Submitted:

15 September 2023

Posted:

20 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

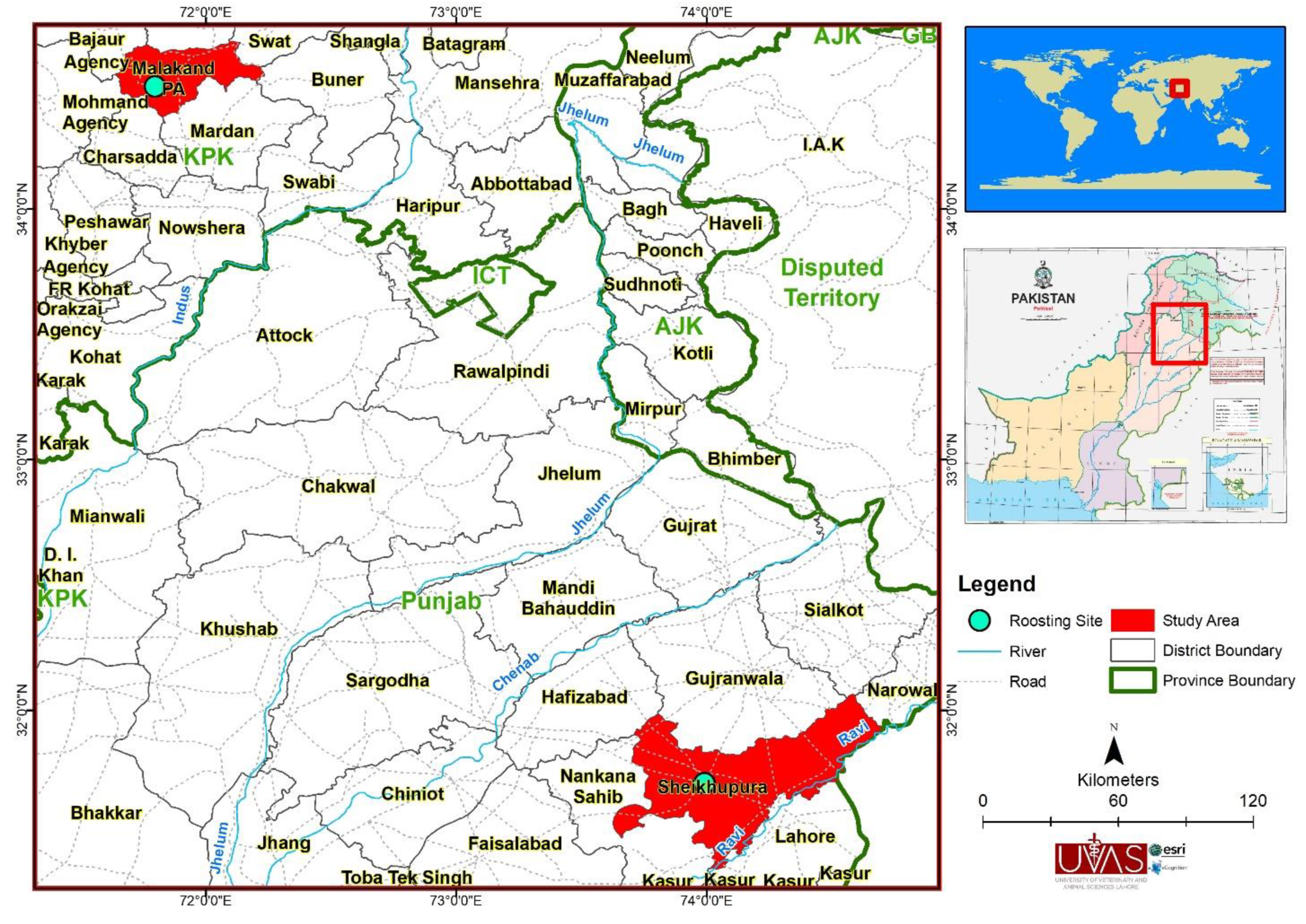

2.1. Study area

2.2. Collection of samples and data

2.3. Isolation and phenotypic identification of bacteria

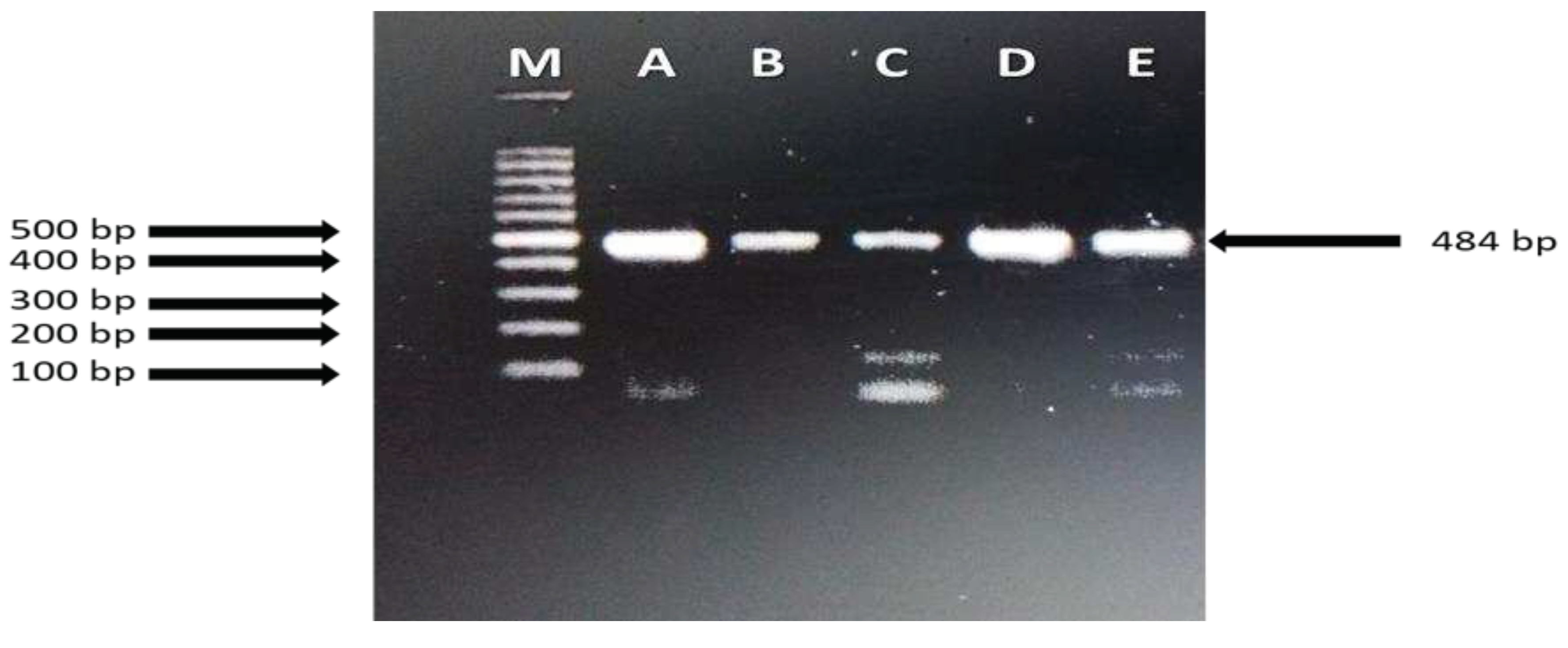

2.4. Molecular confirmation of bacteria

2.5. Phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance profiling

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

| Bat species | Swabs collected | S. aureusPrevalence (%) | ||

| Oral/Rectal (no. each) |

Oral (95% CI) |

Rectal (95% CI) |

Total (95% CI) |

|

| Pipistrellus javanicus | 17/17 | 11.76 (1.46 – 36.44) |

11.76 (1.46 – 36.44) |

23.52 (6.81 – 49.89) |

| Pipistrellus pipistrellus | 10/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhinopoma microphyllum | 48/48 | 2.08 (1.31 – 17.20) |

10.42 (3.47 – 22.58) |

12.5 (4.73 – 25.25) |

| Rousettus leschenaultii | 124/124 | 12.90 (11.47 – 25.62) |

20.16 (17.66 – 33.57) |

37.90 (29.35 – 47.05) |

| Scotophilus kuhlii | 1/1 | 0 | 100 (2.50 – 100) |

100 (2.50 – 100) |

| Total | 200/200 | 13.50 (9.10 – 19.03) |

19.50 (14.25 – 25.68) |

29.00 (22.82 – 35.82) |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahmood ul Hassan, M.; Nameer, P.O. Diversity role and threats to the survival of bats in Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant. Sci. 2006, 16, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood-ul-Hassan, M.; Jones, G.; DietzI, C. Bats of Pakistan. The least known mammals. Verlag Dr. Muller, Saarbrucken, Germany. 2009, pp.168.

- Turmelle, A.S.; Olival, K.J. Correlates of viral richness in bats (order Chiroptera). Eco Health. 2009, 6, 522–539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Letko, M.; Seifert, S. N.; Olival, K. J.; Plowright, R. K.; Munster, V. J. Bat-borne virus diversity, spillover and emergence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strahan, R. (ed.). Mammals of Australia.1995. Reed.

- Hall, L.; Richards, R. Flying foxes and fruit and blossom bats of Australia. Australian Natural History Series. 2000. UNSW Press.

- Wilkinson, G.S.; South, J.M. Life history, ecology and longevity in bats. Aging Cell. 2002, 1, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisher, C.H.; Childs, J.E.; Field, H.E.; Holmes, K.V.; Schountz, T. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol. 2006, 19, 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Plowright, R.K.; Foley, P.; Field, H.E.; Dobson, A.P.; Foley, J.E.; Eby, P.; Daszak, P. Urban habituation, ecological connectivity and epidemic dampening: the emergence of Hendra virus from flying foxes (Pteropus spp.). Proc Biol Sci. 2011, 278, 3703–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibbelt, G.; Kurth, A.; Yasmum, N.; Bannert, M.; Nagel, S.; Nitsche, A.; Ehlers, B. Discovery of herpesviruses in bats. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 2651–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julg, B.; Elias, J.; Zahn, A.; Koppen, S.; Becker-Gaab, C.; Bogner, J.R. Bat-associated histoplasmosis can be transmitted at entrances of bat caves and not only inside the caves. J. Travel. Med. 2008, 15, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, Jr.; JO, Ritzi.; C.M.; Dick, C.W. Collecting and preserving bat ectoparasites for ecological study. Ecological and behavioral methods for the study of bats. JHU Press. 2009, 2, 806–827.

- Muhldorfer, K.; Speck, S.; Wibbelt, G. Diseases in free-ranging bats from Germany. BMC Vet Res. 2011, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, J.; Gmeiner, M.; Mordmüller, B.; Matsiegui, P.B.; Schaer, J.; Eckerle, I.; Schaumburg, F. Bats are rare reservoirs of Staphylococcus aureus complex in Gabon. Infect Genet Evol. 2016, 47, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.Y.; Schaumburg, F.; Ellington, M. J.; Corander, J.; Pichon, B.; Leendertz, F.; Giffard, P. M. 2015. Novel staphylococcal species that form part of a Staphylococcus aureus-related complex: the non-pigmented Staphylococcus argenteus sp. nov. and the non-human primate-associated Staphylococcus schweitzeri sp. nov. Int. J.Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Dupieux, C.; Blondé, R.; Bouchiat, C.; Meugnier, H.; Bes, M.; Laurent, S.; Tristan, A. Community-acquired infections due to Staphylococcus argenteus lineage isolates harbouring the Panton-Valentine leucocidin, France, 2014. Eurosurveillance. 2015, 20, 21154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chantratita, N.; Wikraiphat, C.; Tandhavanant, S.; Wongsuvan, G.; Ariyaprasert, P.; Suntornsut, P.; Peacock, S.J. Comparison of community-onset Staphylococcus argenteus and Staphylococcus aureus sepsis in Thailand: a prospective multicentre observational study. Clin. Microbiol. Ifect. 2016, 22, 458–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schaumburg, F.; Pauly, M.; Anoh, E.; Mossoun, A.; Wiersma, L.; Schubert, G.; Peters, G. Staphylococcus aureus complex from animals and humans in three remote African regions. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 345–e1. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, S. , Sherman, D. J.; Silhavy, T. J.; Ruiz, N.; Kahne, D. Lipopolysaccharide transport and assembly at the outer membrane: the PEZ model. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016, 14, 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Tulsiani, S.M.; Cobbold, R.N.; Graham, G.C.; Dohnt, M.F.; Burns, M.A.; Leung, L.P.; Craig, S.B. The role of fruit bats in the transmission of pathogenic leptospires in Australia. Ann Trop Med Parasite. 2011, 105, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brygoo, E.R.; Simond, J.P.; Mayoux, A.M. The pathogenic enterobacteria of Pteropus rufus (Megachiroptera) in Madagascar. Societé de biologie de Madagascar. Bactériologie. 1971, 165, 1793–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Adesiyun, A.A.; Stewart-Johnson, A.; Thompson, N.N. Isolation of enteric pathogens from bats in Trinidad. J. Wild. Dis. 2009, 45, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes A., W. B.; Rovira, H.G.; Masangkay, J.S.; Ramirez, T.J.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Baticados, W.N. Polymerase chain reaction assay and conventional isolation of Salmonella spp. from Philippine bats. Acta. Sci. Vet. 2011, 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Akobi, B.; Aboderin, O.; Sasaki. T.; Shittu, A. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from faecal samples of the straw-colored fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) in Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), Nigeria. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 1–8.

- Vandžurová, A.; Bačkor, P.; Javorský, P.; Pristaš, P. Staphylococcus nepalensis in the guano of bats (Mammalia). Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 164, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Febler, A.T, Thomas P.; Mühldorfer, K.; Grobbel, M.; Brombach, J.; Eichhorn. I.; Monecke, S.; Ehricht, R.; Schwarz, S. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from zoo and wild animals. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 218, 98–103.

- Mairi, A.; Touati, A.; Pantel, A.; Yahiaoui Martinez, A.; Ahmim, M.; Sotto, A.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Lavigne, J.P. First Report of CC5-MRSA-IV-SCCfus "Maltese Clone" in Bat Guano. Mcrooganisms. 2021, 9, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, F.; Boardman, W.; Power, M. High Prevalence of Beta-Lactam-Resistant Escherichia coli in South Australian Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pups (Pteropus poliocephalus). Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 1589. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Gómez, P.; Alonso, C. A.; Camacho, M.C.; de la Puente, J.; Fernández-Fernández, R.; Torres, C. Detection of MRSA of Lineages CC130-mecC and CC398-mecA and Staphylococcus delphini-lnu (A) in Magpies and Cinereous Vultures in Spain. Microbial Ecology. 2019, 78, 409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, P.; Lozano, C.; Camacho, M.C.; Lima-Barbero, J.F.; Hernández, J.M.; Zarazaga, M.; Torres, C. Detection of MRSA ST3061-t843-mecC and ST398-t011-mecA in white stork nestlings exposed to human residues. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, E.H.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Olival, K.J.; Bogich, T.L.; Johnson, C.K.; Mazet, J.; A.k, Karesh, W.;Daszak. Targeting Transmission Pathways for Emerging Zoonotic Disease Surveillance and Control. Vec-Bor. Zoono Dis 2015, 432–437.

- White, A.; Hughes, J. M. Critical importance of a one health approach to antimicrobial resistance. EcoHealth. 2019, 16, 404–409. [Google Scholar]

- Holt JG. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. vol. 1, Williams and Wilkins. 1986. Baltimore.

- Atyah, M.A.S.; Zamri-Saad, M.; Siti-Zahrah, A. First report of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from cage-cultured tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 144, 502–504. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A.W.; Perry, D.M.; Kirby.; W.M. Drug usage and antibiotic susceptibility of staphylococci. J. A.Med. Ass. 1960, 173, 475–480. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momtaz, H.; Dehkordi, F.S.; Rahimi, E.; Asgarifar, A.; Momeni, M. Virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from chicken meat in Isfahan province, Iran. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2013, 22, 913–921. [Google Scholar]

- Anisimova, E.; Yarullina, D. Characterization of erythromycin and tetracycline resistance in Lactobacillus fermentum strains. Intl. J. Microbiol. 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Strommenger, B.; Kettlitz, C.; Werner, G.; Witte, W. Multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of nine clinically relevant antibiotic resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 4089–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. 2022.https://www.R-project.org/.

- Graveland, H.; Duim, B.; van Duijkeren, E.; Heederik, D.; Wagenaar, J.A. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in animals and humans. Int.J. Med Microbiol. 2011, 301, 630–634. [Google Scholar]

- Olatimehin, A.; Shittu, A.O.; Onwugamba, F.C.; Mellmann, A.; Becker, K.; Schaumburg, F. Staphylococcus aureus complex in the straw-colored fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) in Nigeria. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 162. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xing, Y.; Sun, H.; Mao, X. Gut microbial diversity in two insectivorous bats: Insights into the effect of different sampling sources. Microbiology. Open. 2019, 8, 00670. [Google Scholar]

- Schaumburg, F.; Alabi, A.S.; Köck, R.; Mellmann, A.; Kremsner, P.G.; Boesch, C.; Peters, G. Highly divergent Staphylococcus aureus isolates from African non-human primates. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2012, 4, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, D.R.; Nastase-Bucur, R.M.; Spinu, M.; Uricariu, R.; Mulec, J. Aerosolized microbes from organic rich materials: case study of bat guano from Caves in Romania. J. Cave. Karst. Stud. 2014, 76, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cláudio, V.C.; Gonzalez, I.; Barbosa, G.; Rocha, V.; Moratelli, R.; Rassy, F. Bacteria richness and antibiotic-resistance in bats from a protected area in the Atlantic Forest of Southeastern Brazil. PloS. One. 2018, 13, 0203411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, E. Fruit bats at Ife: their roosting and food preferences (Ife fruit bat project no. 2). Nierian Field. 1974, 39, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Vengust, M.; Knapic, T.; Weese, J.S. The fecal bacterial microbiota of bats; Slovenia. PloS. One. 2018, 13, 0196728. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Gongora, C.; Chrobak, D.; Moodley, A.; Bertelsen, M.F.; Guardabassi, L. Occurrence and distribution of Staphylococcus aureus lineages among zoo animals. Vet Microbiol. 2012, 2, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvin, J.; Lanong, S.; Syiem, D.; De Mandal, S.; Kayang, H.; Kumar, N.S.; Kiran, G.S. Culture-dependent and metagenomic analysis of lesser horseshoe bats’ gut microbiome revealing unique bacterial diversity and signatures of potential human pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 137, 103675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.M.; Kloepper, L.N.; Duncan, M.; McInroy, J.A; Kloepper, J.W. Variation in bat guano bacterial community composition with depth. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 914. [Google Scholar]

- Dimkić, I.; Stanković, S.; Kabić, J.; Stupar, M.; Nenadić, M.; Ljaljević-Grbić,M.; Žikić, V.; Vujisić, P.; Tešević, V.; Vesović, N.; Pantelić, D.; Savić-Šević, S.; Vukojević, J.; Ćurčić, S. Bat guano-dwelling microbes and antimicrobial properties of the pygidial gland secretion of a troglophilic ground beetle against them. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 4109–4126.

- Di-bella, C.; C. Piraino, S.; Caracappa, L.; Fornasari, C.; Violani, B. Zava. Enteric Microflora in Italian Chiroptera. J.Mt Ecol. 2003, 7, 221–224.

- Strommenger, B.; Kehrenberg, C.; Kettlitz, C.; Cuny, C.; Verspohl, J.; Witte, W. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from pet animals and their relationship to human isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Luzzago, C.; Locatelli, C.; Franco, A.; Scaccabarozzi, L.; Gualdi, V.; Viganò, R. Clonal diversity, virulence-associated genes and antimicrobial resistance profile of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from nasal cavities and soft tissue infections in wild ruminants in Italian Alps. Veterinary Microbiol. 2014, 170, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Loncaric, I.; Kunzel, F.; Licka, T.; Simhofer, H.; Spergser, J.; Rosengarten, R. 2014 Identification and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from Austrian companion animals and horses. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 168, 381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Sun, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Cai, T.; Yuan, X.; Hu, G. Prevalence, resistance pattern, and molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from healthy animals and sick populations in Henan Province, China. Gut. Pathog. 2018, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| Factors | Variables | No. samples collected |

Prevalence (%) (95% CI) |

Chi-square χ2 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Castle | 100 | 37.00 (27.57 – 47.24) |

8.60 | 0.01 |

| Cave | 90 | 23.33 (15.06 – 33.43) |

|||

| Animal Shed | 10 | 0 | |||

| Species | Pipistrellus javanicus | 17 | 23.52 (6.81 – 49.89) |

17.90 | < 0.01 |

| Pipistrellus pipistrellus | 10 | 0 | |||

| Rhinopoma microphyllum | 48 | 12.5 (4.73 – 25.25) |

|||

| Rousettus leschenaultii | 124 | 37.90 (29.35 – 47.05) |

|||

| Scotophilus kuhlii | 1 | 100 (2.50 – 100) |

|||

| Age | Adult | 149 | 29.53 (22.34 – 37.55) |

0.01 | 0.91 |

| Juvenile | 51 | 27.45 (15.89 – 41.74) |

|||

| Reproductive Status | Lactating | 2 | 50.00 (1.26 – 98.75) |

5.11 | 0.28 |

| Non-breeding | 90 | 22.22 (14.13 – 32.31) |

|||

| Non-scrotal | 1 | 0 | |||

| Post-lactating | 34 | 29.41 (15.10 – 47.79) |

|||

| Scrotal | 73 | 36.99 (25.97 – 49.09) |

|||

| Sex | Female | 124 | 24.19 (16.95 – 32.70) |

3.07 | 0.08 |

| Male | 76 | 36.84 (26.06 – 48.69) |

|

Antimicrobial class |

Antimicrobial agents |

Conc. (µg) |

Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| S | I | R | |||

| Tetracycline | Tetracycline | 30 µg | 15 (25.86) | 18 (31.03) | 25 (43.10) |

| Erythromycin | Macrolides | 15 µg | 20 (34.48) | 22 (37.93) | 16 (27.58) |

| Gentamicin | Aminoglycosides | 10 µg | 15 (25.86) | 18 (31.03) | 25 (43.10) |

| Total isolates tested | Source of isolation | No. isolates | Antibiotic resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus | |||

| TetK (%) | TetM (%) | ermA (%) | aacA-D (%) | |||

| 58 | Oral | 24 | 17 (70.08) | 18 (75.00) | 8 (33.33) | 15( 62.5) |

| Rectal | 34 | 12 (35.29) | 14 (41.17) | 6 (17.64) | 13 (38.23) | |

| Total | 58 | 29 (50) | 32 (55.17) | 14 (24.13) | 28 (48.27) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).