Submitted:

01 October 2023

Posted:

02 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

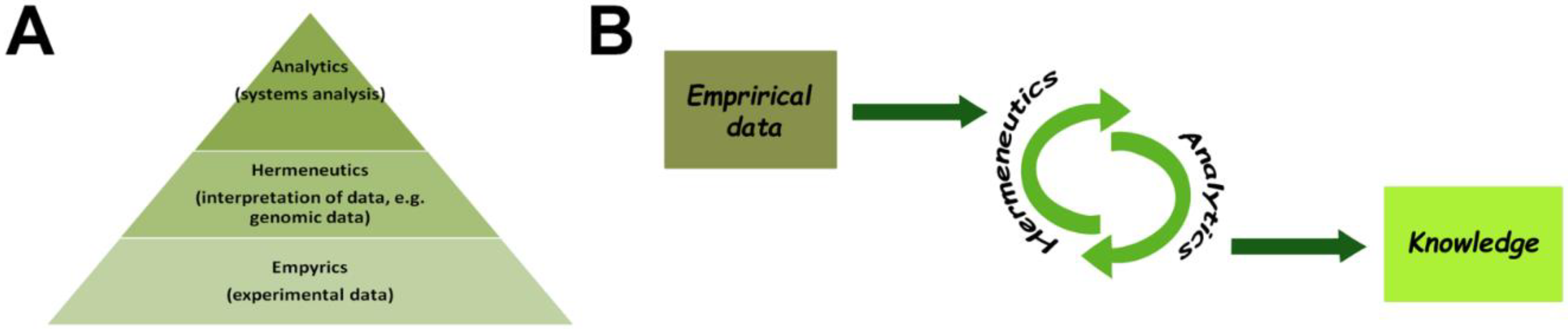

2. Theory

3. Practice

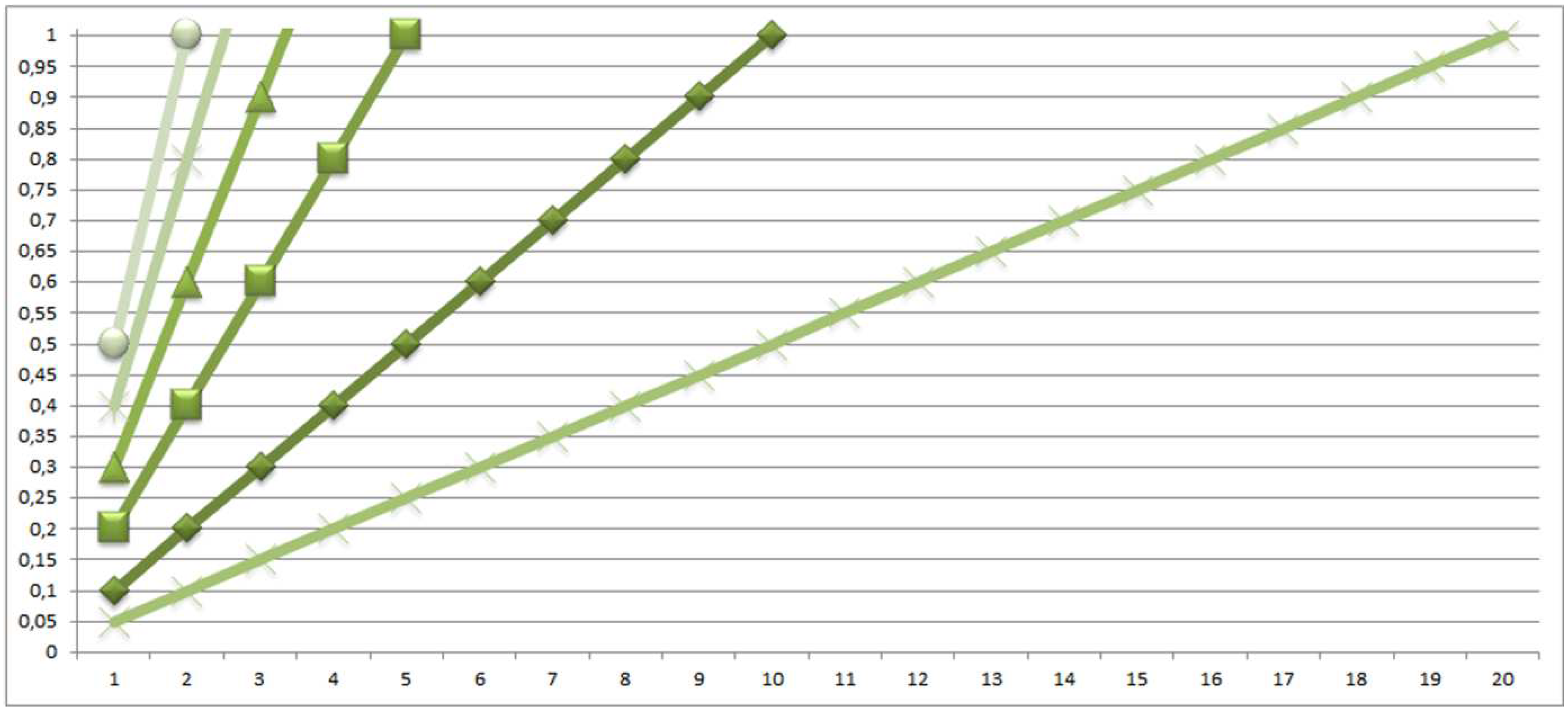

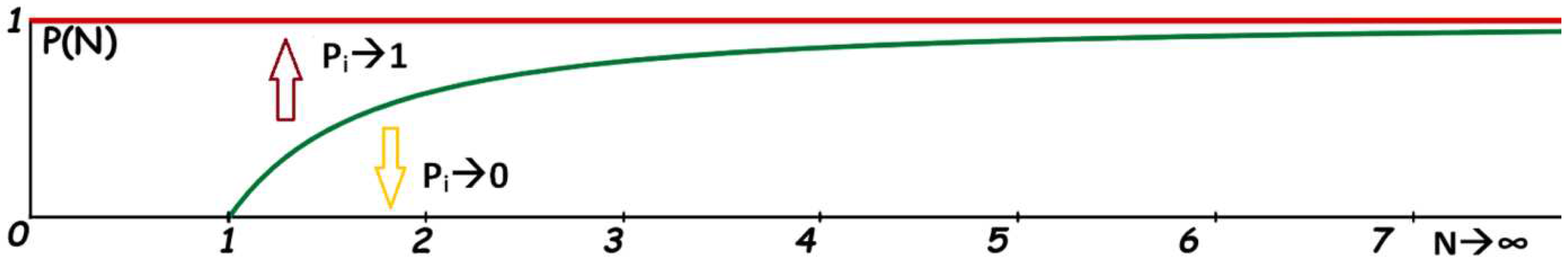

4. Methodology

4.1. Optimistic Scenario

4.2. Realistic Scenario

5. Conclusion

References

- Dougherty ER. On the epistemological crisis in genomics. Curr Genomics. 2008; 9(2):69-79. doi: 10.2174/138920208784139546. [CrossRef]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47(D1):D330-D338. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1055. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG. Chromosome-centric look at the genome. In: Iourov I, Vorsanova S, Yurov Y, editors. Human interphase chromosomes — Biomedical aspects. Springer; 2020. pp. 157–170.

- Liehr T. From human cytogenetics to human chromosomics. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20(4):826. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040826. [CrossRef]

- Liehr T. About classical molecular genetics, cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic data not considered by Genome Reference Consortium and thus not included in genome browsers like UCSC, Ensembl or NCBI. Mol Cytogenet. 2021; 14(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13039-021-00540-7. [CrossRef]

- Riggs ER, Ledbetter DH, Martin CL. Genomic variation: lessons learned from whole-genome CNV analysis. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2014; 2(3):146-150. doi: 10.1007/s40142-014-0048-4. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. The variome concept: focus on CNVariome. Mol Cytogenet. 2019; 12:52. doi: 10.1186/s13039-019-0467-8. [CrossRef]

- Wainschtein P, Jain D, Zheng Z; TOPMed Anthropometry Working Group; NHLBI Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) Consortium; Cupples LA, Shadyab AH, McKnight B, Shoemaker BM, Mitchell BD, Psaty BM, Kooperberg C, Liu CT, Albert CM, Roden D, Chasman DI, Darbar D, Lloyd-Jones DM, Arnett DK, Regan EA, Boerwinkle E, Rotter JI, O’Connell JR, Yanek LR, de Andrade M, Allison MA, McDonald MN, Chung MK, Fornage M, Chami N, Smith NL, Ellinor PT, Vasan RS, Mathias RA, Loos RJF, Rich SS, Lubitz SA, Heckbert SR, Redline S, Guo X, Chen Y-I, Laurie CA, Hernandez RD, McGarvey ST, Goddard ME, Laurie CC, North KE, Lange LA, Weir BS, Yengo L, Yang J, Visscher PM. Assessing the contribution of rare variants to complex trait heritability from whole-genome sequence data. Nat Genet. 2022; 54(3):263-273. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00997-7. [CrossRef]

- Claussnitzer M, Cho JH, Collins R, Cox NJ, Dermitzakis ET, Hurles ME, Kathiresan S, Kenny EE, Lindgren CM, MacArthur DG, North KN, Plon SE, Rehm HL, Risch N, Rotimi CN, Shendure J, Soranzo N, McCarthy MI. A brief history of human disease genetics. Nature. 2020; 577(7789):179-189. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1879-7. [CrossRef]

- Burn J, Watson M. The Human Variome Project. Hum Mutat. 2016; 37(6):505-7. doi: 10.1002/humu.22986. [CrossRef]

- Manzoni C, Kia DA, Vandrovcova J, Hardy J, Wood NW, Lewis PA, Ferrari R. Genome, transcriptome and proteome: the rise of omics data and their integration in biomedical sciences. Brief Bioinform. 2018; 19(2):286-302. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw114. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Pathway-based classification of genetic diseases. Mol Cytogenet. 2019; 12:4. doi: 10.1186/s13039-019-0418-4. [CrossRef]

- Mullin AP, Gokhale A, Moreno-De-Luca A, Sanyal S, Waddington JL, Faundez V. Neurodevelopmental disorders: mechanisms and boundary definitions from genomes, interactomes and proteomes. Transl Psychiatry. 2013; 3(12):e329.

- Cardoso AR, Lopes-Marques M, Silva RM, Serrano C, Amorim A, Prata MJ, Azevedo L. Essential genetic findings in neurodevelopmental disorders. Hum Genomics. 2019; 13(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s40246-019-0216-4. [CrossRef]

- Zelenova MA, Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG, Iourov IY. Laundering CNV data for candidate process prioritization in brain disorders. Mol Cytogenet. 2019; 12:54. doi: 10.1186/s13039-019-0468-7. [CrossRef]

- Safizadeh Shabestari SA, Nassir N, Sopariwala S, Karimov I, Tambi R, Zehra B, Kosaji N, Akter H, Berdiev BK, Uddin M. Overlapping pathogenic de novo CNVs in neurodevelopmental disorders and congenital anomalies impacting constraint genes regulating early development. Hum Genet. 2023; 142(8):1201-1213. doi: 10.1007/s00439-022-02482-5. [CrossRef]

- Lupski JR. Brain copy number variants and neuropsychiatric traits. Biol Psychiatry. 2012; 72(8):617-9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.007. [CrossRef]

- Takumi T, Tamada K. CNV biology in neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2018; 48:183-192. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.12.004. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Zelenova MA, Kurinnaia OS, Vasin KS, Kutsev SI. The cytogenomic "theory of everything": chromohelkosis may underlie chromosomal instability and mosaicism in disease and aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21(21):8328. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218328. [CrossRef]

- Kopal J, Kumar K, Saltoun K, Modenato C, Moreau CA, Martin-Brevet S, Huguet G, Jean-Louis M, Martin CO, Saci Z, Younis N, Tamer P, Douard E, Maillard AM, Rodriguez-Herreros B, Pain A, Richetin S, Kushan L, Silva AI, van den Bree MBM, Linden DEJ, Owen MJ, Hall J, Lippé S, Draganski B, Sønderby IE, Andreassen OA, Glahn DC, Thompson PM, Bearden CE, Jacquemont S, Bzdok D. Rare CNVs and phenome-wide profiling highlight brain structural divergence and phenotypical convergence. Nat Hum Behav. 2023; 7(6):1001-1017. doi: 10.1038/s41562-023-01541-9. [CrossRef]

- Dougherty ER, Shmulevich I. On the limitations of biological knowledge. Curr Genomics. 2012; 13(7):574-87. doi: 10.2174/138920212803251445. [CrossRef]

- Mehta T, Tanik M, Allison DB. Towards sound epistemological foundations of statistical methods for high-dimensional biology. Nat Genet. 2004; 36(9):943-7. doi: 10.1038/ng1422. [CrossRef]

- Karczewski KJ, Snyder MP. Integrative omics for health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2018; 19(5):299-310. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2018.4. [CrossRef]

- Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Iourov IY. Neurogenomic pathway of autism spectrum disorders: linking germline and somatic mutations to genetic-environmental interactions. Curr Bioinform. 2017;12:19–26. doi: 10.2174/1574893611666160606164849. [CrossRef]

- Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG, Iourov IY. Network-based classification of molecular cytogenetic data. Curr Bioinform. 2017;12:27–33. doi: 10.2174/1574893611666160606165119. [CrossRef]

- Dekeuwer C. Conceptualization of genetic disease. In: Schramme T, Edwards S, editors. Handbook of the philosophy of medicine. Dordrecht: Springer; 2015. pp. 1–18.

- Hochstein E. Why one model is never enough: a defense of explanatory holism. Biol Philos. 2017;32(6):1105–1125.

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Systems cytogenomics: are we ready yet? Curr Genomics. 2021; 22(2):75-78. doi: 10.2174/1389202922666210219112419. [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal SB, Wright SN, Liu S, Churas C, Chilin-Fuentes D, Chen CH, Fisch KM, Pratt D, Kreisberg JF, Ideker T. Mapping the common gene networks that underlie related diseases. Nat Protoc. 2023; 18(6):1745-1759. doi: 10.1038/s41596-022-00797-1. [CrossRef]

- Ricœur P. Le conflit des interprétation. Essais d’herméneutique 1. Paris: Le Seuil. 1969.

- Mohr JW, Wagner-Pacifici R, Breiger RL. Towards a computational hermeneutics. Big Data Soc. 2015; 2(2):2053951715613809.

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, Young T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018; 18(1):148. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7. [CrossRef]

- Miah SJ, Gammack J, Hasan N. Methodologies for designing healthcare analytics solutions: a literature analysis. Health Informatics J. 2020; 26(4):2300-2314. doi: 10.1177/1460458219895386. [CrossRef]

- Burgun A, Bodenreider O. Accessing and integrating data and knowledge for biomedical research. Yearb Med Inform. 2008:91-101.

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. In silico molecular cytogenetics: a bioinformatic approach to prioritization of candidate genes and copy number variations for basic and clinical genome research. Mol Cytogenet. 2014; 7(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13039-014-0098-z. [CrossRef]

- Heng H.H. New data collection priority: focusing on genome-based bioinformation. Res Results Biomed. 2020;6(1):5–8. doi: 10.18413/2658-6533-2020-6-1-0-1. [CrossRef]

- Heng J, Heng HH. Karyotype coding: The creation and maintenance of system information for complexity and biodiversity. Biosystems. 2021; 208:104476. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2021.104476. [CrossRef]

- Stringer C. The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016; 371(1698):20150237. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. [CrossRef]

- Auffray C, Chen Z, Hood L. Systems medicine: the future of medical genomics and healthcare. Genome Med. 2009; 1(1):2. doi: 10.1186/gm2. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson M, Nestor CE, Zhang H, Barabási AL, Baranzini S, Brunak S, Chung KF, Federoff HJ, Gavin AC, Meehan RR, Picotti P, Pujana MÀ, Rajewsky N, Smith KG, Sterk PJ, Villoslada P, Benson M. Modules, networks and systems medicine for understanding disease and aiding diagnosis. Genome Med. 2014; 6(10):82. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0082-6. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka H, Kreisberg JF, Ideker T. Genetic dissection of complex traits using hierarchical biological knowledge. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021; 17(9):e1009373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009373. [CrossRef]

- Barabási DL, Bianconi G, Bullmore E, Burgess M, Chung S, Eliassi-Rad T, George D, Kovács IA, Makse H, Nichols TE, Papadimitriou C, Sporns O, Stachenfeld K, Toroczkai Z, Towlson EK, Zador AM, Zeng H, Barabási AL, Bernard A, Buzsáki G. Neuroscience needs network science. J Neurosci. 2023; 43(34):5989-5995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1014-23.2023. [CrossRef]

- Gates AJ, Gysi DM, Kellis M, Barabási AL. A wealth of discovery built on the Human Genome Project - by the numbers. Nature. 2021; 590(7845):212-215. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00314-6. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Single cell genomics of the brain: focus on neuronal diversity and neuropsychiatric diseases. Curr Genomics. 2012; 13(6):477-88. doi: 10.2174/138920212802510439. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Korostelev SA, Zelenova MA, Yurov YB. Long contiguous stretches of homozygosity spanning shortly the imprinted loci are associated with intellectual disability, autism and/or epilepsy. Mol Cytogenet. 2015; 8:77. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0182-z. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Kurinnaia OS, Zelenova MA, Vasin KS, Demidova IA, Kolotii AD, Kravets VS, Iuditskaia ME, Iakushev NS, Soloviev IV, Yurov YB. Molecular cytogenetic and cytopostgenomic analysis of the human genome. Res Results Biomed. 2022; 8(4):412–423. doi: 10.18413/2658-6533-2022-8-4-0-1. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Iafrate AJ, Brothman AR. Copy number variations and clinical cytogenetic diagnosis of constitutional disorders. Nat Genet. 2007; 39(7 Suppl):S48-54. doi: 10.1038/ng2092. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY. Cytopostgenomics: what is it and how does it work? Curr Genomics. 2019; 20(2):77–78. doi: 10.2174/138920292002190422120524. [CrossRef]

- Liehr T. Cytogenomics. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2021.

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Somatic cell genomics of brain disorders: a new opportunity to clarify genetic-environmental interactions. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2013; 139(3):181–188. doi: 10.1159/000347053. [CrossRef]

- Ye CJ, Sharpe Z, Heng HH. Origins and consequences of chromosomal instability: from cellular adaptation to genome chaos-mediated system survival. Genes (Basel) 2020; 11(10):1162. doi: 10.3390/genes11101162. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG, Kutsev SI. Chromosome instability, aging and brain diseases. Cells. 2021; 10(5):1256. doi: 10.3390/cells10051256. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Kutsev SI. Ontogenetic and pathogenetic views on somatic chromosomal mosaicism. Genes (Basel). 2019; 10(5):379. doi: 10.3390/genes10050379. [CrossRef]

- Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Iourov IY. Dynamic nature of somatic chromosomal mosaicism, genetic-environmental interactions and therapeutic opportunities in disease and aging. Mol Cytogenet. 2020; 13:16. doi: 10.1186/s13039-020-00488-0. [CrossRef]

- Costantino I, Nicodemus J, Chun J. Genomic mosaicism formed by somatic variation in the aging and diseased brain. Genes (Basel) 2021; 12(7):1071. doi: 10.3390/genes12071071. [CrossRef]

- Ji Z, Song Q, Su J. Editorial: Advanced computational systems biology approaches for accelerating comprehensive research of the human brain. Front Genet. 2023; 14:1143789. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1143789. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Kurinnaia OS, Kutsev SI, Yurov YB. Somatic mosaicism in the diseased brain. Mol Cytogenet. 2022; 15(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13039-022-00624-y. [CrossRef]

- Andrade MA, Sander C. Bioinformatics: from genome data to biological knowledge. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997; 8(6):675-83. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80118-8. [CrossRef]

- Kirov G, Pocklington AJ, Holmans P, Ivanov D, Ikeda M, Ruderfer D, Moran J, Chambert K, Toncheva D, Georgieva L, Grozeva D, Fjodorova M, Wollerton R, Rees E, Nikolov I, van de Lagemaat LN, Bayés A, Fernandez E, Olason PI, Böttcher Y, Komiyama NH, Collins MO, Choudhary J, Stefansson K, Stefansson H, Grant SG, Purcell S, Sklar P, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ. De novo CNV analysis implicates specific abnormalities of postsynaptic signalling complexes in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2012; 17(2):142-53. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.154. [CrossRef]

- Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Hehir-Kwa JY, van Bon BW, Schuurs-Hoeijmakers JH, Meader S, Hellebrekers CJ, Thoonen IJ, de Brouwer AP, Brunner HG, Webber C, Pfundt R, de Leeuw N, de Vries BB. Clinical significance of de novo and inherited copy-number variation. Hum Mutat. 2013; 34(12):1679-87. doi: 10.1002/humu.22442. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Shi J, Ouyang J, Zhang R, Tao Y, Yuan D, Lv C, Wang R, Ning B, Roberts R, Tong W, Liu Z, Shi T. X-CNV: genome-wide prediction of the pathogenicity of copy number variations. Genome Med. 2021; 13(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00945-4. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Voinova VY, Yurov YB. 3p22.1p21.31 microdeletion identifies CCK as Asperger syndrome candidate gene and shows the way for therapeutic strategies in chromosome imbalances. Mol Cytogenet. 2015; 8:82. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0185-9. [CrossRef]

- Iourov IY. Cytogenomic bioinformatics: practical issues. Curr Bioinform. 2019; 14(5):372–3.

- Piñero J, Ramírez-Anguita JM, Saüch-Pitarch J, Ronzano F, Centeno E, Sanz F, Furlong LI. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48(D1):D845-D855. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1021. [CrossRef]

- Polonikov AV, Klyosova EYu, Azarova IE. Bioinformatic tools and internet resources for functional annotation of polymorphic loci detected by genome wide association studies of multifactorial diseases (review). Res Results Biomed. 2021; 7(1):15-31. DOI: 10.18413/2658-6533-2020-7-1-0-2. [CrossRef]

- Lin BC, Katneni U, Jankowska KI, Meyer D, Kimchi-Sarfaty C. In silico methods for predicting functional synonymous variants. Genome Biol. 2023; 24(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s13059-023-02966-1. [CrossRef]

- Mikhalitskaya EV, Vyalova NM, Ermakov EA, Levchuk LA, Simutkin GG, Bokhan NA, Ivanova SA. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms of cytokine genes with depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Genes (Basel). 2023; 14(7):1460. doi: 10.3390/genes14071460. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein DB, Allen A, Keebler J, Margulies EH, Petrou S, Petrovski S, Sunyaev S. Sequencing studies in human genetics: design and interpretation. Nat Rev Genet. 2013; 14(7):460-70. doi: 10.1038/nrg3455. [CrossRef]

- Ceyhan-Birsoy O, Murry JB, Machini K, Lebo MS, Yu TW, Fayer S, Genetti CA, Schwartz TS, Agrawal PB, Parad RB, Holm IA, McGuire AL, Green RC, Rehm HL, Beggs AH; BabySeq Project Team. Interpretation of genomic sequencing results in healthy and ill newborns: results from the BabySeq Project. Am J Hum Genet. 2019; 104(1):76-93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.11.016. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Yao Y, He H, Shen J. Clinical interpretation of sequence variants. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2020; 106(1):e98. doi: 10.1002/cphg.98. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).