1. Introduction

GDM is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance with onset during pregnancy. Pregnancy-related changes in hormone balance and weight gain produce a decreased response to insulin. In most pregnancies, insulin production is adequate to overcome this resistance; however, in some circumstances, this does not occur, thus leading to the onset of gestational diabetes (GDM) [1].

GDM is diagnosed by an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with at least one abnormal result or a fasting glucose concentration ≥ 92 mg/dL. Usually, this condition resolves after childbirth, but it can recur years later as type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). Due to the progressive increase in the age of women at childbirth and in the rate of obesity and chronic diseases, GDM has become one of the most common complications diagnosed during gestation. According to Italian and European prevalence data, approximately 6-7% of all pregnancies are complicated by GDM every year, which counts for more than 40,000 new GDM diagnoses yearly in Italy [

2]. Notably, GDM is associated with increased maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, as well as long-term complications in both the mother and her offspring, thus representing a severe global public health issue in the world as well as in Italy [

3].

Targeted monitoring and treatment of GDM is required in order to minimize the occurrence of adverse outcomes [

4,

5,

6]. Appropriate management of GDM during pregnancy reduces the risk of preeclampsia, excessive maternal gestational weight gain, fetal macrosomia, severe perineal injury, shoulder dystocia, and neonatal hypoglycemia. Also, adequate management has a positive impact on potential maternal long-term metabolic adverse consequences, such as impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 DM or elevated Body Mass Index (BMI).

A targeted diet and physical activity represent the first-line interventions to obtain optimal glycemic control in pregnant women diagnosed with GDM. However, the definition of what represents an unsuccessful attempt at a targeted diet and exercise has not been established [

7,

8]. Consequently, the need to start pharmacotherapy is at the specialist’s discretion with wide variability in practice [

9,

10]. Both insulin and its analogues and oral antidiabetic drugs, including metformin and glibencamide, can be safely prescribed during pregnancy [

11,

12]. Two recent systematic reviews have found similar effectiveness of both compounds [

13,

14]. Yet, given the discrepancies of glycemic goals in different settings, patients’ compliance with treatment, and lack of data on long-term outcomes of oral antidiabetics in offspring, a broadly accepted consensus regarding the optimal approach to pharmacological treatment of GDM is still lacking.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) [

15] and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) [

16] support the use of insulin as first line therapy; notwithstanding this, they also approve the use of oral antidiabetics. Specifically, the ACOG recommends an oral agent for women who refuse insulin therapy or when the patient is considered unable to safely administer insulin. Among oral antidiabetic agents, metformin is to be preferred over glibencamide. The ADA states that metformin should not be used in women with hypertension, preeclampsia, or at risk for intrauterine growth restriction due to its potential for impacting fetal growth and for inducing an acidotic effect in the setting of placental insufficiency. On the other hand, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) states that in women with GDM in whom hyperglycemia cannot be adequately controlled with diet, metformin is a first-line drug alternative to insulin, although insulin is the most effective agent to control hyperglycemia due to the almost unlimited ability to increase and titrate doses [

17]. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the International College of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) consider oral antidiabetics an acceptable first-line approach in selected women, i.e., those with low fasting glucose levels, as oral agents are more likely to prevent hyperglycemia in these patients than in those with high fasting glucose levels [

18,

19]. Recently, the Italian Drug Agency (

Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA) has updated the therapeutic indication (summary of product characteristics, SmPC) for both the immediate- and the extended-release form of metformin during the periconceptional period and in pregnancy. The SmPC states that “if clinically appropriate, the use of metformin may be considered during pregnancy and in the periconceptional period in addition or as an alternative to insulin therapy” [20-23]. On this line, the Italian Association of Medical Diabetologists (AMD), the Italian Society of Diabetology (SID) and the Italian Study Group of Diabetes in pregnancy have jointly published a position paper stating that metformin may represent a therapeutic option in selected women with obesity, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), GDM, T2DM, and in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART); however, the authors highlight the need of further research on the topic, particularly on the long-term effects of

in-utero exposure to metformin [

24].

Italian population-based studies on antidiabetic drugs use in pregnancy are dated and limited to single regional experience. In this perspective, the AIFA has recently promoted the creation of a network, called MoM-Net (Monitoring Medication Use During Pregnancy - Network), which focuses on monitoring the appropriate use of different classes of medications in pregnancy, through the integration of different regional health databases.

The objective of this paper is to highlight the prescription pattern of antidiabetic drugs in Italy and to evaluate its appropriateness to promote subsequent targeted interventions to improve clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

The study population for this cross-sectional study was identified through a Common Data Model (CDM) based on three different data sources:

- -

The Regional Birth Registry (Certificato di Assistenza al Parto, CeDAP), concerning sociodemographic characteristics of the mother and data regarding the pregnancy and the newborn;

- -

The Demographic Database from which administrative records were retrieved for those registered in the regional healthcare system;

- -

The Drug Prescription Database which includes all prescriptions reimbursed by the Italian National Healthcare Service, including date of dispensing, brand, active substance and number of packages prescribed.

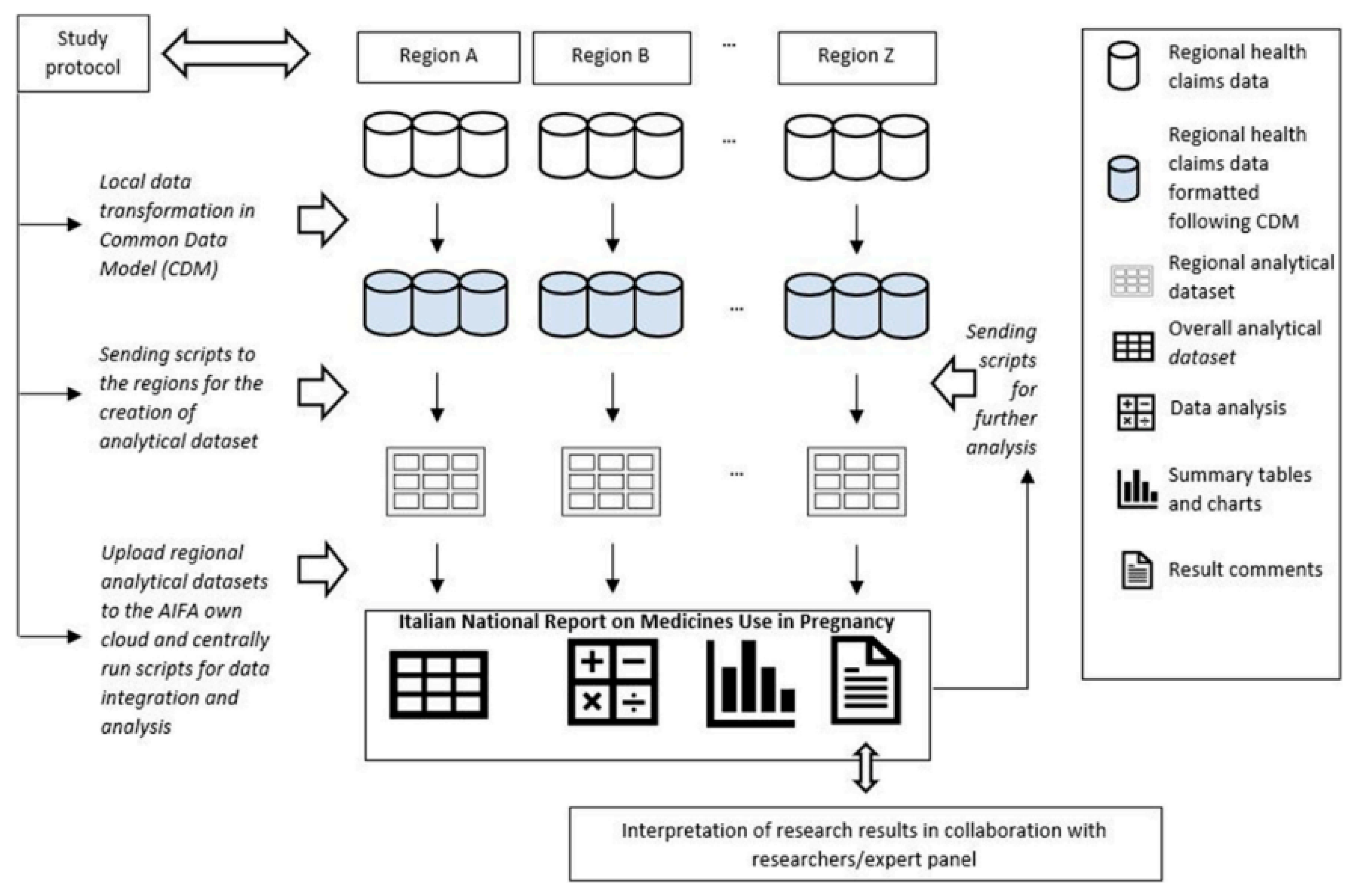

A unique identification code was then created for each entry to link these data sources at a regional level anonymously. Lazio Region designed the CDM and conducted the data analyses needed for its creation [

Figure 1][

25,

26]. Materials and methods were extensively reported in Belleudi et al, 2021 [

27].

We selected all women between 15 and 49 years old from eight Italian Regions ((Lombardy, Veneto, Emilia Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, Lazio, Puglia, Sardinia) who delivered in hospital between April 1, 2016 and March 31, 2018. We could not include voluntary and spontaneous abortions as those data are not recorded in the CeDAP database.

For each patient, the date of pregnancy onset was estimated using the gestational age at birth. The study considered three periods: three trimesters before, three trimesters during and three trimesters after gestation.

The prevalence of medication use was calculated as the percentage of women with at least one drug prescription before, during and after pregnancy. Purposely, this study focused on the prevalence of antidiabetics use in each period.

We defined the prevalence of drug use as “prevalent” when the medication was prescribed before conception and “incident” for new prescriptions occurring during pregnancy.

We also analyzed the shift to different antidiabetic categories (subgroups) and represented through a Sankey Diagram the pattern of use during the different trimesters, in which the arrow’s width is proportional to the flow rate. This allowed to display the proportion of women who changed their drug regimen during pregnancy. Similarly, the differences between antidiabetic prescriptions among different regions were assessed. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary NC) and R (R Core Team).

3. Results

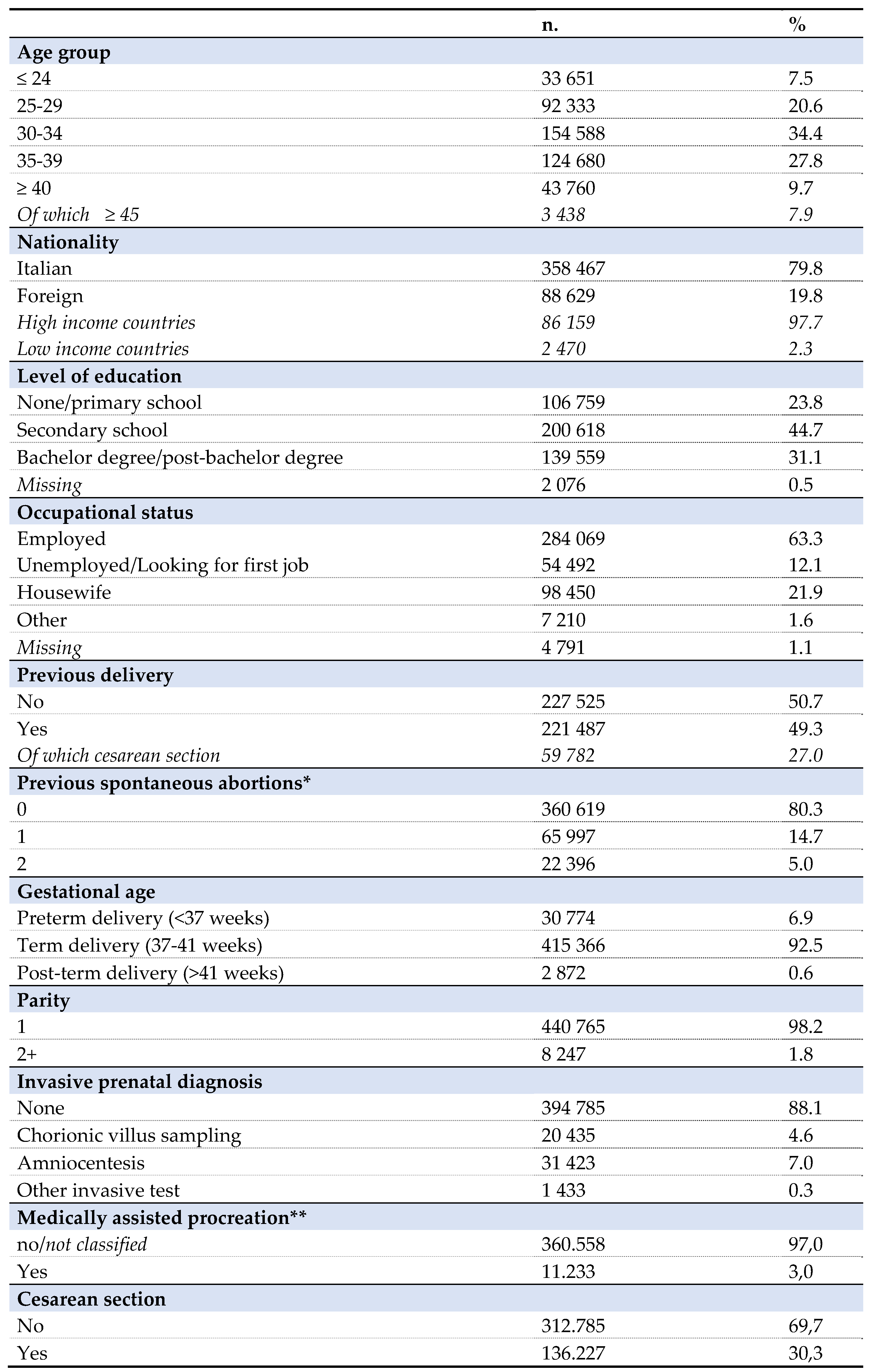

The data describe a cohort of 449.012 women, age ranging from 15 to 49 years old, who had a pregnancy in the period between April 1, 2016 and March 31, 2018 in the eight participating regions, corresponding to 59% of Italian pregnancies [

Table 1, 29].

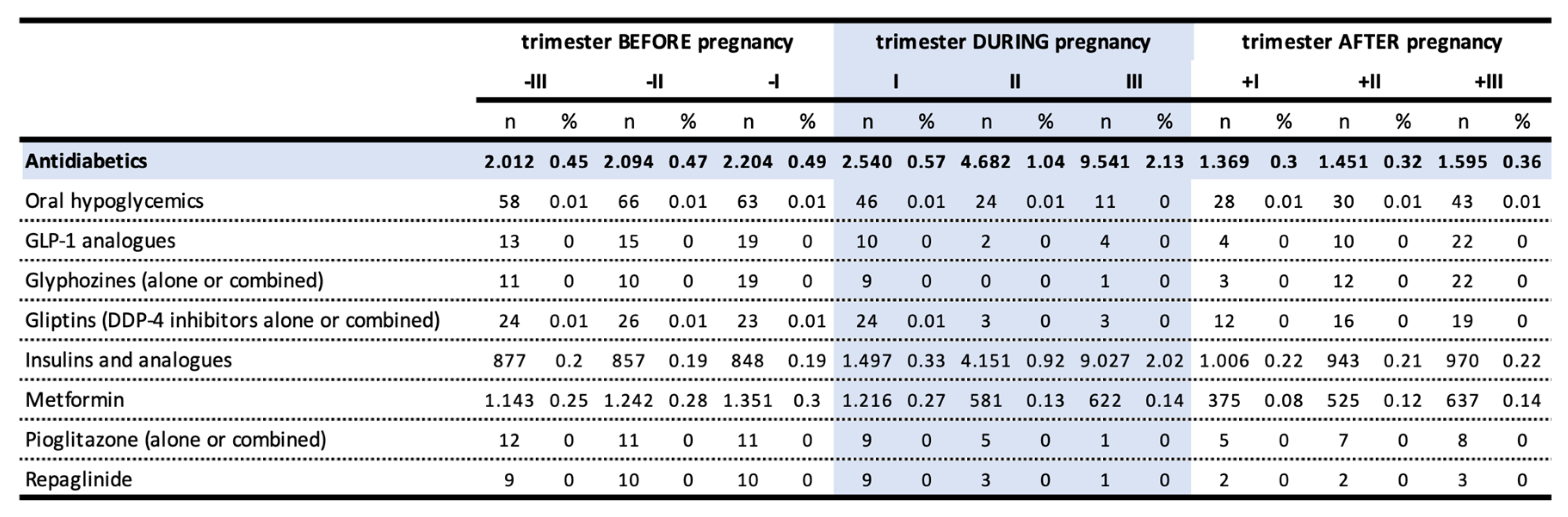

The prevalence of antidiabetics prescription in the pre-conceptional period, representing cases of pre-existing DM, was 0.69%. This value raised to 2.64% during pregnancy, with a growing trend that reached 2.13% in the third trimester, in favor of insulins and its analogues (2%), and reduced to 0.49%1 in the postpartum period. The use of metformin halved over the course of pregnancy going from 0.27% in the first trimester (47,87% of all antidiabetics) to 0.14% in the third trimester (6,52% of all antidiabetics) (

Table 2).

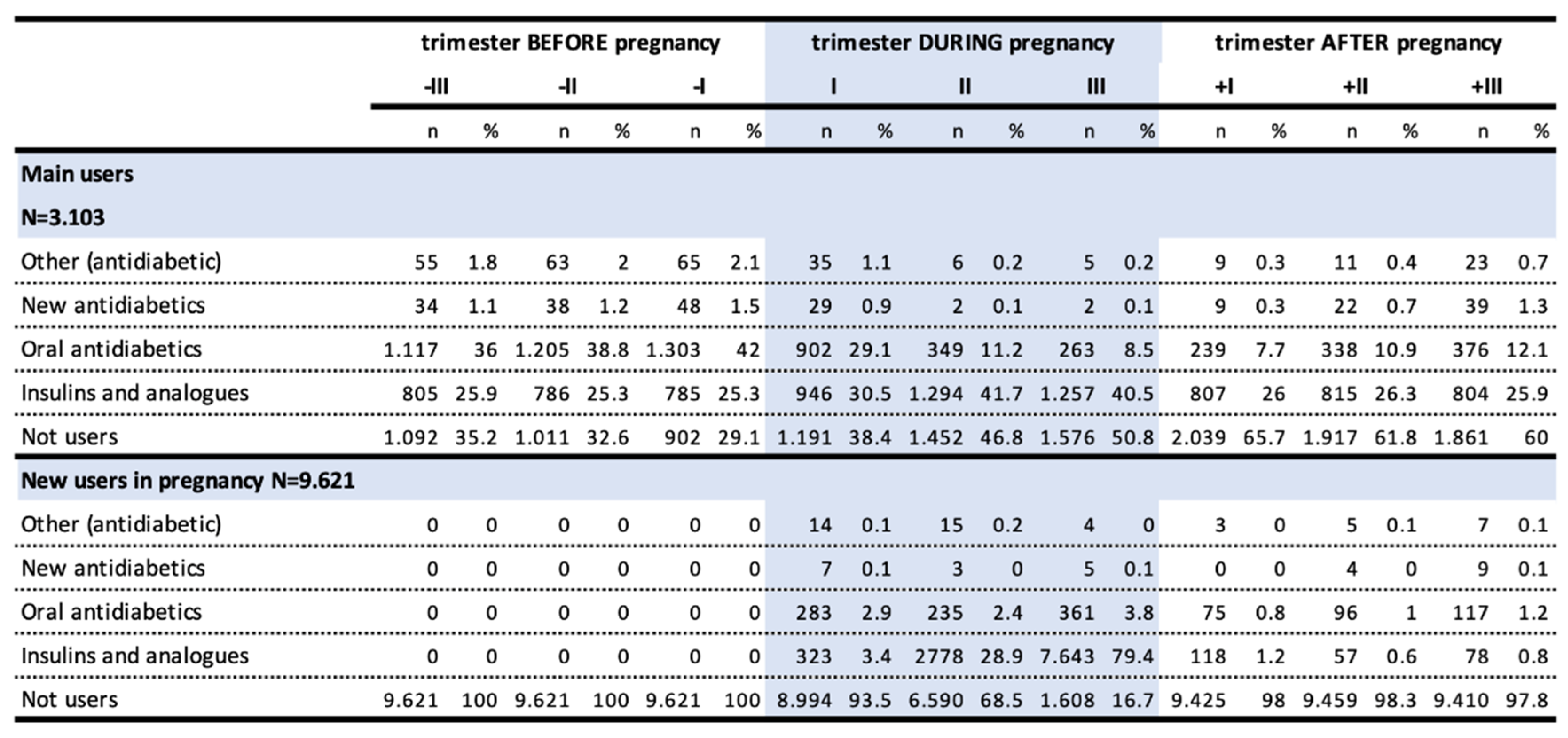

Among users before pregnancy, oral antidiabetics were the most frequently prescribed drugs, with prevalence of use of 36%, 38.8%, and 42% in the third, second and first preconceptional trimesters, respectively, due to the presence of type 2 DM. This was followed by insulins and analogues (25.9%, 25.3% and 25.3%), linked to type 2 and type 1 DM (

Table 3).

While the users of insulin and analogues are mostly persistent in treatment in the trimesters preceding pregnancy, the users of other antidiabetic drugs are less constant. There is a marked increase in the prevalence of insulin use during pregnancy, ranging from 30.5% to 40.5% in the third trimester of gestation, due to an increased risk of GDM but also to the fact that insulin is of choice in pregnancy. After delivery, the prevalence of insulin use returned rapidly to pre-pregnancy levels. In turn, prevalence of oral antidiabetics use, which dropped to 8.5% in pregnancy, did not return to pregestational levels.

The high number of new users during pregnancy was likely due to the onset of GDM. In fact, the use in these women mostly occurred in the second and third trimesters and almost entirely in the category of insulins and analogues, with a prevalence of use of 0.92% and 2.02% in the second and third trimester, respectively. A small but not negligible share of new female users (up to 3.8% in the third trimester) used oral antidiabetics. Over 97% of these women no longer used these drugs after pregnancy.

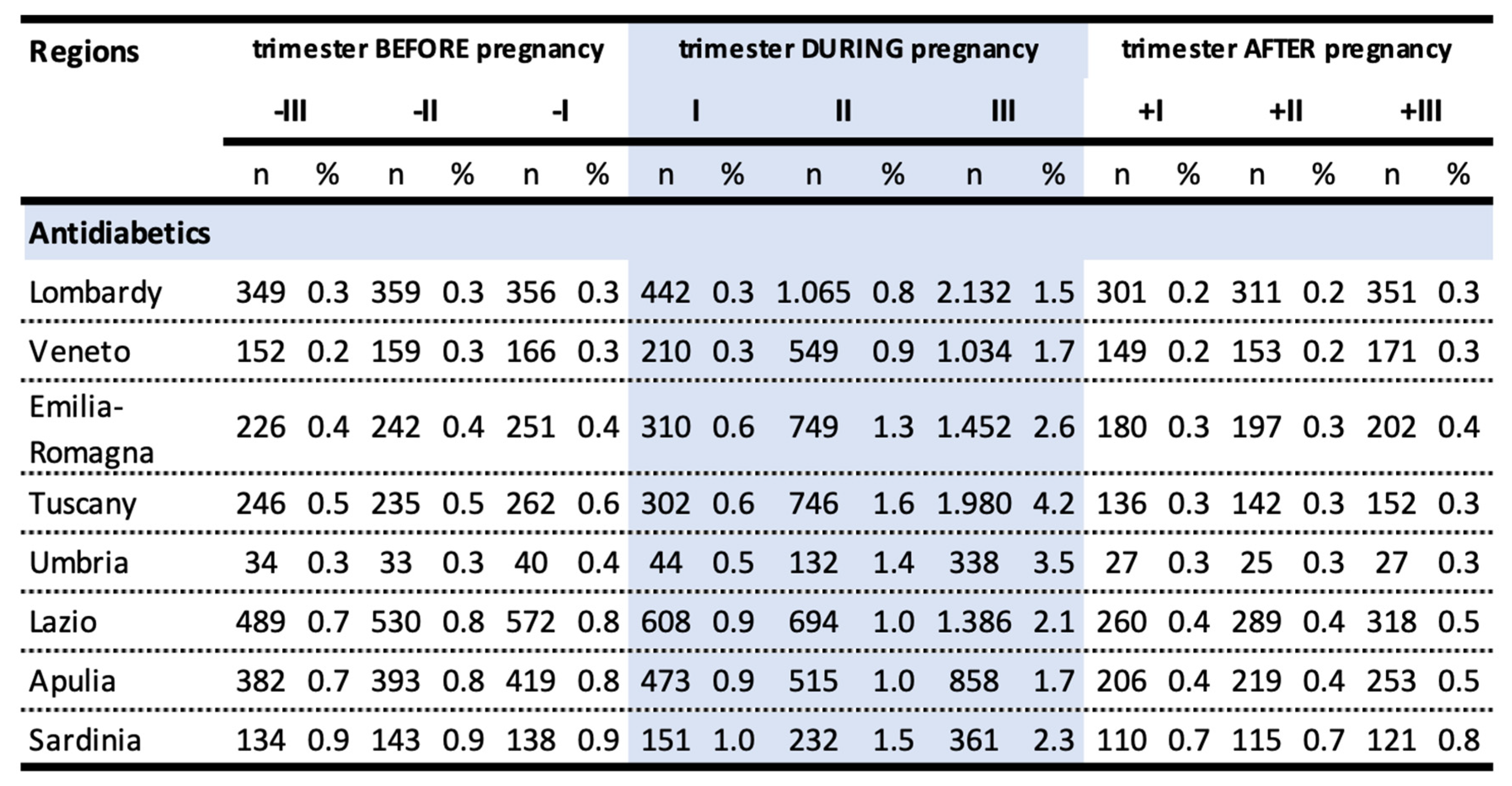

We observed substantial regional variability of antidiabetic drugs prescriptions in the pre-conceptional period and in the first trimester of pregnancy. The largest increase in prevalence of use of antidiabetic drugs occurred in the third trimester of pregnancy in all the regions considered. This increase was particularly marked in Tuscany (4.2%), Umbria (3.5%) and Emilia-Romagna (2.6%), instead, the lowest increases were observed in Lombardy (1.5%), Veneto (1.7%) and Apulia (1.7%) (

Table 4).

The prevalence of use of antidiabetic drugs in the third trimester was significantly different among the regions considered (p-value <0,001). The rate of antidiabetic prescription in Lombardy was 65% lower than in Tuscany (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.33-0.37), 58% lower than in Umbria (OR 0,42, 95%CI 0,37-0,47) and 43% lower than in Emilia-Romagna (OR 0,57, 95% CI 0,53-0,61). Among the considered regions, the fraction of women older than 35 years old appeared to be comparable, being 37.2% in Lombardy, 37% in Veneto, 36,7% in Emilia-Romagna, 37,6% in Tuscany, 36,1% in Umbria, 41,7% in Lazio, 33,2% in Apulia, 42,8% in Sardinia.

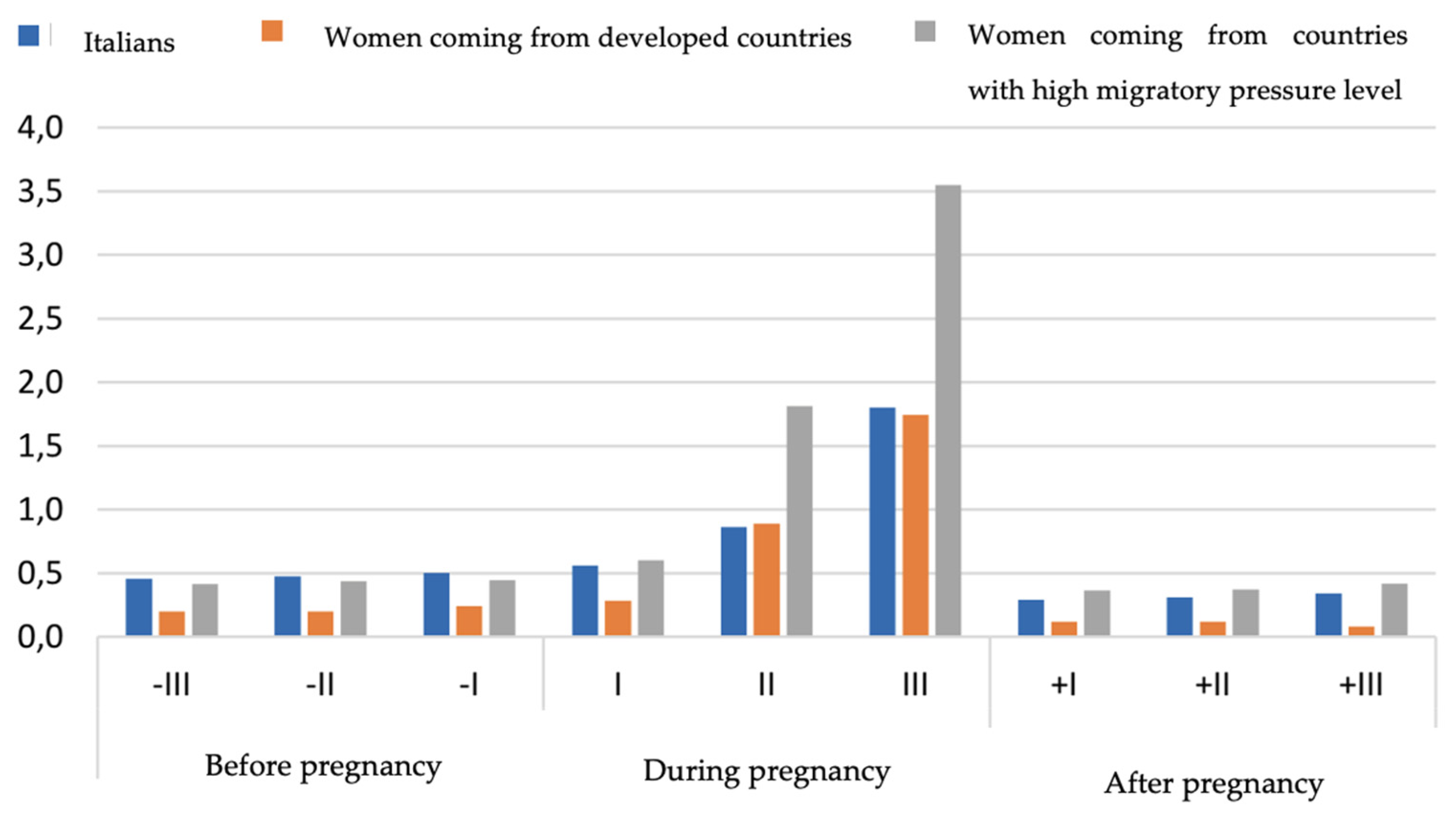

In the end, we compared the consumption of antidiabetics between Italian population and the subgroup of foreign women living in Italy, in particular women coming from developed countries and women coming from countries with high migratory pressure level [

30]. In the three populations analyzed, no differences were observed in the consumption of antidiabetics in the pre-pregnancy period; on the contrary, in the second and third trimester of pregnancy foreign women showed a double proportion of use compared to Italians (second trimester: 1,8% vs 0,9%, third trimester: 3,6% vs 1,8%). After delivery, the consumption returned for all populations to the pre-pregnancy levels (Italians 0,5%; women coming from developed countries 0,1%; women coming from countries with high migratory pressure level 0,6%) (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

The prescribing profile of the various classes of antidiabetics in the Italian MoM-Net cohort seemed to be in line with the Italian standards for the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus which do not recommend the use of oral antidiabetics and non-insulin injection therapy during pregnancy [

31].

We observed that the use of antidiabetics increased with pregnancy reaching its peak in the third trimester (2.13%) in favor of insulins and analogues, a trend which is assignable to the onset of gestational diabetes. These data can be compared with a recently published study describing the use of antidiabetic drugs before, during and after pregnancy in seven European regions over a period of time ranging from 2004 to 2010. The use appeared to be growing during pregnancy: the prevalence of use in the third trimester in the region with the highest prevalence was 2.2%, in line with the data observed in our sample; in the study, however, this value was more than double than the ones registered in the other studied regions [

32]. This growing trend may due both to the higher prevalence of diabetes in the population and to the older age of pregnant women.

Our analyses have shown that a small but not negligible share of new female users used oral antidiabetics (considering women in the third trimester, 2,13% assumed antidiabetics drugs of which up to 3.8% oral ones). This may indicate that, even if the overall prescription pattern seemed to be in line with the Italian guidelines for the treatment of GDM, metformin could have been used not only for type 2 DM but also for off-labels prescriptions and consequently that clinical practice is still heterogeneous [33, 34]. The safety of metformin during pregnancy is still an open question, especially for the lack of data on the long-term outcomes in the offspring. Two retrospective population-based studies from New Zealand and Finland explored the long-term safety profile of metformin in the offspring and no significant differences emerged in the outcomes evaluated [35, 36]. Nevertheless, a recent review reported that, even if the mechanisms remain to be established, metformin is associated to catch-up growth and obesity during childhood, increasing the risk of future cardiometabolic diseases, but they once again highlighted the need for further investigations [

37]. In line with this heterogeneity in practice observed, the assessment of the use of antidiabetics in the eight participating regions revealed a significant variability in the prescription pattern, especially in the third trimester of pregnancy. This variability may be due to different screening policies and, consequently, to different therapeutic choices for glycemic control, as also shown by a recent US study [

38].

We observed a significant regional variability of antidiabetic drugs prescriptions during pregnancy among the eight regions considered. Since the fraction of women older than 35 years old appeared to be comparable, this variability is to be referred to the already known different screening policies and therapeutic choices among the Italian regions.

By comparing the prevalence of use of the antidiabetics among Italian women and foreign women living in Italy coming from developed countries and from countries with a high migratory pressure level, we observed that the latter had a slightly higher proportion of antidiabetic prescriptions in all the studied periods, with a maximum increase during pregnancy. This trend is likely due to a genetic predisposition in developing GDM in women coming from countries with a high migratory pressure level, such as Afro-American, Hispanic, Asian and Native-American women. This genetic predisposition to develop diabetes still stands when the woman has a low BMI [

39]. A 2013 study highlighted differences in the prevalence of the use of antidiabetics according to the country of origin: for example, citizens of Sri Lanka and Bangladesh recorded more than four times higher rates than those of Kosovars, Moldovans and Romanians [

40]. Moreover, women coming from countries with a high migratory pressure level struggled more than Italians in obtaining a clinical evaluation by a general practitioner or a specialized doctor, thus leading to a delay in adequate treatment initiation.

This study has some limitations, the main one being that we could not correlate the characteristics of the population at baseline with the type of diabetes occurred during pregnancy and its severity or the efficacy of the treatment. Also, we could not gather data regarding drug use in pregnancies ended in a spontaneous or induced abortion, as these are not collected in the administrative databases to which we had access. Furthermore, no information on therapeutic indications and pregnancy outcomes for drug prescribing were available, consequently we were not able to investigate the medication use patterns more in depth.

5. Conclusions

To date, the Italian MoM-Net cohort is the biggest and most representative population-based study regarding the prevalence of antidiabetic drugs use during pregnancy in Italy. Concerning the data presented in this work, the prescription pattern of antidiabetic drugs in Italy mostly includes medicines that are safe to take in pregnancy.

Given the limited information, the performed analyses provide an updated and exhaustive overview on antidiabetic drugs prescription pattern in Italian pregnant women, which can help to identify critical aspects in the management of GDM in Italy.

We believe that further descriptive studies led by the MoM-Net group and coordinated at a national level could be successful in improving the current Italian clinical practice regarding treatment choices in pregnancy while also playing an important role in promoting standardization of the prescriptions between the different regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Locatelli, Ornaghi and Terzaghi; methodology, Fortinguerra, Belleudi and Trotta; data curation, Poggi, Perna and Terzaghi.; writing—original draft preparation, Locatelli, Ornaghi and Terzaghi.; writing—review and editing, Fortinguerra and Belleudi.; supervision, Trotta.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the datasets contained only the information strictly necessary to conduct the pre-planned analyses, without sensitive data which were previously anonymized at regional level by the data owner, in compliance with current Italian legislation on privacy

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Italian regions participating to MoM-Net group (Lombardy, Veneto, Emilia Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, Lazio, Puglia, Sardinia) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license (as by third-party sources) for the current study, and so are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors with permission of Italian regions, which are the data owner. The non-author contact information to which data requests may be sent is: ti.vog.afia@demso.oiciffu

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- NICE. Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period NICE guideline (2015).

- ISS. Diabete gestazionale (2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gestational diabetes. 2019. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/gestational.html.

- Lisa Hartling & et al. Benefits and Harms of Treating Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the National Institutes of Health Office of Medical Applications of Research. Ann Intern Med. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Crowther & at al. Tighter or less tight glycaemic targets for women with gestational diabetes mellitus for reducing maternal and perinatal morbidity: A stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised trial. [CrossRef]

- Wenrui Ye & et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2022. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 14. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: standards of medical care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020 (Suppl1): S183-92. [CrossRef]

- Alpesh Goyal, Yashdeep Gupta, Rajiv Singla, Sanjay Kalra, Nikhil Tandon. American Diabetes Association ‘‘Standards of Medical Care—2020 for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus’’: A Critical Appraisal.

- Rachel K. Harrison, Meredith Cruz, Ashley Wong, Caroline Davitt and Anna Palatnik. The timing of initiation of pharmacotherapy for women with gestational diabetes mellitus. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Anna Palatnik, Rachel K. Harrison, Rebekah J. Walker, Madhuli Y Thakkar, Leonard E. Egede. Maternal racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic threshold for pharmacotherapy initiation for gestational diabetes. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lanlan Guo, Jing Ma, Jia Tang & et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of metformin, glyburide and insulin in treating gestational diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Rowan, W. M. Hague, W. Gao, M. R. Battin, M. P Moore. Metformin versus insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Brown J. & et al. Insulin for the treatment of women with gestational diabetes (review) (2017). [CrossRef]

- Brown J & et al. Oral anti-diabetic pharmacological therapies for the treatment of women with gestational diabetes (review) (2017). [CrossRef]

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, ACOG Practice Bulletin. 2018.

- Summary of Revisions: Standard of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 2023;46(Suppl.1):S5-S9 | . [CrossRef]

- SMFM Statement: Pharmacological treatment of gestational diabetes. MAY 2018 a 2018 Published by Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period. NICE guideline [NG3], published 25 February 2015, last updated 16 December 2020.

- Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks DA, et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: A pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131:S173-211. [CrossRef]

- AIFA (n.d.) https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2022/12/14/291/sg/pdf.

- AIFA-Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (2022) Modifica dell’autorizzazione all’immissione in commercio del medicinale per uso umano, a base di metformina cloridrato, <<Glucophage>>. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2022/10/18/244(sg/pdf.

- Brand KMG, Saarelainen L, Sonajalg J, Boutmy E, Foch C, Vääräsmäki M et al (2022) Metformin in pregnancy and risk of adverse long-term outcomes: a register-based cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 10:e002363. [CrossRef]

- Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris G, Benson G, Brown FM, Freeman R, et al. (2022) 15. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: standards of medical care in diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 45:S232–S243. [CrossRef]

- Position paper of the Italian Association of Medical Diabetologists (AMD), Italian Society of Diabetology (SID) and the Italian Study Group of Diabetes in pregnancy: Metformin use in pregnancy. Laura Sciacca, Cristina Bianchi, et al. 2023 Jul 4: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00592-023-02137-5. [CrossRef]

- Gini R, Sturkenboom MCJ, Sultana J, Cave A, Landi A, Pacurariu A, et al. Different Strategies to Execute Multi-Database Studies for Medicines Surveillance in Real-World Setting: A Reflection on the European Model. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2020;108. [CrossRef]

- Schneeweiss S, Brown JS, Bate A, Trifirò G, Bartels DB. Choosing Among Common Data Models for Real-World Data Analyses Fit for Making Decisions About the Effectiveness of Medical Products. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2020;107. [CrossRef]

- Belleudi V, Fortinguerra F, Poggi FR, Perna S, Bortolus R, Donati S, et al. The Italian Network for Monitoring Medication Use During Pregnancy (MoM-Net): Experience and Perspectives. Front Pharmacol [Internet] 2021;12:699062. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34248644. [CrossRef]

- Belleudi V, Fortinguerra F, Poggi FR, Perna S, Bortolus R, Donati S, Clavenna A, Locatelli A, Davoli M, Addis A, Trotta F; MoM-Net group. The Italian Network for Monitoring Medication Use During Pregnancy (MoM-Net): Experience and Perspectives. Frontiers. 2021 Jun 23; [CrossRef]

- Fortinguerra F, Belleudi V, Poggi FR, Perna S, Bortolus R, Donati S, D'Aloja P, Da Cas R, Clavenna A, Locatelli A, Addis A, Davoli M, Trotta F; MoM-Net group. Monitoring medicine prescriptions before, during and after pregnancy in Italy. PLoS One. 2023 Jun 15;18(6):e0287111. [CrossRef]

- D'Aloja P, Da Cas R, Belleudi V, Fortinguerra F, Poggi FR, Perna S, Trotta F, Donati S, MoM-Net Group. Drug Prescriptions among Italian and Immigrant Pregnant Women Resident in Italy: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Apr 1;19(7):4186. [CrossRef]

- Associazione Medici Diabetologi (AMD) - Società Italiana di Diabetologia (SID). Standard italiani per la cura del diabete mellito 2018 [https://aemmedi.it/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/AMD-Standard-unico1.pdf] (ultimo accesso 27/07/2020).

- Charlton RA, Klungsøyr K, Neville AJ, Jordan S, Pierini A, Berg LTW de J den, et al. Prescribing of Antidiabetic Medicines before, during and after Pregnancy: A Study in Seven European Regions. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0155737. [CrossRef]

- Lende M, Rijhsinghani A. Gestational Diabetes: Overview with Emphasis on Medical Management. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Dec 21;17(24):9573. PMID: 33371325; PMCID: PMC7767324. [CrossRef]

- Picón-César MJ, Molina-Vega M, Suárez-Arana M, González-Mesa E, Sola-Moyano AP, Roldan-López R, Romero-Narbona F, Olveira G, Tinahones FJ, González-Romero S. Metformin for gestational diabetes study: metformin vs insulin in gestational diabetes: glycemic control and obstetrical and perinatal outcomes: randomized prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Nov;225(5):517.e1-517.e17. Epub 2021 Apr 19. PMID: 33887240. [CrossRef]

- Landi SN, Radke S, et al. Association of long-term child growth and developmental outcomes with metformin vs insulin treatment for gestational diabetes. JAMA Pediatr 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kerstin M G Brand et al. “Metformin in pregnancy and risk of adverse long-term outcomes: a register based cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Manon D Owen et al. “Interaction between Metformin, Folate and Vitamin B12 and the potential impact on fetal growth and long-term metabolic health in diabetic pregnancies”. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Davitt, K. E. Flynn, R. K. Harrison, et al. Current practices in gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis and management in the United States: survey of a maternal-fetal medicine specialists. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ménard V, Sotunde OF, Weiler HA. Ethnicity and Immigration Status as Risk Factors for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, Anemia and Pregnancy Outcomes Among Food Insecure Women Attending the Montreal Diet Dispensary Program. Can J Diabetes 2020;44(2):139-45. [CrossRef]

- Andretta M, Cinconze E, Costa E, et al. Farmaci e immigrati. Rapporto sulla prescrizione farmaceutica in un paese multietnico. Roma: Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore, 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).