Submitted:

29 September 2023

Posted:

29 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection and Data Collection

2.2. Results Surgery and Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy Procedure

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lurvink, R.J.; Villeneuve, L.; Govaerts, K.; de Hingh, I.; Moran, B.J.; Deraco, M.; Van der Speeten, K.; Glehen, O.; Kepenekian, V.; Kusamura, S. The Delphi and GRADE Methodology Used in the PSOGI 2018 Consensus Statement On Pseudomyxoma Peritonei And Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Eur. J. Surg. oncol. 2021, 47, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiriart, E.; Deepe, R.; Wessels, A. Mesothelium and Malignant Mesothelioma. J. Dev. Biol. 2019, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moolgavkar, S.H.; Meza, R.; Turim, J. Pleural and Peritoneal Mesotheliomas in SEER: Age Effects And Temporal Trends, 1973-2005. Cancer causes & control. 2009, 20, 935–944. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, S.J.; Larson, T.C.; Wu, M.; Antao, V.C.; Lewis, M.; Pinheiro, G.A.; et al. Mesothelioma incidence in 50 states and the District of Columbia, United States, 2003-2008. International journal of occupational and environmental health. 2013, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, B.; Ware, A. Time Trend of Mesothelioma Incidence in The United States and Projection of Future Cases: An Update Based On SEER Data for 1973 Through 2005. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2009, 39, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, V.; Löseke, S.; Nowak, D.; Herth, F.J.; Tannapfel, A. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Incidence, Etiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, And Occupational Health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013, 110, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kusamura, S.; Kepenekian, V.; Villeneuve, L.; Lurvink, R.J.; Govaerts, K.; De Hingh, I.H.J.T.; Moran, B.J.; Van der Speeten, K.; Deraco, M.; Glehen, O.; PSOGI. Peritoneal mesothelioma: PSOGI/EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines For Diagnosis, Treatment And Follow-Up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021, 47, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, V.P.; Recchia, L.; Cafferata, M.; Porta, C.; Siena, S.; Giannetta, L.; Morelli, F.; Oniga, F.; Bearz, A.; Torri, V.; Cinquini, M. Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma: A Multicenter Study On 81 Cases. Ann Oncol. 2010, 21, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, T.C.; Yan, T.D.; Morris, D.L. Outcomes of Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Mesothelioma: The Australian Experience. J. surg. Oncol. 2009, 99, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roife, D.; Powers, B.D.; Zaidi, M.Y.; Staley, C.A.; Cloyd, J.M.; Ahmed, A.; Grotz, T.; Leiting, J.; Fournier, K.; Lee, A.J.; Veerapong, J.; Baumgartner, J.M.; Clarke, C.; Patel, S.H.; Hendrix, R.J.; Lambert, L.; Abbott, D.E.; Pokrzywa, C.; Lee, B.; Blakely, A.; Greer, J.; Johnston, F.M.; Laskowitz, D.; Dessureault, S.; Dineen, S.P. CRS/HIPEC with Major Organ Resection in Peritoneal Mesothelioma Does not Impact Major Complications or Overall Survival: A Retrospective Cohort Study of the US HIPEC Collaborative. Ann.surg. oncol 2020, 27, 4996–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, J.T.; Johnston, F.M.; Gamblin, T.C.; Turaga, K.K. Current Trends In The Management Of Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 3947–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- eldman, A.L.; Libutti, S.K.; Pingpank, J.F.; Bartlett, D.L.; Beresnev, T.H.; Mavroukakis, S.M.; Steinberg, S.M.; Liewehr, D.J.; Kleiner, D.E.; Alexander, H.R. Analysis of Factors Associated With Outcome In Patients With Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma Undergoing Surgical Debulking And Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2003, 21, 4560–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaga, K.K.; Deraco, M.; Alexander, H.R. Current Management Strategies for Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Int. J. Hyperthermia. 2017, 33, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker, P.H.; Turaga, K.K.; Alexander, H.R., Jr; Deraco, M.; Hesdorffer, M. Management of Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma Using Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Chemotherapy. J. Oncol.Pract. 2016, 12, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.D.; Deraco, M.; Baratti, D.; Kusamura, S.; Elias, D.; Glehen, O.; Gilly, F.N.; Levine, E.A.; Shen, P.; Mohamed, F.; Moran, B.J.; Morris, D.L.; Chua, T.C.; Piso, P.; Sugarbaker, P.H. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: multi-institutional experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 6237–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, H.; Moran, B.J.; Cecil, T.D.; Murphy, E.M. Cytoreductive Surgery and Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy For Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 35, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarbaker, P.H.; Welch, L.S.; Mohamed, F.; Glehen, O. A Review of Peritoneal Mesothelioma at the Washington Cancer Institute. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003, 12, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deraco, M.; Nonaka, D.; Baratti, D.; Casali, P.; Rosai, J.; Younan, R.; Salvatore, A.; Cabras, A.D.; Kusamura, S. Prognostic Analysis Of Clinicopathologic Factors In 49 Patients With Diffuse Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma Treated With Cytoreductive Surgery And Intraperitoneal Hyperthermic Perfusion. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 13, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesdorffer, M.E.; Chabot, J.A.; Keohan, M.L.; Fountain, K.; Talbot, S.; Gabay, M.; Valentin, C.; Lee, S.M.; Taub, R.N. Combined Resection, Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy, And Whole Abdominal Radiation For The Treatment Of Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Am J Clin Oncol.. 2008, 31, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackham, A.U.; Shen, P.; Stewart, J.H.; Russell, G.B.; Levine, E.A. Cytoreductive Surgery With Intraperitoneal Hyperthermic Chemotherapy For Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma: Mitomycin Versus Cisplatin. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 17, 2720–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, J.H.; Miura, J.T.; Glenn, J.A.; Marcus, R.K.; Larrieux, G.; Jayakrishnan, T.T.; Donahue, A.E.; Gamblin, T.C.; Turaga, K.K.; Johnston, F.M. Cytoreductive Surgery And Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy For Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 1686–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jänne, P.A.; Wozniak, A.J.; Belani, C.P.; Keohan, M.L.; Ross, H.J.; Polikoff, J.A. Open-Label Study Of Pemetrexed Alone Or In Combination With Cisplatin For The Treatment Of Patients With Peritoneal Mesothelioma: Outcomes Of An Expanded Access Program. Clin. llung. cancer. 2005, 7, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carteni, G.; Manegold, C.; Garcia, G.M.; Siena, S.; Zielinski, C.C.; Amadori, D.; Liu, Y.; Blatter, J.; Visseren-Grul, C.; Stahel, R. Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma-Results From The International Expanded Access Program Using Pemetrexed Alone Or In Combination With A Platinum Agent. Lung Cancer. 2009, 64, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deraco, M.; Baratti, D.; Hutanu, I.; Bertuli, R.; Kusamura, S. The Role Of Perioperative Systemic Chemotherapy In Diffuse Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma Patients Treated With Cytoreductive Surgery And Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, H.R., Jr; Bartlett, D.L.; Pingpank, J.F.; Libutti, S.K.; Royal, R.; Hughes, M.S.; Holtzman, M.; Hanna, N.; Turner, K.; Beresneva, T.; Zhu, Y. Treatment factors associated with long-term survival after cytoreductive surgery and regional chemotherapy for patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Surgery. 2013, 153, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Y.; Aycart, S.; Mandeli, J.P.; Heskel, M.; Sarpel, U.; Labow, D.M. Extreme Cytoreductive Surgery And Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy: Outcomes From A Single Tertiary Center. Surg Oncol. 2015, 24, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; de Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; de Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; Graf, R.; Vonlanthen, R.; Padbury, R.; Cameron, J.L.; Makuuchi, M. The Clavien-Dindo Classification Of Surgical Complications: Five-Year Experience. Ann Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, P.; Sugarbaker, P.H. Clinical Research Methodologies In Diagnosis And Staging Of Patients With Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Cancer Res Treat. 1996, 82, 359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Sugarbaker, P.H. Management Of Peritoneal-Surface Malignancy: The Surgeon's Role. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999, 384, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarbaker, P.H.; Yan, T.D.; Stuart, O.A.; Yoo, D. Comprehensive Management Of Diffuse Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 32, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarbaker, P.H. Peritonectomy Procedures. Ann.Surg. 1995, 221, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.D.; Deraco, M.; Elias, D.; Glehen, O.; Levine, E.A.; Moran, B.J.; Morris, D.L.; Chua, T.C.; Piso, P.; Sugarbaker, P.H. A Novel Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) Staging System Of Diffuse Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma Using Outcome Analysis Of A Multi-Institutional Database. Cancer. 2011, 117, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusamura, S.; Torres Mesa, PA.; Cabras, A.; Baratti, D.; Deraco, M. The Role of Ki-67 and Pre-cytoreduction Parameters in Selecting Diffuse Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma (DMPM) Patients for Cytoreductive Surgery (CRS) and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC). Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical Procedure | ||

| Extreme CRS | 15 | 48.4 |

| Less Extensive CRS | 16 | 51.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 14 | 45.2 |

| Male | 17 | 54.8 |

| Complications | ||

| No | 19 | 61.3 |

| Yes | 12 | 38.7 |

| CC Score | ||

| 0 | 13 | 41.9 |

| 1 | 18 | 58.1 |

| Asbest Exposure | ||

| No | 8 | 25.8 |

| Yes | 23 | 74.2 |

| Prior Abdominal Surgery | ||

| No | 21 | 67.7 |

| Yes | 10 | 32.3 |

| ASA Class | ||

| 2 | 8 | 25.8 |

| 3 | 17 | 54.8 |

| 4 | 6 | 19.4 |

| Reoperation | ||

| No | 26 | 83.9 |

| Yes | 5 | 16.1 |

| Readmission | ||

| No | 24 | 77.4 |

| Yes | 7 | 22.6 |

| Clavien Dindo 3-4 Complications | ||

| No | 24 | 77.4 |

| Yes | 7 | 22.6 |

| Mean± S.D | Median (min - max) | |

| Age | 62.55 ± 7.24 | 64 (45 - 78) |

| PCI | 20.68 ± 5.49 | 21 (12 - 30) |

| LOHS (days) | 13.74 ± 3.74 | 14 (7 - 21) |

| Survival (months) | 35.03 ± 12.23 | 40 (5 - 60) |

| EBL (ml) | 335.32 ± 102.43 | 300 (200 - 550) |

| BMI | 28.1 ± 2.72 | 27 (25 - 33) |

| Operative Time (hours) | 6.84 ± 1.24 | 7 (4.5 - 10) |

| ICU LOS (days) | 2.52 ± 1.03 | 3 (1 - 4) |

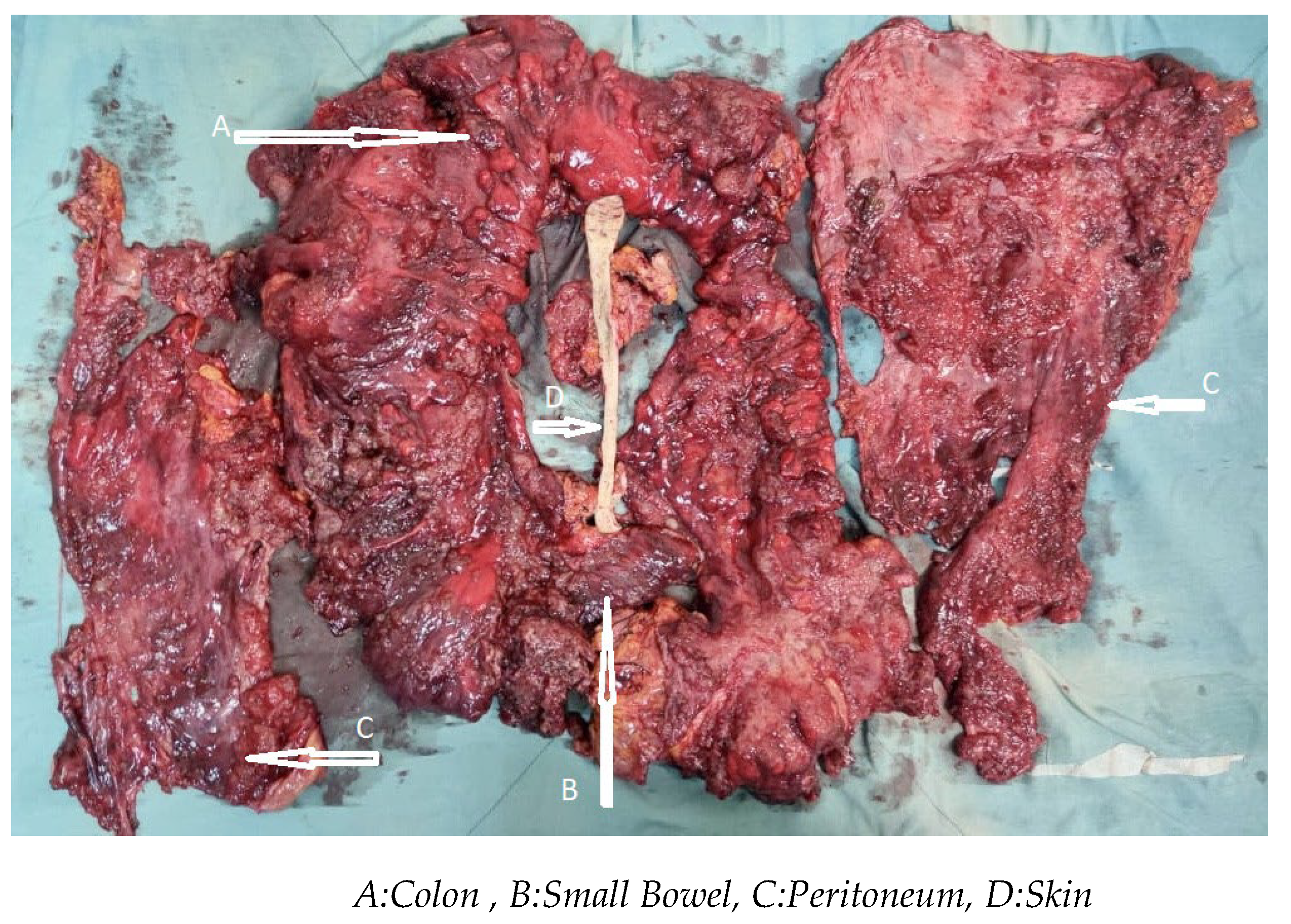

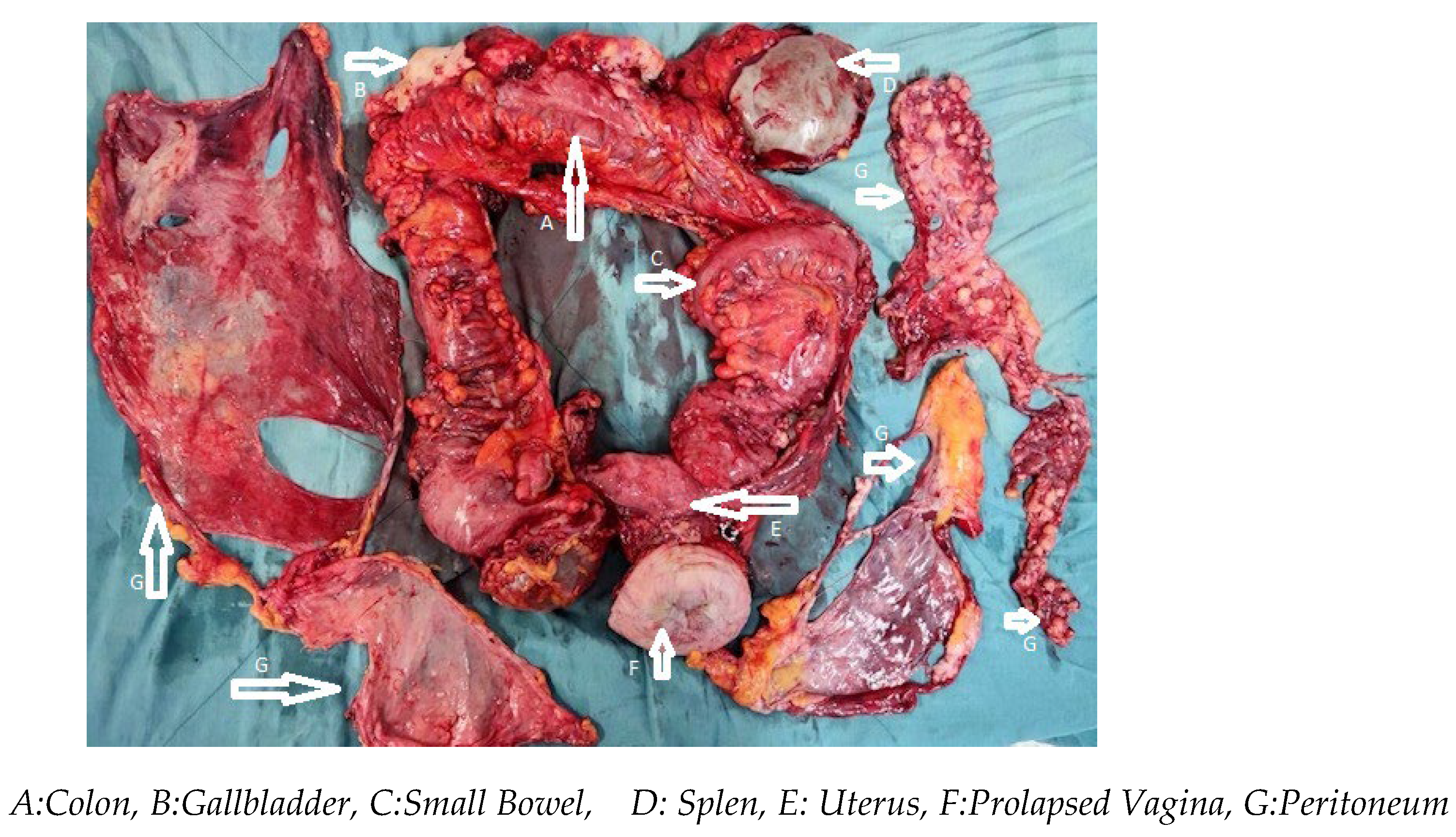

| Organ resected | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Colon | 14(19.4) |

| Small bowel | 13 (18.0) |

| Spleen | 10 (13.8) |

| Gallbladder | 8 (11.1) |

| Uterus/vagen/over | 6 (8.3) |

| Stomach | 6(8.3) |

| Diaphragm | 5 (6.9) |

| Left | 3(4.1) |

| Right | 2(2.7) |

| Rectum | 4(5.5) |

| Pancreas | 4(5.5) |

| Liver | 2(2.7) |

| Group | Total | Statistic tests | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eCRS | leCRS | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 6 (40) | 8 (50) | 14 (45.2) | 0.039 | 0.843** |

| Male | 9 (60) | 8 (50) | 17 (54.8) | ||

| Complications | |||||

| No | 6 (40) | 13 (81.2) | 19 (61.3) | 3.95 | 0.047** |

| Yes | 9 (60) | 3 (18.8) | 12 (38.7) | ||

| CC Score | |||||

| 0 | 7 (46.7) | 6 (37.5) | 13 (41.9) | 0.023 | 0.879** |

| 1 | 8 (53.3) | 10 (62.5) | 18 (58.1) | ||

| Asbest.exposure | |||||

| No | 3 (20) | 5 (31.3) | 8 (25.8) | --- | 0.685*** |

| Yes | 12 (80) | 11 (68.8) | 23 (74.2) | ||

| Prior Abdominal Surgery | |||||

| No | 8 (53.3) | 13 (8.,3) | 21 (67.7) | --- | 0.135*** |

| Yes | 7 (46.7) | 3 (18.8) | 10 (32.3) | ||

| ASA class | |||||

| Sınıf 2 | 2 (13.3) | 6 (37.5) | 8 (25.8) | 4.698 | 0.095* |

| Sınıf 3 | 8 (53.3) | 9 (56.3) | 17 (54.8) | ||

| Sınıf 4 | 5 (33.3) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (19.4) | ||

| Reoperation | |||||

| No | 13 (0.87) | 13 (0.81) | 26 (0.84) | --- | 1.000*** |

| Yes | 2 (0.13) | 3 (0.19) | 5 (0.16) | ||

| Readmission | |||||

| No | 12 (80) | 12 (75) | 24 (77.4) | --- | 1.000*** |

| Yes | 3 (20) | 4 (25) | 7 (22.6) | ||

| Clavien Dindo 3-4 Complications | |||||

| No | 12 (80) | 12 (75) | 24 (77.4) | --- | 1.000*** |

| Yes | 3 (20) | 4 (25) | 7 (22.6) | ||

| Grup | St.Test | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e CRS +HIPEC+EPIC | le Procedure | Total | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | Mean (min - max) | Mean ± SD | Mean (min - max) | Mean ± SD | Mean (min - max) | |||

| Age | 60.27 ± 9.18 | 60 (45 - 78) | 64.69 ± 4.01 | 65 (58 - 71) | 62.55 ± 7.24 | 64 (45 - 78) | -1.717 | 0.102* |

| PCI | 25.27 ± 3.03 | 26 (21 - 30) | 16.38 ± 3.28 | 17 (12 - 24) | 20.68 ± 5.49 | 21 (12 - 30) | 7.814 | <0.001* |

| LOHS (days) | 16.13 ± 2.8 | 15 (13 - 21) | 11.5 ± 3.1 | 11.5 (7 - 18) | 13.74 ± 3.74 | 14 (7 - 21) | 27 | <0.001** |

| Survival (months) | 34.47 ± 11.7 | 40 (5 - 49) | 35.56 ± 13.06 | 39.5 (5 - 60) | 35.03 ± 12.23 | 40 (5 - 60) | -0.245 | 0.808* |

| EBL (ml) | 398.67 ± 100.84 | 400 (250 - 550) | 275.94 ± 60.97 | 272.5 (200 - 400) | 335.32 ± 102.43 | 300 (200 - 550) | 4.068 | <0.001* |

| BMI | 26.47 ± 1.81 | 26 (25 - 32) | 29.63 ± 2.58 | 29 (25 - 33) | 28.1 ± 2.72 | 27 (25 - 33) | 35 | <0.001** |

| Operative Time (hours) | 7.6 ± 1.03 | 7.45 (6,15 - 10) | 6.13 ± 0.99 | 6 (4.5 - 8) | 6.84 ± 1.24 | 7 (4.5 - 10) | 4.042 | <0.001* |

| ICU LOS ( days) | 3.2 ± 0.68 | 3 (2 - 4) | 1.88 ± 0.89 | 2 (1 - 4) | 2.52 ± 1.03 | 3 (1 - 4) | 31.5 | <0.001** |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (%95 CI) | p | HR (%95 CI) | p | |

| Age | 0.932 (0.856 – 1.015) | 0.105 | ||

| PCI | 1.034 (0.942 – 1.136) | 0.483 | 0.767 (0.558 – 1.056) | 0.104 |

| LOHS (days) | 1.033 (0.906 – 1.176) | 0.630 | 1.516 (0.993 – 2.313) | 0.054 |

| EBL (ml) | 0.999 (0.995 – 1.004) | 0.786 | ||

| BMI | 0.921 (0.76 – 1.116) | 0.401 | ||

| Operative Time (hours) | 1.061 (0.702 – 1.603) | 0.778 | 0.616 (0.176 – 2.151) | 0.447 |

| ICU LOS (days) | 1.039 (0.655 – 1.646) | 0.872 | ||

| Means (%95 CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| eCRS | 37.5 (30.6 – 44.4) | 0.895 |

| le CRS | 42.8 (33.7 – 51.8) | |

| Overall | 43.0 (36.5 – 49.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).