Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

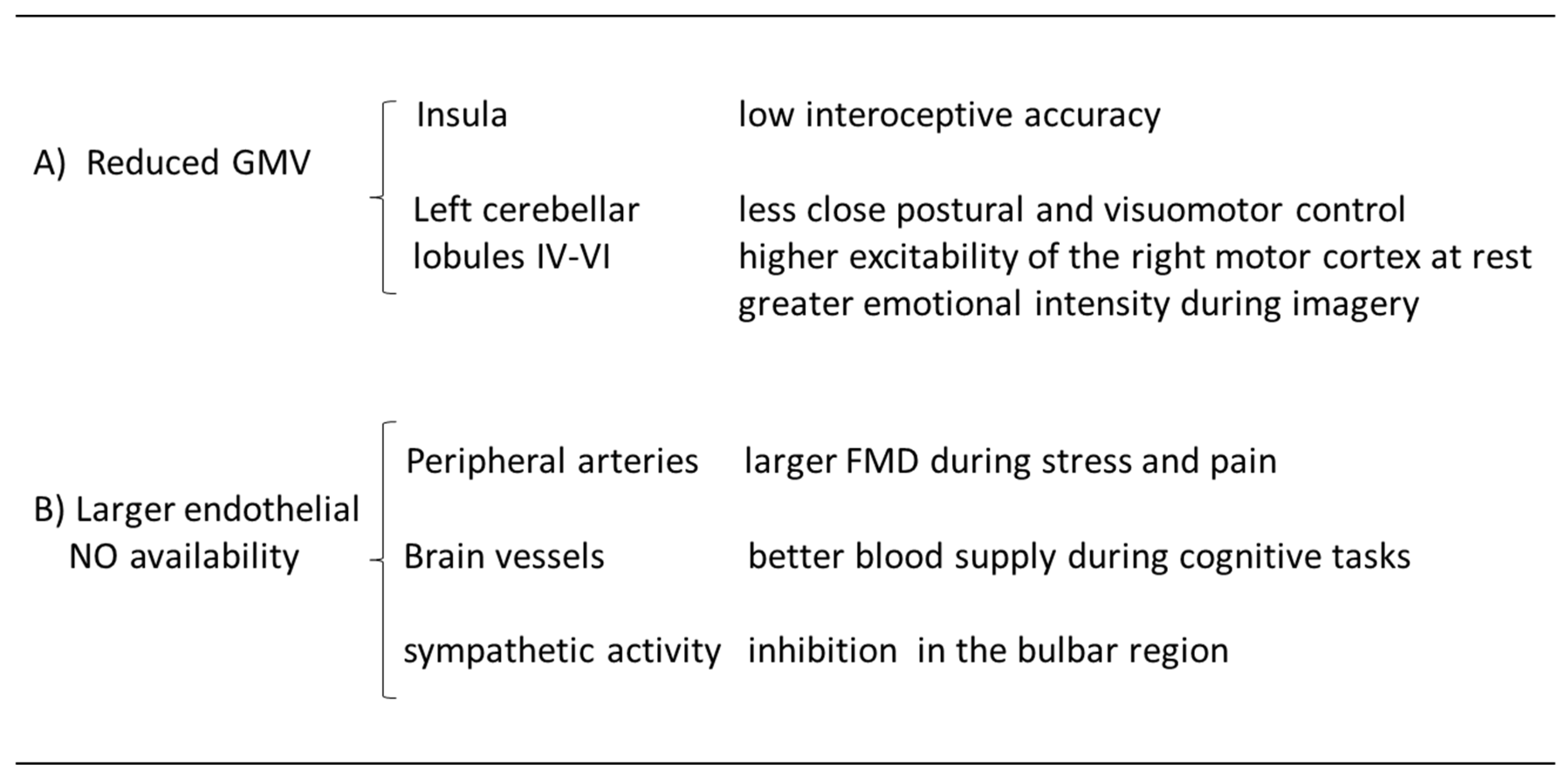

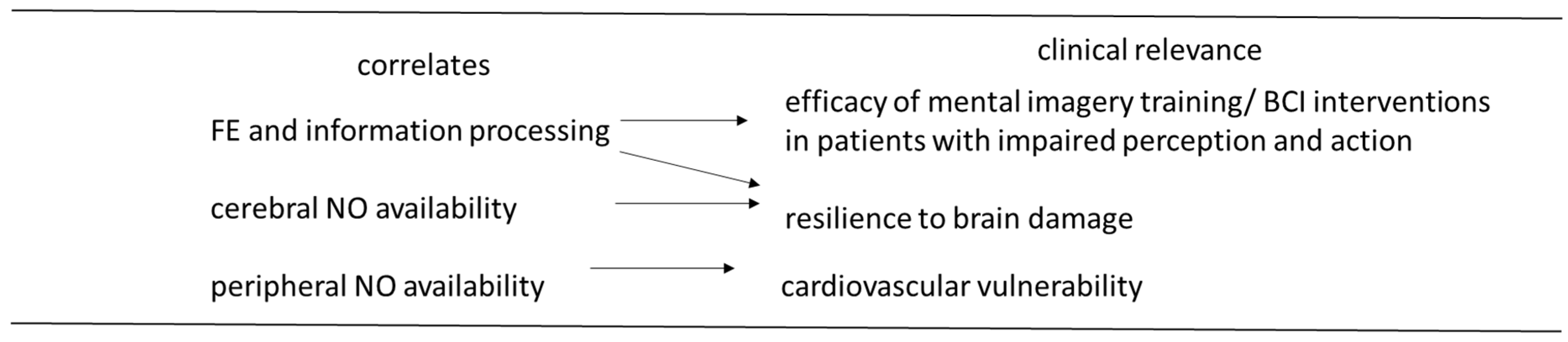

2.1. Cerebral morpho-functional correlates of hypnotizability

2.2. Hypnotizability, brain injuries, mental training

3.1. Peripheral and cerebral blood flow

3.2. Nitric oxide and cardiovascular protection

4. Limitations and Conclusions

References

- Acunzo, D. J., & Terhune, D. B. (2021). A Critical Review of Standardized Measures of Hypnotic Suggestibility. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 69(1), 50–71. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B., Gill, I., Liblik, K., Uppal, J. S., & El-Diasty, M. (2023). The Role of Hypnotherapy in Postoperative Cardiac Surgical Patients, A Scoping Review of Current Literature. Current problems in cardiology, 48(9), 101787. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Bocci, T., Barloscio, D., Parenti, L., Sartucci, F., Carli, G., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2017). High Hypnotizability Impairs the Cerebellar Control of Pain. Cerebellum (London, England), 16(1), 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Callara, A. L., Fontanelli, L., Belcari, I., Rho, G., Greco, A., Zelič, Ž., Sebastiani, L., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2023). Modulation of the heartbeat evoked cortical potential by hypnotizability and hypnosis. Psychophysiology, e14309. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Császár-Nagy, N., & Bókkon, I. (2022). Hypnotherapy and IBS: Implicit, long-term stress memory in the ENS. Heliyon, 9(1), e12751. [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F. I., Cacace, I., Del Testa, M., Andre, P., Carli, G., De Pascalis, V., Rocchi, R., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2010). Hypnotizability-related EEG alpha and theta activities during visual and somesthetic imageries. Neuroscience letters, 470(1), 13–18. [CrossRef]

- Cesari, P., Modenese, M., Benedetti, S., Emadi Andani, M., & Fiorio, M. (2020). Hypnosis-induced modulation of corticospinal excitability during motor imagery. Scientific reports, 10(1), 16882. [CrossRef]

- De Benedittis G. (2022). Hypnobiome: A New, Potential Frontier of Hypnotherapy in the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome-A Narrative Review of the Literature. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 70(3), 286–299. [CrossRef]

- Dell P. F. (2010). Involuntariness in hypnotic responding and dissociative symptoms. Journal of trauma & dissociation : The official journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 11(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, S. W., Whalley, M. G., & Oakley, D. A. (2009). Fibromyalgia pain and its modulation by hypnotic and non-hypnotic suggestion: An fMRI analysis. European journal of pain (London, England), 13(5), 542–550. [CrossRef]

- Elkins G. (2022). From Research to Clinical Practice. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 70(3), 209–211. [CrossRef]

- Escobar Cervantes, C., Esteban Fernández, A., Recio Mayoral, A., Mirabet, S., González Costello, J., Rubio Gracia, J., Núñez Villota, J., González Franco, Á., & Bonilla Palomas, J. L. (2023). Identifying the patient with heart failure to be treated with vericiguat. Current medical research and opinion, 39(5), 661–669. [CrossRef]

- Facco, E., Testoni, I., Ronconi, L., Casiglia, E., Zanette, G., & Spiegel, D. (2017). Psychological Features of Hypnotizability: A First Step Towards Its Empirical Definition. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 65(1), 98–119. [CrossRef]

- Fiorio, M., Modenese, M., & Cesari, P. (2020). The rubber hand illusion in hypnosis provides new insights into the sense of body ownership. Scientific reports, 10(1), 5706. [CrossRef]

- Fontanelli, L., Spina, V., Chisari, C., Siciliano, G., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2022). Is hypnotic assessment relevant to neurology?. Neurological sciences : Official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology, 43(8), 4655–4661. [CrossRef]

- Guillot, A., Di Rienzo, F., Macintyre, T., Moran, A., & Collet, C. (2012). Imagining is Not Doing but Involves Specific Motor Commands: A Review of Experimental Data Related to Motor Inhibition. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 6, 247. [CrossRef]

- Grześk, G., Witczyńska, A., Węglarz, M., Wołowiec, Ł., Nowaczyk, J., Grześk, E., & Nowaczyk, A. (2023). Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase Activators-Promising Therapeutic Option in the Pharmacotherapy of Heart Failure and Pulmonary Hypertension. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 28(2), 861. [CrossRef]

- Han K, Liu J, Tang Z, Su W, Liu Y, Lu H, Zhang H. Effects of excitatory transcranial magnetic stimulation over the different cerebral hemispheres dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for post-stroke cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurosci. 2023 May 16;17:1102311. PMID: 37260845; PMCID: PMC10228699. [CrossRef]

- Henschke, J. U., & Pakan, J. M. P. (2023). Engaging distributed cortical and cerebellar networks through motor execution, observation, and imagery. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 17, 1165307. [CrossRef]

- Hoiland, R. L., Caldwell, H. G., Howe, C. A., Nowak-Flück, D., Stacey, B. S., Bailey, D. M., Paton, J. F. R., Green, D. J., Sekhon, M. S., Macleod, D. B., & Ainslie, P. N. (2020). Nitric oxide is fundamental to neurovascular coupling in humans. The Journal of physiology, 598(21), 4927–4939. [CrossRef]

- Huerta de la Cruz, S., Santiago-Castañeda, C. L., Rodríguez-Palma, E. J., Medina-Terol, G. J., López-Preza, F. I., Rocha, L., Sánchez-López, A., Freeman, K., & Centurión, D. (2022). Targeting hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide to repair cardiovascular injury after trauma. Nitric oxide : Biology and chemistry, 129, 82–101. [CrossRef]

- Hurst, A. J., & Boe, S. G. (2022). Imagining the way forward: A review of contemporary motor imagery theory. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 16, 1033493. [CrossRef]

- Jeannerod, M., & Frak, V. (1999). Mental imaging of motor activity in humans. Current opinion in neurobiology, 9(6), 735–739. [CrossRef]

- Jambrik, Z., Santarcangelo, E. L., Ghelarducci, B., Picano, E., & Sebastiani, L. (2004). Does hypnotizability modulate the stress-related endothelial dysfunction?. Brain research bulletin, 63(3), 213–216. [CrossRef]

- Jambrik, Z., Santarcangelo, E. L., Rudisch, T., Varga, A., Forster, T., & Carli, G. (2005). Modulation of pain-induced endothelial dysfunction by hypnotisability. Pain, 116(3), 181–186. [CrossRef]

- Kirenskaya, A. V., Novototsky-Vlasov, V. Y., Chistyakov, A. N., & Zvonikov, V. M. (2011). The relationship between hypnotizability, internal imagery, and efficiency of neurolinguistic programming. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 59(2), 225–241. [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, I., & Lynn, S. J. (1997). Hypnotic involuntariness and the automaticity of everyday life. The American journal of clinical hypnosis, 40(1), 329–348. [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, I., & Lynn, S. J. (1998). Dissociation theories of hypnosis. Psychological bulletin, 123(1), 100–115. [CrossRef]

- Kishi T. (2013). Regulation of the sympathetic nervous system by nitric oxide and oxidative stress in the rostral ventrolateral medulla: 2012 Academic Conference Award from the Japanese Society of Hypertension. Hypertension research : Official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension, 36(10), 845–851. [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Marcelo, E., Campioni, L., Manzoni, D., Santarcangelo, E. L., & Petri, G. (2019). Spectral and topological analyses of the cortical representation of the head position: Does hypnotizability matter?. Brain and behavior, 9(6), e01277. [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Marcelo, E., Campioni, L., Phinyomark, A., Petri, G., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2019). Topology highlights mesoscopic functional equivalence between imagery and perception: The case of hypnotizability. NeuroImage, 200, 437–449. [CrossRef]

- Landry, M., Lifshitz, M., & Raz, A. (2017). Brain correlates of hypnosis: A systematic review and meta-analytic exploration. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 81(Pt A), 75–98. [CrossRef]

- Laricchiuta, D., Picerni, E., Cutuli, D., & Petrosini, L. (2022). Cerebellum, Embodied Emotions, and Psychological Traits. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 1378, 255–269. [CrossRef]

- Lifshitz, M., Howells, C., & Raz, A. (2012). Can expectation enhance response to suggestion? De-automatization illuminates a conundrum. Consciousness and cognition, 21(2), 1001–1008. [CrossRef]

- Lynn, S. J., & Green, J. P. (2011). The sociocognitive and dissociation theories of hypnosis: Toward a rapprochement. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 59(3), 277–293. [CrossRef]

- Lynn, S. J., Green, J. P., Zahedi, A., & Apelian, C. (2023). The response set theory of hypnosis reconsidered: Toward an integrative model. The American journal of clinical hypnosis, 65(3), 186–210. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, V. U., Seitz, J., Schönfeldt-Lecuona, C., Höse, A., Abler, B., Hole, G., Goebel, R., & Walter, H. (2015). The neural correlates of movement intentions: A pilot study comparing hypnotic and simulated paralysis. Consciousness and cognition, 35, 158–170. [CrossRef]

- Malinski T. (2007). Nitric oxide and nitroxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD, 11(2), 207–218. [CrossRef]

- Mućka, S., Miodońska, M., Jakubiak, G. K., Starzak, M., Cieślar, G., & Stanek, A. (2022). Endothelial Function Assessment by Flow-Mediated Dilation Method: A Valuable Tool in the Evaluation of the Cardiovascular System. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(18), 11242. [CrossRef]

- Parris, B. A., Hasshim, N., & Dienes, Z. (2021). Look into my eyes: Pupillometry reveals that a post-hypnotic suggestion for word blindness reduces Stroop interference by marshalling greater effortful control. The European journal of neuroscience, 53(8), 2819–2834. [CrossRef]

- Peters, B., Eddy, B., Galvin-McLaughlin, D., Betz, G., Oken, B., & Fried-Oken, M. (2022). A systematic review of research on augmentative and alternative communication brain-computer interface systems for individuals with disabilities. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 16, 952380. [CrossRef]

- Piccione, C., Hilgard, E. R., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1989). On the degree of stability of measured hypnotizability over a 25-year period. Journal of personality and social psychology, 56(2), 289–295. [CrossRef]

- Picerni, E., Santarcangelo, E. L., Laricchiuta, D., Cutuli, D., Petrosini, L., Spalletta, G., & Piras, F. (2019). Cerebellar Structural Variations in Participants with Different Hypnotizability. Cerebellum (London, England), 18(1), 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Presciuttini, S., Gialluisi, A., Barbuti, S., Curcio, M., Scatena, F., Carli, G., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2014). Hypnotizability and Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphysms in Italians. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 7, 929. [CrossRef]

- Quarti-Trevano, F., Dell'Oro, R., Cuspidi, C., Ambrosino, P., & Grassi, G. (2023). Endothelial, Vascular and Sympathetic Alterations as Therapeutic Targets in Chronic Heart Failure. Biomedicines, 11(3), 803. [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, V., Chai, Y. L., Poh, L., Selvaraji, S., Fann, D. Y., Jo, D. G., De Silva, T. M., Drummond, G. R., Sobey, C. G., Arumugam, T. V., Chen, C. P., & Lai, M. K. P. (2023). Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion: A critical feature in unravelling the etiology of vascular cognitive impairment. Acta neuropathologica communications, 11(1), 93. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A., Santarcangelo, E. L., & Roatta, S. (2022a). Does hypnotizability affect neurovascular coupling during cognitive tasks?. Physiology & behavior, 257, 113915. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A., Santarcangelo, E. L., & Roatta, S. (2022b). Cerebrovascular reactivity during visual stimulation: Does hypnotizability matter?. Brain research, 1794, 148059. [CrossRef]

- Rosati, A., Belcari, I., Santarcangelo, E. L., & Sebastiani, L. (2021). Interoceptive Accuracy as a Function of Hypnotizability. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 69(4), 441–452. [CrossRef]

- Ruggirello, S., Campioni, L., Piermanni, S., Sebastiani, L., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2019). Does hypnotic assessment predict the functional equivalence between motor imagery and action?. Brain and cognition, 136, 103598. [CrossRef]

- Ruzyla-Smith, P.; Barabasz, A.; Barabasz, M. & Warner, D. Effects of hypnosis on the immune response: B-cells, T-cells, helper and suppressor cells. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 1995; 38: 71-79. [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E. L., & Carli, G. (2021). Individual Traits and Pain Treatment: The Case of Hypnotizability. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 683045. [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E. L., Scattina, E., Carli, G., Ghelarducci, B., Orsini, P., & Manzoni, D. (2010). Can imagery become reality?. Experimental brain research, 206(3), 329–335. [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E. L., & Scattina, E. (2016). Complementing the Latest APA Definition of Hypnosis: Sensory-Motor and Vascular Peculiarities Involved in Hypnotizability. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 64(3), 318–330. [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E. L., Balocchi, R., Scattina, E., Manzoni, D., Bruschini, L., Ghelarducci, B., & Varanini, M. (2008). Hypnotizability-dependent modulation of the changes in heart rate control induced by upright stance. Brain research bulletin, 75(5), 692–697. [CrossRef]

- Santarcangelo, E. L., Paoletti, G., Balocchi, R., Carli, G., Morizzo, C., Palombo, C., & Varanini, M. (2012). Hypnotizability modulates the cardiovascular correlates of participantive relaxation. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis, 60(4), 383–396. [CrossRef]

- Scacchia, P., & De Pascalis, V. (2020). Effects of Prehypnotic Instructions on Hypnotizability and Relationships Between Hypnotizability, Absorption, and Empathy. The American journal of clinical hypnosis, 62(3), 231–266. [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, L., D'Alessandro, L., Menicucci, D., Ghelarducci, B., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2007). Role of relaxation and specific suggestions in hypnotic emotional numbing. International journal of psychophysiology : 63(1), 125–132. [CrossRef]

- Spina, V., Chisari, C., & Santarcangelo, E. L. (2020). High Motor Cortex Excitability in Highly Hypnotizable Individuals: A Favourable Factor for Neuroplasticity?. Neuroscience, 430, 125–130. [CrossRef]

- Srzich, A. J., Byblow, W. D., Stinear, J. W., Cirillo, J., & Anson, J. G. (2016). Can motor imagery and hypnotic susceptibility explain Conversion Disorder with motor symptoms?. Neuropsychologia, 89, 287–298. [CrossRef]

- Terhune DB, Cardeña E, Lindgren M. Dissociated control as a signature of typological variability in high hypnotic suggestibility. Conscious Cogn. 2011;20(3):727-36. [CrossRef]

- Terreni, C. Efficacia di un training immaginativo sul movimento: Studio sperimentale. Master thesis, Pisa University, 2023.

- Uemura, M. T., Maki, T., Ihara, M., Lee, V. M. Y., & Trojanowski, J. Q. (2020). Brain Microvascular Pericytes in Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 12, 80. [CrossRef]

- Weber, C., Dilthey, A., & Finzer, P. (2023). The role of microbiome-host interactions in the development of Alzheimer´s disease. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 13, 1151021. [CrossRef]

- Wieder, L., Brown, R., Thompson, T., & Terhune, D. B. (2021). Suggestibility in functional neurological disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 92(2), 150–157. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T. G., Faerber, K. A., Rummel, C., Halsband, U., & Campus, G. (2022). Functional Changes in Brain Activity Using Hypnosis: A Systematic Review. Brain sciences, 12(1), 108. [CrossRef]

- Yao, W. X., Ge, S., Zhang, J. Q., Hemmat, P., Jiang, B. Y., Liu, X. J., Lu, X., Yaghi, Z., & Yue, G. H. (2023). Bilateral transfer of motor performance as a function of motor imagery training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1187175. [CrossRef]

- Zambach, S.A.; Cai, C.; Helms, H.C.C.; Hald, B.O.; Dong, Y.; Fordsmann, J.C.; Nielsen, R.M.; Hu, J.; Lønstrup, M.; Brodin, B.; et al. Precapillary sphincters and pericytes at first-order capillaries as key regulators for brain capillary perfusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023749118. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J., Wang, L., Cai, Q., Wu, J., & Zhou, C. (2022). Effect of hypnosis before general anesthesia on postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing minor surgery for breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gland surgery, 11(3), 588–598. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).