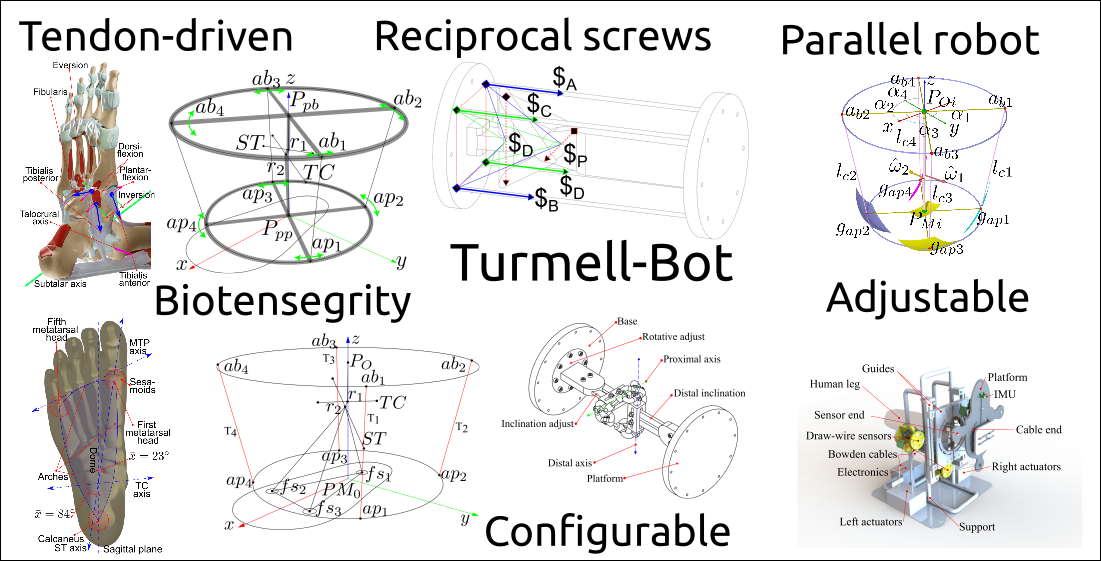

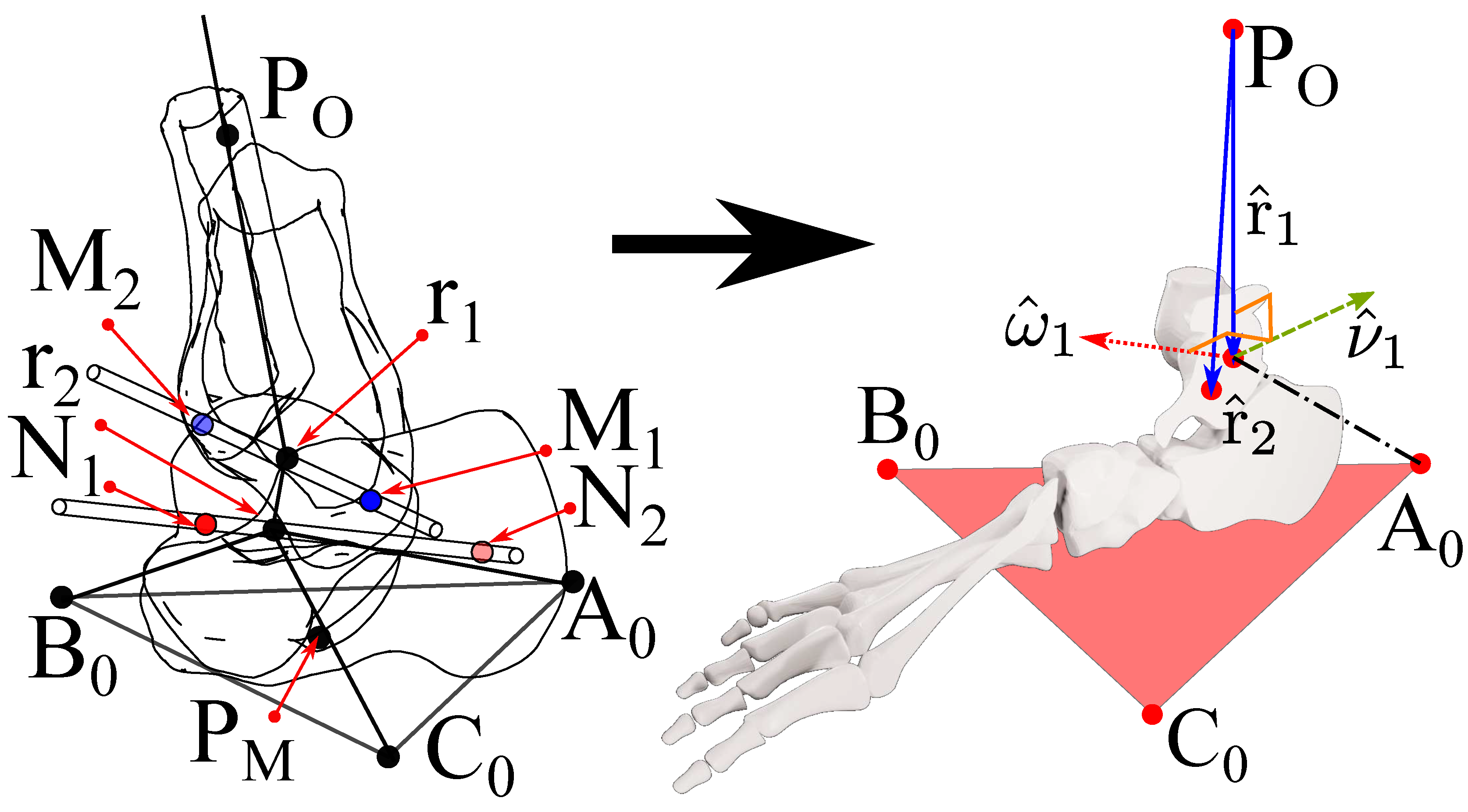

Figure 1.

Lateral top and medial bottom views of the ankle-foot anatomy. (

a) Lateral top view with components tangential to each axis. (

b) Medial bottom view with components tangential to each axis [

39].

Figure 1.

Lateral top and medial bottom views of the ankle-foot anatomy. (

a) Lateral top view with components tangential to each axis. (

b) Medial bottom view with components tangential to each axis [

39].

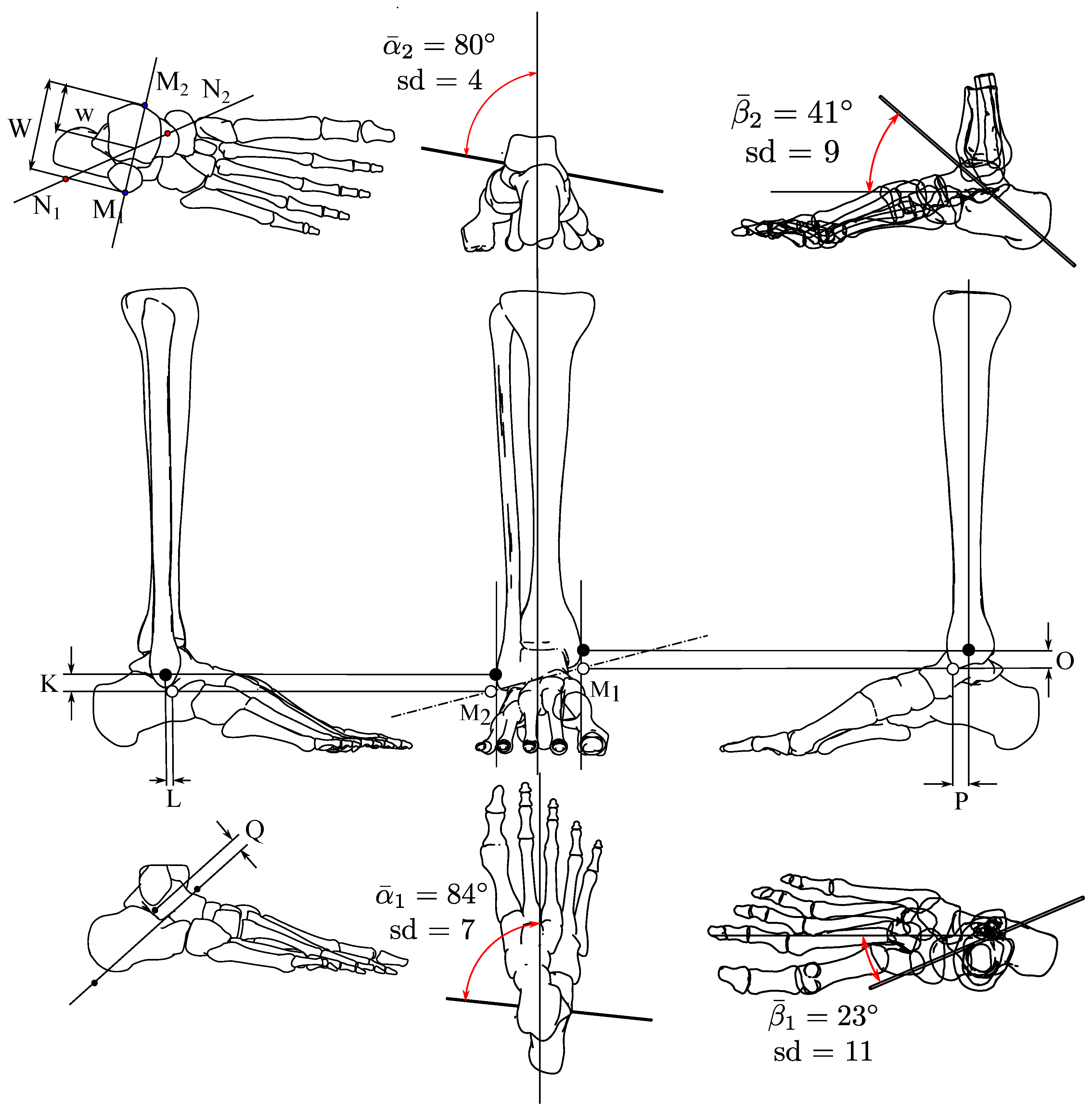

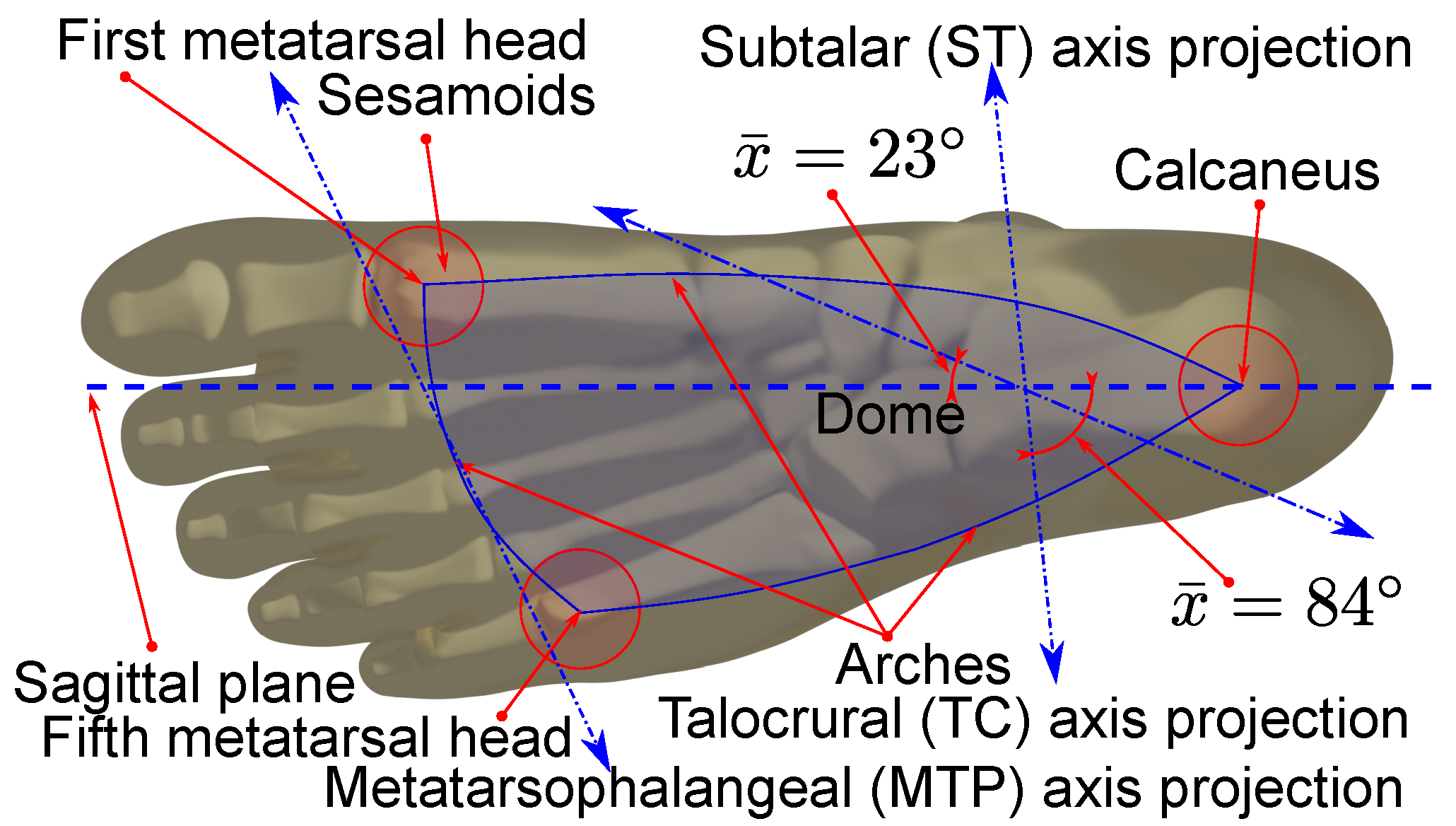

Figure 2.

Right foot’s bottom plantar plane projection with contact points and joint axis.

Figure 2.

Right foot’s bottom plantar plane projection with contact points and joint axis.

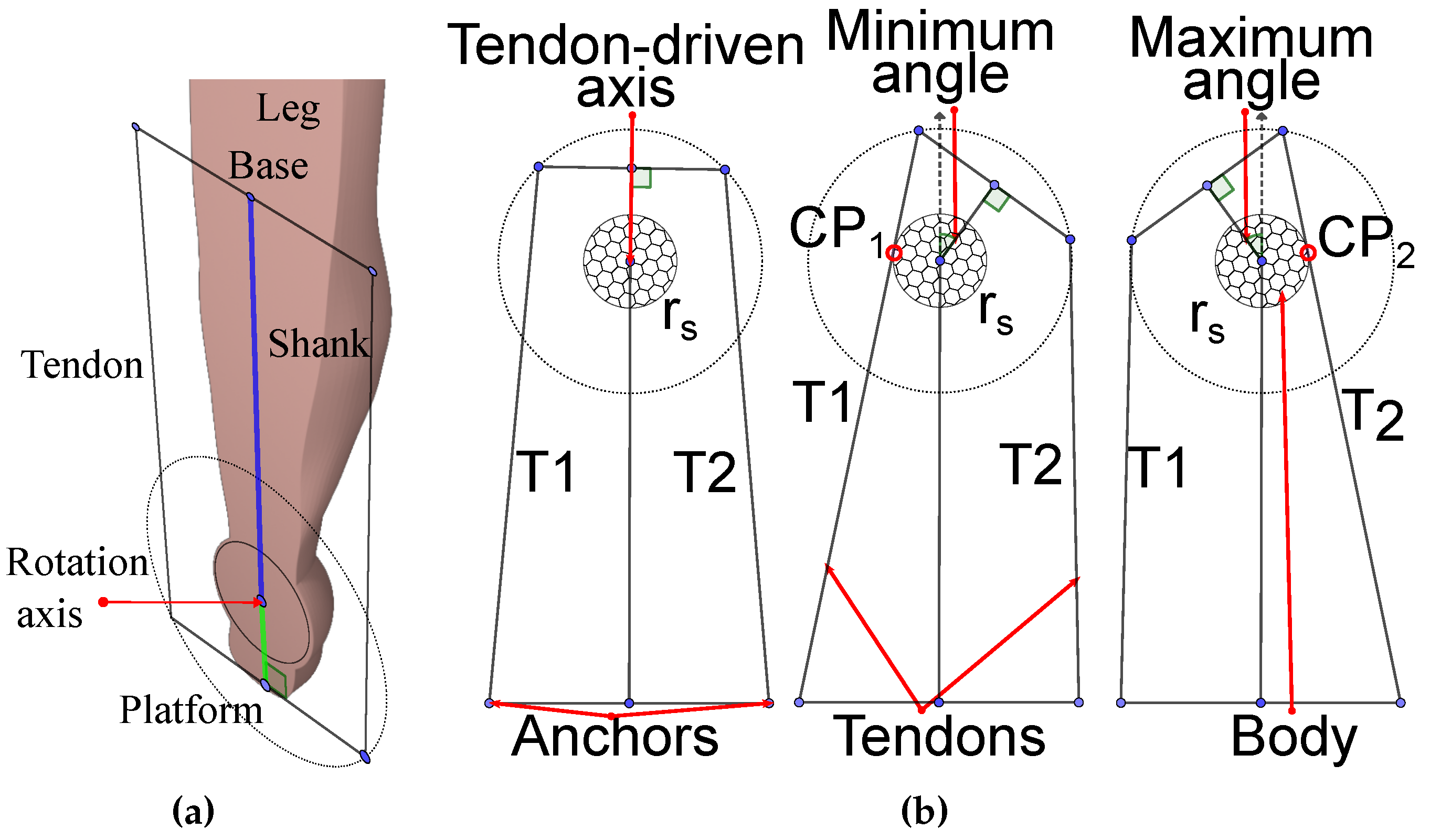

Figure 3.

Ankle model and ankle rehabilitation robot sketch. (a) Schematic representation of the approximated tendon directions in neutral position. (b) Schematic representation of reconfiguration.

Figure 3.

Ankle model and ankle rehabilitation robot sketch. (a) Schematic representation of the approximated tendon directions in neutral position. (b) Schematic representation of reconfiguration.

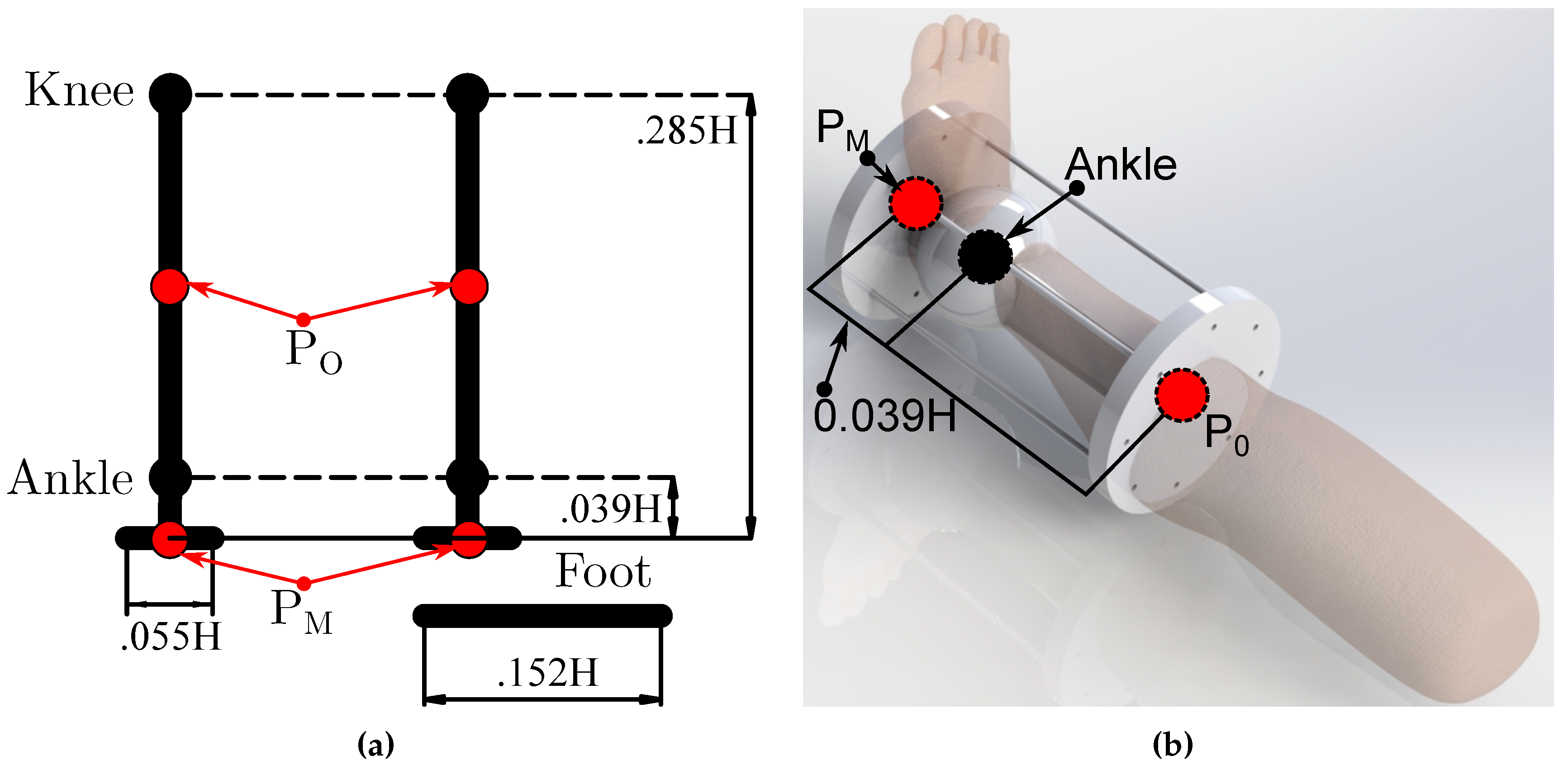

Figure 4.

Size design from proportions and statistics. (a) Proportions. (b) Three dimensional simplified design.

Figure 4.

Size design from proportions and statistics. (a) Proportions. (b) Three dimensional simplified design.

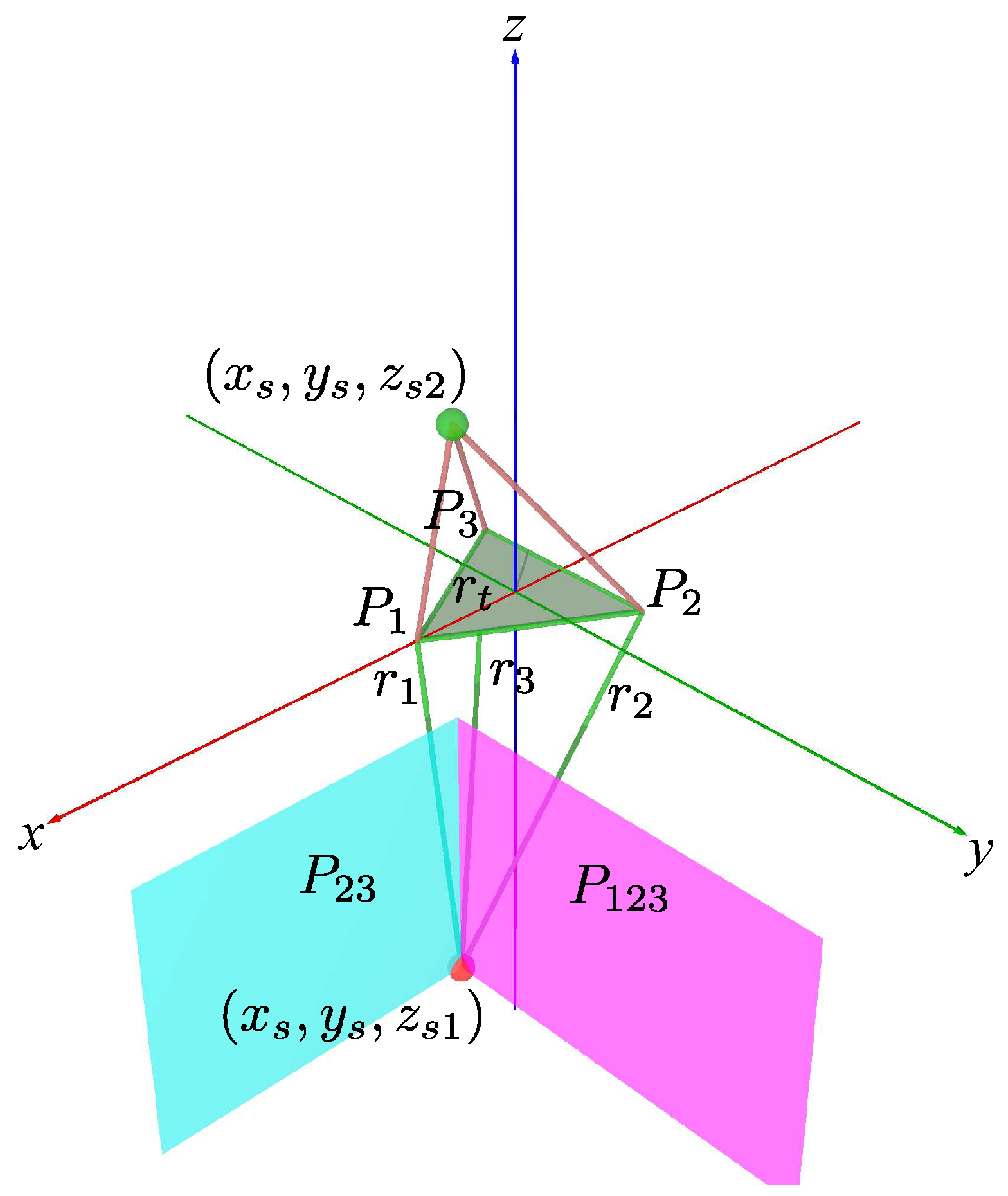

Figure 5.

Product of exponentials representation of the ankle joint [

47].

Figure 5.

Product of exponentials representation of the ankle joint [

47].

Figure 6.

Base and platform sizes initial approximation. (a) Leg coronal section. (b) Collision, range of motion, and antagonistic actuation.

Figure 6.

Base and platform sizes initial approximation. (a) Leg coronal section. (b) Collision, range of motion, and antagonistic actuation.

Figure 7.

Maximum displacement.

Figure 7.

Maximum displacement.

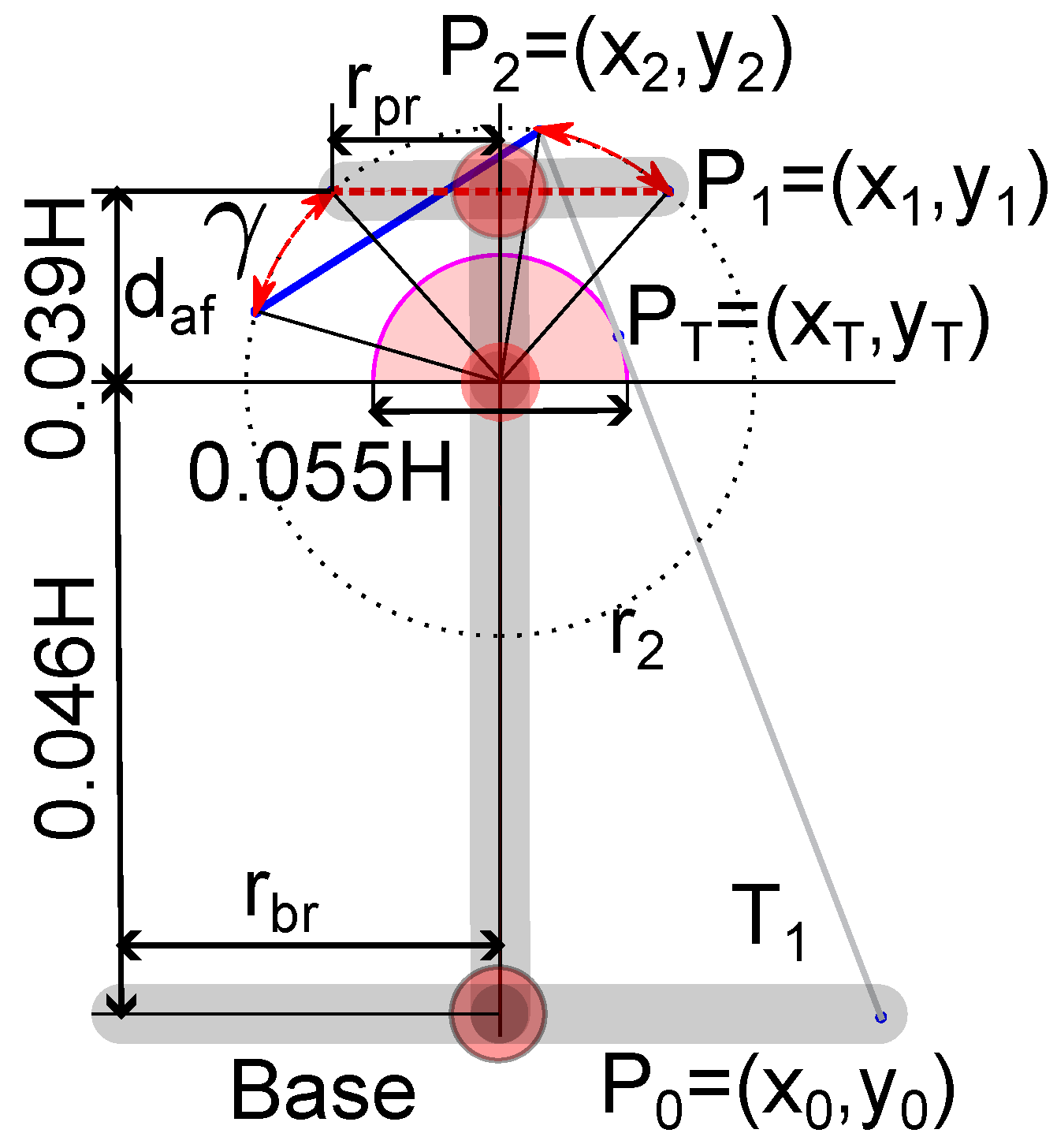

Figure 8.

Normal views of the proximal and distal axis regarding the base. (a) Normal view to the proximal axis. (b) Normal view to the distal axis.

Figure 8.

Normal views of the proximal and distal axis regarding the base. (a) Normal view to the proximal axis. (b) Normal view to the distal axis.

Figure 9.

First approximation with orthogonal axis coplanar to the tendons. (a) Antagonistic cables screws representation. (b) Screw representation for the anchor points rotated .

Figure 9.

First approximation with orthogonal axis coplanar to the tendons. (a) Antagonistic cables screws representation. (b) Screw representation for the anchor points rotated .

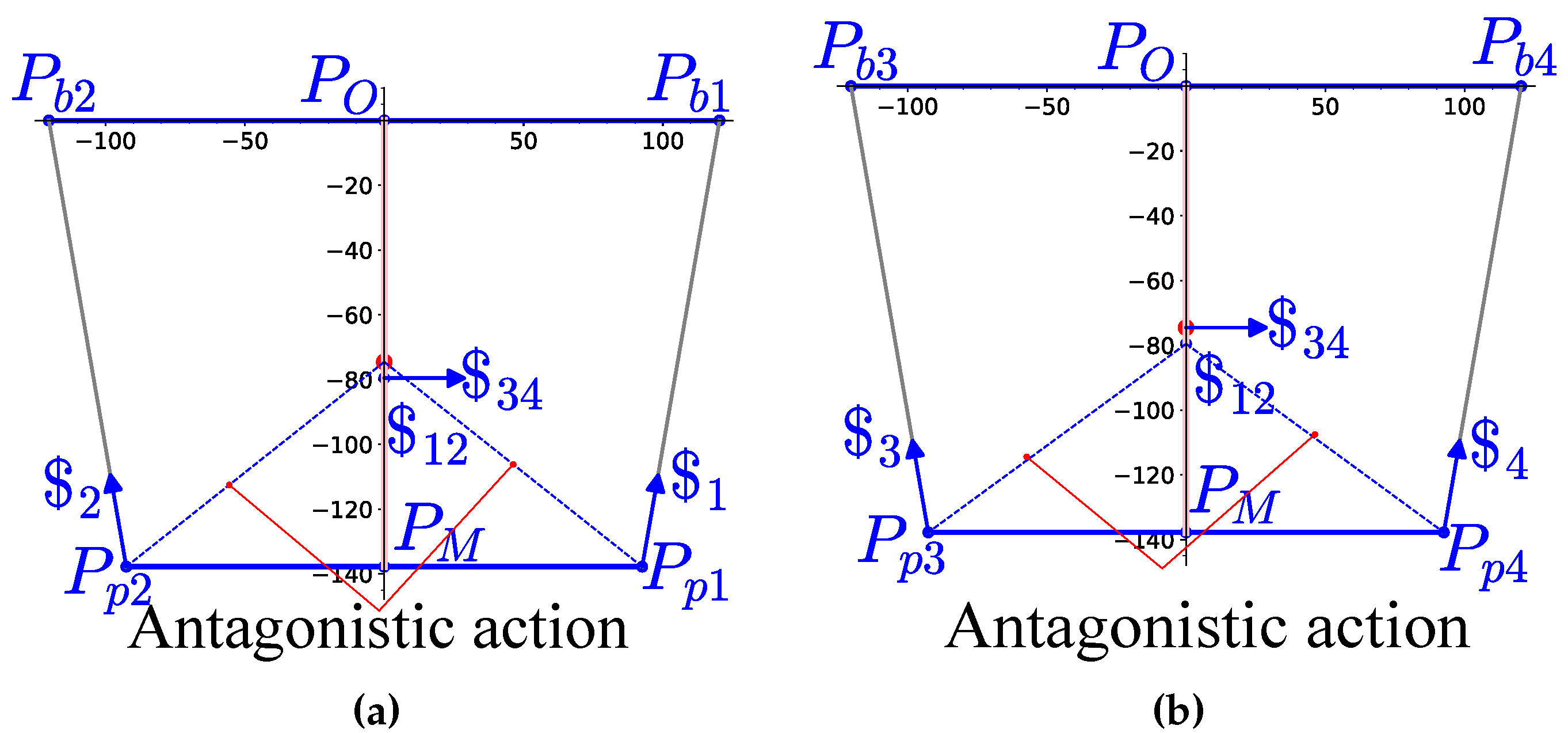

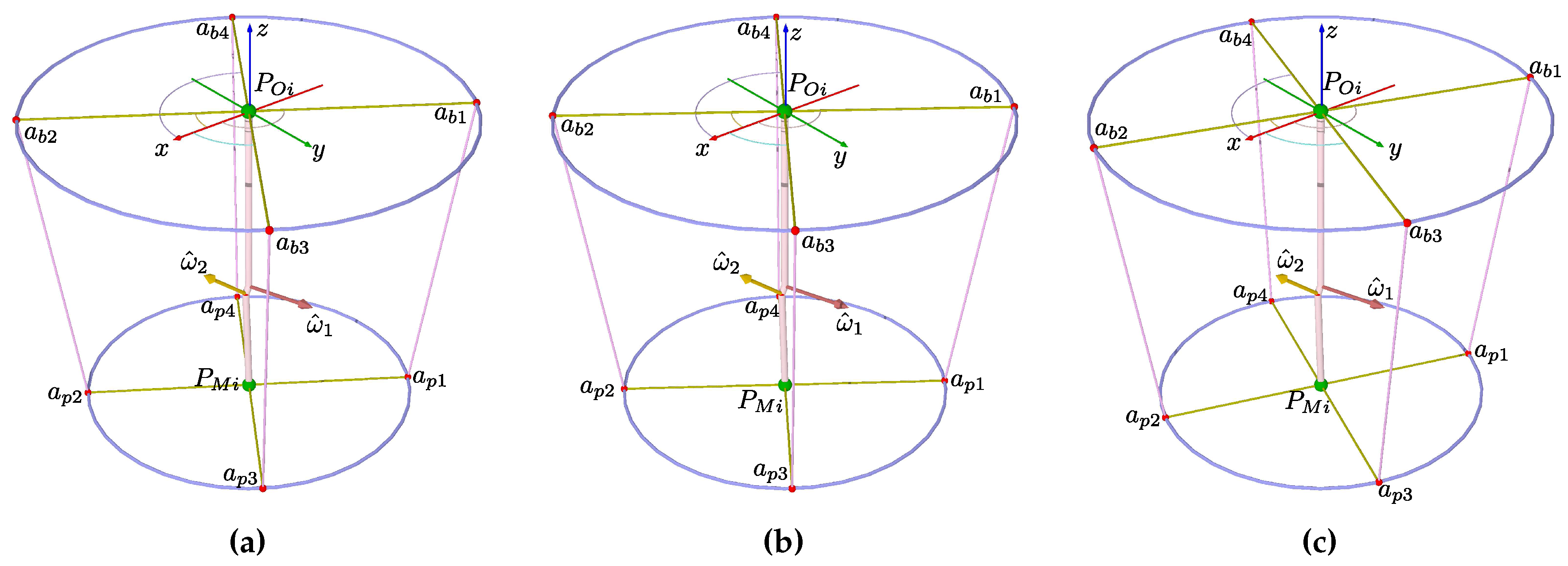

Figure 10.

Range of motion and platform-base proportions. (a) Mean height. (b) Maximum height. (c) Minimum height.

Figure 10.

Range of motion and platform-base proportions. (a) Mean height. (b) Maximum height. (c) Minimum height.

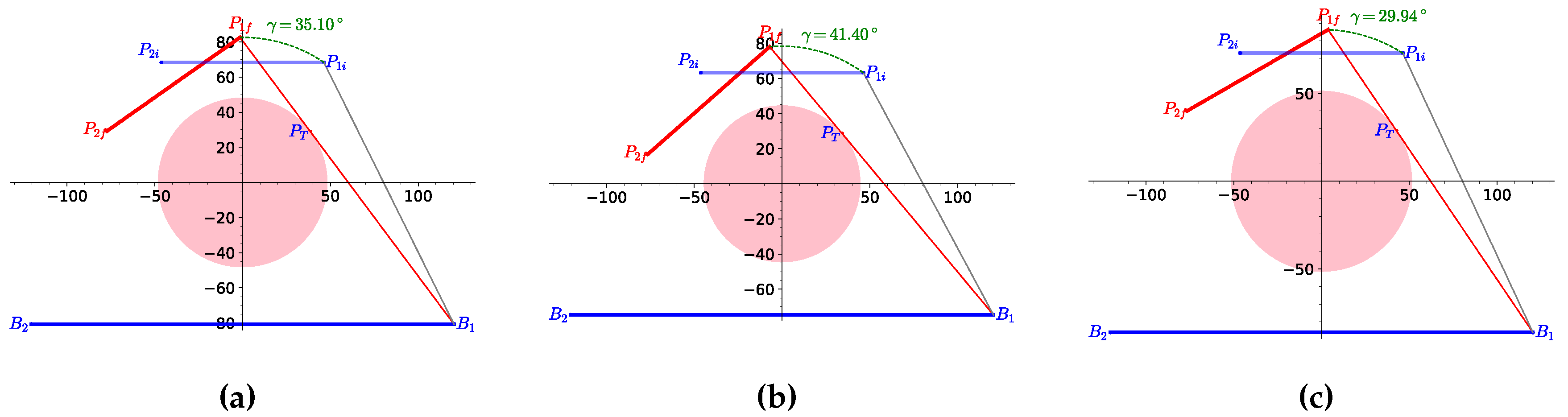

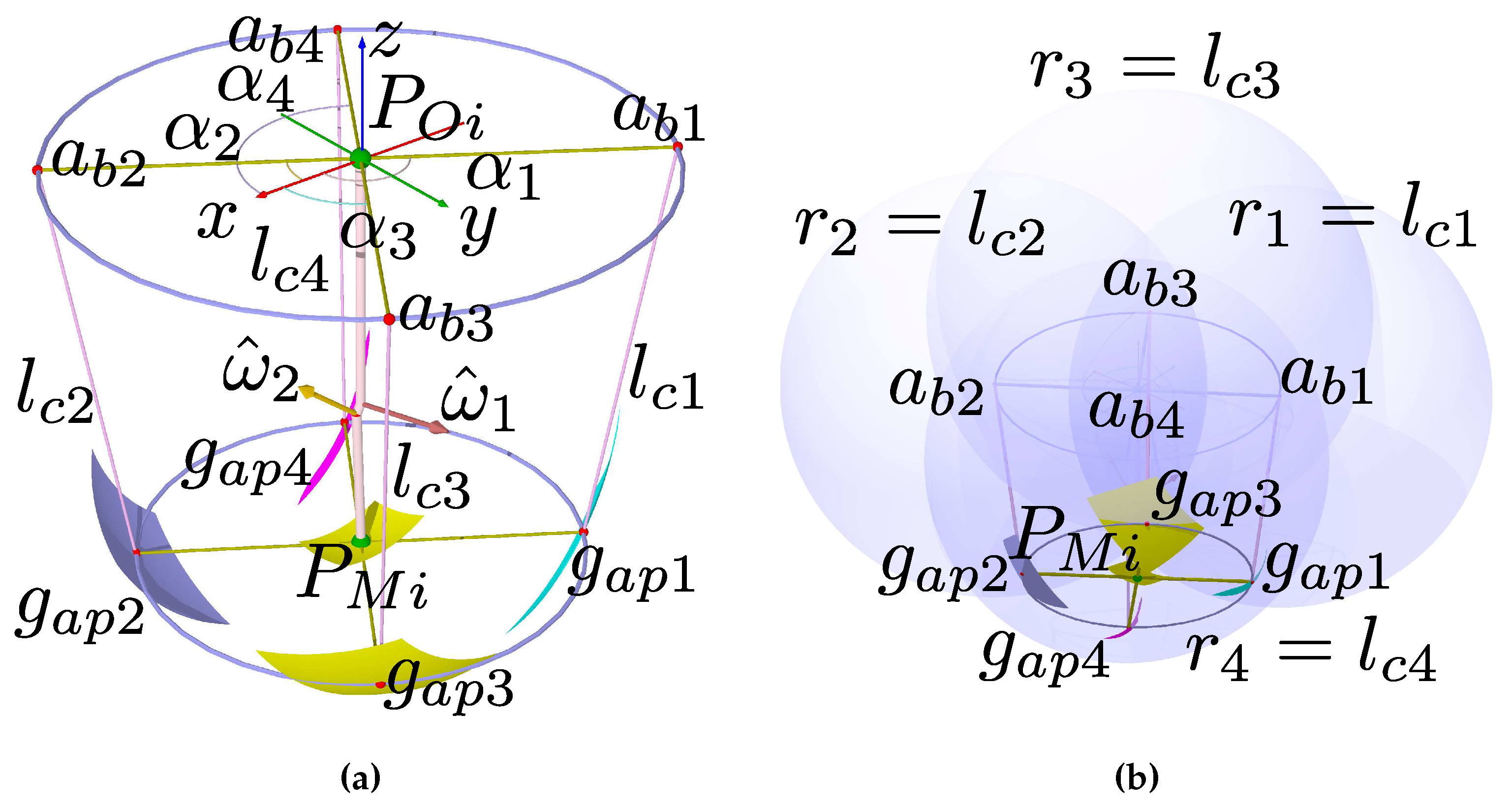

Figure 11.

Anchor points at initial position. (a) Mean statistical attitude. (b) Maximum statistical attitude. (c) Minimum statistical attitude.

Figure 11.

Anchor points at initial position. (a) Mean statistical attitude. (b) Maximum statistical attitude. (c) Minimum statistical attitude.

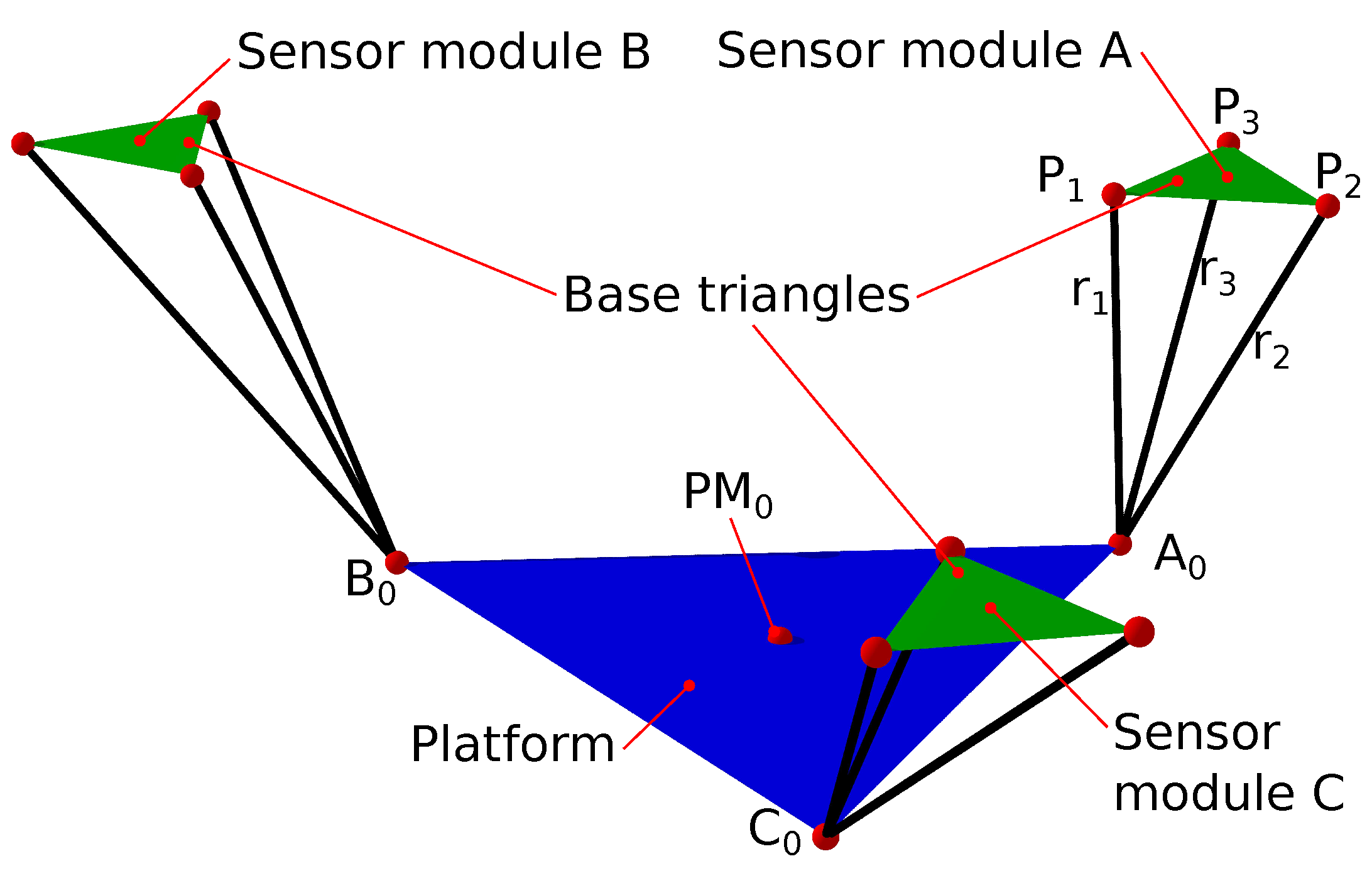

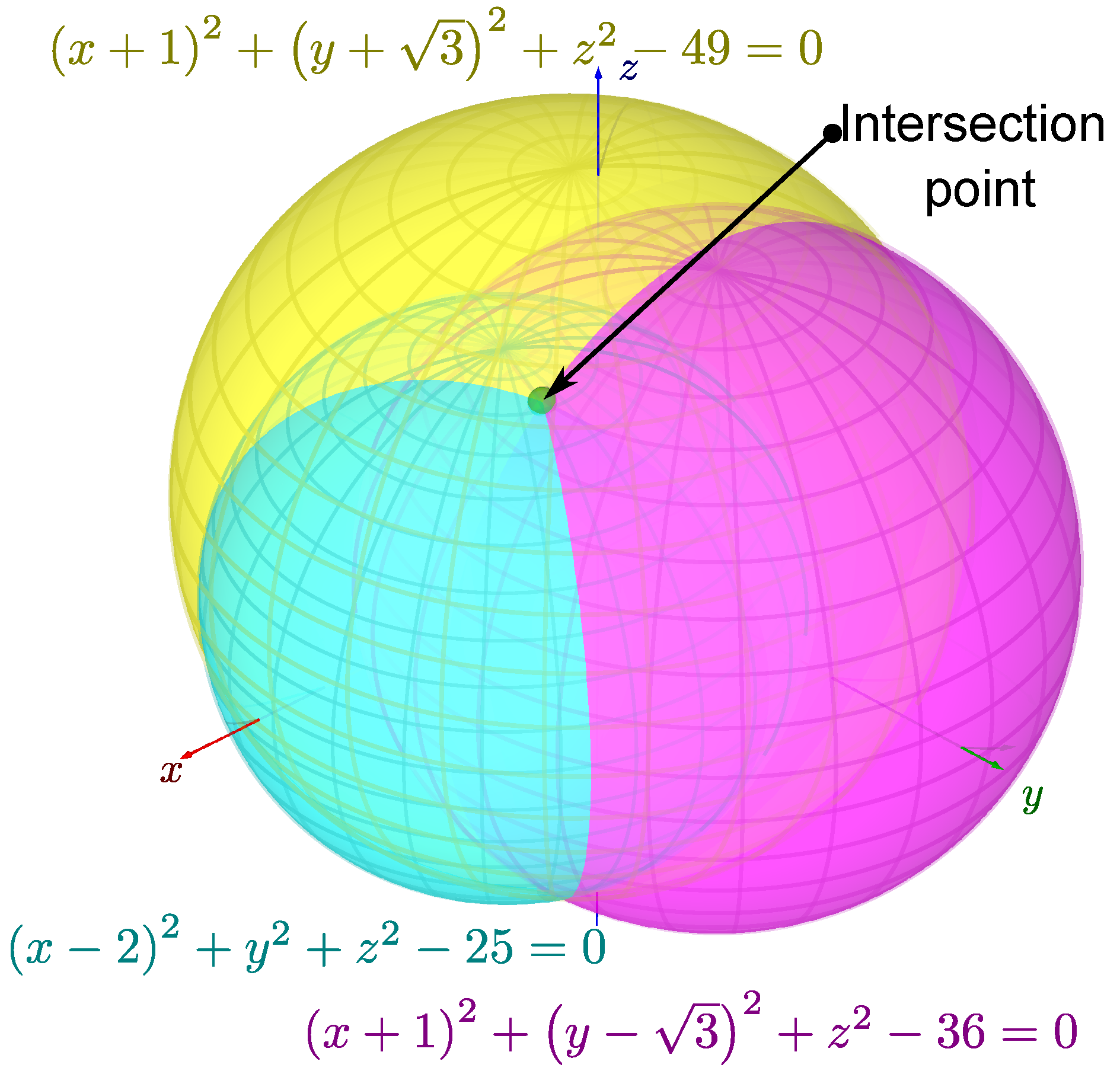

Figure 12.

Robot kinematics. (a) Centering the platform. (b)Forward kinematics.

Figure 12.

Robot kinematics. (a) Centering the platform. (b)Forward kinematics.

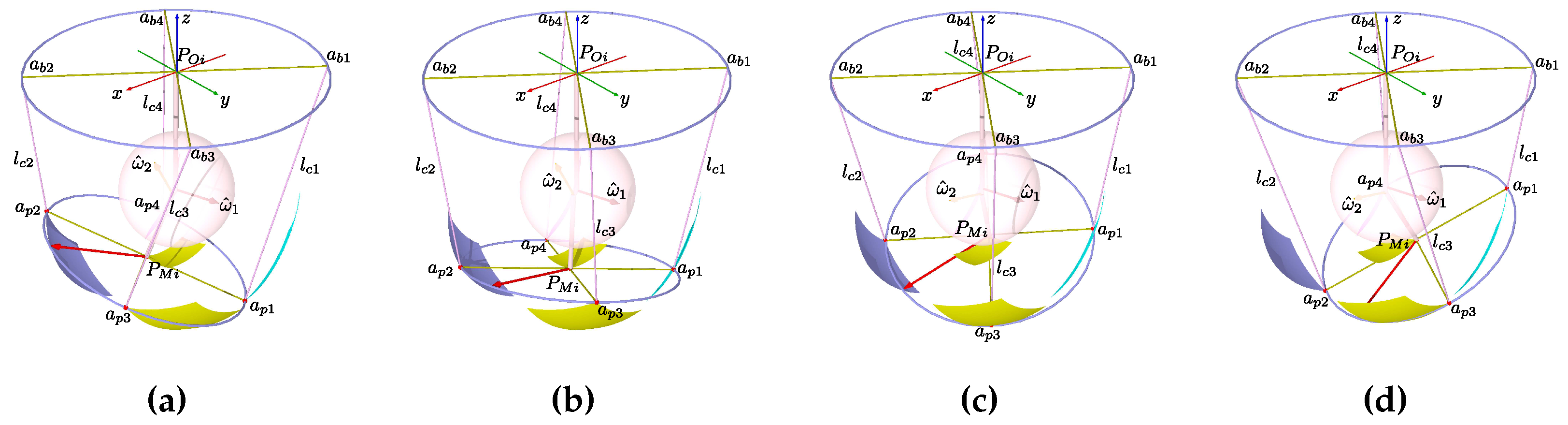

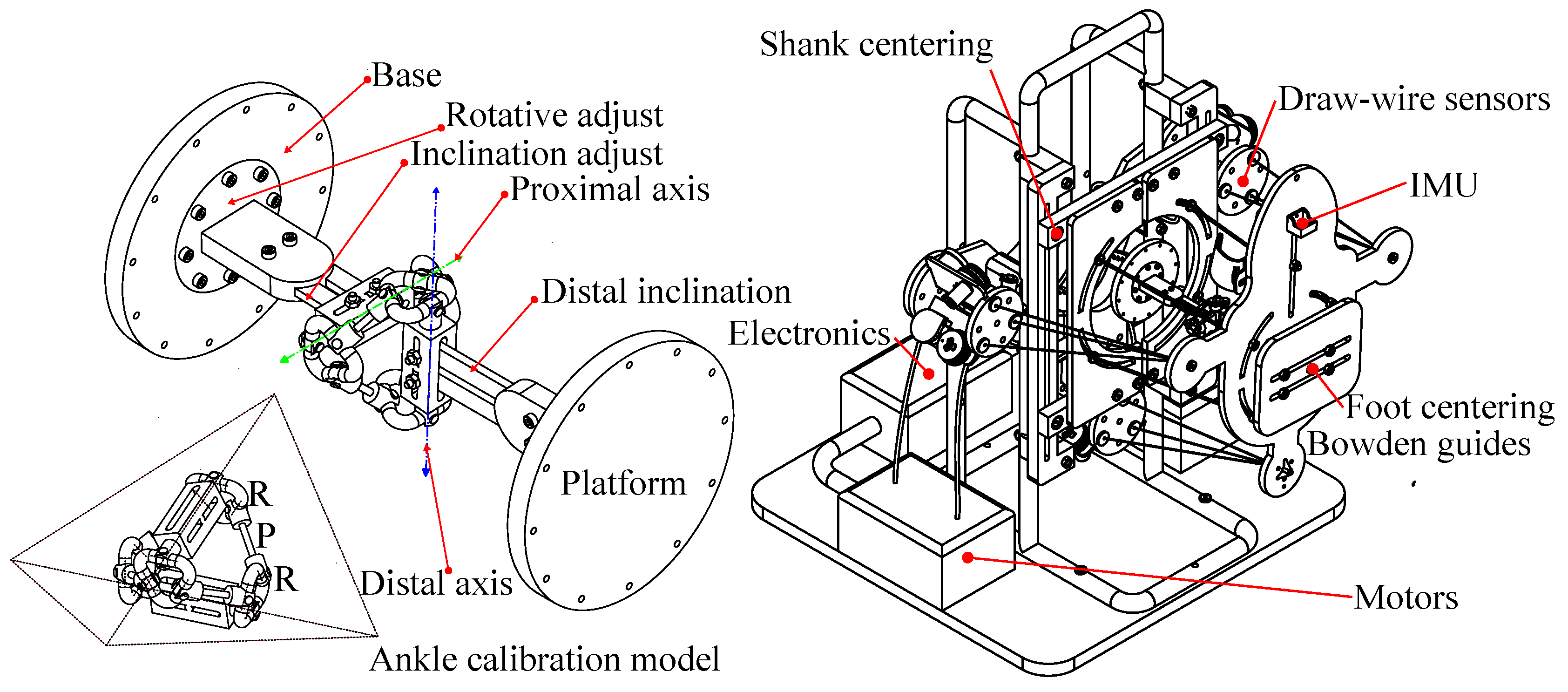

Figure 13.

Configurations for axes’ mean attitude values. a) Minimal TC and ST angles. (b)Minimal TC and ST maximal angles. c) Maximal TC and maximal ST angles. (b) TC and ST maximal angles.

Figure 13.

Configurations for axes’ mean attitude values. a) Minimal TC and ST angles. (b)Minimal TC and ST maximal angles. c) Maximal TC and maximal ST angles. (b) TC and ST maximal angles.

Figure 14.

Configurations corresponding to the axes’ maximum attitude values. a) Minimal TC and ST angles. (b)Minimal TC and ST maximal angles. c) Maximal TC and maximal ST angles. (b) TC and ST maximal angles.

Figure 14.

Configurations corresponding to the axes’ maximum attitude values. a) Minimal TC and ST angles. (b)Minimal TC and ST maximal angles. c) Maximal TC and maximal ST angles. (b) TC and ST maximal angles.

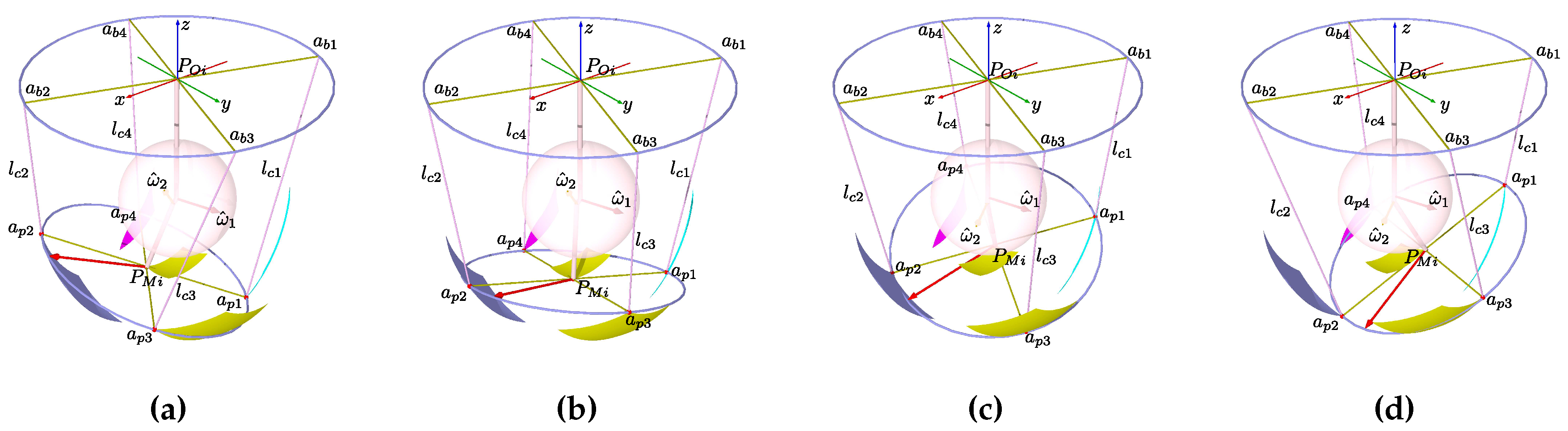

Figure 15.

Configurations for the axes’ minimum attitude values. a) Minimal TC and ST angles. (b)Minimal TC and ST maximal angles. c) Maximal TC and maximal ST angles. (b) TC and ST maximal angles.

Figure 15.

Configurations for the axes’ minimum attitude values. a) Minimal TC and ST angles. (b)Minimal TC and ST maximal angles. c) Maximal TC and maximal ST angles. (b) TC and ST maximal angles.

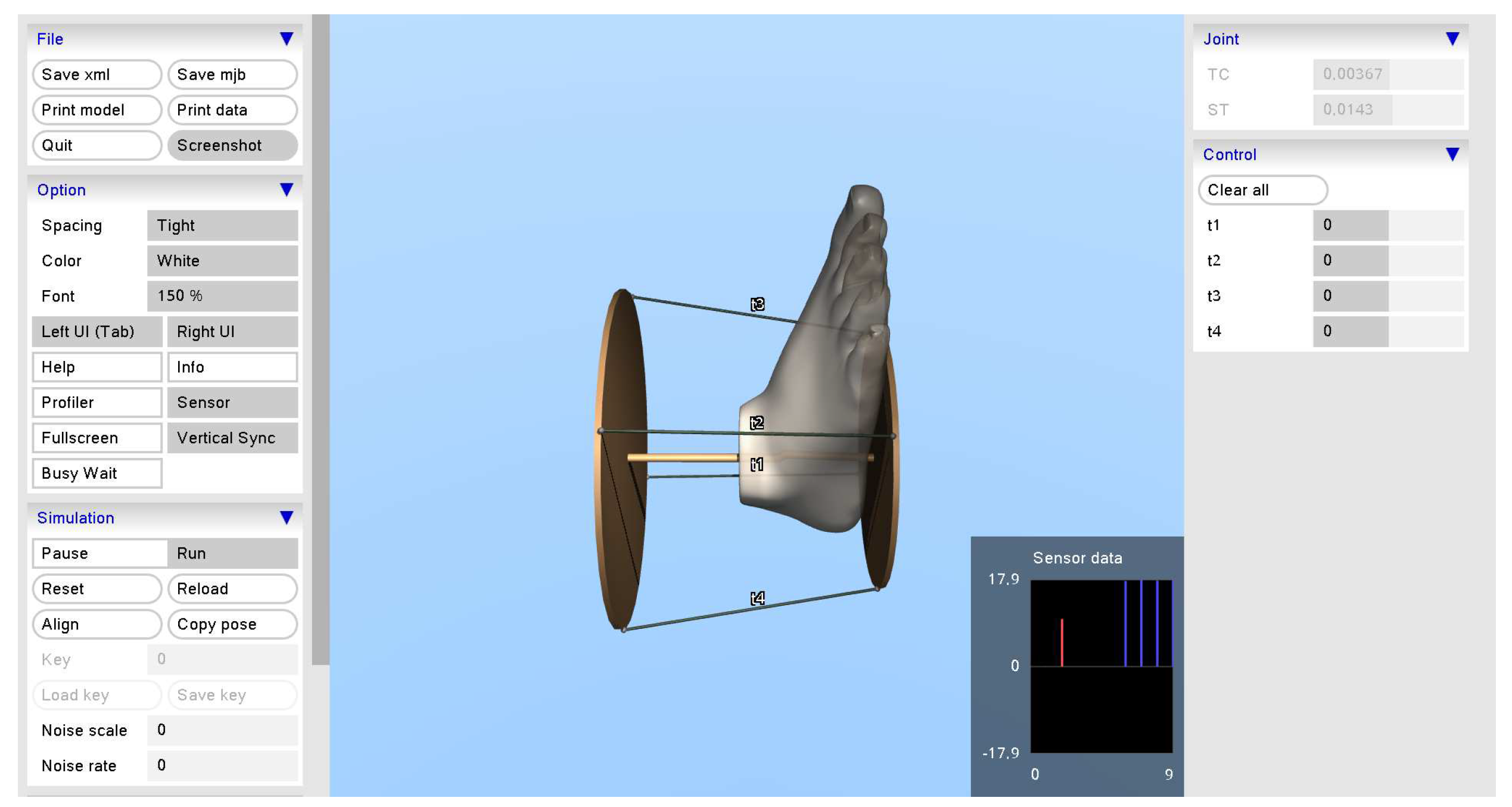

Figure 16.

Simulation at initial position.

Figure 16.

Simulation at initial position.

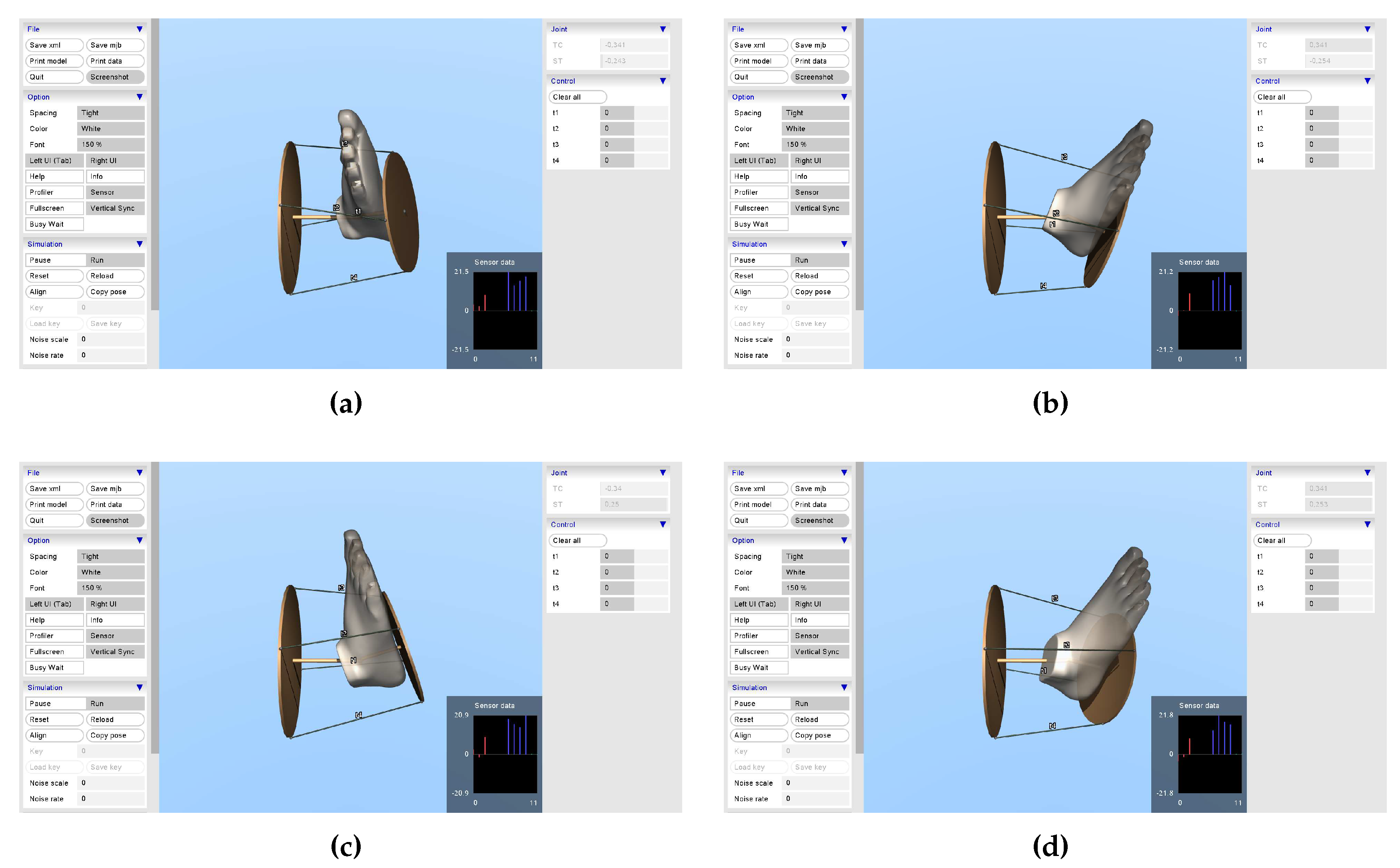

Figure 17.

Snapshots of MuJoCo Simulate with extreme angles configurations. a) Minimal TC and ST angles. (b)Maximal TC and ST minimal angles. c) Minimal TC and maximal ST angles. (b) TC and ST maximal angles.

Figure 17.

Snapshots of MuJoCo Simulate with extreme angles configurations. a) Minimal TC and ST angles. (b)Maximal TC and ST minimal angles. c) Minimal TC and maximal ST angles. (b) TC and ST maximal angles.

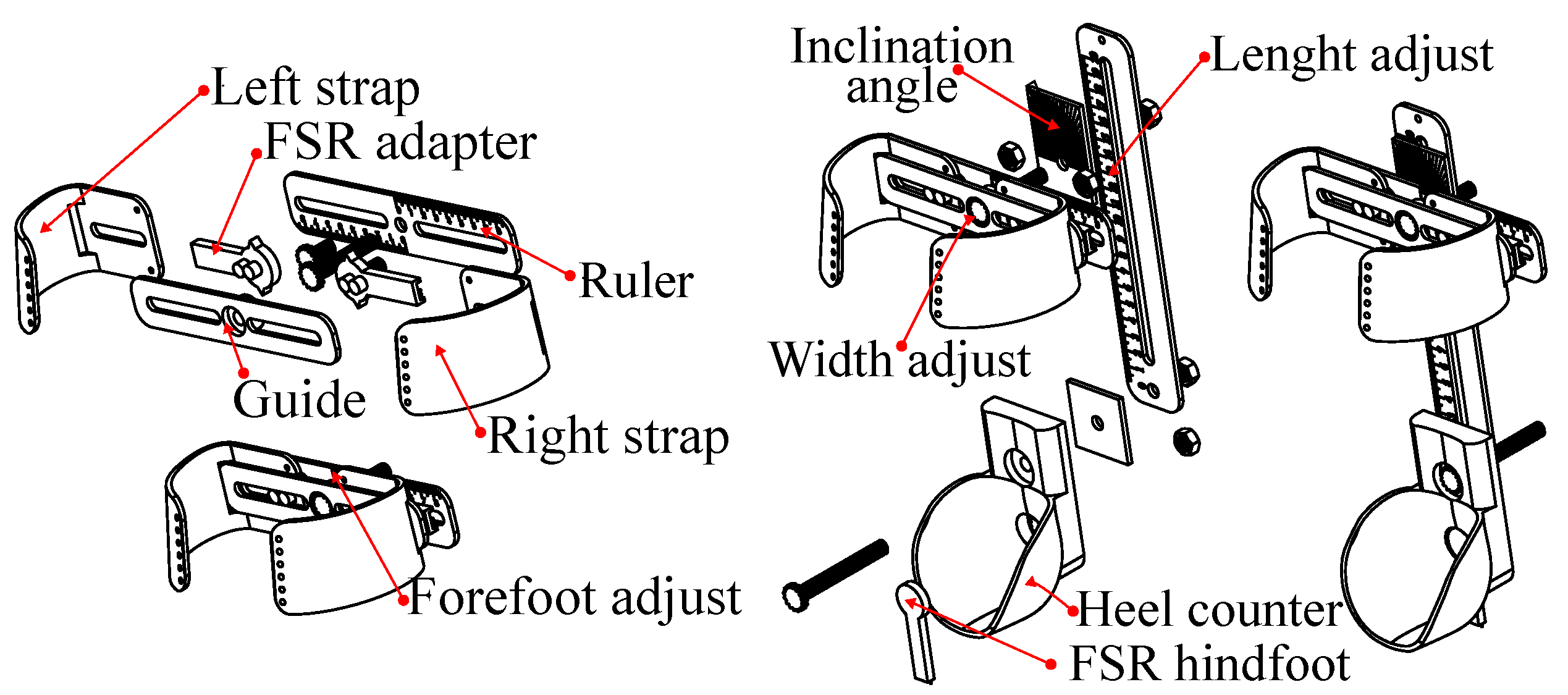

Figure 18.

Foot’s size adjust.

Figure 18.

Foot’s size adjust.

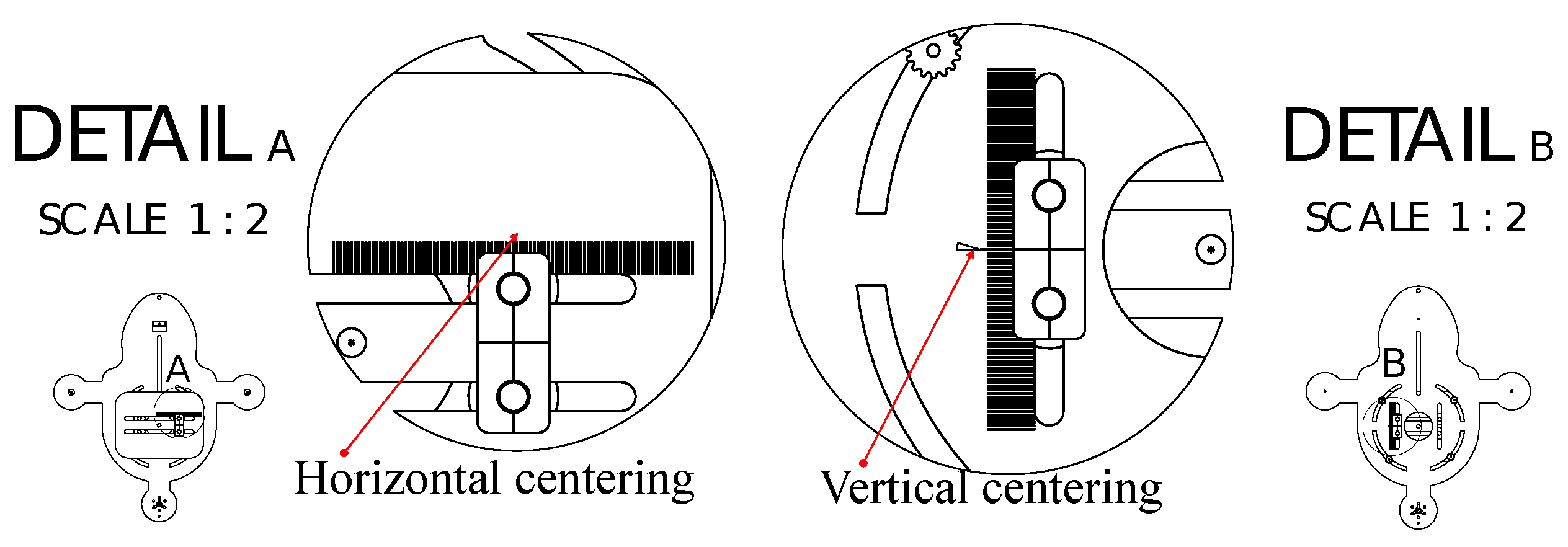

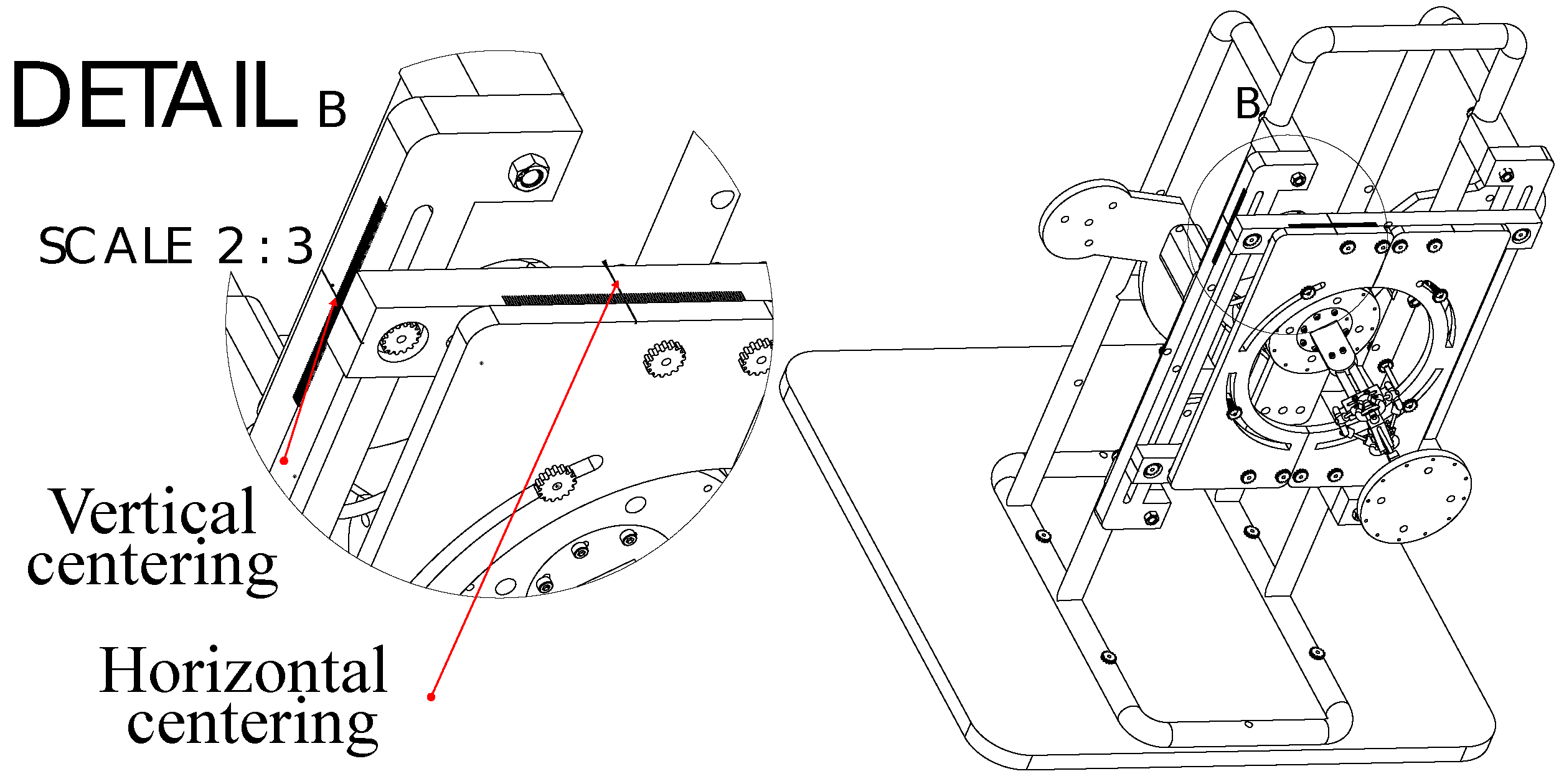

Figure 19.

Centering the platform.

Figure 19.

Centering the platform.

Figure 20.

Centering the base.

Figure 20.

Centering the base.

Table 1.

Size radius for the circumscribed triangles for the platform, base, and modules.

Table 1.

Size radius for the circumscribed triangles for the platform, base, and modules.

| Platform radius

|

Base radius

|

Module radius

|

| 115.698 mm. |

150.4074 mm. |

30 mm. |

Table 2.

Vertex position for a module centered at the origin.

Table 2.

Vertex position for a module centered at the origin.

| Sensor

|

Sensor

|

Sensor

|

| (30, 0, 0) |

(-15, 25.98, 0) |

(-15, -25.98, 0) |

Table 3.

Base reference vertexes.

Table 3.

Base reference vertexes.

| Base vertex A |

Base vertex B |

Base vertex C |

| (-150.4, 0, 0) |

(75.2, 130.3, 0) |

(75.2, -130.3, 0) |

Table 4.

Distances from the initial points to the corresponding sensors.

Table 4.

Distances from the initial points to the corresponding sensors.

| Sensor module |

Distance to

|

Distance to

|

Distance to

|

| A |

=176.2 |

=184.9 |

=184.9 |

| B |

=176.2 |

=311.1 |

=269.9 |

| C |

=293.9 |

=269.9 |

=311.1 |

Table 5.

Platform points computation.

Table 5.

Platform points computation.

| Point |

Original from the model |

Estimation from lengths |

|

(-115.7, 0, -176.18) |

(-115.7, -0, -176.18) |

|

(57.849, -100.2, -176.18) |

(57.849, -100.2, -176.18) |

|

(57.849, 100.2, -176.18) |

(57.849, 100.2, -176.18) |

Table 6.

Normal vector, angle, rotation axis for the talocrural axis estimation.

Table 6.

Normal vector, angle, rotation axis for the talocrural axis estimation.

| Trajectory |

Unitary normal vector |

Angle (rad) |

Talocrural axis direction |

| A |

(-0.10295, 0.97941, 0.17364) |

1.3963 |

(0.99452, 0.10453, 0) |

| B |

(-0.10293, 0.97942, 0.17364) |

1.3963 |

(0.99452, 0.10452, 0) |

| C |

(-0.10294, 0.97941, 0.17364) |

1.3963 |

(0.99452, 0.10452, 0) |

Table 7.

Circle-fitting for the talocrural axis estimation.

Table 7.

Circle-fitting for the talocrural axis estimation.

| Trajectory |

Center parallel to plane x-y |

Radius |

Estimated center |

| A |

(-10.76, 105.8, -18.68) |

134.5 |

(0.34535, 0.098175, -107.93) |

| B |

(-9.798, 106.1, -134.7) |

65.33 |

(13.265, -113.37, -128.29) |

| C |

(-14.11, 101.6, 61.59) |

111.9 |

(-11.603, 77.660, -90.225) |

Table 8.

Talocrural mean rotation axis and center.

Table 8.

Talocrural mean rotation axis and center.

| Trajectory estimation |

Mean rotation axis |

Mean trajectory center |

| Talocrural joint |

(-0.10294, 0.97941, 0.17364) |

(0.66912, -11.871, -108.81) |

Table 9.

Plane containing the trajectories A, B and C for the subtalar axis estimation.

Table 9.

Plane containing the trajectories A, B and C for the subtalar axis estimation.

| Trajectory |

Unitary normal vector |

Angle (rad) |

Subtalar Axis |

| A |

(0.73827, 0.20787, 0.64167) |

0.87412 |

(0.27102, -0.96257, 0) |

| B |

(0.73823, 0.20790, 0.64171) |

0.87407 |

(0.27108, -0.96256, 0) |

| C |

(0.73821, 0.20789, 0.64174) |

0.87404 |

(0.27107, -0.96256, 0) |

Table 10.

Circle-fitting for the subtalar axis estimation.

Table 10.

Circle-fitting for the subtalar axis estimation.

| Trajectory |

Center parallel to plane x-y |

Radius |

Estimated center |

| A |

(79.45, 26.55, -198.5) |

33.37 |

(-95.929, -22.830, -191.53) |

| B |

(84.05, 23.25, -91.18) |

129.8 |

(-13.335, -4.1798, -125.39) |

| C |

(84.50, 22.43, -49.52) |

130.7 |

(17.795, 3.6453, -98.822) |

Table 11.

Subtalar mean rotation axis and center.

Table 11.

Subtalar mean rotation axis and center.

| Trajectory estimation |

Mean rotation axis |

Mean trajectory center |

| Talocrural joint |

(0.73824, 0.20789, 0.64171) |

(-30.490, -7.7882, -138.58) |

Table 12.

Axes estimation.

Table 12.

Axes estimation.

| Axis direction vector |

Original |

Estimated |

Absolute error |

|

(-0.10294, 0.97941, 0.17365) |

(-0.10294, 0.97941, 0.17364) |

0.0000081395 |

|

(105.59, 11.098, 0) |

(104.51, 11.085, -0.56662) |

1.2164 |

|

(0.73822, 0.20791, 0.64172) |

(0.73824, 0.20789, 0.64171) |

0.000035358 |

|

(23.199, -84.478, 0.68201) |

(23.811, -82.740, -0.58889) |

2.2381 |

Table 13.

Negative angles group.

Table 13.

Negative angles group.

| Sample set i

|

Trajectory A |

Trajectory B |

Trajectory C |

| 1 |

(-85.819 9.2808 -210.81) |

(72.031 -102.03 -157.42) |

(82.714 97.870 -148.31) |

| 2 |

(-92.897 7.4419 -204.63) |

(69.681 -101.54 -161.62) |

(78.451 98.546 -154.65) |

| 3 |

(-99.503 5.5655 -197.97) |

(67.039 -101.10 -165.64) |

(73.747 99.122 -160.69) |

| 4 |

(-105.60 3.6610 -190.84) |

(64.117 -100.73 -169.48) |

(68.628 99.594 -166.39) |

| 5 |

(-111.17 1.7382 -183.30) |

(60.930 -100.42 -173.11) |

(63.118 99.960 -171.72) |

Table 14.

Points differences for negative angles.

Table 14.

Points differences for negative angles.

| Sample set i

|

|

|

| 1 |

(157.85 -111.31 53.392) |

(168.53 88.589 62.503) |

| 2 |

(162.58 -108.98 43.017) |

(171.35 91.104 49.982) |

| 3 |

(166.54 -106.66 32.322) |

(173.25 93.557 37.278) |

| 4 |

(169.72 -104.39 21.360) |

(174.23 95.933 24.456) |

| 5 |

(172.10 -102.16 10.188) |

(174.29 98.222 11.580) |

Table 15.

Rotation matrices vectors components.

Table 15.

Rotation matrices vectors components.

| Sample set i

|

Vector

|

Vector

|

Vector

|

| 1 |

(-0.336 -0.0250 0.942) |

(0.940 -0.0655 0.334) |

(0.0533 0.998 0.0455) |

| 2 |

(-0.269 -0.0217 0.963) |

(0.962 -0.0515 0.268) |

(0.0438 0.998 0.0348) |

| 3 |

(-0.201 -0.0175 0.979) |

(0.979 -0.0378 0.201) |

(70.0335 0.999 0.0247) |

| 4 |

(-0.132 -0.0123 0.991) |

(0.991 -0.0244 0.132) |

(0.0225 1.00 00154) |

| 5 |

(-0.0628 -0.00625 0.998) |

(0.998 -0.0113 0.0627) |

(0.0109 1.00 0.00694) |

Table 16.

Rotation matrices and angles.

Table 16.

Rotation matrices and angles.

| Sample set i

|

Rotation matrix |

Angle (Rad) |

Angle (Deg) |

| 1 |

|

0.34906 |

20.000 |

| 2 |

|

0.27784 |

15.919 |

| 3 |

|

0.20659 |

11.837 |

| 4 |

|

0.13536 |

7.7557 |

| 5 |

|

0.064138 |

3.6748 |

Table 17.

Positive angles group.

Table 17.

Positive angles group.

| Sample set i

|

Trajectory A |

Trajectory B |

Trajectory C |

| 1 |

(-119.75 -1.7381 -168.78) |

(54.579 -100.03 -179.05) |

(52.308 100.35 -180.30) |

| 2 |

(-123.68 -3.6604 -160.26) |

(50.741 -99.914 -181.99) |

(45.861 100.41 -184.46) |

| 3 |

(-126.97 -5.5639 -151.48) |

(46.707 -99.865 -184.66) |

(39.139 100.36 -188.16) |

| 4 |

(-129.63 -7.4390 -142.48) |

(42.496 -99.885 -187.04) |

(32.177 100.20 -191.39) |

| 5 |

(-131.62 -9.2762 -133.30) |

(38.130 -99.975 -189.12) |

(25.009 99.927 -194.12) |

Table 18.

Points differences for positive angles.

Table 18.

Points differences for positive angles.

| Sample set i

|

|

|

| 1 |

(174.33 -98.294 -10.271) |

(172.06 102.08 -11.522) |

| 2 |

(174.42 -96.253 -21.729) |

(169.54 104.07 -24.200) |

| 3 |

(173.68 -94.301 -33.178) |

(166.11 105.92 -36.685) |

| 4 |

(172.12 -92.446 -44.562) |

(161.80 107.64 -48.913) |

| 5 |

(169.75 -90.699 -55.822) |

(156.63 109.20 -60.822) |

Table 19.

Rotation matrix components for the positive angles.

Table 19.

Rotation matrix components for the positive angles.

| Sample set i

|

Vector

|

Vector

|

Vector

|

| 1 |

(0.0627 0.00694 0.998) |

(0.998 0.0109 -0.0628) |

(-0.0113 1.00 -0.00625) |

| 2 |

(0.132 0.0154 0.991) |

(0.991 0.0225 -0.132) |

(-0.0244 1.00 -0.0123) |

| 3 |

(0.201 0.0247 0.979) |

(0.979 0.0335 -0.201) |

(-0.0378 0.999 -0.0175) |

| 4 |

(0.268 0.0348 0.963) |

(0.962 0.0438 -0.269) |

(-0.0515 0.998 -0.0217) |

| 5 |

(0.334 0.0455 0.942) |

(0.940 0.0533 -0.336) |

(-0.0655 0.998 -0.0250) |

Table 20.

Rotation matrices for the positive angles.

Table 20.

Rotation matrices for the positive angles.

| Sample set i

|

Rotation matrix |

Angle (Rad) |

Angle (Deg) |

| 1 |

|

0.064138 |

3.6748 |

| 2 |

|

0.13536 |

7.7557 |

| 3 |

|

0.20659 |

11.837 |

| 4 |

|

0.27784 |

15.919 |

| 5 |

|

0.34906 |

20.000 |

Table 21.

Base-platform ratio and range of motion

Table 21.

Base-platform ratio and range of motion

| Base / Platform |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.4874 |

5.037 |

10.36 |

15.45 |

20.24 |

24.75 |

|

7.179 |

12.70 |

18.03 |

23.11 |

27.91 |

32.41 |

|

13.67 |

19.20 |

24.52 |

29.60 |

34.40 |

38.91 |

|

19.17 |

24.69 |

30.02 |

35.10 |

39.90 |

44.40 |

|

23.84 |

29.36 |

34.69 |

39.77 |

44.57 |

49.07 |

|

27.83 |

33.35 |

38.68 |

43.76 |

48.56 |

53.06 |

Table 22.

Angles in degrees for the maximum statistical height

Table 22.

Angles in degrees for the maximum statistical height

| Base / Platform |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.063 |

10.95 |

16.58 |

21.89 |

26.86 |

31.48 |

|

12.76 |

18.65 |

24.28 |

29.59 |

34.56 |

39.18 |

|

19.19 |

25.08 |

30.71 |

36.02 |

40.99 |

45.60 |

|

24.57 |

30.46 |

36.08 |

41.40 |

46.36 |

50.98 |

|

29.10 |

34.99 |

40.61 |

45.92 |

50.89 |

55.51 |

|

32.94 |

38.83 |

44.46 |

49.77 |

54.74 |

59.36 |

Table 23.

Angles in degrees for H minimum

Table 23.

Angles in degrees for H minimum

| Base / Platform |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-4.922 |

0.3028 |

5.380 |

10.26 |

14.90 |

19.28 |

|

2.676 |

7.902 |

12.98 |

17.85 |

22.49 |

26.88 |

|

9.189 |

14.42 |

19.49 |

24.37 |

29.01 |

33.39 |

|

14.76 |

19.98 |

25.06 |

29.94 |

34.58 |

38.96 |

|

19.53 |

24.75 |

29.83 |

34.71 |

39.35 |

43.73 |

|

23.63 |

28.86 |

33.94 |

38.81 |

43.45 |

47.84 |

Table 24.

Point positions at equilibrium.

Table 24.

Point positions at equilibrium.

| Points |

|

|

|

|

| Platform, z=-137.8 |

(65.45,65.45) |

(-65.45,-65.45) |

(65.45,-65.45) |

(-65.45,65.45) |

| Base, z=0 |

(85.08,85.08) |

(-85.08,-85.08) |

(85.08,-85.08) |

(-85.08,85.08) |

Table 25.

Reciprocal products.

Table 25.

Reciprocal products.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6635.7 |

-6635.7 |

6635.7 |

-6635.7 |

0 |

|

6218.6 |

-6218.6 |

-6218.6 |

6218.6 |

0 |

Table 26.

Projected axes intersection point.

Table 26.

Projected axes intersection point.

| Axis attitude |

Base intersection point |

Platform intersection point |

| Minimum |

(0.4040, -1.746, 0) |

(0.4040, -1.746, -176.2) |

| Mean |

(0.09698, -0.9111, 0) |

(0.09698, -0.9111, -176.2) |

| Maximum |

(-0.02179, -1.267, 0) |

(-0.02179, -1.267, -176.2) |

Table 27.

Subtalar and talocrural projection points.

Table 27.

Subtalar and talocrural projection points.

| Axis attitude |

TC mean

|

TC+sd

|

TC-sd

|

| ST mean |

(0.0943,-0.8973) |

(-0.0162,-0.9284) |

(0.2002,-0.8674) |

| ST+sd |

(0.1286,-1.224) |

(-0.0222,-1.2739) |

(0.2716,-1.1767) |

| ST-sd |

(0.20441 -1.9448) |

(-0.037303 -2.1371) |

(0.41105 -1.7805) |

Table 28.

Projected axes intersection point for Q maximum.

Table 28.

Projected axes intersection point for Q maximum.

| Axis attitude |

TC mean

|

TC+sd

|

TC-sd

|

| ST mean |

(0.15090 -1.4357) |

(-0.025929 -1.4855) |

(0.32043 -1.3879) |

| ST+sd |

(0.20584 -1.9585) |

(-0.035578 -2.0383) |

(0.43467 -1.8828) |

| ST-sd |

(0.32705 -3.1117) |

(-0.059684 -3.4193) |

(0.65768 -2.8487) |

Table 29.

Projected axes intersection point for Q minimum.

Table 29.

Projected axes intersection point for Q minimum.

| Axis attitude |

TC mean

|

TC+sd

|

TC-sd

|

| ST mean |

(0.037724 -0.35892) |

(-0.0064823 -0.37137) |

(0.080107 -0.34698) |

| ST+sd |

(0.051460 -0.48961) |

(-0.0088946 -0.50957) |

(0.10867 -0.47070) |

| ST-sd |

(0.081764 -0.77793) |

(-0.014921 -0.85483) |

(0.16442 -0.71219) |

Table 30.

Anchor point computation at initial position.

Table 30.

Anchor point computation at initial position.

| Computed variables |

TC Mean attitude |

Maximum |

Minimum |

|

(-0.103, 0.979, 0.174) |

(0.0174, 0.994, 0.105) |

(-0.218, 0.945, 0.242) |

|

(106, 11.1, 0) |

(107, -1.87, 0) |

(102, 23.5, 0) |

|

(0.738, 0.208, 0.642) |

(0.629, 0.208, 0.749) |

(0.703, 0.559, 0.439) |

|

(23.2, -84.5, 0.682) |

(23.1, -72.7, 0.796) |

(62.7, -79.9, 1.48) |

|

0.70045 |

0.61696 |

0.56287 |

|

40.13 |

35.35 |

32.25 |

|

0.87035 |

0.95383 |

1.0079 |

|

49.87 |

54.65 |

57.75 |

| Vector 1 |

(814.89, -552.28) |

(800.68, -589.28, 0) |

(915.54, -319.9, 0) |

| Vector 2 |

(-430.17, -634.71) |

(-392.70, -533.57, 0) |

(-296.26, -847.89, 0) |

| Ap1 |

(-76.52, 51.02,-176.2) |

(-74.45, 53.95, -176.2) |

(-87.28, 29.62, -176.2) |

| Ap2 |

(76.72, -52.84,-176.2) |

(74.64, -55.78, -176.2) |

(87.47, -31.44, -176.2) |

| Ap3 |

(52.03, 75.71,-176.2) |

(54.96, 73.63, -176.2) |

(30.63, 86.47, -176.2) |

| Ap4 |

(-51.83, -77.53,-176.2) |

(-54.77, -75.46,-176.2) |

(-30.43, -88.29,-176.2) |

| Ab1 |

(-99.51, 66.59, 0) |

(-96.81, 70.41, 0) |

(-113.5, 38.78, 0) |

| Ab2 |

(99.70, -68.42, 0) |

(97.00, -72.23, 0) |

(113.7, -40.60, 0) |

| Ab3 |

(67.60, 98.69, 0) |

(71.42, 96.00, 0) |

(39.79, 112.7, 0) |

| Ab4 |

(-67.41, -100.5, 0) |

(-71.23, -97.82, 0) |

(-39.59, -114.5, 0) |

Table 31.

Configuration angle from x direction.

Table 31.

Configuration angle from x direction.

| Attitude |

|

|

|

|

| Mean (rad) |

2.554 |

-0.603 |

0.969 |

-2.16 |

| Mean

|

146.31 |

-34.58 |

55.5 |

-123.8 |

Table 32.

Configuration angle from x direction for maximum attitude.

Table 32.

Configuration angle from x direction for maximum attitude.

| Attitude |

|

|

|

|

| Mean (rad) |

2.5145 |

-0.64173 |

0.9296 |

-2.1986 |

| Mean

|

144.07 |

-36.768 |

53.262 |

-125.97 |

Table 33.

Configuration angle from x direction for minimum attitude.

Table 33.

Configuration angle from x direction for minimum attitude.

| Attitude |

|

|

|

|

| Mean (rad) |

2.8144 |

-0.34505 |

1.2304 |

-1.9027 |

| Mean

|

161.25 |

-19.77 |

70.495 |

-109.02 |

Table 34.

Cable lenghts at initial position.

Table 34.

Cable lenghts at initial position.

|

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

|

178.35 |

178.35 |

178.35 |

178.35 |

Table 35.

Rotation center and for extreme angles corresponding to axes’ mean attitude values.

Table 35.

Rotation center and for extreme angles corresponding to axes’ mean attitude values.

|

|

|

|

(4.130, -0.2039, -110.8) |

(24.31, -10.56, -170.9) |

|

(4.130, -0.2039, -110.8) |

(18.91, 13.42, -171.8) |

|

(1.361, -0.1503, -112.7) |

(-19.34, -15.01, -171.7) |

|

(1.361, -0.1503, -112.7) |

(-27.31, 8.175, -169.6) |

Table 36.

Anchor points , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to axes’ mean attitude values.

Table 36.

Anchor points , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to axes’ mean attitude values.

|

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

|

(-30.03, 55.68, -204.3) |

(78.32, -78.59, -137.2) |

(91.65, 50.21, -156.4) |

(24.308, -10.561, -170.9) |

|

(-62.04, 54.72, -185.9) |

(100.3, -29.63, -157.9) |

(55.68, 92.49, -142.9) |

(-17.38, -67.40, -200.9) |

|

(-90.97, 42.28, -164.9) |

(52.40, -74.07, -178.1) |

(33.27, 52.65, -204.8) |

(-71.83, -84.44, -138.2) |

|

(-103.9, 40.46, -130.3) |

(49.78, -25.83, -209.4) |

(8.315, 92.79, -172.7) |

(-62.48, -78.16, -167.0) |

Table 37.

Cable lengths , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to axes’ mean attitude values.

Table 37.

Cable lengths , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to axes’ mean attitude values.

|

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

|

216.09 |

139.28 |

165.48 |

188.75 |

|

190.06 |

162.63 |

143.57 |

209.71 |

|

166.87 |

184.39 |

212.67 |

139.23 |

|

133.02 |

219.41 |

182.69 |

168.58 |

Table 38.

Anchor points , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to the axes’ maximum attitude values.

Table 38.

Anchor points , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to the axes’ maximum attitude values.

|

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

|

(-27.37, 58.02, -203.7) |

(75.66, -80.94, -137.8) |

(93.70, 47.56, -155.1) |

(-45.41, -70.47, -186.5) |

|

(-60.56, 57.79, -184.8) |

(98.87, -32.70, -159.1) |

(58.81, 90.79, -142.4) |

(-20.50, -65.70, -201.5) |

|

(-88.87, 44.90, -166.2) |

(50.31, -76.69, -176.8) |

(36.01, 50.34, -205.0) |

(-74.58, -82.13, -138.0) |

|

(-102.5, 43.75, -130.5) |

(48.34, -29.12, -209.2) |

(11.27, 91.44, -174.2) |

(-65.44, -76.81, -165.5) |

Table 39.

Cable lengths , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to the axes’ maximum orientation values.

Table 39.

Cable lengths , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to the axes’ maximum orientation values.

|

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

|

215.61 |

139.75 |

164 |

190.24 |

|

188.76 |

163.92 |

143.07 |

210.22 |

|

168.3 |

182.95 |

212.98 |

138.93 |

|

133.3 |

219.1 |

184.38 |

166.92 |

Table 40.

Anchor points , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to the axes’ minimum attitude values.

Table 40.

Anchor points , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to the axes’ minimum attitude values.

|

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

|

(-45.54, 37.61, -206.9) |

(93.82, -60.52, -134.7) |

(75.49, 65.37, -165.5) |

(-27.20, -88.28, -176.1) |

|

(-68.69, 32.80, -192.9) |

(107.0, -7.706, -151.0) |

(33.63, 100.6, -147.5) |

(4.678, -75.55, -196.4) |

|

(-102.1, 22.74, -156.6) |

(63.49, -54.54, -186.4) |

(13.12, 65.28, -201.9) |

(-51.68, -97.07, -141.0) |

|

(-110.5, 17.42, -130.9) |

(56.29, -2.786, -208.8) |

(-12.59, 98.43, -162.5) |

(-41.58, -83.80, -177.2) |

Table 41.

Cable lengths , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to the axes’ minimum attitude values.

Table 41.

Cable lengths , , , and for extreme angles corresponding to the axes’ minimum attitude values.

|

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

, mm |

|

217.78 |

137.59 |

175.76 |

178.48 |

|

198.15 |

154.65 |

148.13 |

205.04 |

|

157.79 |

193.59 |

209.14 |

142.63 |

|

132.71 |

219.8 |

171.29 |

179.9 |

Table 42.

Data for MuJoCo.

Table 42.

Data for MuJoCo.

| Identification |

Value |

| Reference |

0 -0.0911 17.6273 |

| base cylinder fromto |

-0.4 -0.0911 17.6273 0 -0.0911 17.6273 |

| b1 |

0 6.6595 7.6668 |

| b2 |

0 -6.8417 27.5878 |

| b3 |

0 9.8694 24.3779 |

| b4 |

0 -10.0516 10.8767 |

| leg capsule fromto |

0 -0.0911 17.6273 10.8442 -0.1037 17.6286 |

| shnk pos |

0 10.8442 -0.1037 17.6286 |

| comp capsule fromto |

10.8442 -0.1037 17.6286 11.1964 -0.0117 17.909 |

| TC hinge pos, axis |

110.8442 -0.1037 17.6286, -0.174 0.979 -0.103 |

| b-foot capsule fromto |

11.1964 -0.0117 17.909 17.6176 -0.0911 17.6273 |

| ST hinge pos, axis |

-0.0117 17.909, -0.642 0.208 0.738 |

| ptfm cylinder fromto |

17.6176 -0.0911 17.627 18.0176 -0.0911 17.6273 |

| a-foot refpos |

-10.8442 0.1037 -17.6286 |

| p1 |

17.6176 5.1016 9.9653 |

| p2 |

17.6176 -5.2838 25.2893 |

| p3 |

17.6176 7.57 22.82 |

| p4 |

17.6176 -7.753 12.4345 |

| t1 range |

17.83503 17.83513 |

| t2 range |

17.83503 17.83513 |

| t3 range |

17.83503 17.83513 |

| t4 range |

17.83503 17.83513 |

Table 43.

Sensors output in MuJoCo.

Table 43.

Sensors output in MuJoCo.

| Sensor |

Measurement |

| Accelerometer at the platform |

-0.065 -0.096 9.8 |

| Gyro at the platform |

3.4e-14 -2.7e-13 4e-14 |

| Length tendon 1 |

18 |

| Length tendon 2 |

18 |

| Length tendon 3 |

18 |

| Length tendon 4 |

18 |

| Talocrural joint in radians |

0.014 |

| Subtalar joint in radians |

0.0037 |

Table 44.

Changes on tendon lenghts.

Table 44.

Changes on tendon lenghts.

| Configuration N |

t1,t2,t3,t4,

(input, cm) |

Acc. |

Gyr. |

t1,t2,t3,t4,

(output, cm) |

TC(r) |

ST(r) |

| 1 |

21.6,13.92,16.54,18.87 |

3.4 2.5 8.8 |

0,0,0 |

21,14,17,19 |

-0.24 |

-0.34 |

| 2 |

19,16.26,14.35,20.96 |

2.6 -1.5 9.3 |

0,0,0 |

19,16,14,21 |

0.25 |

-0.34 |

| 3 |

16.68,18.43,21.26,13.92 |

-2.7 0.35 9.4 |

0,0,0 |

17,18,21,14 |

-0.25 |

0.34 |

| 4 |

13.3,21.94,18.26,16.85 |

-3.9 -1.4 8.9 |

0,0,0 |

13,18,18,17 |

0.25 |

0.34 |