1. Introduction

Creating functional foods through the enrichment of novel foods with probiotic organisms or spores is a promising approach. Processed foods with improved health benefits compared to traditional nutritional options can now be produced with the advancements in current food processing technology Poshadri

, et al. [

1]. In contemporary society, consumers are growing increasingly health-conscious, giving greater significance to the nutritional value of their food choices. Consequently, the successful acceptance of novel foods depends on the concept of food quality and additional value-added food functionalities, particularly those related to probiotics [

2].

Probiotics can be academically defined as living microorganisms that, when administered in sufficient quantities, impart advantageous health effects upon the host organism"[

3]. Probiotic items must possess at least 10

6 cfu/g of probiotic microorganisms and ensure their viability remains intact throughout their designated shelf life to access these advantages [

4].

Bacillus coagulans (

B. coagulans) are widely employed in food and feed additives for effectively inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria. However, many of these microorganisms become inactive during manufacturing, storage, and the rigorous processing involved in functional foods. Their vulnerability to stomach acid and high temperatures can cause a significant loss of viable probiotic bacteria [

5]. A study by Altun and Erginkaya [

6] revealed that

B. coagulans can thrive within a pH range of 5.5–6.2 and release spores at 37°C, earning it the designation of Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS). Within the small intestine, the spores of this bacterium play a crucial role in carbohydrate digestion in the human gastrointestinal tract. Probiotics play a pivotal role in maintaining gastrointestinal homeostasis and energy balance, and they hold promise in preventing and treating metabolic syndromes such as obesity, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia [

7]. However, ensuring the viability of probiotic-containing products remains a significant challenge. Probiotics must endure industrial processing, storage conditions, and the journey through the gastrointestinal tract. Microencapsulation technology has proven suitable for preserving probiotic cells and spores, significantly enhancing their viability in food products and the gastrointestinal tract [

8].

In addition, probiotics have the capacity to generate metabolites that enhance the host's health, encompassing enzymes, vitamins, peptides, essential amino acids, and antioxidants [

9,

10]. These metabolites play valuable roles in bolstering human well-being. In addition, probiotics offer a range of notable benefits, such as preventing hypertension [

11] and diabetes [

12], reducing cholesterol levels [

13], exhibiting anti-carcinogenic activity [

14], improving anxiety and depression conditions [

15], modulating the immune system [

16], preventing food allergy and atopic diseases [

17], etc. Microencapsulation is a technique that offers physical protection to bacteria spore and bioactive elements, preventing chemical degradation and ensuring their effectiveness, particularly in the food industry; for example, the bioactive peptides produced from bacteria (

Phaseolus lunatus) can be protected from the gastrointestinal environment by microencapsulation obtained from maltodextrin/gun-Arabic [

18]. This evolving method allows for preserving microbial isolates [

8]. Additionally, encapsulation can facilitate controlled release and optimize delivery to the target site, thus enhancing the effectiveness of probiotics. This process also prevents these microorganisms from proliferating in food, which could otherwise alter their sensory characteristics [

19].

The application of microencapsulation technology and thermal protection agents has been extensive, as evidenced by the studies conducted by Misra

, et al. [

20]. Spray drying, known for its cost-effectiveness and high yield efficiency, is recognized as one of the predominant methods for probiotics. However, Yao

, et al. [

21] observed that Lactobacillus plantarum 550 lost all viability during spray drying. Thus, to enhance cell survival, proteins and polysaccharides were commonly added alongside bacteria, forming probiotic microcapsules. Within the scope of probiotic research, a wide array of methodologies has emerged for the microencapsulation of probiotic bacteria in various substances. Some of the materials commonly chosen for this purpose include whey and soy proteins, alginates, pea proteins, acacia, pectins, chitosan, and carrageenans [

22].

Additionally, proteins find frequent use as wall materials for encapsulating probiotics through spray drying. They swiftly generate protective layers around the cells, thereby safeguarding probiotic bacteria from the detrimental impact of thermal stress [

23]. Nevertheless, there remains an absence of thorough exploration into the mechanisms that govern the application of diverse proteins as wall materials to protect probiotics during the spray drying procedure.

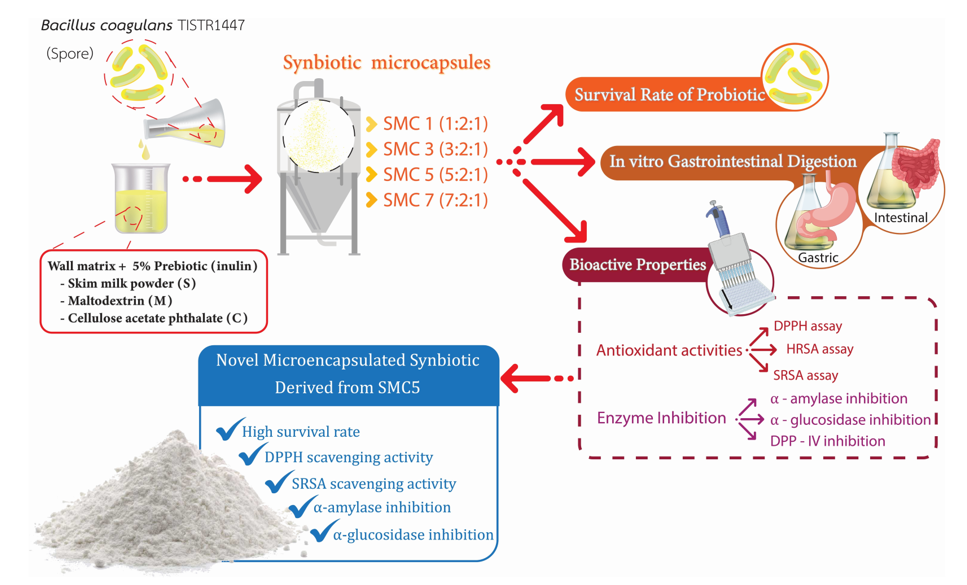

To the author's knowledge, there is currently no information available about the combination of a synbiotic that includes B. coagulans spores with the wall materials like skim milk powder, maltodextrin, and cellulose acetate phthalate, along with the addition of the prebiotic inulin. Thus, this research aims to explore the impact of various encapsulation materials on the viability of probiotic B. coagulans spores, and their multifunctional bioactive properties related to health-promoting under spray drying; these attributes include antioxidant and antidiabetic activities. In addition, the viability of the B. coagulans spores during simulated gastrointestinal digestion was also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The probiotic B. coagulans (TISTR 1447) culture was obtained from the Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research (TISTR) for our study at Maejo University's Food Safety and Biotechnology Lab. Gastrointestinal fluids were simulated using pepsin porcine (P6887) and pancreatin (P7545) from Sigma-Aldrich Co. in the United States. Analytical quality standards were met by all other chemicals used in the study.

2.2. Production of spore suspensions

The production followed the methodology outlined by Russell

, et al. [

24] with minor adjustments. In the first step, sporulation in

B. coagulans TISTR 1447 was initiated by cultivating cells in Nutrient Broth (37°C for 24 h); then, it underwent aerobic growth on Nutrient Yeast Extract Salt Medium agar (37°C for 24 h). The second step, culturing in NYSM broth, involved using a single colony from the agar plate, which was shaken at 250 rpm and maintained at 37°C for five days, resulting in a 90% sporulation rate. Bacterial sediment was successfully obtained by subjecting a bacterial suspension to centrifugation at 4,000 ×g for 10 minutes, followed by washing and resuspension in one hundred microliters of 0.9% Sodium Chloride Sterile Saline. To effectively eliminate vegetative bacterial forms, a heat sterilization process was employed (80°C for 15 min). The spore suspension was subsequently serially diluted and subcultured onto Nutrient Yeast Extract Salt Medium agar. Finally, a working solution with a concentration of 1×10

10 cfu/g was stored under refrigerated conditions for future applications.

2.3. Production of synbiotic microcapsules by spray drying

The preparation of microencapsulation beads adhered to the methodology delineated by Arslan-Tontul and Erbas [

25], albeit with minor adaptations. In this process, the encapsulation of B. coagulans spores within a probiotic culture was executed by dissolving these spores within a 200 ml aqueous solution. This solution comprised a blend of skim milk powder, maltodextrin, and cellulose acetate phthalate in varying ratios, specifically set at 1:2:1, 3:2:1, 5:2:1, and 7:2:1, and was fortified with 5% (w/v) inulin, a recognized prebiotic. Subsequently, the entire mixture underwent sterilization through a heating regimen at 121°C for a duration of 15 minutes, thereby yielding synbiotic microcapsules of distinct formulations, designated as SMC1, SMC3, SMC5, and SMC7. After the solutions were allowed to cool,

B. coagulans spores were introduced into the mixture, in a proportion of 20% v/w, relative to the mass of the wall materials. This introduction maintained an initial cell count of 1×10

10 cfu/g within the microencapsulation process. These inoculated solutions underwent microencapsulation using a laboratory-scale spray dryer, specifically the Buchi-290 from Switzerland. The control of temperatures, with an inlet temperature of 120°C and an outlet temperature of 50°C. In a two-fluid nozzle system, compressed air at 0.3 bar is used to aspirate, and the feeding rate of the solutions is approximately 16.5 ml/min. A cyclone separated the synbiotic microcapsules, accumulating them in a designated vessel. The collected microcapsules were then preserved at -18°C for subsequent analysis. Control conditions were also instituted wherein the inoculated solutions were omitted. The survival rate after the spray drying process was computed as follows:

N represents the count of bacterial cells released from the microencapsulated particles after undergoing a spray drying process (measured in log cfu/g), while N0 denotes the count of unencapsulated cells before this drying process (measured in log cfu/g).

2.4. Bioactive properties of symbiotic microcapsules

2.4.1. 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging

The assessment of DPPH free radical scavenging was carried out using a previously described assay by Yan, Li, Yue, Wang, Zhao, Evivie, Li and Huo [

7]. Some modifications were made to adapt this method for the microplate technique. In the first step, one hundred microliters of the sample or buffer (used as the positive control) were mixed with one hundred microliters of an ethanolic DPPH radical solution at a concentration of 0.2 mM or absolute ethanol (utilized as the blank). In the second step, the mixture was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes, and then the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. To calculate the DPPH radical scavenging activity, the following equation was used:

2.4.2. Hydroxyl radical scavenging (HRSA)

The assessment of HRSA was conducted using a previously described assay by Yan, Li, Yue, Wang, Zhao, Evivie, Li and Huo [

7]. Some modifications were made to adapt this method for the microplate technique. In the first step, the reaction mixture was prepared, including a 3 mM solution of 1,10-phenanthroline in water (50 µl), 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 (50 µl), the samples (50 µl), and 3 mM FeSO4 (50 µl) in a 96-well microplate. In the second step, a 20 mM hydrogen peroxide solution (50 µl) was added to initiate the reaction, which was followed by incubation at 37°C for 90 minutes. Subsequently, the absorbance at 517 nm was measured, and the determination of hydroxyl radical scavenging ability was performed as follows:

2.4.3. Superoxide radical scavenging

The determination of superoxide radical scavenging ability (SRSA) was carried out through the utilization of the method as outlined by Yan, Li, Yue, Wang, Zhao, Evivie, Li and Huo [

7], with slight adjustments made to adapt it for a 96-well clear flat-bottom plate.

Initially, 80 µl of the sample or deionized water (employed for the control group) was combined with 80 µl of Tris-HCl solution (pH 8.2). Following this, the resulting mixture was subjected to incubation at 25°C for 20 minutes. Subsequently, the addition of 40 µl of 25 mM pyrogallol in 10 mM HCL was undertaken, and the mixture was permitted to stand at room temperature for 4 minutes. The determination of superoxide anion radical scavenging activity was conducted as delineated:

The results have been presented as EC50 values, which indicate the sample concentrations needed to scavenge 50% of DPPH, HRSA, and SRSA. These EC50 values were determined by utilizing a linear regression curve derived from a range of sample concentrations from 0.05 to 12.0 mg/ml.

2.4.4. In vitro activities of α-glucosidase

The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was ascertained utilizing a method previously delineated by Zhang

, et al. [

26], with minor adjustments. In summary, the combination of 50 µL of our samples with 50 µL of a 10 mM PNP-glycoside solution (dissolved in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.9) took place within a 96-well microplate. Subsequently, 50 µL of 0.2 U/mL of α-glucosidase enzyme solution was added to initiate the reaction. The microplate was then positioned in an incubator pre-set at 37°C for 30 minutes. P-nitrophenol release from PNP-glycoside was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm employing a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific™, USA). Acarbose was evaluated through the same procedure and functioned as our positive control. The extent of α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was determined in the following manner:

2.4.5. In vitro activities of α-amylase

The determination of α-amylase inhibitory activity was carried out using a method previously documented by Mudgil

, et al. [

27], with some adjustments. This adapted approach employed p-nitrophenyl α-D maltohexaoside (pNPM; 5 mmol/l) as the substrate. To elucidate the procedure, a mixture of 50 µl of pNPM, 50 µl of our samples, and 50 µl of the PPA enzyme solution (50 mg/ml) in a sodium phosphate buffer (0.02 M, pH 6.9) was combined, followed by incubation for 30 minutes at 37°C. Subsequently, the release of p-nitrophenol at 405 nm was monitored. The extent of α-amylase inhibitory activity was computed as follows:

where A1 represents the absorbance of the reaction wells containing both the enzyme and the test sample, while A2 represents the absorbance of the reaction blank with only the test sample and no enzyme. A3 corresponds to the absorbance of the control with the enzyme but without the test sample, and finally, A4 denotes the absorbance of the control blank without both the enzyme and the test sample.

2.4.6. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibition

The inhibitory activity of DPP-IV was assessed following the method outlined by Sangsawad

, et al. [

28], with minor adjustments. Specifically, a twenty-five microliter aliquot of the diluted sample (diluted in a 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.0) was combined with twenty-five microliters of the prepared 1.6 mM Gly-Pro-p-nitroanilide substrate. The sample-substrate mixture was pre-incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C. Following this, fifty microliters of DPP-IV (0.01 U/ml) were added, and the reaction proceeded for 60 minutes at 37°C. One hundred microliters of 1.0 M sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.0 were added to stop the reaction, and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm. The absorbance values were then normalized against sample blanks, where DPP-IV was substituted with Tris-HCl buffer. Negative controls (representing no DPP-IV activity) and positive controls (indicating DPP-IV activity without an inhibitor) were prepared by replacing the sample and DPP-IV solution with Tris-HCl buffer, respectively. The DPP-IV inhibition rate for each sample was calculated as follows:

The IC50 values for each sample were determined via curve interpolation, indicating the synbiotic microcapsule concentration needed to reach a 50% inhibition of the initial enzyme reaction rate.

2.5. In vitro simulation of gastrointestinal digestion

The methodology described by Liu

, et al. [

29] was employed for

in vitro simulated digestion. Several steps were involved in the process: First, a mixture of 0.32 g of pepsin and 0.2 g of sodium chloride in 100 ml of deionized water was prepared to create Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF). Subsequently, the pH of the SGF was adjusted to 2.0 using a 0.1 M HCl (hydrochloric acid) solution. Additionally, 0.1 g of trypsin and 0.08 g of porcine bile salt were added to a 0.2 M PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) solution to prepare Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF). Both the SGF and SIF were preheated in a water bath set to 37°C (to mimic the human body's temperature) for 20 minutes. They were then carefully filtered through a 0.22 µm filter membrane to remove impurities. Next, 0.1 g of the powdered sample or 0.1 ml of a bacterial solution was added to 9.9 ml of SGF, and the mixture was agitated at a constant temperature of 37°C to simulate normal bodily conditions. At specific time intervals (30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes), 0.1 ml of the solution was withdrawn using a sterile pipette or syringe. After the SGF digestion, ten ml of SIF was promptly added for simulated intestinal digestion, ensuring thorough mixing. Finally, at 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours, 0.1 ml was retrieved from the diluted mixture and plated for counting.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The experiments were conducted in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the results were subjected to one-way ANOVA. A p-value of < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the means of the samples.

3. Results and Discussion

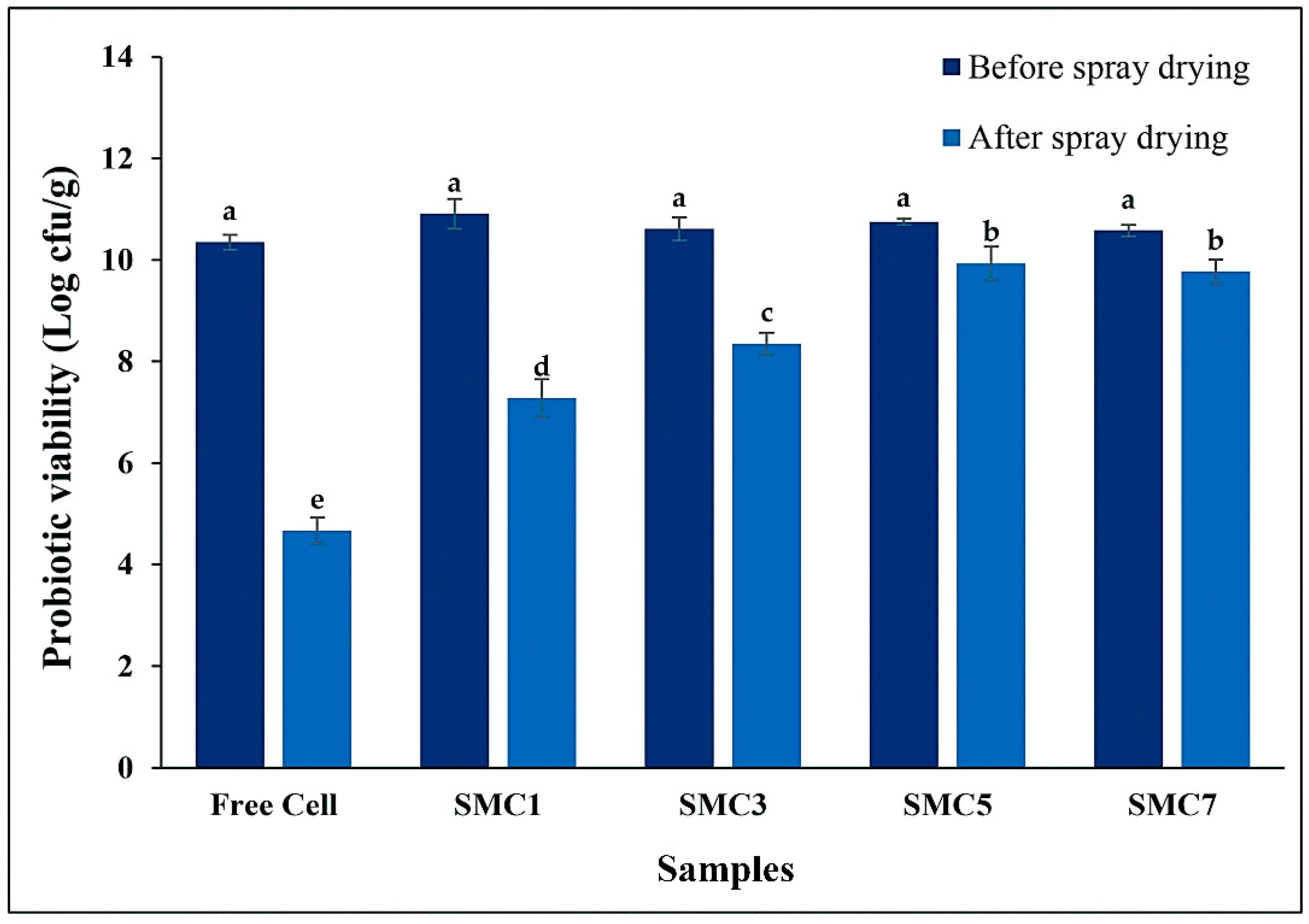

3.1. The effects of microencapsulation and spray drying on the survival rate

Figure 1 depicts the survival rates of

B. coagulans cells encapsulated within various wall matrix ratios subsequent to the spray-drying process. The investigation unveiled that unrestrained

B. coagulans cells underwent a decrement in viability as a consequence of the aforementioned spray-drying procedure, manifesting a reduction in viability of approximately 4.67 log cfu/g, while maintaining an initial probiotic count consistent across all specimens, approximately at 10.64 log cfu/g. This diminishment in viability during the spray-drying phase is ascribed to factors such as heat-induced stress, desiccation, and exposure to ambient oxygen, collectively exerting an impact on the metabolic activity of microbial cells, resulting in a decreased viability. Consequently, following the spray-drying process, distinct wall matrices (designated as SMC1-7) demonstrated a spectrum of probiotic survival rates.

As the concentration of skim milk powder within the encapsulant agents escalated, there was a concomitant augmentation in the viability rate of the encapsulated probiotics. More specifically, SMC1, comprising 23.75% skim milk powder, evinced a viability rate of 66.73%, while SMC3 (containing 47.50% skim milk powder), SMC5 (consisting of 59.38% skim milk powder), and SMC7 (with 66.50% skim milk powder) manifested viability rates of 78.70%, 92.37%, and 92.34%, respectively. These findings unmistakably delineate a robust association between the concentration of skim milk powder and the viability rate of the probiotics enclosed within. It is noteworthy that when skim milk powder is employed in limited proportions; it may prove inadequate in constructing the requisite stable and protective encasements around the microbial cells, potentially leading to an encumbered encapsulation process wherein the cells are not fully enveloped or adequately shielded within the capsules [

30]. Conversely, elevated concentrations of skim milk powder may furnish a surfeit of both quantity and quality in terms of wall materials, thereby facilitating effective encapsulation, averting cell diffusion, and preserving viability [

31]. Consequently, this study has brought to light that the conditions characterized by SMC5 and SMC7 emerge as the optimal parameters for microencapsulation, particularly with regard to the augmentation of

B. coagulans spore viability post the spray-drying operation.

3.2. Bioactivity of the encapsulated products

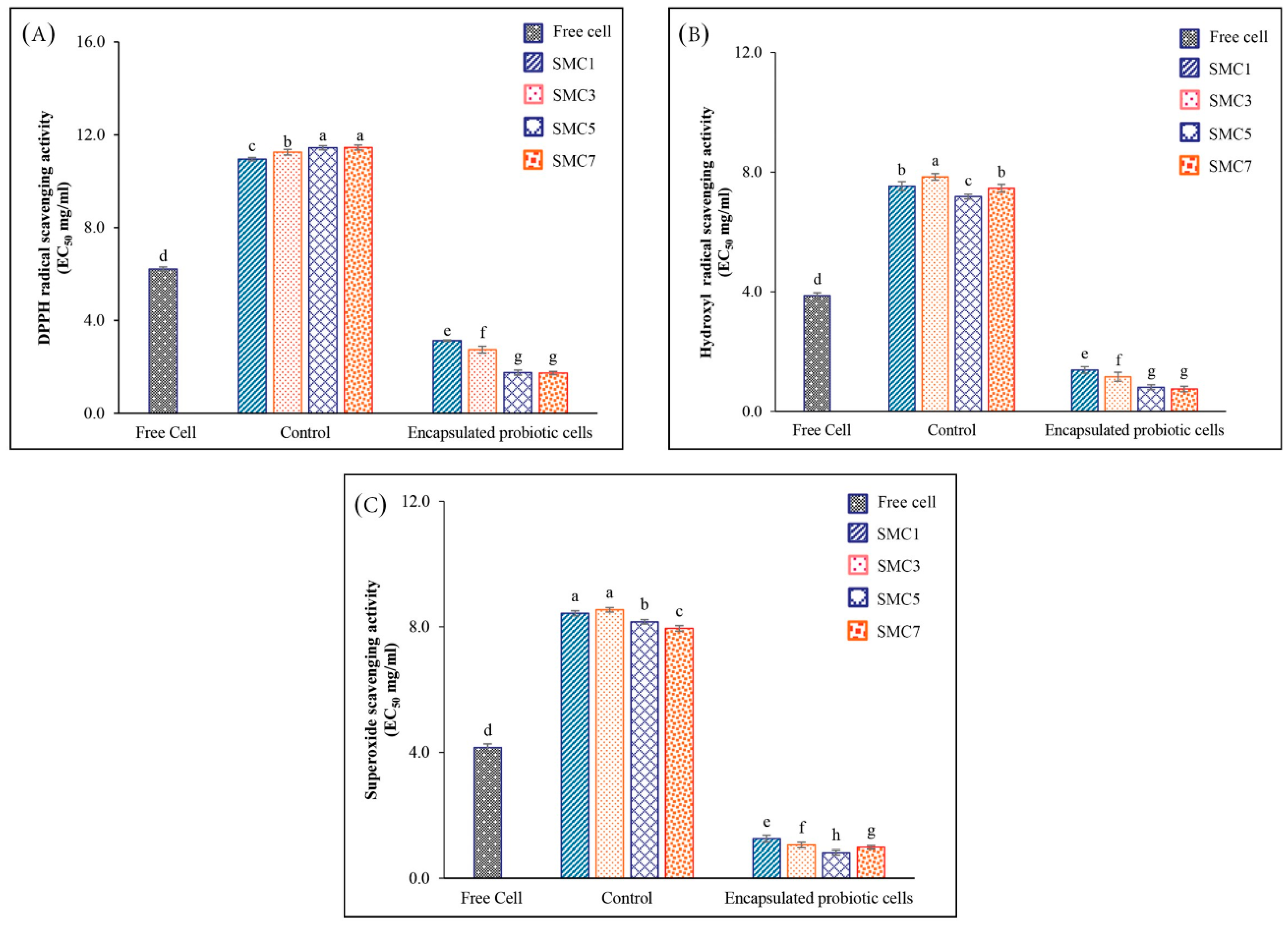

3.2.1. In vitro antioxidant activities

Oxidative stress, characterized by elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), is linked to various forms of cellular damage and chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases in humans, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer [

32]. While synthetic antioxidants have traditionally been employed to protect against oxidative stress, concerns have arisen regarding their safety and long-term effects. Consequently, researchers have focused on natural antioxidant solutions, including probiotics [

32]. Numerous chemical analyses employing diverse techniques have been performed to evaluate the antioxidant properties of the compounds of interest. The incorporation of these chemical analyses, which operate through a variety of mechanisms, can be instrumental in shedding light on the primary modes of action of these antioxidant compounds.

In our experimental findings, it was discerned that the encapsulated samples, denoted as SMC1-7, exhibited a notable reduction in the EC

50 value in comparison to the free cells, as illustrated in

Figure 2A–C. These observations underscore the advantageous influence of encapsulation on the antioxidant activity exhibited by

B. coagulans metabolites and spores, particularly in their proficiency to counteract DPPH radicals, hydroxyl radicals, and superoxide radicals. Intriguingly, both SMC5 and SMC7 manifested the most diminished EC

50 values for DPPH and hydroxyl radical scavenging activities when juxtaposed with the other specimens. A lower EC

50 value signifies a heightened potency in the scavenging activity against hydroxyl radicals, indicative of their pronounced efficacy in the realm of antioxidants, particularly concerning mechanisms involving hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), single electron transfer (SET), and the quenching of hydroxy radicals. Among oxygen radicals, hydroxyl radicals are renowned for their extraordinary reactivity and their proclivity to inflict extensive damage upon adjacent biomolecules. This oxidative damage encompasses processes associated with aging, the genesis of cancer, and the onset of various pathological conditions [

33].

In addition, SMC5 demonstrated the lowest EC

50 value of 0.82 mg/ml for superoxide radical scavenging activity, a reactive oxygen species involved in oxidative stress. Probiotics like B. coagulans are well-known for their ability to produce antioxidant metabolites such as butyrate, glutathione (GSH), and folate [

34]. These metabolites indirectly reduce oxidative stress and enhance the absorption of dietary antioxidants [

35,

36]. Furthermore, the study conducted by Kodali and Sen [

35] sheds light on the role of

B. coagulans in influencing the composition and activity of the gut microbiota. A balanced gut microbiota is crucial for maintaining an overall antioxidant balance, and

B. coagulans may enhance antioxidant activity by promoting a healthy balance of gut bacteria.

Nonetheless, our observations revealed a noteworthy distinction in the antioxidant potential between the control sample, consisting of encapsulated materials devoid of

B. coagulans metabolites and spores, and both the free cell and encapsulated probiotic cell counterparts. The control samples, containing skim milk powder, exhibited markedly diminished antioxidant potency, as evidenced by the highest recorded EC

50 value in comparison to the free cell and encapsulated probiotic cell variants. This peculiarity in the control samples' antioxidant activity can be ascribed to the presence of casein compounds within skim milk powder. Specifically, the amino acid composition of casein encompasses amino acids endowed with antioxidant properties, such as cysteine and methionine, integrated into its molecular structure [

37]. Consequently, our investigation unequivocally elucidated that the SMC5 condition emerges as the preeminent choice for the development of microencapsulated

B. coagulans products, endowed with heightened antioxidative capabilities, equipping them with the capacity to counteract the deleterious effects of free radicals.

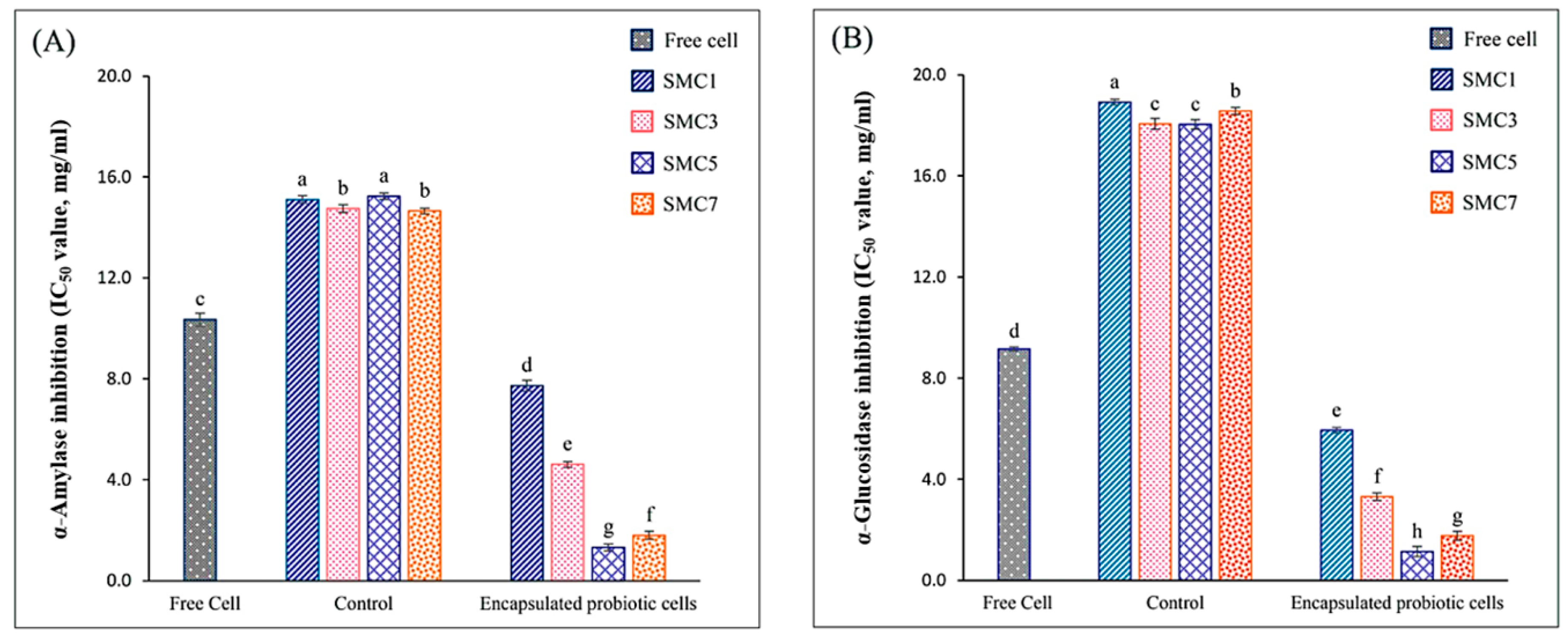

3.2.2. α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disease marked by elevated blood glucose levels, resulting in long-term damage to the heart, blood vessels, eyes, kidneys, and nerves. One primary approach to diabetes management involves inhibiting the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates, such as α-amylase, which gradually increases blood sugar levels after meals. It can effectively control post-meal blood glucose spikes [

38]. Furthermore, another enzyme called α-glucosidase plays a role in carbohydrate digestion. It functions in the small intestine, breaking down disaccharides and complex carbohydrates into glucose and other simple sugars. Inhibiting α-glucosidase delays glucose absorption from the gut into the bloodstream, helping to lower post-meal blood sugar levels [

39].

Within the ambit of our study, it was ascertained that all microencapsulated products exhibited a heightened degree of inhibitory activity against α-amylase in comparison to their free-cell counterparts. Among the various microcapsules investigated, SMC1 displayed the least inhibition of α-amylase activity, even when juxtaposed against all other microcapsules, as graphically represented in

Figure 3A. Remarkably, SMC5 showcased the most robust inhibitory activity against α-amylase, as substantiated by an IC

50 value of 1.32 mg/ml. Intriguingly, these observed activities appeared to remain unaffected by alterations in the ratio of skim milk within the microcapsules. Notably, SMC5's inhibitory potency against α-amylase surpassed that of acarbose, a pharmaceutical agent commonly employed for the management of diabetes through the inhibition of carbohydrate digestion. The IC

50 value for acarbose stood at 1.42 mg/ml (data not presented here). Our findings harmonize with those delineated by Li

, et al. [

40],, who also documented a favorable correlation between the presence of

B. coagulans and the inhibition of α-glucosidase activity.

Among the various microcapsulated products, SMC5 stands out for displaying the highest α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, with a notably low IC

50 value of 1.15 mg/ml, as demonstrated in

Figure 3B. These imply that microcapsules have the potential to delay the absorption of glucose from the intestines into the bloodstream, which could be advantageous in managing post-meal blood sugar levels. It's important to highlight, however, that SMC5 still exhibits lower efficacy compared to acarbose, a synthetic α-glucosidase inhibitor with an IC

50 value of 0.033 mg/ml (data not presented). Consequently, our research underscores SMC5 as the preferred choice for developing microencapsulated

B. coagulans products with antidiabetic properties, enabling them to inhibit both α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities proficiently.

Among the diverse array of microencapsulated products examined, SMC5 distinctly emerges as the frontrunner, showcasing the most pronounced α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, characterized by an exceptionally low IC

50 value of 1.15 mg/ml, as graphically delineated in

Figure 3B. These observations suggest that microcapsules possess the capacity to retard the absorption of glucose from the intestinal tract into the circulatory system. This phenomenon holds promise in the management of postprandial blood glucose levels. It is of paramount importance to underscore, however, that SMC5, despite its commendable efficacy, still exhibits a lower potential in comparison to acarbose, a synthetic α-glucosidase inhibitor boasting an IC

50 value of 0.033 mg/ml (data not presented herein). Consequently, our research underscores the paramount suitability of SMC5 for the development of microencapsulated

B. coagulans products with antidiabetic attributes, endowing them with the capacity to inhibit both α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities.

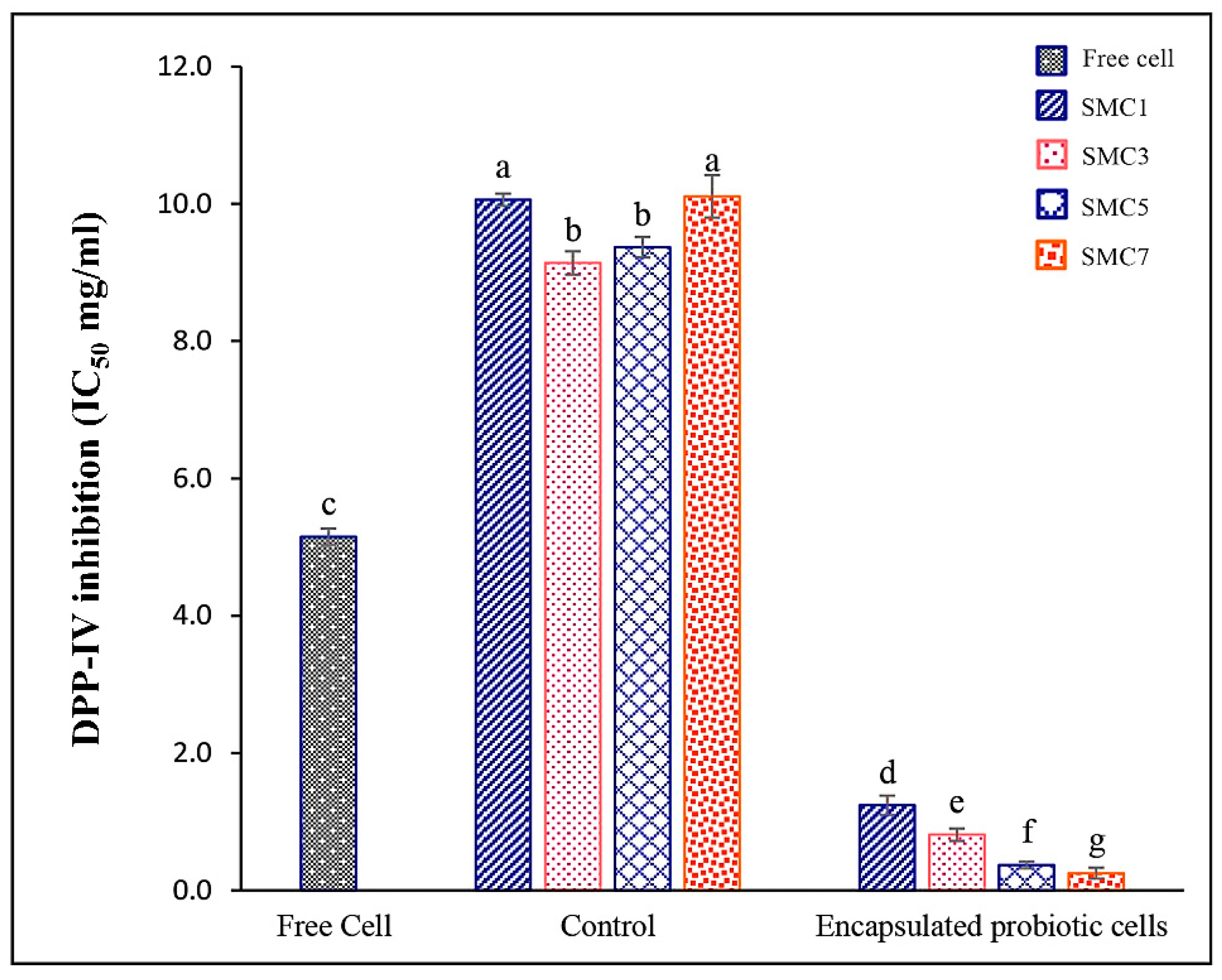

3.2.3. DPP-IV Inhibitory activity

DPP-IV is a crucial enzyme involved in the breakdown of incretin hormones like glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which plays a key role in regulating blood sugar levels. Inhibiting DPP-IV leads to increased levels of active GLP-1, enhancing insulin secretion and lowering blood sugar levels [

41].

In our empirical findings, it was discerned that among the gamut of microcapsules under scrutiny, SMC7 notably exhibited the highest degree of DPP-IV inhibitory activity, as underscored by its IC

50 value of 0.25 mg/ml (

Figure 4). Subsequently, SMC5 emerged as the second-most efficacious, yielding an IC

50 value of 0.37 mg/ml. When assessing the overarching proficiency in enzyme inhibition across diverse wall matrices, the hierarchy of efficacy was delineated as follows: SMC7 > SMC5 > SMC3 > SMC1 > free probiotic cells > control samples (comprising encapsulated materials bereft of

B. coagulans spores). It was observed that the concentration of skim milk bore a dose-dependent influence on the enhancement of DPP-IV inhibition. Additionally, the control samples exhibited some degree of inhibitory activity, attributed to the presence of casein components replete with small peptides. These peptides, coexistent with casein, have been extensively investigated for their multifaceted bioactive attributes, encompassing potential health benefits such as hypertension mitigation and immune system modulation [

42]. Our findings align with the work conducted by Mudgil

, et al. [

43], who reported the plausible DPP-IV-inhibitory activity of probiotic strains, suggesting potential improvements in blood glucose regulation. These insights hold implications for ameliorating fasting blood glucose levels in individuals afflicted with type 2 diabetes and enhancing glucose tolerance. Such discernments are poised to inform dietary choices for diabetic patients and contribute to the development of safer and more efficacious pharmaceutical agents in the foreseeable future.

The encapsulation processes of SMCs played a vital role in improving their bioactive activities. These bioactivities were found to correlate with the survival rates, as depicted in

Figure 1. Notably, SMC 5 and SMC 7 exhibited the highest survival rates after the spray drying process. This observation suggests that skim milk is a critical component for their effectiveness and demonstrates stronger inhibitory activity. As a result, these two conditions hold the potential to offer enhanced therapeutic benefits, especially in processes like the spray drying of

B. coagulans.

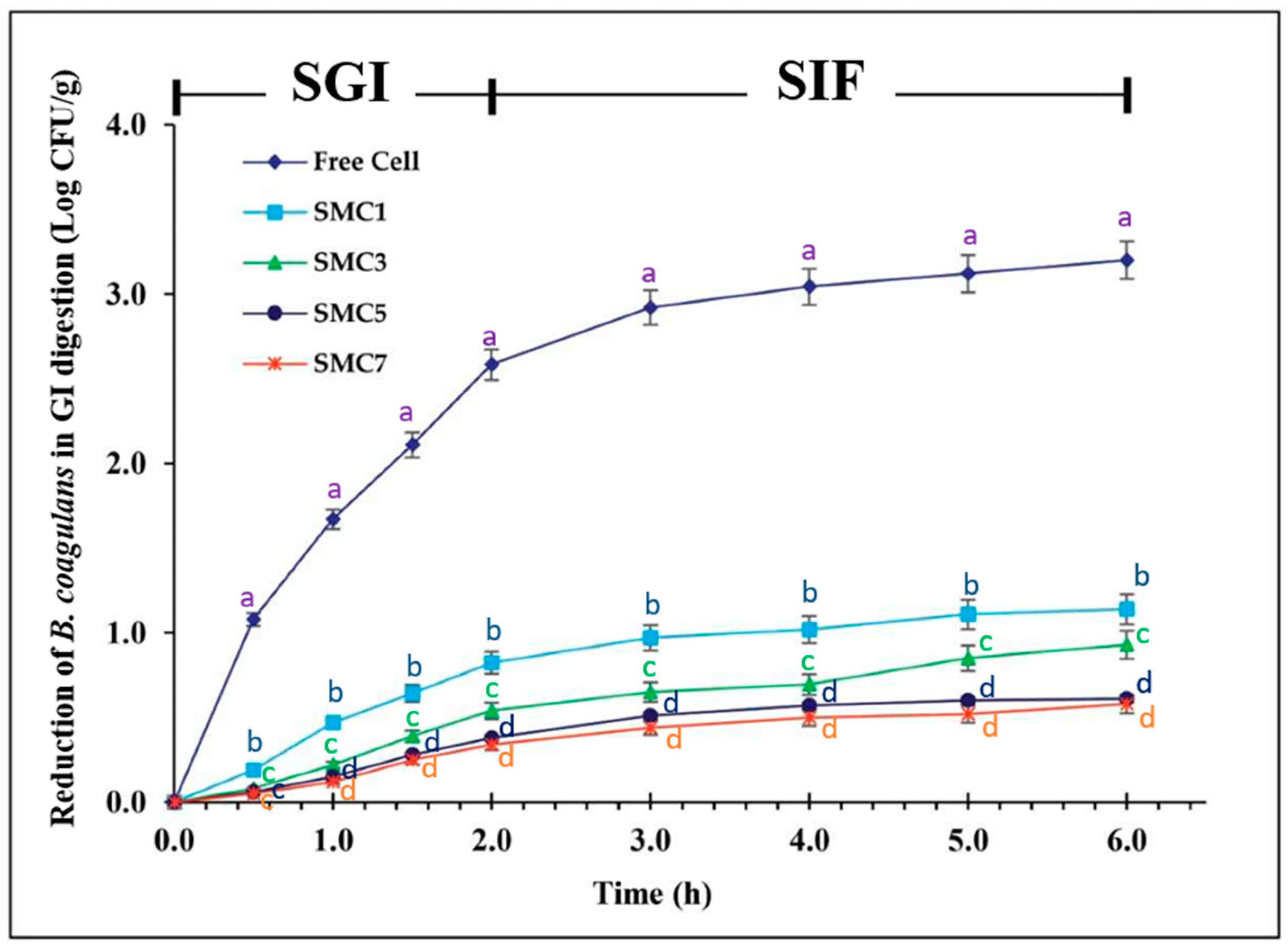

3.3. The survival rate during in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal digestion

Figure 5 portrays the viability profiles of both free and microencapsulated

B. coagulans cells, employing various wall materials denoted as SMCs, throughout a six-hour simulation mimicking gastrointestinal digestion. The unfettered cells demonstrated a decline in viability amounting to 3.2 log cfu/g over the entire duration of the digestion process. Of particular note, all samples encapsulated within SMCs exhibited markedly superior survival rates subsequent to the simulated gastrointestinal digestion in comparison to their free-cell counterparts. This enhancement was substantiated by a diminution in viability of less than 1.0 log cfu/g. These findings underscore the efficacy of microencapsulation employing a protein-based coating augmented with prebiotic inulin in significantly bolstering the survivability of probiotic entities within the simulated gastric and intestinal environments, surpassing the resilience of unencapsulated spores.

Notably, these rates still exceeded the recommended 6 log cfu/g set by the International Dairy Federation (

Figure 1). The SMC7 sample exhibited the highest cell survival, with only a decrease of 0.58 log cfu/g during gastrointestinal digestion, followed by the SMC5 sample, which was nonsignificant different from SMC7 with a loss of 0.93 log cfu/g, and the SMC1 sample, with a loss of 1.14 log cfu/g.

Our experimental endeavors have effectively demonstrated that microencapsulation serves as a protective shield for the B. coagulans probiotic, effectively insulating it from the formidable gastric milieu characterized by low pH levels and the presence of digestive enzymes in the intestinal tract. This protective mechanism holds the promise of conferring an array of health benefits upon oral consumption. It is noteworthy that our findings underscore the nuanced impacts of microencapsulation, a phenomenon contingent upon both the selection of coating materials and the specific physiological conditions encountered within the digestive tract.

Furthermore, our investigation sought to evaluate the bioactive activity of these encapsulated samples; however, it was observed that these samples were subjected to a high concentration of gastrointestinal salts, gastrointestinal enzymes, and bile salts. Consequently, our research focused exclusively on the assessment of survival rates, given the substantial interference posed by the factors mentioned above on the bioactive potential of the probiotics.

4. Conclusions

This study revealed that a novel microencapsulated product derived from the SMC5 and SMC7 ratios exhibited the most potent ability to preserve B. coagulans spores by enhancing the survivability of B. coagulans cells during the spray-drying process compared to the conditions with free cells. Additionally, the SMC5 samples exhibited the most potent antioxidant activity with DPPH, hydroxy radicals, superoxide radical scavenging, and antidiabetic activities, including α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitions. In comparison, SMC7 demonstrated the most potent antidiabetic activity by inhibiting DPP-IV. Subsequently, after simulating gastrointestinal digestion, SMC5 and SMC7 showed a slight decrease in spore viability during the 6-hour simulation. Thus, the most suitable condition for synbiotic production is SMC5, which involves encapsulating 5% inulin with a mixture of skim milk powder, maltodextrin, and cellulose acetate phthalate in a ratio of 5:2:1. This formulation has the potential to protect B. coagulans spores, demonstrate bioactive activities after microencapsulation, and successfully survive gastrointestinal digestion. This innovative product can be utilized as an advanced food delivery system and as a functional ingredient in functional foods. Nevertheless, this report requires further research to pinpoint the bioactive metabolite responsible for the observed activities and to conduct experiments involving animals and humans to evaluate the effectiveness of SMC5.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., P.S. and K.N.; methodology, S.S., P.S., N.N. and K.N.; formal analysis, S.S., P.S., N.N., S.K. and K.N.; investigation, S.S., P.S. and K.N.; resources, S.S. and P.S.; writing-original draft preparation, S.S. and P.S.; writing-review and editing, S.S., P.S., N.N., P.J., S.K. and K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) under the project no. MJ.1-65-003.5, Maejo University (MJU) and Suranaree University of Technology (SUT).

Informed Consent Statement

All study participants provided informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The article contains the data and materials supporting the conclusions of this study.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all contributors to this document.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Poshadri, A.; HW, D.; UM, K.; SD, K. Bacillus Coagulans and its Spore as Potential Probiotics in the Production of Novel Shelf-Stable Foods. Current Research in Nutrition & Food Science 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Khedkar, S.; Carraresi, L.; Bröring, S. Food or pharmaceuticals? Consumers' perception of health-related borderline products. PharmaNutrition 2017, 5, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeer, S.; Bron, P.A.; Marco, M.L.; Van Pijkeren, J.-P.; Motherway, M.O.C.; Hill, C.; Pot, B.; Roos, S.; Klaenhammer, T. Identification of probiotic effector molecules: present state and future perspectives. Current opinion in biotechnology 2018, 49, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiepś, J.; Dembczyński, R. Current trends in the production of probiotic formulations. Foods 2022, 11, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, M.; Natarajan, S.; Sivakumar, A.; Ali, F.; Pande, A.; Majeed, S.; Karri, S. Evaluation of anti-diarrhoeal activity of Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 and its effect on gastrointestinal motility in Wistar rats. International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences 2016, 7, P311. [Google Scholar]

- Altun, G.K.; Erginkaya, Z. Identification and characterization of Bacillus coagulans strains for probiotic activity and safety. LWT 2021, 151, 112233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Li, N.; Yue, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, L.; Evivie, S.E.; Li, B.; Huo, G. Screening for potential novel probiotics with dipeptidyl peptidase IV-inhibiting activity for type 2 diabetes attenuation in vitro and in vivo. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 10, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Altieri, C.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. Microencapsulation of saccharomyces cerevisiae into alginate beads: A focus on functional properties of released cells. Foods 2020, 9, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inatsu, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Yuriko, Y.; Fushimi, T.; Watanasiritum, L.; Kawamoto, S. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis strains in Thua nao, a traditional fermented soybean food in northern Thailand. Letters in applied microbiology 2006, 43, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hindi, R.R.; Abd El Ghani, S. Production of functional fermented milk beverages supplemented with pomegranate peel extract and probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Journal of Food Quality 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhiainen, T.; Collin, M.; Narva, M.; Cheng, Z.J.; Poussa, T.; Vapaatalo, H.; Korpela, R. Effect of long-term intake of milk peptides and minerals on blood pressure and arterial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Milchwissenschaft-Milk Science International 2005, 60, 358–362. [Google Scholar]

- Razmpoosh, E.; Javadi, A.; Ejtahed, H.S.; Mirmiran, P.; Javadi, M.; Yousefinejad, A. The effect of probiotic supplementation on glycemic control and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized placebo controlled trial. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2019, 13, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, Y. The hypocholesterolaemic effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus American Type Culture Collection 4356 in rats are mediated by the down-regulation of Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1. British Journal of Nutrition 2010, 104, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirabunyanon, M.; Boonprasom, P.; Niamsup, P. Probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented dairy milks on antiproliferation of colon cancer cells. Biotechnology letters 2009, 31, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, J.A.; Forsythe, P.; Chew, M.V.; Escaravage, E.; Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'mahony, L. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind comparison of the probiotic bacteria lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirjavainen, P.V.; Salminen, S.J.; Isolauri, E. Probiotic bacteria in the management of atopic disease: underscoring the importance of viability. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2003, 36, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cian, R.E.; Campos-Soldini, A.; Chel-Guerrero, L.; Drago, S.R.; Betancur-Ancona, D. Bioactive Phaseolus lunatus peptides release from maltodextrin/gum arabic microcapsules obtained by spray drying after simulated gastrointestinal digestion. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2019, 54, 2002–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Gupta, R.; Chawla, S.; Gauba, P.; Singh, M.; Tiwari, R.K.; Upadhyay, S.; Sharma, S.; Chanda, S.; Gaur, S. Natural sources and encapsulating materials for probiotics delivery systems: Recent applications and challenges in functional food development. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 971784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, S.; Pandey, P.; Mishra, H.N. Novel approaches for co-encapsulation of probiotic bacteria with bioactive compounds, their health benefits and functional food product development: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 109, 340–351. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Liu, B.; He, L.; Hu, J.; Liu, H. The incorporation of peach gum polysaccharide into soy protein based microparticles improves probiotic bacterial survival during simulated gastrointestinal digestion and storage. Food Chemistry 2023, 413, 135596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, E.; Ziarno, M.; Ekielski, A.; Żelaziński, T. Materials used for the microencapsulation of probiotic bacteria in the food industry. Molecules 2022, 27, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, S.; Janfaza, S.; Tasnim, N.; Gibson, D.L.; Hoorfar, M. Microencapsulating polymers for probiotics delivery systems: Preparation, characterization, and applications. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 120, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.; Jelley, S.; Yousten, A. Selective medium for mosquito pathogenic strains of Bacillus sphaericus 2362. J Appl Environ Microbiol 1989, 55, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan-Tontul, S.; Erbas, M. Single and double layered microencapsulation of probiotics by spray drying and spray chilling. Lwt-food science and technology 2017, 81, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Deng, Z.; Ramdath, D.D.; Tang, Y.; Chen, P.X.; Liu, R.; Liu, Q.; Tsao, R. Phenolic profiles of 20 Canadian lentil cultivars and their contribution to antioxidant activity and inhibitory effects on α-glucosidase and pancreatic lipase. Food chemistry 2015, 172, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudgil, P.; Jobe, B.; Kamal, H.; Alameri, M.; Al Ahbabi, N.; Maqsood, S. Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV, α-amylase, and angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory properties of novel camel skin gelatin hydrolysates. LWT 2019, 101, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsawad, P.; Katemala, S.; Pao, D.; Suwanangul, S.; Jeencham, R.; Sutheerawattananonda, M. Integrated Evaluation of Dual-Functional DPP-IV and ACE Inhibitory Effects of Peptides Derived from Sericin Hydrolysis and Their Stabilities during In Vitro-Simulated Gastrointestinal and Plasmin Digestions. Foods 2022, 11, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gong, J.; Chabot, D.; Miller, S.S.; Cui, S.W.; Zhong, F.; Wang, Q. Improved survival of Lactobacillus zeae LB1 in a spray dried alginate-protein matrix. Food Hydrocolloids 2018, 78, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Qu, P.; Luo, S.; Wang, C. Potential uses of milk proteins as encapsulation walls for bioactive compounds: A review. Journal of Dairy Science 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, F.; Santos, L. Microencapsulation of caffeic acid and its release using aw/o/w double emulsion method: Assessment of formulation parameters. Drying Technology 2019, 37, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Zucca, P.; Varoni, E.M.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Tsouh Fokou, P.V.; Azzini, E.; Peluso, I. Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Frontiers in physiology 2020, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.J.; Park, J.H.; Lam, Y.; de Lumen, B.O. Characterization of lunasin isolated from soybean. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2003, 51, 7901–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Xu, Y.; Dong, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H. The effects of microcapsules with different protein matrixes on the viability of probiotics during spray drying, gastrointestinal digestion, thermal treatment, and storage. eFood 2023, 4, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, V.P.; Sen, R. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of an exopolysaccharide from a probiotic bacterium. Biotechnology Journal: Healthcare Nutrition Technology 2008, 3, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengül, N.; Aslím, B.; Uçar, G.; Yücel, N.; Işık, S.; Bozkurt, H.; Sakaoğullarí, Z.; Atalay, F. Effects of exopolysaccharide-producing probiotic strains on experimental colitis in rats. Diseases of the colon & rectum 2006, 49, 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Suetsuna, K.; Ukeda, H.; Ochi, H. Isolation and characterization of free radical scavenging activities peptides derived from casein. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2000, 11, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awosika, T.O.; Aluko, R.E. Inhibition of the in vitro activities of α-amylase, α-glucosidase and pancreatic lipase by yellow field pea (Pisum sativum L.) protein hydrolysates. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2019, 54, 2021–2034. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, V.; Huligere, S.S.; Ramu, R.; Naik Bajpe, S.; Sreenivasa, M.; Silina, E.; Stupin, V.; Achar, R.R. Evaluation of probiotic and antidiabetic attributes of lactobacillus strains isolated from fermented beetroot. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 911243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ke, W.; Zhang, Q.; Undersander, D.; Zhang, G. Effects of Bacillus coagulans and Lactobacillus plantarum on the Fermentation Quality, Aerobic Stability and Microbial Community of Triticale Silage. 2023.

- Nongonierma, A.B.; FitzGerald, R.J. Features of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitory peptides from dietary proteins. Journal of food biochemistry 2019, 43, e12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidona, F.; Criscione, A.; Guastella, A.M.; Zuccaro, A.; Bordonaro, S.; Marletta, D. Bioactive peptides in dairy products. Italian Journal of Animal Science 2009, 8, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgil, P.; Aldhaheri, F.; Hamdi, M.; Punia, S.; Maqsood, S. Fortification of Chami (traditional soft cheese) with probiotic-loaded protein and starch microparticles: Characterization, bioactive properties, and storage stability. LWT 2022, 158, 113036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).