1. Introduction

Scientists, politicians, and practitioners are debating the current structure of pig farms in Lithuania, as medium and small farms have almost disappeared over the past decade. The debated problem is whether the revitalization of medium and small pig farms would sustainably contribute to self-sufficiency in pork? It should be emphasized that self-sufficiency in pork has been constantly decreasing and currently meets less than half of the required own production of pork and its products.

The aim of the research is to determine which farms in terms of size could be the most perspective after evaluating the most important indicators of farm competitiveness and choosing the appropriate method for ranking. In order to achieve this aim, domestic and foreign scientific research on the problems of pig farming, the systems of indicators used in the research and methods applied were analyzed. The paper presents the economic, production and environmental situation of Lithuanian pig farms and pig farming sector in Lithuania and selected EU countries: Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Germany, and Denmark.

The research revealed that in Lithuania, according to all selected indicators, large farms developed most successfully. The same dynamics was observed in the countries chosen for the research.

The multi-criteria evaluation method TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution) was used in the research, with the help of which the criterion estimate was determined using the most important activity indicators and the farms according to it were ranked.

The multi-criteria evaluation led to the conclusion that Danish pig farms were the best managed. Germany occupied the second place. The industrial large farms were found as dominated in those countries.

Large pig farms (approximately two thousand sows) appeared most perspective in Lithuania: they took the first place in the years examined (2016–2021). The criterion estimate of their assessed indicators was much higher than the criterion estimates of the medium (100 sows) and small (20 sows) farms analyzed. The main reasons: significantly higher labour productivity, lower cost, lower price, and better production indicators.

The bibliometric analysis on the research topic was used to conduct the literature review. The greatest value of bibliometric analysis is its power to reveal trends in scientific knowledge in a given field of research and, as Donthu et al. [

1] note, it has become very widespread in business research in recent years. The bibliometric analysis is a sufficiently novel tool for analysing scientific literature, but it has been applied to analysing agricultural research, as for an example, to assess the trajectories of efficiency measurement [

2]; agricultural co-operatives in western countries [

3], to investigate farmers’ market actors, dynamics, and attributes [

4], to map innovative business models for vertical farm entrepreneurs [

5], to provide knowledge on alternative sustainable agricultural systems [

6]. Research trends related to the pig sector in relation to environmental and economic issues have scarcely investigated, so a bibliometric survey of journals, authors, institutions and countries carried out to fill this gap. The literature review was based on a search of the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection on 28 March 2023 for articles published according to themes: Agricultural Policy, Economics, Climate Change and Environmental Sciences. On the WoS website (

https://www.webofscience.com/), the following query string search was processed in the search engine: TOPIC (searches title, abstract, author keywords, Keywords plus) = “pig farm*” OR “swine farm*”. The bibliometric mapping of the keywords found in the publications was done using the bibliometric software Visualisation of Similarities (VOS) viewer (VOSviewer) developed by van Eck and Waltman [

7].

A total of 207 publications were retrieved from the database.

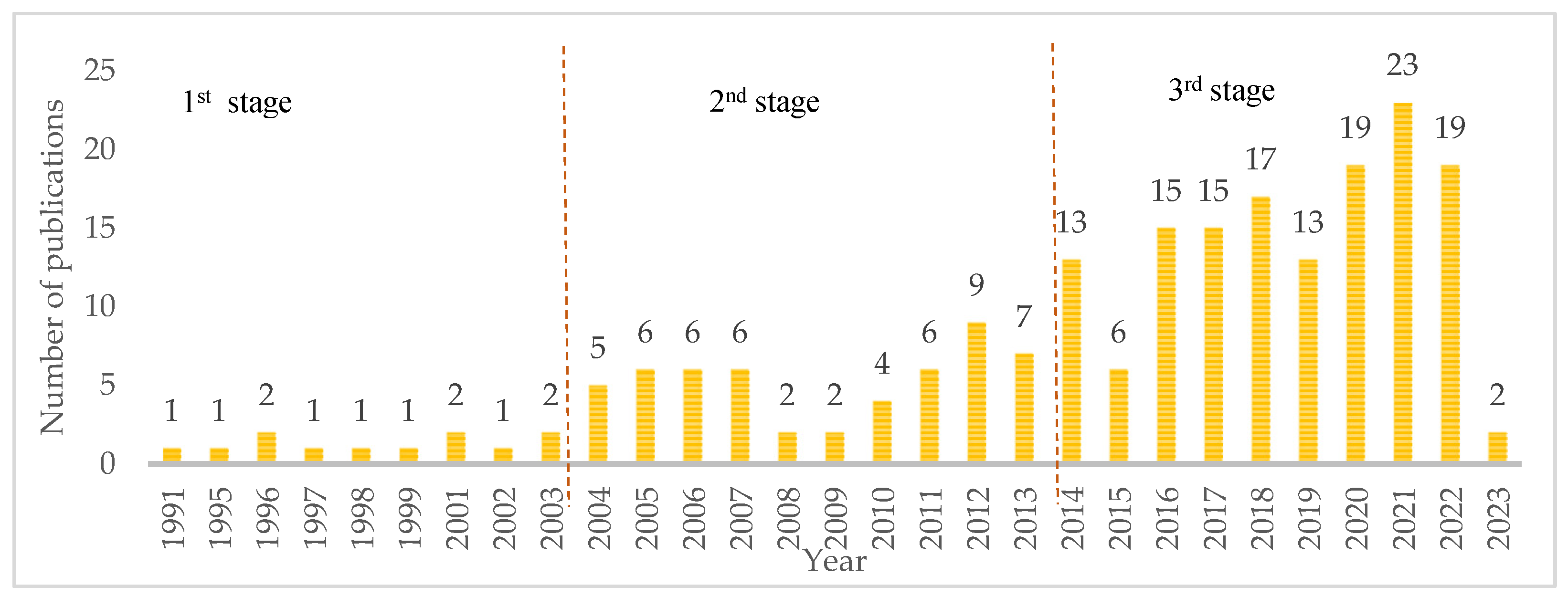

Figure 1 shows the increase in the number of publications focusing on pig farming each year, in relation to aspects of agricultural policy (economic, environmental, and social) as a research topic. The entire research period (1991–2023) could be divided into three stages, based on the change and increase in the number of publications. The first stage is from 1991 to 2003, when an average of 1.3 articles were published per year. The second stage, from 2004 to 2013, reveals a greater interest of researchers in this field, with an upward trend in the number of publications. The third stage, which can be described as a phase of slow growth of publications, accounted for 68% of all publications during the period analyzed (

Figure 1).

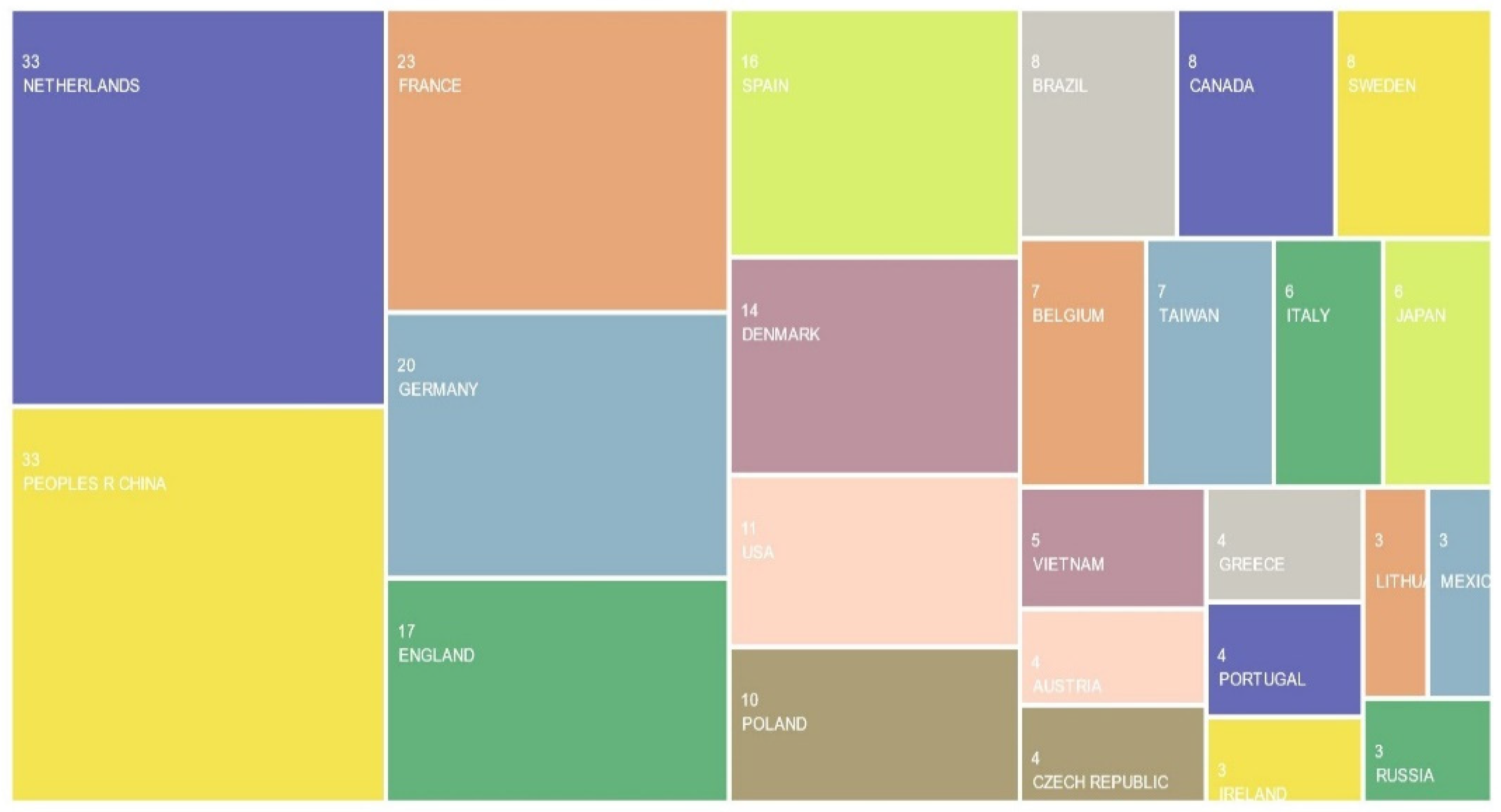

The topic of pig farming in the context of agricultural policy covers 25 countries (

Figure 2). The analysis of country contributions shows that the Netherlands and China have the highest number of publications (33 publications each), followed by France (23 articles) and Germany (20 articles). The European region contributes 68% of all publications. Lithuanian researchers contributed only three publications – Jurkėnaitė and Paparas [

8], Jurkėnaitė and Syp [

9] and Venslauskas et al. [

10].

All keywords analysis (with fractional counting method) was carried out to identify the main research ideas and directions within pig farming related to agricultural policy of the publications in a given period of time. A minimum of five (5) occurrences of the keyword was applied as a threshold factor. Thus, out of 1098 keywords from 207 publications, only 61 keywords met the threshold. The overlay visualization of keywords discloses the main topics from 2014 (marked in yellow) to 2020 (marked in blue). The keywords were formed to five clusters and uncovered the following research topics: cluster 1 (covering environmental issues such as ammonia emissions, manure management, biogas); cluster 2 (related to the assessment of the system and covering life cycle analysis, carbon footprint); cluster 3 (dealing with productivity, efficiency measures); cluster 4 (concerning to the meat, food, market) and cluster 5 (involving food safety, production systems). To summarize the studies mentioned earlier by Lithuanian researchers, it can be stated that the research of Venslauskas et al. [

10] is connected with 1 cluster topics, while the research of Jurkėnaitė and Paparas [

8], Jurkėnaitė and Syp [

9] are linked with 4 cluster topics. The results of the analysis of articles confirmed that sustainability issues are increasingly being addressed, but there is a lack of attention to the perspective size of pig farms as one of the key factors determining farm productivity, efficiency, and welfare of pigs.

Figure 3.

The bibliometric map of keywords “pig farm” or “swine farm”.

Figure 3.

The bibliometric map of keywords “pig farm” or “swine farm”.

There are limited studies on determining the perspective farm size. The most recent studies include the research on the U-shaped relationship between farm productivity and farm scale based on Indian data [

11], on the relationship between farm size and efficiency in wheat farm in the European Union [

12] and the relationship between farm size and agricultural production efficiency in Chinese agriculture [

13].

Huong et al. [

14] analyzed technical efficiency of pig production in Vietnam. Their findings in relation to herd size disclose that increasing herd size reduces the technical efficiency of large-scale industrial farms but increases the technical efficiency of smaller traditional farms.

Given the literature review, it can be argued that pig farming is still a neglected issue in the context of agricultural policy, economics, climate change and environmental issues, and this study will contribute to the development of research in this area.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to achieve the aim of this research – to determine which pig farms in terms of size could be the most perspective – the comparative analysis of pig farming sector in Lithuania and selected neighboring countries Latvia and Estonia with the similar conditions and experience, Poland with low pork prices, Denmark and Germany as dominant actors in the EU pig farming sector, was carried out, in order to better understand structural situation in selected countries.

Labour productivity (thou Eur/AWU), self-sufficiency, (pct), feed price index, pork price (Eur/t), average number of pigs in the farm (ln), which describe the competitiveness and profitability of the farms, were used in order to determine in which country pig farms were managed better.

Five most important physical and economic indicators, reflecting the essence of the perspective farm were chosen for this research: price (Eur/t), cost (Eur/t), labour productivity (Eur/AWU), number of piglets (per sow per year), production (kg per pig per year), were used to determine the perspective pig farm in Lithuania. In line with situation, observed in Lithuania, it was assumed that large farms are when have 2 thousand sows, medium – 100 sows, and small – 20 sows.

Method of multi-criteria evaluation was used for both: to evaluate in which country pig farms are managed better, and to determine the perspective pig farm size in Lithuania, considering above mentioned their performance indicators.

In this article, we applied the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) multi-criteria evaluation method. Using TOPSIS criterion estimate was calculated, which was obtained from different indicators. This method was used to estimate the perspective farm size in pig farming sector. The TOPSIS method used vector normalization:

().

The main criterion of the TOPSIS method was calculated according to the distances to the best and worst options (solutions):

where: and – the total distance of the –th alternative to the best and worst options (solutions), respectively.

and

were calculated according to the following formulas:

where:

and

– the best and worst option (solution) for each criterion

, respectively:

where: – set of indices of maximizing indicators, – set of indices of minimizing indicators.

The maximum value of the TOPSIS criterion corresponds to the best alternative.

The main research period is 2016–2021. The period for this research was chosen in order to eliminate the influence of the cyclicity of pigs on the results. Data from the Eurostat, State Data Agency, Agricultural Data Centre, Agricultural companies, and farms were used in this research.

3. Results

3.1. Pig farming particularities in Lithuania

The pig farming sector is one of the most economically important sectors of the Lithuanian agriculture. Starting from the 2004 until 2017 pig production occupied the second place in animal production after the milk. Later, in the period of 2018–2021, pig production felt to the third position after milk and poultry production [

15]. However, pig production has been on a downward trend since Lithuania’s accession to the EU, with a negative annual growth rate of –1.3% between 2004 and 2021. It can be stated that the pork production in Lithuania has undergone many changes over the last decades. According to the data published by the Lithuanian Agricultural Data Centre [

15], the number of pigs at the beginning of 2022 was 1.8 times lower than in 2004, with an annual negative growth rate of –3.4%. The number of pig farms in Lithuania has fallen more than 20 times between 2003 and 2020, from 169,2 to 8,4 thousand units. The structure of farms has changed from family operations with a herd size of 3–9 pigs, which accounted for about one third of pig farms in 2003, to large-scale pig farms with a herd size of more than 5 thousand pigs, which accounted for 87.6% in 2020.

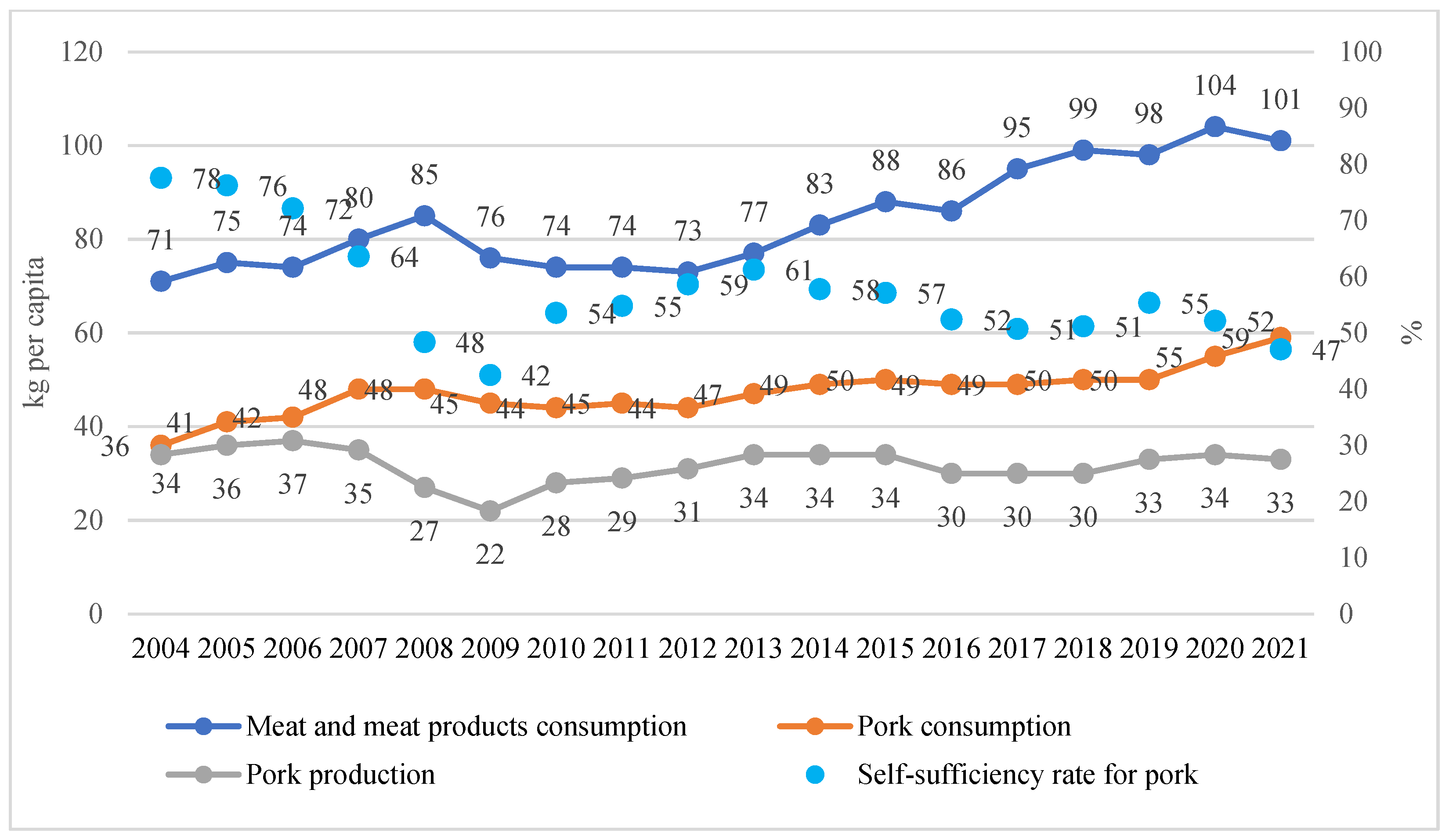

There was observed an increasing tendency of meat consumption per capita during 2004–2021. Per capita consumption of pork has also increased steadily over the last decade, reaching 59 kg in 2021, accounting for 58.4% of total meat consumption. While per capita production has remained stable, the self-sufficiency rate has gradually decreased from 78% in 2004 to 47% in 2021 (

Figure 4). To meet the rest of the demand, pork was imported into the country and in 2021 pork imports accounted for around two thirds of the production level [

15].

Additional problems related to the pig farming were exacerbated by outbreaks of African swine fever. According to the State Food and Veterinary Service, since 2014, when African swine fever was first reported in Lithuania, the country's farms have lost almost 78,0 thousands pigs [

16].

The resilience of farms in the pig farming sector was put to the test during the Covid-19 outbreak. The restrictions imposed by the closure of catering establishments during the pandemic and decrease in export prices caused additional difficulties for pig farms. During the Covid-19 outbreak, Lithuanian agricultural entities received product/service-oriented support in the form of loans to ensure liquidity of the entities, compensation of interest and guarantee premiums for the agricultural and fisheries sectors, and compensation of interest paid on loans and leasing services without guarantee. The support was also provided for specific agricultural sub-sectors such as the poultry and eggs, milk, cattle, pigs, vegetables and fur-bearing animals. Lithuanian agricultural entities could apply for support under the measure „

Exceptional temporary support for farmers and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) particularly affected by the Covid-19 crisis“ under the Lithuanian Rural Development Programme 2014–2020 [

17].

The war in Ukraine after Russia invaded Ukraine (on 24 February 2022) reinforced the effect of Covid-19 as those two crises came so close together [

18]. In case of Lithuania, the prices for energy according to Economic Accounts for Agriculture increased 2.2 times in 2022 compared to 2019 and consequently the compound feeding stuffs for pigs rose by 57% in 2022 (2015=100%) [

19]. The feed is the main component of costs for granivore farms as it comprises approximately two thirds of total cost [

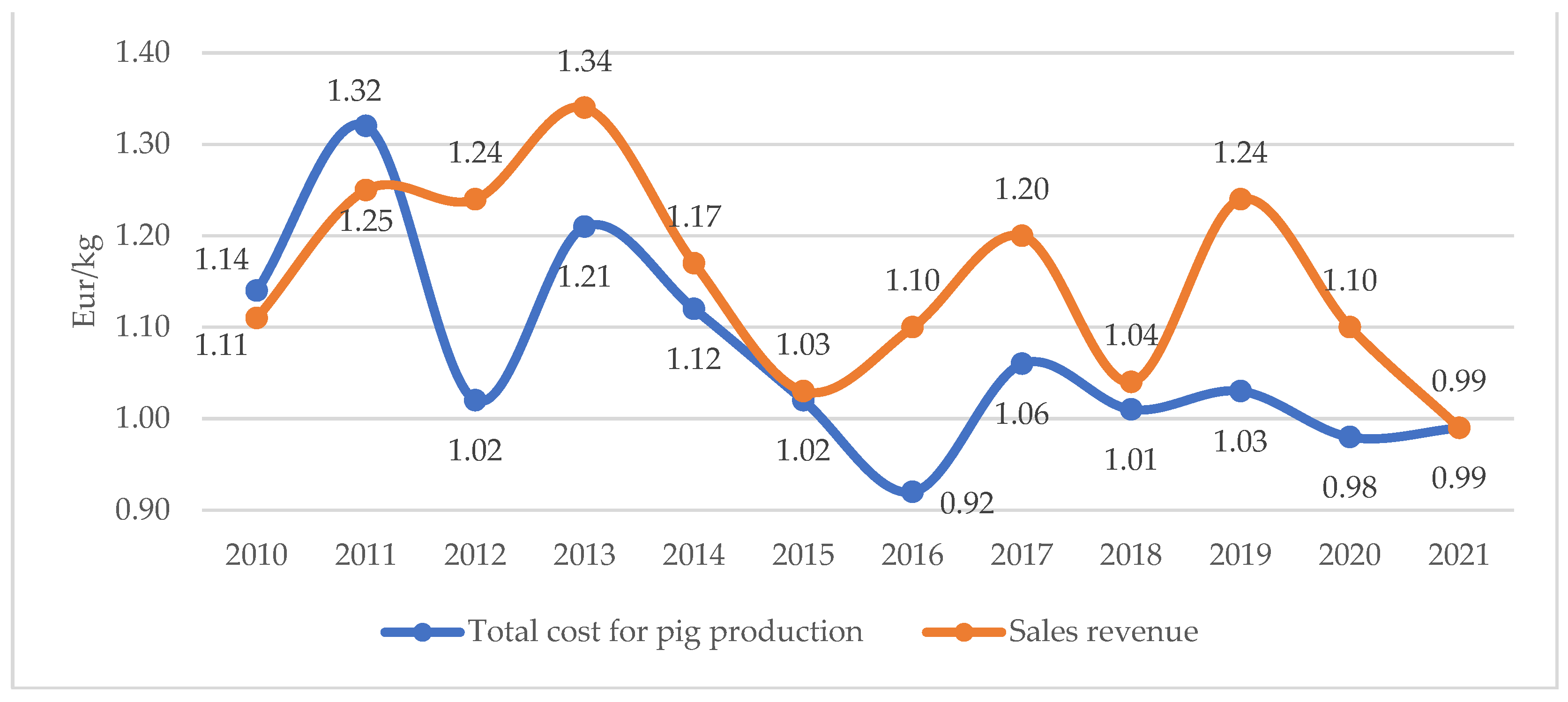

20]. The difference between sales revenue and costs per 1 kg of pig production are presented in

Figure 5.

During the period of 2010–2021 pig farms operated profitably with exception of 2010 and 2011 years, an average profit reached – 0.08 Eur/kg [

21] (

Figure 5). Such a profit could satisfy only large farms, and contrary, small farms had to withdraw from pig farming business.

The other challenges for Lithuanian pig farms are related to the changing animal welfare requirements. In the current unfavorable economic situation of Lithuanian pig farms, the introduction of animal welfare measures, considering European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) [

22] recommendations and implementing the EU’s Green Deal strategy [

23], is becoming a major financial problem. These EU-wide requirements demand a clear implementation of measures and financial support to pig production farms to sustain an already becoming weak sector.

Different situation is being observed in the selected for analysis EU countries. After the 2013 and 2016 (the latest available Agricultural Structure Survey data provided by Eurostat) analysis of the countries neighboring the EU and dominant in the EU pig farming sector, it can be seen that in these countries, during the research period, pig farms had a clear tendency to increase in size. Lithuania stood out as one of the countries where these farms grew the most after Poland. Poland, having a fairly rational structure of farms (i.e., an even distribution of pigs is observed in all groups of farms), although it grew the fastest, but in the final result in 2016 farms with more than 1,0 thousand pigs reached only 37%, when this indicator reached 82% in Lithuania. It is worth noting that in Estonia and Denmark, the farms of the mentioned group had even more pigs – 98%. In Germany, a somewhat different structure of farms is observed in terms of the number of pigs, but a tendency to get larger is also visible.

The largest pig farms, making up a very small proportion of all farms, raise a large proportion of all pigs. This share is particularly large in Lithuania and Latvia: 0.1% farms grow 82% pigs and 0.3% farms – 84% respectively. The balance is much better in the other analyzed countries.

3.2. Evaluation of pig farming in selected EU countries

The analysis of the pig farms of the selected countries revealed that the farms of the countries are very different according to the indicators chosen for analysis, which described the competitiveness and profitability of the farms (

Table 1).

Labour productivity in Lithuania is one-fifth lower than in Germany and higher than in Poland and Latvia (2020). Germany and Denmark are leaders in this indicator. The country's self-sufficiency in self-produced pork is one of the smallest in Lithuania: in 2020 self-sufficiency in pork amounted to 61%, and it was 24 p.p. less than in 2003. The leading countries in pork supply are Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands. It should also be noted that only in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, self-sufficiency did not reach 100%. The feed price change index (when 2015=100) illustrated what is the difference in feed prices in Lithuania and other EU countries. In Lithuania a large increase in prices is observed, in other analyzed countries the price of these fodder also increased, but not as fast as in Lithuania. With the increase in grain purchase prices in Lithuania in 2022 compared to 2015 was almost twice higher and fodder –57% respectively. As for prices, the purchase price of pigs in Estonia and Latvia was similar, the corresponding price in Poland and Denmark was lower by 31 and 26% respectively. The difference of pork price was constantly decreasing during 2003-2020 period. The purchase price of Lithuanian pork was the same as in Denmark and Latvia, and the gap with Poland and Germany decreased by 10 percentage points in 2020. This shows that price convergence process is taking place in Lithuania's favor: the competitiveness of the Lithuanian pig sector is increasing, considering the most important indicator – prices. The average farm size indicator was chosen to evaluate the production concept. In order to eliminate particularly large differences between the selected countries, logarithms were applied to the values.

The

Table 2 presents the cumulative evaluation estimates of the pig farming sector in the selected countries and the place determined by them.

The multi-criteria evaluation method draws to the conclusion that Danish pig farms are the best managed. Germany occupies the second place. Some fragments of those countries management could be applied as good practice in Lithuania.

3.3. Evaluation of the Lithuanian pig farms according to size

In order to answer the question – what the perspective pig farm in Lithuania from the three existing groups of farms is according to the number of sows. Five most important physical and economic indicators, reflecting the essence of the perspective farm were chosen for this research: price (Eur/t), cost (Eur/t), labour productivity (Eur/AWU), number of piglets (per sow per year) and production (kg per pig per year).

The

Table 3 presents the average values of the period from 2016 to 2021, but it is worth to mention, that similar trends are observed when analysing individual years of the period. With higher results of physical and economic indicators, large farms (2 thousand sows) were also able better adopt to changing animal welfare requirements.

As it was mentioned in the methodological section, the period of 2016–2021 for this research was chosen in order to eliminate the influence of the cyclicity of pigs on the results. The

Table 4 presents the results of multi-criteria evaluation based on the data of 2016, 2021 and the average 2016–2021.

Large pig farms (2 thousand sows) currently appear most perspective: they took the first place in all the years examined. The cumulative estimate of their assessed indicators was much higher than the cumulative estimates of the medium (100 sows) and small (20 sows) farms analysed. The main reasons are as follows: significantly higher work productivity, lower cost, lower price, and better structural indicators.

4. Discussion

In the debate on the most perspective size of the farm, the prevailing opinion is that such a sector structure of large pig farming has formed under the Lithuanian conditions due to external and internal factors of the sector, and its contraction in the current period would make Lithuania a net importer of the pork. Such a sector still has potential to evolve it: has qualified employees, it has buildings and infrastructure, but it needs to receive more attention in transforming it into farming that is more environmentally friendly and meets society's expectations. There must be a prompt response to crises in the sector, such as sudden increases in the price of feed components, price drops caused by pig or human diseases (African swine fever, COVID-19, etc.), energy price increases due to the war or other disasters, etc. If there was income support and priority investment support for the pig farming sector, by distinguishing support for animal welfare and reducing the density of pigs, adding additional materials to enable proper investigation and manipulation activities – it is possible to have more favourable health conditions for pigs, use less medication for treatment, have exceptional production quality and promote it to Lithuanian consumers. The infrastructure of Lithuanian pig farms suffered from inconvenience, which related to the lack of financial resources. The main reason is that in 20 years, the pig farming sector received the least amount of support, and as a result, the barns and equipment in most of them are deteriorated, the manure pits have not been replaced, biogas equipment has been installed only where support was granted from the funds for electricity producers. During the crisis, farms are no longer able to repair the most essential structures and update the necessary equipment. If pig farms were encouraged to implement environmental protection measures – renovation of manure systems, conversion of manure and production of biogas/biomethane – pig farming would be more favourable to the environment. Greater attention could be devoted to the modernization and innovation of pig farms. The problem is that support is given to large farms in the same way as to small farms – the amount of support is limited, so the modernization of pig farms is almost non-existent. Farms face the challenge of attracting new employees – this is feels the most in all large farms, but employees leave unattractive positions because they do not see future perspectives, and this further deepens the problems of the sector.

5. Conclusions

The research, using the multi-criteria evaluation method TOPSIS, has revealed that in Lithuania, according to main activity indicators, large farms developed most successfully. The same dynamics were observed in the countries chosen for this research: Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Germany, and Denmark. Small farms faced difficulties and withdrew from the market due to existing economic conditions and stricter environmental requirements.

The self-sufficiency of pork production was one of the smallest in Lithuania: in 2020 self-sufficiency of pork was amounted to 47%, and it was by 31 percentage points less than in 2004. In Latvia, and Estonia the self-sufficiency did not reach 100%, also. The leading countries concerning the self-sufficiency of this product are Denmark and Germany.

In Lithuania, there is a demand for long-term scientific research, which would disclose challenges and problems and would suggest appropriate measures to support the sustainable development of the pig farming sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and A.G.; methodology, I.K., A.G. and V.N.; software, A.G. and I.K.; validation, A.G. and I.K.; formal analysis, I.K., V.D., V.N. and A.G.; investigation, I.K., V.D., V.N. and A.G.; resources, I.K., V.D. and A.G.; data curation, I.K., V.D. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.D., I.K., A.G. and V.N.; writing—review and editing, I.K. and A.G.; visualization, V.D.; supervision, I.K.; project administration, V.N.; funding acquisition, I.K. and V.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport of the Republic of Lithuania (Decree V-585 of 19 April 2022) and the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Lithuania (Decree 4D-194(1.08E) of 24 August 2022).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the head of Lithuanian Pig Producers Association Algis Baravykas for the consultations on sector-specific issues and valuable insights on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Donthu, N., et al., How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of business research, 2021. 133: p. 285-296. [CrossRef]

- Lampe, H.W. and D. Hilgers, Trajectories of efficiency measurement: A bibliometric analysis of DEA and SFA. European journal of operational research, 2015. 240(1): p. 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J., et al., Agricultural Co-operatives in the western world: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of cleaner production, 2020. 273: p. 122945. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Rodrıguez, K., et al., Farmers’ market actors, dynamics, and attributes: A bibliometric study. Sustainability, 11 (3), 745. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Biancone, P.P., et al., Using bibliometric analysis to map innovative business models for vertical farm entrepreneurs. British Food Journal, 2022. 124(7): p. 2239-2261. [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, L., A. Boggia, and L. Paolotti, Sustainable agricultural systems: A bibliometrics analysis of ecological modernization approach. Sustainability, 12 (22), 9635. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. and L. Waltman, Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. scientometrics, 2010. 84(2): p. 523-538. [CrossRef]

- Jurkėnaitė, N. and D. Paparas, Price transmission along the Lithuanian pigmeat supply chain. Ukrainian food journal, 2020. 9(1): p. 240-251. [CrossRef]

- Jurkenaite, N. and A. Syp, Spatial pigmeat price transmission: the case of Lithuania and Poland. Zagadnienia Ekonomiki Rolnej/Problems of Agricultural Economics, 2022(1): p. 87-106. [CrossRef]

- Venslauskas, K., et al., Environmental Impact Assessment of Sustainable Pig Farm via Management of Nutrient and Co-Product Flows in the Farm. Agronomy, 2022. 12(4): p. 760. [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.D. and M.R. Rosenzweig, Are there too many farms in the world? labor market transaction costs, machine capacities, and optimal farm size. Journal of Political Economy, 2022. 130(3): p. 636-680. [CrossRef]

- Skalicky, R., et al., OPTIMAL FARM SIZE AND EFFECTIVENESS OF AGRICULTURE IN THE EU: THE CASE OF WHEAT YIELDS. Transformations in Business & Economics, 2021. 20.

- Yan, J., C. Chen, and B. Hu, Farm size and production efficiency in Chinese agriculture: Output and profit. China Agricultural Economic Review, 2019. 11(1): p. 20-38. [CrossRef]

- HUONG, L.T.T., et al., Development of Livestock Farming System and Technical Efficiency: A Case Study on Pig Production in Vietnam. 2023. [CrossRef]

-

Database of Indicators. 2023. State Data Agency; Available from: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize#/.

-

Beveik dešimtmetį Lietuvoje pasireiškiantis afrikinis kiaulių maras neužleidžia pozicijų. 2023. State Food and Veterinary Service [cited 2023 May 22]; Available from: https://vmvt.lt/naujienos/beveik-desimtmeti-lietuvoje-pasireiskiantis-afrikinis-kiauliu-maras-neuzleidzia-poziciju.

-

Support during the COVID-19 outbreak. 2023. Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Lithuania [cited 2023 May 22]; Available from: https://zum.lrv.lt/lt/nacionaline-parama/valstybes-pagalba-1/pagalba-covid-19-protrukio-laikotarpiu.

- Anghel, V. and E. Jones, Is Europe really forged through crisis? Pandemic EU and the Russia–Ukraine war. Journal of European Public Policy, 2023. 30(4): p. 766-786. [CrossRef]

-

Economic accounts for agriculture - values at current prices. 2023. Eurostat [cited 2023 May 23]; Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/AACT_EAA01__custom_6306803/default/table?lang=en.

-

FADN survey results. 2022. Lithuanian FADN [cited 2023 May 22]; Available from: https://www.vic.lt/leidiniai/.

-

Statistical reports on production-financial indicators of agricultural companies and other agricultural enterprises. 2023. Agricultural Data Center [cited 2023 May 23]; Available from: https://www.vic.lt/statistine-informacija/zemes-ukio-bendroviu-ir-kitu-zemes-ukio-imoniu-gamybiniu-finansiniu-rodikliu-statistines-ataskaitos/.

- Nielsen, S.S., et al., Welfare of pigs on farm. EFSA Journal, 2022. 20(8): p. e07421. [CrossRef]

-

The European Green Deal. 2019. European Commission; Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1588580774040&uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).