Submitted:

21 September 2023

Posted:

22 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

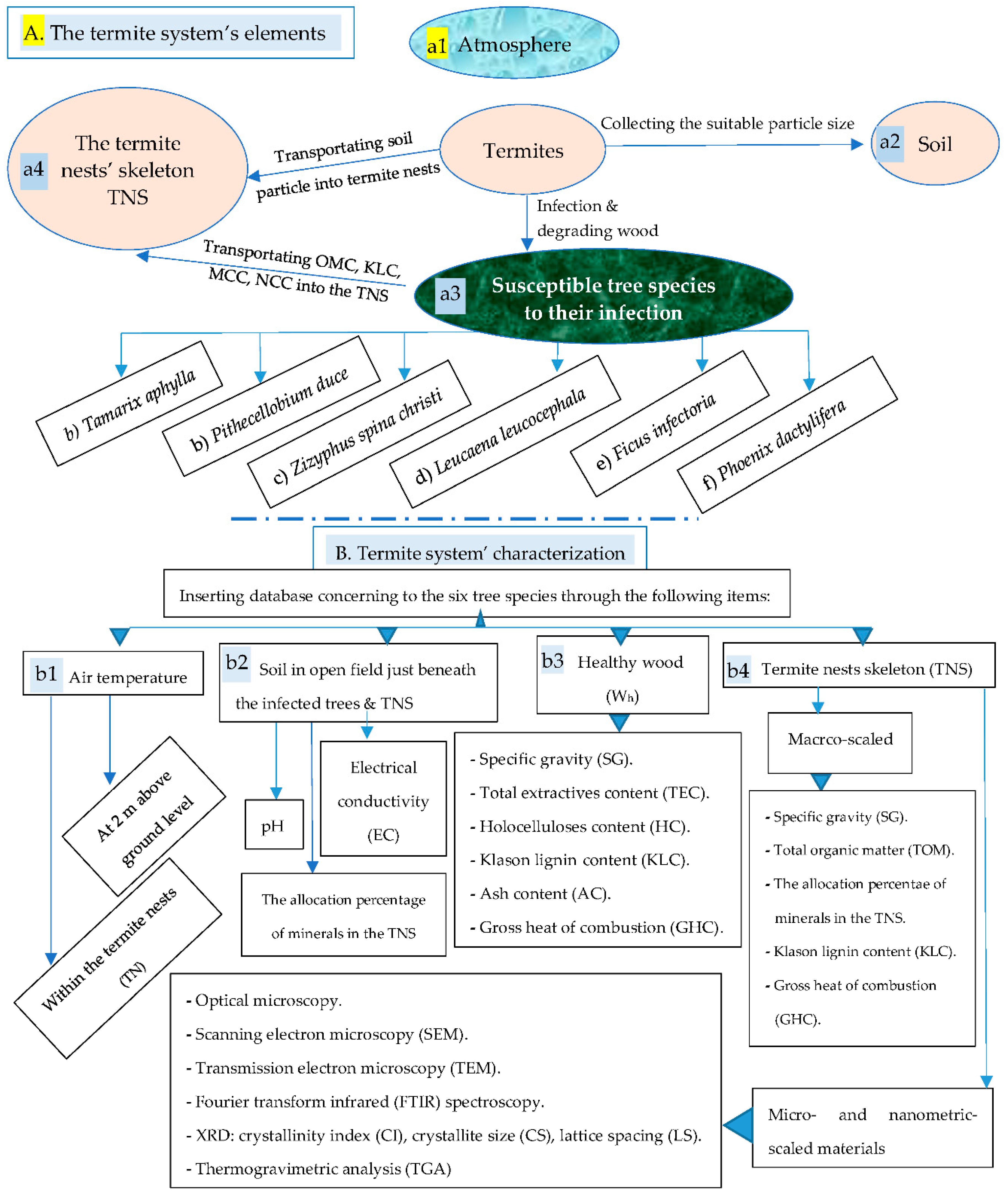

2.1. Management Plan

2.2. Collection and Analyzing the Termite System’s Elements

2.2.1. The Atmospheric Air Temperature

2.2.2. Soil

- I.

- Electrical Conductivity (EC)

- II.

- The pH

- III.

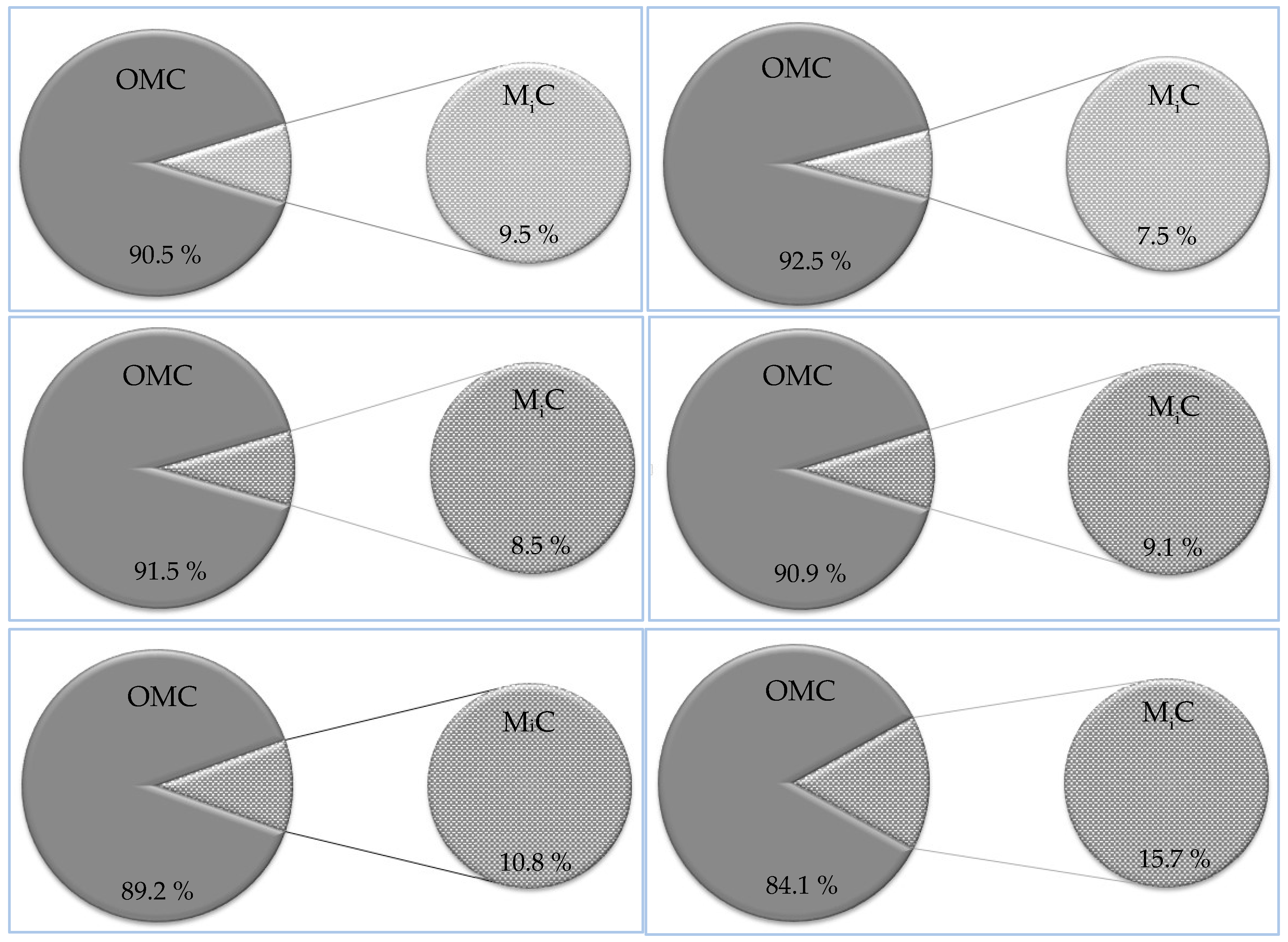

- Total Organic Matter Content (OMC) of Soil

- V.

- Total Minerals Content in Soil (open field)

2.2.3. The Healthy Wood (Wh)

- I.

- The Specific Gravity (SG) of the Wh

- II.

- Total Extractives Content (TEC) of the Wh

- III.

- Holocelluloses Content (HC) of the Wh

- IV.

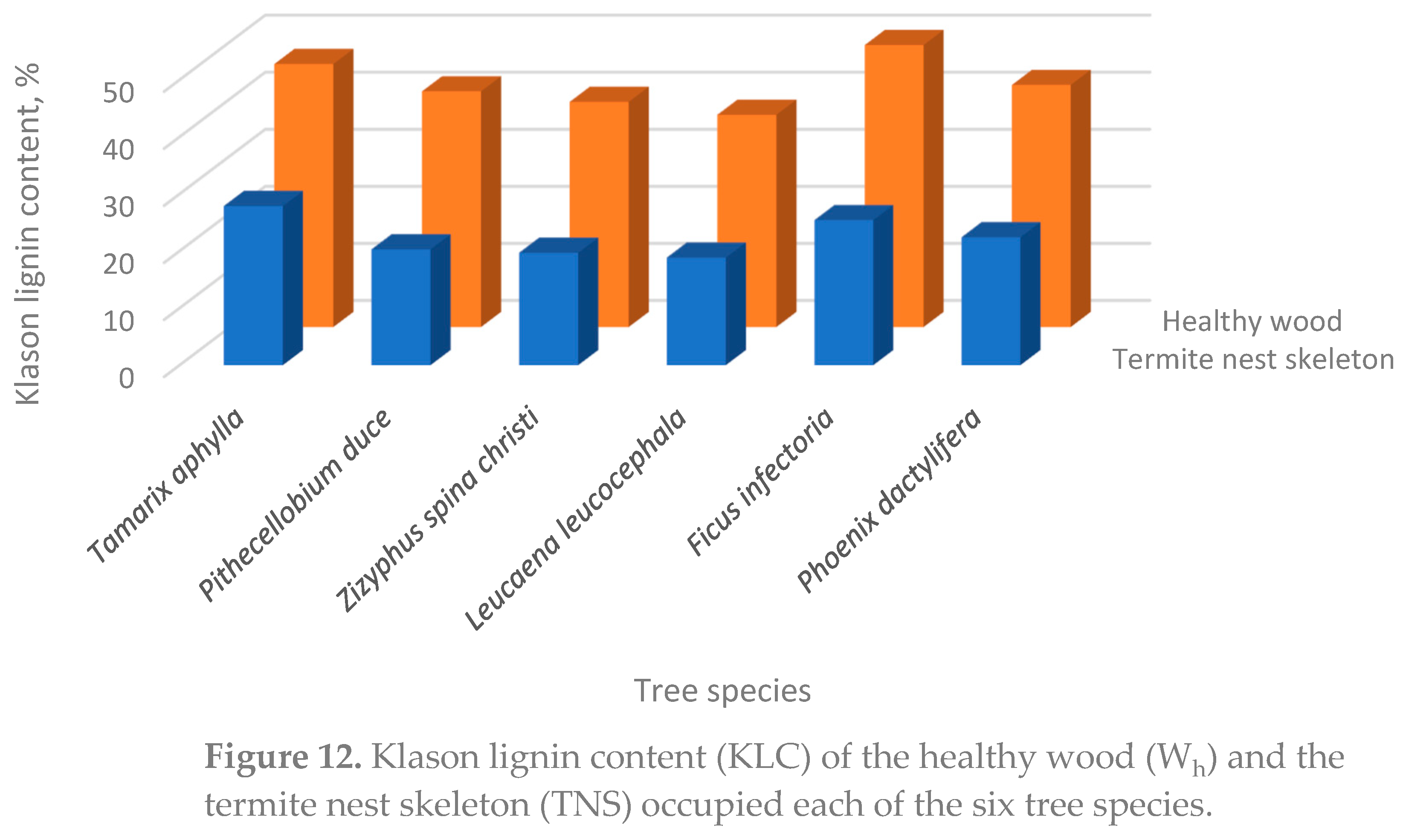

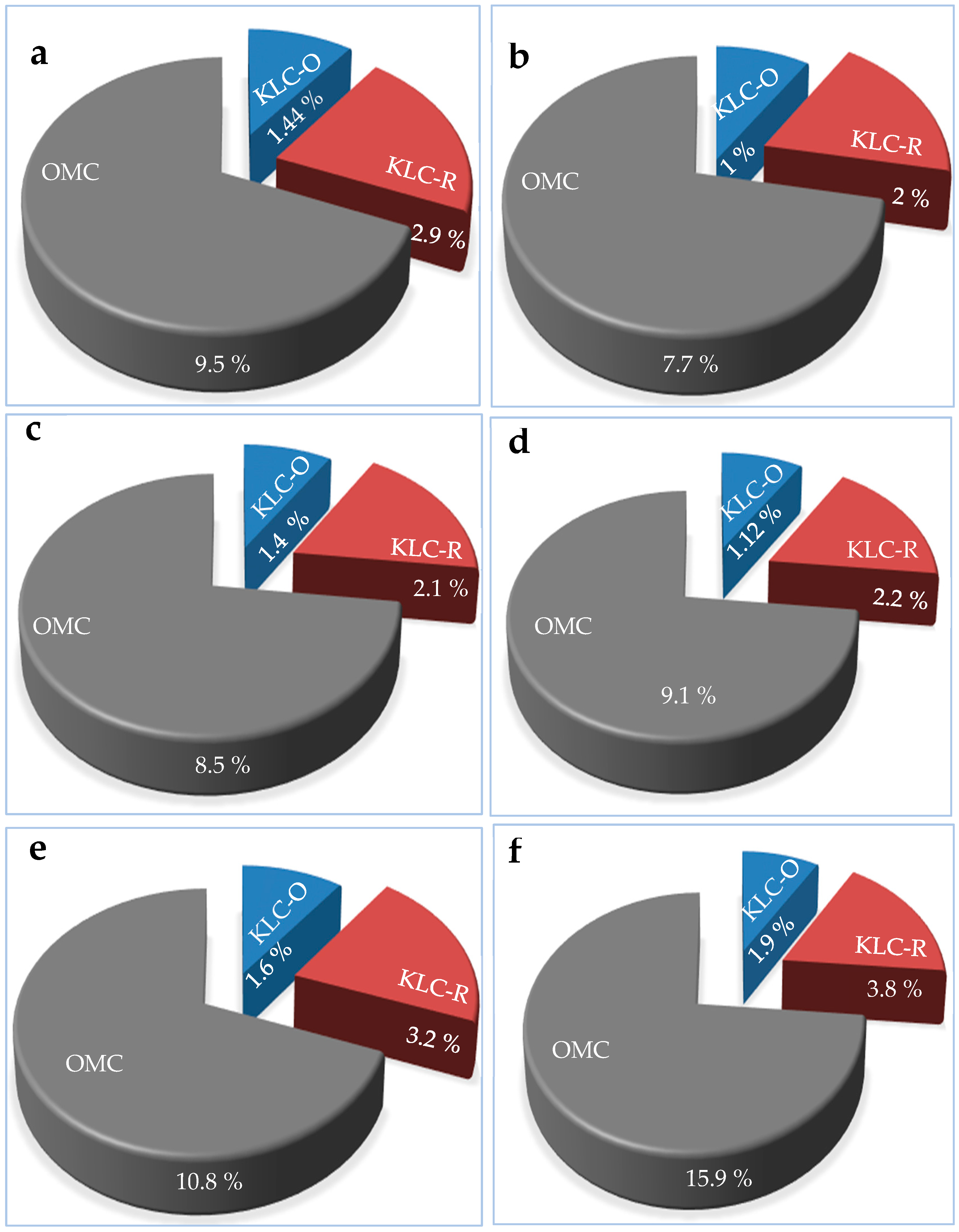

- Klason Lignin Content (KLC) of the Wh

- V.

- Ash Content (AC) of the Wh

- VI.

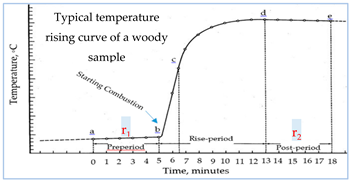

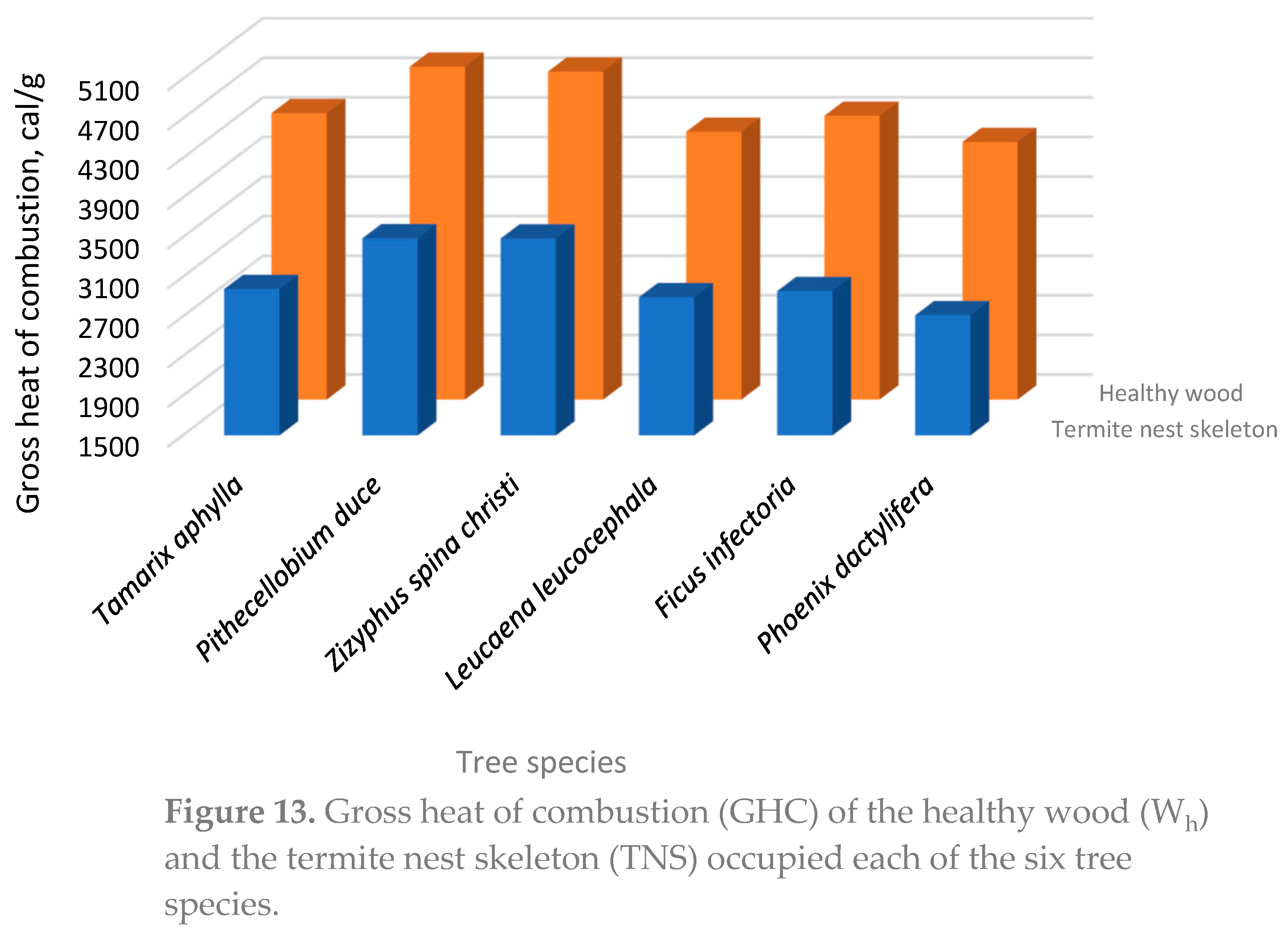

- Gross Heat of Combustion (GHC) of the Wh

2.2.4. Sampling and Characterization of the Termite Nests Skeleton [TNS]

2.2.4.1. Specific Gravity (SG) of the TNS

2.2.4.2. Klason Lignin content (KLC) of the TNS

2.2.4.3. Total Organic Matter Content of the TNS

2.2.4.4. Total Minerals Content of the TNS

2.2.4.5. Gross Heat of Combustion (GHC) of the TNS

2.2.4.6. Mechanical Properties of the TNS

| Equation | Definitions | |

|---|---|---|

|

1 MChw, % = [(Wadhw − Wodhw) / Wodhw] × 100 2 MCtns, % = [(Wadtns − Wodtns) / WodTNS] × 100 3 SGw = Wodhw / Vshw 4 SGtnm = Wodtns / VodTNS 5 AC, % = (Wa / Wefhw) × 100 6 TEC, % = [(W1 - W2 )/W1 ] × 100 7 HC 8 KLC, % = (Wlr / Wefw) × 100 9 TOMS, % = 10 TOMN, % = 11 TMS, % = 12 TMN, % = 13 GHC, calories/g = [(t Ee) - e1 – e2 – e3] / Wodhw or WodTNS 14 t = tc - ta - r1 (b-a) - r2 (c-b) 15 e1 = = c1 if 0.0709N alkali was used for the titration. 16 e2 = (13.7×c2 )(Wodhw or WodTNS) 17 e3 = 2.3× c3 18 r1 = (Ta-Tb) / 5, calories/min. 19 r2 = (Td-Te) / 5}, calories/min.

|

Wadhw: Weight of air-dried healthy wood , g. Wodhw: Weight of oven-dried healthy wood, g. WadTNS: Weight of air-dried termite nest skeleton (TNS), g. WodTNS: Weight of oven-dried termite nest skeleton (TNS), g. Vshw = Volume of water-saturated healthy wood, cm3. VodTNS: Volume of oven-dried TNS, cm3. Wahw: Weight of ash matter of healthy wood. Wefhw = Weight of extractive-free oven-dried healthy wood meal, g. Wlr: Weight of lignin residues, g. WOMS: Weight of total organic matter in soil (open field), g. WOMN: Weight of total organic matter in TNS, g. WMS: Weight of minerals in soil (open field), g. WMN: Weight of minerals in nest, g. GHC: Gross heat of combustion, calorie/g. Ee = Energy equivalent of the calorimeter, determined under standardization e1: Thermochemical correction in calories for heat of formation of nitric acid (HNO3). e2: H2SO4. e3: Thermochemical correction in calories for heat of combustion of fuse wire. a: Time of combusting the sample. b: Time (to nearest 0.1 min.) when the temperature reaches 60 % of the total rise in temperature. c: Time at beginning of the post-period, whereby the rate of temperature change has become constant. c1: milliliters of standard alkali solution used in the acid titration c2: sulfur content in the sample, %. c3: centimeters of fuse wire consumed in firing. Ta: Temperature at time of combusting the sample Tb: Temperature at time of combusting the sample. Tc: Temperature at the point c (See the temperature rise curve, at the left side◦◦). Td: Initial temperature at the final period after combusting the sample. Te: Final temperature at the last period after combusting the sample. r1: rate (temperature units per minute) at which the temperature was rising during the 5-min. period before combusting the sample. r2: rate (temperature units per minute) at which the temperature was rising during the 5-min. period after time, where r1 and/or r2 = ‘+’ when the temperature is rising and ‘-‘when the temperature is falling. |

|

|

20 Cs = Kλ/β1/2Cos θ 21 Ls = nλ / 2sinθ |

K: The correction factor and usually taken to be 0.91 λ: The radiation wavelength of X-rays incident on the crystal (0.1542 nm). θ: The diffraction angle. β1/2: The corrected angular full width at FWHM. FWHM: The full width at half maximum of a XRD- peak. n: An ordinal number taking a value of “1” for diffractograms having the strongest intensity. |

|

|

22 Compression strength = Ff/A 23 MoE = Stress/Strain at the PL = σ/ε 24 ε = [∆L/Lo] = [(Lf − Lo)/Lo] 25 EaF = ∆Lf = [(Lf − Lo)/Lo] × 100 |

Ff : Force at failure in Newton (N). | |

| A: Cross-section area (m2 ) of the Termite nest skeleton. | ||

| σ: Compression stress (Pa). | ||

| Lf : The length of the Termite nest skeleton at failure. | ||

| Lo: The initial length of the Termite nest skeleton at failure. | ||

|

26 d = WodTNS / VodTNS 27 P = 1 – (d/dp) |

dp: Density of non-porous. | |

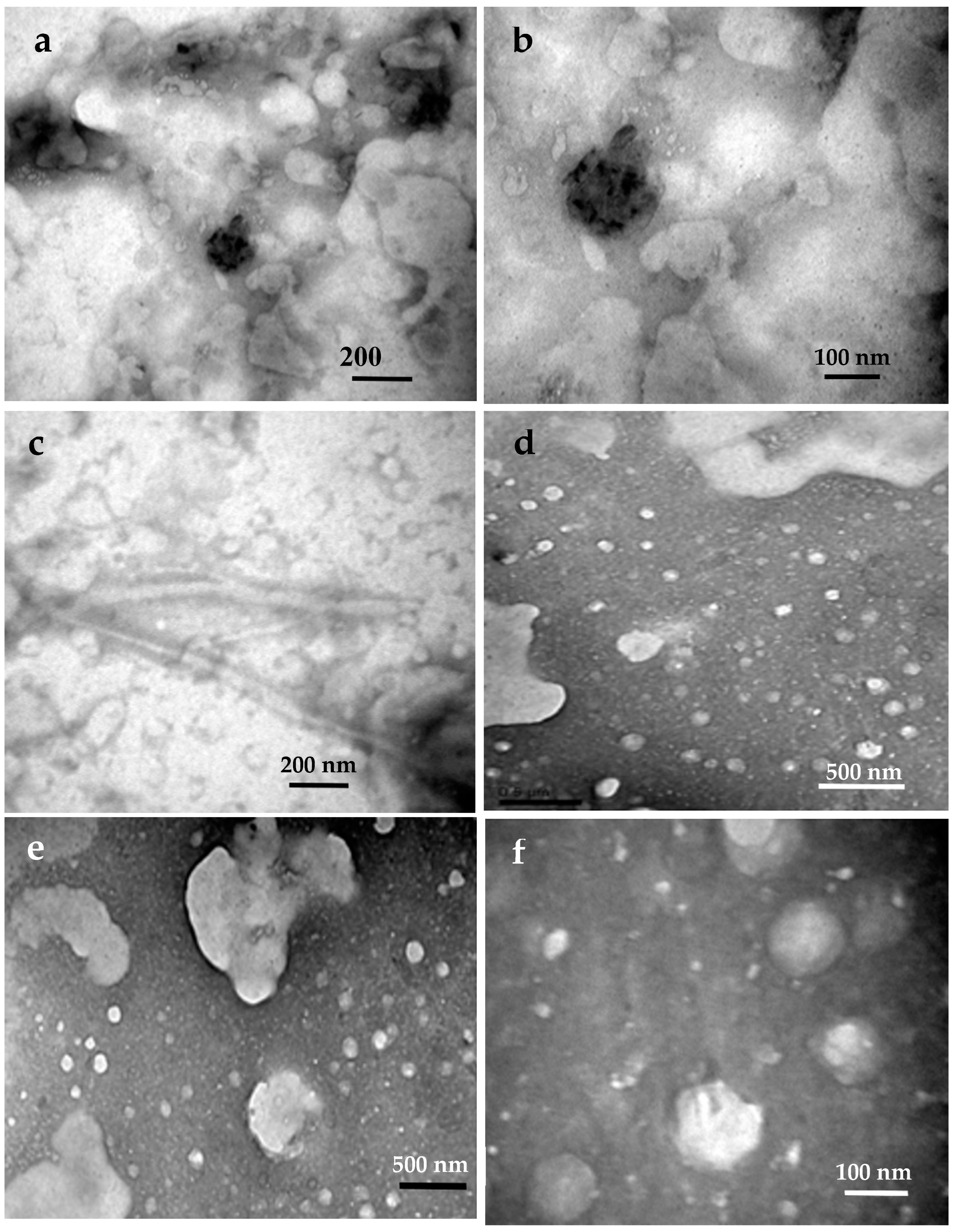

- The Micro- and Nanometric-Scaled Materials

- Characterization

- I.

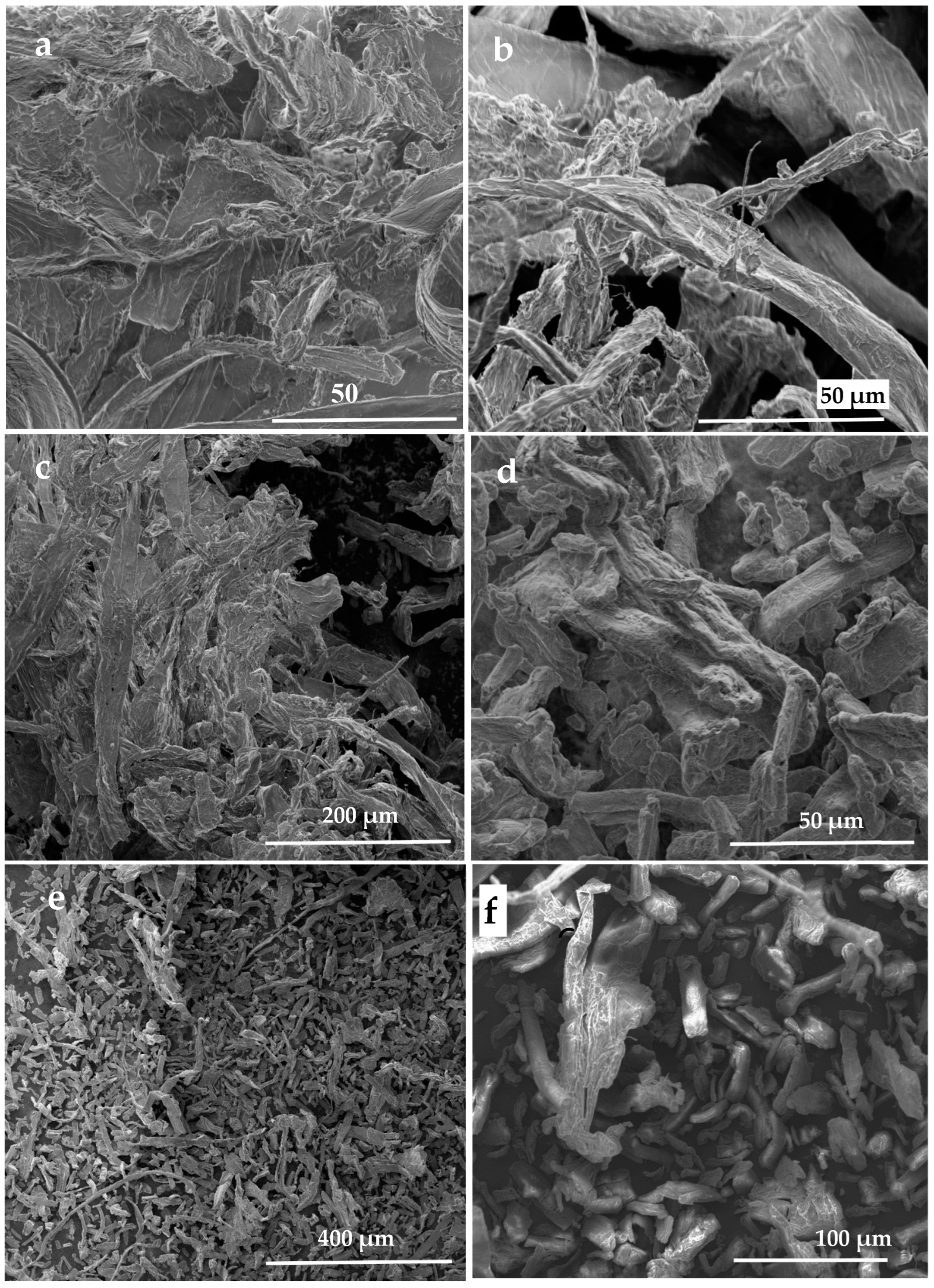

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

- II.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

- III.

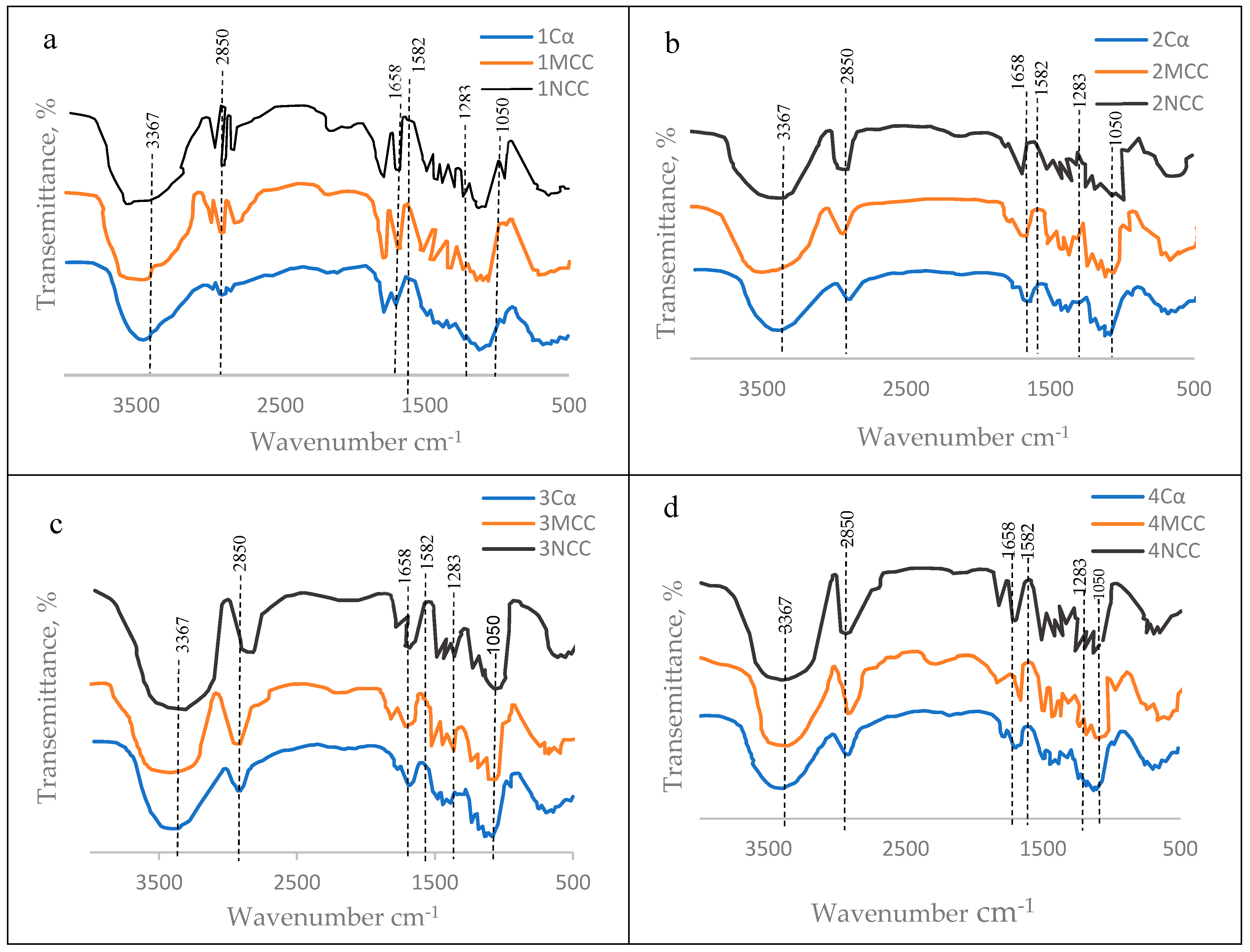

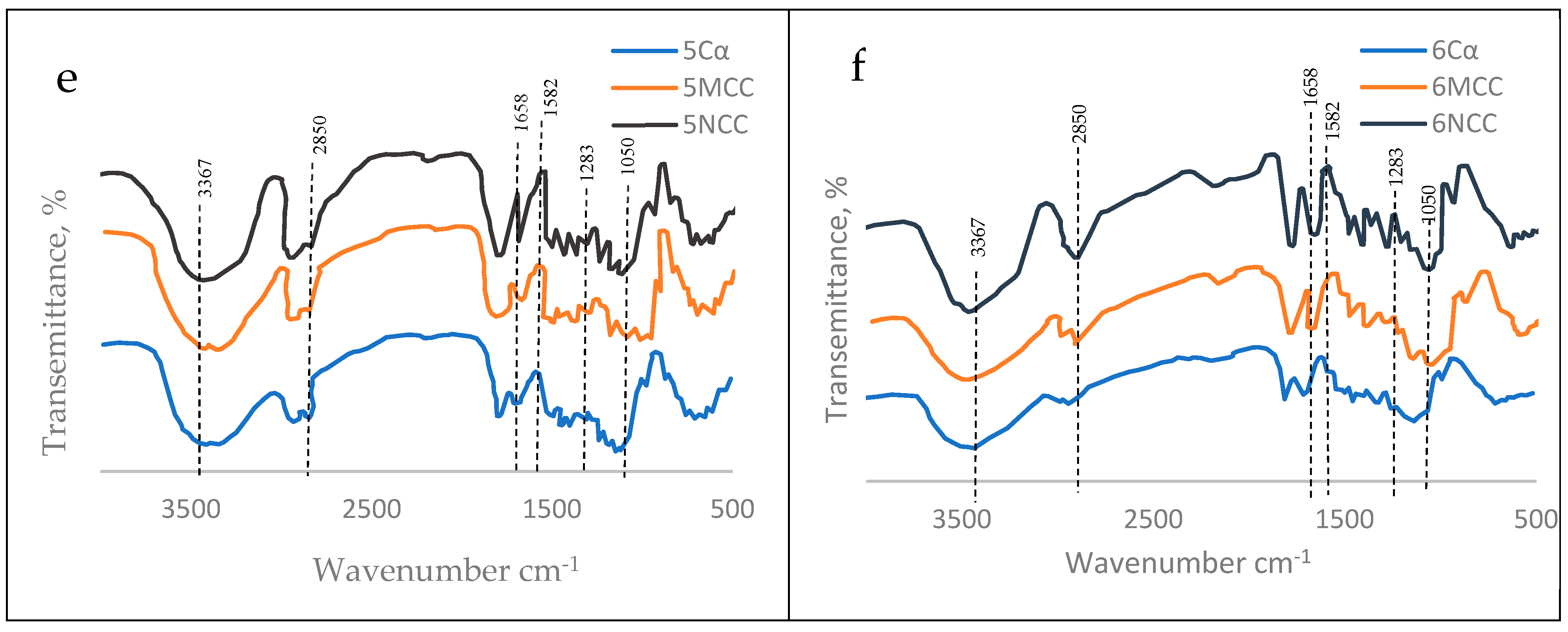

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

- IV.

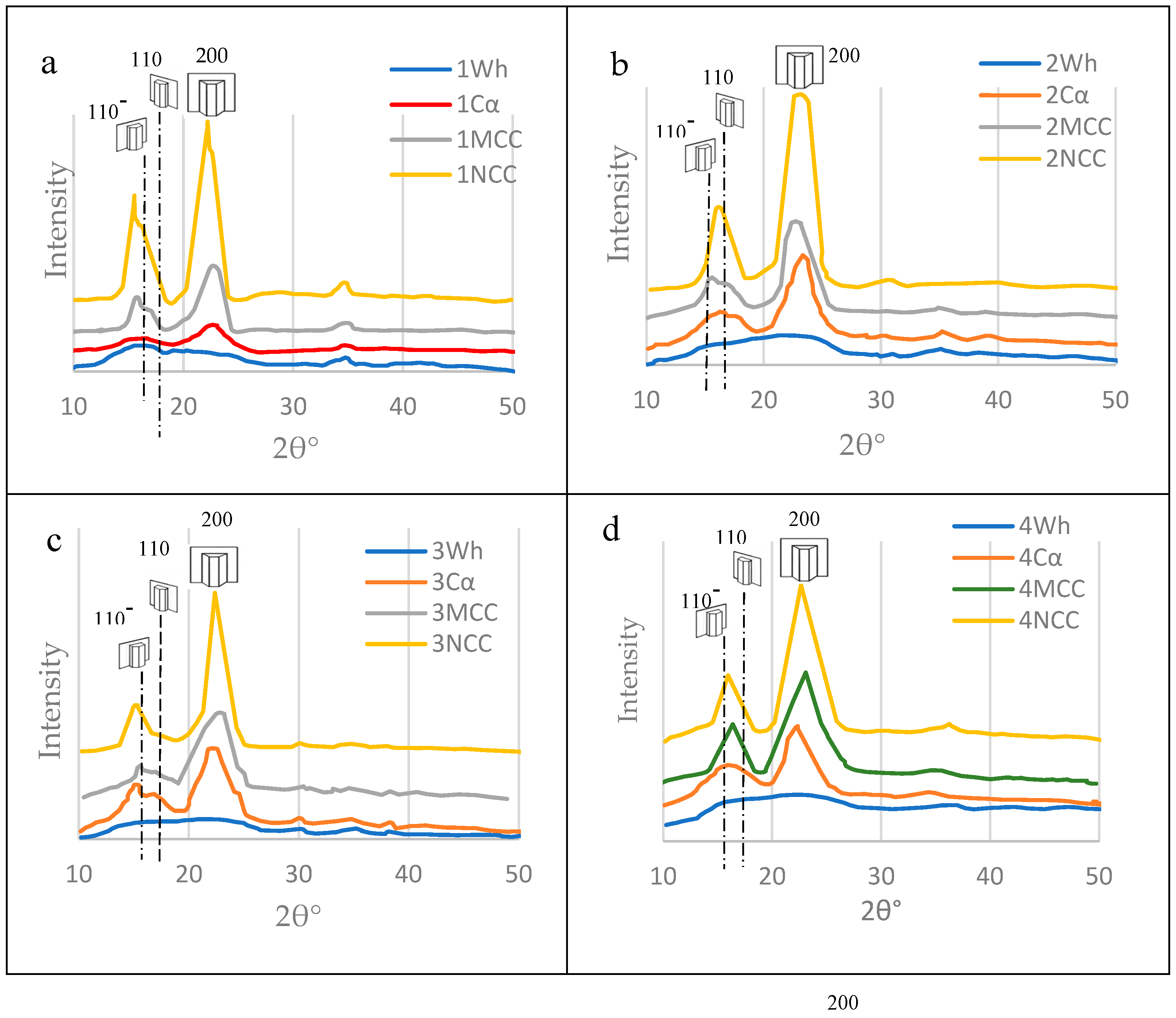

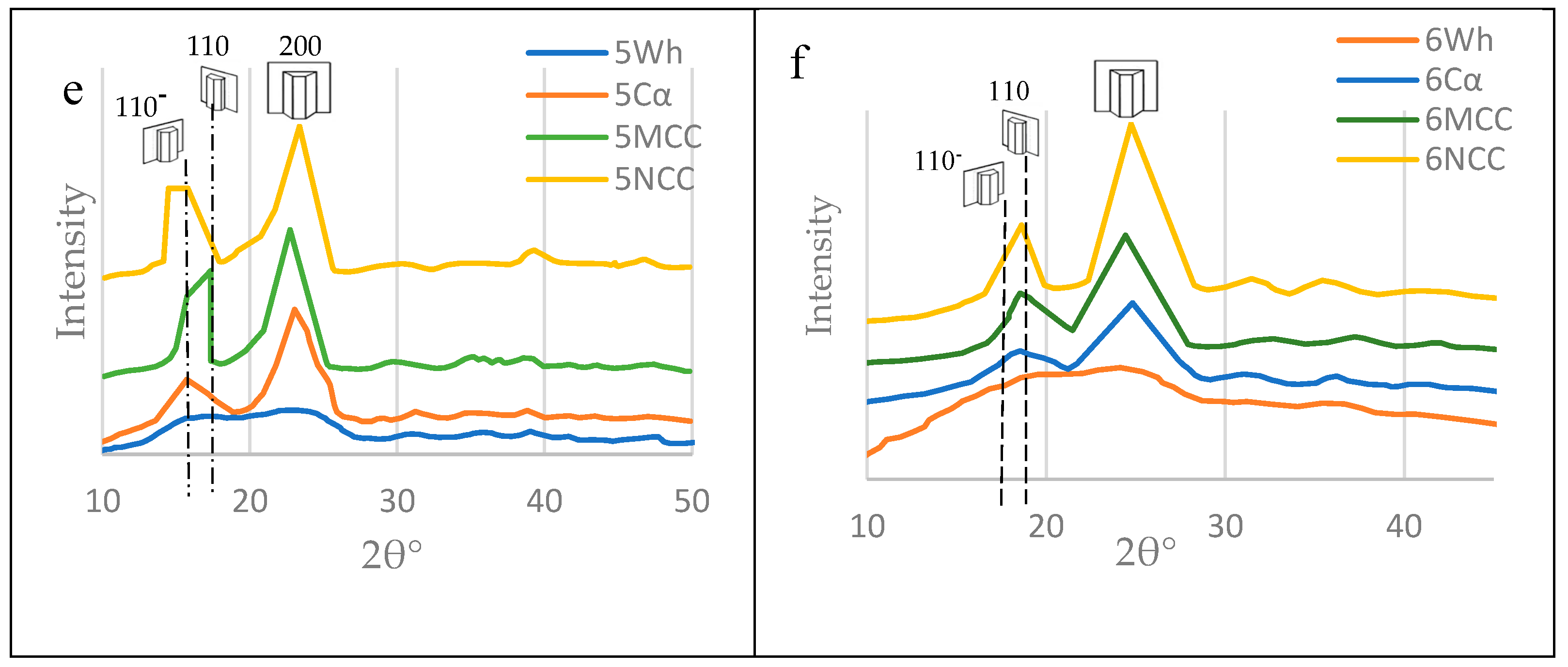

- The X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

- Statistical Design and analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Climate

3.1.1. Climate at Hada Al-Sham

| Property | Height | Mean | Max | Min |

| Air temperature, ◦C at: | 2 m | 24.69 | 33.29 | 14.56 |

| 5 m | 24.75 | 32.7 | 15.85 | |

| 10 m | 22.63 | 63.91 | -0.683 | |

| Soil temperature at 50 cm, °C | 28.79 | 31.37 | 27.93 | |

| Radiation wavelength | Income shortwave | 33.79 | 143.3 | -0.029 |

| Income longwave | 6.26 | 41.76 | -9.39 | |

| Outcome shortwave | 184.53 | 837 | -6.451 | |

| Outcome longwave | -42.579 | -3.387 | -84.1 | |

| Wind speed at 10 m, m/sec | 2.38 | 11.66 | 0 | |

| Wind direction at 10 m, degrees | 159.52 | 353.6 | 0.071 | |

| Barometric pressure, mbar | 988.08 | 993 | 983 | |

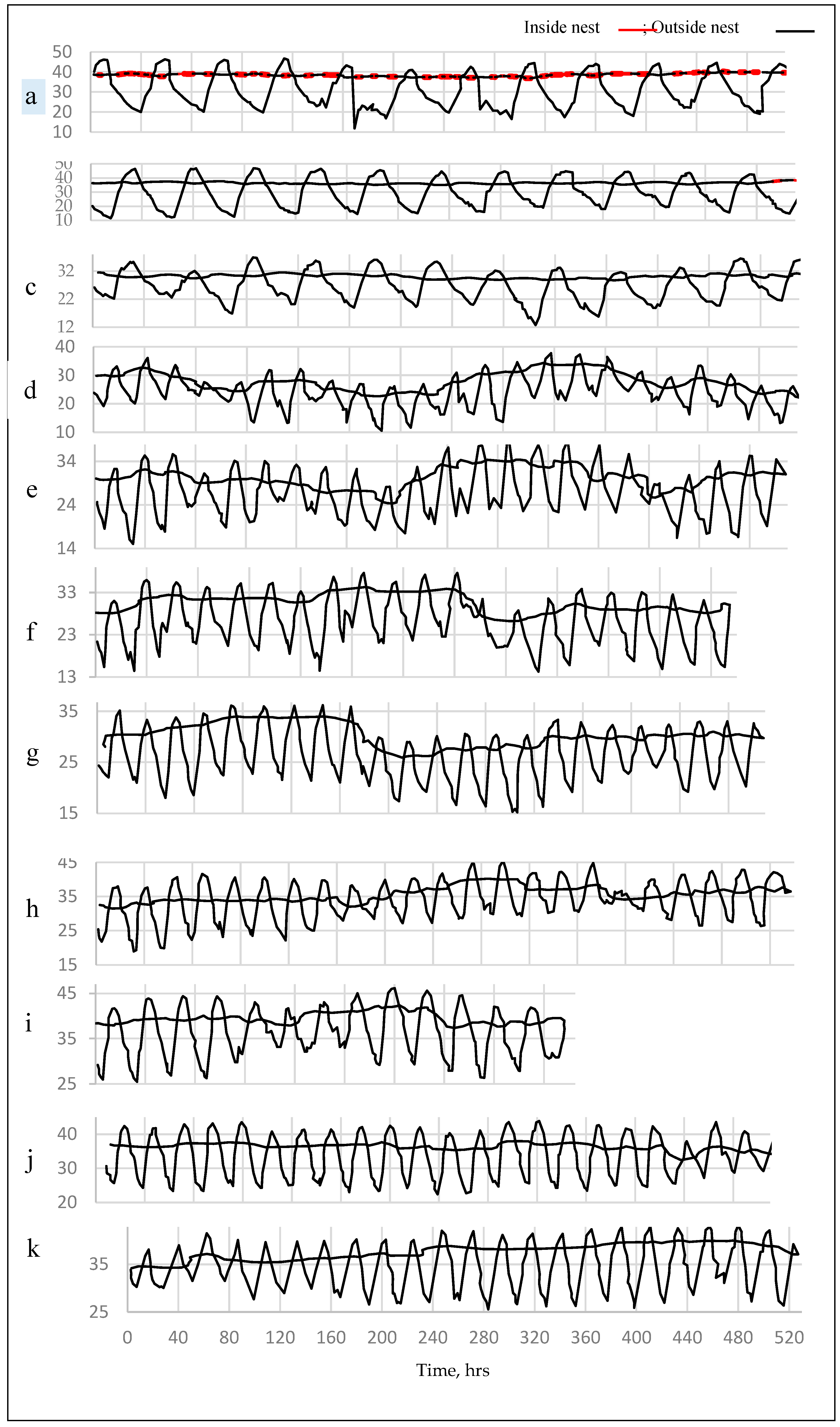

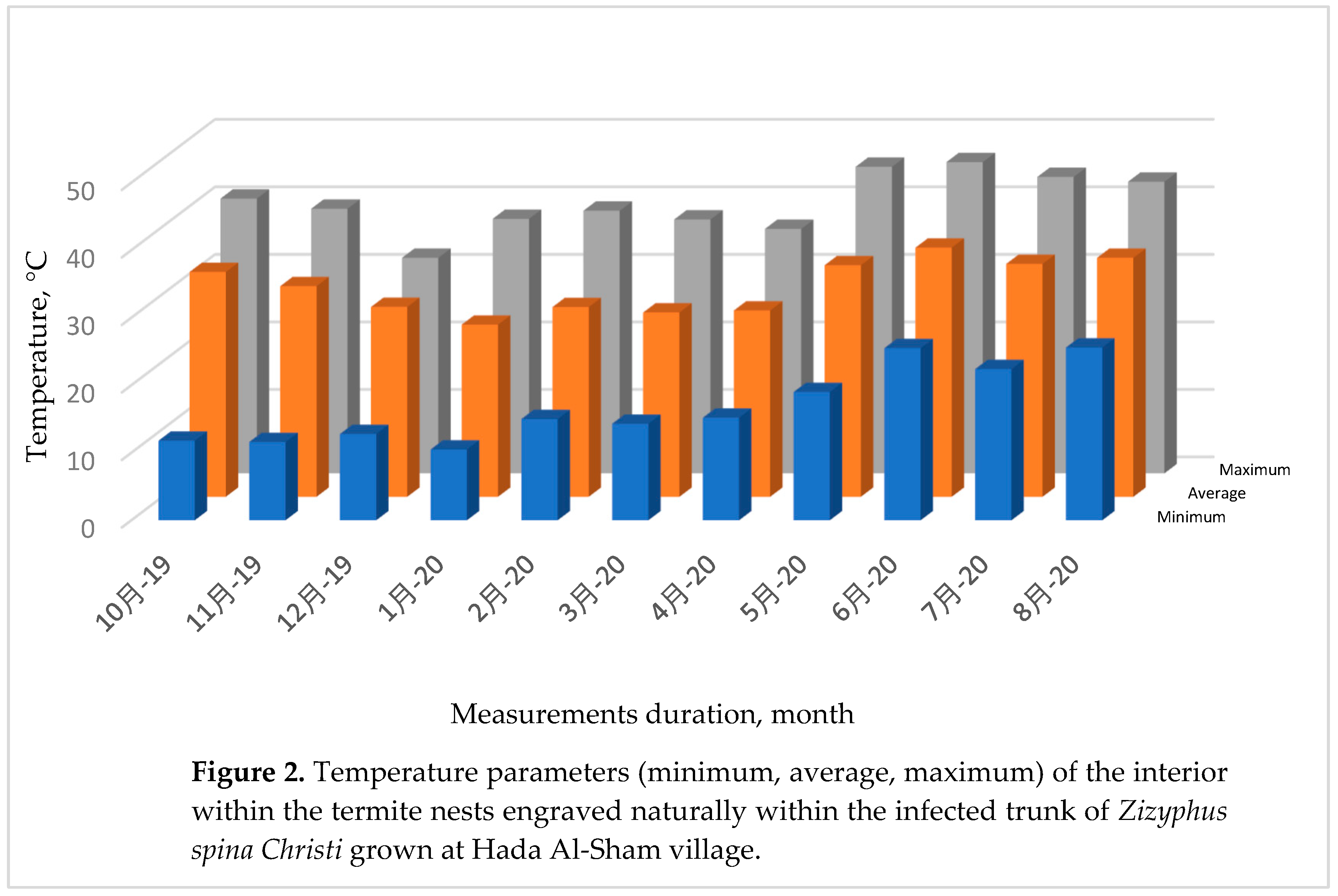

3.1.2. Internal Temperature within the Termite Nests

3.2. Soil

3.2.1. Physical and chemical properties [101,102]

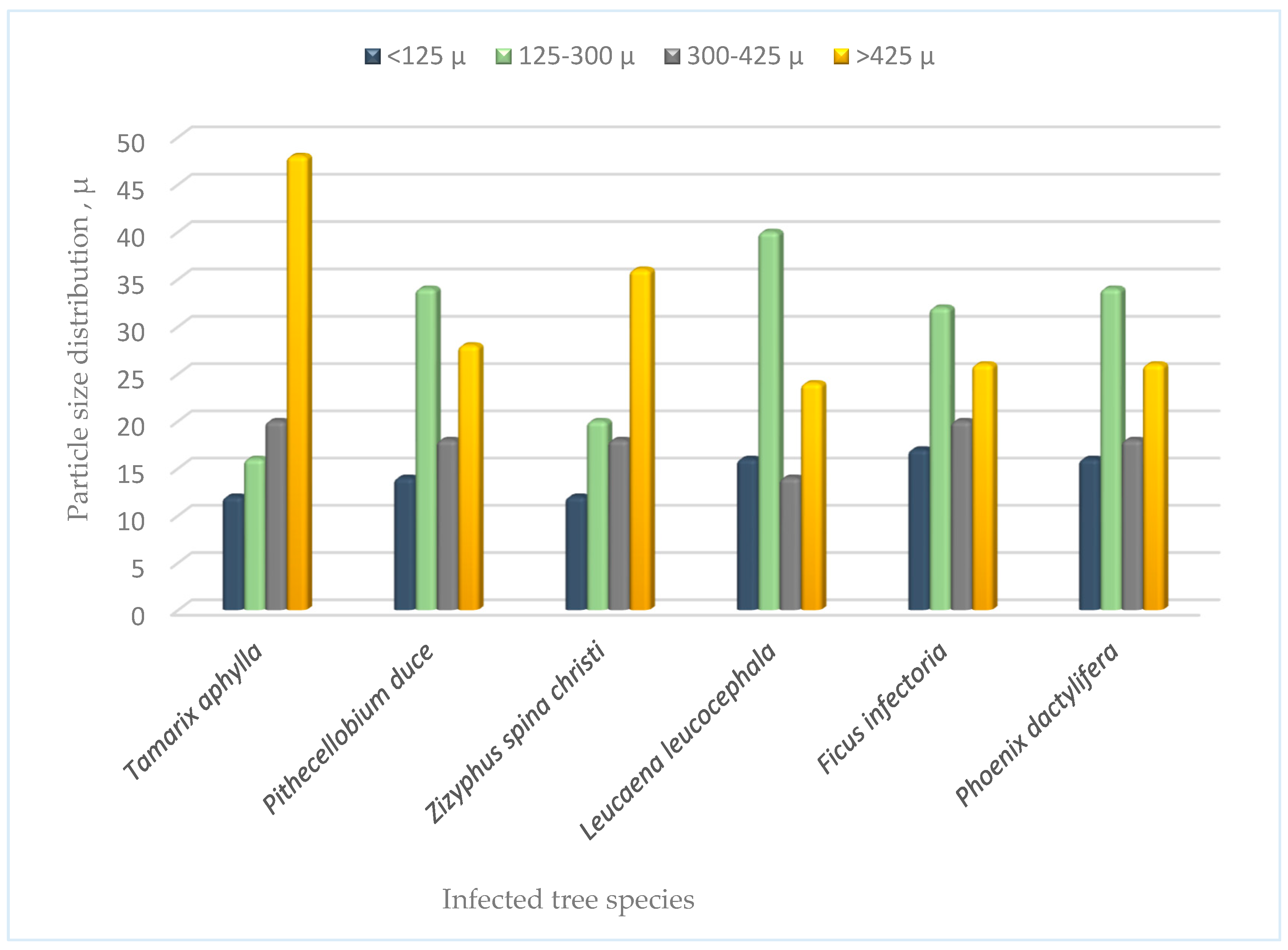

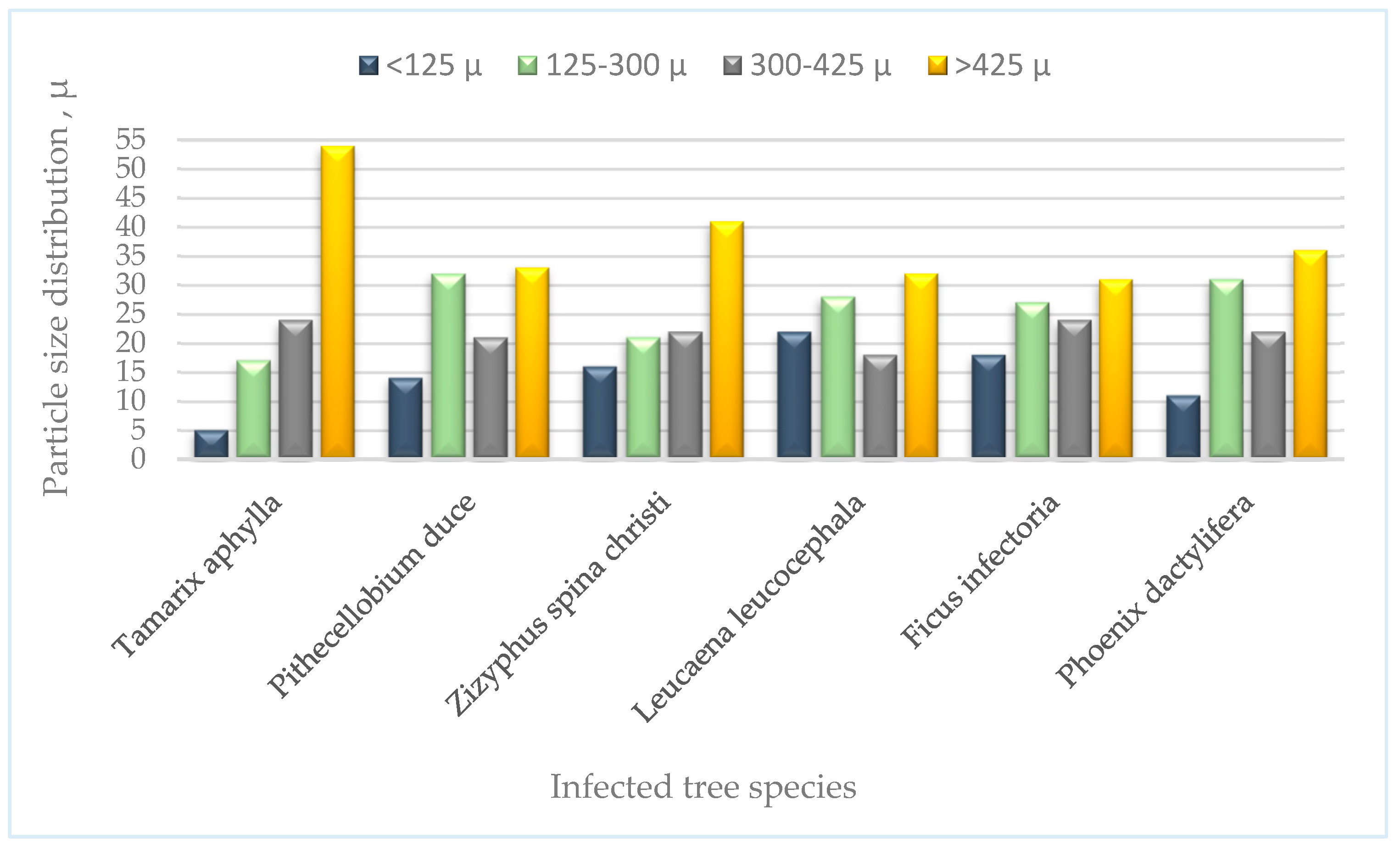

3.2.2. Particle Size Distribution of the Parent Soil

3.2.3. Electrical Conductivity (EC) of Soil

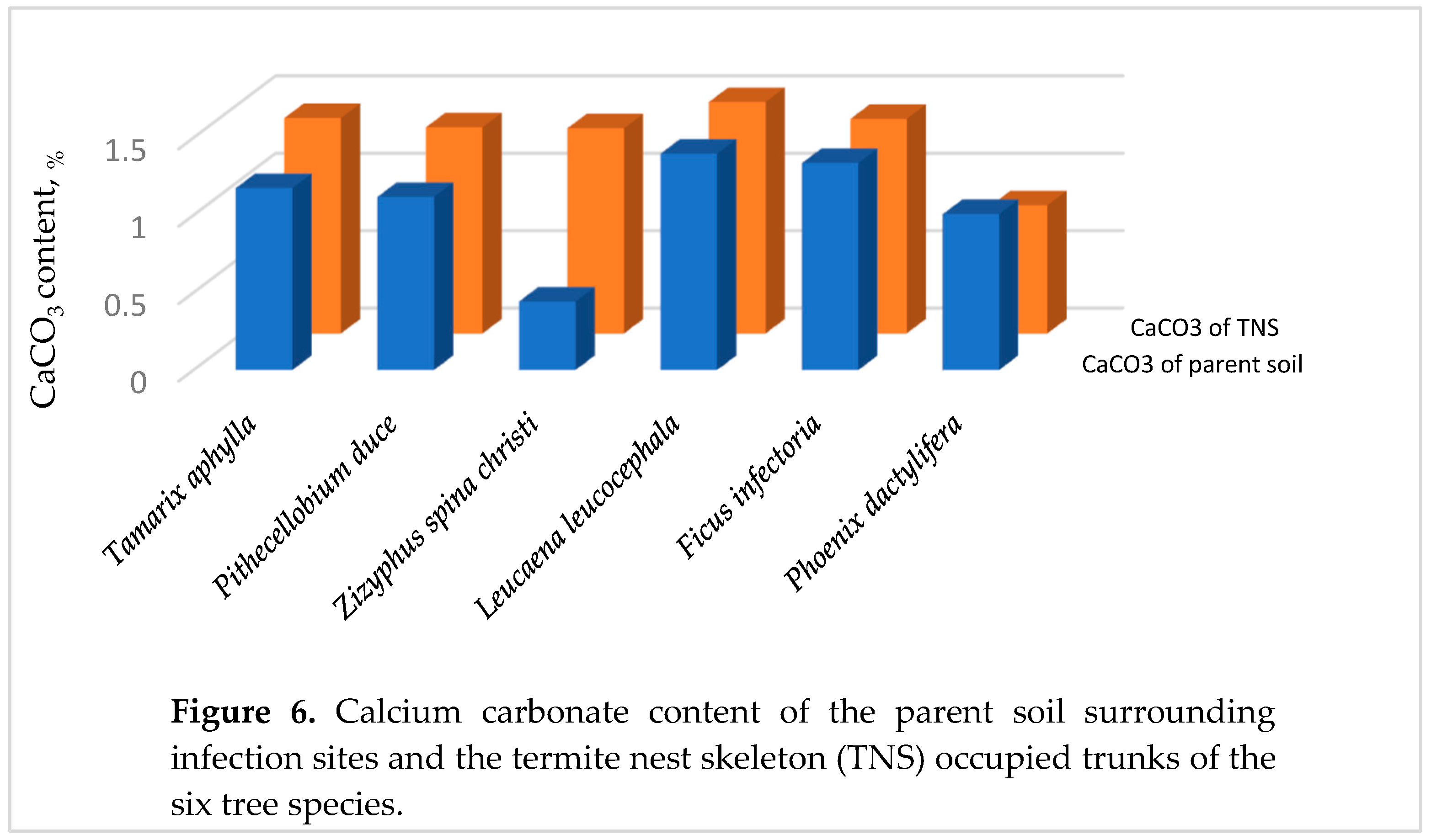

3.2.4. Calcium Carbonate in the Parent Soil

3.3. The Healthy Wood (Wh)

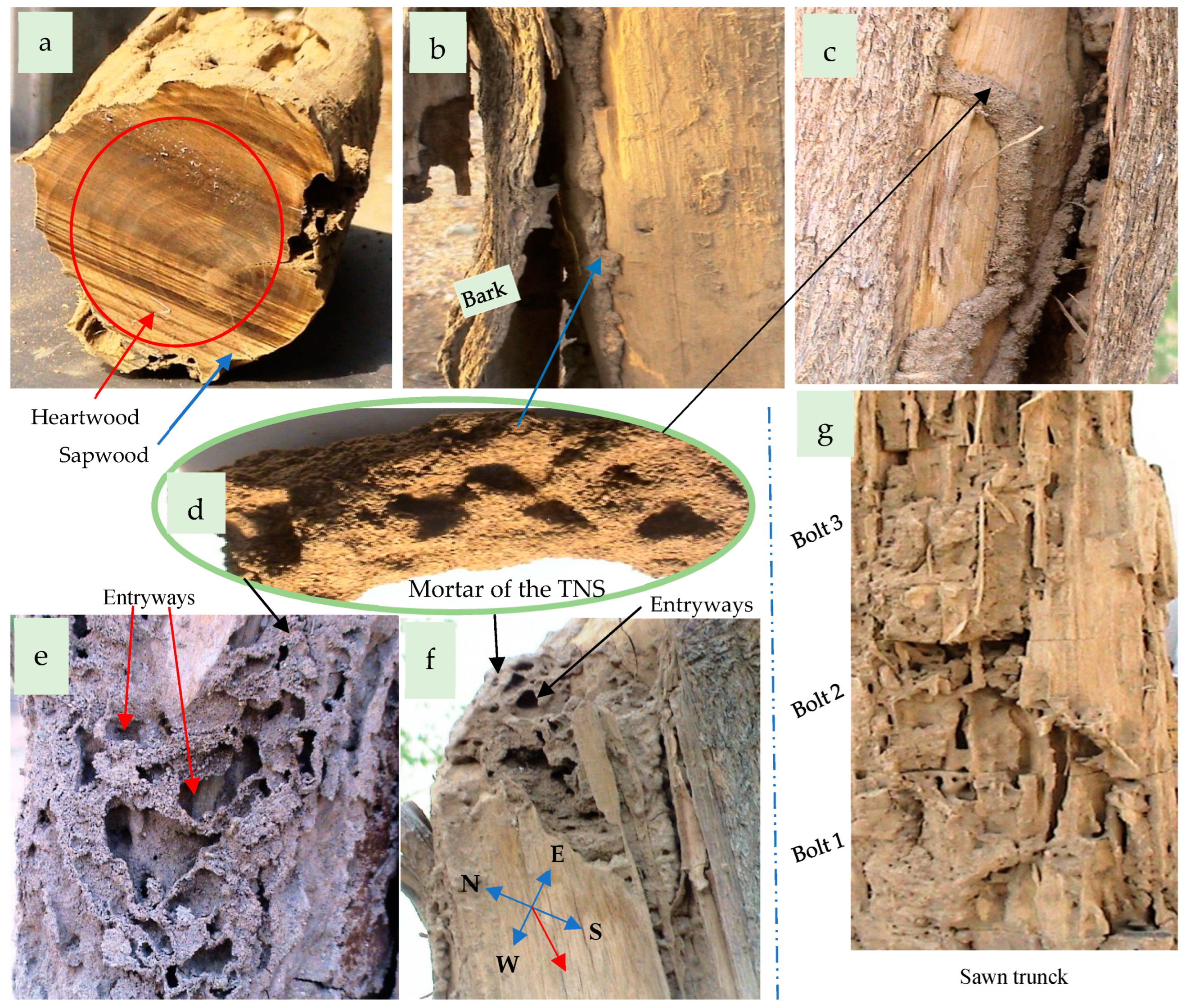

3.4. The Termite Nests

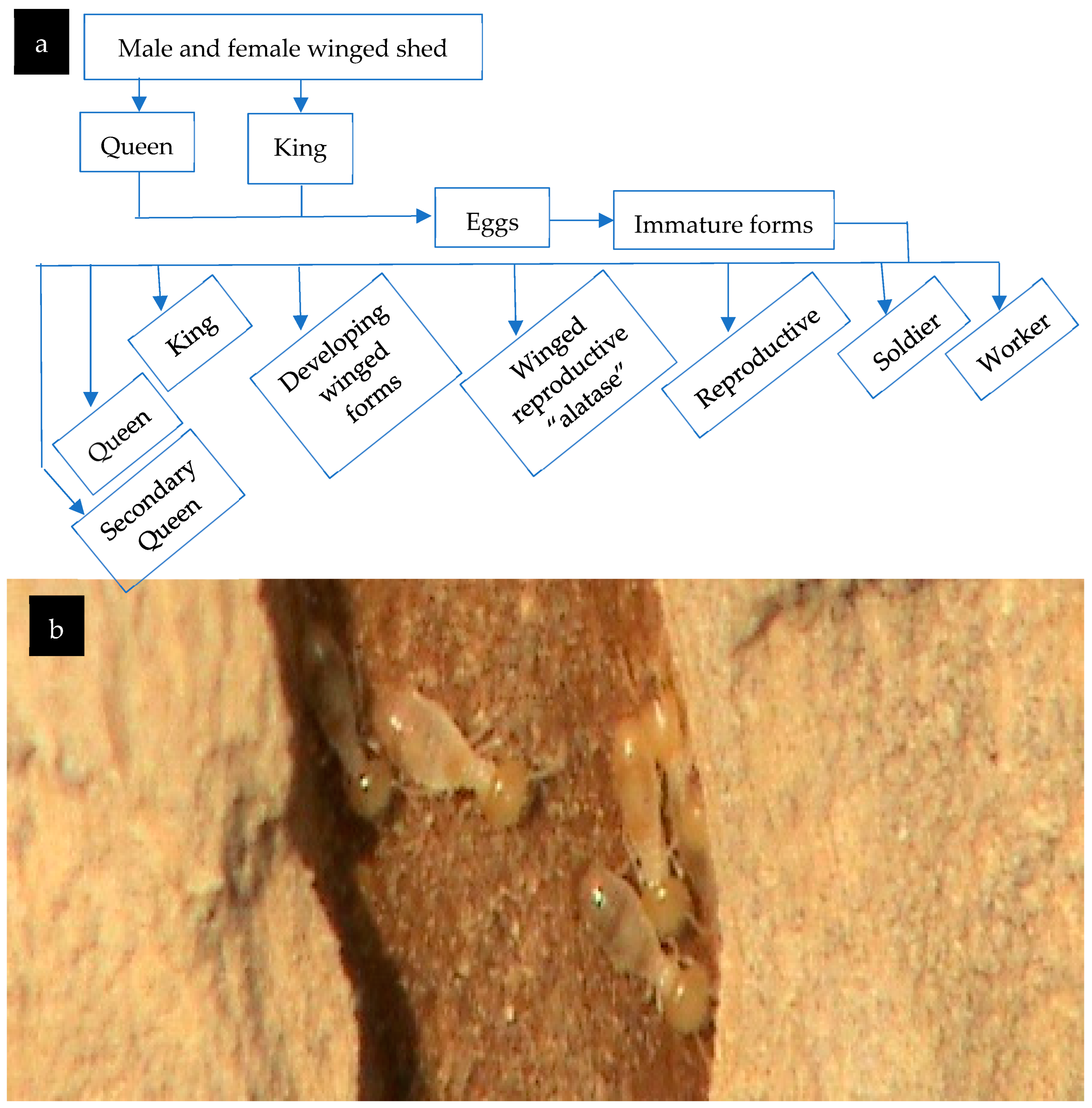

3.4.1. The Termite Colony

3.4.2. The Termite Nest Skeleton (TNS)

3.5. Nanocelluloses Reinforcing the TNS

3.5.1. Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC)

3.5.2. Nanocrystalline Cellulose (NCC)

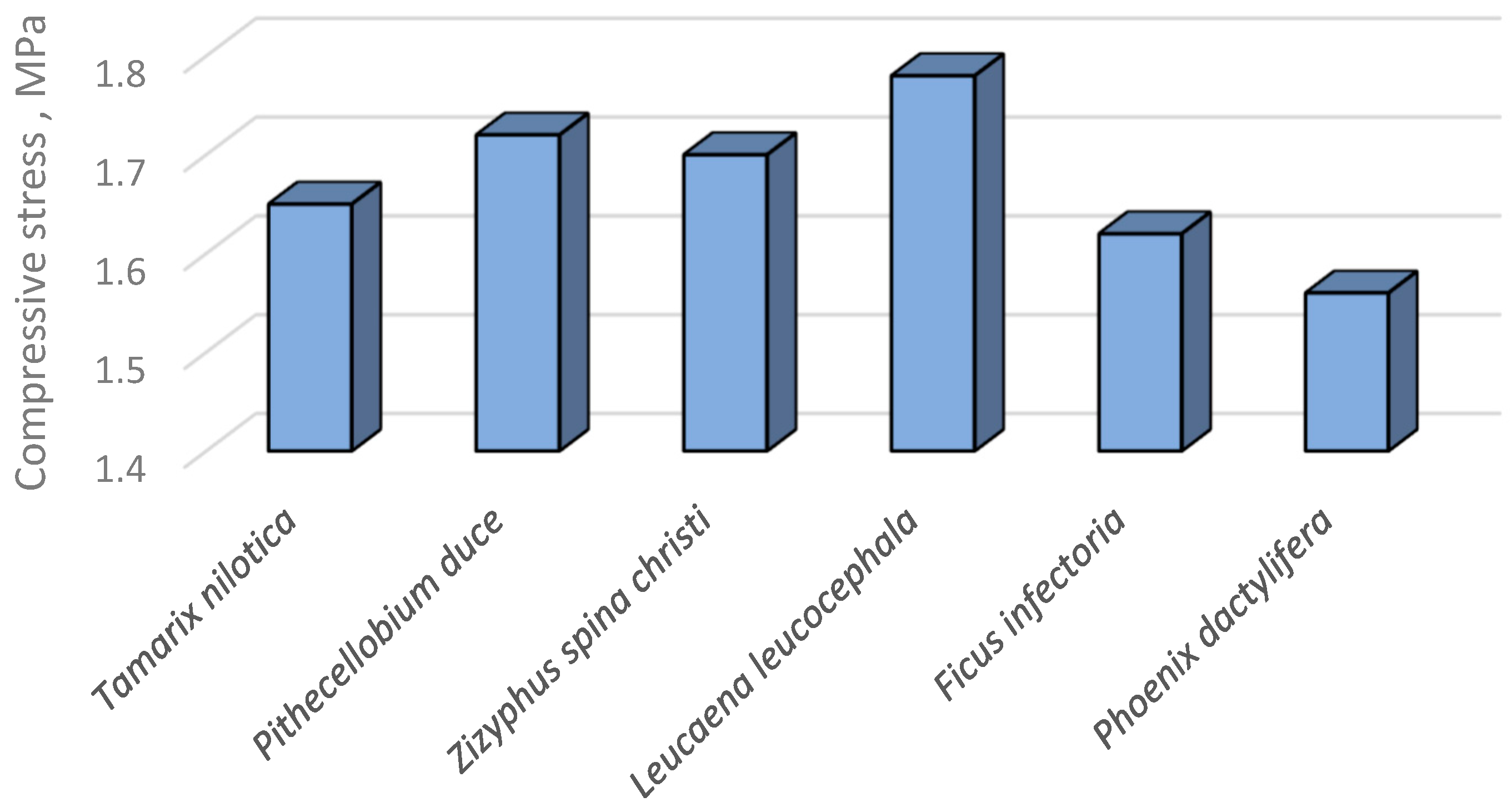

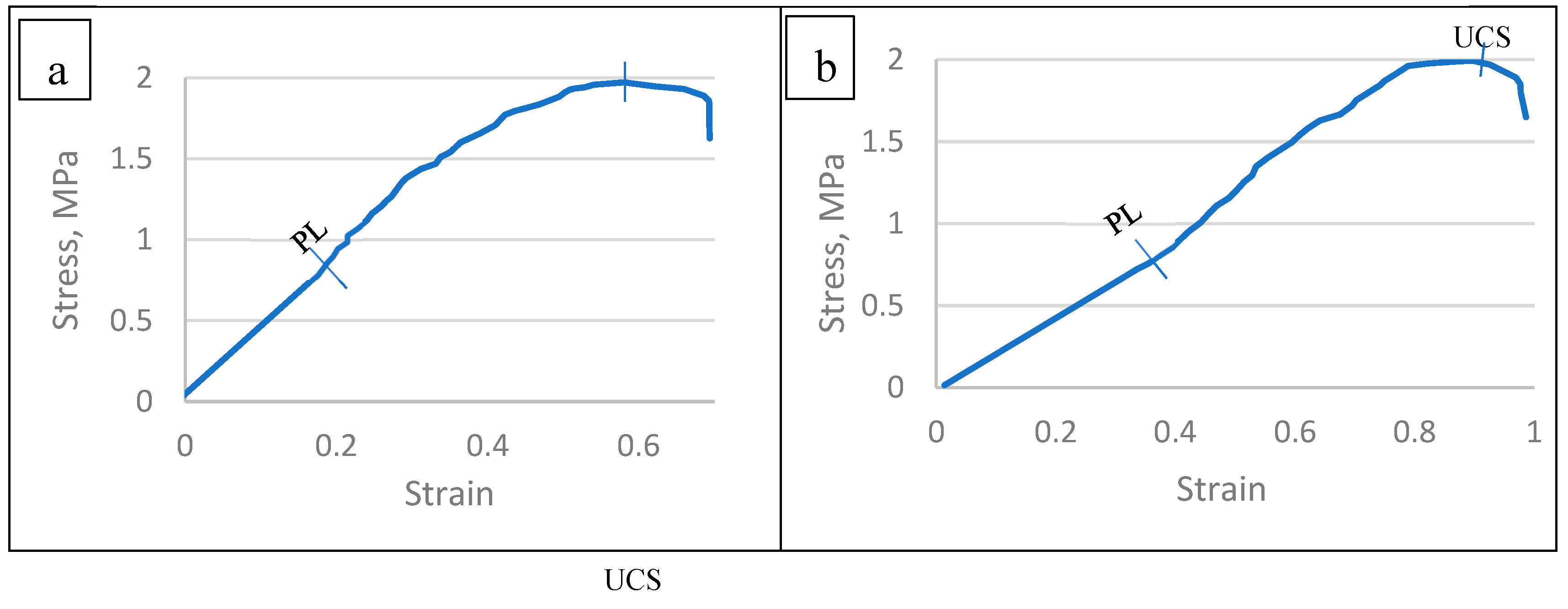

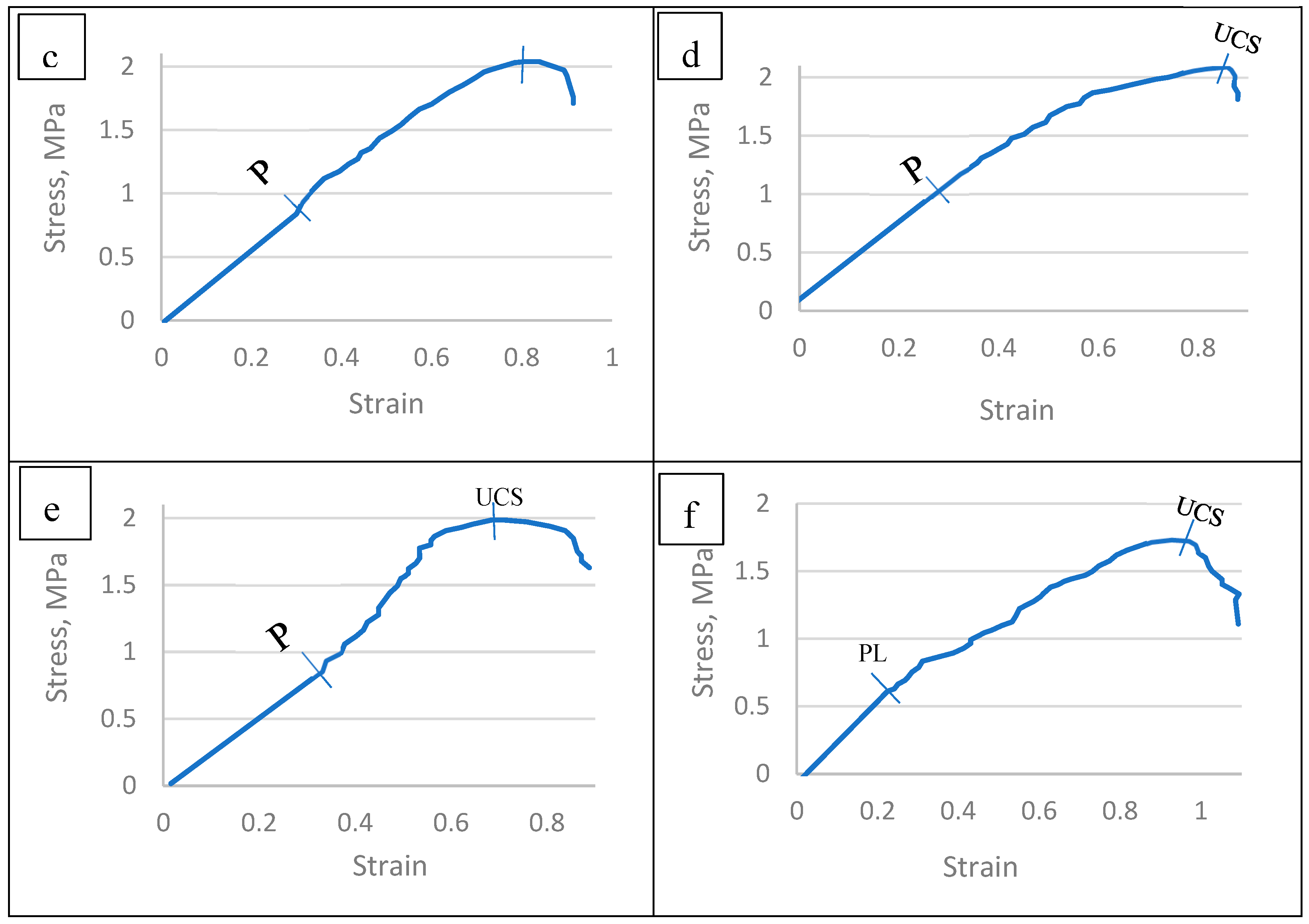

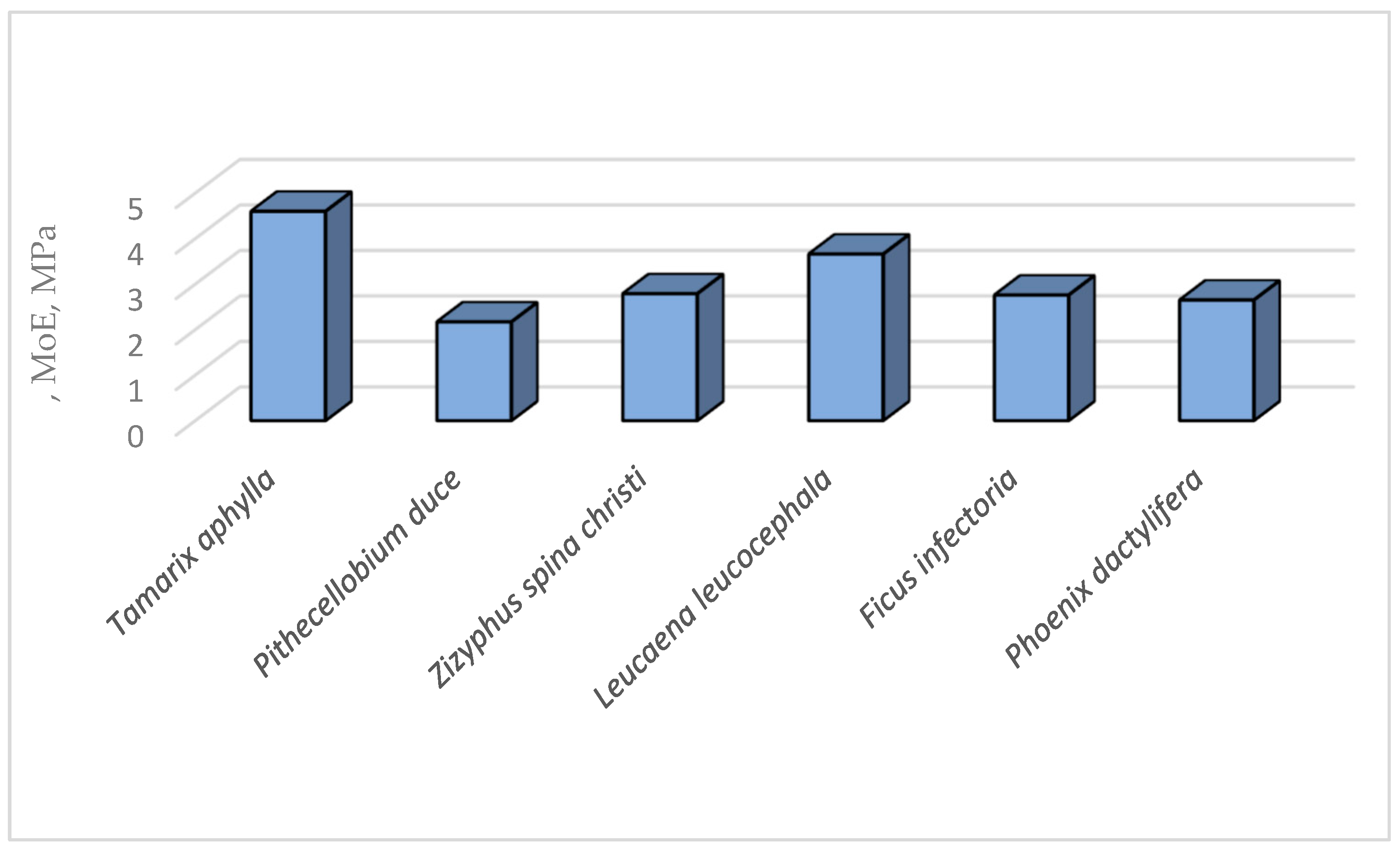

3.6. Mechanical Properties of the TNS as Affected by the Polymeric Blend

3.6.1. Stress–strain relationship of the TNS

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Definition | Symbol | Definition |

| ABE | Alcohol-benzene extractives | OC | Organic carbon |

| AC | Ash content | OMC | Organic matter content |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials | PL | Proportionality Limit |

| FID | Flame-ionization detection | PSD | Particle size distribution |

| GC/MS | Gas Chromatography coupled with mass spectrophotometer | sccm | Standard cubic centimeters per minute |

| HC | Holocelluloses | SEC | Soil Electrical Conductivity |

| KLC | Klason lignin content | SG | Specific gravity |

| LoI | loss on ignition | TEC | Total extractive content |

| MiC | Mineral contents | UCS | Ultimate compressive stress |

| MoE | Modulus of Elasticity | UCD | Ultrafine cellulosic Derivatives |

| MoC | Moisture content |

References

- Gay, F.J. A world review of introduced species of termites. C.S.I.R.0. Melbourne, Bull. No. 1967, 286, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Greening, C. Termite-engineered microbial communities of termite nest structures: a new dimension to the extended phenotype. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 46, fuac034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A.; Al-Kady, H.; Faragalla, A.A. Some factors affecting the distribution and abundance of Termites in Saudi Arabia. Anz. Schadlingskde., Pflanzenschutz, Umweltschutz. 1986, 59, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, M.R.; Husain, M.; Rasool, K.G.; Tufail, M.; Aldawood, A.S. Taxonomy and distribution of termite fauna (Isoptera) in Riyadh Province, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with an updated list of termite species on the Arabian Peninsula. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28, 6795–6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginaldo, C.; Dianese, E.C. The urban termite fauna of Brasilia, Brazil (Isoptera). Sociobiol. 2001, 38, 323–326. [Google Scholar]

- Nutting, W.L.; Jones, S.C. Methods for studying the ecology of subterranean termites. Sociobiol. 1990, 17, 167–189. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghamdi, K.M. , Aseri, A.A. and Mayhoub, J.A. Field study on tunnel shapes of the small Najdian Termite, Microtermes najdensis (Isoptera: Macrotermetidae) and the percentage of infestation in its host plants in Makkah Al., Mokaramah Province. MSc thesis, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. 2009.

- Faragalla, A.A.; Mohamed, H.; Al Qhtani, M.H. The Urban termite fauna (Isoptera) of Jeddah City, Western Saudi Arabia. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10, 1695–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.A.; Wood, T.G. Termites of the arid zones of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Sociobiol 1980, 5, 279–93. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, H.; Al-Hadiy, F.; Halawani, M.; Al-Ghamdi, M. The use of soil pesticides in the control of termites in certain vegetable crops, Annual Technical Report, Agricultural Research Center, Western Region, Saudi Arabia. 1980, 46–47.

- Su, N.Y.; Scheffrahn, R.H. A review of subterranean termite control practices and prospects for integrated pest management programmes. Integr. Pest Manag. Rev. 1998, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, P.G.; Short, D.E.; Kern, W.H. Pests in and around the Florida home. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, IFAS No SP 134. Gainesville FL. 1998.

- Jost, C. Nest-structure: termites. 2021. In: Encyclopedia of social insects, Starr, C.K. ed. Cham, Switzerland, Springer. 2020, 651-660.

- Turner, J.S.; Soar, R.C. Beyond biomimicry: What termites can tell us about realizing the living building? Proceedings of 1st International Conference on Industrialized, Intelligent Construction. 01 January 2008.

- Hindi, S.S.; Abohassan, R.A. Cellulosic microfibril and its embedding matrix within plant cell wall. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2016, 5, 2727–2734. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, J.F.; Himmel, M.E.; Brady, J.W. Simulations of the structure of cellulose. Computational modeling in lignocellulosic biofuel production: ACS Symposium Series 2010, 1052, 17–53. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, C.T. Cellulose microfibrils in plants: biosynthesis, deposition, and integration into the cell wall. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2000, 199, 161–199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Somerville, C. Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006, 22, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, D.; Heublein, B.; Fink, H.P.; Bohn, A. Cellulose: fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2005, 44, 3358–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, R. A, Morrell, J.J. Wood microbiology: Decay and its prevention. Academic Press, New York. 1992.

- Varma, A.; Kolli, B.K.; Paul, J.; Saxena, S.; König, H. Lignocellulose degradation by microorganisms from termite hills and termite guts: A survey on the present state of art. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 15, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppert, C.; Klingeman, W.E.; Willis, J.D.; Oppert, B.; Jurat-fuentes, J.L. Prospecting for cellulolytic activity in insect digestive fluids. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B, Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 155, 145–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, H.V.; Ulvskov, P. Hemicelluloses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegstra, K.; Talmadge, K.W. , Bauer, W.D., Albersheim, P. The structure of plant cell walls: III. A model of the walls of suspension-cultured sycamore cells based on the interconnections of the macromolecular components. Plant Physiol. 1973, 51, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K. EL. Concluding remarks: Where do we stand and where are we going?: Lignin biodegradation and practical utilization. J. Biotechnol. 1993, 30, 149–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.G. and Sands, W.A. The role of termites in ecosystems. In: Brain, M.V., Ed., Production ecology of ants and termites. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 1978, 245–292.

- Faragalla, A.A. Termite problems in Saudi Arabian ecosystems. Sociobiology. 1983, 8, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Faragalla, A.A. Impact of agro desert on a desert ecosystem. J. Arid Environ 1988, 15, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyshen, M. D. Wood decomposition as influenced by invertebrates. Biol. Rev. 2014, 91, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.M. Consumption of wood by artificially isolated colonies of fungus-growing termite Mastotermes bellicosus. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1981, 29, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlington, J.P.E.C. Termite nests in a mound field at Oleserewa, Kenya (Isoptera: Macrotermitinae). Sociobiol. 2000, 35, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, K. Order Isóptera: Termites. In: Borror, D.J; Triplehorn C.A.; Johnson, N.F (Eds). An introduction to the study of insects (6th Edition). Saunders College Publishing, Philadelphia, PA. 1989, 234–241.

- Grace, K.J. Response of eastern and Formosan subterranean termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) to borate dust and soil treatments. J. Econ. Entomol. 1991, 84, 1753–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleton, P.; Bignell, D.E. Monitoring the response of tropical insects to changes in the environment: Troubles with termites. In: Harrington, R. and Stork. (Eds). Insects in a changing environment. London. Heademic Press. 1995, 473–497.

- Faragalla, A.A.; AL-Ghamdi, K.M.S. Monitoring field populations of the harvester termite Anacanthotermes ochraceous (Burmeister) in two locations in western Saudi Arabia. Sociobiol. 1999, 34, 419–427. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, M.; Anderson, J.P.; Whitford, W.G. Spatial and temporal variability in foraging intensities of subterranean termites in decertified and relatively intact Chihuahua desert ecosystem. App. Soil Ecol. 1999, 12, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.Y; La Fage, J.P. Forager populations and caste composition of colonies of the Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) restricted to cypress trees in the clacasteus river, Lake Charies, Louisiana. Sociobiol. 1999, 33, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford, W.G. Effects of habitat characteristics on the abundance and activity of subterranean termites in arid Southeastern New Mexico (Isoptera). Sociobiol. 1999, 34, 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, A. Termite foraging interaction with a protective barrier system. A. PhD. Thesis, Sustainable Mineral Institute, the University of Queensland, Australia. 2009, 156.

- Miller, D.M. , 2010. Subterranean termite’s biology and behavior. Virginia Cooperative Extension.

- Suiter, D.R.; Jones, S.C.; Forschler, B.T. Biology of subterranean termites in the Eastern United States. Bulletin 1209. The Ohio State University. 2010.

- Duryea, M.L. Landscape Mulches. Will subterranean termites consume them? University of Florida IFAS Extension Publication. 2011.

- Arshad, M.A. Physical and chemical properties of termite mounds of two species of Microcerotermes (Isoptera: Termitidae) and the surrounding soils of the semi-arid Savanna of Kenya. Soil Sci. 1981, 132, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, K.M.; Faragalla, A.A. Field Study on gallery shapes of the harvester termite Anacanthotermes ochraceous (Burmeistser) (Isoptera: Hodotermitidae) from different localities in Western Saudi Arabia. Annals of Agric. Sci. Moshtohor. 1998, 36, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Chouvenc, T.; Su, N.-Y. When subterranean termite challenge the rules for fungal epizootic. PLoSOne. 2012, 7, e 34484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, S. E.; Jones, D.T.; Sands, W.A.; Eggleton, P. Morphological phylogenetics of termites (Isoptera). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2000, 70, 467–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptáček, P.; Brandštetr, J.; Šoukal, F.; Opravil, T. Investigation of subterranean termites nest material composition, structure and properties. Intech, Chapter 2013, 20, 519–549. [Google Scholar]

- Mattéotti, C.; Bauwens, J.; Brasseur, C.; et al. Identification and characterization of a new xylanase from Gram-positive bacteria isolated from termite gut [Reticulitermes santonensis]. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012, 83, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaytor, M. Cellulose digestion in termites and cockroaches: What role do symbionts play? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B, Comp. Biochem. 1992, 103, 775–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, R.D. Termites and the turnover of dead wood in an arid tropical environment. Oecologia. 1981, 51, 379–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassé, P.; Noirot, P.C. Le meule des termites champignonnistes et sa signification symbiotique. Ann. sci. nat., Zool. biol. anim. 1958, 11, 113–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hyodo, F.; Inoue, T.; Azuma, J.; Tayasu, I.; Abe, I.T. Role of the mutualistic fungus in lignin degradation in the fungus-growing termite Macrotermes gilvus (Isoptera: Macrotermitinae). Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 653–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.L.; Crawford, R.L. Microbial degradation of lignocellulose: the lignin component. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1976, 31, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, D.L.; Crawford, R.L.; Pometto A., L. Preparation of specifically labeled 14C-(lignin) – and 14C– (cellulose) –lignocelluloses and their decomposition by the microflora of soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 33, 1247–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, D.L. Lignocellulose decomposition by selected Streptomyces strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1978, 35, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.L. Microbial conversions of lignin to useful chemicals using a lignin–degrading Streptomyces. Biotechnol. Bioeng. Symp. 1981, 11, 275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, D.L. , Barder, M.J.; Pometto, A.L.; R. Crawford, R.L. Chemistry of softwood lignin degradation by a Streptomyces. Arch. Microbiol. 1982, 131, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, D.L.; Pometto, A.L.; Crawford, R.L. Lignin degradation by Streptomyces viridosporus: isolation and characterization of a new polymeric lignin degradation intermediate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 45, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.L.; Pettey, T.M.; Thede, B.M.; Deobald, L.A. Genetic manipulation of ligninolytic Streptomyces and generation of improved lignin to chemical bioconversion strains. Biotechnol. Bioeng. Symp. 1984, 14, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, D.L. The role of actinomycetes in the decomposition of lignocellulose. FEMS Symp. 1986, 34, 715–728. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, T.K.; Farrell, R.L. Enzymatic combustion: the microbial degradation of lignin. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 1987, 41, 465–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, R.T. The Practical Handbook of Compost Engineering; Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL. 1993.

- Badawi, A.I.; Faragalla, A.A.; Dabbour. A.I. The role of termites in changing certain chemical characteristics of the soil. Sociobiol. 1982, 7, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sabine, G. Soil modification by the harvester termite Hodotermes mossambicus (Isoptera: Hodotermitidae) in a semi-arid savanna glass land of Namibia. Sociobiol. 2001, 37, 757–767. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomela, M, Vikman, M, Hatakka, A, & Itävaara, M. Biodegradation of lignin in a compost environment: a review. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 72, 169–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasse, D.P.; Dignac, M.-F.; Bahri, H.; Rumpel, C.; Mariotti, A.; Chenu, C. . Lignin turnover in an agricultural field: From plant residues to soil-protected fractions. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2006, 57, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rückamp, D.; Martius, C.; Bragança, M.A.L.; Amelung, W. Lignin patterns in soil and termite nests of the Brazilian Cerrado. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2011, 48, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, S.S. Differentiation and synonyms standardization of amorphous and crystalline cellulosic products. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Res. 2017, 4, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Microcrystalline cellulose: The inexhaustible treasure for pharmaceutical industry. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Res. 2017, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Suitability of date palm leaflets for sulphated cellulose nanocrystals synthesis. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Res. 2017, 4, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, S.S. Nanocrystalline cellulose: Synthesis from pruning waste of Zizyphus spina christi and characterization. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Res. 2017, 4, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S.; Abouhassan, R.A. Method for making nanoocrystalline cellulose. U.S. Patent No. 10,144,786B2, 4 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. A Method for converting micro- to nanocrystalline cellulose. U.S. Patent No. 10808045, 20 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Nanocrystalline cellulose. U.S. Patent No. 11,161,918, 2 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Urchin-shaped nanocrystalline material. U.S. Patent No. 11242410, 8 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Sulfate-grafted nanocrystalline cellulose. U.S. Patent No. 11242411, 8 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Evaluation of guaiacol and syringol emission upon wood pyrolysis for some fast growing species. Paper presented at the ICEBESE: International Conference on Environmental, Biological, and Ecological Sciences, and Engineering to be held during August: 24–26, 2011, Paris, France.

- Hindi, S.S.; Abdel-Rahman, G.M.; AL–Qubaie, A.I. Gross heat of combustion for some Saudi hardwoods. Int. j. sci. eng. investig. 2012, 1, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Effect of maximum final temperature on properties of wood based biocarbon of Tamarix Aphylla. Int. j. sci. eng. investig 2012, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Contribution of parent wood to the final properties of the carbonaceous skeleton via pyrolysis. Int. j. sci. eng. investig. 2012, 1, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Fluids production from wood wastes via pyrolysis. Int. j. sci. eng. investig. 2012, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. Effect of wood material and pyrolytic conditions on biocarbon production. Int. J. Modern Eng. Res. 2012, 2, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.L. Soil chemical analysis. Prentice-Hall, Inc. Englewood Cliffs, N. J. New Delhi, India. 1973.

- ASTM D 2974 – Standard test methods for moisture, ash, and organic matter of peat and organic soils.

- Hoogsteen, M.J.J.; Lantinga, E.A.; Bakker, E.J.; Groot, J.C.J.; Tittonell, P.A. Estimating soil organic carbon through loss on ignition: effects of ignition conditions and structural water loss. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2015, 66, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FernandesIldeu, R.B.A.; Emerson, A.C.J.; Junior, S.R.; Mendonça, E.S. Comparison of different methods for the determination of total organic carbon and humic substances in Brazilian soils. Nutrição de Plantas Rev. Ceres. 2015, 62, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM. D 2395-84. 1989. Standard test method for ash in wood. Philadelphia, Pa. USA.

- ASTM. D 1105-84. 1989. Standard method for preparation of extractive-free wood. Philadelphia, Pa. USA.

- Trilokesh, C.; Uppuluri, K.B. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from jackfruit peel. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 16709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, L.E.; Merphy, M.M.D.; Adieco, M. Chlorite holocellulose, its fractionation and bearing on summative wood analysis and on studies on the hemicelluloses. Pap. Trade J. 1946, 122, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM. D 1106–84. 1989. Standard test method for acid-insoluble lignin in wood. Philadelphia, Pa. USA.

- Jayme, G.; Knolle, H.; Rapp, G. Development and final version of lignin determination method according to Jayme-Knolle. Das Papier. 1958, 12, 464–467. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM. D 2015–85.1987. Standard test method for gross calorific value of coal and coke by the adiabatic bomb calorimeter. Philadelphia, Pa. USA.

- Neenan, M.; Steinbeck. Calorific values for young sprouts in hardwood species. Forest sci. 1979, 25, 455–461. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah, N.; Singh, S.; Murthy, T.; Borges, R. Bi-layered architecture facilitates high strength and ventilation in nest mounds of fungus-farming termites. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 13157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, V.; Caus, F.; Ambrosio, L. Porosity and mechanical properties relationship in PCL porous scaffolds. J. Appl. Biomater. Biomech. 2007 5, 149–157.

- Hindi, S.S. Some crystallographic properties of cellulose I as affected by cellulosic resource, smoothing, and computation methods. Int. J. Innov. Res. Technol. Sci. Eng. 2017, 6, 732–752. [Google Scholar]

- El-Nakhlawy, F.S. Experimental design and analysis in scientific research; Sci. Pub. Center, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2009.

- Korb, J. , Linsenmair, K. Thermoregulation of termite mounds: what role does ambient temperature and metabolism of the colony play? Insectes soc. 2000, 47, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, H.; Ocko, S.; Mahadevan, L. Termite mounds harness diurnal temperature oscillations for ventilation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2015, 112, 11589–11593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiry, K.A; Nurul Huda, M.d.; Mousa, M. & Abundance and population dynamics of the key insect pests and agronomic traits of tomato (Solanum lycopersicon L.) varieties under different planting densities as a sustainable pest control method. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 976. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y.; Jamil, M.; AlOtaibi, T.S.; Abdelaziz, M.E.; Ota, T.; Ibrahim, O.H.; Berqdar, L.; Asami, T.; Mousa, M.A.A.; Al-Babili, S. Zaxinone mimics (MiZax) efficiently promote growth and production of potato and strawberry Plants under Desert Climate Conditions. 2023. 11f4c693-ac07-4c51-854d-82c41111d7c3.pdf (kaust.edu.sa) (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Hindi, S.S.; Bakhashwain, A.A.; El-Feel, A.A. Physico-chemical characterization of some Saudi lignocellulosic natural resources and their suitability for fiber production. JKAU; Met. Env. Arid Land Agric. Sci. 2011, 21, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hindi, S.S. 2017. Some Promising Hardwoods for Cellulose Production: I. Chemical and Anatomical Features. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Res. 2017, 4, 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, F.; Garcia, M.M.; Yanez, R.; Tapias, R.; Fernandez, M.; Diaz, M.J. Leucaena species valoration for biomass and paper production in 1 and 2 year harvest. Biores. Technol. 2008, 99, 4846–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.J.; Garcia, M.M.; Eugenio, M.M.; Tapias, R.; Fernandez, M.; Lopez, F. Variations in fiber length and some pulp chemical properties of leucaena varieties. Indust. Crops Prod. 2007, 26, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khristova, P.; Kordsachia, O.; Khider, T. Alkaline pulping with additives of date palm rachis and leaves from Sudan. Biores. Technol. 2005, 96, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindi, S.S. Method for recovery of cellulosic material from waste lingocellulosic material. US Patent, 11136715; issue date: 10 May 2021,

- Hindi, S.S. A method for isolating alpha cellulose from lignocellulosic materials. U.S. patent, 11078624; issue date: 03 August 2021,

- Hindi, S.S. Method for separating lignin from lignocellulosic material. US Patent, 11, 306, 434B2; issue date: 18 April 2022,

- Creffield, J.W. Wood-destroying Insects–Wood borers and termites. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria. 1996, 44 pp.

- Creffield, J.W. Call for the immediate declaration of all municipalities [metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria] as regions where homes, buildings and structures are subject to termite infestation. 2005, 1–21.

- Shaikh, H.M.; Anis, A.; Poulose, A.M.; Al-Zahrani, S.M.; Madhar, N.A.; Alhamidi, A.; Alam, M.A. Isolation and characterization of alpha and nanocrystalline cellulose from date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) trunk mesh. Polym. 2021, 13, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Song, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Kong, F.; Bu, F.; Kanungo, D.; Sun, S. Improvement effect of water-based organic polymer on the strength properties of fiber glass reinforced sand. Polym. 2018, 10, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Valuem % |

| Clay % | 9.7 |

| Silt % | 15.5 |

| Sand % | 74.8 |

| Texture class | Sandy loam |

| Bulk density (g/cm3) | 1.87 |

| Air porosity (%) | 29.4 |

| Organic matter (%) | 0.65% |

| EC [1:1 soil extraction] (dS m-1) | 0.366 |

| pH (1:1 soil suspension) | 7.70 |

| Species | SG g/cm3 |

AC4 % |

TEC4 % |

HC4 % |

KLC4 % |

GHC calories/g |

| Tamarix aphylla | 0.71 ± 0.04 |

5.43 ± 0.048 |

15.76 ± 0.35 |

51.8 ± 2.08 |

27.9 ± 0.56 |

4393 ± 91.3 |

| Pithecellobium duce | 0.61 ± 0.02 |

3.8 ± 0.08 |

6.91 ± 0.31 |

69.41 ± 2.34 |

20.3 ± 0.45 |

4763 ± 102.7 |

| Zizyphus spina christi | 0.72 ± 0.018 |

1.9 ± 0.02 |

18.89 ± 0.32 |

59.5 ± 2.42 |

19.71 ± 0.61 |

4814 ± 105.4 |

| Leucaena leucocephala | 0.59 ± 0.03 |

1.22 ± 0.02 |

9.74 ± 0. 34 |

70.82 ± 1.73 |

18.86 ± 0.14 |

4206 ± 86.7 |

| Ficus infectoria | 0.54 ± 0.032 |

2.44 ± 0.018 |

10.54 ± 0.26 |

61.59 ± 2.85 |

25.43 ± 1.31 |

4367 ± 78.4 |

| Phoenix dactylifera | 0.42 ± 0.015 |

6.71 ± 0.71 |

18.3 ± 0.42 |

53.57 ± 2.29 |

22.43 ± 1.07 |

4102 ± 82.49 |

| Wavenumber cm−1 | Reason of band appearance |

| 1050 | C–C ring stretching band and C–O–C glycosidic ether band. |

| 1283 | Scissoring motion of the CH2-group. |

| 1583 | O-H bending of the absorbed water. |

| 1658 | C-O stretching vibration for the acetyl and ester linkages. |

| 2850 | C-H stretching. |

| 3367 | O-H stretching (axial vibration) intramolecular hydrogen bonds. |

| Species | StressType | StressMPa | Strain |

| Tamarix aphylla | PL | 0.865 | 0.188 |

| UCS | 1.973 | 0.58 | |

| Pithecellobium duce | PL | 0.814 | 0.375 |

| UCS | 1.992 | 0.878 | |

| Zizyphus spina christi | PL | 0.84 | 0.301 |

| UCS | 2.037 | 0.805 | |

| Leucaena leucocephala | PL | 1.116 | 0.305 |

| UCS | 2.092 | 0.858 | |

| Ficus infectoria | PL | 0.936 | 0.339 |

| UCS | 1.987 | 0.685 | |

| Phoenix dactylifera | PL | 0.664 | 0.251 |

| UCS | 1.733 | 0.927 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).