4. Results and Discussion

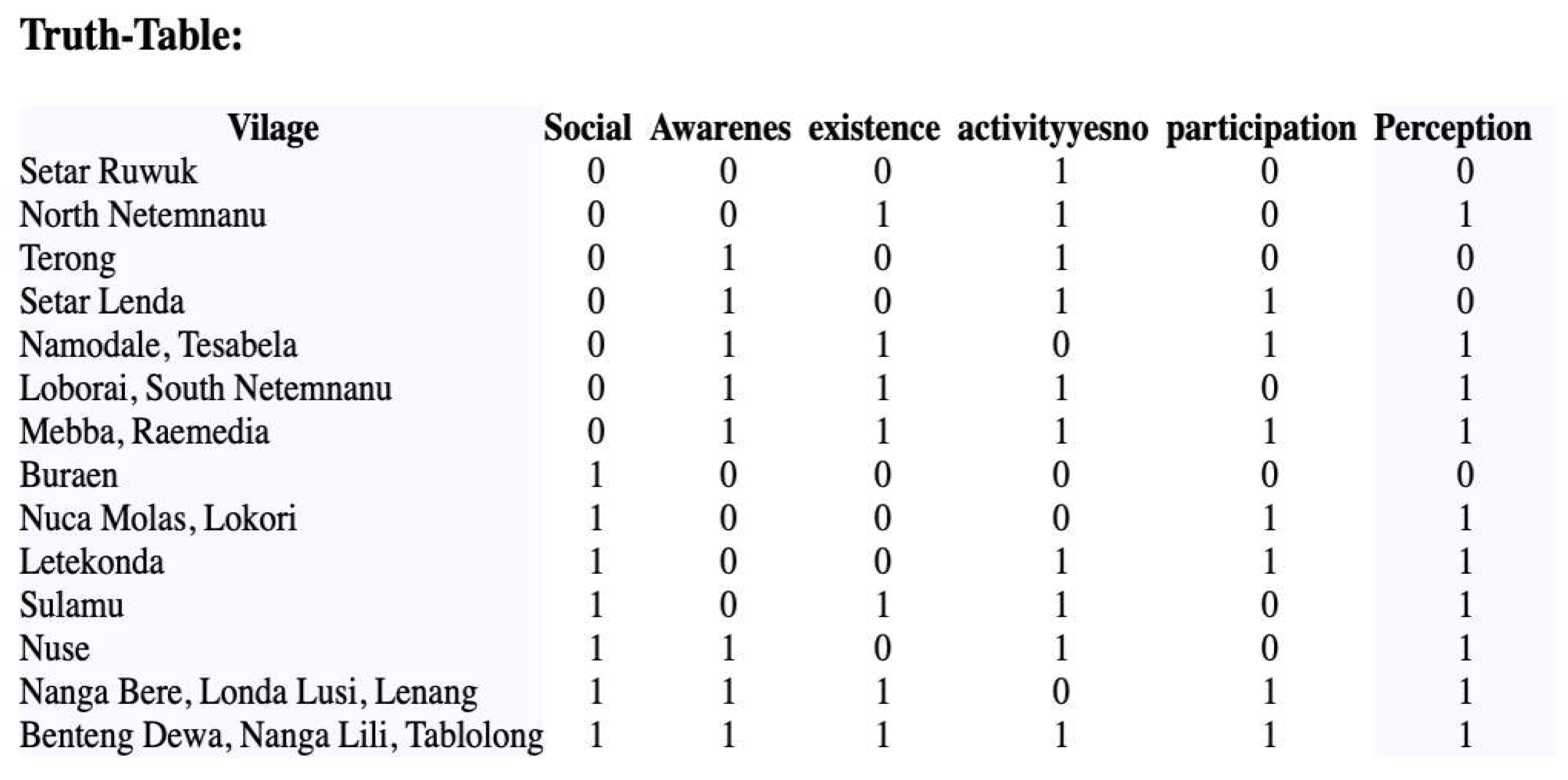

Table 2 displays the results of the Truth Table generated using Tosmana Software. In total, there are 14 different pathways identified among the 22 coastal villages. Eight of these villages, namely Setar Ruwuk, Netemmanu Utara, Terong, Setar Lenda, Buraen, Letekonda, Sulamu, and Ndaonuse, have their own unique pathway. Each of these villages has a distinct combination of conditions that influences their perception of the conservation area.

Among these pathways, Setar Ruwuk, Terong, Setar Lenda, and Buraen are coastal villages that have a perception outcome of zero, indicating a very low belief in the benefits of the conservation area for mitigating environmental risks. Out of the 14 pathways, ten of them show conditions that lead to a positive outcome (Perception = 1), indicating a stronger perception of the conservation area's benefits.

The pathway demonstrating the presence of all conditions (Social = 1, Awarenes = 1, existence = 1, activity = 1, and participation = 1) and a positive outcome (perception = 1) is observed in three coastal villages: Benteng Dewa, Nanga Lili, and Tablolong. Similarly, Nanga Bere, Londa Lusi, and Lenang also exhibit a positive outcome, except for the absence of the activity condition (activity = 0). Loborai and Nemnanu Selatan show a positive perception of marine conservation, indicated by the presence of the awareness, existence, and activity conditions (awareness = 1, existence = 1, and activity = 1). Mebba and Raemedia demonstrate that the presence of awareness, existence, and activity is sufficient to generate a positive outcome in perception. On the other hand, Nuca Molas and Lokori require the presence of social economic status (social = 1) and participation in multi-stakeholder institutions to achieve a positive perception.

Each coastal village with a positive outcome has a unique pathway. For example, Ndaonuse requires the presence of social condition, awareness, and activity for a positive outcome, while Sulamu necessitates the presence of social status, existence, and activity for a positive perception.

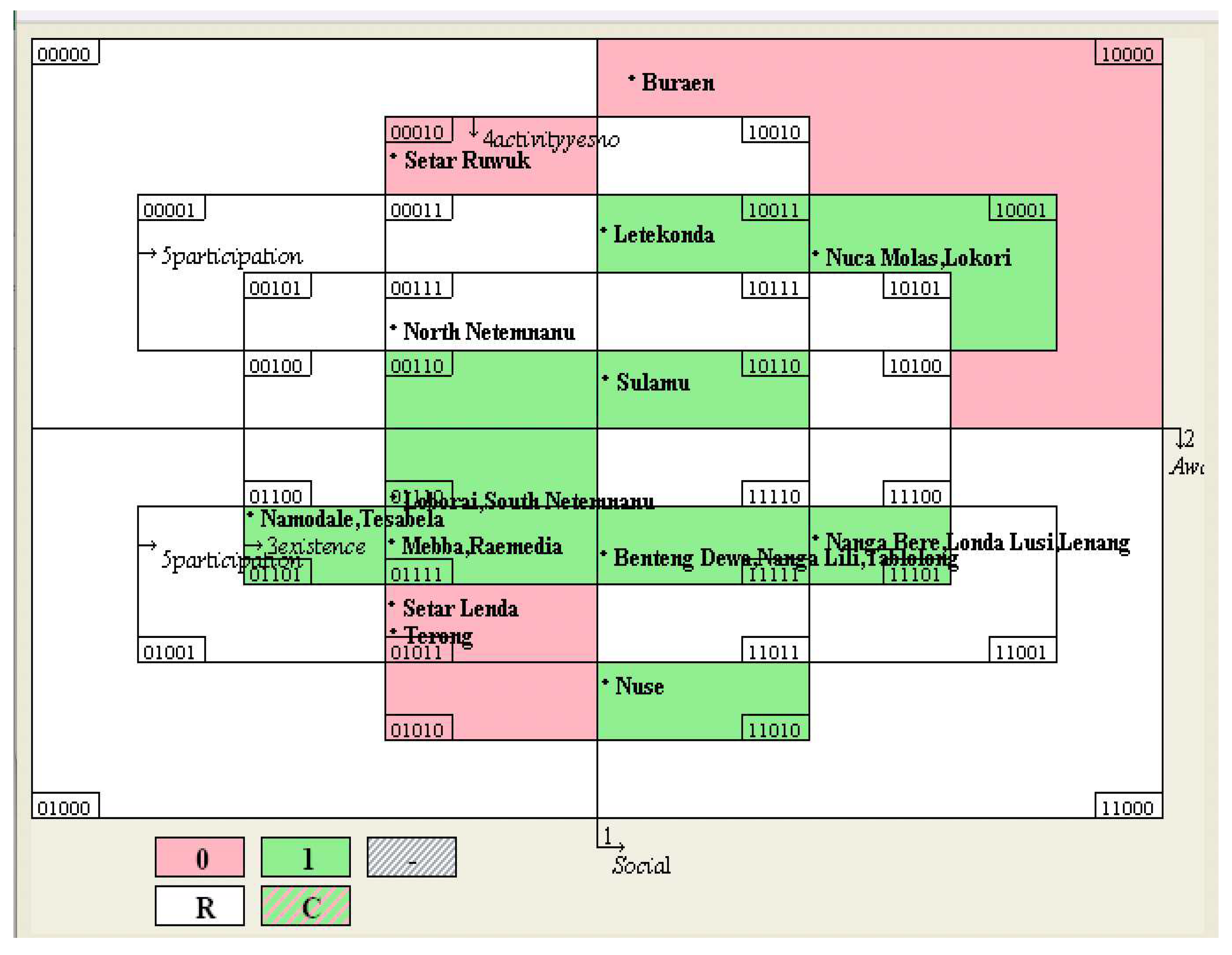

Figure 2 depicts a Venn diagram illustrating the combination of conditions and outcomes, as well as the coastal villages that align with the truth table analysis. In the diagram, each box is divided into two areas: zero and one. The horizontal axis represents the social condition, with zero (low social status) on the left side of the box and one (social = 1) on the right side. The vertical axis represents the awareness condition, with zero in the upper part and one in the lower part. The other four boxes can be interpreted in a similar manner, with each box displaying a combination of five digits representing the presence (1) or absence (0) of the five conditions.

The green-colored areas indicate an outcome of one (perception = 1). For instance, Letekonda exhibits a strong perception of Savu conservation supported by the presence of social status, activity, and participation, while the other two conditions are absent (indicated by the digit combination 10011). All other green areas represent combinations of causal conditions as outlined in the truth table analysis. The pink-colored areas indicate a zero outcome (low perception or perception = 0), while the white areas indicate a remainder (R), signifying the possibility of causal combinations among the five conditions, but these cases were not found in the study.

Benteng Dewa, Nangalili, and Tablolong have excellent and similar pathways for positive outcomes. The social conditions of the community are primarily fishermen, farmers and traders who depend on coastal and marine resources for their livelihoods. In terms of educational background, most respondents have primary school education, followed by junior high school and then senior high school. In terms of information sources, the most widely used media are radio and television. Campaigns for sustainable management of coastal and marine resources through the media in the community play an important role as an awareness effort. Awareness efforts on the importance of coastal and marine resource management in the Savu Sea have been carried out by NGOs and local governments and can be accessed through several media (print and electronic) and verbally. Community awareness of coastal and marine environmental conservation regulations is very high, which can be assessed from several factors such as: the existence of the term and definition of marine protected areas in the community, community responses to the layout of villages in marine protected areas, community responses to the types of fishing gear allowed, community perceptions of activities allowed in coastal areas, and community attitudes towards receiving sanctions.

More than 70% of the community are aware of the term and definition of marine protected areas. Not only are they aware of the existence of conservation areas, but they have also applied the activities that are allowed/not allowed in conservation areas, such as being allowed to plant seaweed and not allowed to take corals or cut mangrove wood. The community also participates or takes on the role of a Supervisory Community Group, some are actively involved in the activities of local environmental organizations in their respective areas.

The level of dependence on the environment shapes the perception of conservation inherent in their daily lifestyle. The community's perception of knowledge and attitude towards the importance of local wisdom in conservation areas is very high. The community stated that the principle of living in harmony with nature is still practiced in daily life; the coast and sea in my village are maintained by customary rules; I will feel guilty if I do not take good care of nature; I believe conservation efforts will provide natural resource reserves for the future; I believe what I do will have an impact on the surrounding nature; I believe that practices/customs/customs related to nature management can be integrated with the management of existing marine protected areas.

Letekonda is a tourist village located in Loura Subdistrict, Southwest Sumba Regency. The Letekonda community has an educational background up to senior high school. Access to information sources mostly uses radio and television. The mastery of livelihood assets shows that the coastal area of the study village has natural assets that have the potential to be developed as a source of livelihood for the surrounding community. These natural assets are in the form of coastal ecosystems and marine biota, including mangrove ecosystems, coral reefs, seagrass beds, marine biota, and beautiful coastal panoramas. All of these natural assets have been utilized by local communities, both socially (food sources and social arenas), economically (sources of economic income), and culturally (cultural attractions/local traditions).

The main livelihood of the community is fishing, and side livelihoods are salt farmers, seaweed farmers, and seafood collectors. The fishing fleet used is equipped with outboard motor engines with an average engine power of 15-24 PK with an average boat size of less than 1GT. The main fishing gear used is purse seine, which is still considered an environmentally friendly fishing gear, while hand fishing rods, squid nets, fishing nets, fish arrows, fish spears, and pincers and gouges are used in small quantities with different concentrations of usage. In addition to fishing, some Letekonda communities also engage in seaweed cultivation and salt processing. Although still very limited, these activities have become alternative livelihoods for people who previously relied solely on agriculture and self-employment (trade). This condition also has implications for the ability of the fishing community to implement dual livelihood strategies.

The limitations of fisheries development are generally influenced by several factors, including the lack of knowledge and expertise of fishermen to catch fish, limited fishing gear, and limited infrastructure to support fisheries activities (capital, production facilities, institutions, etc.). In Southwest Sumba itself, these limitations can be seen as a positive value because the fisheries that take place are still traditional, not yet intensive and massive, and carried out on a small scale, so the fisheries pressure in this region is still relatively low.

Community leadership plays an important role in the structure of coastal communities. The community's perception of the existence of the Savu Sea NMP is important in maintaining coastal and marine natural assets, so the same for community participation in preserving the coastal and marine environment is very dependent on existing community leaders. High participation is shown by the community's desire to involve themselves in various activities related to coastal programs, such as empowerment activities and meetings with agencies/small businesses/universities regarding coastal and marine resource management.

In general, the community has a very good level of enthusiasm, participation and adaptation. Enthusiasm is shown by their curiosity and motivation for the coastal and marine development plan for both capture fisheries and beach/sun tourism. One example is the community's desire to know how FADs work by finding out information by asking related agencies or searching the internet and trying to practice. For example, fishermen's interest in learning fishing techniques with FADs. Fishermen learn by themselves through the internet, or ask other parties, then try to practice fishing with FADs, even though it is fairly unsuccessful, fishermen still try to find information as much as possible to be able to improve it.

Natural capital in the form of a very rich and beautiful coast supported by social capital with various distinctive traditions and has been recognized as a tourist attraction to foreign countries presents a very high opportunity for the development of fisheries as well as community-based tourism and local natural resources. This development will be able to become an alternative economy and multiple livelihood strategies for the sustainability of the lives of coastal communities. The presence of an alternative economy (dual livelihood strategy) will be able to help communities overcome existing vulnerability issues while reducing threats through reducing destructive activities that have been carried out due to household economic needs. Communities utilize coastal and marine areas as social arenas, food sources, household income, and cultural/traditional areas. Economic utilization of coastal and marine activities have been carried out in the form of fishing and other marine biota, seaweed cultivation, salt processing, and beach tourism. Although limited, the community still applies customary traditions in the utilization of coastal and marine resources, for example the tradition of "Pili Nyale" (catching sea worms) which is carried out only once a year in February-March, precisely the day before the implementation of the Pasola tradition. The utilization of marine resources by local communities in the coastal areas of the study villages is generally not optimal due to the limited production assets and technical skills possessed by the communities. This condition causes utilization activities to be concentrated in the coastal and coral reef areas.

Sulamu. The people of Sulamu Village make their main livelihoods as fishermen, farmers and traders. Most of the community relies heavily on coastal and marine resources as fishermen and seaweed farmers. Education levels in Sulamu are low, with the average graduating only from primary school and junior high school. However, access to information sources from households that control/own communication tools in Sulamu Village in 2020 was quite high and reached more than 61% of households in Sulamu Regency. Communication tools used as sources of information include radio/tape, television, satellite dishes and mobile phones. The existence of natural disaster anticipation/mitigation facilities/efforts such as an early warning system for natural disasters/specifically Tsunami, safety equipment, as well as signs and disaster evacuation routes already exist and function well compared to the other 6 villages that do not have these disaster mitigation facilities/efforts at all in Sulamu Regency.

The existence of the Savu Sea NMP is realized by the Sulamu Village community as a marine area that needs to be preserved to ensure the sustainability of coastal and marine resources. Protection efforts that have been carried out by the Sulamu Village community are conducting waste cleanup activities on the coast as well as community-based waste management discussions. Efforts to build public awareness in terms of waste disposal behavior to the willingness to manage waste together more responsibly and provide benefits are carried out with stakeholders who observe the coastal and marine environment.

This has a positive impact on the perception of the Sulamu Village community on the importance of the existence of the Savu Sea NMP. Community perceptions are built starting from campaigns and discussions of community-based coastal and marine management. With the presence of commitment as a positive outcome towards the perception and existence of the Savu Sea NMP, this village has proclaimed itself as “Kampung Bahari Nusantara” (or maritime village of the archipelago). The existence of this Kampung Bahari Nusantara, invites various parties to come and carry out various pro-coastal and marine environmental activities that can improve the standard of living of the people in this village.

Community activities in efforts to conserve coastal and marine resources in conservation areas are active participation through several programs such as: strengthening the mentoring of tolerance attitudes towards seaweed farming community groups through the existence of seaweed, and community empowerment based on fishermen partnerships with the district government. Other supporting activities that are routinely carried out by the Sulamu community such as beach cleaning, training to improve the quality of seafood products, and other activities in order to increase community capacity in sustainable coastal and marine resource management.

NuseVillage. Nuse Island is one of Indonesia's outermost small islands located in Ndao Nuse Subdistrict, Rote Ndao Regency. Nuse Island has coral reef and fish ecosystems and white sandy beaches that can be found in almost all parts of the island. More than 93% of villagers in Nuse Island, Ndao Nuse subdistrict make a living as fishermen and depend on the sea for their livelihood. Most of the Nuse people have only completed primary school.

The southern waters of Nuse Island, around 631.41 hectares, are included in the utilization zone of the Savu Sea National Park, supporting the activities of the fishing community. The small pelagic fisheries sector is the mainstay of the community. The fishery commodity comes from small pelagic fish with the leading commodity Squid (Loligo sp.). Simple fishing gear used by fishermen is environmentally friendly fishing gear, such as fishing rods and gill nets. The fishing fleet used by Nuse fishermen is dominated by Jukung (also known as cadik is a small wooden Indonesian outrigger canoe) and outboard motor boats.

Perception is one of the factors that form an awareness in a person. The level of awareness of the Nuse community on the importance of conservation can be seen from how the Hoholok/Papadak wisdom is perceived towards the perceived object, in this case coastal and marine resources. If associated with the results of the study, the perception of conservation leads to a positive outcome.

The perception of conservation is very high because one of the local wisdoms that exists in Rote Ndao Regency and is still implemented until now is Hoholok/Papadak, which is a customary agreement/local wisdom that applies on land and at sea in an area that has natural resources that according to the owner/government can be useful for many people and steps, so it needs to be protected by customary events. The application of Hoholok/Papadak wisdom in coastal and marine areas in Rote Ndao Regency, which is first implemented on land and has an effect on resource sustainability, is deemed necessary to be adopted and applied in coastal and marine areas, especially to support the management and supervision of the Savu Sea NMP. To date, there are 3 nusak (customary areas) that are used as pilots for the application of Hoholok/Papadak in coastal and marine areas. However, the perception of the importance of protecting coastal and marine resources in the wisdom of Hoholok/Papadak and the existence of villages in the Savu Sea NMP conservation area is known to most Rote people so that the preservation of coastal and marine resources can be maintained in Nuse Village.

Nangabere, Londa Lusi, and Lenang. The communities in these three villages are mostly fishermen, farmers, and breeders. As a fishing community, they do not only earn income from catching fish, but also from obtaining fish, shellfish, shrimp, seaweed, at times when the sea is receding, or what is commonly known by the local term makameting. Community activities in utilizing coastal resources in addition to fishing, also a small portion of seaweed cultivation and salt-making business.

Public awareness of the importance of preserving the coastal and marine areas of the national marine park is shown in several coastal environmental conservation activities such as mangrove cultivation; protection of marine biota such as Olive Ridley turtles and the use of environmentally friendly fishing gear (passive, traditional fishing gear) such as Bubu often called traps and guiding barriers; these tools are often called fishing pots or fishing baskets. In order to prepare excellent fishermen as the backbone of the maritime economy, several fishermen capacity building trainings such as fishermen capacity building training in fisheries business management based on coastal ecosystem conservation have been conducted.

The existence of the Savu Sea NMP conservation area gives a special meaning to these three villages. With high awareness and always actively participating in efforts to conserve coastal and marine resources, several community-based environmental organizations such as the conservation youth association and the monitoring community group.

Participation in conservation efforts is very high in these three Villages, one example of community participation in turtle conservation activities such as the release of hatchlings released from five semi-natural nests and the Olive Ridley turtle species. People who are members of the Nanga Bere Village community group until 2021 to 2022 have released 1,800 sea turtles to the Savu Sea NMP. This activity aims to increase public awareness, especially the people of Nanga Bere Village, of the importance of preserving the environment, protecting protected biota and the function of conservation areas. Other participation took the form of mangrove plantation.

The perception of the community of Londa Lusi village in Rote Ndao Regency is influenced by the local wisdom of Hoholok/Papadak; while the perception of the community of Nangabere Village in West Manggarai Regency that conservation of coastal and marine resources is a must is expressed in a commitment that Nanga Bere Village becomes a pilot area for sea turtle conservation in mainland Flores and Indonesia; for the community of Lenang Village in Central Sumba Regency, coastal resources are a kind of economic support and at the same time to fulfill nutrition for people living in coastal areas.

Mebba dan Raemadia. The awareness of the people of Mebba Village and Raemadia Village in West Sabu Subdistrict, Sabu Raijua Regency has similarities in the perception of the existence of the Savu Sea NMP as a sustainable provider of coastal and marine resources. Making a living as fishermen, the community is very dependent on the availability of resources from coastal and marine ecosystems. In the coastal area, the community is aware of the importance of mangrove ecosystems as a habitat for existing marine biota and the importance of coastal environmental health in the pond area for salt production. In the marine area, the community realizes the importance of using environmentally friendly fishing gear.

The existence of conservation areas is an important part of local government policy as stipulated in the local regulation of Sabu Raijua Regency number 3 of 2011 concerning the regional spatial plan of Sabu Raijua Regency Year 2011-2031 which has well regulated nature conservation areas for the Savu Sea national waters conservation area; fisheries allotment areas for capture fisheries, aquaculture (including mariculture, seaweed, salt ponds) and industrial fish processing; local protection areas such as coastal border areas; as well as provisions for zoning regulations as well as the rights, obligations and roles of the community in spatial planning. The existence of this regional regulation assists sustainable coastal and marine resource management plans and supports all resource utilization activities.

The local government's focus on developing the area is also demonstrated by the government's commitment to propose the entire island of Sabu Raijua to become a national geopark area. Geoparks are the basis for geotourism development [

18]. Geoparks can encourage this area not to have high-value geological heritage and geological diversity, but including biodiversity and culture that are integrated in it, and developed with three main pillars, namely conservation, education, and local economic development [

19,

20,

21]. Thus, the development in these two villages has a clear pathway towards a conservation-based area.

In addition to the commitment of the local government, the community is also taking part in efforts to conserve and protect resources. This can be seen from the utilization activities of coastal areas such as salt ponds in Mebba Village producing quality salt according to Indonesian national standards; while resource utilization in marine areas is the activity of catching small pelagic fisheries, demersal fish and reef fish using fishing gear that is very environmentally friendly based on the Code of Conduct Responsible for Fisheries (CCRF) [

22]. These two resource utilization activities determine the high rate of community perception and participation in protecting coastal and marine resources [

23].

Community perception in the use of environmentally friendly fishing gear is very well shown by the use of gill net, troll line, casting net, purse seine, and long line. The highest scores for CCRF criteria assessment [

24] are high selectivity of fishing gear, not damaging habitats and breeding grounds for fish or other organisms, and not damaging marine biodiversity.

Community participation in both villages in maintaining the health of marine ecosystems can be seen from the high participation rate of fishermen, almost all of whom use very environmentally friendly fishing gear. In addition, the community actively participates in several conservation activities of the Savu Sea such as routine monitoring and review of management plans and zoning of the Savu Sea NMP, community capacity building activities, and active in carrying out marine monitoring functions as a community supervisory group.

Loborai and South Netemnanu. Loborai Village in Sabu Raijua Regency and South Netemnanu Village in Kupang Regency have the same perception or perspective on the existence of the Savu Sea NMP as a coastal and marine area that can provide a future for the community. The uniqueness of the resources and the existence of the two areas which are the core zone and utilization zone of the Savu Sea NMP, make these two locations have the same pathways and produce positive cluster outcomes.

The importance of the existence of the Savu Sea NMP conservation area is a shared responsibility and requires cooperation from all parties. Conservation activities such as mangrove plantation are carried out with the concept of pentahelix [

25,

26] or multi-stakeholders involving elements of government, academics, agencies or businesses, communities or communities and the media [

27]. In the case of Loborai Village, the existence of coastal and marine areas and resources cannot be separated from the attention of the local government. In the seaweed farming sector, there is a seaweed factory in this area; the tourism sector, such as the existence of Raemea Beach, which is one of the unique and amazing tourist attractions with white sand and giant golden-red cliffs; and the existence of Biu Port (the longest port dock in ENT Province) for sea transportation services between regions in ENT Province. The presence of coastal and marine resources as well as port facilities has fostered a very high public awareness of the importance of protecting and preserving the environment [

28]. This is evident from several community activities in efforts to protect coastal marine areas and resources such as participating in various opportunities such as the mangrove planting movement in Loborai Village, as well as community participation in several existing conservation programs.

Regarding South Netemnanu Village, the existence of Batek Island covering an area of 946.02 hectares as a core zone in the Savu Sea NMP area plays an important role in maintaining the boundaries between countries. Batek Island is Indonesia's frontier island bordering the Democratic Republic of Timor Leste, the beach is a green turtle nesting site, there are coral reefs, migration corridors for cetaceans, whales and dolphins. In this core zone, there is an Indonesian National Army guard post on the island. With the existence of this core zone, community awareness has increased in terms of national defense and security, and community activities are limited in this area with the core zone.

Namodale and Tesabela. Public awareness of the abundance of marine life and the good condition of coral reefs with a percentage of live coral cover of up to 80% greatly supports underwater tourism activities. This healthy water condition supports tourism activities in Tesabela Village and Namodale Village. Having beach tourism and marine tourism capital makes these two villages in the same pathway cluster with positive outcomes.

The existence of the Savu Sea NMP is of particular concern to the people of Namodale Village and Tesabela Village. There is concern from the provincial government such as launching Namodale Village as Kampung Tangguh Nusantara in 2021 as an effort to increase public awareness to maintain health protocols in the context of national economic recovery from the impact of covid-19 and various other efforts such as revitalizing inclusive tourism villages and increasing the capacity of multi-parties to support tourism.

Community participation in these two regions is very high, especially in active participation in several environmental programs in coastal and marine areas such as mangrove tree planting activities as a concern for the environment, especially in efforts to prevent coastal abrasion, as well as several monitoring activities for the use of marine resources of the Savu Sea MNP which are routine activities of the BKKPN. The perception of the community in Namodale Village and Tesabela Village on marine conservation is very high because one of the local wisdoms [

29,

30,

31] in Rote Ndao Regency that is still implemented today is Hoholok/Papadak.