1. Introduction

Actinobacteria are characterized by high ecological plasticity, labile enzymatic systems, powerful and complex secondary metabolism [

1,

2]. According to studies of actinobacterial prevalence and species diversity, cultures of the genus

Streptomyces account for 80-95% of all

Actinobacteria that inhabit soil, and among known bioactive microbial secondary metabolites, the vast majority are produced by

Actinobacteria, 80% of which belong to the genus

Streptomyces [

3].

The genus

Streptomyces includes spore-forming, filamentous and gram-positive

Actinobacteria [

4,

5], which inhabit different environments, such as extreme conditions and poorly studied habitats, terrestrial and marine ecosystems, symbionts, endophytes, etc. Representatives of the genus

Streptomyces are characterized by the ability to survive under adverse environmental conditions, while retaining metabolic activity for a long time, and to degrade natural and synthetic substances, possessing enzymes with a wide substrate specificity. These bacteria produce a huge variety of chemical structures (polyketides, peptides, macrolides, indoles, aminoglycosides, terpenes, etc.) [

6,

7,

8], through which they exert regulatory effects on the plant and control development of phytopathogens [

9].

Representatives of

Streptomyces genus can affect phytopathogens directly by producing antibiotics, siderophores, hydrolytic or detoxifying enzymes, either or indirectly by stimulating host plant growth through synthesis of phytohormones, increasing their resistance to diseases, forming mechanisms of induced and/or acquired system resistance or simply by competing with phytopathogens for available nutrition elements [

10,

11].

The functions of genes annotated in genomes are currently poorly understood and require further comprehensive studies [

12]. Using in silico genome analysis methods, Streptomyces genomes have been found to contain 25-70 biologically active compounds (BACs), but only a small fraction of these BACs is synthesized in the laboratory using culturing methods [

13]. Modern sequencing methods pose serious computational problems due to the short lengths of the sequenced fragments and the large volume of data, which especially affects the functional annotation of the genomes of

Streptomyces strains, since the latter contain many proteins with repeats, multiblock structures such as polyketide synthases, non-ribosomal peptide synthases (NRPS) and serine threonine kinases [

14,

15].

For example, the genome of S

. clavuligerus strain contains many gene clusters of secondary metabolites such as staurosporine [

16], moenomycin [

17], terpenes, pentalenes, phytoenes, siderophores and lantibiotics [

18]. An annotation of

Streptomyces sp. strain BRB081 identified desferrioxamines, fatty acid amides, diketopiperazines, xanthurenic acid, cyclic octapeptides surugamides. Comparative analysis of amino acid sequences showed that 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) deaminases of representatives of the

Actinomycetota phylum form a separate phylogenetic cluster [

19]. Analysis of

S. avermitilis genome revealed the capability of polyketide synthesis [

20].

The genomes of

Streptomyces strains include large unknown clusters of biosynthetic genes, making them a potential repository for the discovery of biotechnologically valuable compounds. Given the high degree of polymorphism of

Streptomyces, it is undoubtedly important, from a scientific and practical point of view, to study the level of specificity and biological activity of

S. carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993 [

21]. The aim of this work is the study of genome organization and metabolic potential of

Streptomyces carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993, promising plant-protecting and plant-stimulating strain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genome Analysis

The genome of the strain was sequenced and completely assembled [

22]. The genome was annotated with the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) version 4.6 [

23], Prokka [

24], and RAST [

25]. The whole-genome tree was built using the TYGS web service [

https://tygs.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 1 May 2023)]. The genomic map was built using the Proksee.ca web service (accessed on May 1, 2023) [

26]. ANI value was calculated using the Ezbiocloud service (accessed on May 1, 2023) [

27], DDH value using the Genome-to-Genome distance calculator [

28]. Chromosome alignment was performed using Mauve ver. 2.4.0 (2014-12-21) [

29]. Pangenome analysis and search for unique genes was performed using OrthoVenn [

30]. A search for clusters of secondary metabolite production was performed with AntiSmash [

31]. Functional analysis based on metabolic and regulatory pathways was performed using KEGG [

32]. SNP searches were performed using Nucmer from the Mummer package [

33].

2.2. Cultivation of the Strain

The strain S. carpaticus SCPM-O-B-9993 was grown in liquid starch-casein medium for 168 hr at 28°C with continuous stirring on a shaker (80 rpm). The strain was seeded by adding to 1 liter of starch-casein medium a fragment of seven-day-old colonies of the strain with air and substrate mycelium on dense medium of the same composition with an area of 1 cm2. The suspension of the strain is a homogeneous liquid containing cells, mycelium, and spores. During 7-day cultivation every 24 hr, the aliquot of cultivation medium with cells was plated on solid starch-casein medium to check the purity of the culture. The optical density of the suspension was measured, and at 340 nm using a spectrophotometer, and the suspension was taken for investigation of its phytostimulatory and antiviral activity. The strain cells were microscopically examined and photographed using an Amplival (Zeiss) microscope with a photomask.

2.3. Determination of Phytotoxicity

Phytotoxicity of the SCPM-O-B-9993 strain suspension was studied by the wet cell method using seeds of Ducat cress. Each Petri dish was bottomed with a circle made of filter paper, 30 seeds of cress were placed on it, then 5 ml of suspension was introduced (distilled water was used as a control). The dishes were exposed at 20 °C for 3 days. The experiment was performed in two replicates. Then, germination was calculated, root length and stem height of seedlings were measured.

2.4. Study of Antiviral Activity

To study the prolonged antiviral activity of the SCPM-O-B-9993 strain suspension against cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), we infected 10 plants of LoJain tomato at the 3-4 true leaf stage by applying inoculum obtained by pestle rubbing of phytovirus-infected plants on the leaf plates. Farmayod, 10% (NPC Farmbiomed, Moscow) was used as a reference in the positive control (K+). Farmayod aqueous solution for plants was prepared just before use: 3-5 g of concentrate / 10 liters of water. Distilled water was used as a negative control (K-). Treatment method in K+, K- and experimental variants was spraying. Background watering of plants (sprinkling under the root) was carried out with tap water once in the morning hours in all experimental variants. During the whole period of the experiment, two antiviral treatments were performed on the 7th and 12th days after infection. Control plants (K-) were sprayed with tap water. On 3 days after the second spraying, the presence of viruses in plants was determined by immunochromatographic method on ImmunoStrip Test Kit Flashkits (USA) on each plant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Features of the Strain

Strain

S. carpaticus SCPM-O-B-9993 was isolated from brown semi-desert soils with a very high degree of salinity in the Astrakhan Region of the Russian Federation. The strain has dark brown aerial mycelium and cherry-red substrate mycelium (

Figure S1). The optimal growth temperature is 28°C. Optimal pH is 7.0-7.1. Sporocysts are straight or twisted, short. Spores are oval or globular with a dense shell, 0.5-1.0×1.0-1.1 µm in size.

3.2. Taxonomic Positioning of the Strain SCPM-O-B-9993

Strain SCPM-O-B-9993 is the only representative of the

S. carpaticus species whose genome has been completely sequenced [

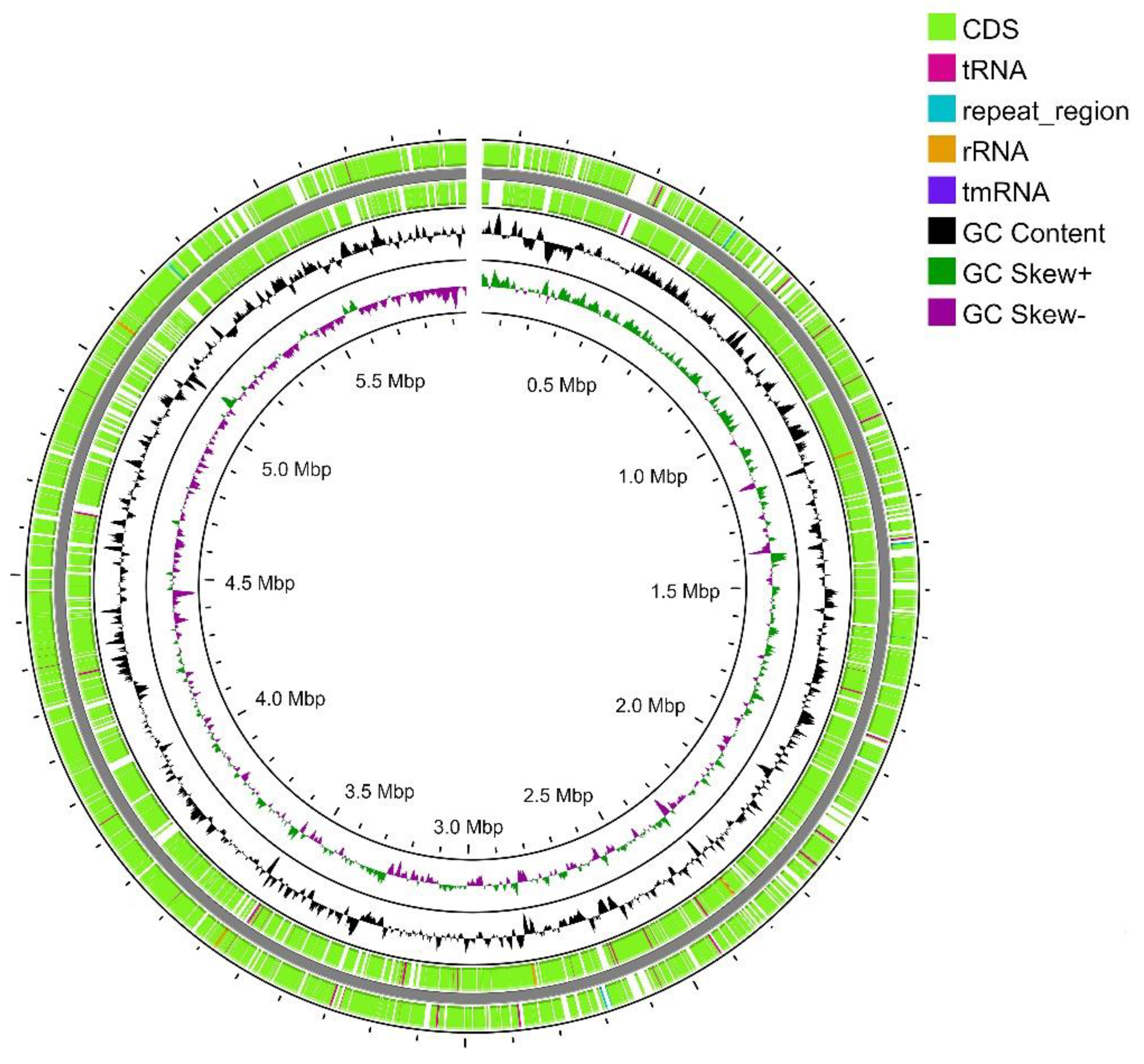

22]. The genome assembly consisted of a single linear chromosome of 5,968,715 bp GC composition of 72.84% (

Figure 1). No plasmids were detected. During genome annotation and analysis, 5206 protein-coding sequences, 60 tRNA sequences, 15 rRNA sequences (5 - 5S, 5 - 16S, 5 - 23S) and 8 CRISPR loci were identified.

To determine its closest relatives among

Streptomyces strains with completely sequenced genomes, a BLAST search for housekeeping gene sequences (

gyrB,

rpoB,

trpB,

recA) was performed (

Table S1).

Streptomyces harbinensis NA02264,

Streptomyces xiamenensis 318 and

Streptomyces sp. XC2026 were found to be most closely related to strain SCPM-O-B-9993 (

Table 1).

The strains SCPM-O-B-9993 and NA02264 are listed in the Genbank database as representatives of different species. However, ANI value and DDH values show that these strains are very likely to belong to the same species (

Table 2). Thus, the threshold for species assignment by DDH is 70%, while strains SCPM-O-B-9993 and NA02264 have DDH values >90%.

The genome of the type strain

S. carpaticus has not been sequenced to date (July 2023). However, the genome of the type strain

S. harbinensis CGMCC4.7047T (FPAB000000000000.1) has been sequenced, which makes it possible to calculate the main parameters of species membership (

Table 3).

Considering that the ANI value and DDH value of strain SCPM-O-B-9993 relative to the type strain of S. harbinensis exceed the thresholds for species assignment (ANI > 95% and DDH > 70%), we assume that strain SCPM-O-B-9993 is probably a representative of the species S. harbinensis, but the final taxonomic position of the strain will be possible only after the genome sequence of the type strain of S. carpaticus appears in the Genbank database.

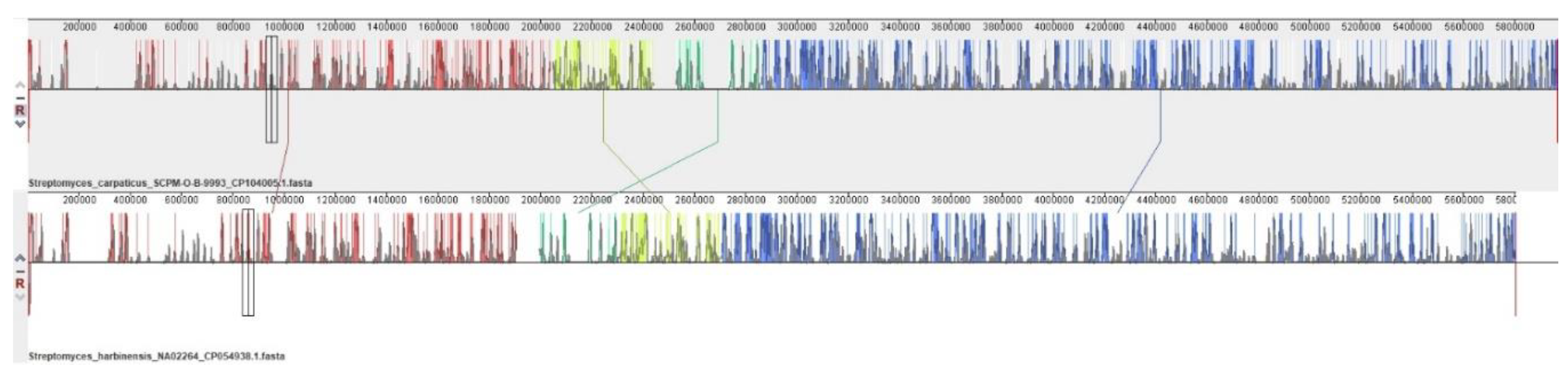

The alignment of the genomes of

Streptomyces carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993 and

Streptomyces harbinensis strain NA02264 (

Figure 2) relative to each other shows that the main blocks (marked with one color) retain a similar arrangement on the chromosomes, and, in general, the structure of the genomes is very similar. Only a few displacements of gene blocks can be noted (marked with vertical bars).

In the S. harbinensis NA02264 genome relative to the S. carpaticus SCPM-O-B-9993 genome, 20,153 single nucleotide substitutions (SNPs) were found, which are evenly dispersed throughout the genome. Single nucleotide substitutions accounted for 0.34% of the total genome length.

3.3. Analysis of the Pangenome of Streptomyces Carpaticus Strain SCPM-O-B-9993 and Its Closest Relatives

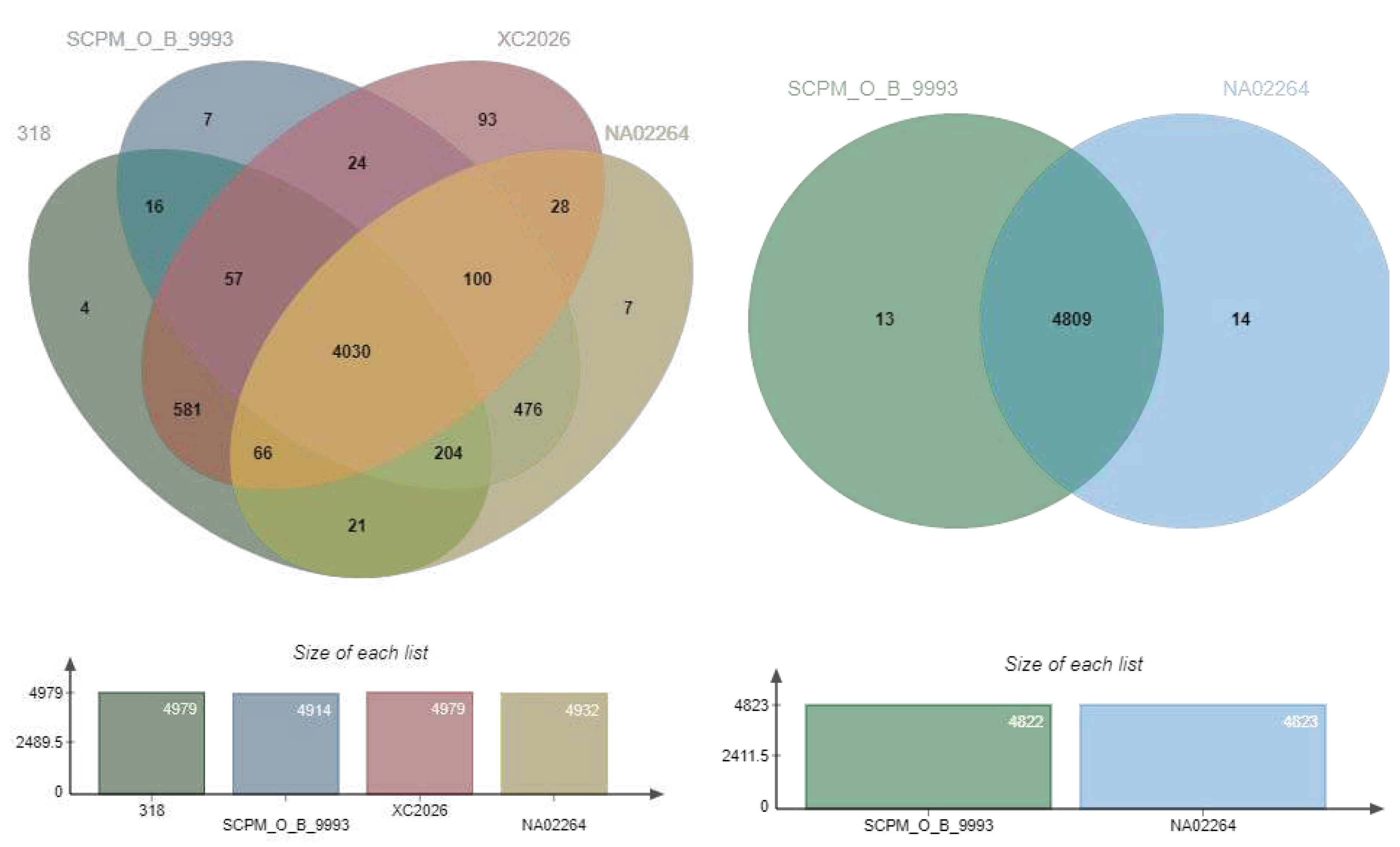

We analyzed the pangenome of the strains listed in

Table 1 as the closest relatives of strain SCPM-O-B-9993 (

Figure 3A), and separately the pangenome of the pair

Streptomyces carpaticus SCPM-O-B-9993 and

Streptomyces harbinensis NA02264 (

Figure 3B), as the strains closest to each other among the

Streptomyces whose genomes were sequenced. It was of interest to identify whether these two strains, whose genomes are nearly identical in structure, have genes that are unique relative to each other.

The pangenome of 4

Streptomyces strains is represented by 5,714 CDSs, of which 4,030 CDSs (70.5%) are core. Expectedly, the SCPM-O-B-9993/NA02264 pair had the maximum (of all pairs with strain SCPM-O-B-9993) number of CDSs unique to the pair: 476 CDSs are characteristic only for this pair and absent in the other strains (

Table S2).

The pangenome of the Streptomyces carpaticus SCPM-O-B-9993 and Streptomyces harbinensis NA02264 pair is represented by 4,836 genes, of which 4,809 (99.4%) are core. Despite the close relatedness, each strain has unique CDSs, but most of them cannot be classified at this time.

3.4. Functional Annotation of Streptomyces Carpaticus Strain SCPM-O-B-9993

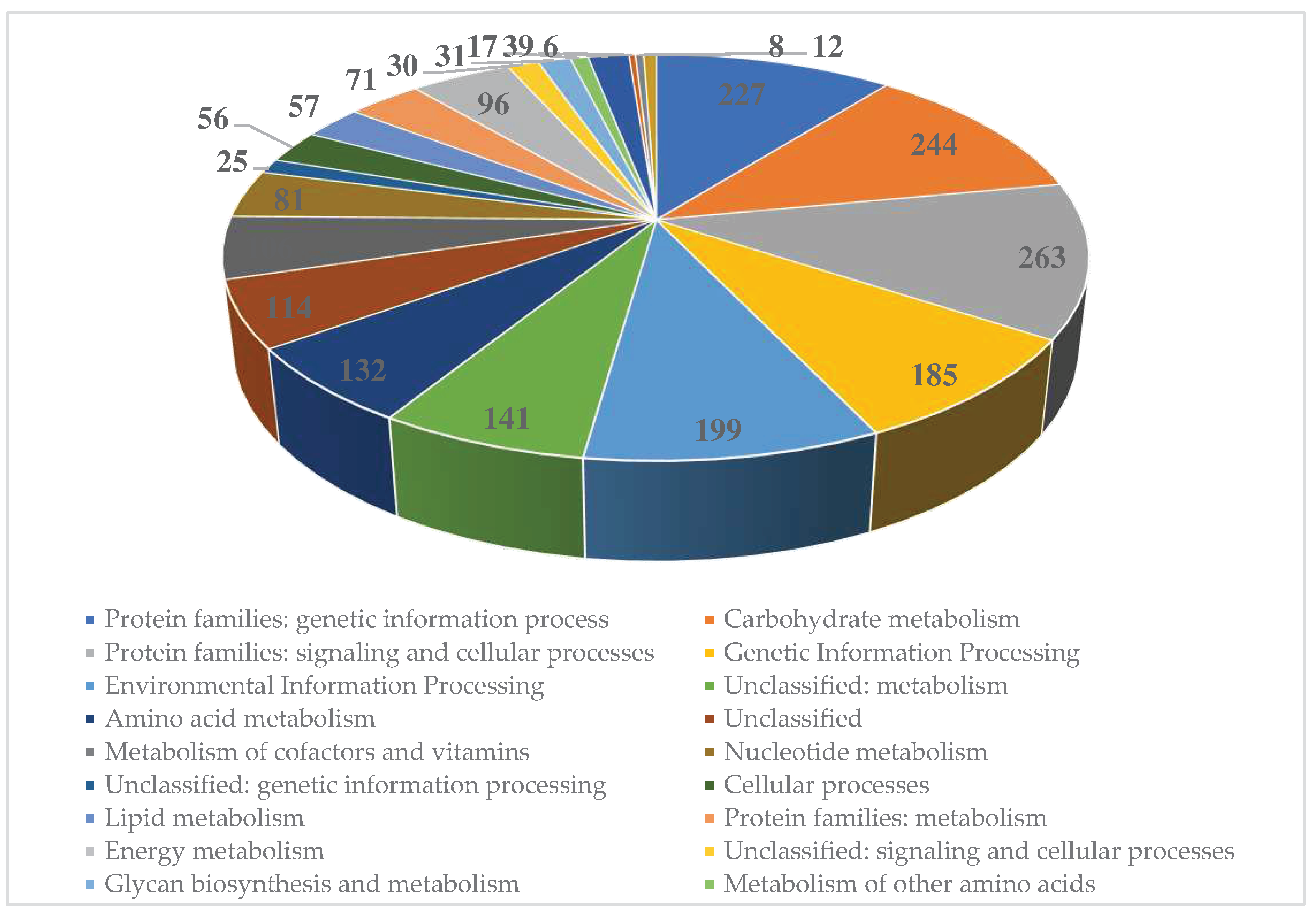

The genome of strain SCPM-O-B-9993 contains 5,331 coding sequences, of which 2,139 (40.1%) are functionally annotated (

Figure 4).

Since the strain SCPM-O-B-9993 is a biotechnologically promising producer of secondary metabolites, the genetic organization of secondary metabolite production clusters was analyzed.

The starting unit in the biosynthesis of ansamycin antibiotics by streptomycetes is 3-amino-5-hydroxybenzoic acid (AHBA) [

34]. The genome of strain SCPM-O-B-9993 contains a sequence of genes whose products control the pathway of AHBA biosynthesis from UDP-glucose, consisting of 10 reactions. The terpenoid biosynthesis pathway in the genome of strain SCPM-O-B-9993 involves the creation of key metabolites such as isopentenyl pyrophosphate, geranyl-PP, farnesyl-PP, and geranyl-geranyl-PP, which are precursors of many secondary metabolites in

Streptomyces.

We found the following highly conserved secondary metabolite production clusters in the strain genome (>80% structural similarity to similar clusters in other strains) (

Table 4).

The organization of the coelibactin gene cluster in strain SCPM-O-B-9993 is completely identical to that of

S. harbinensis (

Figure S2E). Differences between them are present mainly at the level of single nucleotide substitutions (SNPs), except for a few extended regions (

Table S3).

The antimicrobial properties of the strain may be due to the production of ohmyungsamycin, pellasoren, and naringenin. Ohmyungsamycins are cyclic peptides first isolated from marine

Streptomyces [

35,

36]. They are synthesized by a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase. Kim et al [

37] observed their activity against

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and cancer cells in humans, with OMS A showing greater activity than OMS B. Considering that strain SCPM-O-B-9993 possesses the Ohmyungsamycin production gene cluster, it can be considered as promising in medicine too.

Previously, naringenin biosynthesis was thought to be characteristic only of plants [

38,

39]. Naringenin is a flavonoid whose biosynthesis has been repeatedly reported in citrus trees (lemons, oranges etc) and tomatoes [

40]. Álvarez-Álvarez et al [

41] first showed its biosynthesis in

Streptomyces clavuligerus. Naringenin has antiinflammatory, chemoprotective and antitumor properties [

42,

43].

The best-known producer of pellasoren is

Sorangium cellulosum [

44]. However, the gene cluster for the biosynthesis of this compound is found in the genomes of

Streptomycetes, particularly in the type strain

S. harbinensis (

Figure S2). Nothing is known about the antimicrobial properties of pellasoren, but it has been reported that this compound has cytotoxic effects against cancer cells [

45,

46].

The study of the component composition of suspension and extracts (water-alcohol, methanol and hexane) of

S. carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993 showed the presence of secondary metabolites - alcohols, aldehydes, hydrocarbons, esters, sulfates and other groups of low-molecular-weight organic compounds (LMCs). At all variants of extraction, alcohols and esters prevailed in the composition of LMCs. The identified LMCs have valuable properties from the agricultural point of view: antiviral, antimicrobial and antitumor (ethyl 5-(pyridin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazol-3-carboxylate); bactericidal, fungicidal and antiseptic properties (1,2-hexanediol); insectoacaricidal (isopropyl myristate). 1-Dodecanol is included in pheromones, sex attractants and surfactants for controlling insect pests [

21].

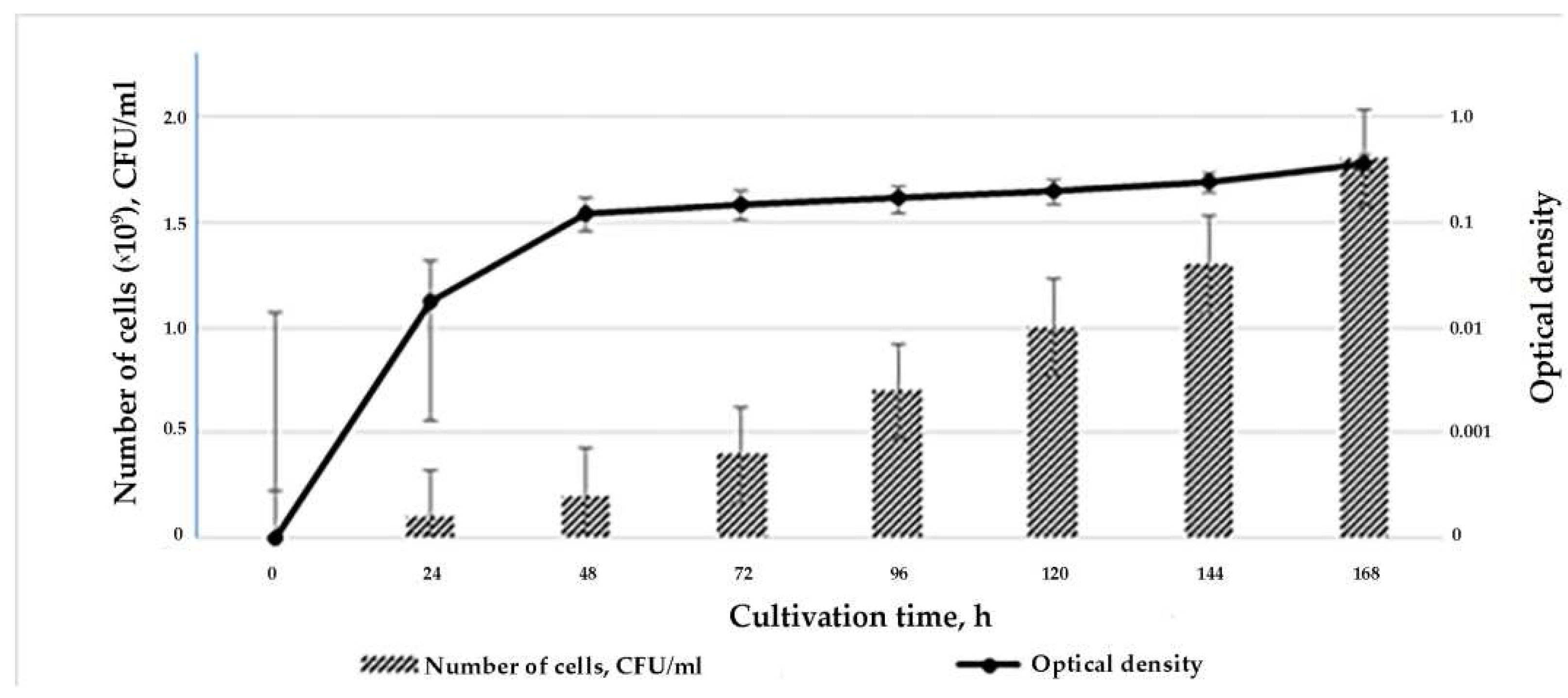

3.5. Evaluation of Productivity, Phytostimulatory and Antiviral Properties of the Strain

During the first 12 hours of growth, the strain is in the lag phase when the cells are adapting to the nutrient medium. The cells and mycelium enter the exponential growth phase by 12 - 24 hours. At this time strain SCPM-O-B-9993 actively produces metabolites, cells multiply, their number increases to 2.0*10

9 CFU/mL. From 48 hours of exposure, the culture begins to enter the stationary growth phase and remains in it for five days. Decrease in abundance does not occur even on the seventh day. The optical density changed in accordance with the growth of strain biomass (

Figure 5).

When studying the effect of suspension of strain SCPM-O-B-9993 on cress seeds, toxic effect on germination of 4-day, 7-day cultures and positive control Farmayod was found (

Table S4). Toxic effect was observed in germination of less than 30% of seeds. It should be noted that the concentration of cells, spores, mycelium and the amount of metabolites in the suspension cultivated in laboratory conditions in liquid nutrient medium increases with the increase of cultivation period, which increases the toxicity of the suspension. But it should be taken into account that bacteria entering natural conditions in plant treatments, at a concentration of 10

9 CFU/mL, are distributed in the soil or on plants in lower numbers than when they are in laboratory flask conditions, due to lack of substrate, environmental factors, etc. In addition, when microorganisms enter the soil, a microbial pool is formed, which further leaves the number of cells no more than 10

4 CFU/mL.

The highest root length was found when treated with 3-day suspension of the strain 23.89 mm. The cultivation period of the strain influenced the growth of cress, 1, 2, 6, 7-day cultures had an inhibitory effect on root and shoot growth. It is quite natural that 6- and 7-day old cultures inhibited plant growth because of the accumulation of metabolites at this stage.

The data indicate that

S. carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993 has antiviral activity against CMV on tomatoes under laboratory conditions relative to positive and negative controls (

Table 5). When comparing the antagonistic properties of the strain suspension by hours of cultivation, it was found that the maximum antiviral activity was exhibited by 3-day suspensions of the strain: all treated plants were symptom-free of the virus. Thus, 3-day cultivation of the strain is optimal, as the suspension showed effective phytostimulatory properties, and at the same time had an inhibitory effect on CMV. The study of secondary metabolites of the 3-day suspension of the strain showed the presence of alcohols, aldehydes, hydrocarbons, esters, sulfates and other groups of low molecular weight organic compounds with high biological activity [

21].

Suspensions of the strain at 24 and 48 hours of cultivation were completely ineffective against phytovirus. It was found that 4-day and 5-day suspensions of the strain continued to show antiviral activity, but it was insignificantly lower than that of 3-day suspensions. The antiviral activity of the 6- and 7-day suspensions of the strain was approximately 50%.

4. Conclusions

The studies revealed clusters of production of secondary metabolites of the strain SCPM-O-B-9993: terpenoids and ansamycin antibiotics. Under laboratory conditions, the strain exhibited phytostimulatory and antiviral properties. The most effective cultivation period of the strain was 72 hours, in which the culture went from exponential to stationary growth phase with the production of a spectrum of bioactive metabolites.

Genome analysis is a promising field that emphasizes microbial biosynthesis pathways, facilitating the search for active metabolites. Currently, there is no alternative to genome analysis to make a rapid search for new metabolites, including terpenes and antibiotics. Thus, Streptomyces carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993 is a biotechnologically promising producer of secondary metabolites with important properties.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1. Appearance of colonies of S. carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993 on potato agar on the 14th day of cultivation; Table S1. Search for strains most related to strain SCPM-O-B-9993 using marker genes (housekeeping genes); Table S2. Distribution of coding sequences unique to the SCPM-O-B-9993/NA02264 pair by biological processes; Figure S2. Schemes of genetic organization of highly conserved clusters of secondary metabolite biosynthesis; Table S3. Regions in conserved clusters of secondary metabolite biosynthesis containing extended mismatched regions; Table S4. Phytotoxicity of S. carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.B.; methodology, Y.B., Y.D. and L.G.; software, Y.D.; validation, Y.B. and A.B.; formal analysis, Y.D., and A.B.; investigation, L.S. and L.G.; resources, A.B.; data curation, Y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D. and Y.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B.; visualization, Y.D.; supervision, Y.B.; project administration, Y.B. and L.G.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, grant number 075-15-2019-1671 (agreement dated 31 October 2019).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data on genome sequence of the strain S. carpaticus strain SCPM-O-B-9993 can be found in Genbank database under the accession number CP104005.1 (BioProject PRJNA269675, BioSample SAMN30493425).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, T.-L.; Huang, T.-W.; Wang, Y.-X.; Liu, C.-P.; Kirby, R.; Chu, C.-M.; Huang, C.-H. An Actinobacterial Isolate, Streptomyces sp. YX44, Produces Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics That Strongly Inhibit Staphylococcus aureus. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veselá, A.B.; Pelantová, H.; Šulc, M.; Macková, M.; Lovecká, P.; Thimová, M.; Pasquarelli, F.; Pičmanová, M.; Pátek, M.; Bhalla, T.C.; et al. Biotransformation of benzonitrile herbicides via the nitrile hydratase–amidase pathway in rhodococci. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 39, 1811–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodfellow, M.; Williams, S.T. ECOLOGY OF ACTINOMYCETES. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1983, 37, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadayat, K.; Sherpa, D.D.; Malla, K.P.; Shrestha, S.; Rana, N.; Marasini, B.P.; Khanal, S.; Rayamajhee, B.; Bhattarai, B.R.; Parajuli, N. Molecular Identification and Antimicrobial Potential of Streptomyces Species from Nepalese Soil. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Hwang, S.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.; Palsson, B.; Cho, B.-K. Mini review: Genome mining approaches for the identification of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters in Streptomyces. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1548–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapaz, M.I.; Cisneros, E.J.; Pianzzola, M.J.; Francis, I.M. Exploring the Exceptional Properties of Streptomyces: A Hands-On Discovery of Natural Products. Am. Biol. Teach. 2019, 81, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkka, M.; Hampp, R. Secondary Metabolites of Soil Streptomycetes in Biotic Interactions. In Secondary Metabolites in Soil Ecology. Soil Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 14, pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Zhan, X.; Mao, X.; Li, Y. The Application of Regulatory Cascades in Streptomyces: Yield Enhancement and Metabolite Mining. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokikh, I.G.; Ashikhmina, T.Y. Actinobacteria in protecting the environment from industrial pollution. Theor. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, J.; Mohammadipanah, F. Biotechnological application and taxonomical distribution of plant growth promoting actinobacteria. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurukonda, S.S.K.P.; Giovanardi, D.; Stefani, E. Plant Growth Promoting and Biocontrol Activity of Streptomyces spp. as Endophytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.D. Environmental and clinical antibiotic resistomes, same only different. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belknap, K.C.; Park, C.J.; Barth, B.M.; Andam, C.P. Genome mining of biosynthetic and chemotherapeutic gene clusters in Streptomyces bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, J.L.; Currie, C.R. Gene fragmentation in bacterial draft genomes: extent, consequences and mitigation. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 14–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenkov, I.N.; Shelyakin, P.V.; Nikolaeva, D.D.; Tutukina, M.N.; Sharapova, A.V.; Lednev, S.A.; Sarana, Y.V.; Gelfand, M.S.; Krechetov, P.P.; Koroleva, T.V. Data on the temporal changes in soil properties and microbiome composition after a jet-fuel contamination during the pot and field experiments. Data Brief 2023, 46, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Salas, J.; Méndez, C. Indolocarbazole antitumour compounds by combinatorial biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009, 13, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostash, B.; Doud, E.H.; Lin, C.; Ostash, I.; Perlstein, D.L.; Fuse, S.; Wolpert, M.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. Complete Characterization of the Seventeen Step Moenomycin Biosynthetic Pathway. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 8830–8841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.Y.; Jeong, H.; Yu, D.S.; Fischbach, M.A.; Park, H.-S.; Kim, J.J.; Seo, J.-S.; Jensen, S.E.; Oh, T.K.; Lee, K.J.; et al. Draft Genome Sequence of Streptomyces clavuligerus NRRL 3585, a Producer of Diverse Secondary Metabolites. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 6317–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangerina, M.M.P.; Furtado, L.C.; Leite, V.M.B.; Bauermeister, A.; Velasco-Alzate, K.; Jimenez, P.C.; Garrido, L.M.; Padilla, G.; Lopes, N.P.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V.; et al. Metabolomic study of marine Streptomyces sp.: Secondary metabolites and the production of potential anticancer compounds. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0244385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolev, S.A.; Zverkov, O.A.; Seliverstov, A.V.; Lyubetsky, V.A. Ribosome reinitiation at leader peptides increases translation of bacterial proteins. Biol. Direct 2016, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataeva, Y.V.; Grigoryan, L.; Kurashov, E.; Krylova, J.; Fedorova, E.; Iavid, E.; Khodonovich, V.; Yakovleva, L. Study of metabolites of Streptomyces carpaticus RCAM04697 for the creation of environmentally friendly plant protection products. Theor. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataeva, Y.V.; Grigoryan, L.N.; Bogun, A.G.; Kislichkina, A.A.; Platonov, M.E.; Kurashov, E.A.; Krylova, J.V.; Fedorenko, A.G.; Andreeva, M.P. Biological Activity and Composition of Metabolites of Potential Agricultural Application from Streptomyces carpaticus K-11 RCAM04697 (SCPM-O-B-9993). Microbiology 2023, 92, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 6614–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.R.; Enns, E.; Marinier, E.; Mandal, A.; Herman, E.K.; Chen, C.-Y.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Stothard, P. Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W484–W492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.-H.; Ha, S.-M.; Lim, J.; Kwon, S.; Chun, J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.-P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, A.C.E.; Mau, B.; Blattner, F.R.; Perna, N.T. Mauve: Multiple Alignment of Conserved Genomic Sequence With Rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Dong, Z.; Fang, L.; Luo, Y.; Wei, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhang, G.; Gu, Y.Q.; Coleman-Derr, D.; Xia, Q.; et al. OrthoVenn2: a web server for whole-genome comparison and annotation of orthologous clusters across multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W52–W58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Kloosterman, A.M.; Charlop-Powers, Z.; van Wezel, G.P.; Medema, M.H.; Weber, T. antiSMASH 6.0: improving cluster detection and comparison capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W29–W35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marçais, G.; Delcher, A.L.; Phillippy, A.M.; Coston, R.; Salzberg, S.L.; Zimin, A. MUMmer4: A fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.-G.; Yu, T.-W.; Fryhle, C.B.; Handa, S.; Floss, H.G. 3-Amino-5-hydroxybenzoic Acid Synthase, the Terminal Enzyme in the Formation of the Precursor of mC7N Units in Rifamycin and Related Antibiotics. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 6030–6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.S.; Shin, Y.-H.; Lee, H.-M.; Kim, J.K.; Choe, J.H.; Jang, J.-C.; Um, S.; Jin, H.S.; Komatsu, M.; Cha, G.-H.; et al. Ohmyungsamycins promote antimicrobial responses through autophagy activation via AMP-activated protein kinase pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, S.; Choi, T.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, S.K.; Oh, K.-B.; Shin, J.; Oh, D.-C. Ohmyungsamycins A and B: Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Cyclic Peptides Produced by Streptomyces sp. from a Volcanic Island. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 12321–12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Du, Y.E.; Ban, Y.H.; Shin, Y.-H.; Oh, D.-C.; Yoon, Y.J. Enhanced Ohmyungsamycin A Production via Adenylation Domain Engineering and Optimization of Culture Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Kim, S.H.; Bahk, S.; Vuong, U.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Do, H.L.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, W.S. Naringenin Induces Pathogen Resistance Against Pseudomonas syringae Through the Activation of NPR1 in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, S.; Hamid, S.; Yaseen, A.; Yatoo, A.M.; Ali, S.; Shamim, K.; Mahdi, W.A.; Alshehri, S.; Rehman, M.U.; Shah, W.A. Isolation and Characterization of Flavonoid Naringenin and Evaluation of Cytotoxic and Biological Efficacy of Water Lilly (Nymphaea mexicana Zucc.). Plants 2022, 11, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-H.; Lin, C.; Lin, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Wu, C.Y.-J.; Tsai, C.-F.; Chang, P.-C.; Yeh, W.-L.; Lu, D.-Y. Naringenin Suppresses Neuroinflammatory Responses Through Inducing Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 Expression. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 53, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Álvarez, R.; Botas, A.; Albillos, S.M.; Rumbero, A.; Martín, J.F.; Liras, P. Molecular genetics of naringenin biosynthesis, a typical plant secondary metabolite produced by Streptomyces clavuligerus. Microb. Cell Factories 2015, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavia-Saiz, M.; Busto, M.D.; Pilar-Izquierdo, M.C.; Ortega, N.; Perez-Mateos, M.; Muñiz, P. Antioxidant properties, radical scavenging activity and biomolecule protection capacity of flavonoid naringenin and its glycoside naringin: a comparative study. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagetia, A.; Jagetia, G.C.; Jha, S. Naringin, a grapefruit flavanone, protects V79 cells against the bleomycin-induced genotoxicity and decline in survival. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2006, 27, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahns, C.; Hoffmann, T.; Müller, S.; Gerth, K.; Washausen, P.; Höfle, G.; Reichenbach, H.; Kalesse, M.; Müller, R. Pellasoren: Structure Elucidation, Biosynthesis, and Total Synthesis of a Cytotoxic Secondary Metabolite fromSorangium cellulosum. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5239–5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbassi-Ghanavati, M.; Alexander, J.M.; McIntire, D.D.; Savani, R.C.; Leveno, K.J. Neonatal Effects of Magnesium Sulfate Given to the Mother. Am. J. Perinatol. 2012, 29, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaita, S.; Phakhodee, W.; Chairungsi, N.; Pattarawarapan, M. Mechanochemical synthesis of primary amides from carboxylic acids using TCT/NH4SCN. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 3571–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).