1. Introduction

Detecting toxins, other harmful chemical substances, microbiologic parasites, contamination of pathogens, etc., is crucial in today's food industry. Mass food production constantly meets such problems. Therefore, the critical issue is an early response to the contamination, which is possible with the necessary measurement equipment. This article proposes advanced AI – classification of eggshells origin from a healthy hen or MS-infected one by means of spectral analysis.

As mentioned, MS is a bacteria that can be transmitted from infected hens to their eggs. When present in the oviducts of chickens, it causes changes in the eggshell surface, resulting in thinning and increased transparency in various areas of the shells [

1,

2]. Many methods have been developed to detect MS infection. Serological tests such as the serum plate agglutination test (SPA), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)[

3,

4], and hemagglutination inhibition test (HI) are commonly used for diagnosis [

5,

6]. Culture methods using pleuropneumonia-like organisms (PPLO) broth can also be employed, but they are time-consuming, even taking up to 28 days [

7]. Molecular methods, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [

8,

9,

10] and its variations like real-time PCR [

11], multi-plex PCR, loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], and polymerase spiral reaction (PSR), are widely used for MS detection. PSR, for instance, is 100 times more sensitive than PCR and has a higher positive rate (69.9%) than ELISA (65.3%).

Authors propose different approaches to detecting MS infection to those mentioned above. The proposed method may be used directly on the farm by staff members with limited qualifications, veterinary doctors, assistants, or customs officers. It involves spectral, rapid measurement with data post-processing and AI classification. Classifying samples' biological origins through spectral data analysis is now a trend, i.e., honey types classification [

16] or whether the egg comes from MS-infected chicken or healthy chicken [

17,

18,

19].

Given the wide range of possible biological samples and their inherent variations, numerous approaches are employed for analysing obtained spectral data. Moreover, spectral data may also vary depending on what kind of spectral response is measured: transmittance, reflectance, absorption, scattering, fluorescence, etc. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is one of the most popular data analysis methods [

20,

21]. However, due to factors like subraces, age of hens, egg colouring, diet, and climate, egg-shells' diversity is so extensive that standard PCA algorithms prove ineffective. Alternative ap-proaches, such as using classifiers like the Spanning tree combined with various data re-duction techniques, can be successfully employed, as shown in [

18]. Employing this clas-sifier in the specific case leads to analysing multiple levels in a tree structure. In their re-search, the authors concluded that machine learning algorithms were the most efficient for differentiating egg origin: healthy or MS-infected hens.

The presented paper is a fruitful follow-up of previously done work. Two optical sys-tem configurations, one with transmitted light and the other with reflected light, were al-ready made and tested for analysis and classification of eggshells. In the case of transmit-ted light analysis on chicken eggs, they achieved an accuracy of 88.8%, specifically for white eggshells [

17]. The measurements can be conducted without destroying the egg by utilising reflective light, making them more applicable in industrial settings. Eggshells from infected and non-infected chickens exhibit distinct reflective properties. The study conducted by the authors [

19,

22] demonstrated that it is possible to detect changes caused by MS infection in a chicken flock by analysing back-reflected signals from eggshells at selected spectral wavelengths of a white light source. By employing machine learning al-gorithms, the researchers were able to differentiate tested samples of various origins with a reasonable probability. In the case of white eggshells, the F-scores reached 95.75%, while for brown eggshells, the F-scores reached 86.21%[

22], while by using modified machine learning algorithms, F-scores for white eggshells 86% while for brown eggshells 96% [

18]. The last two results, reported in [

19,

22], were obtained in the portable multispectral fi-bre-optics reflectometer that uses selected single-colour LEDs instead of a broadband light source and an optical fibre bundle.

Deep learning methods are sometimes employed in more complex scenarios requiring information about molecules. This approach was utilised by Gosh et al. in their work, where they used deep learning to predict molecular excitation spectra [

15]. Their results demonstrated that this type of network could achieve up to 97% accuracy in learn-ing spectra and infer spectra solely from molecular data. Joung et al. [

23] presented a sim-ilar application of deep learning, where they successfully predicted seven optical proper-ties related to organic compounds. Additionally, this method has been proven effective in drug identification, as shown by Ting et al. [

24]. This approach enables efficient work in this field. However, as demonstrated above, less complex machine learning methods are predominantly used to analyse the spectra distribution for any material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

Authors used portable multispectral fibre-optics reflectometer for further AI classification. A dataset comprising 2521 eggshell samples was prepared. This dataset consisted of brown and white eggshells originating from healthy hens or infected. The quantity of each subset of samples is presented in

Table 1.

The samples classified as healthy were sourced from the inner reference flock of the Department of Poultry Diseases, National Veterinary Research Institute (NVRI). On the other hand, the MS-infected eggs were obtained from commercial flocks under the veterinary supervision of the NVRI. The infection status of these eggs was confirmed using three techniques: specific MS PCR, LAMP, and sequencing of the vlhA gene.

2.2. Portable Multispectral Fibre-Optic Reflectometer

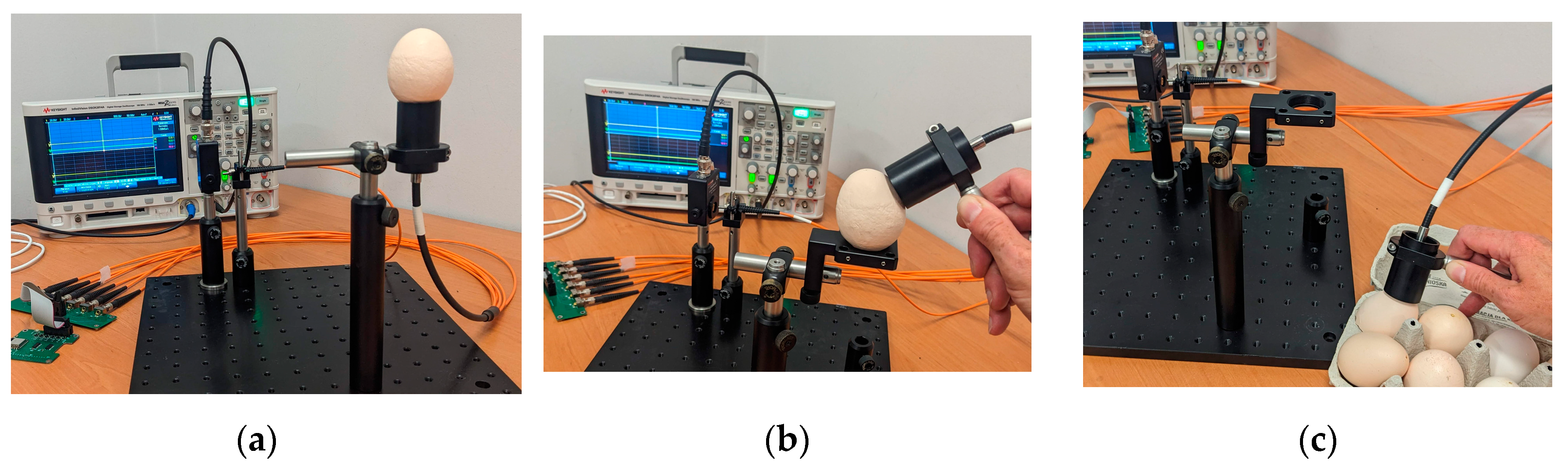

All spectral measurements, which results were discussed above, were performed on Portable Multispectral Fibre-Optic Reflectometer [

19]. The eggshell, the whole egg or part of it in question, is placed on the measurement head. The measurement head can also be manually oriented and positioned regarding the sample, and the spectral measurement is then performed. The eggshell is sequentially illuminated by the light emitted by six LEDs covering the visible electromagnetic wave region. The dominant wavelengths and spectral range (FWHM) of used LEDs are shown in

Table 2. The key issue of LEDs selection for this system is their spectral separation therefore the FWHMs parameter are so important. The light is introduced to the measurement head by the 1x7 fun-out fibre-optic bundle, which gives the possibility to reach the sample from the desired angle flexibly. The possible scenarios of measurement head – egg positions are shown in

Figure 1.

The signal carrying the measurement information is gathered by means of back reflection from the sample. It travels through the central core of the 1x7 fun-out fibre-optic bundle to the detector. The single measurement cycle lasts less than 1 s. The signal is preprocessed and then introduced to the AI algorithm. Details on the Portable Multispectral Fibre-Optic Reflectometer design, operation and signal processing have been widely discussed in [

19].

2.3. AI classification

The increasing accessibility of advanced measurement methods in biological sciences has led to a growing adoption of sophisticated data processing techniques to extract valuable information effectively. Machine learning approaches have become particularly advantageous in this context, with a rapid growth of solutions emerging in this field. These solutions are well-suited for data classification or clustering in biological sciences, including DNA and spectroscopic data analysis. Recently, we embarked on analysing such data specifically for studying the occurrence of MS, achieving a detection level of (F-score) up to 96% [

19,

22]. We employed the Support Vector Machine (SVM) method for data analysis, a commonly used approach [

25]. The essence of SVM is to calculate the best hyperplane that separates different data classes while maintaining a maximum margin of confidence. Our algorithm was based on Radial Basis Functions (RBF) [

26,

27]. Despite the many advantages of SVM, it has a few drawbacks, one of which can significantly impact the prediction results for the data we obtain in our portable multispectral fibre-optics reflectometer. Specifically, SVM does not perform optimally when the input dataset consists of overlapping values assigned to different classes.

Consequently, we decided to employ a different classification algorithm in our subsequent study. Our choice fell on the Self-Organizing Tree Algorithm (SOTA), an unsupervised neural network with a binary tree topology. It was developed in 1997 by Dopazo and Carazo [

28]. SOTA combines hierarchical clustering and a Self-Organizing Map (SOM) based on a single-layer neural network [

29]. In SOTA, the processing time is approximately directly proportional to the number of elements to be classified. This presents a clear advantage over SVM, which is perceived as slow when dealing with large datasets. The processing in SOTA begins with the node exhibiting the highest diversity, which is then divided into two nodes called cells. The splitting process can be stopped at any node.

The data processing was performed using KNIME version 4.5.0. KNIME is an open-source platform that offers various components suitable for data exploration. One of these components includes the implementation of the SOTA algorithm. However, the SVM algorithm is not available in the set of KNIME components. This is not a problem since the creators of this environment have provided a feature that enables running Python code, through which access to the SVM algorithm can be achieved. Unfortunately, we could not find an implementation of the SOTA algorithm in any of the Python libraries.

3. Results

The data collected using the portable multispectral fibre-optics reflectometer were divided into two independent groups in the analysis: one representing white eggshells and the other representing brown eggshells. Within each of these groups, there were two subgroups: one consisted of eggshells from healthy chickens and one from diseased chickens. The data from each group were processed separately. In the first step, the data were randomly divided into training data and validation data at a ratio of 7:3. The training data were normalised to unity, and the normalisation parameters were recorded. In the second step, the SOTA network was trained. After completing the training, the third step involved normalising the test data using the normalisation parameters calculated from the training data. The final stage was prediction, and the results were recorded in the output dataset. All these steps were repeated one hundred times to mitigate the influence of random data arrangement. The final result was calculated as the average for this set.

The machine learning algorithm's performance was evaluated based on F-score, Precision, and Recall metrics. These metrics are based on the values of TP (true positives), TN (true negatives), FP (false positives), and FN (false negatives) [

26].

The Precision is calculated as Precision = TP / (TP + FP) and indicates how well the algorithm correctly classifies instances relative to all the data identified as correct.

The Recall is calculated similarly as Recall = TP / (TP + FN), but it refers to all the elements that should have been identified as correct.

F-score is calculated as F-score = 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall). It represents their harmonic mean. This metric helps identify whether either Precision or Recall is too low.

The results of the eggshell origin classifications quality for white and brown eggs obtained using the portable multispectral fibre-optic reflectometer and the SOTA algorithm are shown in

Table 3.

The use of the SOTA algorithm proved to be justified in the case of the analysed data. Compared to the SVM algorithm, the average Precision increased by 0.08 across all groups, with the maximum increase observed in the case of diseased white eggs at 0.18. Regarding Recall, the increases were 0.08 and 0.17, respectively, with the maximum difference occurring in healthy white eggs. For the F-score parameter, the overall result also improved by an average of 0.08, with a maximum value of 0.13 observed in both diseased and healthy white eggs.

Based on the analysis of the eggshells, the proposed solution detects the presence of Mycoplasma in the flock with an average precision, Recall, and F-score level of 0.99. Our next goal is to conduct real-world tests on a significantly larger sample. If these tests confirm the laboratory findings, we can consider it a complete success and contemplate implementing the solution.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Mycoplasmas belong to the class Mollicutes, the smallest and simplest self-replicating bacterial pathogens. Therefore, they have no cell wall and have lost many biochemical pathways, making them obligate parasites highly dependent on their host. The known virulence mechanisms of virulent strains of mycoplasmas are adhesion, invasion, cell exit and cytotoxicity. Some strains of mycoplasmas can be extremely cytotoxic to their hosts, which may be related to the presence of variable surface antigens, lipoproteins.

Mycoplasma synoviae (MS) is a bacterium that has the ability to penetrate cells, causing significant damage to commercial poultry populations if not prevented. Hemagglutinin

VlhA is a highly expressed lipoprotein and the main immunodominant surface protein of

M. synoviae involved in host-parasite interaction, mediating binding to host erythrocytes [

30,

31]. Membrane lipoproteins are able to activate macrophages, thus playing an important role in cytokine production and, consequently, in the inflammatory response during infection [

32]. The

VlhA protein generates the N-terminal fragment of the MSPB lipoprotein and the C-terminal fragment of MSPA, which is directly involved in hemadherence [

33]. The length of the MSPB lipoprotein differs between

M. synoviae isolates, which alters their hemagglutination phenotype and may be related to changes in the antigenic determinants of MSPB and MSPA [

30,

31,

33,

34].

M. synoviae processes involved in tissue invasion and degradation in the avian body involve the expression of cysteine proteases (CysP), which can cleave chicken IgG into Fab and Fc fragments, thus facilitating their survival in the host [

35].

In

M. synoviae, a tightly bound sialidase activity is observed [

36,

37,

38,

39], as well as the enzymatic activity of NanH neuraminidase, which can desialylate chicken tracheal mucus glycoproteins and chicken IgG heavy chain, thus contributing to

M. synoviae colonisation and persistent infection [

39,

40,

41].

Infections with

M. synoviae can be subclinical. However, clinical signs can be associated with the respiratory and musculoskeletal systems of birds, especially chickens and turkeys, and the reproductive systems. This pathogen is responsible for a condition called infectious synovitis, which is characterised by inflammation of the synovial membrane in the joints. Birds infected with MS may exhibit lameness, swollen joints, and reduced mobility. In commercial poultry flocks, the developed infection can lead to severely reduced growth rates, decreased egg production, and poor overall performance. In addition to its impact on the musculoskeletal system, MS can also cause respiratory problems. Infected birds may show signs such as nasal discharge, sneezing, coughing, and difficulty breathing. These respiratory symptoms can further compromise the overall health of the birds and make them more susceptible to secondary infections.

Mycoplasma synoviae is highly contagious and can spread rapidly through direct contact with infected birds and through contaminated equipment, feed, and water sources. The bacterium can survive in the environment for several weeks, making it a persistent threat to poultry farms. [

33,

34,

35,

36]

Controlling MS requires strict biosecurity measures, such as isolating infected birds, maintaining clean facilities, and disinfecting equipment. Vaccination is also an important tool in preventing and managing the disease. However, it is worth noting that the bacterium can develop resistance to certain antibiotics over time, complicating treatment efforts. Overall, Mycoplasma synoviae poses a significant risk to poultry health and productivity. Poultry producers need to remain vigilant and take proactive measures to prevent and control its spread within their flocks. Regular monitoring, proper biosecurity protocols, and timely intervention can help mitigate the negative impact of this pathogen on poultry populations.

To effectively manage Mycoplasma synoviae infection in poultry, it is essential to enforce stringent biosecurity practices. This involves measures like segregating already infected birds, maintaining hygienic facilities, and thoroughly disinfecting equipment. Additionally, vaccination is crucial in preventing and handling this disease. It's important to recognise that the bacterium can become resistant to specific antibiotics over time, which can complicate treatment efforts. In summary, Mycoplasma synoviae poses a significant threat to the health and productivity of poultry. Poultry producers must remain alert and take proactive steps to prevent its transmission among their flocks. Consistent monitoring, adhering to sound biosecurity procedures, and prompt intervention are key strategies to minimise the adverse impact of this pathogen on poultry populations. The measurement device and AI-based approach to data analysis allow harnessing the pathogen by fast and reliable monitoring of farm waste.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, AP and PM; methodology, AP; software, SP; validation, AP, SP and LRJ; formal analysis, SP; investigation, AP.; resources, O.K.; data curation, SP; writing—original draft preparation, AP, SP, OK; writing—review and editing, AP and PM; visualisation, PM; supervision, LRJ; project administration, AP; funding acquisition, PM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Military University of Technology grant no. UGB 22-806 and Institute of Micromechanics and Photonics statutory grant.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Feberwee, A.; De Wit, JJ; Landman, W.J.M. Induction of eggshell apex abnormalities by Mycoplasma synoviae: Field and experimental studies. Avian Pathol. 2009, 38, 77–85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kursa, O.; Pakuła, A.; Tomczyk, G.; Paśko, S.; Sawicka, A. Eggshell apex abnormalities caused by two different Mycoplasma synoviae genotypes and evaluation of eggshell anomalies by full-field optical coherence tomography. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, S.; Kariya, M.; Nagano, K.; Yokoyama, S.-I.; Fukao, T.; Yamazaki, Y. , New rapid enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect antibodies against bacterial surface antigens using filtration plates, Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 25, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galikowska, E.; Kunikowska, D.; Tokarska-Pietrzak, E.; Dziadziuszko, H.; Łoś, JM; Golec, P. et al., Specific detection of Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli strains by using ELISA with bacteriophages as recognition agents. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 30, 1067–1073. [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, Z.; Karwowski, M.; Paśko, S.; Kursa, O.; Pakuła, A.; Sałbut L. Combined optical coherence tomography and spectral technique for detection of changes in eggshells caused by Mycoplasma synoviae, In Speckle 2018, Proceedings of the SPIE 10834: VII International Conference on Speckle Metrology, Janów Podlaski, Poland, 10-12 September 2018; M. Kujawińska; L.R. Jaroszewicz; 108341M. 12 September.

- Feberwee, A.; de Vries, T.S.; Landman, W.J.M. Seroprevalence of Mycoplasma synoviae in Dutch commercial poultry farms. Avian Pathol. 2018, 37, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleven, S. Mycoplasmas in the etiology of multifactorial respiratory disease. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcka, O.; Campo, F.J.D.; Muñoz, F.X. Pathogen detection: a perspective of traditional methods and biosensors, Biosens. Bioelectron. 2007, 22, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; García, M.; Leiting, V.; Bencina, D.; Dufour-Zavala, L.; Zavala, G.; Kleven, S.H. Specific detection and typing of Mycoplasma synoviae strains in poultry with PCR and DNA sequence analysis targeting the hemagglutinin encoding gene vlhA. Avian Dis. 2004, 48, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, P.P.; Ramírez, A.S.; Morrow, C.J.; Bradbury, J.M. Development and evaluation of an improved diagnostic PCR for Mycoplasma synoviae using primers located in the haemagglutinin encoding gene vlhA and its value for strain typing. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 136, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, Z.; Kleven, S.H. The development of diagnostic real-time TaqMan PCRs for the four pathogenic avian mycoplasmas. Avian Dis. 2009, 53, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, A.P.; de Vargas, T.; Ikuta, N.; Fonseca, A.S.K.; Celmer, Á.J.; Marques, E.K. ; Lunge, VR A multiplex real-time PCR for detection of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae in clinical samples from Brazilian commercial poultry flocks. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursa, O.; Woźniakowski, G.; Tomczyk, G.; Sawicka, A.; Minta, Z. Rapid detection of Mycoplasma synoviae by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Arch. Microbiol. 2014, 197, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kursa, O.; Tomczyk, G.; Sawicka, A. Prevalence and phylogenetic analysis of Mycoplasma synoviae strains isolated from Polish chicken layer flocks. J. Veter. Res. 2019, 63, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, K.; Stuke, A.; Todorović, M.; Jørgensen, P. B.; Schmidt, M. N.; Vehtari, A.; Rinke, P. , Deep Learning Spectroscopy: Neural Networks for Molecular Excitation Spectra. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1801367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, Z.; Paśko, S.; Pakuła, A.; Teper, D.; Sałbut, L. An attempt to classify the botanical origin of honey using visible spectroscopy. JSFA 2021, 101, 5272–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenc, Z.; Paśko, S.; Kursa, O.; Pakuła, A.; Sałbut, L. Spectral technique for detection of changes in eggshells caused by Mycoplasma synoviae. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 3481–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenc, Z.; Paśko, S.; Pakuła, A.; Kursa, O.; Sałbut L. Spectral VIS Measurements for Detection Changes Caused by of Mycoplasma Synoviae in Flock of Poultry. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 1044, Proceedings of Mechatronics 2019—Computing in Mechatronics, Warsaw, Poland, September 16–18; Szewczyk, R., Krejsa, J., Nowicki, M., Ostaszewska-Liżewska, A.; Springer, Cham.

- Pakuła, A.; Żołnowski, W.; Paśko, S.; Kursa, O.; Marć, P.; Jaroszewicz, L.R. Multispectral Portable Fibre-Optic Reflectometer for the Classification of the Origin of Chicken Eggshells in the Case of Mycoplasma synoviae Infections. Sensors 2022, 22, 8690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, J.R.; Esmonde-White, F.W.L. Exploration of Principal Component Analysis: Deriving Principal Component Analysis Visually Using Spectra, App. Spectrosc. 2021, 75, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Goswami, U.; King, M.; Chen, J. In Situ Detection of Live-to-Dead Bacteria Ratio After Inactivation by Means of Synchronous Fluorescence and PCA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2018, 115, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakuła, A.; Paśko, S.; Kursa, O.; Komar, R. Reflected Light Spectrometry and AI-Based Analysis for Detection of Rapid Chicken Eggshell Change Caused by Mycoplasma Synoviae. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, J. F.; Han, M.; Hwang, J.; Jeong, M.; Choi, D. H.; Park, S. , Deep Learning Optical Spectroscopy Based on Experimental Database: Potential Applications to Molecular Design. JACS Au 2021, 1, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H. W.; Chung, S. L.; Chen, C. F; et al. , A drug identification model developed using deep learning technologies: experience of a medical center in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y. RBF kernel based support vector machine with universal approximation and its application. Comput. Vis. 2004, 3173, 512–517. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, K.; Prakash, B.; Kanagachidambaresan, G.R. Sparse kernel machines. In Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dopazo J, Carazo JM. Phylogenetic reconstruction using an unsupervised growing neural network that adopts the topology of a phylogenetic tree. J Mol. Evol. 1997, 44, 226–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiber, M. A. Fundamental Overview of SOTA-Ensemble Learning Methods for Deep Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. SITech 2021, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noormohammadi, A.H.; Markham, P.F.; Duffy, M.F.; Whithear, K.G.; Browning, G.F. Multigene Families Encoding the Major Hemagglutinins in Phylogenetically Distinct Mycoplasmas. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 3470–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benčina, D.; Drobnič-Valič, M.; Horvat, S.; Narat, M.; Kleven, S.H.; Dovč, P. Molecular Basis of the Length Variation in the N-Terminal Part of Mycoplasma Synoviae Hemagglutinin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 203, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson-Noel, N.; Noormohammadi, A.H. Mycoplasma Synoviae Infection. In Diseases of poultry; Swayne, D.E., Glisson, J.R., McDougald, L.R., Nolan, L.K., Suarez, D.L., Nair, V.L., Eds.; Wiley: Ames, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Noormohammadi, A.H.; Markham, P.F.; Whithear, K.G.; Walker, I.D.; Gurevich, V.A.; Ley, D.H.; Browning, G.F. Mycoplasma Synoviae Has Two Distinct Phase-Variable Major Membrane Antigens, One of Which Is a Putative Hemagglutinin. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 2542–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narat, M.; Benčina, D.; Kleven, S.H.; Habe, F. The Hemagglutination-Positive Phenotype of Mycoplasma Synoviae Induces Experimental Infectious Synovitis in Chickens More Frequently than Does the Hemagglutination-Negative Phenotype. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 6004–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cizelj, I.; Berčič, R.L.; Dušanić, D.; Narat, M.; Kos, J.; Dovč, P.; Benčina, D. Mycoplasma Gallisepticum and Mycoplasma Synoviae Express a Cysteine Protease CysP, Which Can Cleave Chicken IgG into Fab and Fc. Microbiology (N Y) 2011, 152, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.; Kleven, S.H.; Brown, D.R. Sialidase Activity in Mycoplasma Synoviae. Avian. Dis. 2007, 51, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.; Brown, D.R. Diversity of Expressed VlhA Adhesin Sequences and Intermediate Hemagglutination Phenotypes in Mycoplasma Synoviae. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2116–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, K.; Mullen, N.; Canter, J.A.; Ley, D.H.; May, M. Phenotypic Diversity in an Emerging Mycoplasmal Disease. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 138, 103798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiwen, C.; Yueyue, W.; Lianmei, Q.; Cuiming, Z.; Xiaoxing, Y. Infection Strategies of Mycoplasmas: Unraveling the Panoply of Virulence Factors. Virulence 2021, 12, 788–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berčič, R.L.; Cizelj, I.; Dušanić, D.; Narat, M.; Zorman-Rojs, O.; Dovč, P.; Benčina, D. Neuraminidase of Mycoplasma Synoviae Desialylates Heavy Chain of the Chicken Immunoglobulin G and Glycoproteins of Chicken Tracheal Mucus. Avian Pathol. 2011, 40, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berčič, R.L.; Cizelj, I.; Benčina, M.; Narat, M.; Bradbury, J.M.; Dovč, P.; Benčina, D.Š. Demonstration of Neuraminidase Activity in Mycoplasma Neurolyticum and of Neuraminidase Proteins in Three Canine Mycoplasma Species. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 155, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).