1. Introduction

Genetic resources are a global asset of inestimable value for the survival of future generations. The UN Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) [

1] recognises that their conservation, which currently is being lost at a worrying rate, is of critical importance to humankind. In the context of climate change, one of the pressures accelerating biodiversity loss is habitat destruction (e.g., deforestation, urbanisation, and conversion of land for agriculture), leading to the loss of critical habitats for many species. The other factors of pressure are overexploitation, pollution and invasive exotic species. A turn toward a green and sustainable economy is increasingly necessary. In the case of olive groves, the presence of monospecific crops established throughout the Mediterranean basin prevents autochthonous species from persisting over time, being relegated to their conservation in germplasm banks. More than 1,200 different cultivars have been described throughout the Mediterranean basin [

2]. Additionally, there exists enormous biodiversity in the wild olive, a species relegated to the margins of olive groves and relict zones in the Mediterranean Basin. These genetic resources increase the possibility of olive breeding in a new scenario of adaptation to climate change. This possibility is especially interesting for the study of some agronomic characters related to biotic and abiotic stresses. Specifically and as an example, while there are no cultivated olive varieties that resist the wilt caused by

Verticillium dahliae, some authors have studied the existence of wild germplasm capable of tolerating the presence of this fungus without producing disease in the plant [

3,

4].

In Spain, more than 250 olive cultivars have been reported [

5,

6]. The most abundant in the olive groves of the Iberian Penisula is Picual, typical of the fields of Jaén, with more than 66 million olive trees in this province, and it is also a predominant cultivar in Southeastern Andalusia and part of the Centre of Spain. Arbequina cultivar is one of the most abundant in Northeastern Spain, which, in recent years, has been widely used, together with Arbosana, Sikitita1 and Sikitita2 for crops grown in hedgerows and superintensive crops. Another new cultivar is Martina, which is obtained from crosses between other cultivars. Hojiblanca and Cornicabra are very common in the Málaga and Córdoba provinces, respectively. Manzanilla de Sevilla and Cornezuelo de Jaén are widely used for table olives. Empeltre is cultivated in areas of Aragon, Navarra and Castellón. Other very common cultivars in other countries of the Mediterranean basin are Koroneiki, the most important cultivar in Greece, Frantoio, the main Italian variety, and Chemlali de Kabile, one of the most important varieties grown in Tunisia.

The improvement in the efficiency of photosynthesis for increasing crop yields is an issue of special attention between plant physiologists and breeders. In photosynthesis, there exists a balance between the energy used for photosystems II and I to obtain ATP and NADPH and the one spent to protect the photosynthetic machinery when the irradiances are very high [

7]. The quantity and quality of light and the concentration of CO

2 in the ambient have a direct effect on this process. At low irradiances, the amounts of ATP and NADPH produced during the light reactions of photosynthesis are not sufficient to synthesise the necessary carbohydrates, and therefore, plants decrease and even stop their growth. However, when the irradiances are very high, as occurs in the spring and summer of the Mediterranean Basin, another problem appears, since the plants need to use their photosystems efficiently to benefit from the abundant light that reaches them, while avoiding excess irradiance, which produces damages in the structure of the photosynthetic apparatus [

8]. Leaf anatomy and development, i.e., establishment of the polarity, xylem and phloem formation, leaf blade expansion, shape morphogenesis, and the development of mesophyll (palisade and spongy tissues), is a process with great influence on the photosynthetic efficiency of plants [

9], which, in the case of drought stress, can have a significant impact. When plants experience a lack of water, leading to water deficits in their tissues, they may close their stomata to conserve water. This closure reduces the availability of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis, limiting the rate of assimilation. The production of oxygen free radicals interacts with the biochemical cell cycles. The chlorophyll content in leaves may decrease, causing damage to the photosynthetic machinery, and thus affecting the functionality of photosystems II and I. The enzymatic activity, synthesis and structure of some proteins, such as RuBisCo and Phosphoenol pyruvate carboxylase, are affected, disrupting the overall efficiency of the photosynthetic process [

10].

New perspectives to improve photosynthetic efficiency include a better display of leaves in crop canopies, avoiding the photorespiration process, especially in C3 species, genetic engineering of carboxylase enzymes to obtain a better affinity for CO

2, and optimisation of plants to maximise carbon gain with decreases in water use [

11]. Few studies exist to date in this regard on

Olea europaea. Aranda Barranco et al., (2020) [

5,

6] studied the capacity to sequester carbon in two Spanish olive groves whose management differed in the vegetation cover of each of them. In the first case, the field did not have such plant groundcovers compared to the second olive grove, which did. The experiment was carried out for a year and concluded that weed cover is responsible for the high carbon sequestration capacity of this conservation practice in olive groves. With the policies of adaptation to climate change, a crucial objective nowadays is the achievement of negative CO

2 emissions to the atmosphere. Biotic sequestration can be a winning strategy for climate mitigation. Terrestrial ecosystems have the potential to sequester around 333 Gigatons of C by the end of this century. For this, it is necessary to implement the best management practices in agriculture, adapting olive groves to climate change in the Mediterranean basin, and their sustainability in olive oil production. The diversification of olive groves with a diverse range of cultivars can enhance resilience because of their varying tolerance to extreme temperatures, water stress, salinity and diseases. By selecting cultivars, farmers minimise the risk of crop failure, provide better natural pest control and pollination, and improve overall ecosystem health. Planting groundcovers, creating a habitat for beneficial insects, and preserving native vegetation could help support a diverse and resilient ecosystem. In addition, the modification of carbon photoassimilation in crops through genetic engineering is a promising alternative, which can improve carbon sequestration in ecosystems [

12].

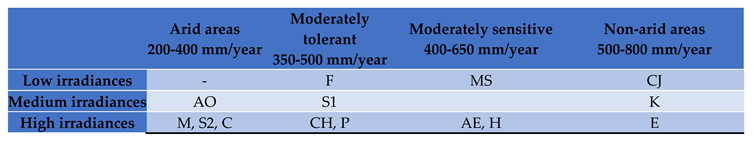

Knowing the behaviour of an olive cultivar under optimal growth and comparing it with drought stress conditions, through the response to photosynthesis using different intensities of light is a fundamental tool as a starting point for the design of any further complex experiment in the adaptation to climate change. To this end, it is important to characterise the cultivars of a species in relation to their drought tolerance and the response to the light intensity they receive. This work represents an in-depth study of the photosynthetic efficiency of 14 olive cultivars in two experimental conditions of water deficit. Surprisingly, these cultivars produce very different responses under standard irrigation and even more in moderate and severe drought conditions.

3. Photosynthesis-light response and ETR-light curves of the 14 olive cultivars

Figure 1 represents the three real curves (C, MD and SD) obtained for each cultivar and the theoretical curves that were mathematically adjusted to each of the real curves. In most cultivars, control samples present higher maximal photosynthesis (Pmax) and a higher saturation irradiance (Isat) than samples subjected to moderate drought (MD), and these, in turn, explain higher values of maximal photosynthesis and saturation irradiance than severe drought samples (SD). This behaviour confirms that plants with sufficient water availability, moderate temperature and adequate CO2 concentration have a greater capacity to photosynthesise efficiently, their stomata are open for the correct gas uptake, and chlorophylls, photosystems and chloroplast electron transport chains show good functionality.

Figure 1 indicates that, although all the cultivars studied belong to the same species, Olea europaea ssp europaea, their behaviour is very different. It can be observed that cultivars such as Chemlali (Ch), Empeltre (E) and Cornicabra (C) produce high assimilation of CO2 (above 12 µmols of CO2 m-2. s-1). Comparatively, Manzanilla de Sevilla (MS) does not exceed 2.5 µmols.m

-2.s

-1 and Hojiblanca (H) does not assimilate more than 6 µmols.m

-2.s

-1 under control conditions. It is striking that some of the cultivars photosynthesise more efficiently under MD conditions than under control conditions. This is the case of MS, Frantoio (F), Koroneiki (K) and Martina (M). Knowing the drought resistance of the olive tree, which is a typically Mediterranean species, it is not surprising that some olive cultivars may be more efficient when water availability is relatively reduced, as in the case of moderate drought conditions. This peculiarity is not directly related to drought tolerance: while K is one of the most sensitive cultivars, Martina is one of the most tolerant.

The behaviour of the cultivars follows several different patterns: there are some cultivars in which a small water deficit leads to a very sharp drop in photosynthesis. The most striking case occurs in Ch, which goes from being the most photosynthetically efficient plant under control conditions, assimilating more than 14 µmols of CO2 m-2·s-1, to producing almost no CO2 assimilation under MD and SD conditions. Although not to the extent of Chemlali, the same pattern occurs in Arbequina (A), E, F, H and Sikitita2 (S2). Other cultivars reduce their assimilation capacity sharply as the lack of water in the plant increases. This pattern of behaviour occurs in Arbosana (Ab), C, Cornezuelo de Jaén (CJ), K, M, MS, Picual (P) and Sikitita 1(S1). It should be noted that some cultivars, despite the extreme lack of water, continue to produce considerable CO2 assimilation in SD. This is the case of C, which produces a maximum photosynthesis of 6 µmols of CO2. m-2.s-1 in SD or M, which produces 4 µmols of CO2.m-2.s-1 under the same conditions. MS is the least photosynthetically efficient cultivar in control conditions, although the lack of water does not affect its assimilation capacity considerably in MD or SD.

This work measured the electron transfer rate (ETR) that occurs along the transport chain during the luminous phase of photosynthesis in the thylakoids (

Figure 2), that is, the number of electrons that pass through PSII mainly, and also through PSI, as a consequence of the excitation produced by light on photosynthetic pigments that are able to produce energy in the form of ATP and NADPH in the plant.

Under drought conditions, ETR can be affected more severily or not, depending on the cultivar’s adaptation and tolerance to water stress. Water deprivation significantly impacts photosynthesis and electron transport along PSII, resulting in a reduction of the maximum electron transport speed (Jmax). In this case, PSII is less efficient (as an adaptive strategy to prevent damage from photo-oxidation under high light intensities during drought), affecting the activity and stability of these complexes. There is a decrease in the saturation irradiance (Isat) that produces Jmax. Another consequence of water stress is a decrease in the curve slope, indicating a minor transfer of electrons with increasing light intensity and, finally, water deficit produces an increased susceptibility to photo-inhibition.

The ETR curves at different light intensities (ETR/l) were obtained for each olive cultivar (

Figure 2). Under control conditions, with ad libitum irrigation of the samples, it can be observed that most cultivars produce a maximum ETR, except for some cultivars, such as F, K and MS, in which the efficiency of electron transfer is higher under MD conditions, although under ad libitum irrigation conditions, M cultivar suffers a considerable decrease of assimilation (

Figure 1) (proof that it is a very drought-tolerant variety); however, it is curious that the ETR value under control conditions is higher than in MD. Therefore, the amount of photosynthesis this plant produces does not depend so much on an increased electron transfer along the oxidation-reduction chain, but perhaps on enzymes related to the Calvin cycle, which may not be fully functional when the amount of water the plant receives is high.

Figure 2 indicates that, in general terms, the photosystems do not seem to be affected severely by the lack of water in the plant. Even so, although this electron transition occurs in the plant in all experimental conditions, including SD conditions, it does not translate into effective photosynthesis. The minimum amount of ETR produced in SD (except for E cultivar, where electron transfer seems to be very affected), occurs in Picual, with values of 10 µmols of electrons m-2. s-1. As an example, we can see that, in the case of F, the affectation produced in the capacity of the photosystems to transfer electrons is very small, (Emax in SD >25 µmols electrons.m-2.s-1); however, the assimilation of CO2 produced by this cultivar under MD conditions and, especially, in SD, is strongly affected by the lack of water. This observation suggests, once again, that it is not the macro-complexes associated with the thylakoids (PSII, PSI, Cit b6f) structures and their electron transfer which cause this sudden decrease in photosynthesis during drought stress. It should be noted that, in C, CJ and F, electron transfer is practically unaffected by drought, with very similar response curves in the three experimental conditions. In some cultivars (CH, H, and S2), there are barely noticeable differences between both drought conditions.

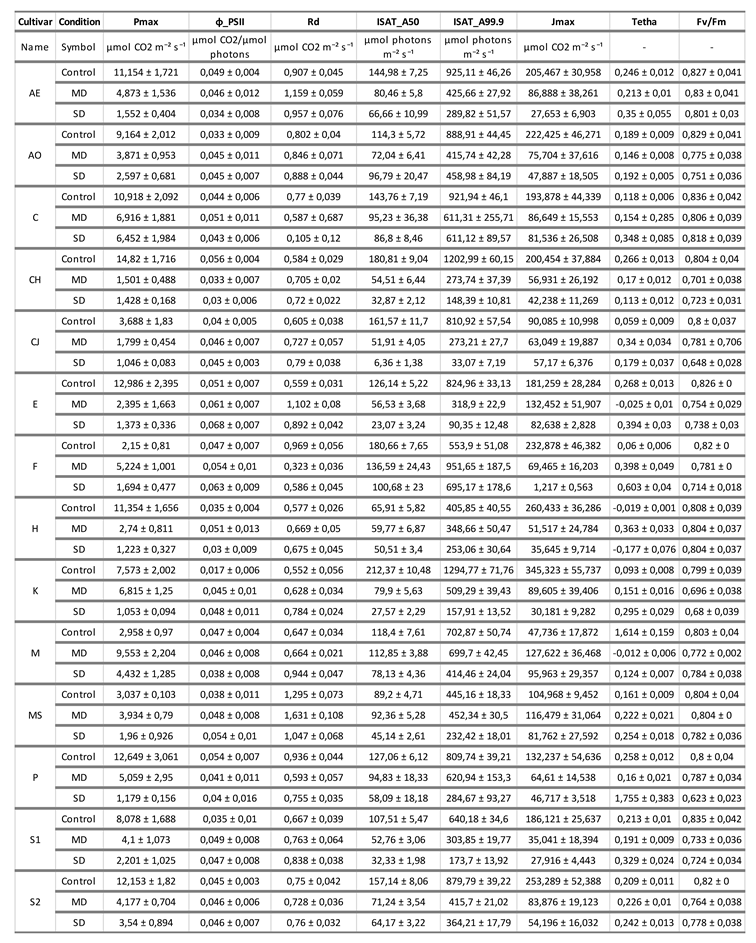

The purpose of adjusting these theoretical curves from the curves measured with the Li-Cor 6800 is to obtain and calculate parameters that will serve as indicators of the capacity of each cultivar to cope with the lack of water. These parameters are shown in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3. From the adjustment of the curves, provided that this adjustment has a correlation coefficient with a value greater than 0.95, very interesting parameters were calculated in the three experimental conditions in order to discern objectively the tolerance of each cultivar to drought.

Small discrepancies can be observed between the real values of Pmax, represented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, and the theoretical values of Pmax that these curves show after mathematical adjustment (which represents the maximum theoretical photosynthesis rate under ideal conditions provided by the ExpertCurve programme, necessary in eq 1 described in material and methods). This could be due to several reasons. Firstly, the equation being used to model the relationship between irradiance (I) and photosynthesis rate (P) may be a simplified representation of reality and may not capture all the complexities of the system. In some cases, a more complex model might be necessary to accurately describe the behaviour of photosynthesis. Secondly, the experimental data collected may have limitations or biases that affect the model’s ability to fit them. Experimental conditions, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration, temperature, humidity, and other factors, can affect the ability of photosynthesis to reach its maximum rate under ideal conditions. Thirdly, photosynthesis shows a saturation response, which means that, as the irradiance increases, the rate of photosynthesis increases until it reaches a maximum value, after which the rate of photosynthesis no longer increases. This could explain why the calculated values of Theorical_P do not reach the maximum value of “P” in the range of irradiances. Lastly, respiration in darkness (Rd) is not being considered, which eventually reduces (depending on its value) the rate of photosynthesis in the graph.

In summary, although the “Pmax” value represents the theoretical maximum rate of photosynthesis under ideal conditions, in practice, several factors can limit the ability of plants to achieve this maximum rate under all irradiance conditions. Photosynthesis is a complex process influenced by multiple variables, and it is important to consider these limitations when interpreting the results and fitting the model.

Table 1 shows that the maximum photosynthesis (Pmax) progressively decreases in general with the lack of water and, in turn, the saturation irradiances (Isat50 and Isat99.9) decrease in a positive correlation with it. This decrease is logical, since drought stress directly affects the availability of CO₂ inside the cells of the leaf as a consequence of the stomatal closure induced by ABA. The efficiency of photosystem II, ф_PSII also decreases, indicating that, with the lack of water, a greater number of photons are necessary to fix a molecule of CO

2. The maximum electron transport speed (Jmax, or the ability to assimilate CO2) decreases in all cases, becoming almost zero for cultivars like F in SD. Rd and MS present strikingly high respiration in the dark compared to the rest of the cultivars. This parameter seems to remain constant in most cultivars for all experimental conditions, except for C and F, where it decreases with drought. The same occurs with the Fv/Fm values, which remain constant or decrease slightly with water deficit in all cultivars.

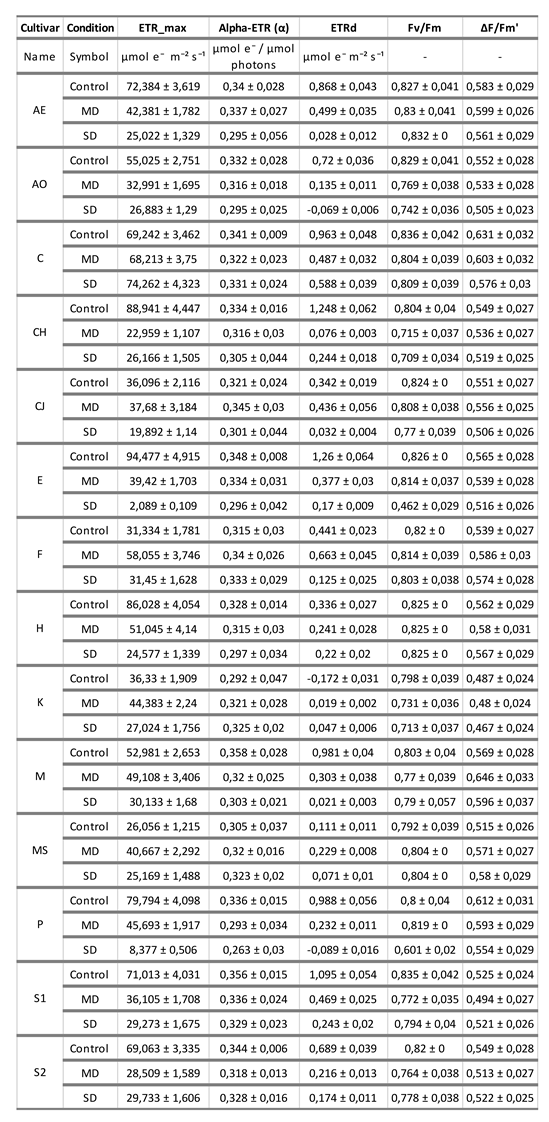

Table 2 shows the values of some parameters obtained from the fitted curves of ETR response versus irradiance (

Figure 2). Although the mathematical fit of these curves with the real curves is not as good as in the first case (photosynthesis-irradiance response), the calculation of the parameters indicated in

Table 2 were obtained from the zones of the curve in which there is a fit with a value of R> 0.95 with the real curves. ETRmax is the maximum electron transfer rate in the thylakoids during the luminous reactions. This parameter, as can be seen in

Table 2, decreases with drought, which indicates the importance of water in the light phase of photosynthesis. The plant, by not having good functionality, decreases its capacity to receive light and transform it into stable chemical energy. This occurs in all cultivars, except in F, K and MS, where the maximum radius of electron transfer occurs under MD conditions. Alpha-ETR is the slope of the curve, that is, the efficiency of photosynthesis in relation to incident light intensity (measured in micromoles electrons/micromols photons). This efficiency is quite stable with the lack of water, which indicates that a practically constant number of electrons jump in the protein complexes of the chloroplast with a photon of light, regardless of the water deficit. Of course, the result produced on the ETRmax is different, since the efficiency of transferring those electrons from one macro-complex to another is affected by the lack of water. For example, in the case of the CH cultivar, although alphaET () remains almost constant in the three experimental conditions, ETRmax goes from 88.9 under control conditions to 22.9 in MD and 26.1 in SD. The exception occurs in two cultivars, CJ and P, in which decreases with drought.

ETRd is the electron transport rate when the plant is adapted to the dark and, therefore, all the macrocomplexes inserted in the thylakoids are completely reduced. Logically, this parameter has a very low value, since the plant is in darkness and does not receive luminous energy. ISAT_ETR50 refers to the point at which the electron transport rate reaches 50% of its maximum value in response to light intensity. Therefore, ISAT_ETR75 and ISAT_ETR99.9 are the irradiances at which 75% and 99.9% of electron transfer occurs, respectively, between the protein macro complexes involved in the red-ox chain of the light phase.

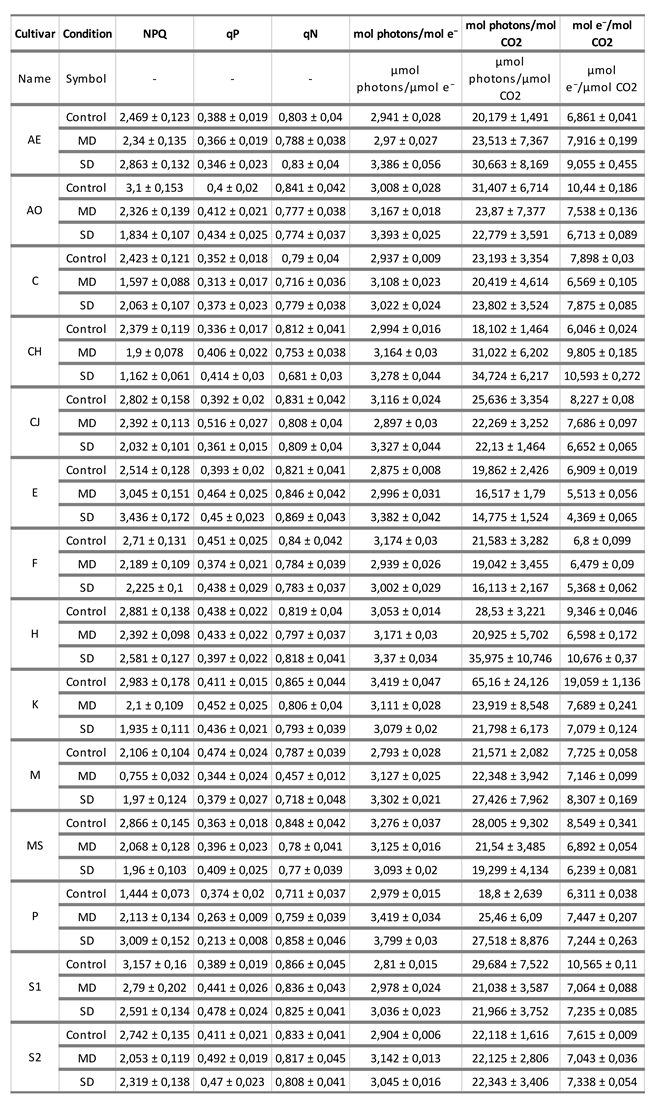

With respect to the data reflected in

Table 3, it should be noted that ΔF/Fv’ represents the photosynthetic efficiency of the plant adapted to light. The value of this parameter decreases with the lack of water in general terms. There are some exceptions, such as M, where the maximum efficiency occurs in MD conditions, and S1, where its maximum efficiency occurs in SD. Both cultivars turn out to be very drought-tolerant. Moreover, Fv/Fm is always greater than ΔF/Fm’, since the first parameter is measured when the plant is adapted to darkness, where all macrocomplexes are in a reduced state. NPQ (Non-Photochemical Quenching) is the capacity of photosystems to dissipate excess energy as heat. To this end, the amount of carotenoids that are part of the antennas of the photosystems, which are responsible for obtaining this excess energy and dissipating it into the atmosphere in the form of heat, play a fundamental role. qP (Photochemical Quenching) represents the fraction of photosystems that are in the reduced state, i.e., available for the photochemical process, that is, the fraction of light that is, at those moments, used to produce photosynthesis, and qN (Non-Photochemical Quenching) represents the fraction of reaction centres of PSII that are in an oxidised state, or the quantity of dissipated light. The amount of photons necessary to make an electron jump increases with drought; this parameter, above all, is greatly increased in SD conditions. The number of photons required to fix a CO2 molecule is slightly increased between the control samples and the samples subjected to MD. In some cultivars, even a moderate lack of water in the plant favours the CO2 fixation process.

Finally, the amount of electrons that the plant needs to transfer along the redox chain to produce the fixation of a CO2 molecule is also increased with the lack of water.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant material:

Fourteen olive cultivars were used as plant material: Arbequina (A) Arbosana (Ab), chemlali (Ch) Cornicabra (C) Cornezuelo de Jaén (CJ), Empeltre (E), Frantoio (F), Hojiblanca (H), Koroneiki (K), Manzanilla de Sevilla (MS), Martina (M), Picual (P), Sikitita1 (S1) and Sikitita2 (S2). These are predominant cultivars in the olive groves of the Mediterranean Basin, and they are used in the three culture systems of current olive groves: classical, intensive and super-intensive production systems. There were 12 samples per cultivar of one year of age, from a height of one meter approximately, all of them certified by the World Olive Germplasm Bank of Córdoba (WOGBC). The cultivars used were Arbequina, Arbosana, Chemlali, Cornezuelo de Jaén, Cornicabra, Empeltre, Frantoio, Hojiblanca, Koroneiki, Manzanilla de Sevilla, Martina, Picual, Sikitita1 and Sikitita2. The experiment was carried out in a growth chamber Aralab, 12000 PHL-LED, with irrigation ad libitum for six “control” samples and the following controlled parameters: photoperiod light/dark 16h/8h; light intensity 1600 µmol m-2 s-1; temperature 21 °C; 400ppm CO2 concentration in the chamber; and relative air humidity of 50%. The other six samples of each cultivar were used in the drought stress experiment. In this case, the plants stopped being watered for a minimum of 28 days in the case of the most sensitive cultivars and a maximum of 42 days for the most tolerant to water stress.

4.2. Curve fitting

In order to obtain a full overview of photosynthetic performance in the different cultivars considered, we used different approaches for the fitting of the experimental data. Thus, firstly, we fitted the data using the equation described by [

15] (Eq. 1), a hyperbolic tangent model:

where P is the net assimilation rate (mol CO

2 m

-2 s

-1), Pmax is the maximum rate of net photosynthesis (mol CO

2 m

-2 s

-1), tanh is the hyperbolic tangent function, I is the incident irradiance (mol photon m

-2 s

-1),

is the initial slope of net photosynthesis versus irradiance (mol CO

2 mol photon

-1), and R

d is the respiration rate in darkness (mol CO

2 m

-2 s

-1).

In order to determine saturating irradiance (Isat), i.e., irradiance at which net assimilation rate was saturated, the assimilation rate versus irradiance data was also fitted according to the equation described by [

16]

where Pmax is the maximum net assimilation rate (mol CO

2 m

-2 s

-1), n is the fraction of Pmax for which I

sat(n) is calculated (dimensionless, [0 ≤ n ≤ 100]), I

sat(n) is the irradiance at which the n fraction of Pmax is produced (mol photon m

-2 s

-1), R

d is the respiration rate in darkness (mol CO

2 m

-2 s

-1) and

is the initial slope of net photosynthesis versus irradiance (mol CO

2 mol photon

-1). Thus, this equation allowed us to calculate I

sat(100), I

sat(75) and I

sat(50), the irradiances at which 100% (typically known as saturating irradiance), 75% and 50% of Pmax were achieved, respectively.

ElectronTransfer Rate was calculated through the following equation:

where ETR is the electron transport rate (mol e

- m

-2 s

-1), AQ is the absorbed quanta (mol photon m

-2 s

-1), calculated as the product of incident quanta by absorptance, which is considered to be 0.5, and AF/Fm’ is the effective quantum yield of PS II.

The equation proposed by [

15] was also used to fit the data from the fluorescence vs irradiance curves (Eq. 2, modified from Eq. 1):

where ETR is the electron transport rate (see Eq. 3, defined in the above equation) (mol e

- m

-2 s

-1), ETRmax is the maximum electron transport rate (mol e

- m

-2 s

-1), tanh is the hyperbolic tangent function, I is the incident irradiance (mol photon m

-2 s

-1),

is the initial slope of ETR vs irradiance (mol e

- mol photon

-1) and ETR

d is the electron transport rate in darkness (mol e

- m

-2 s

-1).

Additionally, experimental data of net photosynthesis versus irradiance were fitted using equation 5 described by [

17]:

where P is the net assimilation rate (mol CO

2 m

-2 s

-1), I is the incident irradiance (mol photon m

-2 s

-1), J

max is the maximum rate of electron transport (mol e

- m

-2 s

-1) needed to supply energy for carboxylation and reduction reactions, which are subsequently catalysed by RuBisCO in the C assimilation stage (Calvin-Benson cycle), and

is the curvature factor (convexity (dimensionless), [0 <

< 1]).

Finally, several parameters were calculated from those obtained from the curve fitting.

4.3. Photosynthesis and fluorescence versus light response curves

All gas exchange and fluorescence measurements were recorded on fully expanded adult leaves in plants from each cultivar. The photosynthesis response (net photosynthetic rate, P, mol CO2 m-2 s-1) to different irradiance (mol photon m-2 s-1) was measured on 5 leaves (either control or moderate and severe drought samples), using a LI-6800 Portable Photosynthesis System with a transparent leaf chamber. The chamber was installed in a direction vertically upward to the soil surface using a level so as to not affect the other leaves. The LI-6800 was equipped with a 6800-01 fluorometer, to determine fluorescence parameters. Here is a brief explanation of each parameter: Fv/Fm is an estimate of the maximum quantum efficiency of PSII reaction centers. This ratio is calculated from two parameters: Fo and Fm. Fo is the fluorescence level of a dark-adapted plant with all PSII primary acceptors ‘open’ (QA fully oxidised). Fm is the maximal fluorescence level achieved upon application of a saturating flash of light, such that all primary acceptors ‘close’ Quinone QA fully reduced. Variable fluorescence, Fv, is the difference between Fo and Fm. Pmax (also known as Psat or PN, mol CO2 m-2 s-1) refers to the maximum rate of net CO2 assimilation per unit leaf area. It represents the highest achievable photosynthesis rate of a leaf under optimal conditions, such as high radiation, suitable temperature, and no limitations from other factors. Rd (also known as Rdark or R, mol CO2 m-2 s-1) is the rate of dark respiration. It denotes the amount of CO2 released by plant respiration in the absence of light. Rd is a constant rate and is a crucial component in calculating the net photosynthesis rate under illuminated conditions. Photoynthetic efficiency, alpha (α, mol CO2 mol photon-1), represents the photosynthetic efficiency. It indicates the plant’s ability to convert absorbed radiation into photosynthesis. Alpha corresponds to the initial slope (linear response) of the photosynthesis response curve concerning radiation. Theta (θ, dimensionless) is the curvature of the curve response in the transition from the linear part to the saturation part, i.e., the rate at which photosynthesis saturates at high irradiances. This parameter is linked to photoinhibition, which is the reduction in photosynthesis rate at high light intensities. Jmax (mol e- m-2 s-1) stands for the light-saturated potential maximum rate of electron transport through photosystem II (PSII) measured from the evolution of CO2 assimilation. It represents the plant’s utmost capacity to utilise light in the photosynthesis process and is a critical limiting factor for photosynthesis at high light intensities.

These parameters are crucial for understanding and modelling plant responses to light and photosynthesis under diverse environmental conditions. Their estimation and comprehension are fundamental for studies in plant physiology and ecology, and they have practical applications in areas such as agronomy and conservation biology.

Before recording the photosynthetic and fluorescence measurements, five randomly selected plants were adapted to darkness overnight. Then, saturated pulsed light (3000 μmol m

−2 s

−1, 300 ms duration) was applied to determine maximum quantum yield efficiency (Fv/Fm), according to equation 6 [

18]:

where F

v is the variable fluorescence (dimensionless), F

m is the darkened maximum fluorescence (dimensionless), and F

o is the darkened minimum fluorescence (dimensionless). This measurement allowed adjusting parameters in the fluorometer system to properly acquire fluorescence signal.

Light response data were gathered using the “Autolog-Light response” auto-programme in the LI-6800. Full light response curves on trees from each olive cultivar and control/drought treatments were measured using 10 different incident irradiance levels (2000, 1500, 1000, 750, 500, 400, 200, 100, 50, 0 µmol photon m-2 s-1). All the plants in each combination were selected randomly. During the measurements, the following parameters were controlled: CO2 concentration at 400 ppm, relative humidity at 40%, ambient temperature at 21°C, airflow at 500 mmol s-1, and fan speed at 10000 rpm. The auto-programmes were set to run for 60 to 180 s at a given light level before moving to the next light level in the auto-programme. The responses of the 14 cultivars to photosynthesis subjected to drought stress and in the control treatment were measured once a week in triplicate to obtain nine response curves to light for the analysis of the moderate drought interval (7, 14 and 21 days post irrigation) and nine curves for the analysis of the severe drought interval (curves taken at 21, 28 and 35 days post irrigation) vs the control plants.

In each light response curve, the following parameters were estimated from the gas exchange: P, net assimilation rate (mol m-2 s-1), gsw, stomatal conductance to water vapour (mol H2O m-2 s-1), E, transpiration rate (mol H2O m-2 s-).

Using the fluorometer during the light response curves the following parameters were also determined: Fv/Fm, maximum quantum yield efficiency (as defined above, dimensionless, determined in darkness), F/Fm’, effective quantum yield efficiency in the light-adapted plant (dimensionless, defined as in equation), qP, photochemical quenching (dimensionless, defined as in Eq. 7), and qN, non-photochemical quenching (dimensionless, defined as in Eq. 7).

F

m’ is the maximum fluorescence emission under steady-state illumination (dimensionless, analogous to F

m), and Fs is the minimum fluorescence emission under steady-state illumination (dimensionless, analogous to F

o).

where Fo’ is the minimum fluorescence emission in a light-adapted sample after a brief dark period, and F

m’ and F

s as described above.

with all the parameters as described above.

Although values of E, F/Fm’, qP and qN were determined in each curve for all the incident irradiances, only those measured at the saturating irradiance (Isat(100)) were considered.

Finally, electron transport rate curves (ETR) were considered. ETR was calculated according to Eq. 10:

where ETR is the electron transport rate (mol e

- m

-2 s

-1), AQ is the absorbed quanta (mol photon m

-2 s

-1), calculated as the product of incident quanta by absorptance, FII is the fraction of AQ directed to Photosystem II and AF/Fm’ is the effective quantum yield of PS II. Absorptance was not measured but considered to be 0.84, the average ratio of light absorbed by leaves in higher plants, and FII was considered to be 0.5, as the average ratio of PSII to PSI reaction centres [

19].

4.4. Statistical analyses

Once all the study parameters, both those from non-linear fitting models and those from the analysis with the LI-COR 6800 system, were collected, an analysis of distribution and homogeneity of variances was performed as a function of the fixed factors: experimental condition and cultivar type. The study of normality and homogeneity of variances was based on the p-value result obtained from the Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene test, respectively. For p-values > 0.05 in both tests, it is considered that the data approximate a normal and homogeneous distribution.

For those parameters that showed a normal distribution and homogeneity in their variances, a parametric analysis was conducted, in this case, a factorial analysis of variance, to identify if there was interaction between the fixed factor “condition” and the fixed factor “cultivar” for each study parameter. Parameters showing positive interactions underwent a subsequent post hoc analysis to identify significant changes between experimental conditions for the same cultivar or between cultivars for a specific experimental condition.

For parameters that followed a non-normal distribution or heterogeneity in their variances, multiple transformations, such as arccosine, logarithmic, exponential, inverse, etc., were performed until a normal and homogeneous distribution was achieved. In cases where data transformation was not possible, a non-parametric analysis was conducted. The Kruskal-Wallis test was chosen as a non-parametric version of one-way ANOVA, as the data came from independent samples, but the assumptions of normality or homogeneity of variances were not met.

In both analyses, only significant changes with p-value < 0.05 were considered. The Tukey test (p ≤ 0.05) was applied for comparisons between groups in parametric analyses, and the Dunn’s multiple comparison test (an extension of the Mann-Whitney test) allowed comparisons between pairs of groups after the Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric analysis).

These statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio Version: 2023.06.1+524 (requires R 3.3.0+, 2023 Posit Software, PBC formerly RStudio, PBC) along with the statistical software Statgraphics Centurion 19 Version 19.1.3 (Statgraphics Technologies, Inc. 1982-2020).