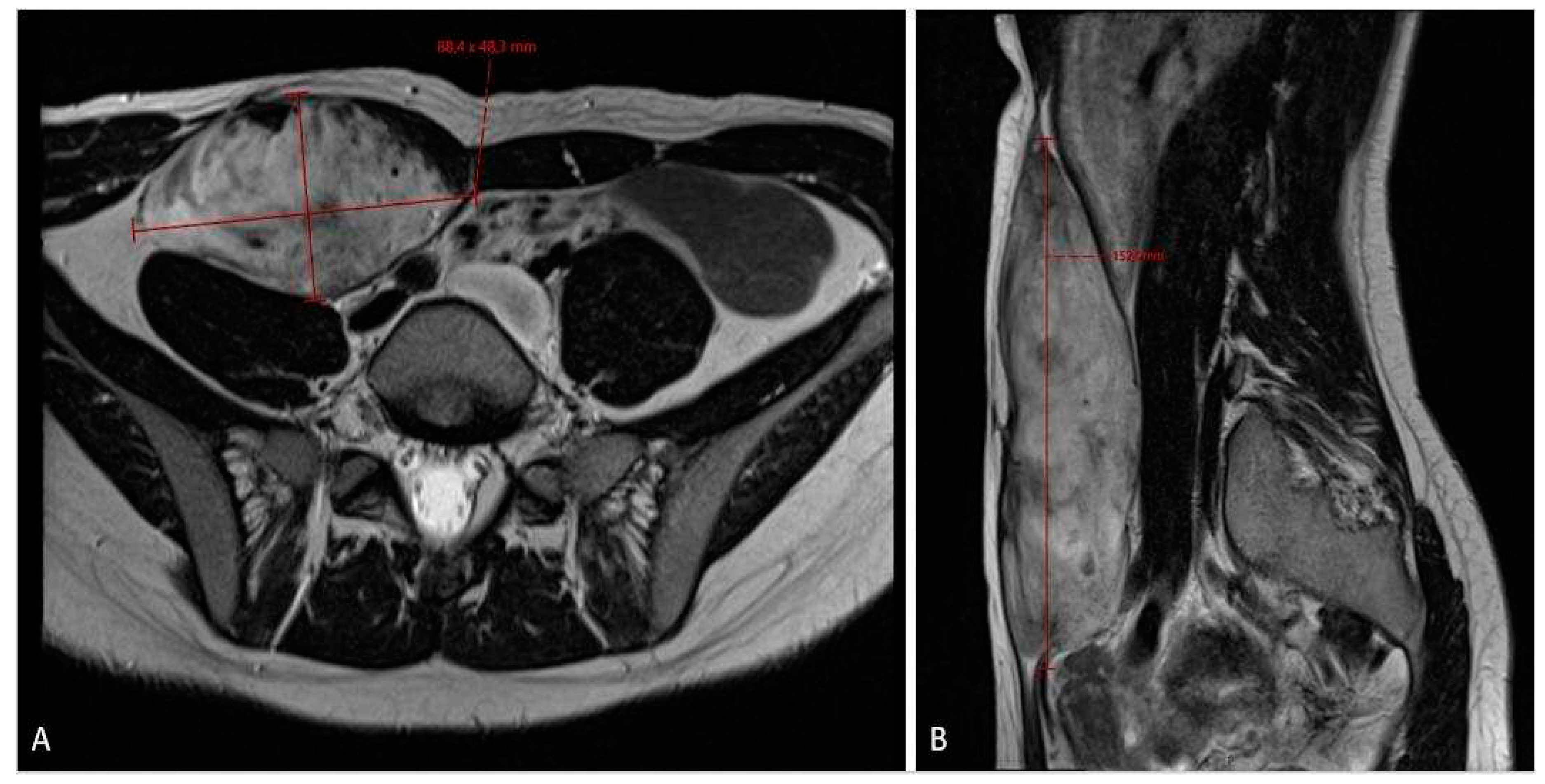

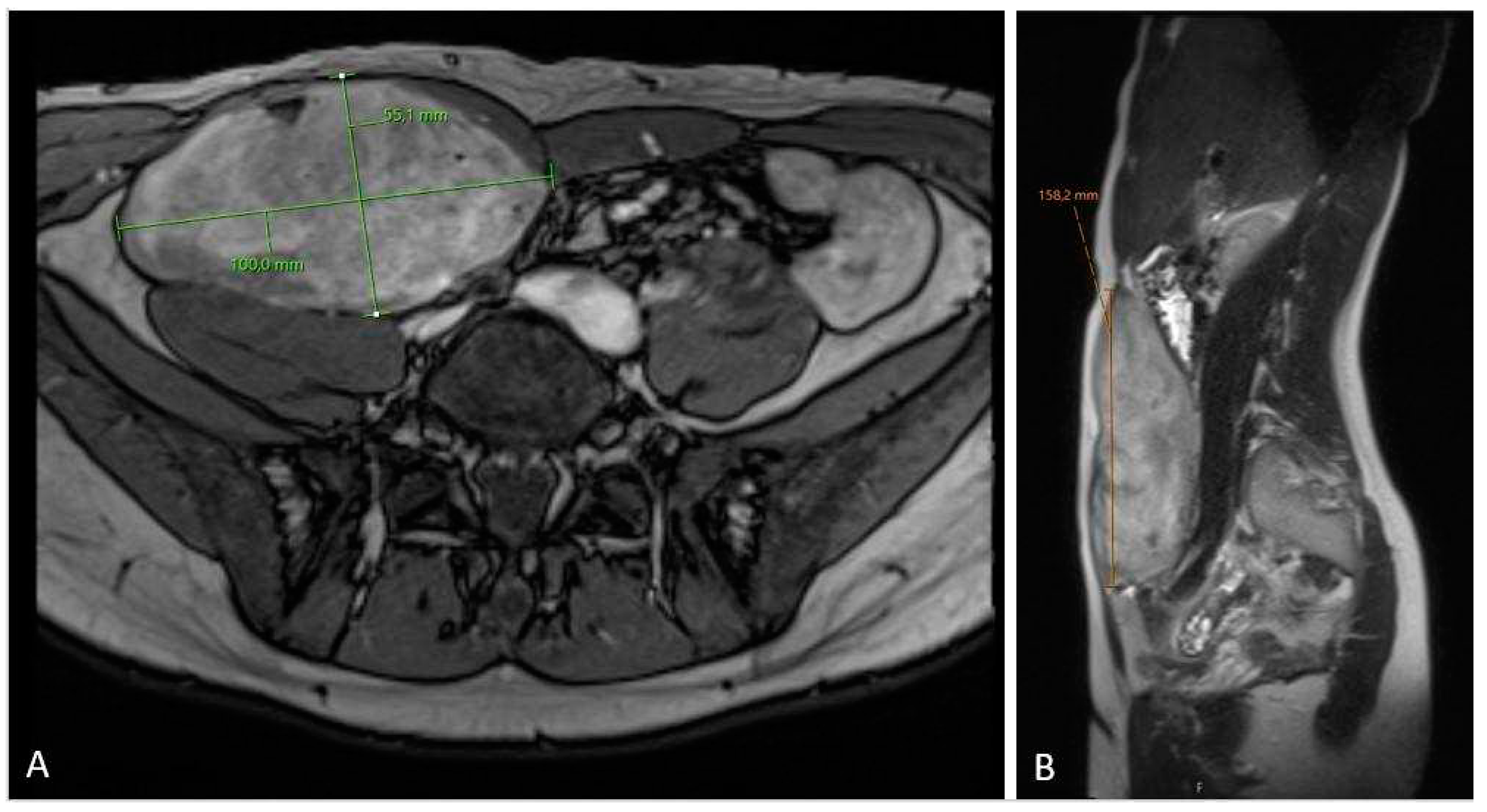

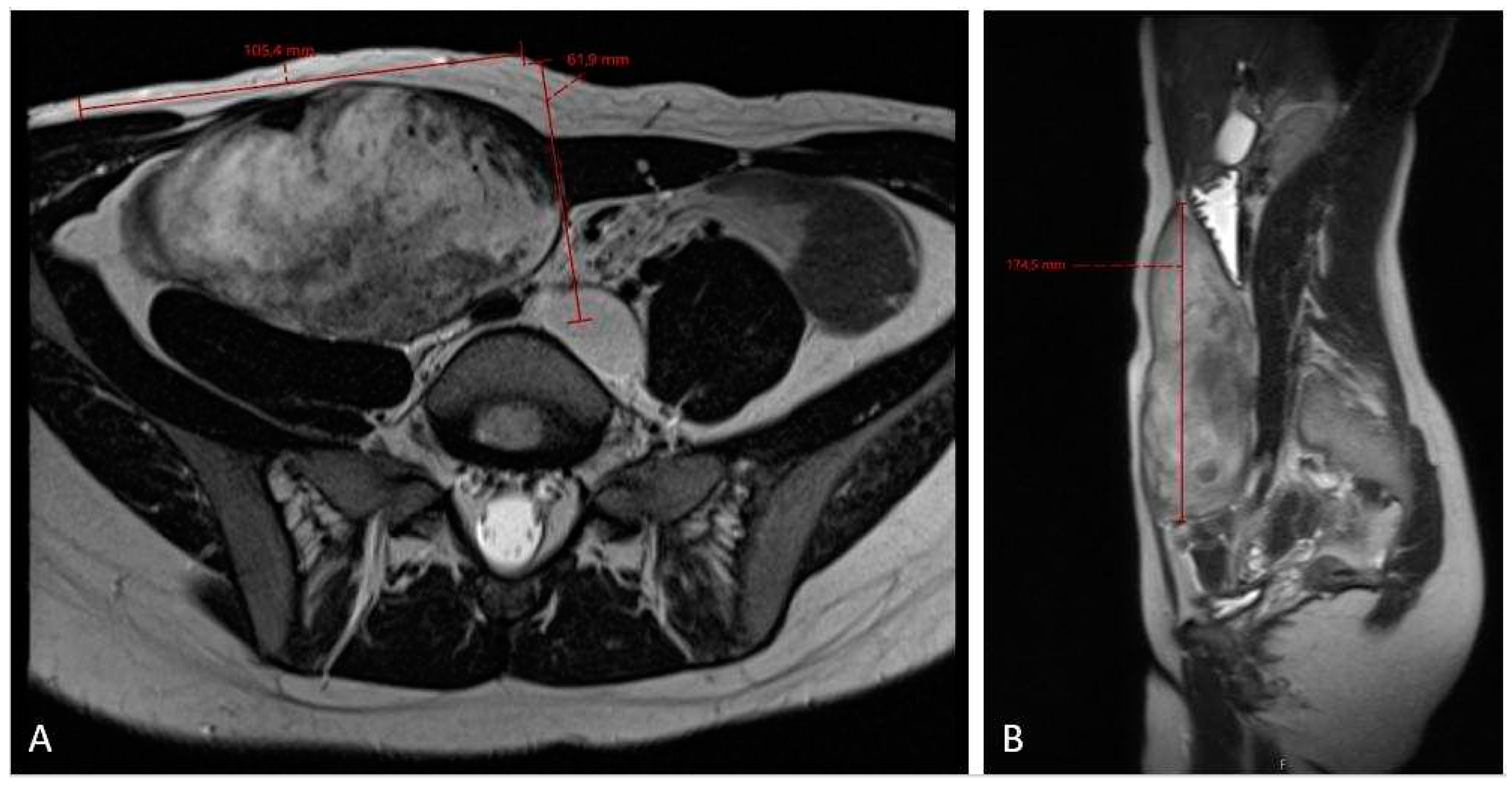

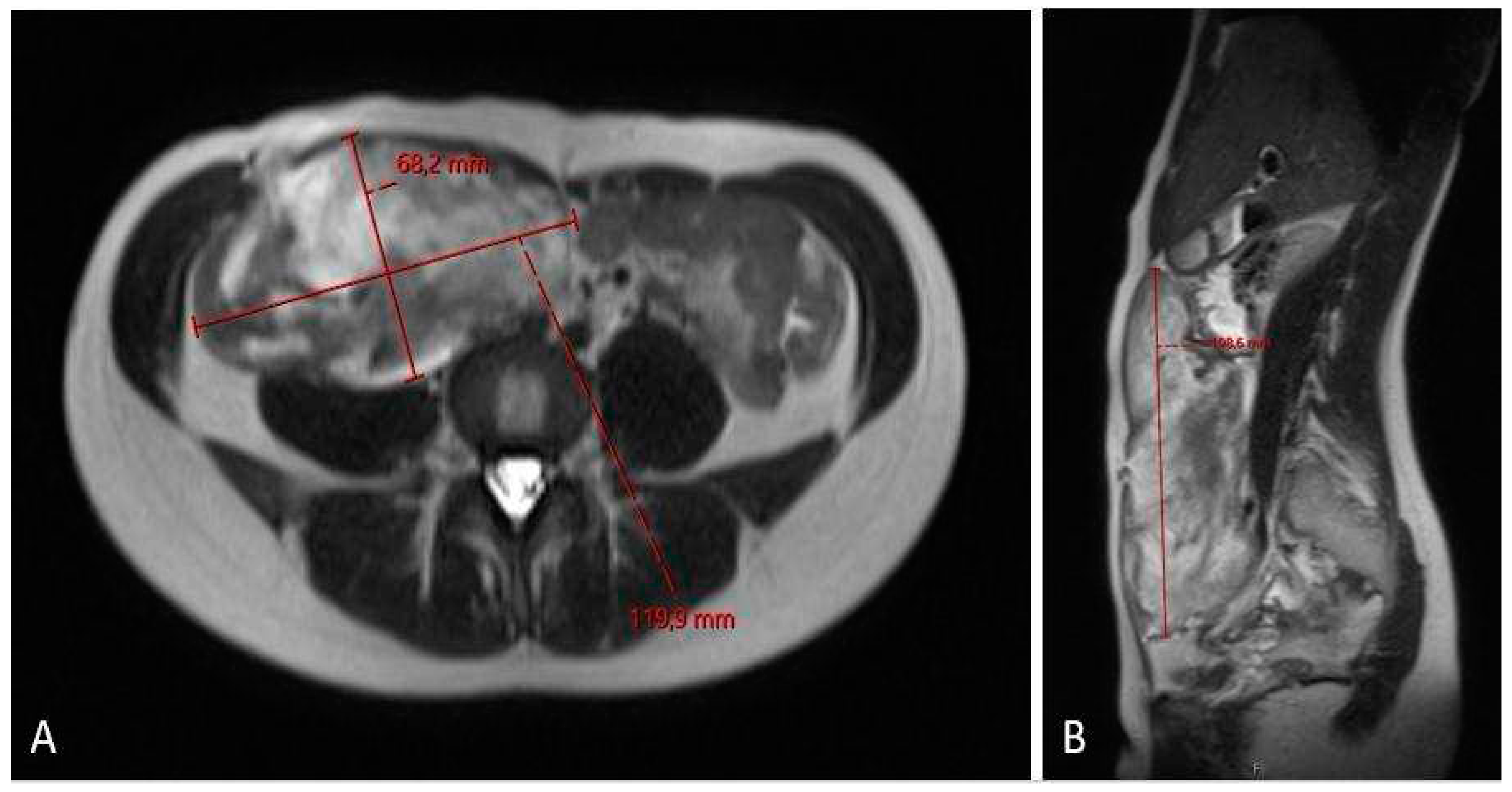

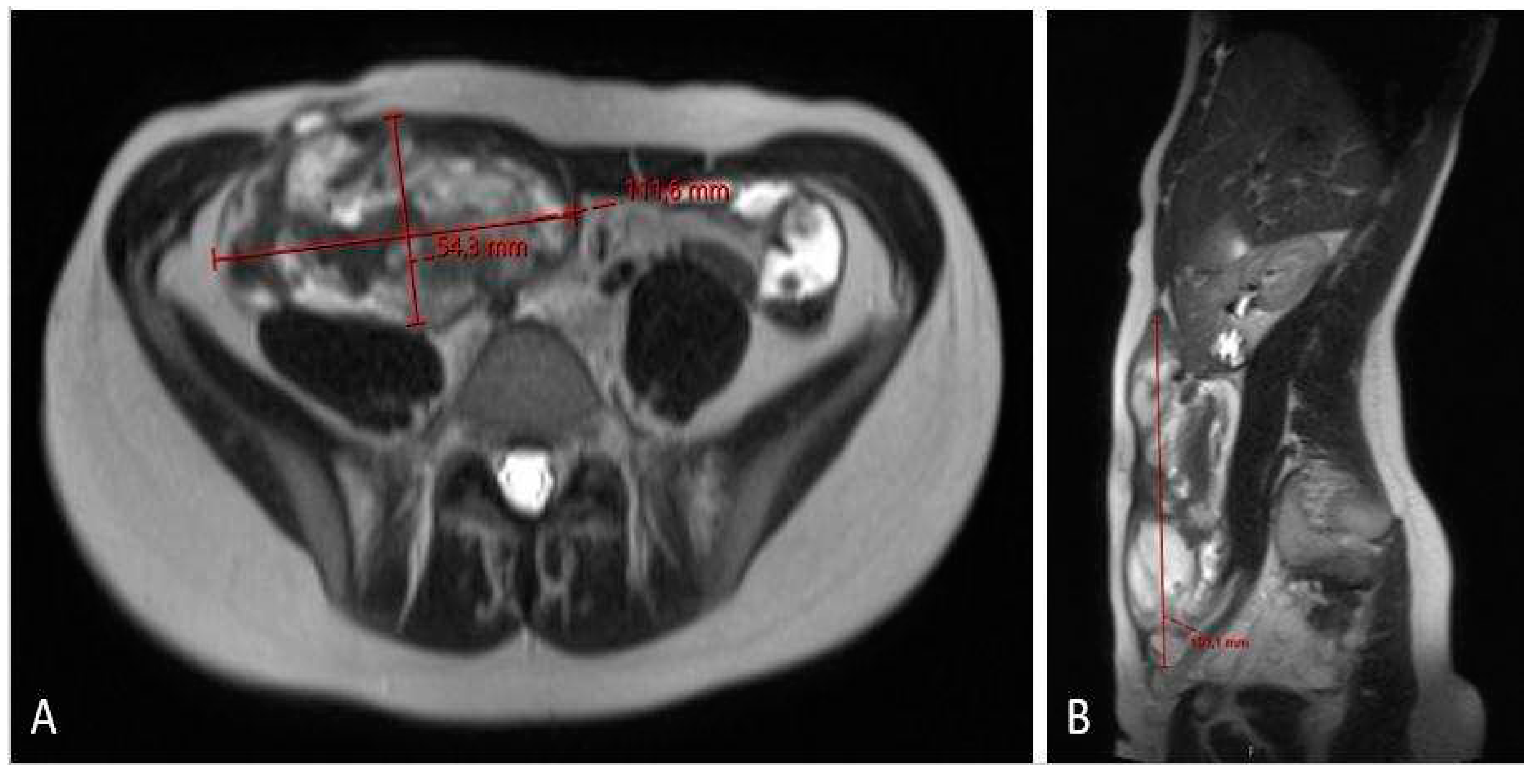

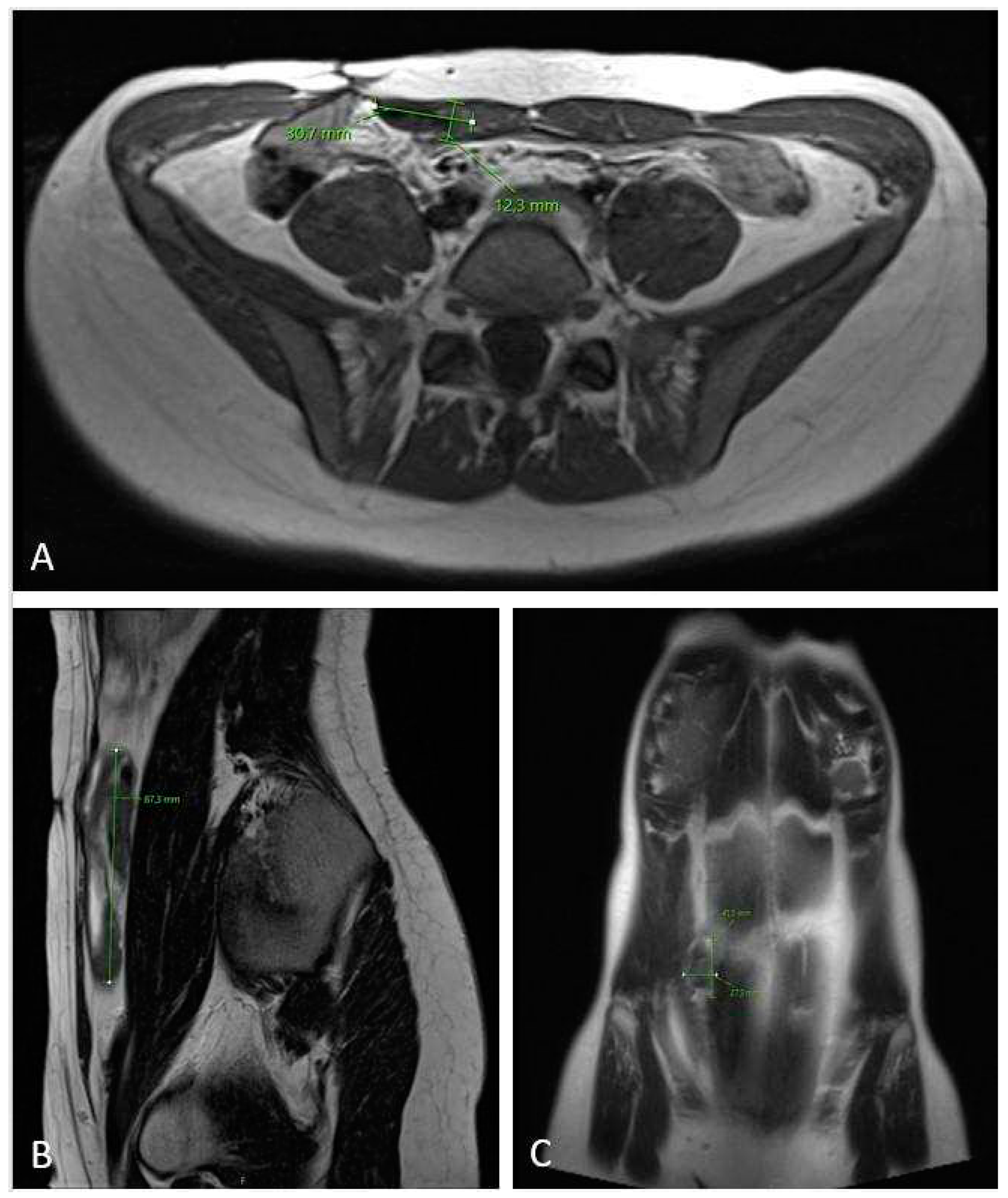

Case report

Discussion

Etiology

Pathogenesis

Conclusion

Disclosure and Contributorship

Funding and financial support

Acknowledgments

Conflict o finterests

References

- Sakorafas GH, Nissotakis C, Peros G. Abdominal desmoid tumors. Surg Oncol. 2007 Aug;16(2):131-42. [CrossRef]

- Hornick JL, Fritchle KJ, Matt van de Rijn. Desmoid fibromatosis. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft tissue and bone tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 3). Available from: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/33.

- Desmoid Tumor Working Group. The management of desmoid tumours: A joint global consensus-based guideline approach for adult and paediatric patients. Eur J Cancer. 2020 Mar;127:96-107. [CrossRef]

- Penel N, Coindre JM, Bonvalot S, Italiano A, Neuville A, Le Cesne A, Terrier P, Ray-Coquard I, Ranchere-Vince D, Robin YM, Isambert N, Ferron G, Duffaud F, Bertucci F, Rios M, Stoeckle E, Le Pechoux C, Guillemet C, Courreges JB, Blay JY. Management of desmoid tumours: A nationwide survey of labelled reference centre networks in France. Eur J Cancer. 2016 May;58:90-6. [CrossRef]

- Reitamo JJ, Häyry P, Nykyri E, Saxén E. The desmoid tumor. I. Incidence, sex-, age- and anatomical distribution in the Finnish population. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982 Jun;77(6):665-73. [CrossRef]

- Anneberg M, Svane HML, Fryzek J, Nicholson G, White JB, Edris B, Smith LM, Hooda N, Petersen MM, Baad-Hansen T, Keller JØ, Jørgensen PH, Pedersen AB. The epidemiology of desmoid tumors in Denmark. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022 Apr;77:102114. [CrossRef]

- Alfentoukh M, Salih A, Hassan ME, Alghamdi O, Alkhawaja KA, Ibrahim MA, Sabir EI. Desmoid Tumor of the Rectus Abdominis with Urinary Bladder Involvement: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Gulf J Oncolog. 2023 Jan;1(41):100-106.

- Mundada AV, Tote D, Zade A. Desmoid tumor of Meckel's diverticulum presenting as intestinal obstruction: A rare case report with literature review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2022 Jul-Sep;18(4):880-884. [CrossRef]

- Minami Y, Matsumoto S, Ae K, Tanizawa T, Hayakawa K, Saito M, Kurosawa N. The Clinical Features of Multicentric Extra-abdominal Desmoid Tumors. Cancer Diagn Progn. 2021 Jul 3;1(4):339-343. [CrossRef]

- Tzur R, Silberstein E, Krieger Y, Shoham Y, Rafaeli Y, Bogdanov-Berezovsky A. Desmoid Tumor and Silicone Breast Implant Surgery: Is There Really a Connection? A Literature Review. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018 Feb;42(1):59-63. [CrossRef]

- Müller, J. Müller J. Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen. Hölscher, Coblenz, 1833–1838.

- https://www.wikidoc.org/index.php/Desmoid_tumor_historical_perspective.

- Arima K, Komohara Y, Uchihara T, Yamashita K, Uemura S, Hanada N, Baba H. A Case of Mesenteric Desmoid Tumor Causing Bowel Obstruction After Laparoscopic Surgery. Anticancer Res. 2022 Jan;42(1):381-384. [CrossRef]

- Takada M, Okuyama T, Yoshioka R, Noie T, Takeshita E, Sameshima S, Oya M. A case with mesenteric desmoid tumor after laparoscopic resection of stage I sigmoid colon cancer. Surg Case Rep. 2019 Feb 28;5(1):38. [CrossRef]

- Fukuhara S, Yoshimitsu M, Yano T, Chogahara I, Yamasaki R, Ebara S, Okajima M. Mesenteric desmoid tumor after robot-assisted laparoscopic cystectomy with bladder replacement: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2022 Feb 15;2022(2):rjab529. [CrossRef]

- Wanjeri JK, Opeya CJ. A massive abdominal wall desmoid tumor occurring in a laparotomy scar: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2011 Mar 22;9:35. [CrossRef]

- Howard JH, Pollock RE. Intra-Abdominal and Abdominal Wall Desmoid Fibromatosis. Oncol Ther. 2016;4(1):57-72. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ortega DY, Martín-Tellez KS, Cuellar-Hubbe M, Martínez-Said H, Álvarez-Cano A, Brener-Chaoul M, Alegría-Baños JA, Martínez-Tlahuel JL. Desmoid-Type Fibromatosis. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Jul 9;12(7):1851. [CrossRef]

- Simonetti I, Bruno F, Fusco R, Cutolo C, Setola SV, Patrone R, Masciocchi C, Palumbo P, Arrigoni F, Picone C, Belli A, Grassi R, Grassi F, Barile A, Izzo F, Petrillo A, Granata V. Multimodality Imaging Assessment of Desmoid Tumors: The Great Mime in the Era of Multidisciplinary Teams. J Pers Med. 2022 Jul 16;12(7):1153. [CrossRef]

- Schut AW, Lidington E, Timbergen MJM, Younger E, van der Graaf WTA, van Houdt WJ, Bonenkamp JJ, Jones RL, Grünhagen DJ, Sleijfer S, Verhoef C, Gennatas S, Husson O. Unraveling Desmoid-Type Fibromatosis-Specific Health-Related Quality of Life: Who Is at Risk for Poor Outcomes. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jun 16;14(12):2979. [CrossRef]

- Melis M, Zager JS, Sondak VK. Multimodality management of desmoid tumors: how important is a negative surgical margin? J Surg Oncol. 2008 Dec 15;98(8):594-602. [CrossRef]

- Napolitano A, Mazzocca A, Spalato Ceruso M, Minelli A, Baldo F, Badalamenti G, Silletta M, Santini D, Tonini G, Incorvaia L, Vincenzi B. Recent Advances in Desmoid Tumor Therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Aug 1;12(8):2135. [CrossRef]

- Dehner LP, Askin FB. Tumors of fibrous tissue origin in childhood. A clinicopathologic study of cutaneous and soft tissue neoplasms in 66 children. Cancer. 1976 Aug;38(2):888-900. [CrossRef]

- Batsakis JG, Raslan W. Extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994 Apr;103(4 Pt 1):331-4. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis MH, Casparie M, Mathus-Vliegen LM, Dekkers OM, Hogendoorn PC, Vasen HF. A nation-wide study comparing sporadic and familial adenomatous polyposis-related desmoid-type fibromatoses. Int J Cancer. 2011 Jul 1;129(1):256-61. [CrossRef]

- Tayeb Tayeb C, Parc Y, Andre T, Lopez-Trabada Ataz D. Familial adenomatous polyposis, desmoid tumors and Gardner syndrome. Bull Cancer. 2020 Mar;107(3):352-358. [CrossRef]

- Saito Y, Hinoi T, Ueno H, Kobayashi H, Konishi T, Ishida F, Yamaguchi T, Inoue Y, Kanemitsu Y, Tomita N, Matsubara N, Komori K, Kotake K, Nagasaka T, Hasegawa H, Koyama M, Ohdan H, Watanabe T, Sugihara K, Ishida H. Risk Factors for the Development of Desmoid Tumor After Colectomy in Patients with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis: Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study in Japan. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Aug;23(Suppl 4):559-565. [CrossRef]

- Kasper B, Baumgarten C, Garcia J, Bonvalot S, Haas R, Haller F, Hohenberger P, Penel N, Messiou C, van der Graaf WT, Gronchi A; Desmoid Working Group. An update on the management of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis: a European Consensus Initiative between Sarcoma PAtients EuroNet (SPAEN) and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (STBSG). Ann Oncol. 2017 Oct 1;28(10):2399-2408. [CrossRef]

- Debaudringhien M, Blay JY, Bimbai AM, Bonvalot S, Italiano A, Rousset-Jablonski C, Corradini N, Piperno-Neumann S, Chevreau C, Kurtz JE, Guillemet C, Bompas E, Collard O, Salas S, Le Cesne A, Orbach D, Thery J, Le Deley MC, Mir O, Penel N. Association between recent pregnancy or hormonal contraceptive exposure and outcome of desmoid-type fibromatosis. ESMO Open. 2022 Oct;7(5):100578. [CrossRef]

- Gounder MM, Thomas DM, Tap WD. Locally Aggressive Connective Tissue Tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jan 10;36(2):202-209. [CrossRef]

- Slowik V, Attard T, Dai H, Shah R, Septer S. Desmoid tumors complicating Familial Adenomatous Polyposis: a meta-analysis mutation spectrum of affected individuals. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015 Jul 16;15:84. [CrossRef]

- Colombo C, Foo WC, Whiting D, Young ED, Lusby K, Pollock RE, Lazar AJ, Lev D. FAP-related desmoid tumors: a series of 44 patients evaluated in a cancer referral center. Histol Histopathol. 2012 May;27(5):641-9. [CrossRef]

- Amary MF, Pauwels P, Meulemans E, Roemen GM, Islam L, Idowu B, Bousdras K, Diss TC, O'Donnell P, Flanagan AM. Detection of beta-catenin mutations in paraffin-embedded sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis by mutation-specific restriction enzyme digestion (MSRED): an ancillary diagnostic tool. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007 Sep;31(9):1299-309. [CrossRef]

- Lazar AJ, Tuvin D, Hajibashi S, Habeeb S, Bolshakov S, Mayordomo-Aranda E, Warneke CL, Lopez-Terrada D, Pollock RE, Lev D. Specific mutations in the beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1) correlate with local recurrence in sporadic desmoid tumors. Am J Pathol. 2008 Nov;173(5):1518-27. [CrossRef]

- Colombo C, Belfiore A, Paielli N, De Cecco L, Canevari S, Laurini E, Fermeglia M, Pricl S, Verderio P, Bottelli S, Fiore M, Stacchiotti S, Palassini E, Gronchi A, Pilotti S, Perrone F. β-Catenin in desmoid-type fibromatosis: deep insights into the role of T41A and S45F mutations on protein structure and gene expression. Mol Oncol. 2017 Nov;11(11):1495-1507. [CrossRef]

- Dômont J, Salas S, Lacroix L, Brouste V, Saulnier P, Terrier P, Ranchère D, Neuville A, Leroux A, Guillou L, Sciot R, Collin F, Dufresne A, Blay JY, Le Cesne A, Coindre JM, Bonvalot S, Bénard J. High frequency of beta-catenin heterozygous mutations in extra-abdominal fibromatosis: a potential molecular tool for disease management. Br J Cancer. 2010 Mar 16;102(6):1032-6. [CrossRef]

- Crago AM, Chmielecki J, Rosenberg M, O'Connor R, Byrne C, Wilder FG, Thorn K, Agius P, Kuk D, Socci ND, Qin LX, Meyerson M, Hameed M, Singer S. Near universal detection of alterations in CTNNB1 and Wnt pathway regulators in desmoid-type fibromatosis by whole-exome sequencing and genomic analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2015 Oct;54(10):606-15. [CrossRef]

- Penel N, Chibon F, Salas S. Adult desmoid tumors: biology, management and ongoing trials. Curr Opin Oncol. 2017 Jul;29(4):268-274. [CrossRef]

- Giarola M, Stagi L, Presciuttini S, Mondini P, Radice MT, Sala P, Pierotti MA, Bertario L, Radice P. Screening for mutations of the APC gene in 66 Italian familial adenomatous polyposis patients: evidence for phenotypic differences in cases with and without identified mutation. Hum Mutat. 1999;13(2):116-23. [CrossRef]

- Bertario L, Russo A, Sala P, Eboli M, Giarola M, D'amico F, Gismondi V, Varesco L, Pierotti MA, Radice P; Hereditary Colorectal Tumours Registry. Genotype and phenotype factors as determinants of desmoid tumors in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Cancer. 2001 Mar 20;95(2):102-7. [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz AK, Giardiello FM, Petersen GM, Krush AJ, Offerhaus GJ, Booker SV, Kerr MC, Hamilton SR. Desmoid tumours in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 1994 Mar;35(3):377-81. [CrossRef]

- Lips DJ, Barker N, Clevers H, Hennipman A. The role of APC and beta-catenin in the aetiology of aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumors). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009 Jan;35(1):3-10. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis MH, De Vos Tot Nederveen Cappel W, Botma A, Nagengast FM, Kleibeuker JH, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Dekker E, Dees J, Wijnen J, Vasen HF. Desmoid tumors in a dutch cohort of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Feb;6(2):215-9. [CrossRef]

- Järvinen HJ, Peltomäki P. The complex genotype-phenotype relationship in familial adenomatous polyposis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004 Jan;16(1):5-8. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis MH, Vasen HF. Correlations between mutation site in APC and phenotype of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): a review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007 Feb;61(2):153-61. [CrossRef]

- Wang WL, Nero C, Pappo A, Lev D, Lazar AJ, López-Terrada D. CTNNB1 genotyping and APC screening in pediatric desmoid tumors: a proposed algorithm. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012 Sep-Oct;15(5):361-7. [CrossRef]

- Barker, N. Barker N. The canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;468:5-15. [CrossRef]

- Brener-Chaoul M, Cervantes-Gutiérrez Ó, Padilla-Longoria R, Martín-Téllez KS. Desmoid tumors: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Gac Med Mex. 2020;156(5):439-445. [CrossRef]

- Lazar AJ, Hajibashi S, Lev D. Desmoid tumor: from surgical extirpation to molecular dissection. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009 Jul;21(4):352-9. [CrossRef]

- Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell. 2017 Jun 1;169(6):985-999. [CrossRef]

- Kotiligam D, Lazar AJ, Pollock RE, Lev D. Desmoid tumor: a disease opportune for molecular insights. Histol Histopathol. 2008 Jan;23(1):117-26. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Wang CY. TBL1-TBLR1 and beta-catenin recruit each other to Wnt target-gene promoter for transcription activation and oncogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008 Feb;10(2):160-9. [CrossRef]

- Angers S, Moon RT. Proximal events in Wnt signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Jul;10(7):468-77. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhou Z, Shu G, Yin G. Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Jan 3;7(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Owens CL, Sharma R, Ali SZ. Deep fibromatosis (desmoid tumor): cytopathologic characteristics, clinicoradiologic features, and immunohistochemical findings on fine-needle aspiration. Cancer. 2007 Jun 25;111(3):166-72. [CrossRef]

- Devata S, Chugh R. Desmoid tumors: a comprehensive review of the evolving biology, unpredictable behavior, and myriad of management options. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013 Oct;27(5):989-1005. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sulaiman N, Mohd Dali F, Mohd Hussain MSB, Ramli R. Abdominal wall desmoid tumour in pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2022 Jun 16;15(6):e249966. [CrossRef]

- Desurmont T, Lefèvre JH, Shields C, Colas C, Tiret E, Parc Y. Desmoid tumour in familial adenomatous polyposis patients: responses to treatments. Fam Cancer. 2015 Mar;14(1):31-9. [CrossRef]

- Salas S, Dufresne A, Bui B, Blay JY, Terrier P, Ranchere-Vince D, Bonvalot S, Stoeckle E, Guillou L, Le Cesne A, Oberlin O, Brouste V, Coindre JM. Prognostic factors influencing progression-free survival determined from a series of sporadic desmoid tumors: a wait-and-see policy according to tumor presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Sep 10;29(26):3553-8. [CrossRef]

- Fiore M, Coppola S, Cannell AJ, Colombo C, Bertagnolli MM, George S, Le Cesne A, Gladdy RA, Casali PG, Swallow CJ, Gronchi A, Bonvalot S, Raut CP. Desmoid-type fibromatosis and pregnancy: a multi-institutional analysis of recurrence and obstetric risk. Ann Surg. 2014 May;259(5):973-8. [CrossRef]

- Sueishi T, Arizono T, Nishida K, Hamada T, Inokuchi A. A Case of Spontaneous Regression of Recurrent Desmoid Tumor Originating From the Internal Obturator Muscle After Delivery. World J Oncol. 2016 Aug;7(4):75-80. [CrossRef]

- Crago AM, Denton B, Salas S, Dufresne A, Mezhir JJ, Hameed M, Gonen M, Singer S, Brennan MF. A prognostic nomogram for prediction of recurrence in desmoid fibromatosis. Ann Surg. 2013 Aug;258(2):347-53. [CrossRef]

- Lev D, Kotilingam D, Wei C, Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Pisters PW, Lazar AA, Patel SR, Benjamin RS, Pollock RE. Optimizing treatment of desmoid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007 May 1;25(13):1785-91. [CrossRef]

- Bo N, Wang D, Wu B, Chen L, Ruixue Ma. Analysis of β-catenin expression and exon 3 mutations in pediatric sporadic aggressive fibromatosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012 May-Jun;15(3):173-8. [CrossRef]

- Colombo C, Miceli R, Lazar AJ, Perrone F, Pollock RE, Le Cesne A, Hartgrink HH, Cleton-Jansen AM, Domont J, Bovée JV, Bonvalot S, Lev D, Gronchi A. CTNNB1 45F mutation is a molecular prognosticator of increased postoperative primary desmoid tumor recurrence: an independent, multicenter validation study. Cancer. 2013 Oct 15;119(20):3696-702. [CrossRef]

- Penel N, Bonvalot S, Bimbai AM, Meurgey A, Le Loarer F, Salas S, Piperno-Neumann S, Chevreau C, Boudou-Rouquette P, Dubray-Longeras P, Kurtz JE, Guillemet C, Bompas E, Italiano A, Le Cesne A, Orbach D, Thery J, Le Deley MC, Blay JY, Mir O. Lack of Prognostic Value of CTNNB1 Mutation Profile in Desmoid-Type Fibromatosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2022 Sep 15;28(18):4105-4111. [CrossRef]

- Moore D, Burns L, Creavin B, Ryan E, Conlon K, Kelly ME, Kavanagh D. Surgical management of abdominal desmoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ir J Med Sci. 2023 Apr;192(2):549-560. [CrossRef]

- Janssen ML, van Broekhoven DL, Cates JM, Bramer WM, Nuyttens JJ, Gronchi A, Salas S, Bonvalot S, Grünhagen DJ, Verhoef C. Meta-analysis of the influence of surgical margin and adjuvant radiotherapy on local recurrence after resection of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis. Br J Surg. 2017 Mar;104(4):347-357. [CrossRef]

- de Bree E, Keus R, Melissas J, Tsiftsis D, van Coevorden F. Desmoid tumors: need for an individualized approach. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009 Apr;9(4):525-35. [CrossRef]

- Keus RB, Nout RA, Blay JY, de Jong JM, Hennig I, Saran F, Hartmann JT, Sunyach MP, Gwyther SJ, Ouali M, Kirkpatrick A, Poortmans PM, Hogendoorn PCW, van der Graaf WTA. Results of a phase II pilot study of moderate dose radiotherapy for inoperable desmoid-type fibromatosis--an EORTC STBSG and ROG study (EORTC 62991-22998). Ann Oncol. 2013 Oct;24(10):2672-2676. [CrossRef]

- Gronchi A, Colombo C, Le Péchoux C, Dei Tos AP, Le Cesne A, Marrari A, Penel N, Grignani G, Blay JY, Casali PG, Stoeckle E, Gherlinzoni F, Meeus P, Mussi C, Gouin F, Duffaud F, Fiore M, Bonvalot S; ISG and FSG. Sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis: a stepwise approach to a non-metastasising neoplasm--a position paper from the Italian and the French Sarcoma Group. Ann Oncol. 2014 Mar;25(3):578-583. [CrossRef]

- Zhong X, Hu X, Zhao P, Wang Y, Fang XF, Shen J, Shen H, Yuan Y. The efficacy of low-power cumulative high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for recurrent desmoid tumor. Cancer Med. 2022 May;11(10):2079-2084. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz JJ, Schmit GD, Atwell TD, Callstrom MR, Kurup AN, Weisbrod AJ, Morris JM. Percutaneous Cryoablation of Extraabdominal Desmoid Tumors: A 10-Year Experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016 Jul;207(1):190-5. [CrossRef]

- Vora BMK, Munk PL, Somasundaram N, Ouellette HA, Mallinson PI, Sheikh A, Abdul Kadir H, Tan TJ, Yan YY. Cryotherapy in extra-abdominal desmoid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021 Dec 23;16(12):e0261657. [CrossRef]

- Mignemi NA, Itani DM, Fasig JH, Keedy VL, Hande KR, Whited BW, Homlar KC, Correa H, Coffin CM, Black JO, Yi Y, Halpern JL, Holt GE, Schwartz HS, Schoenecker JG, Cates JM. Signal transduction pathway analysis in desmoid-type fibromatosis: transforming growth factor-β, COX2 and sex steroid receptors. Cancer Sci. 2012 Dec;103(12):2173-80. [CrossRef]

- McLean TD, Duchi S, Di Bella C. Molecular Pathogenesis of Sporadic Desmoid Tumours and Its Implications for Novel Therapies: A Systematised Narrative Review. Target Oncol. 2022 May;17(3):223-252. [CrossRef]

- Ohashi T, Shigematsu N, Kameyama K, Kubo A. Tamoxifen for recurrent desmoid tumor of the chest wall. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006 Apr;11(2):150-2. [CrossRef]

- Fiore M, Colombo C, Radaelli S, Callegaro D, Palassini E, Barisella M, Morosi C, Baldi GG, Stacchiotti S, Casali PG, Gronchi A. Hormonal manipulation with toremifene in sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis. Eur J Cancer. 2015 Dec;51(18):2800-7. [CrossRef]

- Sportiello DJ, Hoogerland DL. A recurrent pelvic desmoid tumor successfully treated with tamoxifen. Cancer. 1991 Mar 1;67(5):1443-6. [CrossRef]

- Janinis J, Patriki M, Vini L, Aravantinos G, Whelan JS. The pharmacological treatment of aggressive fibromatosis: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2003 Feb;14(2):181-90. [CrossRef]

- Garbay D, Le Cesne A, Penel N, Chevreau C, Marec-Berard P, Blay JY, Debled M, Isambert N, Thyss A, Bompas E, Collard O, Salas S, Coindre JM, Bui B, Italiano A. Chemotherapy in patients with desmoid tumors: a study from the French Sarcoma Group (FSG). Ann Oncol. 2012 Jan;23(1):182-186. [CrossRef]

- Constantinidou A, Jones RL, Scurr M, Al-Muderis O, Judson I. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, an effective, well-tolerated treatment for refractory aggressive fibromatosis. Eur J Cancer. 2009 Nov;45(17):2930-4. [CrossRef]

- Palassini E, Frezza AM, Mariani L, Lalli L, Colombo C, Fiore M, Messina A, Casale A, Morosi C, Collini P, Stacchiotti S, Casali PG, Gronchi A. Long-term Efficacy of Methotrexate Plus Vinblastine/Vinorelbine in a Large Series of Patients Affected by Desmoid-Type Fibromatosis. Cancer J. 2017 Mar/Apr;23(2):86-91. [CrossRef]

- Sparber-Sauer M, Orbach D, Navid F, Hettmer S, Skapek S, Corradini N, Casanova M, Weiss A, Schwab M, Ferrari A. Rationale for the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of paediatric desmoid-type fibromatosis. Br J Cancer. 2021 May;124(10):1637-1646. [CrossRef]

- Gounder MM, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, Ravi V, Attia S, Deshpande HA, Gupta AA, Milhem MM, Conry RM, Movva S, Pishvaian MJ, Riedel RF, Sabagh T, Tap WD, Horvat N, Basch E, Schwartz LH, Maki RG, Agaram NP, Lefkowitz RA, Mazaheri Y, Yamashita R, Wright JJ, Dueck AC, Schwartz GK. Sorafenib for Advanced and Refractory Desmoid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 20;379(25):2417-2428. [CrossRef]

- Zhou MY, Bui NQ, Charville GW, Ghanouni P, Ganjoo KN. Current management and recent progress in desmoid tumors. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2022;31:100562. [CrossRef]

- Federman, N. Federman N. Molecular pathogenesis of desmoid tumor and the role of γ-secretase inhibition. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2022 Sep 6;6(1):62. [CrossRef]

- Braggio DA, Costas C de Faria F, Koller D, Jin F, Zewdu A, Lopez G, Batte K, Casadei L, Welliver M, Horrigan SK, Han R, Larson JL, Strohecker AM, Pollock RE. Preclinical efficacy of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway inhibitor BC2059 for the treatment of desmoid tumors. PLoS One. 2022 Oct 14;17(10):e0276047. [CrossRef]

- Siozopoulou V, Marcq E, Jacobs J, Zwaenepoel K, Hermans C, Brauns J, Pauwels S, Huysentruyt C, Lammens M, Somville J, Smits E, Pauwels P. Desmoid tumors display a strong immune infiltration at the tumor margins and no PD-L1-driven immune suppression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019 Oct;68(10):1573-1583. [CrossRef]

- Weiss AR, Dry S, Maygar C, Cutler A, Lary CW, Khoo C, Fergione JE, Hounchell MM, Glick K, Browning M, Choo SH, Hawkins DS, Lagmay J, Manalang M, Skapek SX, Weigel B, Verwys S, Federman N. A pilot study evaluating the use of sirolimus in children and young adults with desmoid-type fibromatosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023 Jun 7:e30466. [CrossRef]

- Gounder M, Ratan R, Alcindor T, Schöffski P, van der Graaf WT, Wilky BA, Riedel RF, Lim A, Smith LM, Moody S, Attia S, Chawla S, D'Amato G, Federman N, Merriam P, Van Tine BA, Vincenzi B, Benson C, Bui NQ, Chugh R, Tinoco G, Charlson J, Dileo P, Hartner L, Lapeire L, Mazzeo F, Palmerini E, Reichardt P, Stacchiotti S, Bailey HH, Burgess MA, Cote GM, Davis LE, Deshpande H, Gelderblom H, Grignani G, Loggers E, Philip T, Pressey JG, Kummar S, Kasper B. Nirogacestat, a γ-Secretase Inhibitor for Desmoid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2023 Mar 9;388(10):898-912. [CrossRef]

- Marsh-Armstrong B, Veerapong J, Taddonio M, Boles S, Sicklick JK, Binder P. Pregnancy-associated large pelvic desmoid tumor: A case report of fetal-protective strategies and fertility preservation. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2021 Dec 14;39:100901. [CrossRef]

- Jin L, Tan Y, Su Z, Huang S, Pokhrel S, Shi H, Chen Y. Gardner syndrome with giant abdominal desmoid tumor during pregnancy: a case report. BMC Surg. 2020 Nov 12;20(1):282. [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Zertuche JT, Cardona-Huerta S, Juárez-García ML, Valdés-Flores E, Muñoz-Maldonado GE. Case report: Rapidly growing abdominal wall giant desmoid tumour during pregnancy. Cir Cir. 2017 Jul-Aug;85(4):339-343. [CrossRef]

- Hanna D, Magarakis M, Twaddell WS, Alexander HR, Kesmodel SB. Rapid progression of a pregnancy-associated intra-abdominal desmoid tumor in the post-partum period: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;29:30-33. [CrossRef]

- Awwad J, Hammoud N, Farra C, Fares F, Abi Saad G, Ghazeeri G. Abdominal Wall Desmoid during Pregnancy: Diagnostic Challenges. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:350894. [CrossRef]

- Choi SH, Lee JH, Seo BF, Kim SW, Rhie JW, Ahn ST. Desmoid tumor of the rectus abdominis muscle in a postpartum patient. Arch Plast Surg. 2012 Jul;39(4):439-41. [CrossRef]

- Durkin AJ, Korkolis DP, Al-Saif O, Zervos EE. Full-term gestation and transvaginal delivery after wide resection of an abdominal desmoid tumor during pregnancy. J Surg Oncol. 2005 Feb 1;89(2):86-90. [CrossRef]

- Michopoulou A, Germanos S, Kanakopoulos D, Milonas A, Orfanos N, Spyratou C, Markidis P. Management of a large abdominal wall desmoid tumor during pregnancy. Case report. Ann Ital Chir. 2010 Mar-Apr;81(2):153-6. PMID: 20726395.

- Viriyaroj V, Yingsakmongkol N, Pasukdee P, Rermluk N. A large abdominal desmoid tumor associated with pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009 Jun;92 Suppl 3:S72-5. PMID: 19702071.

- Gurluler E, Gures N, Citil I, Kemik O, Berber I, Sumer A, Gurkan A. Desmoid tumor in puerperium period: a case report. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2014 Mar 16;7:29-32. [CrossRef]

- De Cian F, Delay E, Rudigoz RC, Ranchère D, Rivoire M. Desmoid tumor arising in a cesarean section scar during pregnancy: monitoring and management. Gynecol Oncol. 1999 Oct;75(1):145-8. [CrossRef]

- Cates, JM. Cates JM. Pregnancy does not increase the local recurrence rate after surgical resection of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jun;20(3):617-22. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).