1. Introduction

The retinal endothelial cell (REC) plays a central role in the developmental formation of the mammalian neural-retinal vasculature [

1]. A retinal specific growth factor Norrin is essential for stimulating the proliferation of the retinal vasculature and recruitment of mural cells [

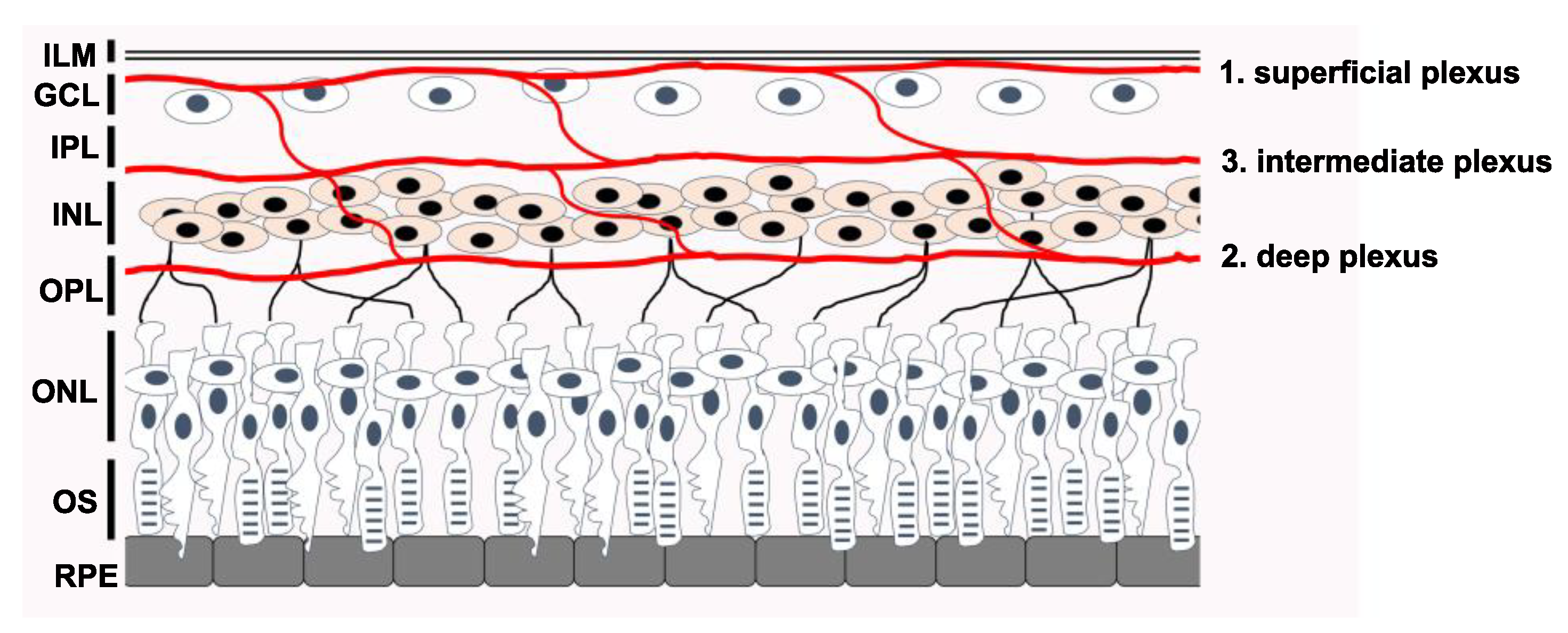

2]. Genetic variants that change normal REC function can potentially impact the development of the entire neural retina and its function. At maturity, three interconnected microvascular beds support the inner neural retina: the Superficial Plexus in the Ganglion Cell Layer (GCL) / Nerve Fiber Layer interface, the Intermediate Plexus on the inner-side of the Inner Nuclear Layer (INL), and the Deep Plexus on the outer-side of the INL. See

Figure 1. We recommend the review by Selvam et al., for those interested in the topic of retinal vascular development [

3].

Inner-retinal neurons (Bipolar Cells, Horizontal Cells, Amacrine Cells and Ganglion Cells) are fully dependent on this inner-retinal vasculature for gas, nutrient and waste exchange. Photoreceptors are less reliant on this vasculature and are supplied by the Choroidal Blood supply which is located on the opposite side of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE). This fact is well demonstrated by the mouse Oxygen-Induced Retinopathy model where inner-retinal neurons are lost during post-natal retinal development in zones that become avascular for several days before neovascular growth restores the blood supply. OCT and ERG analysis show that even with severe inner retinal neuron loss, the photoreceptors are not lost in any substantial numbers, and photoreceptors remain responsive to light [

4,

5,

6].

During normal retinal development, the superficial layer extends first from the optic nerve towards the peripheral retina, resulting from proliferation of advancing retinal endothelial cells [

1]. Vertical branch sprouts form from this layer and follow guidance cues from Muller Glia Cells which extend from the ILM to the outer side of the ONL. The deep plexus then extends horizontally ahead of the intermediate plexus, which forms last. Active proliferation of RECs is essential for the formation of this vasculature and after maturation RECs are essential components of the neurovascular unit that supports formation of the inner blood-retinal-barrier (iBRB) and its high-barrier nature. The iBRB is a highly selective barrier like the Blood-Brain-Barrier (BBB) and indeed the neural retina is part of the Central Nervous System (CNS).

The high-barrier nature of the retinal endothelium is a result of specific adaptions to decrease the permeability of the endothelium both between and through the cells. A relatively high-barrier to paracellular transport, between cells, is provided by high concentrations of adherens- and tight-junctions between neighboring cells [

7]. Reduced concentration of plasmalemma vesicles, which are caveolae vesicles associated with Caveolin protein, is responsible for a lower rate of transcytosis, transport through retinal endothelial cells [

8]. Unlike choroidal endothelial cells, retinal endothelial cells are not fenestrated. The iBRB is compromised in certain pathological eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, which manifests clinically as increased microvascular permeability and subsequent retinal hemorrhages [

9]. Increased concentration of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A is a major driver of barrier loss from disruption of the adherens-junctions and tight-junctions. VEGFA was also shown to increase the concentration of caveolae in bovine RECs [

10].

While RECs are clearly integral to sustaining retinal vascular structure, they are also key players in the development of the early retinal blood supply. Norrie disease, Coats disease, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) belong to a family of rare retinopathies that are characterized by irregular vascularization or even lack of vascularization of the retina [

11]. Our group has contributed to continuing efforts to identify variants in several genes that play a role in the pathogenesis of these diseases, which include

NDP,

FZD4,

TSPAN12, and

LRP5, members of the canonical Norrin Wnt-signaling pathway [

12]. Recent studies have also uncovered additional genes, some that have no direct participation in the Norrin-signaling pathway. They include

CTNNB1, which encodes the canonical Wnt-signaling transcription factor ß-Catenin [

13];

KIF11, which codes for kinesin-motor protein-11, KIF11, active during mitosis [

14]; and

ZNF408, which encodes a zinc-finger rich transcription factor (ZNF408) that has heightened expression in the developing eye [

15].

Despite their distinctively unique cellular roles, these genes all share the following characteristic: variants in their coding sequence will negatively impact essential functions of the retinal endothelial cell and can lead to aberrations in retinal vasculogenesis and/or maintenance of inner BRB integrity. Furthermore, the degree to which they are limited to their specific impact on the neural retinal endothelium, versus multi-syndromic pathologies, tends to reflect the relative specificity of their expression in retinal endothelial cells. This review will provide a brief overview of each of these genes, including the general structure and function of their respective proteins, and their impact on retinal endothelial cell function in the developing retina.

2. Genes and Proteins

For each gene we have included a figure that maps the location of many known pathogenic and likely-pathogenic variants relative to known functional protein domains. Please note that many known variants of

uncertain consequence were not included in the figures, but the reader can also view them in the UniProt database (

https://www.uniprot.org) or other databases with variant information. The reader should also keep in mind that this variant information is not static and reference to online databases is recommended in addition to searches of the recent literature. Below we review seven FEVR-linked genes, beginning with those linked more recently to FEVR, followed by those with direct roles in Norrin Wnt-signaling:

KIF11,

ZNF408,

CTNNB1,

NDP,

FZD4,

LRP5, and

TSPAN12.

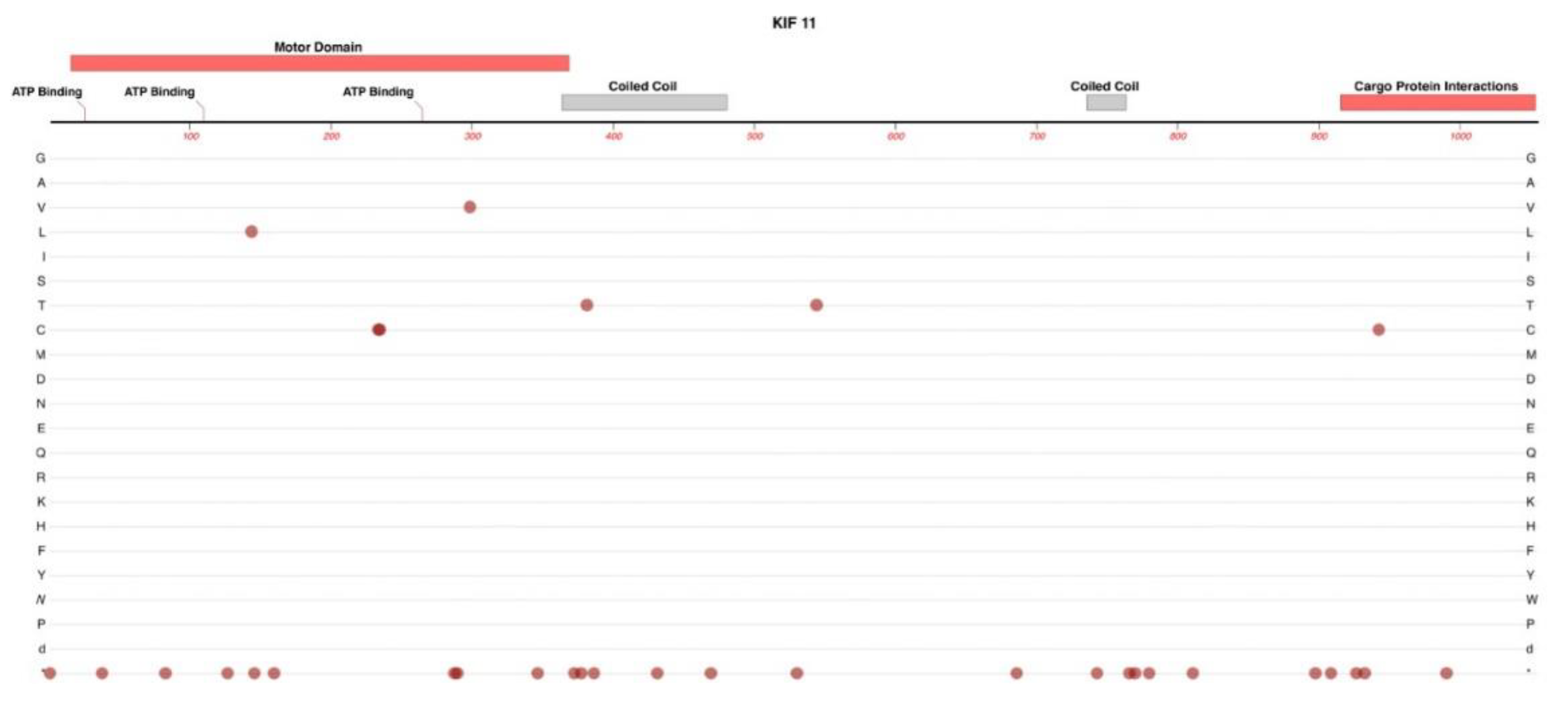

2.1. KIF11

KIF11 is located on Chr-10 that encodes for Kinesin Family member-11 (also known as Eg5) a homo-tetrameric motor protein that is involved in the formation of spindle polarity during mitosis [

16]. KIF-11 consists of three major functional components: an N-terminal motor domain, two coiled-coil domains, and a cargo protein interaction domain at the C-terminal end. A structural map of KIF-11 and the locations of most known pathogenic and likely-pathogenic protein-altering variants is shown in

Figure 2.

Structurally, Kinesin Motor family proteins form dimers or tetramers with the coiled-coiled domains of each monomer entwined with the equivalent domains of their multimeric partners. This elongated structure also serves as a long connecting towbar between the motor-domain region and the cargo binding domain. As such, most of the protein's amino acid sequence is important for movement of KIF11 along microtubules, correct multimeric formations, and for the tethering of any required cargo.

Heterozygous variants in this gene have been linked to microcephaly with or without chorioretinopathy, lymphoedema, or mental retardation (MCLMR), a rare autosomal dominant disease [

17,

18]. However, a recent study by Li et al., have discovered an association with KIF11 variants and the development of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy [

14]. Variants included L171V, Q525*, S936*, and R1025G [

14]. The data suggested that there was a trend between mutations in KIF11 and more severe phenotypic outcomes of FEVR – all probands in one study with KIF11 variants were diagnosed with either stage 4 or 5 FEVR.

Generally, disease-causing KIF11 variants result in multiple syndromic conditions in addition to impacting development of the retinal vasculature. This is congruent with the fact that KIF11 appears to be involved in the process of spindle formation and organization during cell division, a fundamental cellular process not limited to the retinal endothelial cell. It is presumed that the major impact of these disease-causing variants is mostly impacting the normal proliferation and migration of RECs in the developing neural retinal vasculature. Early-post natal, endothelial cell specific, knock-out of KIF11 in the mouse was reported to impair the formation of the retinal and cerebellar vasculature [

19]. The capacity of EC cells for ß-catenin mediated intracellular signal transduction was not impacted. Wang and co-authors have hypothesized that the cerebral and retinal microvasculature may be more sensitive because these vascular beds are the most rapidly growing later in embryonic development.

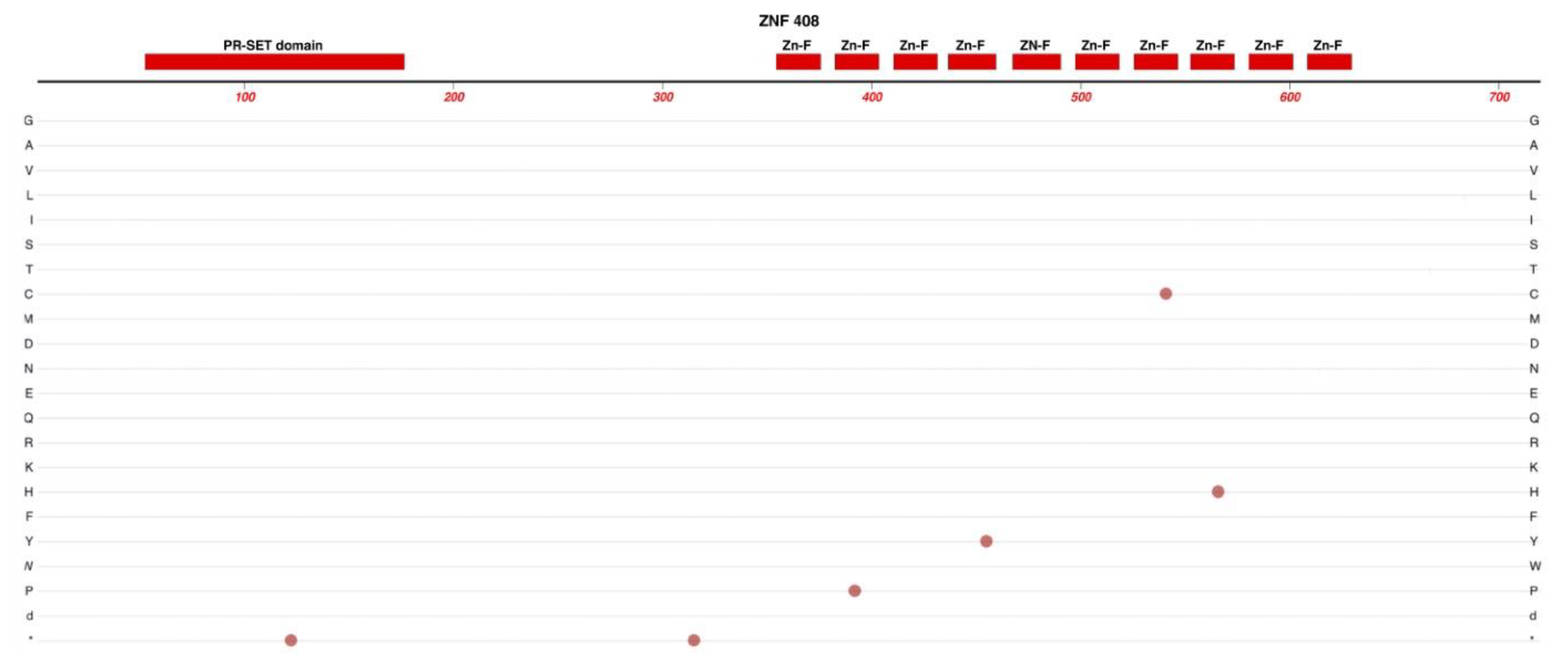

2.2. ZNF408

ZNF408 is located on Chr-11 and encodes a protein consisting of one PR-SET domain and 10 zinc (Zn)-finger domains. See

Figure 3. This protein belongs to the PRDM family (PRDI-BF1 and RIZ homology domain containing) of transcription factors, which are characterized by the presence of a PR domain followed by a variable number of Zn-finger repeats [

20].

The PR-SET domain is involved in the recruitment of chromatin remodeling factors such as those modulating DNA-methylation. Multiple Zn-finger motifs occurring in close sequence are known to provide specific structures for binding interactions with other proteins or for binding to specific DNA-sequences. Members of this protein family can act as transcription factors, regulating a diverse range of function-related gene expression and some aspects of DNA repair [

21].

Changes to the coding sequence of Zn-finger proteins have been associated with aberrations in tissue development, cancer, retinitis pigmentosa, and recent genetic studies have identified several variants associated with FEVR [

15,

22]. For example, the H455Y variant was identified in a family with autosomal-dominant FEVR [

23].

Studies in zebrafish have confirmed that some of these variants resulted in irregular retinal vasculature development, while studies using human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) revealed that variants in ZNF408 reduced endothelial cell capacity for angiogenesis [

15,

23]. While further research is required to identify the specific gene expression changes associated with variants of ZNF408, one hypothesis suggests that variants in ZNF408 results in the decreased transcription of genes responsible for the formation of new capillaries in response to hypoxia[

23].

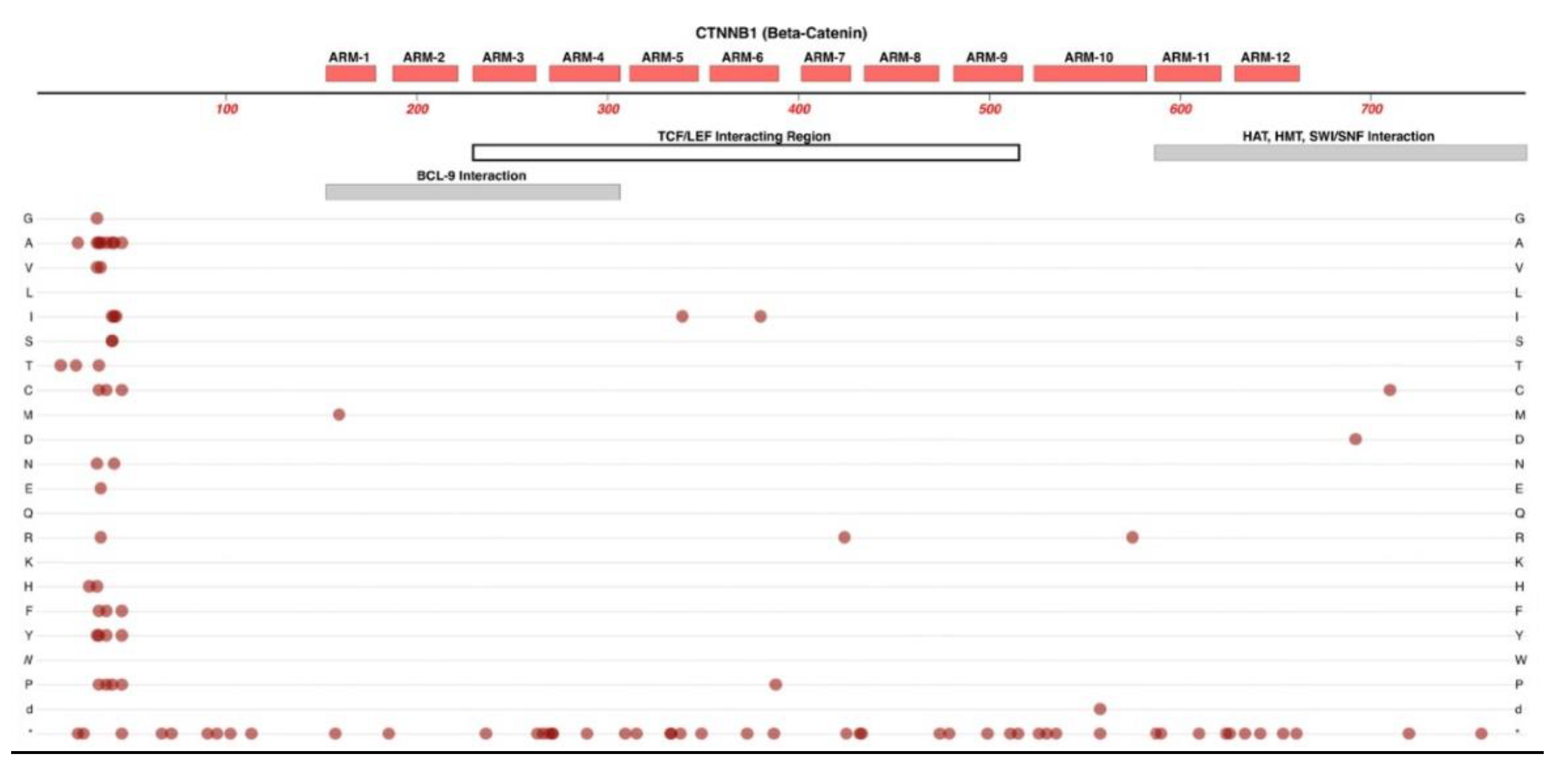

2.3. CTNNB1

Located on Chr-3,

CTNNB1 encodes the protein ß-catenin. Before ß-catenin variants were reported for FEVR, many variants of this gene were already associated with cancers. The roles of ß-catenin can be relatively complex because of its regulatory roles in cell-to-cell adhesion and its pivotal role in canonical Wnt-signaling. Many cancer-related variants are clustered in the N-terminal domain of ß-catenin where they prevent the normal regulatory targeting of the protein to degradation at the proteosome. See

Figure 4. This effectively results in abnormally constant hyperactivity of ß-catenin, which promotes cancer-cell proliferation [

24]. In addition to its central role in Wnt-signaling, most ß-Catenin is associated with E-Cadherin of the adherens-junctions in endothelial cells [

25].

Most of the protein's amino acid sequence comprises 12 ARM motifs, with each ARM region forming an alpha-helical structure. These multiple helixes are stacked together laterally, like logs, with this entire log-stack also twisted into a higher-order helical structure. Most of the length of this large super-structure forms a groove that provides for interactions with proteins such as TCF/LEF transcription factors[

26]. For an excellent and detailed review of ß-catenin's structures we refer the reader to Huber and Weis (2001). While most variants in CTNNB1 are cancer-promoting and located near the N-terminus, studies have reported FEVR- and PFVS-linked variants. Two such examples are a frame-shift-causing five base-pair insertion and the A295G variant in probands with FEVR and PFVS, respectively [

13,

27].

2.4. NDP

NDP (Norrie Disease Protein, Norrin) is a cysteine-rich protein that serves as the ligand for the Norrin Wnt-signaling pathway. Norrin has been found to function as an angiogenic factor and as a neuroprotective growth factor [

28]. Norrin mediates angiogenesis partly through the induction of insulin-like growth factor-1 [

29]. The

NDP gene is located on Chr-X and subsequently, symptomatic probands are more often male. While associated with Norrie Disease, missense variants in NDP are also associated with diagnosed FEVR, both X-linked and sporadic [

30] .Pathologic variants in NDP have been associated with several vascular retinopathies, including Norrie disease, FEVR, persistent fetal vasculature syndrome (PFVS), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), and Coats disease [

11]. While these retinopathies are largely limited to the retinal vasculature, Norrie disease exhibits the most severe manifestations with retinal dysgenesis and is unique in its association with several additional symptoms, including intellectual disability, seizures, alterations to peripheral vascular structure, and gradual hearing loss [

11].

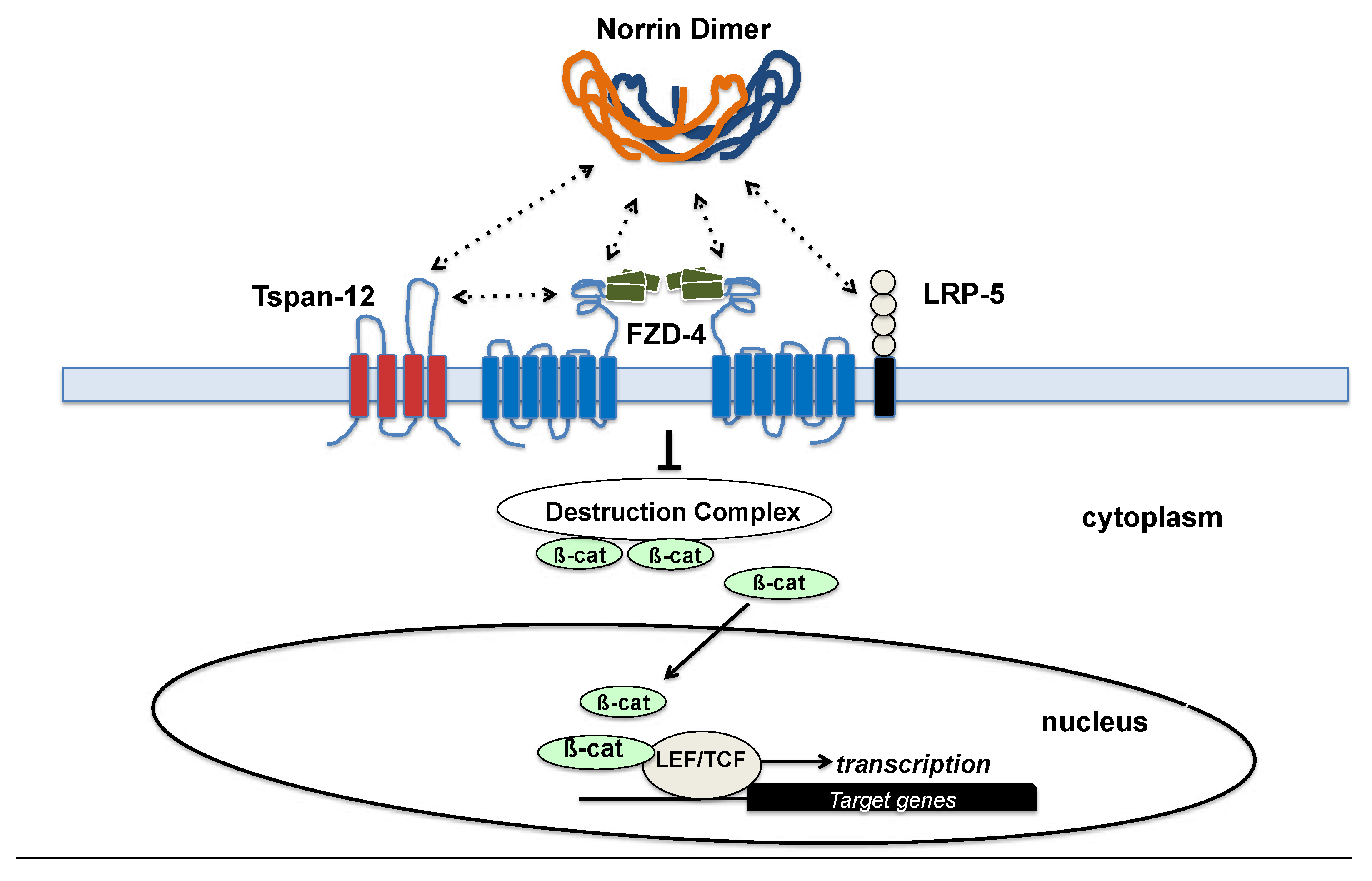

The Norrin protein is secreted by Müller cells and the Norrin homodimer binds to FZD-4, which triggers canonical Wnt-signaling that governs angiogenesis in the retina and the inner ear [

31,

32]. TSPAN-12 and LRP-5 are co-receptors that enhance this binding. See

Figure 5. Studies have identified the specific interacting regions between Norrin and FZD-4 or LRP-5 and confirmed that variants altering these structures result in decreased signaling activity via this essential pathway [

31].

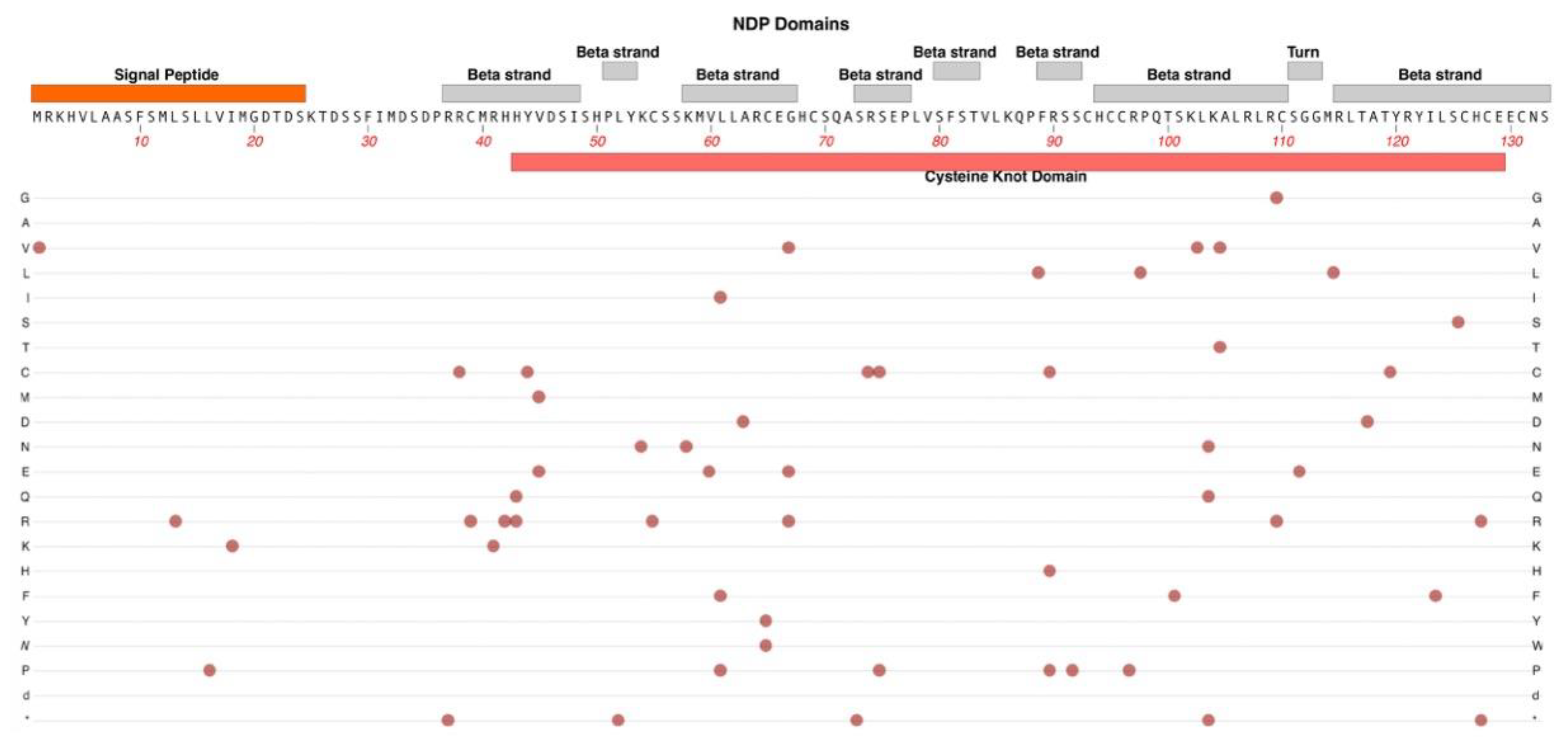

Structurally, NDP consists of two main domains: an N-terminal signal peptide which is involved in facilitating the protein’s extracellular export and a highly conserved cysteine-knot motif, which makes up the bulk of the protein. See

Figure 6.

Protein variants that alter the cysteine-knot confirmation are associated with more detrimental outcomes involving dysplasia or dysgenesis of the retina (i.e. Norrie disease) while variants that are located outside the motif are more commonly seen in patients with FEVR, in which the retina is present, albeit incompletely vascularized [

33]. FEVR-associated genetic changes include R121Q, which has been identified by multiple studies across ethnically diverse populations, and S57X and K104Q, which have been present in cases of both FEVR and Norrie disease [

34]. This highlights the interconnectedness of the mechanisms that underlie these two conditions.

This signaling pathway is specific to the retinal endothelial cell by virtue of the unique combination available of all four members of the ligand/receptor complex in the retinal endothelial cell: Norrin, FZD4, LRP5 and TSPAN12. Genetic loss of function experiments in mice indicate that while there is some overlap of Norrin and Wnt7a/Wnt7b signaling systems in the retina and brain, Norrin is more important for the iBRB and Wnt7a/7b has the larger role in development of the Blood-Brain-Barrier [

35]. Subsequently, changes to the structure of any of these four proteins have been linked to similar retinal vascular pathology, such as FEVR or ROP [

36]. Interestingly, while FEVR’s presentation can differ greatly across individuals, studies in mice have indicated that loss of function in Norrin, FZD-4, or LRP5 can often result in similar clinical phenotypes [

36]. Ohlmann et al., demonstrated that ectopic expression of Norrin restored normal retinal angiogenesis that is lost in

Ndp knockout mice [

37].

Because of Norrin’s central role in the development of the iBRB and its involvement in the pathogenesis of various retinopathies, recent research has been centered on Norrin’s capacity to combat the effects of VEGF-induced capillary leakage. Using a diabetic retinopathy mouse model, these studies indicate that exogenous Norrin can help to restore the retinal endothelial cell junctions via the canonical Norrin Wnt-signaling pathway [

38]. Our research group has demonstrated that a single intra-vitreal injection of Norrin protein can accelerate vascular regrowth and reduce inner-retina neuronal cell loss in the mouse oxygen-induced retinopathy model [

6,

39].

2.5. FZD4

As has been highlighted in this paper, the Wnt-signaling pathway is responsible for the maintenance of the blood-retina-barrier in the eye as well as for governing the process of retinal angiogenesis in the developing retina. The

FZD4 gene on Chr-11 encodes Frizzled Class-4 Receptor, a member of the Frizzled gene family which are also 7-transmembrane domain proteins. FZD-4 is the central cognate receptor for binding Norrin and is required for retinal angiogenesis and formation of the iBRB [

40,

41]. Norrin’s binds to FZD-4 and co-receptors LRP5 and TSPAN12, and subsequently, changes to the structure of any of these four proteins can cause retinal vascular pathology, such as FEVR or ROP [

36]. Interestingly, while FEVR’s presentation can differ greatly across individuals, studies in mice have indicated that loss of function in Norrin, FZD-4, or LRP5 can often result in similar clinical phenotypes [

36].

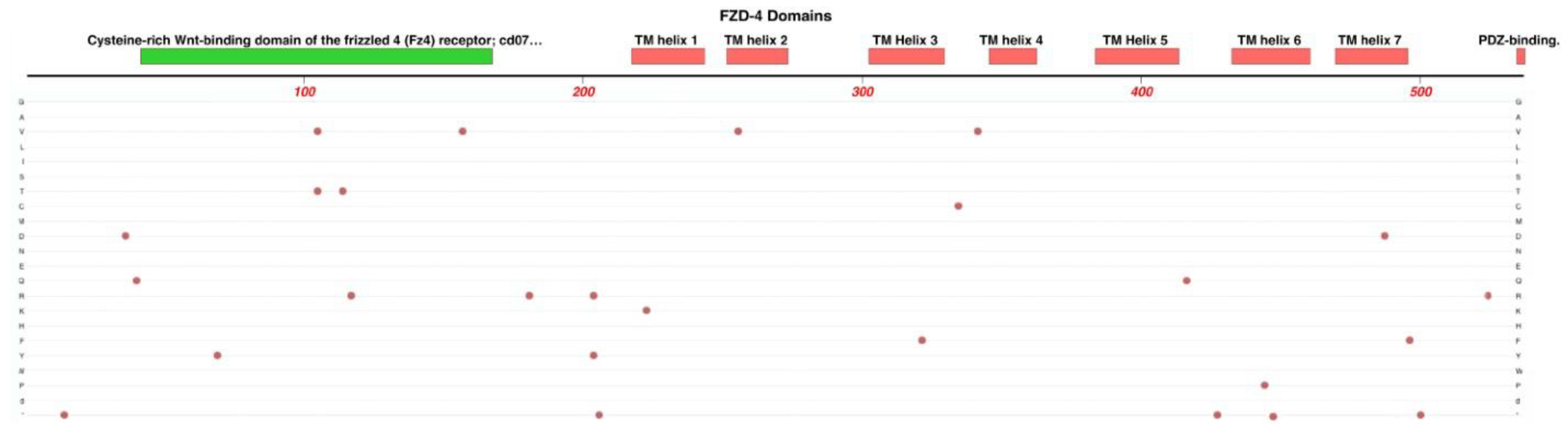

FZD4 is located on chromosome-11 and the protein it encodes is made up of 7 helix domains, a PDZ-binding domain, and a cysteine-rich binding domain located near the N-terminus that is presented extracellularly and serves as the NDP binding site. See

Figure 7. NDP is not known to bind to any other members of the Frizzled family of receptors, which highlights the specificity of the NDP/FZD-4 ligand/receptor relationship [

36].

Some examples of single missense variations of

FZD4 that are linked to FEVR include M105V, R417Q and G488D [

42]. A sequencing survey of subjects with FEVR, Norrie Disease, PRVS, Coats Disease and ROP found a strong statistical association of a double variant, p.[P33S(;)P168S], with ROP itself and a moderate statistical association with infant birth weight [

43]. The locations of 25 pathogenic and likely-pathogenic variants are shown in

Figure 7. We expect that the sequencing of new FEVR subjects will continue to reveal novel pathogenic variants. One such recent example was reported by our group recently, Cys450Ter, a nonsense that generates an early termination codon within TM helix-6. This was predicted to result in the loss of TM helix-7 and the C-terminal PDZ-binding domain of the FZD4 protein [

44].

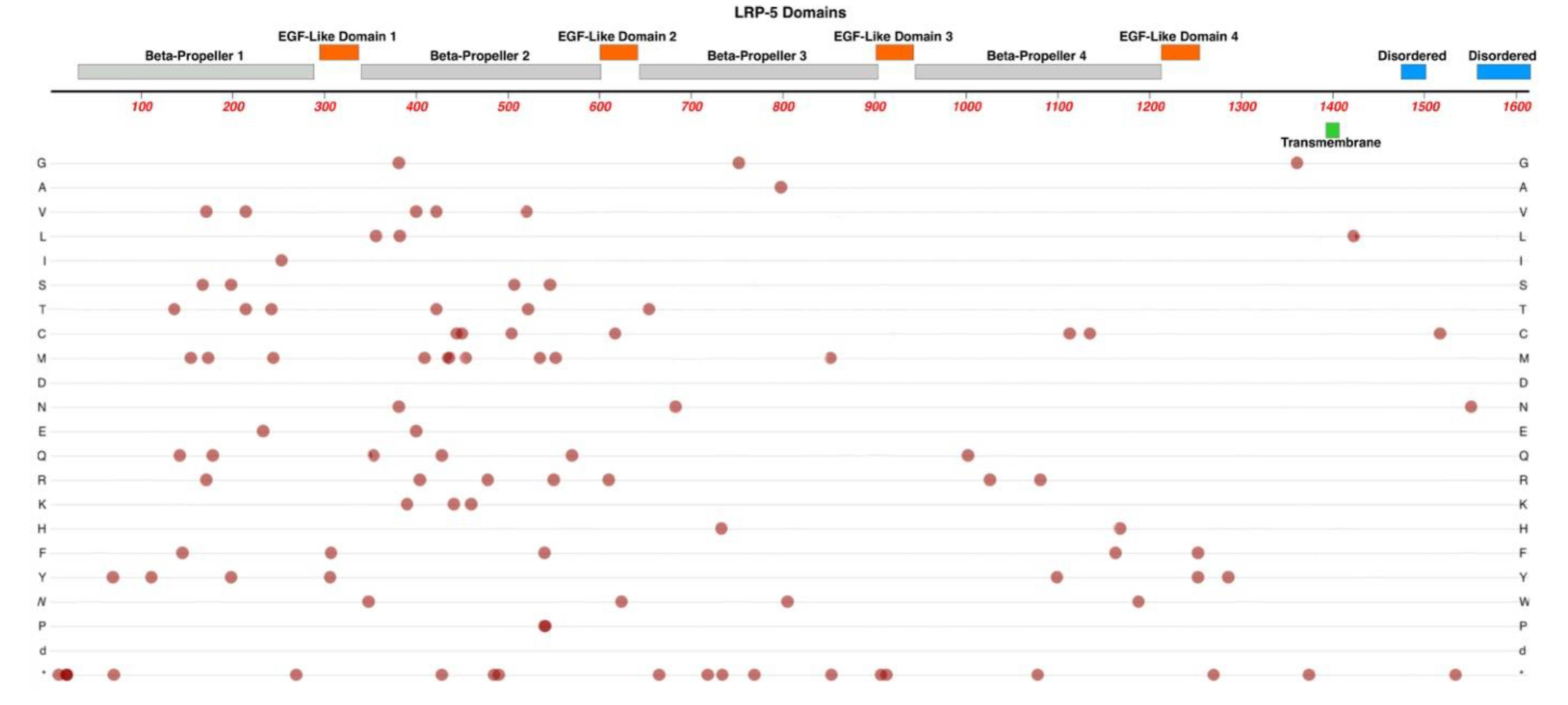

2.6. LRP5

The LDL-Receptor-Related Protein-5 is encoded by the

LRP5 gene on Chr-11 and is expressed in retinal endothelial cells. We refer the reader to He et al., for a more detailed review regarding the LRP-5 and LRP-6 receptors [

45]. As noted above, in conjunction with TSPAN-12, LRP-5 acts as a co-receptor that enhances Norrin’s binding affinity for FZD4. LRP5 is required for vascular development in the deep plexus of the neural retina [

46,

47]. LRP-5 protein has four extracellular Beta-Propeller / EGF-Like domain regions, one transmembrane domain region, and two intracellular disordered domains at the C-terminus. See

Figure 8.

LRP-5 has direct interactions with Norrin, using positively and negatively charged amino-acid sidechains. (See

Figure 5). The Beta-Propellor domains -1 and -2 nearer the extracellular N-terminus, interact with the edge of the Norrin dimer, away from where FZD4 interacts with the central surface of the Norrin dimer. A ternary complex is formed once LRP-5 and FZD-4 are bound to Norrin [

31].

In addition to FEVR, pathologic mutations in LRP-5 are also associated with familial osteoporosis and high bone density syndromes [

48]. Studies have identified several mutations in

LRP5 associated with FEVR. They include L145F, R444C, A522T, T798A, and N1121D [

49]. Qin et al., noted that these five missense mutations fall within the highly conserved beta-propeller domains of the LRP-5 protein [

49].

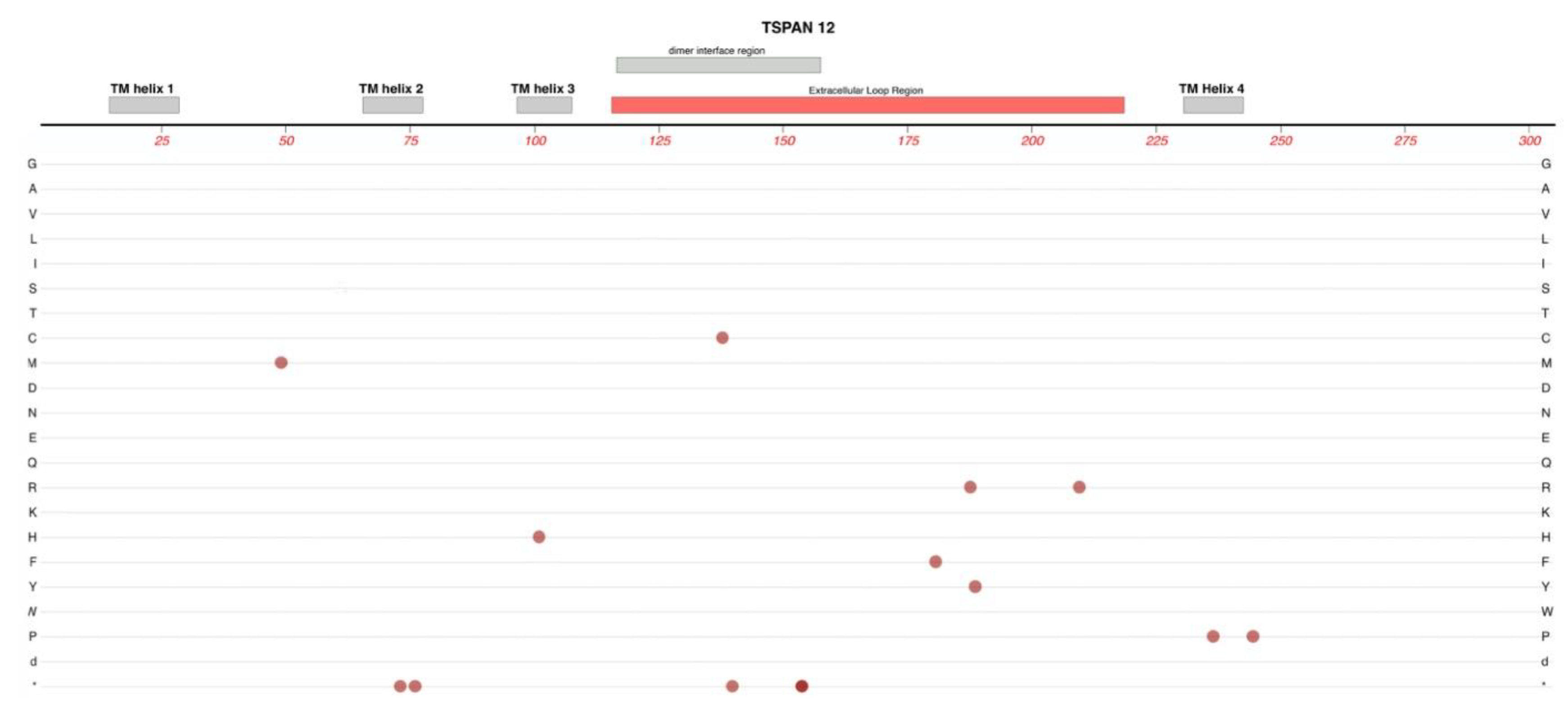

2.7. TSPAN-12

TSPAN-12 is a member of the tetra-spannin protein family, which are characterized by four transmembrane domains with both their C-terminus and N-terminus being in the cytoplasm. These 4-transmembrane domains are linked by one small extracellular loop, one small intracellular loop, and one large extracellular loop. Interactions with other proteins and the variable roles of different tetra-spannin proteins are strongly impacted by amino acid sequence differences in the large extracellular loop [

50]. See

Figure 9.

TSPAN12 variants can cause autosomal dominant FEVR [

51]. Variants of human TSPAN-12 have also been linked with ROP, specific types of cancer via regulation of progression, viral infections using TSPAN-12, and mental retardation [

52,

53,

54]. Many variants identified in probands diagnosed with FEVR are predicted to result in a truncated protein, though studies were unable to perceive a difference in clinical presentation between patients with shortened proteins and those with missense mutations [

51]. A237P is a variant observed in at least five families with FEVR [

55].

Elegant work by Junge et al., used transgenic and knockout combinations in mice to demonstrate that normal vascularization of the neural retina required a full combination of Fzd-4, Lrp-5, and Tspan-12, as well as Norrin [

56] Loss of one allele of

Tspan-12 or

Lrp5 caused minimal reduction in vertical sprouts in the neural retina. Losing one allele each of

Tspan-12 and

Lrp5 had a much greater effect on this reduction. Complete lack of the Tspan12 protein in homozygous knockouts resulted in the failure to form vertical sprouts from the superficial plexus of the developing retinal vasculature. Furthermore, in cell-based transfection assays, TSPAN-12's ability to enhance Norrin/beta-catenin signaling relied on the co-transfection of both FZD4, LRP5.

Additional studies with Tspan-12(-/-) mice confirmed a significant increase in large retinal vessels and abnormal arterial-venous crossing along with upregulation of VE-Cadherin, which regulates iBRB integrity and EC inactivity (Zhang et al. 2018). These retinas also displayed a lack of intraretinal capillaries, and glomeruloid vessel malformations, which were like defects observed in pathogenic variants of Ndp, Fzd4, and Lrp5 (Zhang et al. 2018). Mural cells were also reduced or absent in some areas of the retinas of Tspan-12(-/-) mice. Additional features included microaneurysms, impaired hyaloid vessel regression, focal hemorrhages, retinal glial cell activation, and upregulation of plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein (PLVAP). The later effect was presumably due to impairment of Norrin signaling, as Norrin-Wnt signaling is one factor thought to suppress PLVAP expression in retinal endothelial cells, which is essential to generate its high-barrier nature.

3. Conclusions

We can draw several conclusions from this brief review regarding the mechanisms underlying FEVR.

As we survey the protein domain maps that we have presented of currently known pathogenic and likely-pathogenic variants; we can conclude that almost any functional subdomain of these proteins can be involved. This is not surprising as studies of these proteins have established important protein-interaction functions or structural functions that are essential for their normal biological activity. Generally, there are little if any non-essential regions in the seven proteins reviewed.

FEVR can involve the disruption of any one of several different functions in endothelial cells, not just those related directly to the Norrin Wnt-signaling pathway. This is established by disease-causing variants in ZNF408 and KIF11. However, what all these genes and their protein products have in common is that they are particularly important for critical retinal endothelial cell activity. These include growth, proliferation, and migration of endothelial cells during formation of the retinal vasculature and maturation of a high-barrier endothelium. It is possible, and expected, that we may continue to discover novel FEVR-linked genes and good candidates would be any gene that is particularly enriched in retinal endothelial cells versus other endothelial cells, and genes with the potential to impact EC proliferation or the maturation of their high-barrier character.

The multiple allele knockout studies by Junge et al., (2009) in mice suggested the possibility that more severe FEVR-like phenotypes could result from combinations of two or more different alleles that have a minimal impact alone [

56]. Our group recently surveyed a cohort of FEVR patients and immediate relatives to confirm that the incidence of protein-altering variants in two or three different FEVR-linked genes was substantially greater than in the general population [

12]. Thus, it is possible that combined mild-alleles might result in more severe phenotypes, but we have not yet described clear examples of this in FEVR. To explore such possibilities for this relatively rare condition it will be helpful to apply genetic testing methods that survey as many genes as possible and to form global research collaborations to investigate genotypes and phenotypes from varied populations.

Rare inherited retinal vascular diseases such as FEVR, Norrie disease, and Persistent Fetal Vascular Syndrome have historically been difficult to study due to their scarcity in the population, their complex presentations, and subsequently, their challenging diagnosis. Moreover, these conditions are sometimes multigenic and it is possible that the severity of phenotypes may be impacted by combinations of two or more protein-altering variants that may have no phenotype, or a mild phenotype, on their own. Clear evidence of such multigenic contributions is yet to be described and deserves the attention of future investigations. While this highlights the challenges of genetic testing for patients with rare retinal pathology, it is imperative that efforts continue to elucidate the mechanisms that govern these conditions.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, K.K. and V.L..; writing—original draft preparation, V.L, K.M., G.A., C.P., V.J., and R.R. .; review and editing, V.L, K.M., W.D., and K.D. .; visualization, K.M. and G.A..; supervision, K.M.: funding acquisition, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

Authors who worked on this review were supported in part by the Pediatric Retinal Research Foundation, Michigan, USA and the Carls Foundation, Michigan, USA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. Topic review only.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”.

References

- Fruttiger, M. Development of the mouse retinal vasculature: angiogenesis versus vasculogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis. Sci. 2002, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Zuercher, J.; Fritzsche, M.; Feil, S.; Mohn, L.; Berger, W. Norrin stimulates cell proliferation in the superficial retinal vascular plexus and is pivotal for the recruitment of mural cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 2619–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, S.; Kumar, T.; Fruttiger, M. Retinal vasculature development in health and disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 63, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokunaga, C.C.; Mitton, K.P.; Dailey, W.; Massoll, C.; Roumayah, K.; Guzman, E.; Tarabishy, N.; Cheng, M.; Drenser, K.A. Effects of Anti-VEGF Treatment on the Recovery of the Developing Retina Following Oxygen-Induced Retinopathy. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dailey, W.A.; Drenser, K.A.; Wong, S.C.; Cheng, M.; Vercellone, J.; Roumayah, K.K.; Feeney, E.V.; Deshpande, M.; Guzman, A.E.; Trese, M.; et al. Ocular coherence tomography image data of the retinal laminar structure in a mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Data Brief 2017, 15, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dailey, W.A.; Drenser, K.A.; Wong, S.C.; Cheng, M.; Vercellone, J.; Roumayah, K.K.; Feeney, E.V.; Deshpande, M.; Guzman, A.E.; Trese, M.; et al. Norrin treatment improves ganglion cell survival in an oxygen-induced retinopathy model of retinal ischemia. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 164, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresta, C.G.; Fidilio, A.; Caruso, G.; Caraci, F.; Giblin, F.J.; Leggio, G.M.; Salomone, S.; Drago, F.; Bucolo, C. A New Human Blood–Retinal Barrier Model Based on Endothelial Cells, Pericytes, and Astrocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenney, J.R.; Soppet, D. Sequence and expression of caveolin, a protein component of caveolae plasma membrane domains phosphorylated on tyrosine in Rous sarcoma virus-transformed fibroblasts. . 1992, 89, 10517–10521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, T.W.; Antonetti, D.A.; Barber, A.J.; Lanoue, K.F.; Levison, S.W.; Penn, T.; Retina, S.; Group, R. Diabetic Retinopathy: More Than Meets the Eye; 2002; Vol. 47.

- Feng, Y.; Venema, V.J.; Venema, R.C.; Tsai, N.; Caldwell, R.B. VEGF Induces Nuclear Translocation of Flk-1/KDR, Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase, and Caveolin-1 in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 256, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruggs, B.A.; Reding, M.Q.; Schimmenti, L.A. NDP-Related Retinopathies. GeneReviews® 2022.

- Cicerone, A.P.; Dailey, W.; Sun, M.; Santos, A.; Jeong, D.; Jones, L.; Koustas, K.; Drekh, M.; Schmitz, K.; Haque, N.; et al. A Survey of Multigenic Protein-Altering Variant Frequency in Familial Exudative Vitreo-Retinopathy (FEVR) Patients by Targeted Sequencing of Seven FEVR-Linked Genes. Genes 2022, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M.W.; Stem, M.S.; Schuette, J.L.; Keegan, C.E.; Besirli, C.G. CTNNB1 mutation associated with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) phenotype. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016, 37, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-K.; Fei, P.; Li, Y.; Huang, Q.-J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Rao, Y.-Q.; Li, J.; Zhao, P. Identification of novel KIF11 mutations in patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and a phenotypic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, R.W.J.; Nikopoulos, K.; Dona, M.; Gilissen, C.; Hoischen, A.; Boonstra, F.N.; Poulter, J.A.; Kondo, H.; Berger, W.; Toomes, C.; et al. ZNF408 is mutated in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and is crucial for the development of zebrafish retinal vasculature. 2013, 110, 9856–9861. [CrossRef]

- Kashlna, A.S.; Baskin, R.J.; Cole, D.G.; Wedaman, K.P.; Saxton, W.M.; Scholey, J.M. A bipolar kinesin. Nature 1996, 379, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Jones, G.; Ostergaard, P.; Moore, A.T.; Connell, F.C.; Williams, D.; Quarrell, O.; Brady, A.F.; Spier, I.; Hazan, F.; Moldovan, O.; et al. Microcephaly with or without chorioretinopathy, lymphoedema, or mental retardation (MCLMR): review of phenotype associated with KIF11 mutations. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 22, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaa, G.M.; Enyedi, L.; Parsons, G.; Collins, S.; Medne, L.; Adams, C.; Ward, T.; Davitt, B.; Bicknese, A.; Zackai, E.; et al. Congenital microcephaly and chorioretinopathy due to de novo heterozygousKIF11mutations: Five novel mutations and review of the literature. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2014, 164, 2879–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Smallwood, P.M.; Williams, J.; Nathans, J. A mouse model for kinesin family member 11 (Kif11)-associated familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020, 29, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Zazzo, E.; De Rosa, C.; Abbondanza, C.; Moncharmont, B. PRDM Proteins: Molecular Mechanisms in Signal Transduction and Transcriptional Regulation. Biology 2013, 2, 107–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassandri, M.; Smirnov, A.; Novelli, F.; Pitolli, C.; Agostini, M.; Malewicz, M.; Melino, G.; Raschellà, G. Zinc-finger proteins in health and disease. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17071–17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Fernandez, A.; Perez-Carro, R.; Corton, M.; Lopez-Molina, M.I.; Campello, L.; Garanto, A.; Fernandez-Sanchez, L.; Duijkers, L.; Lopez-Martinez, M.A.; Riveiro-Alvarez, R.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals ZNF408 as a new gene associated with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa with vitreal alterations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 4037–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjosukarso, D.W.; van Gestel, S.H.C.; Qu, J.; Kouwenhoven, E.N.; Duijkers, L.; Garanto, A.; Zhou, H.; Collin, R.W.J. An FEVR-associated mutation in ZNF408 alters the expression of genes involved in the development of vasculature. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 3519–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Kimelman, D. Mechanistic insights from structural studies of β-catenin and its binding partners. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 3337–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.H.; Weis, W.I. The Structure of the β-Catenin/E-Cadherin Complex and the Molecular Basis of Diverse Ligand Recognition by β-Catenin. Cell 2001, 105, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Kimelman, D. Mechanistic insights from structural studies of β-catenin and its binding partners. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 3337–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.L.; Soriano, C.S.; Williams, S.; Dzulova, D.; Ashworth, J.; Hall, G.; Gale, T.; Lloyd, I.C.; Inglehearn, C.F.; Toomes, C.; et al. Bi-allelic mutation of CTNNB1 causes a severe form of syndromic microphthalmia, persistent foetal vasculature and vitreoretinal dysplasia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlmann, A.; Tamm, E.R. Norrin: Molecular and functional properties of an angiogenic and neuroprotective growth factor. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2012, 31, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeilbeck, L.F.; Müller, B.B.; Leopold, S.A.; Senturk, B.; Langmann, T.; Tamm, E.R.; Ohlmann, A. Norrin mediates angiogenic properties via the induction of insulin-like growth factor-1. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 145, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastry, B.S.; Hejtmancik, J.F.; Trese, M.T. Identification of Novel Missense Mutations in the Norrie Disease Gene Associated with One X-Linked and Four Sporadic Cases of Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy. Hum Mutat 1997, 9, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Harikumar, K.G.; Erice, C.; Chen, C.; Gu, X.; Wang, L.; Parker, N.; Cheng, Z.; Xu, W.; Williams, B.O.; et al. Structure and function of Norrin in assembly and activation of a Frizzled 4–Lrp5/6 complex. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 2305–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Dabdoub, A.; Smallwood, P.M.; Williams, J.; Woods, C.; Kelley, M.W.; Jiang, L.; Tasman, W.; Zhang, K.; et al. Vascular Development in the Retina and Inner Ear: Control by Norrin and Frizzled-4, a High-Affinity Ligand-Receptor Pair. Cell 2004, 116, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-C.; Drenser, K.; Trese, M.; Capone, A.; Dailey, W. Retinal Phenotype–Genotype Correlation of Pediatric Patients Expressing Mutations in the Norrie Disease Gene. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2007, 125, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Tong, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Peng, M. Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy-Related Disease-Causing Genes and Norrin/β-Catenin Signal Pathway: Structure, Function, and Mutation Spectrums. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 2019, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cho, C.; Williams, J.; Smallwood, P.M.; Zhang, C.; Junge, H.J.; Nathans, J. Interplay of the Norrin and Wnt7a/Wnt7b signaling systems in blood–brain barrier and blood–retina barrier development and maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, E11827–E11836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Nathans, J. The Norrin/Frizzled4 signaling pathway in retinal vascular development and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2010, 16, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlmann, A.; Scholz, M.; Goldwich, A.; Chauhan, B.K.; Hudl, K.; Ohlmann, A.V.; Zrenner, E.; Berger, W.; Cvekl, A.; Seeliger, M.W.; et al. Ectopic Norrin Induces Growth of Ocular Capillaries and Restores Normal Retinal Angiogenesis in Norrie Disease Mutant Mice. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Coránguez, M.; Lin, C.-M.; Liebner, S.; Antonetti, D.A. Norrin restores blood-retinal barrier properties after vascular endothelial growth factor–induced permeability. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 4647–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, C.C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Dailey, W.; Cheng, M.; Drenser, K.A. Retinal Vascular Rescue of Oxygen-Induced Retinopathy in Mice by Norrin. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, I.; Kim, H.R.; Beaven, A.H.; Kim, J.; Ko, S.-B.; Lee, G.R.; Kan, W.; Lee, H.; Im, W.; Seok, C.; et al. Biophysical and functional characterization of Norrin signaling through Frizzled4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 8787–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, K.T.; Wang, E.; Henze, K.; Vogel, P.; Read, R.; Suwanichkul, A.; Kirkpatrick, L.L.; Potter, D.; Newhouse, M.M.; Rice, D.S. Frizzled 4 Is Required for Retinal Angiogenesis and Maintenance of the Blood-Retina Barrier. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 6452–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, H.; Hayashi, H.; Oshima, K.; Tahira, T.; Hayashi, K. Frizzled 4 gene (FZD4) mutations in patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy with variable expressivity. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 1291–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailey, W.A.; Gryc, W.; Garg, P.G.; Drenser, K.A. Frizzled-4 Variations Associated with Retinopathy and Intrauterine Growth Retardation. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1917–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicerone, A.P.; Dailey, W.; Sun, M.; Santos, A.; Jeong, D.; Jones, L.; Koustas, K.; Drekh, M.; Schmitz, K.; Haque, N.; et al. A Survey of Multigenic Protein-Altering Variant Frequency in Familial Exudative Vitreo-Retinopathy (FEVR) Patients by Targeted Sequencing of Seven FEVR-Linked Genes. Genes 2022, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Semenov, M.; Tamai, K.; Zeng, X. , LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: arrows point the way. Development 2004, 131, 1663–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.-H.; Yablonka-Reuveni, Z.; Gong, X. LRP5 Is Required for Vascular Development in Deeper Layers of the Retina. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e11676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Li, Q.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M.; Hokama, M.; Sardi, S.H.; Nagao, M.; Warman, M.L.; Olsen, B.R. Critical Endothelial Regulation by LRP5 during Retinal Vascular Development. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0152833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Semenov, M.; Tamai, K.; Zeng, X. , LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: arrows point the way. Development 2004, 131, 1663–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Hayashi, H.; Oshima, K.; Tahira, T.; Hayashi, K.; Kondo, H. Complexity of the genotype-phenotype correlation in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy with mutations in theLRP5and/orFZD4genes. Hum. Mutat. 2005, 26, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seigneuret, M.; Delaguillaumie, A.; Lagaudrière-Gesbert, C.; Conjeaud, H. Structure of the Tetraspanin Main Extracellular Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 40055–40064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulter, J.A.; Ali, M.; Gilmour, D.F.; Rice, A.; Kondo, H.; Hayashi, K.; Mackey, D.A.; Kearns, L.S.; Ruddle, J.B.; Craig, J.E.; et al. Mutations in TSPAN12 Cause Autosomal-Dominant Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 86, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lai, M.B.; Pedler, M.G.; Johnson, V.; Adams, R.H.; Petrash, J.M.; Chen, Z.; Junge, H.J. Endothelial Cell–Specific Inactivation of TSPAN12 (Tetraspanin 12) Reveals Pathological Consequences of Barrier Defects in an Otherwise Intact Vasculature. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 2691–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charrin, S.; Jouannet, S.; Boucheix, C.; Rubinstein, E. Tetraspanins at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 3641–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusoff, A.A.M.; Khair, S.Z.N.M.; Ismail, A.S.; Embong, Z. Detection of FZD4, LRP5 and TSPAN12 genes variants in Malay premature babies with retinopathy of prematurity. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2019, 14, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikopoulos, K.; Gilissen, C.; Hoischen, A.; van Nouhuys, C.E.; Boonstra, F.N.; Blokland, E.A.; Arts, P.; Wieskamp, N.; Strom, T.M.; Ayuso, C.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing of a 40 Mb Linkage Interval Reveals TSPAN12 Mutations in Patients with Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 86, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junge, H.J.; Yang, S.; Burton, J.B.; Paes, K.; Shu, X.; French, D.M.; Costa, M.; Rice, D.S.; Ye, W. TSPAN12 Regulates Retinal Vascular Development by Promoting Norrin- but Not Wnt-Induced FZD4/β-Catenin Signaling. Cell 2009, 139, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Lai, M.B.; Pedler, M.G.; Johnson, V.; Adams, R.H.; Petrash, J.M.; Chen, Z.; Junge, H.J. Endothelial Cell–Specific Inactivation of TSPAN12 (Tetraspanin 12) Reveals Pathological Consequences of Barrier Defects in an Otherwise Intact Vasculature. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 2691–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).