1. Introduction

Recently, cases of personal information infringement accidents and DDoS attacks that steal personal information after infecting the user's PC by distributing malicious codes to Internet users are increasing. Hackers have been exploiting security vulnerabilities such as cross-site scripts, SQL injections, and security configuration errors to steal personal information.

Among the various channels for distributing malicious code, the number of cases of distributing malicious code using vulnerabilities in websites and user PCs continues to increase. The homepage, which can infect a user's PC with malicious code, is divided into a distribution site that directly hides the malicious code and a hidden stopover so that it can be automatically connected to the distribution site. After opening a malicious code distribution site, the attacker hacked the website of the destination and inserted the distribution site URL to infect the malicious code by inducing the visitor to access the destination to the distribution site without knowing. Detection of stopovers is becoming increasingly difficult because they mainly target websites with high user visits, such as portals, blogs, and bulletin boards, and obfuscate and conceal malicious code within the stopover hacked by the attacker [

1]. As a result, there is an increasing de-mand for measuring the security threat of websites. Static and dynamic analysis of website security risks is generally used to analyze website security risks [

2]. Similar hash-based website security risk analysis and Machine Learning-based website security measurement methods have recently been proposed [

3]. Additionally, website security measurement technology mainly aims at inspection speed, zero-day malicious code analysis possibility, and accuracy of analysis results.

In this study, a method was proposed to collect and measure information disclosed on the Internet to measure the risk of a website. DNS information, IP information, and website history information are re-quired to measure the risk of a website. The website history information can be checked for global traffic rankings, malicious code distribution history, and HTTP access status. In addition, public information col-lection on a website can be used to measure the security risk of a website. Existing cybersecurity intelligence analysis utilizes commercial services from antivirus companies. However, in this study, we conducted a study to measure cyberthreats by collecting only OSINT information for public purposes.

2. Related research

The main method of measuring website security threats is reputation research based on the record of previous security incident's logs. In addition, it is classified into dynamic checks that check malware by accessing the user's terminal environment and static checks that check malware detection patterns.

The main goals of website security measurement technology are inspection speed, zero-day malicious code analysis possibility, and accuracy of analysis results.

2.1. Static analysis of website security risks

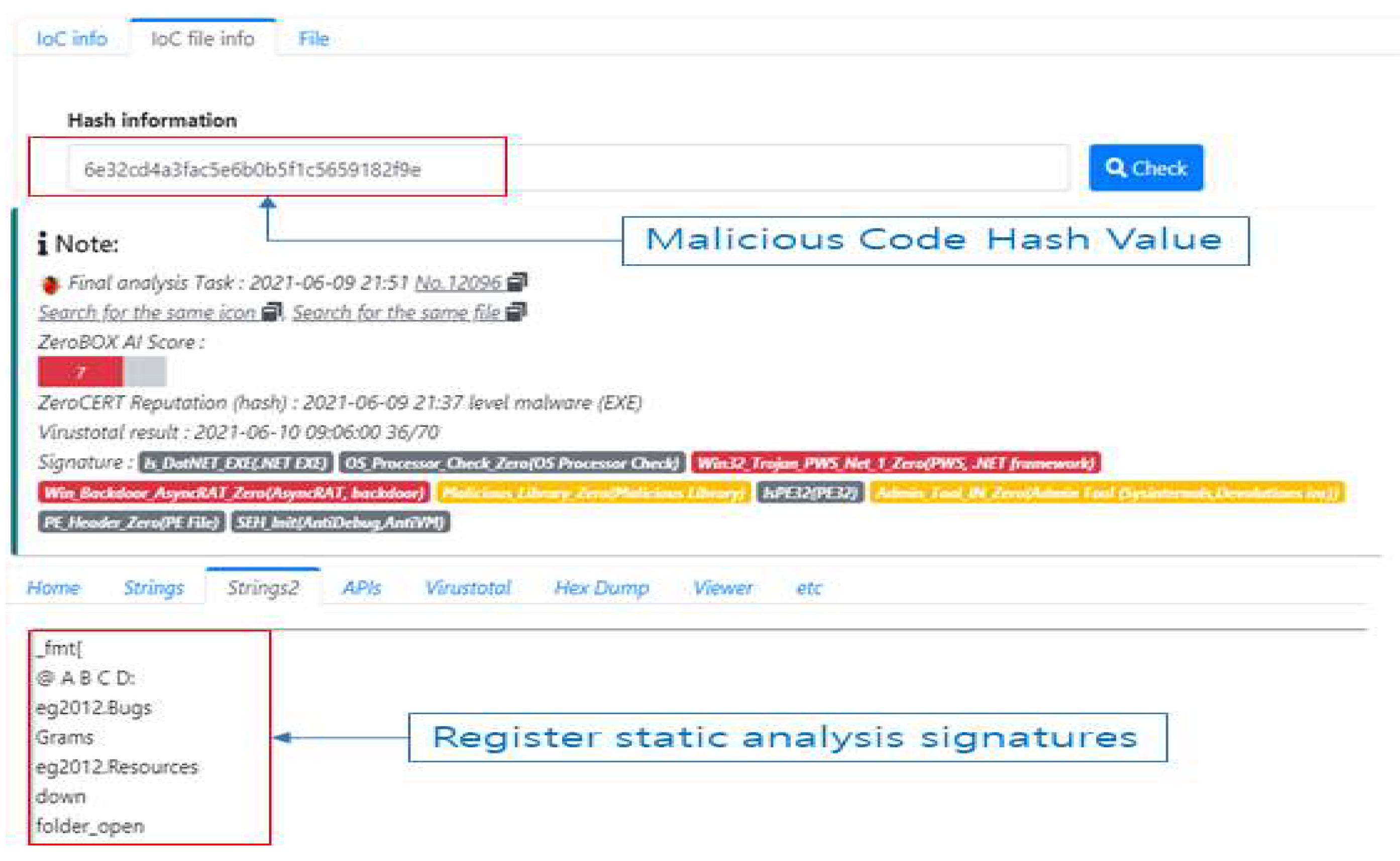

There is a static analysis method for source code to check malicious code hidden on the website. Since the malicious code hidden on the website is obfuscated, it is decoded and checked [

4]. As shown in

Figure 1, the inspection method converts malicious codes previously distributed on the website into signatures and registers them as detection patterns. Then, the website to be analyzed is collected by crawling, and the source is checked on the website with the registered signature. The characteristic of this analysis is that it has a faster inspection time than other analysis methods, so it is efficient to detect a large number of in-spection targets in a short time [

5].

2.2. Dynamic Analysis of Website Security Risk

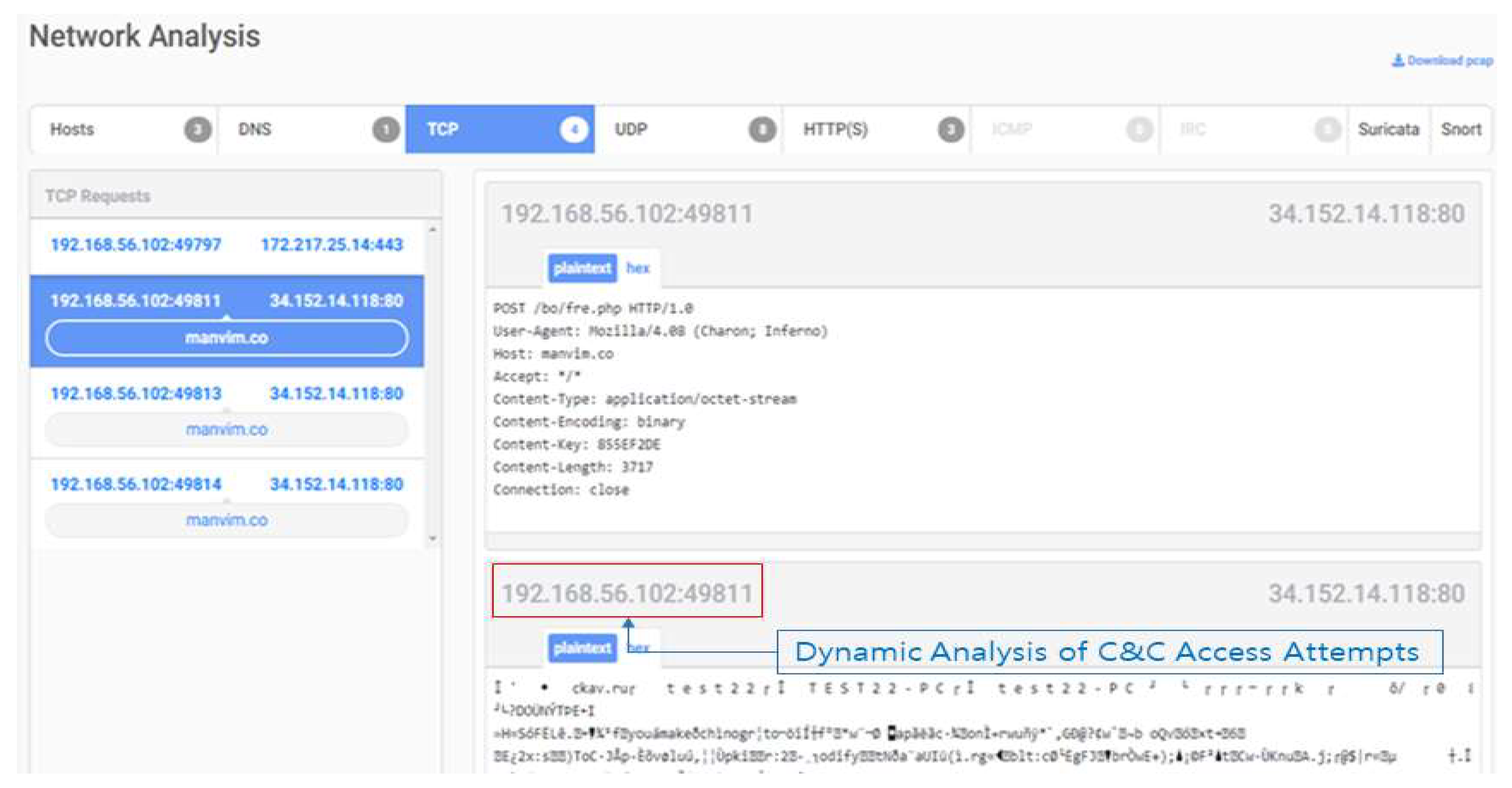

Dynamic analysis is a method of analyzing behavior on a PC by executing malicious code and analyzing it on the same virtual machine as the user's PC. For detection, access the website and download malicious code [

6]. Detects abnormal behavior such as creating additional files, changing the registry, and attempting to connect to a network on a virtual PC. As shown in [

Figure 2], it is possible to collect malicious code downloaded from the website and information on command control servers (C&C, Command & Control). Dynamic analysis has the advantage of analyzing zero-day malicious codes that are difficult to detect with static analysis. However, the inspection speed takes a long time [

7].

2.3. Analysis of website security risk based on similarity hash

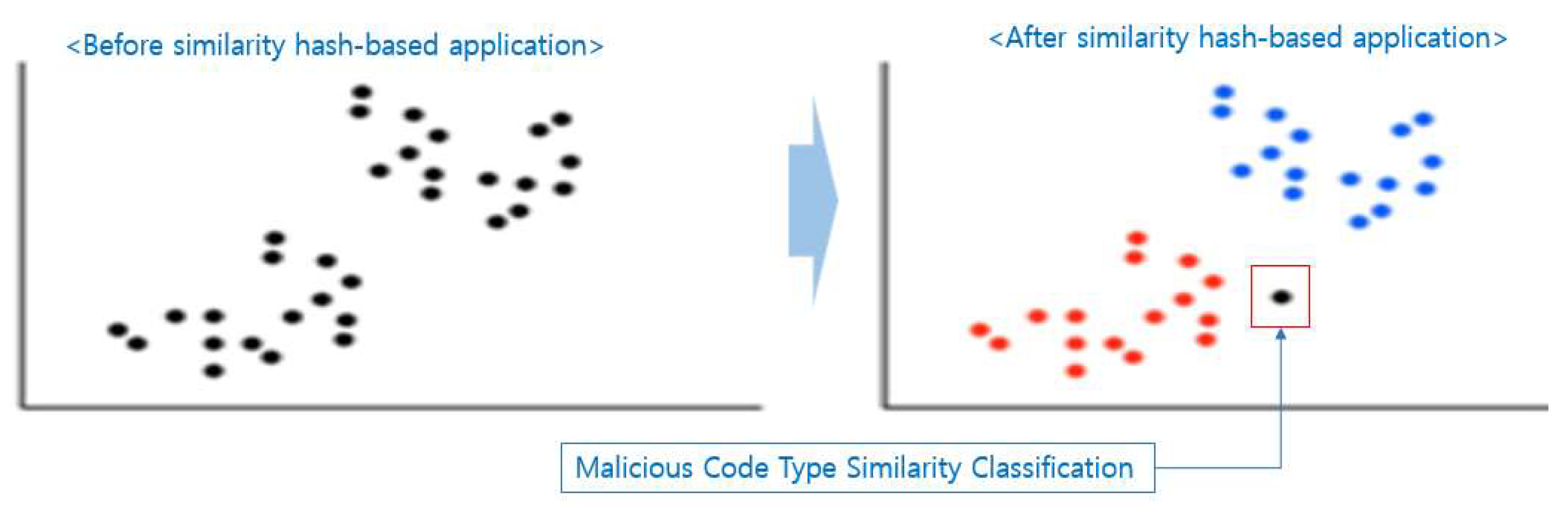

A similarity hash method may be applied between hidden malicious codes of a website. As shown in [

Figure 3], generating hash codes for malicious codes with similar hash values can compare the degree of similarity of files by deriving similarity values such as Euclidean distance measurement [

8]. Similarity hash functions are applied to many malicious codes, and K-NN's method is used to classify whether they are malicious or not. K-NN classifies malicious code types classified as K into the closest type by applying similarity hash codes [

9].

2.4. Machine Learning (ML)-based website security threat analysis

Attackers are evolving by continuously seeking ways to avoid detection techniques because they are aware of the website's security threat detection system. Therefore, security experts in charge of detection have limitations in responding to attackers evolving into existing detection systems [

10]. Accordingly, to detect security threats, many websites are responding through machine learning (ML).

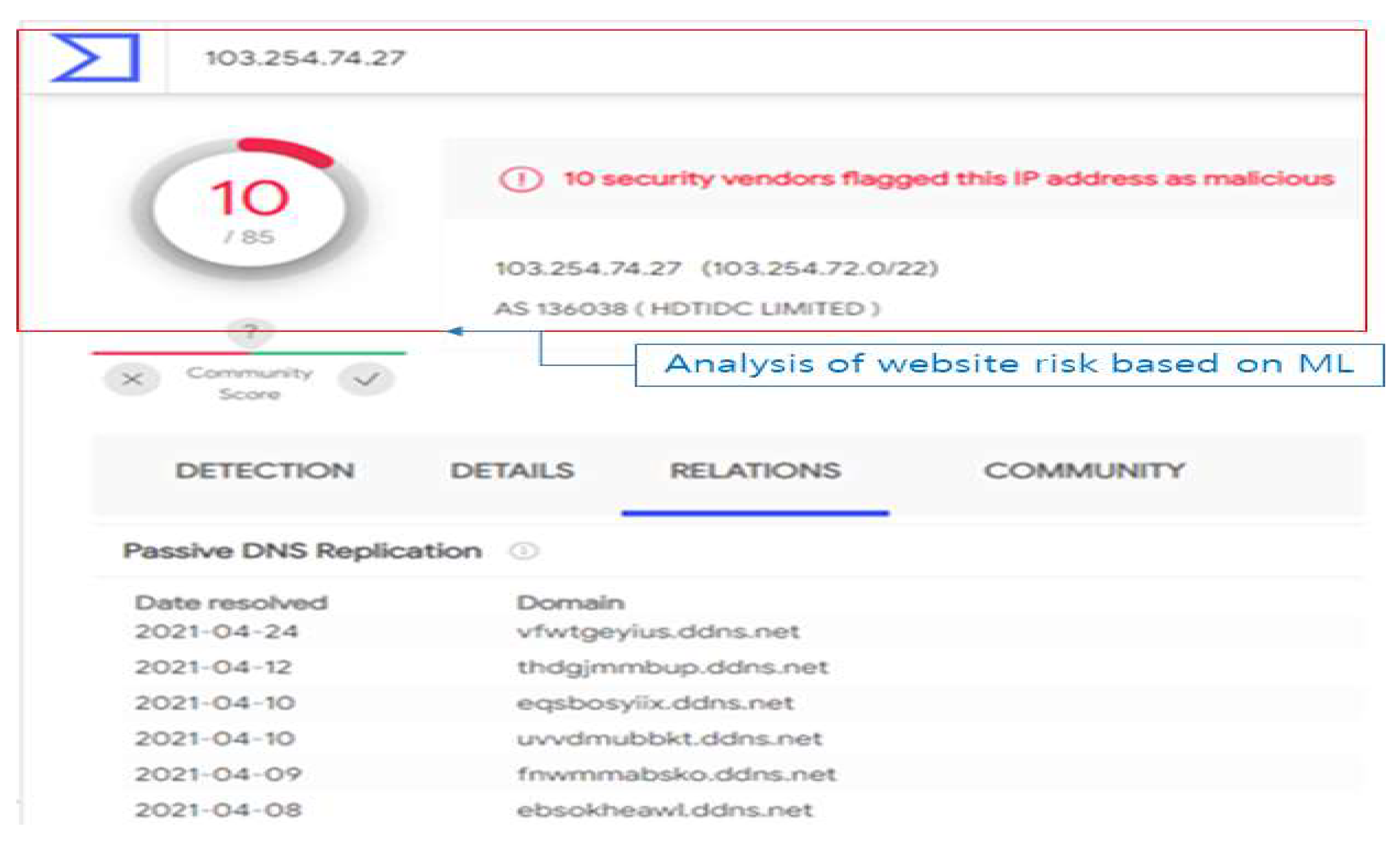

The detection system using ML learns the executable file for the PE (Portable Executable) structure in the form of EXE and DLL [

11]. The PE structure is the file structure of the executable downloaded from the website, which can also be checked for similarities to malware. Additionally, it learns non-executable (Non-PE) structures such as standard document files and scripts. As shown in [

Figure 4], this analysis checks the similarity of files hidden on the website to be inspected for maliciousness. For example, when checking the website IP registered on Google Virus Total, it can be seen that more than 30 phishing domains are registered [

12].

In the same way, most of the methods for measuring security threats on a website are building a DB by crawling website source files and collecting executable files distributed on the website, which are presented in <

Table 1>. The static analysis method registers malicious code patterns and then collects and checks website sources through web crawling. It has the advantage of being fast because it checks patterns. However, it has the disadvantage of being unable to detect non-registered zero-day malware. In addition, the accuracy is very good with registered pattern searches. Dynamic analysis connects the website to the virtualized PC environment to determine whether it is dangerous through abnormal behavior analysis. The inspection technology uses a virtualized PC, which takes some time for risk behavior analysis. It can detect even zero-day malicious codes through behavioral analysis and has excellent accuracy. Similarity hash analysis technology configures a dataset for each type of malicious code to determine similarity hash values and similarity to files collected from the website. The inspection technology is a similarity hash technology for malicious codes, and the inspection speed is high. Zero-day detection is also possible, but the accuracy is moderate. ML learning analysis constructs malicious code and standard file datasets to predict the risk of files collected on the website after performing ML learning. The inspection technology is ML learning for malicious and standard code, and the inspection speed is high. Zero-day detection is possible, and accuracy is excellent, depending on the amount of learning.

3. Suggested method of website risk information collection

This study proposes collecting information disclosed online to measure website risk. In order to measure the risk of a website, DNS information, IP information, and website history information are required. The website history information may be based on global traffic ranking, malicious code distribution history, and HTTP access status. This study proposed a three-step plan to collect the published website risk information.

3.1. Technique of web Site risk information collection

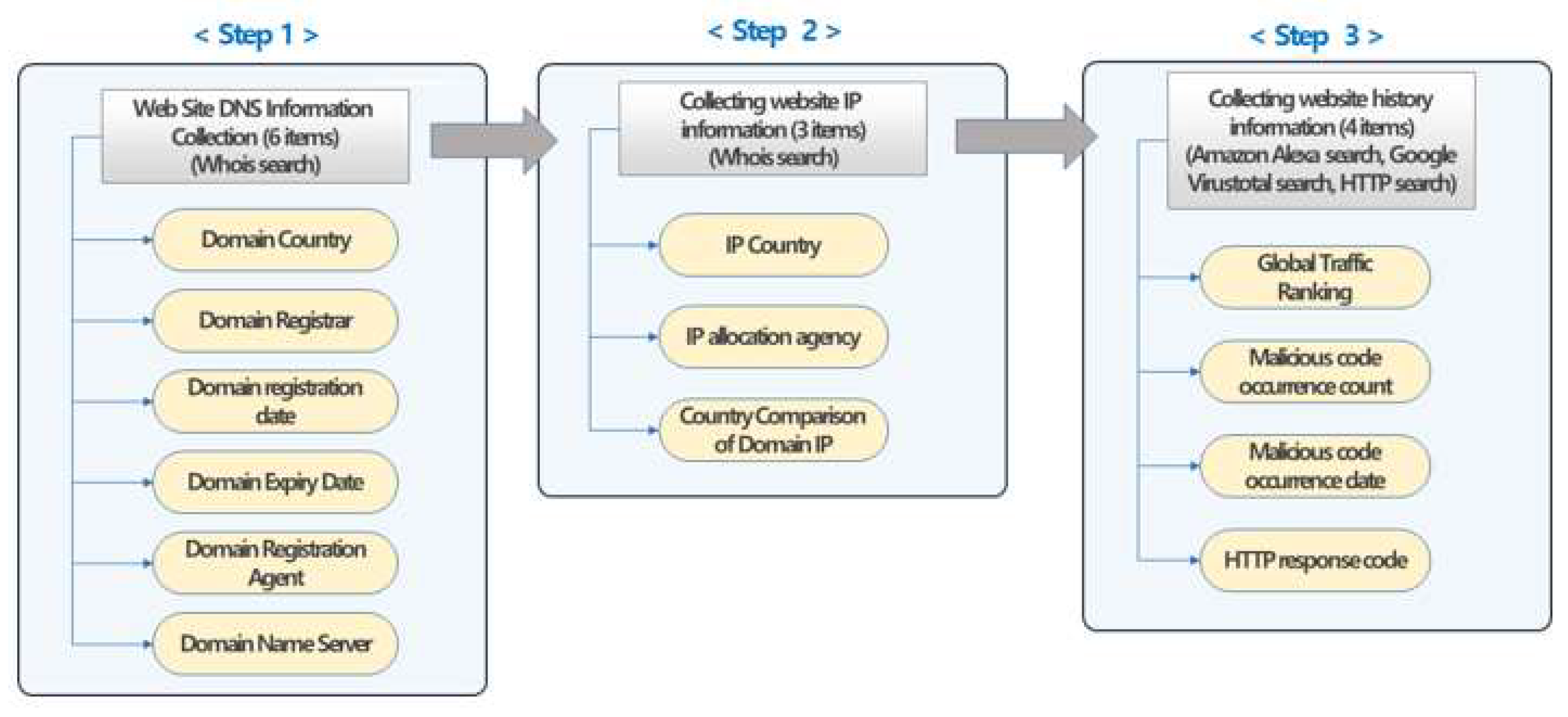

A method for collecting public information for measuring the risk of malicious code is presented as follows. As shown in [

Figure 5], risk measurement information for the website can be collected through the website DNS information after inquiring Whois in step 1. Then, in step 2, website IP information can be collected through Whois inquiry. The third step is to collect website history information, which can collect Amazon Alexa inquiries, Google Virustotal, and HTTP response codes.

3.2. Technique Analyze of website risk information collection

Table 2 shows that the website risk information collection can collect 13 items. Through DNS information, it can check the risk of the website according to the country, registrant, registration date, end date, and registered agent information. It is essential whether the IP country, IP allocation agency, DNS country, and IP country are the same through IP information. Among the website history information, if the global track pick ranking is low, the security risk is high, and the number of malicious code occurrences increases. In addition, the more recent the occurrence date, the higher the risk. If the HTTP response code is not accessible to the website, the risk can be assumed to increase.

3.3. How to collect website risk disclosure information

3.3.1. Web Site DNS Information Collection

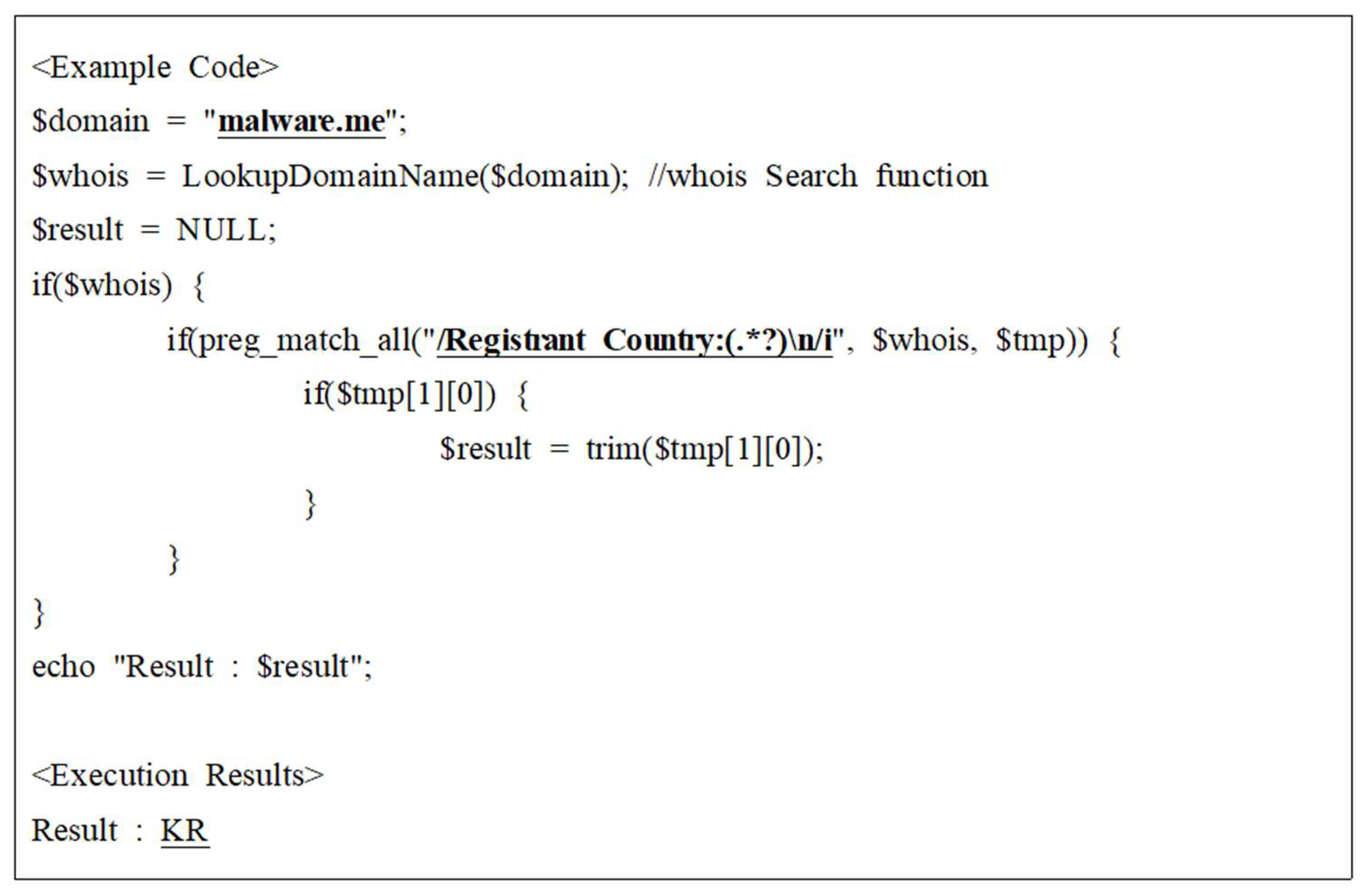

Information for determining the risk of a website can collect essential information through DNS. As shown in

Figure 6, the country, registrar, registration date, end date, registration agent, and name server information are collected through Whois queries. It is to be able to check in advance whether the website is dangerous through basic information. Collecting DNS public information on the website through Whois queries is possible through a string for each keyword when inquiring Whois. For example, to extract a do-main country, it can extract it using "Registrant Country".

3.3.2. Collecting website IP information

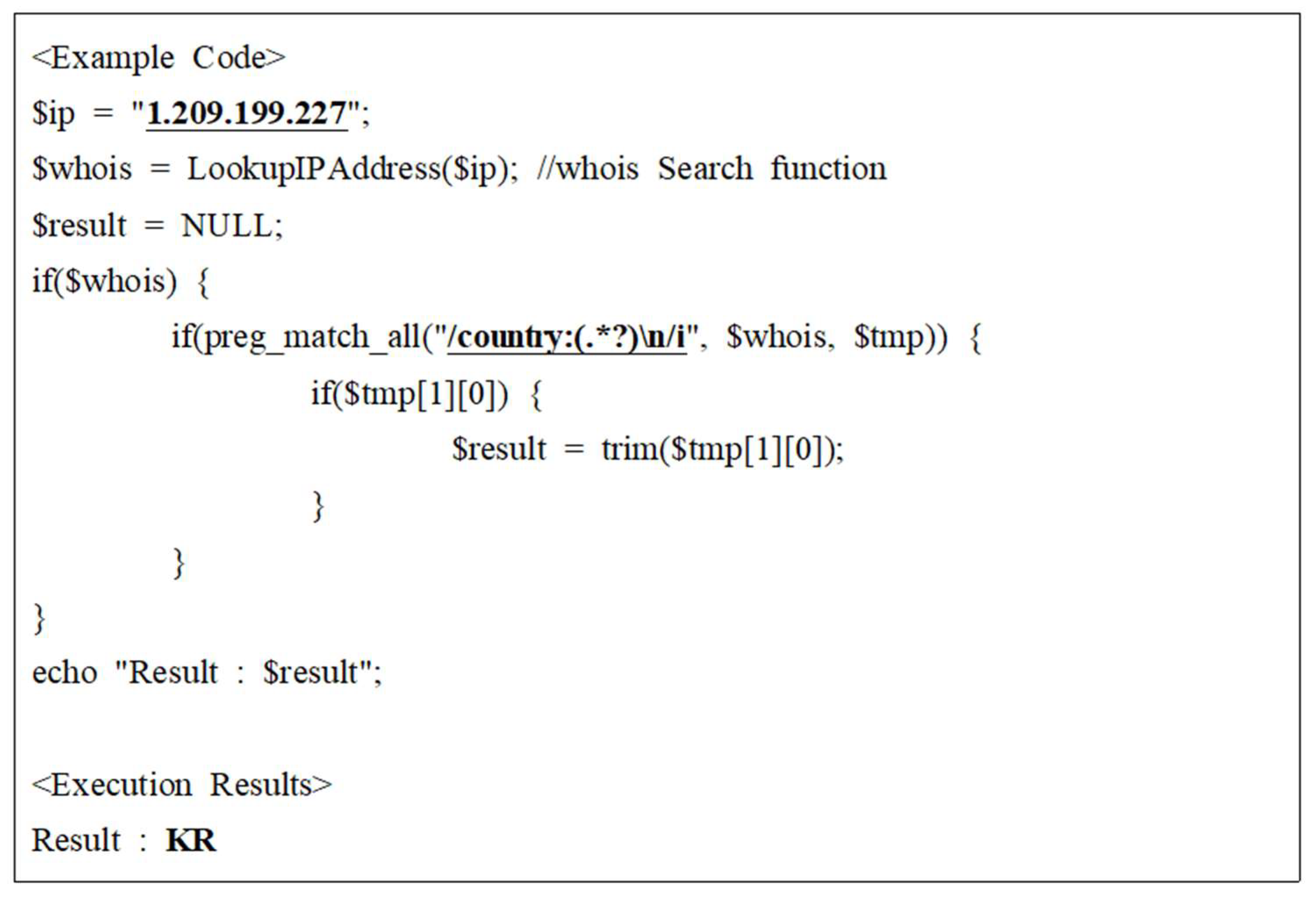

Information for determining the risk of a website may collect basic information through IP. As shown in [

Figure 7], country, allocation agency, and country comparison information through Whois queries were collected. Collecting public information about the website IP through whois queries is possible. Collecting public information on the website IP through Whois queries is possible through a string for each keyword when inquiring Whois. For example, IP country extraction can be extracted using "country".

3.3.3. Collection of website history information

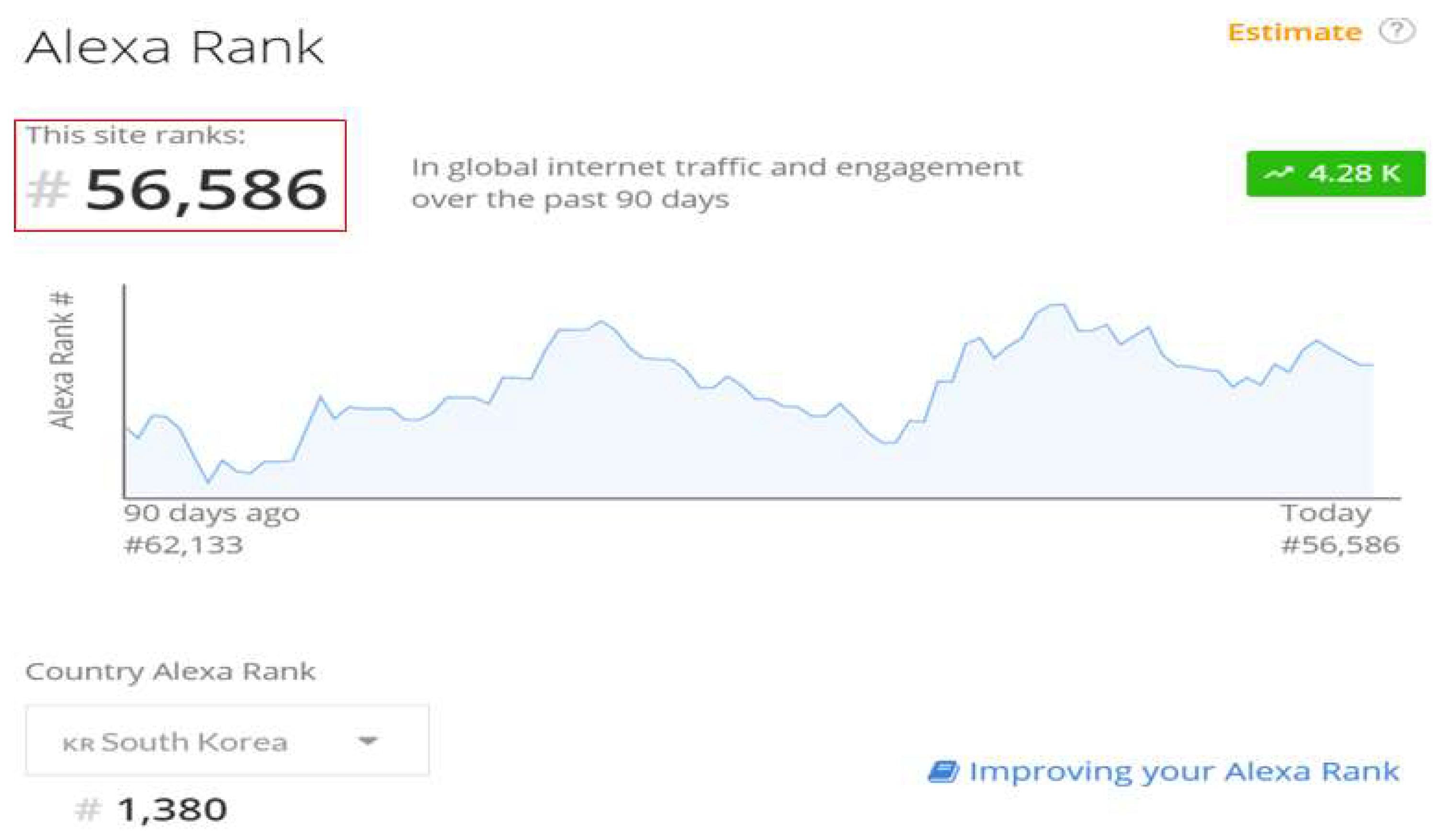

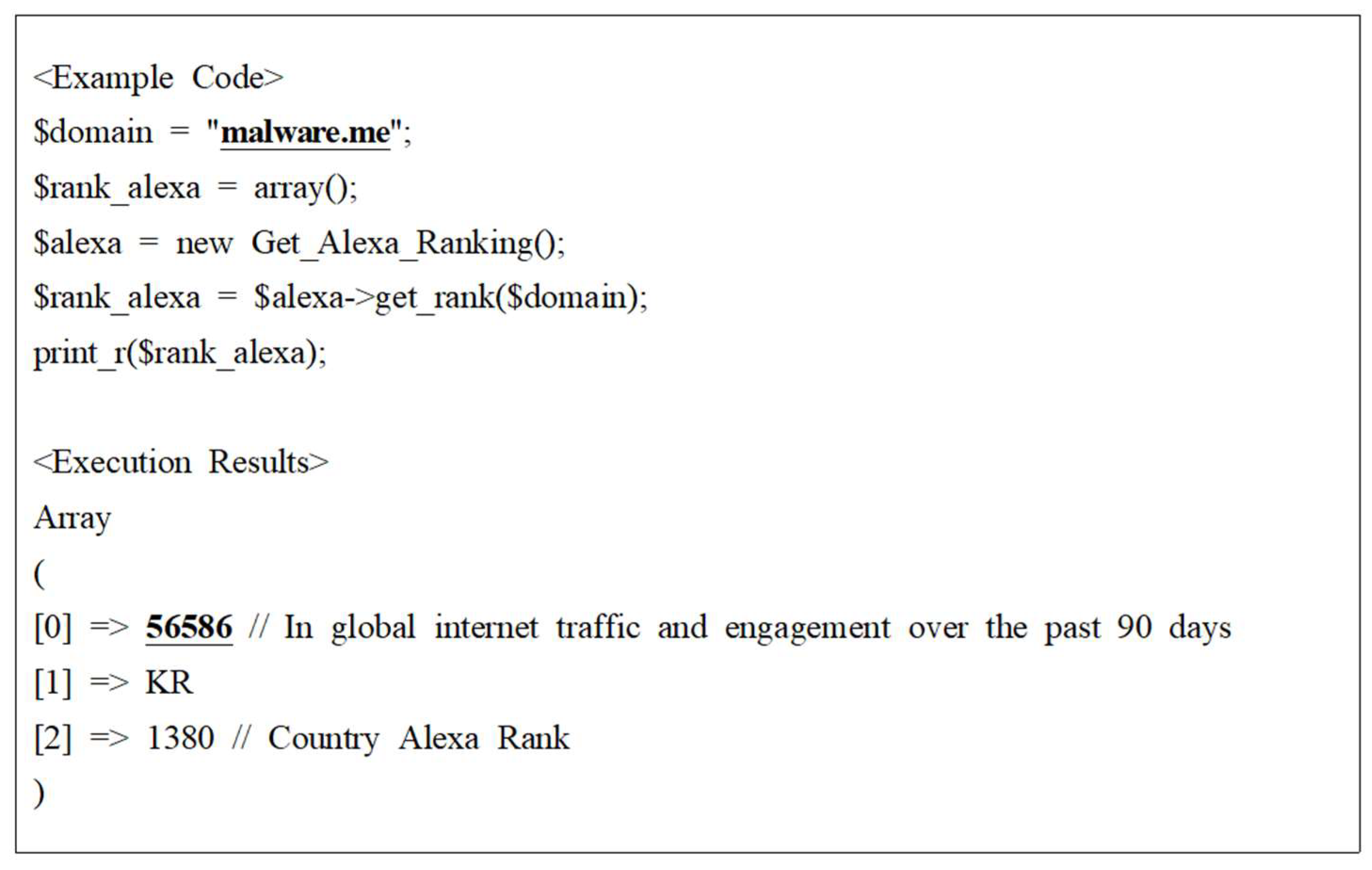

Websites with many Internet users invest a lot in security infrastructure to protect users at the corporate level. Therefore, the Ranking of website user traffic becomes basic information that can determine whether there is a security risk. As shown in

Figure 8, global website ranking information can be collected through Amazon's Alexa Traffic Rank service. As shown in [

Figure 8], the Amazon Alexa Rank public information does not identify real-time security threats, but it does show similarities to websites that have been the focus of security incidents. Additionally, you can collect global website ranking information.

As shown in

Figure 9, global traffic ranking information was collected through the Alexa Traffic Rank API.

Alexa Traffic Rank API Search

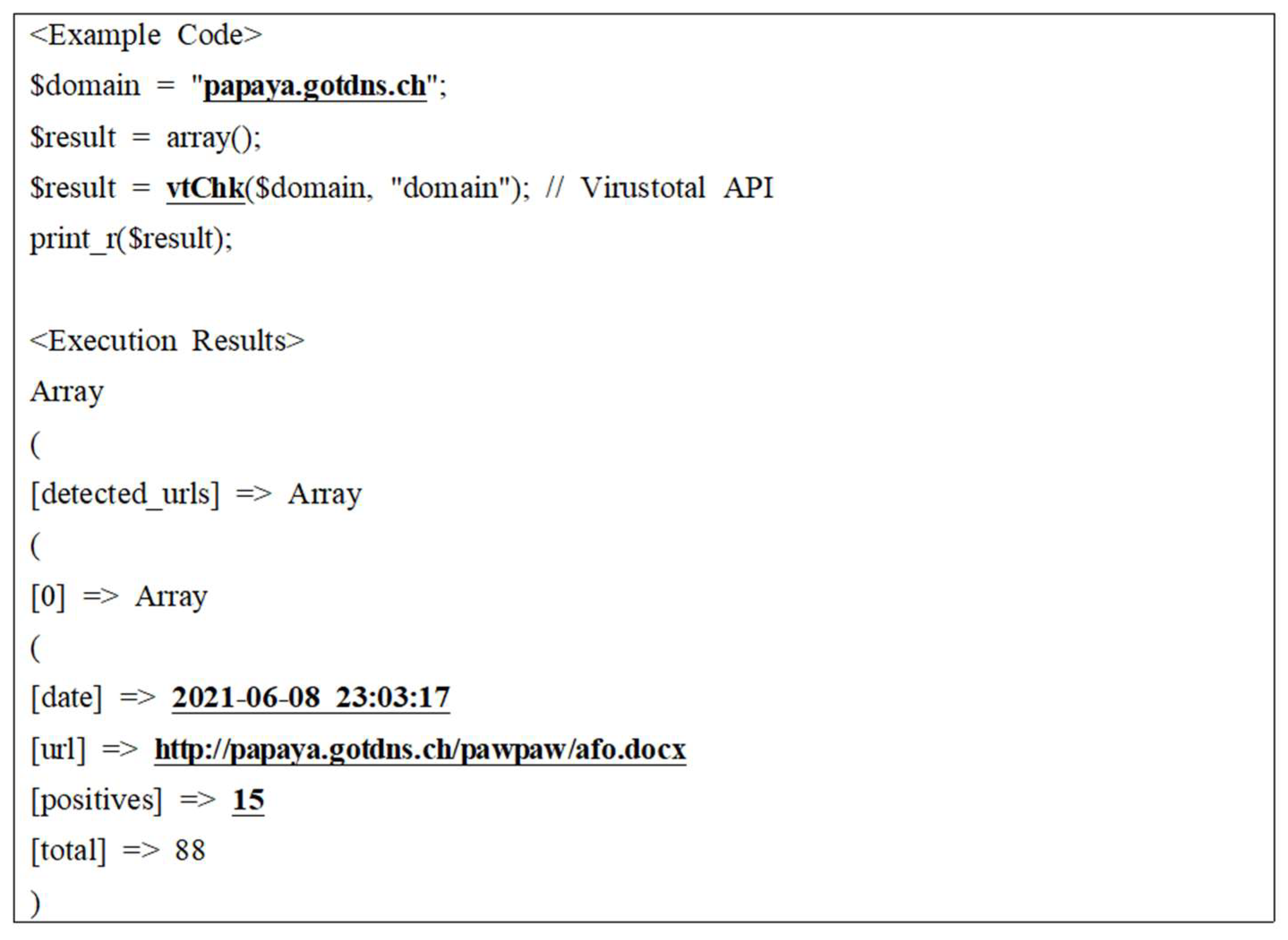

In order to measure the security risk of a website, it is essential to have a history of malicious code distribution on the website. In this study, malicious code distribution history information provided by Google Virustotal was used. As shown in [

Figure 10], information on the number and timing of malicious code distribution on the website can be collected by linking with the Google Virustotal API.

Virustotal API

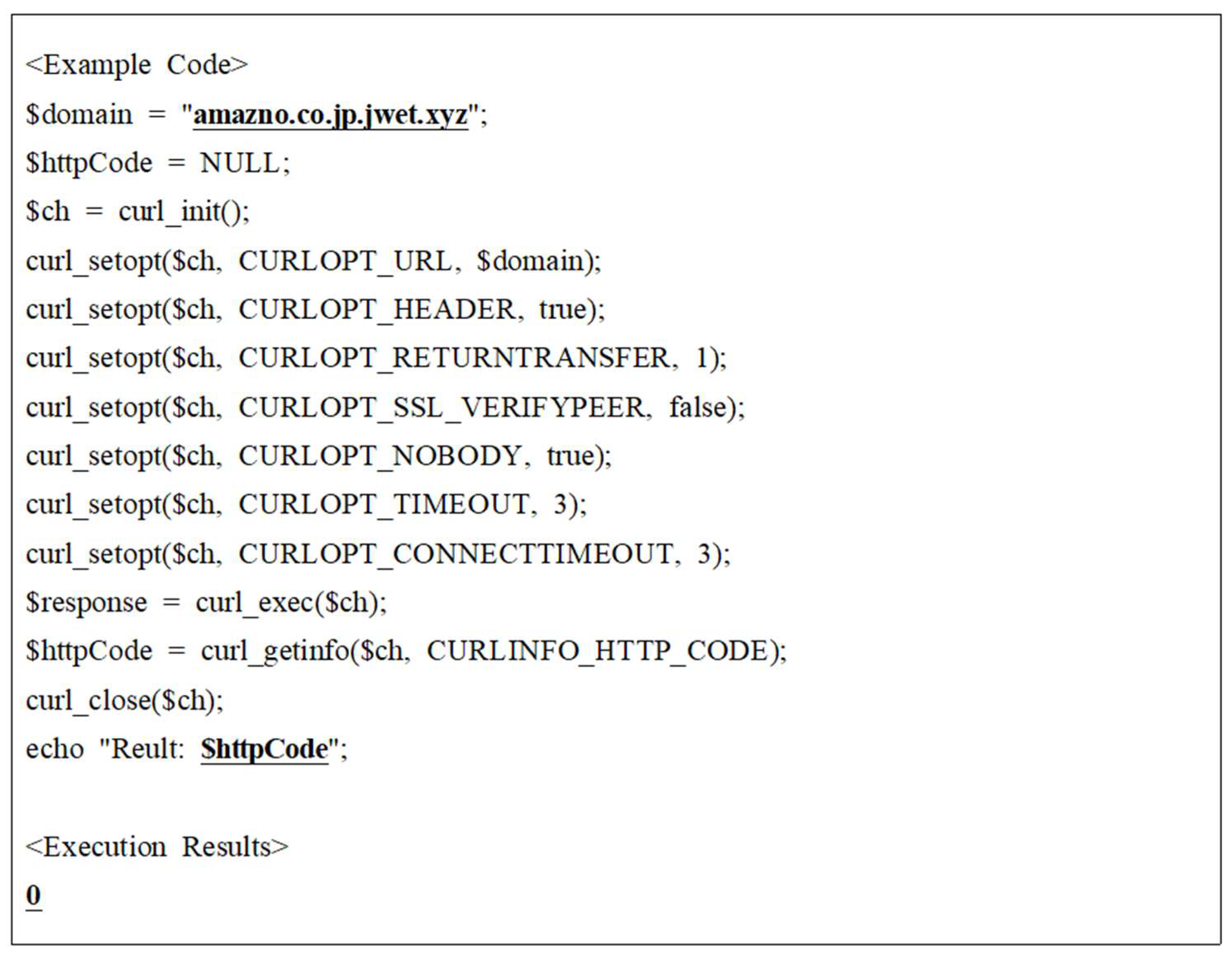

Attackers often open a website quickly to spread malicious code and then delete the website. Alternatively, collecting status information on the website is essential because it may be operated only when malicious code is distributed. As shown in [

Figure 11], HTTP status codes are a way to check the risk of a website's availability in real-time. For example, a status code of 200 is normal, while a 404 status code is unavailable and does not provide availability. If the HTTP status code is 0, the risk of the website increases as it does not operate the web server.

4. Experiment

This study conducted experiments on 1,000 regular domains and 1,000 domains classified as malicious code dissemination or phishing websites in 2021. As a result, information related to 2,000 website security risks was collected and analyzed. This paper presents the results of an experiment to measure the risk of a website using only OSINT information for public interest purposes..

4.1. Results of Website Domain Security Risk Measurement

To collect public information, we configured an experimental environment by connecting DNS and IP public websites and linked APIs for reputation research. The difference between the information collected for 1,000 regular domains and 1,000 malicious domains is as follows. As shown in <

Table 3>, among the unknown items in the collection of domain information, the domain registration date (regular 12%, malicious 66%), the domain termination date (regular 11%, malicious 66%), the domain registration agent (regular 10%, malicious 65%), and the domain name server (10%, malicious 65%). It was confirmed that the four collection items are information that needs to be collected for domain security risk. However, domain countries (64% regular, 75% malicious) and domain registrants (62% regular, 77% malicious) were found to have low discrimination among the unknown items.

4.2. The security risk measurement results of the website IP

The security risk measurement results of the website IP are as follows. As shown in

Table 4, among the unknown items in the collection of IP information, the results of IP countries (regular 12%, malicious 48%), IP allocation agencies (regular 12%, malicious 48%), and DNS and IP countries comparison (regular 4%, malicious 48%).

4.3. The security risk measurement results of Website reputation inquiry

As shown in

Table 5, the security risk measurement results of the Website reputation inquiry are as fol-lows. Among the unknown items in the collection of reputation information, the Global Traffic Rank (13% regular, 89% malicious), the number of malicious codes (96%, 1% malicious), the date of occurrence of malicious codes (96%, 1% malicious), and HTTP Response Code (11% regular, 59% malicious). In partic-ular, when the number of malicious codes and the date of occurrence are usual, it was confirmed that the higher the unknown number, the lower the risk.

4.4. Expected effect

As shown in <

Table 6>, public information collection is used to measure website security risk. Domain countries and domain registrants were not adopted as items that were difficult to distinguish between nor-mal and malicious. Domain registration date, domain termination date, domain registration agent, domain name server, IP country, IP allocation agency, DNS-IP country comparison, Global Traffic Rank, and HTTP Response code showed that the higher the Unknown ratio, the higher the risk. It was confirmed that the risk of malicious code occurrence and malicious code occurrence date decreased as the Unknow ratio decreased. As a result of this study, 11 items were found to increase the accuracy of risk measurement in public information on the website. We presented experimental results showing that it is possible to collect basic information about publicly available websites and check them for maliciousness.

5. Conclusion

Recently, malicious code distribution using vulnerabilities in websites accessed by many users has been increasing. Accordingly, the importance of measuring the security risk of websites is increasing. Static and dynamic analysis of website security risks is generally used to analyze website security risks.

The website security risk measurement's technology mainly aims at inspection speed, zero-day malicious code analysis possibility, and accuracy of analysis results.

The main method of measuring website security threats is reputation research based on the record of previous security incidents. It is classified into dynamic checks that check malware by accessing the user's terminal environment and static checks that check malware detection patterns.

This study proposed a method that can be collected through information disclosed on the Internet in measuring website risk. DNS, IP, and website history information are required to measure website risk. The website history information can be checked for global traffic rankings, malicious code distribution history, and HTTP access status.

This study proposed a three-step plan to collect the published website risk information. First, this study experimented with collecting and analyzing information related to 2,000 website security risks on 1,000 regular domains and 1,000 domains that were distributed malicious code or classified as phishing websites in 2021. In order to measure the security risk of the website through the experimental results, 11 items for collecting public information with high accuracy and meaningful results are proposed. This study collected basic information on OSINT, a publicly available website, and checked whether it is malicious. Fanally, This study confirmed the possibility of big data analysis of OSINT in the future.

References

- Kuyoung Shin, Jinchel Yoo, Changhee Han, et al., "A study on building a cyber attack database using Open Source Intelligence(OSINT)", Convergence Security Journal 19(2), pp. 113-133, 2019.

- Kim, KH. , Lee, DI., Shin, YT. (2018). Research on Cloud-Based on Web Application Malware Detection Methods. In: Park, J., Loia, V., Yi, G., Sung, Y. (eds) Advances in Computer Science and Ubiquitous Computing. CUTE CSA 2017 2017. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol 474. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Yong-Joon Lee, Se-Joon Park, and Won-Hyung Park,“Military Information Leak Response Technology through OSINT Information Analysis Using SNSes”, Security and Communication Networks, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Tan, P. Zhang, Q. Liu, X. Liu, C. Zhu, and F. Dou, "Adaptive Malicious URL Detection: Learning in the

Presence of Concept Drifts," 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in

Computing and Communications/ 12th IEEE International Conference on Big Data Science and

Engineering (TrustCom/BigDataSE), New York, NY, USA, 2018, pp. 737-743. [CrossRef]

- K. Nandhini, and R. Balasubramaniam, "Malicious Website Detection Using Probabilistic Data Structure Bloom Filter," 2019 3rd International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC), Erode, India, 2019, pp. 311-316. [CrossRef]

- T. Shibahara, Y. Takata, M. Akiyama, T. Yagi, and T. Yada, "Detecting Malicious Websites by Integrating Malicious, Benign, and Compromised Redirection Subgraph Similarities," 2017 IEEE 41st Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Turin, Italy, 2017, pp. 655-664. [CrossRef]

- Himanshu Mishra, Ram Kumar Karsh, and K. Pavani, “Anomaly-Based Detection of System-Level Threats

and Statistical Analysis,” Smart Computing Paradigms: New Progresses and Challenges, 2019, pp 271–279. [CrossRef]

- Nayeem Khan, Johari Abdullah, Adnan Shahid Khan, "Defending Malicious Script Attacks Using Machine Learning Classifiers", Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, vol. 2017, Article ID 5360472, 9 pages, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Husak and J. Kaspar, “towards Predicting Cyber Attacks Using Information Exchange and Data Mining,” in 2018 14th International Wireless Communications Mobile Computing Conference(IWCMC), 2018.

- Singhal, U. Chawla, and R. Shorey, "Machine Learning & Concept Drift based Approach for Malicious

Website Detection," 2020 International Conference on COMmunication Systems & NETworkS

(COMSNETS), Bengaluru, India, 2020, pp. 582-585. [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.M. Comesaña, C.I. García-Nieto, P.J. "Machine learning techniques applied to cyber

security",Int.J.Mach.Learn.Cybern.2019.

- D. Liu, and J. Lee, "CNN Based Malicious Website Detection by Invalidating Multiple Web Spams," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 97258-9 7266, 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).