Submitted:

08 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

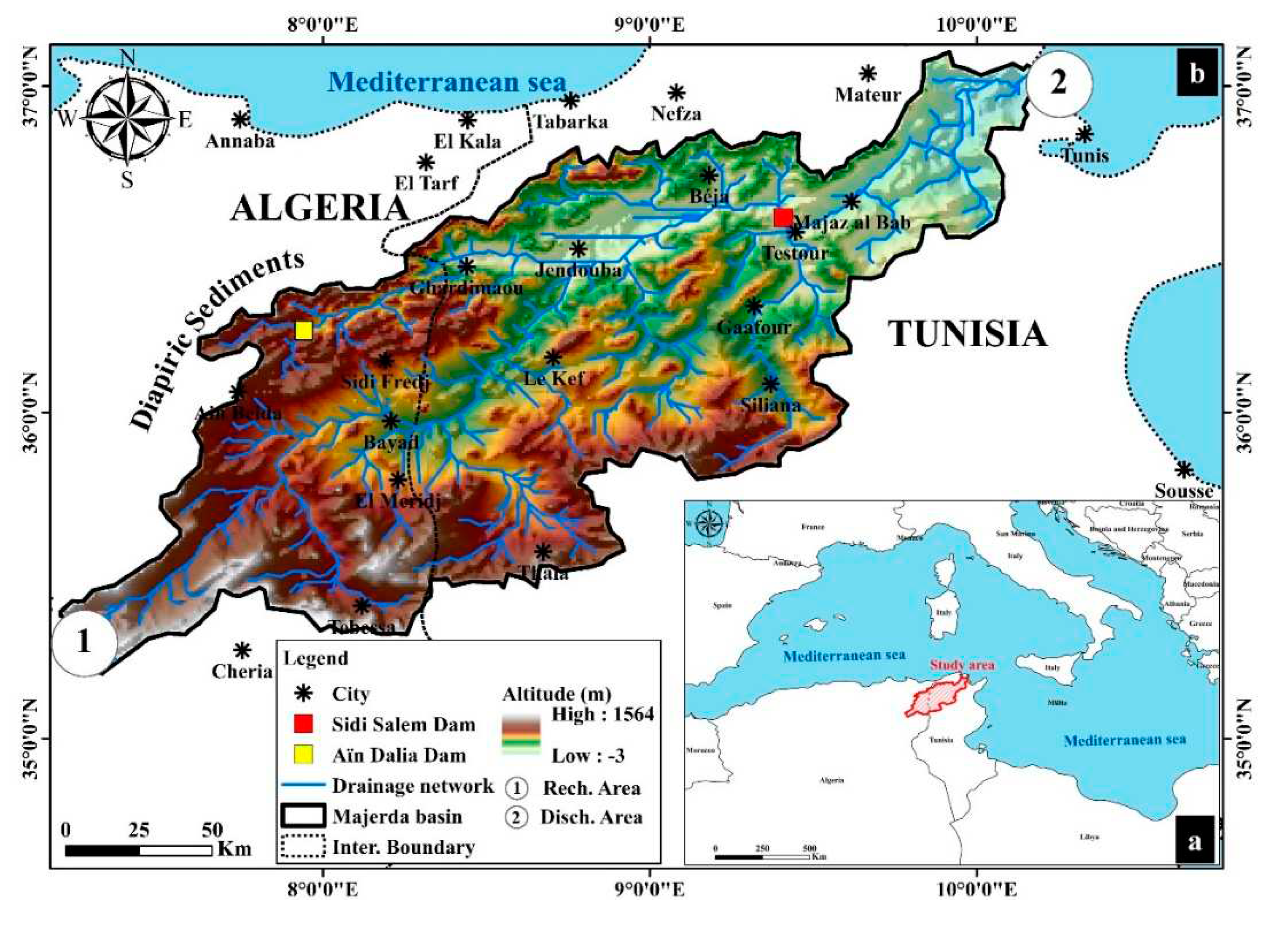

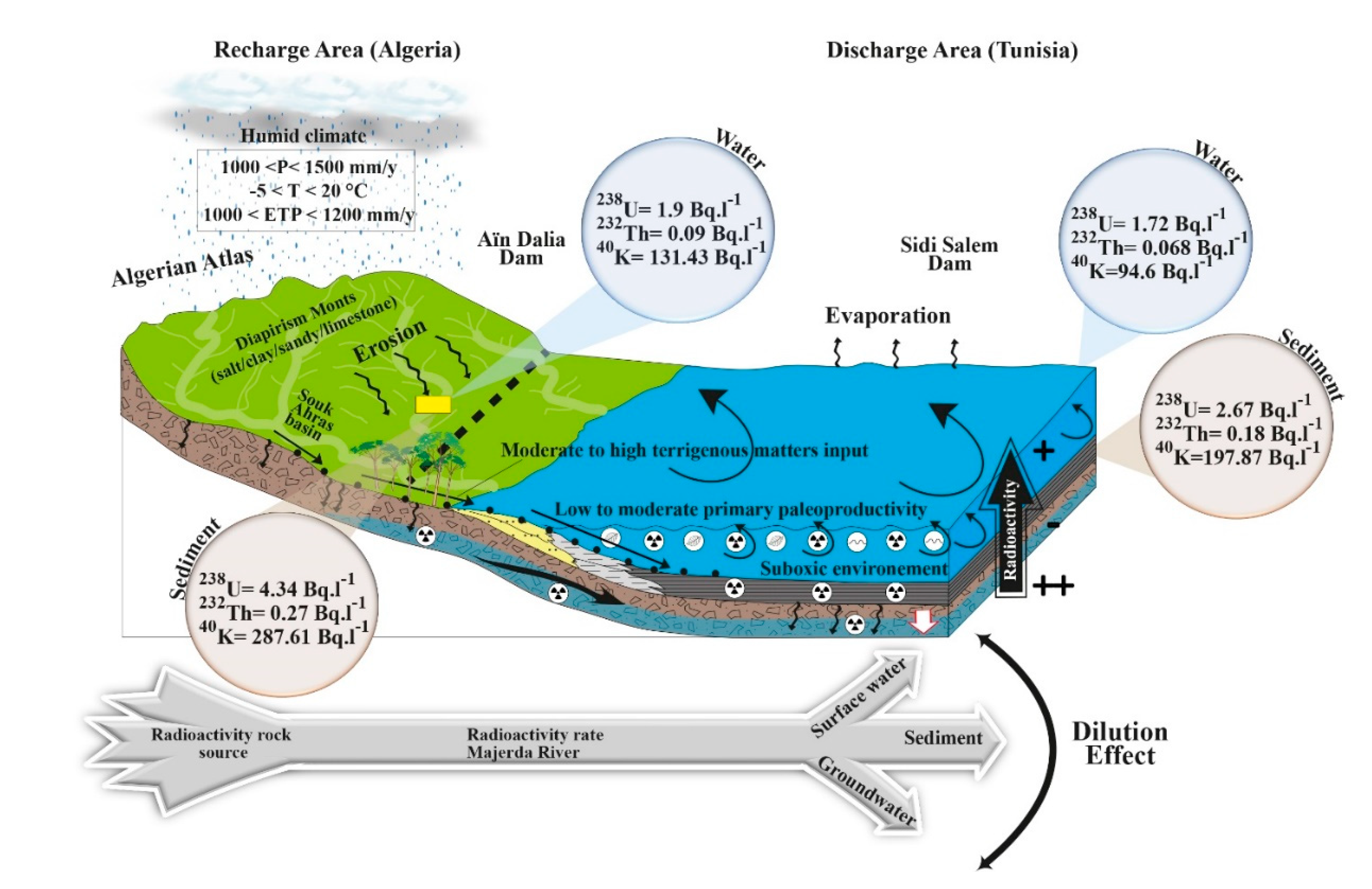

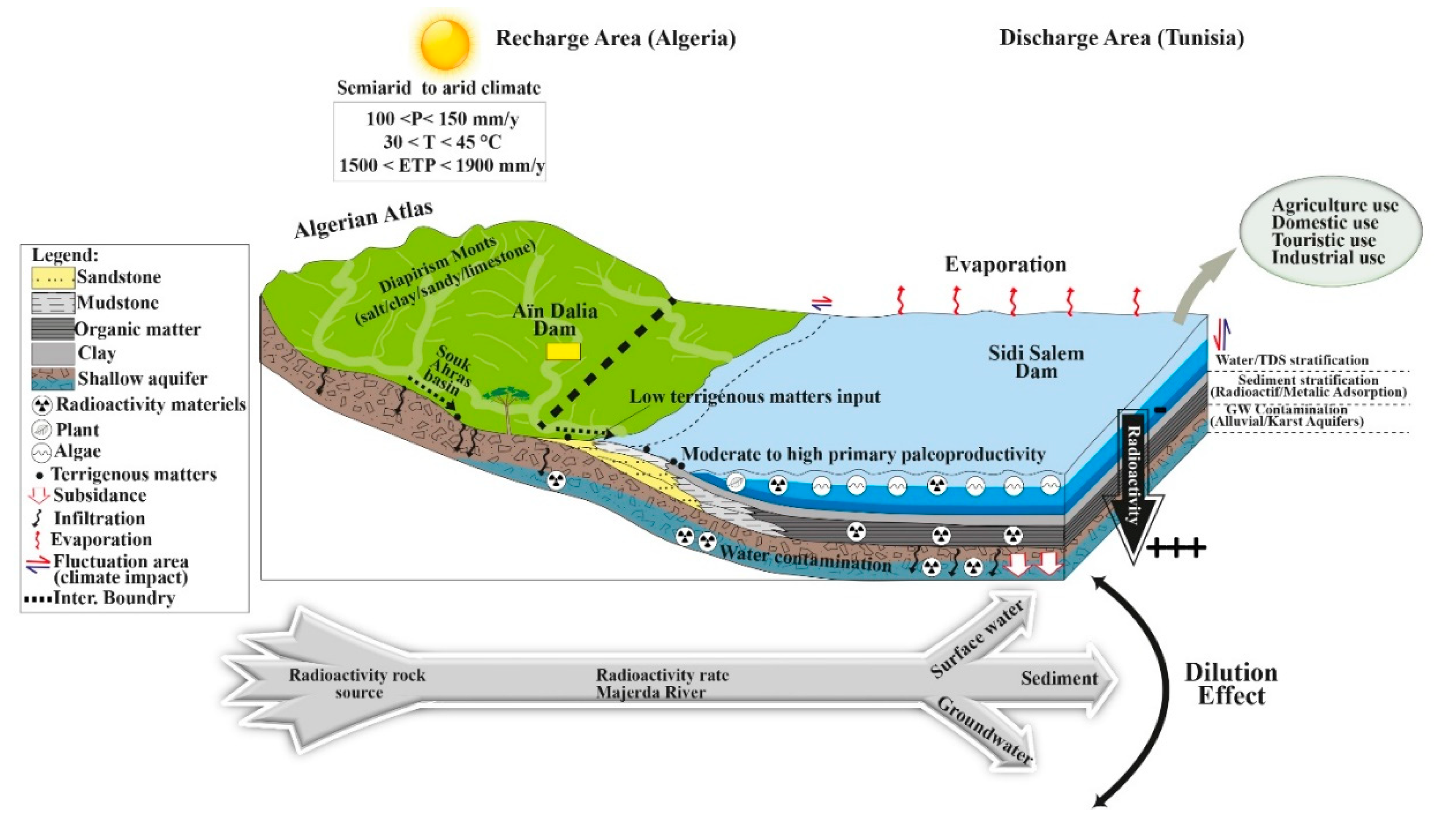

2. Study area

3. Materials and methods

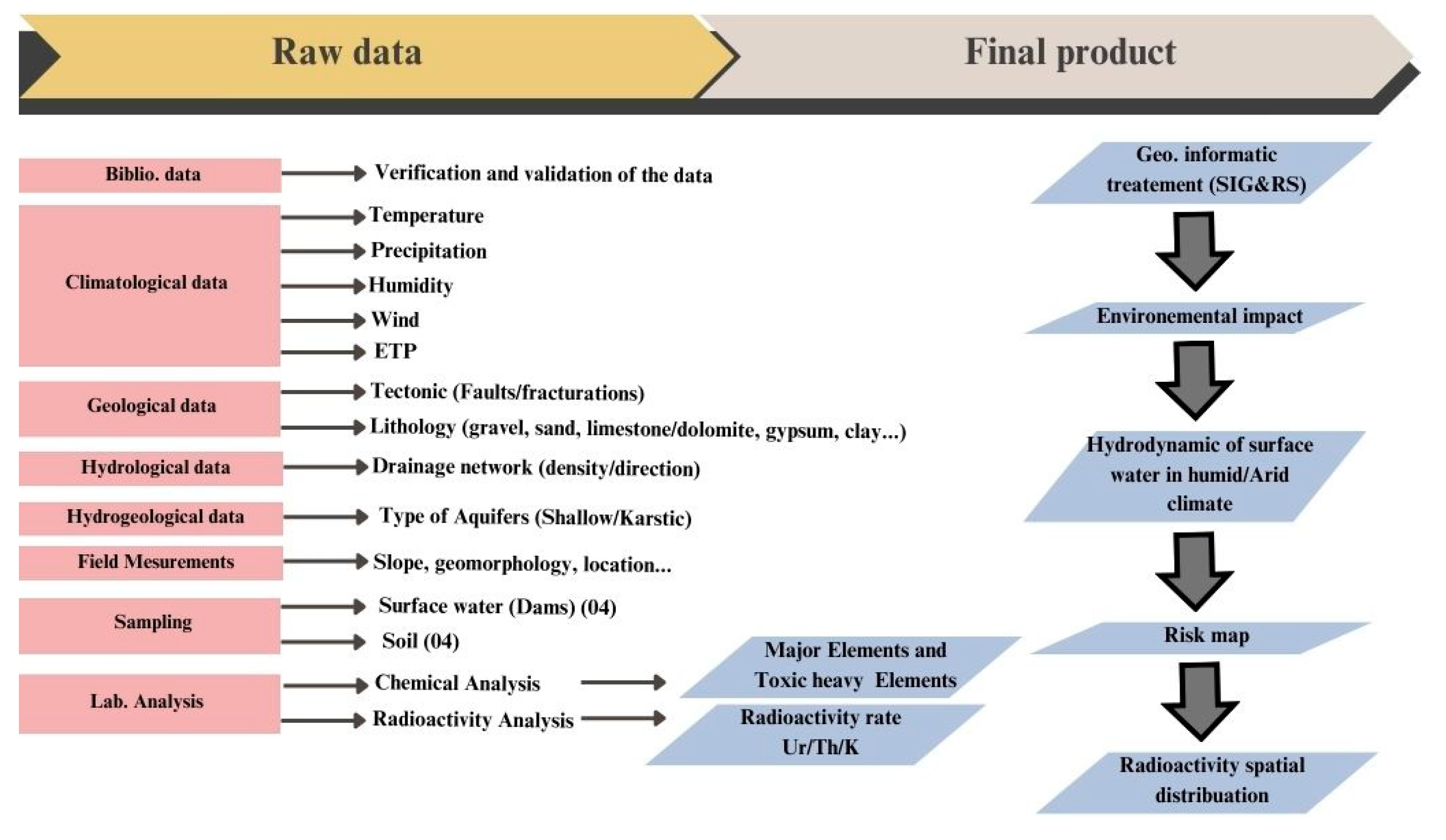

3.1. Work methodology

3.2. Sample collection and preparation

3.3. Gamma Counting

3.4. Radiological parameters impact

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Spatial distribution of the radioactivity in the Dams

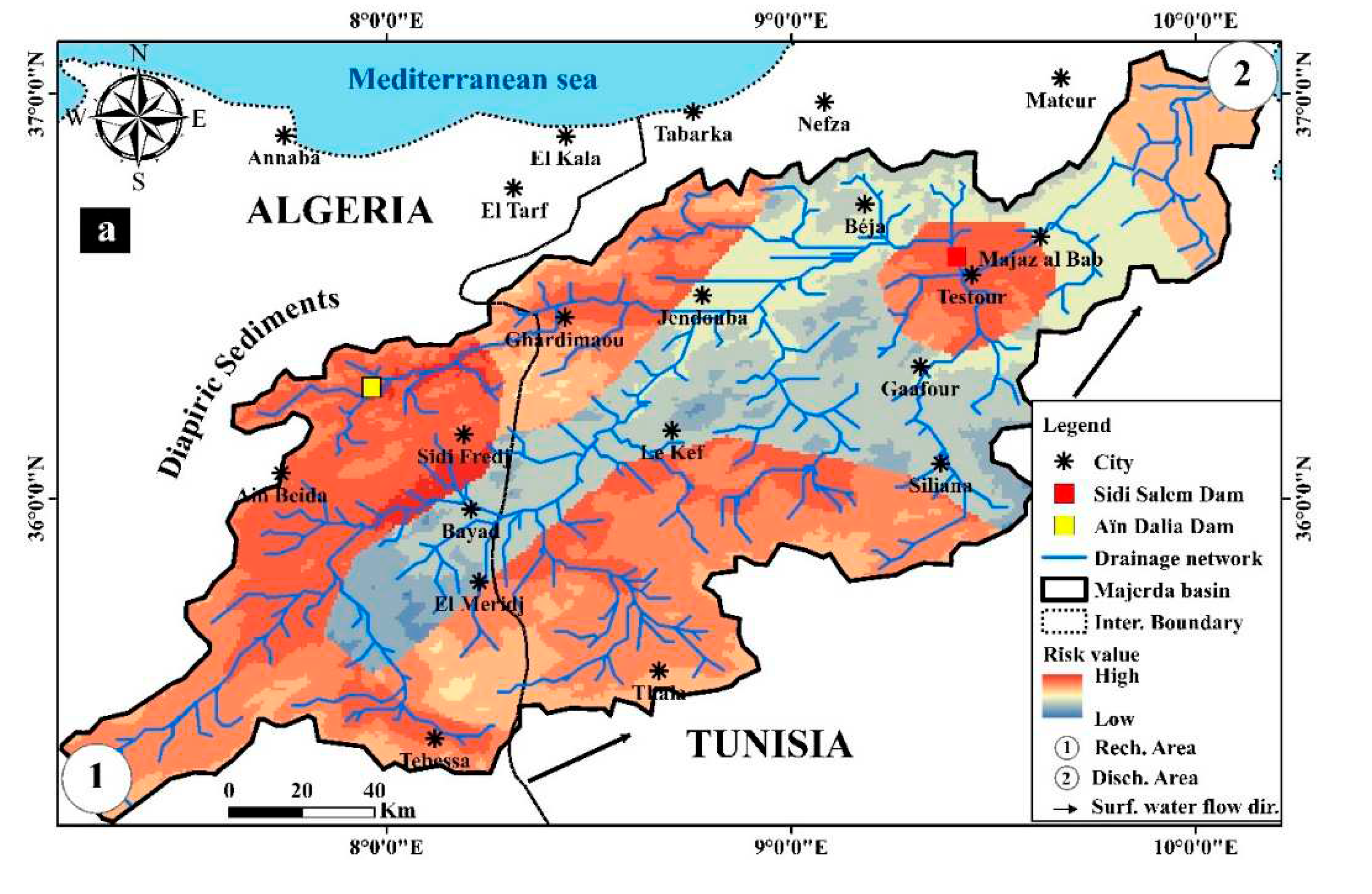

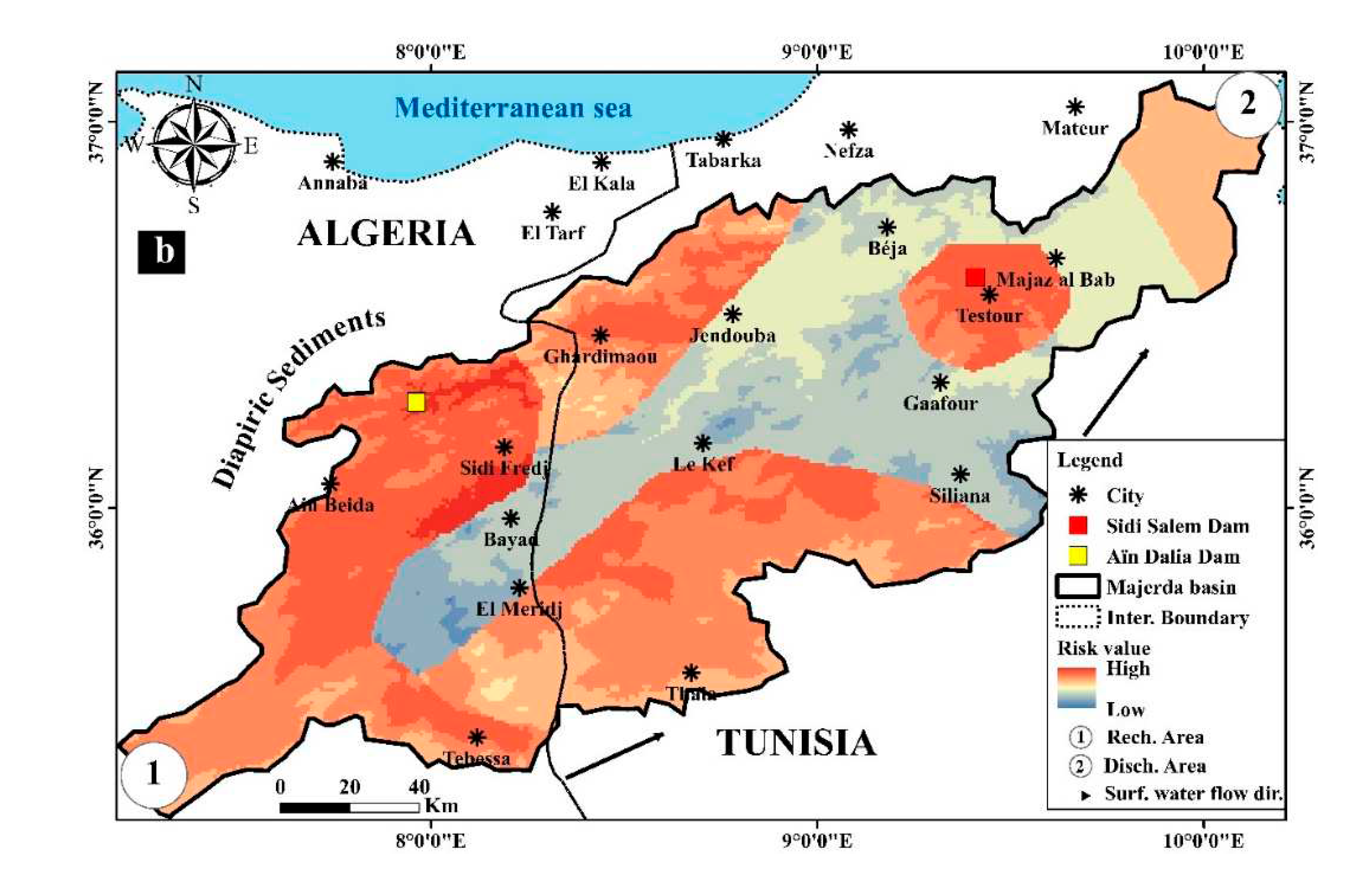

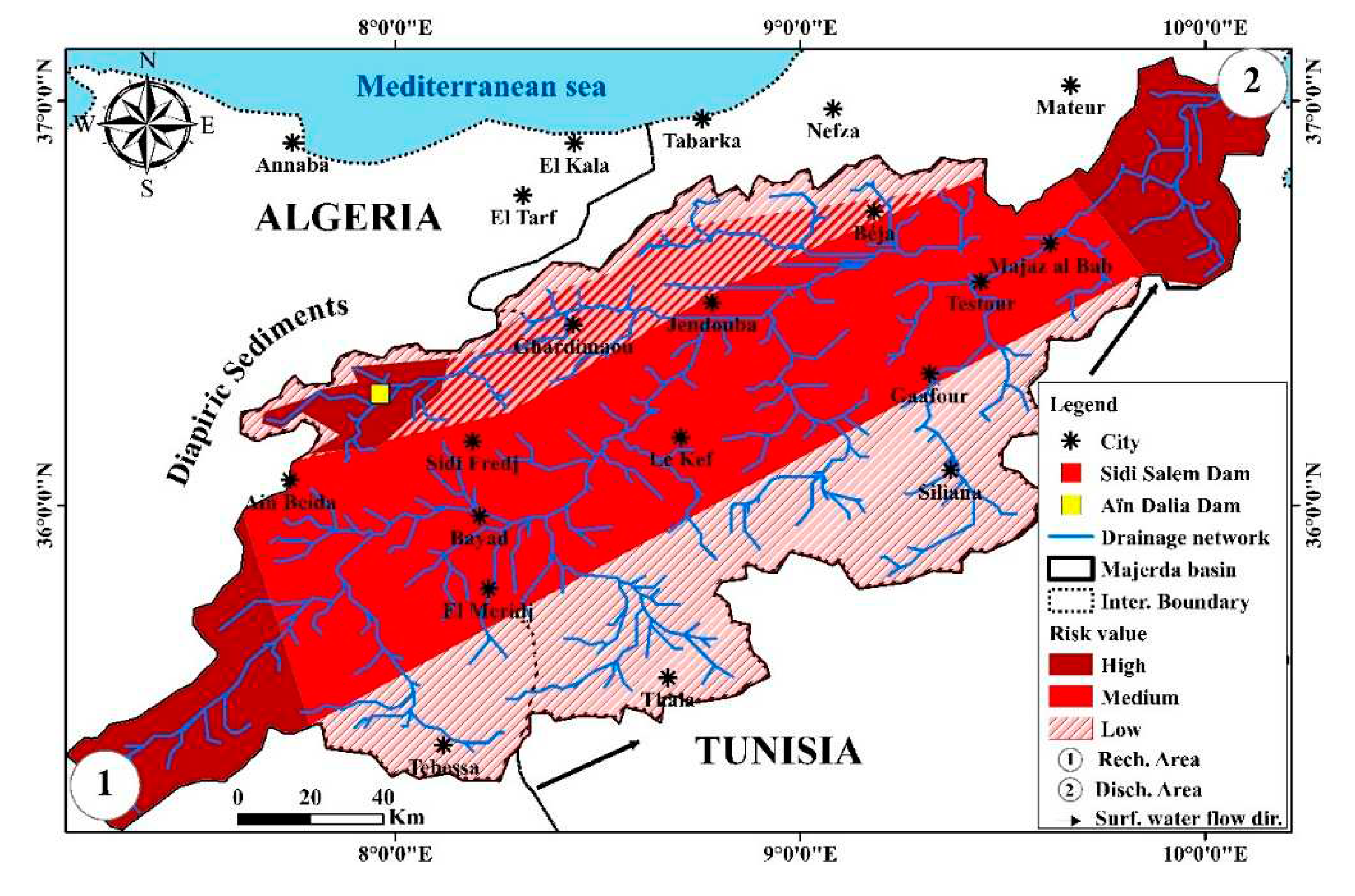

4.2. Risk map of the radioactivity distribution in the study area

4.3. Spatial distribution of the toxic heavy metals in the study area

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Measurement of radionuclides in food and environments. A guide book, IAEA Technical Report, 1989, Series No. 295, Vienna.

- Hamed, Y. Hydrogeological, Hydrochemical and Isotopic characterization of deep groundwater in Kef Basin (NW Tunisia) Master report, Faculty of Sciences of Sfax, 2004, p 180.

- Ayadi, Y.; Redhaounia, B.; Mokadem, N.; Zighmi, K.; Dhaoui, M.; Hamed, Y. Hydro-geophysical and geochemical studies of the aquifer systems in El Kef region (Northwestern Tunisia). Carbonates Evaporites 2019, 34, 1391–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, Y.; Hadji, R.; Ncibi, K.; Hamad, A.; Ben Sâad, A.; Melki, A.; Khelifi, F.; Mokadem, N.; Mustafa, E. Modelling of potential groundwater artificial recharge in the transboundary Algero-Tunisian Basin (Tebessa-Gafsa): The application of stable isotopes and hydroinformatics tools *. Irrig. Drain. 2021, 71, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.; Hadji, R.; Bâali, F.; Houda, B.; Redhaounia, B.; Zighmi, K.; Legrioui, R.; Brahmi, S.; Hamed, Y. Conceptual model for karstic aquifers by combined analysis of GIS, chemical, thermal, and isotopic tools in Tuniso-Algerian transboundary basin. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, Y.; Khelifi, F.; Houda, B.; Ben Sâad, A.; Ncibi, K.; Hadji, R.; Melki, A.; Hamad, A. Phosphate mining pollution in southern Tunisia: environmental, epidemiological, and socioeconomic investigation. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, Y.; Mokadem, N.; Besser, H.; Redhaounia, B.; Khelifi, F.; Harabi, S.; Nasri, T.; Hamed, Y. Statistical and geochemical assessment of groundwater quality in Teboursouk area (Northwestern Tunisian Atlas). Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSCEAR, United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation, 2000, Volume I: Annex A. Dose Assessment Methodologies. United Nations, New York.

- ICRP, International Commission on Radiological Protection. Protection of the Public in Situations of Prolonged Radiation Exposure, ICRP Publication82. Ann. ICRP. 29:1 – 2, 2000. 1: 29, 2000; 2.

- ICRP, International Commission on Radiological Protection, Age-dependent Doses to Members of the Public From Intake Of Radionuclides: Part 5, Compilation of Ingestion and Inhalation Dose Coefficients. ICRP Publication 72, Pergamon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, 1996.

- WHO, World Health Organization, Guidelines For Drinking-Water Quality (4th Ed.), WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data NLM classification, Geneva, 2011 WA 675. 2011.

- USEPA, US Environmental Protection Agency, Risk Assessment Guidance For superfund. Volume I, Human Health Evaluation Manual : Part E, Supplemental Guidance for Dermal Risk Assessment), Report EPA/540/R/99/005, US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. 2014.

- El Arabi, A.M.; Ahmed, N.K.; Din, K.S. Natural radionuclides and dose estimation in natural water resources from Elba protective area, Egypt. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2006, 121, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulemia, S.; Hadji, R.; Hamimed, M. Depositional environment of phosphorites in a semiarid climate region, case of El Kouif area (Algerian–Tunisian border). Carbonates Evaporites 2021, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahleb, A.; Hadji, R.; Zahri, F.; Boudjellal, R.; Chibani, A.; Hamed, Y. Water-Borne Erosion Estimation Using the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) Model Over a Semiarid Watershed: Case Study of Meskiana Catchment, Algerian-Tunisian Border. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2022, 40, 4217–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncibi, K.; Mastrocicco, M.; Colombani, N.; Busico, G.; Hadji, R.; Hamed, Y.; Shuhab, K. Differentiating Nitrate Origins and Fate in a Semi-Arid Basin (Tunisia) via Geostatistical Analyses and Groundwater Modelling. Water 2022, 14, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, S.; Baali, F.; Hadji, R.; Brahmi, S.; Hamad, A.; Rahal, O.; Zerrouki, H.; Saadali, B.; Hamed, Y. Assessment of groundwater and soil pollution by leachate using electrical resistivity and induced polarization imaging survey, case of Tebessa municipal landfill, NE Algeria. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncibi, K., Hadji, R., Hajji, S., Besser, H., Hajlaoui, H., Hamad, A., Mokadem, N.; Ben Saad, A.; Hamdi, M.; Hamed, Y. Spatial variation of groundwater vulnerability to nitrate pollution under excessive fertilization using index overlay method in central Tunisia (Sidi Bouzid basin). Irrigation and Drainage 2021, 70, 1209–1226. [CrossRef]

- Fredj, M.; Hafsaoui, A.; Riheb, H.; Boukarm, R.; Saadoun, A. Back-analysis study on slope instability in an open pit mine (Algeria). Nauk. Visnyk Natsionalnoho Hirnychoho Universytetu 2020, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmarce, K.; Hadji, R.; Zahri, F.; Khanchoul, K.; Chouabi, A.; Zighmi, K.; Hamed, Y. Hydrochemical and geothermometry characterization for a geothermal system in semiarid dry climate: The case study of Hamma spring (Northeast Algeria). J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2021, 182, 104285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerzour, O.; Gadri, L.; Hadji, R.; Mebrouk, F.; Hamed, Y. Geostatistics-Based Method for Irregular Mineral Resource Estimation, in Ouenza Iron Mine, Northeastern Algeria. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2021, 39, 3337–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, I.; Khedidja, A.; Chattaha, W.; Hadji, R. Multivariate statistical-based approach to the physical-chemical behavior of shallow groundwater in a semiarid dry climate: The case study of the Gadaïne-Ain Yaghout plain NE Algeria. Min. Miner. Deposits 2022, 16, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpolile, F.A.; Ugbede, F.O. Natural radioactivity study and radiological risk assessment in surface water and sediments from Tuomo river in Burutu, delta state Nigeria. J. Nig. Ass. Math. Phys. (J. NAMP). 2019; 50, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Khandaker, M.U.; Uwatse, O.B.; Khairi, K.A.B.S.; I Faruque, M.R.; A Bradley, D. TERRESTRIAL RADIONUCLIDES IN SURFACE (DAM) WATER AND CONCOMITANT DOSE IN METROPOLITAN KUALA LUMPUR. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2019, 185, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zahrani, K. H.; Baig, M. B. Water in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: sustainable management options. J Anim Plant Sci, 2011; 21, 601–604. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewska-Wasiolek, M. Estimates of the Occupational Radiological Hazard in the Phosphate Fertilizers Industry in Poland. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 1995, 58, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, H.; Philipp, G.; Pauly, H. Population dose from natural radionuclides in phosphate fertilizers. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 1976, 13, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, V.P.; Jain, R.K. Strategies for advancing cancer nanomedicine. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimond, R.J.; Hardin, J.M. Radioactivity released from phosphate-containing fertilizers and from gypsum. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrumentation. Part C. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1989, 34, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shaaibi, M.; Ali, J.; Duraman, N.; Tsikouras, B.; Masri, Z. Assessment of radioactivity concentration in intertidal sediments from coastal provinces in Oman and estimation of hazard and radiation indices. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, H.; Al-Azmi, D. Radioactivity concentrations in sediments and their correlation to the coastal structure in Kuwait. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2002, 56, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi-Golestan, F.; Hezarkhani, A.; Zare, M. Assessment of 226Ra, 238U, 232Th, 137Cs and 40K activities from the northern coastline of Oman Sea (water and sediments). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 118, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özmen, S.; Cesur, A.; Boztosun, I.; Yavuz, M. Distribution of natural and anthropogenic radionuclides in beach sand samples from Mediterranean Coast of Turkey. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2014, 103, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, D.J.; McEldowney, S.; Waite S, S. Pollution, ecology and biotreatment, Longman Sci. Tech. 1994.

- Milivojević, J.; Krstić, D.; Šmit, B.; Djekić, V. Assessment of Heavy Metal Contamination and Calculation of Its Pollution Index for Uglješnica River, Serbia. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 97, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbee, J.Y.; Prince, T.S. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in a Welder Exposed to Metal Fumes. South. Med J. 1999, 92, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandra, D.; Urszula, B. The impact of Nickel on human health, J. Elementol. 2008; 13, 685–696. [Google Scholar]

- Adimalla, N.; Wu, J. Groundwater quality and associated health risks in a semi-arid region of south India: Implication to sustainable groundwater management. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assessment: Int. J. 2019, 25, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, Y.; Dassi, L.; Ahmadi, R.; BEN Dhia, H. Geochemical and isotopic study of the multilayer aquifer system in the Moulares-Redayef basin, southern Tunisia. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2008, 53, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumm, W.; Morgan, J.J. Aquatic Chemistry: An Introduction Emphasizing Chemical Equilibria in Natural Waters. 1981, 2nd edn., J. Wiley & Sons, New York, 780 pp.

| Location/country | D (nGyh-1) |

Raeq (Bqkg-1) |

Hext | Hint | AGED(μSvy-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aïn Dalia dam/Algeria | 14.12 | 36.79 | - | - | 104.53 |

| Sidi Salem dam/Tunisia | 9.59 | 18.16 | - | - | 71.13 |

| World standard value [8] | 57.00 | 370.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 Svy-1 |

| Age Group | 0-1 | 1-2 | 2-7 | 7-12 | 12-17 | 17-25 | 25-45 | 45-65 | >65 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper side (mSvy-1) | 1.22 | 1.59 | 1.83 | 2.14 | 3.66 | 4.45 | 5.12 | 6.34 | 7.04 |

| Lower side (mSvy-1) | 0.84 | 1.09 | 1.26 | 1.47 | 2.52 | 3.06 | 3.76 | 4.12 | 5.02 |

| Word Standard value [8] | 0.12 mSvy-1 | ||||||||

| Region/Country | 238U, Bq kg-1 | 232Th, Bq kg-1 | 226Ra, Bq kg-1 | 40K, Bq kg-1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sidi Salem Dam (Water)/Tunisia | 1.72 | 0.068 | - | 94.6 | Present study |

| Sidi Salem Dam (Sediment) /Tunisia | 2.67 | 0.18 | - | 197.87 | Present study |

| Aïn Dalia Dam (Water) /Algeria | 1.9 | 0.09 | - | 131.43 | Present study |

| Aïn Dalia Dam (Sediment) /Algeria | 4.34 | 0.27 | - | 286.61 | Present study |

| Gafsa Phos.Rock/Tunisia | 702 | 75 | 911 | 90 | [6] |

| Tunisia | - | 29 | 821 | 32 | [26] |

| Egypt | 686 | 5.7 | 656 | 68.6 | [13] |

| Morocco | - | 20 | 1600 | 10 | [27] |

| Algeria | - | 64 | 619 | 22 | [28] |

| Saudi Arabia | - | 17-39 | 64-513 | 242-2453 | [24] |

| Germany | - | 15 | 520 | 720 | [27] |

| USA | - | 49 | 780 | 200 | [29] |

| India | - | 65 | 120 | 2624 | [28] |

| Jordan | - | 2 | 1044 | 8 | [26] |

| Kuala Lampur-Malaysia | - | 1.2 | - | 35.1 | [24] |

| Buruta-Nigeria | - | 26.9 | - | 61 | [23] |

| Oman | - | 2.26 | 20.49 | 44.83 | [30] |

| Kuwait | - | 6 | 36 | 227 | [31] |

| Iran | - | 17.61 | 14.96 | 361.6 | [32] |

| Turkey | - | 9.0 | 12.2 | 157.7 | [33] |

| 238U | 232Th | 40K | Fe | Pb | Zn | Ni | Cu | Cr | Cd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dalw2 | 1.90 ± 0.24 | 0.09±0.01 | 131.43±1.03 | 5.430 | 0.0980 | 0.087 | 0.024 | 0.063 | 0.015 | 0.025 |

| Dals3 | 4.34±0.05 | 0.27±0.05 | 287.61±3.34 | 201.9 | 5.88 | 5.046 | 0.216 | 0.441 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| Dtnw4 | 1.72±0.01 | 0.068±0.01 | 94.6±1.04 | 9.700 | 0.065 | 0.061 | 0.018 | 0.043 | BDL1 | 0.130 |

| Dtns5 | 2.67±0.01 | 0.18±0.012 | 197.87±2.01 | 136.7 | 3.41 | 3.22 | 0.182 | 0.213 | BDL1 | 0.15 |

| WHO limits | 1.0 | 0.1 | 10.0 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 2.00 | 0.05 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).