1. Introduction

The constant increase of CO

2 concentration in the atmosphere and the depletion of fossil fuels raised serious worldwide environmental and energy-related concerns [

1]. Thus, one of the most actual research topics is the conversion of CO

2 into fuels by green, eco-friendly approaches and sustainable methodologies. The sun energy is a perfect engine that fits these requirements in driving the chemical conversion of CO

2 (employed as an energy vector in a carbon-based cycle), to be used as a raw starting material for fuel production [

2]. While direct artificial photosynthesis is conceptually attractive [

3], its real-world application is still not optimal, and parallel approaches are actively explored. An immediate and clean way of capturing sun power is the direct conversion into electric energy by photovoltaic cells. The possible exploitation of this energy for the electrochemical reduction of CO

2 into chemicals with higher energy content attracted several researchers, resulting in an exponential growth of the number of papers that lately appeared in this field.

The present contribution aims at illustrating the recent results of the spectroelectrochemical (SEC) technique applied to the study of CO

2 reduction. We explored the activities of Re and Mn catalysts bearing bipyridine-like (bpy) units towards the electrochemical and photochemical reduction of CO

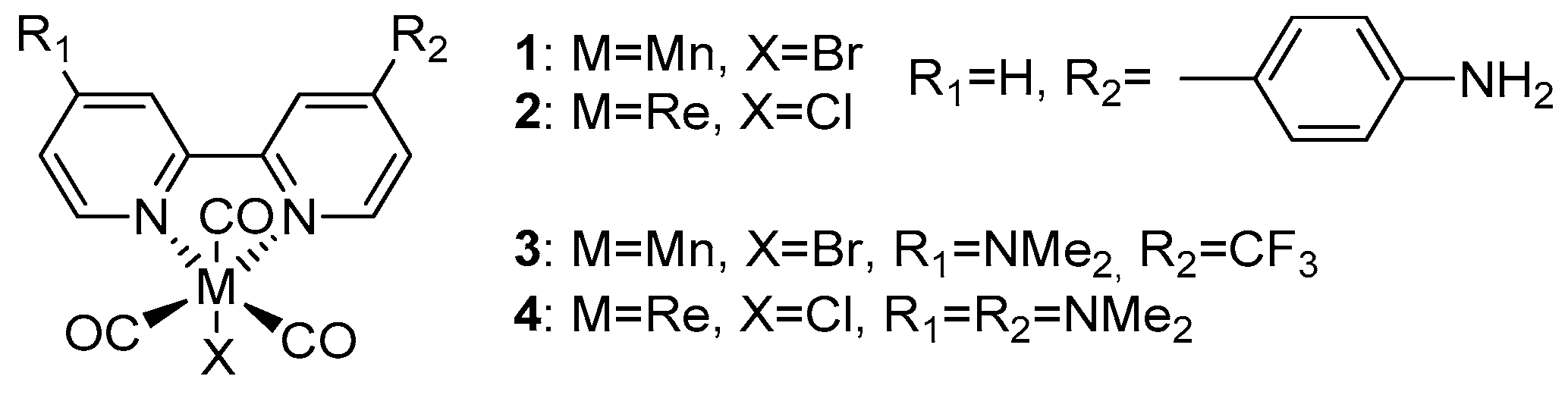

2 [1, 4]. The electrochemical behavior of complexes

1-

4 (

Scheme 1) has been reported by us [

5], but in different conditions; herein we report the SEC properties and new insights into the overall mechanism. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) of Mn-bpy derivatives usually displays two subsequent chemically irreversible reductions [

6], but only the second one, and in the presence of proton sources, is active toward the CO

2 conversion. Complex

1, when chemically bonded to the electrode surface via the 4(4-aminophenyl)-2,2’-bipyridine functionality (apbpy), shows extremely interesting catalytic properties in water, with TON (Turn Over Number) up to 164000 [4b, 4e]. On the contrary, Re-bpy complexes typically undergo a first reversible reduction followed by a second irreversible and catalytically active reduction, even in the absence of proton donors. In very rare cases (and kinetically much slower systems), Re-bpy derivatives can display catalytic activities even at the first reduction peak, in a so-called slow regime [

7]. We herein demonstrate by SEC that the Re complex

2, is catalytically active already at the first reduction. SEC experiments were employed as a powerful tool to elucidate the mechanism details of CO

2 reduction [

8] in the case of analogous Mn and Re derivatives [4f, 9]. The SEC experiments and properties of the complexes are herein studied in homogeneous phase for the first time.

Complexes 3 and 4 of the present set have been selected for the comparison, considering their promising relatively high TON values observed for the electrochemical conversion of CO

2 in homogeneous solution. Complex 3 possess a push-and-pull substituent groups on the bpy ligand, resulting into a net negligible shift of the reduction potential with respect the Mn-bpy complex without substituents, while good catalytic activities were recorded in both CVs and CPEs (Constant Potential Electrolysis) experiments. Complex 4, bearing a strong electron-donor ligand, shows a shift of the reduction processes to more negative potentials, with improvements in the catalytic activity [5b]. We selected these two different methodologies for enhancing the catalytic behavior of the catalysts and test them in SEC experiments. The four complexes, which are promising catalysts [

5] (see

Table 1), were studied in comparative tests under SEC conditions.

2. Results

2.1. Mn(apbpy)(CO)3Br

CV of Mn(apbpy)(CO)

3Br (

1) in dry acetonitrile (MeCN) displays two chemically irreversible reductions at E

p=-1.21 V and E

p=-1.41 V

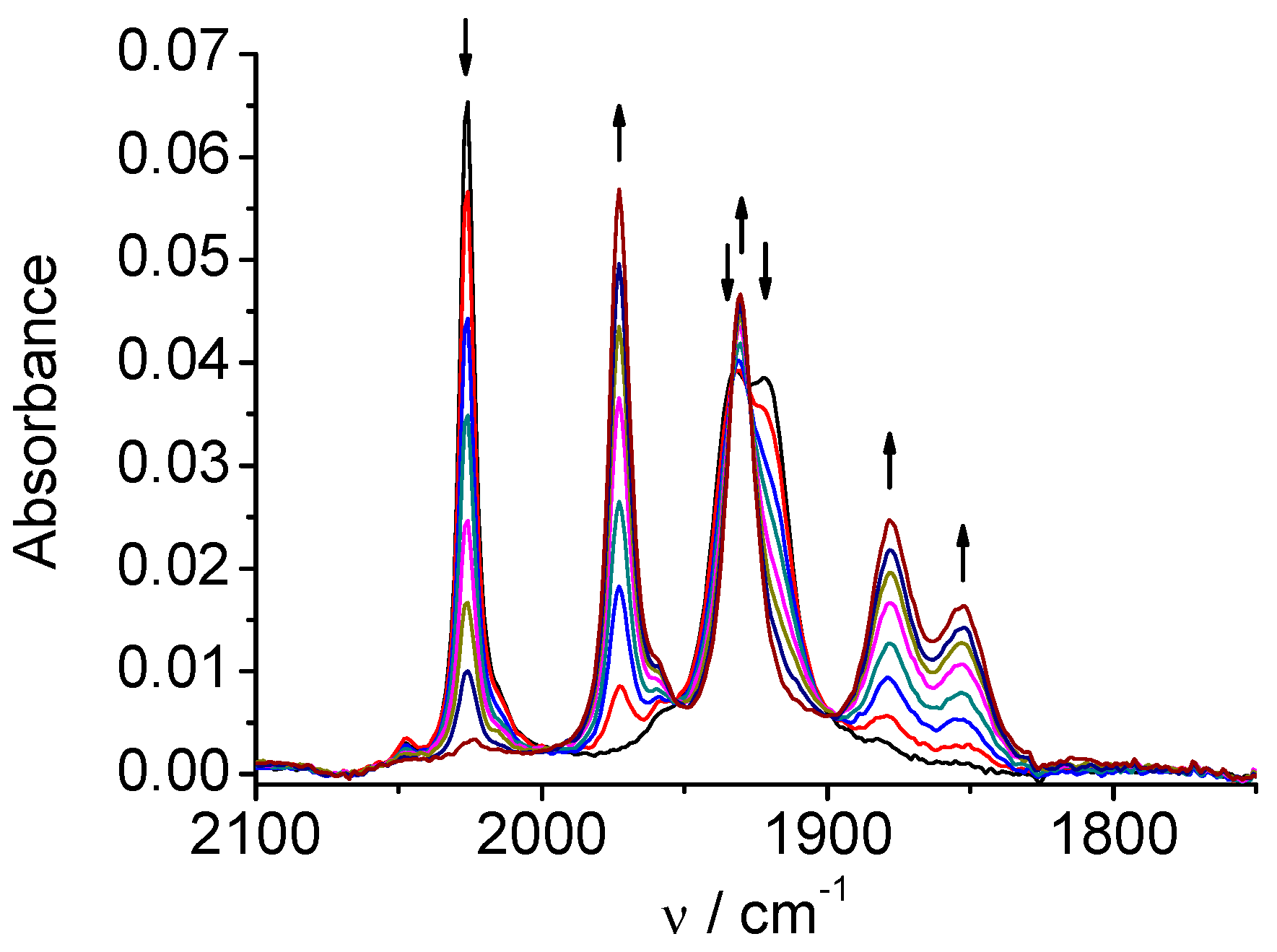

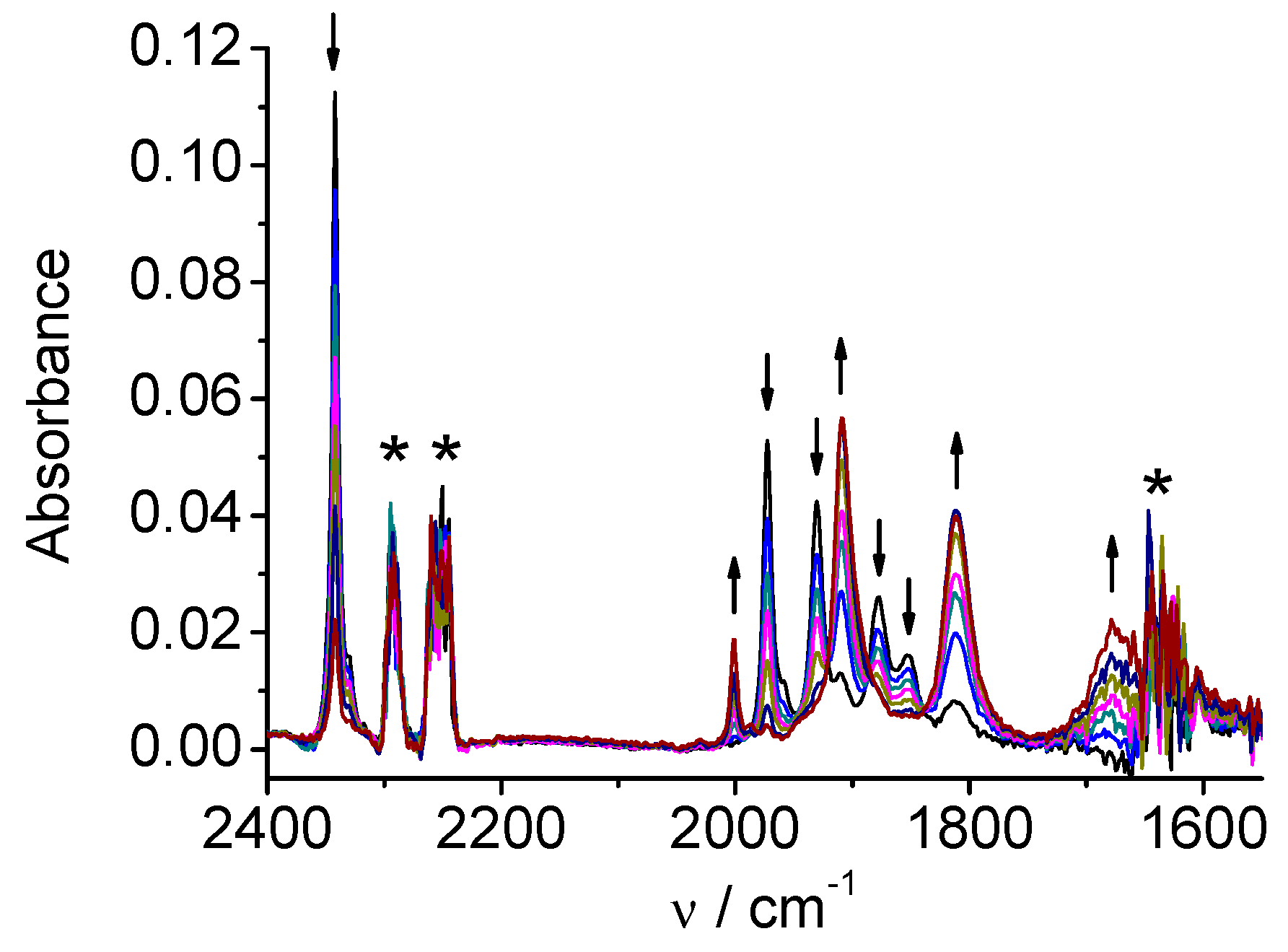

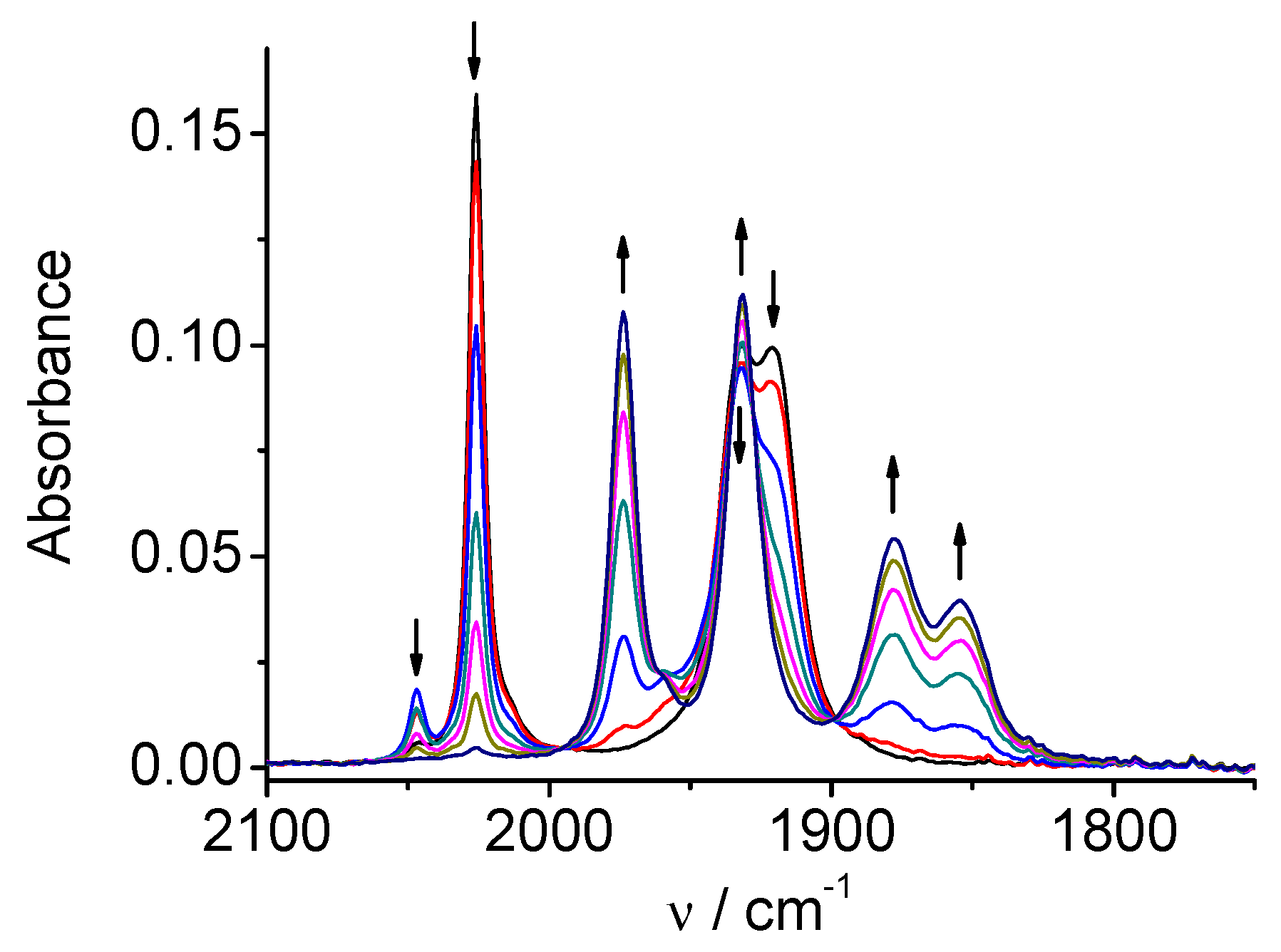

vs. Ag/AgCl [5a]. In-situ SEC spectra of

1 (

Figure 1) at the potential of the first reduction shows conversion of the original ν(CO) bands (2026, 1933, and 1922 cm

-1) into four ν(CO) bands (1973, 1931, 1878, and 1852 cm

-1). This behavior is typical for the formation of a Mn-Mn dimer, which has been recently demonstrated by Daasbjerg [9c] to proceed, for the similar Mn(bpy)(CO)

3Br complex, via its 2e

‾ reduction involving an extremely fast Br

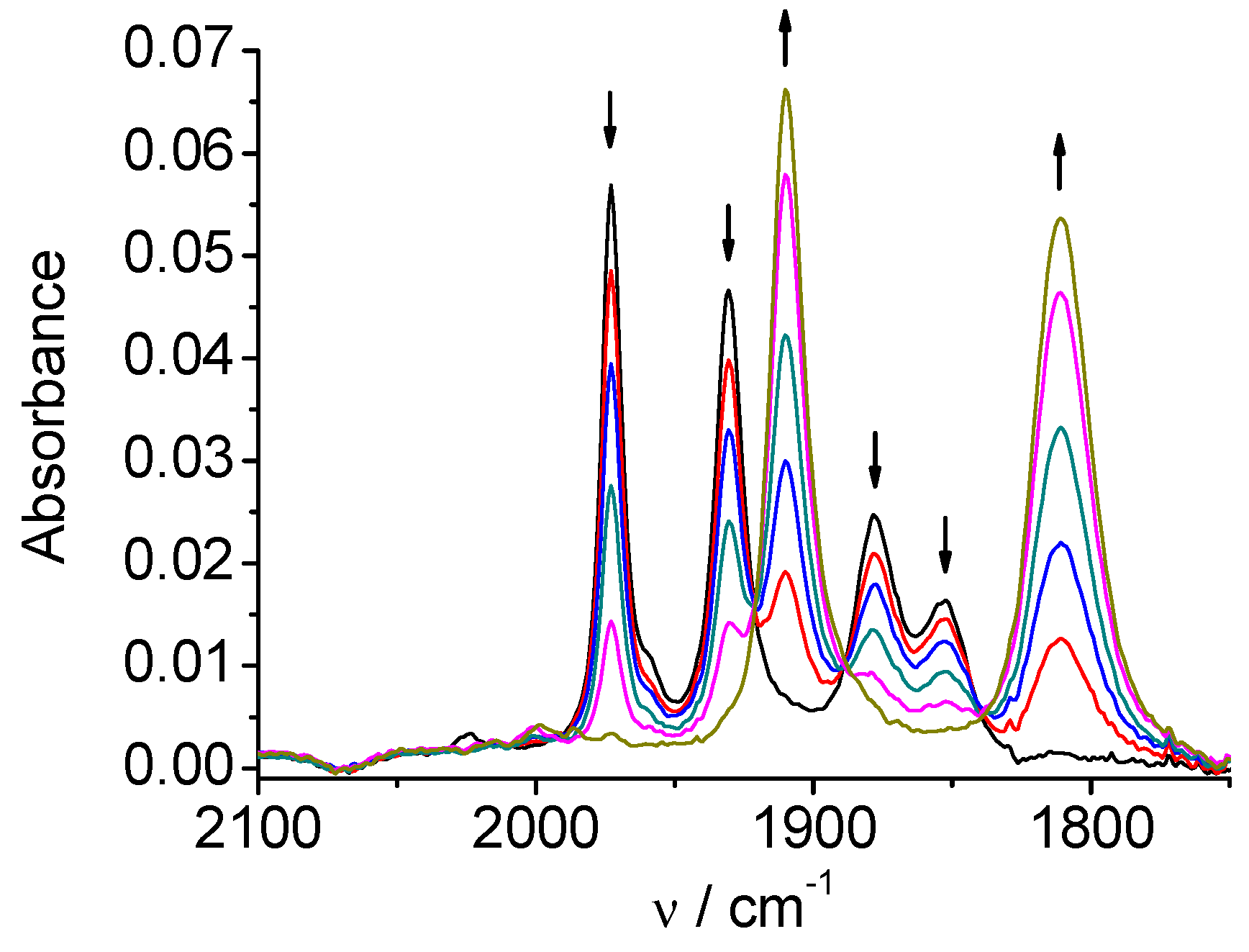

‾ release, and subsequent fast chemical reaction between the penta-coordinated anion and the neutral Mn complex. The second reduction of

1, which occurs at more negative potentials, splits the dimer leading to the monomeric penta-coordinated anion [Mn(apbpy)(CO)

3]

‾, which exhibits two ν(CO) bands, at 1909 and 1811 cm

-1 (

Figure 2). The overall mechanism is briefly summarized in

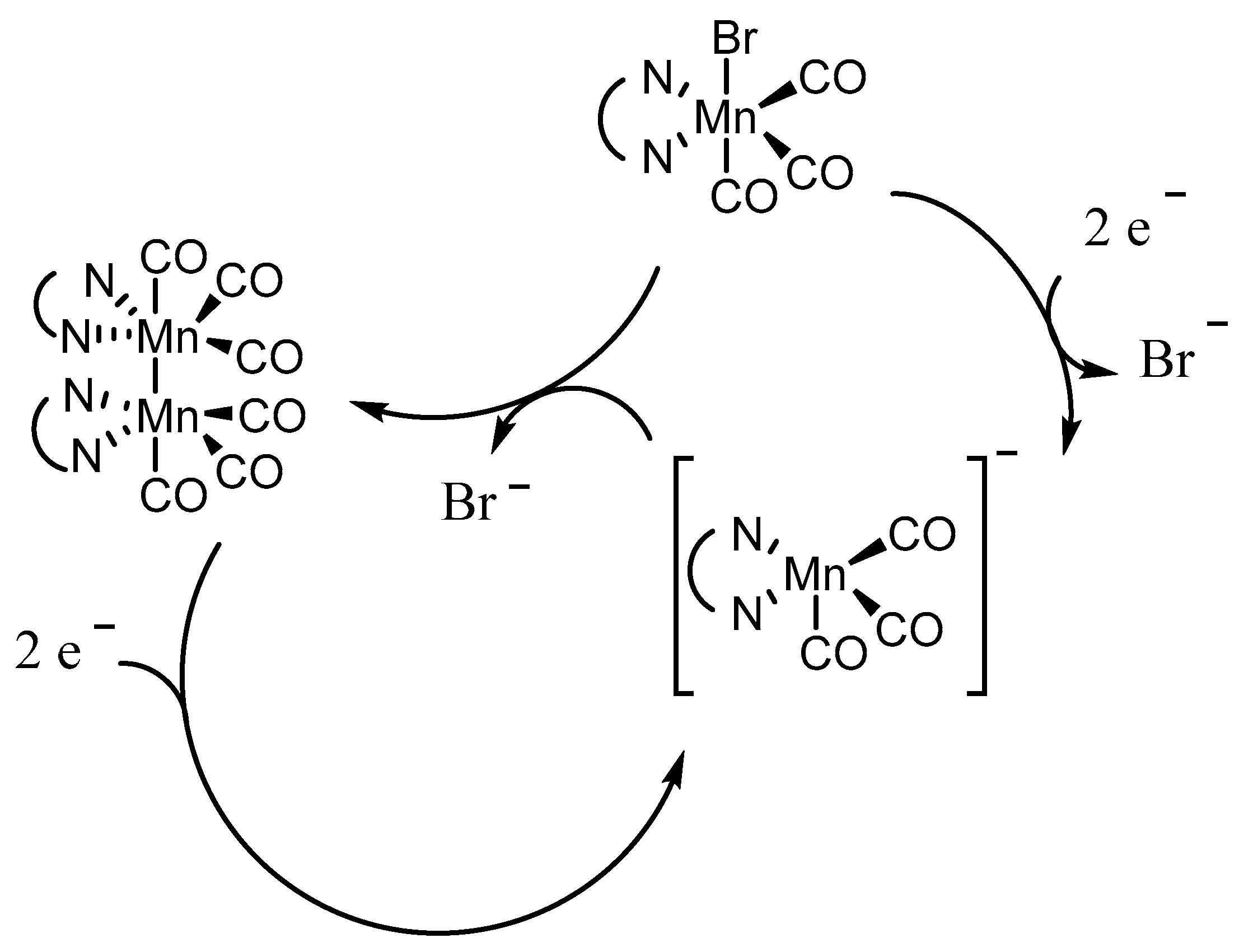

Scheme 2.

No significant difference was observed when the SEC experiment was performed at the first reduction with the solution saturated with carbon dioxide. Only when the reduction potential was changed to more negative values, behind the second reduction peak of

1, the band of dissolved CO

2 at 2342 cm

-1 decreases (

Figure S1) and bands at 1684 and 1643 cm

-1 increase. These two bands are assigned to the formation of HCO

3-/CO

32- system that usually appear after CO

2 reduction [8a, 10]. Although we cannot completely exclude the direct reduction of CO

2, the potential applied (-1.75 V

vs. Ag/AgCl) is not sufficiently negative to reduce pure CO

2 saturated solution in dry acetonitrile [5a], therefore these observations suggest a slow catalytic process not evident in CV experiments. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to perform reduction and SEC of Mn complexes at this negative potential in the absence of proton donors. In the relatively short time of SEC (but much longer with respect to CV) it is possible to evidence that the two bands at 1909 and 1811 cm

-1 partially lose intensity, but at the same time, the bands at 1684 and 1643 cm

-1 sharply increase (

Figure S1), which can be interpreted by a slow catalytic process, with probable catalyst decomposition in a longer time and at such negative potentials.

SEC performed at the second reduction peak (i.e. -1.41 V), but employing acetonitrile solution containing 5% of water, exhibits the typical catalytic CO

2 reduction (

Figure 3). It is possible to appreciate the faster and sharper decrease of the CO

2 absorption band at 2343 cm

-1. These results agree with the previous observations from cyclic voltammetry and exhaustive electrolysis experiments [5a] showing electrocatalysis in the presence of proton donors.

2.2. Re(apbpy)(CO)3Cl

CV of the rhenium complex

2 (

Figure S2) shows a first reversible reduction at E

1/2=-1.28 V and a second irreversible reduction at E

p=-1.74 V

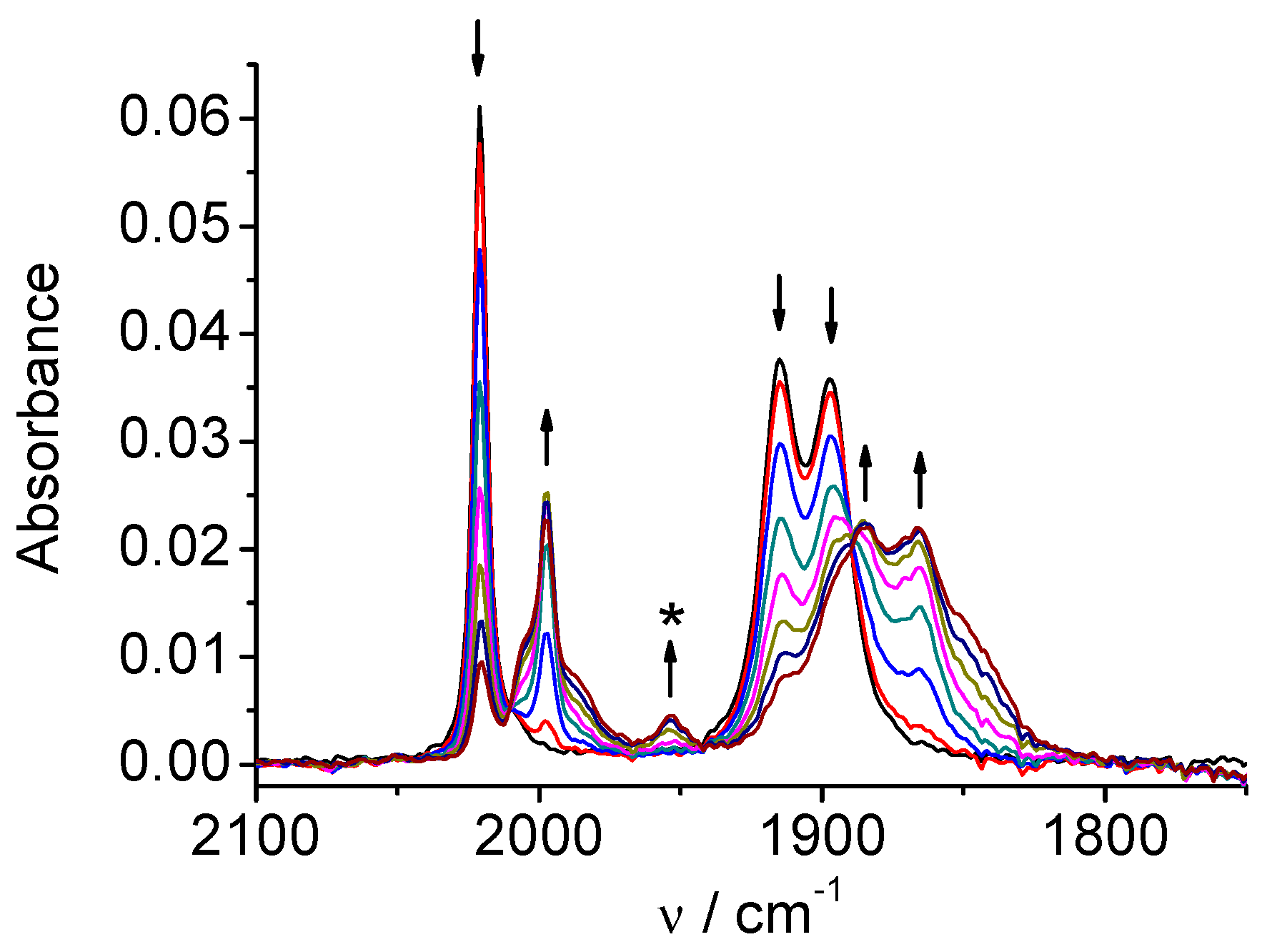

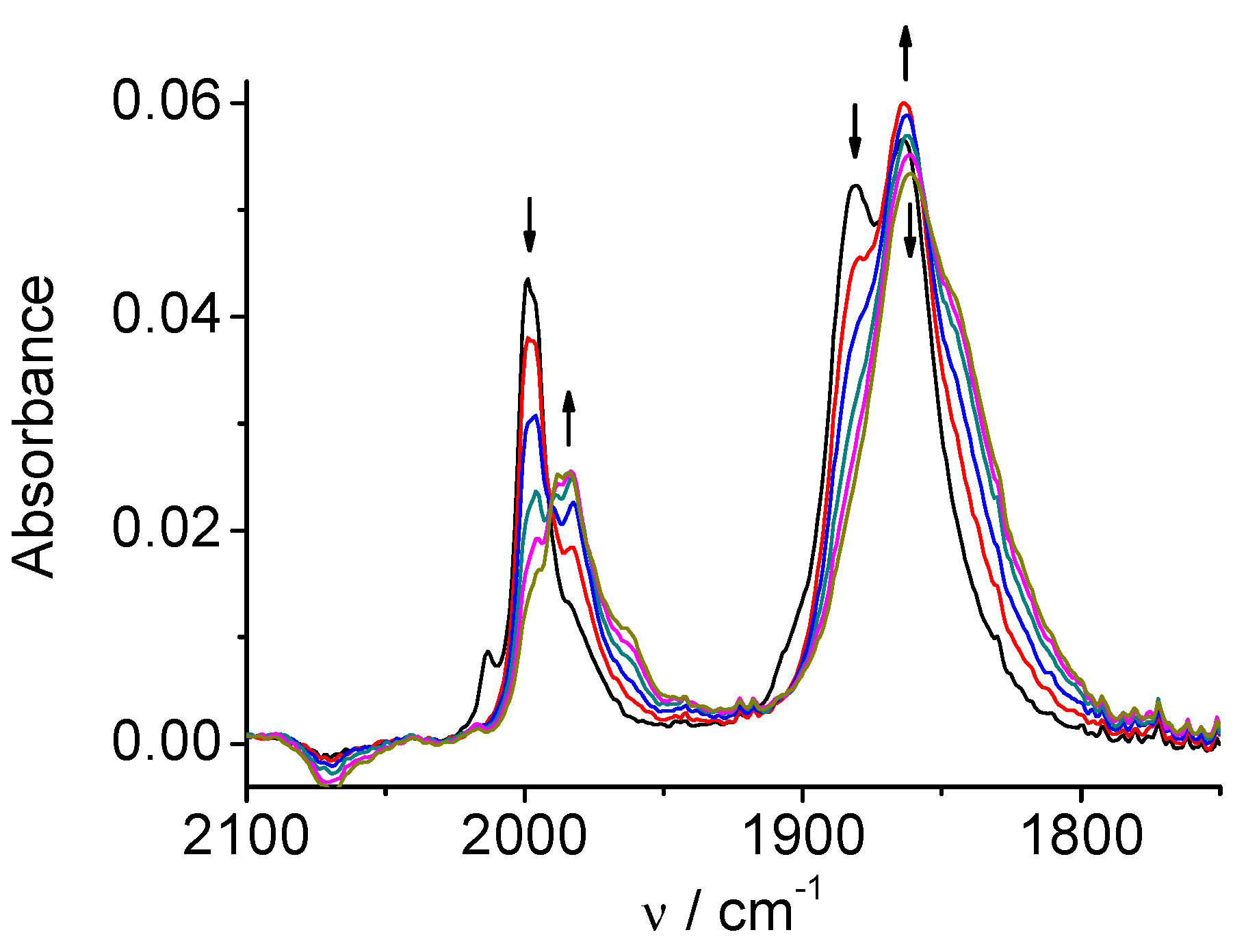

vs. Ag/AgCl. SECs of

2 show that the reduction mechanism significantly differs from that observed for the Mn analogue

1. On the reduction at the first peak (

Figure 4) the original three ν(CO) bands (2021, 1915, 1897 cm

-1) shift to lower wavenumbers (1997, 1886, 1866 cm

-1), but the character of the three-bands spectrum and consequently the coordination symmetry remains unchanged. Hence, the one-electron reduction product remains hexacoordinated and no dimerization takes place in contrast to the Mn complex

1. At the end of the electrolysis at the first peak (

Figure 4) the bands of the two-electron reduction product also appear due to close potentials of the first and second reduction peaks. The development of the bands of the two-electron reduction product continues during reduction at the second peak (

Figure 5) and finally, the spectrum consists of two main bands at 1986 cm

-1 and 1850 cm

-1 (wider, two almost degenerate vibrations) corresponding to the anion [Re(apbpy)(CO)

3]

‾.

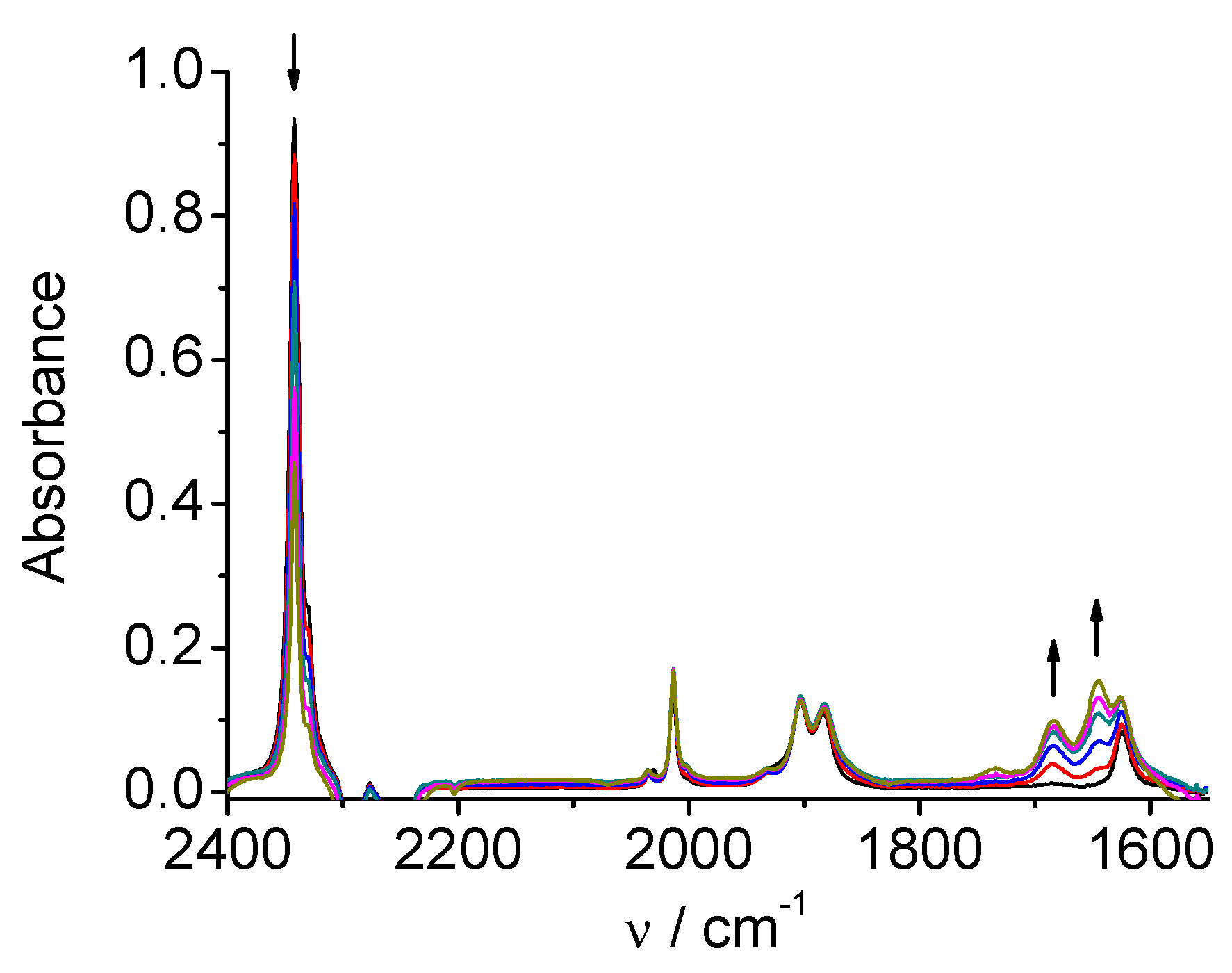

SEC experiments under CO

2 revealed the catalytic activity of the complex

2.

Figure 6 clearly shows that carbon dioxide is catalytically reduced already at potentials of the first reduction peak of the complex. The decrease of the CO

2 concentration in the solution (band at 2342 cm

-1) and formation of the products (HCO

3‾/CO

32‾, bands around 1685 and 1645 cm

-1) take place simultaneously with the reductive transition

2 to

2‾. The results thus show that although

2‾ does not lose Cl atom to form the penta-coordinated complex in CV time scale, the coordination bond is labilized and the halide can be substituted by solvent or substrate (CO

2). The labilized coordination site plays a key role in the catalytic mechanism. An indication that the catalytically active complex does not need to be necessarily formed through the second reduction of a bipyridine-tricarbonyl complex was mentioned previously for similar complexes [4f]. The complex

2 is a clear example, demonstrated by a relatively fast technique like SEC, that exhibits the catalytic activity when reduced only at the first one-electron step.

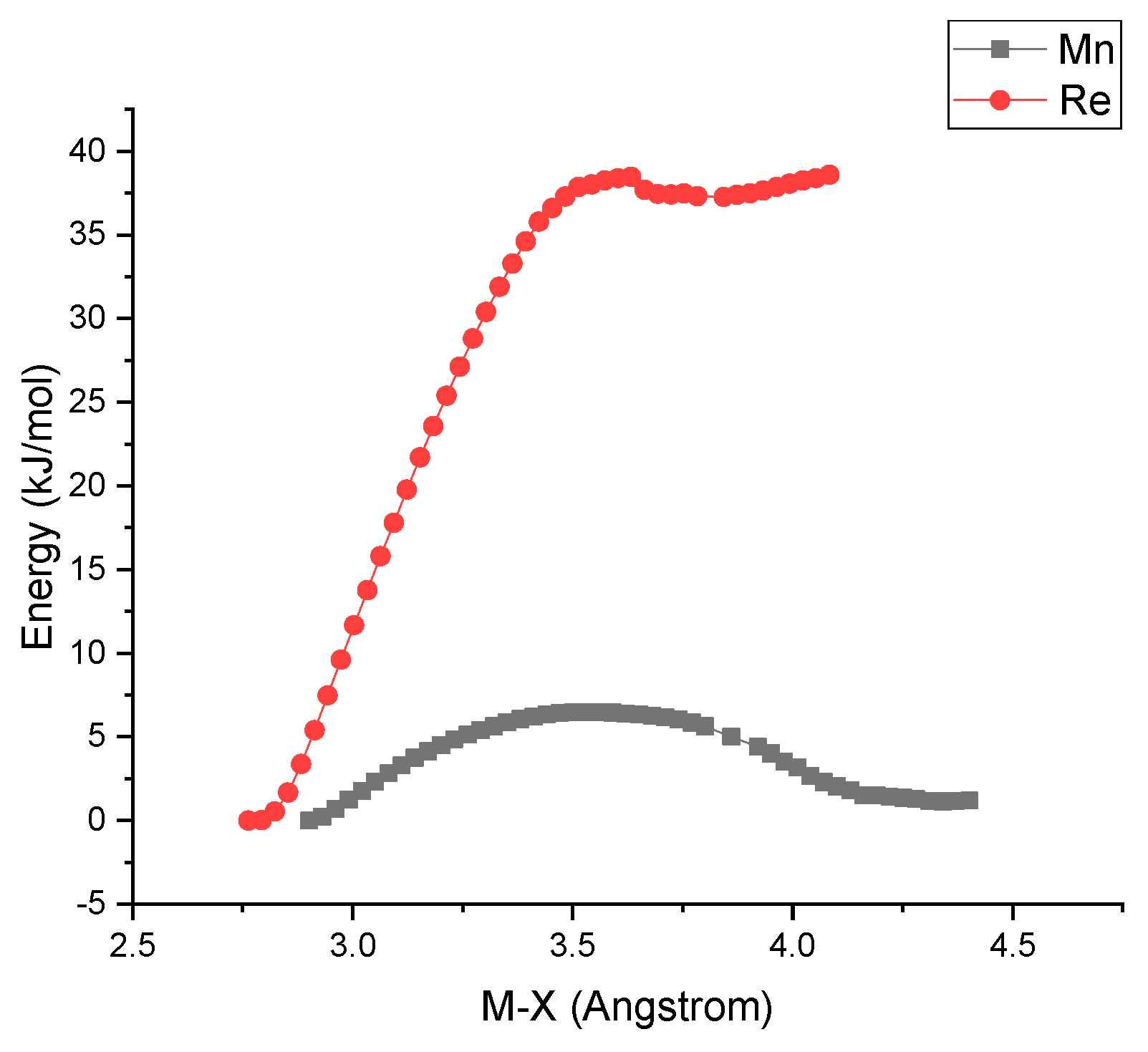

The metal-halogen bond (M-X) is much weaker in the Mn complex 1 rather than in the Re complex 2. For example, whereas complex 1 does not normally release Br- in MeCN solution at r.t., a rapid solvolysis of Mn-Br bond in MeCN has been observed in Mn complex carrying a bpy ligand modified with hydroxyphenyl moiety [9a], even at open circuit potential.

The kinetic of the halogen releasing process is greatly enhanced in Mn complexes whenever the corresponding reduced species are considered, accounting for the chemically irreversible and the reversible first reduction step of

1 and

2, respectively. DFT relaxed geometry scan of

1‾ and

2‾ as a function of M-X distances (

Figure 7) clearly shows that the radical anion Mn complex

1- has a much higher propensity to release the halogen than the Re counterpart

2‾. This is confirmed by the fact that the Mn-Br distance of the optimized geometry

1‾ is 0.294 Å longer than that of

1, while the Re-Cl bond of

2- is only 0.052 Å longer than that of

2 (see

Supplementary material for details).

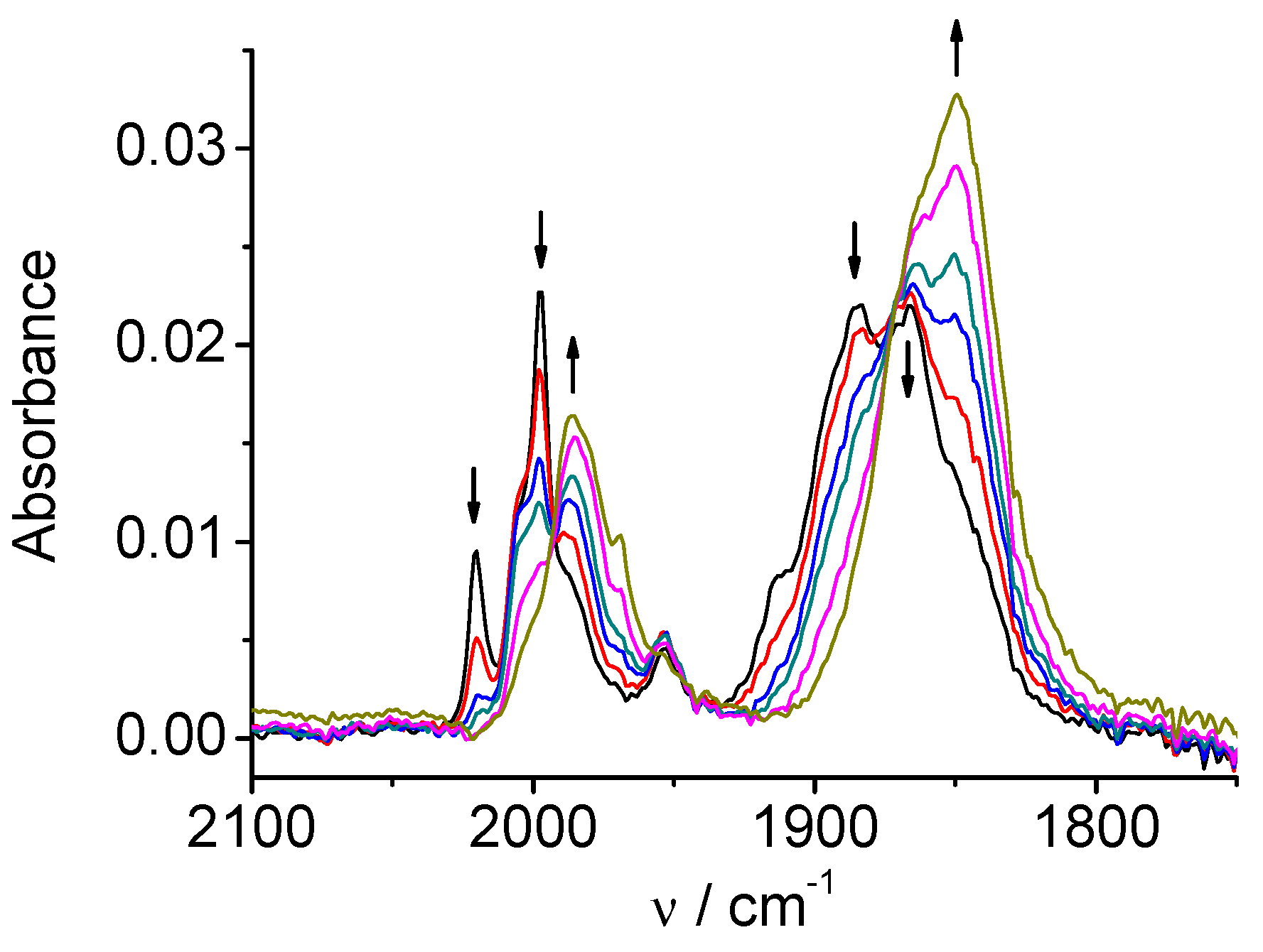

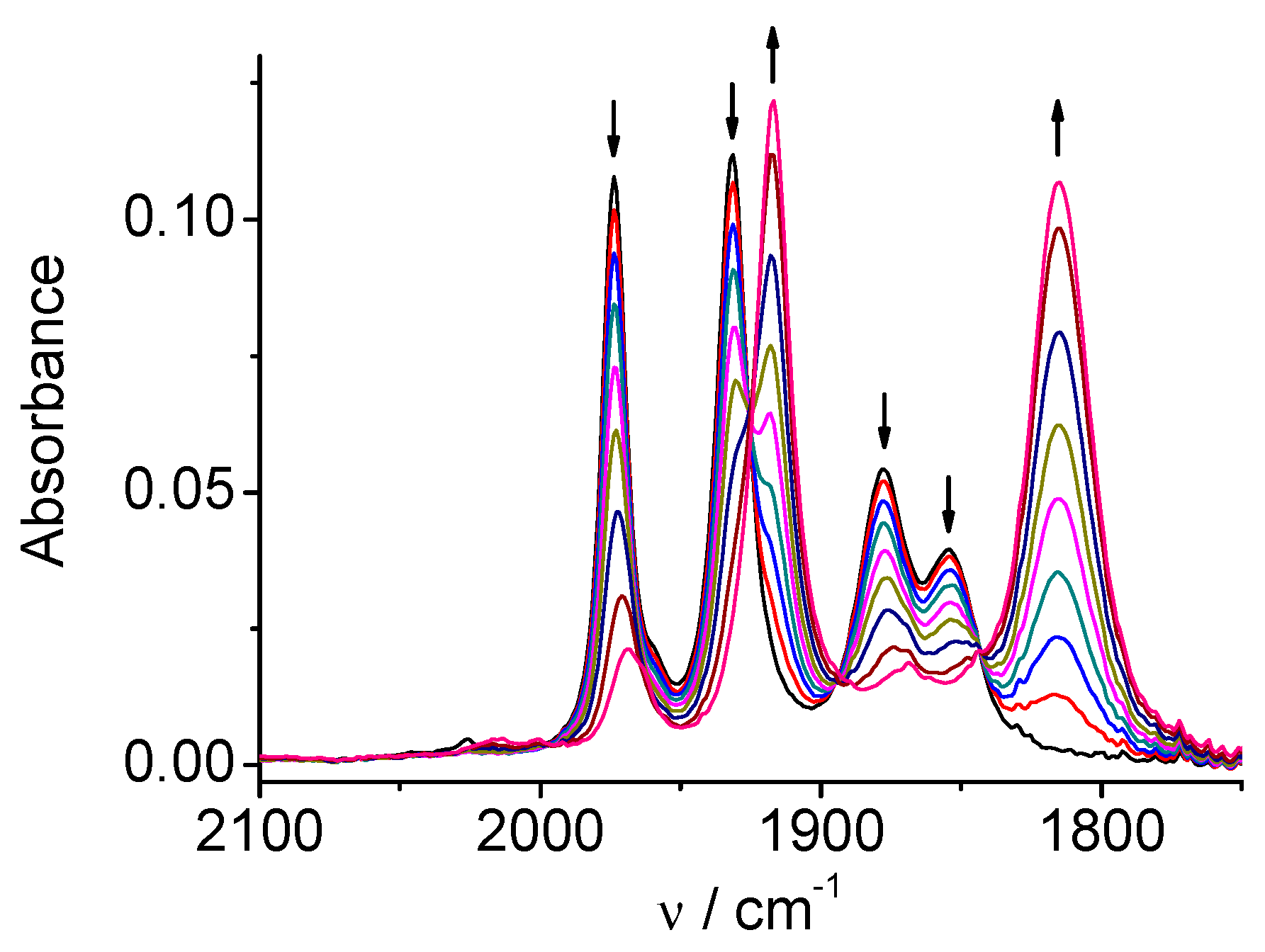

2.3. Mn(bpy-4,-4’-CF3-NMe2)(CO)3Br

CV of the Mn complex

3 (

Figure S3) consists in two chemically irreversible reductions at E

p=-1.27 and E

p=-1.41 V

vs. Ag/AgCl. SECs of

3 show similar results as observed for

1. The original three ν(CO) bands (2026, 1932, 1921 cm

-1) are converted at the first one-electron reduction (

Figure 8) into four bands of the dimer (1974, 1932, 1878, 1854 cm

-1) and the second reduction (

Figure 9) leads to the anionic species [Mn(bpy-4,4’-CF

3-NMe

2)(CO)

3]

‾ with the characteristic two-bands spectrum (1917, 1816(wide) cm

-1) in the carbonyl region. A small band at 2047 cm

-1 appears as transient, and can be ascribed to solvent-substituted species [Mn(bpy-4,4’-CF

3-NMe

2)(CO)

3(MeCN)]

+, which formation can be facilitated due to an electron-transfer catalytic (ETC) effect as observed in similar complexes [9a].

SEC experiments with carbon dioxide saturated solution showed that no CO

2 reduction takes place during electrolysis at potentials of the first reduction wave and the spectral change (

Figure S4) resembles to that under argon. Carbon-dioxide reduction starts only at the potential of the second reduction peak (

Figure S5, see bands HCO

3‾/CO

32‾ at 1685, 1647 cm

-1) similarly as observed for the compound

1.

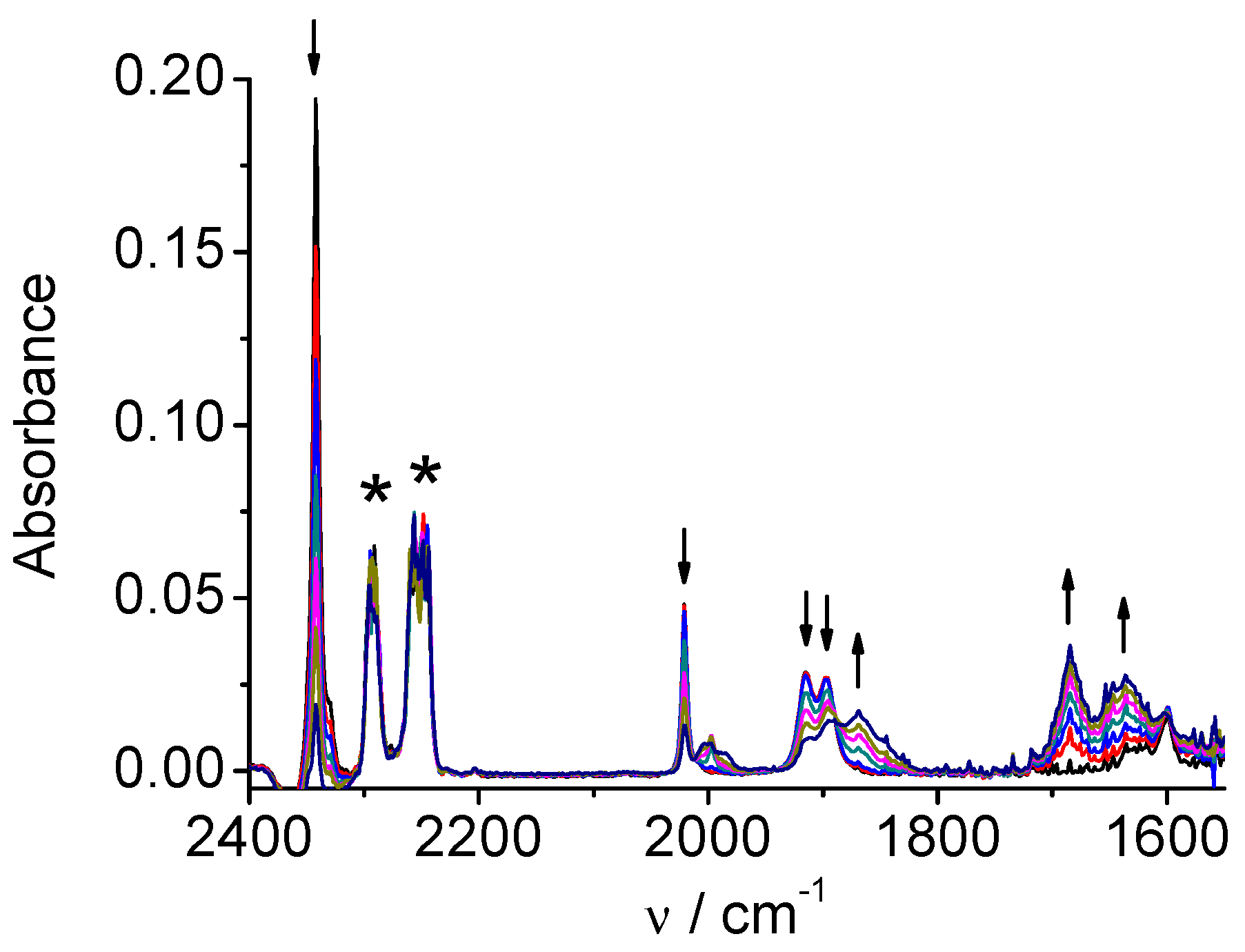

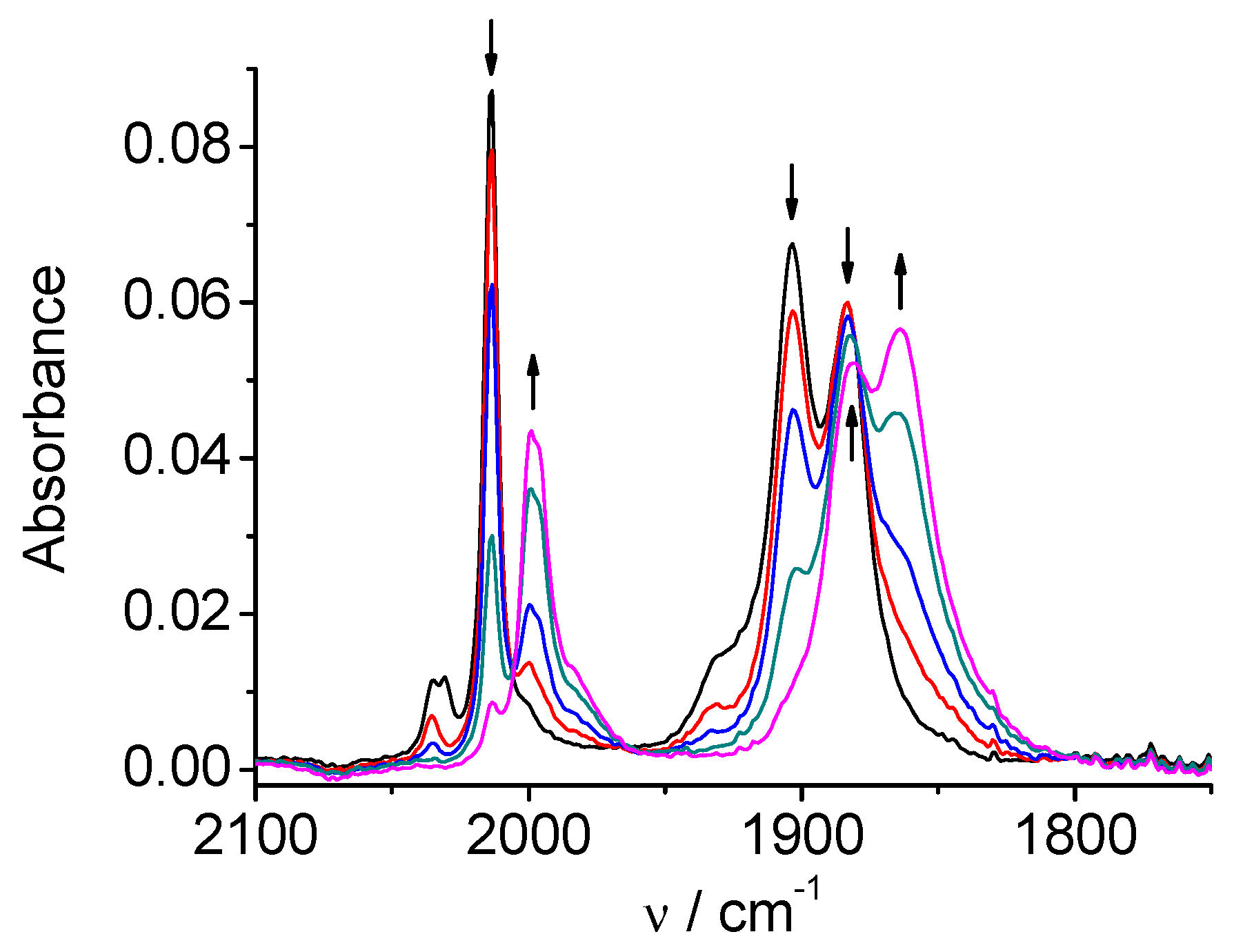

2.4. Re(bpy-4,4’-NMe2)(CO)3Cl

CV of the Re complex

4 (

Figure S6) displays a single two-electrons chemically irreversible reduction at E

p=-1.83 V and another much more negative reduction (ligand-centered) at E

p=-2.60 V

vs. Ag/AgCl. The two one-electron reduction steps are merged in the case of complex

4 into one two-electrons peak observed in CV [5b]. However, a carefully controlled spectroelectrochemical reduction revealed that the reduction steps can be distinguished according to spectral changes. The first spectral change during the reduction process resembles to that observed for one-electron reduction of the complex

2. Original carbonyl bands (2014, 1903, 1883 cm

-1) are shifted to lower wavelengths (1998, 1982, 1864 cm

-1,

Figure 10). Continued reduction at only slightly more negative potential (

Figure 11) produced an anion ([Re(bpy-4,4’-NMe

2)(CO)

3]

‾) with the ν(CO) bands at 1986 and 1862(wide) cm

-1, similarly as observed for the analogous rhenium complex

2.

SEC of

4 in a solution saturated with CO

2 produces bands at 1684 and 1646 cm

-1 (HCO

3‾/CO

32‾) simultaneously with decreasing of the CO

2 band at 2342 cm

-1. The original spectrum of the complex remains almost unchanged (

Figure 12). This result indicates that we observe a different SEC mechanism of the electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide: it begins at the first two-electron reduction potential of the complex

4, and the catalytic cycle restores the original neutral complex

4.

In order to prove the possible influence of a different solvent on the reduction mechanism, the SEC reductions of

1 – 4 were repeated using dimethylacetamide (DMA) / 0.1 M Bu

4NPF

6 as solvent, the same adopted in the case of photochemical tests [4c]. In the case of compounds

1 – 3 these experiments did not reveal any essential differences in the mechanism of the reduction and generated reduced species (

Figures S7–S12). But the reduction of complex

4 in DMA proceeds in one two-electron step directly to the anion ([Re(bpy-4,4’-NMe

2)(CO)

3]

‾ (

Figure S13). The one-electron intermediate observed in the acetonitrile solution is not detected in DMA solutions. The reason can be in a different substitution equilibrium chloride/solvent for the 1e

‾ reduced intermediate and consequently in a different intrinsic reduction mechanism (EEC

vs. ECE). The principal ν(CO) frequencies observed experimentally from SEC in both solvents (acetonitrile and dimethylacetamide) are summarized in

Table 2.

3. Discussion and Conclusion

IR spectroelectrochemistry has been used to highlight the catalytic behavior of four bpy complexes of Mn and Re. The CV of Mn complex 1 and that of Re complex 2 shows a chemical irreversible and reversible first reduction, respectively. The corresponding SEC experiments clearly indicate that at the first reduction 2 is already catalytically active in the CO2 conversion. Only at more negative potentials 1 displays an unprecedent very slow catalytic activity, which is greatly enhanced by the presence of 5% of water as proton donor. The higher lability of M-X bond in 1‾ with respect to 2‾ has been interpreted by DFT calculations. Complexes 3 and 4 show analogue catalytic activities, with the latter characterized by an overlapped 2e first reduction, partially resolved by SEC. In dimethylacetamide solutions 4 is reduced by two electrons and SEC cannot discriminate the single steps. These results highlight the suitability and effectiveness of SEC in investigating such catalytic processes, in a timescale slight longer than that in CV.

4. Materials and Methods

Synthesis. The reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. 4-(4-aminophenyl)-2,2’-bipyridine ligand was synthesized according to published procedures [

11]. Re and Mn carbonyl complexes were synthesized reacting the substituted bipyridines with the corresponding precursor, Re(CO)

5Cl or Mn(CO)

5Br, following a similar synthetic approach as previously reported [5a, 5b].

Cyclic Voltammetry. Cyclic voltammetry experiments were performed with a Biologic 300SP potentiostat. A single-compartment cell was employed, equipped with a glassy carbon electrode (GCE, Ø = 1 mm) as the working electrode, a Pt counter electrode and a Ag/AgCl (KCl 3 M) reference electrode. Acetonitrile (MeCN) and dimethylacetamide (DMA) used as solvent were freshly distilled over calcium hydride. Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (Bu4NPF6, Sigma-Aldrich, 98%) was recrystallized three times from ethanol solutions and used as supporting electrolyte (0.1 M). The Ar- and CO2-saturated conditions were achieved by purging gases for 5 min before the experiment.

Spectroelectrochemistry. Spectroelectrochemical experiments were performed using a FTIR spectrometer Nicolet iS50 NIR-FTIR equipped with an optically transparent thin-layer electrode (OTTLE) cell, employing Pt working and counter electrodes and an Ag wire as pseudoreference electrode [

17].

DFT Calculations. Gaussian 09 Rev.D.01 [

12] was used for computational studies. The conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) [

13] with acetonitrile as solvent was included to account for solvent effects. Geometry optimizations were carried out without any constraints using the B3LYP functional [

14], the optimized def2-TZVP basis set for metals and halogens, and the def2-SVP basis set for all other atoms [

15]. The D3 version of Grimme’s dispersion with the Becke–Johnson damping scheme [

16] method was applied. Thermal corrections for entropy and enthalpy at 298 K to the electronic energies were calculated, and the nature of all stationary points were confirmed by normal-mode analysis (no imaginary frequencies were found). For radical anions, unrestricted Kohn– Sham formalism (UKS) was adopted.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Spectroelectrochemistry of

1 in MeCN under CO

2: reduction behind the second reduction peak (-2.1 V

vs. Fc/Fc

+); Figure S2: Cyclic Voltammetry of

2 in MeCN under Ar; Figure S3: Cyclic Voltammetry of

3 in MeCN under Ar and under CO

2; Figure S4: Spectroelectrochemistry of

3 in MeCN under CO

2: first reduction; Figure S5: Spectroelectrochemistry of

3 in MeCN under CO

2: second reduction; Figure S6: Cyclic Voltammetry of

4 in MeCN under Ar and under CO

2; Figure S7: Spectroelectrochemistry of

1 in DMA: first reduction; Figure S8: Spectroelectrochemistry of

1 in DMA: second reduction; Figure S9: Spectroelectrochemistry of

2 in DMA: first reduction; Figure S10: Spectroelectrochemistry of

2 in DMA: second reduction; Figure S11: Spectroelectrochemistry of

3 in DMA: first reduction; Figure S12: Spectroelectrochemistry of

3 in DMA: second reduction; Figure S13: Spectroelectrochemistry of

4 in DMA: two-electron reduction; DFT optimized structures of

1,

1‾,

2, and

2‾.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, resources, writing—review and editing, C.N., R.G. and J.F.; methodology and investigations, A.B., C.R., L.R., R.S. and J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B. and J.F.; supervision, C.N.; funding acquisition, C.N. and R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the PNRR MOST@UNITO project and the CADIVAPE PRIN project (grant number 2022FWAF2M); C.R. gratefully acknowledge CIRCC (Progetto Competitivo 2020 CMPT200224) for financial support. J.F. and R.S. acknowledge the Czech Academy of Sciences (RVO: 61388955).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds 1-4 are available from the authors.

References

- Rotundo, L.; Gobetto, R.; Nervi, C. Curr. Opin. Green Sust. Chem. 2021, 31, 100509. [CrossRef]

- Aresta, M.; Dibenedetto, A.; Angelini, A. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1709–1742. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- a) J. Ronge, T. Bosserez, D. Martel, C. Nervi, L. Boarino, F. Taulelle, G. Decher, S. Bordiga, J. A. Martens, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7963-7981; b) B. Tang, F.-X. Xiao, ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 9023-9057; c) J. Cheon, J. Y. Yang, M. Koper, O. Ishitani, I 2022, 55, 931-932.

- a) F. M. Stuardi, A. Tiozzo, L. Rotundo, J. Leclaire, R. Gobetto, C. Nervi, Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202104377 (202104371-202104379); b) J. Filippi, L. Rotundo, R. Gobetto, H. A. Miller, C. Nervi, A. Lavacchi, F. Vizza, Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 416, 129050; c) L. Rotundo, D. C. Grills, R. Gobetto, E. Priola, C. Nervi, D. E. Polyansky, E. Fujita, ChemPhotoChem 2021, 5, 526-537; d) L. Rotundo, D. E. Polyansky, R. Gobetto, D. C. Grills, E. Fujita, C. Nervi, G. F. Manbeck, Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 12187-12199; e) L. Rotundo, J. Filippi, R. Gobetto, H. A. Miller, R. Rocca, C. Nervi, F. Vizza, Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 775-777; f) L. Rotundo, C. Garino, E. Priola, D. Sassone, H. Rao, B. Ma, M. Robert, J. Fiedler, R. Gobetto, C. Nervi, Organometallics 2019, 38, 1351-1360.

- a) C. Sun, L. Rotundo, C. Garino, L. Nencini, S. S. Yoon, R. Gobetto, C. Nervi, ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 3219-3229; b) L. Rotundo, E. Azzi, A. Deagostino, C. Garino, L. Nencini, E. Priola, P. Quagliotto, R. Rocca, R. Gobetto, C. Nervi, Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 417.

- a) M. Bourrez, F. Molton, S. Chardon-Noblat, A. Deronzier, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9903-9906; b) F. Franco, C. Cometto, F. Ferrero Vallana, F. Sordello, E. Priola, C. Minero, C. Nervi, R. Gobetto, Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 14670-14673.

- Franco, F.; Cometto, C.; Garino, C.; Minero, C.; Sordello, F.; Nervi, C.; Gobetto, R. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 296–304. [CrossRef]

- a) F. P. A. Johnson, M. W. George, F. Hartl, J. J. Turner, Organometallics 1996, 15, 3374-3387; b) J. O. Taylor, G. Neri, L. Banerji, A. J. Cowan, F. Hartl, Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 5564-5578; c) M. R. Madsen, M. H. Rønne, M. Heuschen, D. Golo, M. S. G. Ahlquist, T. Skrydstrup, S. U. Pedersen, K. Daasbjerg, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20491-20500.

- a) F. Franco, C. Cometto, L. Nencini, C. Barolo, F. Sordello, C. Minero, J. Fiedler, M. Robert, R. Gobetto, C. Nervi, Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 4782-4793; b) M. H. Rønne, D. Cho, M. R. Madsen, J. B. Jakobsen, S. Eom, É. Escoudé, H. C. D. Hammershøj, D. U. Nielsen, S. U. Pedersen, M.-H. Baik, T. Skrydstrup, K. Daasbjerg, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4265-4275; c) M. H. Rønne, M. R. Madsen, T. Skrydstrup, S. U. Pedersen, K. Daasbjerg, ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 2108-2114; d) M. R. Madsen, J. B. Jakobsen, M. H. Rønne, H. Liang, H. C. D. Hammershøj, P. Nørby, S. U. Pedersen, T. Skrydstrup, K. Daasbjerg, Organometallics 2020, 39, 1480-1490.

- Cheng, S.C.; Blaine, C.A.; Hill, M.G.; Mann, K.R. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 7704–7708. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, O.; Borgström, M.; Lomoth, R.; Palmblad, M.; Bergquist, J.; Hammarström, L.; Sun, L.; Åkermark, B. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 2908–2918. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. J. Frisch, G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, B. Mennucci, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, M. Caricato, X. Li, H. P. Hratchian, A. F. Izmaylov, J. Bloino, G. Zheng, J. L. Sonnenberg, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, J. A. J. Montgomery, J. R. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. Bearpark, J. J. Heyd, E. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, N. Rega, J. Millam, M. Klene, J. E. Knox, J. B. Cross, V. Bakken, C. Adamo, J. Jaramillo, R. Gomperts, R. E. Stratmann, O. Yazyev, A. J. Austin, R. Cammi, C. Pomelli, J. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, V. G. Zakrzewski, G. A. Voth, P. Salvador, J. J. Dannenberg, S. Dapprich, A. D. Daniels, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, J. V. Ortiz, J. Cioslowski, D. J. Fox, Revision D.01 ed., Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009.

- a) S. Miertuš, E. Scrocco, J. Tomasi, J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 55, 117-129; b) M. Cossi, G. Scalmani, N. Rega, V. Barone, J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 43-54.

- a) A. D. Becke, J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648-5652; b) C. Lee, W. Yang, R. G. Parr, Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter 1988, 37, 785-789.

- a) F. Weigend, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057-1065; b) F. Weigend, R. Ahlrichs, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297-3305.

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L.J. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- a) M. Krejčik, M. Daněk, F. Hartl, J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1991, 317, 179–187, b) W. Kaim, J. Fiedler, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3373–3382.

Scheme 1.

Sketch of the complexes under study.

Scheme 1.

Sketch of the complexes under study.

Scheme 2.

Summary of the overall mechanism of [Mn(bpy-type)(CO)3Br] complexes leading to the Mn anion, the active catalyst in electrochemical CO2 reduction.

Scheme 2.

Summary of the overall mechanism of [Mn(bpy-type)(CO)3Br] complexes leading to the Mn anion, the active catalyst in electrochemical CO2 reduction.

Figure 1.

SEC of 1 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the first reduction peak.

Figure 1.

SEC of 1 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the first reduction peak.

Figure 2.

SEC of 1 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the second reduction peak.

Figure 2.

SEC of 1 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the second reduction peak.

Figure 3.

SEC of 1 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 / 5% H2O under CO2: potential applied at the second reduction peak (* - distorted due to strong absorption of the MeCN/water mixture as solvent).

Figure 3.

SEC of 1 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 / 5% H2O under CO2: potential applied at the second reduction peak (* - distorted due to strong absorption of the MeCN/water mixture as solvent).

Figure 4.

SEC of 2 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the first reduction peak (* = unidentified side-product).

Figure 4.

SEC of 2 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the first reduction peak (* = unidentified side-product).

Figure 5.

SEC of 2 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the second reduction peak.

Figure 5.

SEC of 2 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the second reduction peak.

Figure 6.

SEC of 2 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 under CO2: potential applied at the first reduction peak (* - artefact due to strong absorption of solvent).

Figure 6.

SEC of 2 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 under CO2: potential applied at the first reduction peak (* - artefact due to strong absorption of solvent).

Figure 7.

Relaxed geometry scan for 1‾ (black squares) and 2‾ (red circles) as a function of M-X distances in acetonitrile as solvent.

Figure 7.

Relaxed geometry scan for 1‾ (black squares) and 2‾ (red circles) as a function of M-X distances in acetonitrile as solvent.

Figure 8.

SEC of 3 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the first reduction peak.

Figure 8.

SEC of 3 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the first reduction peak.

Figure 9.

SEC of 3 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the second reduction peak.

Figure 9.

SEC of 3 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6: potential applied at the second reduction peak.

Figure 10.

SEC of 4 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 under CO2: potential applied at the first reduction peak, during the early stage of the reduction.

Figure 10.

SEC of 4 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 under CO2: potential applied at the first reduction peak, during the early stage of the reduction.

Figure 11.

SEC of 4 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 under CO2: potential applied about 25 mV more negative than the first reduction peak, towards the end of the reduction.

Figure 11.

SEC of 4 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 under CO2: potential applied about 25 mV more negative than the first reduction peak, towards the end of the reduction.

Figure 12.

SEC of 4 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 under CO2: potential applied at the first 2e reduction peak.

Figure 12.

SEC of 4 in MeCN / 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 under CO2: potential applied at the first 2e reduction peak.

Table 1.

Reduction potentials in MeCN solutions, potentials

vs. Ag/AgCl, TONs and faradic efficiency (FE) of the four complexes under study [

5].

Table 1.

Reduction potentials in MeCN solutions, potentials

vs. Ag/AgCl, TONs and faradic efficiency (FE) of the four complexes under study [

5].

| Complex |

CPE (V) |

Ep1(V) |

Mixture |

Time (min) |

Ep2(V) |

TONCO

|

FECO% |

| 1 |

-1.73 |

-1,51 |

4% water |

90 |

-1,76 |

12 |

93 1

|

| 2 |

-2.00 |

-1,70 |

8% MeOH |

120 |

-2,12 |

12 |

96,4 2

|

| 3 |

-1.50 |

-1.31 |

5% water |

420 |

-1,42 |

26 |

84 3

|

| 4 |

-2.00 |

-1.82 |

5% MeOH |

600 |

-1,82 |

31,5 |

100 4

|

Table 2.

Carbonyl stretching frequencies (cm-1) from SEC measurements.

Table 2.

Carbonyl stretching frequencies (cm-1) from SEC measurements.

| Complex |

Solvent |

Native state |

1e reduction state |

2e reduction state |

| 1 |

MeCN |

2026, 1933, 1922 |

1973, 1931, 1878, 1852 |

1909, 1811 |

| DMA |

2021, 1930, 1912 |

1969, 1927, 1875, 1853 |

1907, 1810 |

| 2 |

MeCN |

2021, 1915, 1897 |

1997, 1886, 1866 |

1986, 1850 |

| DMA |

2016, 1912, 1890 |

1992, 1879, 1860 |

1981, 1860 |

| 3 |

MeCN |

2026, 1932, 1921 |

1974, 1932, 1878, 1854 |

1917, 1816 |

| DMA |

2021, 1930, 1912 |

1972, 1929, 1877, 1855 |

1916, 1815 |

| 4 |

MeCN |

2014, 1903, 1883 |

1998, 1882, 1864 |

1986, 1862 |

| DMA |

2009, 1899, 1877 |

not observed |

1980, 1859 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).