1. Introduction

The pollution of the environment caused by the accumulation of plastic waste has become one of the most pressing environmental problems requiring attention. This is mainly attributable to the increase in disposable plastic products that take a long time to degrade, where the food packaging industry is a major contributor to this waste. In order to address the accumulation of plastic residues, the use of non-renewable resources and the reduction of pollutants reaching the sea, European and Global strategies and regulations have been established that include a number of targets related to the use and management of plastic resources to be met in the coming years [

1,

2,

3]. For example, the European Plastics Strategy dictates that by 2030 all packaging should be reusable, recyclable or compostable. Thus, nowadays, the search and interest by the food-packaging sector for new compostable polymers produced from renewable resources and, principally, from the revaluation of agro-industrial residues, has grown considerably. In this regard, protein-based biopolymers have become a research topic thanks to their biodegradability, low cost, large availability and good barrier to gases [

4]. Although the use of protein-based films has been extensively researched, they commonly present low stability at humid conditions and low flexibility and elongation at break values. These characteristics are of great importance in the performance as food packaging, and therefore, the search for strategies for improving their overall technological properties has driven to their chemical modification through the addition of crosslinkers, plasticizers or other plastic additives, and/or the blending of polymers [

5,

6,

7].

Gliadins, wheat protein by-product of the starch industry, consist of a heterogeneous group of single polypeptide chains associated via hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions [

8,

9]. Gliadins are interesting biopolymers characterized by good viscoelasticity, thermo-plasticity and film-forming properties [

9,

10], but some of their properties, such as poor mechanical properties and weak water stability, need to be improved in order to extend their use for food packaging applications.

Keratin is a fibrous structural protein that is a key component of the outer layer of human skin, hair, nails, feathers, horns, and the epidermal tissues of animals. Keratin has been widely used in biomedical applications, such as drug delivery vehicle, bone tissue engineering and wound healing, the production of biodieselbiogas, animal feed, and bioplastics [

7,

11,

12]. Keratin-derived materials have shown excellent properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability and mechanical durability among others [

13,

14]. The cost of keratin extraction can vary widely depending on several factors, including the source of keratin, the extraction method used, the scale of production, and the quality of the final product, nevertheless it is usually tedious and expensive process [

15,

16]. In addition, the attempt of finding more renewable sources of these biopolymers as their recovery from agro-industrial residues has recently emerged of great need. In this sense, chicken feathers are valuable residues from poultry processing industry that are commonly discarded. Feathers contain approximately 91% keratin, 1% fat and 8% water [

6,

17,

18], and therefore, they can be a great source of keratin proteins and biopolymer production. Some works have already used practically raw feathers directly in the fabrication of novel materials, minimizing the treatment of waste from chicken production and promoting the circular economy. Besides, the use of solvents, water, electricity, and in consequence carbon footprint, could be reduced. A previous work has blended chicken feathers with polylactic acid (PLA) biopolymer at 5 and 50% respect total material weight [

7], and the effect of the addition of feathers on the biodegradation of resulting composites was studied. Shanmugasundaram et al (2018) have demonstrated the potential application of fabricated chicken feather keratin/polysaccharides blends for nonwoven wound dressings biomaterials [

6].

In this work, feathers and gliadin blends have been developed and characterized in order to analyze their suitability as sustainable food packaging materials. The novelty of this present work lies both in the higher incorporation of this residue into a final composite and in the study of the physical and morphological properties of the resulting blends. The compatibility and the performance of blends for packaging purposes were studied through the analysis of their optical, morphological, thermal, mechanical and barrier properties.

2. Results

2.1. Morphological and Structural Properties

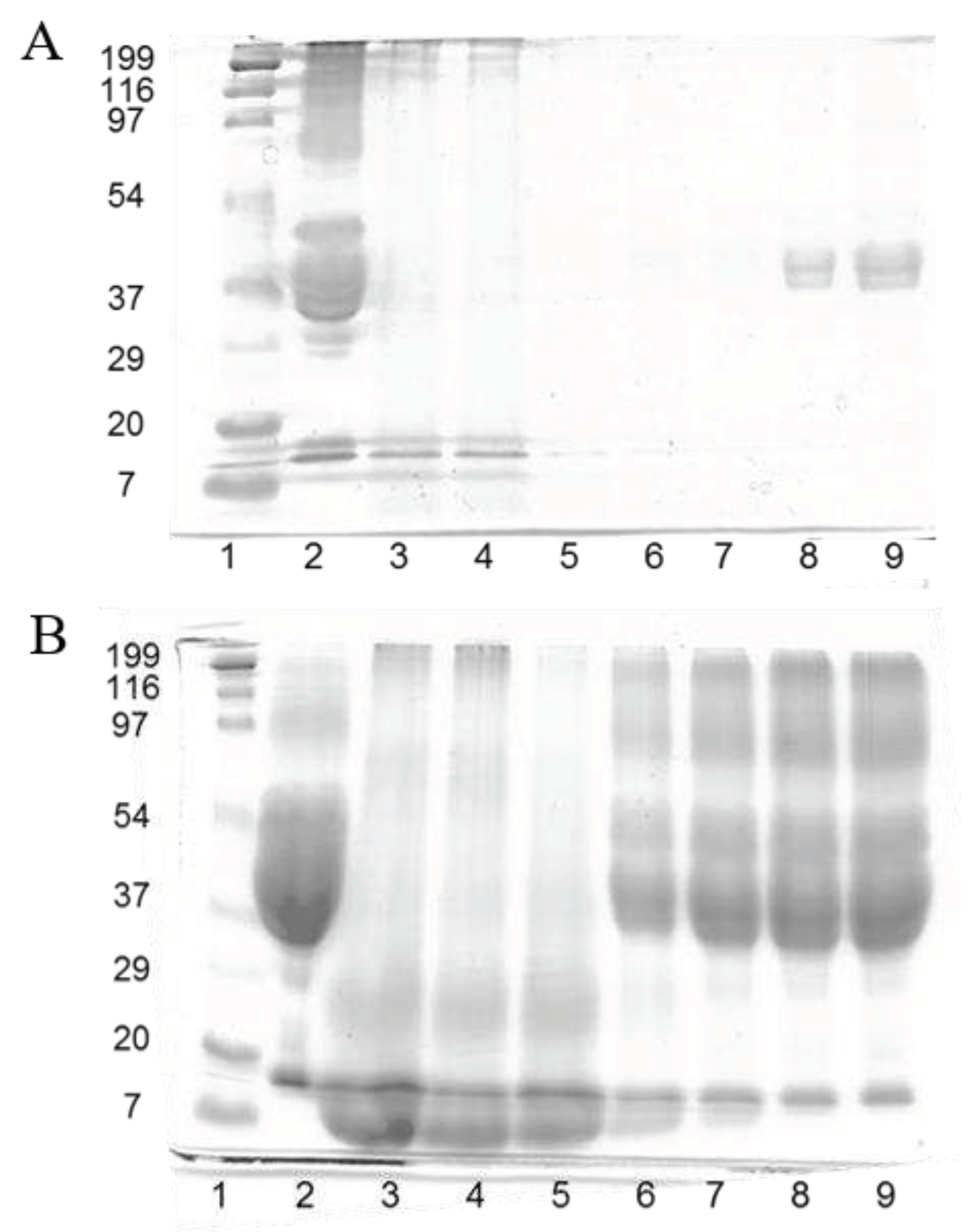

Figure 1 shows the SDS-PAGE patterns of gliadin resin, plain and reduced feathers, and the corresponding thermo-pressed developed films. The pattern of the gliadin resin that was not subjected to reducing conditions with 2-ME (

Figure 1A, lane 2) displayed a typical poorly defined protein bands corresponding to gliadins in the 37-50 kDa range [

9]. On the other hand, it was observed a considerable amount of high-molecular weight protein as a diffuse band in the 95-200 kDa range, contrary to the results shown by native gliadins. Due to the fact that this diffuse protein band of high molecular weight mostly disappeared under reducing conditions (

Figure 1B, lane 2), it is likely to be composed of gliadin units cross-linked via SH-SS interchange reactions formed during the drying of the gliadin solution to obtain the resin.

Feather keratins are composed of approx. 20 proteins that differ by only a few amino acids and they have similar molecular weight of 10.4 kDa [

19,

20]. Plain feathers (

Figure 1A, lane 3) scarcely manifested protein bands, owing to the high degree of cross-linking and insolubility of native feather keratin fibers [

20]. In fact, a considerable amount of undissolved feathers was clearly visible in the denaturation buffer. Similar results were obtained with feathers that were subjected to the reducing treatment with Na2SO3 (

Figure 1A, lane 4). F100 film (

Figure 1A, lane 5) did not exhibit any protein band, being indicative of the reorganization of the reduced protein fragments observed in lane 4 during film thermo-pressing to form a polymeric matrix that was insoluble under non-reducing denaturation conditions. The same events occurred to G25F75 (

Figure 1A, lane 6) and G50F50 (lane 7) films. G75F25 and G100 protein films (

Figure 1A, lanes 8 and 9, respectively) presented a short amount of protein in the lanes, indicating the high insolubility of the films under not reducing conditions, and their protein bands were in the region of gliadins.

When analyzing the SDS-PAGE patterns under reducing conditions (

Figure 1B), a high amount of protein in the 10 kDa region in lanes 3 and 4 was observed, indicating that feather fibers were reduced to render keratin. F100 film (lane 5) displayed a similar pattern than plain and reduced feathers, indicating that the film protein network was mainly stabilized by disulphide bonds. G100 film (lane 9) exhibited a diffuse protein band of high density in the 35-200 kDa range, derived from the reduction of S-S bonds that stabilized the structure of gliadin film. Blended films showed characteristics of the films elaborated with the single components, including protein fragments of high (35-200 kDa) and low (10 kDa) molecular weights, in relative proportions correlated to the amount of each polymer in the blend. These results indicated the high implication of disulphide bonds in the stabilization of the structure of the matrix of keratin and gliadin films and their blends and are in agreement with previous works [

21,

22].

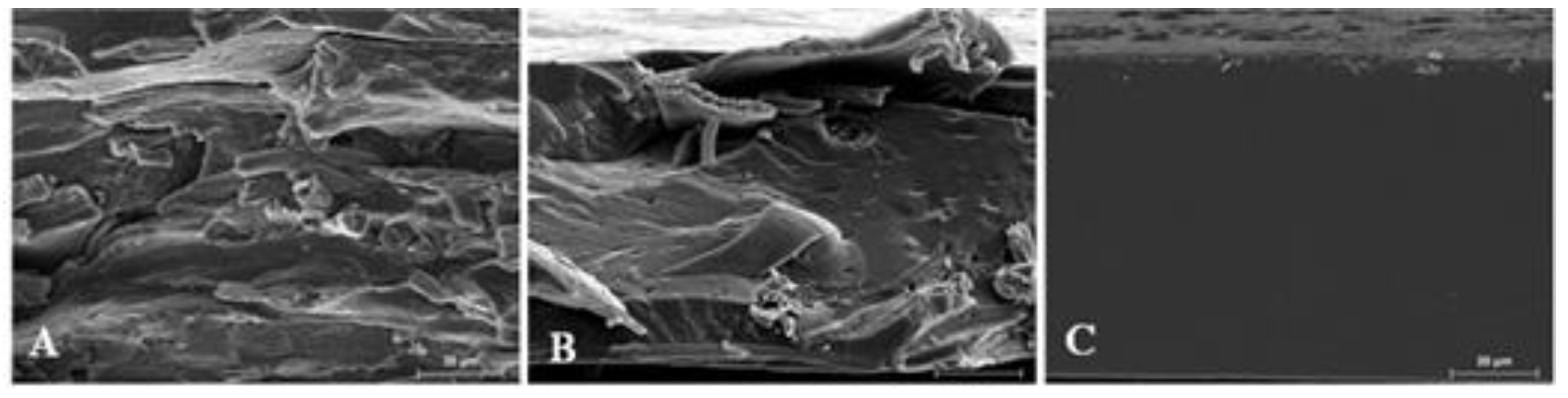

Figure 2 shows the SEM images of cross-sectional films. Because gliadin films presented a smooth and homogeneous structure, the effect of the incorporation of feathers in to the polymeric matrix films was clear. As

Figure 2C shows, the gliadin film exhibited a continuous structure associated to an adequate polymeric melting process and formation of the polymeric network during the film formation through the thermo-compressed process. On the contrary, the film containing pure feathers (

Figure 2B) evidenced a heterogeneous surface with fibrous structures, indicative of an imperfect reduction of the keratin filaments. In turn, the SEM micrograph of the film resulting from the equal mixture of gliadin and feathers presented characteristics of both polymers with both continuous and fibrous zones, indicating a heterogeneous mixture of both polymers.

2.2. Optical Properties

The color parameters of blended films and their controls were analyzed and the results are given in

Table 1. The first evidence was that the films thickness greatly increased with the feather content in the blends, presenting the F100 film more than doubling in thickness compared to the gliadin G100 film. All films were processed at the same temperature and pressure, so it is possible that the keratin in the feathers exerted greater resistance to film compression-formation. Regarding the optical parameters, all film samples were homogeneous and transparent, as the luminosity values (L*) indicated. All developed films displayed high values of L* close to 90, although the incorporation of feather (and the subsequent thickness increase) slightly reduced this value, that is, increasing slightly the opacity. All films exhibited a visually similar yellow-greenish color that increased with the feathers ratio, confirmed by increases of negative a* (green) and positive b* (yellow) values. The intensity of color depended on feathers presence, as can be seen in

Table 1, the chroma value is higher in F100 than G100 and increased in blends as the feathers concentration increased.

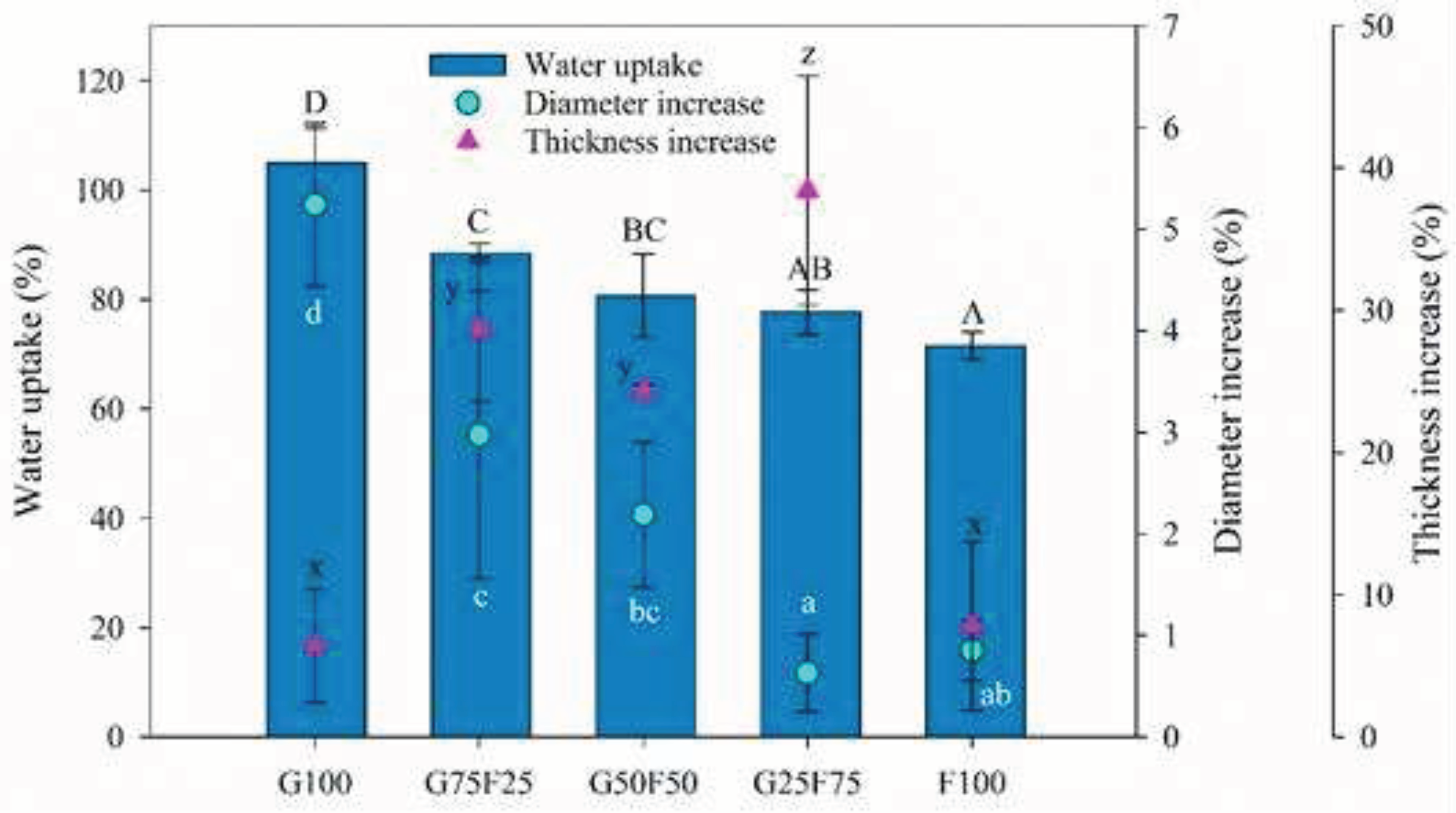

2.3. Swelling, Weight Loss and Dimensional Stability Results of Developed Films

The swelling property defines an insight about the behaviour of films in aqueous medium. In this section, the swelling degree was characterized by the water uptake and the increase of thickness and diameter. As

Figure 3 shows, the swelling degree of gliadin G100 film was greater than for feather-containing films, resulting on both the highest water uptake and the greatest diameter increase, even though the thickness was slightly increased. G100 film approximately doubled its weight with the water uptake after 24 h. On the other hand, feather F100 film presented the lowest water uptake and diameter and thickness increases. Analogously, the blends resulted on structures with high swelling degree accompanied by high dimensional increases including both thickness and diameter. Blending the two matrixes resulted on water uptake and diameter increase data intermediate to those of both pure polymers, reducing the swelling as the proportion of feathers in the mixture increased. The thickness increase was very low for the individual polymers but high for the blends probably due to the heterogeneous structure shown in

Figure 2B.

The water resistance in a buffer medium at pH 7 of developed films was analyzed through the weight loss (WL) parameter whose results are shown in

Table 1. All samples maintained their integrity and a slight enhancement of water-resistance was observed for blended films probably to some crosslinking formation between some chemical groups of gliadin and feather, as it was previously evidenced by SDS-PHAGE patterns of blends. As Balaguer et al. (2011) observed, the weight loss of gliadin and feather films was principally attributed to the release of glycerol, an hydrophilic plasticizer added on both polymers, into the aqueous medium and some loss of polypetide chains from gliadins and polar components from feathers [

23].

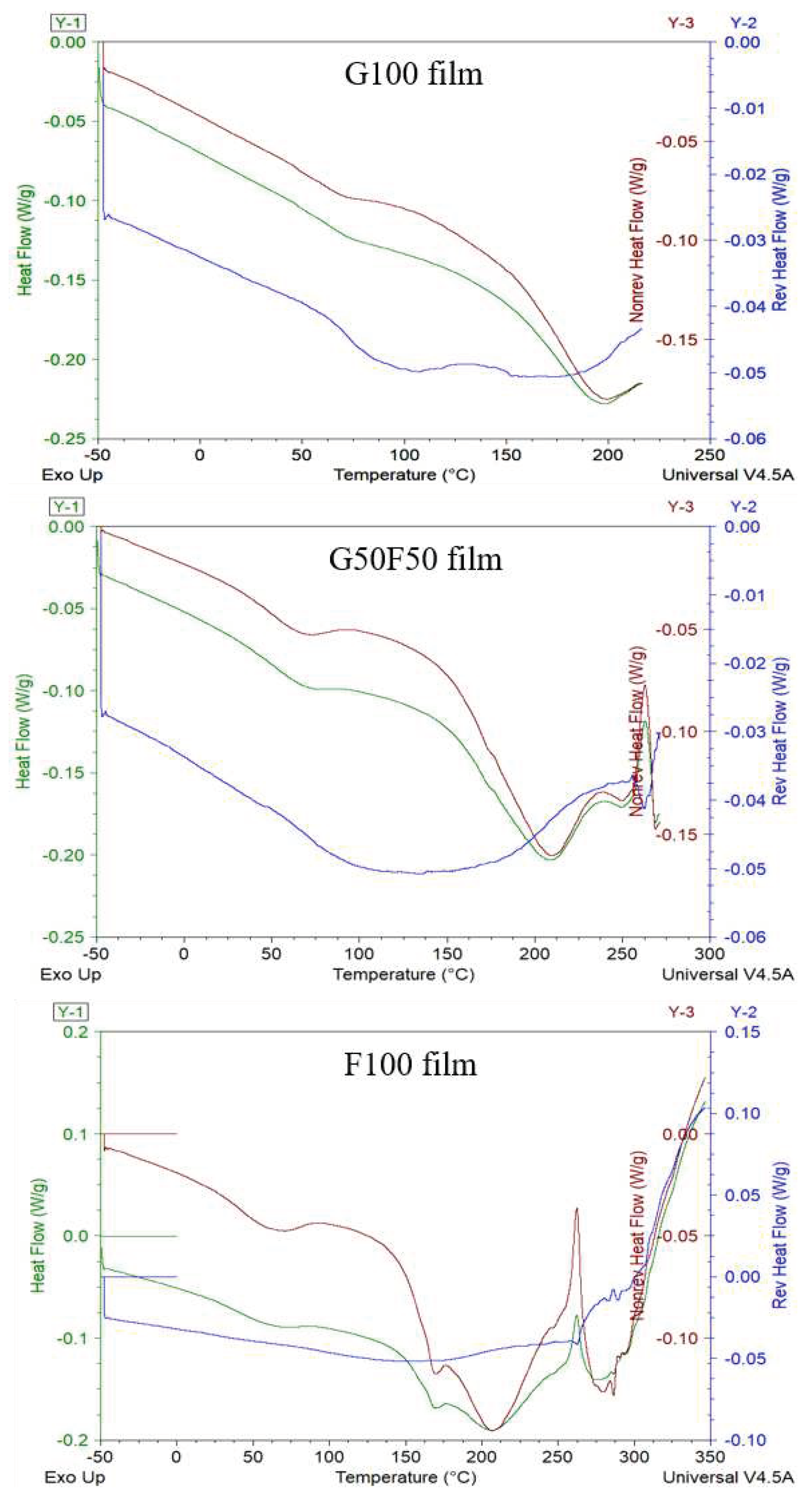

2.4. Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (MDSC) Results

Modulated DSC (MDSC) studies have been carried out in order to facilitate the analysis of the glass transition temperature, T

g, of the films, since near this temperature range there are often interferences with some endothermic processes derived from intrinsic moisture evaporation and endothermic relaxation peak of internal molecular stresses occurred during processing. MDSC describes neither reversibility and non-reversible transitions that are correlated to the thermodynamic and kinetic contributions, respectively, in a single scan [

23,

24]. The MDSC conditions used in these thermograms are commonly applied for the study of glass transition temperatures with enthalpy relaxations [

25]. As

Figure 4 shows, the separation of the glass transition and the enthalpy relaxation was clearly, and the T

g of G100 and G50F50 were visible as a step change on the reversing heat capacity signal while the enthalpy relaxation appeared on the non-reversing heat-flow curve.

Some authors have claimed the molecular dynamics of vegetable proteins as gliadins differ significantly from that of animal proteins, as keratin [

26]. As

Figure 4 shows, gliadin is an amorphous biopolymer that presented a clear glass transition temperature (T

g) at ca. 73.7

°C that evinced the undergo from a glassy to a rubbery state, while feather containing keratin did not manifested this thermal transition. This result can be due to the fact that in this work feathers are not a pure extracted polymer and probably the other feather components can hide this transition. Moreover, Ferrari and Johari (1997) have argued that the animal proteins may exceptionally broad glass-softening endotherm only after they are hydrated, and, in contrast to gliadins, this endotherm was not affected by the amount of water. On the other hand, hydration of vegetable proteins, as the addition of plasticizers, shifts the glass transition temperature towards lower temperatures [

27].

In

Figure 4, the total heat flow of each sample in green is the sum of reversing and non-reversing heat flows. The non-reversible processes (in red lines) displayed molecular relaxation and evaporation processes of both gliadin and feathers. Conversely, the reversing events (in blue lines) involved the glass transition temperatures. The analysis of T

g of blends has indicated all samples presented similar values, approx. between 73.6 and 75.6

°C. MDSC did not provide relevant information, but evidenced the lack of crystallinity of both polymers, and the lack of effect of feather incorporation on T

g values of gliadins in the blended films. On the other hand, feather containing films presented a small endothermic transition in the non-reversible transition associated probably to the intrinsic water evaporation. Subsequently, a broad endothermal first-order transition due to helix denaturation protein was revealed between 150 and 250 °C with a maximum at 208 °C approx.[

28,

29].

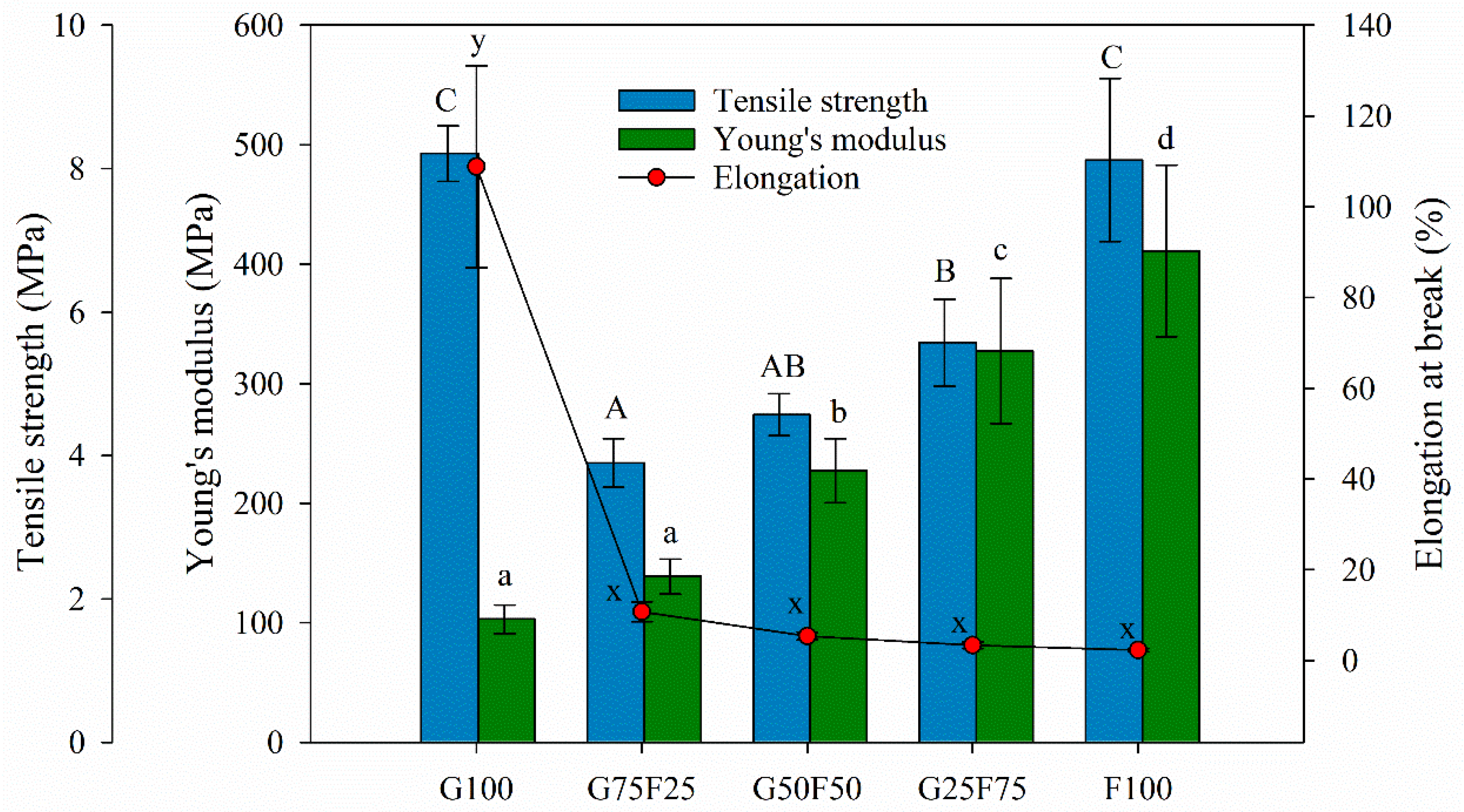

2.5. Mechanical Properties of Developed Films

The tensile parameters of gliadin and feathered films and their blends are detailed in

Figure 5. F100 film presented the highest YM value, in agreement with other works [

30]. Minimizing the extraction process of keratin from feathers, the protein maintained the disulfide and hydrogen bonds. Young´s modulus of blended films were between values of the gliadin (G100) and feather (F100) control films. As the concentration of feathers increased, the Young´s modulus and tensile strength increased. Keratins are the chemical base of animal´s tissues, having mainly structural and mechanical functions. They present good mechanical resistance thanks to the great amount of disulfide bonds that are formed by covalent links among polypeptide chains present in the protein [

17]. In general, feather films presented higher stiffness than gliadins, similar maximum tensile strength at break and lower deformation due to their keratin composition.

The incorporation of feather in the blends implied a great decrease on the elongation at break values. Possibly, the heterogeneous morphology of the blended matrices generated shear points that resulted in materials with low fracture toughness. Generally, the mechanical properties of polymer blends are known to be influenced by the interaction or compatibility between the component polymers [

31]. Usually, compatible polymer blends lead to a significant improvement in mechanical properties, while incompatible polymer blends often lead to inferior mechanical properties [

32]. The low elongation at break value of F100 film suggested that the addition of 20 %wt. glycerol was not sufficient to overcome the brittleness of this material. Gliadin and keratin films obtained by the casting technique have shown higher elongation at break values [

30]. During processing by thermo-pressing, due to the high temperature, a loss of plasticizer could probably have occurred. Elongation at break values could be raised by increasing plasticizer concentration due to their ability to reduce hydrogen bonds between polymeric chains and decrease protein chain-to-chain interactions.

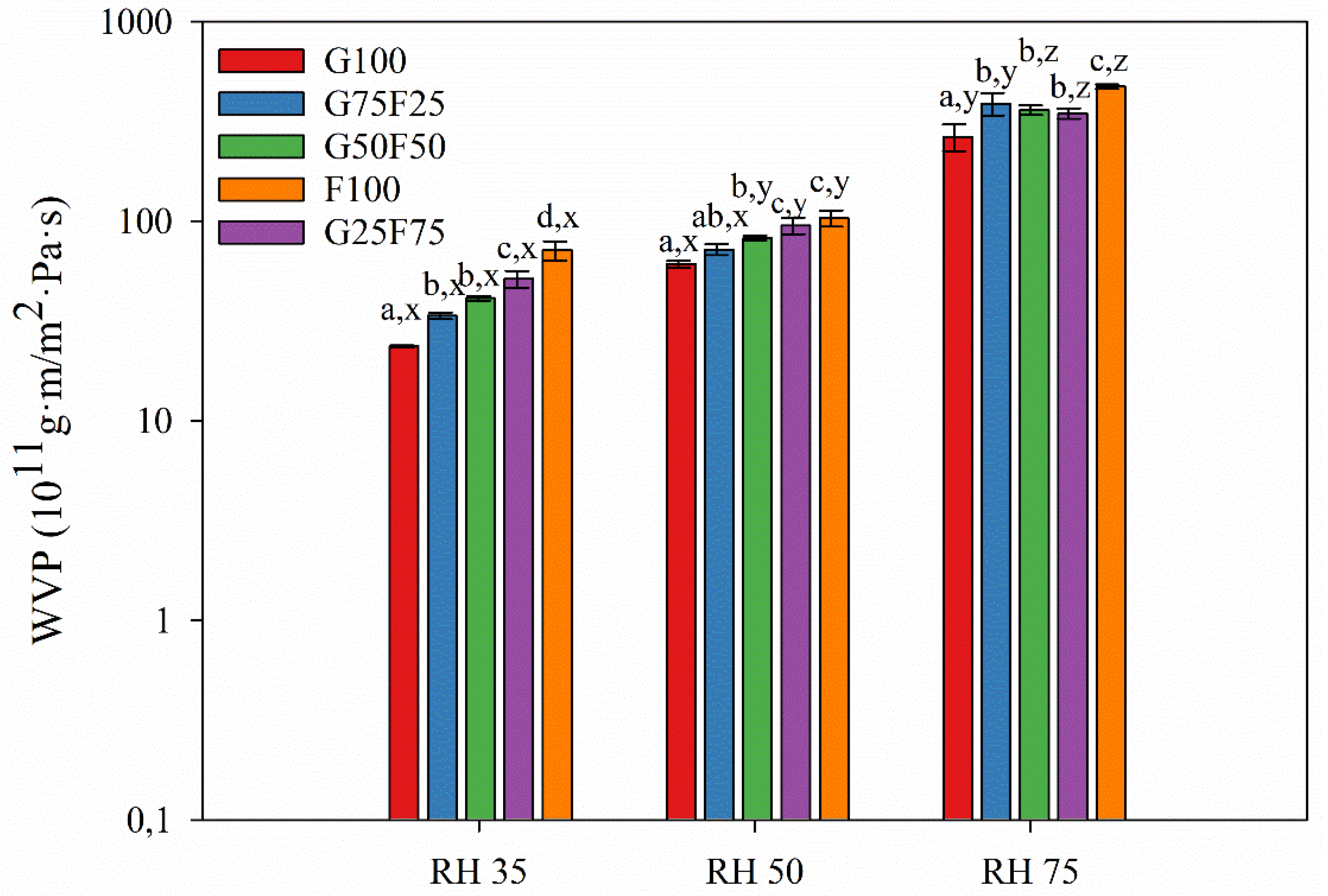

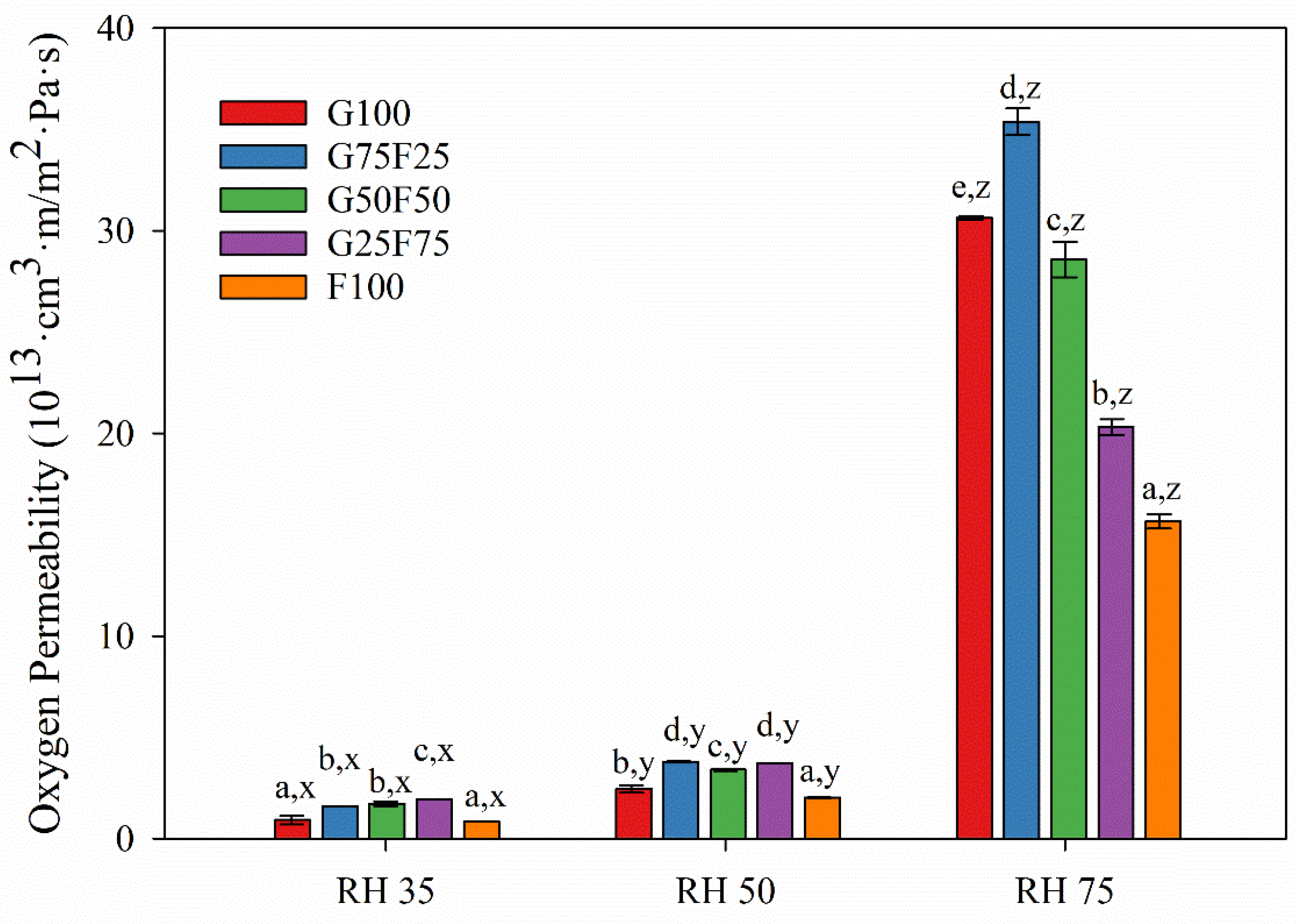

2.6. Barrier Properties of Developed Films

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 exhibit the water and oxygen barrier properties of developed films, respectively. Both graphs indicated that the values of water vapor and oxygen permeabilities were dependent on the ratio of gliadin and feather and on the humidity (RH) to which the film was exposed. Both permeabilities were clearly affected by increasing RH due to the hydrophilic character of both polymers. The chemical structure of both proteins together with the addition of glycerol as a plasticizer resulted in a highly moisture sensitive polymeric matrix due to the interaction between hydrogen bonds with water molecules, reducing the interchain bonding and increasing the movement of polymeric chains, and therefore, the permeability to gases and vapor [

33]. However, it should be noted that the gliadins exhibited slightly lower water vapor permeability values than the feathers, and their resulting blends displayed intermediate permeability results.

As

Figure 6 shows, at RH 35 and 50, the water vapor permeabilities of blended films were between values of the gliadin (G100) and feather (F100) control films. Increasing feather concentration deteriorated the water vapor barrier of gliadin films. The hydrophilic nature of proteinaceous films and the substantial amount of hydrophilic plasticizer added to impart adequate flexibility were responsible for their poor water vapor resistance [

34]. Glycerol is particularly more hydrophilic than other plasticizers as sorbitol whose addition to keratin films have shown lower WVP values [

30].

The oxygen permeability values decreased greatly with the incorporation of 75% feather at high RH. Gliadins present an excellent oxygen barrier in dry conditions, but as

Figure 7 shows, this property was greatly deteriorated with relative humidity. Specifically, for gliadin polymeric matrix, the entry of water molecules and their interaction with the amide groups of the polymer progressively reduce the cohesive energy of the polymer through interchain hydrogen bonds, resulting in plasticization of the matrix and increasing the diffusion coefficient [

34].

3. Discussion

The present study aimed to analyze the viability of developing food packaging materials based on gliadin and feather fibers. Morphological analysis revealed the miscibility of both polymeric matrices was not completely homogenous and therefore, several physical properties were dependent on the gliadin and feather content. Gliadins evidenced higher hydrophilicity and therefore higher water uptake and diameter increase values in aqueous medium. In general, all blended films presented low elongation at break values and their stiffness increased with feather content.

At low and medium relative humidities (RH), gliadin G100 film presented the lowest water vapor permeability and, as the concentration of feather increased, WVP increased. At high RH, WVP of films did not present significant differences. In contrast, oxygen permeability (OP) of films at low and medium RHs were similar, while at high RH, OP values diminished greatly as feather concentration increased.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Crude wheat gluten (>80% protein), glycerol, ethanol, tris-hydrochloride (Tris-HCl), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), bromophenol blue, 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) and sodium sulfite were supplied by Sigma (Madrid, Spain). Chicken feathers were purchased from Featherfiber Corporation® (Missouri, United States).

4.2. Gliadin and Feather Keratin Resin Preparation

Gliadin-rich fraction was extracted from wheat gluten according to the method described by Hernández-Muñoz et al. (2003) [

35]. Initially, 100 g of wheat gluten were dispersed in 400 mL of 70% (v/v) ethanol/water mixture, stirred overnight at room temperature, and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 min at 20 °C. The supernatant containing the gliadin-rich fraction was collected and the precipitate, consisting mostly of glutenins and residual starch was discarded. Protein content in the supernatant was determined gravimetrically after solvent evaporation. Glycerol was added to the gliadin-rich fraction at a ratio of 25 g/100 g of protein and stirred until complete mixing. The mixture was left to evaporate under continuous stirring at 100 °C for 15 h and then placed in a thermostatic chamber at 37 °C for one week until the complete evaporation of the solvent was achieved. The resin obtained was frozen with liquid nitrogen and grounded in a Moulinex grinder to obtain a fine powder.

Crude feathers (10 g) were mixed with 6 mL of 5% (w/v) sodium sulfite aqueous solution (final concentration of 3 g Na2SO3/100 g feather) and 10 mL of distilled water, and the blend was manually stirred in a mortar for 10 min. Then, 2.5 g of glycerol (final concentration of 20 g glycerol/100 g feather) were added and conveniently blended. The blend obtained was dried under vacuum at 70 °C for 24 h, stored at 0% RH for 5 days, and then grounded in a Moulinex grinder to obtain a fine powder. The powders were kept under dry conditions until their use.

4.3. Film Formation

The powder of plasticized resins from gliadin and feathers were blended at 4:0, 3:1, 2:2, 1:3 and 0:4 (w/w) ratio in a mortar through manual mixing during 7 min. The powder mixture was conditioned at 50% RH, and then, approximately 0.9 g of each blend were thermally compressed by using a hydraulic press (Carver, Inc., Wabash, IN, USA) at 130 °C. Pressure was applied first at 4 t for 1 min, subsequently 14 t for 2 min, and finally 22 t for 9 min. The resulting films were coded as G100 (100% gliadin), G75F25 (75% gliadin, 25% feather keratin), G50F50 (50% gliadin, 50% feather keratin), G25F75 (25% gliadin, 75% feather keratin) and F100 (100% feather keratin). The resulting films were conditioned and stored at 50 % RH until their characterization.

4.4. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

The molecular weight distribution of proteins present in films was analyzed by SDS-PAGE performed in a vertical electrophoresis unit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and following the procedure of Laemmli with some modifications [

36]. Samples were denatured by mixing 50 µg of ground film with 1 mL of loading buffer (2.5% SDS, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 6% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, with or without 5% 2-ME) with or without reduction of disulfide bonds with 5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol and heating at 95 ºC for 5 min. Each sample-buffer mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 2 h with occasional shaking and centrifuged at 13000 g for 10 min. 10 µL of the clear top layer of each sample were loaded into each slot in the gel. The stacking gel was 4% acrylamide and the resolving was 12% acrylamide. The electrophoresis was carried out at 25 mA/gel for 1.5 h. The gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The molecular weights of the standard protein mixture (Bio-Rad) ranged from 199 kDa (myosin), 116 (β-galactosidase), 97 (bovine serum albumin), 53 (ovalbumin), 37 (carbonic anhydrase), 29 (soybean trypsin inhibitor), 20 (lysozyme) to 7 kDa (aprotinin).

4.5. Characterization of Developed Films

The thickness of the films was measured using a micrometer (Mitutoyo, Japan) with a sensitivity of ± 1 µm. The mean thickness was calculated from measurements taken at ten different locations on each film sample.

4.5.1. Optical Properties

Film color was measured using a Konica Minolta CM-35000d spectrophotometer set to D65 illuminant/10° observer. Film specimens were measured against on the surface of a standard white plate and the CIELAB color space was used to obtain the color coordinates L* [black (0) to white (100)], a* [green (-) to red (+)] and b* [blue (-) to yellow (+)]. The color coordinate C* is the chroma and it was calculated following equation 1:

Eight measurements were taken of each sample and three samples of each film were measured.

4.5.2. Morphological Analysis

The films were fractured under liquid nitrogen and their cross-section surface morphology was studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Hitachi model S-4100 with a BSE Autrata detector and an EMIP 3.0 image capture system (Hitachi, Madrid, Spain). The samples were coated with gold-palladium under vacuum in a sputter coating unit

4.5.3. Swelling Property, Weight Loss and Dimensional Stability

Film specimens measuring 25 mm in diameter were dried for 10 days in a desiccator at 0% relative humidity (RH). Samples were accurately weighed (initial dry weight,

) and immersed in test tubes containing 20 mL of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7. The tubes were agitated at 180 rpm and 25 °C for 24 h. Films were removed from the solutions; remaining water was eliminated from the surface with absorbent paper before weighing (final wet weight,

). Films were placed in the desiccator until they reached a constant weight (final dry weight,

). The percentage of weight loss of the films and water uptake were calculated following equations 2 and 3:

As a measure of the dimensional stability of the films after immersion, both the diameter and the thickness were measured and results have been expressed as diameter and thickness increase, ∆∅ and ∆l, respectively, through equations 4 and 5:

where is the initial diameter, the final diameter, the initial thickness and the final thickness.

4.5.4. Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (MDSC)

Measurements of the glass transition temperature (Tg) of films conditioned at 0% RH at 23 °C were determined by modulated differential scanning calorimetry using a TA Instruments DSC Q2000 (TA Instruments Inc., New Castle, DE, USA) equipped with Universal Analysis 2000 software. Nitrogen was used as a purge gas at a flow rate of 50 mL/min. Temperature calibration of the instrument was performed with indium. The heating rate was 2 °C/min, the modulation period was 60 s and the amplitude of modulation was 0.32 °C. The glass transition temperature was recorded from the inflexion point of the reversing heat flow signal. The films were dried over P2O5 at 23 °C for 2 weeks before testing. Dry samples of approximately 5 mg were placed in aluminum pans with inverted lids to achieve optimum thermal conductivity. These were sealed, punctured three times and kept over P2O5 for a further week prior to scanning. All samples were measured in duplicate.

4.5.5. Mechanical Properties

Mechanical behavior of developed films, such as Young’s modulus (YM), tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break (EB), were determined in a Zwick Roell universal machine (model BDO-FB 0.5 TH, Ulm, Germany) according to the ASTM D882 normative [

37]. Specimens with dimensions 16.5 cm x 2.4 cm were cut and conditioned at 23 °C for 48 h in a desiccator at 50% relative humidity. The separation distance between the jaws was 50 mm and the crosshead speed was 500 mm/min. The results were reported as the mean and standard deviation of 15 measurements.

4.5.6. Water Vapor Permeability

Water vapor transmission rates (g/m

2.s) of developed films were measured using a PERMATRAN-W Model 3/33 (Lippke, Neuwied, Germany). Testing was performed at 23 °C with a RH gradient of 50 to 0% (in dry nitrogen) across the film. At least four samples of each type of film were analyzed. Permeability values were reported as water permeability coefficient in g·m/m

2·s·Pa calculated as following equation 6:

where Q is the amount of permeant passing through a film (g) of thickness l (m) and area A (m

2), t is time (s), and ∆P is the partial pressure differential across the film (Pa). ∆P is calculated from the water vapor partial pressure at the temperature selected and the RH gradients.

4.5.7. Oxygen Permeability

Oxygen transmission rates (cm

3/m

2·s) through films were measured using an OX-TRAN Model 2/21 (Lippke, Neuwied, Germany) according the ASTM Standard Method D 3985-05 [

22]. Testing was performed at 23 ºC and constant relative humidities of 35%, 50%, and 75%. At least four samples of each type of film produced were analyzed. The samples were conditioned in the cells for 24-48 h, then the transmission values were determined every 45 min. Permeability values were reported as oxygen permeability coefficient in cm

3·m/m

2·s·Pa.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the results was performed with SPSS commercial software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL. USA). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out. Differences between means were assessed on the basis of confidence intervals using the Tukey test at a level of significance of p ≤ 0.05. The data were graphically plotted with Sigmaplot software (Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA. USA).

5. Conclusions

Blended films composed by gliadin and feather were successfully developed at different ratios. The findings of the current work show the potential application of developed blends for food packaging systems although further analysis need to be done. Mechanical and barrier properties can be modified by adjusting the concentration of both polymeric matrices. The oxygen permeability results indicated the suitability of fabricated blends for gas barrier that could be part of a multilayer system showing potential application of novelty and ecofriendly packaging. Besides, as a positive relevant point, blending chicken feathers directly with biopolymers can be an alternative for upcycling this by-product waste.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JGE and PHM; methodology, JGE; software, CLdD; formal analysis, JGE, CLdD and GLC; investigation, PHM and RG; resources, PHM and RG; writing-original draft preparation, CLdD; writing-review and editing, GLC, RG, PHM and CLdD; funding acquisition, RG and PHM. All authors have red and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the “Ramon & Cajal” Fellowship RYC2020-029874-I funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”. This work was supported by project PID2019-108361RB-I0 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- European Comission. A European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy; 2018; Volume 24.

- Velásquez, E.; Patiño Vidal, C.; Rojas, A.; Guarda, A.; Galotto, M.J.; López de Dicastillo, C. Natural Antimicrobials and Antioxidants Added to Polylactic Acid Packaging Films. Part I: Polymer Processing Techniques. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3388–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez, E.; Garrido, L.; Valenzuela, X.; Galotto, M.J.; Guarda, A.; López de Dicastillo, C. Physical Properties and Safety of 100% Post-Consumer PET Bottle -Organoclay Nanocomposites towards a Circular Economy. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2020, 17, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Estaca, J.; Gavara, R.; Catalá, R.; Hernández-Muñoz, P. The Potential of Proteins for Producing Food Packaging Materials: A Review. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2016, 29, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Yang, Y. Developing Water Stable Gliadin Films without Using Crosslinking Agents. J. Polym. Environ. 2010, 18, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, O.L.; Syed Zameer Ahmed, K.; Sujatha, K.; Ponnmurugan, P.; Srivastava, A.; Ramesh, R.; Sukumar, R.; Elanithi, K. Fabrication and Characterization of Chicken Feather Keratin/Polysaccharides Blended Polymer Coated Nonwoven Dressing Materials for Wound Healing Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 92, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.K.; Huda, M.S.; Smith, M.C.; Mulbry, W.; Schmidt, W.F.; Reeves, J.B. Biodegradability of Injection Molded Bioplastic Pots Containing Polylactic Acid and Poultry Feather Fiber. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 4930–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornell, H.; Hoveling, A.W. Wheat: Chemistry and Utilization; 1998; ISBN 9781566763486.

- Balaguer, M.P.; Gómez-Estaca, J.; Gavara, R.; Hernandez-Munoz, P. Biochemical Properties of Bioplastics Made from Wheat Gliadins Cross-Linked with Cinnamaldehyde. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 13212–13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voci, S.; Fresta, M.; Cosco, D. Gliadins as Versatile Biomaterials for Drug Delivery Applications. J. Control. Release 2021, 329, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Massé, D.I.; McAllister, T.A.; Beaulieu, C.; Ungerfeld, E. Anaerobic Digestion of Chicken Feather with Swine Manure or Slaughterhouse Sludge for Biogas Production. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Sameera, D.K.; Moorthi, A.; Selvamurugan, N. Chitosan Scaffolds Containing Chicken Feather Keratin Nanoparticles for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 62, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, S.; Kumar, R.; Sripriya, R.; Rao, U.; Mandal, A.; Kakkar, P.; Reddy, P.N.; Sehgal, P.K. Characterization of Keratin–Collagen 3D Scaffold for Biomedical Applications. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2012, 23, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, A.J.; Church, J.S.; Huson, M.G. Environmentally Sustainable Fibers from Regenerated Protein. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilakamarry, C.R.; Mahmood, S.; Saffe, S.N.B.M.; Arifin, M.A. Bin; Gupta, A.; Sikkandar, M.Y.; Begum, S.S.; Narasaiah, B. Extraction and Application of Keratin from Natural Resources: A Review. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, F.S.; Memon, N. Recent Developments in Extraction of Keratin from Industrial Wastes. Extr. Nat. Prod. from Agro-industrial Wastes A Green Sustain. Approach 2023, 281–302. [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.M.; Laurindo, J.B. Chicken Feather Keratin Films Plasticized with Polyethylene Glycol. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2012, 61, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Guzman, R.C.; Saul, J.M.; Ellenburg, M.D.; Merrill, M.R.; Coan, H.B.; Smith, T.L.; Van Dyke, M.E. Bone Regeneration with BMP-2 Delivered from Keratose Scaffolds. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1644–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WOODIN, A.M. Molecular Size, Shape and Aggregation of Soluble Feather Keratin. Biochem. J. 1954, 57, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrooyen, P.M.M.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Oberthür, R.C.; Bantjes, A.; Feijen, J. Partially Carboxymethylated Feather Keratins. 2. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Films. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, J.R.; Dangaran, K.; Schmidt, W.F. Blends of Cysteine-Containing Proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5393–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Song, Y.; Zheng, Q. Morphology and Mechanical Properties of Thermo-Molded Bioplastics Based on Glycerol-Plasticized Wheat Gliadins. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, M.P.; Gómez-Estaca, J.; Gavara, R.; Hernandez-Munoz, P. Functional Properties of Bioplastics Made from Wheat Gliadins Modified with Cinnamaldehyde. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 6689–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.S.; Sauerbrunn, S.R.; Reading, M. Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry. J. Therm. Anal. 1993, 40, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Fernández, C.A.; Gómez-Barreiro, S.; López-Beceiro, J.; Naya, S.; Artiaga, R. New Approach to the Double Melting Peak of Poly(l-Lactic Acid) Observed by DSC. J. Mater. Res. 2012, 27, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.; Johari, G.P. Thermodynamic Behaviour of Gliadins Mixture and the Glass-Softening Transition of Its Dried State. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1997, 21, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro López, M.D.M.; De Dicastillo, C.L.; Vilariño, J.M.L.; Rodríguez, M.V.G. Improving the Capacity of Polypropylene to Be Used in Antioxidant Active Films: Incorporation of Plasticizer and Natural Antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 8462–8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakkar, P.; Madhan, B.; Shanmugam, G. Extraction and Characterization of Keratin from Bovine Hoof: A Potential Material for Biomedical Applications. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2014, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Wu, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, M.; Gao, P. Preparation and Characterization of Sponge Film Made from Feathers. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 4732–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, S.M.; Moore, G.R.P.; Laurindo, J.B. Mechanical Properties, Water Vapor Permeability and Water Affinity of Feather Keratin Films Plasticized with Sorbitol. J. Polym. Environ. 2006, 14, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindle, L.P.; Krochta, J.M. Physical Properties of Whey Protein--Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose Blend Edible Films. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan The, D.; Debeaufort, F.; Voilley, A.; Luu, D. Biopolymer Interactions Affect the Functional Properties of Edible Films Based on Agar, Cassava Starch and Arabinoxylan Blends. J. Food Eng. 2009, 90, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de Dicastillo, C.; Alonso, J.; Catalá, R.; Gavara, R.; Hernández-Munoz, P. Improving the Antioxidant Protection of Packaged Food by Incorporating Natural Flavonoids into Ethylene-Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer (EVOH) Films. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, M.P.; Cerisuelo, J.P.; Gavara, R.; Hernandez-Muñoz, P. Mass Transport Properties of Gliadin Films: Effect of Cross-Linking Degree, Relative Humidity, and Temperature. J. Memb. Sci. 2013, 428, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Muñoz, P.; Kanavouras, A.; Ng, P.K.W.; Gavara, R. Development and Characterization of Biodegradable Films Made from Wheat Gluten Protein Fractions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7647–7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D882 - 10 Standard Test Method For Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting | PDF | Young’s Modulus | Yield (Engineering). Available online: https://es.scribd.com/document/430888339/ASTM-D882-10-Standard-Test-Method-for-Tensile-Properties-of-Thin-Plastic-Sheeting (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- D3985 Standard Test Method for Oxygen Gas Transmission Rate Through Plastic Film and Sheeting Using a Coulometric Sensor. Available online: https://www.astm.org/d3985-17.html (accessed on 13 August 2023).

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE patterns in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of 2-mercaptoethanol. Samples are: 1) molecular weight marker; 2) gliadin resin; 3) plain feathers; 4) reduced feathers; 5) F100 film; 6) G25F75 film; 7) G50F50 film; 8) G75F25 film; and 9) G100 film.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE patterns in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of 2-mercaptoethanol. Samples are: 1) molecular weight marker; 2) gliadin resin; 3) plain feathers; 4) reduced feathers; 5) F100 film; 6) G25F75 film; 7) G50F50 film; 8) G75F25 film; and 9) G100 film.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of cross section of: A) Feathers; B) F50G50 film; and C) gliadin film.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of cross section of: A) Feathers; B) F50G50 film; and C) gliadin film.

Figure 3.

Water uptake (%), diameter increase (%) and thickness increase (%) of blended gliadin-feather films when exposed to water at 25 ºC for 24 h. “A, B, C..” indicate significant differences of water uptake results among the films; “a, b, c..” indicate significant differences among the values of diameter increase between films; and “x, y and z” indicate significant differences among the values of thickness increase between films.

Figure 3.

Water uptake (%), diameter increase (%) and thickness increase (%) of blended gliadin-feather films when exposed to water at 25 ºC for 24 h. “A, B, C..” indicate significant differences of water uptake results among the films; “a, b, c..” indicate significant differences among the values of diameter increase between films; and “x, y and z” indicate significant differences among the values of thickness increase between films.

Figure 4.

MDSC thermograms including total thermogram in green, reversible in blue lines and non-reversible transitions in red lines of G100; G50F50; and F100 films.

Figure 4.

MDSC thermograms including total thermogram in green, reversible in blue lines and non-reversible transitions in red lines of G100; G50F50; and F100 films.

Figure 5.

Tensile parameters of gliadin (G), feather (F) film and their blends. “A, B, C..” indicate significant differences among the values of tensile strength between films; “a, b, c..” indicate significant differences among the values of Young´s modulus between films; and “x and y” indicate significant differences among the values of elongation at break between films.

Figure 5.

Tensile parameters of gliadin (G), feather (F) film and their blends. “A, B, C..” indicate significant differences among the values of tensile strength between films; “a, b, c..” indicate significant differences among the values of Young´s modulus between films; and “x and y” indicate significant differences among the values of elongation at break between films.

Figure 6.

Water vapor permeability values of G and F blends at different relative humidity (RH) gradients and 23 ºC. “a, b, c..” indicate significant differences among the values of the films at the same RH; and “x, y and z” indicate significant differences among the values of WVP at different RHs of a sample.

Figure 6.

Water vapor permeability values of G and F blends at different relative humidity (RH) gradients and 23 ºC. “a, b, c..” indicate significant differences among the values of the films at the same RH; and “x, y and z” indicate significant differences among the values of WVP at different RHs of a sample.

Figure 7.

Oxygen permeability (OP) values of G and F blends at different relative humidity (RH) gradients and 23 ºC. “a, b, c..” indicate significant differences among the OP values of the films at the same RH; and “x, y and z” indicate significant differences among the values of OP of a film at different RHs.

Figure 7.

Oxygen permeability (OP) values of G and F blends at different relative humidity (RH) gradients and 23 ºC. “a, b, c..” indicate significant differences among the OP values of the films at the same RH; and “x, y and z” indicate significant differences among the values of OP of a film at different RHs.

Table 1.

Thicknesses, color parameters and weight losses (WL) of Gliadins and Feather blend materials.

Table 1.

Thicknesses, color parameters and weight losses (WL) of Gliadins and Feather blend materials.

| Sample |

Thick (µm) |

L* |

a* |

b* |

C* |

WL (%) |

| G100 |

76.8 ± 6.3a

|

89.9 ± 0.3c

|

-2.29 ± 0.05d

|

9.60 ± 0.64a

|

9.9 ± 0.6a

|

26.1 ± 0.6c

|

| G75F25 |

86.3 ± 7.3a

|

89.7 ± 0.3cd

|

-2.28 ± 0.03d

|

10.35 ± 0.78ab

|

10.6 ± 0.8ab

|

26.5 ± 0.1c

|

| G50F50 |

92.5 ± 11.3a

|

89.2 ± 0.3c

|

-2.46 ± 0.06c

|

11.35 ± 0.94b

|

11.6 ± 0.9b

|

25.9 ± 1.3bc

|

| G25F75 |

123.1 ± 9.1b

|

87.6 ± 0.3b

|

-2.71 ± 0.05b

|

13.94 ± 1.10c

|

14.2 ± 1.1c

|

23.7 ± 1.4a

|

| F100 |

180.4 ± 12.5c

|

86.4 ± 0.4a

|

-2.95 ± 0.03a

|

15.75 ± 0.83d

|

16.0 ± 0.8d

|

24.1 ± 1.0ab

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).