1. Introduction

In Korea today, the smart mobility traffic

information system combines and analyzes personal movement information such as

taxis or private cars using big data. It also refers to a new transportation

information provision service that leads potential private users to complex

public transportation by extracting demand patterns of transportation users and

providing integrated mobility services for reservation, information, use, and

payment according to individual user needs. It is a technology that allows

users to set routes for transportation modes from their desired departure point

to destination, according to the demands of public transportation users [

1]. By operating transportation modes at desired

time slots and implementing interconnections between different modes, it

enhances the convenience of transportation for individuals with mobility

challenges. It transitions from a conventional independent transportation

service system that focuses on individual modes to a user-centric integrated

and customized transportation service system that combines and operates various

modes such as public transportation, personal vehicles, and shared cars [

2]. This system aims to provide seamless

transportation information connectivity, improve efficiency in short, medium,

and long-distance travel, and implement an environmentally friendly and sharing

economy-based transportation service in response to climate change. Due to

these reasons, the need for an intelligent transportation system in Korea can

be summarized as follows. Firstly, although the public transportation mode

share in Korea has shown excellent performance compared to advanced countries,

it has been stagnant at around 40% since 2014 [

3],

reaching its limit in terms of increasing the mode share. To respond

efficiently to the constantly changing transportation demand that varies by

local government and small-scale areas, an efficient operational method is

needed along with the supply of new concept transportation modes. Secondly,

while Korea has improved the public transportation service centered around

public transportation providers, various countries have recently introduced new

public transportation services, and the concepts of car sharing and ride

sharing have been spreading in the private vehicle sector [

4]. Thirdly, in the field of public transportation,

overseas cases of Mobility as a Service (MaaS) are emerging, especially in the

Nordic region of Western Europe. MaaS provides demand-based subscriber

transportation packages, offering integrated transportation information

including various modes of transportation on a single platform, as well as

integrated payment services [

5]. It represents

a departure from the existing transportation systems provided by

supply-oriented providers and aims to provide personalized optimal

transportation information and route systems, reservation and payment systems,

and other integrated operational services from the user's perspective. The

rapid urbanization has led to increased congestion in urban areas. To alleviate

this, there is a need to establish an integrated system that provides personalized

transportation services based on comprehensive analysis using big data. This

includes tailored guidance for public transportation based on individual user

demands, integrated mobility services that provide information, reservations,

usage, and payment, and coordinated operations of various transportation modes

to meet the demand. Additionally, in terms of transportation planning and

operation in smart cities, it is necessary to activate smart mobility by

utilizing user activity-based mobility data and develop and standardize service

technologies for integrated public transportation and shared mobility services.

The related trends of strategic products for smart mobility intelligent

transportation systems are shown in

Table 1.

2. Scope and Classification

2.1. Value Chain

Smart mobility is one of the key components of a

smart city, along with transportation, energy, resources, and infrastructure management.

It plays a crucial role in the city's economic and social systems, with

significant government funding and direct impact on citizens' daily lives.

Smart mobility generates a vast amount of data that influences the city's

resources, logistics, energy, and economic flows. The technologies that

constitute smart mobility are expected to play a significant role in enhancing

the competitiveness of cities and countries. The development and production of

new modes of transportation are expected to create jobs, reduce traffic

accidents through technological advancements, and improve the efficiency of

transportation systems, resulting in economic benefits. For example,

advancements in smart cars are projected to create around 320,000 jobs and

reduce approximately 2,500 serious traffic accidents annually, resulting in an

estimated economic impact of 75.4 billion KRW by 2030. The goal is to enhance

user convenience, such as reducing overall travel time, through the integration

of smart mobility systems. By establishing a bidirectional data collection and

sharing system between vehicles and infrastructure, rapid and proactive

responses to unforeseen situations and preventive measures become possible. As

vehicles themselves become a means of communication, they can contribute to

solving urban and transportation issues through data integration facilitated by

IoT, a key component of smart cities. During the initial stages of introducing

autonomous driving, potential challenges arising from the coexistence of autonomous

and conventional vehicles can be overcome through vehicle-to-everything (V2X)

communication, thereby improving the safety and efficiency of cities and

transportation.

Table 2 represents the

industrial structure of the smart mobility transportation information system

field.

2.2. Classification by Purpose

In the field of smart mobility, various and

creative services are being discovered through citizen-participatory

(bottom-up) service concepts. Representative services include personal

transportation sharing services, public transportation sharing services, and

micro-mobility services.

Table 3 provides

a classification by purpose for strategies to implement smart mobility.

2.3. Classification by Technology

The Smart Mobility Traffic Information System can

be broadly classified into the implementation technologies of an AI-based Smart

Mobility Center. It can be further categorized as follows: The implementation

technologies of the Mobility Center include AI-based urban traffic control

technology, mobile-based MaaS (Mobility as a Service) technology, prediction

technology based on big data and simulation, and navigation service technology

based on connected cars. These technologies work together to control the flow

of transportation throughout the city, providing personalized services and

delivering a higher level of service to citizens. The details are shown in the

table below as

Table 4.

2.4. Case Study

For example, various research studies on traffic

management at intersections are being conducted in Korea. Among them, research

on traffic signal systems is actively underway. The current signal systems are

fixed in nature. In order to increase the throughput of intersections, adaptive

methods have also been studied. Adaptive methods involve adjusting the timing

of traffic signals or changing the sequence of signals based on traffic volume.

The optimization problem of traffic signal control, which involves a large

amount of data in a dynamically changing traffic environment, poses a high

level of complexity when solved using traditional mathematical models or

optimization methods. To solve the traffic signal problem, fuzzy techniques and

Q-learning techniques are widely used. A traffic signal control technique using

fuzzy techniques has been proposed for a single intersection. In this approach,

the order of green signals remains fixed, but the duration of green signals is

dynamically adjusted based on traffic volume. The number of vehicles entering

the intersection is measured to determine the current traffic flow during the

green signal and the traffic flow during the red signal in the next phase.

Based on the identified traffic flow, the decision to extend the duration of

the green signal is made. The reduction of green signal duration is not

considered in this approach. On the other hand, Askerzada et al [

6]. determine the traffic flow pattern based on the

measured number of vehicles and adjust the duration of the green signal

accordingly. Traffic signal control using fuzzy techniques allows for more

flexible control in dynamic traffic environments. However, fuzzy control models

incur significant overhead as the fuzzy control rules change and are generated

with the changing environment. Therefore, research on traffic signal techniques

using reinforcement learning, such as Q-learning, is also being conducted. The

Q-learning (QL) technique learns through reinforcement learning to find the

optimal policy. QL has the advantage of not requiring a pre-defined environment

model, making it suitable for dynamic traffic environments. Research on signal

control at intersections using QL can be divided into single intersection

studies and studies that consider multiple intersections together. Single

intersection studies focus on obtaining learning experiences in a single

environment and determining useful ranges for various parameters. The order of

green signals is fixed, and the duration of green signals is adjusted through

learning. Chin et al [

7]. considered the queue

length as a parameter and aimed to always have the fewest vehicles waiting at

the intersection. The queue length represents the length of vehicles waiting in

the intersection lane. Abdulhai et al [

8,

9,

10].

considered the queue length and the time it takes for vehicles to exit the

intersection. They aimed to minimize traffic delay by reducing the deviation in

queue length. While studies on signal control at single intersections are

important, intersections are connected and influenced by adjacent

intersections. Therefore, studies on signal control considering multiple

intersections are being conducted. Multiple intersection studies involve

considering various variables due to the consideration of multiple

intersections. Khamis et al [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. proposed

a system that minimizes travel time between multiple intersections. The travel

time refers to the time taken from the origin to the destination. The system

also pursues a green wave, which gradually turns on three or more consecutive

traffic signals for a progressing group of vehicles, allowing them to pass

through intersections without stopping. This enables vehicles to maintain speed

and minimize fuel consumption. Chin et al [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

distribute appropriate green signal timings according to the situation by

extending or reducing the duration of green signals at multiple intersections.

This adaptive signal control technique aims to minimize queue length.

Comparative studies on various intersections analyzed and adjusted the duration

of green signals based on a fixed signal order. However, since intersections

are configured consecutively, adjacent intersections affect each other. If the

order of signals can be flexibly changed according to the situation, more

efficient traffic signal control can be achieved.

3. Deep Reinforcement Learning

Traffic signal controllers with fixed timings are

typically defined by different cycle profiles and are observed over time as

they alternate, attempting to handle the various traffic flows that commonly

occur. Some of these methods are defined by mathematical models that use

calculus, linear programming, and other optimization algorithms such as

Webster, GreenWave [

21,

22,

23], and Maxband [

24,

25,

26]. Other methods involve using traffic

simulators to build traffic models. For example, Rouphail et al [

27]. minimized link delays and queue times using a

genetic algorithm (GA) applied with the CORSIM simulator, for a 9-intersection

network. However, the results were limited due to the slow convergence of the

GA algorithm. Traffic controllers have started using models that optimize

various traffic metrics by utilizing sensor data. This enables them to better

adapt to changes in traffic flow as following;

- -

Max-pressure aims to maintain balance in the queue length of adjacent intersections. The pressure of a phase is defined as the difference in queue length between incoming and outgoing lanes. Minimizing the pressure of a phase maximizes the throughput of the system, according to Max-pressure algorithm.

- -

SCATS (Sydney Co-Ordinated Adaptive Traffic System) repetitively selects the next signal plan from a predefined set of plans based on the current traffic conditions and predefined performance measures. The model infers the performance of all plans before each cycle and then chooses the plan with better performance.

- -

RHODES is a hierarchical system that predicts the traffic load on each link and allocates phase time according to the predictions, and Liu, et al. developed a controller that identifies upstream and downstream vehicles, in intervals of 15 minutes, to measure their delay and then choosing a signal timing plan that minimizes it.

- -

Tan, et al. developed a traffic controller that senses the number of incoming vehicles and uses fuzzy logic to determine the green time of a single intersection, and Lee, et al. also used a fuzzy logic controller but in multiple intersections. The controller takes decisions based on vehicle data of adjacent junctions.

While such systems generally outperform

fixed-timing controllers, they have been tested in very simplistic scenarios.

They cannot adapt well to real-world urban traffic with complex dynamics, such

as multi-intersection or heterogeneous traffic flow. Recently, reinforcement

learning has become popular in building traffic signal controllers as agents

can learn traffic control policies by interacting with the environment without

predefined models. The reinforcement learning framework naturally fits the

traffic signal controller problem, with the traffic controller as the agent,

traffic data as the state representation, and phase control as the agent's

actions. Various learning models have been explored to build traffic signal

controllers. However, comparing proposed solutions and results is challenging

due to significant variations in problem definitions across literature. We

offer the adoption of a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) approach to address

the traffic control problem.

3.1. CRL (Classic Reinforcement Learning)

The main distinction in different reinforcement

learning approaches lies in whether there is a need to learn the transition

probability function

P. In model-based methods, the agent learns a

transition model that estimates the probability of transitioning between given

states given possible actions, and then calculates the expected rewards for

each transition. The value function is then estimated using dynamic

programming-based methods, and decisions are made based on this estimation.

Model-based methods require learning

P and the reward function

R,

while model-free methods skip this step and learn by interacting with the

environment and directly observing rewards. They perform value function or

policy updates by interacting with the environment and directly observing

rewards. Learning the transition probability function in the context of traffic

control problems implies modeling an environment that can predict metrics such

as vehicle speed, position, and acceleration. Wiering [

28] used a model-based approach in a multi-agent

model operating in a network of six controlled intersections, where each

controller receives the discretized positions and destinations of each vehicle

on approach lanes, resulting in 278 possible traffic situations. The defined

RL-controller performs better than simpler controllers such as fixed-time and

Longest Queue First (LQF), assuming that each vehicle can communicate with each

infeasible signal controller. Additionally, since all distances have the same

number of lanes, the network is simplified, resulting in unrealistic

homogeneous traffic patterns. Our research also mentions the possibility of

having smarter driving policies to avoid congested intersections when previous

communication is assumed to be possible. Some research have attempted a

model-based approach, but most of the research community adopts a model-free

approach due to the difficulty of fully modeling the unpredictable behavior of

human drivers when considering their natural and unpredictable actions. Most tasks

that use a model-free approach rely on algorithms such as Q-learning and SARSA

to learn optimal traffic control policies. Thorpe et al. [

29] built a model-free system using SARSA and

compared the performance of three state representations: volume, presence, and

absence. By dividing each lane in each section of the network into

equal-distance intervals or unequal-distance intervals, vehicles can be

controlled. The RL model outperformed fixed-time and maximum volume controllers

regardless of the state representation used, and the unequal-distance intervals

state representation outperformed the other two state representations. Previous

reinforcement learning-based controllers were applied to single intersections

because the state space exponentially increases with the number of controlled

intersections. Considering that a single intersection model is overly

simplified and cannot estimate traffic at the city level, other studies aimed

to apply reinforcement learning to multiple traffic intersections by constructing

multi-agent models.

3.2. MRL (Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning)

In a MA(Multi-agent setting), each agent controls

one intersection in a traffic network with multiple intersections. This

approach minimizes the explosion of the state space by allowing each agent to

operate in a small partition of the environment. In a non-cooperative approach,

each agent seeks to maximize specific rewards, such as queue lengths or

cumulative delays, using the state representing their respective intersections.

This is commonly referred to as Independent Learners (IL).

Independent Learners. The initial

systems consisted of independent learners (IL) and a small number of

intersections, where smaller intersections performed better. However, over

time, researchers were able to adapt IL to larger road networks. Camponogara et

al [

30,

31,

32,

33]. developed a multi-agent system

based on Q-learning and modeled it as a distributed stochastic game. They

applied the system to a simple network with two intersections and compared it

to random and Longest Queue First policies. The proposed multi-agent model

showed significant performance improvement compared to the other two policies.

However, the agents did not collaborate, and the proposed scenario was very

simplistic. Aslani et al [

34,

35,

36]. controlled

50 intersections in Tehran using well-known reinforcement learning models,

Actor-Critic, and the classic tile coding for function approximation. Mnih et

al [

37,

38,

39]. introduced Deep Q-Network (DQN) in

the Atari Learning Environment (ALE) domain. This approach uses deep neural

networks to estimate the Q-function and utilizes a replay buffer to store

experiences defined by tuples, which serve as inputs to the neural network. DQN

quickly adapts to outperform a baseline by controlling a single intersection in

the ATSC. Chu et al. verify that DQN-based IL performs under a greedy algorithm

that selects the phase with the highest vehicle count. DQN-IL also fails to

perform even simpler Q-learning counterparts for a network of 4 intersection

roads. These results suggest a trade-off between size and performance.

Collaborative Learners. In an

environment where the actions of one agent can affect other agents at nearby

intersections, having isolated self-interested agents that only seek to

maximize their own gains at their own intersections can improve local

performance for some agents but may lead to a degradation of global

performance, especially when dealing with large-scale networks. Therefore,

efforts are made to maximize global performance through some form of

collaboration or information sharing among agents. A naive approach is simply

adding information about every other intersection to the state space. However,

this leads to an exponential growth as the number of intersections increases

and becomes infeasible for larger networks. Thus, a key challenge in

multi-agent settings is to implement coordination and information sharing among

agents while maintaining a manageable size of the state space. There are two

types of cooperative MARL (Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning) systems related

to this task. Joint Action Learners (JAL) explicitly construct models for

coordinating the actions of agents, and coordination graphs are one form of JAL

that has been applied to reinforcement learning-based adaptive traffic signal

control [

40]. Kuyer et al. designed a

vehicle-based model similar to the model-based approach by Wiering using the

GLD (Green Light District) simulator [

41]. The

system achieved coordination using the coordinate graph algorithm called

Max-Plus [

42]. The proposed model was compared

with the original Wiering model, and the extension created by Steingröver added

congestion bits to the state space [

43,

44,

45].

The designed model outperformed other models in both small-scale (4

intersections) and large-scale (8-15 intersections) networks. Van der Pol

applied a deep learning approach in both single and multi-agent settings. The

learning agents used the DQN (Deep Q-Network) algorithm with binary matrices as

inputs representing whether a vehicle is present at a specific location. For

single intersection networks, the DQN agents showed better stability and

performance compared to the baseline agent using linear approximation.

Collaborative multi-agent systems have been shown to overcome the curse of

dimensionality in dealing with complex traffic networks, outperforming

fixed-timing, single RL agent, and non-collaborative multi-agent RL models.

However, most of the tasks rely on directly adding information about other

agents to the state representation, which typically leads to state space

explosion or utilizes coordination graph approaches such as the Max-plus

algorithm that exploits the spatial locality of agents. The actual

effectiveness of such coordination methods is difficult to ascertain as each

task defines different state-action representations and test scenario sets.

This work is inspired by where a fixed MDP formulation is used to compare

traffic controllers. The methodology inspired by Varela is used for

experimental setup and evaluation to ensure fairness.

4. Proposed Research System

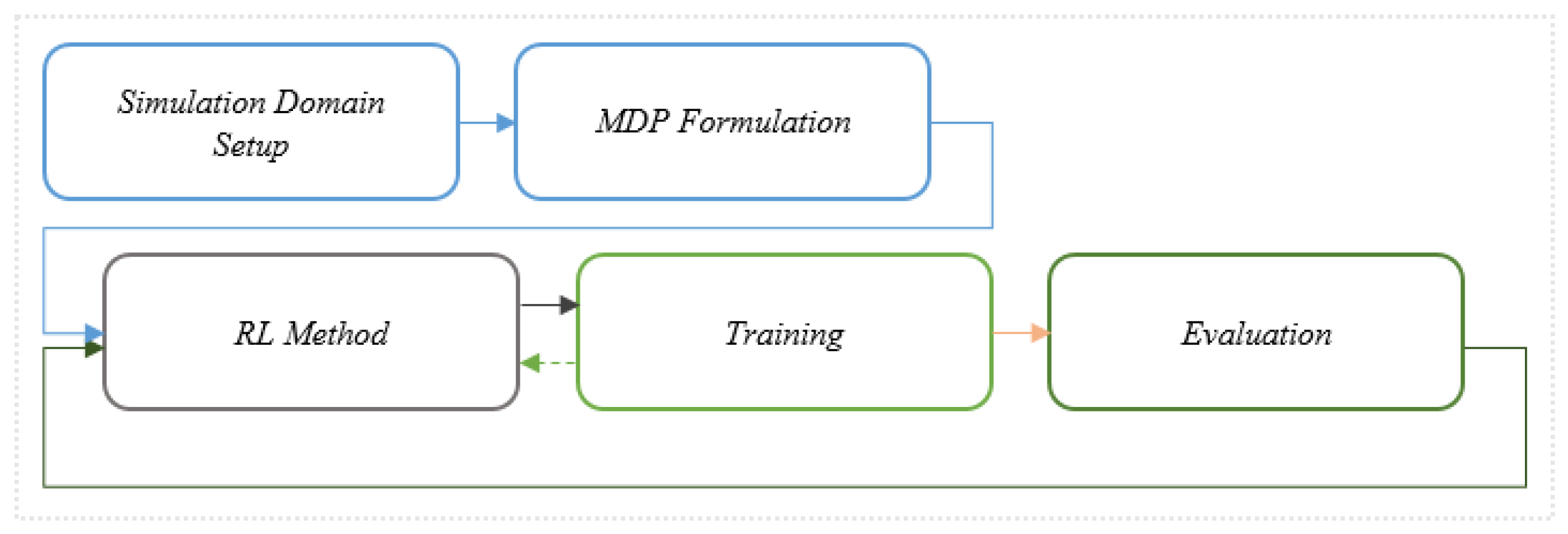

The proposal of this study emphasizes the

importance of adhering to a rigorous methodology in order to enable experiment

reproducibility and result comparison based on the traffic conditions in Korea.

The methodology employed is a slightly adapted version of Varela, which is a

reinforcement learning-based adaptive traffic signal control methodology for

multi-agent coordination. While the existing methodologies for independent

learners consist of four steps, this study extends it to two additional steps,

namely MDP formulation and RL method, as distinct components. The five steps

include simulation setup, MDP formulation, RL method, training, and evaluation

as followings in

Figure 1.

Since Markov Decision Process (MDP) defines the

optimization problem, meaningful comparisons between different reinforcement

learning methods require the same underlying MDP. Moreover, the MDP formulation

can have a decisive impact on the performance of the reinforcement learning

model. This has been demonstrated by keeping the learning algorithm fixed and

altering the underlying MDP formulation. In this study, we keep the underlying

MDP fixed and test different baselines and RL-based methods, evaluating

separate function approximations, adjustment methods, and observation scopes.

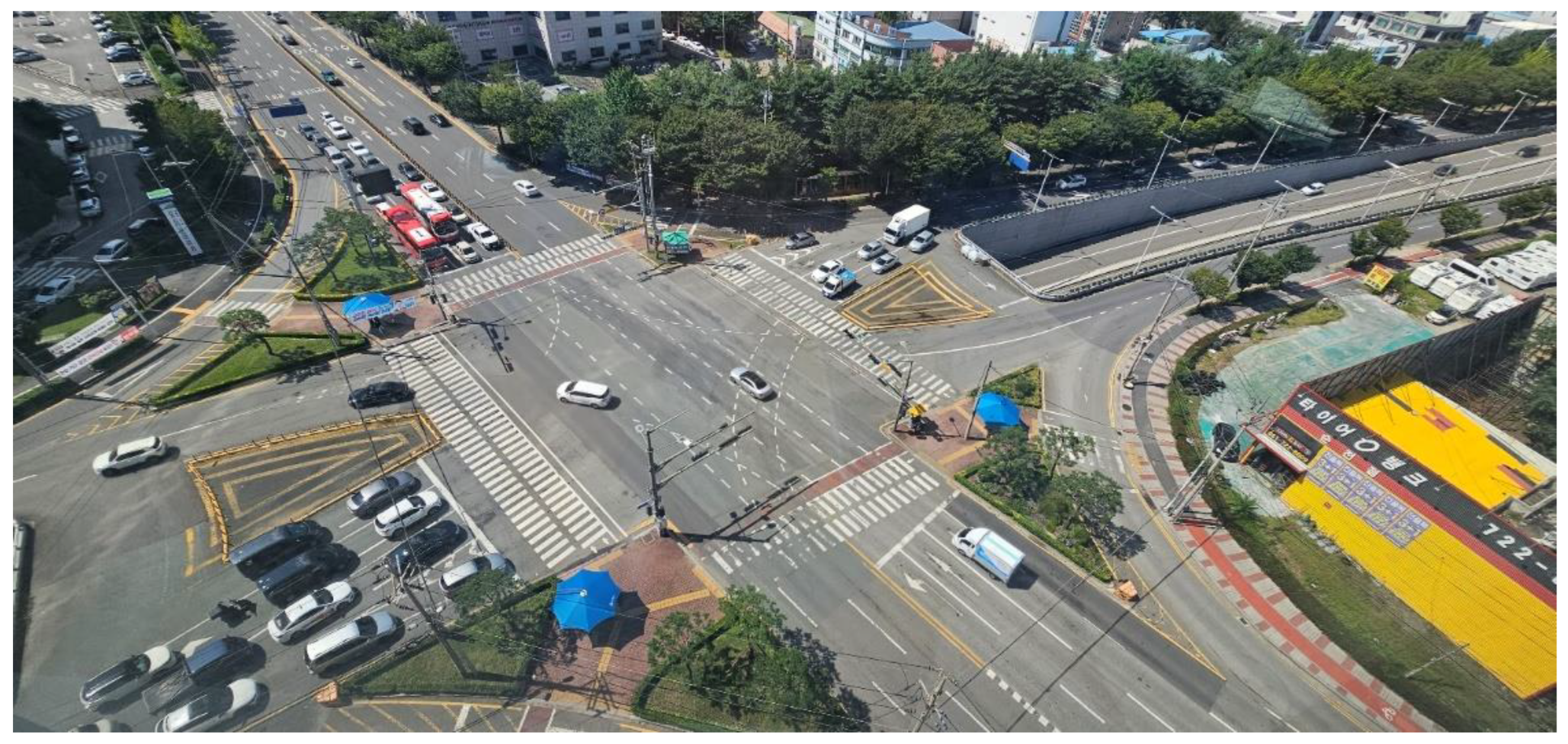

4.1. Simulation Domain Setup

The first step of the proposed methodology is

simulation domain setup, which is composed based on the choice of traffic

conditions. A realistic modeling is used for the agent to train and learn

effective traffic control policies, defining the network topology used in the

simulator, and specifying the traffic demand, which is derived from Suncheon

City in Korea. Unlike traffic macro simulators that simulate the overall

traffic flow, traffic micro modeling simulate individual vehicle attributes

such as position, velocity, acceleration, route, and emission rate for each

vehicle from real environment. These have been used to evaluate current traffic

controllers and prototype new traffic controllers, and can be used in the

context of reinforcement learning to model the environment in which the agent

learns traffic policies in

Figure 2.

4.2. MNT(Motorway Networks Topology)-Based MDP Formulation

It is possible to extract the network from

real-world locations. By leveraging available open-source services, it is

feasible to export parts of urban areas, and by preparing this information

during the simulation setup phase, it can be provided to the simulator, opening

up the possibility to simulate a rich set of networks related to real traffic

signal control.

Unfortunately, Real-world data can generate

realistic traffic demands that match actual observations, reducing the gap

between the simulator and the deployed traffic controllers in the real world.

However, this data needs to be validated before being used and the setup

process can be complex as it is often specific to the network. Acquiring such

data can be challenging, and it may be noisy or even unavailable. Therefore,

data-driven traffic demands fall outside the scope of this research.

MDP (Markov Decision Process) consists of state

features, reward signals, action schemes, and observation scope. A group of

collaborating multi agent-based DRL is defined by a MDP that accounts for the

lack of observability and interactions. The MDP is defined by the tuple is

shown as Equation (1) in

Figure 2.

State space S (s∈S) is represents the state at time

t, composed of features of incoming approaches at intersections. In this

research, The equation is described by feature maps ϕ

(s) composed of data on internal states

and incoming approaches by shown as Equation (2).

The internal state is defined by the index of the

current green phase,

, where

P is the number of phases, and the

time since this phase has been active,

. The feature

on the incoming approaches of any given agent

n

at phase

p is defined by the cumulative delay by shown as Equation (3).

Here, is the speed of the vehicle in the incoming

approach of step p for the agent, and is the speed limit for step r. No delay

occurs if all vehicles travel at the speed limit for each step, or if there are

no vehicles in a step. If a vehicle travels slower than the speed limit, the

delay becomes positive until it reaches the maximum stop (v = 0), and

the delay becomes a maximum of 1. Mostly, this choice was influenced by the

research done by Pedro theory.

4.3. DRL (Deep Reinforcement Learning) Approaches

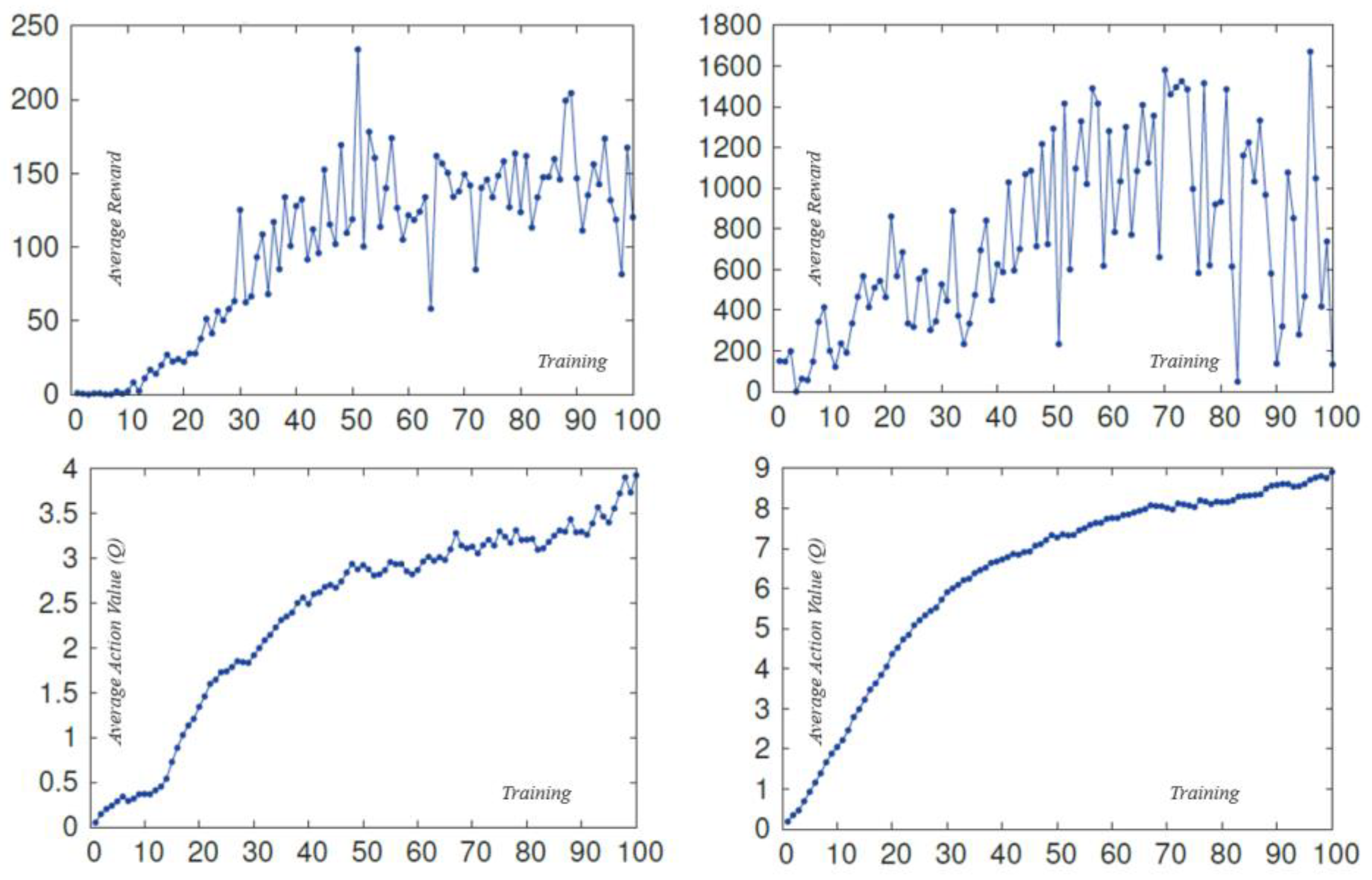

The DRL (Deep Reinforcement Learning) method

consists of learning algorithms with different function approximation methods,

adjustment methods, and observation scopes. In this task, agent coordination is

achieved using the QL algorithm for the domain and some of its variations. It

should be noted that (i) the QL algorithm receives a discrete state space, so

it is necessary to discretize the state defined in the previous MDP formula.

(ii) In this algorithm, each intersection must share its state and behavior

during training and share its state during execution.

Deep QL (Deep Q-Learning) is a type of

reinforcement learning that explores a non-deterministic environment and

selects the best action based on experience. Deep QL learns based on the

concepts of state, action, and reward. When time is denoted as t, the situation

of the environment is defined as a state (

). When an action (

) is taken in a state, a reward (

) is given, and the system transitions to the next

state (

) by shown as Equation (4).

The set of states for a total of

n states

and

m actions is represented by equation (5), and the set of actions is

represented by equation (6). Each state, action, and reward has a Q-function,

denoted by equation (7).

The learning values in Deep Q-Learning are stored

in a Q-table. In this case, the value is obtained from the maximum value among

the values for the current state, action, and reward (

) and the new state (

Q(

,

)). This is done using the learning rate (lr, α)

and the discount factor (df, γ) by shown as Equation (8).

In general, Deep Q-Learning involves exploration, where actions are chosen based on the state and reward. When selecting actions, occasionally trying out new actions can lead to better results rather than solely relying on the actions that yield the highest immediate rewards. Therefore, the concept of exploration with randomness is applied, known as epsilon-greedy selection. This research proposes a traffic signal control system using Deep Q-Learning in a multi-intersection setting. Each intersection is equipped with a local agent (

), and each agent independently performs Deep Q-Learning based on the time information of the waiting vehicles from neighboring intersections that are aiming to enter the respective intersection. Accordingly, we have our research approaches for it, during training, certain procedures of simulations and algorithm rely on random number generators. Simply changing the seed of these generators can statistically induce significant differences in the performance of the implemented traffic controllers. Due to this variance, multiple independent training runs are seeded for each controller, and the results are averaged across each controller to obtain performance outcomes that reflect how the traffic controller actually performs. These random seeds also allow for complete replication of all experiments. The DRL process involves exploration and exploitation phases, where congestion can occur in the network during simulations, preventing vehicles from moving through the road network. This can happen more frequently during the exploration phase, where actions are randomly selected by the agent. When congestion occurs, the agent halts learning, and the simulation essentially comes to a halt. To avoid congestion, the reinforcement learning task is episodic, where the simulator is reset after a set time to prevent unfavorable outcomes from persisting indefinitely. There are two main performance metrics and two auxiliary performance metrics. The reason for the reward to increase during training is to allow the agent to make better decisions and indicate that the generated policy, such as in deep reinforcement learning models like DQN, is approaching stable state preservation. The other two auxiliary metrics are the average number of vehicles in the road network and the average speed. As training progresses, the agent should be able to make better decisions reflecting a decrease in the average number of vehicles in the network as it becomes more dispersed and an increase in average speed in

Figure 3.

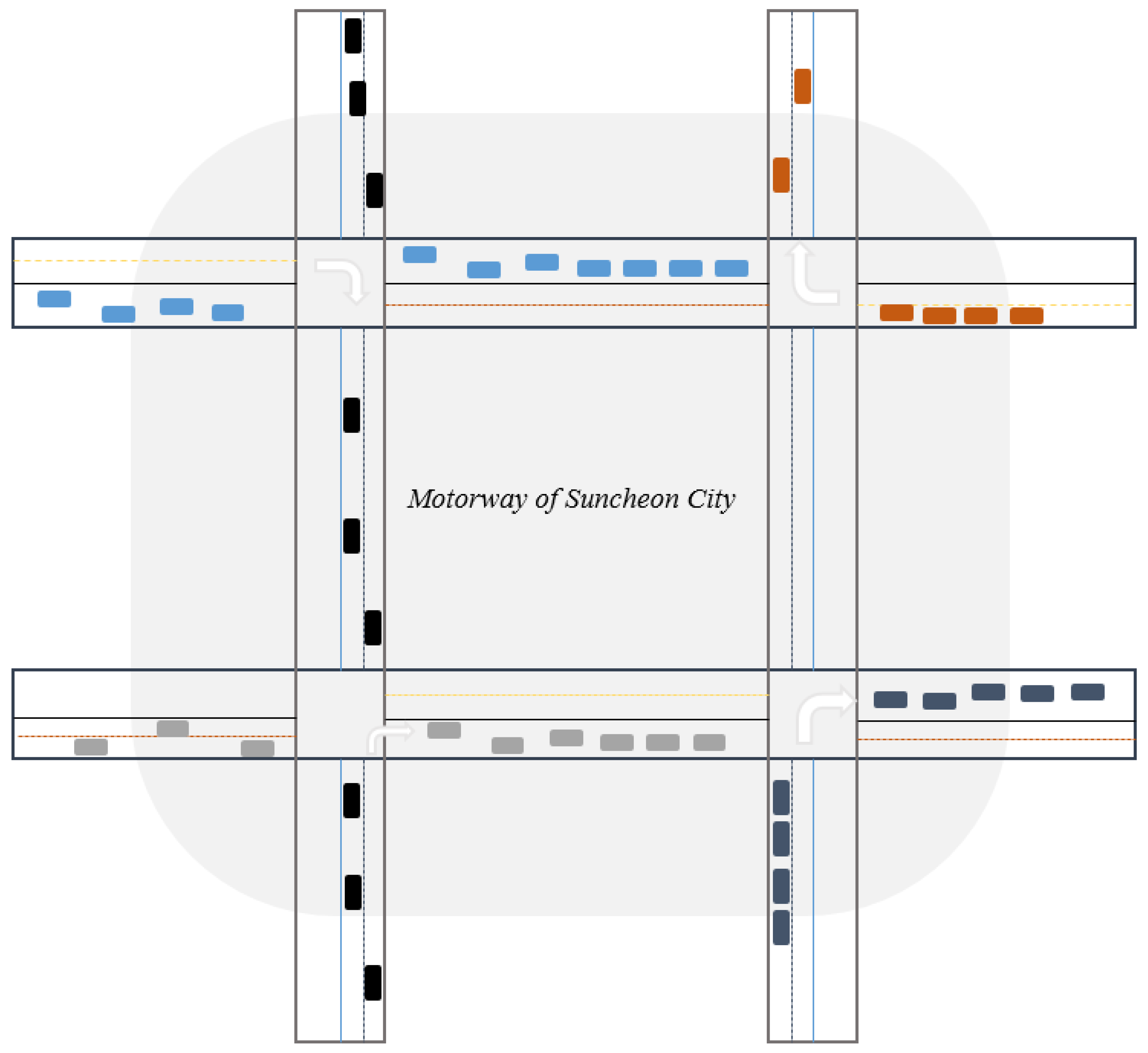

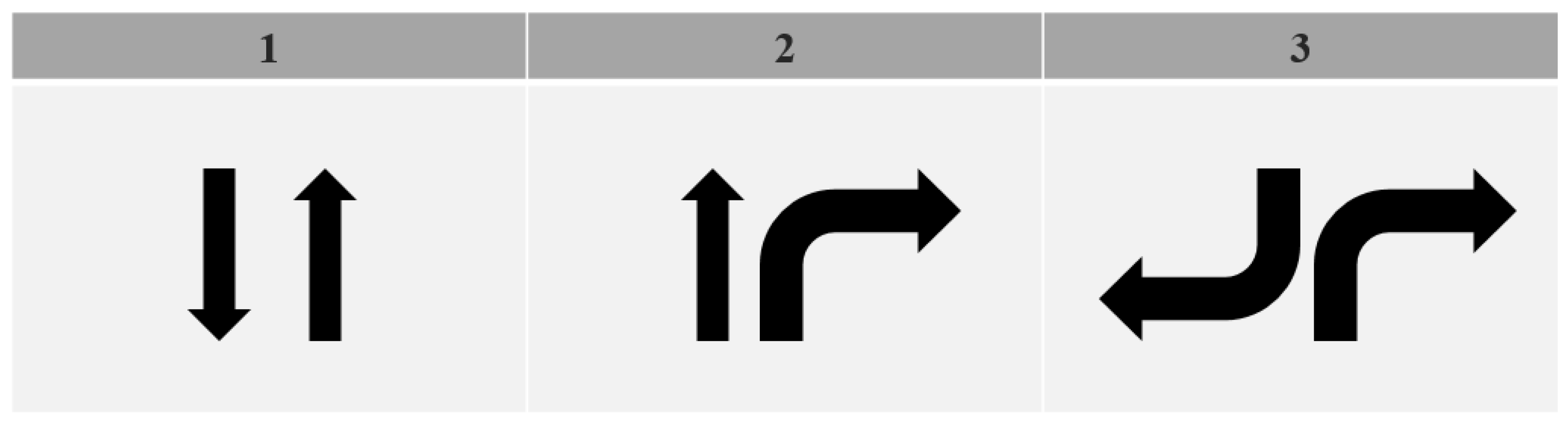

Here, the state of DQL (Deep Q-Learning) is defined as the number of available directions for vehicles to move at a given intersection. For example, in

Figure 4, it is a 4-way intersection with 4 adjacent directions. Each direction at a 4-way intersection allows for left turns and straight movements. Therefore, the state of a 4-way intersection can be classified into 8 categories (( S= {

}). The actions in the proposed DQL consist of the possible actions to take at the intersection, and there are three action sets as shown in

Figure 5 (A = {

}).

At time t, the reward (

) of the local agent at an intersection is composed of the throughput (

) and the average waiting time (

wt) of adjacent intersections, as shown in Equation 9. The throughput represents the number of vehicles processed at intersection

i within a unit time, while the waiting time is the average waiting time of vehicles at intersection

i and its adjacent intersections. The weights (α) are used to adjust the importance of throughput and waiting time, with

w greater than 1 and ξ defined between 0 and 1.

5. Discussion

This research paper proposes a traffic signal control method using Deep Q-learning for multi-intersection of motorway of Suncheon City in Korea. The objective of this research is to maximize the throughput and minimize the waiting time at intersections through collaboration with neighboring intersections. To evaluate the performance of the proposed system, it is compared with fixed-time signal control and adaptive signal control methods. The results show that when using DRL-TCS (Deep Reinforcement Learning Traffic Control System) on 4 neighboring intersections, the proposed method outperforms in terms of average queue length, throughput, and waiting time. However, for larger intersections, using only a distributed approach may not be sufficient for traffic control. Therefore, further research on a deep learning-based traffic signal method that combines distributed and centralized approaches is needed to address this limitation.

Author Contributions

Y.J.O is an expert in the field of artificial intelligence, augmented reality, metaverse and intelligent vehicle research, actively participating in various national projects in Korea. She contributes to algorithm development and conducts experiments using simulations. She has granted permission for the publication of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Xiaofeng Liu, Ben St. Amour and Arunita Jaekel. A Reinforcement Learning-Based Congestion Control Approach for V2V Communication in VANET. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3640. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakopoulos, G.; Demestichas, P. Intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 2010, 5, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society of Automotive Engineers. SAE J2735: Dedicated Short Range Communications (DSRC) Message Set Dictionary; Technical Report; Society of Automotive Engineers: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2009.

- Bansal, G.; Lu, H.; Kenney, J.B.; Poellabauer, C. EMBARC: Error model based adaptive rate control for vehicle-to-vehicle communications. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM International Workshop on Vehicular Inter-Networking, Systems, and Applications, 2013, Taipei, Taiwan, 25 June 2013; pp. 41–50.

- Ogura, K.; Katto, J.; Takai, M. BRAEVE: Stable and adaptive BSM rate control over IEEE802. In 11p vehicular networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 10th Consumer Communications and Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–14 January 2013; pp. 745–748. [Google Scholar]

- F. Sivrikaya, N. Ben-sassi, X. Dang, O. Can Gorur, and C. Kuster, “Internet of smart city objects: a distributed framework for service discovery and composition. J. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 14434–14454. [CrossRef]

- B. Jang, M. Kim, G. Harerimana, and J. Kim, “Q-learning algorithms: a comprehensive classification and applications,”. J. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 133653–133667. [CrossRef]

- X. Liang, X. Du, G. Wang, and Z. Han, “A deep reinforcement learning network for traffic light cycle control,”. J. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 1243–1253. [CrossRef]

- H. Nguyen, L. Kieu, T. Wen, and C. Cai, “Deep learning methods in transportation domain: a review,”. J. IET Intell. Transportation Syst. 2018, 12, 998–1004. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M.; Rambabu, C.; Chandrasekaran, G.; Kumar, N.S. A Traffic Density-Based Congestion Control Method for VANETs. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 7551535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Panjeta, M. Optimization transmit rate-based decentralized congestion control scheme in vehicular ad hoc networks. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2555, 030006. [Google Scholar]

- LucasV.Bonfati,José J. A. Mendes Junior,Hugo Valadares Siqueira and Sergio L. Stevan, Jr., Correlation Analysis of In-Vehicle Sensors Data and Driver Signals in Identifying Driving and Driver Behaviors. Senors 2023, 23, 263.

- Rodrigues, J. G. P.; Vieira, F.; Vinhoza, T. T. V.; Barros, J.; Cunha, J. P. S. A non-intrusive multi-sensor system for characterizing driver behavior. In Proceedings of the 13th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Funchal, Madeira Island, Portugal, 19–22 September 2010; IEEE: Madeira Island, Portugal, 2010; pp. 1620–1624, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rebolledo-Mendez,G.; Reyes, A.; Paszkowicz, S.; Domingo, M. C.; Skrypchuk, L. Developing a Body Sensor Network to Detect Emotions During Driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2014, 15, 1850–1854. [CrossRef]

- McCall, J. C.; Trivedi, M. M. Driver Behavior and Situation Aware Brake Assistance for Intelligent Vehicles. Proc. IEEE 2007, 95, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Baek, Y. NETTED:Non-Standard CANID Extraction System Based on Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 3rd International Conferenceon Communication and Information Systems (ICCIS), Singapore, 28–30 December 2018; IEEE: Singapore, 2018; pp. 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, F.; Mercaldo, F.; Orlando, A. ; Nardone,V.; Santone, A.; Sangaiah, A. K. Human behavior characterization for driving style recognition in vehicle system. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 83, 102504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Filev, D.; Prakah-Asante, K.; Tseng, F.; Kolmanovsky, I. V. From vehicle stability control to intelligent personal minder: Real-time vehicle handling limit warning and driver style characterization. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Workshop on Computational Intelligence in Vehicles and Vehicular Systems, Nashville, TN, USA, 30 March–2 April 2009; IEEE: Nashville, TN, USA, 2009; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Filev, D.; Lu, J.; Tseng, F.; Prakah-Asante, K. Real-time driver characterization during car following using stochastic evolving models. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Anchorage, AK, USA, 9–12 October 2011; IEEE: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2011; pp. 1031–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Raz, O.; Fleishman, H.; Mulchadsky, I. System and Method for Vehicle Driver Behavior Analysis and Evaluation. U.S. Patent US7389178B2; 17 June 2008. 21,

- Obuhuma, J.; Okoyo, H.; Mcoyowo, S. Real-time Driver Advisory Model: Intelligent Transportation Systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 (IST-Africa) Week Conference (IST-Africa), Gaborone, Botswana, 9–11 May 2018. 11. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. Q.; Lee, S. A Comprehensive Survey of Driving Monitoring and Assistance Systems. Sensors 2019, 19, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHTSA. Critical Reasons for Crashes Investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey. Traffic Safety Facts Crash Stats 2018. Number:DOTHS812506. Available online: https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812506 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Petridou, E.; Moustaki, M. Human Factors in the Causation of Road Traffic Crashes. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 16, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattanzi, E.; Freschi, V. Machine Learning Techniques to Identify Unsafe Driving Behavior by Means of In-Vehicle SensorData. Expert Syst. App l. 2021, 176, 114818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadano, Y. S.; Potgieter-Vermaak, S.; Kachba, Y. R.; Chiroli, D. M.; Casacio, L.; Santos-Silva, J. C.; Moreira, C. A.; Machado, V.; Alves, T. A.; Siqueira, H.; et al. Dynamic model to predict the association between airquality, COVID-19 cases, and level oflockdown. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xuan, K.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, W.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Cao, X.; Hao, X.; et al. Quantitative of instantaneous BC emissions based on vehicle specific power from real-world driving diesel trucks in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 819, 153230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, S.; Ramadurai, G.; Nagendra, S.S. On-board measurement of emissions from freight trucks in urban arterials: Effect of operating conditions, emission standards, and truck size. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 212, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Eisaeia, M.; Moridpourb, S.; Tay, R. Heavy Vehicle Management: Restriction Strategies. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 21, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.; Fan, W.D. Evaluating impacts on freeway capacity using VISSIM: Accounting for truck lane restrictions, driver behavior, and interchange density. Adv. Transp. Stud. 2011, 25, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Siuhi, S.; Mussa, R. Simulation Analysis of Truck-Restricted and High-Occupancy Vehicle Lanes. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2007, 2012, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnell, J.; Sebben, S.; Elofsson, P. Experimental investigation of a two-truck platoon considering inter-vehicle distance, lateral offset and yaw. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 213, 104596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnam, S.; Menendez, M. Analysis of strategies for truck platooning: Hybrid strategy. Transp. Res. Rec. 2016, 254, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Calvert, S.; Schakel, W.; van Arem, B. Evaluation and modelling of the traffic flow effects of truck platooning. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 105, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čičić, M.; Pasquale, C.; Siri, S.; Sacone, S.; Johansson, K.H. Platoon-actuated variable area mainstream traffic control for bot-tleneck decongestion. Eur. J. Control 2022, 68, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacentini, G.; Pasquale, C.; Sacone, S.; Siri, S.; Ferrara, A. Multiple Moving Bottlenecks for Traffic Control in Freeway Systems; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Naples, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duret, A.; Wang, M.; Ladino, A. A hierarchical approach for splitting truck platoons near network discontinuities. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 132, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yan, X.; Yin, Y. Truck routing and platooning optimization considering drivers’ mandatory breaks. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 143, 103809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang Gao, Long Chen, Kuan Wang, Xiaoxia Xiong, Hai Wang, and Yicheng Li, Improved Traffic Sign Detection Algorithm Based on Faster R-CNN, Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8948. [CrossRef]

- A Technical Overview of Transportation Electrification. In EPRI Technical Report; EPRI Customer Assistance Center: Dallas, TX, USA; Columbus, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, K.; Zhou, C.; Allan, M.; Yuan, Y. Modeling of load demand due to EV battery charging in distribution systems. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 2011, 26, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datchanamoorthy, S.; Kumar, S.; Ozturk, Y.; Lee, G. Optimal Time of use Pricing for Residential Load Control. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (Smart Grid Communications), Brussels, Belgium, 19–20 October 2011; pp. 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Kim, C.; Sung, B. Analysis of Daily Load Patterns Taking into Consideration PEVs Charging Stations in Seoul, South Korea. Energies 2021, 14, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.Y. Trajectory Data Based Clustering and Feature Analysis of Vehicle Lane-Changing Behavior. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Electromechanical Control Technology and Transportation (ICECTT), Guilin, China, 26–28 April 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, K.; Wu, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ran, B. An integrated car-following and lane changing vehicle trajectory prediction algorithm based on a deep neural network. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2022, 599, 127303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).