Submitted:

06 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Material

2.3. Statistical Methods

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

| beta | 95% LL |

95% UL |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I consider distance education to be more effective than face-to-face education | 0.322 | 0,259 | 0,385 | <0.001 |

| I believe that the transition from living to distance education has been an opportunity for the evolution of the education system | 0.227 | 0,171 | 0,283 | <0.001 |

| Social isolation from my classmates and teachers makes me depressed | -0.110 | -0,163 | -0,057 | <0.001 |

| Distance education facilitates my professional. family. educational obligations because it provides me with flexibility | 0.153 | 0,094 | 0,211 | <0.001 |

| Distance education prevents me from doing group work with my classmates | -0.065 | -0,126 | -0,004 | 0.037 |

| From the beginning I had the appropriate technological equipment to respond the needs of e-education (tablet. smart phones. computer) | 0.094 | 0,034 | 0,154 | 0.002 |

| Distance education negatively affects my participation in social activities with my classmates | -0.083 | -0,144 | -0,022 | 0.007 |

| I believe that the sudden transition from face-to-face to distance education will negatively affect my future career | -0.057 | -0,112 | -0,002 | 0.042 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patelarou, A. E.; Konstantinidis, T.; Kartsoni, E.; Mechili, E. A.; Galanis, P.; Zografakis-Sfakianakis, M.; Patelarou, E. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Measure Knowledge of and Attitude toward COVID-19 among Nursing Students in Greece. Nurs. Rep. 2020, 10, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmady, S.; Kallestrup, P.; Sadoughi, M. M.; Katibeh, M.; Kalantarion, M.; Amini, M.; Khajeali, N. Distance Learning Strategies in Medical Education during COVID-19: A Systematic Review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Chung, M.-H.; Yang, J. C. Facilitating Nursing Students’ Skill Training in Distance Education via Online Game-Based Learning with the Watch-Summarize-Question Approach during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 109, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, J.; Joseph, M. A. Impact of Emergency Remote Teaching on Nursing Students’ Engagement, Social Presence, and Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57(1), 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Santos, J. A. A.; Labrague, L. J.; Falguera, C. C. Fear of COVID-19, Poor Quality of Sleep, Irritability, and Intention to Quit School among Nursing Students: A Cross-sectional Study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patelarou, E.; Galanis, P.; Mechili, E. A.; Argyriadi, A.; Argyriadis, A.; Asimakopoulou, E.; Kicaj, E.; Bucaj, J.; Carmona-Torres, J. M.; Cobo-Cuenca, A. I.; Doležel, J.; Finotto, S.; Jarošová, D.; Kalokairinou, A.; Mecugni, D.; Pulomenaj, V.; Malaj, K.; Sopjani, I.; Zahaj, M.; Patelarou, A. Assessment of COVID-19 Fear in Five European Countries before Mass Vaccination and Key Predictors among Nurses and Nursing Students. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S. J. Education and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prospects (Paris) 2020, 49, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, P.; Bhandari, S. L.; Pathak, S. Nursing Students’ Attitude on the Practice of e-Learning: A Cross-Sectional Survey amid COVID-19 in Nepal. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0253651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J. B.; Williams, D. T.; Rauer, A. J. Strengthening Lower-Income Families: Lessons Learned from Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Fam. Process 2021, 60, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, R. COVID-19 Pandemic and Emotional Health: Social Psychiatry Perspective. Ind. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2020, 36, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miconi, D.; Li, Z. Y.; Frounfelker, R. L.; Santavicca, T.; Cénat, J. M.; Venkatesh, V.; Rousseau, C. Ethno-Cultural Disparities in Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study on the Im-Pact of Exposure to the Virus and COVID-19-Related Discrimination and Stigma on Mental Health across Eth-No-Cultural Groups in Quebec (Canada). BJPsych open 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiillasper, J. N.; Soriano, G. P.; Oducado, R. Psychometric Properties of ‘Attitude towards e-Learning Scale among Nursing Students. Int J Edu Sci 2020, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsoni, E.; Bakalis, N.; Patelarou, E.; Markakis, G.; Lahana, E.; Patelarou, A. Translation, Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Attitude Scale towards e-Learning (ATel) into the Greek Language. Popul. Med. 2022, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, G. P. Psychometric Properties of ‘Attitude towards e-Learning Scale’ among Nursing Students. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2020, 30, (1–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maatuk, A. M.; Elberkawi, E. K.; Aljawarneh, S.; Rashaideh, H.; Alharbi, H. The COVID-19 Pandemic and E-Learning: Challenges and Opportunities from the Perspective of Students and Instructors. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2022, 34, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsoni, Ε.; Patelarou, A. The Psychosocial Adaptation of the Academic Community to the Abrupt Implementation of Distance Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 2021, 2021, 754–760. [Google Scholar]

- Baatarpurev, B.; Tsogbadrakh, B.; Bandi, S.; Samdankhuu, G.-E.; Nyamjav, S.; Badamdorj, O. Online Continuing Medical Education in Mongolia: Needs Assessment. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2022, 34, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Rosen, M. A.; García-Ibarra, V.; Maycotte-Felkel, S.; Martínez-Toro, G. M. Expectations and Interests of University Students in COVID-19 Times about Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, U. C.; Igwe, P. A.; Mong, I. K.; Nwosu, H. E.; Kanu, C.; Ojemuyide, C. C. Enhancing Students’ Critical Thinking Skills through Engagement with Innovative Pedagogical Practices in Global South. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggiano, M. P.; Fasanella, A. Lessons for a Digital Future from the School of the Pandemic: From Distance Learning to Virtual Reality. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Yu, Q. Online Interactions: Mobile Text-Chat as an Educational Pedagogic Tool. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2022, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, L. V.; Mello, S. F. D.; Silva, T. N. D.; Pedrozo, E. A. Transformative Learning for Sustainability Practices in Management and Education for Sustainable Development: A Meta-Synthesis. Revista de gestão social e ambiental. São Paulo 2022, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechili, E. A.; Saliaj, A.; Kamberi, F.; Girvalaki, C.; Peto, E.; Patelarou, A. E.; Bucaj, J.; Patelarou, E. Is the Mental Health of Young Students and Their Family Members Affected during the Quarantine Period? Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic in Albania. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.; Shorer, T. Beliefs, Emotions, and Usage of Information and Communication Technologies in Distance Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Health Sciences Students’ Perspectives. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 205520762211311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liverpool, S.; Moinuddin, M.; Aithal, S.; Owen, M.; Bracegirdle, K.; Caravotta, M.; Walker, R.; Murphy, C.; Karkou, V. Mental Health and Wellbeing of Further and Higher Education Students Returning to Face-To-Face Learning after Covid-19 Restrictions. PLOS ONE 2023, 18(1), e0280689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alami, Z. M.; Adwan, S. W.; Alsous, M. Remote Learning during Covid-19 Lockdown: A Study on Anatomy and Histology Education for Pharmacy Students in Jordan. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2022, 15, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detyna, M.; Koch, M. An Overview of Student Perceptions of Hybrid Flexible Learning at a London HEI. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larivière-Bastien, D.; Aubuchon, O.; Blondin, A.; Dupont, D.; Libenstein, J.; Séguin, F.; Tremblay, A.; Zarglayoun, H.; Herba, C. M.; Beauchamp, M. H. Children’s Perspectives on Friendships and Socialization during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Approach. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.-M.; Xu, J. Person-to-Person Interactions in Online Classroom Settings under the Impact of COVID-19: A Social Presence Theory Perspective. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 22, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Fowler, D. COVID-19 Crisis and Faculty Members in Higher Education: From Emergency Remote Teaching to Better Teaching through Reflection. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Perspectives in Higher Education 2021, 5, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, A. R. Modeling the Social Factors Affecting Students’ Satisfaction with Online Learning: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Educ. Res. Int. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, A. B.; Ali, M. A.; Lee, J.; Farah, M. A.; Al-Anazi, K. M. An Updated Review of Computer-Aided Drug Design and Its Application to COVID-19. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher AM, K.; Jackson, D.; Massey, D.; Wynaden, D.; Grant, J.; West, C.; McGough, S.; Hopkins, M.; Muller, A.; Mather, C.; Byfield, Z.; Smith, Z.; Ngune, I.; Wynne, R. The Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on Pre-registration Nursing Students in Australia: Findings from a National Cross-sectional Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79(2), 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroquín, B.; Vine, V.; Morgan, R. Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects of Stay-at-Home Policies, Social Distancing Behavior, and Social Resources. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J. L.; Presseau, J. Effects of Parenthood and Gender on Well-Being and Work Productivity among Canadian Academic Research Faculty amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. Can. Psychol. 2023, 64, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osingada, C. P.; Porta, C. M. Nursing and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in a COVID-19 World: The State of the Science and a Call for Nursing to Lead. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Pinto, I.; Antuña-Casal, M.; Mosteiro-Diaz, M.-P. Psychological Disorders among Spanish Nursing Students Three Months after COVID-19 Lockdown: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanji, F.; Kodama, Y. Prevalence of Psychological Distress and Associated Factors in Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, D. A.; Scott, K. M.; Ryan, M. S. Blended and E-Learning in Pediatric Education: Harnessing Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, P.; Han, P.; Shao, H.; Duan, X.; Jiang, J. Generation Z Nursing Students’ Online Learning Experiences during COVID-19 Epidemic: A Qualitative Study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsoni, E.; Bakalis, N.; Markakis, G.; Zografakis-Sfakianakis, M.; Patelarou, E.; Patelarou, A. Distance Learning in Nursing Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Psychosocial Impact for the Greek Nursing Students—A Qualitative Approach. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, U.; Suvro, M. A. H.; Farhan, S. M. D.; Uddin, M. J. Depression and Stress Regarding Future Career among University Students during COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0266686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. The Shift to Online Classes during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Benefits, Challenges, and Required Improvements from the Students’ Perspective. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2022, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, J.-Y.; Jang, M. S. Nursing Students’ Self-Directed Learning Experiences in Web-Based Virtual Simulation: A Qualitative Study. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 20, e12514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| University | HMU* | 308 | 90.3% |

| Upatras ** | 33 | 9.7% | |

| Study year | 1st and2ndyear | 154 | 45.2% |

| 3rd year | 98 | 28.7% | |

| 4th year | 89 | 26.1% | |

|

Do you face any education deficit |

Yes | 39 | 11.4% |

| No | 302 | 88.6% | |

|

Do you have any previous e-education experience |

Yes | 43 | 12.6% |

| No | 298 | 87.4% | |

| Work during 2nd wave | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment | Unemployment due to pandemic |

Working | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Work during 1st wave | Unemployment | 230 | 88.5% | 18 | 6.9% | 12 | 4.6% | 260 | 76,2% |

| Unemployemt due to pandemic | 9 | 29.0% | 14 | 45.2% | 8 | 25.8% | 31 | 9,1% | |

| Working | 9 | 18.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 41 | 82.0% | 50 | 14,7% | |

| Total | 248 | 72.7% | 32 | 9.4% | 61 | 17.9% | 341 | 100.0% | |

| Working status During | n | % | |||||||

| 1st wave | 2nd wave | ||||||||

| Unemployment | Unemployment | 230 | 88.5% | ||||||

|

Unemployment due to pandemic |

18 | 6.9% | |||||||

| Working | 12 | 4.6% | |||||||

| (Total)* | 260 | 76.2% | |||||||

| (Total) | 248 | 72.7% | |||||||

|

Unemployemt due to pandemic |

Unemployment | 9 | 29.0% | ||||||

| Unemployemtdue to pandemic | 14 | 45.2% | |||||||

| Working | 8 | 25.8 | |||||||

| (Total) | 31 | 9.1% | |||||||

| (Total) | 32 | 9.4% | |||||||

| Working | Unemployment | 9 | 18.0% | ||||||

|

Unemployment due to pandemic |

0 | 0.0% | |||||||

| Working | 41 | 82.0% | |||||||

| (Total) | 50 | 14.7% | |||||||

| (Total) | 61 | 17.9% | |||||||

| Attitude about e-education | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disagree | Neutral | Agree | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| From the beginning I felt able - or to meet the requirements of distance education due to my familiarity with electronic devices (tablet, smart phones, computer) | 32 (9.4) | 76 (22.3) | 233 (68.3) |

| From the beginning I had the appropriate technological equipment to respond the needs of e-education (tablet, smart phones, computer) | 26 (7.6) | 68 (20) | 247 (72.4) |

| I encountered network connection problems while attending online courses during the pandemic | 74 (21.7) | 73 (20) | 194 (56.9) |

| The educational institution where I study adequately covered my education needs during the transition from life to distance education.] | 61 (17.9) | 121 (40) | 159 (46.6) |

| Conditions in my living environment (family, friendly, etc.) influenced the use of distance education during the pandemic | 123 (36.1) | 72 (20) | 146 (42.8) |

| My teachers cover my education needs in the implementation of distance education in the pandemic period | 43 (12.6) | 119 (30) | 179 (52.5) |

| The interaction with my teachers was different due to the transition to distance education | 32 (9.4) | 65 (20) | 244 (71.6) |

| I deal with my education obligations in distance education with self-discipline | 45 (13.2) | 81 (20) | 215 (63) |

| Distance education negatively affects my participation in social activities with my classmates | 51 (15) | 70 (20) | 220 (64.5) |

| Distance education prevents me from doing group work with my classmates | 64 (18.8) | 103 (30) | 174 (51) |

| Distance education facilitates my professional, family, educational obligations because it provides me with flexibility | 80 (23.5) | 106 (30) | 155 (45.5) |

| I believe that the application of distance education exclusively has been the occasion for the development of some of my skills | 127 (37.2) | 89 (30) | 125 (36.7) |

| I believe that the transition from living to distance education has been an opportunity for the evolution of the education system | 111 (32.6) | 80 (20) | 150 (44) |

| The sudden use of distance education due to the pandemic caused me negative emotions such as anxiety, worry. | 87 (25.5) | 55 (20) | 199 (58.4) |

| Social isolation from my classmates and teachers makes me depressed | 150 (44) | 72 (20) | 119 (34.9) |

| I consider distance education to be more effective than face-to-face education | 246 (72.1) | 60 (20) | 35 (10.3) |

| The pandemic and the sudden implementation of distance education cause me fear of extending my studies | 61 (17.9) | 60 (20) | 220 (64.5) |

| The new conditions, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, lead me to thoughts of dropping out of my studies | 287 (84.2) | 24 (10) | 30 (8.8) |

| I'm concerned about the progress of my score in distance education | 89 (26.1) | 82 (20) | 170 (49.9) |

| I'm worried about how I'm evaluated under the new educational conditions | 52 (15.2) | 69 (20) | 220 (64.5) |

| I believe that the sudden transition from life to distance education will negatively affect my future career | 98 (28.7) | 85 (20) | 158 (46.3) |

| Attitudes about Distance education | p* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||

| Sex | Female | 2.80 | 0.93 | 0.921 |

| Male | 2.78 | 1.06 | ||

| Age groups | ≤22 | 2.65 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

| >22 | 3.09 | 0.95 | ||

| Children | No | 2.78 | 0.95 | 0.016 |

| Yes | 3.58 | 0.65 | ||

| Single | Yes | 2.74 | 0.95 | <0.001 |

| Other | 3.25 | 0.80 | ||

| University | HMU | 2.81 | 0.97 | 0.667 |

| Upatras | 2.69 | 0.75 | ||

| Study year | Till 2nd year | 2.59 | 0.99 | <0.001 |

| 3rd year | 2.94 | 0.82 | ||

| 4th year | 2.99 | 0.94 | ||

| Work during 1st wave | Unemployment | 2.69 | 0.92 | <0.001 |

|

Unemployemt due to pandemic |

3.22 | 0.98 | ||

| Working | 3.11 | 0.93 | ||

| work during 2nd wave | Unemployment | 2.75 | 0.94 | 0.938 |

|

Unemployemt due to pandemic |

2.61 | 0.96 | ||

| Working | 3.09 | 0.91 | ||

| Attitudes about distance education | ||

|---|---|---|

| rs | p | |

| From the beginning I felt able - or to meet the requirements of distance education due to my familiarity with electronic devices (tablet, smart phones, computer) | 0.177 | <0.001 |

| From the beginning I had the appropriate technological equipment to respond the needs of e-education (tablet, smart phones, computer) | 0.241 | <0.001 |

| I encountered network connection problems while attending online courses during the pandemic | -0.189 | <0.001 |

| The educational institution where I study adequately covered my education needs during the transition from life to distance education.] | 0.407 | <0.001 |

| Conditions in my living environment (family, friendly, etc.) influenced the use of distance education during the pandemic | -0.218 | <0.001 |

| My teachers cover my education needs in the implementation of distance education in the pandemic period | 0.369 | <0.001 |

| The interaction with my teachers was different due to the transition to distance education | -0.258 | <0.001 |

| I deal with my education obligations in distance education with self-discipline | 0.222 | <0.001 |

| Distance education negatively affects my participation in social activities with my classmates | -0.414 | <0.001 |

| Distance education prevents me from doing group work with my classmates | -0.409 | <0.001 |

| Distance education facilitates my professional, family, educational obligations because it provides me with flexibility | 0.533 | <0.001 |

| I believe that the application of distance education exclusively has been the occasion for the development of some of my skills | 0.508 | <0.001 |

| I believe that the transition from living to distance education has been an opportunity for the evolution of the education system | 0.631 | <0.001 |

| The sudden use of distance education due to the pandemic caused me negative emotions such as anxiety, worry. | -0.489 | <0.001 |

| Social isolation from my classmates and teachers makes me depressed | -0.383 | <0.001 |

| I consider distance education to be more effective than face-to-face education | 0.672 | <0.001 |

| The pandemic and the sudden implementation of distance education cause me fear of extending my studies | -0.359 | <0.001 |

| The new conditions, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, lead me to thoughts of dropping out of my studies | -0.114 | 0.035 |

| I'm concerned about the progress of my score in distance education | -0.327 | <0.001 |

| I'm worried about how I'm evaluated under the new educational conditions | -0.283 | <0.001 |

| I believe that the sudden transition from life to distance education will negatively affect my future career | -0.427 | <0.001 |

| Attitudes about Distance Education | p | p* | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree |

Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| From the beginning I felt able - or to meet the requirements of distance education due to my familiarity with electronic devices (tablet, smart phones, computer) | 2.25 | 0.72 | 2.58 | 0.87 | 2.64 | 0.88 | 2.78 | 0.95 | 3.06 | 0.98 | 0.016 | 0.063 |

| From the beginning I had the appropriate technological equipment to respond the needs of e-education (tablet, smart phones, computer) | 2.25 | 0.72 | 2.59 | 0.90 | 2.54 | 0.87 | 2.73 | 0.94 | 3.13 | 0.95 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| I encountered network connection problems while attending online courses during the pandemic | 3.18 | 1.07 | 3.16 | 1.04 | 2.84 | 0.89 | 2.65 | 0.86 | 2.62 | 0.98 | 0.007 | 0.001 |

| The educational institution where I study adequately covered my education needs during the transition from life to distance education.] | 1.82 | 0.88 | 2.19 | 0.86 | 2.71 | 0.86 | 3.02 | 0.84 | 3.45 | 1.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Conditions in my living environment (family, friendly, etc.) influenced the use of distance education during the pandemic | 3.15 | 1.03 | 2.98 | 0.90 | 2.80 | 0.88 | 2.64 | 0.92 | 2.46 | 1.05 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| My teachers cover my education needs in the implementation of distance education in the pandemic period | 1.80 | 0.74 | 2.24 | 0.96 | 2.57 | 0.88 | 3.05 | 0.83 | 3.23 | 1.00 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| The interaction with my teachers was different due to the transition to distance education | 3.68 | 0.89 | 3.06 | 1.00 | 2.97 | 1.01 | 2.88 | 0.89 | 2.39 | 0.86 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| I deal with my education obligations in distance education with self-discipline | 3.02 | 1.15 | 2.34 | 0.85 | 2.62 | 0.88 | 2.90 | 0.93 | 3.07 | 1.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

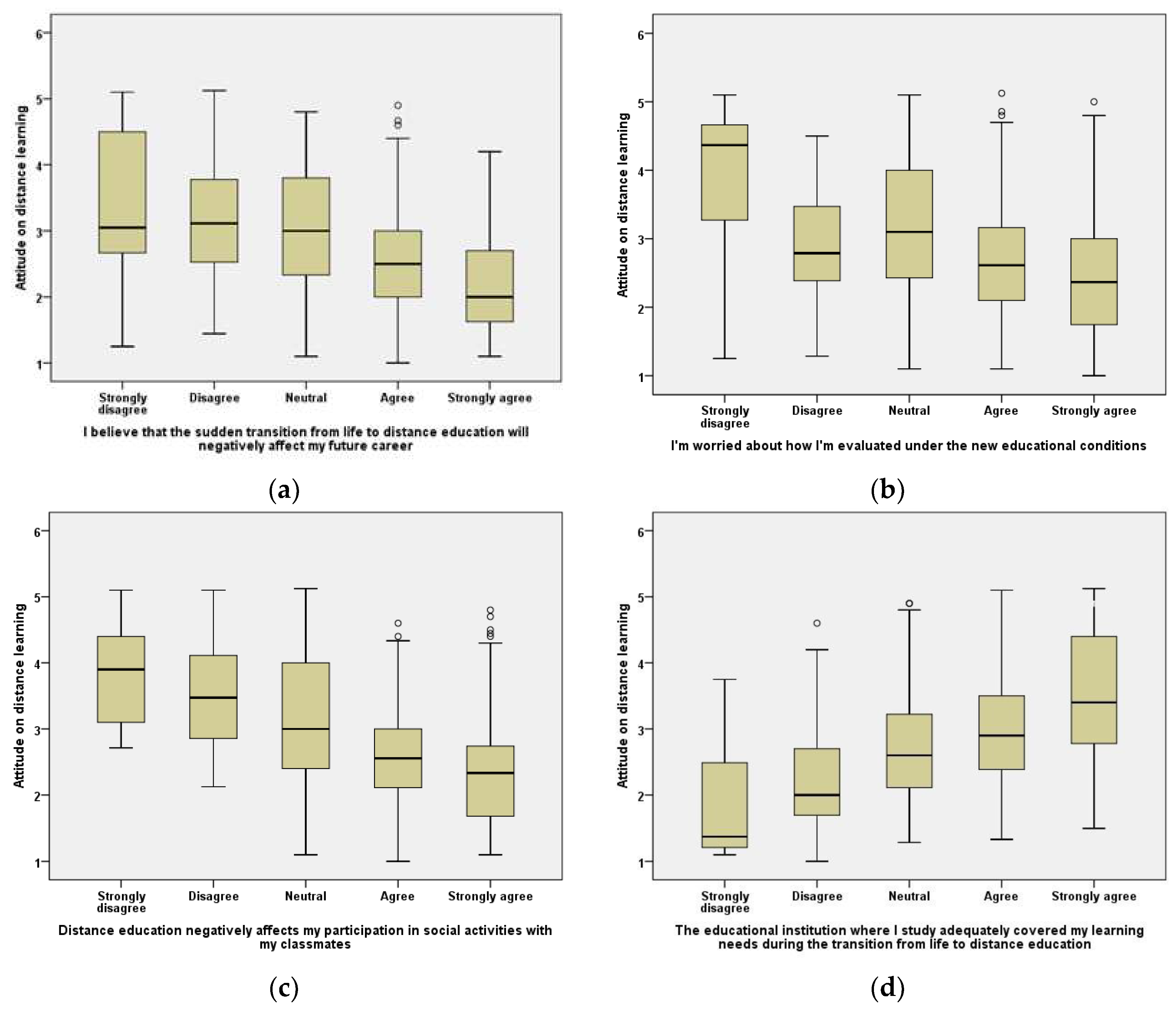

| Distance education negatively affects my participation in social activities with my classmates | 3.87 | 0.86 | 3.54 | 0.86 | 3.08 | 1.03 | 2.63 | 0.72 | 2.37 | 0.89 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Distance education prevents me from doing group work with my classmates | 3.40 | 0.81 | 3.29 | 0.98 | 3.04 | 0.93 | 2.58 | 0.76 | 2.21 | 0.91 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Distance education facilitates my professional, family, educational obligations because it provides me with flexibility | 2.04 | 0.77 | 2.17 | 0.58 | 2.57 | 0.72 | 3.10 | 0.94 | 3.70 | 0.89 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| I believe that the application of distance education exclusively has been the occasion for the development of some of my skills | 2.03 | 0.83 | 2.39 | 0.65 | 2.74 | 0.76 | 3.26 | 0.92 | 3.68 | 1.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| I believe that the transition from living to distance education has been an opportunity for the evolution of the education system | 1.84 | 0.62 | 2.30 | 0.52 | 2.64 | 0.71 | 3.21 | 0.77 | 3.95 | 1.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| The sudden use of distance education due to the pandemic caused me negative emotions such as anxiety, worry. | 3.90 | 0.90 | 3.23 | 0.86 | 2.99 | 0.80 | 2.62 | 0.80 | 2.17 | 0.79 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Social isolation from my classmates and teachers makes me depressed | 3.70 | 1.05 | 2.90 | 0.86 | 2.68 | 0.84 | 2.52 | 0.70 | 2.15 | 0.91 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| I consider distance education to be more effective than face-to-face education | 2.14 | 0.64 | 2.82 | 0.63 | 3.57 | 0.75 | 4.08 | 0.71 | 3.69 | 1.54 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| The pandemic and the sudden implementation of distance education cause me fear of extending my studies | 3.83 | 1.25 | 3.02 | 0.97 | 3.18 | 0.86 | 2.72 | 0.82 | 2.34 | 0.83 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| The new conditions, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, lead me to thoughts of dropping out of my studies | 2.89 | 0.98 | 2.75 | 0.86 | 2.46 | 0.93 | 2.46 | 0.95 | 2.95 | 1.14 | 0.101 | 0.106 |

| I'm concerned about the progress of my score in distance education | 3.52 | 1.22 | 3.16 | 0.90 | 2.84 | 0.93 | 2.61 | 0.84 | 2.36 | 0.85 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| I'm worried about how I'm evaluated under the new educational conditions | 3.89 | 1.11 | 2.91 | 0.78 | 3.15 | 1.00 | 2.68 | 0.85 | 2.45 | 0.93 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| I believe that the sudden transition from life to distance education will negatively affect my future career | 3.44 | 1.09 | 3.14 | 0.84 | 3.05 | 0.93 | 2.55 | 0.80 | 2.16 | 0.72 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).