Submitted:

18 September 2023

Posted:

19 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

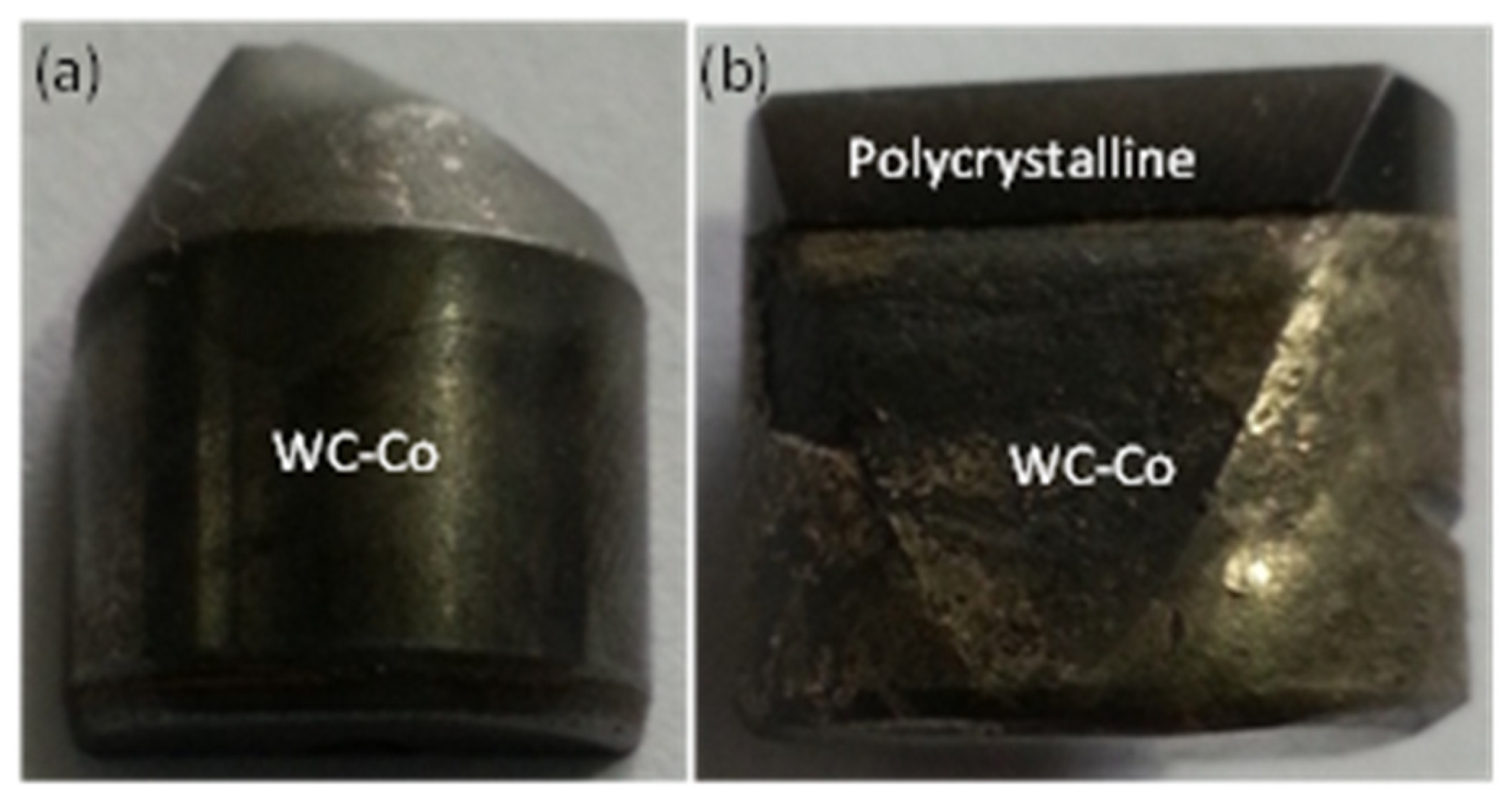

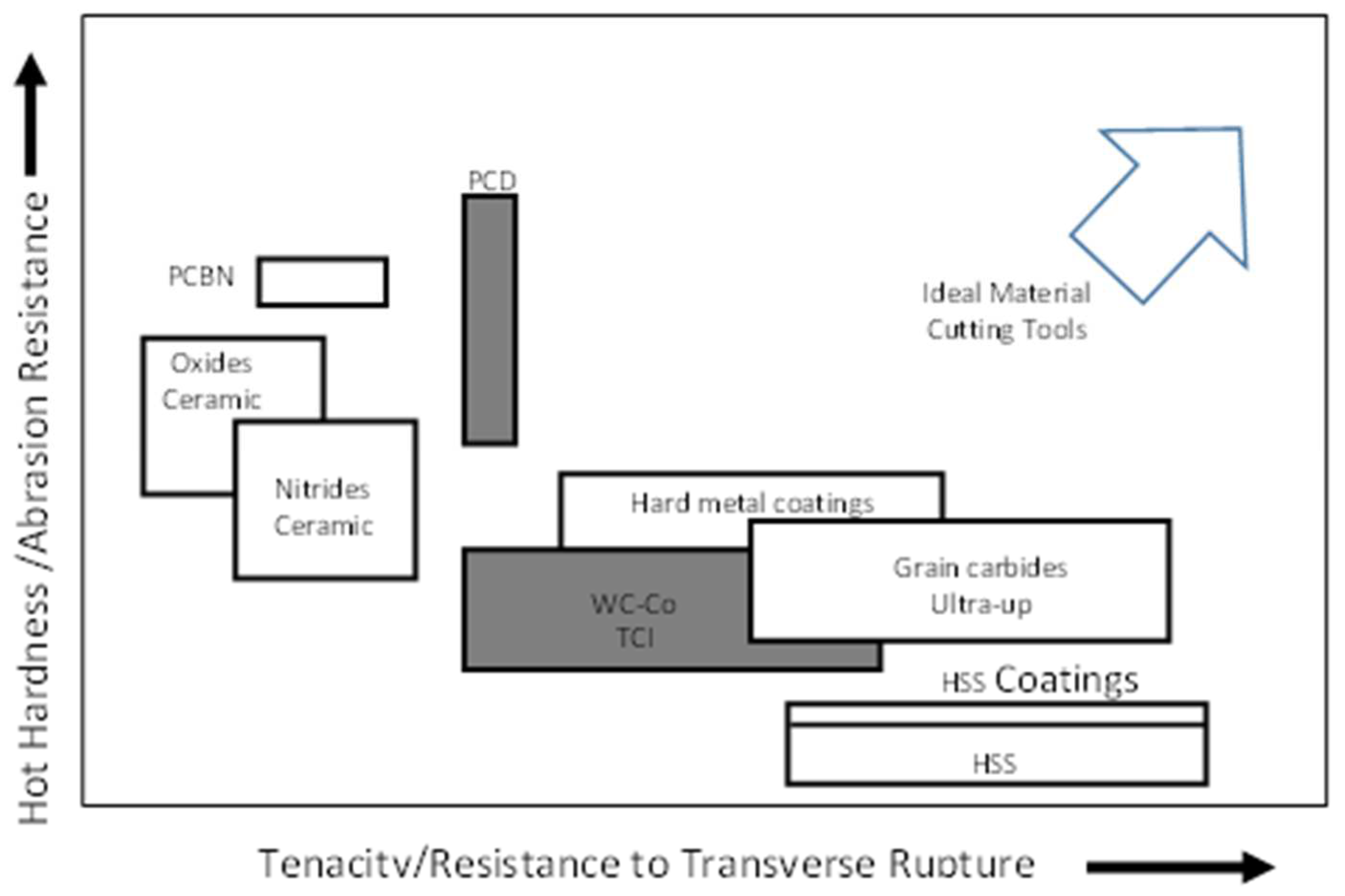

2. Selection of Cutting Materials

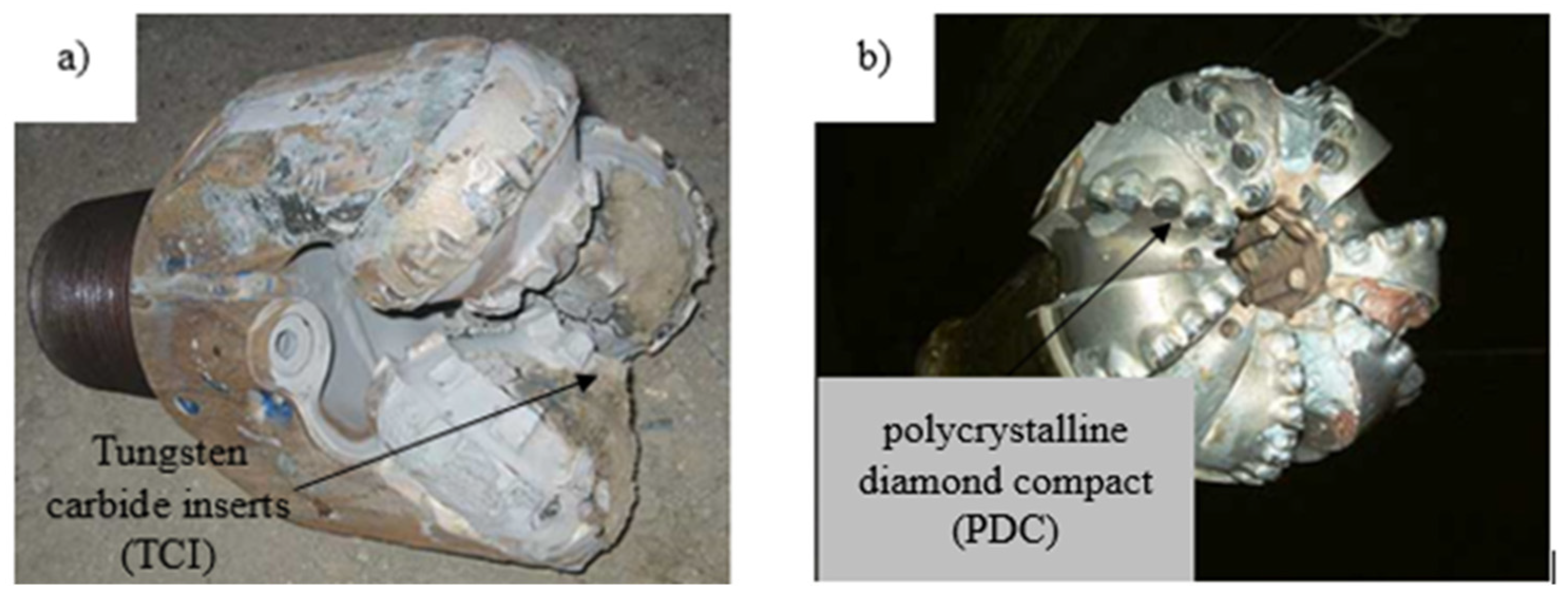

Triconic Bits with TCI

PDC cutters

3. Materials and Methods

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

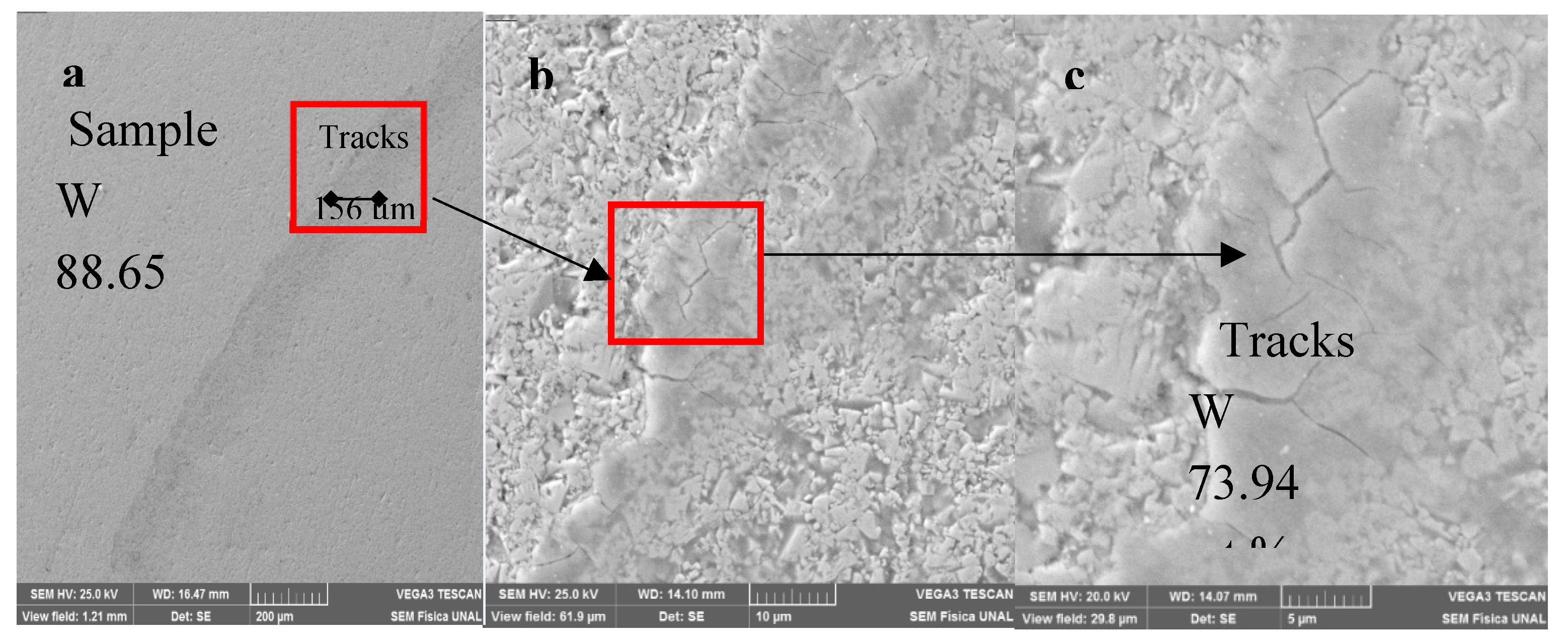

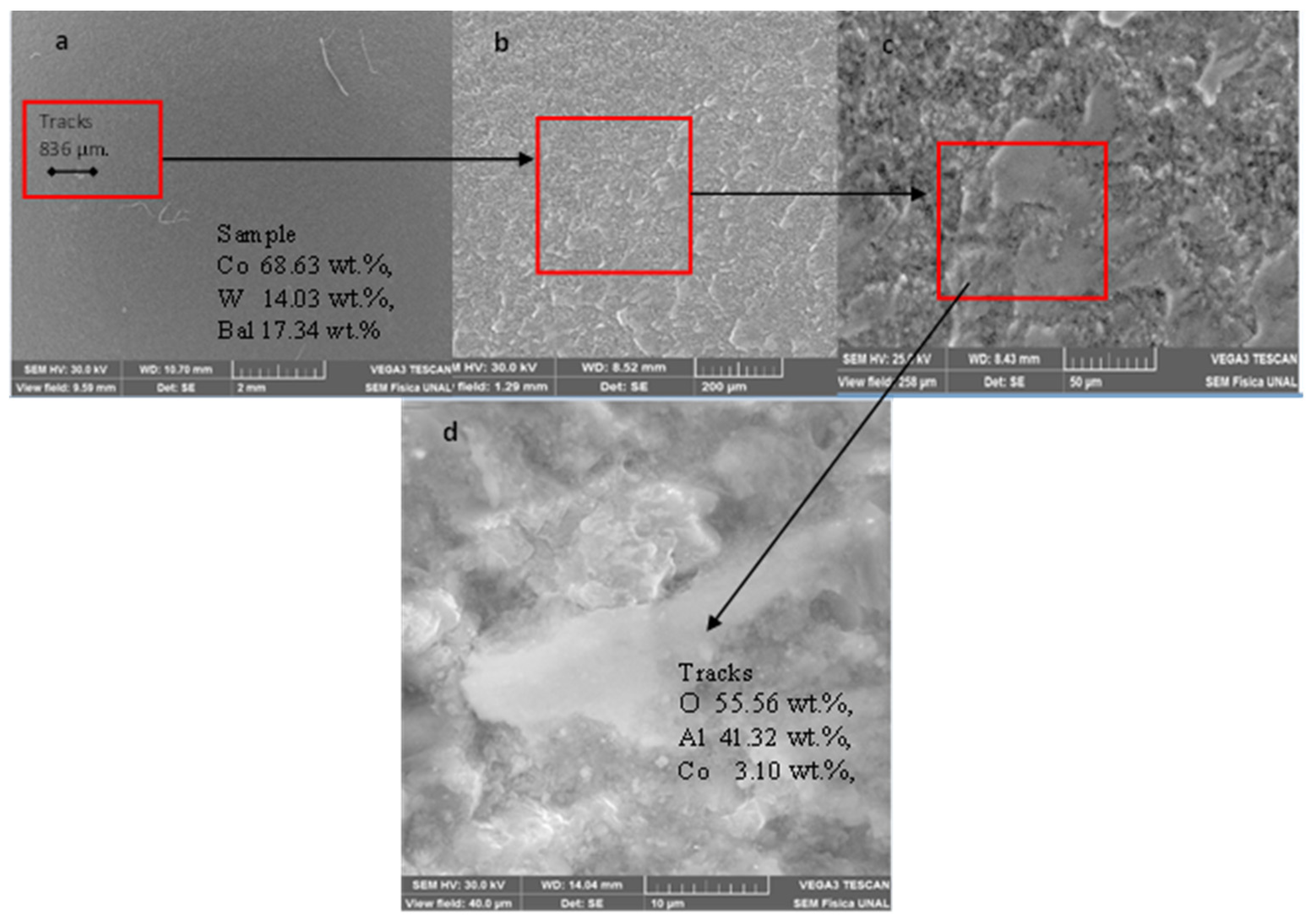

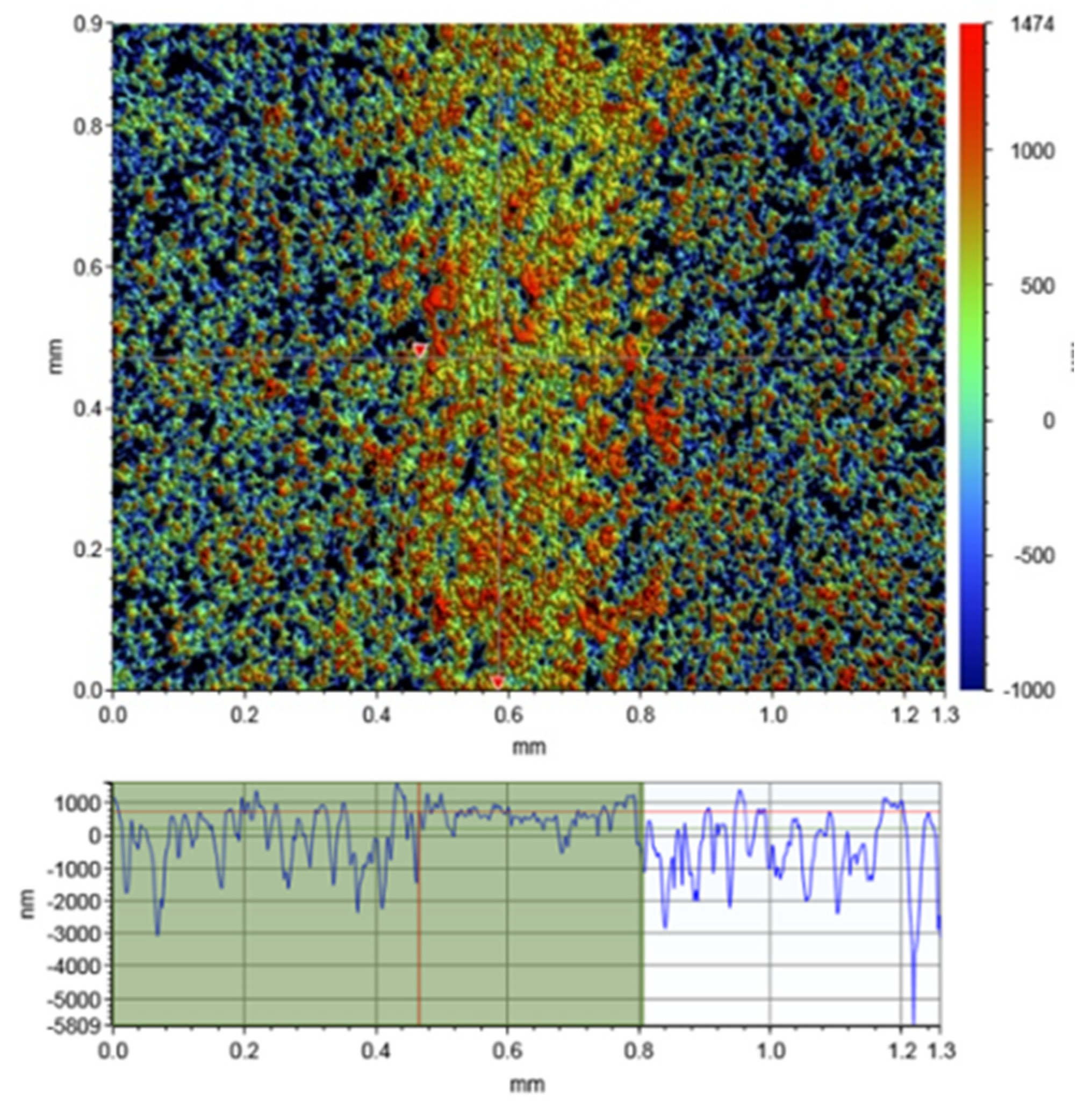

4.1. Hardness and Wear Test

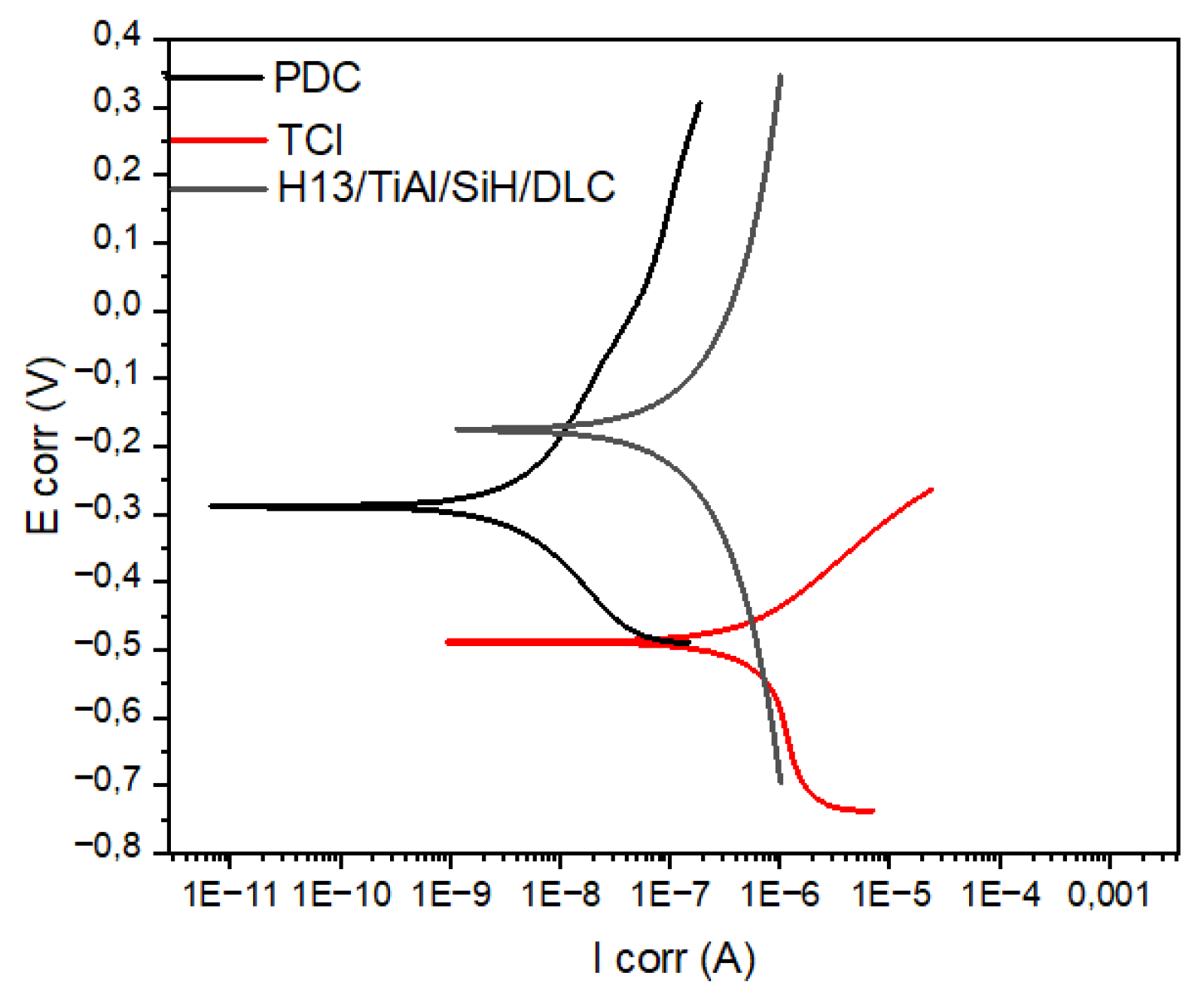

4.2. Electrochemical Test

4.3. Selection material drill bits

4. Conclusions

- The PCD uncertainties have a higher hardness than the TCI ones, this result is to be expected since the PCDs are composed with incrusted diamonds, however the hardness depends on the amount of Co binder present.

- From the wear test, the results of the coefficient of friction of the TCI are high, knowing that its application is as a cutting element; therefore, it implies a higher energy consumption for its work.

- The wear mechanisms of the uncertainties were different. In the TCI, cracks appeared due to the oxidation of the samples. The formation of cracks due to the distribution of friction results in the uneven distribution of high local temperatures and a large temperature gradient of the material. On the other hand, the PCD cutters exhibited a soft wear, this type of failure is less important than other mechanisms present in the PCD inserts, mainly due to the fact that the hardness of the indenter in the test had a lower hardness than the uncertain.

- Finally, the TCI insert exhibited lower corrosion resistance due to the exchange of electrons with the electrolyte through the cobalt present in the material. Although each insert has a specific application for well drilling, PCD cutters can be applied in more aggressive environments due to their corrosion and wear behavior, but they cost at least five times that of inserts. TCI. Therefore, it is necessary to look for a material with similar characteristics and that is more affordable; One option would be DLC coatings, as the results of the corrosion test showed good corrosion properties.

5. Acknowledgments

References

- Kanyanta, V.; Dormer, A.; Murphy, N.; Invankovic, A. Impact Fatigue Fracture of Polycrystalline Diamond Compact (PDC) Cutters and the Effect of Microstructure. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2014, 46, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centala, P.; Challa, V.; Durairajan, B.; Meehan, R.; Páez, L.; Partin, U.; Segal, S.; Wu, S.; Garrett, I.; Teggart, B.; Tetley, N. El Diseño de Las Barrenas: Desde Arriba Hasta Abajo. Oilf. Rev. Spanish 2003, 23, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Human, A.M.; Exner, H.E. Electrochemical Behaviour of Tungsten-Carbide Hardmetals. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1996, 209, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacny, K. Fracture and Fatigue of Polycrystalline-Diamond Compacts. SPE Drill. Complet. 2012, 27, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, S.G.; Bohn, K.P.; Goedickemeier, M. Core Drilling in Reinforced Concrete Using Polycrystalline Diamond (PCD) Cutters: Wear and Fracture Mechanisms. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2009, 27, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.P.; Cooper, G.A.; Hood, M. Fatigue Test on Polycrystalline Diamond Compacts. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1993, 163, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, C.H.; Meany, N.; Hughes, C. The Development of a Fracture-Resistant PDC Cutting Element. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, 25–28 September 1994; pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Griffo, A.; White, B.; Belnap, D.; Hamilton, R.; Portwood, G.; Cox, P.; Hilmas, G.; Bitler, J. Chipping Resistant Polycrystalline Diamond and Carbide Composite Materials for Roller Cone Bits. Proc. - SPE Annu. Tech. Conf. Exhib 2001, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.Z.; Griffo, A.; White, B.; Lockwood, G.; Belnap, D.; Hilmas, G.; Bitler, J. Fracture Resistant Super Hard Materials and Hardmetals Composite with Functionally Designed Microstructure. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2001, 19, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamsowlat, I.; Evans, B.; Kwon, H.J. A Review of the Frictional Contact in Rock Cutting with a PDC Bit. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, R.K. A Review on the Wear of Oil Drill Bits (Conventional and the State of the Art Approaches for Wear Reduction and Quantification). Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 90, 554–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Lv, T.; Chen, H.; Ma, T.; Fang, Z.; Shi, J. Flow Accelerated Corrosion of X65 Steel Gradual Contraction Pipe in High CO2 Partial Pressure Environments. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalibon, E.L.; Pecina, J.N.; Cabo, A.; Trava-Airoldi, V.J.; Brühl, S.P. Fretting Wear Resistance of DLC Hard Coatings Deposited on Nitrided Martensitic Stainless Steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Evans, A.G.; Cooper, C. V Wear Mechanism Operating in W-DLC Coatings in Contact with Machined Steel Surfaces. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2004, 179, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Saito, T.; Tanaka, A. Tribological Properties of DLC Films against Different Steels. Wear 2013, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 16. Papakonstantinou, P.; Zhao, J.F.; Richardot, A.; McAdams, E.T.; McLaughlin, J.A. Evaluation of Corrosion Performance of Ultra-Thin Si-DLC Overcoats with Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2002, 11, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F. Materials Selection in Mechanical Design; ELSEVIER, Ed.; Fourth.; Burlington, 2013; Vol. 53; ISBN 9788578110796.

- Field, J.E.; Pickles, C.S.J. Strength, Fracture and Friction Properties of Diamond. Diam. Relat. Mater. 1996, 5, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussmann, R.S. Applications of Diamond Synthesized by Chemical Vapor Deposition. In Handbook of Ceramic Hard Materials; Riedel, R., Ed.; 2008; pp. 573–622.

- Islam, M.R.; Hossain, M.E. State-of-the-Art of Drilling. In Drilling Engineering; 2021; pp. 17–178 ISBN 9780128201930.

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Jing, S.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Li, G.; Ren, H. Experimental Study of WC-Co Cemented Carbide Air Impact Rotary Drill Teeth Based on Failure Analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2014, 36, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembaiyan, K.T.; Keshavan, K. Combating Severe Fluid Erosion and Corrosion of Drill Bits Using Thermal Spray Coatings. Wear 1995, 186–187, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, M.; Gerbaud, L.; Paris, J.Y.; Denape, J.; Dourfaye, a. A Study on PDC Drill Bits Quality. Wear 2013, 298–299, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincapie, W.S.; Olaya, J.J.; Alfonso, J.E. Propiedades Tribológicas de Recubrimientos de CrxOy Depositados Mediante Proyección Térmica Sobre Latón. Ing. MECÁNICA Tecnol. Y Desarro. 2015, 5, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hincapie-campos, W.S.; Jairo, J.; Alfonso-orjuela, J.E. Caracterización Microestructural, Mecánica y de Desgaste de Recubrimientos de Cux Aly Depositados Mediante Proyección Térmica. DYNA 2017, 84, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtanowicz, A.K.; Kuru, E. Mathematical Modeling of Pdc Bit Drilling Process Based on a Single-Cutter Mechanics. J. Energy Resour. Technol. Trans. ASME 1993, 115, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.M.; Nie, X.; Yu, S. Study on Failure Mechanisms of DLC Coated Ti6Al4V and CoCr under Cyclic High Combined Contact Stress. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 688, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bi, Q.; Leyland, A.; Matthews, A. An Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Study of the Corrosion Behaviour of PVD Coated Steels in 0. 5 N NaCl Aqueous Solution: Part I. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bi, Q.; Leyland, A.; Matthews, A. An Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Study of the Corrosion Behaviour of PVD Coated Steels in 0. 5 N NaCl Aqueous Solution: Part II. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y. Metals and Hard Materials Material Properties and Tool Performance of PCD Reinforced WC Matrix Composites for Hardbanding Applications. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2015, 51, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrisy, A.; Perry, T.; Cheng, Y.T.; Alpas, A.T. Wear of Thermal Spray Deposited Low Carbon Steel Coatings on Aluminum Alloys. Wear 2001, 251, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.G.; Perrott, C.M. Wear Processes Exhibited by WC-Co Rotary Cutters in Mining. Wear 1974, 29, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, L.; Torres, Y.; Anglada, M. On the Fatigue Crack Growth Behavior of WC-Co Cemented Carbides: Kinetics Description, Microstructural Effects and Fatigue Sensitivity. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 2381–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, M.G.; Gant, A.; Roebuck, B. Wear Mechanisms in Abrasion and Erosion of WC/Co and Related Hardmetals. Wear 2007, 263, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyashin, I.; Ries, B. Wear Damage of Cemented Carbides with Different Combinations of WC Mean Grain Size and Co Content. Part I: ASTM Wear Tests. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2014, 46, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-P.; Hood, M.; Cooper, G.A.; Li, X. Wear and Failure Mechanisms of Polycystalline Diamond Compact Bits. Wear 1992, 156, 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- W. S. Hincapie C, J. M. Gutiérrez B, V. J. Trava-airoldi, J. J. Olaya F, J. E. Alfonso, G. Capote Influence of the Ti x Si and Ti x Si / a-Si : H Interlayers on Adherence of Diamond- like Carbon Coatings. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 109. [CrossRef]

- Kellner, F.J.J.; Hildebrand, H.; Virtanen, S. Effect of WC Grain Size on the Corrosion Behavior of WC-Co Based Hardmetals in Alkaline Solutions. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2009, 27, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SAMPLE | HARDNESS (GPa) |

|---|---|

| TCI | 12,93 ± 0,41 |

| PDC | 39,93 ± 2,30 |

| SAMPLE | VOLUME (mm3) | WEAR RATE Q (mm3/N mm) |

COEFFICIENT OF FRICTION |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCI | 0,002±0.01 | 1,0955±0.07 X 10-8 | 0,31996836±0,0595 |

| PDC | 0,392±0.02 | 2,043±0.10 X 10-6 | 0,4036155± 0,1618 |

| Sample | Ecorr (mV) | Icorr (mA/cm2) |

|---|---|---|

| TCI | -487.2 | 1.32 X 10-6 |

| PDC | -287.8 | 3.75 X 10-9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).