1. Introduction

The population dynamics and behaviours of shark species have remained enigmatic due to the inherent challenges of investigating highly mobile marine life [

1]. Nevertheless, understanding their movement is a fundamental and intricate aspect of their biology eg. [

2,

3]. In this context, the blacktip reef shark (

Carcharhinus melanopterus) emerges as a compelling subject of study [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Sharks play pivotal functional roles within coral reef ecosystems. Their presence influences prey-predator dynamics and contributes to the overall health and resilience of these underwater communities [

8]. Investigating the spatial ecology of reef shark populations not only contributes essential data for effective conservation planning [

3] but also works to unravel the intricate web of ecological relationships within these marine systems [

2,

7].

Quantifying the spatial and temporal movement patterns of coral reef sharks is essential to understand their role in reef communities and to design targeted conservation strategies for this crucial predatory guild [

4]. Their movements and habitat selection are not only influenced by intrinsic factors but also by a complex interplay of biotic and abiotic variables, which ultimately dictate an individual's success in acquiring food, mates, and safety from predators [

2].

Animals regulate their home range size and residence times within habitats based on factors like habitat quality and competition [

7,

9]. Theoretical models further underscore the impact of habitat quality on turnover rates, with lower turnover rates in optimal habitats [

2,

11,

12,

13]. Such insights are particularly pertinent for apex predators, as they can have spatially explicit effects on top-down control and ecological cascades [

8].

These ecological relationships bear significant conservation implications, especially considering the global decline of shark populations due to overfishing [

10]. The establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) has emerged as a cornerstone of shark conservation efforts [

10]. The benefits of MPAs are multifaceted, encompassing social, ecological, and economic aspects and they offer promise for the conservation of such threatened, highly migratory species. However, the effectiveness of these measures hinges on a deep understanding of predator movement patterns, which can vary seasonally and with habitat [

2,

7]. Indeed, Speed et al. [

14] found that the range of

C melanopterus was well outside the region of the designated MPA. While shark populations are naturally small, especially in fragmented environments [

15], conservation planning must consider their unique needs.

The biological characteristics of the blacktip reef shark include slow growth and low reproductive output [

6,

16] that underscore its vulnerability. This vulnerability is further accentuated by the species' extensive use of coastal habitats, where critical life events such as mating, pupping, and juvenile growth occur, render them highly sensitive to environmental pressures. Further, their wide-ranging distribution across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, a region with minimum fisheries management [

10] puts them at a heightened risk from Asian shark hunting nations supplying the shark fin trade. Consequently, gaining insights into how foraging ecology influences their movement parameters becomes imperative for the development of effective conservation strategies.

In this study, we investigate the movement patterns of this widely distributed species, in the context of its utilization of a fringe lagoon in Mo'orea. Through underwater observations, we shed light on previously undocumented variations in coastal habitat use which highlight the species’ ecological flexibility.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in the lagoon situated between Opunohu and Cook’s Bay, located on the northern coast of Mo’orea Island [

10]. This lagoon is approximately 3 to 4 km in length and extends from 0.8 to 1.2 km from the shoreline to the barrier reef. During the study period, it was characterized as a thriving coral habitat, with an average depth of approximately two meters.

For the purposes of this study, the lagoon was subdivided into five regions, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Due to physical limitations, Section A was the core study area, and the others were used to gather more data. The lagoon borders, the fore-reef opposite site A, and the nurseries located at the ends of the barrier reefs were monitored to acquire supplementary information about the movements of the species.

To minimize the impact of observation on the behaviour of wild sharks, it was imperative to habituate them to the presence of the researcher. Staged encounters, which involve the deliberate attraction of the target species, is an acknowledged method for studying wildlife behaviour [18]) and was adopted for this purpose. Accordingly, between 11 April 1999, and 29, September 2005, fish scraps were provided at designated locations within the lagoon on a weekly basis. This approach proved effective in habituating the blacktip individuals to the observer’s presence, with the result that they exhibited fairly natural behaviour during encounters without food provisioning. The use of provisioning to facilitate the observation of sharks has since been used by other researchers in Polynesia [19,20] and various other regions [21].

Sites were selected in the deeper channel within the barrier reef where the patch reefs were substantial and well-spaced, allowing for unobstructed views through the coral. Both juvenile blacktip sharks and adults frequented the area. Each site required a wide, open area for food placement, spacious enough to accommodate at least a dozen adult blacktip sharks circling with ease. Clear swim-ways were necessary for the sharks to access the site after following the scent-trail in, and for their exit on the opposite side. A dead coral structure, positioned up-current from the food was required for the observer to use for stabilization.

Once identified, the same site was consistently used in each study section. The secluded nature of the reef area ensured minimal disturbance during data collection.

Each encountered blacktip shark was individually identified using photo-identification techniques [16] and precise drawings of both sides of the dorsal fin. The length, colour, sex, scars, marks, behaviour, and any other distinguishing features were included in the description of each shark.

Feeding sessions were conducted during the hour preceding sunset, due to heightened alertness levels observed in blacktip sharks at this time. The fish scraps utilized consisted of the remnants of oceanic fish after the saleable meat had been extracted by fish shops or hotels. The quantity varied considerably depending on the supply. Typically, since the fishing boats delivered the catch on Friday, the scraps were available on Saturday, so the weekly session was held on Saturday at sunset. On occasion, supplementary scraps became available during the week, allowing an extra feeding session.

Between feeding sessions, random visits to the study area were made at different times of the day. Accessing the western border of the lagoon by kayak, the researcher proceeded slowly eastward underwater, following a zig-zag course and pausing to observe and move with any blacktips encountered.

Observations were conducted between one and five times weekly.

In cases where the ocean swell exceeded 1.5 meters or winds exceeded 60 km/h, the session was postponed until favourable conditions prevailed. Additional observation sessions were conducted in response to exceptional events, such as the presence of rare visitors, spawning events, encounters with sick or injured blacktips, or when the community of blacktips were temporarily absent from the area.

During the course of the 6.5 year study, a total of 475 individual blacktip reef sharks (not counting neonates in nurseries), were identified and documented during subsequent sightings (See Identification Catalogue). Noteworthy details, including time, marine conditions, and incidental observations, were documented during underwater sessions and were transcribed into a computer spreadsheet upon return to shore and used to write a full description of the session.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. The community

Table 1 shows the numbers of adult blacktips identified at each of the sites.

The average residential index was calculated by dividing the number of sessions at which the shark was detected by the number of sessions between first detection and last detection. A very few of those recorded as residents remained in the area for only a few months, after which they either died or moved on permanently. Those individuals classified as rare detections were those who appeared in the area once annually or less.

The juveniles identified are presented in

Table 2.

3.1.1. The habitat

Situated on the north shore of the island, this lagoon is protected from the oceanic swell that impacts its southwestern coastline. At that time, it was a thriving coral habitat where diverse conditions had given rise to numerous micro-habitats [

17]. From its white sand shore, its floor of coral rubble and sand shelved slowly out to where the barrier reef rose. The deeper channel along the inner edge of the barrier reef was free of coral and used as a highway by visiting oceanic species such as barracuda (

Sphyraena) and large jack fish (

Carangidae), as well as sharks.

Blacktip reef sharks were the most common elasmobranchs, but whitetip sharks (Triaenodon obesus) nurse sharks (Nebrius concolor), pink whiprays (Himantura fai) and eagle rays (Aetobatus narinari) were present. The occasional lemon shark (Negaprion acutidens) and grey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) also appeared.

The coral was short and thick on the barrier reef itself, and the highest part formed a wide band that scarcely broke the surface when conditions were calm. There, the coral was dead and the surface was covered by a short, tough seaweed, called Turbinaria.

Breaks in the barrier reef occur where rivers discharge into the sea, and they exert a profound influence on the hydrodynamic patterns within the lagoon. The oceanic waves pour over the reef, into the lagoon, and out again through the passes, which can accelerate the flow dramatically when the waves are high due to the funnelling effect of these narrower channels. Oceanic conditions, therefore, determine the water depth in the lagoons and passes. Tidal fluctuations are primarily solar-driven and impart minimal, incommensurate impacts on water levels [

22].

The vicinity of Site A was floored with white sand and studded with irregular patch reefs about one to three metres across, separated by open strands. Porite colonies supported smaller growths of a variety of branching Acropora, Pocillopora, and Millepora corals, while Turbinaria and Sargassum algae formed thick growths on places on the patch reefs where the coral had died. Plentiful fish, eels, and invertebrates animated the region. It was an area frequented by both older juvenile blacktips and adults, while being open enough that the view was fairly unobstructed for observing them. This region was therefore well located for keeping track of individual blacktips moving through.

East of Site A, the coral density slowly became thicker, and in certain shallow areas on and near the barrier reef, there were intricate coral thickets that served as refuges for small blacktip pups. Beyond there, the patch reefs grew larger and farther apart, then gave way to a barren region floored in rubble, almost devoid of coral structures. It extended from the barrier reef more than halfway to the shore, and was approximately 200m wide. Not only did this prominent landmark appear to delimit the core areas of the individuals ranging on each side of it, but here, residents from both Sections A and B could be seen resting during the middle of the day.

East of the barren region lay Section B. There, tall, slender, and healthy porite colonies grew close together in a wide area alive with fish. This was an important refuge for juvenile blacktips, while the thick coral made it more difficult for the much larger adult female sharks to wind their way through. Many small pups, little bigger than neonates, could at times be observed in small groups, following a sinuous path through the shallower parts, almost completely concealed in intricate coral. The Site B sessions were therefore visited by juveniles including many small pups.

Over a duration spanning ten days to two weeks, shortly after the initiation of Section B sessions, the blacktip reef sharks inhabiting the north shore of Mo’orea Island evacuated [

23], including the pups and juveniles refuging in this region. Due to their substantial numbers and the primary research focus on adult specimens, a comprehensive identification of these juvenile individuals remained pending. Following the evacuation, the returning sharks did not immediately revert to their prior behavioural patterns. As a consequence of this disruption, only the Section A data are used for the movement calculations.

In Section C, the patch reefs grew larger and farther apart again, and the depth increased. In the vicinity of the observation Site C, close to the reef, most of the coral was dead and fish populations were notably less abundant compared to the other sites. The observed adult individuals within this area appeared to be transitory visitors, while juveniles seemingly avoided this locale. Only two juveniles were ever seen there and the adults present during observations were different each session, suggesting that they were transients coincidentally passing through. Regrettably, logistical constraints precluded the establishment of additional sessions in Sections D and E, which might have provided further elucidation on this phenomenon.

Proceeding into Section D, the habitat characteristics closely resembled those encountered in Section A, with these features persisting through Sections D and into Section E. The eastern border grew slowly shallower and gave way to reef flats, then a wide, shallow region on the reef itself. Consequently, each site featured a distinct array of individuals.

3.1.2. The nurseries and juveniles

Along the curvature of the barrier reef adjoining Cook’s Bay was a prominent blacktip nursery where an annual influx of 100-200 pups was documented. Conversely, at the smaller nurseries located at the western extremity and at the eastern end of the Papetoai lagoon, the pups of only one or two females were recorded. After 6 weeks to 2 months, the neonates began moving along the reef in small groups, displaying a high level of vigilance as they repeatedly circled away and regrouped again, always ready to flee back to the safety of the shallows. As they grew older, they continued to navigate the relatively shallow expanses characterized by dense coral formations that are dispersed throughout the lagoon [

17]. This phase persisted for about the initial two years of their lives, by which time they reached an approximate length of 70 cm (estimated), whereon they began to mingle with the adult sharks.

By the year before maturity, juvenile males were making the transition to the outer reef, while the females were nearly full-sized at approximately 1.5 to 1.8 meters in length. Nevertheless, when compared to mature females, these juvenile counterparts exhibited a relatively slender physique, heightened swimming speed, and pronounced acceleration capacity. Their behavioural attributes were characterized by increased curiosity and a penchant for more audacious endeavours, a disposition that gradually waned upon reaching maturity, whereon they develop the characteristic behaviour of robust, gravid sharks [

24]. Notably, it was during this adolescent stage, at an age range spanning four to five years, that these individuals were observed to adopt an adult pattern of residence within a core home range.

3.2. Movements

Adult blacktip reef sharks exhibited recurring patterns of movement within their established core ranges, albeit with significant individual variations. Some individuals, exemplified by #3, temporarily vacated their home ranges for approximately two weeks during mating and another two weeks for parturition, whereas others displayed prolonged absences, spanning several months. The remaining population were absent on a gradient falling within this spectrum. Their daily behavioural routines also manifested substantial variability. On certain occasions, an individual consistently traversed the same coral formations at nearly identical times on successive evenings for multiple nights before remaining absent from the area for an extended period, as much as a year. While it was not uncommon to observe a blacktip in the core of her range day after day, on the subsequent day she could be on the fore-reef.

Variations in the presence of resident females within the study area were also evident. There were days when these females were conspicuously absent, contrasted with occasions when they congregated to engage with groups of infrequent passers-by. On most days at midday the resident females were Resting in the barren region between Sections A and B [

25], while occasionally, no blacktips were found in that region.

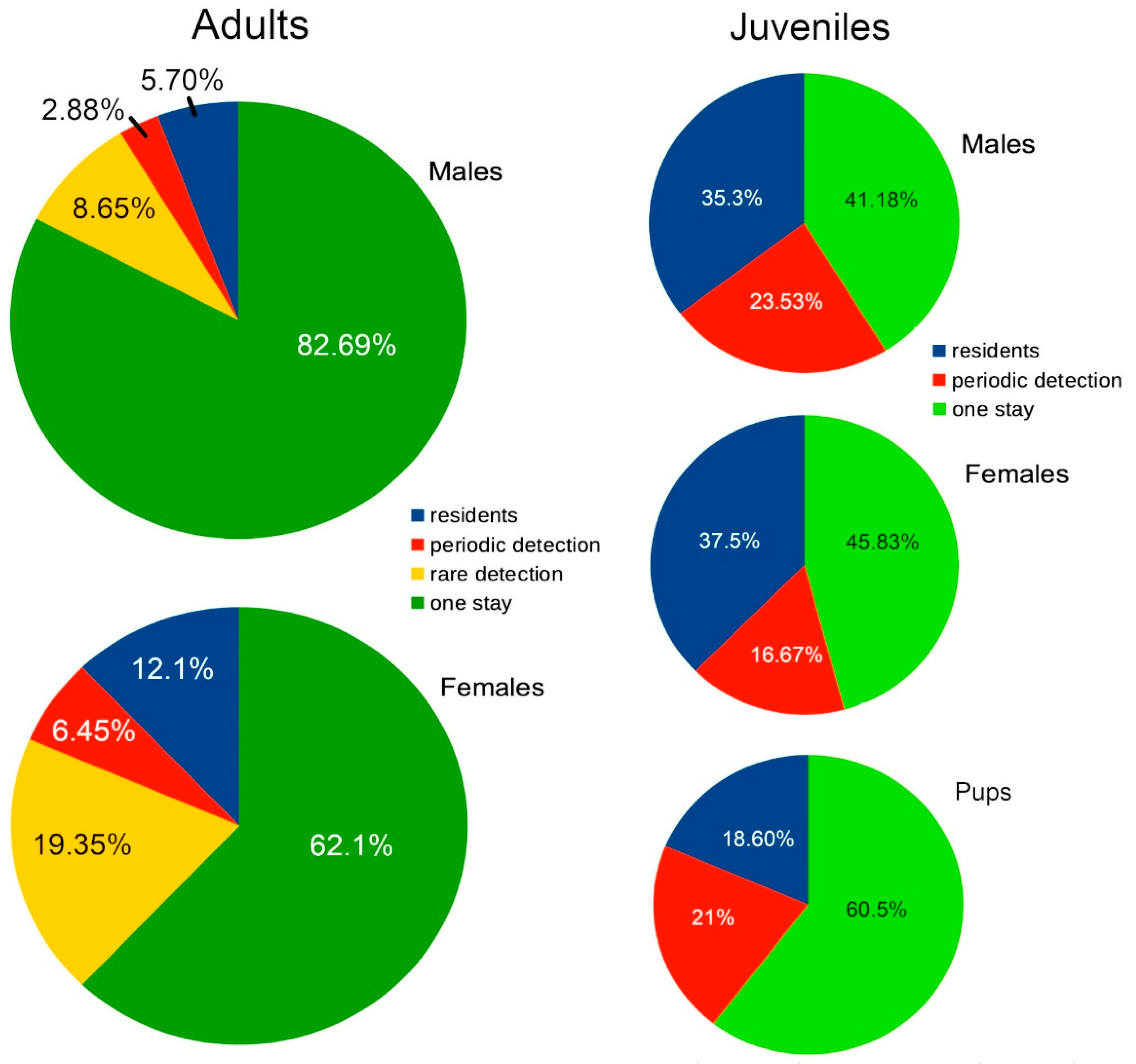

Figure 2 shows the percentages of adult and juvenile blacktips found to be residents, periodic detections, rare detections, or who passed through once or for one period of time, during the 6.5 years in which sessions were held in Section A. Rare detections are those recorded as passing through the area about once annually or less, while periodic detections passed through regularly if infrequently.

3.2.1. Inter-site movements

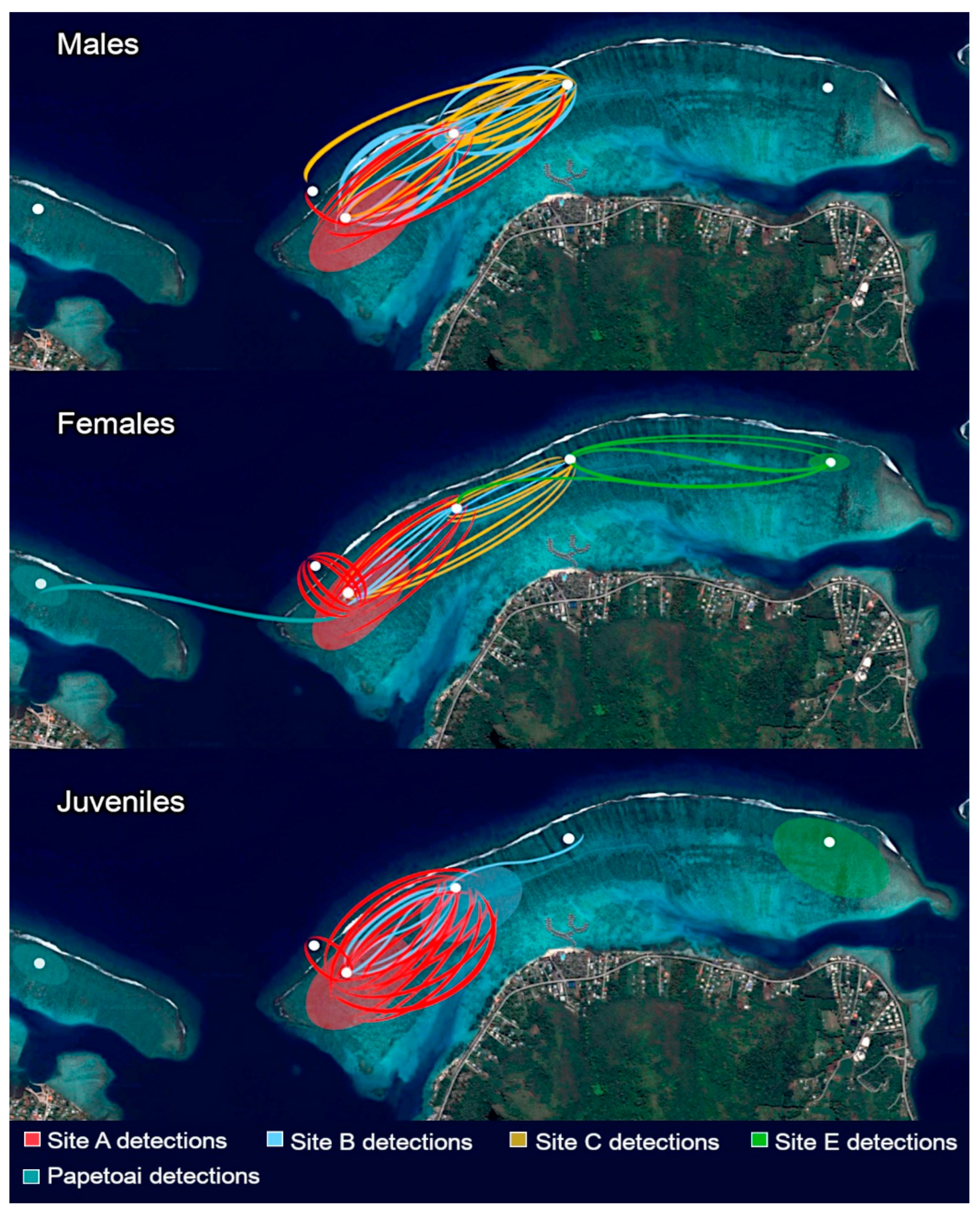

Figure 3 shows detected blacktip movements between sites.

The data analysis reveals that blacktip reef sharks identified across distinct regions demonstrated a pronounced site fidelity to their respective core ranges, with a particularly heightened fidelity observed among those inhabiting the western end of the study area. During observational sessions conducted within Section E, only two unidentified female blacktips were documented, while the other females detected had previously been positively identified at Site C. This finding implies that a substantial portion, amounting to 66.67% of individuals identified at Site E concurrently frequented Site C, a phenomenon that did not extend to female residents from Section A, as none were recorded there.

A noteworthy individual within the female population, designated as #351, and initially identified at Site C, was subsequently re-detected on five separate occasions at the same site. She was also recorded at Site A on 22 occasions and at Site B on 13 occasions. However, despite this extensive documentation, her definitive home range remained undetermined.

In a different scenario, one male pup, labeled as #19, who had matured over the course of the study and had previously been intermittently detected during sessions at Site A, exhibited a notable behavioural shift. During the year of his sexual maturity, he was observed on three separate occasions at the fore-reef site, coinciding with a cessation of detections at Site A. This behavioural transition suggested his establishment within the fore-reef environment as he attained maturity.

3.2.2. Males

The male inhabitants of the lagoon exhibited relatively less attachment to specific core ranges compared to their female counterparts and displayed a propensity for extended roaming. Some individuals were frequently observed traversing both Sections A and B, though, with one exception, they were not seen in Section C. This behaviour suggested either larger core ranges for males in comparison to females or residency within an intermediary region situated between the two designated observation sites. Several males posed challenges in categorization as residents of either Sections A or B. For instance, male shark #4, characterized by a residency index of 0.45, maintained a consistent presence and exhibited patterns akin to the residents, albeit with a tendency for broader excursions when contrasted with females possessing higher residency indices. Other periodic male visitors shared a similar profile with lower residency indexes. These were the males who had established core ranges along the back-reef as opposed to the fore-reef and attended sessions sporadically throughout the year, some infrequently. In contrast, those ranging along the outer slope typically ventured into the lagoon exclusively during the reproductive season, spanning from November to March [

16].

None of the males identified on the fore-reef opposite Section A were observed at Site A. Water depth at the ocean site was about 7 metres, and given that the male blacktip reef sharks moved near the sea floor, their identification necessitated diving to render their distinctive fin markings on both sides, while maintaining uninterrupted visual contact and without the need to resurface for air. Consequently, most of the male sharks encountered were not successfully identified, resulting in limited representation in the recorded dataset. Nevertheless, it was possible to ascertain that these unidentified individuals did not correspond to those frequently sighted within the lagoon.

A discernible distinction in colouration between oceanic and lagoon-dwelling males underscored their respective habitats. Those inhabiting the ocean remained near the ocean floor so were protected from the sun’s rays and exhibited paler hues, including gold, bronze, or ochre. Conversely, lagoon males had dark brown or grey pigmentation, attributed to prolonged exposure to sun-rays in the shallow waters of the lagoon. This chromatic disparity served as a significant indicator of an individual’s primary habitat. Notably, this phenomenon of colour alteration due to sun exposure has been documented in other shark species including nurse sharks [

26] and hammerheads (

Sphyrnidae) [

27].

3.2.3. Females

The majority of rare female passers-by observed within the study area for brief durations were likely en route for parturition, many to the nurseries located along the west coast of the island [

4]. Beginning in September each year, a steady flow of pregnant females was documented moving through the area, and until the study ended, new unidentified females continued to be detected. Mourier & Planes [

28] determined that the species is philopatric and that some of the female blacktips on the north shore of Mo’orea were travelling to other islands for parturition. However, there were also instances of transient individuals passing through the area independently of the reproductive season.

3.2.4. Pups

Among the juvenile blacktip reef sharks, a subset was frequently sighted at both Sites A and B, particularly in proximity to areas inhabited by smaller juvenile conspecifics. Those individuals who initially discovered and regularly attended sessions at Site A likely became aware of the Site B sessions quickly, as the olfactory cues passed through their ranges.

Across all categories, the largest proportion of detected blacktip reef sharks were those individuals observed passing through the study area only once. Unexpectedly, among the juveniles, it was the pups that exhibited the highest incidence of individuals observed only once or for one brief period. Over the course of the study, a consistent influx of smaller juvenile individuals was detected transiently moving through the area, with subsequent observations indicating their absence. The precise fate of these individuals—whether they perished, resettled in alternate habitats, or embarked on extensive migrations—could not be conclusively documented. Of the entire cohort, only two individuals, designated as #29 and #36, were originally identified as pups during their initial passage through the area, and subsequently reappeared as adolescents. This time they remained in the area and became adult residents.

With the research focus primarily concentrated on the adults’ movements through the study area, plus the tendency of the pups to spend more time beyond visual range due to their heightened vigilance, those actually identified represent only a fraction of their actual numbers. Further, 581 blacktip reef sharks were identified initially, but the individuals who were not identified well enough to positively recognize as time passed, and who never reappeared, thus precluding confirmation of their identities, were excluded from the dataset. This culling process ultimately reduced the number of confirmed individual sharks, known beyond any reasonable doubt for future recognition, to 475. It is noteworthy that a significant proportion of the excluded individuals were juveniles, with a substantial fraction comprised of pups that made a solitary passage through the study area. Therefore, the percentage of pups that passed through just one time was significantly greater than the numbers that could be recorded suggest.

3.2.5. Rare passers-by

Rare passers-by typically manifested as small groups comprising fewer than six individuals. Frequently there was much high-velocity interaction on their arrival. Residents and visitors would soar through the surroundings in pairs and small groups. Following each other and moving in parallel, their formations swiftly formed and dissolved [

25]. On occasion, as many as one to two dozen sharks—comprising females, males, and older juveniles—would embark on a synchronous departure, forming a dispersed, elongated group characterized by inter-individual distances ranging from 0.5 to 1 meter, and return at high velocity from another direction.

It was observed that even aged sharks, which typically exhibited minimal episodes of acceleration, would abruptly ascend vertically, shedding their attached remoras, and vanish from sight, followed by many others. Then they and their entourage would reappear and hurtle back through the scene, disappearing in the opposite direction.

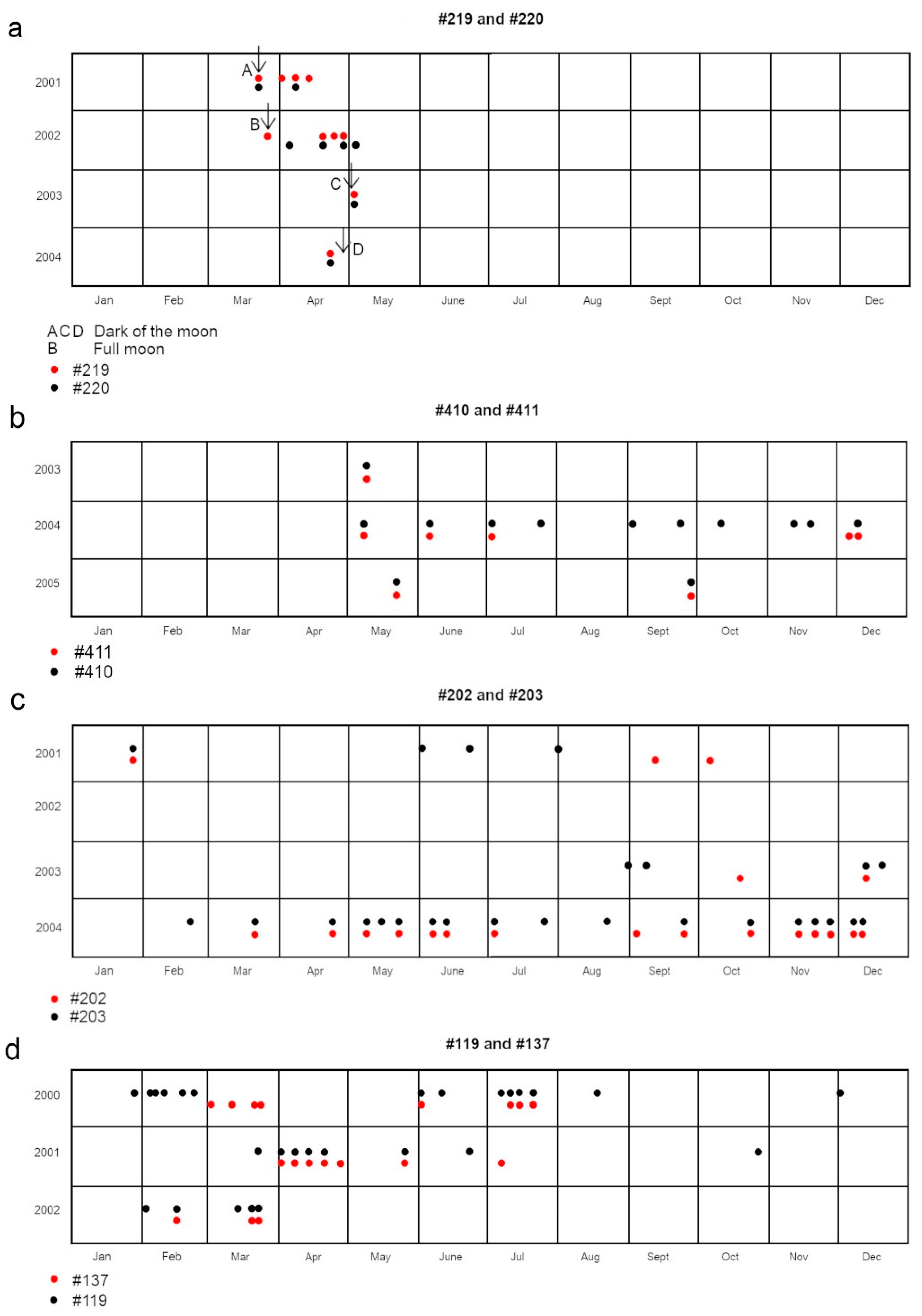

Arrivals of these visiting groups frequently correlated with the lunar phases, both light and dark. They typically remained in the region until the subsequent lunar phase transition—spanning approximately two weeks—before they continued their journey. It was notable that, on several occasions, particular resident female blacktip reef sharks temporarily departed their core ranges to accompany these departing groups of conspecifics along the lagoon. This behaviour underscored the species’ inclination toward socialization and affinity for interactions with visiting blacktips.

Certain of the travelling groups of females were accompanied by one male, the same one each time. He would typically enter the site one or two minutes prior to the appearance of the females.

A significant proportion of the blacktip reef sharks formed enduring partnerships with a consistent companion of the same gender and approximate size. Long-term observation of the Section A residents suggested that these were likely sharks with over-lapping home ranges as was also found by Papastamatiou et al. [

29].

Figure 4 shows the detections of four such pairs of rare passers-by.

3.3. Influences on blacktip movements

The primary influences on blacktip movements were the reproductive season and the lunar cycle.

3.3.1. The reproductive season

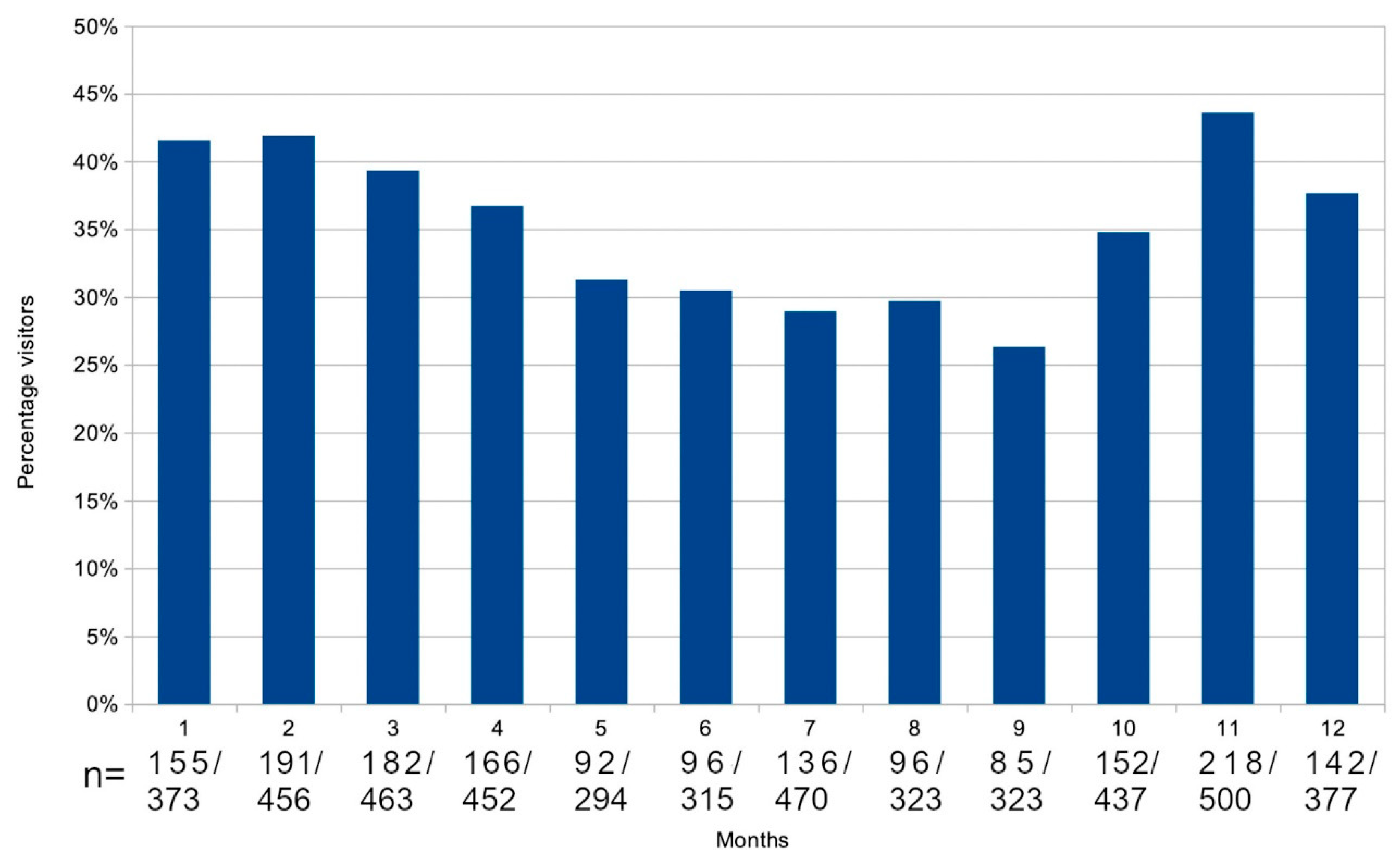

Figure 5 shows the average percentage of adult blacktip passers-by present at the feeding sessions in Section A. The period of regular sessions between 99/04/11 and 02/05/04 in Section A are used for the calculation.

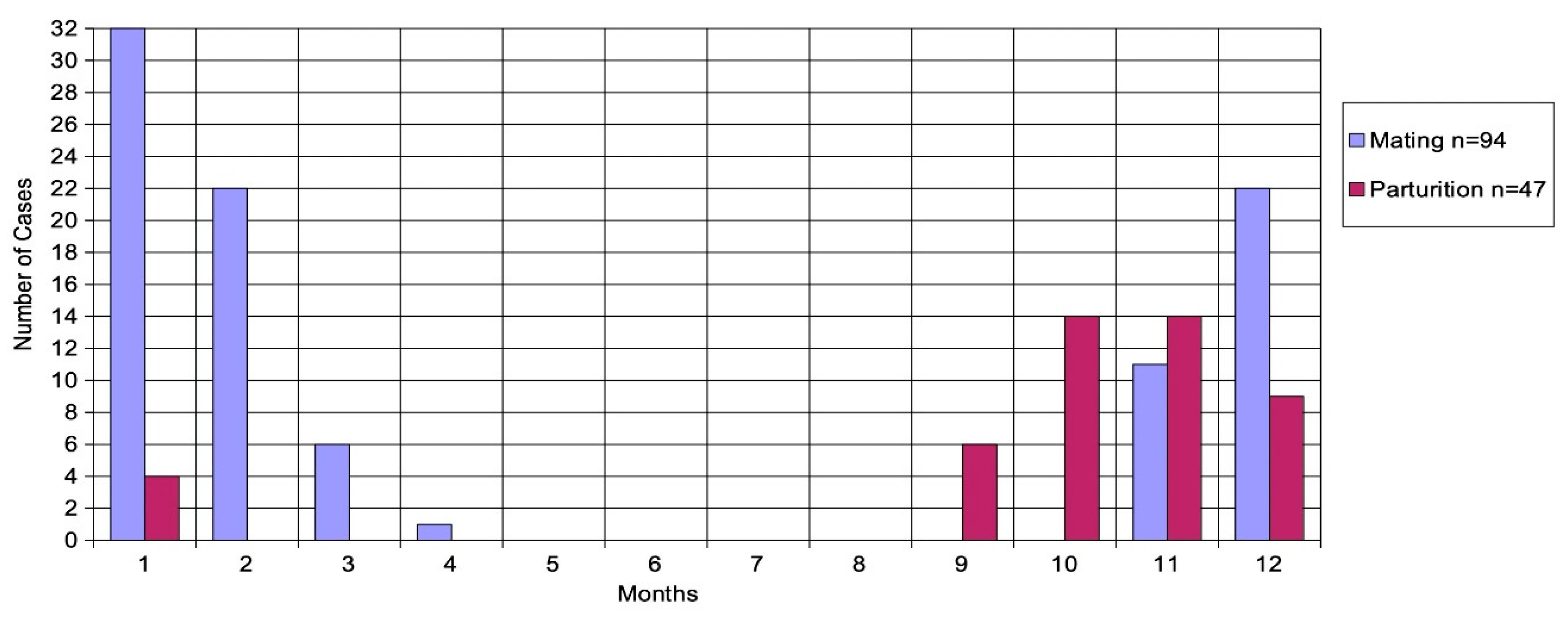

Figure 6 shows mating and parturition recorded in each month.

A comparison with

Figure 5 illustrates the influence of the reproductive season on the blacktips’ movements.

3.3.2. The lunar phase

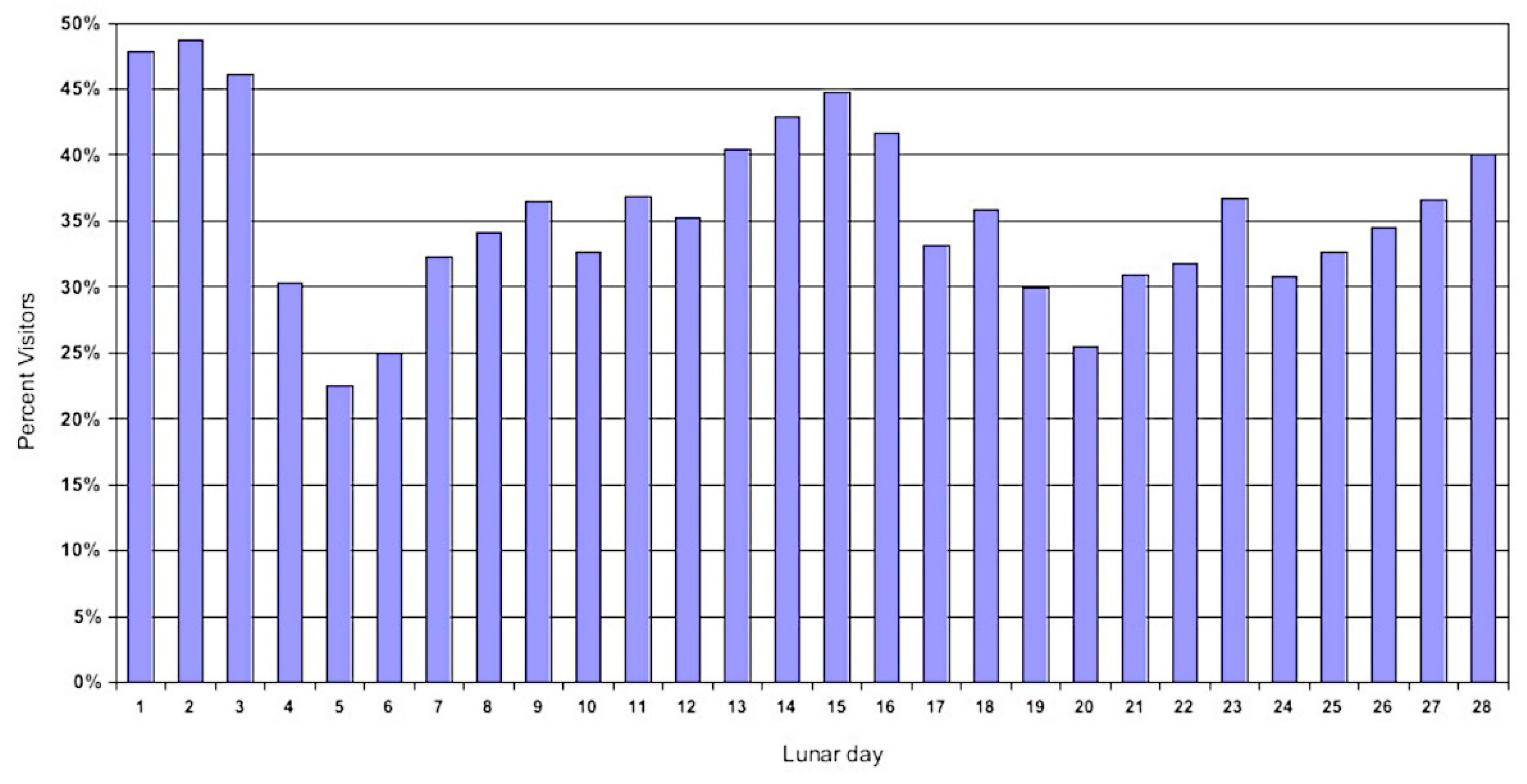

The tendency of the blacktips to move in correlation with the lunar phase is shown in

Figure 7. The higher proportion of visitors during the dark of the moon, as well as the full moon, is evident.

3.3.3. Unusual sessions

A distinctive pattern emerged involving sessions that deviated from the norm, which took place irregularly, many months apart, and displayed a notable correlation with the lunar phase. These sessions were attended by up to twice the customary number of blacktip reef sharks, of which a substantial number were infrequent passers-by, and were characterized by heightened social interactions involving high-velocity, synchronized movement through the region. Conversely, during the full moon phase, a contrasting scenario unfolded at times due to the absence of the resident females. Consequently, during such periods, only the juvenile individuals and one or two of the lagoon-dwelling males attended the session.

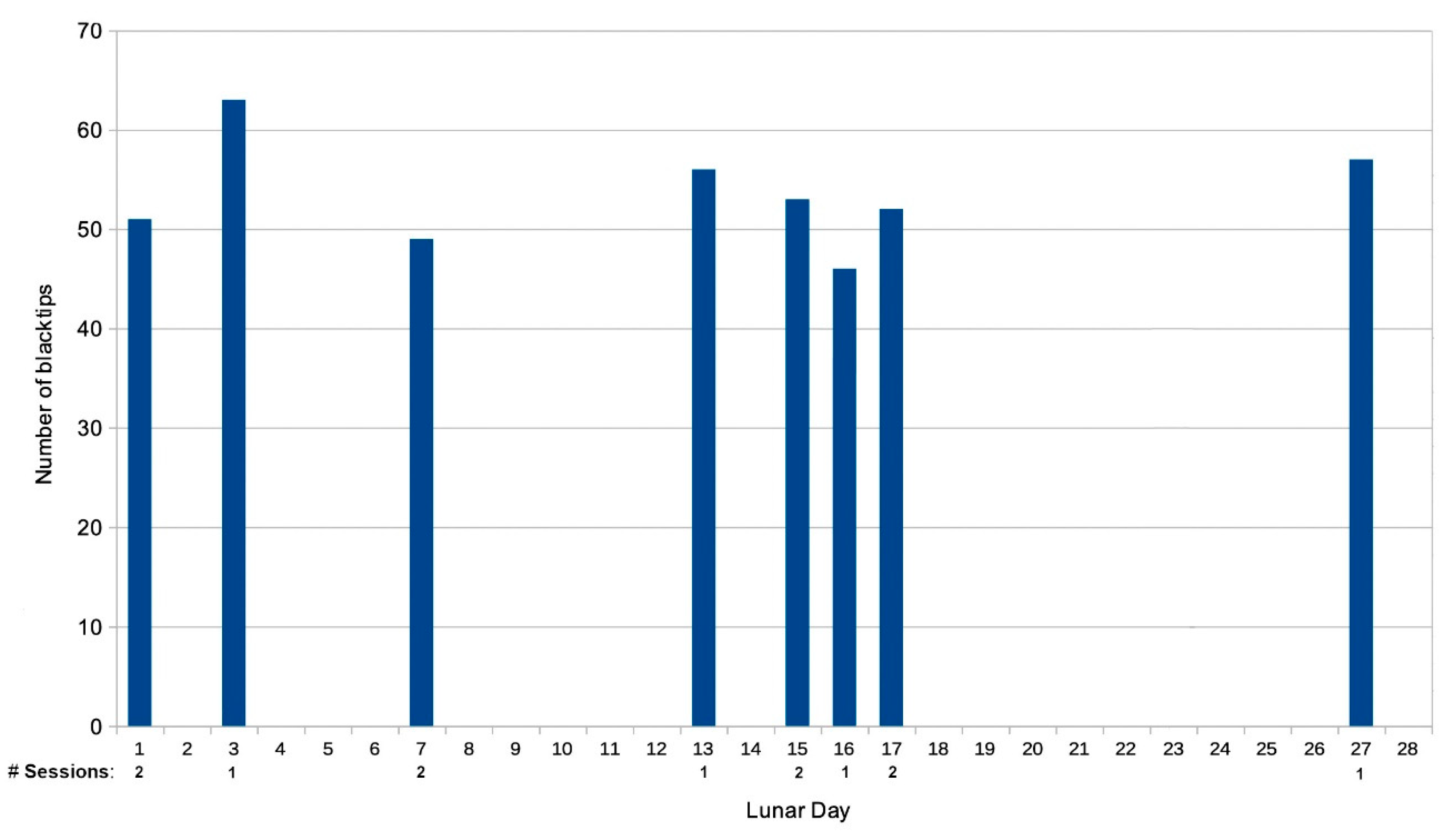

Figure 8 visually depicts the correlation between these distinctive sessions and the lunar day, which notably cluster around the periods encompassing the full moon and the dark lunar phase.

Out of these sessions, six instances, accounting for 50% of the total, coincided with the period of the full moon. Four sessions, comprising 33.33% of the total, transpired during the dark lunar phase. The remaining two sessions, amounting to 16.67% of the total, occurred when the moon was lighted 42%, on Day 7. One of these sessions was marked by the appearance of the female resident of Papetoai (#179) when she made one of her two documented appearances in Section A. A rare periodic male visitor, (#103), who was in the area only during the months of November and December, also appeared at that session. (He was also present during #179’s other documented visit to Section A.)

At one of the unusual sessions that coincided with the full moon, the arrival of two groups of rare visitors, including both #219 and #220 and #119 and 137 (see

Figure 5) were documented. An additional noteworthy observation was the presence of a lemon shark (

Negaprion acutidens) at two of the full moon sessions and at one of those held during the dark lunar phase. Members of this large predatory species rarely entered the lagoon, and most of their visits correlated with the full moon. The juvenile blacktips use those shallow waters for protection from such large predators.

3.3.4. Other influences

On the infrequent occasions when feeding sessions were conducted on two consecutive evenings, it was observed that the majority of sharks attending the second session were distinct from those present during the first session. Over the course of several years of meticulous observations conducted in Section A, a discernible pattern emerged, indicating a proclivity among blacktip reef sharks to depart the area following a feeding session. This observation suggested that their roaming behaviour was not necessarily linked to foraging activities.

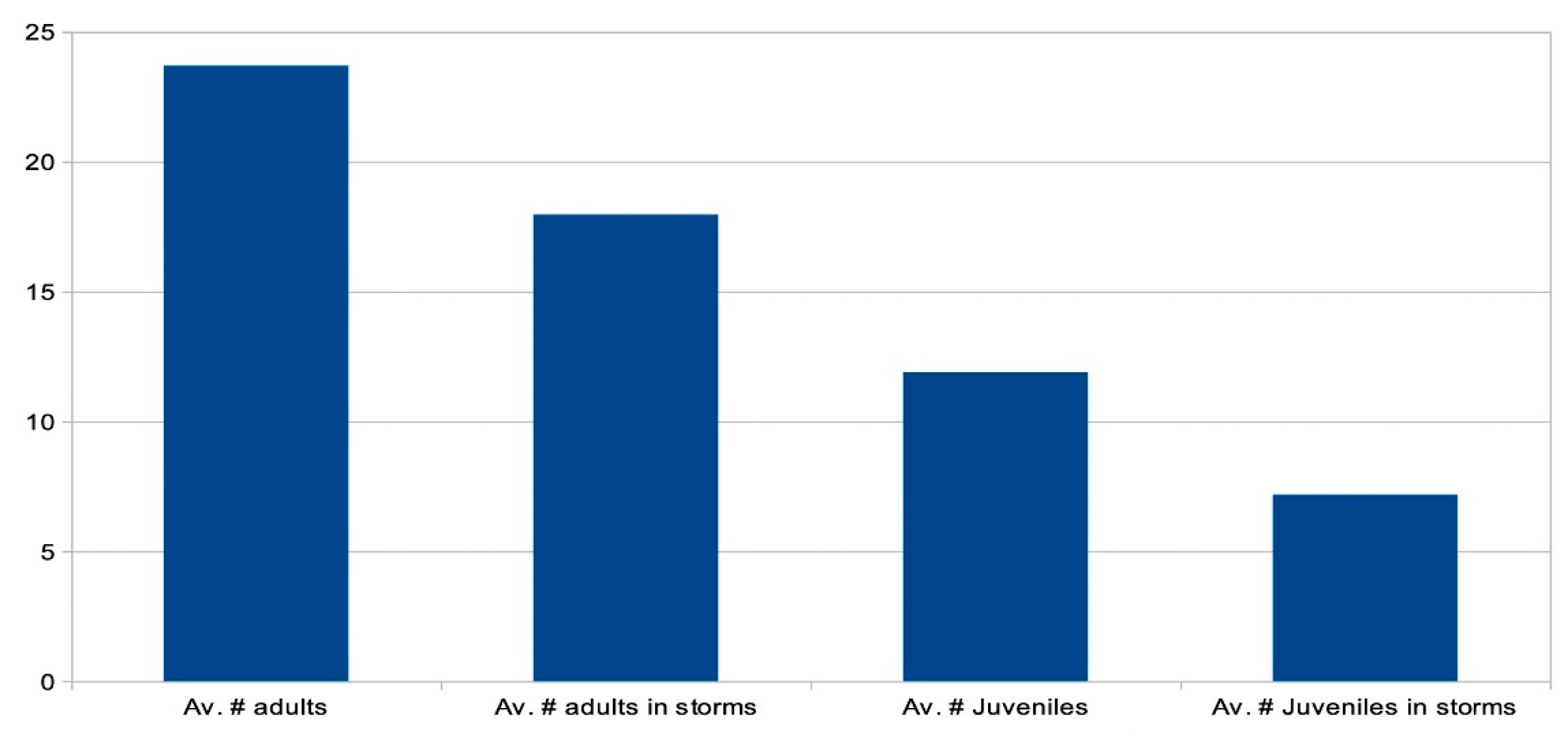

During storms, oceanic waves transformed the lagoon into a powerful river. The larger females, particularly when pregnant, exhibited a relative lack of agility in heavy current. Significant energy expenditure was required for them to navigate the complex coral terrain in such turbulence. Consequently, during storm events, a notable proportion of these individuals departed, possibly seeking refuge in the deeper waters off the fore-reef. Conversely, the smallest juveniles, who displayed the least inclination to venture away from the protective shallows, adeptly manoeuvred through the coral in strong turbulence with less exertion. Additionally, they found it easier to take refuge behind larger patch reefs.

Figure 9 graphically illustrates the average attendance of sharks during sessions conducted under calm conditions and those held amid stormy conditions. Attendance by adult individuals was recorded across all stormy sessions. However, under extreme conditions, some sessions featured limited attendance by adult females, with only a few small juveniles present.

When a Singapore-based company commenced finning the reef sharks inhabiting the region, those not immediately killed fled the area in response. While a portion of the displaced sharks did return within a relatively short span of ten days, the majority exhibited a protracted absence, with many taking more than two weeks to reestablish themselves within their core home ranges. Some did not reappear in their home ranges until the corresponding period of the subsequent lunar cycle. This behavioural tendency was corroborated by the accounts of native Tahitians, who, motivated by a desire to protect them, wanted their sharks neither fished nor disturbed [

26]. A comparable inclination to vacate the area following the slaughter of some of their kin was observed among tiger sharks in the Bahamas [

30]. The tiger sharks remained absent from the region for about two months.

During the time-frame spanning from July 23 to August 5, 2002, a notable occurrence transpired on Mo’orea Island, involving the complete disappearance of all blacktip reef sharks under human observation, including the smallest pups refuging in the shallow regions of thick coral. Despite exhaustive investigative efforts aimed at discerning the cause for this mass evacuation, no satisfactory explanation could be found. It is plausible that external factors, not subject to local authority monitoring, may have disrupted the sharks, prompting the entire population to vacate the shallow waters surrounding the island. Not all adult residents, and few of the pups, returned to their previously inhabited ranges.

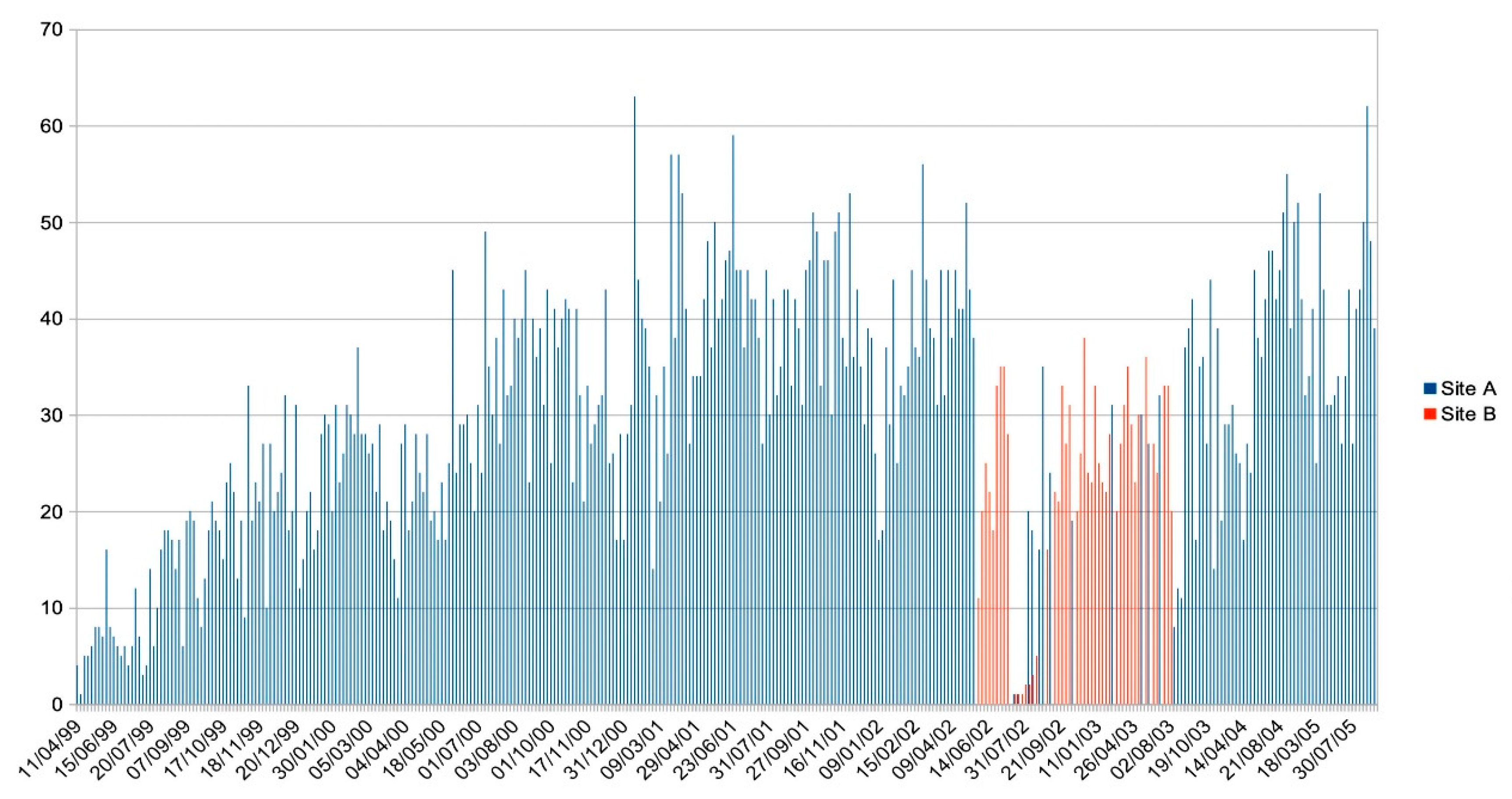

Figure 10 graphically depicts the numbers of sharks attending Site A and B sessions, showing these disappearances.

4. Discussion

4.1. The community

C. melanopterus displayed high levels of site fidelity to fairly small core home ranges. These findings align with previous research conducted in various geographical regions, including Australia [

6,

31,

32], Palmyra Atoll [

2,

5], and Aldebra Atoll. Specifically, adult females and juveniles displayed a preference for the back-reef habitat, while male sharks exhibited a tendency to favour the fore-reef environment, corroborating observations made by Mourier et al. [

4].

Sexual segregation within shark populations is a widespread phenomenon [

34,

45] and is often attributed to the reduction of harassment and injury risks for females. However, during our 6.5-year study, no evidence of female harassment by lagoon males with over-lapping core ranges was observed. On occasions when groups of males from the fore-reef ventured onto the back-reef, presumably for mating purposes, resident females notably interacted with them in a non-avoidant manner, thus indicating a social dimension to this form of segregation, as similarly reported by Mourier et al. [

4].

Chin et al. [

6] reported the presence of only juveniles and adult females in shallow water refuges, with adolescents and male sharks being conspicuously absent. Conversely, Papastamatiou et al. [

2,

5] documented a more even distribution of males across the lagoons of Palmyra Atoll, accompanied by limited evidence of sexual segregation. In our study, only a select few individual males continued to range the back-reef habitat post-maturity, suggesting flexibility in segregation behaviour and habitat utilization within the species, possibly correlated with individual variability.

Despite certain sedentary aspects observed in their behaviour [

5,

6,

7,

33], the data underscores the prominent role of movement as a key component of activities within C. melanopterus communities. Nonetheless, the existence of individual differences [

3] in spatial and temporal movement patterns somewhat obfuscates the precise delineation of core ranges in the present study. Notably, landmarks and habitat features emerge as significant factors contributing to the demarcation of these ranges [

2,

36]. The ecological characteristics of each region exert a defining influence on their distribution.

The absence of blacktip reef sharks utilizing the Site C region as a home range can be attributed to various factors. This region featured large, widely spaced, mostly deceased patch reefs, characterized by reduced fish populations. Furthermore, the presence of a shoreline hotel, complete with overwater bungalows extending far into the lagoon, contributed to continuous boat traffic, potentially rendering the sharks sensitive to the disturbance through auditory and lateral line senses, which assume paramount importance for sharks in navigating a world where light penetration is limited [

25]. The region’s exposure to shark provisioning activities over a year’s duration further accentuates how even daily provisioning does not compel sharks to move into a specific region [

38].

The utilization of small and shallow nursery areas by neonates aligns with findings in other studies [

5,

36,

37,

38,

40]. Nevertheless, the coexistence of adult sharks with small pups challenges conventional nursery theory, which posits size segregation as a mechanism to mitigate predation risks for neonates and juveniles. Remarkably, observations by Chin et al. [

6] and the present study consistently reveal that adult females interacted with small pups in a manner analogous to larger conspecifics [

25]. The gradual exploration away from nursery areas by pups over time, was also noted by Bouyoucos et al. [

40].

Similar habitat utilization patterns have been identified among lemon sharks of different age groups in the Bimini lagoon, with juveniles transitioning into deeper waters as they mature [

41]. This suggests that it is a successful strategy used not only by blacktip shark pups [

36,

39,

40] for predator avoidance.

4.2. Movements

It is of interest to note that 66.67% of the female sharks detected at Site E had previously been identified at Site C, whereas no female residents from Site A were ever observed in the central region of the lagoon. One plausible explanation for this phenomenon relates to the water current formed by the flow of water over the barrier reef. This current bifurcates within the lagoon, diverging either westward or eastward slightly to the east of Site C. This hydrodynamic factor could have exerted an influence on the movement patterns of blacktip sharks. Those individuals inhabiting the westward side of the current divergence typically made periodic visits to the study area every few months, with the frequency varying among individuals.

Despite the geographical proximity of approximately 300 meters between the study area and the lagoon at Papetoai, distinct and seemingly isolated communities were found, each comprising females, juveniles, and the occasional male shark, with minimal inter-bay movement. Only a solitary female, identified and consistently re-sighted in the Papetoai lagoon, was ever recorded in Section A, detected twice in two different years. No individuals from the study lagoon were seen in the Papetoai lagoon. It is conceivable that the blacktip sharks inhabiting Papetoai may have exhibited a preference for westward rather than eastward travel due to geographical constraints. Notably, Papetoai's lagoon is narrow, with a significant nursery habitat situated to the west along the island’s west coast [

4]. However, the period of observation in Papetoai did not encompass the reproductive season. Therefore, it is plausible that some females travelling within the study lagoon could have transited through Papetoai en route to west coast nurseries. This phenomenon aligns with the findings of Papastamatiou et al. [

2], who similarly observed low levels of inter-lagoon movement and varying residence times in different regions, although the underlying reasons remain enigmatic, possibly linked to trophic ecology [

2].

Yet, despite the reluctance of resident females from Section A to traverse the bay, they were consistently sighted during daylight hours on the fore-reef opposite their core range, often engaged in what appeared to be hunting behaviour as they moved parallel to the reef beneath the breaking waves. Blacktip sharks were often observed to come over the reef and into the lagoon with a breaking wave, suggesting that hunting the fore-reef constituted a key predatory behaviour.

Of particular interest is the observation that the pups, juveniles with an estimated length of less than 70 cm, exhibited the highest proportion of individuals remaining within the study region for just a single, short time period. This is an unexpected finding, especially considering that the evidence is skewed away from such a result. Yet, throughout the study duration, a steady stream of pups passed through the area, and most were were not detected again. This observation suggests that very young blacktip sharks have a propensity to depart from their birthplace region and do not return. The philopatric nature of blacktip females returning to their birthplace for parturition [

28], offers valuable insights. If adults undertake extensive journeys, including inter-island migrations [

28] to return to the place of their births, it follows that their younger counterparts also embark on travels away from their birth region during their earlier life stages to establish home ranges on other islands. The behaviour of the pups in the current study suggest that dispersal might occur as early as the age of 1.5-2.5 years.

The males residing in the lagoons typically displayed a dark grey/brown coloration, but upon their return from oceanic excursions following the reproductive season, they exhibited notably paler hues. This change in pigmentation is indicative of significant periods spent in the open ocean during their absences. Considering the presence of female sharks within the lagoons and the fact that these males could have navigated within the lagoons while undertaking their travels, their extended voyages through the ocean imply that they may have departed from Mo’orea to visit other islands within the surrounding archipelago [

15,

28,

32].

The phenomenon of male-based dispersal is regarded as a life-history trait of C. melanopterus in French Polynesia [

15]. Vignaud et al. [

15] considered that otherwise philopatry [

28], a phenomenon observed annually [

16], would otherwise prevent the species from colonizing new areas. The observed range of dispersal in C. melanopterus rarely extends beyond approximately 50 km to other island groups [

15]. However, the formation of Mo’orea approximately 1.5 to 2 million years ago [

42] underscores the potential for the ancestors of the current individuals inhabiting these waters to have embarked on extensive oceanic movements away from their original Asian origin [

43]. Given the substantial individual variation within the species, it is plausible that some C. melanopterus individuals occasionally undertake considerably longer journeys than those observed.

Speed et al. [

31], in their research on sharks within a Marine Protected Area in Australia (Ningaloo Reef), reported female

C. melanopterus exhibiting long-distance movements, apparently linked to parturition, with distances surpassing those observed in Polynesia, and ranging up to 275 km. Their mean activity space estimates for adult blacktip sharks were 12.8 km2 ± 3.12, and 7.2 ± 1.33 km2 for juveniles, figures notably larger than those observed in the current study. Individuals that exhibited recurrent absences for extended periods, as well as rare visitors, may have ventured among the nearby islands. Genetic studies [

28] using DNA analysis indicated that some female blacktip sharks from the north shore of Mo’orea Island indeed journeyed to other islands for parturition.

The observation that small juveniles are already engaged in long-distance movement patterns challenges conventional thinking on the timing of dispersal. Chin et al. [

6,

7] have also documented the tendency of juveniles to exhibit short-term residency.

4.3. Influences on blacktip movements

Shark #115 was a male blacktip who exhibited recurring visits to the study area with a periodicity of several months. His first four appearances, though months apart, coincided with the onset of sunset, precisely when the sun’s sphere touched the horizon. Furthermore, his passage occurred four days prior to the darkest phase of the lunar cycle. This observation was the initial clue that not only do C. melanopterus individuals engage in roaming behaviours influenced by both solar and lunar cues, but that they do so with unexpected precision, suggesting an awareness of time.

Figure 5 clearly illustrates that the blacktips congregating at the observation sessions originated from different sources. However, in many studies examining shark social systems where interactions are not readily apparent or recorded via remote technologies [

44], there often exists an implicit assumption that individuals in close spatial proximity are socially engaged with each other, an idea known as the “gambit of the group.” However, the nature of this ‘group’ has neither been identified nor well-defined. In the current study it is clear that a significant percentage of the sharks congregating at the feeding sessions were passers-by with different origins and therefore the individuals present at any given session did not form such a ‘group.’ This calls into question the applicability of this assumption for this species and possibly other shark species as well [

45,

46].

Blacktip sharks navigate their ranges using wide circular paths that periodically take them out of visual contact with one another, only to bring them back into each other’s proximity eventually through their systematic circling [

25]. Over several years of observation, it became evident that companions often moved out of visual range of each other, only to reunite when their circling paths converged. This tendency for companions to move out of visual range of each other further complicates the notion that spatial proximity necessarily correlates with social affiliation.

The overlapping core ranges of the study area’s resident sharks, frequent crossings of each other’s paths, regular sightings in each other’s company, and departures from the area together, provide reasonable grounds to consider that these interactions contribute to the formation of the strong bonds often observed between individuals [

20,

47].

In contrast to many other regions around the world where lunar phase correlations are often tied to tidal patterns, in Polynesia, the tide is solar. This distinction results in only minor fluctuations in water levels, with a mere few centimetres’ difference between low and high tides in lagoons, along their perimeters, and at the passes [

22]. Water depth in these areas is primarily influenced by oceanic conditions and the volume of water cascading over the reef. So the correlation with the lunar phase cannot be explained by the opening and closing of waterways. A correlation with the lunar cycle has been noted in great white sharks [

48] and in aggregations of sharpnose sharks (

Rhizoprionodon longurio) [

49]. In both cases, the bright and dark lunar phases were significant. On the other hand, Gallagher et al. [

3] did not find a lunar correlation in the movements of Caribbean reef sharks (

Carcharhinus perezii) or tiger sharks (

Galeocerdo cuvier).

Utilizing moonlight for navigation in the intricate coral habitat is understandable, as it provides a visual aid in avoiding obstacles. However, the rationale for utilizing the dark lunar phase remains less evident. Notably, certain rare passers-by consistently arrived in the study area during or immediately following the dark lunar phase; one case is illustrated in

Figure 4a. Since these rarest visitors are those most likely to originate from other islands, their choice of this specific time period for traversing stretches of ocean suggests a degree of awareness regarding their detectability [

25]. As meso-predators, they occupy a position within the food chain that renders them potential prey for oceanic sharks [

51].

Sharks are known to make navigational decisions using various sensory cues, including infrasounds [

52] and the Earth’s magnetic field [

49,

51]. Additionally, chemoreception likely allows them to discern the distinct scents emanating from each island, each marked by its unique chemical signature. Indeed, it is plausible that an individual scent trail, characterized by a long, gradual diffusion, extends through the ocean from each island, carried by the unique waters of lagoons and rivers. Sharks traversing oceanic expanses could potentially utilize these island-specific scent trails for navigation.

4.4. Rare passers-by and unusual sessions

The rare female visitors moving through the study area for parturition displayed a remarkable pattern of annual returns, sometimes almost to the day (±2 days). A notable observation was that a substantial proportion of these females travelled with a preferred companion. Such enduring companionships between individuals have also been documented in other shark species, including bull sharks [

21] and grey reef sharks [

29]. Similar to the findings in the current study, these companion sharks were observed to join other groups of sharks and subsequently separate from them to continue their journey together—a phenomenon referred to as ‘fission and fusion’.

Some of the visitors that were received with most high-velocity socializing were among the rarest, so these observations suggest that the resident sharks under observation may have acquaintances they encounter once a year or even less frequently, implying a capacity for long-term individual recognition. Given the complex travel patterns documented for these sharks [

28,

44], it is plausible that they maintain knowledge of other blacktip sharks with distant home ranges that they infrequently encounter.

In this study, the majority of individuals had preferred companions, though some, including infrequent visitors, were consistently solitary. The demonstration of multi-year bonds and the evident excitement displayed by blacktip sharks during social interactions underscore the significance of social life in C. melanopterus [

25]. It is worth noting that social learning, a phenomenon described as a potential enhancer of foraging success in shared contexts [

29], was regularly observed among the blacktips in the current study [

25].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the study of blacktip reef sharks in the French Polynesian waters revealed intriguing insights into their behaviour and social dynamics. These sharks displayed high site fidelity to relatively small core home ranges, mirroring findings from other regions. Despite their sedentary tendencies in certain aspects, they engaged in substantial movement activities, influenced by individual variations, habitat characteristics, and ecological preferences. The prominent influence of the lunar phase on their movements is of special interest.

While spatial proximity does not denote social affiliation in blacktip reef sharks, long-term bonds between individuals were evident, and social life appears to be of paramount importance in the species, demonstrating the capacity for individual recognition and social learning among blacktip reef sharks.

Overall, this research contributes valuable insights into the multifaceted lives of blacktip reef sharks and highlights the importance of considering individual variation, flexibility, and complex social behaviours, in shark studies, as well as in the designation of MPAs.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Castro, J.I. The origins and rise of shark biology in the 20th century. Mar. Fish. Rev. 2017, 78, 1433. [Google Scholar]

- Papastamatiou, Y.P.; Friedlander, A.M.; Caselle, J.E.; Lowe, C.G. Long-term movement patterns and trophic ecology of blacktip reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus) at Palmyra Atoll. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2010, 386, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, A.J.; Shipley, O.N.; van Zinnicq Bergmann Maurits, P.M.; Brownscombe, J.W.; Dahlgren, C.P.; Frisk, M.G.; Griffin, L.P.; Hammerschlag, N.; Kattan, S.; Papastamatiou, Y.P.; Shea, B.D.; Kessel, S.T.; Duarte, C.M. Spatial Connectivity and Drivers of Shark Habitat Use Within a Large Marine Protected Area in the Caribbean, The Bahamas Shark Sanctuary. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourier, J.; Mills, S.C.; Planes, S. Population structure, spatial distribution and life-history traits of blacktip reef sharks Carcharhinus melanopterus. J. fish biol 2013, 82, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papastamatiou, Y.P.; Caselle, J.E.; Friedlander, A.M.; Lowe, C.G. Distribution, size frequency, and sex ratios of blacktip reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus) at Palmyra Atoll: A predator-dominated ecosystem. J. Fish. Biol. 2009, 75, 647–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, A.; Tobin, A.J.; Heupel, M.R.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Population structure and residency patterns of the blacktip reef shark Carcharhinus melanopterus in turbid coastal environments. J. Fish. Biol. 2013, 82, 1192–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, A.; Heupel, M.R.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Tobin, A.J. Population organisation in reef sharks: New variations in coastal habitat use by mobile marine predators. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2016, 544, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weideli, O.C.; Daly, R.; Peel, L.R.; et al. Elucidating the role of competition in driving spatial and trophic niche patterns in sympatric juvenile sharks. Oecologia 2023, 201, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heithaus, M.R.; Frid, A.; Wirsing, A.J.; Worm, B. Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Porcher, I.F.; Darvell, B.W. Shark Fishing vs. Conservation: Analysis and Synthesis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, K.D.; Christensen, V.; Pauly, D. Description of the East Brazil Large Marine Ecosystem using a trophic model. Scientia. Marina. 2008, 72, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascomte, J.; Melián, C.J.; Sala, E. Interaction strength combinations and the overfishing of a marine food web. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5443–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okey, T.A.; Banks, S.; Born, A.F.; Bustamante, R.H.; Calvopiña, M.; Edgar, G.J.; Espinoza, E.; MiguelFariña, J.; Garske, L.E.; Reck, G.K.; et al. A trophic model of a Galápagos subtidal rocky reef for evaluating fisheries and conservation strategies. Ecol. Model. 2004, 172, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, C.W.; Meekan, M.G.; Field, I.C.; McMahon, C.R.; Harcourt, R.G.; Stevens, J.D.; Babcock, R.C.; Pillans, R.D.; Bradshaw, C.J.A. Reef shark movements relative to a coastal marine protected area, Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignaud, T.; Clua, E.; Mourier, J.; Maynard, J.; Planes, S. Microsatellite Analyses of Blacktip Reef Sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus) in a Fragmented Environment Show Structured Clusters. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcher, I.F. On the gestation period of the blackfin reef shark, Carcharhinus melanopterus in waters off Mo’orea, French Polynesia. Mar. Biol. 2005, 146, 1207–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galzin, R.; Pointer, J.P. (1985) Moorea Island, Society Archipelago. In: B Delesalle, R Galzin & B. Salvat (Eds). 5th International Coral Reef Congress, Tahiti, 27 May to 1 June 1985. French Polynesian Coral Reefs: 1985, 1, 73–02.

- Jamieson, D.; Bekoff M. On Aims and Methods of Cognitive Ethology. PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, Symposia and Invited Papers, 1992, 2, 110–124.

- Mourier, J.; Vercelloni, J.; Planes, S. Evidence of social communities in a spatially structured network of a free-ranging shark species. Anim. Behav. 2012, 83, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brena, P.F.; Mourier, J.; Planes, S.; Clua, E.E. Concede or clash? Solitary sharks competing for food assess rivals to decide. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lomd. B: Biol. Sci 2018, 285, 20180006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouveroux, T.; Loiseau, N.; Barnett, A.; Marosi, N.D.; Brunnschweiler, J.M. Companions and Casual Acquaintances: The Nature of Associations Among Bull Sharks at a Shark Feeding Site in Fiji. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, J.L.; Leichter, J.J.; Monismith, S.G. Episodic circulation and exchange in a wave-driven coral reef and lagoon system. Limnol. Oceanogr 2008, 53, 2681–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcher, I.F. Shark evacuation from Mo’orea island in 2002. Beh. (published online ahead of print 2023) 2023. [CrossRef]

- Porcher, I.F. Commentary on emotion in sharks, Beh. 2022, 159, 849-866. [CrossRef]

- Porcher, I.F. Ethogram for blacktip reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus). Beh. (published online ahead of print 2023). 2023. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.H. Sharks of Polynesia Les Éditions du Pacifique, Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia. 1978.

- Lowe, C.; Goodman-Lowe, G. Suntanning in hammerhead sharks. Nature 1996, 383, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourier, J.; Planes, S. Direct genetic evidence for reproductive philopatry and associated fine-scale migrations in female blacktip reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus) in French Polynesia. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastamatiou, Y.; Bodey, T.W.; Caselle, J.E.; Bradley, D.; Freeman, R.; Friedlander, A.M.; Jacoby, D.M.P. Multiyear social stability and social information use in reef sharks with diel fission–fusion dynamics. Proc. R. Soc. B 2020, 287, 20201063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abernethy, J. Personal Communication during interview, 2013. Available online: https://xray-mag.com/content/deep-trust-sharks (Accessed 2023-10-04).

- Speed, C.W.; Meekan, M.G.; Field, I.C.; McMahon, C.R.; Harcourt, R.G.; Stevens, J.D.; Babcock, R.C.; Pillans, R.D.; Bradshaw, C.J.A. Reef shark movements relative to a coastal marine protected area. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaff, A.M.; Heupel, M.R.; Udyawer, V.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Sex-based differences in movement and space use of the blacktip reef shark, Carcharhinus melanopterus. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, J.D. Life history and ecology of sharks at Aldabra Atoll, Indian Ocean. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1984, 222, 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wearmouth, V.J.; Sims, D.W. Sexual segregation in marine fish, reptiles, birds and mammals: Behaviour patterns, mechanisms and conservation implications. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2008, 54, 107–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacoby, D.M.P.; Croft, D.P.; Sims, D.W. Social behaviour in sharks and rays: Analysis, patterns and implications for conservation. Fish Fish. 2012, 13, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustache, K.; van Loon, E; Rummer, J.L.; Planes, S.; Smallegange, I. Spatial and temporal analysis of juvenile blacktip reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus) demographics identifies critical habitats. J. Fish. Biol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, L.W.; Martins, A.P.B.; Heupel, M.R.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Fine-scale movements of juvenile blacktip reef sharks Carcharhinus melanopterus in a shallow nearshore nursery. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 623, 85–97, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26789875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguigne, C.; Vignaud, T.; Meyer, C.; Bierwirth, J.; Clua, É. Evidence of long-lasting memory of a free-ranging top marine predator, the bull shark Carcharhinus leucas. Beh. (published online ahead of print 2023). 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo Moyano, J. E. Investigating escape tactics in newborn tropical reef sharks to understand essential habitat use: A behavioural, kinematic, and physiological approach (Thesis, Doctor of Philosophy). University of Otago. 2023 Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10523/15471.

- Bouyoucos, I.A.; Romain, M.; Azoulai, L.; et al. Home range of newborn blacktip reef sharks (Carcharhinus melanopterus), as estimated using mark-recapture and acoustic telemetry. Coral Reefs 2020, 39, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S.H.; Nelson, D.L.R.; Morrissey, J.F. Patterns of activity and space utilization of lemon sharks, Negaprion brevirostris, in a shallow Bahamian lagoon. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1988, 43, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Neall, V.E.; Trewick, S.A. The age and origin of the Pacific islands: A geological overview. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 3293–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisano Delser, P.; Corrigan, S.; Duckett, D.; et al. Demographic inferences after a range expansion can be biased: The test case of the blacktip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus). Heredity 2019, 122, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourier, J.; Lédée, E.; Guttridge, T.; Jacoby, D.M.P. Network analysis and theory in shark ecology–methods and applications in Shark Research: Emerging Technologies and Applications for the Field and Laboratory, eds J. C. Carrier, M. R. Heithaus, and C. A. Simpfendorfer Boca Raton: CRC Press 2019 337–356.

- Pinter-Wollman, N.; et al. The dynamics of animal social networks: Analytical, conceptual, and theoretical advances. Behav. Ecol. 2014, 25, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, O.; Leu, S.T.; Sih, A.; Bull, C.M. Socially-interacting or indifferent neighbors? Randomization of movement paths to tease apart social preference and spatial constraints. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastamatiou, Y.P.; Bodey, T.W.; Friedlander, A.M.; Lowe, C.G.; Bradley, D.; Weng, K.; Priestley, V.; Caselle, J.E. Spatial separation without territoriality in shark communities. Oikos 2018, 127, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimley, A.P; Ainley, D.G. reat White Sharks: The Biology of Carcharodon carcharias. Nature 1996 517 pages.

- Pérez-Jiménez, J.C.; Sosa-Nishizaki, O.; Furlong-Estrada, E.; Corro-Espinosa, D.; Venegas-Herrera, A.; Barragan-Cuencas, O.V. Artisanal Shark Fishery at “Tres Marias” Islands and Isabel Island in the Central Mexican Pacific. J. Northw. Atl. Fish. Sci. 2005, 35, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, A.J.; Ireland, M.; Rizzari, J.R.; Lönnstedt, O.M.; Magnenat, K.A.; Mirbach, C.E.; Hobbs, J.-P.A. Reassessing the trophic role of reef sharks as apex predators on coral reefs. Coral Reefs 2016, 35, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, B.A.; Putman, N.F.; Grubbs, R.D.; Portnoy, D.S.; Murphy, T.P. Map-like use of Earth's magnetic field in sharks. Curr Biol. 2021, 31, 2881–2886.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myrberg, A.A. Underwatcr sound - its effect on the behavior of sharks. In Hodgson, E.S. and Mathewson, R.F., cds. Sensory Biology of Sharks, Skates, and Rays. Office of Naval Research, 1978 pp. 391–418.

Figure 1.

The study lagoon divided for reference, showing the location of observation sites. Latitude and longitude: Site A: -17.485568, -149.855474. B: -17.482010, -149.849751. C: -17.479502, -149.844196. E: -17.479668, -149.830348. Papetoai lagoon site: -17.485447, 149.870780. Fore-reef site: -17.483705, -149.857041.

Figure 1.

The study lagoon divided for reference, showing the location of observation sites. Latitude and longitude: Site A: -17.485568, -149.855474. B: -17.482010, -149.849751. C: -17.479502, -149.844196. E: -17.479668, -149.830348. Papetoai lagoon site: -17.485447, 149.870780. Fore-reef site: -17.483705, -149.857041.

Figure 2.

The percentages of identified blacktips found to be residents, periodic detections, rare detections, or who passed through once or for one period of time.

Figure 2.

The percentages of identified blacktips found to be residents, periodic detections, rare detections, or who passed through once or for one period of time.

Figure 3.

Blacktip movement between sites. Each line represents the movement of one shark detected in the given area. Rare visitors are excluded.

Figure 3.

Blacktip movement between sites. Each line represents the movement of one shark detected in the given area. Rare visitors are excluded.

Figure 4.

Each dot represents one detection of the indicated individual. a. The arrows point to the precise time of the lunar phase noted in the legend. Blacktips #219 and #220 present detections corresponding to the lunar phase. b. Blacktips #410 and #411 tended to arrive as the full moon phase was passing. In 2004, their first three visits took place a moon apart. c. Blacktip #119 had an unusual appearance and dorsal fin. She was very dark with rashes of white speckles and a large white fleck on each side of her head. She appeared as night fell on six consecutive sessions. But on the seventh session, a #119 lookalike came. She even had identical large white flecks symmetrically placed on her head. It seemed certain that there was an association between them based on appearance alone, but three months passed before they appeared together. d. Blacktips #202 and #203 travelled together at times but at other times they roamed separately.

Figure 4.

Each dot represents one detection of the indicated individual. a. The arrows point to the precise time of the lunar phase noted in the legend. Blacktips #219 and #220 present detections corresponding to the lunar phase. b. Blacktips #410 and #411 tended to arrive as the full moon phase was passing. In 2004, their first three visits took place a moon apart. c. Blacktip #119 had an unusual appearance and dorsal fin. She was very dark with rashes of white speckles and a large white fleck on each side of her head. She appeared as night fell on six consecutive sessions. But on the seventh session, a #119 lookalike came. She even had identical large white flecks symmetrically placed on her head. It seemed certain that there was an association between them based on appearance alone, but three months passed before they appeared together. d. Blacktips #202 and #203 travelled together at times but at other times they roamed separately.

Figure 5.

Percentage of non-residents detected each month. The occasional missed sessions due to hurricanes and storms during December and January, central to the reproductive season, resulted in lower figures than would otherwise have been recorded for those months.

Figure 5.

Percentage of non-residents detected each month. The occasional missed sessions due to hurricanes and storms during December and January, central to the reproductive season, resulted in lower figures than would otherwise have been recorded for those months.

Figure 6.

Mating and parturition for each month.

Figure 6.

Mating and parturition for each month.

Figure 7.

The average percentage of adult passers-by present at the sessions held on each day of the lunar phase. Fifteen represents the full moon. The period of regular sessions between 99/04/11 and 02/05/04 in Section A are used.

Figure 7.

The average percentage of adult passers-by present at the sessions held on each day of the lunar phase. Fifteen represents the full moon. The period of regular sessions between 99/04/11 and 02/05/04 in Section A are used.

Figure 8.

The number of blacktips at the rare unusual sessions graphed against the lunar day on which they occurred.

Figure 8.

The number of blacktips at the rare unusual sessions graphed against the lunar day on which they occurred.

Figure 9.

The average number of blacktips attending the Site A sessions (N=149) between 99/10/18 and 02/05/04 compared with the average attendance during storms generating strong current (N=41).

Figure 9.

The average number of blacktips attending the Site A sessions (N=149) between 99/10/18 and 02/05/04 compared with the average attendance during storms generating strong current (N=41).

Figure 10.

The numbers of sharks attending the sessions at Sites A and B between 99-04-11 and 05-09-29. The absences between 02-07-23 and 02-08-03 when the sharks evacuated are evident as is the break in attendance when intensive finning began in August, 2003, and the disruption after that. Other breaks in attendance are due to bad conditions during the stormy months between November and February.

Figure 10.

The numbers of sharks attending the sessions at Sites A and B between 99-04-11 and 05-09-29. The absences between 02-07-23 and 02-08-03 when the sharks evacuated are evident as is the break in attendance when intensive finning began in August, 2003, and the disruption after that. Other breaks in attendance are due to bad conditions during the stormy months between November and February.

Table 1.

Blacktips identified at each site. The first column provides the number of sessions. So few sessions were held at Site E and Papetoai that it was not possible to identify those individuals temporarily in the area. Since a large fraction of the observation sessions were done in Section A, most sharks that ranged the western half of the lagoon were identified there and are listed under Site A.

Table 1.

Blacktips identified at each site. The first column provides the number of sessions. So few sessions were held at Site E and Papetoai that it was not possible to identify those individuals temporarily in the area. Since a large fraction of the observation sessions were done in Section A, most sharks that ranged the western half of the lagoon were identified there and are listed under Site A.

| |

# Sess. |

Males |

Females |

| |

|

# Det. |

# Res. |

Res. Ind. average |

One stay |

Periodic detection |

Rare detection |

# Det. |

# Res. |

Res. Ind. average |

One stay |

Periodic detection |

Rare detection |

| Site A |

372 |

104 |

6 |

0.55 |

86 |

4 |

9 |

124 |

15 |

0.67 |

77 |

8 |

24 |

| Site B |

48 |

13 |

1 |

0.39 |

7 |

1 |

4 |

12 |

2 |

0.39 |

8 |

2 |

3 |

| Site C |

11 |

16 |

0 |

- |

7 |

7 |

3 |

24 |

0 |

N/A |

17 |

7 |

- |

| Site E |

4 |

0 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

4 |

0.562 |

- |

- |

- |

| Papetoai |

7 |

0 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

14 |

6 |

0.66 |

- |

- |

- |

| Ocean |

5 |

9 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Table 2.

The juveniles (males, females, and pups) identified at each of the sites. Site E was adjacent to a major nursery so no realistic estimate of those attending the few sessions held there could be made.

Table 2.

The juveniles (males, females, and pups) identified at each of the sites. Site E was adjacent to a major nursery so no realistic estimate of those attending the few sessions held there could be made.

| Males |

Sessions |

Detections |

Residents |

Res. Ind. average |

One stay |

Periodic

detection |

Rare

detection |

| Site A |

372 |

17 |

6 |

0.52 |

7 |

4 |

0 |

| Site B |

48 |

6 |

3 |

0.7 |

3 |

0 |

- |

| Site C |

11 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Site E |

4 |

3 |

1 |

0.67 |

- |

- |

- |

| Papetoai |

7 |

4 |

4 |

0.58 |

- |

- |

- |

| Fore-reef |

5 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Females |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Site A |

372 |

48 |

18 |

0.55 |

21 |

8 |

0 |

| Site B |

48 |

7 |

1 |

0.78 |

6 |

0 |

- |

| Site C |

11 |

1 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Site E |

4 |

3 |

3 |

0.69 |

- |

- |

- |

| Papetoai |

7 |

8 |

3 |

0.5 |

- |

- |

- |

| Fore-reef |

5 |

0 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pups |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Site A |

372 |

43 |

8 |

0.47 |

26 |

9 |

0 |

| Site B |

48 |

10 |

3 |

0.57 |

3 |

4 |

- |

| Site C |

11 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Site E |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Papetoai |

7 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Fore-reef |

5 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).