Submitted:

14 September 2023

Posted:

15 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. SAM/SAH measurements

2.2. RNA-seq

2.3. In-depth Examination of the Most Significantly Altered Signalling Pathways

2.4. Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition and E-cadherin/β-catenin/Wnt pathway

2.5. Differential Expression of Cyclins and Cell Cycle Regulation Signaling

2.6. MYC, STAT3 and Human Embryonic Stem Cell Pluripotency Signaling

2.7. The tumor microenvironment pathway

2.8. G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling

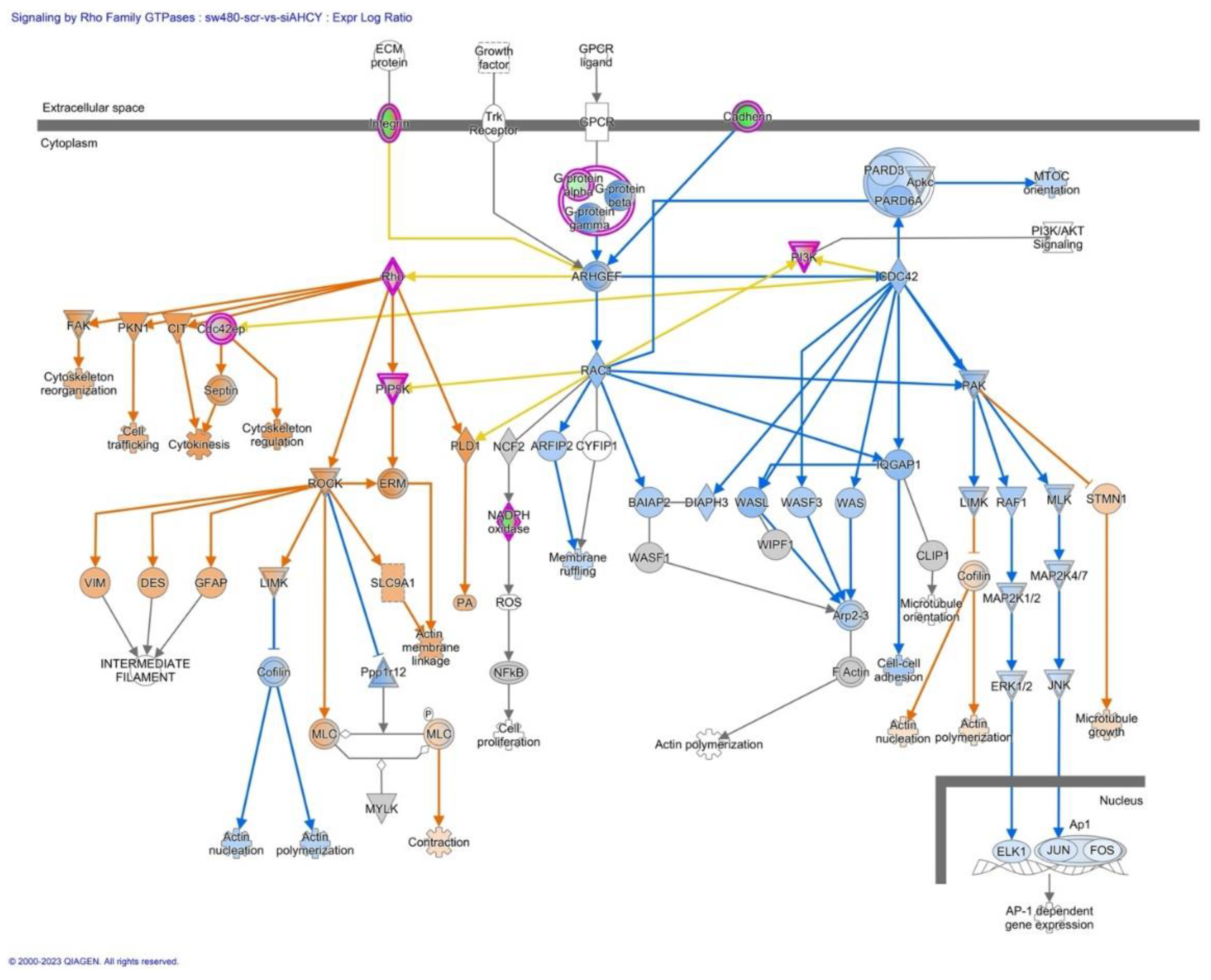

2.9. Signaling by Rho Family GTPases

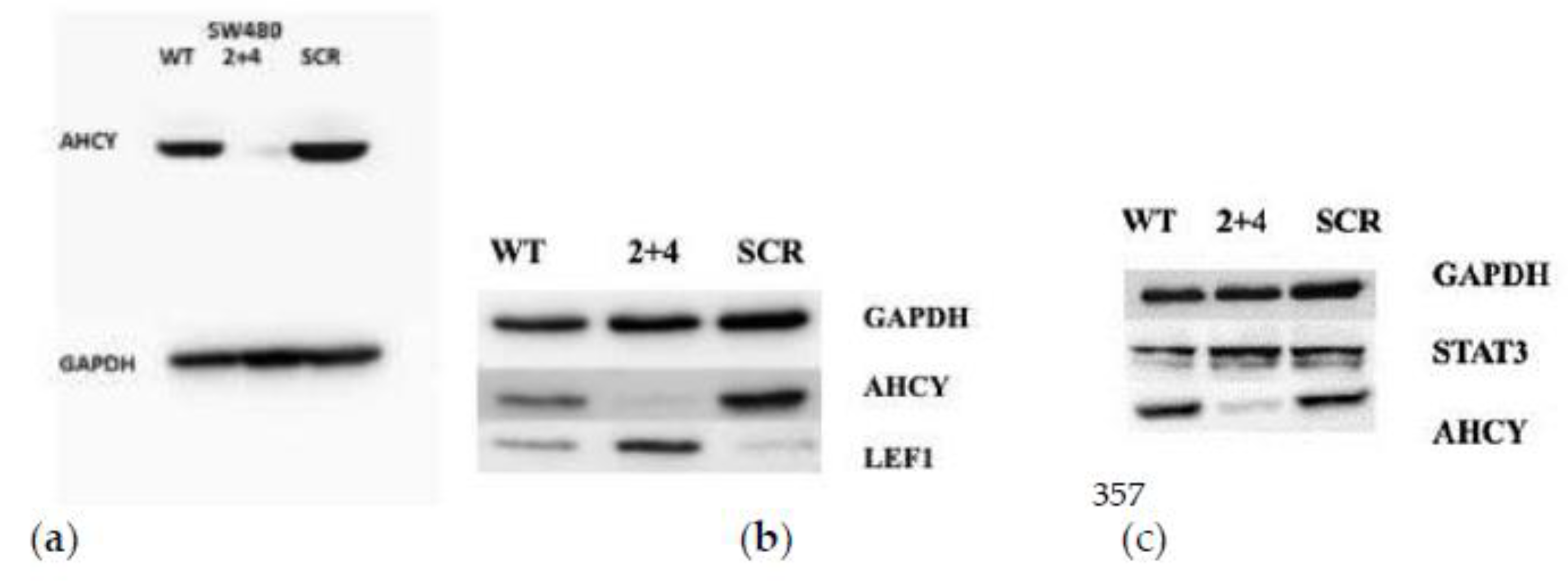

2.10. Western blotting

3. Discussion

3.1. Additional Pathways Perturbations3.2. Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition

3.3. Differential Expression of Cyclins and Cell Cycle Regulation Signaling

3.4. MYC, STAT3 and Human Embryonic Stem Cell Pluripotency Signaling

3.5. The tumor microenvironment pathway

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture:

4.2. Viability Assay:

4.3. Lentivirus Production:

4.4. Cell Culture and Antibiotic Resistance Testing

4.5. Lentiviral Transduction:

4.6. Transcriptome profiling – RNA-Seq

4.7. Statistical Analysis:

5. Conclusions

- Calcium Signaling: Calcium signaling can intersect with the non-canonical Wnt pathway through various mechanisms. Calcium ions can modulate the activity of Wnt signaling components, including LEF1, by affecting β-catenin stability, the interaction between β-catenin and LEF1, or downstream signaling events. The PCP pathway after Wnt activation is also responsible for gene expression regulation but also for cell cytoskeleton remodeling together with ROCK and JNK kinases. The WNT/Ca2+ pathway is associated with muscle contraction, gene transcription, and enzyme activation and activates both β-catenin-dependent and β-catenin-independent pathways.

- Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT): LEF1, as a downstream effector of the canonical Wnt pathway, can participate in the regulation of EMT. EMT is a dynamic process involved in tissue remodeling and cancer progression. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway, including the involvement of LEF1, has been linked to the induction or maintenance of EMT programs.

- G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) Signaling: GPCR signaling can intersect with the canonical Wnt pathway through various mechanisms. Wnt ligands can be activated by GPCRs kinases, leading to the activation of downstream signaling cascades, which can modulate the canonical Wnt pathway and potentially influence the activity of LEF1, and we see in our RNAseq data lower differential expression of GPCRs.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baric I, Fumic K, Glenn B, Cuk M, Schulze A, Finkelstein JD, James SJ, Mejaski-Bosnjak V, Pazanin L, Pogribny IP, Rados M, Sarnavka V, Scukanec-Spoljar M, Allen RH, Stabler S, Uzelac L, Vugrek O, Wagner C, Zeisel S, Mudd SH. S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency in a human: a genetic disorder of methionine metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 23;101(12):4234-9. [CrossRef]

- Santiago L, Daniels G, Wang D, Deng FM, Lee P. Wnt signaling pathway protein LEF1 in cancer, as a biomarker for prognosis and a target for treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2017 Jun 1;7(6):1389-1406. PMID: 28670499; PMCID: PMC5489786.

- De La Haba G, Cantonini GL. The enzymatic synthesis of S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine from adenosine and homocysteine. J Biol Chem. 1959 Mar;234(3):603-8. 1: PMID, 1364.

- Borchardt RT, Huber JA, Wu YS. Potential inhibitors of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. 4. Further modifications of the amino and base portions of S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine. J Med Chem. 1976 Sep;19(9):1094-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loehrer FM, Angst CP, Brunner FP, Haefeli WE, Fowler B. Evidence for disturbed S-adenosylmethionine : S-adenosylhomocysteine ratio in patients with end-stage renal failure: a cause for disturbed methylation reactions? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998 Mar;13(3):656-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caudill MA, Wang JC, Melnyk S, Pogribny IP, Jernigan S, Collins MD, Santos-Guzman J, Swendseid ME, Cogger EA, James SJ. Intracellular S-adenosylhomocysteine concentrations predict global DNA hypomethylation in tissues of methyl-deficient cystathionine beta-synthase heterozygous mice. J Nutr. 2001 Nov;131(11):2811-8. [CrossRef]

- Vugrek O, Beluzić R, Nakić N, Mudd SH. S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (AHCY) deficiency: two novel mutations with lethal outcome. Hum Mutat. 2009 Apr;30(4):E555-65. [CrossRef]

- Grubbs R, Vugrek O, Deisch J, Wagner C, Stabler S, Allen R, Barić I, Rados M, Mudd SH. S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency: two siblings with fetal hydrops and fatal outcomes. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010 Dec;33(6):705-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buist NR, Glenn B, Vugrek O, Wagner C, Stabler S, Allen RH, Pogribny I, Schulze A, Zeisel SH, Barić I, Mudd SH. S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency in a 26-year-old man. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006 Aug;29(4):538-45. [CrossRef]

- Beluzić R, Cuk M, Pavkov T, Fumić K, Barić I, Mudd SH, Jurak I, Vugrek O. A single mutation at Tyr143 of human S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase renders the enzyme thermosensitive and affects the oxidation state of bound cofactor nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide. Biochem J. 2006 Dec 1;400(2):245-53. [CrossRef]

- Honzík T, Magner M, Krijt J, Sokolová J, Vugrek O, Belužić R, Barić I, Hansíkova H, Elleder M, Veselá K, Bauerová L, Ondrušková N, Ješina P, Zeman J, Kožich V. Clinical picture of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency resembles phosphomannomutase 2 deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2012 Nov;107(3):611-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo X, Xiao Y, Song F, Yang Y, Xia M, Ling W. Increased plasma S-adenosyl-homocysteine levels induce the proliferation and migration of VSMCs through an oxidative stress-ERK1/2 pathway in apoE(-/-) mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2012 Jul 15;95(2):241-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzek A, Knežević J, Switzeny OJ, Cooper A, Barić I, Beluzić R, Strauss KA, Puffenberger EG, Mudd SH, Vugrek O, Zechner U. Abnormal Hypermethylation at Imprinting Control Regions in Patients with S-Adenosylhomocysteine Hydrolase (AHCY) Deficiency. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 14;11(3):e0151261. [CrossRef]

- Stender S, Chakrabarti RS, Xing C, Gotway G, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Adult-onset liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2015 Dec;116(4):269-74. [CrossRef]

- J.F. Leal, I. J.F. Leal, I. Ferrer, C. Blanco-Aparicio, J. Hernández-Losa, S. Ramón y Cajal, A. Carnero, M.E. LLeonart. "S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase downregulation contributes to tumorigenesis." Carcinogenesis, Volume 29, Issue 11, 08, Pages 2089-2095. 20 November. [CrossRef]

- Anastas JN, Moon RT. Wnt signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013 Jan;13(1):11-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atcha FA, Syed A, Wu B, Hoverter NP, Yokoyama NN, Ting JH, Munguia JE, Mangalam HJ, Marsh JL, Waterman ML. A unique DNA binding domain converts T-cell factors into strong Wnt effectors. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Dec;27(23):8352-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovanes K, Li TW, Munguia JE, Truong T, Milovanovic T, Lawrence Marsh J, Holcombe RF, Waterman ML. Beta-catenin-sensitive isoforms of lymphoid enhancer factor-1 are selectively expressed in colon cancer. Nat Genet. 2001 May;28(1):53-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998 Sep 4;281(5382):1509-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 ;96(10):5522-7. 11 May. [CrossRef]

- Huang C, Qin D. Role of Lef1 in sustaining self-renewal in mouse embryonic stem cells. J Genet Genomics. 2010 Jul;37(7):441-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim CG, Chung IY, Lim Y, Lee YH, Shin SY. A Tcf/Lef element within the enhancer region of the human NANOG gene plays a role in promoter activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011 Jul 8;410(3):637-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005 Apr 14;434(7035):843-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger ME, Sims AH, Coats ER, Clarke RB, Briegel KJ. The embryonic transcription cofactor LBH is a direct target of the Wnt signaling pathway in epithelial development and in aggressive basal subtype breast cancers. Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Sep;30(17):4267-79. [CrossRef]

- Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Newman JJ, Kagey MH, Young RA. Tcf3 is an integral component of the core regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2008 Mar 15;22(6):746-55. [CrossRef]

- Filali M, Cheng N, Abbott D, Leontiev V, Engelhardt JF. Wnt-3A/beta-catenin signaling induces transcription from the LEF-1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2002 Sep 6;277(36):33398-410. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung HC, Kim K. Identification of MYCBP as a beta-catenin/LEF-1 target using DNA microarray analysis. Life Sci. 2005 Jul 29;77(11):1249-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabletz T, Jung A, Dag S, Hlubek F, Kirchner T. beta-catenin regulates the expression of the matrix metalloproteinase-7 in human colorectal cancer. Am J Pathol. 1999 Oct;155(4):1033-8. [CrossRef]

- Crawford HC, Fingleton BM, Rudolph-Owen LA, Goss KJ, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P, Matrisian LM. The metalloproteinase matrilysin is a target of beta-catenin transactivation in intestinal tumors. Oncogene. 1999 ;18(18):2883-91. 6 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling L, Nurcombe V, Cool SM. Wnt signaling controls the fate of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene. 2009 Mar 15;433(1-2):1-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, Gifford DK, Melton DA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005 Sep 23;122(6):947-56. [CrossRef]

- Hay DC, Sutherland L, Clark J, Burdon T. Oct-4 knockdown induces similar patterns of endoderm and trophoblast differentiation markers in human and mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22(2):225-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh Y, Matsumura I, Tanaka H, Ezoe S, Sugahara H, Mizuki M, Shibayama H, Ishiko E, Ishiko J, Nakajima K, Kanakura Y. Roles for c-Myc in self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jun 11;279(24):24986-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldin V, Lukas J, Marcote MJ, Pagano M, Draetta G. Cyclin D1 is a nuclear protein required for cell cycle progression in G1. Genes Dev. 1993 May;7(5):812-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998 Sep 4;281(5382):1509-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D'Amico M, Pestell R, Ben-Ze'ev A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 ;96(10):5522-7. 11 May. [CrossRef]

- Baek SH, Kioussi C, Briata P, Wang D, Nguyen HD, Ohgi KA, Glass CK, Wynshaw-Boris A, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG. Regulated subset of G1 growth-control genes in response to derepression by the Wnt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Mar 18;100(6):3245-50. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Zhang R, Liu J, Li M, Song C, Dovat S, Li J, Ge Z. Characterization of LEF1 High Expression and Novel Mutations in Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. PLoS One. 2015 ;10(5):e0125429. 5 May. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang L, Zhang M, Melamed J, Liu X, Reiter R, Wei J, Peng Y, Zou X, Pellicer A, Garabedian MJ, Ferrari A, Lee P. LEF1 in androgen-independent prostate cancer: regulation of androgen receptor expression, prostate cancer growth, and invasion. Cancer Res. 2009 Apr 15;69(8):3332-8. [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos K, Arseni N, Schessl C, Stadler CR, Rawat VP, Deshpande AJ, Heilmeier B, Hiddemann W, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Bohlander SK, Feuring-Buske M, Buske C. A novel role for Lef-1, a central transcription mediator of Wnt signaling, in leukemogenesis. J Exp Med. 2008 Mar 17;205(3):515-22. [CrossRef]

- Waterman, ML. Lymphoid enhancer factor/T cell factor expression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004 Jan-Jun;23(1-2):41-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton DN, Fornalik H, Neff T, Park SY, Bender D, DeGeest K, Liu X, Xie W, Meyerholz DK, Engelhardt JF, Goodheart MJ. The role of LEF1 in endometrial gland formation and carcinogenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40312. [CrossRef]

- Shelton DN, Fornalik H, Neff T, Park SY, Bender D, DeGeest K, Liu X, Xie W, Meyerholz DK, Engelhardt JF, Goodheart MJ. The role of LEF1 in endometrial gland formation and carcinogenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40312. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Zhang R, Liu J, Li M, Song C, Dovat S, Li J, Ge Z. Characterization of LEF1 High Expression and Novel Mutations in Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. PLoS One. 2015 ;10(5):e0125429. 5 May. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen DX, Chiang AC, Zhang XH, Kim JY, Kris MG, Ladanyi M, Gerald WL, Massagué J. Wnt/TCF signaling through LEF1 and HOXB9 mediates lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Cell. 2009 Jul 10;138(1):51-62. [CrossRef]

- Wang WJ, Yao Y, Jiang LL, Hu TH, Ma JQ, Ruan ZP, Tian T, Guo H, Wang SH, Nan KJ. Increased LEF1 expression and decreased Notch2 expression are strong predictors of poor outcomes in colorectal cancer patients. Dis Markers. 2013;35(5):395-405. [CrossRef]

- Lin AY, Chua MS, Choi YL, Yeh W, Kim YH, Azzi R, Adams GA, Sainani K, van de Rijn M, So SK, Pollack JR. Comparative profiling of primary colorectal carcinomas and liver metastases identifies LEF1 as a prognostic biomarker. PLoS One. 2011 Feb 24;6(2):e16636. [CrossRef]

- Lin AY, Chua MS, Choi YL, Yeh W, Kim YH, Azzi R, Adams GA, Sainani K, van de Rijn M, So SK, Pollack JR. Comparative profiling of primary colorectal carcinomas and liver metastases identifies LEF1 as a prognostic biomarker. PLoS One. 2011 Feb 24;6(2):e16636. [CrossRef]

- Wang WJ, Yao Y, Jiang LL, Hu TH, Ma JQ, Liao ZJ, Yao JT, Li DF, Wang SH, Nan KJ. Knockdown of lymphoid enhancer factor 1 inhibits colon cancer progression in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2013 Oct 2;8(10):e76596. [CrossRef]

- Kim K, Lu Z, Hay ED. Direct evidence for a role of beta-catenin/LEF-1 signaling pathway in induction of EMT. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26(5):463-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li TW, Ting JH, Yokoyama NN, Bernstein A, van de Wetering M, Waterman ML. Wnt activation and alternative promoter repression of LEF1 in colon cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2006 Jul;26(14):5284-99. [CrossRef]

- Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kühl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996 Aug 15;382(6592):638-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovanes K, Li TW, Munguia JE, Truong T, Milovanovic T, Lawrence Marsh J, Holcombe RF, Waterman ML. Beta-catenin-sensitive isoforms of lymphoid enhancer factor-1 are selectively expressed in colon cancer. Nat Genet. 2001 May;28(1):53-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama NN, Pate KT, Sprowl S, Waterman ML. A role for YY1 in repression of dominant negative LEF-1 expression in colon cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 Oct;38(19):6375-88. [CrossRef]

- Hao YH, Lafita-Navarro MC, Zacharias L, Borenstein-Auerbach N, Kim M, Barnes S, Kim J, Shay J, DeBerardinis RJ, Conacci-Sorrell M. Induction of LEF1 by MYC activates the Wnt pathway and maintains cell proliferation. Cell Commun Signal. 2019 Oct 17;17(1):129. [CrossRef]

- Schmeckpeper J, Verma A, Yin L, Beigi F, Zhang L, Payne A, Zhang Z, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ, Mirotsou M. Inhibition of Wnt6 by Sfrp2 regulates adult cardiac progenitor cell differentiation by differential modulation of Wnt pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015 Aug;85:215-25. [CrossRef]

- Zheng XL, Yu HG. Wnt6 contributes tumorigenesis and development of colon cancer via its effects on cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell-cycle and migration. Oncol Lett. 2018 Jul;16(1):1163-1172. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Wang C, Tong J, Su Y, Lin Y, Zhou X, Ye L. Wnt6 promotes the migration and differentiation of human dental pulp cells partly through c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathway. J Endod. 2014 Jul;40(7):943-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeckpeper J, Verma A, Yin L, Beigi F, Zhang L, Payne A, Zhang Z, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ, Mirotsou M. Inhibition of Wnt6 by Sfrp2 regulates adult cardiac progenitor cell differentiation by differential modulation of Wnt pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015 Aug;85:215-25. [CrossRef]

- Zheng XL, Yu HG. Wnt6 contributes tumorigenesis and development of colon cancer via its effects on cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell-cycle and migration. Oncol Lett. 2018 Jul;16(1):1163-1172. [CrossRef]

- Kas K, Voz ML, Hensen K, Meyen E, Van de Ven WJ. Transcriptional activation capacity of the novel PLAG family of zinc finger proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998 Sep 4;273(36):23026-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa T, Adachi Y, Fujisawa J, Kambe T, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Sasaki R, Kuwahara J, Ikehara S, Tokunaga R, Taketani S. Involvement of PLAGL2 in activation of iron deficient- and hypoxia-induced gene expression in mouse cell lines. Oncogene. 2001 Aug 2;20(34):4718-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wezensky SJ, Hanks TS, Wilkison MJ, Ammons MC, Siemsen DW, Gauss KA. Modulation of PLAGL2 transactivation by positive cofactor 2 (PC2), a component of the ARC/Mediator complex. Gene. 2010 Feb 15;452(1):22-34. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Li D, Du Y, Su C, Yang C, Lin C, Li X, Hu G. Overexpressed PLAGL2 transcriptionally activates Wnt6 and promotes cancer development in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2019 Feb;41(2):875-884. [CrossRef]

- Knoepfler PS, Zhang XY, Cheng PF, Gafken PR, McMahon SB, Eisenman RN. Myc influences global chromatin structure. EMBO J. 2006 Jun 21;25(12):2723-34. [CrossRef]

- Ma J, Zhao J, Lu J, Wang P, Feng H, Zong Y, Ou B, Zheng M, Lu A. Cadherin-12 enhances proliferation in colorectal cancer cells and increases progression by promoting EMT. Tumour Biol. 2016 Jul;37(7):9077-88. [CrossRef]

- Ofori-Acquah SF, King JA. Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule: a new paradox in cancer. Transl Res. 2008 Mar;151(3):122-8. [CrossRef]

- Degen, W. G. , & van Kempen, L. C. (2002). ALCAM: shedding light on the role of CD166 in normal and pathological cell processes. Tissue Antigens, 60(2), 89-98.

- Kuświk, M. , Bieńkowski, M., & Jankowska-Steifer, E. (2021). ALCAM (CD166) in Cancer Biology: More Than Just a Cell Adhesion Molecule. Cancers, 13(11). Hansen AG, Swart GW, Zijlstra A. ALCAM: Basis Sequence: Mouse. AFCS Nat Mol Pages. 2011;2011:10.1038/mp.a004126.01. [CrossRef]

- Villarejo A, Cortés-Cabrera A, Molina-Ortíz P, Portillo F, Cano A. Differential role of Snail1 and Snail2 zinc fingers in E-cadherin repression and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2014 Jan 10;289(2):930-41. [CrossRef]

- Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-beta signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2001 Oct;29(2):117-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hocevar BA, Mou F, Rennolds JL, Morris SM, Cooper JA, Howe PH. Regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway by disabled-2 (Dab2). EMBO J. 2003 Jun 16;22(12):3084-94. [CrossRef]

- Morrissey C, Brown LG, Pitts TE, Vessella RL, Corey E. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 is expressed in prostate cancer metastases and its effects on prostate tumor cells depend on cell phenotype and the tumor microenvironment. Neoplasia. 2010 Feb;12(2):192-205. [CrossRef]

- Fukumura D, Kashiwagi S, Jain RK. The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006 Jul;6(7):521-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artigiani S, Conrotto P, Fazzari P, Gilestro GF, Barberis D, Giordano S, Comoglio PM, Tamagnone L. Plexin-B3 is a functional receptor for semaphorin 5A. EMBO Rep. 2004 Jul;5(7):710-4. [CrossRef]

- Zhao GX, Xu YY, Weng SQ, Zhang S, Chen Y, Shen XZ, Dong L, Chen S. CAPS1 promotes colorectal cancer metastasis via Snail mediated epithelial mesenchymal transformation. Oncogene. 2019 Jun;38(23):4574-4589. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowell CF, Yan IK, Eiseler T, Leightner AC, Döppler H, Storz P. Loss of cell-cell contacts induces NF-kappaB via RhoA-mediated activation of protein kinase D1. J Cell Biochem. 2009 Mar 1;106(4):714-28. [CrossRef]

- Westhoff MA, Serrels B, Fincham VJ, Frame MC, Carragher NO. SRC-mediated phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase couples actin and adhesion dynamics to survival signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2004 Sep;24(18):8113-33. [CrossRef]

- Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig A. Wnt signalling and the control of cellular metabolism. Biochem J. 2010 Mar 15;427(1):1-17. [CrossRef]

- Tada M, Kai M. Noncanonical Wnt/PCP signaling during vertebrate gastrulation. Zebrafish. 2009;6(1):29–40.

- Goldsmith ZG, Dhanasekaran DN. G protein regulation of MAPK networks. Oncogene. 2007 ;26(22):3122-42. 14 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemm von Hohenberg K, Müller S, Schleich S, Meister M, Bohlen J, Hofmann TG, Teleman AA. Cyclin B/CDK1 and Cyclin A/CDK2 phosphorylate DENR to promote mitotic protein translation and faithful cell division. Nat Commun. 2022 Feb 3;13(1):668. [CrossRef]

- Harbour JW, Dean DC. The Rb/E2F pathway: expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev. 2000 Oct 1;14(19):2393-409. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- rimm D, Bauer J, Wise P, Krüger M, Simonsen U, Wehland M, Infanger M, Corydon TJ. The role of SOX family members in solid tumours and metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020 Dec;67(Pt 1):122-153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoepfler PS, Zhang XY, Cheng PF, Gafken PR, McMahon SB, Eisenman RN. Myc influences global chromatin structure. EMBO J. 2006 Jun 21;25(12):2723-34. [CrossRef]

- Thiery JP, Sleeman JP. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006 Feb;7(2):131-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hocevar BA, Mou F, Rennolds JL, Morris SM, Cooper JA, Howe PH. Regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway by disabled-2 (Dab2). EMBO J. 2003 Jun 16;22(12):3084-94. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson-Rosenthal C, Millar JB. Cdc25: mechanisms of checkpoint inhibition and recovery. Trends Cell Biol. 2006 Jun;16(6):285-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Zhu C, Tang L, Chen Q, Guan N, Xu K, Guan X. MYC dysfunction modulates stemness and tumorigenesis in breast cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2021 Jan 1;17(1):178-187. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Wang J, Wu W, Gao H, Liu N, Zhan G, Li L, Han L, Guo X. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote epithelial ovarian cancer cell stemness by inducing the CSF2/p-STAT3 signalling pathway. FEBS J. 2020 Dec;287(23):5218-5235. [CrossRef]

- 88. Payapilly A, Guilbert R, Descamps T, White G, Magee P, Zhou C, Kerr A, Simpson KL, Blackhall F, Dive C, Malliri A. TIAM1-RAC1 promote small-cell lung cancer cell survival through antagonizing Nur77-induced BCL2 conformational change. Cell Rep. 2021 Nov 9;37(6):109979. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Huang G, Wei J, Cao H, Jiang G. ALKBH5 inhibits thyroid cancer progression by promoting ferroptosis through TIAM1-Nrf2/HO-1 axis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2023 Apr;478(4):729-741. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | p-value range | Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular movement | 6.00E-04-2.48E-13 | 73 |

| Cell death and survival | 6.18E-04-2.31E-08 | 66 |

| Cellular development | 5.77E-04-2.45E-07 | 76 |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | 5.77e-04-2.45E-07 | 70 |

| Cell morphology | 4.14E-04-3.07E-07 | 48 |

| Name | p-value range | Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular movement | 2.11E-12-5.74E-41 | 523 |

| Cell death and survival Cellular functions and maintenance Cellular growth and proliferation |

3.76E-13-8.59E-28 | 553 |

| 2.30E-12-1.96E-25 | 520 | |

| 1.51E-8.38E-23 | 605 | |

| 1.11E-04-8.38E-23 | 600 |

| Symbol | Expr Log Ratio | q-value | Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDH12 | -11,706 | 6,97E-13 | Other |

| HNF1A | -13,408 | 3,71E-17 | Transcription regulator |

| MAP2K6 | -6,754 | 2,01E-39 | kinase |

| TCF4 | -3,915 | 0,00245 | Transcription regulator |

| Symbol | Expr Log Ratio | q-value | Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| APC2 | 3,428 | 0,0135 | Enzyme |

| CDH12 | -11,706 | 6,97E-13 | other |

| DKK1 | -3,416 | 0,0000255 | Growth factor |

| DKK3 | 3,316 | 5,54E-08 | Cytokine |

| DKK4 | -3,791 | 1,81E-08 | Other |

| FZD7 | 4,134 | 5,66E-20 | G-protein coupled receptor |

| GJA1 | -5,544 | 0,00000566 | Transporter |

| HNF1A | -13,408 | 3,71E-17 | Transcription regulator |

| POU5F1 | -5,964 | 0,00976 | Transcription regulator |

| RARB | -7,753 | 0,001 | Nuclear receptor |

| SFRP5 | 3,362 | 5,03E-12 | Transmembrane receptor |

| SOX5 | -8,898 | 0,00000315 | Transcription regulator |

| SOX6 | -3,842 | 0,00000333 | Transcription regulator |

| TCF4 | -3,915 | 0,00245 | Transcription regulator |

| TLE1 | 4,455 | 4,53E-11 | Transcription regulator |

| TLE4 | 4,145 | 2,28E-25 | Transcription regulator |

| WNT6 | 4,078 | 1,28E-21 | other |

| From Molecule(s) | Relationship Type | To Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| 14-3-3 | protein-protein interactions | YAP1 |

| AFDN | causation | Recruitment of actin cytoskeleton |

| AKT | causation | Cell proliferation |

| AKT | causation | TC proliferation |

| ARHGAP35 | inhibition | RHOA |

| ARHGEF17 | activation | RHOA |

| α-catenin | activation | Central spindlin |

| α-catenin | activation | NF2 |

| α-catenin | activation | VCL |

| α-catenin | causation | AJ organization |

| α-catenin | causation | Recruitment of actin cytoskeleton |

| α-catenin | inhibition | PP2A |

| α-catenin | protein-protein interactions | 14-3-3 |

| α-catenin | protein-protein interactions | NF2 |

| α-catenin | protein-protein interactions | VCL |

| Ampk | activation | RHOA |

| Arp2-3 | causation | Actin polymerization |

| Arp2-3 | membership | ACTR2 |

| Arp2-3 | membership | ACTR3 |

| BAIAP2 | activation | WAS |

| BAIAP2 | activation | WASF1 |

| BAIAP2 | protein-protein interactions | WASF1 |

| CDC42 | activation | BAIAP2 |

| CDC42 | activation | PAK |

| CDC42 | activation | WAS |

| CDC42 | inhibition | IQGAP1 |

| CDC42 | protein-protein interactions | IQGAP1 |

| CDH1 | activation | RAPGEF1 |

| CDH1 | activation | STK11 |

| CDH1 | causation | Cell adhesion |

| CDH1 | inhibition | EGFR |

| CDH1 | inhibition | IGF1R |

| CDH1 | inhibition | MET |

| CDH1 | protein-protein interactions | RAPGEF1 |

| CDH2 | activation | PRKAA1 |

| CDH2 | protein-protein interactions | CDH2 |

| CDH2 | protein-protein interactions | CTNNB1 |

| CDH2 | protein-protein interactions | PRKAA1 |

| CRK | activation | RAPGEF1 |

| CTNNB1 | activation | α-catenin |

| CTNNB1 | activation | CDH1 |

| CTNNB1 | activation | MAGI1 |

| CTNNB1 | activation | MAGI2 |

| CTNNB1 | activation | NF2 |

| CTNNB1 | activation | TNS1 |

| CTNNB1 | molecular cleavage | CDH1 |

| CTNNB1 | protein-protein interactions | α-catenin |

| CTNNB1 | protein-protein interactions | CDH1 |

| CTNNB1 | protein-protein interactions | MAGI1 |

| CTNNB1 | protein-protein interactions | MAGI2 |

| CTNNB1 | protein-protein interactions | TNS1 |

| CTNNB1 | reaction | α-catenin, FER |

| CTNNB1 | reaction | α-catenin, FYN |

| CTNNB1 | reaction | CTNNB1, EGFR; MET |

| CTNNB1 | reaction | MAGI2, VCL |

| CTNND1 | activation | CDH1 |

| CTNND1 | molecular cleavage | CDH1 |

| CTNND1 | protein-protein interactions | CDH1 |

| CTNND1 | protein-protein interactions | RHOA |

| CTNND1 | reaction | CTNND1, CDH1 |

| CTNND1 | reaction | CTNND1, NANOS1 |

| CTNND1 | translocation | CTNND1 |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | activation | ARHGEF17 |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | activation | TIAM1 |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | causation | Cell adhesion |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | causation | Cell-cell contact formation |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | membership | CDH1 |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | membership | CDH2 |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | membership | CTNNB1 |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | membership | CTNND1 |

| CTNN,β-CDHE/N | protein-protein interactions | CDH1 |

| Ca2+ | activation | CDH1 |

| Ca2+ | chemical-protein interactions | CDH1 |

| Central spindlin | activation | ECT2 |

| Central spindlin | inhibition | ARHGAP35 |

| Cofilin | causation | Stabilization of actin network |

| DIAPH1 | causation | Stress fiber formation |

| DLL1 | activation | NOTCH |

| ECT2 | activation | RHOA |

| EGF | activation | EGFR |

| EGFR | activation | FER |

| EGFR | activation | FYN |

| EGFR | activation | RAS |

| EGFR | causation | Epithelial barrier disruption |

| EGFR | causation | Proliferation of cell |

| EGFR | inhibition | CTNND1 |

| EGFR | phosphorylation | CTNND1 |

| EGFR | phosphorylation | FER |

| EGFR | phosphorylation | FYN |

| FARP2 | activation | CDC42 |

| FGF1 | activation | FGFR1 |

| FGFR1 | activation | RAS |

| HGF | activation | MET |

| IGF1R | causation | Proliferation of cell |

| IQGAP1 | inhibition | CTNNB1 |

| IQGAP1 | protein-protein interactions | CTNNB1 |

| LATS | inhibition | YAP1 |

| LIMK | inhibition | Cofilin |

| LIMK | phosphorylation | Cofilin |

| LPS | causation | Endothelial barrier function |

| MAGI1 | activation | DLL1 |

| MAGI1 | protein-protein interactions | DLL1 |

| MAGI2 | activation | PTEN |

| MAGI2 | molecular cleavage | PTEN |

| MAGI2 | protein-protein interactions | PTEN |

| MER-WWC1-FRMD6 | activation | MST/KRS |

| MER-WWC1-FRMD6 membership | membership | NF2 |

| MET | activation | RAS |

| MET | causation | Proliferation of cell |

| MET | inhibition | CDH1 |

| MET | phosphorylation | CDH1 |

| MST/KRS | activation | LATS |

| Myosin2 | causation | AJ stabilization |

| Myosin | causation | Cell adhesion structure clustering |

| NF2 | inhibition | EGFR |

| NOTCH | causation | Neuron differentiation |

| Nectin | activation | AFDN |

| Nectin | activation | SRC |

| Nectin | causation | Cell adhesion |

| Nectin | protein-protein interactions | AFDN |

| Nectin | protein-protein interactions | Nectin |

| Nectin | protein-protein interactions | SRC |

| PAK | activation | LIMK |

| PAK | phosphorylation | LIMK |

| PIP2 | inhibition | AKT |

| PIP3 | reaction | PIP2 PTEN |

| PRKAA1 | causation | Endothelia barrier function |

| RAC1 | activation | BAIAP2 |

| RAC1 | activation | PAK |

| RAC1 | activation | WASF1 |

| RAC1 | inhibition | IQGAP1 |

| RAC1 | protein-protein interactions | IQGAP1 |

| RAP1 | activation | CTNND1 |

| RAP1 | activation | FARP2 |

| RAPGEF1 | activation | RAP1 |

| RAS | expression | SNAI1 |

| RAS | expression | SNAI2 |

| RHOA | activation | DIAPH1 |

| RHOA | activation | Myosin2 |

| RHOA | activation | ROCK |

| ROCK | activation | LIMK |

| ROCK | phosphorylation | LIMK |

| SNAI1 | expression | CDH1 |

| SNAI2 | expression | CDH1 |

| SRC | activation | CRK |

| SRC | activation | FARP2 |

| SRC | activation | VAV2 |

| SRC | phosphorylation | FARP2 |

| SRC | phosphorylation | VAV2 |

| STK11 | activation | Ampk |

| STK11 | phosphorylation | Ampk |

| TCF/LEF | causation | Cell differentiation |

| TCF/LEF | causation | Cell proliferation |

| TGFB2 | activation | TGFBR |

| TGFBR | expression | SNAI1 |

| TIAM1 | activation | RAC1 |

| TNS1 | causation | Recruitment of actin cytoskeleton |

| VAV2 | activation | CDC42 |

| VAV2 | activation | RAC1 |

| WAS | activation | Arp2-3 |

| WASF1 | activation | Arp2-3 |

| YAP1 | reaction | YAP1 LATS |

| YAP1 | reaction | YAP1 PP2A |

| ZBTB33 | inhibition | TCF/LEF |

| Symbol | Expr Log Ratio | q-value | Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSF2 | -4,435 | 7,37E-13 | Cytokine |

| CXCLR8 | -3,762 | 6,67E-10 | Cytokine |

| CXCR4 | 3,8 | 2,03E-25 | G-protein coupled receptor |

| FGF21 | -3,51 | 0,00409 | Growth factor |

| IL10 | 4,254 | 4,4E-14 | Cytokine |

| MMP16 | -6,32 | 0,00443 | Peptidase |

| MMP17 | -3,808 | 9,57E-09 | Peptidase |

| MMP19 | 3,196 | 0,00133 | Peptidase |

| MMP24 | 3,114 | 9,03E-07 | Peptidase |

| NOS2 | 3,881 | 1,34E-19 | Enzyme |

| PDGFC | -3,482 | 1,34E-06 | Growth factor |

| PIK3R5 | 4,778 | 0,015 | Kinase |

| PLAU | 3,487 | 6,53E-11 | Peptidase |

| SLC2A3 | 3,254 | 1,67E-12 | Transporter |

| TIAM1 | 3,836 | 5,84E-27 | Other |

| From Molecule(s) | Relationship Type | To Molecules(s) |

|---|---|---|

| BCL2 | Causation | Anti-Apoptosis |

| BCR-ABL1 | activation | STAT3 |

| CDKN1A | Inhibition | Stat3-Stat3 |

| Cytokine | activation | Cytokinereceptor |

| Cytokine | protein-protein interactions | Cytokinereceptor |

| Cytokinereceptor | activation | JAK2 |

| Cytokinereceptor | activation | SRC |

| Cytokinereceptor | activation | TYK2 |

| Cytokinereceptor | protein-protein interactions | JAK2 |

| Cytokinereceptor | protein-protein interactions | TYK2 |

| ERK1/2 | activation | JAK2 |

| ERK1/2 | translocation | TYK2 |

| Growthfactor | chemical-protein interactions | Stat3-stat3 |

| Growthfactor | activation | ERK 1/2 |

| Growthfactor receptor | protein-protein interaction | RAS |

| Growthfactor receptor | activation | Growthfactor receptor |

| Growthfactor receptor | activation | Growth factor receptor |

| Growthfactor receptor | protein-protein interaction | JAK2 |

| JAK2 | protein-protein interaction | SRC |

| JAK2 | activation | JAK2 |

| JNK | reaction | SRC |

| MAP2K1/2 | activation | STAT3 |

| MLK | activation | STAT3 |

| MYC | activation | Stat3-Stat3 |

| Mapkkinase | activation | ERK ½ |

| Mapkkinase | activation | Mapkkinase |

| NDUFA13 | activation | CDC25A |

| P38MAPK | activation | JNK |

| PIAS3 | protein.protein interactions | P38MAPK |

| PIAS3 | activation | STAT3 |

| PIM1 | inhibition | Stat3-stat3 |

| PTPN2 | protein-protein interactions | Stat3-stat3 |

| PTPN6 | activation | Stat3-stat3 |

| RAC1 | inhibition | BCL2 |

| RAF1 | inhibition | Stat3-stat3 |

| RAS | activation | JAK2 |

| RAS | activation | MLK |

| SOCS | activation | MAP2K1/2 |

| SRC | activation | RAC1 |

| SRC | inhibition | RAF1 |

| STAT3 | activation | JAK2 |

| STAT3 | activation | RAS |

| Stat3-stat3 | reaction | STAT3 |

| Stat3-stat3 | translocation | Stat3-stat3 |

| Stat3-stat3 | activation | STAT3 |

| Stat3-stat3 | activation | CDKN1A |

| Stat3-stat3 | activation | MYC |

| Stat3-stat3 | causation | PIM1 |

| TYK2 | membership | Transcription |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).