Submitted:

24 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

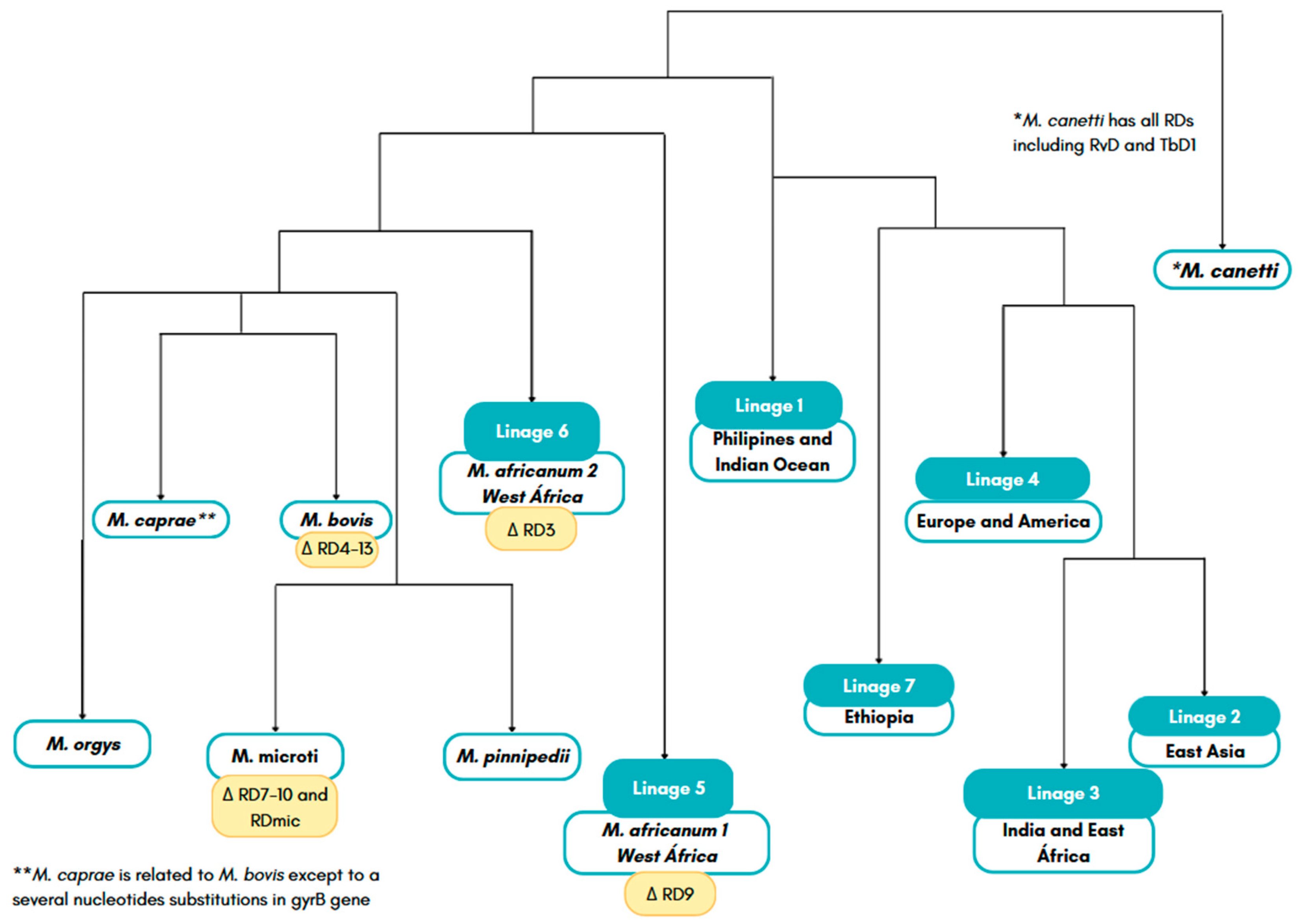

2. Mycobacteria and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An Interesting Genus

3. Mycobacteria and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An Interesting Genus

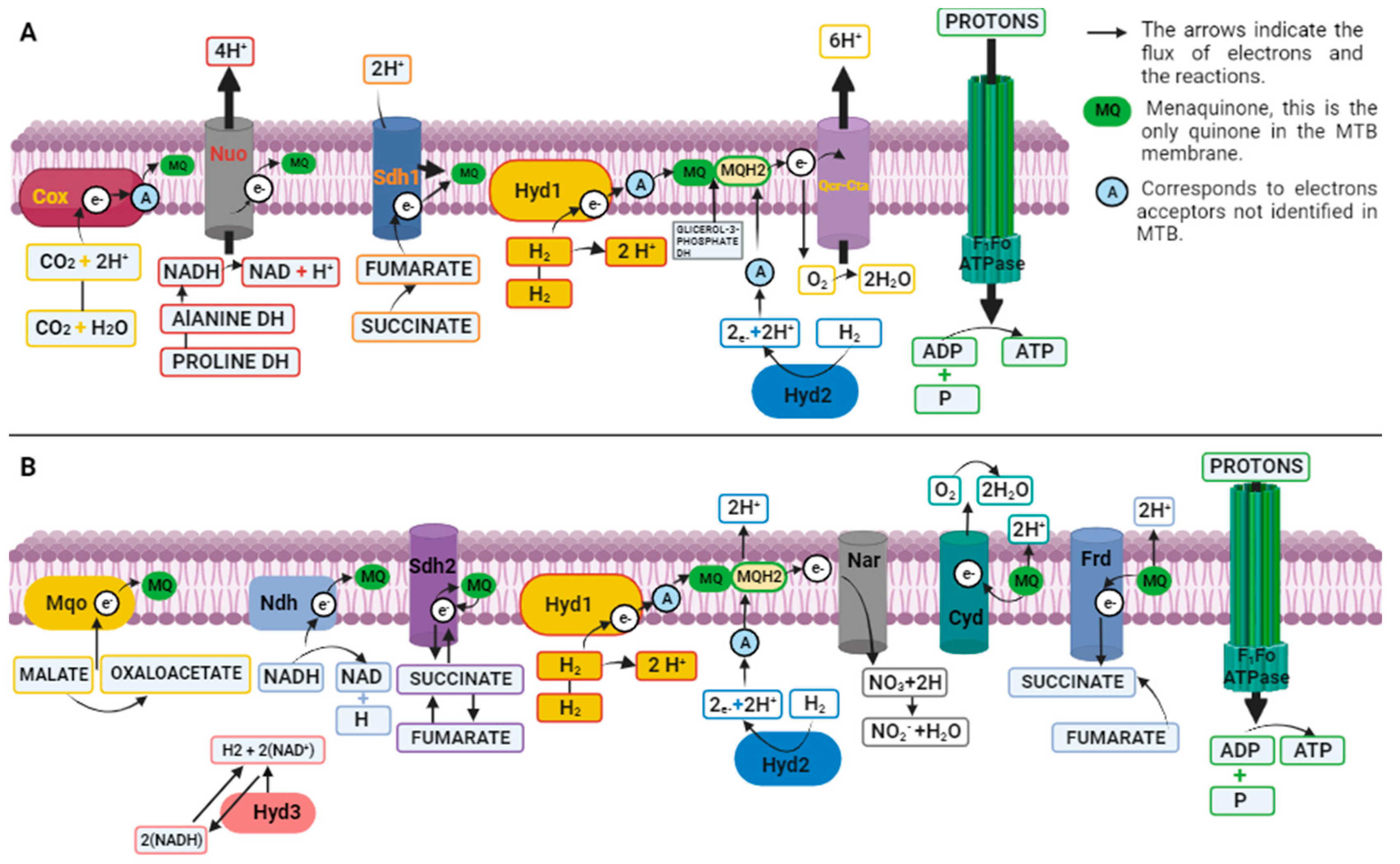

4. A Complex Metabolism for Survive and Infect

| Nutrient/ Metabolism |

Gene | Compound | Keeg Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium/ Nitrogen |

Rv1737c, Rrv2329c, Rv0261c, Rv0267, Rv1161, Rv1736c, Rv1162, Rv1164, Rv0252, Rv0253, Rv0021c, Rv2781c, Rv2476c, Rv2220, Rv2222c, Rv2860c, Rv1878, Rv3859c, Rv3858c, Rv3588c, Rv1284 and Rv3273 |

C00011, C00014, C00025, C00058, C00064, C00088, C00169, C00192, C00244, C00288, C00488, C00533, C00697, C00726, C00887, C01417, C01563, C05361 and C06058 | Mtu00910 |

| Glucose Carbohydrate/ Carbon and energy |

Rv0650, Rv0946c, Rv2029c, Rv3010c, Rv1099c, Rv0363c, Rv1438, Rv1436, Rv1437, Rv0489, Rv1023, Rv1617, Rv1127c, Rv2241, Rv2215, Rv0462, Rv2455c, Rv2454c, Rv0761c, Rv1862, Rv0162c, Rv1530, Rv3045, Rv0768, Rv0147, Rv0223c, Rv0458, Rv3667, Rv3068c, Rv2702 and Rv0211 |

C00022, C00024, C00031, C00033, C00036, C00068, C00074, C00084, C00103, C00111, C00118, C00186, C00197, C00221, C00236, C00267, C00469, C00631, C00668, C01159, C01172, C01451, C05125, C05345, C05378, C06186, C06187, C06188, C15972, C15973 and C16255 | Mtu00010 |

| Within the macrophage MTB increases the expression of isocitrate lyase, which acts in the transformation of acetyl-CoA into carbohydrates through gluconeogenesis |

Rv0889c, Rv0896, Rv1131, Rv1475c, Rv0066c, Rv3339c, Rv1248c, Rv0462, Rv2455c, Rv2454c, Rv0952, Rv0951, Rv3318, Rv0248c, Rv3319, Rv0247c, Rv3316, Rv3317, Rv1552, Rv1553, Rv1554, Rv1555, Rv1098c, Rv1240, Rv2852c, Rv2967c, Rv0211, Rv2241 and Rv2215 | C00022, C00024, C00026, C00036, C00042, C00068, C00074, C00091, C00122, C00149, C00158, C00311, C00417, C05125, C05379, C05381, C15972, C15973, C16254 and C16255 | Mtu00020 |

| Phosphate/ Energy source or phospholipid biosynthesis |

Rv0946c, Rv1121, Rv1447c, Rv1445c, Rv1122, Rv1844c, Rv1408, Rv1449c, Rv1448c, Rv2465c, Rv0478, Rv2436, Rv3068c, Rv1017c, Rv0363c, Rv1099c, Rv2029c, and Rv3010c |

C00022, C00031, C00117, C00118, C00119, C00121, C00197, C00198, C00199, C00204, C00221, C00231, C00257, C00258, C00279, C00345, C00577, C00620, C00631, C00668, 00672, C00673, C01151, C01172, C01182, C01218, C01236, C01801, C03752, C04442, C05345, C05378, C05382, C06019, C06473 and C20589. | Mtu00030 |

| Sulfur/ It is important for the initial process of protein synthesis and for maintaining a redox environment |

Rv2400c, Rv2399c, Rv2398c, Rv2397c, Rv1286, Rv1285, Rv2131c, Rv2837c, Rv2392, Rv2391, Rv0331, Rv0815c, Rv2291, Rv3117, Rv3283, Rv2335, Rv2334, Rv3684, Rv3341, Rv1079, Rv0391 and Rv3238c |

C00033, C00042, C00053, C00054, C00059, C00065, C00084, C00087, C00094, C00097, C00155, C00224, C00245, C00263, C00283, C00320, C00409, C00580, C00979, C01118, C01861, C02084, C03920, C04022, C08276, C11142, C11143, C11145, C15521, C17267, C19692, C20870 and C20955 |

Mtu00920 |

| Biotin/ Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins/ Necessary for lipid biosynthesis and gluconeogenesis |

Rv1350, Rv0242c, Rv3559c, Rv0769, Rv0032, Rv1569, Rv1568, Rv1570, Rv1589, Rv3279c and Rv1442 |

C01209, C01894, C01909, C02656, C05552, C05921, C06250, C19673, C19845, C19846, C20372, C20373, C20374, C20375, C20376, C20377, C20378, C20384, C20385, C20386, C20387, C20683 and C22458 | Mtu00780 |

| Colesterol/ Lipid Synthesis of virulence- related lipids. Providing latent infection survival products |

Rv0764c |

C00187, C00448, C00751, C01054, C01164, C01189, C01561, C01673, C01694, C01724, C01753, C01789, C01802, C01902, C01943, C02141, C02530, C03428, C03845, C04525, C05103, C05107, C05108, C05109, C05437, C05439, C05440, C05441, C05442, C05443, C07712, C08813, C08821, C08830, C11455, C11508, C11522, C11523, C15776, C15777, C15780, C15781, C15782, C15783, C15808, C15816, C15915, C18231, C21106, C22112, C22116, C22119, C22120, C22121, C22122, C22123 and C22136. | Mtu00100 |

5. Transport Substrates Across the Membrane: The Set Transporters from MTB

6. Who Are MTB? The Genes Answer the Question

| Gene | Function | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Rv2940 | Promotes the synthesis of long chain fatty acids | Cell Wall |

| Rv2930 | Acyl-coenzyme A, promotes the degradation of fatty acids | |

| Rv2941 | Fatty-acid-CoA synthetase that acts in the lipidic pathway |

|

| Rv2942 | Promotes the transport of lipids and synthesis of the mycomembrane | |

| Rv3804c | Promotes the transfer of mycolic acids to trehalose |

|

| Rv0642c and Rv0410 | A methyltransferase bound to the synthesis of mycolic acids | Cell Wall |

| Rv0899 | It is a protein expressed at low pH | |

| Rv0475 | It is a heparin-binding hemagglutinin protein | |

|

RD1 region |

Inhibition of phagosome maturation and apoptosis. Responsible for encoding a network of secretion systems |

|

|

Rv2246 |

It is a culture filtrate protein whose function is a chaperonin linked to latency and persistence | |

| Rv3763 | It is a culture filtration protein that promotes the regulation of IL-12 | |

|

Rv1811 |

Acts on magnesium uptake |

|

|

Rv3083 to Rv3089, and Rv2869c |

MTB related to mycolic acid synthesis is mymA operon |

|

|

Rv2946C, Rv1660, Rv2048c, Rv2941, Rv2938, 1527c, Rv1661, Rv3823c, Rv1345 and Rv1916 |

Linked to complex lipid synthesis | |

| Rv1411c, Rv1410c, Rv0934, Rv1235 and Rv1857 | Lipoproteins that constitute virulence factors |

|

| Rv3682 | Transglucosylases and transpeptidase | |

| Rv2136 | Involved in the synthesis of peptidoglycan |

|

| Rv0198c and Rv2869c | Metallo-proteases | |

| Rv2097c and Rv2115c | Proteasome associated proteins |

|

| Rv2382c, Rv1348, Rv1349, Rv2711 and Rv1811 | Related to metal transporter | Cell Wall |

| Rv3270 | Zinc efflux | |

| Rv0969 | Cupper efflux | |

|

Rv3367, Rv1818c and Rv2136c |

Rv3367, Rv1818c and Rv2136c |

|

|

MT18B_4990, Rv1411c, Rv1270c and Rv0934 |

Lipoproteins that are Toll Like Receptor-2 (TLR2) agonists and their Myeloid Differentiation Primary-Response protein 88 (MYD88) |

|

|

Rv0350, Rv1860, MT18B_4990 and Rv1436 |

Allow the bacillus to bind to cells, either phagocytosed and continue to replicate |

Intermediary metabolism and respiration |

|

Rv2220 |

A glutamine synthetase, also constitutes a culture filtration protein, acts on the metabolism of nitrogen |

|

| Rv0467 | Isocytrase lyase, converts isocitrate to succinate and allows bacterial growth under fatty acids and acetate | |

| Rv3487 | It is a lipase esterase that acts on lipid degradation |

|

| Rv1345 | Acts on β- oxidation of fatty acids | |

|

Rv2351c, Rv2350c, Rv2349c and Rv1755c |

Phospholipases involved in the cycles of obtaining energy |

|

|

Rv3602c and Rv3601 |

Consist of pantothenate synthase proteins, this molecule that acts on the degradation of lipids and other cell signaling |

|

| Rv2987, Rv2192, Rv0500 and Rv0780 | Act on the biosynthesis of leucine, tryptophan, proline and purines respectively | |

|

Rv1161 |

Involved with respiration under anaerobic conditions and the conversion of nitrate to nitrite |

Intermediary metabolism and respiration |

|

Rv0475, Rv0930, Rv0820, Rv2224c, Rv3236c, (Rv3666c to Rv3663c) and Rv2200c |

Linked to cell wall | |

| Rv3883c | Proteases involved with virulence | |

| Rv0983 and Rv3671c | Serine proteases | |

| Rv3810 | Act with multiplication and intracellular growth | |

| Rv3671c | Encodes a membrane protein responsible for MTB resistance to the acidic environment of IFN-γ-activated phagosomes | |

|

Rv0195, Rv0386, Rv0491, Rv0890c, Rv0894, Rv3416, Rv3133c, Rv1013, Rv2946c, Rv2488c and Rv3133c |

Formation of biofilms. This structure is involved in bacterial persistence and protects it from chemical and physical agents |

Regulator Proteins |

|

Rv2711 |

Binds to regions of genes involved in iron uptake and nitrate reductase |

|

| Rv0757 | Controls the expression of virulence genes by magnesium deficiency | |

| Rv0903c | Regulates macrophage virulence genes | |

| Rv0981 | Two-component system that regulates macrophage virulence genes | |

|

Rv3416 |

Cytoplasmic redox sensor, linked to pH resistance |

|

| Rv0931c and Rv0410c | Proteins kinases related to virulence | Regulator Proteins |

| Rv2745c | ATP-dependent protease | |

|

Rv1908c |

Catalase: peroxidase that degrades peroxides and other organic peroxides |

Virulence, detoxification, adaptation |

| Rv2428 | Protein whose function is to detoxify hydroperoxides |

|

| Rv3846 and Rv0342 | Act in the detoxification of superoxide | |

| Rv0432 | Superoxide dismutase | |

| Rv1936 to Rv1941 and Rv1908c | Catalase-peroxidase protein |

|

| Rv1932 | Thiol peroxidase | |

| Rv0353 | gene repressor of proteins of heat shock |

|

| Rv0251c | Possibly a molecular chaperone | |

| Rv3409c, Rv3568, Rv34545c, Rv3544c, Rv3543c, Rv3542c, Rv3541c and Rv3540c | Linked to catabolism of cholesterol | Lipid metabolism |

| Rv2383c | Linked to production mycobactin, an important siderophore in MTB |

|

| Rv2246 | protein involved in lipid and fatty acid metabolism |

|

| Rv3151, Rv1743, Rv3654c and Rv3655c | Involved with the inhibition of apoptosis |

Conserved hypotheticals |

| Rv2027c, Rv0490, Rv0981, Rv0982, Rv2395A and Rv2395B | Regulatory proteins | |

| Rv2032, Rv0211, Rv0153c and Rv0990c | Virulence factors are found the region of difference RD2 | Conserved hypotheticals |

| Rv2445c, Rv2234 and Rv1651c | Involved in phagosome arresting | PE/PPE |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization, (WHO) WHO Report on TB 2020; 2020; Vol. 1; ISBN 9783642253874.

- World Health Organization WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis.; 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-155051-2.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud Global Tuberculosis Report 2019 OMS - WHO. World Health Organization 2019.

- Zhang, Q. ao; Ma, S.; Li, P.; Xie, J. The Dynamics of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Phagosome and the Fate of Infection. Cell Signal 2023, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ai, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, F. Review and Updates on the Diagnosis of Tuberculosis. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, A.; Beena, P.M.; Devnikar, A. V.; Mali, S. A Systemic Review on Tuberculosis. Indian Journal of Tuberculosis 2020, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhaouane, I.; Pochet, A.; Chatagnon, J.; Hoffmann, E.; Queval, C.J.; Deboosère, N.; Boidin-Wichlacz, C.; Majlessi, L.; Sencio, V.; Heumel, S.; et al. Tirap Controls Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Phagosomal Acidification. PLoS Pathog 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverría-Valencia, G. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis : A Narrative of the Uptaking and Survival. IntechOpen 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pethe, K.; Swenson, D.L.; Alonso, S.; Anderson, J.; Wang, C.; Russell, D.G. Isolation of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Mutants Defective in the Arrest of Phagosome Maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 13642–13647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, M.; Behr, M.A.; Dowdy, D.; Dheda, K.; Divangahi, M.; Boehme, C.C.; Ginsberg, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Spigelman, M.; Getahun, H.; et al. Tuberculosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.K.; Kwon, Y.S. Respiratory Review of 2014: Tuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman-Adams, H.; Clark, K.; Juckett, G. Update on Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Am Fam Physician 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, E.E.; Kinnear, C.; Orlova, M.; Fischinger, S.; Shin, S.; Boolay, S.; Walzl, G.; Jacobs, A.; Wilkinson, R.; Alter, G.; et al. A Case-Control Study Identifying Highly Tuberculosis-Exposed, HIV-1-Infected but Persistently TB, Tuberculin and IGRA Negative Persons with M. Tuberculosis Specific Antibodies in Cape Town, South Africa. medRxiv 2020, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO The End TB Strategy. J Chem Inf Model 2013, 53, 1689–1699.

- Van Soolingen, D.; Hoogenboezem, T.; De Haas, P.E.W.; Hermans, P.W.M.; Koedam, M.A.; Teppema, K.S.; Brennan, P.J.; Besra, G.S.; Portaels, F.; Top, J.; et al. A Novel Pathogenic Taxon of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex, Canetti: Characterization of an Exceptional Isolate from Africa. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997, 47, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgeur, M.; Brosch, R. Evolution of Virulence in the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex. Curr Opin Microbiol 2018, 41, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.T. Comparative and Functional Genomics of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex. Microbiology (N Y) 2015, 1851, 11–2919. [Google Scholar]

- Žmak, L.; Janković, M.; Obrovac, M.; Katalinić-Janković, V. Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria. Infektoloski Glasnik 2013, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M. Cutaneous Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Infections: An Update. Journal of Skin and Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2023, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, V.M. Infections Due to Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM). Indian Journal of Medical Research 2004, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla, G.S.; Sarao, M.S.; Kalra, D.; Bandyopadhyay, K.; John, A.R. Methods of Phenotypic Identification of Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria. Pract Lab Med 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, C.A.M.; Gomes, H.M.; Oelemann, M.A.C.; Ramos, J.P.; Caldas, P.C.; Campos, C.E.D.; Pereira, M.A. da S.; Montes, F.F.O.; de Oliveira, M. do S.C.; Suffys, P.N.; et al. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Respiratory Samples from Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in the State of Rondônia, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2013, 108, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refaya, A.K.; Kumar, N.; Raj, D.; Veerasamy, M.; Balaji, S.; Shanmugam, S.; Rajendran, A.; Tripathy, S.P.; Swaminathan, S.; Peacock, S.J.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing of a Mycobacterium Orygis Strain Isolated from Cattle in Chennai, India. Microbiol Resour Announc 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimpel, C.K.; Brandão, P.E.; de Souza Filho, A.F.; de Souza, R.F.; Ikuta, C.Y.; Neto, J.S.F.; Soler Camargo, N.C.; Heinemann, M.B.; Guimarães, A.M.S. Complete Genome Sequencing of Mycobacterium Bovis SP38 and Comparative Genomics of Mycobacterium Bovis and M. Tuberculosis Strains. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostowy, S.; Onipede, A.; Gagneux, S.; Niemann, S.; Kremer, K.; Desmond, E.; Kato-Maeda, M.; Behr, M. Genomic Analysis Distinguishes Mycobacterium Africanum. J Clin Microbiol 2004, 42, 3594–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudey, K.; Gutierrez, M.; Vincent, V.; Parsons, L.; Salfinger, M.; Rastogi, N.; Sola, C. Mycobacterium Africanum Genotyping UsingNovel Spacer Oligonucleotides in the Direct RepeatLocus. J Clin Microbiol 2004, 42, 5053–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Bannantine, J.P.; Zhang, Q.; Amonsin, A.; May, B.J.; Alt, D.; Banerji, N.; Kanjilal, S.; Kapur, V. The Complete Genome Sequence of Mycobacterium Avium Subspecies Paratuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 12344–12349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-W.; Schmoller, S.K.; Bannantine, J.P.; Eckstein, T.M.; Inamine, J.M.; Livesey, M.; Albrecht, R.; Talaat, A.M. A Novel Cell Wall Lipopeptide Is Important for Biofilm Formation and Pathogenicity of Mycobacterium Avium Subspecies Paratuberculosis. Microb Pathog 2009, 46, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugino, K.; Ono, H.; Ando, M.; Tsuboi, E. Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis in Mycobacterium Avium Complex Lung Disease. Respirol Case Rep 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urabe, N.; Sakamoto, S.; Masuoka, M.; Kato, C.; Yamaguchi, A.; Tokita, N.; Homma, S.; Kishi, K. Efficacy of Three Sputum Specimens for the Diagnosis of Mycobacterium Avium Complex Pulmonary Disease. BMC Pulm Med 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, C.; McCrary, M.; Hou, R.; Abate, G. Diagnosis and Management of Pulmonary NTM with a Focus on Mycobacterium Avium Complex and Mycobacterium Abscessus: Challenges and Prospects. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comincini, S.; Barbarini, D.; Telecco, S.; Bono, L.; Marone, P. Rapid Identification of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Mycobacterium Avium by Polymerase Chain Reaction and Restriction Enzyme Analysis within Sigma Factor Regions. New Microbiologica 1998, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Nqwata, L.; Ouédrago, A.R. Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria Pulmonary Disease: A Review of Trends, Risk Factors, Diagnosis and Management. African Journal of Thoracic and Critical Care Medicine 2022, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Ayerakwa, E.A.; Abban, M.K.; Isawumi, A.; Mosi, L. Profiling Mycobacterium Ulcerans: Sporulation, Survival Strategy and Response to Environmental Factors. Future Sci OA 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchan, B.G.O.; Ngazoa-Kakou, S.; Aka, N.; Apia, N.K.B.; Hammoudi, N.; Drancourt, M.; Saad, J. PPE Barcoding Identifies Biclonal Mycobacterium Ulcerans Buruli Ulcer, Côte d’Ivoire. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimori, T.; Hagiya, H.; Iio, K.; Yamasaki, O.; Miyamoto, Y.; Hoshino, Y.; Kakehi, A.; Okura, M.; Minabe, H.; Yokoyama, Y.; et al. Buruli Ulcer Caused by Mycobacterium Ulcerans Subsp. Shinshuense: A Case Report. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweedale, B.; Collier, F.; Waidyatillake, N.T.; Athan, E.; O’Brien, D.P. Mycobacterium Ulcerans Culture Results According to Duration of Prior Antibiotic Treatment: A Cohort Study. PLoS One 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, M.D.; Herrmann, J.L.; Kremer, L. Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria and the Rise of Mycobacterium Abscessus. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020, 18, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, J.E.; Koh, W.J.; Yew, W.W. Update on Pulmonary Disease Due to Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2016, 45, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammarchi, L.; Tortoli, E.; Borroni, E.; Bartalesi, F.; Strohmeyer, M.; Baretti, S.; Simonetti, M.T.; Liendo, C.; Santini, M.G.; Rossolini, G.M.; et al. High Prevalence of Clustered Tuberculosis Cases in Peruvian Migrants in Florence, Italy. Infect Dis Rep 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Váradi, O.A.; Rakk, D.; Spekker, O.; Terhes, G.; Urbán, E.; Berthon, W.; Pap, I.; Szikossy, I.; Maixner, F.; Zink, A.; et al. Verification of Tuberculosis Infection among Vác Mummies (18th Century CE, Hungary) Based on Lipid Biomarker Profiling with a New HPLC-HESI-MS Approach. Tuberculosis 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalremruata, A.; Ball, M.; Bianucci, R.; Welte, B.; Nerlich, A.G.; Kun, J.F.J.; Pusch, C.M. Molecular Identification of Falciparum Malaria and Human Tuberculosis Co-Infections in Mummies from the Fayum Depression (Lower Egypt). PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmak, L.; Obrovac, M.; Makek, M.J.; Perko, G.; Trkanjec, J.T. From Peruvian Mummies to Living Humans: First Case of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Caused by Mycobacterium Pinnipedii. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, A.R.; Sola, C.; Reischl, U.; Grabner, W.; Rastogi, N.; Wolf, H.; Nerlich, A.G. Characterization of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex DNAs from Egyptian Mummies by Spoligotyping. J Clin Microbiol 2003, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basta, P.C.; Camacho, L.A.B. Tuberculin Skin Test to Estimate the Prevalence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection in Indigenous Populations in the Americas: A Literature Review. Cad Saude Publica 2006, 22, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderVen, B.; Huang, L.; Rohde, K.; Russell, D. The Minimal Unit of Infection: Mycobacterium Tuberculosis in the Macrophage. Microbiol Spectr 2016, 4 6, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, J.; Gao, G.F.; Liu, C.H. Insights into Battles between Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Macrophages. Protein Cell 2014, 5, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, F.; Jackson, M.; Ma, Y.; McNeil, M. Cell Wall Core Galactofuran Synthesis Is Essential for Growth of Mycobacteria. J Bacteriol 2001, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Delgado, Y.M.; Rodríguez-Carlos, A.; Serrano, C.J.; Rivas-Santiago, B. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Cell-Wall and Antimicrobial Peptides: A Mission Impossible? Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Leis, A.; Niederweis, M.; Plitzko, J.M.; Engelhardt, H. Disclosure of the Mycobacterial Outer Membrane: Cryo-Electron Tomography and Vitreous Sections Reveal the Lipid Bilayer Structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 3963–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.C.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Wen, B.; Gitai, Z.; Wingreen, N.S. Cell Shape and Cell-Wall Organization in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, C.; Engelhardt, H.; Niederweis, M. The Core of the Tetrameric Mycobacterial Porin MspA Is an Extremely Stable β-Sheet Domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoud, M.; Sukumaran, S.; Hülsmann, P.; Grieger, K.; Niederweis, M. Topology of the Porin MspA in the Outer Membrane of Mycobacterium Smegmatis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, C.; Kubetzko, S.; Kaps, I.; Seeber, S.; Engelhardt, H.; Niederweis, M. MspA Provides the Main Hydrophilic Pathway through the Cell Wall of Mycobacterium Smegmatis. Mol Microbiol 2001, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlenok, M.; Niederweis, M. Hetero-Oligomeric MspA Pores in Mycobacterium Smegmatis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2016, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, D.; Eschenbacher, I.; Thiel, A.; Niederweis, M. Expression of the Major Porin Gene MspA Is Regulated in Mycobacterium Smegmatis. J Bacteriol 2007, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharbati-Tehrani, S.; Meister, B.; Appel, B.; Lewin, A. The Porin MspA from Mycobacterium Smegmatis Improves Growth of Mycobacterium Bovis BCG. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2004, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huff, J.; Pavlenok, M.; Sukumaran, S.; Niederweis, M. Functions of the Periplasmic Loop of the Porin MspA from Mycobacterium Smegmatis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitra, A.; Munshi, T.; Healy, J.; Martin, L.T.; Vollmer, W.; Keep, N.H.; Bhakta, S. Cell Wall Peptidoglycan in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: An Achilles’ Heel for the TB-Causing Pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2019, 43, 548–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Matsuo, Y.; Pradipta, A.R.; Inohara, N.; Fujimoto, Y.; Fukase, K. Synthesis of Characteristic Mycobacterium Peptidoglycan (PGN) Fragments Utilizing with Chemoenzymatic Preparation of Meso-Diaminopimelic Acid (DAP), and Their Modulation of Innate Immune Responses. Org Biomol Chem 2016, 14, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, A.M.; Namugenyi, S.B.; Palani, N.P.; Brokaw, A.M.; Zhang, L.; Beckman, K.B.; Tischler, A.D. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Requires the Outer Membrane Lipid Phthiocerol Dimycocerosate for Starvation-Induced Antibiotic Tolerance. mSystems 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babajan, B.; Chaitanya, M.; Rajsekhar, C.; Gowsia, D.; Madhusudhana, P.; Naveen, M.; Chitta, S.K.; Anuradha, C.M. Comprehensive Structural and Functional Characterization of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis UDP-NAG Enolpyruvyl Transferase (Mtb-MurA) and Prediction of Its Accurate Binding Affinities with Inhibitors. Interdiscip Sci 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, Y.; Ahmad, I.; Surana, S.; Patel, H. The Mur Enzymes Chink in the Armour of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Cell Wall. Eur J Med Chem 2021, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Kumar, V.; Naik, B.; Masood Khan, J.; Singh, P.; Erik Joakim Saris, P.; Gupta, S. Screening and Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Compounds Inhibiting MurB Enzyme of Drug-Resistant Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: An in-Silico Approach. Saudi J Biol Sci 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eniyan, K.; Rani, J.; Ramachandran, S.; Bhat, R.; Khan, I.A.; Bajpai, U. Screening of Antitubercular Compound Library Identifies Inhibitors of Mur Enzymes in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. SLAS Discovery 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, N. de O.; Silva, C.; Dias, M.V.B. The Crystal Structure of Mycobacterium Thermoresistibile MurE Ligase Reveals the Binding Mode of the Substrate M-Diaminopimelate. J Struct Biol 2023, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.; Singh, N.; Kumar, R.; Kushwaha, N.K.; Prajapati, V.M.; Singh, S.K. GlfT1 Down-Regulation Affects Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Biofilm Formation and Its in-Vitro and in-Vivo Survival. Tuberculosis 2023, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderwick, L.J.; Dover, L.G.; Veerapen, N.; Gurcha, S.S.; Kremer, L.; Roper, D.L.; Pathak, A.K.; Reynolds, R.C.; Besra, G.S. Expression, Purification and Characterisation of Soluble GlfT and the Identification of a Novel Galactofuranosyltransferase Rv3782 Involved in Priming GlfT-Mediated Galactan Polymerisation in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Protein Expr Purif 2008, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu Sait, M.R.; Koliwer-Brandl, H.; Stewart, J.A.; Swarts, B.M.; Jacobsen, M.; Ioerger, T.R.; Kalscheuer, R. PPE51 Mediates Uptake of Trehalose across the Mycomembrane of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaradia, L.; Lefebvre, C.; Parra, J.; Marcoux, J.; Burlet-Schiltz, O.; Etienne, G.; Tropis, M.; Daffé, M. Dissecting the Mycobacterial Cell Envelope and Defining the Composition of the Native Mycomembrane. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewicz, A.E.; Eynard, N.; Quémard, A.; North, E.J.; Margolis, A.; Lindenberger, J.J.; Jones, V.; Korduláková, J.; Brennan, P.J.; Lee, R.E.; et al. Covalent Modification of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis FAS-II Dehydratase by Isoxyl and Thiacetazone. ACS Infect Dis 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewicz, A.E.; Lelièvre, J.; Esquivias, J.; Angala, B.; Liu, J.; Lee, R.E.; McNeil, M.R.; Jackson, M. Lack of Specificity of Phenotypic Screens for Inhibitors of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis FAS-II System. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantaloube, S.; Veyron-Churlet, R.; Haddache, N.; Daffé, M.; Zerbib, D. The Mycobacterium Tuberculosis FAS-II Dehydratases and Methyltransferases Define the Specificity of the Mycolic Acid Elongation Complexes. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.J.; Dechow, S.J.; Abramovitch, R. Acid Fasting: Modulation of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Metabolism at Acidic PH. Trends Microbiol 2019, null, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moolla, N.; Bailo, R.; Marshall, R.; Bavro, V.N.; Bhatt, A. Structure-Function Analysis of MmpL7-Mediated Lipid Transport in Mycobacteria. The Cell Surface 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K.; Nakata, N.; Mukai, T.; Kawagishi, I.; Ato, M. Coexpression of MmpS5 and MmpL5 Contributes to Both Efflux Transporter MmpL5 Trimerization and Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Huang, Y.; Xie, F.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Stojkoska, A.; Xie, J. Transport Mechanism of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis MmpL/S Family Proteins and Implications in Pharmaceutical Targeting. Biol Chem 2020, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.T.; Abramovitch, R.B. Molecular Mechanisms of MmpL3 Function and Inhibition. Microbial Drug Resistance 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.; Garcia, R.; Bach, H.; de Waard, J.H.; Jacobs, W.R.; Av-Gay, Y.; Bubis, J.; Takiff, H.E. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Transporter MmpL7 Is a Potential Substrate for Kinase PknD. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, O.; Deme, J.C.; Parker, J.L.; Fowler, P.W.; Lea, S.M.; Newstead, S. Cryo-EM Structure and Resistance Landscape of M. Tuberculosis MmpL3: An Emergent Therapeutic Target. Structure 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Obregón-Henao, A.; Wallach, J.B.; North, E.J.; Lee, R.E.; Gonzalez-Juarrero, M.; Schnappinger, D.; Jackson, M. Therapeutic Potential of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Mycolic Acid Transporter, MmpL3. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chim, N.; Torres, R.; Liu, Y.; Capri, J.; Batot, G.; Whitelegge, J.P.; Goulding, C.W. The Structure and Interactions of Periplasmic Domains of Crucial MmpL Membrane Proteins from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Chem Biol 2015, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, N.J.; Heran Darwin, K. The Pup-Proteasome System of Mycobacteria. Microbiology spectrum 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanovic, M.I.; Li, H.; Darwin, K.H. The Pup-Proteasome System of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Subcell Biochem 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.H.; Jastrab, J.B.; Dhabaria, A.; Chaton, C.T.; Rush, J.S.; Korotkov, K. V.; Ueberheide, B.; Heran Darwin, K. The Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Pup-Proteasome System Regulates Nitrate Metabolism through an Essential Protein Quality Control Pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barandun, J.; Delley, C.L.; Weber-Ban, E. The Pupylation Pathway and Its Role in Mycobacteria. BMC Biol 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Striebel, F.; Imkamp, F.; Özcelik, D.; Weber-Ban, E. Pupylation as a Signal for Proteasomal Degradation in Bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2014, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, G. V.; Zhang, S.; Merkx, R.; Schiesswohl, C.; Chatterjee, C.; Darwin, K.H.; Geurink, P.P.; van der Heden van Noort, G.J.; Ovaa, H. Development of Tyrphostin Analogues to Study Inhibition of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Pup Proteasome System**. ChemBioChem 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.A.; Rajeswari, H.S.; Veeraraghavan, U.; Ajitkumar, P. Molecular Characterisation of ABC Transporter Type FtsE and FtsX Proteins of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Arch Microbiol 2006, 185, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.A.; Arumugam, M.; Mondal, S.; Rajeswari, H.S.; Ramakumar, S.; Ajitkumar, P. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Cell Division Protein, FtsE, Is an ATPase in Dimeric Form. Protein Journal 2015, 34, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.L.; Suling, W.J.; Ross, L.J.; Seitz, L.E.; Reynolds, R.C. 2-Alkoxycarbonylaminopyridines: Inhibitors of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis FtsZ. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2002, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Vijay, S.; Arumugam, M.; Anand, D.; Mir, M.; Ajitkumar, P. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Expresses FtsE Gene through Multiple Transcripts. Curr Microbiol 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrici, D.; Marakalala, M.J.; Holton, J.M.; Prigozhin, D.M.; Gee, C.L.; Zhang, Y.J.; Rubin, E.J.; Alber, T. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis FtsX Extracellular Domain Activates the Peptidoglycan Hydrolase, RipC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 8037–8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrici, D.; Marakalala, M.J.; Holton, J.M.; Prigozhin, D.M.; Gee, C.L.; Zhang, Y.J.; Rubin, E.J.; Alber, T. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis FtsX Extracellular Domain Activates the Peptidoglycan Hydrolase, RipC. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 8037–8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plocinska, R.; Martinez, L.; Gorla, P.; Pandeeti, E.; Sarva, K.; Blaszczyk, E.; Dziadek, J.; Madiraju, M. V.; Rajagopalan, M. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis MtrB Sensor Kinase Interactions with FtsI and Wag31 Proteins Reveal a Role for MtrB Distinct from That Regulating MtrA Activities. J Bacteriol 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, L.; Chi, X.; Han, Y.; Lin, Y.; Si, S.; Jiang, J. Identification of Anti-Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Agents Targeting the Interaction of Bacterial Division Proteins FtsZ and SepFe. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paritala, H.; Carroll, K.S. New Targets and Inhibitors of Mycobacterial Sulfur Metabolism. Infectious disorders drug targets 2013, 13, 85–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.; de Carvalho, L.P.S.; Bryk, R.; Ehrt, S.; Marrero, J.; Park, S.W.; Schnappinger, D.; Venugopal, A.; Nathan, C. Central Carbon Metabolism in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: An Unexpected Frontier. Trends Microbiol 2011, 19 7, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrt, S.; Rhee, K. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Metabolism and Host Interaction: Mysteries and Paradoxes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013, 374, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, Kyu Y. ; Carvalho, L.; Bryk, Ruslana; Ehrt, Sabine; Nathan, C. Central Carbon Metabolism in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: An Unexpected Frontiers. Trends Microbiol 2011, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, Y.S.; Fukuda, T.; Sena, C.B.C.; Yamaryo-Botte, Y.; McConville, M.J.; Kinoshita, T. Inositol Lipid Metabolism in Mycobacteria: Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2011, 1810, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D.C.; Ocampo, M.; Varela, Y.; Curtidor, H.; Patarroyo, M.A.; Patarroyo, M.E. Mce4F Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Protein Peptides Can Inhibit Invasion of Human Cell Lines. Pathog Dis 2015, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieweger, R.A.; Wilburn, K.M.; Montague, C.R.; Roszkowski, E.K.; Kelly, C.M.; Southard, T.L.; Sondermann, H.; Nazarova, E. V.; VanderVen, B.C. MceG Stabilizes the Mce1 and Mce4 Transporters in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawełczyk, J.; Brzostek, A.; Minias, A.; Płociński, P.; Rumijowska-Galewicz, A.; Strapagiel, D.; Zakrzewska-Czerwińska, J.; Dziadek, J. Cholesterol-Dependent Transcriptome Remodeling Reveals New Insight into the Contribution of Cholesterol to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Pathogenesis. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrouy-Maumus, G. Cholesterol Acquisition by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Virulence 2015, 6, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, M.D.; Chang, J.C.; Pandey, A.K.; Sassetti, C.M.; Sherman, D.R. Role of Cholesterol in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection. Indian J Exp Biol 2009, 47, 407–411. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.K.; Sassetti, C.M. Mycobacterial Persistence Requires the Utilization of Host Cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 4376–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarova, E.; Montague, C.R.; La, T.; Wilburn, K.M.; Sukumar, N.; Lee, W.; Caldwell, S.; Russell, D.; VanderVen, B. Rv3723/LucA Coordinates Fatty Acid and Cholesterol Uptake in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Elife 2017, 6, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, K.M.; Fieweger, R.; VanderVen, B. Cholesterol and Fatty Acids Grease the Wheels of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Pathogenesis. Pathog Dis 2018, 76 2, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc-Kielbik, I.; Kielbik, M.; Przygodzka, P.; Brzostek, A.; Dziadek, J.; Klink, M. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Requires Cholesterol Oxidase to Disrupt TLR2 Signalling in Human Macrophages. Mediators Inflamm 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, A.M.; Workman, S.D.; Watanabe, N.; Worrall, L.J.; Strynadka, N.C.J.; Eltis, L.D. IpdAB, a Virulence Factor in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, Is a Cholesterol Ring-Cleaving Hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.A.M.; Berr??do-Pinho, M.; Rosa, T.L.S.A.; Pujari, V.; Lemes, R.M.R.; Lery, L.M.S.; Silva, C.A.M.; Guimar??es, A.C.R.; Atella, G.C.; Wheat, W.H.; et al. The Essential Role of Cholesterol Metabolism in the Intracellular Survival of Mycobacterium Leprae Is Not Coupled to Central Carbon Metabolism and Energy Production. J Bacteriol 2015, 197, 3698–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pethe, K.; Sequeira, P.C.; Agarwalla, S.; Rhee, K.; Kuhen, K.; Phong, W.Y.; Patel, V.; Beer, D.; Walker, J.R.; Duraiswamy, J.; et al. A Chemical Genetic Screen in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Identifies Carbon-Source-Dependent Growth Inhibitors Devoid of in Vivo Efficacy. Nat Commun 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Pooja; Borah, K. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolic Fluxes. Biosci Rep 2022, 42, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Sohaskey, C.D.; Pfeiffer, C.; Datta, P.; Parks, M.; McFadden, J.; North, R.J.; Gennaro, M.L. Carbon Flux Rerouting during Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Growth Arrest. Mol Microbiol 2010, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughn, A.D.; Rhee, K.Y. Metabolomics of Central Carbon Metabolism in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouzy, A.; Poquet, Y.; Neyrolles, O. Amino Acid Capture and Utilization within the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Phagosome. Future Microbiol 2014, 9 5, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouzy, A.; Poquet, Y.; Neyrolles, O. Nitrogen Metabolism in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Physiology and Virulence. Nat Rev Microbiol 2014, 12, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouzy, A.; Larrouy-Maumus, G.; Wu, T. Di; Peixoto, A.; Levillain, F.; Lugo-Villarino, G.; Gerquin-Kern, J.L.; De Carvalho, L.P.S.; Poquet, Y.; Neyrolles, O. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Nitrogen Assimilation and Host Colonization Require Aspartate. Nat Chem Biol 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.J.; Jenkins, V.A.; Barton, G.R.; Bryant, W.A.; Krishnan, N.; Robertson, B.D. Deciphering the Metabolic Response of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis to Nitrogen Stress. Mol Microbiol 2015, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Wang, L.; Raza, S.H.A.; Wang, Z. Nitrogen Metabolism in Mycobacteria: The Key Genes and Targeted Antimicrobials. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.; Kloosterman, T.G.; Kok, J.; Kuipers, O.P. GlnR-Mediated Regulation of Nitrogen Metabolism in Lactococcus Lactis. J Bacteriol 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Kang, X.; Wu, J.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Zhao, G.; Wang, J. Transcriptional Self-Regulation of the Master Nitrogen Regulator GlnR in Mycobacteria. J Bacteriol 2023, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, K.; Beyß, M.; Theorell, A.; Wu, H.; Basu, P.; Mendum, T.A.; Nӧh, K.; Beste, D.J.V.; McFadden, J. Intracellular Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Exploits Multiple Host Nitrogen Sources during Growth in Human Macrophages. Cell Rep 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Hartman, T.E.; Beites, T.; Kim, J.-H.; Eoh, H.; Engelhart, C.A.; Zhu, L.; Wilson, D.J.; Aldrich, C.C.; Ehrt, S.; et al. Metabolically Distinct Roles of NAD Synthetase and NAD Kinase Define the Essentiality of NAD and NADP in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. mBio 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, S.; Yamasaki, M.; Maruyama, Y.; Momma, K.; Kawai, S.; Hashimoto, W.; Mikami, B.; Murata, K. NAD-Binding Mode and the Significance of Intersubunit Contact Revealed by the Crystal Structure of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis NAD Kinase-NAD Complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyrolles, O.; Wolschendorf, F.; Mitra, A.; Niederweis, M. Mycobacteria, Metals, and the Macrophage. Immunol Rev 2015, 264, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.V.; Puri, R.V.; Chauhan, P.; Kar, R.; Rohilla, A.; Khera, A.; Tyagi, A.K. Disruption of Mycobactin Biosynthesis Leads to Attenuation of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis for Growth and Virulence. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Rubinstein, J.L. Structural Analysis of Mycobacterial Electron Transport Chain Complexes by CryoEM. Biochem Soc Trans 2023, 51, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, P.; Akhter, Y. A Review on Enzyme Complexes of Electron Transport Chain from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis as Promising Drug Targets. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 212, 474–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Zhang, J.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X.; Cook, G.M.; Zhang, T. Nitric Oxide-Dependent Electron Transport Chain Inhibition by the Cytochrome Bc1inhibitor and Pretomanid Combination Kills Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazakan, V.; Wong, C.-F.; Harikishore, A.; Pethe, K.; Grüber, G. Cryo-Electron Microscopy Structure of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosi s Cytochrome Bcc : Aa 3 Supercomplex and a Novel Inhibitor Targeting Subunit Cytochrome c I. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori-Anyinam, B.; Riley, A.J.; Jobarteh, T.; Gitteh, E.; Sarr, B.; Faal-Jawara, T.I.; Rigouts, L.; Senghore, M.; Kehinde, A.; Onyejepu, N.; et al. Comparative Genomics Shows Differences in the Electron Transport and Carbon Metabolic Pathways of Mycobacterium Africanum Relative to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Suggests an Adaptation to Low Oxygen Tension. Tuberculosis 2020, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.M.; Denny, W.A. Inhibitors of Enzymes in the Electron Transport Chain of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. In Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 52, 97–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, E.H.S.; Tuckerman, J.R.; Gonzalez, G.; Gilles-Gonzalez, M.-A. DosT and DevS Are Oxygen-Switched Kinases in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Protein Science 2007, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotboom, D.J.; Ettema, T.W.; Nijland, M.; Thangaratnarajah, C. Bacterial Multi-Solute Transporters. FEBS Lett 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, M.; van Veen, H.W.; Konings, W.N. Molecular Properties of Bacterial Multidrug Transporters. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.; Khan, T.A.; Ahmad, I.; Muhammad, S.; Wei, D.Q. Diversity and Novel Mutations in Membrane Transporters of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Brief Funct Genomics 2023, 22, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, E.; Arrigo, P.; Bellinzoni, M.; Silva, P.A.E.; Martín, C.; Aínsa, J.A.; Guglierame, P.; Riccardi, G. The Multidrug Transporters Belonging to Major Facilitator Superfamily in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Mol Med 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.D.; Aínsa, J.A.; Riccardi, G. Role of Mycobacterial Efflux Transporters in Drug Resistance: An Unresolved Question. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2006, 30, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, E.; Arrigo, P.; Bellinzoni, M.; Silva, P.E.A.; Martín, C.; Aínsa, J.A.; Guglierame, P.; Riccardi, G. The Multidrug Transporters Belonging to Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Molecular Medicine 2002, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, J.S.; Nepravishta, R.; Guy, C.S.; Harrison, J.; Angulo, J.; Cameron, A.D.; Fullam, E. Structural Basis of Glycerophosphodiester Recognition by the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Substrate-Binding Protein UgpB. ACS Chem Biol 2019, 14, 1879–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Zhou, H.; Jin, J.; Zhou, W.; Bartlam, M.; Rao, Z. Structural Analysis of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter Subunit UgpB Reveals Specificity for Glycerophosphocholine. FEBS Journal 2014, 281, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Zhou, H.; Jin, J.; Zhou, W.; Bartlam, M.; Rao, Z. Structural Analysis of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter Subunit UgpB Reveals Specificity for Glycerophosphocholine. FEBS Journal 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boritsch, E.C.; Brosch, R. Evolution of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: New Insights into Pathogenicity and Drug Resistance. Microbiol Spectr 2016, 4 5, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamian, M.; Kooti, S.; Abiri, R.; Khazayel, S.; Kadivarian, S.; Borji, S.; Alvandi, A. Prevalence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Mutations Associated with Isoniazid and Rifampicin Resistance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis 2023, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Dwivedi, S.P.; Gaharwar, U.S.; Meena, R.; Rajamani, P.; Prasad, T. Recent Updates on Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J Appl Microbiol 2020, 128, 1547–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhuri, B.S.; Bhakta, S.; Barik, R.; Basu, J.; Kundu, M.; Chakrabarti, P. Overexpression and Functional Characterization of an ABC (ATP-Binding Cassette) Transporter Encoded by the Genes DrrA and DrrB of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Biochem J 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.D.; Sirous, M.; Absalan, Z.; Tabandeh, M.R.; Savari, M. Comparison of DrrA and DrrB Efflux Pump Genes Expression in Drug-Susceptible and -Resistant Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Strains Isolated from Tuberculosis Patients in Iran. Infect Drug Resist 2019, 12, 3437–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Mizrahi, V.; Warner, D.F. The Impact of Drug Resistance on Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Physiology: What Can We Learn from Rifampicin? 2014, 17. [CrossRef]

- Drobniewski, F.; Balabanova, Y.; Ruddy, M.; Weldon, L.; Jeltkova, K.; Brown, T.; Malomanova, N.; Elizarova, E.; Melentyey, A.; Mutovkin, E.; et al. Rifampin- and Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Russian Civilians and Prison Inmates: Dominance of the Beijing Strain Family. Emerg Infect Dis 2002, 8, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; van Veen, H.W.; Murakami, S.; Pos, K.M.; Luisi, B.F. Structure, Mechanism and Cooperation of Bacterial Multidrug Transporters. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2015, 33, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Akhter, Y. Molecular Insights into the Differential Efflux Mechanism of Rv1634 Protein, a Multidrug Transporter of Major Facilitator Superfamily in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Proteins: Structure, Function and Bioinformatics 2022, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, N.K.; Mehra, S.; Kaushal, D. A Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Sigma Factor Network Responds to Cell-Envelope Damage by the Promising Anti-Mycobacterial Thioridazine. PLoS One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, N.K.; Mehra, S.; Didier, P.J.; Roy, C.J.; Doyle, L.A.; Alvarez, X.; Ratterree, M.; Be, N.A.; Lamichhane, G.; Jain, S.K.; et al. Genetic Requirements for the Survival of Tubercle Bacilli in Primates. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010, 201, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, P.; Akhter, Y. The Drug Binding Sites and Transport Mechanism of the RND Pumps from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Arch Biochem Biophys 2016, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, C.M.; Babii, S.O.; Pandya, A.N.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Mehla, J.; Scott, R.; Hegde, P.; Prathipati, P.K.; Acharya, A.; et al. Proton Transfer Activity of the Reconstituted Mycobacterium Tuberculosis MmpL3 Is Modulated by Substrate Mimics and Inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thouvenel, L.; Rech, J.; Guilhot, C.; Bouet, J.Y.; Chalut, C. In Vivo Imaging of MmpL Transporters Reveals Distinct Subcellular Locations for Export of Mycolic Acids and Non-Essential Trehalose Polyphleates in the Mycobacterial Outer Membrane. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Duan, H.; Yan, H.; Liu, X.; Peng, L.; Hu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liang, L.; Shi, H.; Zhao, G.; et al. Specifically Targeting Mtb Cell-Wall and TMM Transporter: The Development of MmpL3 Inhibitors. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, C.C.; Hsu, F.F.; Arnett, E.; Dunaj, J.L.; Davidson, P.M.; Pacheco, S.A.; Harriff, M.J.; Lewinsohn, D.M.; Schlesinger, L.S.; Purdy, G.E. The Mycobacterium Tuberculosis MmpL11 Cell Wall Lipid Transporter Is Important for Biofilm Formation, Intracellular Growth, and Nonreplicating Persistence. Infect Immun 2017, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famelis, N.; Geibel, S.; Van Tol, D. Mycobacterial Type VII Secretion Systems. Biol Chem 2023, 404, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, AM.; Pittius, G.; Nicolaas, C.; DiGiuseppe Champion, P.; Cox, J.; Luirink, J.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, CMJE. ; Appelmelk, BJ.; Bitter, W. Type VII Secretion - Mycobacteria Show the Way. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007, 5, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.M.; Gey van Pittius, N.C.; Champion, P.A.D.; Cox, J.; Luirink, J.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.J.E.; Appelmelk, B.J.; Bitter, W. Type VII Secretion--Mycobacteria Show the Way. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Calzada, A.; Famelis, N.; Llorca, O.; Geibel, S. Type VII Secretion Systems: Structure, Functions and Transport Models. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, A.; Zahra, A.; Thompson, V.; Sirisaengtaksin, N.; Wells, A.; Porto, M.; Köster, S.; Penberthy, K.; Kubota, Y.; Dricot, A.; et al. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Type VII Secreted Effector EsxH Targets Host ESCRT to Impair Trafficking. PLoS Pathog 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosskey, T.D.; Beckham, K.S.H.; Wilmanns, M. The ATPases of the Mycobacterial Type VII Secretion System: Structural and Mechanistic Insights into Secretion. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2020, 152, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhang, J.; Mai, J.; Jiang, J.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, L.; et al. Crosstalk between the Ancestral Type VII Secretion System ESX-4 and Other T7SS in Mycobacterium Marinum. iScience 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, N.; Padmanaban, S.; Dutta, S. Cryo-EM Reveals the Membrane-Binding Phenomenon of EspB, a Virulence Factor of the Mycobacterial Type VII Secretion System. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsbers, A.; Eymery, M.; Gao, Y.; Menart, I.; Vinciauskaite, V.; Siliqi, D.; Peters, P.J.; McCarthy, A.; Ravelli, R.B.G. The Crystal Structure of the EspB-EspK Virulence Factor-Chaperone Complex Suggests an Additional Type VII Secretion Mechanism in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengarajan, J.; Bloom, B.R.; Rubin, E.J. Genome-Wide Requirements for Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Adaptation and Survival in Macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 8327–8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkarslan, S.; Peterson, E.J.R.; Rustad, T.R.; Minch, K.J.; Reiss, D.J.; Morrison, R.; Ma, S.; Price, N.D.; Sherman, D.R.; Baliga, N.S. A Comprehensive Map of Genome-Wide Gene Regulation in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Sci Data 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namouchi, A.; Didelot, X.; Schöck, U.; Gicquel, B.; Rocha, E.P.C. After the Bottleneck: Genome-Wide Diversification of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex by Mutation, Recombination, and Natural Selection. Genome Res 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkowiak, B.; Romanowski, K.; Sekirov, I.; Gardy, J.L.; Johnston, J.C. Comparing Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Transmission Reconstruction Models from Whole Genome Sequence Data. Epidemiol Infect 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. T.; Brosch, R.; Parkhill, J.; Garnier, T.; Churcher, C.; Harris, D.; Gordon, S. V.; Eiglmeier, K.; Gas, S.; Barry, C. E.; et al. Deciphering the Biology of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis from the Complete Genome Sequence. Nature 1998, 393, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabbeer, A.; Cowan, L.; Ozcaglar, C.; Rastogi, N.; Vandenberg, S.; Yener, B.; Bennett, K.P. TB-Lineage: An Online Tool for Classification and Analysis of Strains of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex. Infect Genet Evol 2012, 12 4, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padane, A.; Harouna Hamidou, Z.; Drancourt, M.; Saad, J. CRISPR-Based Detection, Identification and Typing of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex Lineages. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Cheng, X.; Kaisaier, A.; Wan, J.; Luo, S.; Ren, J.; Sha, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhen, Y.; Liu, W.; et al. Effects of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Lineages and Regions of Difference (RD) Virulence Gene Variation on Tuberculosis Recurrence. Ann Transl Med 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahal, M.R.; Senelle, G.; La, K.; Molina-Moya, B.; Dominguez, J.; Panda, T.; Cambau, E.; Refregier, G.; Sola, C.; Guyeux, C. An Updated Evolutionary History and Taxonomy of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Lineage 5, Also Called M. Africanum. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N.; Malaga, W.; Constant, P.; Caws, M.; Thi Hoang Chau, T.; Salmons, J.; Thi Ngoc Lan, N.; Bang, N.D.; Daffé, M.; Young, D.B.; et al. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Lineage Influences Innate Immune Response and Virulence and Is Associated with Distinct Cell Envelope Lipid Profiles. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, J.; Bishai, W.R. Regulation of Virulence Genes in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Int J Med Microbiol 2001, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindi, L.; Medici, C.; Bimbi, N.; Buzzigoli, A.; Lari, N.; Garzelli, C. Genomic Variability of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Strains of the Euro-American Lineage Based on Large Sequence Deletions and 15-Locus MIRU-VNTR Polymorphism. PLoS One 2014, 9, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinga, L.A.; Abeel, T.; Desjardins, C.A.; Dlamini, T.C.; Cassell, G.; Chapman, S.B.; Birren, B.W.; Earl, A.M.; van der Walt, M. Draft Genome Sequences of Two Extensively Drug-Resistant Strains of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Belonging to the Euro-American S Lineage. Genome Announc 2016, 4, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leon, J.; Jiang, G.; Ma, Y.; Rubin, E.; Fortune, S.; Sun, J. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis ESAT-6 Exhibits a Unique Membrane-Interacting Activity That Is Not Found in Its Ortholog from Non-Pathogenic Mycobacterium Smegmatis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gey Van Pittius, N.C.; Sampson, S.L.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Van Helden, P.D.; Warren, R.M. Evolution and Expansion of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis PE and PPE Multigene Families and Their Association with the Duplication of the ESAT-6 (Esx) Gene Cluster Regions. BMC Evol Biol 2006, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Pelayo, M.; Caimi, K.; Inwald, J.; Hinds, J.; Bigi, F.; Romano, M.; van Soolingen, D.; Hewinson, R.G.; Cataldi, A.; Gordon, S. Microarray Analysis of Mycobacterium Microti Reveals Deletion of Genes Encoding PE-PPE Proteins and ESAT-6 Family Antigens. Tuberculosis, 2004; 84, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnvig, K.B.; Young, D.B. Non-Coding RNA and Its Potential Role in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Pathogenesis. RNA Biol 2012, 9, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnvig, K.B.; Comas, I.; Thomson, N.R.; Houghton, J.; Boshoff, H.I.; Croucher, N.J.; Rose, G.; Perkins, T.T.; Parkhill, J.; Dougan, G.; et al. Sequence-Based Analysis Uncovers an Abundance of Non-Coding RNA in the Total Transcriptome of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujwar, S.; Pardasani, K.R. Prediction of Riboswitch as a Potential Drug Target and Design of Its Optimal Inhibitors for Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Int J Comput Biol Drug Des 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahoua, B.; Sevdalis, S.E.; Soto, A.M. Effect of Sequence on the Interactions of Divalent Cations with M-Box Riboswitches from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Bacillus Subtilis. Biochemistry 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, S.; De Montellano, P.R.O. The DosS-DosT/DosR Mycobacterial Sensor System. Biosensors (Basel) 2013, 3, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honaker, R.W.; Leistikow, R.L.; Bartek, I.L.; Voskui, M.I. Unique Roles of DosT and DosS in DosR Regulon Induction and Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Dormancy. Infect Immun 2009, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Park, K.J.; Ko, I.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Oh, J. Il Different Roles of DosS and DosT in the Hypoxic Adaptation of Mycobacteria. J Bacteriol 2010, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Toledo, J.C.; Patel, R.P.; Lancaster, J.R.; Steyn, A.J.C. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis DosS Is a Redox Sensor and DosT Is a Hypoxia Sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevalkar, R.R.; Glasgow, J.N.; Pettinati, M.; Marti, M.A.; Reddy, V.P.; Basu, S.; Alipour, E.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Estrin, D.A.; Lancaster, J.R.; et al. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis DosS Binds H2S through Its Fe3+ Heme Iron to Regulate the DosR Dormancy Regulon. Redox Biol 2022, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Colvin, C.J.; Johnson, B.K.; Kirchhoff, P.D.; Wilson, M.; Jorgensen-Muga, K.; Larsen, S.D.; Abramovitch, R.B. Inhibitors of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis DosRST Signaling and Persistence. Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadda, A.; Jensen, D.; Tomko, E.J.; Manzano, A.R.; Nguyen, B.; Lohman, T.M.; Galburt, E.A. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis DNA Repair Helicase UvrD1 Is Activated by Redox-Dependent Dimerization via a 2B Domain Cysteine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Vultos, T.; Mestre, O.; Tonjum, T.; Gicquel, B. DNA Repair in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Revisited. In Proceedings of the FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2009, 33, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, D.M.; Hinds, J.; Butcher, P.D.; Gillespie, S.H.; McHugh, T.D. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis DNA Repair in Response to Subinhibitory Concentrations of Ciprofloxacin. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2008, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, V.; Andersen, S.J. DNA Repair in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. What Have We Learnt from the Genome Sequence? Mol Microbiol 1998, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeldenov, S.; Saparbayev, M.; Khassenov, B. Biochemical Characterization of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis DNA Repair Enzymes – Nfo, XthA and Nei2. Cent Asian J Glob Health 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miggiano, R.; Morrone, C.; Rossi, F.; Rizzi, M. Targeting Genome Integrity in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: From Nucleotide Synthesis to DNA Replication and Repair. Molecules 2020, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Guardians of the Mycobacterial Genome: A Review on DNA Repair Systems in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Microbiology (United Kingdom) 2017, 163, 1740–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, J.D.; Singh, A.K.; Park, S.T.; Lyubetskaya, A.; Peterson, M.W.; Gomes, A.L.C.; Potluri, L.P.; Raman, S.; Galagan, J.E.; Husson, R.N. Comprehensive Definition of the SigH Regulon of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Reveals Transcriptional Control of Diverse Stress Responses. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, S.; Song, T.; Puyang, X.; Bardarov, S.; Jacobs, J.; Husson, R.N. The Alternative Sigma Factor Sigh Regulates Major Components of Oxidative and Heat Stress Responses in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 2001, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioetto-Mazzabò, L.; Boldrin, F.; Beauvineau, C.; Speth, M.; Marina, A.; Namouchi, A.; Segafreddo, G.; Cimino, M.; Favre-Rochex, S.; Balasingham, S.; et al. SigH Stress Response Mediates Killing of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis by Activating Nitronaphthofuran Prodrugs via Induction of Mrx2 Expression. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steyn, A.J.C.; Collins, D.M.; Hondalus, M.K.; Jacobs, W.R.; Pamela Kawakami, R.; Bloom, B.R. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis WhiB3 Interacts with RpoV to Affect Host Survival but Is Dispensable for in Vivo Growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimann, J.D. The Extracytoplasmic Function (ECF) Sigma Factors. Adv Microb Physiol 2002, 46, 47–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganelli, R.; Dubnau, E.; Tyagi, S.; Kramer, F.R.; Smith, I. Differential Expression of 10 Sigma Factor Genes in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 1999, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosse-Siestrup, B.T.; Gupta, T.; Helms, S.; Tucker, S.L.; Voskuil, M.I.; Quinn, F.D.; Karls, R.K. A Role for Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Sigma Factor c in Copper Nutritional Immunity. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Ravi, J.; Datta, P.; Chen, T.; Schnappinger, D.; Bassler, K.E.; Balázsi, G.; Gennaro, M.L. Reconstruction and Topological Characterization of the Sigma Factor Regulatory Network of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Nat Commun 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustyala, K.K.; Malkhed, V.; Chittireddy, V.R.; Vuruputuri, U. Virtual Screening Studies to Identify Novel Inhibitors for Sigma F Protein of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Int J Mycobacteriol 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, A.E.; MacGurn, J.A.; Baer, C.E.; Falick, A.M.; Cox, J.S.; Alber, T. M. Tuberculosis Ser/Thr Protein Kinase D Phosphorylates an Anti-Anti-Sigma Factor Homolog. PLoS Pathog 2007, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruzzo, G.; Serafini, A.; Finotello, F.; Sanavia, T.; Cioetto-Mazzabò, L.; Boldrin, F.; Lavezzo, E.; Barzon, L.; Toppo, S.; Provvedi, R.; et al. Role of the Extracytoplasmic Function Sigma Factor SigE in the Stringent Response of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burian, J.; Yim, G.; Hsing, M.; Axerio-Cilies, P.; Cherkasov, A.; Spiegelman, G.B.; Thompson, C.J. The Mycobacterial Antibiotic Resistance Determinant WhiB7 Acts as a Transcriptional Activator by Binding the Primary Sigma Factor SigA (RpoV). Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, B.; Behera, D.; Khan, M.Z.; Singh, N.K.; Sowpati, D.T.; Gopal, B.; Nandicoori, V.K. The Unique N-Terminal Region of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Sigma Factor A Plays a Dominant Role in the Essential Function of This Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barik, S.; Sureka, K.; Mukherjee, P.; Basu, J.; Kundu, M. RseA, the SigE Specific Anti-Sigma Factor of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, Is Inactivated by Phosphorylation-Dependent ClpC1P2 Proteolysis. Mol Microbiol 2010, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahlwes, K.C.; Dias, B.R.S.; Campos, P.C.; Alvarez-Arguedas, S.; Shiloh, M.U. Pathogenicity and Virulence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Virulence 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrellad, M.A.; Klepp, L.I.; Gioffré, A.; García, J.S.; Morbidoni, H.R.; de la Paz Santangelo, M.; Cataldi, A.A.; Bigi, F. Virulence Factors of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex. Virulence 2013, 4, 3–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgeur, M.; Brosch, R. Evolution of Virulence in the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex. Curr Opin Microbiol 2018, 41, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon-Luing, L.A.; Palacios, Y.; Ruiz, A.; Téllez-Navarrete, N.A.; Chavez-Galan, L. Virulence Factors of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis as Modulators of Cell Death Mechanisms. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.; Prisic, S.; Kang, C.-M.; Lun, S.; Guo, H.; Murry, J.P.; Rubin, E.J.; Husson, R.N. Mycobacterial Gene CuvA Is Required for Optimal Nutrient Utilization and Virulence. Infect Immun 2014, 82, 4104–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazaei, C. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Lipids: Insights into Molecular Mechanisms from Persistence to Virulence. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2018, 63, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modlin, S.J.; Elghraoui, A.; Gunasekaran, D.; Zlotnicki, A.M.; Dillon, N.A.; Dhillon, N.; Kuo, N.; Robinhold, C.; Chan, C.K.; Baughn, A.D.; et al. Structure-Aware Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Functional Annotation Uncloaks Resistance, Metabolic, and Virulence Genes. mSystems 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-López, B.A.; Correa, F.; Moreno- Altamirano, M.M.B.; Espitia, C.; Hernández-Longoria, R.; Oliva-Ramírez, J.; Padierna-Olivos, J.; Sánchez-García, F.J. LprG and PE_PGRS33 Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Virulence Factors Induce Differential Mitochondrial Dynamics in Macrophages. Scand J Immunol 2019, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Nie, X.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Q.; Shi, K.-X.; You, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, H.; Yan, B.; Niu, C.; et al. Mycobacterial Fatty Acid Catabolism Is Repressed by FdmR to Sustain Lipogenesis and Virulence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieck, B.; Degiacomi, G.; Zimmermann, M.; Cascioferro, A.; Boldrin, F.; Lazar-Adler, N.R.; Bottrill, A.R.; le Chevalier, F.; Frigui, W.; Bellinzoni, M.; et al. PknG Senses Amino Acid Availability to Control Metabolism and Virulence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis; 2017; Vol. 13; ISBN 1111111111.

- Parthasarathy, G.; Lun, S.; Guo, H.; Ammerman, N.C.; Geiman, D.E.; Bishai, W.R. Rv2190c, an NlpC/P60 Family Protein, Is Required for Full Virulence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. PLoS One 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, K.; Chen, B.; Miller, J.L.; Azogue, S.; Gurses, S.; Hsu, T.; Glickman, M.; Jacobs, W.R.; Porcelli, S.A.; Briken, V. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis NuoG Is a Virulence Gene That Inhibits Apoptosis of Infected Host Cells. PLoS Pathog 2007, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, G.M.; Smith, I. Identification of an ABC Transporter Required for Iron Acquisition and Virulence in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 2006, 188, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisiegel, M.; Mollenkopf, H.J.; Hahnke, K.; Koch, M.; Dietrich, I.; Reece, S.T.; Kaufmann, S.H.E. Combination of Host Susceptibility and Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Virulence Define Gene Expression Profile in the Host. Eur J Immunol 2009, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, L.R.; Ensergueix, D.; Perez, E.; Gicquel, B.; Guilhot, C. Identification of a Virulence Gene Cluster of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis by Signature-Tagged Transposon Mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 1999, 34, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodin, P.; Majlessi, L.; Marsollier, L.; De Jonge, M.I.; Bottai, D.; Demangel, C.; Hinds, J.; Neyrolles, O.; Butcher, P.D.; Leclerc, C.; et al. Dissection of ESAT-6 System 1 of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Impact on Immunogenicity and Virulence. Infect Immun 2006, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, S.B.; Dubnau, E.; Kolesnikova, I.; Laval, F.; Daffe, M.; Smith, I. The Mycobacterium Tuberculosis PhoPR Two-Component System Regulates Genes Essential for Virulence and Complex Lipid Biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol 2006, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkowski, E.F.; Miller, B.K.; Mccann, J.R.; Sullivan, J.T.; Malik, S.; Allen, I.C.; Godfrey, V.; Hayden, J.D.; Braunstein, M. An Orphaned Mce-Associated Membrane Protein of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Is a Virulence Factor That Stabilizes Mce Transporters. Mol Microbiol 2016, 100, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Tripathi, D.; Kant, S.; Chandra, H.; Bhatnagar, R.; Banerjee, N. The Conserved Hypothetical Protein Rv0574c Is Required for Cell Wall Integrity, Stress Tolerance, and Virulence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Infect Immun 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group or Complex | Principal Species | Pathogenicity and Disease1 |

|---|---|---|

|

M. tuberculosis Complex (MTBC) |

tuberculosis kansasii gastri bovis africanum |

Pathogenic/ tuberculosis |

| M. kansasii Group |

kansasii gastri |

Pathogenic/ pulmonary and soft tissue |

| M. avium Complex |

avium colombiense intracellulare |

Pathogenic/pulmonary in immunocompromised |

| M. simiae Complex |

kubicae florentinum |

Generally non-pathogenic |

| M. celatum Group |

xenopi celatum |

Pathogenic/pulmonary in immunocompromised |

| M. terrae Complex |

terrae hibernae |

Generally non-pathogenic |

| M. smegmatis Group |

smegmatis thermoresistible |

Generally non-pathogenic |

| M. fortuitum Group |

fortuitum peregrinum |

Pathogenic/soft tissue |

| M. abscessus-chelonae Complex |

abscessus chelonae |

Pathogenic/pulmonary in immunocompromised |

| Sigma | Presence | Response | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| σA | All mycobacteria | Nutritional deficiency and the general response to the stress |

During the infection it was observed that its expression increases in some strains but not for the H37Rv strain |

| σB | All mycobacteria | Nutritional deficiency and the general response to the stress |

It is not essential for the survival of the bacillus |

| σC | All pathogenic mycobacteria | All pathogenic mycobacteria |

Act on the Immunopathological phenotype of tuberculosis |

| σD | All mycobacteria except M. leprae | It regulates genes linked to starving response during nutritional deficiency |

Act on the Immunopathological phenotype of tuberculosis |

| σE | All mycobacteria | Action during stress on the bacillary surface and during the response to thermal shock |

Influence on the immunopathological phenotype |

| σF | All mycobacteria except M. leprae | Involved in the biosynthesis of the mycobacterial envelope |

Influencing the immunopathological phenotype |

| σG | All mycobacteria except M. leprae |

Acts on the SOS response, a global response to DNA damage, and acts on the survival of the bacillus during macrophage infection |

Present as characteristics the presence of over 120 amino acid residues in the C-terminal |

| σH |

All mycobacteria except M. leprae |

Includes participation during oxidative stress, heat stress |

Influence on the immunopathogenic phenotype |

| σI |

Only in pathogenic mycobacteria |

It is induced during thermal shock processes |

Present as characteristics the presence of over 120 amino acid residues in the C-terminal |

| σJ |

MTB | Acting during oxidative stress |

Present as characteristics the presence of over 120 amino acid residues in the C-terminal |

| σL | MTB | Is bound to the virulence and biosynthesis of phthiocerol dimycocerosate |

An essential lipid for the virulence of MTB |

| σM |

MTB |

Is responsible for the long-term adaptation of the bacillus in vivo |

- |

| σK | MTB |

Yet its performance is unknown |

- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).