1. Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) caused by coronary heart disease (CHD) is the result of one or more coronary artery stenoses [

1]. AMI is included in the cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), which are the leading cause of death in the population, also increasing morbidity and disability [

2]. The stenosis causes ischemia and necrosis of the myocardial tissue due to the absence of blood nourishment; the inflammatory response that occurs in the non-perfused area will generate fibrotic tissue and possible adhesions between the myocardium and the visceral pericardium and/or adhesions between the pericardial leaflets and the myocardium [

1,

2,

3,

4]. One of the elective invasive approaches to reperfuse tissue is the coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).

This practice, especially if performed with median sternotomy, ministernotomy or lateral minithoracotomy, stimulates the post-surgical formation of peritoneal adhesions [

5,

6,

7]. CABG is not free from dangers and complications during and after surgery, which can range from surgical site infection to the appearance of arrhythmias, up to the event of a periprocedural AMI and pleural effusion [

8]. The phrenic nerve can undergo a transient or permanent injury (up to a maximum of 75% of patients), with an ipsilateral elevation of the diaphragm, or in the most severe cases, both domes are dysfunctional [

9]. The intercostal nerves undergo a structural and functional alteration of the myelin and meningeal layers, and the appearance of fibrosis [

10]. Another event that can slow down the post-surgical course is ipsilateral shoulder pain (ISP), which pain can affect up to 97% of patients undergoing CABG [

11]. Other areas of the body are tender after sternotomy, such as the neck area, causing the patient to take more pain relievers [

12]. The case report presents a patient with chronic nonspecific neck pain (NNP) in the presence of pericardial adherence following thoracentesis and prior CABG. To the knowledge of the authors, it is the first article illustrating an osteopathic approach with resolution of NNP, with a manual technique on the pericardial area.

2. Case Presentation

A 36-year-old male patient with previous cardiac surgery in median sternotomy, not infarcted, is examined for NNP in the cervical area. Surgery was performed five years earlier, with double CABG (obtuse marginal branch1-posterior interventricular coronary artery-saphenous vein). Four days after surgery, the patient underwent thoracentesis due to a left pleural effusion involving the pleural space up to the sixth rib. Drugs currently taken are aimed at blood pressure control (beta-blocker and ACE inhibitor), and for the presence of hypercholesterolemia and dyslipidemia (statins). The patient complains of pain and stiffness throughout the posterior cervical area, without irradiation, with movement limitations that increase with rotations and inclinations of the neck to the right.

The relief came from the extension, and from the opposite rotation and inclination. The deep pain is intermittent and is present only with active and passive (performed by the operator) right movements. Once a day, the patient takes a pain reliever (NSAID). The patient does not report direct trauma or cervical pathologies or axial alterations with negative results through previous instrumental tests (magnetic resonance and x-rays). Blood tests do not highlight systemic diseases (infections, arthritis or autoimmune diseases, metabolic/endocrine diseases).

Air saturation was 100%, and with complete absence of dyspnea. With the visual analogue scale (VAS), if pain was solicited, the score was six; the neck disability index (NDI) reported a value of 24 (moderate disability). We excluded patent foramen ovale (PFO), which can be a source of neck pain, because it was not present during surgery. We have excluded carotid diseases (stenosis, dissections), which can cause pain in the neck, thanks to the color Doppler ultrasound of the carotids previously performed by the patient, before the osteopathic visit. We excluded the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) as the origin of the symptoms, due to the absence of popping, clicking or crepitus, as well as the lack of pain and muscle tension on movement and palpation by the osteopath (pterygoid, temporal, masseters), and no hearing disorders and/or alterations of the dental class. The patient denies bruxism or nocturnal snoring. We excluded Eagle's syndrome and hyoid bone syndrome due to the lack of related symptoms (dysphagia, odynophagia, etc.) and to palpation of the hyoid bone. We performed several manual differentiation tests (less specific like the O'donoghue's test or more specific like the Sharp-Purser test), but always inconclusive. The cervical compression and distraction tests were also negative.

We manually evaluated the vertebrae that most affect rotation and inclination, such as the first two cervical vertebrae (affect total rotation about 63-73%), C3-C4 and C6-C7 (affect inclination about 11.7-20.3%), respectively [

13]. By isolating the movements of the individual facet joints, we did not find anomalies such as to explain the limitation of movements or any trigger for the onset of pain. Palpation of the cervical musculature and of the posterior cervicothoracic area revealed tissue suffering of the deep muscles, but not of the more superficial muscles. Considering that scars may be a source of symptoms not necessarily at the site of the lesion, we evaluated the sternal scar and the area of the sixth posterolateral intercostal space (access area for thoracentesis), manually [

14]. With small delicate pressures with open palm on the scar area, we induced micro-movements (caudal, cranial, right, and left direction, oblique and rotational movements), to try to highlight possible adhesion brakes or possible pain. The induced micromovements were strongly limited in the followed directions, but without pain, indicating a possible presence of adhesions under the scar areas. Adherent lesions between the serous cavities and the lungs and/or pericardium following surgery are common [

15]. To try to identify the probable source of neck movement limitation and pain, we performed a manual inhibition test.

This test consists in pressing a tissue area (sternum), while with the other hand resting on the symptomatic area (the neck); the clinician tries to perceive a change in tone. Finally, the cervical spine area is pressed, and the response is felt from the sternal area [

16]. The tissue that does not show any tone variation is, very similarly, the area of symptomatological derivation. In this case, the sternal and thoracentesis access area were the areas where the tissue tone did not change. Performing the Bordoni diaphragmatic test (BDT), the outcome gave a positive result of dysfunction of the diaphragm muscle [

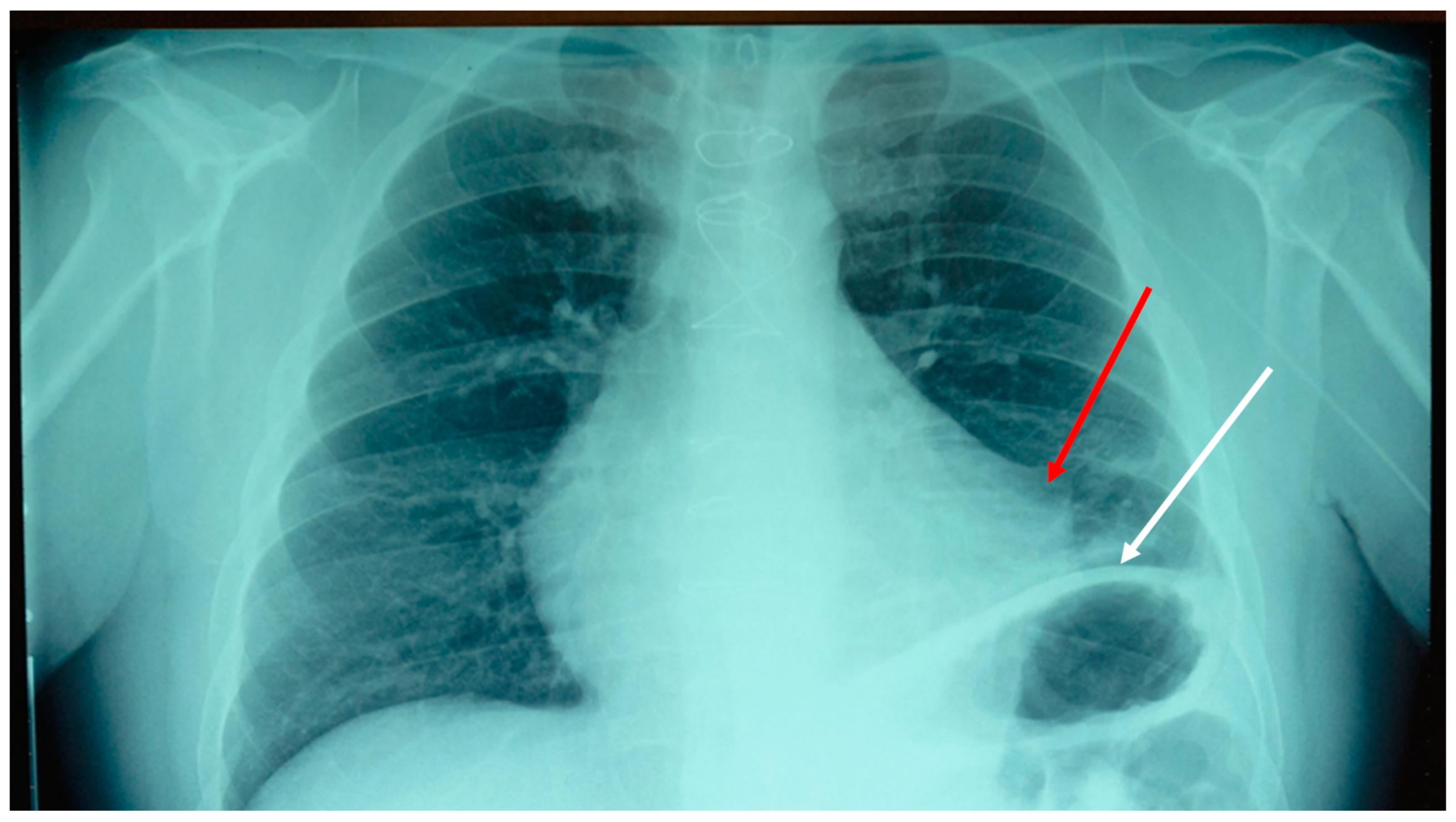

17]. It was decided to take a chest x-ray (

Figure 1).

The result of the instrumental examination highlighted an adherence between the pericardium and the pleura in the left mediastinal area, and an elevation of the left hemidiaphragm. We decided to do an osteopathic treatment with a technique used in a previous trial, that is, an indirect approach [

18]. The goal was to reduce pain and improve movement function. The clinician places one palm on the sternal area (involving the anterior pericardial area) and the other hand, open posteriorly, on the vertebral area of T10-T12; the latter thoracic area corresponds to the posterior attachment of the pericardium [

19].

With this manual support to the chest, we try to "enclose" the pericardial area. The clinician does not induce any movement but follows the movement of the tissues underlying the hands; when the perceived tissue displacement is homogeneous in amplitude, traction force and times of expression, the technique can be said to be finished. The patient remains seated, while the operator is seated next to the patient. The application time can last several minutes. At the end of the osteopathic technique, reevaluating the patient, the active and passive movements of the neck had no limitations; proposing the previous assessment scales (VAS and NDI), the patient did not complain of any pain. After a week, the patient (contacted by telephone) described the recurrence of pain but with a much-reduced entity compared to the period preceding the osteopathic treatment, and without taking NSAIDs.

Movements were unrestricted. It was decided to see the patient again (one week after the first treatment), using the same osteopathic approach. After two weeks the perceived pain was further decreased, but constantly present, and neck movements improved more. After 3 months of treatment with the same approach, with one monthly session, there was no limitation of movements (rotation and tilt to the right); the pain returned two weeks after the visit with the osteopath, but the painful entity perceived by the patient had greatly decreased, with a VAS score of 1 and NDI with a value of 10 (minimum disability). It was decided, in agreement with the patient, to have one session every six months, as maintenance therapy.

3. Discussion

There are many symptoms that can derive from adhesions, such as local and/or referred pain, or they can give symptoms not necessarily related to pain, such as being the cause of constrictive pericarditis [

20]. In this case report, a gentle osteopathic approach drastically reduced the symptoms of NNP in a patient with previous CABG and previous thoracentesis for left pleural effusion. The adhesion formed after thoracentesis united the left parietal pleura and the ipsilateral parietal pericardial area, forming nonphysiologically mechanical tractions. We can hypothesize that these new force vectors from the viscera may have conditioned the surrounding tissues, such as the diaphragm (through the lower triangular ligaments of the lung and the pericardial-diaphragmatic fascia), pulling the left hemi-cupola upwards. We know that the presence of pleural effusion pushes the corresponding portion of the diaphragm downwards, while thoracentesis helps diaphragmatic repositioning [

21]. Probably, a possible concomitant lesion of the phrenic nerve (not evaluated), and the presence of visceral mediastinal adhesions, could have facilitated the cranial movement of the diaphragm muscle. The same adhesions present in the patient could have created traction towards the mediastinum of the connected fascial structures. The endothoracic fascia, which covers the pleurae and pericardium, derives from the deep fasciae of the neck, such as the investing, pretracheal and prevertebral fascia. The investing fascia attaches to the nuchal ligament and mastoid process of the temporal bone [

22]. The pretracheal layer involves the base of the skull up to the pericardium posteriorly, while the prevertebral fascia fuses with the vertebrae of the cervicothoracic tract, the nuchal ligament and the deep musculature of the cervical vertebrae, as well as at the base of the skull and the Sibson's fascia (pleural dome) [

22]. We can assume that the non-physiological force vectors generated by the visceral adhesion towards the mediastinum could be the cause of a mechanical imbalance expressed by the neck. In fact, the action of bringing the neck to the right (inclination and rotation), created a strong limitation with the onset of pain, while an extension and inclinations / rotations to the left allow the symptoms to cease.

The present pain could be connected to the mechanical tension generated by visceral adhesion, stimulated whenever the neck moved to the right. The nervous pathways put under tension are the same ones that innervate the pleural, pericardial area (vagus nerve and sympathetic system) [

22]. Noxious information can derive from the respiratory viscera (stimulation of the P2X3 receptors) due to the presence of non-physiological mechanical tensions [

23]. Similarly, altered mechanical tensions involving the pericardium (stimulating metabotropic glutamate receptors), can cause somato-visceral nociceptive afferents [

24].

Muscle motor fibers traveling with the cervical and mediastinal fascia can be negatively solicited by mechanical tension abnormalities and form nociceptive information: movement with pain [

22]. The phrenic nerve itself can carry in an afferent way nociceptive information for mechanical disturbances, which nociception can be expressed in distant muscle or joint areas of the neck [

25]. It should be added that, in acute and chronic situations of non-specific neck pain, there is an alteration of the perception of local pain (mechanical hyperalgesia), with central sensitization, respectively [

26].

The osteopathic manual approach carried out in this case report finds its clinical validity in a previous trial, where we demonstrated that by working on the mediastinal area, the patient recovers his motor performance more quickly and with a significant decrease in pain perception [

18]. The reasons that have made it possible to improve the clinical picture of the patients are not fully elucidated. The difference with the previous study is that in this clinical case the position of the hands mirrored the position of the pericardial area. This is the first report that allows to eliminate NNP, working the pericardial area with osteopathic treatment. The real reasons for the benefit achieved by the patient need to be investigated.