Submitted:

14 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Key points

- -

- The study included 79,603 Asian patients with chronic progressive diseases.

- -

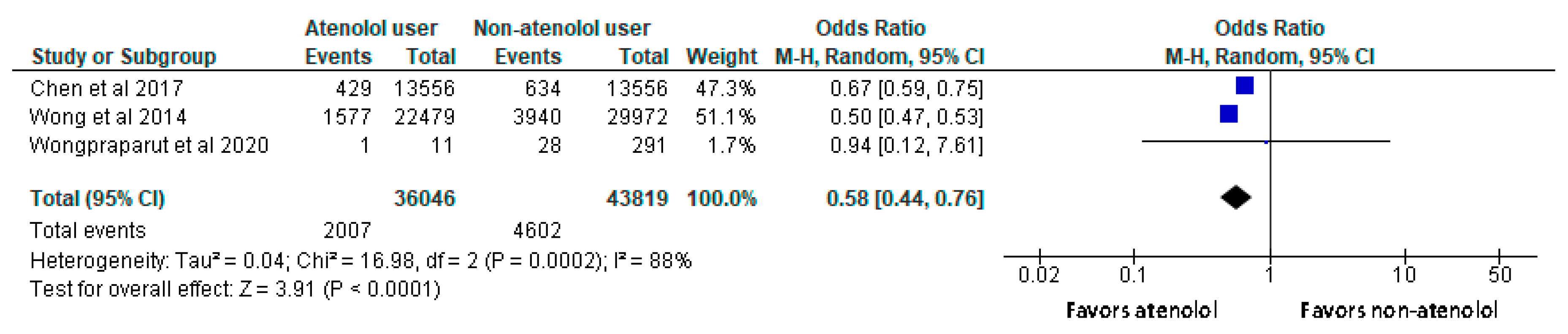

- Patients using atenolol had lower all-cause mortality rates compared to non-users with a significant difference.

- -

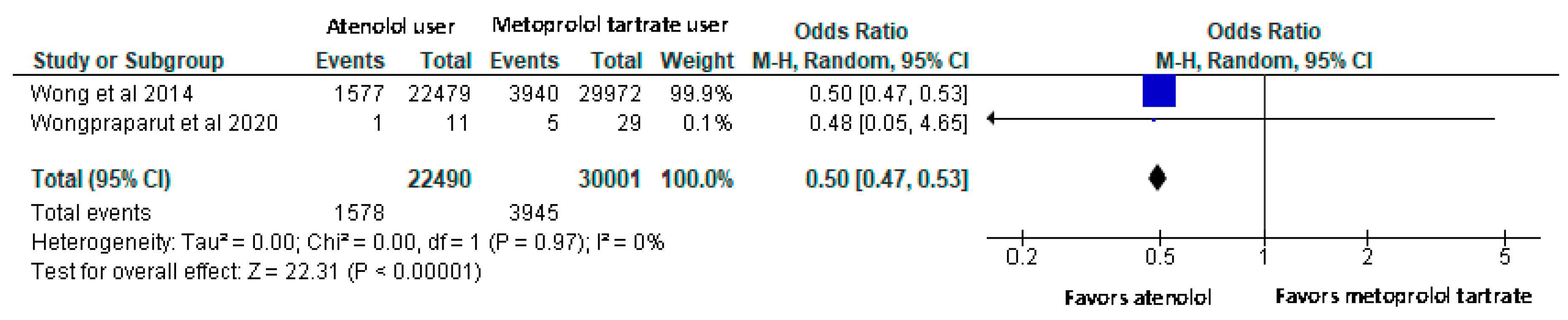

- All-cause mortality rate was also lower among atenolol users compared to metoprolol tartrate users with a significant difference.

1. Introduction

Rationale

Objectives

2. Materials and methods

Eligibility criteria and information sources

Search strategy and selection process

Data Collection and Extraction

Data items

Assessment of risk of bias

Effect measures and synthesis method

Certainty assessment

Dealing with Heterogeneity

3. Results

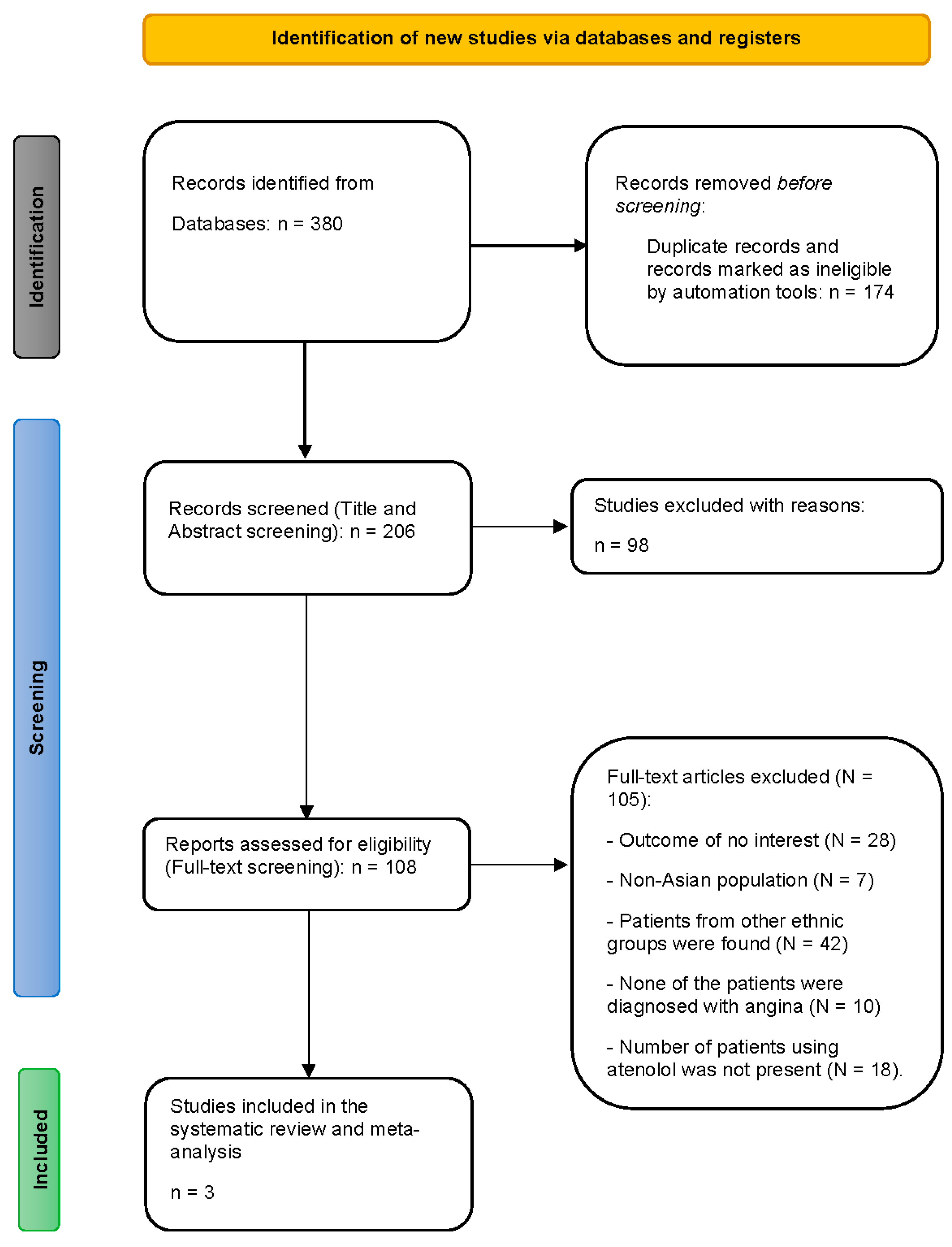

Study selection

Study characteristics

Results of individual studies

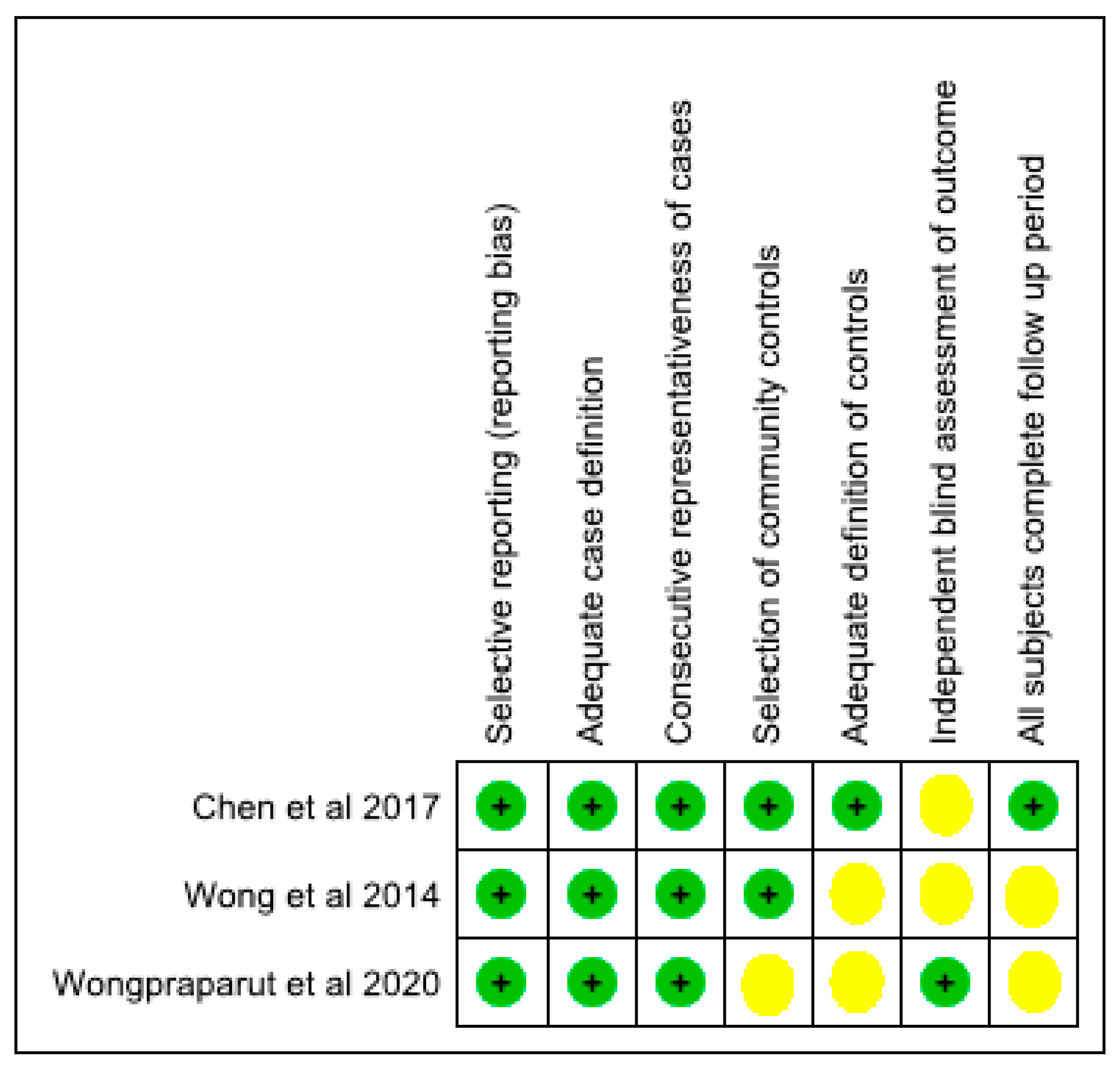

Risk of bias among the included studies including reporting bias

Results of syntheses

Certainty of evidence

4. Discussion

Potential bias encountered during the review process

Registration and protocol

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Data availability

- -

- Wong MC, Tam WW, Lao XQ, Wang HH, Kwan MW, Cheung CS, Tong EL, Cheung NT, Yan BP, Yu CM, Griffiths SM. The effectiveness of metoprolol versus atenolol on prevention of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a large Chinese population: a cohort study. International journal of cardiology. 2014 Aug 20;175, 425-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.06.009

- -

- Chen RJ, Chu H, Tsai LW. Impact of Beta-Blocker Initiation Timing on Mortality Risk in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017 Jan 10;6, e004392. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.004392

- -

- Wongpraparut N, Siwamogsatham S, Thongsri T, Ngamjanyaporn P, Phrommintikul A, Jirajarus K, Tangcharoen T, Bhumimuang K, Kaewsuwanna P, Krittayaphong R, Pongakasira R. Impact of guideline-recommended versus non-guideline-recommended β-blocker and Doppler echocardiographic parameters on 1-year mortality in Thai ischemic cardiomyopathy patients: A prospective multicenter registry. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2020 Dec;20:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-01311-4

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of interest disclosure

Clinical trials registration number

PROSPERO registration number

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

List of abbreviation

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| SCAI | Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| SIHR | Stable Ischemic Heart Disease |

| HDL-C | High Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| ESRD | End-Stage Renal Disease |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

References

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S. Antihypertensive and cardioprotective effects of three generations of beta-adrenergic blockers: an historical perspective. Hospital Practice. 2022, 50, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivas, D.; Raposeiras, S. Comments on the ESC 2022 guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Revista Espanola de Cardiologia (English ed.). 2022 Nov 12:S1885-5857.

- Nan, Y.; Jia, F.; Du, X.; Mei, Z. Beta-blocker exposure for short-term outcomes following non-cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of observational studies. International Journal of Surgery. 2020, 76, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assimon, M.M.; Brookhart, M.A.; Fine, J.P.; Heiss, G.; Layton, J.B.; Flythe, J.E. A comparative study of carvedilol versus metoprolol initiation and 1-year mortality among individuals receiving maintenance hemodialysis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2018, 72, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.H.; Lin, Y.T.; Liu, J.S.; Tsai, Y.C.; Kuo, M.C.; Chiu, Y.W.; Hwang, S.J.; Carrero, J.J. Comparative effectiveness of bisoprolol and carvedilol among patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Clinical Kidney Journal. 2021, 14, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schupp, T.; Behnes, M.; Abumayyaleh, M.; Weidner, K.; Rusnak, J.; Mashayekhi, K.; Bertsch, T.; Akin, I. Carvedilol versus Metoprolol in Patients with Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2022, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHabeeb, W.; Mrabeti, S.; Abdelsalam, A.A. Therapeutic properties of highly selective β-blockers with or without additional vasodilator properties: focus on bisoprolol and nebivolol in patients with cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 2022, 36, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, B.K.; Park, S.; Lee, S.H.; Ko, Y.G.; Choi, D.; Ahn, H.A.; Joung, S.H.; Park, Y.M.; Hong, M.K. Atenolol versus Bisoprolol after Acute Myocardial Infarction.

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; MacLaughlin, E.J. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018, 71, e127–e248. [Google Scholar]

- Aronow, W.S.; Fleg, J.L.; Pepine, C.J.; Artinian, N.T.; Bakris, G.; Brown, A.S.; Ferdinand, K.C.; Forciea, M.A.; Frishman, W.H.; Jaigobin, C.; Kostis, J.B. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension.

- Jackson, G.J.; Schwartz, J.A.; Kates, R.E.; Winchester, M.A.; Harrison, D.C. Atenolol: once-daily cardioselective beta blockade for angina pectoris. Circulation. 1980, 61, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.B.; Jackson, G.; Kates, R.E.; Harrison, D.C. Long-term benefit of cardioselective beta blockade with once-daily atenolol therapy in angina pectoris. American Heart Journal. 1981, 101, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesta, R.; Campbell, D.; Venturini, C.; Faconti, L.; Singh, S.; Irvin, M.R.; Cooper-DeHoff, R.M.; Johnson, J.A.; Turner, S.T.; Arnett, D.K.; Weale, M.E. Gene variants at loci related to blood pressure account for variation in response to antihypertensive drugs between black and white individuals: genomic precision medicine may dispense with ethnicity. Hypertension. 2019, 74, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filigheddu, F.; Argiolas, G.; Degortes, S.; Zaninello, R.; Frau, F.; Pitzoi, S.; Bulla, E.; Bulla, P.; Troffa, C.; Glorioso, N. Haplotypes of the adrenergic system predict the blood pressure response to β-blockers in women with essential hypertension. Pharmacogenomics. 2010, 11, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonough, C.W.; Gillis, N.K.; Alsultan, A.; Chang, S.W.; Kawaguchi-Suzuki, M.; Lang, J.E.; Shahin, M.H.; Buford, T.W.; El Rouby, N.M.; Sá, A.C.; Langaee, T.Y. Atenolol induced HDL-C change in the pharmacogenomic evaluation of antihypertensive responses (PEAR) study. PloS one. 2013, 8, e76984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB). rs8068318 variant (TBX2 gene). Available at https://www.pharmgkb.org/variant/PA166199006. Accessed date 21 March 2023.

- Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB). rs2144300 variant (GALNT2 gene). Available at https://www.pharmgkb.org/variant/PA166153674. Accessed date 21 March 2023.

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Bmj. 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.C.; Tam, W.W.; Lao, X.Q.; Wang, H.H.; Kwan, M.W.; Cheung, C.S.; Tong, E.L.; Cheung, N.T.; Yan, B.P.; Yu, C.M.; Griffiths, S.M. The effectiveness of metoprolol versus atenolol on prevention of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a large Chinese population: a cohort study. International journal of cardiology. 2014, 175, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Chu, H.; Tsai, L.W. Impact of Beta-Blocker Initiation Timing on Mortality Risk in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017, 6, e004392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpraparut, N.; Siwamogsatham, S.; Thongsri, T.; Ngamjanyaporn, P.; Phrommintikul, A.; Jirajarus, K.; Tangcharoen, T.; Bhumimuang, K.; Kaewsuwanna, P.; Krittayaphong, R.; Pongakasira, R. Impact of guideline-recommended versus non-guideline-recommended β-blocker and Doppler echocardiographic parameters on 1-year mortality in Thai ischemic cardiomyopathy patients: A prospective multicenter registry. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Desai, H.; Sharm, N.; Laddha, M.; Hansora, K.; Vazirani, P. To Evaluate the'Real World'Clinical Performance of Bisoprolol in Post-Myocardial Infarction with Left Ventricular Dysfunction: Tenacity Study. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2022, 70, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.W.; Chu, T.T.; Ho, C.S.; Kong, A.P.; Tomlinson, B.; Zeng, W. Influence of CYP2D6 and CYP3A5 Polymorphisms on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Bisoprolol in Hypertensive Chinese Patients. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021, 8, 683498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.; Costa, B.; Vale, N. New Data for Nebivolol after In Silico PK Study: Focus on Young Patients and Dosage Regimen. Pharmaceutics. 2022, 14, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabidó, M.; Thilo, H.; Guido, G. Long-term effectiveness of bisoprolol in patients with angina: a real-world evidence study. Pharmacological Research. 2019, 139, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlberg, B.; Samuelsson, O.; Lindholm, L.H. Atenolol in hypertension: is it a wise choice? The lancet. 2004, 364, 1684–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, J.; Tamis-Holland, J.; Bangalore, S.; Bates, E.; Beckie, T.; Bischoff, J.; Bittl, J.; Cohen, M.; DiMaio, J.; Don, C.; Fremes, S.; Gaudino, M.; Goldberger, Z.; Grant, M.; Jaswal, J.; Kurlansky, P.; Mehran, R.; Metkus, T., Jr.; Nnacheta, L.; Rao, S.; et al. . 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e18–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, H.; Suh, Y.; Kim, G.S.; Ko, Y.G.; Hong, M.K. Clinical impact of beta blockers in patients with myocardial infarction from the Korean National Health Insurance Database. Korean Circulation Journal. 2020, 50, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, O.Y.; Molony, D.; Corban, M.T.; Rasoul-Arzrumly, E.; Maynard, C.; Eshtehardi, P.; Dhawan, S.; Timmins, L.H.; Piccinelli, M.; Ahn, S.G.; Gogas, B.D. Comprehensive Assessment of Coronary Plaque Progression With Advanced Intravascular Imaging, Physiological Measures, and Wall Shear Stress: A Pilot Double-Blinded Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial of Nebivolol Versus Atenolol in Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016, 5, e002764. [Google Scholar]

- The Dutch TIA Trial Study Group. Trial of secondary prevention with atenolol after transient ischemic attack or nondisabling ischemic stroke. Stroke 1993, 24, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MRC Working Party. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ 1992, 304, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlöf, B.; Devereux, R.B.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the losartan intervention for endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet 2002, 359, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchetti, A.; Bond, M.G.; Henning, M.; et al. Calcium antagonist lacidipine slows down progression of asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis. Principal results of the European lacidipine study on atherosclerosis (ELSA), a randomized, double-blind, long-term trial. Circulation 2002, 106, 2422–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.Q.; Mao, Y.M.; Wu, J.; Fang, X.Y.; Li, B.Z. Cultural Epidemiology in China. Progress in China. Epidemiology 2023, 1, 401–418. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Bratzke, L.; Baumann, L.C. Helping persons with multiple chronic conditions overcome barriers to self-management. The Nurse Practitioner. 2021, 46, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-González, X.; Cubo, E.; Simón-Vicente, L.; Mariscal, N.; Alcaraz, R.; Aguado, L.; Rivadeneyra-Posadas, J.; Sanz-Solas, A.; Saiz-Rodríguez, M. Pharmacogenetics in the Treatment of Huntington’s Disease: Review and Future Perspectives. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023, 13, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacabelos, R. Pharmacogenetic considerations when prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2020, 16, 673–701. [Google Scholar]

- Kamide, K.; Asayama, K.; Katsuya, T.; Ohkubo, T.; Hirose, T.; Inoue, R.; Metoki, H.; Kikuya, M.; Obara, T.; Hanada, H.; Thijs, L. Genome-wide response to antihypertensive medication using home blood pressure measurements: a pilot study nested within the HOMED-BP study. Pharmacogenomics. 2013, 14, 1709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB). rs588076 variant (PICALM gene). Available at https://www.pharmgkb.org/variant/PA166154284. Accessed date 21 March 2023.

- Magvanjav, O.; Gong, Y.; McDonough, C.W.; Chapman, A.B.; Turner, S.T.; Gums, J.G.; Bailey, K.R.; Boerwinkle, E.; Beitelshees, A.L.; Tanaka, T.; Kubo, M. Genetic Variants Associated With Uncontrolled Blood Pressure on Thiazide Diuretic/β-Blocker Combination Therapy in the PEAR (Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses) and INVEST (International Verapamil-SR Trandolapril Study) Trials. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017, 6, e006522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB). rs261316 variant (ALDH1A2 gene). Available at https://www.pharmgkb.org/variant/PA166179574. Accessed date 21 March 2023.

- Hallberg, P.; Karlsson, J.; Lind, L.; Michaëlsson, K.; Kurland, L.; Kahan, T.; Malmqvist, K.; Öhman, K.P.; Nyström, F.; Liljedahl, U.; Syvänen, A.C. Gender-specific association between preproendothelin-1 genotype and reduction of systolic blood pressure during antihypertensive treatment---results from the Swedish irbesartan left ventricular hypertrophy investigation versus atenolol (SILVHIA). Clinical cardiology. 2004, 27, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB). rs5370 variant (EDN1 gene). Available at https://www.pharmgkb.org/variant/PA166156901. Accessed date 21 March 2023.

- Gong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Beitelshees, A.L.; McDonough, C.W.; Langaee, T.Y.; Hall, K.; Schmidt, S.O.; Curry, R.W., Jr; Gums, J.G.; Bailey, K.R.; Boerwinkle, E. Pharmacogenomic genome-wide meta-analysis of blood pressure response to β-blockers in hypertensive African Americans. Hypertension. 2016, 67, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB). rs1367094 variant (ZMAT4 gene). Available at https://www.pharmgkb.org/variant/PA166157555. Accessed date 21 March 2023.

| Author | Title | Study design | Setting/ duration | Aim | Participants | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wong et al. (2014) | The effectiveness of metoprolol versus atenolol on prevention of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a large Chinese population: A cohort study | Retrospective cohort study | The study conducted in Hong Kong between 2001 and 2010. | Compared the incidence of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality between patients newly prescribed atenolol vs. metoprolol tartrate users | Hypertensive patients using atenolol (N=22,479) or metoprolol tartrate (N=29,972). | 7.0% and 13.1% died of any causes among atenolol and metoprolol users, respectively (p <0.005). The incidence of cardiovascular mortality among atenolol users was lower than metoprolol users (1.4% vs. 3.7%, p < 0.001). |

| Chen et al. (2017) | Impact of Beta-Blocker Initiation Timing on Mortality Risk in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus Undergoing Non-cardiac Surgery: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study | Retrospective cohort study | The study conducted using the Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database between 2000 and 2011. | To explore the role of perioperative initiation of beta-blockers, including atenolol, in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing non-cardiac surgery. | Diabetic patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery using atenolol (N=13,556) or non-atenolol matched controls (N=13,556). matched controls. | Beta-blocker users were associated with lower risks of in-hospital (odds ratio 0.75, 95% CI 0.68–0.82) and 30-day (odds ratio 0.75, 95% CI 0.70–0.81) mortality. |

| Wongpraparut et al. (2020) | Impact of guideline-recommended versus non-guideline-recommended β-blocker and Doppler echocardiographic parameters on 1-year mortality in Thai ischemic cardiomyopathy patients: A prospective multicenter registry | Prospective cohort study | The study conducted in 9 medical centers located across Thailand from December 2014 to November 2015. | To determine and to identify factors that significantly predicts 1-year mortality of Thai patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy | Patients with coronary artery disease using atenolol (N=11), metoprolol tartrate (N=29), or non-atenolol beta-blocker agent (N= 291). | The use of non-guideline-recommended beta-blockers (atenolol, metoprolol tartrate, and propranolol) rather than guideline recommended beta-blockers (Carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, nebivolol, and bisoprolol) were associated with increased with 1-year mortality. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).